The Chemistry of Love: Why Do We Fall in Love?

The Chemistry of Love and Its Ingredients

Maybe you think falling in love is only explainable through a neurochemical lens. Or that attraction is the result of a formula whose variables line up with the chemistry of love and the neurotransmitters involved in the process. Where our impulsive brain orchestrates the magic, desire, obsession…

It’s not like that. Everyone one of us has specific, deep, idiosyncratic, and sometimes even unconscious preferences.

In fact, there’s clear evidence that we tend to fall in love with people who have similar characteristics. They have a similar level of intelligence, the same sense of humor, the same values…

But there’s something remarkable and fascinating here. We can be in a classroom with 30 people with similar characteristics as us. They might have similar tastes and equal values, and we’ll never fall in love with any of them.

The Indian poet and philosopher Kabir said the path of love is long, and there’s only space for one person in the heart. Then… what other factors put us in the spell we call the chemistry of love?

“Dopamine, norepinephrine, serotonin…We’re a natural drug factory when we fall in love.” -Helen Fisher-

The Aroma of Genes

Intangible, invisible, and imperceptible. If we tell you right now that our genes give off a specific smell capable of awakening attraction between some people and not others, you may raise your eyebrows in skepticism.

- But there’s something other than our genes that gives off a specific smell. We’re not conscious of it, but it guides our patterns of attraction. It’s our immune system, and more specifically, our MHC proteins.

- These proteins have a very specific job to do in our bodies: they trigger our defensive reactions.

- We know, for example, that women feel unconsciously more attracted to men with a different immune system than them. It is smell that guides them in this process. If they prefer genetic profiles different from their own, there’s a reason. That is, if this couple has children, they’ll come with a more mixed genetic set.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.14(1); 2013 Jan

The biochemistry of love: an oxytocin hypothesis

C Sue Carter

1 C Sue Carter and Stephen W Porges are research scientists at the Research Triangle Institute International in Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, USA

Stephen W Porges

Love is deeply biological. It pervades every aspect of our lives and has inspired countless works of art. Love also has a profound effect on our mental and physical state. A ‘broken heart’ or a failed relationship can have disastrous effects; bereavement disrupts human physiology and might even precipitate death. Without loving relationships, humans fail to flourish, even if all of their other basic needs are met.

As such, love is clearly not ‘just’ an emotion; it is a biological process that is both dynamic and bidirectional in several dimensions. Social interactions between individuals, for example, trigger cognitive and physiological processes that influence emotional and mental states. In turn, these changes influence future social interactions. Similarly, the maintenance of loving relationships requires constant feedback through sensory and cognitive systems; the body seeks love and responds constantly to interaction with loved ones or to the absence of such interaction.

Without loving relationships, humans fail to flourish, even if all of their other basic needs are met

Although evidence exists for the healing power of love, it is only recently that science has turned its attention to providing a physiological explanation. The study of love, in this context, offers insight into many important topics including the biological basis of interpersonal relationships and why and how disruptions in social bonds have such pervasive consequences for behaviour and physiology. Some of the answers will be found in our growing knowledge of the neurobiological and endocrinological mechanisms of social behaviour and interpersonal engagement.

Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution. Theodosius Dobzhansky's famous dictum also holds true for explaining the evolution of love. Life on Earth is fundamentally social: the ability to interact dynamically with other living organisms to support mutual homeostasis, growth and reproduction evolved early. Social interactions are present in primitive invertebrates and even among prokaryotes: bacteria recognize and approach members of their own species. Bacteria also reproduce more successfully in the presence of their own kind and are able to form communities with physical and chemical characteristics that go far beyond the capabilities of the individual cell [ 1 ].

As another example, insect species have evolved particularly complex social systems, known as ‘eusociality’. Characterized by a division of labour, eusociality seems to have evolved independently at least 11 times. Research in honey-bees indicates that a complex set of genes and their interactions regulate eusociality, and that these resulted from an “accelerated form of evolution” [ 2 ]. In other words, molecular mechanisms favouring high levels of sociality seem to be on an evolutionary fast track.

The evolutionary pathways that led from reptiles to mammals allowed the emergence of the unique anatomical systems and biochemical mechanisms that enable social engagement and selectively reciprocal sociality. Reptiles show minimal parental investment in offspring and form non-selective relationships between individuals. Pet owners might become emotionally attached to their turtle or snake, but this relationship is not reciprocal. By contrast, many mammals show intense parental investment in offspring and form lasting bonds with the offspring. Several mammalian species—including humans, wolves and prairie voles—also develop long-lasting, reciprocal and selective relationships between adults, with several features of what humans experience as ‘love’. In turn, these reciprocal interactions trigger dynamic feedback mechanisms that foster growth and health.

Of course, human love is more complex than simple feedback mechanisms. Love might create its own reality. The biology of love originates in the primitive parts of the brain—the emotional core of the human nervous system—that evolved long before the cerebral cortex. The brain of a human ‘in love’ is flooded with sensations, often transmitted by the vagus nerve, creating much of what we experience as emotion. The modern cortex struggles to interpret the primal messages of love, and weaves a narrative around incoming visceral experiences, potentially reacting to that narrative rather than reality.

Science & Society Series on Sex and Science

Sex is the greatest invention of all time: not only has sexual reproduction facilitated the evolution of higher life forms, it has had a profound influence on human history, culture and society. This series explores our attempts to understand the influence of sex in the natural world, and the biological, medical and cultural aspects of sexual reproduction, gender and sexual pleasure.

It also is helpful to realize that mammalian social behaviour is supported by biological components that were repurposed or co-opted over the course of mammalian evolution, eventually allowing lasting relationships between adults. One element that repeatedly features in the biochemistry of love is the neuropeptide oxytocin. In large mammals, oxytocin adopts a central role in reproduction by helping to expel the big-brained baby from the uterus, ejecting milk and sealing a selective and lasting bond between mother and offspring [ 3 ]. Mammalian offspring crucially depend on their mother's milk for some time after birth. Human mothers also form a strong and lasting bond with their newborns immediately after birth, in a time period that is essential for the nourishment and survival of the baby. However, women who give birth by caesarean section without going through labour, or who opt not to breast-feed, still form a strong emotional bond with their children. Furthermore, fathers, grandparents and adoptive parents also form lifelong attachments to children. Preliminary evidence suggests that simply the presence of an infant releases oxytocin in adults [ 4 , 5 ]. The baby virtually ‘forces’ us to love it ( Fig 1 ).

As a one-year-old Mandrill infant solicits attention, she gains eye contact with her mother. © 2012 Jessie Williams.

Emotional bonds can also form during periods of extreme duress, especially when the survival of one individual depends on the presence and support of another. There is also evidence that oxytocin is released in response to acutely stressful experiences, possibly serving as hormonal ‘insurance’ against overwhelming stress. Oxytocin might help to assure that parents and others will engage with and care for infants, to stabilize loving relationships and to ensure that, in times of need, we will seek and receive support from others.

The case for a major role for oxytocin in love is strong, but until recently has been based largely on extrapolation from research on parental behaviour [ 4 ] or social behaviours in animals [ 5 , 6 ]. However, human experiments have shown that intranasal delivery of oxytocin can facilitate social behaviours, including eye contact and social cognition [ 7 ]—behaviours that are at the heart of love.

Of course, oxytocin is not the molecular equivalent of love. It is just one important component of a complex neurochemical system that allows the body to adapt to highly emotive situations. The systems necessary for reciprocal social interactions involve extensive neural networks through the brain and autonomic nervous system that are dynamic and constantly changing during the lifespan of an individual. We also know that the properties of oxytocin are not predetermined or fixed. Oxytocin's cellular receptors are regulated by other hormones and epigenetic factors. These receptors change and adapt on the basis of life experiences. Both oxytocin and the experience of love change over time. In spite of limitations, new knowledge of the properties of oxytocin has proven useful in explaining several enigmatic features of love.

To dissect the anatomy and chemistry of love, scientists needed a biological equivalent of the Rosetta stone. Just as the actual stone helped linguists to decipher an archaic language by comparison to a known one, animal models are helping biologists draw parallels between ancient physiology and contemporary behaviours. Studies of socially monogamous mammals that form long-lasting social bonds, such as prairie voles, are helping scientists to understand the biology of human social behaviour.

The modern cortex struggles to interpret the primal messages of love, and weaves a narrative around incoming visceral experiences, potentially reacting to that narrative rather than reality

Research in voles indicates that, as in humans, oxytocin has a major role in social interactions and parental behaviour [ 5 , 6 , 8 ]. Of course, oxytocin does not act alone. Its release and actions depend on many other neurochemicals, including endogenous opioids and dopamine [ 9 ]. Particularly important to social bonding are the interactions between oxytocin and a related peptide, vasopressin. The systems regulated by oxytocin and vasopressin are sometimes redundant. Both peptides are implicated in behaviours that require social engagement by either males or females, such as huddling over an infant [ 5 ]. It was necessary in voles, for example, to block both oxytocin and vasopressin receptors to induce a significant reduction in social engagement either among adults or between adults and infants. Blocking only one of these two receptors did not eliminate social approach or contact. However, antagonists for either the oxytocin or vasopressin receptor inhibited the selective sociality, which is essential for the expression of a social bond [ 10 , 11 ]. If we accept selective social bonds, parenting and mate protection as proxies for love in humans, research in animals supports the hypothesis that oxytocin and vasopressin interact to allow the dynamic behavioural states and behaviours necessary for love.

Oxytocin and vasopressin have shared functions, but they are not identical in their actions. The specific behavioural roles of oxytocin and vasopressin are especially difficult to untangle because they are components of an integrated neural network with many points of intersection. Moreover, the genes that regulate the production of oxytocin and vasopressin are located on the same chromosome, possibly allowing a co-ordinated synthesis or release of these peptides. Both peptides can bind to, and have, antagonist or agonist effects on each other's receptors. Furthermore, the pathways necessary for reciprocal social behaviour are constantly adapting: these peptides and the systems that they regulate are always in flux.

In spite of these difficulties, some of the functions of oxytocin and vasopressin have been identified. Vasopressin is associated with physical and emotional mobilization, and supports vigilance and behaviours needed for guarding a partner or territory [ 6 ], as well as other forms of adaptive self-defence [ 12 ]. Vasopressin might also protect against ‘shutting down’ physiologically in the face of danger. In many mammalian species, mothers behave agonistically in defence of their young, possibly through the interactive actions of vasopressin and oxytocin [ 13 ]. Before mating, prairie voles are generally social, even towards strangers. However, within approximately one day of mating, they begin to show high levels of aggression towards intruders [ 14 ], possibly serving to protect or guard a mate, family or territory. This mating-induced aggression is especially obvious in males.

By contrast, oxytocin is associated with immobility without fear. This includes relaxed physiological states and postures that allow birth, lactation and consensual sexual behaviour. Although not essential for parenting, the increase of oxytocin associated with birth and lactation might make it easier for a woman to be less anxious around her newborn and to experience and express loving feelings for her child [ 15 ]. In highly social species such as prairie voles, and presumably in humans, the intricate molecular dances of oxytocin and vasopressin fine-tune the coexistence of care-taking and protective aggression.

The biology of fatherhood is less well studied. However, male care of offspring also seems to rely on both oxytocin and vasopressin [ 5 ]; even sexually naive male prairie voles show spontaneous parental behaviour in the presence of an infant [ 14 ]. However, the stimuli from infants or the nature of the social interactions that release oxytocin and vasopressin might differ between the sexes [ 4 ].

Parental care and support in a safe environment are particularly important for mental health in social mammals, including humans and prairie voles. Studies of rodents and lactating women suggest that oxytocin has the capacity to modulate the behavioural and autonomic distress that typically follows separation from a mother, child or partner, reducing defensive behaviours and thereby supporting growth and health [ 6 ].

During early life in particular, trauma or neglect might produce behaviours and emotional states in humans that are socially pathological. As the processes involved in creating social behaviours and social emotions are delicately balanced, they might be triggered in inappropriate contexts, leading to aggression towards friends or family. Alternatively, bonds might be formed with prospective partners who fail to provide social support or protection.

Males seem to be especially vulnerable to the negative effects of early experiences, possibly explaining their increased sensitivity to developmental disorders. Autism spectrum disorders, for example, defined in part by atypical social behaviours, are estimated to be three to ten times more common in males than females. The implication of sex differences in the nervous system, and in response to stressful experiences for social behaviour, is only slowly becoming apparent [ 8 ]. Both males and females produce vasopressin and oxytocin and are capable of responding to both hormones. However, in brain regions that are involved in defensive aggression, such as the extended amygdala and lateral septum, the production of vasopressin is androgen-dependent. Thus, in the face of a threat, males might experience higher central levels of vasopressin.

In highly social species […] the intricate molecular dances of oxytocin and vasopressin fine-tune the coexistence of care-taking and protective aggression

Oxytocin and vasopressin pathways, including the peptides and their receptors, are regulated by coordinated genetic, hormonal and epigenetic factors that influence the adaptive and behavioural functions of these peptides across the animal's lifespan. As a result, the endocrine and behavioural consequences of stress or a challenge might be different for males and females [ 16 ]. When unpaired prairie voles were exposed to an intense but brief stressor, such as a few minutes of swimming or injection of the adrenal hormone corticosterone, the males (but not females) quickly formed new pair bonds. These and other experiments suggest that males and females have different coping strategies, and possibly experience both stressful experiences and even love in ways that are gender-specific.

Love is an epigenetic phenomenon: social behaviours, emotional attachment to others and long-lasting reciprocal relationships are plastic and adaptive and so is the biology on which they are based. Because of this and the influence on parental behaviour and physiology, the impact of an early experience can pass to the next generation [ 17 ]. Infants of traumatized or highly stressed parents might be chronically exposed to vasopressin, either through their own increased production of the peptide, or through higher levels of vasopressin in maternal milk. Such increased exposure could sensitize the infant to defensive behaviours or create a life-long tendency to overreact to threat. On the basis of research in rats, it seems, that in response to adverse early experiences or chronic isolation, the genes for vasopressin receptors can become upregulated [ 18 ], leading to an increased sensitivity to acute stressors or anxiety that might persist throughout life.

…oxytocin exposure early in life not only regulates our ability to love and form social bonds, it also has an impact on our health and well-being

Epigenetic programming triggered by early life experiences is adaptive in allowing neuroendocrine systems to project and plan for future behavioural demands. However, epigenetic changes that are long-lasting can also create atypical social or emotional behaviours [ 17 ] that might be more likely to surface in later life, and in the face of social or emotional challenges. Exposure to exogenous hormones in early life might also be epigenetic. Prairie voles, for example, treated with vasopressin post-natally were more aggressive later in life, whereas those exposed to a vasopressin antagonist showed less aggression in adulthood. Conversely, the exposure of infants to slightly increased levels of oxytocin during development increased the tendency to show a pair bond in voles. However, these studies also showed that a single exposure to a higher level of oxytocin in early life could disrupt the later capacity to pair bond [ 8 ]. There is little doubt that either early social experiences or the effects of developmental exposure to these neuropeptides can potentially have long-lasting effects on behaviour. Both parental care and exposure to oxytocin in early life can permanently modify hormonal systems, altering the capacity to form relationships and influence the expression of love across the lifespan. Our preliminary findings in voles suggest further that early life experience affects the methylation of the oxytocin receptor gene and its expression [ 19 ]. Thus, we can plausibly argue that “love is epigenetic.”

Given the power of positive social experiences, it is not surprising that a lack of social relationships might also lead to alterations in behaviour and concurrently changes in oxytocin and vasopressin pathways. We have found that social isolation reduced the expression of the gene for the oxytocin receptor, and at the same time increased the expression of genes for the vasopressin peptide (H.P. Nazarloo and C.S. Carter, unpublished data). In female prairie voles, isolation was also accompanied by an increase in blood levels of oxytocin, possibly as a coping mechanism. However, over time, isolated prairie voles of both sexes showed increases in measures of depression, anxiety and physiological arousal, and these changes were seen even when endogenous oxytocin was elevated. Thus, even the hormonal insurance provided by endogenous oxytocin in the face of the chronic stress of isolation was not sufficient to dampen the consequences of living alone. Predictably, when isolated voles were given additional exogenous oxytocin this treatment restored many of these functions to normal [ 20 ].

On the basis of such encouraging findings, dozens of ongoing clinical trials are attempting to examine the therapeutic potential of oxytocin in disorders ranging from autism to heart disease (Clinicaltrials.gov). Of course, as in voles, the effects are likely to depend on the history of the individual and the context, and to be dose-dependent. With power comes responsibility, and the power of oxytocin needs to be respected.

Although research has only begun to examine the physiological effects of these peptides beyond social behaviour, there is a wealth of new evidence indicating that oxytocin influences physiological responses to stress and injury. Thus, oxytocin exposure early in life not only regulates our ability to love and form social bonds, it also has an impact on our health and well-being. Oxytocin modulates the hypothalamic–pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis, especially in response to disruptions in homeostasis [ 6 ], and coordinates demands on the immune system and energy balance. Long-term secure relationships provide emotional support and downregulate reactivity of the HPA axis, whereas intense stressors, including birth, trigger activation of the HPA axis and sympathetic nervous system. The ability of oxytocin to regulate these systems probably explains the exceptional capacity of most women to cope with the challenges of child-birth and child-rearing. The same molecules that allow us to give and receive love, also link our need for others with health and well-being.

The protective effects of positive sociality seem to rely on the same cocktail of hormones that carry a biological message of ‘love’ throughout the body

Of course, love is not without danger. The behaviours and strong emotions triggered by love might leave us vulnerable. Failed relationships can have devastating, even deadly, effects. In ‘modern’ societies humans can survive, at least after childhood, with little or no human contact. Communication technology, social media, electronic parenting and many other technological advances of the past century might place both children and adults at risk for social isolation and disorders of the autonomic nervous system, including deficits in their capacity for social engagement and love [ 21 ].

Social engagement actually helps us to cope with stress. The same hormones and areas of the brain that increase the capacity of the body to survive stress also enable us to better adapt to an ever-changing social and physical environment. Individuals with strong emotional support and relationships are more resilient in the face of stressors than those who feel isolated or lonely. Lesions in bodily tissues, including the brain, heal more quickly in animals that are living socially compared with those in isolation [ 22 ]. The protective effects of positive sociality seem to rely on the same cocktail of hormones that carry a biological message of ‘love’ throughout the body.

As only one example, the molecules associated with love have restorative properties, including the ability to literally heal a ‘broken heart’. Oxytocin receptors are expressed in the heart, and precursors for oxytocin seem to be crucial for the development of the fetal heart [ 23 ]. Oxytocin exerts protective and restorative effects in part through its capacity to convert undifferentiated stem cells into cardiomyocytes. Oxytocin can facilitate adult neurogenesis and tissue repair, especially after a stressful experience. We know that oxytocin has direct anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant properties in in vitro models of atherosclerosis [ 24 ]. The heart seems to rely on oxytocin as part of a normal process of protection and self-healing.

A life without love is not a life fully lived. Although research into mechanisms through which love protects us against stress and disease is in its infancy, this knowledge will ultimately increase our understanding of the way that our emotions have an impact on health and disease. We have much to learn about love and much to learn from love.

Acknowledgments

Discussions of ‘love and forgiveness’ with members of the Fetzer Institute's Advisory Council on Natural Sciences led to this essay and are gratefully acknowledged. We especially appreciate thoughtful editorial input from James Harris. Studies from the authors' laboratories were sponsored by the National Institutes of Health. We also express our gratitude for this support to our colleagues whose input and hard work informed the ideas expressed in this article.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Ingham CJ, Ben Jacob E (2008) Swarming and complex pattern formation in Paenicbachillus vortex studied by imaging and tracking cells . BMC Microbiol 8 : 36. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Woodward SH, Fischman BJ, Venkat A, Hudson ME, Varala K, Cameron SA, Clark AG, Robinson GE (2011) Genes involved in convergent evolution of eusociality in bees . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108 : 7472–7477 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Keverne EB (2006) Neurobiological and molecular approaches to attachment and bonding. In Attachment and Bonding: A New Synthesis (eds Carter CS, Ahnert L, Grossman KE, Hrdy SB, Lamb ME, Porges SW, Sachser N), pp 101–117. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: MIT Press [ Google Scholar ]

- Feldman R (2012) Oxytocin and social affiliation in humans . Horm Behav 61 : 380–391 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kenkel WM, Paredes J, Yee JR, Pournajafi-Nazarloo H, Bales KL, Carter CS (2012) Neuroendrocrine and behavioural responses to exposure to an infant in male prairie voles . J Neuroendocrinol 24 : 874–886 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carter CS (1998) Neuroendocrine perspectives on social attachment and love . Psychoneuroendocrinology 23 : 779–818 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Meyer-Lindenberg A, Domes G, Kirsch P, Heinrichs M (2011) Oxytocin and vasopressin in the human brain: social neuropeptides for translational medicine . Nat Rev Neurosci 12 : 524–538 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carter CS, Boone EM, Pournajafi-Nazarloo H, Bales KL (2009) Consequences of early experiences and exposure to oxytocin and vasopressin are sexually dimorphic . Dev Neurosci 31 : 332–341 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Aragona BJ, Wang Z (2009) Dopamine regulation of social choice in a monogamous rodent species . Front Behav Neurosci 3 : 15. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cho MM, DeVries AC, Williams JR, Carter CS (1999) The effects of oxytocin and vasopressin on partner preferences in male and female prairie voles ( Microtus ochrogaster ) . Behav Neurosci 113 : 1071–1080 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bales KL, Kim AJ, Lewis-Reese AD, Carter CS (2004) Both oxytocin and vasopressin may influence alloparental care in male prairie voles . Horm Behav 44 : 354–361 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ferris CF (2008) Functional magnetic resonance imaging and the neurobiology of vasopressin and oxytocin . Prog Brain Res 170 : 305–320 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bosch OJ, Neumann ID (2012) Both oxytocin and vasopressin are mediators of maternal care and aggression in rodents: from central release to sites of action . Horm Behav 61 : 293–303 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carter CS, DeVries AC, Getz LL (1995) Physiological substrates of mammalian monogamy: the prairie vole model . Neurosci Biobehav Rev 19 : 303–314 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carter CS, Altemus M (1997) Integrative functions of lactational hormones in social behaviour and stress management . Ann NY Acad Sci 807 : 164–174 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- DeVries AC, DeVries MB, Taymans SE, Carter CS (1996) The effects of stress on social preferences are sexually dimorphic in prairie voles . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93 : 11980–11984 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhang TY, Meaney MJ (2010) Epigenetics and the environmental regulation of the genome and its function . Annu Rev Psychol 61 : 439–466 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhang L, Hernandez VS, Liu B, Medina MP, Nava-Kopp AT, Irles C, Morales M (2012) Hypothalamic vasopressin system regulation by maternal separation: its impact on anxiety in rats . Neuroscience 215 : 135–148 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Connelly J, Kenkel W, Erickson E, Carter C (2011) Are birth and oxytocin epigenetic events? In Scientific Sessions Listings of Neuroscience 2011 , p 61. Washington, DC, USA: Society of Neuroscience; Abstract 388.10 [ Google Scholar ]

- Grippo AJ, Trahanas DM, Zimmerman RR 2nd, Porges SW, Carter CS (2009) Oxytocin protects against negative behavioral and autonomic consequences of long-term social isolation . Psychoneuroendocrinology 34 : 1542–1553 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Porges SW (2011) The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication and Self-regulation . New York, New York, USA: WW Norton [ Google Scholar ]

- Karelina K, DeVries AC (2011) Modeling social influences on human health . Psychosom Med 73 : 67–74 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Danalache BA, Gutkowska J, Slusarz MJ, Berezowska I, Jankowski M (2010) Oxytocin-Gly-Lys-Arg: a novel cardiomyogenic peptide . PLoS ONE 5 : e13643. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Szeto A, Nation DA, Mendez AJ, Dominguez-Bendala J, Brooks LG, Schneiderman N, McCabe PM (2008) Oxytocin attenuates NADPH-dependent superoxide activity and IL-6 secretion in macrophages and vascular cells . Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 295 : E1495–E1501 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

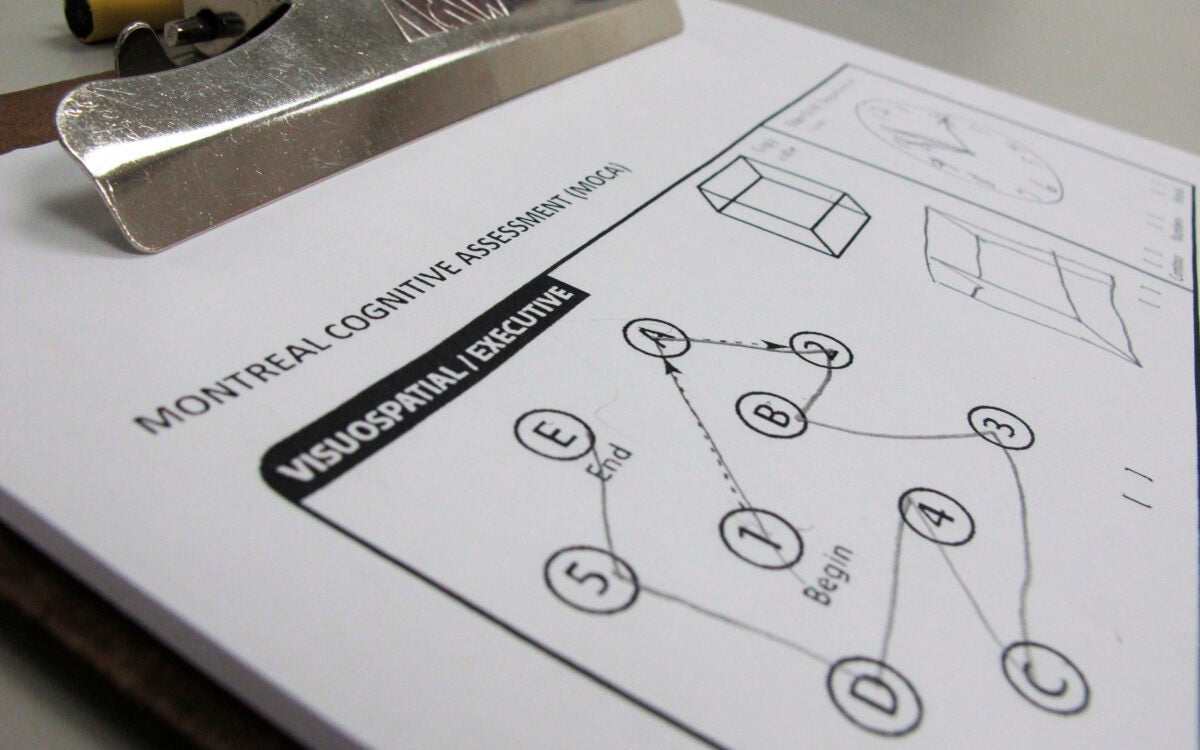

Testing fitness of aging brain

DNR orders for Down syndrome patients far exceeded pandemic norm

Researchers reverse hair loss caused by alopecia

When love and science double date.

Illustration by Sophie Blackall

Alvin Powell

Harvard Staff Writer

Sure, your heart thumps, but let’s look at what’s happening physically and psychologically

“They gave each other a smile with a future in it.” — Ring Lardner

Love’s warm squishiness seems a thing far removed from the cold, hard reality of science. Yet the two do meet, whether in lab tests for surging hormones or in austere chambers where MRI scanners noisily thunk and peer into brains that ignite at glimpses of their soulmates.

When it comes to thinking deeply about love, poets, philosophers, and even high school boys gazing dreamily at girls two rows over have a significant head start on science. But the field is gamely racing to catch up.

One database of scientific publications turns up more than 6,600 pages of results in a search for the word “love.” The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is conducting 18 clinical trials on it (though, like love itself, NIH’s “love” can have layered meanings, including as an acronym for a study of Crohn’s disease). Though not normally considered an intestinal ailment, love is often described as an illness, and the smitten as lovesick. Comedian George Burns once described love as something like a backache: “It doesn’t show up on X-rays, but you know it’s there.”

Richard Schwartz , associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School (HMS) and a consultant to McLean and Massachusetts General (MGH) hospitals, says it’s never been proven that love makes you physically sick, though it does raise levels of cortisol, a stress hormone that has been shown to suppress immune function.

Love also turns on the neurotransmitter dopamine, which is known to stimulate the brain’s pleasure centers. Couple that with a drop in levels of serotonin — which adds a dash of obsession — and you have the crazy, pleasing, stupefied, urgent love of infatuation.

It’s also true, Schwartz said, that like the moon — a trigger of its own legendary form of madness — love has its phases.

“It’s fairly complex, and we only know a little about it,” Schwartz said. “There are different phases and moods of love. The early phase of love is quite different” from later phases.

During the first love-year, serotonin levels gradually return to normal, and the “stupid” and “obsessive” aspects of the condition moderate. That period is followed by increases in the hormone oxytocin, a neurotransmitter associated with a calmer, more mature form of love. The oxytocin helps cement bonds, raise immune function, and begin to confer the health benefits found in married couples, who tend to live longer, have fewer strokes and heart attacks, be less depressed, and have higher survival rates from major surgery and cancer.

Schwartz has built a career around studying the love, hate, indifference, and other emotions that mark our complex relationships. And, though science is learning more in the lab than ever before, he said he still has learned far more counseling couples. His wife and sometime collaborator, Jacqueline Olds , also an associate professor of psychiatry at HMS and a consultant to McLean and MGH, agrees.

Spouses Richard Schwartz and Jacqueline Olds, both associate professors of psychiatry, have collaborated on a book about marriage.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

More knowledge, but struggling to understand

“I think we know a lot more scientifically about love and the brain than we did a couple of decades ago, but I don’t think it tells us very much that we didn’t already know about love,” Schwartz said. “It’s kind of interesting, it’s kind of fun [to study]. But do we think that makes us better at love, or helping people with love? Probably not much.”

Love and companionship have made indelible marks on Schwartz and Olds. Though they have separate careers, they’re separate together, working from discrete offices across the hall from each other in their stately Cambridge home. Each has a professional practice and independently trains psychiatry students, but they’ve also collaborated on two books about loneliness and one on marriage. Their own union has lasted 39 years, and they raised two children.

“I think we know a lot more scientifically about love and the brain than we did a couple of decades ago … But do we think that makes us better at love, or helping people with love? Probably not much.” Richard Schwartz, associate professor of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School

“I have learned much more from doing couples therapy, and being in a couple’s relationship” than from science, Olds said. “But every now and again, something like the fMRI or chemical studies can help you make the point better. If you say to somebody, ‘I think you’re doing this, and it’s terrible for a relationship,’ they may not pay attention. If you say, ‘It’s corrosive, and it’s causing your cortisol to go way up,’ then they really sit up and listen.”

A side benefit is that examining other couples’ trials and tribulations has helped their own relationship over the inevitable rocky bumps, Olds said.

“To some extent, being a psychiatrist allows you a privileged window into other people’s triumphs and mistakes,” Olds said. “And because you get to learn from them as they learn from you, when you work with somebody 10 years older than you, you learn what mistakes 10 years down the line might be.”

People have written for centuries about love shifting from passionate to companionate, something Schwartz called “both a good and a sad thing.” Different couples experience that shift differently. While the passion fades for some, others keep its flames burning, while still others are able to rekindle the fires.

“You have a tidal-like motion of closeness and drifting apart, closeness and drifting apart,” Olds said. “And you have to have one person have a ‘distance alarm’ to notice the drifting apart so there can be a reconnection … One could say that in the couples who are most successful at keeping their relationship alive over the years, there’s an element of companionate love and an element of passionate love. And those each get reawakened in that drifting back and forth, the ebb and flow of lasting relationships.”

Children as the biggest stressor

Children remain the biggest stressor on relationships, Olds said, adding that it seems a particular problem these days. Young parents feel pressure to raise kids perfectly, even at the risk of their own relationships. Kids are a constant presence for parents. The days when child care consisted of the instruction “Go play outside” while mom and dad reconnected over cocktails are largely gone.

When not hovering over children, America’s workaholic culture, coupled with technology’s 24/7 intrusiveness, can make it hard for partners to pay attention to each other in the evenings and even on weekends. It is a problem that Olds sees even in environments that ought to know better, such as psychiatry residency programs.

“There are all these sweet young doctors who are trying to have families while they’re in residency,” Olds said. “And the residencies work them so hard there’s barely time for their relationship or having children or taking care of children. So, we’re always trying to balance the fact that, in psychiatry, we stand for psychological good health, but [in] the residency we run, sometimes we don’t practice everything we preach.”

“There is too much pressure … on what a romantic partner should be. They should be your best friend, they should be your lover, they should be your closest relative, they should be your work partner, they should be the co-parent, your athletic partner. … Of course everybody isn’t able to quite live up to it.” Jacqueline Olds, associate professor of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School

All this busy-ness has affected non-romantic relationships too, which has a ripple effect on the romantic ones, Olds said. A respected national social survey has shown that in recent years people have gone from having three close friends to two, with one of those their romantic partner.

More like this

Strength in love, hope in science

Love in the crosshairs

Good genes are nice, but joy is better

“Often when you scratch the surface … the second [friend] lives 3,000 miles away, and you can’t talk to them on the phone because they’re on a different time schedule,” Olds said. “There is too much pressure, from my point of view, on what a romantic partner should be. They should be your best friend, they should be your lover, they should be your closest relative, they should be your work partner, they should be the co-parent, your athletic partner. There’s just so much pressure on the role of spouse that of course everybody isn’t able to quite live up to it.”

Since the rising challenges of modern life aren’t going to change soon, Schwartz and Olds said couples should try to adopt ways to fortify their relationships for life’s long haul. For instance, couples benefit from shared goals and activities, which will help pull them along a shared life path, Schwartz said.

“You’re not going to get to 40 years by gazing into each other’s eyes,” Schwartz said. “I think the fact that we’ve worked on things together has woven us together more, in good ways.”

Maintain curiosity about your partner

Also important is retaining a genuine sense of curiosity about your partner, fostered both by time apart to have separate experiences, and by time together, just as a couple, to share those experiences. Schwartz cited a study by Robert Waldinger, clinical professor of psychiatry at MGH and HMS, in which couples watched videos of themselves arguing. Afterwards, each person was asked what the partner was thinking. The longer they had been together, the worse they actually were at guessing, in part because they thought they already knew.

“What keeps love alive is being able to recognize that you don’t really know your partner perfectly and still being curious and still be exploring,” Schwartz said. “Which means, in addition to being sure you have enough time and involvement with each other — that that time isn’t stolen — making sure you have enough separateness that you can be an object of curiosity for the other person.”

Share this article

You might like.

Most voters back cognitive exams for older politicians. What do they measure?

Co-author sees need for additional research and earlier, deeper conversations around care

Treatment holds promise for painlessly targeting affected areas without weakening immune system

Finding right mix on campus speech policies

Legal, political scholars discuss balancing personal safety, constitutional rights, academic freedom amid roiling protests, cultural shifts

College sees strong yield for students accepted to Class of 2028

Financial aid was a critical factor, dean says

Harvard study, almost 80 years old, has proved that embracing community helps us live longer, and be happier

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.5: Biochemistry of Love

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 90544

- https://nobaproject.com/ via The Noba Project

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

By Sue Carter and Stephen Porges

University of North Carolina, Northeastern University - Boston

Love is deeply biological. It pervades every aspect of our lives and has inspired countless works of art. Love also has a profound effect on our mental and physical state. A “broken heart” or a failed relationship can have disastrous effects; bereavement disrupts human physiology and may even precipitate death. Without loving relationships, humans fail to flourish, even if all of their other basic needs are met. As such, love is clearly not “just” an emotion; it is a biological process that is both dynamic and bidirectional in several dimensions. Social interactions between individuals, for example, trigger cognitive and physiological processes that influence emotional and mental states. In turn, these changes influence future social interactions. Similarly, the maintenance of loving relationships requires constant feedback through sensory and cognitive systems; the body seeks love and responds constantly to interactions with loved ones or to the absence of such interactions. The evolutionary principles and ancient hormonal and neural systems that support the beneficial and healing effects of loving relationships are described here.

learning objectives

- Understand the role of Oxytocin in social behaviors.

- Articulate the functional differences between Vasopressin and Oxytocin.

- List sex differences in reaction to stress.

Introduction

Although evidence exists for the healing power of love, only recently has science turned its attention to providing a physiological explanation for love. The study of love in this context offers insight into many important topics, including the biological basis of interpersonal relationships and why and how disruptions in social bonds have such pervasive consequences for behavior and physiology. Some of the answers will be found in our growing knowledge of the neurobiological and endocrinological mechanisms of social behavior and interpersonal engagement.

The evolution of social behavior

Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution. Theodosius Dobzhansky’s famous dictum also holds true for explaining the evolution of love. Life on earth is fundamentally social: The ability to dynamically interact with other living organisms to support mutual homeostasis, growth, and reproduction evolved very early. Social interactions are present in primitive invertebrates and even among prokaryotes: Bacteria recognize and approach members of their own species. Bacteria also reproduce more successfully in the presence of their own kind and are able to form communities with physical and chemical characteristics that go far beyond the capabilities of the individual cell (Ingham & Ben-Jacob, 2008).

As another example, various insect species have evolved particularly complex social systems, known as eusociality. Characterized by a division of labor, eusociality appears to have evolved independently at least 11 times in insects. Research on honeybees indicates that a complex set of genes and their interactions regulate eusociality, and that these resulted from an “accelerated form of evolution” (Woodard et al., 2011). In other words, molecular mechanisms favoring high levels of sociality seem to be on an evolutionary fast track.

The evolutionary pathways that led from reptiles to mammals allowed the emergence of the unique anatomical systems and biochemical mechanisms that enable social engagement and selectively reciprocal sociality. Reptiles show minimal parental investment in offspring and form nonselective relationships between individuals. Pet owners may become emotionally attached to their turtle or snake, but this relationship is not reciprocal. In contrast, most mammals show intense parental investment in offspring and form lasting bonds with their children. Many mammalian species—including humans, wolves, and prairie voles—also develop long-lasting, reciprocal, and selective relationships between adults, with several features of what humans experience as “love.” In turn, these reciprocal interactions trigger dynamic feedback mechanisms that foster growth and health.

What is love? An evolutionary and physiological perspective

Human love is more complex than simple feedback mechanisms. Love may create its own reality. The biology of love originates in the primitive parts of the brain—the emotional core of the human nervous system—which evolved long before the cerebral cortex. The brain “in love” is flooded with vague sensations, often transmitted by the vagus nerve , and creating much of what we experience as emotion. The modern cortex struggles to interpret love’s primal messages, and weaves a narrative around incoming visceral experiences, potentially reacting to that narrative rather than to reality. It also is helpful to realize that mammalian social behavior is supported by biological components that were repurposed or co-opted over the course of mammalian evolution, eventually permitting lasting relationships between adults.

Is there a hormone of love and other relationships?

One element that repeatedly appears in the biochemistry of love is the neuropeptide oxytocin . In large mammals, oxytocin adopts a central role in reproduction by helping to expel the big-brained baby from the uterus, ejecting milk and sealing a selective and lasting bond between mother and offspring (Keverne, 2006). Mammalian offspring crucially depend on their mother’s milk for some time after birth. Human mothers also form a strong and lasting bond with their newborns immediately after birth, in a time period that is essential for the nourishment and survival of the baby. However, women who give birth by cesarean section without going through labor, or who opt not to breastfeed, are still able to form a strong emotional bond with their children. Furthermore, fathers, grandparents, and adoptive parents also form lifelong attachments to children. Preliminary evidence suggests that the simple presence of an infant can release oxytocin in adults as well (Feldman, 2012; Kenkel et al., 2012). The baby virtually forces us to love it.

The case for a major role for oxytocin in love is strong, but until recently was based largely on extrapolation from research on parental behavior (Feldman, 2012) or social behaviors in animals (Carter, 1998; Kenkel et al., 2012). However, recent human experiments have shown that intranasal delivery of oxytocin can facilitate social behaviors, including eye contact and social cognition (Meyer-Lindenberg, Domes, Kirsch, & Heinrichs, 2011)—behaviors that are at the heart of love.

Of course, oxytocin is not the molecular equivalent of love. Rather, it is just one important component of a complex neurochemical system that allows the body to adapt to highly emotional situations. The systems necessary for reciprocal social interactions involve extensive neural networks through the brain and autonomic nervous system that are dynamic and constantly changing across the life span of an individual. We also now know that the properties of oxytocin are not predetermined or fixed. Oxytocin’s cellular receptors are regulated by other hormones and epigenetic factors. These receptors change and adapt based on life experiences. Both oxytocin and the experience of love can change over time. In spite of limitations, new knowledge of the properties of oxytocin has proven useful in explaining several enigmatic features of love.

Stress and love

Emotional bonds can form during periods of extreme duress, especially when the survival of one individual depends on the presence and support of another. There also is evidence that oxytocin is released in response to acutely stressful experiences, perhaps serving as hormonal “insurance” against overwhelming stress. Oxytocin may help to ensure that parents and others will engage with and care for infants; develop stable, loving relationships; and seek out and receive support from others in times of need.

Animal models and the biology of social bonds

To dissect the anatomy and chemistry of love, scientists needed a biological equivalent of the Rosetta Stone. Just as the actual stone helped linguists decipher an archaic language by comparison to a known one, animal models are helping biologists draw parallels between ancient physiology and contemporary behaviors. Studies of socially monogamous mammals that form long-lasting social bonds, such as prairie voles, have been especially helpful to an understanding the biology of human social behavior.

There is more to love than oxytocin

Research in prairie voles showed that, as in humans, oxytocin plays a major role in social interactions and parental behavior (Carter, 1998; Carter, Boone, Pournajafi-Nazarloo, & Bales, 2009; Kenkel et al., 2012). Of course, oxytocin does not act alone. Its release and actions depend on many other neurochemicals, including endogenous opioids and dopamine (Aragona & Wang, 2009). Particularly important to social bonding are the interactions of oxytocin with a related neuropeptide known as vasopressin . The systems regulated by oxytocin and vasopressin are sometimes redundant. Both peptides are implicated in behaviors that require social engagement by either males or females, such as huddling over an infant (Kenkel et al., 2012). For example, it was necessary in voles to block both oxytocin and vasopressin receptors to induce a significant reduction in social engagement, either among adults or between adults and infants. Blocking only one of these two receptors did not eliminate social approach or contact. However, antagonists for either the oxytocin or vasopressin receptor inhibited the selective sociality, which is essential for the expression of a social bond (Bales, Kim, Lewis-Reese, & Carter, 2004; Cho, DeVries, Williams, & Carter, 1999). If we accept selective social bonds, parenting, and mate protection as proxies for love in humans, research in animals supports the hypothesis that oxytocin and vasopressin interact to allow the dynamic behavioral states and behaviors necessary for love.

Oxytocin and vasopressin have shared functions, but they are not identical in their actions. The specific behavioral roles of oxytocin and vasopressin are especially difficult to untangle because they are components of an integrated neural network with many points of intersection. Moreover, the genes that regulate the production of oxytocin and vasopressin are located on the same chromosome, possibly allowing coordinated synthesis or release of these peptides. Both peptides can bind to and have antagonist or agonist effects on each other’s receptors. Furthermore, the pathways necessary for reciprocal social behavior are constantly adapting: These peptides and the systems that they regulate are always in flux. In spite of these difficulties, some of the different functions of oxytocin and vasopressin have been identified.

Functional differences between vasopressin and oxytocin

Vasopressin is associated with physical and emotional mobilization, and can help support vigilance and behaviors needed for guarding a partner or territory (Carter, 1998), as well as other forms of adaptive self-defense (Ferris, 2008). Vasopressin also may protect against physiologically “shutting down” in the face of danger. In many mammalian species, mothers exhibit agonistic behaviors in defense of their young, possibly through the interactive actions of vasopressin and oxytocin (Bosch & Neumann, 2012). Prior to mating, prairie voles are generally social, even toward strangers. However, within a day or so of mating, they begin to show high levels of aggression toward intruders (Carter, DeVries, & Getz, 1995), possibly serving to protect or guard a mate, family, or territory. This mating-induced aggression is especially obvious in males.

Oxytocin, in contrast, is associated with immobility without fear. This includes relaxed physiological states and postures that permit birth, lactation, and consensual sexual behavior. Although not essential for parenting, the increase of oxytocin associated with birth and lactation may make it easier for a woman to be less anxious around her newborn and to experience and express loving feelings for her child (Carter & Altemus, 1997). In highly social species such as prairie voles (Kenkel et al., 2013), and presumably in humans, the intricate molecular dances of oxytocin and vasopressin fine-tune the coexistence of caretaking and protective aggression.

Fatherhood also has a biological basis

The biology of fatherhood is less well-studied than motherhood is. However, male care of offspring also appears to rely on both oxytocin and vasopressin (Kenkel et al., 2012), probably acting in part through effects on the autonomic nervous system (Kenkel et al., 2013). Even sexually naïve male prairie voles show spontaneous parental behavior in the presence of an infant (Carter et al., 1995). However, the stimuli from infants or the nature of the social interactions that release oxytocin and vasopressin may differ between the sexes (Feldman, 2012).

At the heart of the benefits of love is a sense of safety

Parental care and support in a safe environment are particularly important for mental health in social mammals, including humans and prairie voles. Studies of rodents and of lactating women suggest that oxytocin has the important capacity to modulate the behavioral and autonomic distress that typically follows separation from a mother, child, or partner, reducing defensive behaviors and thereby supporting growth and health (Carter, 1998).

The absence of love in early life can be detrimental to mental and physical health

During early life in particular, trauma or neglect may produce behaviors and emotional states in humans that are socially pathological. Because the processes involved in creating social behaviors and social emotions are delicately balanced, these be may be triggered in inappropriate contexts, leading to aggression toward friends or family. Alternatively, bonds may be formed with prospective partners who fail to provide social support or protection.

Sex differences exist in the consequences of early life experiences

Males seem to be especially vulnerable to the negative effects of early experiences, possibly helping to explain the increased sensitivity of males to various developmental disorders. The implications of sex differences in the nervous system and in the response to stressful experiences for social behavior are only slowly becoming apparent (Carter et al., 2009). Both males and females produce vasopressin and oxytocin and are capable of responding to both hormones. However, in brain regions that are involved in defensive aggression, such as the extended amygdala and lateral septum, the production of vasopressin is androgen-dependent. Thus, in the face of a threat, males may be experiencing higher central levels of vasopressin.

Oxytocin and vasopressin pathways, including the peptides and their receptors, are regulated by coordinated genetic, hormonal, and epigenetic factors that influence the adaptive and behavioral functions of these peptides across the animal’s life span. As a result, the endocrine and behavioral consequences of a stress or challenge may be different for males and females (DeVries, DeVries, Taymans, & Carter, 1996). For example, when unpaired prairie voles were exposed to an intense but brief stressor, such as a few minutes of swimming, or injection of the adrenal hormone corticosterone, the males (but not females) quickly formed new pair bonds. These and other experiments suggest that males and females have different coping strategies, and possibly may experience both stressful experiences, and even love, in ways that are gender-specific.

In the context of nature and evolution, sex differences in the nervous system are important. However, sex differences in brain and behavior also may help to explain gender differences in the vulnerability to mental and physical disorders (Taylor, et al., 2000). Better understanding these differences will provide clues to the physiology of human mental health in both sexes.

Loving relationships in early life can have epigenetic consequences

Love is “epigenetic.” That is, positive experiences in early life can act upon and alter the expression of specific genes. These changes in gene expression may have behavioral consequences through simple biochemical changes, such as adding a methyl group to a particular site within the genome (Zhang & Meaney, 2010). It is possible that these changes in the genome may even be passed to the next generation.

Social behaviors, emotional attachment to others, and long-lasting reciprocal relationships also are both plastic and adaptive, and so is the biology upon which they are based. For example, infants of traumatized or highly stressed parents might be chronically exposed to vasopressin, either through their own increased production of the peptide, or through higher levels of vasopressin in maternal milk. Such increased exposure could sensitize the infant to defensive behaviors or create a lifelong tendency to overreact to threat. Based on research in rats, it seems that in response to adverse early experiences of chronic isolation, the genes for vasopressin receptors can become upregulated (Zhang et al., 2012), leading to an increased sensitivity to acute stressors or anxiety that may persist throughout life.

Epigenetic programming triggered by early life experiences is adaptive in allowing neuroendocrine systems to project and plan for future behavioral demands. But epigenetic changes that are long-lasting also can create atypical social or emotional behaviors (Zhang & Meaney, 2010) that may be especially likely to surface in later life, and in the face of social or emotional challenges.

Exposure to exogenous hormones in early life also may be epigenetic. For example, prairie voles treated postnatally with vasopressin (especially males) were later more aggressive, whereas those exposed to a vasopressin antagonist showed less aggression in adulthood. Conversely, in voles the exposure of infants to slightly increased levels of oxytocin during development increased the tendency to show a pair bond. However, these studies also showed that a single exposure to a higher level of oxytocin in early life could disrupt the later capacity to pair bond (Carter et al., 2009).

There is little doubt that either early social experiences or the effects of developmental exposure to these neuropeptides holds the potential to have long-lasting effects on behavior. Both parental care and exposure to oxytocin in early life can permanently modify hormonal systems, altering the capacity to form relationships and influence the expression of love across the life span. Our preliminary findings in voles further suggest that early life experiences affect the methylation of the oxytocin receptor gene and its expression (Connelly, Kenkel, Erickson, & Carter, 2011). Thus, we can plausibly argue that love is epigenetic.

The absence of social behavior or isolation also has consequences for the oxytocin system

Given the power of positive social experiences, it is not surprising that a lack of social relationships also may lead to alterations in behavior as well as changes in oxytocin and vasopressin pathways. We have found that social isolation reduced the expression of the gene for the oxytocin receptor, and at the same time increased the expression of genes for the vasopressin peptide. In female prairie voles, isolation also was accompanied by an increase in blood levels of oxytocin, possibly as a coping mechanism. However, over time, isolated prairie voles of both sexes showed increases in measures of depression, anxiety, and physiological arousal, and these changes were observed even when endogenous oxytocin was elevated. Thus, even the hormonal insurance provided by endogenous oxytocin in face of the chronic stress of isolation was not sufficient to dampen the consequences of living alone. Predictably, when isolated voles were given additional exogenous oxytocin, this treatment did restore many of these functions to normal (Grippo, Trahanas, Zimmerman, Porges, & Carter, 2009).

In modern societies, humans can survive, at least after childhood, with little or no human contact. Communication technology, social media, electronic parenting, and many other recent technological advances may reduce social behaviors, placing both children and adults at risk for social isolation and disorders of the autonomic nervous system, including deficits in their capacity for social engagement and love (Porges, 2011).

Social engagement actually helps us to cope with stress. The same hormones and areas of the brain that increase the capacity of the body to survive stress also enable us to better adapt to an ever-changing social and physical environment. Individuals with strong emotional support and relationships are more resilient in the face of stressors than those who feel isolated or lonely. Lesions in various bodily tissues, including the brain, heal more quickly in animals that are living socially versus in isolation (Karelina & DeVries, 2011). The protective effects of positive sociality seem to rely on the same cocktail of hormones that carries a biological message of “love” throughout the body.

Can love—or perhaps oxytocin—be a medicine?

Although research has only begun to examine the physiological effects of these peptides beyond social behavior, there is a wealth of new evidence showing that oxytocin can influence physiological responses to stress and injury. As only one example, the molecules associated with love have restorative properties, including the ability to literally heal a “broken heart.” Oxytocin receptors are expressed in the heart, and precursors for oxytocin appear to be critical for the development of the fetal heart (Danalache, Gutkowska, Slusarz, Berezowska, & Jankowski, 2010). Oxytocin exerts protective and restorative effects in part through its capacity to convert undifferentiated stem cells into cardiomyocytes. Oxytocin can facilitate adult neurogenesis and tissue repair, especially after a stressful experience. We now know that oxytocin has direct anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties in in vitro models of atherosclerosis (Szeto et al., 2008). The heart seems to rely on oxytocin as part of a normal process of protection and self-healing.

Thus, oxytocin exposure early in life not only regulates our ability to love and form social bonds, it also affects our health and well-being. Oxytocin modulates the hypothalamic–pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis, especially in response to disruptions in homeostasis (Carter, 1998), and coordinates demands on the immune system and energy balance. Long-term, secure relationships provide emotional support and down-regulate reactivity of the HPA axis, whereas intense stressors, including birth, trigger activation of the HPA axis and sympathetic nervous system. The ability of oxytocin to regulate these systems probably explains the exceptional capacity of most women to cope with the challenges of childbirth and childrearing.

Dozens of ongoing clinical trials are currently attempting to examine the therapeutic potential of oxytocin in disorders ranging from autism to heart disease. Of course, as in hormonal studies in voles, the effects are likely to depend on the history of the individual and the context, and to be dose-dependent. As this research is emerging, a variety of individual differences and apparent discrepancies in the effects of exogenous oxytocin are being reported. Most of these studies do not include any information on the endogenous hormones, or on the oxytocin or vasopressin receptors, which are likely to affect the outcome of such treatments.

Research in this field is new and there is much left to understand. However, it is already clear that both love and oxytocin are powerful. Of course, with power comes responsibility. Although research into mechanisms through which love—or hormones such as oxytocin—may protect us against stress and disease is in its infancy, this knowledge will ultimately increase our understanding of the way that our emotions impact upon health and disease. The same molecules that allow us to give and receive love also link our need for others with health and well-being.

Acknowledgments

C. Sue Carter and Stephen W. Porges are both Professors of Psychiatry at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and also are Research Professors of Psychology at Northeastern University, Boston.

Discussions of “love and forgiveness” with members of the Fetzer Institute’s Advisory Committee on Natural Sciences led to this essay and are gratefully acknowledged here. We are especially appreciative of thoughtful editorial input from Dr. James Harris. Studies from the authors’ laboratories were sponsored by the National Institutes of Health. We also express our gratitude for this support and to our colleagues, whose input and hard work informed the ideas expressed in this article. A version of this paper was previously published in EMBO Reports in the series on “Sex and Society”; this paper is reproduced with the permission of the publishers of that journal.

Outside Resources

Discussion questions.

- If love is so important in human behavior, why is it so hard to describe and understand?

- Discuss the role of evolution in understanding what humans call “love” or other forms of prosociality.

- What are the common biological and neuroendocrine elements that appear in maternal love and adult-adult relationships?

- Oxytocin and vasopressin are biochemically similar. What are some of the differences between the actions of oxytocin and vasopressin?

- How may the properties of oxytocin and vasopressin help us understand the biological bases of love?

- What are common features of the biochemistry of “love” and “safety,” and why are these important to human health?

- Aragona, B. J, & Wang, Z. (2009). Dopamine regulation of social choice in a monogamous rodent species. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 3 , 15.

- Bales, K. L., Kim, A. J., Lewis-Reese, A. D., & Carter, C. S. (2004). Both oxytocin and vasopressin may influence alloparental care in male prairie voles. Hormones and Behavior, 44 , 454–361.

- Bosch, O. J., & Neumann, I. D. (2012). Both oxytocin and vasopressin are mediators of maternal care and aggression in rodents: from central release to sites of action. Hormones and Behavior, 61 , 293–303.

- Carter, C. S. (1998). Neuroendocrine perspectives on social attachment and love. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 23 , 779–818.

- Carter, C. S., & Altemus, M. (1997). Integrative functions of lactational hormones in social behavior and stress management. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, Integrative Neurobiology of Affiliation 807 , 164–174.

- Carter, C. S., Boone, E. M., Pournajafi-Nazarloo, H., & Bales, K. L. (2009). The consequences of early experiences and exposure to oxytocin and vasopressin are sexually-dimorphic. Developmental Neuroscience, 31 , 332–341.

- Carter, C. S., DeVries, A. C., & Getz, L. L. (1995). Physiological substrates of mammalian monogamy: The prairie vole model. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 19 , 303–314.

- Cho, M. M., DeVries, A. C., Williams, J. R., Carter, C. S. (1999). The effects of oxytocin and vasopressin on partner preferences in male and female prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster). Behavioral Neuroscience, 113 , 1071–1080.

- Connelly, J., Kenkel, W., Erickson, E., & Carter, C. S. (2011). Are birth and oxytocin epigenetic events. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts, 388 .10.

- Danalache, B. A., Gutkowska, J., Slusarz, M. J., Berezowska, I., & Jankowski, M. (2010). Oxytocin-Gly-Lys-Arg: A novel cardiomyogenic peptide. PloS One, 5 (10), e13643.

- DeVries, A. C., DeVries, M. B., Taymans, S. E., & Carter, C. S. (1996). Stress has sexually dimorphic effects on pair bonding in prairie voles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 93 , 11980–11984.

- Feldman, R. (2012). Oxytocin and social affiliation in humans. Hormones and Behavior, 61 , 380–391.

- Ferris, C. F. (2008). Functional magnetic resonance imaging and the neurobiology of vasopressin and oxytocin. Progress in Brain Research, 170 , 305–320.

- Grippo, A. J., Trahanas, D. M., Zimmerman, R. R., Porges, S. W., & Carter, C. S. (2009). Oxytocin protects against negative behavioral and autonomic consequences of long-term social isolation. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 34 , 1542–1553.

- Ingham, C. J., & Ben-Jacob, E. (2008). Swarming and complex pattern formation in Paenicbachillus vortex studied by imaging and tracking cells. BMC Microbiol , 8, 36.

- Karelina, K., & DeVries, A. C. (2011). Modeling social influences on human health. Psychosomatic Medicine, 73 , 67–74.

- Kenkel, W.M., Paredes, J., Lewis, G.F., Yee, J.R., Pournajafi-Nazarloo, H., Grippo, A.J., Porges, S.W., & Carter, C.S. (2013). Autonomic substrates of the response to pups in male prairie voles. PlosOne Aug 5;8(8):e69965. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069965.

- Kenkel, W.M., Paredes, J., Yee, J. R., Pournajafi-Nazarloo, H., Bales, K. L., & Carter, C. S. (2012). Exposure to an infant releases oxytocin and facilitates pair-bonding in male prairie voles. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 24 , 874–886.

- Keverne, E. B. (2006). Neurobiological and molecular approaches to attachment and bonding. In C. S. Carter, L. Ahnert et al. (Eds.), Attachment and bonding: A new synthesis . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Pp. 101-117.

- Meyer-Lindenberg, A., Domes, G., Kirsch, P., & Heinrichs, M. (2011). Oxytocin and vasopressin in the human brain: social neuropeptides for translational medicine. Nature: Reviews in Neuroscience 12 , 524–538.

- Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication and self-regulation . New York, NY: Norton.

- Szeto, A., Nation, D. A., Mendez, A. J., Dominguez-Bendala, J., Brooks, L. G., Schneiderman, N., & McCabe, P. M. (2008). Oxytocin attenuates NADPH-dependent superoxide activity and IL-6 secretion in macrophages and vascular cells. American Journal of Physiology, Endocrinology and Metabolism 295 , E1495–1501.

- Taylor, S. E., Klein, L. C., Lewis, B. P., Gruenewald, T. L., Gurung, R. A., & Updegraff, J. A. (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychol Rev, 107 , 411–429.

- Woodard, S. H., Fischman, B. J., Venkat, A., Hudson, M. E., Varala, K., Cameron S.A., . . . Robinson, G. E. (2011). Genes involved in convergent evolution of eusociality in bees. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 108 , 7472–7477.

- Zhang, L., Hernandez, V. S., Liu, B., Medina, M. P., Nava-Kopp, A. T., Irles, C., & Morales, M. (2012). Hypothalamic vasopressin system regulation by maternal separation: Its impact on anxiety in rats. Neuroscience, 215 , 135–148.

- Zhang, T. Y., & Meaney, M. J. (2010). Epigenetics and the environmental regulation of the genome and its function. Annual Review of Psychology, 61 , 439–466.

Chemistry of Love

8 Pages Posted: 28 May 2019

Wairagu Mbugua

Moi University

Date Written: April 29, 2019

Love is not simply a matter of feelings of the heart. Rather, it entails a series of chemicals produced by the body which are triggered by the action of the brain. These chemicals are released at different stages in the cycle of love from lust, attraction, and attachment. They play essential roles which ultimately result in a long-lasting relationship between two consenting partners.

Suggested Citation: Suggested Citation

Wairagu Mbugua (Contact Author)

Moi university ( email ).

PO Box 1948 Eldoret, RIFT VALLEY 30100 Kenya

Do you have a job opening that you would like to promote on SSRN?

Paper statistics, related ejournals, philosophy of mind ejournal.

Subscribe to this free journal for more curated articles on this topic

Psychological Anthropology eJournal

Subscribe to this fee journal for more curated articles on this topic

Social & Personality Psychology eJournal

Untitled (Portrait of a Man and a Woman) (1851), daguerreotype, United States. Courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago

Most Popular

13 days ago

Aithor Review

11 days ago

Now Everyone Can Be a Mathematician With The New Apple Math Notes App

How to write a dissertation proposal.

10 days ago

How To Write A Book Title In An Essay

Elon musk criticizes apple’s ai approach and threatens device ban, the chemistry of love essay sample, example.

According to Dr. Helen Fisher , an anthropologist at Rutgers University, love as a holistic system can be divided into three basic subsystems , each with its own functional tasks and roles: sex drive, romantic love, and attachment. Sex drive is necessary to make a person start looking for partners; romantic love appears to help a person hold focus on one specific partner; attachment is crucial for building a long-lasting and reliable relationship with a selected partner (Chemistry.com).

Each of these subsystems need a driving force to operate and impact an individual’s behavior. Even though a loving relationship is a lot about psychology, it is still fueled by hormones; this is why using the expression “love chemistry” is fully justified. For the sex drive subsystem, testosterone and estrogen are crucial; the romantic love stage, or attraction, is “driven” mostly by dopamine and serotonin; attachment is sustained by such hormones as oxytocin and vasopressin (BBC Science).