Are you seeking one-on-one college counseling and/or essay support? Limited spots are now available. Click here to learn more.

How to Write the Diversity Essay – With Examples

May 1, 2024

The diversity essay has newfound significance in college application packages following the 2023 SCOTUS ruling against race-conscious admissions. Affirmative action began as an attempt to redress unequal access to economic and social mobility associated with higher education. But before the 2023 ruling, colleges frequently defended the policy based on their “compelling interest” in fostering diverse campuses. The reasoning goes that there are certain educational benefits that come from heterogeneous learning environments. Now, the diversity essay has become key for admissions officials in achieving their compelling interest in campus diversity. Thus, unlocking how to write a diversity essay enhances an applicant’s ability to describe their fit with a campus environment. This article describes the genre and provides diversity essay examples to help any applicant express how they conceptualize and contribute to diversity.

How to Write a Diversity Essay – Defining the Genre

Diversity essays in many ways resemble the personal statement genre. Like personal statements, they help readers get to know applicants beyond their academic and extracurricular achievements. What makes an applicant unique? Precisely what motivates or inspires them? What is their demeanor like and how do they interact with others? All these questions are useful ways of thinking about the purpose and value of the diversity essay.

It’s important to realize that the essay does not need to focus on aspects like race, religion, or sexuality. Some applicants may choose to write about their relationship to these or other protected identity categories. But applicants shouldn’t feel obligated to ‘come out’ in a diversity essay. Conversely, they should not be anxious if they feel their background doesn’t qualify them as ‘diverse.’

Instead, the diversity essay helps demonstrate broader thinking about what makes applicants unique that admissions officials can’t glean elsewhere. Usually, it also directly or indirectly indicates how an applicant will enhance the campus community they hope to join. Diversity essays can explicitly connect past experiences with future plans. Or they can offer a more general sense of how one’s background will influence their actions in college.

Thus, the diversity essay conveys both aspects that make an applicant unique and arguments for how those aspects will contribute on campus. The somewhat daunting genre is, in fact, a great opportunity for applicants to articulate how their background, identity, or formative experiences will shape their academic, intellectual, social, and professional trajectories.

Diversity College Essay Examples of Prompts – Sharing a Story

All diversity essays ask applicants to share what makes them unique and convey how that equips them for university life. However, colleges will typically ask applicants to approach this broad topic from a variety of different angles. Since it’s likely applicants will encounter some version of the genre in either required or supplemental essay assignments, it’s a good idea to have a template diversity essay ready to adapt to each specific prompt.

One of the most standard prompts is the “share a story” prompt. For example, here’s the diversity-related Common App prompt:

“Some students have a background, identity, interest, or talent that is so meaningful they believe their application would be incomplete without it. If this sounds like you, then please share your story.”

This prompt is deliberately broad, inviting applicants to articulate their distinctive qualities in myriad ways. What is unsaid, but likely expected, is some statement about how the story evidences the ability to enhance campus diversity.

Diversity College Essay Examples of Prompts – Describing Contribution

Another common prompt explicitly asks students to reflect on diversity while centering what they will contribute in college. A good example of this prompt comes from the University of Miami’s supplemental essay:

Located within one of the most dynamic cities in the world, the University of Miami is a distinctive community with a variety of cultures, traditions, histories, languages, and backgrounds. The University of Miami is a values-based and purpose-driven postsecondary institution that embraces diversity and inclusivity in all its forms and strives to create a culture of belonging, where every person feels valued and has an opportunity to contribute.

Please describe how your unique experiences, challenges overcome, or skills acquired would contribute to our distinctive University community. (250 words)

In essays responding to these kinds of prompts, its smart to more deliberately tailor your essay to what you know about the institution and its values around diversity. You’ll need a substantial part of the essay to address not only your “story” but your anticipated institutional contribution.

Diversity College Essay Examples of Prompts – Navigating Difference

The last type of diversity essay prompt worth mentioning asks applicants to explain how they experience and navigate difference. It could be a prompt about dealing with “diverse perspectives.” Or it could ask the applicant to tell a story involving someone different than them. Regardless of the framing, these types of prompts ask you to unfold a theory of diversity stemming from social encounters. Applicants might still think of how they can use the essay to frame what makes them unique. However, here colleges are also hoping for insight into how applicants will deal with the immense diversity of college life beyond their unique experiences. In these cases, it’s especially important to use a story kernel to draw attention to fundamental beliefs and values around diversity.

How to Write a Diversity Essay – Tips for Writing

Before we get to the diversity college essay examples, some general tips for writing the diversity essay:

- Be authentic: This is not the place to embellish, exaggerate, or overstate your experiences. Writing with humility and awareness of your own limitations can only help you with the diversity essay. So don’t write about who you think the admissions committee wants to see – write about yourself.

- Find dynamic intersections: One effective brainstorming strategy is to think of two or more aspects of your background, identity, and interests you might combine. For example, in one of the examples below, the writer talks about their speech impediment alongside their passion for poetry. By thinking of aspects of your experience to combine, you’ll likely generate more original material than focusing on just one.

- Include a thesis: Diversity essays follow more general conventions of personal statement writing. That means you should tell a story about yourself, but also make it double as an argumentative piece of writing. Including a thesis in the first paragraph can clearly signal the argumentative hook of the essay for your reader.

- Include your definition of diversity: Early in the essay you should define what diversity means to you. It’s important that this definition is as original as possible, preferably connecting to the story you are narrating. To avoid cliché, you might write out a bunch of definitions of diversity. Then, review them and get rid of any that seem like something you’d see in a dictionary or an inspirational poster. Get those clichéd definitions out of your system early, so you can wow your audience with your own carefully considered definition.

How to Write a Diversity Essay – Tips for Writing (Cont.)

- Zoom out to diversity more broadly: This tip is especially important you are not writing about protected minority identities like race, religion, and sexuality. Again, it’s fine to not focus on these aspects of diversity. But you’ll want to have some space in the essay where you connect your very specific understanding of diversity to a larger system of values that can include those identities.

Revision is another, evergreen tip for writing good diversity essays. You should also remember that you are writing in a personal and narrative-based genre. So, try to be as creative as possible! If you find enjoyment in writing it, chances are better your audience will find entertainment value in reading it.

How to Write a Diversity Essay – Diversity Essay Examples

The first example addresses the “share a story” prompt. It is written in the voice of Karim Amir, the main character of Hanif Kureishi’s novel The Buddha of Suburbia .

As a child of the suburbs, I have frequently navigated the labyrinthine alleys of identity. Born to an English mother and an Indian father, I inherited a rich blend of traditions, customs, and perspectives. From an early age, I found myself straddling two worlds, trying to reconcile the conflicting expectations of my dual heritage. Yet, it was only through the lens of acting that I began to understand the true fluidity of identity.

- A fairly typical table setting first paragraph, foregrounding themes of identity and performance

- Includes a “thesis” in the final sentence suggesting the essay’s narrative and argumentative arc

Diversity, to me, is more than just a buzzword describing a melting pot of ethnic backgrounds, genders, and sexual orientations. Instead, it evokes the unfathomable heterogeneity of human experience that I aim to help capture through performance. On the stage, I have often been slotted into Asian and other ethnic minority roles. I’ve had to deal with discriminatory directors who complain I am not Indian enough. Sometimes, it has even been tempting to play into established stereotypes attached to the parts I am playing. However, acting has ultimately helped me to see that the social types we imagine when we think of the word ‘diversity’ are ultimately fantastical constructions. Prescribed identities may help us to feel a sense of belonging, but they also distort what makes us radically unique.

- Includes an original definition of diversity, which the writer compellingly contrasts with clichéd definitions

- Good narrative dynamism, stressing how the writer has experienced growth over time

Diversity Essay Examples Continued – Example One

The main challenge for an actor is to dig beneath the “type” of character to find the real human being underneath. Rising to this challenge entails discarding with lazy stereotypes and scaling what can seem to be insurmountable differences. Bringing human drama to life, making it believable, requires us to realize a more fundamental meaning of diversity. It means locating each character at their own unique intersection of identity. My story, like all the stories I aspire to tell as an actor, can inspire others to search for and celebrate their specificity.

- Focuses in on the kernel of wisdom acquired over the course of the narrative

- Indirectly suggests what the applicant can contribute to the admitted class

Acting has ultimately underlined an important takeaway of my dual heritage: all identities are, in a sense, performed. This doesn’t mean that heritage is not important, or that identities are not significant rallying points for community. Instead, it means recognizing that identity isn’t a prison, but a stage.

- Draws the reader back to where the essay began, locating them at the intersection of two aspects of writer’s background

- Sharply and deftly weaves a course between saying identities are fictions and saying that identities matter (rather than potentially alienating reader by picking one over the other)

Diversity Essay Examples Continued – Example Two

The second example addresses a prompt about what the applicant can contribute to a diverse campus. It is written from the perspective of Jason Taylor, David Mitchell’s protagonist in Black Swan Green .

Growing up with a stutter, each word was a hesitant step, every sentence a delicate balance between perseverance and frustration. I came to think of the written word as a sanctuary away from the staccato rhythm of my speech. In crafting melodically flowing poems, I discovered a language unfettered by the constraints of my impediment. However, diving deeper into poetry eventually made me realize how my stammer had a humanistic rhythm all its own.

- Situates us at the intersection of two themes – a speech impediment and poetry – and uses the thesis to gesture to their synthesis

- Nicely matches form and content. The writer uses this opportunity to demonstrate their facility with literary language.

Immersing myself in the genius of Langston Hughes, Walt Whitman, and Maya Angelou, I learned to embrace the beauty of diversity in language, rhythm, and life itself. Angelou wrote that “Everything in the universe has a rhythm, everything dances.” For me, this quote illuminates how diversity is not simply a static expression of discrete differences. Instead, diversity teaches us the beauty of a multitude of rhythms we can learn from and incorporate in a mutual dance. If “everything in the universe has a rhythm,” then it’s also possible that anything can be poetry. Even my stuttering speech can dance.

- Provides a unique definition of diversity

- Conveys growth over time

- Connects kernel of wisdom back to the essay’s narrative starting point

As I embark on this new chapter of my life, I bring with me the lessons learned from the interplay of rhythm and verse. I bring a perspective rooted in empathy, an unwavering commitment to inclusivity, and a belief in language as the ultimate tool of transformative social connection. I am prepared to enter your university community, adding a unique voice that refuses to be silent.

- Directly addresses how background and experiences will contribute to campus life

- Conveys contributions in an analytic mode (second sentence) and more literary and personal mode (third sentence)

Additional Resources

Diversity essays can seem intimidating because of the political baggage we bring to the word ‘diversity.’ But applicants should feel liberated by the opportunity to describe what makes them unique. It doesn’t matter if applicants choose to write about aspects of identity, life experiences, or personal challenges. What matters is telling a compelling story of personal growth. Also significant is relating that story to an original theory of the function and value of diversity in society. At the end of the day, committees want to know their applicants deeper and get a holistic sense of how they will improve the educational lives of those around them.

Additional Reading and Resources

- 10 Instructive Common App Essay Examples

- How to Write the Overcoming Challenges Essay + Example

- Common App Essay Prompts

- Why This College Essay – Tips for Success

- How to Write a Body Paragraph for a College Essay

- UC Essay Examples

- College Essay

Tyler Talbott

Tyler holds a Bachelor of Arts in English from the University of Missouri and two Master of Arts degrees in English, one from the University of Maryland and another from Northwestern University. Currently, he is a PhD candidate in English at Northwestern University, where he also works as a graduate writing fellow.

- 2-Year Colleges

- Application Strategies

- Best Colleges by Major

- Best Colleges by State

- Big Picture

- Career & Personality Assessment

- College Search/Knowledge

- College Success

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Data Visualizations

- Dental School Admissions

- Extracurricular Activities

- Graduate School Admissions

- High School Success

- High Schools

- Law School Admissions

- Medical School Admissions

- Navigating the Admissions Process

- Online Learning

- Private High School Spotlight

- Summer Program Spotlight

- Summer Programs

- Test Prep Provider Spotlight

“Innovative and invaluable…use this book as your college lifeline.”

— Lynn O'Shaughnessy

Nationally Recognized College Expert

College Planning in Your Inbox

Join our information-packed monthly newsletter.

I am a... Student Student Parent Counselor Educator Other First Name Last Name Email Address Zip Code Area of Interest Business Computer Science Engineering Fine/Performing Arts Humanities Mathematics STEM Pre-Med Psychology Social Studies/Sciences Submit

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Training (DEI)

Ivan Andreev

Demand Generation & Capture Strategist, Valamis

March 10, 2022 · updated April 3, 2024

16 minute read

Diversity, equity and inclusion training is an increasingly important topic for organizations in every industry.

As the conversation around this topic grows, it is important for all organizations to look at their own diversity training programs and see where they can improve, become more effective, and, importantly, understand what does and doesn’t work.

After reading this guide, you will better understand the various types of diversity programs, how to build an effective program within your organization, and why you should be paying attention to this important subject.

- What is diversity and inclusion training?

The goals of diversity training

The importance of diversity and inclusion training in the workplace, real-world examples of why diversity training is important, what are the benefits of diversity training, examples of diversity training activities, how to make diversity training more effective.

- FAQ about diversity training

What is diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) training?

Diversity, equity, and inclusion training is an organized educational program that aims to promote awareness and understanding of how people with different backgrounds, cultures, ages, races, genders, sexuality, religions, physical conditions, and beliefs can best work together harmoniously.

Sometimes it is also referred to DEI , DE&I, or DEIB , which means diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging.

It aims to highlight areas where people might hold bias or outdated beliefs, provide information to help counter those biases, and overall train people to treat their fellow employees with respect and dignity.

An effective diversity and inclusion training program will teach employees how to recognize bias within themselves or others and show them how they can unlearn negative behaviors associated with it.

It will provide information that highlights the positive ways that changes in behavior can affect themselves, their colleagues, and their organization.

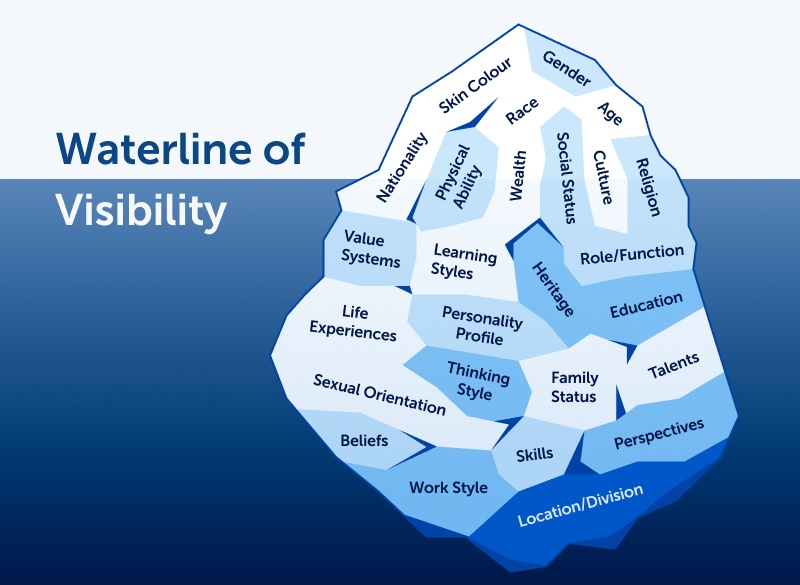

Source: Brook Graham – The Diversity Iceberg (2011)

Diversity and inclusion training aims to create a more harmonious workplace by increasing employee’s knowledge and awareness of cultural, religious, or racial differences while delivering information about how a person can change their behavior to be more inclusive.

In order to figure out how to reach that overarching goal, many companies will use surveys to ask their employees what their short and medium-term goals should be.

Each organization will have different areas that need work, and their employees will be the best source of information on which areas are the most pressing.

Here are some common goals that organizations have identified:

- Create a healthy working environment where people of different backgrounds, experiences, perspectives, and talents can productively work together.

- Increase the number of women, people of color, or otherwise underrepresented people within the organization.

- Increase the use of inclusive language within job postings, internal communications, and external communications.

- Increase the amount of time and money spent on diversity and inclusion training within the organization.

- Create an environment that nurtures and promotes diversity.

In spending time on internal surveys, an organization can better understand where they need to focus their energy. It might be that job postings are not inclusive, so there are no diverse applicants applying for the job.

That leads to fewer diverse people within the organization, all because the job posting was not written well.

McKinsey has researched this subject deeply and has released a series of reports highlighting the business advantages enjoyed by companies with more diverse employees.

Released in 2015 , 2017 , and 2020 , these reports show that diverse companies are 35% more likely to deliver above-average profit margins, as well as delivering more long-term value creation .

Significantly, these reports have found that “the most diverse companies are now more likely than ever to outperform non-diverse companies on profitability… we found that the higher the representation, the higher the likelihood of outperformance.”

However, these reports also show that there is slow growth in this area, with many companies struggling to achieve significant results, or even reporting that diversity within their ranks has decreased.

This demonstrates the difficulty of creating effective diversity programs, and the importance of continually working to improve diversity training within an organization.

These reports also show that ongoing diversity and inclusion training is a key factor to retaining diverse talent within an organization.

It stands to reason – it is difficult to keep employees in an environment in which they do not feel welcome.

In 2018, Starbucks found itself in the middle of a public relations crisis when an employee called the police on two black men who were waiting for a friend in a Philadelphia cafe without ordering anything.

The men were arrested, despite doing nothing wrong, and the incident went viral.

Many activists used the incident to highlight bias against Black people and protesters began to hold demonstrations inside stores.

In response, Starbucks decided to close all of its 8,000 U.S. stores for a day to hold racial bias training.

The program, “designed to address implicit bias, promote conscious inclusion, prevent discrimination and ensure everyone inside a Starbucks store feels safe and welcome,” according to the corporation, was met with a mixed response.

Experts in diversity and inclusion pointed out that research shows that this type of one-day training often fails to produce even short-term results .

Starbucks leadership acknowledged that the issue was not one that could be solved within one day, and promised to create a program that was central to the company’s core mission and in line with their values.

High-end cosmetics store Sephora found itself in a similar situation to Starbucks in 2019 when rapper and musician SZA reported being racially profiled at a Los Angeles store.

After major news outlets around the world picked up the story, linking it back to the incident in Starbucks the year before, Sephora announced that it would be closing all US stores for an hour for diversity training, although they clarified that this was planned before the incident with SZA happened.

As with the Starbucks response, experts pointed out that one hour of diversity training would, at best, do nothing – and at worst, can actively ignite bias within employees.

Sephora corporate leadership acknowledged that they must do more, stating that this step was “the start of a larger diversity initiative that includes the creation of employee resource groups and social impact and philanthropic programs and more inclusivity training for managers.”

The City of Seattle

The city government of Seattle created a controversy when an anonymous city employee revealed that they were racially segregating the diversity training of city employees.

White employees received training separately, and of different content, than employees who identify as people of color.

White employees were enrolled in a session that aimed to “examine our complicity in the system of white supremacy … and begin to cultivate practices that enable us to interrupt racism in ways that are accountable to Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC),” whereas people of color were invited to participate in a session that looked at how “American conditioning, socialization, and history leads People of Color to internalize radicalized beliefs, ideas, and behaviors about themselves, undergirding the power of White Supremacy.”

While some experts agreed that the two groups might benefit from content contextualized to their lived experience and backgrounds, diversity training is more effective when various groups can come together to better understand their differences – and similarities.

Develop and maintain a strategy-driven learning culture

Upgrade your organization’s learning culture with clear, actionable strategies to address the challenges.

Diversity and inclusion training has two sets of benefits.

On the one side, there are business-focused benefits:

- Drive bottom-line business success

- Deliver long-term value creation

- Avoid public relations disasters

- Bring in diverse talent with unique points of view

And on the other, people-centric benefits:

- Promote a healthy and inclusive organizational culture

- Improve employee retention

- Boost employee morale

- Happy employees produce better business results

These two sets of benefits dovetail together. When an effective diversity and inclusion program is deployed within an organization, it sets off a chain reaction of positive results for the organization and the people working within it.

Employees feel more respected, are happier within their interactions with colleagues and managers, and will work harder for the organization that elevates and respects them. They sell more products, or deliver better code, or are more efficient in their duties. They stay within your organization, perhaps being raised to senior-level posts, keeping down hiring costs and organizational knowledge remains within the company.

Clients receive great service or have their problems solved more quickly, and are happy with their results – perhaps even becoming evangelists for your company. As more people have positive interactions with your organization, better business results are soon being seen in your profit margins.

There are many ways for an organization to introduce diversity and inclusion training without it being a lecture or PowerPoint presentation.

1. What I want you to know about me…

This activity asks participants to write down on a sheet of paper an answer to the following prompts:

- What I think about me

- What others think about me

- What might be misunderstood about me

- What I need from you

It’s important that participants are encouraged to answer these questions only as much as they are comfortable .

It should not be obligatory for them to share deeply personal things if they are not willingly doing so.

Once the questions have been answered, the team should go around and address each person’s answer, and then a debriefing session should be completed.

The debrief should prompt participants to think about what they have learned about their peers, how it felt to complete the activity, and how they might be more inclusive in their actions going forward.

2. I am, but I am not…

For this activity, participants are given two sheets of paper. On one sheet, they will write an aspect of their identity.

An example of this could be Black, Asian, disabled, blind, gay or any other aspect of their identity that they wish to share.

On the other sheet, they will write what they are not, which will usually focus on a common stereotype about that identity.

For example, ‘I am Asian, but I am not good at math.’ Participants should fill out three to five of these sheets.

The purpose of this is to highlight the various stereotypes that the participants have had to face throughout their lives and to dispel them .

After everyone has shared their responses, the group should have a debriefing session where they can share what they learned, how they felt about hearing their peers’ responses, and how they felt sharing their own experiences.

3. Perspective taking

In this activity, participants are asked to put themselves in someone else’s shoes.

Participants are paired with peers of different backgrounds and are asked to write about the challenges that might have been faced by their partner based on their specific background.

The group should be given time for each person to talk about what they have written, and why, and for their peers to respond, giving more context to how their background has affected them.

For example, two engineers, a white, gay man, Michael, and a Black woman, Mary, are paired together. They would think about the other’s background and how it might have been different from theirs.

Michael writes, ‘Mary might have been discouraged from pursuing a technically difficult engineering degree because she is a woman.’ Mary writes, ‘Michael might have been left out of team building activities by colleagues because of his sexuality.’

Both people will walk away from the exercise understanding more about how life experience might differ based on a wide variety of factors.

A Harvard study has shown that this type of diversity training has potential for long term positive effects , as well as increasing inclusion towards other, unrelated groups.

4. Goal setting

The study mentioned above also found that goal setting can produce long-lasting positive results within diversity training.

In this activity, participants are asked to set measurable, attainable goals within their workplace.

These goals should be based around increasing inclusion, for example, challenging sexist jokes, increasing the inclusivity of language, or giving underrepresented people a platform.

When a clear path is laid out, with actionable steps that participants can focus on, diversity and inclusion training is much more effective.

1. Hire experts to lead your training

Just as you would hire accounting experts to streamline your organization’s books, you should look to experts in diversity and inclusion to work with your organization to develop a program that will truly be effective to your specific needs.

There will be different challenges based on geographic location, the demographics of your organization, the industry, and many other factors. There will not be a one-size-fits-all solution here.

2. Offer flexible training

As more organizations face the reality that one-time sessions will not deliver lasting results, diversity and inclusion experts are in higher demand than ever.

One Seattle-based firm has risen to meet this demand with online resources, including webinars, courses, and one-on-one coaching.

This can be a great solution for companies who are operating remotely, or simply find it difficult to gather all employees in one time and one place.

3. Create long-term solutions

To create a more diverse and inclusive organization, as well as avoid having negative publicity like in the examples above, an organization should focus on a long-term plan that is led by experts, rather than producing a short-term solution as a reaction to a specific event.

Research has shown that diversity training is most effective when it is promoted on a regular basis.

4. Lead by example

When the company leadership visibly upholds the values of diversity and inclusion, employees are much more likely to follow their example.

Your organization wants to promote these values, and leading by example is a powerful way to get that message across.

5. Don’t rely on only one type of training

Everyone learns differently.

Provide a wide range of education, which could include speeches, role-playing, one-on-one coaching, videos, or activities, and deliver all of those throughout the year.

Learners will get something different out of each type of content, and you are more likely to get the message across.

Training evaluation form

Get a handy printable form for evaluating training and course experiences.

Check out our guide about employee development methods to find more ideas on how you can differentiate and improve your diversity training.

6. Be clear in what you want to achieve

Set SMART goals, and develop a clear path to how you will get to them.

It is useless to say that you want to ‘promote diversity’ if you don’t know exactly what that means in the context of your specific organization. Setting goals leads to achieving goals.

7. Be patient

As we have noted above, diversity training is not something that can be completed in a day.

These biases are learned over a lifetime – they won’t go away in a day.

Have patience with your employees, and the leaders of the program, and understand that it might be a while before you see concrete results. This is a marathon, not a sprint!

FAQ about diversity and inclusion training

What does diversity training include.

Diversity training can be anything from a one-hour session that highlights the various forms of bias that a person might encounter, to a much more in-depth multi-month program.

It usually includes an explanation of the various types of marginalization that a person might face, including based on race, sexuality, physical appearance, disability, religion, class, and nationality.

It then provides guidance on how a person can avoid acting with bias, giving examples of positive and negative interactions and guidelines on how to approach others with respect.

What should diversity training focus on?

Diversity training should focus on long-term strategies to build an understanding of the differences between people and how to navigate those differences in the most respectful and productive manner possible.

This includes highlighting bias, presenting strategies for reducing bias within your employees, setting SMART goals for increasing diversity and inclusion within your organization and frequently checking in on how your organization is performing.

What are the elements of diversity?

These identities include, but are not limited to, ability, age, class, ethnicity, gender identity and expression, immigration status, intellectual differences, language, national origin, race, religion, socio-economic status, sex, and sexual orientation.

Some of these elements are internal, which means an unchangeable aspect that a person is born into, such as assigned sex or race. Others are external, something that is changeable but is often born into and can often be very difficult to change, such as religious beliefs or education.

Is mandatory diversity training legal?

Mandatory diversity training is legal. However, some companies will allow employees to opt out, provided that they have a reasonable excuse for not wanting to attend.

The idea behind this is that forcing someone to attend a training that they do not want to do might backfire, and leave them with more bias than before.

The ideal solution is to present the training as a positive, highlighting the ways in which it might improve employees’ experience at work and creating a positive buy-in from participants.

How effective is diversity training?

A 2019 study into the effectiveness of diversity training delivered mixed results in regards to the effectiveness of diversity training. On the one hand, they did see that attitudes towards women, and awareness of the bias that they face, was improved after the training. On the other hand, they did not see any real change in the behavior of men or white employees overall, even though these two groups often hold power within organizations and are generally the targets of diversity training programs.

That said, there is research that shows that diversity training can be effective, and the reason that existing programs are not effective is simply that they are not using the right techniques. By using the same diversity training techniques since the 1960s, which have never shown promising results, organizations are wasting time and money. If an organization wants an effective diversity training program, it should be looking at new ideas, techniques, and activities to get the results that they want.

You might be interested in

What is an Learning Management System (LMS)

Find out what a Learning Management System is. What does it do? What are the benefits of having LMS, and how to select the best LMS for your organization?

Career development plan

Learn what a career development plan is and how to create it. Discover examples and download the career development planning template in PDF.

Discover the essence of mentoring and how it differs from coaching. Explore the types of mentoring, its definition, and the numerous benefits it can bring to individuals and the workplace.

Which program are you applying to?

Accepted Admissions Blog

Everything you need to know to get Accepted

May 8, 2024

The Diversity Essay: How to Write an Excellent Diversity Essay

What is a diversity essay in a school application? And why does it matter when applying to leading programs and universities? Most importantly, how should you go about writing such an essay?

Diversity is of supreme value in higher education, and schools want to know how every student will contribute to the diversity on their campus. A diversity essay gives applicants with disadvantaged or underrepresented backgrounds, an unusual education, a distinctive experience, or a unique family history an opportunity to write about how these elements of their background have prepared them to play a useful role in increasing and encouraging diversity among their target program’s student body and broader community.

The purpose of all application essays is to help the adcom better understand who an applicant is and what they care about. Your essays are your chance to share your voice and humanize your application. This is especially true for the diversity essay, which aims to reveal your unique perspectives and experiences, as well as the ways in which you might contribute to a college community.

In this post, we’ll discuss what exactly a diversity essay is, look at examples of actual prompts and a sample essay, and offer tips for writing a standout essay.

In this post, you’ll find the following:

What a diversity essay covers

How to show you can add to a school’s diversity, why diversity matters to schools.

- Seven examples that reveal diversity

Sample diversity essay prompts

How to write about your diversity.

- A diversity essay example

Upon hearing the word “diversity” in relation to an application essay, many people assume that they will have to write about gender, sexuality, class, or race. To many, this can feel overly personal or irrelevant, and some students might worry that their identity isn’t unique or interesting enough. In reality, the diversity essay is much broader than many people realize.

Identity means different things to different people. The important thing is that you demonstrate your uniqueness and what matters to you. In addition to writing about one of the traditional identity features we just mentioned (gender, sexuality, class, race), you could consider writing about a more unusual feature of yourself or your life – or even the intersection of two or more identities.

Consider these questions as you think about what to include in your diversity essay:

- Do you have a unique or unusual talent or skill?

- Do you have beliefs or values that are markedly different from those of the people around you?

- Do you have a hobby or interest that sets you apart from your peers?

- Have you done or experienced something that few people have? Note that if you choose to write about a single event as a diverse identity feature, that event needs to have had a pretty substantial impact on you and your life. For example, perhaps you’re part of the 0.2% of the world’s population that has run a marathon, or you’ve had the chance to watch wolves hunt in the wild.

- Do you have a role in life that gives you a special outlook on the world? For example, maybe one of your siblings has a rare disability, or you grew up in a town with fewer than 500 inhabitants.

If you are an immigrant to the United States, the child of immigrants, or someone whose ethnicity is underrepresented in the States, your response to “How will you add to the diversity of our class/community?” and similar questions might help your application efforts. Why? Because you have the opportunity to show the adcom how your background will contribute a distinctive perspective to the program you are applying to.

Of course, if you’re not underrepresented in your field or part of a disadvantaged group, that doesn’t mean that you don’t have anything to write about in a diversity essay.

For example, you might have an unusual or special experience to share, such as serving in the military, being a member of a dance troupe, or caring for a disabled relative. These and other distinctive experiences can convey how you will contribute to the diversity of the school’s campus.

Maybe you are the first member of your family to apply to college or the first person in your household to learn English. Perhaps you have worked your way through college or helped raise your siblings. You might also have been an ally to those who are underrepresented, disadvantaged, or marginalized in your community, at your school, or in a work setting.

As you can see, diversity is not limited to one’s religion, ethnicity, culture, language, or sexual orientation. It refers to whatever element of your identity distinguishes you from others and shows that you, too, value diversity.

The diversity essay provides colleges the chance to build a student body that includes different ethnicities, religions, sexual orientations, backgrounds, interests, and so on. Applicants are asked to illuminate what sets them apart so that the adcoms can see what kind of diverse views and opinions they can bring to the campus.

Admissions officers believe that diversity in the classroom improves the educational experience of all the students involved. They also believe that having a diverse workforce better serves society as a whole.

The more diverse perspectives found in the classroom, throughout the dorms, in the dining halls, and mixed into study groups, the richer people’s discussions will be.

Plus, learning and growing in this kind of multicultural environment will prepare students for working in our increasingly multicultural and global world.

In medicine, for example, a heterogeneous workforce benefits people from previously underrepresented cultures. Businesses realize that they will market more effectively if they can speak to different audiences, which is possible when members of their workforce come from various backgrounds and cultures. Schools simply want to prepare graduates for the 21st century job market.

Seven examples that reveal diversity

Adcoms want to know about the diverse elements of your character and how these have helped you develop particular personality traits , as well as about any unusual experiences that have shaped you.

Here are seven examples an applicant could write about:

1. They grew up in an environment with a strong emphasis on respecting their elders, attending family events, and/or learning their parents’ native language and culture.

2. They are close to their grandparents and extended family members who have taught them how teamwork can help everyone thrive.

3. They have had to face difficulties that stem from their parents’ values being in conflict with theirs or those of their peers.

4. Teachers have not always understood the elements of their culture or lifestyle and how those elements influence their performance.

5. They have suffered discrimination and succeeded despite it because of their grit, values, and character.

6. They learned skills from a lifestyle that is outside the norm (e.g., living in foreign countries as the child of a diplomat or contractor; performing professionally in theater, dance, music, or sports; having a deaf sibling).

7. They’ve encountered racism or other prejudice (either toward themselves or others) and responded by actively promoting diverse, tolerant values.

And remember, diversity is not about who your parents are. It’s about who you are – at the core.

Your background, influences, religious observances, native language, ideas, work environment, community experiences – all these factors come together to create a unique individual, one who will contribute to a varied class of distinct individuals taking their place in a diverse world.

The best-known diversity essay prompt is from the Common App . It states:

“Some students have a background, identity, interest, or talent that is so meaningful they believe their application would be incomplete without it. If this sounds like you, then please share your story.”

Some schools have individual diversity essay prompts. For example, this one is from Duke University :

“We believe a wide range of personal perspectives, beliefs, and lived experiences are essential to making Duke a vibrant and meaningful living and learning community. Feel free to share with us anything in this context that might help us better understand you and what you might bring to our community.”

And the Rice University application includes the following prompt:

“Rice is strengthened by its diverse community of learning and discovery that produces leaders and change agents across the spectrum of human endeavor. What perspectives shaped by your background, experiences, upbringing, and/or racial identity inspire you to join our community of change agents at Rice?”

In all instances, colleges want you to demonstrate how and what you’ll contribute to their communities.

Your answer to a school’s diversity essay question should focus on how your experiences have built your empathy for others, your embrace of differences, your resilience, your character, and your perspective.

The school might ask how you think of diversity or how you will bring or add to the diversity of the school, your chosen profession, or your community. Make sure you answer the specific question posed by highlighting distinctive elements of your profile that will add to the class mosaic every adcom is trying to create. You don’t want to blend in; you want to stand out in a positive way while also complementing the school’s canvas.

Here’s a simple, three-part framework that will help you think of diversity more broadly:

Who are you? What has contributed to your identity? How do you distinguish yourself? Your identity can include any of the following: gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, disability, religion, nontraditional work experience, nontraditional educational background, multicultural background, and family’s educational level.

What have you done? What have you accomplished? This could include any of the following: achievements inside and/or outside your field of study, leadership opportunities, community service, internship or professional experience, research opportunities, hobbies, and travel. Any or all of these could be unique. Also, what life-derailing, throw-you-for-a-loop challenges have you faced and overcome?

How do you think? How do you approach things? What drives you? What influences you? Are you the person who can break up a tense meeting with some well-timed humor? Are you the one who intuitively sees how to bring people together?

Read more about this three-part framework in Episode 193 of Accepted’s Admissions Straight Talk podcast or listen wherever you get your favorite podcast s.

Think about each question within this framework and how you could apply your diversity elements to your target school’s classroom or community. Any of these elements can serve as the framework for your essay.

Don’t worry if you can’t think of something totally “out there.” You don’t need to be a tightrope walker living in the Andes or a Buddhist monk from Japan to be able to contribute to a school’s diversity!

And please remember, the examples we have offered here are not exhaustive. There are many other ways to show diversity!

All you need to do to be able to write successfully about how you will contribute to the diversity of your target school’s community is examine your identity, deeds, and ideas, with an eye toward your personal distinctiveness and individuality. There is only one you .

Take a look at the sample diversity essay in the next section of this post, and pay attention to how the writer underscores their appreciation for, and experience with, diversity.

A diversity essay sample

When I was starting 11th grade, my dad, an agricultural scientist, was assigned to a 3-month research project in a farm village in Niigata (northwest Honshu in Japan). Rather than stay behind with my mom and siblings, I begged to go with him. As a straight-A student, I convinced my parents and the principal that I could handle my schoolwork remotely (pre-COVID) for that stretch. It was time to leap beyond my comfortable suburban Wisconsin life—and my Western orientation, reinforced by travel to Europe the year before.

We roomed in a sprawling farmhouse with a family participating in my dad’s study. I thought I’d experience an “English-free zone,” but the high school students all studied and wanted to practice English, so I did meet peers even though I didn’t attend their school. Of the many eye-opening, influential, cultural experiences, the one that resonates most powerfully to me is experiencing their community. It was a living, organic whole. Elementary school kids spent time helping with the rice harvest. People who foraged for seasonal wild edibles gave them to acquaintances throughout the town. In fact, there was a constant sharing of food among residents—garden veggies carried in straw baskets, fish or meat in coolers. The pharmacist would drive prescriptions to people who couldn’t easily get out—new mothers, the elderly—not as a business service but as a good neighbor. If rain suddenly threatened, neighbors would bring in each other’s drying laundry. When an empty-nest 50-year-old woman had to be hospitalized suddenly for a near-fatal snakebite, neighbors maintained her veggie patch until she returned. The community embodied constant awareness of others’ needs and circumstances. The community flowed!

Yet, people there lamented that this lifestyle was vanishing; more young people left than stayed or came. And it wasn’t idyllic: I heard about ubiquitous gossip, long-standing personal enmities, busybody-ness. But these very human foibles didn’t dam the flow. This dynamic community organism couldn’t have been more different from my suburban life back home, with its insular nuclear families. We nod hello to neighbors in passing.

This wonderful experience contained a personal challenge. Blond and blue-eyed, I became “the other” for the first time. Except for my dad, I saw no Westerner there. Curious eyes followed me. Stepping into a market or walking down the street, I drew gazes. People swiftly looked away if they accidentally caught my eye. It was not at all hostile, I knew, but I felt like an object. I began making extra sure to appear “presentable” before going outside. The sense of being watched sometimes generated mild stress or resentment. Returning to my lovely tatami room, I would decompress, grateful to be alone. I realized this challenge was a minute fraction of what others experience in my own country. The toll that feeling—and being— “other” takes on non-white and visibly different people in the US can be extremely painful. Experiencing it firsthand, albeit briefly, benignly, and in relative comfort, I got it.

Unlike the organic Niigata community, work teams, and the workplace itself, have externally driven purposes. Within this different environment, I will strive to exemplify the ongoing mutual awareness that fueled the community life in Niigata. Does it benefit the bottom line, improve the results? I don’t know. But it helps me be the mature, engaged person I want to be, and to appreciate the individuals who are my colleagues and who comprise my professional community. I am now far more conscious of people feeling their “otherness”—even when it’s not in response to negative treatment, it can arise simply from awareness of being in some way different.

What did you think of this essay? Does this middle class Midwesterner have the unique experience of being different from the surrounding majority, something she had not experienced in the United States? Did she encounter diversity from the perspective of “the other”?

Here a few things to note about why this diversity essay works so well:

1. The writer comes from “a comfortable, suburban, Wisconsin life,” suggesting that her background might not be ethnically, racially, or in any other way diverse.

2. The diversity “points” scored all come from her fascinating experience of having lived in a Japanese farm village, where she immersed herself in a totally different culture.

3. The lessons learned about the meaning of community are what broaden and deepen the writer’s perspective about life, about a purpose-driven life, and about the concept of “otherness.”

By writing about a time when you experienced diversity in one of its many forms, you can write a memorable and meaningful diversity essay.

Working on your diversity essay?

Want to ensure that your application demonstrates the diversity that your dream school is seeking? Work with one of our admissions experts . This checklist includes more than 30 different ways to think about diversity to jump-start your creative engine.

Dr. Sundas Ali has more than 15 years of experience teaching and advising students, providing career and admissions advice, reviewing applications, and conducting interviews for the University of Oxford’s undergraduate and graduate programs. In addition, Sundas has worked with students from a wide range of countries, including the United Kingdom, the United States, India, Pakistan, China, Japan, and the Middle East. Want Sundas to help you get Accepted? Click here to get in touch!

Related Resources:

- Different Dimensions of Diversity , podcast Episode 193

- What Should You Do If You Belong to an Overrepresented MBA Applicant Group?

- Fitting In & Standing Out: The Paradox at the Heart of Admissions , a free guide

About Us Press Room Contact Us Podcast Accepted Blog Privacy Policy Website Terms of Use Disclaimer Client Terms of Service

Accepted 1171 S. Robertson Blvd. #140 Los Angeles CA 90035 +1 (310) 815-9553 © 2022 Accepted

Summer II 2024 Application Deadline is June 26, 2024.

Click here to apply.

Featured Posts

Pace University's Pre-College Program: Our Honest Review

Building a College Portfolio? Here are 8 Things You Should Know

Should You Apply to Catapult Incubator as a High Schooler?

8 Criminal Justice Internships for High School Students

10 Reasons to Apply to Scripps' Research Internship for High School Students

10 Free Business Programs for High School Students

Spike Lab - Is It a Worthwhile Incubator Program for High School Students?

10 Business Programs for High School Students in NYC

11 Summer Film Programs for High School Students

10 Photography Internships for High School Students

- 14 min read

7 Great Diversity Essay Examples and Why They Worked

Supplemental "diversity" or "community" essays are becoming increasingly popular components of college and university applications. A diversity essay allows you to highlight how your individual circumstances, values, traditions, or beliefs could contribute to the vibrant mix of cultures on a college campus.

The importance of the diversity essay lies in its ability to showcase aspects of your identity that may not be fully captured elsewhere in your application . It provides a platform for you to express your authenticity, highlight any obstacles or challenges you've overcome, and demonstrate how your unique viewpoints could enrich the learning environment.

This trend is in part driven by institutions' heightened efforts to increase the diversity of their student bodies, as many elite schools have historically favored wealthy and/or white applicants. These diversity essays provide a valuable opportunity for students to give context about their identity and background, which supports colleges' missions of fostering more inclusive campus environments.

The push for diversity essays has been compounded by the recent Supreme Court decision ruling affirmative action policies unconstitutional. With this ruling blocking colleges from directly considering an applicant's race or ethnicity in admissions decisions, many institutions have turned to supplemental essays as an alternative way to gauge how a prospective student's unique experiences and perspectives could contribute to a richly diverse student body. While not explicitly factoring racial or ethnic backgrounds into admissions, compelling diversity essays enable colleges to indirectly account for the varied identities and circumstances that applicants would bring to enrich the campus community.

However, even students who do not hold identities historically underrepresented at colleges, or face discrimination, are encouraged to approach the diversity essay thoughtfully. These essays allow all applicants to shed light on their individualized experiences that could add meaningful value to the institution's diversity and culture. Ultimately, colleges aim to curate an incoming class of students whose collective array of backgrounds fosters an environment of mutual understanding, intellectual growth, and cross-cultural exchange.

In this blog, we’ll walk through 7 examples of strong diversity essays, and give a brief discussion of the strengths and weaknesses of each one.

Note that for the sake of concision, only the first 150-250 words of each essay is included in the article. You can find links to the full text of each essay at the bottom of the page!

1. Finding My Voice (Hopkins)

I looked up and flinched slightly. There were at least sixty of them, far more than expected. I had thirty weeks to teach them the basics of public speaking. Gritting my teeth, I split my small group of tutors among the crowd and sat down for an impromptu workshop with the eighth graders. They were inexperienced, monotone, and quiet. In other words, they reminded me of myself…

I was born with a speech impediment that weakened my mouth muscles. My speech was garbled and incomprehensible. Understandably, I grew up quiet. I tried my best to blend in and give the impression I was silent by choice. I joined no clubs in primary school, instead preferring isolation. It took six years of tongue twisters and complicated mouth contortions in special education classes for me to produce the forty-four sounds of the English language.

This essay is highly effective in several ways. The author opens with a vivid, engaging anecdote that immediately draws the reader in and provides context for the essay's overarching theme of finding one's voice. The personal story of struggling with a speech impediment as a child and overcoming insecurities to become a confident public speaker on the debate team is powerful and memorable. The essay’s beginning, where Jerry is faced with the daunting task of teaching public speaking to a large group of eighth graders, is reminiscent of his own struggles with communication. This scene immediately captures the reader's attention and establishes a connection between Jerry's personal journey and the theme of the essay.

Throughout the essay, Jerry skillfully weaves together his experiences of overcoming a speech impediment and finding his confidence through participation in the debate team. He candidly reflects on the challenges he faced, such as stuttering and feeling like a "deer in the headlights," and how he persevered through practice and determination. By sharing specific anecdotes, such as watching upperclassmen and adapting his speaking style, Jerry demonstrates his growth and development over time.

The continued arc of the essay conveys the broader significance of Jerry's journey by highlighting how his newfound confidence extended beyond the debate team to his interactions in school and leadership roles. Through his own experiences, Jerry founded a program to help other students overcome their insecurities and find their voices, thereby paying forward the empowerment he received. The conclusion nicely ties back to the introduction and leaves the reader with a positive, uplifting sense of the author's journey and values.

One potential area for improvement could be spending slightly more time underscoring specific insights, challenges, or ways this experience shaped the author's goals and worldview could make the essay even more impactful for admissions officers evaluating the author's ability to contribute to a diverse community.

2. Protecting the Earth

I never understood the power of community until I left home to join seven strangers in the Ecuadorian rainforest. Although we flew in from distant corners of the U.S., we shared a common purpose: immersing ourselves in our passion for protecting the natural world.

Back home in my predominantly conservative suburb, my neighbors had brushed off environmental concerns. My classmates debated the feasibility of Trump’s wall, not the deteriorating state of our planet. Contrastingly, these seven strangers delighted in bird-watching, brightened at the mention of medicinal tree sap, and understood why I once ran across a four-lane highway to retrieve discarded beer cans.

Their histories barely resembled mine, yet our values aligned intimately. We did not hesitate to joke about bullet ants, gush about the versatility of tree bark, or discuss the destructive consequences of materialism. Together, we let our inner tree-huggers run free.

This essay captures the transformative power of community and shared values through the author's experience in the Ecuadorian rainforest. The opening sets a vivid scene, drawing the reader into the narrator's journey of joining a diverse group of strangers united by their passion for environmental conservation. By contrasting the indifference of their conservative suburban community with the shared purpose and enthusiasm of their newfound companions, the essay immediately establishes a theme of community and belonging. The examples of the group's enthusiasm and "inner tree-huggers" bring an authentic voice to the narrative.

In the body of the essay, the author skillfully portrays the camaraderie and mutual support within the group, despite their diverse backgrounds . The shared experiences of bird-watching, discussions about medicinal tree sap, and collective efforts towards environmental advocacy highlight the strength of their bond and the alignment of their values. Through anecdotes and dialogue, the author effectively conveys the sense of empowerment and inspiration derived from being part of such a community.

The essay additionally conveys the personal growth and transformation experienced by the author as a result of their time in the rainforest community. The realization that they can make a difference in the world, coupled with a newfound sense of purpose and determination, serves as a powerful conclusion to the narrative. The essay communicates the importance of community in shaping one's beliefs, values, and aspirations, while also highlighting the potential for individual agency and impact.

Where the essay could be strengthened is providing more insight into how this experience will shape the author's future contributions to building and leading communities. While it's impactful to convey the determination instilled to devote one's life to environmental advocacy, expanding on the specific ways the author hopes to foster community around this work would add depth. Additionally, reflecting on the personal growth sparked by stepping outside one's insular worldview could highlight the importance of diversity of perspectives. Overall, however, this is a strong essay that captures the power of an eye-opening experience bonding with others over shared values and passions.

3. Activism (Rochester)

To Nigerians,

It’s been eight years since we’ve been subjected to the tyranny of bad governance. Our medical systems have been destroyed, economy devaluated, and freedom of speech banished. But we need not worry for long. Just 5 years left!

By 2027, I will have explored the strategies behind successful revolutions in Prof. Meguid’s Introduction to Comparative Politics Class ( PSCI101) in my world politics cluster, equipping me to successfully lead us through the revolution we’ve eagerly awaited and install a political system that will ensure our happiness. With the help of the Greene Center, I will have gained practical experience of the biomedical engineering career field by interning at Corning’s biochemical department, enabling me to contribute to the rebuilding of our medical system. I will have developed a Parkinson-stabilizing device from my experience analyzing human motion with MATLAB in Professor Buckley’s BME 201-P class. I hope to later extend this device to cater for poliomyelitis, a disease that has plagued us since 1982. I will have strengthened my ability to put corruption under check through music by developing my soprano voice at Vocal point.

This essay, earning the author admission to the University of Rochester, blends a personal narrative with a vision for the future, demonstrating the author's determination to address the challenges faced by Nigeria through education and practical experience. The author begins by painting a stark picture of the current state of governance in Nigeria, highlighting the systemic issues that have plagued the country for years. This sets the stage for the author's ambitious plan to enact change within their homeland.

The author's strategic approach to addressing these issues is given a college admissions focus by outlining their academic and professional goals at the University of Rochester. By detailing specific courses, internships, and extracurricular activities, the author demonstrates a clear path towards acquiring the knowledge and skills necessary to lead a revolution and contribute to rebuilding Nigeria's medical system. This strategic planning reflects the author's commitment to effecting tangible change and underscores their preparedness for the challenges ahead.

To further strengthen its impact, the author could provide more context or examples of their previous activism or engagement with Nigerian issues, with clear links between the specific experiences and opportunities at the University of Rochester and their goals.

4. Taking Care of Siblings (Cornell)

He’s in my arms, the newest addition to the family. I’m too overwhelmed. “That’s why I wanted you to go to Bishop Loughlin,” she says, preparing baby bottles. “But ma, I chose Tech because I wanted to be challenged.” “Well, you’re going to have to deal with it,” she replies, adding, “Your aunt watched you when she was in high school.” “But ma, there are three of them. It’s hard!” Returning home from a summer program that cemented intellectual and social independence to find a new baby was not exactly thrilling. Add him to the toddler and seven-year-old sister I have and there’s no wonder why I sing songs from Blue’s Clues and The Backyardigans instead of sane seventeen-year-old activities. It’s never been simple; as a female and the oldest, I’m to significantly rear the children and clean up the shabby apartment before an ounce of pseudo freedom reaches my hands. If I can manage to get my toddler brother onto the city bus and take him home from daycare without snot on my shoulder, and if I can manage to take off his coat and sneakers without demonic screaming for no apparent reason, then it’s a good day. Only, waking up at three in the morning to work, the only free time I have, is not my cup of Starbucks.

The opening scene of the essay, where the author holds their newest sibling while their mother prepares baby bottles, immediately sets the tone for the essay and introduces the central theme of familial responsibility and sacrifice.

The author candidly reflects on the challenges of balancing their familial obligations with their desire for personal growth and independence. The author's frustration and sense of overwhelm are palpable as they navigate the demands of caring for multiple siblings while also trying to pursue their own goals and aspirations. The contrast between the author's responsibilities as the oldest sibling and their longing for "sane seventeen-year-old activities" effectively highlights the tension between duty and personal desires.

The message of the essay effectively communicates the author's resilience and determination in the face of adversity. Despite the challenges they face, the author demonstrates a sense of agency and resourcefulness, such as waking up at three in the morning to work and finding moments of freedom amidst their responsibilities. This resilience reflects the author's inner strength and determination to overcome obstacles and pursue their dreams.

5. East Asian Bibliophile / Not “Black Enough”

Growing up, my world was basketball. My summers were spent between the two solid black lines. My skin was consistently tan in splotches and ridden with random scratches. My wardrobe consisted mainly of track shorts, Nike shoes, and tournament t-shirts. Gatorade and Fun Dip were my pre-game snacks. The cacophony of rowdy crowds, ref whistles, squeaky shoes, and scoreboard buzzers was a familiar sound. I was the team captain of almost every team I played on—familiar with the Xs and Os of plays, commander of the court, and the coach’s right hand girl.

But that was only me on the surface.

Deep down I was an East-Asian influenced bibliophile and a Young Adult fiction writer.

Hidden in the cracks of a blossoming collegiate level athlete was a literary fiend. I devoured books in the daylight. I crafted stories at night time. After games, after practice, after conditioning I found nooks of solitude. Within these moments, I became engulfed in a world of my own creation. Initially, I only read young adult literature, but I grew to enjoy literary fiction and self-help: Kafka, Dostoevsky, Branden, Csikszentmihalyi. I expanded my bubble to Google+ critique groups, online discussion groups, blogs, writing competitions and clubs. I wrote my first novel in fifth grade, my second in seventh grade, and started my third in ninth grade. Reading was instinctual. Writing was impulsive.

In this essay, the complexities of identity and personal growth are presented through a multi-dimensional portrait of the author's cultural experiences and interests. The opening vividly describes the author's immersion in the world of basketball, showcasing their athleticism and leadership on the court . The essay quickly moves into substantive analysis, revealing the author's passion for literature and writing, as well as their deep connection to East Asian culture and philosophy.

Through anecdotes and reflections, the author skillfully juxtaposes their outward persona as an athlete with their internal world as a bibliophile and writer. This contrast highlights the complexity of identity and challenges stereotypes, demonstrating that individuals can possess a range of interests and talents beyond societal expectations. The author's journey of self-discovery, from devouring young adult literature to emulating authors like Haruki Murakami, adds depth to the narrative and underscores their intellectual curiosity and growth.

The internal and external conflicts faced by the author are developed in the essay body, including the pressure to conform to stereotypes and the challenges of balancing multiple passions. The author's experiences of being judged and bullied for not fitting into narrow expectations highlight the importance of embracing individuality and resisting societal norms. The author unpacks their overall resilience and determination to pursue their diverse interests despite obstacles, including overcoming ACL injuries and transitioning to homeschooling. By detailing their involvement in various extracurricular activities and nonprofit initiatives, the author demonstrates their desire to make a positive impact and empower others to reach their potential.

6. Instagram Post

On “Silent Siege Day,” many students in my high school joined the Students for Life club and wore red armbands with “LIFE” on them. As a non-Catholic in a Catholic school, I knew I had to be cautious in expressing my opinion on the abortion debate. However, when I saw that all of the armband-bearing students were male, I could not stay silent.

I wrote on Instagram, “pro-choice does not necessarily imply pro-abortion; it means that we respect a woman’s fundamental right to make her own choice regarding her own body.”

Some of my peers expressed support but others responded by calling me a dumb bitch, among other names. When I demanded an apology for the name-calling, I was told I needed to learn to take a joke: “you have a lot of anger, I think you need a boyfriend.” Another one of my peers apparently thought the post was sarcastic (?) and said “I didn’t know women knew how to use sarcasm.”

One by one, I responded. I was glad to have sparked discussion, but by midnight, I was mentally and emotionally exhausted.

This is a strong essay, effectively recounting a journey of self-discovery and activism, beginning with a pivotal moment of speaking out against the majority opinion on abortion rights at their Catholic high school. The author's courage in challenging societal norms and expressing their beliefs, despite potential backlash, is evident from the outset. B y sharing a personal anecdote of facing criticism and derogatory comments on social media, the author gives a clear look at the emotional toll of standing up for one's beliefs in the face of adversity.

The essay integrates the author's reflections on their evolving understanding of social justice and feminism, sparked by their experiences and research following "The Post." Through engaging with feminist literature and studying historical movements like the Civil Rights Movement , the author demonstrates a growing awareness of systemic inequalities and the importance of dissent in effecting change. The author's decision to volunteer with Girls on the Run and engage in political activism, such as signing petitions and advocating against discriminatory policies, underscores their commitment to advancing social justice beyond their personal experiences.

This ambition reflects the author's desire to contribute to positive societal change and advocate for marginalized communities on a broader scale. The essay effectively conveys a sense of optimism and determination for the future, encapsulated by the author's vision of becoming the first Asian woman on the Supreme Court.

The labels that I bear are hung from me like branches on a tree: disruptive, energetic, creative, loud, fun, easily distracted, clever, a space cadet, a problem … and that tree has roots called ADHD. The diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder made a lot of sense when it was handed down. I was diagnosed later than other children, probably owing to my sex, which is female; people with ADHD who are female often present in different ways from our male counterparts and are just as often missed by psychiatrists.

Over the years, these labels served as either a badge or a bludgeon, keeping me from certain activities, ruining friendships, or becoming elements of my character that I love about myself and have brought me closer to people I care about. Every trait is a double-edged sword.

The years that brought me to where I am now have been strange and uneven. I had a happy childhood, even if I was a “handful” for my parents. As I grew and grew in awareness of how I could be a problem, I developed anxiety over behavior I simply couldn’t control. With the diagnosis, I received relief, and yet, soon I was thinking of myself as broken, and I quickly attributed every setback to my neurological condition.

The author begins the essay by candidly acknowledging the various labels and stereotypes associated with their condition, illustrating the challenges of navigating societal perceptions and self-perception. By highlighting the gendered aspect of ADHD diagnosis and its impact on their experiences, the author sheds light on the complexity of neurodiversity and the importance of recognition and understanding.

Throughout the essay, the author reflects on the dual nature of their ADHD traits, acknowledging both the struggles and strengths associated with their condition. They eloquently describe how their ADHD has influenced various aspects of their life, from friendships to academic performance to sports achievements. By sharing personal anecdotes and reflections, the essay effectively captures the author's journey of self-acceptance and reframing their perspective on their ADHD.

The author acknowledges the initial sense of relief upon receiving their diagnosis, followed by feelings of brokenness and self-doubt. However, through introspection and self-compassion, the author ultimately embraces their neurodiversity as a fundamental aspect of their identity. This shift in mindset from viewing their brain as "wrong" to recognizing its uniqueness and resilience is a powerful testament to the author's growth and resilience.

By volunteering at a mental health resource center and advocating for the normalization of neurodiversity, the author demonstrates a desire to create a more inclusive and compassionate society. The essay effectively communicates a message of empathy, acceptance, and celebration of diversity, encouraging readers to embrace their own differences and those of others.

Links to full essays:

Essay Three

Essay Seven