Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- 10 Research Question Examples to Guide Your Research Project

10 Research Question Examples to Guide your Research Project

Published on October 30, 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on October 19, 2023.

The research question is one of the most important parts of your research paper , thesis or dissertation . It’s important to spend some time assessing and refining your question before you get started.

The exact form of your question will depend on a few things, such as the length of your project, the type of research you’re conducting, the topic , and the research problem . However, all research questions should be focused, specific, and relevant to a timely social or scholarly issue.

Once you’ve read our guide on how to write a research question , you can use these examples to craft your own.

| Research question | Explanation |

|---|---|

| The first question is not enough. The second question is more , using . | |

| Starting with “why” often means that your question is not enough: there are too many possible answers. By targeting just one aspect of the problem, the second question offers a clear path for research. | |

| The first question is too broad and subjective: there’s no clear criteria for what counts as “better.” The second question is much more . It uses clearly defined terms and narrows its focus to a specific population. | |

| It is generally not for academic research to answer broad normative questions. The second question is more specific, aiming to gain an understanding of possible solutions in order to make informed recommendations. | |

| The first question is too simple: it can be answered with a simple yes or no. The second question is , requiring in-depth investigation and the development of an original argument. | |

| The first question is too broad and not very . The second question identifies an underexplored aspect of the topic that requires investigation of various to answer. | |

| The first question is not enough: it tries to address two different (the quality of sexual health services and LGBT support services). Even though the two issues are related, it’s not clear how the research will bring them together. The second integrates the two problems into one focused, specific question. | |

| The first question is too simple, asking for a straightforward fact that can be easily found online. The second is a more question that requires and detailed discussion to answer. | |

| ? dealt with the theme of racism through casting, staging, and allusion to contemporary events? | The first question is not — it would be very difficult to contribute anything new. The second question takes a specific angle to make an original argument, and has more relevance to current social concerns and debates. |

| The first question asks for a ready-made solution, and is not . The second question is a clearer comparative question, but note that it may not be practically . For a smaller research project or thesis, it could be narrowed down further to focus on the effectiveness of drunk driving laws in just one or two countries. |

Note that the design of your research question can depend on what method you are pursuing. Here are a few options for qualitative, quantitative, and statistical research questions.

| Type of research | Example question |

|---|---|

| Qualitative research question | |

| Quantitative research question | |

| Statistical research question |

Other interesting articles

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, October 19). 10 Research Question Examples to Guide your Research Project. Scribbr. Retrieved June 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-question-examples/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, how to choose a dissertation topic | 8 steps to follow, evaluating sources | methods & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Research Question Examples 🧑🏻🏫

25+ Practical Examples & Ideas To Help You Get Started

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | October 2023

A well-crafted research question (or set of questions) sets the stage for a robust study and meaningful insights. But, if you’re new to research, it’s not always clear what exactly constitutes a good research question. In this post, we’ll provide you with clear examples of quality research questions across various disciplines, so that you can approach your research project with confidence!

Research Question Examples

- Psychology research questions

- Business research questions

- Education research questions

- Healthcare research questions

- Computer science research questions

Examples: Psychology

Let’s start by looking at some examples of research questions that you might encounter within the discipline of psychology.

How does sleep quality affect academic performance in university students?

This question is specific to a population (university students) and looks at a direct relationship between sleep and academic performance, both of which are quantifiable and measurable variables.

What factors contribute to the onset of anxiety disorders in adolescents?

The question narrows down the age group and focuses on identifying multiple contributing factors. There are various ways in which it could be approached from a methodological standpoint, including both qualitatively and quantitatively.

Do mindfulness techniques improve emotional well-being?

This is a focused research question aiming to evaluate the effectiveness of a specific intervention.

How does early childhood trauma impact adult relationships?

This research question targets a clear cause-and-effect relationship over a long timescale, making it focused but comprehensive.

Is there a correlation between screen time and depression in teenagers?

This research question focuses on an in-demand current issue and a specific demographic, allowing for a focused investigation. The key variables are clearly stated within the question and can be measured and analysed (i.e., high feasibility).

Examples: Business/Management

Next, let’s look at some examples of well-articulated research questions within the business and management realm.

How do leadership styles impact employee retention?

This is an example of a strong research question because it directly looks at the effect of one variable (leadership styles) on another (employee retention), allowing from a strongly aligned methodological approach.

What role does corporate social responsibility play in consumer choice?

Current and precise, this research question can reveal how social concerns are influencing buying behaviour by way of a qualitative exploration.

Does remote work increase or decrease productivity in tech companies?

Focused on a particular industry and a hot topic, this research question could yield timely, actionable insights that would have high practical value in the real world.

How do economic downturns affect small businesses in the homebuilding industry?

Vital for policy-making, this highly specific research question aims to uncover the challenges faced by small businesses within a certain industry.

Which employee benefits have the greatest impact on job satisfaction?

By being straightforward and specific, answering this research question could provide tangible insights to employers.

Examples: Education

Next, let’s look at some potential research questions within the education, training and development domain.

How does class size affect students’ academic performance in primary schools?

This example research question targets two clearly defined variables, which can be measured and analysed relatively easily.

Do online courses result in better retention of material than traditional courses?

Timely, specific and focused, answering this research question can help inform educational policy and personal choices about learning formats.

What impact do US public school lunches have on student health?

Targeting a specific, well-defined context, the research could lead to direct changes in public health policies.

To what degree does parental involvement improve academic outcomes in secondary education in the Midwest?

This research question focuses on a specific context (secondary education in the Midwest) and has clearly defined constructs.

What are the negative effects of standardised tests on student learning within Oklahoma primary schools?

This research question has a clear focus (negative outcomes) and is narrowed into a very specific context.

Need a helping hand?

Examples: Healthcare

Shifting to a different field, let’s look at some examples of research questions within the healthcare space.

What are the most effective treatments for chronic back pain amongst UK senior males?

Specific and solution-oriented, this research question focuses on clear variables and a well-defined context (senior males within the UK).

How do different healthcare policies affect patient satisfaction in public hospitals in South Africa?

This question is has clearly defined variables and is narrowly focused in terms of context.

Which factors contribute to obesity rates in urban areas within California?

This question is focused yet broad, aiming to reveal several contributing factors for targeted interventions.

Does telemedicine provide the same perceived quality of care as in-person visits for diabetes patients?

Ideal for a qualitative study, this research question explores a single construct (perceived quality of care) within a well-defined sample (diabetes patients).

Which lifestyle factors have the greatest affect on the risk of heart disease?

This research question aims to uncover modifiable factors, offering preventive health recommendations.

Examples: Computer Science

Last but certainly not least, let’s look at a few examples of research questions within the computer science world.

What are the perceived risks of cloud-based storage systems?

Highly relevant in our digital age, this research question would align well with a qualitative interview approach to better understand what users feel the key risks of cloud storage are.

Which factors affect the energy efficiency of data centres in Ohio?

With a clear focus, this research question lays a firm foundation for a quantitative study.

How do TikTok algorithms impact user behaviour amongst new graduates?

While this research question is more open-ended, it could form the basis for a qualitative investigation.

What are the perceived risk and benefits of open-source software software within the web design industry?

Practical and straightforward, the results could guide both developers and end-users in their choices.

Remember, these are just examples…

In this post, we’ve tried to provide a wide range of research question examples to help you get a feel for what research questions look like in practice. That said, it’s important to remember that these are just examples and don’t necessarily equate to good research topics . If you’re still trying to find a topic, check out our topic megalist for inspiration.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- News & Highlights

- Publications and Documents

- Postgraduate Education

- Browse Our Courses

- C/T Research Academy

- K12 Investigator Training

- Harvard Catalyst On-Demand

- Translational Innovator

- SMART IRB Reliance Request

- Biostatistics Consulting

- Regulatory Support

- Pilot Funding

- Informatics Program

- Community Engagement

- Diversity Inclusion

- Research Enrollment and Diversity

- Harvard Catalyst Profiles

Creating a Good Research Question

- Advice & Growth

- Process in Practice

Successful translation of research begins with a strong question. How do you get started? How do good research questions evolve? And where do you find inspiration to generate good questions in the first place? It’s helpful to understand existing frameworks, guidelines, and standards, as well as hear from researchers who utilize these strategies in their own work.

In the fall and winter of 2020, Naomi Fisher, MD, conducted 10 interviews with clinical and translational researchers at Harvard University and affiliated academic healthcare centers, with the purpose of capturing their experiences developing good research questions. The researchers featured in this project represent various specialties, drawn from every stage of their careers. Below you will find clips from their interviews and additional resources that highlight how to get started, as well as helpful frameworks and factors to consider. Additionally, visit the Advice & Growth section to hear candid advice and explore the Process in Practice section to hear how researchers have applied these recommendations to their published research.

- Naomi Fisher, MD , is associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School (HMS), and clinical staff at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH). Fisher is founder and director of Hypertension Services and the Hypertension Specialty Clinic at the BWH, where she is a renowned endocrinologist. She serves as a faculty director for communication-related Boundary-Crossing Skills for Research Careers webinar sessions and the Writing and Communication Center .

- Christopher Gibbons, MD , is associate professor of neurology at HMS, and clinical staff at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) and Joslin Diabetes Center. Gibbons’ research focus is on peripheral and autonomic neuropathies.

- Clare Tempany-Afdhal, MD , is professor of radiology at HMS and the Ferenc Jolesz Chair of Research, Radiology at BWH. Her major areas of research are MR imaging of the pelvis and image- guided therapy.

- David Sykes, MD, PhD , is assistant professor of medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), he is also principal investigator at the Sykes Lab at MGH. His special interest area is rare hematologic conditions.

- Elliot Israel, MD , is professor of medicine at HMS, director of the Respiratory Therapy Department, the director of clinical research in the Pulmonary and Critical Care Medical Division and associate physician at BWH. Israel’s research interests include therapeutic interventions to alter asthmatic airway hyperactivity and the role of arachidonic acid metabolites in airway narrowing.

- Jonathan Williams, MD, MMSc , is assistant professor of medicine at HMS, and associate physician at BWH. He focuses on endocrinology, specifically unravelling the intricate relationship between genetics and environment with respect to susceptibility to cardiometabolic disease.

- Junichi Tokuda, PhD , is associate professor of radiology at HMS, and is a research scientist at the Department of Radiology, BWH. Tokuda is particularly interested in technologies to support image-guided “closed-loop” interventions. He also serves as a principal investigator leading several projects funded by the National Institutes of Health and industry.

- Osama Rahma, MD , is assistant professor of medicine at HMS and clinical staff member in medical oncology at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI). Rhama is currently a principal investigator at the Center for Immuno-Oncology and Gastroenterology Cancer Center at DFCI. His research focus is on drug development of combinational immune therapeutics.

- Sharmila Dorbala, MD, MPH , is professor of radiology at HMS and clinical staff at BWH in cardiovascular medicine and radiology. She is also the president of the American Society of Nuclear Medicine. Dorbala’s specialty is using nuclear medicine for cardiovascular discoveries.

- Subha Ramani, PhD, MBBS, MMed , is associate professor of medicine at HMS, as well as associate physician in the Division of General Internal Medicine and Primary Care at BWH. Ramani’s scholarly interests focus on innovative approaches to teaching, learning and assessment of clinical trainees, faculty development in teaching, and qualitative research methods in medical education.

- Ursula Kaiser, MD , is professor at HMS and chief of the Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Hypertension, and senior physician at BWH. Kaiser’s research focuses on understanding the molecular mechanisms by which pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone regulates the expression of luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone genes.

Insights on Creating a Good Research Question

Play Junichi Tokuda video

Play Ursula Kaiser video

Start Successfully: Build the Foundation of a Good Research Question

Start Successfully Resources

Ideation in Device Development: Finding Clinical Need Josh Tolkoff, MS A lecture explaining the critical importance of identifying a compelling clinical need before embarking on a research project. Play Ideation in Device Development video .

Radical Innovation Jeff Karp, PhD This ThinkResearch podcast episode focuses on one researcher’s approach using radical simplicity to break down big problems and questions. Play Radical Innovation .

Using Healthcare Data: How can Researchers Come up with Interesting Questions? Anupam Jena, MD, PhD Another ThinkResearch podcast episode addresses how to discover good research questions by using a backward design approach which involves analyzing big data and allowing the research question to unfold from findings. Play Using Healthcare Data .

Important Factors: Consider Feasibility and Novelty

Refining Your Research Question

Play video of Clare Tempany-Afdhal

Play Elliott Israel video

Frameworks and Structure: Evaluate Research Questions Using Tools and Techniques

Frameworks and Structure Resources

Designing Clinical Research Hulley et al. A comprehensive and practical guide to clinical research, including the FINER framework for evaluating research questions. Learn more about the book .

Translational Medicine Library Guide Queens University Library An introduction to popular frameworks for research questions, including FINER and PICO. Review translational medicine guide .

Asking a Good T3/T4 Question Niteesh K. Choudhry, MD, PhD This video explains the PICO framework in practice as participants in a workshop propose research questions that compare interventions. Play Asking a Good T3/T4 Question video

Introduction to Designing & Conducting Mixed Methods Research An online course that provides a deeper dive into mixed methods’ research questions and methodologies. Learn more about the course

Network and Support: Find the Collaborators and Stakeholders to Help Evaluate Research Questions

Network & Support Resource

Bench-to-bedside, Bedside-to-bench Christopher Gibbons, MD In this lecture, Gibbons shares his experience of bringing research from bench to bedside, and from bedside to bench. His talk highlights the formation and evolution of research questions based on clinical need. Play Bench-to-bedside.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research process

- Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples

Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples

Published on 30 October 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 12 December 2023.

A research question pinpoints exactly what you want to find out in your work. A good research question is essential to guide your research paper , dissertation , or thesis .

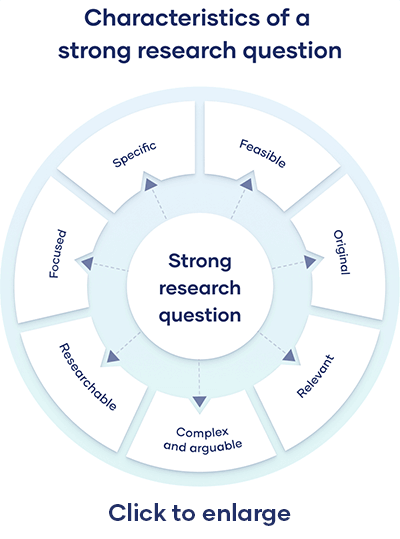

All research questions should be:

- Focused on a single problem or issue

- Researchable using primary and/or secondary sources

- Feasible to answer within the timeframe and practical constraints

- Specific enough to answer thoroughly

- Complex enough to develop the answer over the space of a paper or thesis

- Relevant to your field of study and/or society more broadly

Table of contents

How to write a research question, what makes a strong research question, research questions quiz, frequently asked questions.

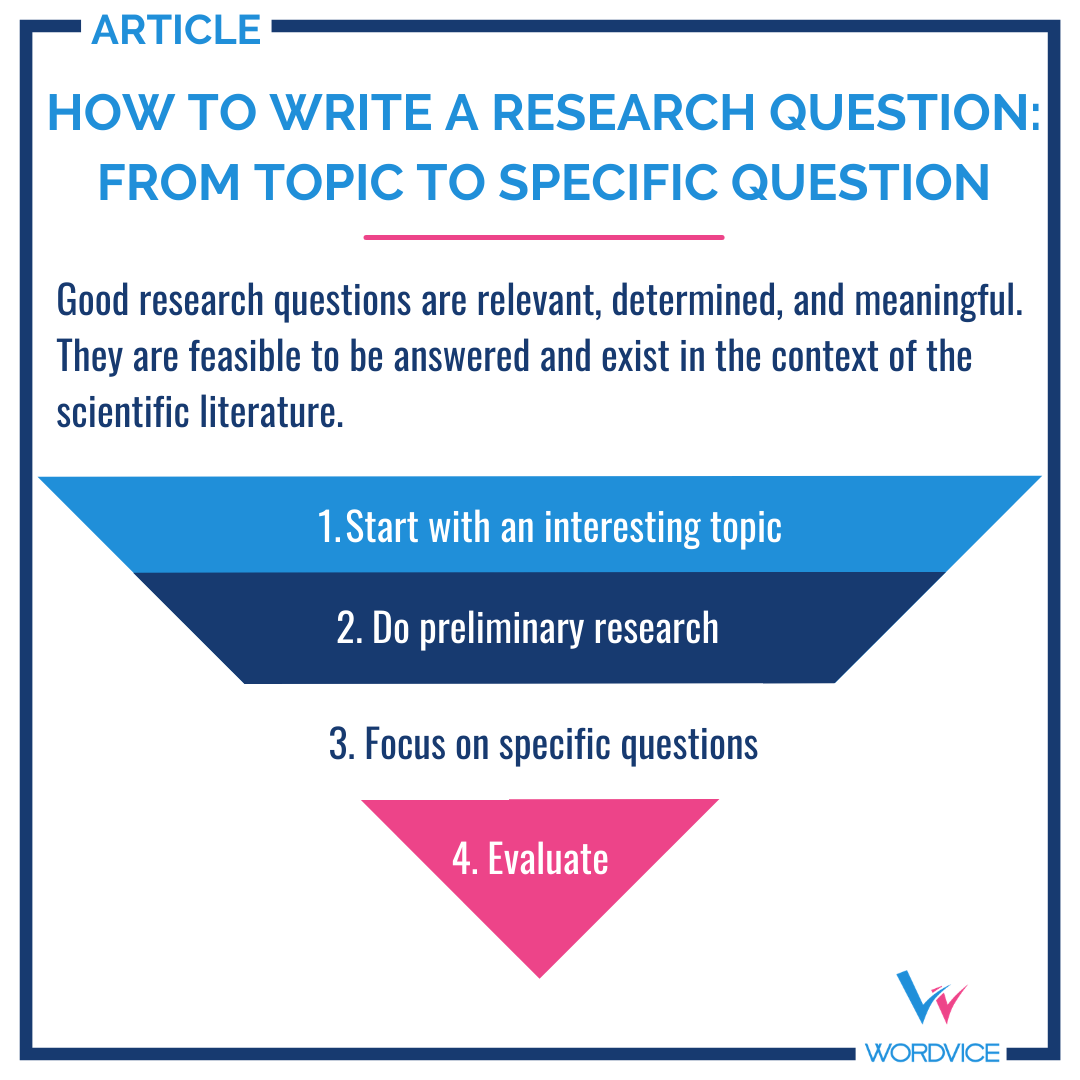

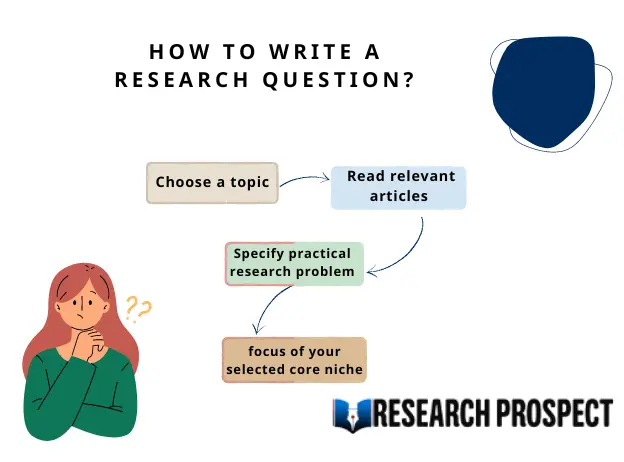

You can follow these steps to develop a strong research question:

- Choose your topic

- Do some preliminary reading about the current state of the field

- Narrow your focus to a specific niche

- Identify the research problem that you will address

The way you frame your question depends on what your research aims to achieve. The table below shows some examples of how you might formulate questions for different purposes.

| Research question formulations | |

|---|---|

| Describing and exploring | |

| Explaining and testing | |

| Evaluating and acting |

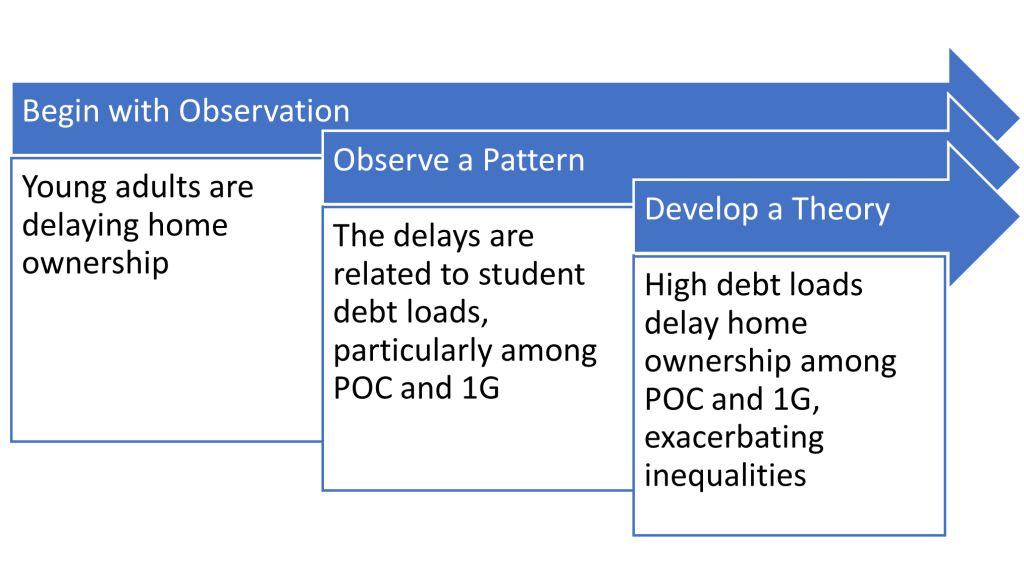

Using your research problem to develop your research question

| Example research problem | Example research question(s) |

|---|---|

| Teachers at the school do not have the skills to recognize or properly guide gifted children in the classroom. | What practical techniques can teachers use to better identify and guide gifted children? |

| Young people increasingly engage in the ‘gig economy’, rather than traditional full-time employment. However, it is unclear why they choose to do so. | What are the main factors influencing young people’s decisions to engage in the gig economy? |

Note that while most research questions can be answered with various types of research , the way you frame your question should help determine your choices.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Research questions anchor your whole project, so it’s important to spend some time refining them. The criteria below can help you evaluate the strength of your research question.

Focused and researchable

| Criteria | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Focused on a single topic | Your central research question should work together with your research problem to keep your work focused. If you have multiple questions, they should all clearly tie back to your central aim. |

| Answerable using | Your question must be answerable using and/or , or by reading scholarly sources on the topic to develop your argument. If such data is impossible to access, you likely need to rethink your question. |

| Not based on value judgements | Avoid subjective words like , , and . These do not give clear criteria for answering the question. |

Feasible and specific

| Criteria | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Answerable within practical constraints | Make sure you have enough time and resources to do all research required to answer your question. If it seems you will not be able to gain access to the data you need, consider narrowing down your question to be more specific. |

| Uses specific, well-defined concepts | All the terms you use in the research question should have clear meanings. Avoid vague language, jargon, and too-broad ideas. |

| Does not demand a conclusive solution, policy, or course of action | Research is about informing, not instructing. Even if your project is focused on a practical problem, it should aim to improve understanding rather than demand a ready-made solution. |

Complex and arguable

| Criteria | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Cannot be answered with or | Closed-ended, / questions are too simple to work as good research questions—they don’t provide enough scope for robust investigation and discussion. |

| Cannot be answered with easily-found facts | If you can answer the question through a single Google search, book, or article, it is probably not complex enough. A good research question requires original data, synthesis of multiple sources, and original interpretation and argumentation prior to providing an answer. |

Relevant and original

| Criteria | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Addresses a relevant problem | Your research question should be developed based on initial reading around your . It should focus on addressing a problem or gap in the existing knowledge in your field or discipline. |

| Contributes to a timely social or academic debate | The question should aim to contribute to an existing and current debate in your field or in society at large. It should produce knowledge that future researchers or practitioners can later build on. |

| Has not already been answered | You don’t have to ask something that nobody has ever thought of before, but your question should have some aspect of originality. For example, you can focus on a specific location, or explore a new angle. |

The way you present your research problem in your introduction varies depending on the nature of your research paper . A research paper that presents a sustained argument will usually encapsulate this argument in a thesis statement .

A research paper designed to present the results of empirical research tends to present a research question that it seeks to answer. It may also include a hypothesis – a prediction that will be confirmed or disproved by your research.

As you cannot possibly read every source related to your topic, it’s important to evaluate sources to assess their relevance. Use preliminary evaluation to determine whether a source is worth examining in more depth.

This involves:

- Reading abstracts , prefaces, introductions , and conclusions

- Looking at the table of contents to determine the scope of the work

- Consulting the index for key terms or the names of important scholars

An essay isn’t just a loose collection of facts and ideas. Instead, it should be centered on an overarching argument (summarised in your thesis statement ) that every part of the essay relates to.

The way you structure your essay is crucial to presenting your argument coherently. A well-structured essay helps your reader follow the logic of your ideas and understand your overall point.

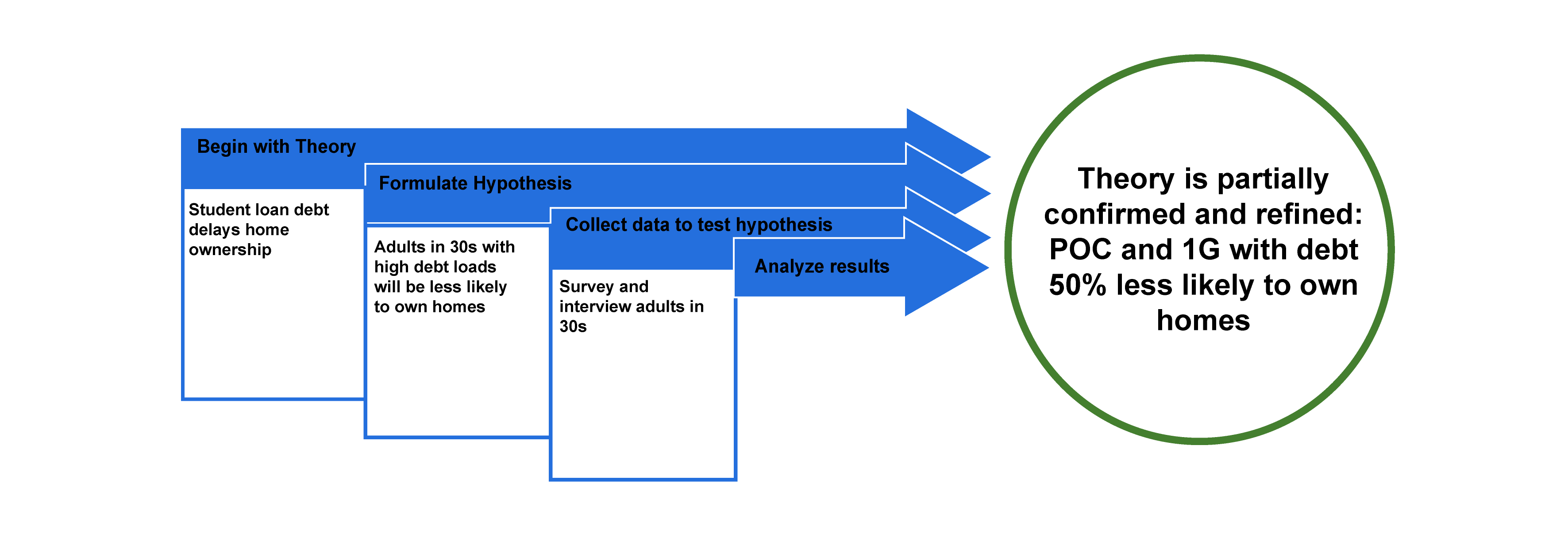

A research hypothesis is your proposed answer to your research question. The research hypothesis usually includes an explanation (‘ x affects y because …’).

A statistical hypothesis, on the other hand, is a mathematical statement about a population parameter. Statistical hypotheses always come in pairs: the null and alternative hypotheses. In a well-designed study , the statistical hypotheses correspond logically to the research hypothesis.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, December 12). Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 9 June 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/the-research-process/research-question/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, how to write a results section | tips & examples, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How To Write a Research Question

Academic writing and research require a distinct focus and direction. A well-designed research question gives purpose and clarity to your research. In addition, it helps your readers understand the issue you are trying to address and explore.

Every time you want to know more about a subject, you will pose a question. The same idea is used in research as well. You must pose a question in order to effectively address a research problem. That's why the research question is an integral part of the research process. Additionally, it offers the author writing and reading guidelines, be it qualitative research or quantitative research.

In your research paper , you must single out just one issue or problem. The specific issue or claim you wish to address should be included in your thesis statement in order to clarify your main argument.

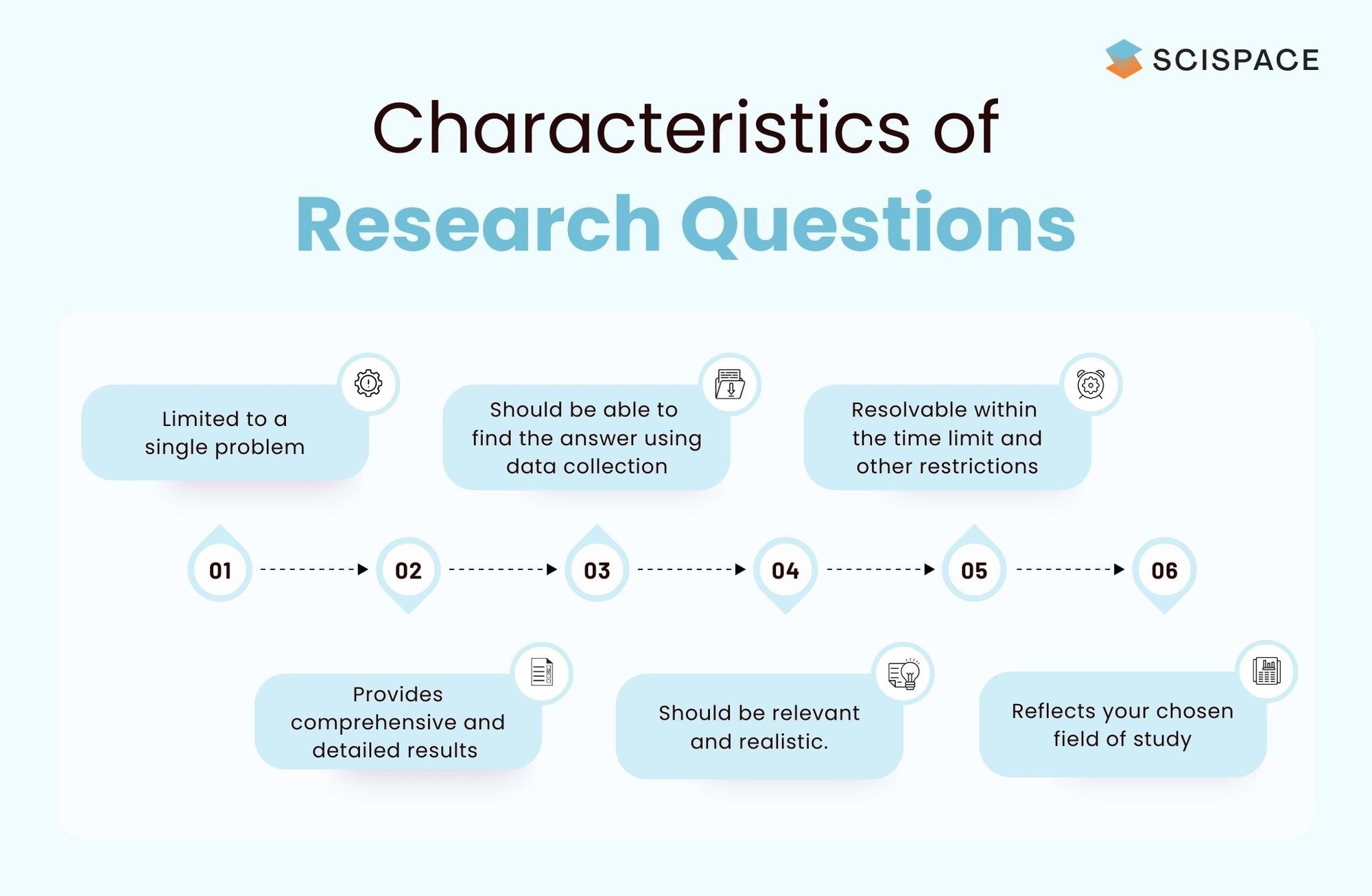

A good research question must have the following characteristics.

- Should include only one problem in the research question

- Should be able to find the answer using primary data and secondary data sources

- Should be possible to resolve within the given time and other constraints

- Detailed and in-depth results should be achievable

- Should be relevant and realistic.

- It should relate to your chosen area of research

While a larger project, like a thesis, might have several research questions to address, each one should be directed at your main area of study. Of course, you can use different research designs and research methods (qualitative research or quantitative research) to address various research questions. However, they must all be pertinent to the study's objectives.

What is a Research Question?

A research question is an inquiry that the research attempts to answer. It is the heart of the systematic investigation. Research questions are the most important step in any research project. In essence, it initiates the research project and establishes the pace for the specific research A research question is:

- Clear : It provides enough detail that the audience understands its purpose without any additional explanation.

- Focused : It is so specific that it can be addressed within the time constraints of the writing task.

- Succinct: It is written in the shortest possible words.

- Complex : It is not possible to answer it with a "yes" or "no", but requires analysis and synthesis of ideas before somebody can create a solution.

- Argumental : Its potential answers are open for debate rather than accepted facts.

A good research question usually focuses on the research and determines the research design, methodology, and hypothesis. It guides all phases of inquiry, data collection, analysis, and reporting. You should gather valuable information by asking the right questions.

Why are Research Questions so important?

Regardless of whether it is a qualitative research or quantitative research project, research questions provide writers and their audience with a way to navigate the writing and research process. Writers can avoid "all-about" papers by asking straightforward and specific research questions that help them focus on their research and support a specific thesis.

Types of Research Questions

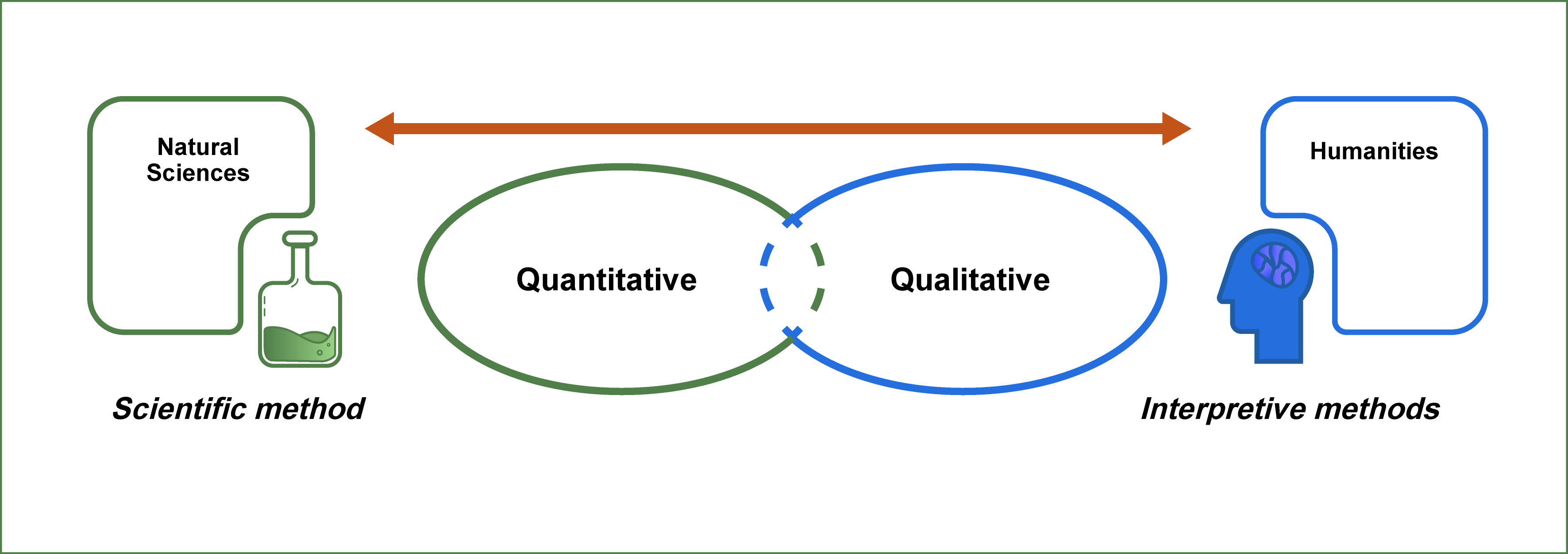

There are two types of research: Qualitative research and Quantitative research . There must be research questions for every type of research. Your research question will be based on the type of research you want to conduct and the type of data collection.

The first step in designing research involves identifying a gap and creating a focused research question.

Below is a list of common research questions that can be used in a dissertation. Keep in mind that these are merely illustrations of typical research questions used in dissertation projects. The real research questions themselves might be more difficult.

Research Question Type | Question |

Descriptive | What are the properties of A? |

Comparative | What are the similarities and distinctions between A and B? |

Correlational | What can you do to correlate variables A and B? |

Exploratory | What factors affect the rate of C's growth? Are A and B also influencing C? |

Explanatory | What are the causes for C? What does A do to B? What's causing D? |

Evaluation | What is the impact of C? What role does B have? What are the benefits and drawbacks of A? |

Action-Based | What can you do to improve X? |

Example Research Questions

The following are a few examples of research questions and research problems to help you understand how research questions can be created for a particular research problem.

Problem | Question |

Due to poor revenue collection, a small-sized company ('A') in the UK cannot allocate a marketing budget next year. | What practical steps can the company take to increase its revenue? |

Many graduates are now working as freelancers even though they have degrees from well-respected academic institutions. But what's the reason these young people choose to work in this field? | Why do fresh graduates choose to work for themselves rather than full-time? What are the benefits and drawbacks of the gig economy? What do age, gender, and academic qualifications do with people's perceptions of freelancing? |

Steps to Write Research Questions

You can focus on the issue or research gaps you're attempting to solve by using the research questions as a direction.

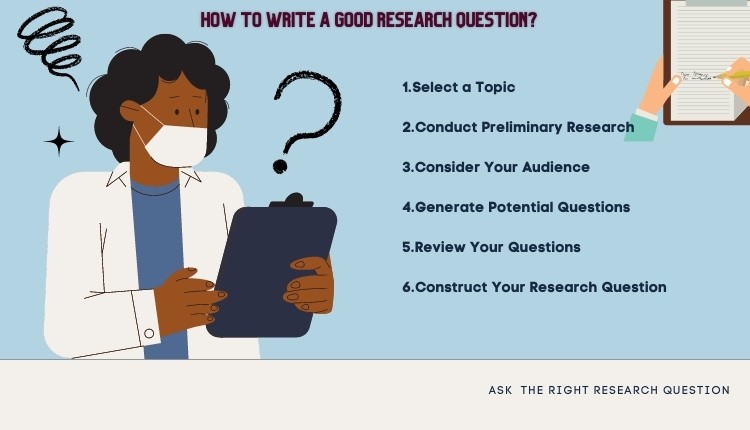

If you're unsure how to go about writing a good research question, these are the steps to follow in the process:

- Select an interesting topic Always choose a topic that interests you. Because if your curiosity isn’t aroused by a subject, you’ll have a hard time conducting research around it. Alos, it’s better that you pick something that’s neither too narrow or too broad.

- Do preliminary research on the topic Search for relevant literature to gauge what problems have already been tackled by scholars. You can do that conveniently through repositories like Scispace , where you’ll find millions of papers in one place. Once you do find the papers you’re looking for, try our reading assistant, SciSpace Copilot to get simple explanations for the paper . You’ll be able to quickly understand the abstract, find the key takeaways, and the main arguments presented in the paper. This will give you a more contextual understanding of your subject and you’ll have an easier time identifying knowledge gaps in your discipline.

Also: ChatPDF vs. SciSpace Copilot: Unveiling the best tool for your research

- Consider your audience It is essential to understand your audience to develop focused research questions for essays or dissertations. When narrowing down your topic, you can identify aspects that might interest your audience.

- Ask questions Asking questions will give you a deeper understanding of the topic. Evaluate your question through the What, Why, When, How, and other open-ended questions assessment.

- Assess your question Once you have created a research question, assess its effectiveness to determine if it is useful for the purpose. Refine and revise the dissertation research question multiple times.

Additionally, use this list of questions as a guide when formulating your research question.

Are you able to answer a specific research question? After identifying a gap in research, it would be helpful to formulate the research question. And this will allow the research to solve a part of the problem. Is your research question clear and centered on the main topic? It is important that your research question should be specific and related to your central goal. Are you tackling a difficult research question? It is not possible to answer the research question with a simple yes or no. The problem requires in-depth analysis. It is often started with "How" and "Why."

Start your research Once you have completed your dissertation research questions, it is time to review the literature on similar topics to discover different perspectives.

Strong Research Question Samples

Uncertain: How should social networking sites work on the hatred that flows through their platform?

Certain: What should social media sites like Twitter or Facebook do to address the harm they are causing?

This unclear question does not specify the social networking sites that are being used or what harm they might be causing. In addition, this question assumes that the "harm" has been proven and/or accepted. This version is more specific and identifies the sites (Twitter, Facebook), the type and extent of harm (privacy concerns), and who might be suffering from that harm (users). Effective research questions should not be ambiguous or interpreted.

Unfocused: What are the effects of global warming on the environment?

Focused: What are the most important effects of glacial melting in Antarctica on penguins' lives?

This broad research question cannot be addressed in a book, let alone a college-level paper. Focused research targets a specific effect of global heating (glacial melting), an area (Antarctica), or a specific animal (penguins). The writer must also decide which effect will have the greatest impact on the animals affected. If in doubt, narrow down your research question to the most specific possible.

Too Simple: What are the U.S. doctors doing to treat diabetes?

Appropriately complex: Which factors, if any, are most likely to predict a person's risk of developing diabetes?

This simple version can be found online. It is easy to answer with a few facts. The second, more complicated version of this question is divided into two parts. It is thought-provoking and requires extensive investigation as well as evaluation by the author. So, ensure that a quick Google search should not answer your research question.

How to write a strong Research Question?

The foundation of all research is the research question. You should therefore spend as much time as necessary to refine your research question based on various data.

You can conduct your research more efficiently and analyze your results better if you have great research questions for your dissertation, research paper , or essay .

The following criteria can help you evaluate the strength and importance of your research question and can be used to determine the strength of your research question:

- Researchable

- It should only cover one issue.

- A subjective judgment should not be included in the question.

- It can be answered with data analysis and research.

- Specific and Practical

- It should not contain a plan of action, policy, or solution.

- It should be clearly defined

- Within research limits

- Complex and Arguable

- It shouldn't be difficult to answer.

- To find the truth, you need in-depth knowledge

- Allows for discussion and deliberation

- Original and Relevant

- It should be in your area of study

- Its results should be measurable

- It should be original

Conclusion - How to write Research Questions?

Research questions provide a clear guideline for research. One research question may be part of a larger project, such as a dissertation. However, each question should only focus on one topic.

Research questions must be answerable, practical, specific, and applicable to your field. The research type that you use to base your research questions on will determine the research topic. You can start by selecting an interesting topic and doing preliminary research. Then, you can begin asking questions, evaluating your questions, and start your research.

Now it's easier than ever to streamline your research workflow with SciSpace ResearchGPT . Its integrated, comprehensive end-to-end platform for research allows scholars to easily discover, read, write and publish their research and fosters collaboration.

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

How to Write a Research Question: Types and Examples

The first step in any research project is framing the research question. It can be considered the core of any systematic investigation as the research outcomes are tied to asking the right questions. Thus, this primary interrogation point sets the pace for your research as it helps collect relevant and insightful information that ultimately influences your work.

Typically, the research question guides the stages of inquiry, analysis, and reporting. Depending on the use of quantifiable or quantitative data, research questions are broadly categorized into quantitative or qualitative research questions. Both types of research questions can be used independently or together, considering the overall focus and objectives of your research.

What is a research question?

A research question is a clear, focused, concise, and arguable question on which your research and writing are centered. 1 It states various aspects of the study, including the population and variables to be studied and the problem the study addresses. These questions also set the boundaries of the study, ensuring cohesion.

Designing the research question is a dynamic process where the researcher can change or refine the research question as they review related literature and develop a framework for the study. Depending on the scale of your research, the study can include single or multiple research questions.

A good research question has the following features:

- It is relevant to the chosen field of study.

- The question posed is arguable and open for debate, requiring synthesizing and analysis of ideas.

- It is focused and concisely framed.

- A feasible solution is possible within the given practical constraint and timeframe.

A poorly formulated research question poses several risks. 1

- Researchers can adopt an erroneous design.

- It can create confusion and hinder the thought process, including developing a clear protocol.

- It can jeopardize publication efforts.

- It causes difficulty in determining the relevance of the study findings.

- It causes difficulty in whether the study fulfils the inclusion criteria for systematic review and meta-analysis. This creates challenges in determining whether additional studies or data collection is needed to answer the question.

- Readers may fail to understand the objective of the study. This reduces the likelihood of the study being cited by others.

Now that you know “What is a research question?”, let’s look at the different types of research questions.

Types of research questions

Depending on the type of research to be done, research questions can be classified broadly into quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods studies. Knowing the type of research helps determine the best type of research question that reflects the direction and epistemological underpinnings of your research.

The structure and wording of quantitative 2 and qualitative research 3 questions differ significantly. The quantitative study looks at causal relationships, whereas the qualitative study aims at exploring a phenomenon.

- Quantitative research questions:

- Seeks to investigate social, familial, or educational experiences or processes in a particular context and/or location.

- Answers ‘how,’ ‘what,’ or ‘why’ questions.

- Investigates connections, relations, or comparisons between independent and dependent variables.

Quantitative research questions can be further categorized into descriptive, comparative, and relationship, as explained in the Table below.

| Descriptive research questions | These measure the responses of a study’s population toward a particular question or variable. Common descriptive research questions will begin with “How much?”, “How regularly?”, “What percentage?”, “What time?”, “What is?” Research question example: How often do you buy mobile apps for learning purposes? |

| Comparative research questions | These investigate differences between two or more groups for an outcome variable. For instance, the researcher may compare groups with and without a certain variable. Research question example: What are the differences in attitudes towards online learning between visual and Kinaesthetic learners? |

| Relationship research questions | These explore and define trends and interactions between two or more variables. These investigate relationships between dependent and independent variables and use words such as “association” or “trends. Research question example: What is the relationship between disposable income and job satisfaction amongst US residents? |

- Qualitative research questions

Qualitative research questions are adaptable, non-directional, and more flexible. It concerns broad areas of research or more specific areas of study to discover, explain, or explore a phenomenon. These are further classified as follows:

| Exploratory Questions | These question looks to understand something without influencing the results. The aim is to learn more about a topic without attributing bias or preconceived notions. Research question example: What are people’s thoughts on the new government? |

| Experiential questions | These questions focus on understanding individuals’ experiences, perspectives, and subjective meanings related to a particular phenomenon. They aim to capture personal experiences and emotions. Research question example: What are the challenges students face during their transition from school to college? |

| Interpretive Questions | These questions investigate people in their natural settings to help understand how a group makes sense of shared experiences of a phenomenon. Research question example: How do you feel about ChatGPT assisting student learning? |

- Mixed-methods studies

Mixed-methods studies use both quantitative and qualitative research questions to answer your research question. Mixed methods provide a complete picture than standalone quantitative or qualitative research, as it integrates the benefits of both methods. Mixed methods research is often used in multidisciplinary settings and complex situational or societal research, especially in the behavioral, health, and social science fields.

What makes a good research question

A good research question should be clear and focused to guide your research. It should synthesize multiple sources to present your unique argument, and should ideally be something that you are interested in. But avoid questions that can be answered in a few factual statements. The following are the main attributes of a good research question.

- Specific: The research question should not be a fishing expedition performed in the hopes that some new information will be found that will benefit the researcher. The central research question should work with your research problem to keep your work focused. If using multiple questions, they should all tie back to the central aim.

- Measurable: The research question must be answerable using quantitative and/or qualitative data or from scholarly sources to develop your research question. If such data is impossible to access, it is better to rethink your question.

- Attainable: Ensure you have enough time and resources to do all research required to answer your question. If it seems you will not be able to gain access to the data you need, consider narrowing down your question to be more specific.

- You have the expertise

- You have the equipment and resources

- Realistic: Developing your research question should be based on initial reading about your topic. It should focus on addressing a problem or gap in the existing knowledge in your field or discipline.

- Based on some sort of rational physics

- Can be done in a reasonable time frame

- Timely: The research question should contribute to an existing and current debate in your field or in society at large. It should produce knowledge that future researchers or practitioners can later build on.

- Novel

- Based on current technologies.

- Important to answer current problems or concerns.

- Lead to new directions.

- Important: Your question should have some aspect of originality. Incremental research is as important as exploring disruptive technologies. For example, you can focus on a specific location or explore a new angle.

- Meaningful whether the answer is “Yes” or “No.” Closed-ended, yes/no questions are too simple to work as good research questions. Such questions do not provide enough scope for robust investigation and discussion. A good research question requires original data, synthesis of multiple sources, and original interpretation and argumentation before providing an answer.

Steps for developing a good research question

The importance of research questions cannot be understated. When drafting a research question, use the following frameworks to guide the components of your question to ease the process. 4

- Determine the requirements: Before constructing a good research question, set your research requirements. What is the purpose? Is it descriptive, comparative, or explorative research? Determining the research aim will help you choose the most appropriate topic and word your question appropriately.

- Select a broad research topic: Identify a broader subject area of interest that requires investigation. Techniques such as brainstorming or concept mapping can help identify relevant connections and themes within a broad research topic. For example, how to learn and help students learn.

- Perform preliminary investigation: Preliminary research is needed to obtain up-to-date and relevant knowledge on your topic. It also helps identify issues currently being discussed from which information gaps can be identified.

- Narrow your focus: Narrow the scope and focus of your research to a specific niche. This involves focusing on gaps in existing knowledge or recent literature or extending or complementing the findings of existing literature. Another approach involves constructing strong research questions that challenge your views or knowledge of the area of study (Example: Is learning consistent with the existing learning theory and research).

- Identify the research problem: Once the research question has been framed, one should evaluate it. This is to realize the importance of the research questions and if there is a need for more revising (Example: How do your beliefs on learning theory and research impact your instructional practices).

How to write a research question

Those struggling to understand how to write a research question, these simple steps can help you simplify the process of writing a research question.

| Topic selection | Choose a broad topic, such as “learner support” or “social media influence” for your study. Select topics of interest to make research more enjoyable and stay motivated. |

| Preliminary research | The goal is to refine and focus your research question. The following strategies can help: Skim various scholarly articles. List subtopics under the main topic. List possible research questions for each subtopic. Consider the scope of research for each of the research questions. Select research questions that are answerable within a specific time and with available resources. If the scope is too large, repeat looking for sub-subtopics. |

| Audience | When choosing what to base your research on, consider your readers. For college papers, the audience is academic. Ask yourself if your audience may be interested in the topic you are thinking about pursuing. Determining your audience can also help refine the importance of your research question and focus on items related to your defined group. |

| Generate potential questions | Ask open-ended “how?” and “why?” questions to find a more specific research question. Gap-spotting to identify research limitations, problematization to challenge assumptions made by others, or using personal experiences to draw on issues in your industry can be used to generate questions. |

| Review brainstormed questions | Evaluate each question to check their effectiveness. Use the FINER model to see if the question meets all the research question criteria. |

| Construct the research question | Multiple frameworks, such as PICOT and PEA, are available to help structure your research question. The frameworks listed below can help you with the necessary information for generating your research question. |

| Framework | Attributes of each framework |

| FINER | Feasible Interesting Novel Ethical Relevant |

| PICOT | Population or problem Intervention or indicator being studied Comparison group Outcome of interest Time frame of the study |

| PEO | Population being studied Exposure to preexisting conditions Outcome of interest |

Sample Research Questions

The following are some bad and good research question examples

- Example 1

| Unclear: How does social media affect student growth? |

| Clear: What effect does the daily use of Twitter and Facebook have on the career development goals of students? |

| Explanation: The first research question is unclear because of the vagueness of “social media” as a concept and the lack of specificity. The second question is specific and focused, and its answer can be discovered through data collection and analysis. |

- Example 2

| Simple: Has there been an increase in the number of gifted children identified? |

| Complex: What practical techniques can teachers use to identify and guide gifted children better? |

| Explanation: A simple “yes” or “no” statement easily answers the first research question. The second research question is more complicated and requires the researcher to collect data, perform in-depth data analysis, and form an argument that leads to further discussion. |

References:

- Thabane, L., Thomas, T., Ye, C., & Paul, J. (2009). Posing the research question: not so simple. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie , 56 (1), 71-79.

- Rutberg, S., & Bouikidis, C. D. (2018). Focusing on the fundamentals: A simplistic differentiation between qualitative and quantitative research. Nephrology Nursing Journal , 45 (2), 209-213.

- Kyngäs, H. (2020). Qualitative research and content analysis. The application of content analysis in nursing science research , 3-11.

- Mattick, K., Johnston, J., & de la Croix, A. (2018). How to… write a good research question. The clinical teacher , 15 (2), 104-108.

- Fandino, W. (2019). Formulating a good research question: Pearls and pitfalls. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia , 63 (8), 611.

- Richardson, W. S., Wilson, M. C., Nishikawa, J., & Hayward, R. S. (1995). The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP journal club , 123 (3), A12-A13

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- Scientific Writing Style Guides Explained

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

- 8 Most Effective Ways to Increase Motivation for Thesis Writing

- 6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

Transitive and Intransitive Verbs in the World of Research

Language and grammar rules for academic writing, you may also like, how to write the first draft of a..., mla works cited page: format, template & examples, academic editing: how to self-edit academic text with..., measuring academic success: definition & strategies for excellence, phd qualifying exam: tips for success , quillbot review: features, pricing, and free alternatives, what is an academic paper types and elements , 9 steps to publish a research paper, what are the different types of research papers, how to make translating academic papers less challenging.

Writing Studio

Formulating your research question (rq).

In an effort to make our handouts more accessible, we have begun converting our PDF handouts to web pages. Download this page as a PDF: Formulating Your Research Question Return to Writing Studio Handouts

In a research paper, the emphasis is on generating a unique question and then synthesizing diverse sources into a coherent essay that supports your argument about the topic. In other words, you integrate information from publications with your own thoughts in order to formulate an argument. Your topic is your starting place: from here, you will develop an engaging research question. Merely presenting a topic in the form of a question does not transform it into a good research question.

Research Topic Versus Research Question Examples

1. broad topic versus narrow question, 1a. broad topic.

“What forces affect race relations in America?”

1b. NARROWER QUESTION

“How do corporate hiring practices affect race relations in Nashville?”

The question “What is the percentage of racial minorities holding management positions in corporate offices in Nashville?” is much too specific and would yield, at best, a statistic that could become part of a larger argument.

2. Neutral Topic Versus Argumentative Question

2a. neutral topic.

“How does KFC market its low-fat food offerings?”

2b. Argumentative question

“Does KFC put more money into marketing its high-fat food offerings than its lower-fat ones?”

The latter question is somewhat better, since it may lead you to take a stance or formulate an argument about consumer awareness or benefit.

3. Objective Topic Versus Subjective Question

Objective subjects are factual and do not have sides to be argued. Subjective subjects are those about which you can take a side.

3a. Objective topic

“How much time do youth between the ages of 10 and 15 spend playing video games?”

3b. Subjective Question

“What are the effects of video-gaming on the attention spans of youth between the ages of 10 and 15?”

The first question is likely to lead to some data, though not necessarily to an argument or issue. The second question is somewhat better, since it might lead you to formulate an argument for or against time spent playing video games.

4. Open-Ended Topic Versus Direct Question

4a. open-ended topic.

“Does the author of this text use allusion?”

4b. Direct question (gives direction to research)

“Does the ironic use of allusion in this text reveal anything about the author’s unwillingness to divulge his political commitments?”

The second question gives focus by putting the use of allusion into the specific context of a question about the author’s political commitments and perhaps also about the circumstances under which the text was produced.

Research Question (RQ) Checklist

- Is my RQ something that I am curious about and that others might care about? Does it present an issue on which I can take a stand?

- Does my RQ put a new spin on an old issue, or does it try to solve a problem?

- Is my RQ too broad, too narrow, or OK?

- within the time frame of the assignment?

- given the resources available at my location?

- Is my RQ measurable? What type of information do I need? Can I find actual data to support or contradict a position?

- What sources will have the type of information that I need to answer my RQ (journals, books, internet resources, government documents, interviews with people)?

Final Thoughts

The answer to a good research question will often be the THESIS of your research paper! And the results of your research may not always be what you expected them to be. Not only is this ok, it can be an indication that you are doing careful work!

Adapted from an online tutorial at Empire State College: http://www.esc.edu/htmlpages/writerold/menus.htm#develop (broken link)

Last revised: November 2022 | Adapted for web delivery: November 2022

In order to access certain content on this page, you may need to download Adobe Acrobat Reader or an equivalent PDF viewer software.

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write a Good Research Question (w/ Examples)

What is a Research Question?

A research question is the main question that your study sought or is seeking to answer. A clear research question guides your research paper or thesis and states exactly what you want to find out, giving your work a focus and objective. Learning how to write a hypothesis or research question is the start to composing any thesis, dissertation, or research paper. It is also one of the most important sections of a research proposal .

A good research question not only clarifies the writing in your study; it provides your readers with a clear focus and facilitates their understanding of your research topic, as well as outlining your study’s objectives. Before drafting the paper and receiving research paper editing (and usually before performing your study), you should write a concise statement of what this study intends to accomplish or reveal.

Research Question Writing Tips

Listed below are the important characteristics of a good research question:

A good research question should:

- Be clear and provide specific information so readers can easily understand the purpose.

- Be focused in its scope and narrow enough to be addressed in the space allowed by your paper

- Be relevant and concise and express your main ideas in as few words as possible, like a hypothesis.

- Be precise and complex enough that it does not simply answer a closed “yes or no” question, but requires an analysis of arguments and literature prior to its being considered acceptable.

- Be arguable or testable so that answers to the research question are open to scrutiny and specific questions and counterarguments.

Some of these characteristics might be difficult to understand in the form of a list. Let’s go into more detail about what a research question must do and look at some examples of research questions.

The research question should be specific and focused

Research questions that are too broad are not suitable to be addressed in a single study. One reason for this can be if there are many factors or variables to consider. In addition, a sample data set that is too large or an experimental timeline that is too long may suggest that the research question is not focused enough.

A specific research question means that the collective data and observations come together to either confirm or deny the chosen hypothesis in a clear manner. If a research question is too vague, then the data might end up creating an alternate research problem or hypothesis that you haven’t addressed in your Introduction section .

| What is the importance of genetic research in the medical field? | |

| How might the discovery of a genetic basis for alcoholism impact triage processes in medical facilities? |

The research question should be based on the literature

An effective research question should be answerable and verifiable based on prior research because an effective scientific study must be placed in the context of a wider academic consensus. This means that conspiracy or fringe theories are not good research paper topics.

Instead, a good research question must extend, examine, and verify the context of your research field. It should fit naturally within the literature and be searchable by other research authors.

References to the literature can be in different citation styles and must be properly formatted according to the guidelines set forth by the publishing journal, university, or academic institution. This includes in-text citations as well as the Reference section .

The research question should be realistic in time, scope, and budget

There are two main constraints to the research process: timeframe and budget.

A proper research question will include study or experimental procedures that can be executed within a feasible time frame, typically by a graduate doctoral or master’s student or lab technician. Research that requires future technology, expensive resources, or follow-up procedures is problematic.

A researcher’s budget is also a major constraint to performing timely research. Research at many large universities or institutions is publicly funded and is thus accountable to funding restrictions.

The research question should be in-depth

Research papers, dissertations and theses , and academic journal articles are usually dozens if not hundreds of pages in length.

A good research question or thesis statement must be sufficiently complex to warrant such a length, as it must stand up to the scrutiny of peer review and be reproducible by other scientists and researchers.

Research Question Types

Qualitative and quantitative research are the two major types of research, and it is essential to develop research questions for each type of study.

Quantitative Research Questions

Quantitative research questions are specific. A typical research question involves the population to be studied, dependent and independent variables, and the research design.

In addition, quantitative research questions connect the research question and the research design. In addition, it is not possible to answer these questions definitively with a “yes” or “no” response. For example, scientific fields such as biology, physics, and chemistry often deal with “states,” in which different quantities, amounts, or velocities drastically alter the relevance of the research.

As a consequence, quantitative research questions do not contain qualitative, categorical, or ordinal qualifiers such as “is,” “are,” “does,” or “does not.”

Categories of quantitative research questions

| Attempt to describe the behavior of a population in regard to one or more variables or describe characteristics of those variables that will be measured. These are usually “What?” questions. | Seek to discover differences between groups within the context of an outcome variable. These questions can be causal as well. Researchers may compare groups in which certain variables are present with groups in which they are not. | Designed to elucidate and describe trends and interactions among variables. These questions include the dependent and independent variables and use words such as “association” or “trends.” |

Qualitative Research Questions

In quantitative research, research questions have the potential to relate to broad research areas as well as more specific areas of study. Qualitative research questions are less directional, more flexible, and adaptable compared with their quantitative counterparts. Thus, studies based on these questions tend to focus on “discovering,” “explaining,” “elucidating,” and “exploring.”

Categories of qualitative research questions

| Attempt to identify and describe existing conditions. | Attempt to describe a phenomenon. | Assess the effectiveness of existing methods, protocols, theories, or procedures. |

| Examine a phenomenon or analyze the reasons or relationships between subjects or phenomena. | Focus on the unknown aspects of a particular topic. |

Quantitative and Qualitative Research Question Examples

| Descriptive research question | |

| Comparative research question | |

| Correlational research question | |

| Exploratory research question | |

| Explanatory research question | |

| Evaluation research question |

Good and Bad Research Question Examples

Below are some good (and not-so-good) examples of research questions that researchers can use to guide them in crafting their own research questions.

Research Question Example 1

The first research question is too vague in both its independent and dependent variables. There is no specific information on what “exposure” means. Does this refer to comments, likes, engagement, or just how much time is spent on the social media platform?

Second, there is no useful information on what exactly “affected” means. Does the subject’s behavior change in some measurable way? Or does this term refer to another factor such as the user’s emotions?

Research Question Example 2

In this research question, the first example is too simple and not sufficiently complex, making it difficult to assess whether the study answered the question. The author could really only answer this question with a simple “yes” or “no.” Further, the presence of data would not help answer this question more deeply, which is a sure sign of a poorly constructed research topic.

The second research question is specific, complex, and empirically verifiable. One can measure program effectiveness based on metrics such as attendance or grades. Further, “bullying” is made into an empirical, quantitative measurement in the form of recorded disciplinary actions.

Steps for Writing a Research Question

Good research questions are relevant, focused, and meaningful. It can be difficult to come up with a good research question, but there are a few steps you can follow to make it a bit easier.

1. Start with an interesting and relevant topic

Choose a research topic that is interesting but also relevant and aligned with your own country’s culture or your university’s capabilities. Popular academic topics include healthcare and medical-related research. However, if you are attending an engineering school or humanities program, you should obviously choose a research question that pertains to your specific study and major.

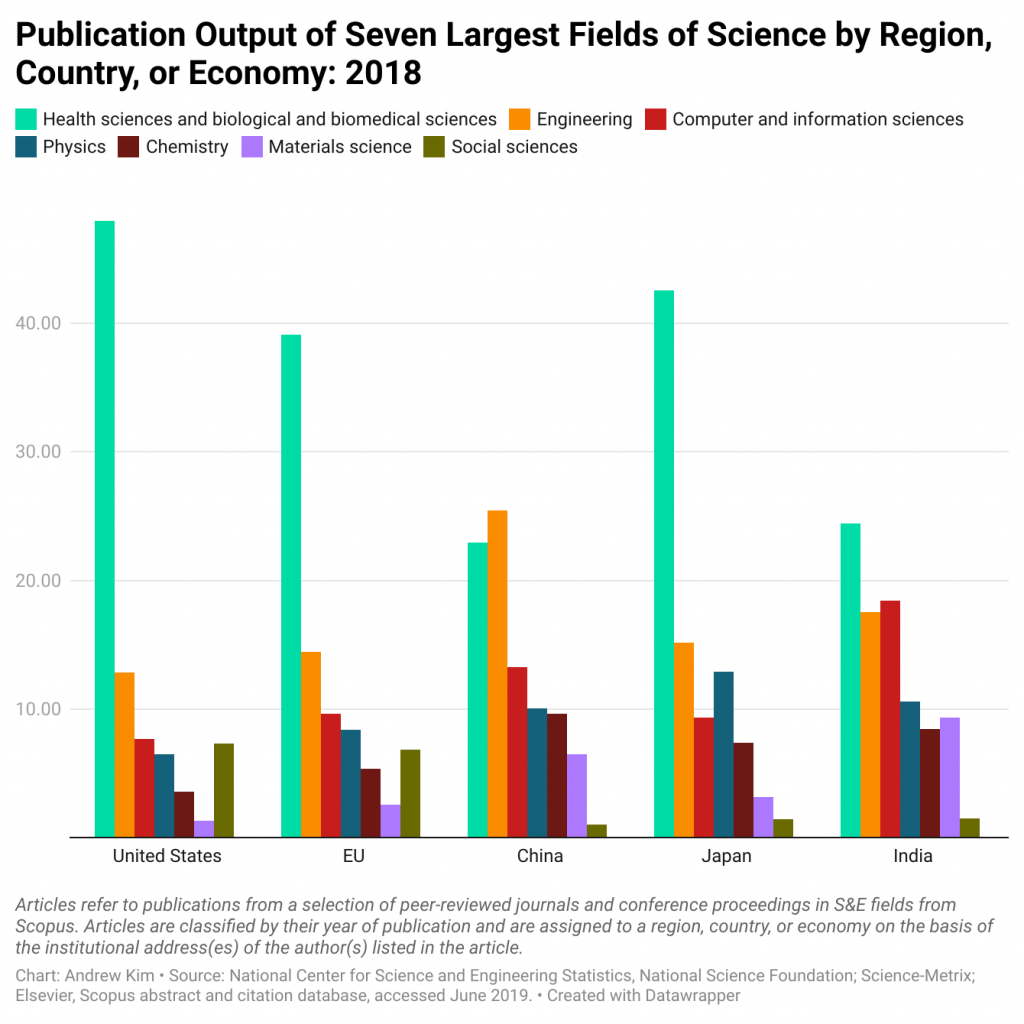

Below is an embedded graph of the most popular research fields of study based on publication output according to region. As you can see, healthcare and the basic sciences receive the most funding and earn the highest number of publications.

2. Do preliminary research

You can begin doing preliminary research once you have chosen a research topic. Two objectives should be accomplished during this first phase of research. First, you should undertake a preliminary review of related literature to discover issues that scholars and peers are currently discussing. With this method, you show that you are informed about the latest developments in the field.

Secondly, identify knowledge gaps or limitations in your topic by conducting a preliminary literature review . It is possible to later use these gaps to focus your research question after a certain amount of fine-tuning.

3. Narrow your research to determine specific research questions

You can focus on a more specific area of study once you have a good handle on the topic you want to explore. Focusing on recent literature or knowledge gaps is one good option.

By identifying study limitations in the literature and overlooked areas of study, an author can carve out a good research question. The same is true for choosing research questions that extend or complement existing literature.

4. Evaluate your research question

Make sure you evaluate the research question by asking the following questions:

Is my research question clear?

The resulting data and observations that your study produces should be clear. For quantitative studies, data must be empirical and measurable. For qualitative, the observations should be clearly delineable across categories.

Is my research question focused and specific?

A strong research question should be specific enough that your methodology or testing procedure produces an objective result, not one left to subjective interpretation. Open-ended research questions or those relating to general topics can create ambiguous connections between the results and the aims of the study.

Is my research question sufficiently complex?

The result of your research should be consequential and substantial (and fall sufficiently within the context of your field) to warrant an academic study. Simply reinforcing or supporting a scientific consensus is superfluous and will likely not be well received by most journal editors.

Editing Your Research Question

Your research question should be fully formulated well before you begin drafting your research paper. However, you can receive English paper editing and proofreading services at any point in the drafting process. Language editors with expertise in your academic field can assist you with the content and language in your Introduction section or other manuscript sections. And if you need further assistance or information regarding paper compositions, in the meantime, check out our academic resources , which provide dozens of articles and videos on a variety of academic writing and publication topics.

How to Develop a Good Research Question? — Types & Examples

Cecilia is living through a tough situation in her research life. Figuring out where to begin, how to start her research study, and how to pose the right question for her research quest, is driving her insane. Well, questions, if not asked correctly, have a tendency to spiral us!

Image Source: https://phdcomics.com/

Questions lead everyone to answers. Research is a quest to find answers. Not the vague questions that Cecilia means to answer, but definitely more focused questions that define your research. Therefore, asking appropriate question becomes an important matter of discussion.

A well begun research process requires a strong research question. It directs the research investigation and provides a clear goal to focus on. Understanding the characteristics of comprising a good research question will generate new ideas and help you discover new methods in research.

In this article, we are aiming to help researchers understand what is a research question and how to write one with examples.

Table of Contents

What Is a Research Question?

A good research question defines your study and helps you seek an answer to your research. Moreover, a clear research question guides the research paper or thesis to define exactly what you want to find out, giving your work its objective. Learning to write a research question is the beginning to any thesis, dissertation , or research paper. Furthermore, the question addresses issues or problems which is answered through analysis and interpretation of data.

Why Is a Research Question Important?

A strong research question guides the design of a study. Moreover, it helps determine the type of research and identify specific objectives. Research questions state the specific issue you are addressing and focus on outcomes of the research for individuals to learn. Therefore, it helps break up the study into easy steps to complete the objectives and answer the initial question.

Types of Research Questions

Research questions can be categorized into different types, depending on the type of research you want to undergo. Furthermore, knowing the type of research will help a researcher determine the best type of research question to use.

1. Qualitative Research Question

Qualitative questions concern broad areas or more specific areas of research. However, unlike quantitative questions, qualitative research questions are adaptable, non-directional and more flexible. Qualitative research question focus on discovering, explaining, elucidating, and exploring.

i. Exploratory Questions

This form of question looks to understand something without influencing the results. The objective of exploratory questions is to learn more about a topic without attributing bias or preconceived notions to it.