Homeless to Housed Research Report: The ULI Perspective Based on Actual Case Studies

Report Summary: This report explores the role the real estate community can play in addressing the issue of homelessness. It includes a summary of lessons learned, a blueprint for how to replicate best practices in U.S. communities, and a series of case studies that demonstrate how the development community can be an active partner in […]

One Museum Place

One Museum Place is a 1.4 million-square-foot, 60-story prime office tower with a six-story retail podium in Shanghai. Located next to the Natural History Museum and Jing’an Sculpture Park, One Museum Place is a Gensler-designed addition to the Jing’an skyline. The six-level, 228,378-square-foot (93,786 NRA) lifestyle-oriented retail podium features a variety of food and beverage […]

ULI Greenprint Annual Performance Report Vol 9 – LaSalle’s Holistic Energy Retrofits

LaSalle Investments’ 2020 K Street in Washington, D.C., is an 11-story multitenant structure built in 1974 with a fitness center, parking garage, and rooftop terrace. Since acquisition in 2010, LaSalle has been continually upgrading the building to achieve a holistic retrofit as part of its investment strategy. Initiatives include the following: variable frequency drives (VFDs) […]

Nature Positive and Net Zero – Green Cities Company and Salmon Safe Certification

The Green Cities Company is a real estate investor and developer that pursues green certifications for each asset in its portfolio. At 5 MLK, a 17-story mixed-use building with 220 apartment units, 120,000 square feet of office space, and 15,000 square feet of retail space in Portland, Oregon, a Salmon Safe certification label was achieved […]

Electrify — 30 Van Ness, San Francisco, California (Lendlease)

Lendlease’s 30 Van Ness is its first all-electric mixed-used development in the United States, and the decision to be all electric was made long before San Francisco passed a citywide no-gas policy for new construction. With 250,000 square feet of commercial office space, 330 condominiums (of which 25 percent will be affordable housing), 4,000 square […]

ULI Greenprint Annual Performance Report Vol 10 – Net-Zero Energy: Morgan Creek Ventures

As more cities enact clean energy plans and pass mandatory benchmarking ordinances, building owners and investors across the country are increasingly looking toward net-zero energy (NZE) as their next goal to continue reducing carbon emissions in the built environment.

New Genesis Apartments

New Genesis Apartments is a 106-unit, mixed-income, mixed-use housing redevelopment project that includes local retailers, affordable artists’ lofts, and supportive housing services. The project is located between downtown Los Angeles’s burgeoning historic core and the city’s Skid Row neighborhood, a 50-block area that is home to more than 4,600 people who lack permanent stable housing.

Block E is a large-scale, urban mixed-use project that combines retail, entertainment, hospitality, and parking uses. Located in downtown Minneapolis, it derives its name from the city block upon which it is built. The urban entertainment complex has little competition in the downtown and is rapidly becoming a key destination there. It contains a mix of stores, nightclubs, restaurants, and entertainment venues intended to appeal to people of all ages. Restaurants, bars, and stores fill the project’s first and second stories, while a 15-screen, 4,000-seat multiplex cinema is found on the third floor. A 255-room hotel occupies the fourth through 21st floors.

The Belmont Dairy

A 141,000-square-foot, transit-oriented mixed-use building on two city blocks in southeast Portland, Oregon. The mixed-income project is built on the former site of a dairy built in 1929. Today, the development features 85 apartments built atop street-level retail stores Including a restaurant, a hair salon, and a 20,000-square-foot grocery. The project was constructed as a “green” development and incorporates recycled materials, water-saving shower heads, extra insulation, and skylights. In addition, more than 90 percent of the construction debris on the site was recycled.

Southborough

Located in Charlotte, North Carolina, Southborough is a mixed-use project with 69 residential units and a 30,280-square-foot (2,813-sq-m) commercial building that “wrap” an even larger Lowe’s home improvement store. Developed by the locally based Conformity Corporation, Southborough provides an example of how the construction of a large-format retail store in an existing neighborhood can be mitigated through a high-quality housing and commercial development that act as a buffer and enhance the urban fabric.

Sign in with your ULI account to get started

Don’t have an account? Sign up for a ULI guest account.

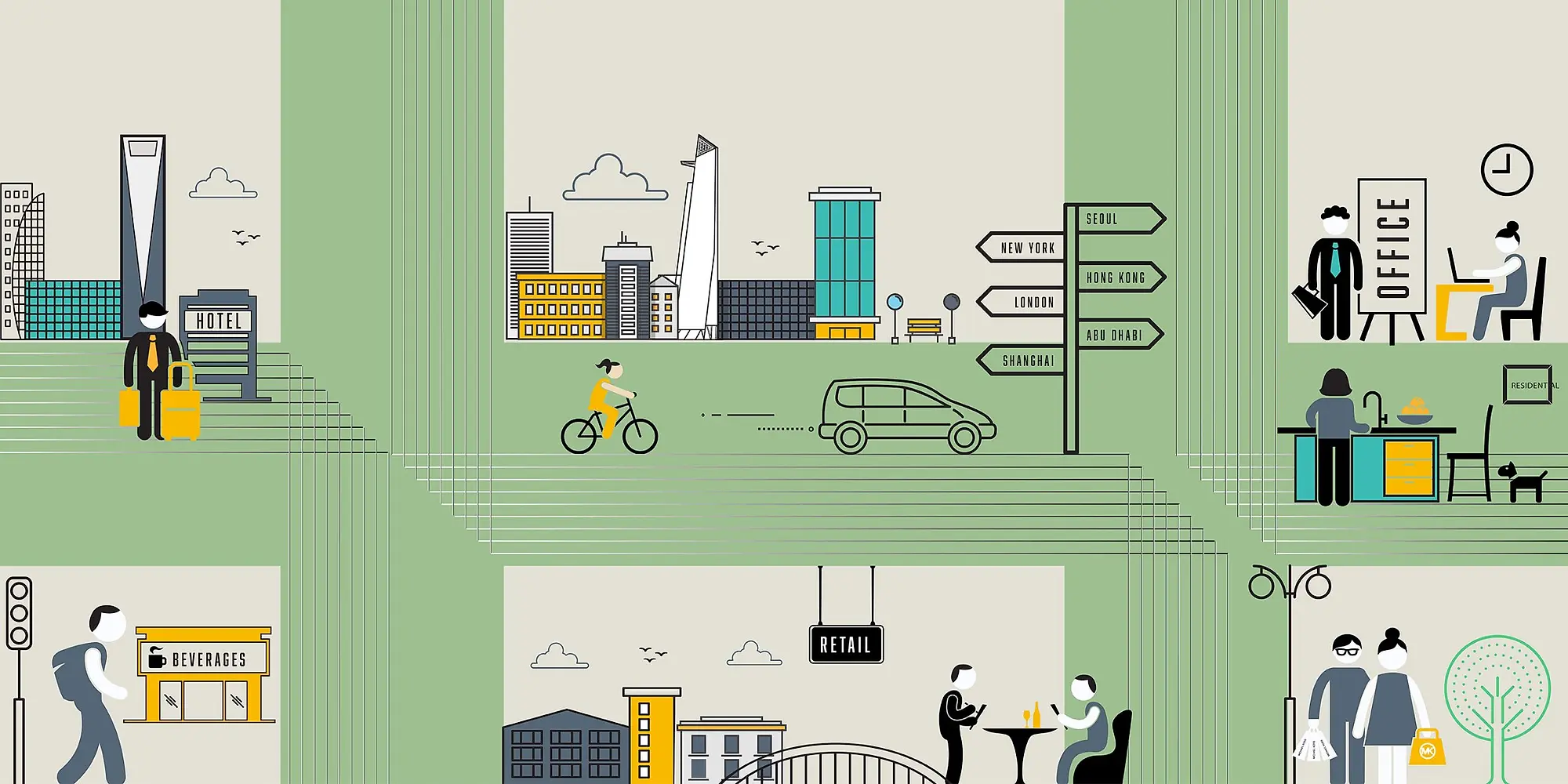

Under One Roof: The Evolution of the Mixed-Use Building

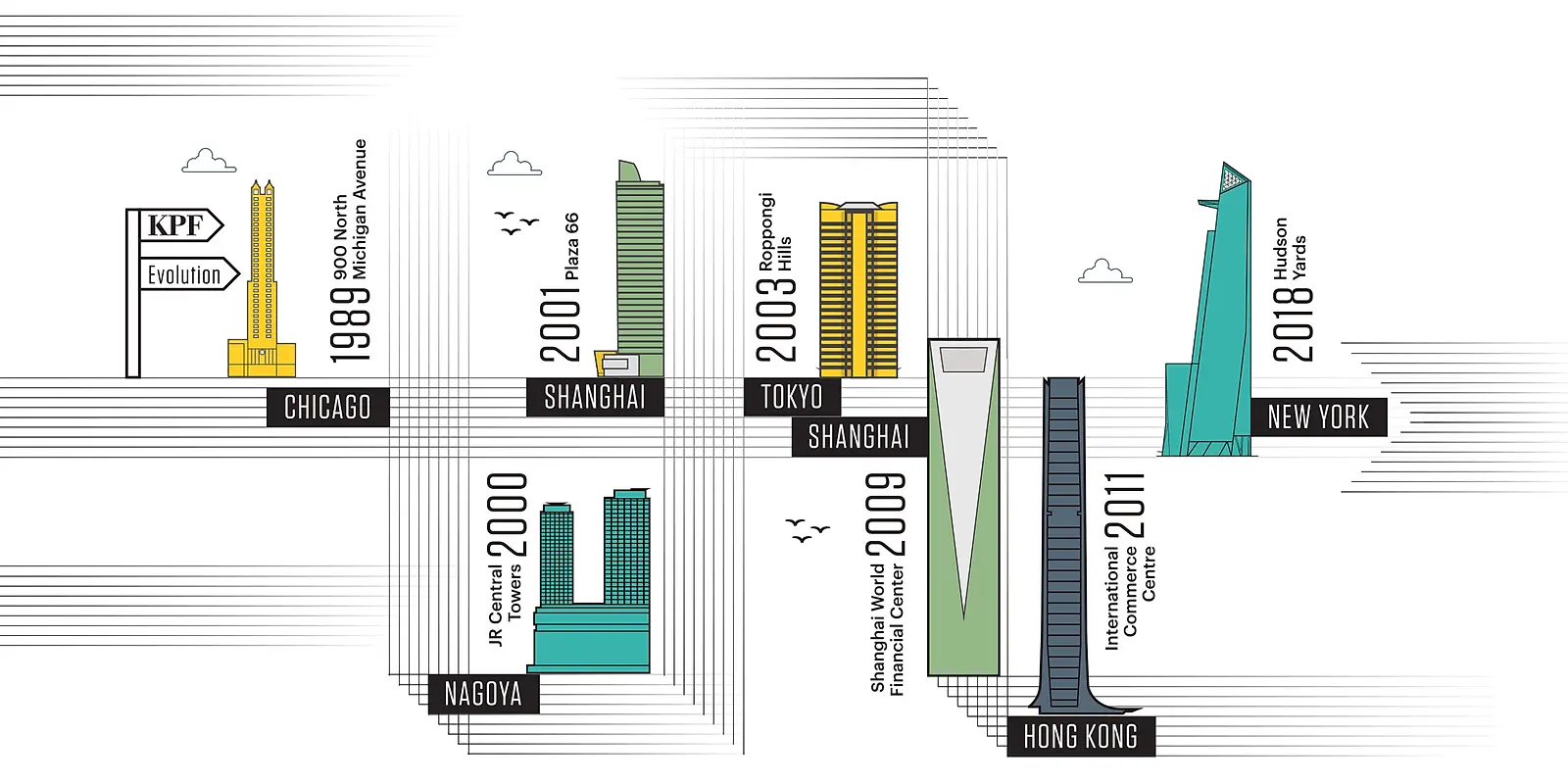

Compounded by global issues such as resource scarcity, the migration to cities is placing great responsibility on urban buildings to do many things, and do them well. Mixed-use development, the physically integrated combination of residential, commercial, cultural, and transportation functions, consolidates activity within a structure or neighborhood. In our densifying cities, the adoption and thoughtful execution of mixed-use development is a necessity.

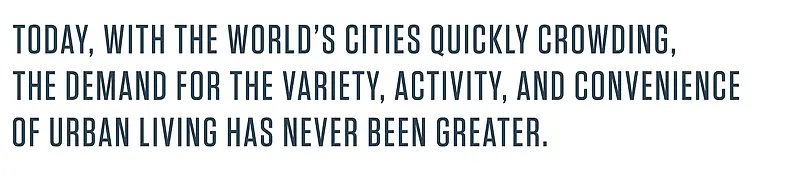

The mixed-use typology is not new; one of the first examples is Trajan’s Market (110 AD) of ancient Rome with both shops and apartments built in a multi-level structure. Historians believe that the building’s arcades were administrative offices of Emperor Trajan, and the remains of a library have been excavated. The rise of the automobile and telecommunication technologies in the 20th Century, meant dispersion. Sprawl prevailed. However, as the population has increasingly migrated into cities over the past thirty years, the mixed-use building has experienced a period of great experimentation and rebirth. At each period, KPF has been a major contributor to the evolution of the mixed-use building type.

The completion of KPF’s 1989 900 North Michigan Avenue was one of the first buildings on Magnificent Mile with a vertical, varied program. The building combines five major uses: a shopping mall with Bloomingdales as an anchor tenant; a Four Seasons Hotel; office space in the tower’s lower section; condominiums on the higher floors; and one of the city’s largest parking garages. With four ‘lanterns’ forming a crown at 260 meters, the tower punctuates Chicago’s skyline with a sophisticated, unified expression. 900 North Michigan was the first of its kind for KPF, and remains the 8th tallest building in the city today.

The value of each floor benefitted from the common desire among tenants and residents alike for a streetfront that invited the city in. It offered proof to the development industry that different uses, like architectural elements themselves, could be brought together to form a new kind of synergy, with a combined effect greater than the sum of its parts.

From 900 North Michigan’s success, KPF was commissioned to design the Japan Rail Central Towers and Station , completed in 2000 in Nagoya, Japan that includes 1.1 million square feet of office space, a 700 + room hotel, 10 restaurants, and a 50,000-square-foot convention center. What made the JR Central Towers extraordinary was the fact that they were built over the largest train station in the world, Nagoya station. The station comprises two national and two private railway lines, four subway lines, Japan Rail and city bus lines, as well as the bullet train Tokaido Shinkansen. This project physically connects the subterranean to sweeping views of the city of Nagoya, with places to work, eat, sleep, and meet in between. It took the commercial synergies of 900 North Michigan and merged them seamlessly with an entire nation’s transportation infrastructure. The project was not only pioneer for vertical living, with public spaces and sky streets to located 10 and 15 stories in the air, but its link to public transportation makes it one of the first and most-successful transit-oriented developments.

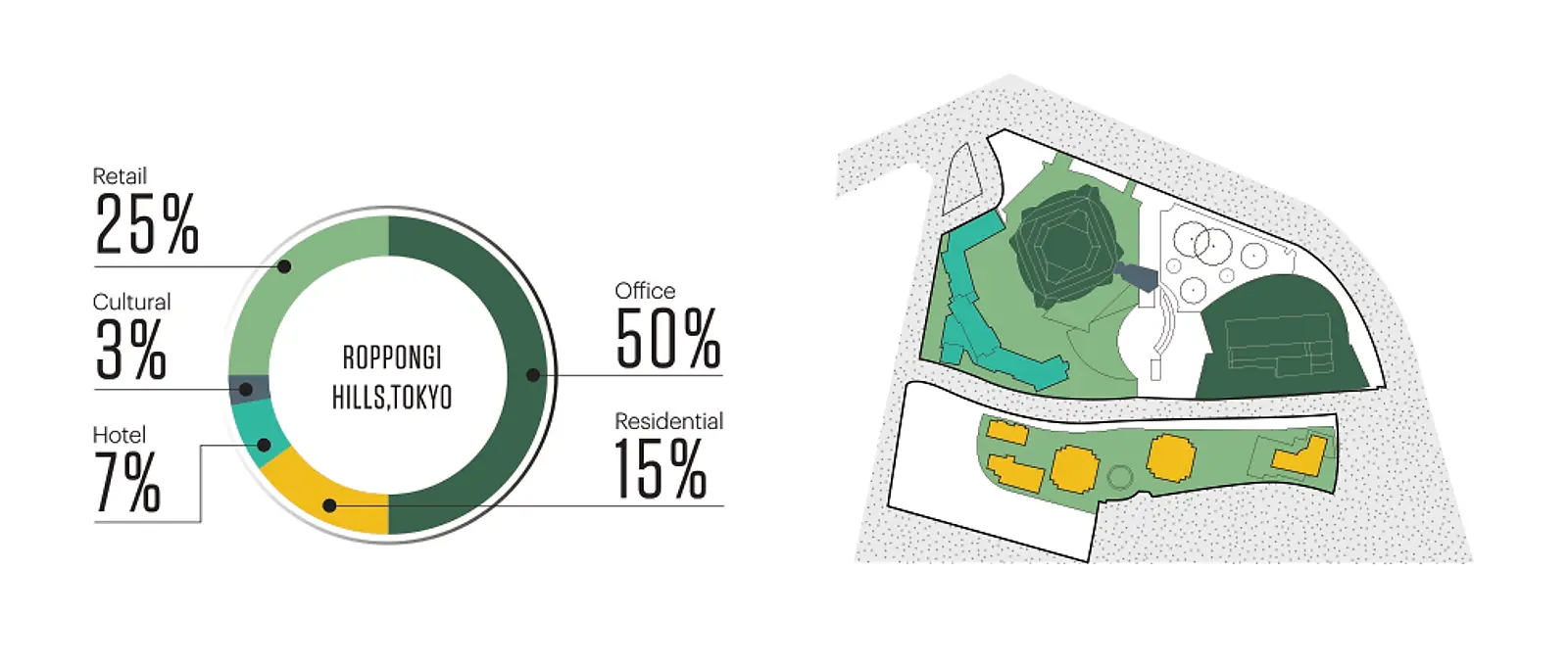

In the 2000s, KPF designed some of the most frequently cited mixed-use projects, including Roppongi Hills , completed 2003 in Tokyo, which remains the largest private-sector urban redevelopment in Japan’s history. Several projects in China followed, such as Plaza 66 of 2001, a premier shopping and office address in Shanghai. In Hong Kong, Landmark , also completed in 2006, included the renovation and extension of a retail development, and addition of a boutique hotel; the International Commerce Centre was completed in 2010, with offices, the world’s highest hotel, and a new transportation hub beneath; and Hysan Place followed in 2012 with 32 floors of offices and retail outlets, and a direct link to the Causeway Bay Station.

It was during this period that the Shanghai World Financial Center , the tallest tower in Shanghai and second tallest in the world upon its completion, was completed in 2008. The 380,000 gross-square-meter structure tower houses a mix of office and retail uses, and the Park Hyatt Shanghai. The form, two arcing curves that gesture to the sky with a trapezoidal aperture at the 97th floor, offers a graceful moment of serenity amidst the frenetic environment of Pudong, Shanghai’s Central Business District. At the supertall scale, the responsibility of the architect extends beyond the boundaries of building envelope and project site. Similar to 900 North Michigan, the mixed-use typology took a visual and important place in the skyline. It became an instant symbol of the culture and commerce of the city.

While the firm has continued to design high-rise buildings and supertalls, KPF’s formula for the pronounced vertical stacked tower influenced the firm’s work at the neighborhood level. How can the density of a skyscraper work within a communal town square? This answer is scale. An example is the Jing An Kerry Centre in Shanghai, the multi-use complex features two towers, podium retail, a 508-key hotel, an event center and office amenities arranged around the preserved house where Mao Zedong lived. Fusing the neighborhood’s historic character with modern Shanghai, Jing An Kerry Centre combines high density living with of the city street experience. Open-air walkways lined with shops welcome pedestrian activity. Careful integration on the ground level using architectural elements in proportion to the human body – lighting, colors, and materials – connect the soaring towers to the street. Meanwhile, the tall buildings visually mend the skyline by connecting two existing office clusters in the city.

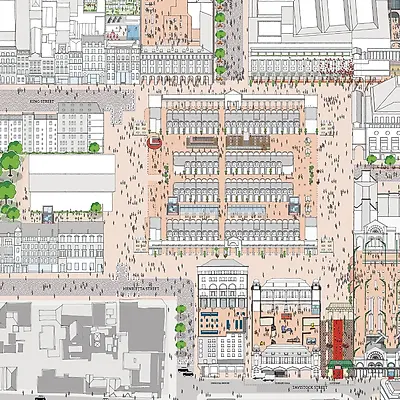

The expertise gained in the creation of one mixed-use neighborhood led to the improvement of another. Covent Garden , with its first existing master plan dating back to 1609, is a renowned district with a culturally and architecturally rich history. In Covent Garden in London, this kind of mixed-use thinking was extended to fine-tune elements for the overall improvement of the neighborhood. Plagued by congestion, run-down facilities, and intensive tourism, Covent Garden had become an avoidable destination for Londoners. KPF’s expertise in mixed-use environments allowed the firm to believe in this historic section of London as a single functioning entity that could sponsor a great diversity of experience. Three major actions are proposed in the master plan: public realm improvements, conservation and re-positioning of the heritage assets, and the replacement of non-contributing outdated buildings with new architecture.

The projects of the early 2000s represented a new approach to mixed-use design that coalesced at the scale of a building, but also at the scale of entire districts. The integration of cultural spaces, public parks, walkable shopping and entertainment areas, and seamless transit connections enriched the urban fabric in their cities. These districts attracted many visitors and lured blue-chip tenants to lease tower floors in order to secure a place at the most vibrant addresses in their cities. The cultural and financial success of the golden age of mixed-use development in Asia attracted the attention of ambitious developers in Europe and in the United States. KPF and many of our peers have since been commissioned for projects in these regions.

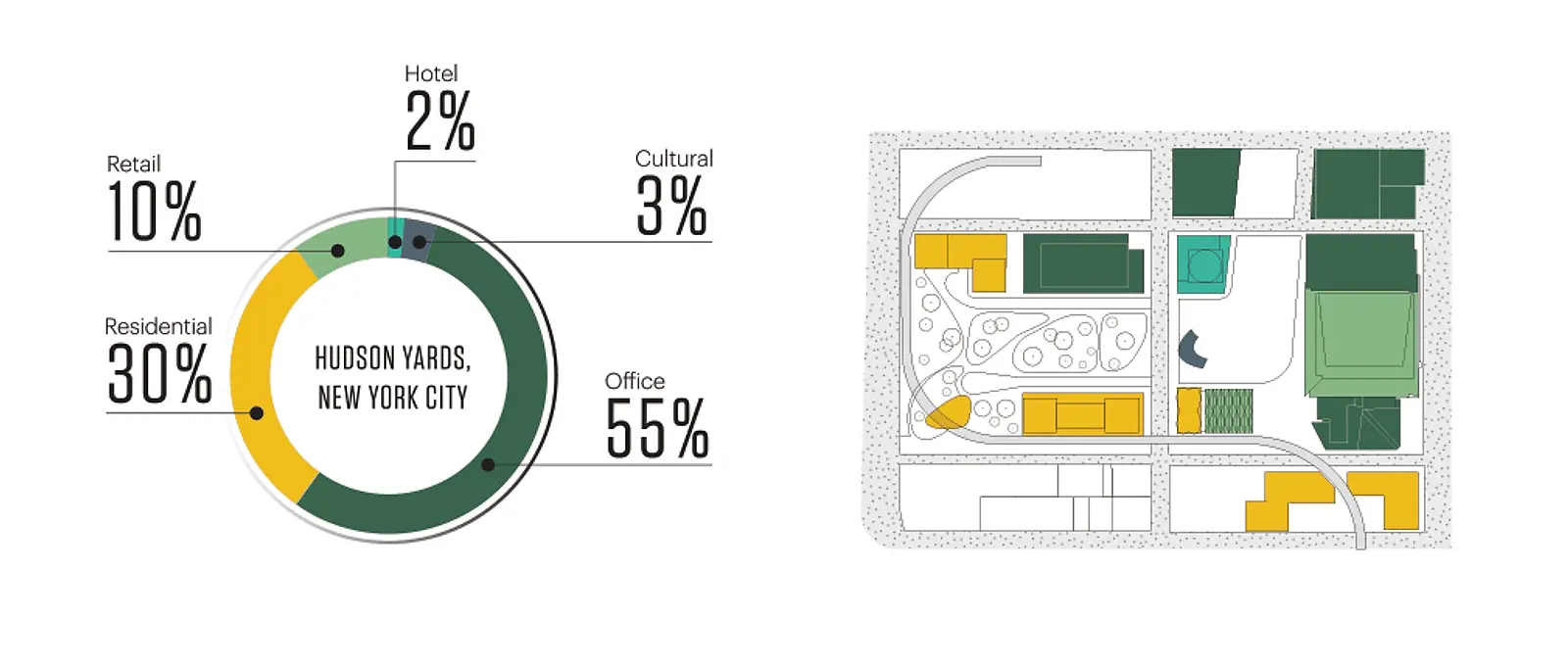

The largest private real estate development in the history of the United States, the first phase of Hudson Yards covered 11,340,000 square feet of construction. Drawing on the experience gained over 20 years in complex, mixed-use construction, KPF led the design of the development. Hudson Yards’ defining characteristic is the humanistic design approach to seamlessly blending infrastructure with architectural designs. To complete Related’s ambitious master plan, two platforms bridge 30 active Long Island Rail Road train tracks. Two towers , at 52 stories and 90 stories respectively, completed construction atop the rail yards. The buildings extend through the platform and rise above, with caissons drilled deep into the bedrock between rail lines to support the structures. The combination of the public and private interests, transportation, retail, commerce, residences, and education makes Hudson Yards the most complex mixed-use project in New York since Rockefeller Center.

The popularity of the mixed-use typology has traveled where it is needed. In Chicago, 900 North Michigan set a precedent from which Magnificent Mile grew. In Japan, Roppongi Hills and JR Central towers provided transportation infrastructure and tight-knit urban communities in the country’s most populous cities. Spreading to China, projects like the Shanghai World Financial Center and International Commerce Centre, implemented much-needed vertical density and cultural symbolism in Shanghai and Hong Kong. Now, in New York and throughout the USA, development is benefitting from KPF’s global experience in mixed-use architecture. As cities continue to grow, the mixed-use building will serve as an important tool to densify in a humanizing manner and will be critical to the success of the city in the future.

Related Content

District Architecture

Covent Garden

KPF Presents: The Sustainable Future

Towards an Urban Troposphere

An interdisciplinary debate on project perspectives

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 14 October 2022

Extremes of mixed-use architecture: a spatial analysis of vertical functional mix in Dhaka

- Fatema Meher Khan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4761-7836 1 ,

- Elek Pafka 2 &

- Kim Dovey 2

City, Territory and Architecture volume 9 , Article number: 31 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

8598 Accesses

Metrics details

The concept of mixed-use is now well-established as an urban design and planning principle that adds to the vitality, walkability and productivity of the city at neighbourhood scale. There is much less research on the dense and complex vertical mix of functions within buildings. This paper investigates the extremes of informal vertical mixing of functions within buildings in Dhaka, where commercial and retail functions often penetrate to upper floors and where access routes are often mixed with residential functions. A modified form of space syntax analysis is used to analyse and critique the mix of circulation patterns and functions in 15 complex mixed-use buildings. The plans and relational diagrams reveal how different functions are mixed or separated, and the relative spatial depth they penetrate from the street. Five primary circulation diagrams emerge with different degrees of informality in different districts of the city. Under conditions of informal adaptation, vertical functional mix produces benefits in the form of synergies but also problems of privacy and security. To engage effectively planners need a complex understanding of the interrelated spatial, social and economic logics involved.

Introduction

It is now sixty years since Jacobs ( 1961 ) transformed our conceptions of functional mix, suggesting that an understanding of co-functioning was a key to understanding how cities work. She railed against the modernist segregation of the city into mono-functional zones that prevented close connections of home to work, school, shopping and recreation. Functional mix was the antithesis of modernist development that stressed the spatial segregation of urban functions to avoid an undesirable juxtaposition of uses. For Jacobs mixed-use was necessary to the social and economic vitality and intensity of the city; this work has been increasingly embraced in urban planning and functional mix has become a key ingredient of walkability (Grant 2002 ; Hoppenbrouwer and Louw 2005 ; Rabianski et al. 2009 ; Frank et al. 2006 ; Dovey and Pafka 2020 ). While most of this research has focused on the neighbourhood scale, it has been understood that functional mix also operates at the building scale. Most notable here is the widespread historic type of shop-house with residential located above retail functions; this building type has long been a staple in South and Southeast Asian cities (Davis 2012 ; Han and Beisi 2016 ).

Modernist zoning was invented to solve real problems that can emerge from an unregulated mix of uses. In 2010 and again in 2019 fires have broken out in mixed-use buildings in Old Dhaka, killing a total of 205 people (Imam 2010 ; Molla 2019 ). Both fires involved flammable industrial materials stored on lower floors with housing and production work above. These fires were variously blamed on electrical transformers, gas cylinders, chemical storage, building regulators and owners, but also on a more general lack of urban planning controls (Tishi and Islam 2019 ). In Dhaka, functional mix is widely considered problematic; beyond issues of fire safety, there are perceived problems of visual disorder, privacy and social insecurity (Tishi and Islam 2019 ; Nahrin 2008 ). This paper analyses a range of mixed-use buildings in Dhaka to better understand the morphologies of informal mix.

While there is considerable scholarly work on the shop-houses of South and Southeast Asia (Imamuddin et al. 1989 ; Chun et al. 2005 ; Phuong and Groves 2010 ; Su-Jan et al. 2012 ; Davis 2012 ) the buildings under discussion here encompass a much denser range of building types. No survey or analysis has been conducted to understand the operation of dense informally mixed buildings such as these. This study explores four principal questions: How are different functions mixed and/or separated within circulation systems of mixed-use buildings? To what relative spatial depth do different functions penetrate from public space and to what height above street level? How are buildings adapted informally to multiple uses and what are the synergies and challenges of such mixing? This paper analyses the functional mix of some of the most extreme of vertically mixed buildings in Dhaka—those that test the limits of functional mixing. These analyses reveal typical circulation patterns and the spatial logic of interrelations between functions, based in the economic and social logic of the city. The paper concludes with a critique of the benefits and challenges of vertical functional mix.

Mixed-use buildings are common in cities of the global South, particularly South and Southeast Asia. The prevalence of functional mix has been noted in Indonesia (Susantono 1998 ), India (Verma 1993 ), Vietnam (Phuong and Groves 2010 ) and Pakistan (Haque 2015 , p. 7) where they generally feature high-levels of informal or unregulated mix. More contemporary mixed-use buildings demonstrate new forms of mix, spatial organisation and building morphology in high-density buildings with vertical stacking of wholesale, retail, restaurants, offices, storage, micro-industries and housing (Ujang and Shamsuddin 2008 ; Tipple et al. 1996 ).

While Dhaka was always mixed, as the urban density has intensified the mixed-use buildings have grown informally in both extent and functional complexity to meet local demand. Incremental conversion of residential buildings to accommodate workshops, storage, commercial and retail functions are common (Khan 2020 , 2021 ). Access routes into and through mixed-use buildings are adapted where it is possible to separate entrance and circulation for separate uses. However, a singular entrance for residential and non-residential functions is common and can result in privacy, security and safety issues.

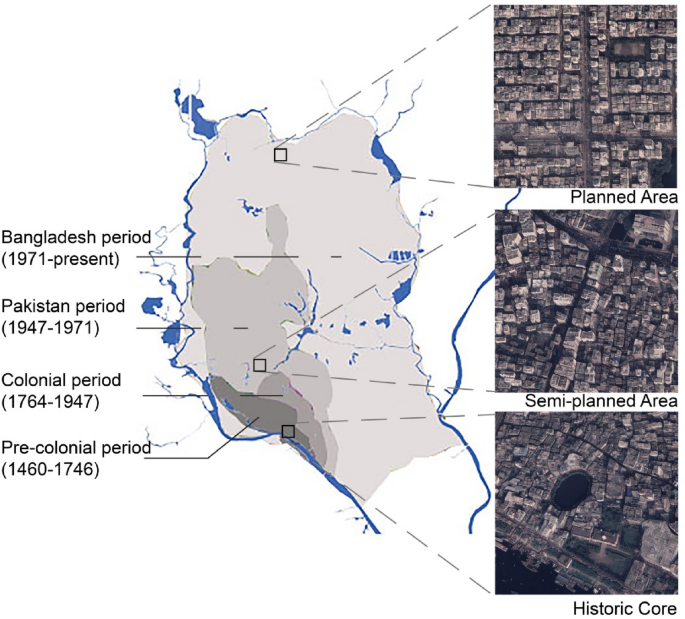

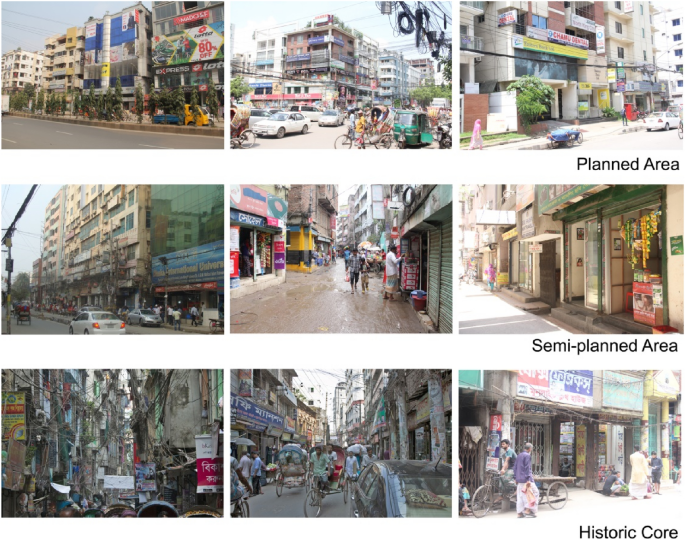

Study area and methodology

Dhaka is dominated by informal economic activities and the current land-use of most districts is shown in planning documents as mixed-use (Rajdhani Unnayan Kartripakkha [RAJUK] 2015 :38). However, there are also marked differences between the old city, those districts that have developed with a mix of formal and informal planning, and the modernist planned city. These three settlement patterns—historic core, semi-planned and planned—represent key historical phases of urban growth in Dhaka (Fig. 1 ) and are the most evident morphological patterns in contemporary Dhaka (Nilufar 2011 ). Figure 2 shows typical streetscapes from mainstreets of each of these three areas. While each is informalised they also represent increasing levels of formalisation. For this study, five mixed-use buildings have been chosen from each of these districts in order to show the range across the city, but also to better understand the extremes of mix within each district.

Dhaka and the three sample districts (Map based on Nilufar 2011 ; Google Earth)

Typical streetscapes from each district (Photos: Fatema Meher Khan & Kim Dovey)

Islampur in the Historic Core is located at the southern edge of Dhaka. This area has long been the centre for a wide range of wholesale and retail markets with different professional groups who used to live in the shop-houses (Mohsin 1991 ). A rich mix of uses has been embedded within the fabric of this area since its inception in 1600 and has increased and intensified over time informally into a mix of housing, retail, wholesale, offices, workshops, go-downs (warehouse/shop) and light industries. There were attempts to impose formal land-use planning codes in this district but the state lacked the power to enforce them (Jahan 2011 ). This zone is seen as most problematic and is the scene of the fires mentioned earlier. The second area, known as Green Road, is a semi-planned neighbourhood near the spatial centre of Dhaka that has developed since the 1960s with a combination of formal and informal street networks. While initially, it was a middle-income residential area, other uses such as shops, workshops and offices have spontaneously developed over time. After 2000, a part of this area was declared commercial, this effectively formalised the mix of functions in those areas, however, non-residential functions in residential areas remain informal. The third area, Uttara, is a planned neighbourhood located on the northern periphery of Dhaka, developed since the 1980s with a regular grid and plot size. Although initially planned as a residential neighbourhood, it has informally developed other functions including shops, cafes, restaurants, and offices over time. Again, mixed functions on the main roads have become authorised over time, while non-residential functions on other streets remain unauthorised. The 5 buildings selected from each of these sites represent a range of mixed-use buildings in each case, but with a focus on denser buildings which test the extremes of mixed-use, avoiding simple low-rise shop-houses.

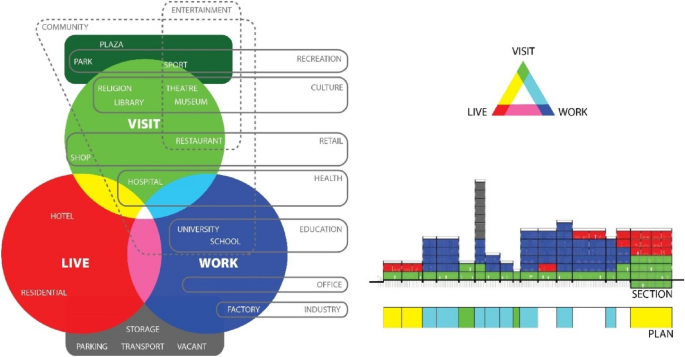

The method of categorizing building functions deployed here has been adapted from the work of van Hoek ( 2008 ) who suggests that urban functions be divided into three primary categories that we call ‘live’, ‘work’, and ‘visit’, plus the various forms of mix that emerge between them (Fig. 3 ). This live/work/visit model (Dovey and Pafka 2017 ) is based primarily on the argument that the population in a building, street, or neighbourhood at any particular time can be understood as a mix of those who live there, work there, or visit the place. Most previous studies have considered urban functions in categories such as residential, industrial, commercial, retail, education, entertainment, recreation, health, transport, government, community, parking, vacant, hospitality, etc., which is a modernist way to segregate the city into different categories. Such categorisations are problematic for two major reasons. Firstly, with so many categories/sub-categories, it is difficult to measure and map complex cities with any coherence. Secondly, there is a problem of consistency since the boundaries of any of these categories overlap and can become subsets of another.

The live/work/visit triangle (based on Dovey and Pafka 2017 )

This approach is based on a live/work/visit triangle utilizing the points of the triangle for living (red), working (blue) and visiting (green) with the interstitial colours to indicate the different forms of mix between them (Fig. 3 ). ‘Live’ incorporates places people sleep overnight. ‘Work’ denotes offices, factories and educational spaces. ‘Visit’ is an umbrella concept for places that are primarily used by visitors such as shops, restaurants, libraries, theatres, museums, parks and recreation (Dovey and Pafka 2017 ). A live/visit mix is represented as yellow; a live/work mix as magenta and a work/visit mix as cyan; a mix of all three will be white. Figure 3 also shows how this method of analysis can be used to show the vertical layering of primary functions of buildings in section and the ways this produces mixed colours when viewed in the plan.

In order to conduct a comparative analysis of the interrelations between functions within each building, we have conducted an adaptation of gamma analysis derived from space syntax analysis. A ‘justified gamma diagram’ is one of the analytical methods developed by Hillier and Hanson ( 1984 ) to study the ‘social logic’ of the relationships between spaces within buildings and the depth of those spaces from the street. In this process, architectural plans are translated into diagrams of topological segments (Ostwald 2011 : 445; Dovey 2008 ). Thus the circulation pattern of the building can be identified along with the ways in which the building plan produces separations and intersections between access routes. In the process of the structuring of gamma diagrams, every space in a building is allocated a depth value, according to the minimum number of spatial segments that one must pass through to arrive in that space from the street. These diagrams reduce the plan to a set of spatial segments represented by circles with permeable connections represented by lines. This method produces diagrams of spatial permeability with all spaces of the same depth lined up horizontally at each level away from the street (Hillier and Hanson 1984 : 147–149). Because they rely on passing trade, shops are typically one level deep from the street. A stairway between floors is diagrammed as one segment.

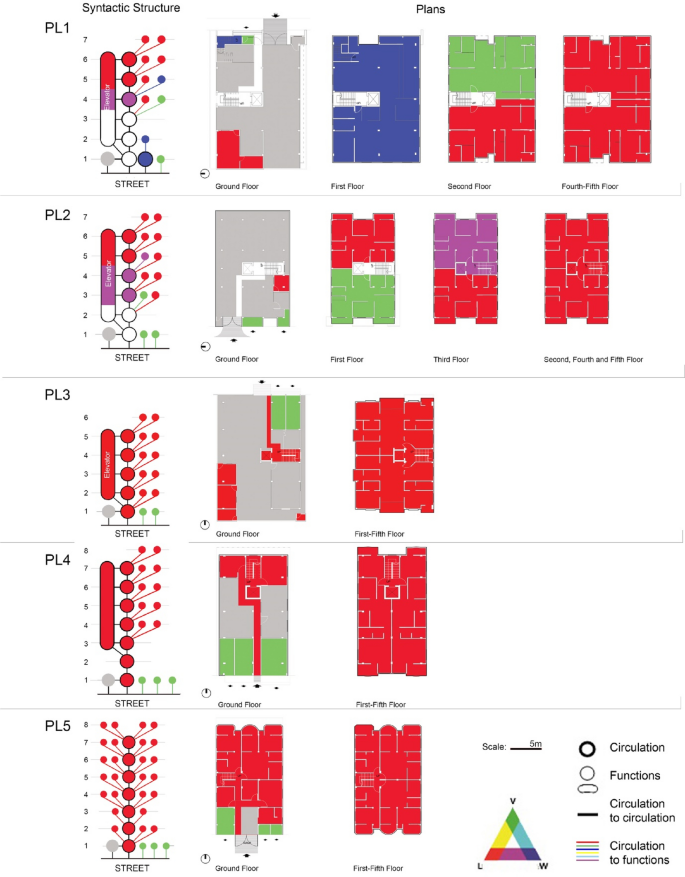

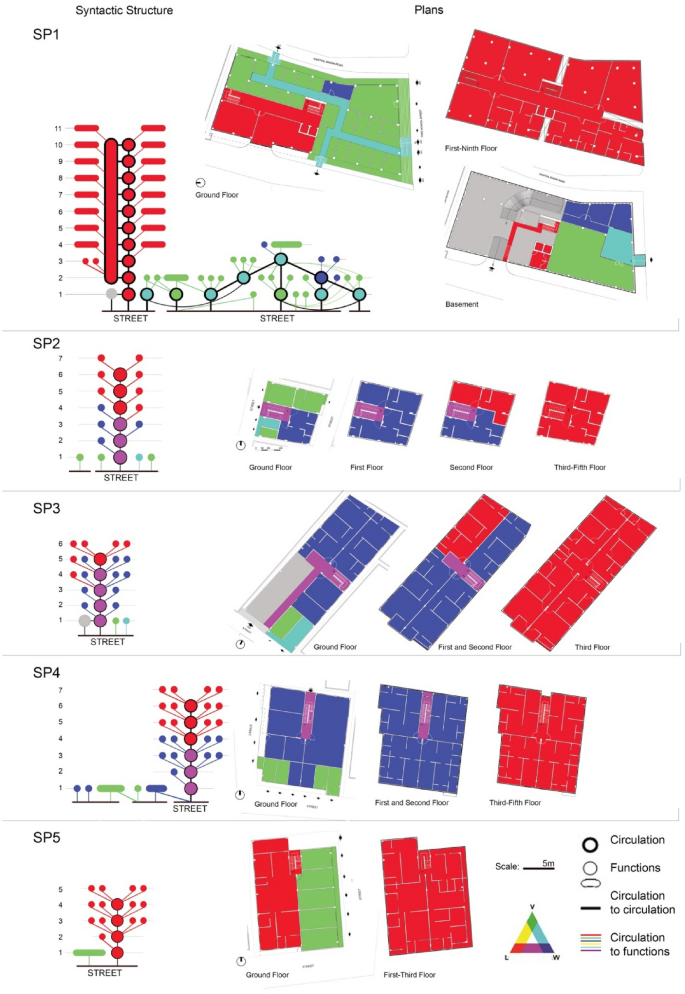

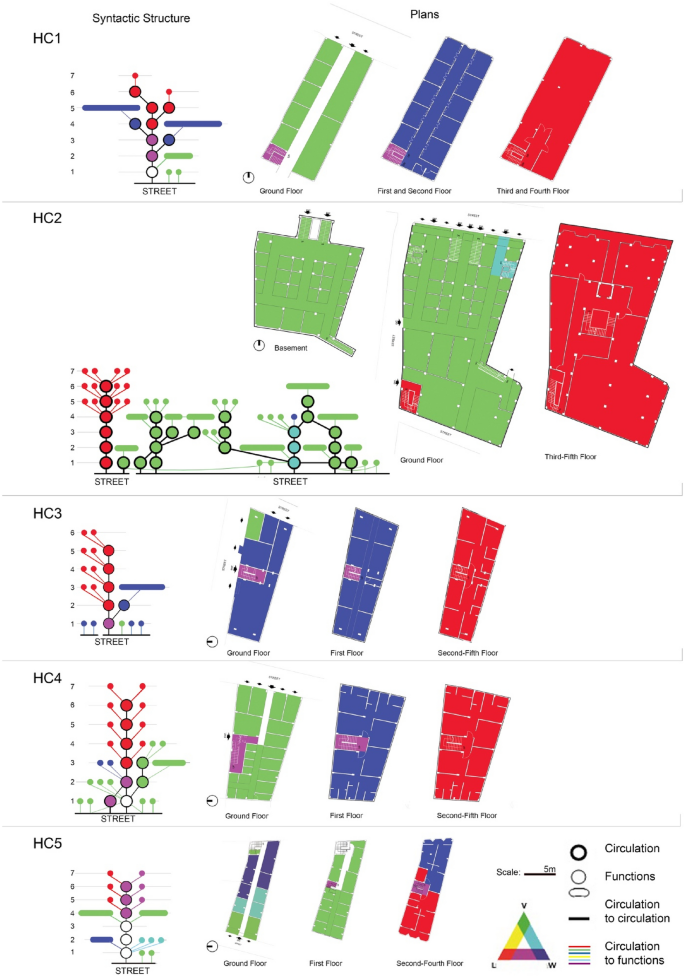

Syntactic analysis

This section presents the syntactic analyses of selected buildings from each from the Planned (PL), Semi-Planned (SP) and Historic Core (HC) districts - a sequence of increasing informality and complexity of functional mix. In each case, we show both gamma diagrams and floor plans, colour coded according to the live/work/visit triangle described above. The circles outlined with thick lines represent the main circulation routes of each building; these are also colour coded by the functions to which they give access. In order to make these diagrams readable, clusters of segments with similar functions are represented with elongated boxes to indicate a number of segments in a cluster. The circulation lines are also colour coded by the various uses to which they provide access. A comparative analysis of these gamma diagrams will follow.

We first consider examples from the more recently Planned areas on the urban periphery (Fig. 4 ) where all buildings were initially designed as mono-functional residential buildings. All 5 examples are 6 storeys high on similar plots; all except the final example have substantial parking at ground level and elevator access to upper floors. The key interest here is in the ways functions have been transformed. PL1 has a central circulation spine that begins with a triple mix (white) of live/work/visit, which gradually becomes live/work (magenta) and then residential (red), as it penetrates deeper into the building. PL2 mixes living, working and visiting on the 4 lower floors; separate shops have emerged on the street frontage of the ground floor which is otherwise devoted to parking. PL3 largely remains mono-functional with just a few shops with separate access at street level. In PL4 and PL5 large portions of ground floor parking have been converted to retail with housing above, but without mixing of entries. This part of Dhaka was planned as mono-functional residential but clearly needs retail to function effectively. Additional visit and work functions that have emerged on upper levels include a dental clinic, school and beauty parlour.

Syntactic analysis of buildings from Planned Areas (PL)

Syntactic analysis of buildings from Semi-Planned Areas (SP)

Considering examples from the Semi-Planned area (Fig. 5 ), SP1 is a 10 storey building that contains two quite separate circulation systems with a complex retail network on the ground floor and housing (with elevator) above. The functional mix is thus confined to the ground floor and basement. SP2 is a 6 storey residential building where office functions have replaced apartments on the 1st and 2nd floors, while retail has separate entries on the street. SP3 is a 4 storey building that is primarily occupied by offices, but mixed with residential on the two middle floors; the main access spine is mostly a live/work mix (magenta). SP4 is a 6 storey building on a street corner with 10 street entries for shops and offices plus a separate entry to the residential floors above. These floors have become mixed with offices up to the 2nd floor. SP5 is a 4 storey building with a mono-functional residential tree-like structure and separate entries for the ground floor shops.

Finally, we consider the more extreme examples from the Historic Core (Fig. 6 ). HC1 is a 5 storey building entered through a shopping arcade with warehouse/shops (go-downs) on the 1st and second floors and residential above. The circulation has a tree-like structure comprising visit, work, and living at progressive depths. The go-downs extend 5 segments deep while residences extend 7 segments deep. Shops are accessed both from the street and arcade. Mixed circulation is confined to the first three floors and becomes progressively less mixed as it penetrates deeper. HC2 is a 6 storey building with a network of shops on the ground floor, multiple street entries and interconnecting corridors that penetrate up to 6 segments deep. Residential apartments on the 3rd to 5th floors are accessed through a separate stair from the street and have an elevator from the 3rd floor. Here there is a notable contrast between the networked access structure for the shops (with 10 street entries) and a tree-like structure for the housing. HC3 is a 5 storey building with primarily work-related functions (printing) on the ground and first floors with residential above. HC4 is a 6 storey building that combines visit, work and living at progressive levels. It has shops and offices on the ground and first floors with residences above. The mixed circulation penetrates 2 segments deep, moving from a triple mix to live/work and then residential. HC5 is a 5 storey building that mixes retail with work on the first two floors and then work with residential on the three floors above. The single white and magenta access spine indicates that shoppers, workers and residents all use the same access route. Some of the shops (book-binding) are located up to 4 segments deep from the street. The work functions on the upper floors (go-downs) share a kitchen with residential functions. Hence, the combination of working (blue) and living (red) on the upper floors is represented by the mix of live/work access (magenta) on the diagram.

Syntactic analysis of buildings from the Historic Core (HC)

Patterns of Mix

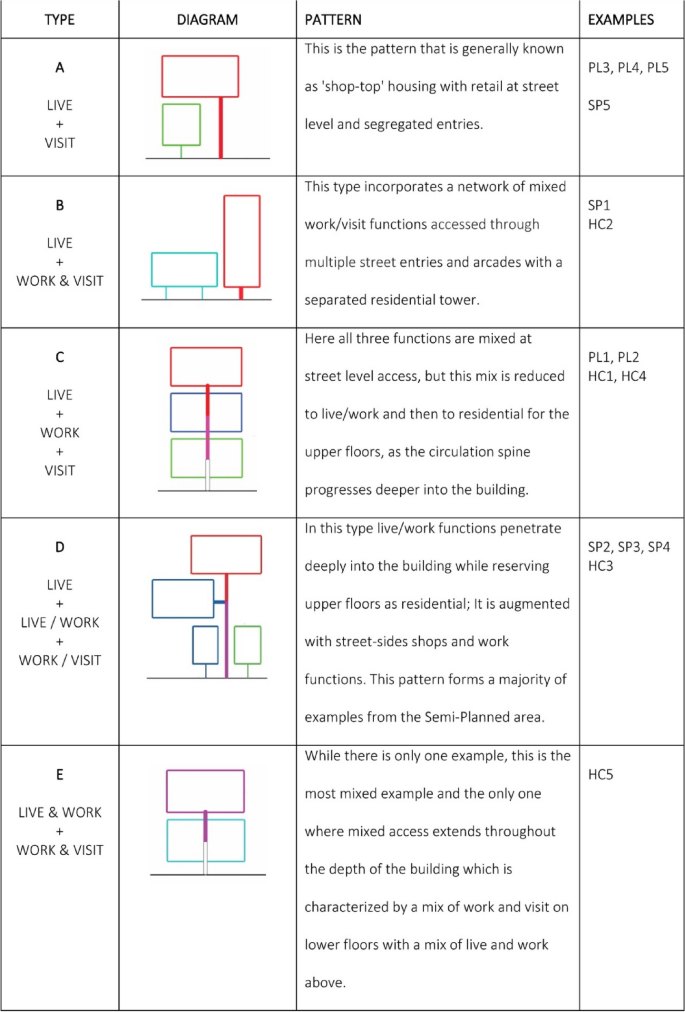

We can see in these examples what may seem a bewildering range of ways in which these buildings mix functions in different ways and to different degrees. While it is not our goal to reduce this field of differences to any kind of essential types, we want to find a way to understand spatial patterns that are evident in this production of vertical mixed-use in buildings. We now take one further step beyond the gamma diagrams to suggest that these mixed-use buildings can be broadly categorised into 5 diagrammatic types with different circulation systems. While the floor areas devoted to different functions are evident on the plans, our primary concern here is to understand the ways mixed-use buildings mix or separate access routes in everyday life. Figure 7 presents a typology of mixed-use buildings representing the typical patterns of vertical mix circulations that are identifiable within the 15 cases. Each of these types is identified first as a relational diagram, followed by a brief description and the examples listed in the final column. In the generic diagrams, the complexities of individual spaces are collapsed in order to reveal spatial clustering by function and connectivity, while also revealing the overall depth or shallowness from the street. In these diagrams, the representation of different functions and their mixes follows the live/work/visit triangular model used earlier in this study. The main circulation spines are represented by thick lines; those with mixed colours (magenta, cyan, white) indicate mixed access spaces.

Figure 7 shows that some types are more common than others, however, this is not a random sample and we are more interested in the range of types. Type A is the vertical mix of live and visit functions often known as ‘shop-top housing’; it is the only type where functions and entries are fully segregated. This is typical in more formal cities and it is not surprising to find it mostly in the Planned Areas. Type B incorporates a complex access network with multiple street entries and arcades giving access to both work and visit functions with separate access to a residential tower above. The mixing of access routes is confined to work/visit which again is typical in more formal cities. Type C is a stack of visiting, working and living functions in a vertical sequence with a single spine of mixed access. Thus all three functions are mixed at street level, but this mix is reduced to live/work and then to residential for the upper floors, as the circulation spine progresses deeper into the building. This type is mostly produced by the informal adaptation of residential buildings. Type D is similar but with retail and some work functions separated at street level - thus there is no mixing of retail and residential access. While there is only one example of type E in our study, this is the most mixed example and the only one without any mono-functional access—mixed access extends throughout the depth of the 5 storey building.

A typology of mixed-use buildings

These generic syntactic diagrams demonstrate that visiting, working and living functions generally remain in a consistent sequence of progressive depth in buildings. Shops typically remain at the shallowest position, as they depend on accessibility for their business. They often extend deep into ground floor plans and sometimes to the 1st and 2nd floors. Work functions are often mixed with shops on the ground floor but more commonly extend to intermediate floors as in types C and D. Residential functions always occupy the deepest and most private sector of the building. Figure 7 also shows the ways the different types are distributed across the three areas of the city from which examples were chosen. In general terms, the Historic Core has more complex and mixed examples while the Planned areas have more segregated functions. This reflects the fact that the Historic Core has always been mixed while buildings in the Planned and Semi-Planned areas were initially designed as mono-functional and have become informally mixed over time.

In this study, we have mapped and analysed functional mix within selected buildings of an extremely mixed informal city. These examples are not random nor typical, they have been chosen as the most mixed cases in each study area because they embody this extreme and test the limits of functional mixing within buildings. These buildings have been analysed through methods that reveal typical circulation patterns and the mixing of different functions within them. While the building plans and syntactic diagrams are empirically interesting (Figs. 4 , 5 and 6 ), the key findings of the paper lie in the generic diagrams that reveal broader patterns of vertical mix and circulation systems (Fig. 7 ). This work also enables further critique on the benefits and challenges of different forms of vertical functional mix. It is not our purpose here to make judgements about the effectiveness or otherwise of different kinds of functional mix based on this data, however, it is possible to discern a certain spatial logic, linked to the economic and social logic of the city.

While these mixed-use buildings involve challenges at the micro-scale of storage of noxious materials and social encounters, it also has significant benefits at the broader scale. Informal adaptation to a greater mix serves city dwellers by filling the gaps between demand and available services; in this way, the mix contributes to the local economy. The informal conversions are generating a more walkable and lively urban environment by integrating diverse functions, activities and people—a quality that is often missing in the modernist planned areas. While this city clearly needs greater regulation, these neighbourhoods are more walkable and efficient because of the mix and would be quite dysfunctional without it.

When we look at the circulation spaces of the syntactic diagrams we note a considerable amount of mixing of work/visit (cyan) and work/live (magenta), a few spaces that mix all three functions (white), but never live/visit (yellow). In other words, whenever residential access becomes mixed it is always mixed with production functions first and only occasionally with shopping as well. There are clear synergies in the mixing of work and visit functions that are not present when either of these functions is mixed with residential. These are not the kinds of synergy that originally drove the proliferation of the shophouse where one lived over the store and often entered the home through it (Davis 2012 ). Thus the synergy between residential and retail that produces shop-top housing—the form of functional mix that works so well in almost any highly urbanized city—depends on a separation of these functions within each building.

The issues of functional mix cannot be considered separately from the range of morphological factors that frame the ways it emerges; particularly in relation to street interface conditions and density. The capacity to design separate access routes into each building depends to a significant degree on the capacity for multiple street entries—the cases in our sample range from 3 to 11 street entries each with an average of 4–6. This capacity will depend in turn on plot size and block location—a larger plot size and corner location produce more capacity for multiple street entries. Figures 4 , 5 and 6 show that the more informal districts have a much less regular plot size and shape, with a greater average and range of street entries. By contrast, significant parts of the street frontage in the planned area are consumed by carpark entries. In general, the unplanned areas have a greater capacity to produce separated entries.

The issues and challenges that emerge in relation to an extreme functional mix cannot be extricated from questions of density. The buildings we have considered range from 4 to 10 storeys; plot coverage in most cases is close to 100% and net floor area ratios range from 2.8 to 6.0. While these building densities are not uncommon in Dhaka, they are very high by global standards (Dovey and Pafka 2014 ). Population densities are also extremely high, whether in terms of residential populations, jobs or streetlife—the same live/work/visit categories used for the functional analysis. Many of these internal spaces have very high population densities in terms of overcrowded housing, offices, workshops and shops. It is important to understand that a problem that may appear to be caused by the mix, may not be a problem at a lower density; it is not just the fact of mixing different populations within circulation spaces but the intensity of this mix.

Many of these buildings, especially in the Planned district, were originally designed as mono-functional but have been informally adapted to various forms of mixed-use. The key dynamic here has been one of residential space converted to workshops, offices, shops, schools and so on. While shops and offices may be interconvertible, there are no examples of them being converted into apartments. It is clear that economic forces are the key drivers—work and visit functions bring higher rents in those spaces closer to the street. Depending on the ways in which the building was initially designed, it will have varying levels of capacity to adapt. If there is a single circulation spine and no space for additional entries then such entry spaces will be mixed. This will reduce the amenity and security of all remaining residential apartments, also reducing the rental value and increasing affordability. Thus the functional mix within buildings is linked to the socio-economic profile of residents.

The two greatest challenges embodied in the extreme forms of vertical mix we have documented here are the risk of fire and the social difficulties of shared access. The deadly fires that have occurred in Dhaka are often seen as due to an incompatible mix of functions, where noxious or dangerous materials are stored in spaces where any resulting fire is difficult to control or escape from. However, this problem could be addressed through stricter control of storage, workplace safety and fire egress without changing the functional mix. The challenge here is partly local because there is such a strong tradition of the go-down—the small shop that is also a warehouse.

The social issues that mixed-use functions usually cause are privacy and security. The informal transformation of residential buildings from mono-functional to mixed-use often generates shared circulation spaces where public access penetrates deeply into the upper floors, compromising the privacy and security of residences. It is imperative that work and visit functions achieve this public access for their business. The gamma diagrams in Figs. 4 , 5 and 6 show these levels of penetration graphically; they also show that even the most dense and complex buildings can be designed with segregated access.

In as much as mono-functional planning has been damaging to the city, the adaptation of residential buildings to mixed-use functions is a benefit. The planning challenge lies not in micro-managing what the mix should be but in protecting citizens from negative outcomes. The formal controls of the state should focus on proscribing certain outcomes rather than prescribing particular functions. It is important to acknowledge the benefits of informal adaptation within a formal planning framework. It is also necessary to identify and address the key problems related to informal mix in buildings. The control of mixed entries is a complex issue that requires a better understanding of the relations between formal and informal processes in any city. While the separation of residential entries is generally preferable, there may be advantages in blurring the boundaries between home and work - as is happening in more formal cities. Housing that is entered through mixed entry spaces may have difficulties in terms of privacy and security that other housing does not, however, it will also be more affordable and adaptable. It is not the role of the state to enforce the segregation of entries. The broad challenge, both in Dhaka and other highly informalised cities of the global South, is to develop forms of urban planning that can address the challenges of a dysfunctional mix without destroying the vitality and productivity of the mixed-use district.

Chun HK, Hassan AS, Noordin NM (2005) An Influence of Colonial Architecture to Building Styles and Motifs in Colonial Cities in Malaysia. Paper presented at the 8th International Conference of the Asian Planning Schools Association, Penang, 12–14 September 2005

Davis H (2012) Living over the store. Routledge, London

Book Google Scholar

Dovey K (2008) Framing places. Routledge, London

Google Scholar

Dovey K, Pafka E (2014) The urban density assemblage. Urban Des Int 19(1):66–76

Article Google Scholar

Dovey K, Pafka E (2017) What is functional mix? Plann Theory Pract 18(2):249–267

Dovey K, Pafka E (2020) What is walkability? The urban DMA. Urban Stud 57(1):93–108

Frank LD, Sallis JF, Conway TL et al (2006) Many pathways from land use to health: associations between neighborhood walkability and active transportation, body mass index, and air quality. J Am Plann Assoc 72(1):75–87

Grant J (2002) Mixed use in theory and practice. J Am Plann Assoc 68(1):71–84

Han W, Beisi J (2016) Urban morphology of commercial port cities and shop-houses in Southeast Asia. Proc Eng 142:189–196

Haque NU (2015) Flawed urban development policies in Pakistan. PIDE working paper 119, Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, Islamabad

Hillier B, Hanson J (1984) The social logic of space. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Hoek JW van den (2008) The MXI (Mixed-use Index) as tool for urban planning and analysis. Corporations and Cities, Delft University of Technology 1–15

Hoppenbrouwer E, Louw E (2005) Mixed-use development. Eur Plan Stud 13(7):967–983

Imam H (2010) Nimtoli tragedy: the worst nightmare. In: The Daily Star, 12 June. https://www.thedailystar.net/news-detail-142316 . Accessed 30 Apr 2021

Imamuddin AH, Hassan SA, Alam W (1989) Shakhari Patti: a unique old city settlement, Dhaka. Protibesh, Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET) lll(2)

Jacobs J (1961) The death and life of great American cities. Vintage Books, New York

Jahan S (2011) Dhaka: an urban planning perspective. In: Ahmed S, Hafiz R, Rabbani A (eds) 400 years of capital Dhaka and beyond, vol 3: The Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka

Khan FM (2020) Functional mix and changing morphology of Dhaka. PhD Thesis, University of Melbourne

Khan FM, Pafka E, Dovey K (2021) Understanding informal functional mix: morphogenic mapping of Old Dhaka. J Urban Int Res Placemaking Urban Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2021.1979085

Mohsin KM (1991) Commercial and industrial aspects of Dhaka in the eighteenth century. In: Ahmed SU (ed) Dhaka past present future. The Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka

Molla MAM (2019) Nimtoli to Chawkbazar. In: The Daily Star, 22 February. https://www.thedailystar.net/frontpage/news/dhaka-fire-nimtoli-chawkbazar-lesson-not-learnt-1705771 . Accessed 30 Apr 2021

Nahrin K (2008) Violation of land use plan and its impact on community life in Dhaka city. Jahangirnagar Plann Rev 6:39–47

Nilufar F (2011) Urban morphology of Dhaka city: spatial dynamics of growing city and the urban core. In: Ahmed S, Hafiz R, Rabbani A (eds) 400 years of capital Dhaka and beyond, vol 3: The Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka

Ostwald MJ (2011) The mathematics of spatial configuration. Nexus Netw J 13(2):445–470

Phuong DQ, Groves D (2010) Sense of place in Hanoi’s shop-house. J Interior Des 36(1):1–20

Rabianski JS, Gibler K, Tidwell OA, Clements JS (2009) Mixed-use development. J Real Estate Lit 17(2):205–230

Rajdhani Unnayan Kartripakkha—RAJUK (2015) Dhaka Structure Plan: 2016–2035. Dhaka. ( http://www.rajukdhaka.gov.bd/rajuk/image/slideshow/5.Chapter%2002.pdf)

Su-Jan Y, Limin H, Kiang H (2012) Urban informality and everyday (night) life: a Field Study in Singapore. Int Dev Plann Rev 34(4):369–390

Susantono B (1998) Transportation land use dynamics in metropolitan Jakarta. Berkeley Plann J 12(1):126–144

Tipple AG, Kellett PW, Masters GA (1996) Mixed use in residential areas. Final report for ODA research project 6265, Centre for Architectural Research and Development Overseas. University of Newcastle upon Tyne

Tishi TR, Islam I (2019) Urban fire occurrences in the Dhaka Metropolitan Area. Geo J 84(3):1417–1427

Ujang N, Shamsuddin S (2008) Place attachment in relation to users’ roles in the main shopping streets of Kuala Lumpur. In: Bashri A, Mai MM (eds) Urban design issues in the developing world. Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Malaysia

Verma DG (1993) Inner city renewal: lessons from the Indian experience. Habitat Int 17(1):117–132

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Architecture, Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET), Dhaka, Bangladesh

Fatema Meher Khan

Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia

Elek Pafka & Kim Dovey

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors have taken part in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors information

Fatema Meher Khan is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Architecture at the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET). Her research interest lies in urban design and planning, morphological aspects, and informal urbanism. Some of her research papers are on mixed-use function, urban morphological transformation, and social equity. Elek Pafka is Senior Lecturer in Urban Planning and Urban Design at the Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning at the University of Melbourne. His research focuses on the relationship between material density, urban form and the intensity of urban life, as well as methods of mapping the ‘pulse’ of the city. He has participated in research on transit oriented development, functional mix and walkability. He has co-edited the book Mapping Urbanities: Morphologies, Flows, Possibilities . Kim Dovey is Professor of Architecture and Urban Design at the University of Melbourne, where he is also Director of InfUr- the Informal Urbanism Research Hub. He has published and broadcast widely on social issues in architecture, urban design and planning. Books include 'Framing Places', 'Fluid City', ‘Becoming Places’, ‘Urban Design Thinking’ and ‘Mapping Urbanities'.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Fatema Meher Khan .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Khan, F.M., Pafka, E. & Dovey, K. Extremes of mixed-use architecture: a spatial analysis of vertical functional mix in Dhaka. City Territ Archit 9 , 31 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40410-022-00177-y

Download citation

Received : 21 July 2021

Accepted : 23 September 2022

Published : 14 October 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40410-022-00177-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mixed-use building

- Informality

- Urban morphology

- Land use planning

Accessibility Links

- Skip to content

- Skip to search IOPscience

- Skip to Journals list

- Accessibility help

- Accessibility Help

Click here to close this panel.

Purpose-led Publishing is a coalition of three not-for-profit publishers in the field of physical sciences: AIP Publishing, the American Physical Society and IOP Publishing.

Together, as publishers that will always put purpose above profit, we have defined a set of industry standards that underpin high-quality, ethical scholarly communications.

We are proudly declaring that science is our only shareholder.

Application of green concept on mixed-use building design

M D Lubis 1 , H T Fachrudin 1 , F A S Lubis 2 and P W Dari 2

Published under licence by IOP Publishing Ltd IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science , Volume 878 , The 1st International Conference on Sustainable Architecture and Engineering 28 October 2020, Jakarta, Indonesia Citation M D Lubis et al 2021 IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 878 012008 DOI 10.1088/1755-1315/878/1/012008

Article metrics

1753 Total downloads

Share this article

Author e-mails.

Author affiliations

1 Architecture Department, Engineering Faculty, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Jl. Almamater Kampus USU, Medan 20155, Sumatera Utara, Indonesia

2 Student at Architecture Department, Engineering Faculty, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Jl. Almamater Kampus USU, Medan 20155, Sumatera Utara, Indonesia

Buy this article in print

Green concepts are important things to apply on buildings. The application of the green concept on mixed-use buildings must consider several criteria, one of which is the comfort aspect. The density of commercial buildings in Medan City causes a reduction in green open space, and even many buildings do not comply with the minimum green open space requirements on their buildings, which can support the development of this city to reduce environmental temperatures. The aim of this study is to analyze the green concept that can be applied to mixed-use buildings in urban areas. A mixed-use building design with the application of green building principles is the right choice to reduce the effects of climate. The green building concept can help reduce excess heat radiation inside and outside the building. The method used is qualitative with data collection techniques through observation. The analysis was carried out descriptively to obtain a mixed-use building model with the green building concept. The results show that land use efficiency, energy conservation, materials and water conservation can be applied to provide comfortable on buildings.

Export citation and abstract BibTeX RIS

Content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 licence . Any further distribution of this work must maintain attribution to the author(s) and the title of the work, journal citation and DOI.

- All Architecture

- Multifamily

- Hospitality

- Performing Arts

- Adaptive Reuse & Repurposing

- All Interior Design

- Public Space

- Public & Cultural

- All Master Planning

- Urban Projects

- Office Parks

- All Landscape Architecture

- Streetscapes

- All Experiential Graphic Design

- Signage and Wayfinding

- Branded Environments

- Communication Design

- About Firm Profile Testimonials Our Workplace Awards & Recognition

- People Our Team Industry Leadership Community Action

- Login Employee FTP Webmail

Architecture

- Interior Design

Master Planning

- Landscape Architecture

- Experiential Graphic Design

- Firm Profile

- Testimonials

- Our Workplace

- Awards & Recognition

- Industry Leadership

- Community Action

Hiranandani Mixed Use

Chennai, India

Fully Integrated Development

Hiranandani mixed use occupies a 24,280 SM site. It is slated for a total gross construction area of 92,900 SM; of which, the five-star hotel tower takes up 25,170 SM, the serviced apartment tower has a gross construction area of 10,450 SM and 20,900 SM of retail space. This mixed use project provides 2,000 spaces of basement parking.

This 250 key, thirteen-story hotel features a 1,400 SM ballroom, three meeting rooms and two boardrooms to accommodate a variety of guest functions. The hotel also provides a variety of food and beverage outlets including an all-day dining restaurant, two specialty restaurants, lobby lounge, pool bar and a quiet bar. The outdoor pool deck is a key feature of this hotel.

The thirteen-story tall serviced apartments offer 100 units. The boutique shopping mall occupies the prominent corner and acts as a buffer for the hotel and serviced apartments from the busy main roads. The project is anchored by several plazas and interconnected with a pedestrian promenade. These plazas also function as magnets to draw in patrons.

Architecture , Retail

Related Projects

Grand Hyatt Noida

Noida, India

Pacific Place Jakarta

Jakarta, Indonesia

Shenyang Hunnan Mixed Development

Shenyang City, Liaoning, China

Emami Tejomaya Residential Development

- Hispanoamérica

- Work at ArchDaily

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Mixed Use Architecture. Shen Nong Shi Cultural and Mixed Use Center / Ürobrous_studiolab AUBE Toranomon Residential Building / ETHNOS

Sustainability. Technology. Materials. Metaverse. 13 projects around the world, including mixed-use buildings, temporary installations, co-workings and co-livings, which promote shared spaces.

Mixed-use architecture including developments with multiple uses, masterplans with several different building types and towers with hybrid programmes.

Case Study: Pittsburgh Mixed-Use Project Combines Preservationist and Sustainability Practices ... In the late 1990s former Pittsburgh mayor Tom Murphy proposed razing 64 historic buildings to make way for an open-air mall as part of a plan to revitalize the city's ailing downtown retail district. ... The premier site for architecture ...

A 141,000-square-foot, transit-oriented mixed-use building on two city blocks in southeast Portland, Oregon. The mixed-income project is built on the former site of a dairy built in 1929. Today, the development features 85 apartments built atop street-level retail stores Including a restaurant, a hair salon, and a 20,000-square-foot grocery.

Mixed-use architecture explores the maximum potential of what one structure can do, especially in urban areas. It builds a sense of community by serving several different requirements at one time and attracting a diverse crowd of people. It can also create an ecosystem where one function can support and funnel into the other.

At each period, KPF has been a major contributor to the evolution of the mixed-use building type. Trajan's Market, 110 AD. The completion of KPF's 1989 900 North Michigan Avenue was one of the first buildings on Magnificent Mile with a vertical, varied program. The building combines five major uses: a shopping mall with Bloomingdales as an ...

Aim of the Project The aim of this project is to develop the commercial land into a symbolic mixed-use skyscraper and also help in shaping the future skyline of the city by being an inspiration ...

Stantec - Buildings Group, USA ABSTRACT This examines The Eddy, a new construction mixed-use, multifamily residential project in Boston, MA USA as a model for sustainable and resilient urban waterfront redevelopment that celebrates place - rather than evoking fear - while building a sense of community and continuity along the waterfront.

Mixed-use developments are a vital strategy in revitalizing urban areas and breathing new life into neglected neighborhoods. By repurposing existing buildings or integrating new ones, architecture ...

ITC MIXED USE DEVELOPMENT IN KOLKATA. CASE STUDY - LINKED HYBRID, BEIJING, CHINA. OVER ALL SECTION ... (SUSTAINABLE ARCHITECTURE) The building is a G + 12 structure with two basement. The floor ...

The concept of mix-use has begun to be widely applied to cities which aim to make it easy for denizens to access given areas. Mix-use integrates various functions within a building or within an ...

The concept of mixed-use is now well-established as an urban design and planning principle that adds to the vitality, walkability and productivity of the city at neighbourhood scale. There is much less research on the dense and complex vertical mix of functions within buildings. This paper investigates the extremes of informal vertical mixing of functions within buildings in Dhaka, where ...

VCU Scholars Compass | Virginia Commonwealth University Research

The aim of this study is to analyze the green concept that can be applied to mixed-use buildings in urban areas. A mixed-use building design with the application of green building principles is the right choice to reduce the effects of climate. The green building concept can help reduce excess heat radiation inside and outside the building.

A mixed-use building Case study - Free download as Word Doc (.doc / .docx), PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or read online for free. RUTE Shopping Center is a mixed-use building located in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. It combines commercial and office spaces. The building covers approximately 960 square meters over 8 floors. The ground to second floors contain various shops, while the third to ...

Hiranandani mixed use occupies a 24,280 SM site. It is slated for a total gross construction area of 92,900 SM; of which, the five-star hotel tower takes up 25,170 SM, the serviced apartment tower has a gross construction area of 10,450 SM and 20,900 SM of retail space. This mixed use project provides 2,000 spaces of basement parking. This 250 ...

From the developer's perspective a mixed-use development is identified as being. a popular format because it is perceived as providing the following benefits: Convenience of live-work-play options in a single location. Satisfying the desire to live in more of a small-town (e.g. "Main Street") environment.

Literature Review and Case Study on Mixed Useby Semahegn Demeke 1 - Free download as PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or read online for free. Literature Review and Case Study on Mixed Use

Mixed Use Architecture. Top architecture projects recently published on ArchDaily. The most inspiring residential architecture, interior design, landscaping, urbanism, and more from the world's ...