- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 14 December 2021

Bullying at school and mental health problems among adolescents: a repeated cross-sectional study

- Håkan Källmén 1 &

- Mats Hallgren ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0599-2403 2

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health volume 15 , Article number: 74 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

104k Accesses

13 Citations

37 Altmetric

Metrics details

To examine recent trends in bullying and mental health problems among adolescents and the association between them.

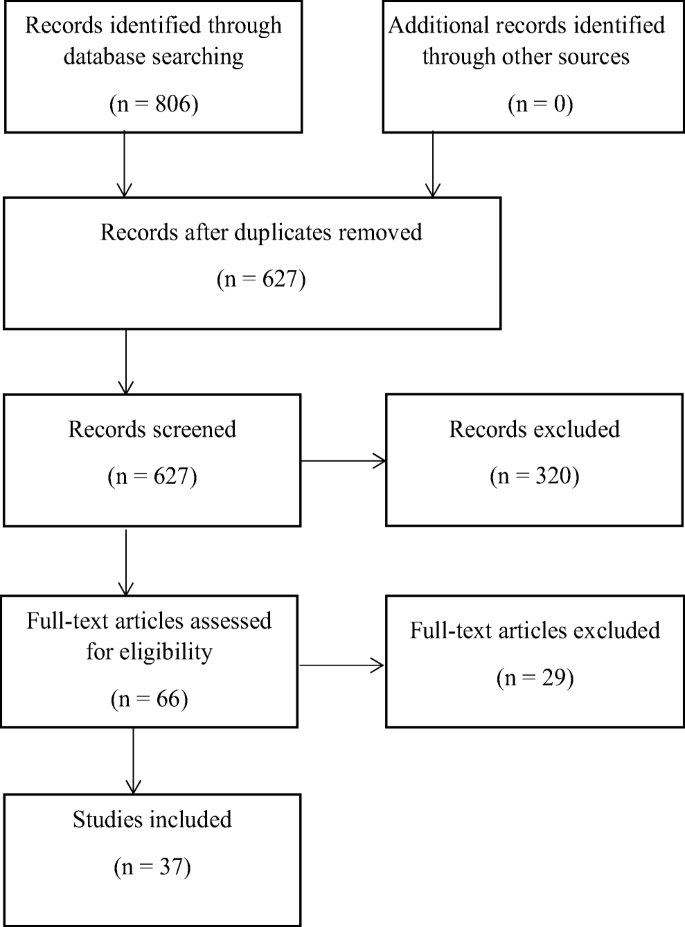

A questionnaire measuring mental health problems, bullying at school, socio-economic status, and the school environment was distributed to all secondary school students aged 15 (school-year 9) and 18 (school-year 11) in Stockholm during 2014, 2018, and 2020 (n = 32,722). Associations between bullying and mental health problems were assessed using logistic regression analyses adjusting for relevant demographic, socio-economic, and school-related factors.

The prevalence of bullying remained stable and was highest among girls in year 9; range = 4.9% to 16.9%. Mental health problems increased; range = + 1.2% (year 9 boys) to + 4.6% (year 11 girls) and were consistently higher among girls (17.2% in year 11, 2020). In adjusted models, having been bullied was detrimentally associated with mental health (OR = 2.57 [2.24–2.96]). Reports of mental health problems were four times higher among boys who had been bullied compared to those not bullied. The corresponding figure for girls was 2.4 times higher.

Conclusions

Exposure to bullying at school was associated with higher odds of mental health problems. Boys appear to be more vulnerable to the deleterious effects of bullying than girls.

Introduction

Bullying involves repeated hurtful actions between peers where an imbalance of power exists [ 1 ]. Arseneault et al. [ 2 ] conducted a review of the mental health consequences of bullying for children and adolescents and found that bullying is associated with severe symptoms of mental health problems, including self-harm and suicidality. Bullying was shown to have detrimental effects that persist into late adolescence and contribute independently to mental health problems. Updated reviews have presented evidence indicating that bullying is causative of mental illness in many adolescents [ 3 , 4 ].

There are indications that mental health problems are increasing among adolescents in some Nordic countries. Hagquist et al. [ 5 ] examined trends in mental health among Scandinavian adolescents (n = 116, 531) aged 11–15 years between 1993 and 2014. Mental health problems were operationalized as difficulty concentrating, sleep disorders, headache, stomach pain, feeling tense, sad and/or dizzy. The study revealed increasing rates of adolescent mental health problems in all four counties (Finland, Sweden, Norway, and Denmark), with Sweden experiencing the sharpest increase among older adolescents, particularly girls. Worsening adolescent mental health has also been reported in the United Kingdom. A study of 28,100 school-aged adolescents in England found that two out of five young people scored above thresholds for emotional problems, conduct problems or hyperactivity [ 6 ]. Female gender, deprivation, high needs status (educational/social), ethnic background, and older age were all associated with higher odds of experiencing mental health difficulties.

Bullying is shown to increase the risk of poor mental health and may partly explain these detrimental changes. Le et al. [ 7 ] reported an inverse association between bullying and mental health among 11–16-year-olds in Vietnam. They also found that poor mental health can make some children and adolescents more vulnerable to bullying at school. Bayer et al. [ 8 ] examined links between bullying at school and mental health among 8–9-year-old children in Australia. Those who experienced bullying more than once a week had poorer mental health than children who experienced bullying less frequently. Friendships moderated this association, such that children with more friends experienced fewer mental health problems (protective effect). Hysing et al. [ 9 ] investigated the association between experiences of bullying (as a victim or perpetrator) and mental health, sleep disorders, and school performance among 16–19 year olds from Norway (n = 10,200). Participants were categorized as victims, bullies, or bully-victims (that is, victims who also bullied others). All three categories were associated with worse mental health, school performance, and sleeping difficulties. Those who had been bullied also reported more emotional problems, while those who bullied others reported more conduct disorders [ 9 ].

As most adolescents spend a considerable amount of time at school, the school environment has been a major focus of mental health research [ 10 , 11 ]. In a recent review, Saminathen et al. [ 12 ] concluded that school is a potential protective factor against mental health problems, as it provides a socially supportive context and prepares students for higher education and employment. However, it may also be the primary setting for protracted bullying and stress [ 13 ]. Another factor associated with adolescent mental health is parental socio-economic status (SES) [ 14 ]. A systematic review indicated that lower parental SES is associated with poorer adolescent mental health [ 15 ]. However, no previous studies have examined whether SES modifies or attenuates the association between bullying and mental health. Similarly, it remains unclear whether school related factors, such as school grades and the school environment, influence the relationship between bullying and mental health. This information could help to identify those adolescents most at risk of harm from bullying.

To address these issues, we investigated the prevalence of bullying at school and mental health problems among Swedish adolescents aged 15–18 years between 2014 and 2020 using a population-based school survey. We also examined associations between bullying at school and mental health problems adjusting for relevant demographic, socioeconomic, and school-related factors. We hypothesized that: (1) bullying and adolescent mental health problems have increased over time; (2) There is an association between bullying victimization and mental health, so that mental health problems are more prevalent among those who have been victims of bullying; and (3) that school-related factors would attenuate the association between bullying and mental health.

Participants

The Stockholm school survey is completed every other year by students in lower secondary school (year 9—compulsory) and upper secondary school (year 11). The survey is mandatory for public schools, but voluntary for private schools. The purpose of the survey is to help inform decision making by local authorities that will ultimately improve students’ wellbeing. The questions relate to life circumstances, including SES, schoolwork, bullying, drug use, health, and crime. Non-completers are those who were absent from school when the survey was completed (< 5%). Response rates vary from year to year but are typically around 75%. For the current study data were available for 2014, 2018 and 2020. In 2014; 5235 boys and 5761 girls responded, in 2018; 5017 boys and 5211 girls responded, and in 2020; 5633 boys and 5865 girls responded (total n = 32,722). Data for the exposure variable, bullied at school, were missing for 4159 students, leaving 28,563 participants in the crude model. The fully adjusted model (described below) included 15,985 participants. The mean age in grade 9 was 15.3 years (SD = 0.51) and in grade 11, 17.3 years (SD = 0.61). As the data are completely anonymous, the study was exempt from ethical approval according to an earlier decision from the Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (2010-241 31-5). Details of the survey are available via a website [ 16 ], and are described in a previous paper [ 17 ].

Students completed the questionnaire during a school lesson, placed it in a sealed envelope and handed it to their teacher. Student were permitted the entire lesson (about 40 min) to complete the questionnaire and were informed that participation was voluntary (and that they were free to cancel their participation at any time without consequences). Students were also informed that the Origo Group was responsible for collection of the data on behalf of the City of Stockholm.

Study outcome

Mental health problems were assessed by using a modified version of the Psychosomatic Problem Scale [ 18 ] shown to be appropriate for children and adolescents and invariant across gender and years. The scale was later modified [ 19 ]. In the modified version, items about difficulty concentrating and feeling giddy were deleted and an item about ‘life being great to live’ was added. Seven different symptoms or problems, such as headaches, depression, feeling fear, stomach problems, difficulty sleeping, believing it’s great to live (coded negatively as seldom or rarely) and poor appetite were used. Students who responded (on a 5-point scale) that any of these problems typically occurs ‘at least once a week’ were considered as having indicators of a mental health problem. Cronbach alpha was 0.69 across the whole sample. Adding these problem areas, a total index was created from 0 to 7 mental health symptoms. Those who scored between 0 and 4 points on the total symptoms index were considered to have a low indication of mental health problems (coded as 0); those who scored between 5 and 7 symptoms were considered as likely having mental health problems (coded as 1).

Primary exposure

Experiences of bullying were measured by the following two questions: Have you felt bullied or harassed during the past school year? Have you been involved in bullying or harassing other students during this school year? Alternatives for the first question were: yes or no with several options describing how the bullying had taken place (if yes). Alternatives indicating emotional bullying were feelings of being mocked, ridiculed, socially excluded, or teased. Alternatives indicating physical bullying were being beaten, kicked, forced to do something against their will, robbed, or locked away somewhere. The response alternatives for the second question gave an estimation of how often the respondent had participated in bullying others (from once to several times a week). Combining the answers to these two questions, five different categories of bullying were identified: (1) never been bullied and never bully others; (2) victims of emotional (verbal) bullying who have never bullied others; (3) victims of physical bullying who have never bullied others; (4) victims of bullying who have also bullied others; and (5) perpetrators of bullying, but not victims. As the number of positive cases in the last three categories was low (range = 3–15 cases) bully categories 2–4 were combined into one primary exposure variable: ‘bullied at school’.

Assessment year was operationalized as the year when data was collected: 2014, 2018, and 2020. Age was operationalized as school grade 9 (15–16 years) or 11 (17–18 years). Gender was self-reported (boy or girl). The school situation To assess experiences of the school situation, students responded to 18 statements about well-being in school, participation in important school matters, perceptions of their teachers, and teaching quality. Responses were given on a four-point Likert scale ranging from ‘do not agree at all’ to ‘fully agree’. To reduce the 18-items down to their essential factors, we performed a principal axis factor analysis. Results showed that the 18 statements formed five factors which, according to the Kaiser criterion (eigen values > 1) explained 56% of the covariance in the student’s experience of the school situation. The five factors identified were: (1) Participation in school; (2) Interesting and meaningful work; (3) Feeling well at school; (4) Structured school lessons; and (5) Praise for achievements. For each factor, an index was created that was dichotomised (poor versus good circumstance) using the median-split and dummy coded with ‘good circumstance’ as reference. A description of the items included in each factor is available as Additional file 1 . Socio-economic status (SES) was assessed with three questions about the education level of the student’s mother and father (dichotomized as university degree versus not), and the amount of spending money the student typically received for entertainment each month (> SEK 1000 [approximately $120] versus less). Higher parental education and more spending money were used as reference categories. School grades in Swedish, English, and mathematics were measured separately on a 7-point scale and dichotomized as high (grades A, B, and C) versus low (grades D, E, and F). High school grades were used as the reference category.

Statistical analyses

The prevalence of mental health problems and bullying at school are presented using descriptive statistics, stratified by survey year (2014, 2018, 2020), gender, and school year (9 versus 11). As noted, we reduced the 18-item questionnaire assessing school function down to five essential factors by conducting a principal axis factor analysis (see Additional file 1 ). We then calculated the association between bullying at school (defined above) and mental health problems using multivariable logistic regression. Results are presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (Cis). To assess the contribution of SES and school-related factors to this association, three models are presented: Crude, Model 1 adjusted for demographic factors: age, gender, and assessment year; Model 2 adjusted for Model 1 plus SES (parental education and student spending money), and Model 3 adjusted for Model 2 plus school-related factors (school grades and the five factors identified in the principal factor analysis). These covariates were entered into the regression models in three blocks, where the final model represents the fully adjusted analyses. In all models, the category ‘not bullied at school’ was used as the reference. Pseudo R-square was calculated to estimate what proportion of the variance in mental health problems was explained by each model. Unlike the R-square statistic derived from linear regression, the Pseudo R-square statistic derived from logistic regression gives an indicator of the explained variance, as opposed to an exact estimate, and is considered informative in identifying the relative contribution of each model to the outcome [ 20 ]. All analyses were performed using SPSS v. 26.0.

Prevalence of bullying at school and mental health problems

Estimates of the prevalence of bullying at school and mental health problems across the 12 strata of data (3 years × 2 school grades × 2 genders) are shown in Table 1 . The prevalence of bullying at school increased minimally (< 1%) between 2014 and 2020, except among girls in grade 11 (2.5% increase). Mental health problems increased between 2014 and 2020 (range = 1.2% [boys in year 11] to 4.6% [girls in year 11]); were three to four times more prevalent among girls (range = 11.6% to 17.2%) compared to boys (range = 2.6% to 4.9%); and were more prevalent among older adolescents compared to younger adolescents (range = 1% to 3.1% higher). Pooling all data, reports of mental health problems were four times more prevalent among boys who had been victims of bullying compared to those who reported no experiences with bullying. The corresponding figure for girls was two and a half times as prevalent.

Associations between bullying at school and mental health problems

Table 2 shows the association between bullying at school and mental health problems after adjustment for relevant covariates. Demographic factors, including female gender (OR = 3.87; CI 3.48–4.29), older age (OR = 1.38, CI 1.26–1.50), and more recent assessment year (OR = 1.18, CI 1.13–1.25) were associated with higher odds of mental health problems. In Model 2, none of the included SES variables (parental education and student spending money) were associated with mental health problems. In Model 3 (fully adjusted), the following school-related factors were associated with higher odds of mental health problems: lower grades in Swedish (OR = 1.42, CI 1.22–1.67); uninteresting or meaningless schoolwork (OR = 2.44, CI 2.13–2.78); feeling unwell at school (OR = 1.64, CI 1.34–1.85); unstructured school lessons (OR = 1.31, CI = 1.16–1.47); and no praise for achievements (OR = 1.19, CI 1.06–1.34). After adjustment for all covariates, being bullied at school remained associated with higher odds of mental health problems (OR = 2.57; CI 2.24–2.96). Demographic and school-related factors explained 12% and 6% of the variance in mental health problems, respectively (Pseudo R-Square). The inclusion of socioeconomic factors did not alter the variance explained.

Our findings indicate that mental health problems increased among Swedish adolescents between 2014 and 2020, while the prevalence of bullying at school remained stable (< 1% increase), except among girls in year 11, where the prevalence increased by 2.5%. As previously reported [ 5 , 6 ], mental health problems were more common among girls and older adolescents. These findings align with previous studies showing that adolescents who are bullied at school are more likely to experience mental health problems compared to those who are not bullied [ 3 , 4 , 9 ]. This detrimental relationship was observed after adjustment for school-related factors shown to be associated with adolescent mental health [ 10 ].

A novel finding was that boys who had been bullied at school reported a four-times higher prevalence of mental health problems compared to non-bullied boys. The corresponding figure for girls was 2.5 times higher for those who were bullied compared to non-bullied girls, which could indicate that boys are more vulnerable to the deleterious effects of bullying than girls. Alternatively, it may indicate that boys are (on average) bullied more frequently or more intensely than girls, leading to worse mental health. Social support could also play a role; adolescent girls often have stronger social networks than boys and could be more inclined to voice concerns about bullying to significant others, who in turn may offer supports which are protective [ 21 ]. Related studies partly confirm this speculative explanation. An Estonian study involving 2048 children and adolescents aged 10–16 years found that, compared to girls, boys who had been bullied were more likely to report severe distress, measured by poor mental health and feelings of hopelessness [ 22 ].

Other studies suggest that heritable traits, such as the tendency to internalize problems and having low self-esteem are associated with being a bully-victim [ 23 ]. Genetics are understood to explain a large proportion of bullying-related behaviors among adolescents. A study from the Netherlands involving 8215 primary school children found that genetics explained approximately 65% of the risk of being a bully-victim [ 24 ]. This proportion was similar for boys and girls. Higher than average body mass index (BMI) is another recognized risk factor [ 25 ]. A recent Australian trial involving 13 schools and 1087 students (mean age = 13 years) targeted adolescents with high-risk personality traits (hopelessness, anxiety sensitivity, impulsivity, sensation seeking) to reduce bullying at school; both as victims and perpetrators [ 26 ]. There was no significant intervention effect for bullying victimization or perpetration in the total sample. In a secondary analysis, compared to the control schools, intervention school students showed greater reductions in victimization, suicidal ideation, and emotional symptoms. These findings potentially support targeting high-risk personality traits in bullying prevention [ 26 ].

The relative stability of bullying at school between 2014 and 2020 suggests that other factors may better explain the increase in mental health problems seen here. Many factors could be contributing to these changes, including the increasingly competitive labour market, higher demands for education, and the rapid expansion of social media [ 19 , 27 , 28 ]. A recent Swedish study involving 29,199 students aged between 11 and 16 years found that the effects of school stress on psychosomatic symptoms have become stronger over time (1993–2017) and have increased more among girls than among boys [ 10 ]. Research is needed examining possible gender differences in perceived school stress and how these differences moderate associations between bullying and mental health.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the current study include the large participant sample from diverse schools; public and private, theoretical and practical orientations. The survey included items measuring diverse aspects of the school environment; factors previously linked to adolescent mental health but rarely included as covariates in studies of bullying and mental health. Some limitations are also acknowledged. These data are cross-sectional which means that the direction of the associations cannot be determined. Moreover, all the variables measured were self-reported. Previous studies indicate that students tend to under-report bullying and mental health problems [ 29 ]; thus, our results may underestimate the prevalence of these behaviors.

In conclusion, consistent with our stated hypotheses, we observed an increase in self-reported mental health problems among Swedish adolescents, and a detrimental association between bullying at school and mental health problems. Although bullying at school does not appear to be the primary explanation for these changes, bullying was detrimentally associated with mental health after adjustment for relevant demographic, socio-economic, and school-related factors, confirming our third hypothesis. The finding that boys are potentially more vulnerable than girls to the deleterious effects of bullying should be replicated in future studies, and the mechanisms investigated. Future studies should examine the longitudinal association between bullying and mental health, including which factors mediate/moderate this relationship. Epigenetic studies are also required to better understand the complex interaction between environmental and biological risk factors for adolescent mental health [ 24 ].

Availability of data and materials

Data requests will be considered on a case-by-case basis; please email the corresponding author.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Olweus D. School bullying: development and some important challenges. Ann Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9(9):751–80. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185516 .

Article Google Scholar

Arseneault L, Bowes L, Shakoor S. Bullying victimization in youths and mental health problems: “Much ado about nothing”? Psychol Med. 2010;40(5):717–29. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291709991383 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Arseneault L. The long-term impact of bullying victimization on mental health. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):27–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20399 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Moore SE, Norman RE, Suetani S, Thomas HJ, Sly PD, Scott JG. Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Psychiatry. 2017;7(1):60–76. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v7.i1.60 .

Hagquist C, Due P, Torsheim T, Valimaa R. Cross-country comparisons of trends in adolescent psychosomatic symptoms—a Rasch analysis of HBSC data from four Nordic countries. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17(1):27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-019-1097-x .

Deighton J, Lereya ST, Casey P, Patalay P, Humphrey N, Wolpert M. Prevalence of mental health problems in schools: poverty and other risk factors among 28 000 adolescents in England. Br J Psychiatry. 2019;215(3):565–7. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.19 .

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Le HTH, Tran N, Campbell MA, Gatton ML, Nguyen HT, Dunne MP. Mental health problems both precede and follow bullying among adolescents and the effects differ by gender: a cross-lagged panel analysis of school-based longitudinal data in Vietnam. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-019-0291-x .

Bayer JK, Mundy L, Stokes I, Hearps S, Allen N, Patton G. Bullying, mental health and friendship in Australian primary school children. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2018;23(4):334–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12261 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Hysing M, Askeland KG, La Greca AM, Solberg ME, Breivik K, Sivertsen B. Bullying involvement in adolescence: implications for sleep, mental health, and academic outcomes. J Interpers Violence. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519853409 .

Hogberg B, Strandh M, Hagquist C. Gender and secular trends in adolescent mental health over 24 years—the role of school-related stress. Soc Sci Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112890 .

Kidger J, Araya R, Donovan J, Gunnell D. The effect of the school environment on the emotional health of adolescents: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2012;129(5):925–49. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2248 .

Saminathen MG, Låftman SB, Modin B. En fungerande skola för alla: skolmiljön som skyddsfaktor för ungas psykiska välbefinnande. [A functioning school for all: the school environment as a protective factor for young people’s mental well-being]. Socialmedicinsk tidskrift [Soc Med]. 2020;97(5–6):804–16.

Google Scholar

Bibou-Nakou I, Tsiantis J, Assimopoulos H, Chatzilambou P, Giannakopoulou D. School factors related to bullying: a qualitative study of early adolescent students. Soc Psychol Educ. 2012;15(2):125–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-012-9179-1 .

Vukojevic M, Zovko A, Talic I, Tanovic M, Resic B, Vrdoljak I, Splavski B. Parental socioeconomic status as a predictor of physical and mental health outcomes in children—literature review. Acta Clin Croat. 2017;56(4):742–8. https://doi.org/10.20471/acc.2017.56.04.23 .

Reiss F. Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2013;90:24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.026 .

Stockholm City. Stockholmsenkät (The Stockholm Student Survey). 2021. https://start.stockholm/aktuellt/nyheter/2020/09/presstraff-stockholmsenkaten-2020/ . Accessed 19 Nov 2021.

Zeebari Z, Lundin A, Dickman PW, Hallgren M. Are changes in alcohol consumption among swedish youth really occurring “in concert”? A new perspective using quantile regression. Alc Alcohol. 2017;52(4):487–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agx020 .

Hagquist C. Psychometric properties of the PsychoSomatic Problems Scale: a Rasch analysis on adolescent data. Social Indicat Res. 2008;86(3):511–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9186-3 .

Hagquist C. Ungas psykiska hälsa i Sverige–komplexa trender och stora kunskapsluckor [Young people’s mental health in Sweden—complex trends and large knowledge gaps]. Socialmedicinsk tidskrift [Soc Med]. 2013;90(5):671–83.

Wu W, West SG. Detecting misspecification in mean structures for growth curve models: performance of pseudo R(2)s and concordance correlation coefficients. Struct Equ Model. 2013;20(3):455–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2013.797829 .

Holt MK, Espelage DL. Perceived social support among bullies, victims, and bully-victims. J Youth Adolscence. 2007;36(8):984–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9153-3 .

Mark L, Varnik A, Sisask M. Who suffers most from being involved in bullying-bully, victim, or bully-victim? J Sch Health. 2019;89(2):136–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12720 .

Tsaousis I. The relationship of self-esteem to bullying perpetration and peer victimization among schoolchildren and adolescents: a meta-analytic review. Aggress Violent Behav. 2016;31:186–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2016.09.005 .

Veldkamp SAM, Boomsma DI, de Zeeuw EL, van Beijsterveldt CEM, Bartels M, Dolan CV, van Bergen E. Genetic and environmental influences on different forms of bullying perpetration, bullying victimization, and their co-occurrence. Behav Genet. 2019;49(5):432–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-019-09968-5 .

Janssen I, Craig WM, Boyce WF, Pickett W. Associations between overweight and obesity with bullying behaviors in school-aged children. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5):1187–94. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.113.5.1187 .

Kelly EV, Newton NC, Stapinski LA, Conrod PJ, Barrett EL, Champion KE, Teesson M. A novel approach to tackling bullying in schools: personality-targeted intervention for adolescent victims and bullies in Australia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(4):508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2019.04.010 .

Gunnell D, Kidger J, Elvidge H. Adolescent mental health in crisis. BMJ. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2608 .

O’Reilly M, Dogra N, Whiteman N, Hughes J, Eruyar S, Reilly P. Is social media bad for mental health and wellbeing? Exploring the perspectives of adolescents. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;23:601–13.

Unnever JD, Cornell DG. Middle school victims of bullying: who reports being bullied? Aggr Behav. 2004;30(5):373–88. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20030 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Authors are grateful to the Department for Social Affairs, Stockholm, for permission to use data from the Stockholm School Survey.

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute. None to declare.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Stockholm Prevents Alcohol and Drug Problems (STAD), Center for Addiction Research and Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Solna, Sweden

Håkan Källmén

Epidemiology of Psychiatric Conditions, Substance Use and Social Environment (EPiCSS), Department of Global Public Health, Karolinska Institutet, Level 6, Solnavägen 1e, Solna, Sweden

Mats Hallgren

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

HK conceived the study and analyzed the data (with input from MH). HK and MH interpreted the data and jointly wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mats Hallgren .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

As the data are completely anonymous, the study was exempt from ethical approval according to an earlier decision from the Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (2010-241 31-5).

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1..

Principal factor analysis description.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Källmén, H., Hallgren, M. Bullying at school and mental health problems among adolescents: a repeated cross-sectional study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 15 , 74 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-021-00425-y

Download citation

Received : 05 October 2021

Accepted : 23 November 2021

Published : 14 December 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-021-00425-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mental health

- Adolescents

- School-related factors

- Gender differences

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health

ISSN: 1753-2000

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

Preventing Bullying Through Science, Policy, and Practice (2016)

Chapter: 1 introduction, 1 introduction.

Bullying, long tolerated by many as a rite of passage into adulthood, is now recognized as a major and preventable public health problem, one that can have long-lasting consequences ( McDougall and Vaillancourt, 2015 ; Wolke and Lereya, 2015 ). Those consequences—for those who are bullied, for the perpetrators of bullying, and for witnesses who are present during a bullying event—include poor school performance, anxiety, depression, and future delinquent and aggressive behavior. Federal, state, and local governments have responded by adopting laws and implementing programs to prevent bullying and deal with its consequences. However, many of these responses have been undertaken with little attention to what is known about bullying and its effects. Even the definition of bullying varies among both researchers and lawmakers, though it generally includes physical and verbal behavior, behavior leading to social isolation, and behavior that uses digital communications technology (cyberbullying). This report adopts the term “bullying behavior,” which is frequently used in the research field, to cover all of these behaviors.

Bullying behavior is evident as early as preschool, although it peaks during the middle school years ( Currie et al., 2012 ; Vaillancourt et al., 2010 ). It can occur in diverse social settings, including classrooms, school gyms and cafeterias, on school buses, and online. Bullying behavior affects not only the children and youth who are bullied, who bully, and who are both bullied and bully others but also bystanders to bullying incidents. Given the myriad situations in which bullying can occur and the many people who may be involved, identifying effective prevention programs and policies is challenging, and it is unlikely that any one approach will be ap-

propriate in all situations. Commonly used bullying prevention approaches include policies regarding acceptable behavior in schools and behavioral interventions to promote positive cultural norms.

STUDY CHARGE

Recognizing that bullying behavior is a major public health problem that demands the concerted and coordinated time and attention of parents, educators and school administrators, health care providers, policy makers, families, and others concerned with the care of children, a group of federal agencies and private foundations asked the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to undertake a study of what is known and what needs to be known to further the field of preventing bullying behavior. The Committee on the Biological and Psychosocial Effects of Peer Victimization:

Lessons for Bullying Prevention was created to carry out this task under the Academies’ Board on Children, Youth, and Families and the Committee on Law and Justice. The study received financial support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the Health Resources and Services Administration, the Highmark Foundation, the National Institute of Justice, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Semi J. and Ruth W. Begun Foundation, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The full statement of task for the committee is presented in Box 1-1 .

Although the committee acknowledges the importance of this topic as it pertains to all children in the United States and in U.S. territories, this report focuses on the 50 states and the District of Columbia. Also, while the committee acknowledges that bullying behavior occurs in the school

environment for youth in foster care, in juvenile justice facilities, and in other residential treatment facilities, this report does not address bullying behavior in those environments because it is beyond the study charge.

CONTEXT FOR THE STUDY

This section of the report highlights relevant work in the field and, later in the chapter under “The Committee’s Approach,” presents the conceptual framework and corresponding definitions of terms that the committee has adopted.

Historical Context

Bullying behavior was first characterized in the scientific literature as part of the childhood experience more than 100 years ago in “Teasing and Bullying,” published in the Pedagogical Seminary ( Burk, 1897 ). The author described bullying behavior, attempted to delineate causes and cures for the tormenting of others, and called for additional research ( Koo, 2007 ). Nearly a century later, Dan Olweus, a Swedish research professor of psychology in Norway, conducted an intensive study on bullying ( Olweus, 1978 ). The efforts of Olweus brought awareness to the issue and motivated other professionals to conduct their own research, thereby expanding and contributing to knowledge of bullying behavior. Since Olweus’s early work, research on bullying has steadily increased (see Farrington and Ttofi, 2009 ; Hymel and Swearer, 2015 ).

Over the past few decades, venues where bullying behavior occurs have expanded with the advent of the Internet, chat rooms, instant messaging, social media, and other forms of digital electronic communication. These modes of communication have provided a new communal avenue for bullying. While the media reports linking bullying to suicide suggest a causal relationship, the available research suggests that there are often multiple factors that contribute to a youth’s suicide-related ideology and behavior. Several studies, however, have demonstrated an association between bullying involvement and suicide-related ideology and behavior (see, e.g., Holt et al., 2015 ; Kim and Leventhal, 2008 ; Sourander, 2010 ; van Geel et al., 2014 ).

In 2013, the Health Resources and Services Administration of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services requested that the Institute of Medicine 1 and the National Research Council convene an ad hoc planning committee to plan and conduct a 2-day public workshop to highlight relevant information and knowledge that could inform a multidisciplinary

___________________

1 Prior to 2015, the National Academy of Medicine was known as the Institute of Medicine.

road map on next steps for the field of bullying prevention. Content areas that were explored during the April 2014 workshop included the identification of conceptual models and interventions that have proven effective in decreasing bullying and the antecedents to bullying while increasing protective factors that mitigate the negative health impact of bullying. The discussions highlighted the need for a better understanding of the effectiveness of program interventions in realistic settings; the importance of understanding what works for whom and under what circumstances, as well as the influence of different mediators (i.e., what accounts for associations between variables) and moderators (i.e., what affects the direction or strength of associations between variables) in bullying prevention efforts; and the need for coordination among agencies to prevent and respond to bullying. The workshop summary ( Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2014c ) informs this committee’s work.

Federal Efforts to Address Bullying and Related Topics

Currently, there is no comprehensive federal statute that explicitly prohibits bullying among children and adolescents, including cyberbullying. However, in the wake of the growing concerns surrounding the implications of bullying, several federal initiatives do address bullying among children and adolescents, and although some of them do not primarily focus on bullying, they permit some funds to be used for bullying prevention purposes.

The earliest federal initiative was in 1999, when three agencies collaborated to establish the Safe Schools/Healthy Students initiative in response to a series of deadly school shootings in the late 1990s. The program is administered by the U.S. Departments of Education, Health and Human Services, and Justice to prevent youth violence and promote the healthy development of youth. It is jointly funded by the Department of Education and by the Department of Health and Human Services’ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The program has provided grantees with both the opportunity to benefit from collaboration and the tools to sustain it through deliberate planning, more cost-effective service delivery, and a broader funding base ( Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015 ).

The next major effort was in 2010, when the Department of Education awarded $38.8 million in grants under the Safe and Supportive Schools (S3) Program to 11 states to support statewide measurement of conditions for learning and targeted programmatic interventions to improve conditions for learning, in order to help schools improve safety and reduce substance use. The S3 Program was administered by the Safe and Supportive Schools Group, which also administered the Safe and Drug-Free Schools and Communities Act State and Local Grants Program, authorized by the

1994 Elementary and Secondary Education Act. 2 It was one of several programs related to developing and maintaining safe, disciplined, and drug-free schools. In addition to the S3 grants program, the group administered a number of interagency agreements with a focus on (but not limited to) bullying, school recovery research, data collection, and drug and violence prevention activities ( U.S. Department of Education, 2015 ).

A collaborative effort among the U.S. Departments of Agriculture, Defense, Education, Health and Human Services, Interior, and Justice; the Federal Trade Commission; and the White House Initiative on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders created the Federal Partners in Bullying Prevention (FPBP) Steering Committee. Led by the U.S. Department of Education, the FPBP works to coordinate policy, research, and communications on bullying topics. The FPBP Website provides extensive resources on bullying behavior, including information on what bullying is, its risk factors, its warning signs, and its effects. 3 The FPBP Steering Committee also plans to provide details on how to get help for those who have been bullied. It also was involved in creating the “Be More than a Bystander” Public Service Announcement campaign with the Ad Council to engage students in bullying prevention. To improve school climate and reduce rates of bullying nationwide, FPBP has sponsored four bullying prevention summits attended by education practitioners, policy makers, researchers, and federal officials.

In 2014, the National Institute of Justice—the scientific research arm of the U.S. Department of Justice—launched the Comprehensive School Safety Initiative with a congressional appropriation of $75 million. The funds are to be used for rigorous research to produce practical knowledge that can improve the safety of schools and students, including bullying prevention. The initiative is carried out through partnerships among researchers, educators, and other stakeholders, including law enforcement, behavioral and mental health professionals, courts, and other justice system professionals ( National Institute of Justice, 2015 ).

In 2015, the Every Student Succeeds Act was signed by President Obama, reauthorizing the 50-year-old Elementary and Secondary Education Act, which is committed to providing equal opportunities for all students. Although bullying is neither defined nor prohibited in this act, it is explicitly mentioned in regard to applicability of safe school funding, which it had not been in previous iterations of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act.

The above are examples of federal initiatives aimed at promoting the

2 The Safe and Drug-Free Schools and Communities Act was included as Title IV, Part A, of the 1994 Elementary and Secondary Education Act. See http://www.ojjdp.gov/pubs/gun_violence/sect08-i.html [October 2015].

3 For details, see http://www.stopbullying.gov/ [October 2015].

healthy development of youth, improving the safety of schools and students, and reducing rates of bullying behavior. There are several other federal initiatives that address student bullying directly or allow funds to be used for bullying prevention activities.

Definitional Context

The terms “bullying,” “harassment,” and “peer victimization” have been used in the scientific literature to refer to behavior that is aggressive, is carried out repeatedly and over time, and occurs in an interpersonal relationship where a power imbalance exists ( Eisenberg and Aalsma, 2005 ). Although some of these terms have been used interchangeably in the literature, peer victimization is targeted aggressive behavior of one child against another that causes physical, emotional, social, or psychological harm. While conflict and bullying among siblings are important in their own right ( Tanrikulu and Campbell, 2015 ), this area falls outside of the scope of the committee’s charge. Sibling conflict and aggression falls under the broader concept of interpersonal aggression, which includes dating violence, sexual assault, and sibling violence, in addition to bullying as defined for this report. Olweus (1993) noted that bullying, unlike other forms of peer victimization where the children involved are equally matched, involves a power imbalance between the perpetrator and the target, where the target has difficulty defending him or herself and feels helpless against the aggressor. This power imbalance is typically considered a defining feature of bullying, which distinguishes this particular form of aggression from other forms, and is typically repeated in multiple bullying incidents involving the same individuals over time ( Olweus, 1993 ).

Bullying and violence are subcategories of aggressive behavior that overlap ( Olweus, 1996 ). There are situations in which violence is used in the context of bullying. However, not all forms of bullying (e.g., rumor spreading) involve violent behavior. The committee also acknowledges that perspective about intentions can matter and that in many situations, there may be at least two plausible perceptions involved in the bullying behavior.

A number of factors may influence one’s perception of the term “bullying” ( Smith and Monks, 2008 ). Children and adolescents’ understanding of the term “bullying” may be subject to cultural interpretations or translations of the term ( Hopkins et al., 2013 ). Studies have also shown that influences on children’s understanding of bullying include the child’s experiences as he or she matures and whether the child witnesses the bullying behavior of others ( Hellström et al., 2015 ; Monks and Smith, 2006 ; Smith and Monks, 2008 ).

In 2010, the FPBP Steering Committee convened its first summit, which brought together more than 150 nonprofit and corporate leaders,

researchers, practitioners, parents, and youths to identify challenges in bullying prevention. Discussions at the summit revealed inconsistencies in the definition of bullying behavior and the need to create a uniform definition of bullying. Subsequently, a review of the 2011 CDC publication of assessment tools used to measure bullying among youth ( Hamburger et al., 2011 ) revealed inconsistent definitions of bullying and diverse measurement strategies. Those inconsistencies and diverse measurements make it difficult to compare the prevalence of bullying across studies ( Vivolo et al., 2011 ) and complicate the task of distinguishing bullying from other types of aggression between youths. A uniform definition can support the consistent tracking of bullying behavior over time, facilitate the comparison of bullying prevalence rates and associated risk and protective factors across different data collection systems, and enable the collection of comparable information on the performance of bullying intervention and prevention programs across contexts ( Gladden et al., 2014 ). The CDC and U.S. Department of Education collaborated on the creation of the following uniform definition of bullying (quoted in Gladden et al., 2014, p. 7 ):

Bullying is any unwanted aggressive behavior(s) by another youth or group of youths who are not siblings or current dating partners that involves an observed or perceived power imbalance and is repeated multiple times or is highly likely to be repeated. Bullying may inflict harm or distress on the targeted youth including physical, psychological, social, or educational harm.

This report noted that the definition includes school-age individuals ages 5-18 and explicitly excludes sibling violence and violence that occurs in the context of a dating or intimate relationship ( Gladden et al., 2014 ). This definition also highlighted that there are direct and indirect modes of bullying, as well as different types of bullying. Direct bullying involves “aggressive behavior(s) that occur in the presence of the targeted youth”; indirect bullying includes “aggressive behavior(s) that are not directly communicated to the targeted youth” ( Gladden et al., 2014, p. 7 ). The direct forms of violence (e.g., sibling violence, teen dating violence, intimate partner violence) can include aggression that is physical, sexual, or psychological, but the context and uniquely dynamic nature of the relationship between the target and the perpetrator in which these acts occur is different from that of peer bullying. Examples of direct bullying include pushing, hitting, verbal taunting, or direct written communication. A common form of indirect bullying is spreading rumors. Four different types of bullying are commonly identified—physical, verbal, relational, and damage to property. Some observational studies have shown that the different forms of bullying that youths commonly experience may overlap ( Bradshaw et al., 2015 ;

Godleski et al., 2015 ). The four types of bullying are defined as follows ( Gladden et al., 2014 ):

- Physical bullying involves the use of physical force (e.g., shoving, hitting, spitting, pushing, and tripping).

- Verbal bullying involves oral or written communication that causes harm (e.g., taunting, name calling, offensive notes or hand gestures, verbal threats).

- Relational bullying is behavior “designed to harm the reputation and relationships of the targeted youth (e.g., social isolation, rumor spreading, posting derogatory comments or pictures online).”

- Damage to property is “theft, alteration, or damaging of the target youth’s property by the perpetrator to cause harm.”

In recent years, a new form of aggression or bullying has emerged, labeled “cyberbullying,” in which the aggression occurs through modern technological devices, specifically mobile phones or the Internet ( Slonje and Smith, 2008 ). Cyberbullying may take the form of mean or nasty messages or comments, rumor spreading through posts or creation of groups, and exclusion by groups of peers online.

While the CDC definition identifies bullying that occurs using technology as electronic bullying and views that as a context or location where bullying occurs, one of the major challenges in the field is how to conceptualize and define cyberbullying ( Tokunaga, 2010 ). The extent to which the CDC definition can be applied to cyberbullying is unclear, particularly with respect to several key concepts within the CDC definition. First, whether determination of an interaction as “wanted” or “unwanted” or whether communication was intended to be harmful can be challenging to assess in the absence of important in-person socioemotional cues (e.g., vocal tone, facial expressions). Second, assessing “repetition” is challenging in that a single harmful act on the Internet has the potential to be shared or viewed multiple times ( Sticca and Perren, 2013 ). Third, cyberbullying can involve a less powerful peer using technological tools to bully a peer who is perceived to have more power. In this manner, technology may provide the tools that create a power imbalance, in contrast to traditional bullying, which typically involves an existing power imbalance.

A study that used focus groups with college students to discuss whether the CDC definition applied to cyberbullying found that students were wary of applying the definition due to their perception that cyberbullying often involves less emphasis on aggression, intention, and repetition than other forms of bullying ( Kota et al., 2014 ). Many researchers have responded to this lack of conceptual and definitional clarity by creating their own measures to assess cyberbullying. It is noteworthy that very few of these

definitions and measures include the components of traditional bullying—i.e., repetition, power imbalance, and intent ( Berne et al., 2013 ). A more recent study argues that the term “cyberbullying” should be reserved for incidents that involve key aspects of bullying such as repetition and differential power ( Ybarra et al., 2014 ).

Although the formulation of a uniform definition of bullying appears to be a step in the right direction for the field of bullying prevention, there are some limitations of the CDC definition. For example, some researchers find the focus on school-age youth as well as the repeated nature of bullying to be rather limiting; similarly the exclusion of bullying in the context of sibling relationships or dating relationships may preclude full appreciation of the range of aggressive behaviors that may co-occur with or constitute bullying behavior. As noted above, other researchers have raised concerns about whether cyberbullying should be considered a particular form or mode under the broader heading of bullying as suggested in the CDC definition, or whether a separate defintion is needed. Furthermore, the measurement of bullying prevalence using such a definiton of bullying is rather complex and does not lend itself well to large-scale survey research. The CDC definition was intended to inform public health surveillance efforts, rather than to serve as a definition for policy. However, increased alignment between bullying definitions used by policy makers and researchers would greatly advance the field. Much of the extant research on bullying has not applied a consistent definition or one that aligns with the CDC definition. As a result of these and other challenges to the CDC definition, thus far there has been inconsistent adoption of this particular definition by researchers, practitioners, or policy makers; however, as the definition was created in 2014, less than 2 years is not a sufficient amount of time to assess whether it has been successfully adopted or will be in the future.

THE COMMITTEE’S APPROACH

This report builds on the April 2014 workshop, summarized in Building Capacity to Reduce Bullying: Workshop Summary ( Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2014c ). The committee’s work was accomplished over an 18-month period that began in October 2014, after the workshop was held and the formal summary of it had been released. The study committee members represented expertise in communication technology, criminology, developmental and clinical psychology, education, mental health, neurobiological development, pediatrics, public health, school administration, school district policy, and state law and policy. (See Appendix E for biographical sketches of the committee members and staff.) The committee met three times in person and conducted other meetings by teleconferences and electronic communication.

Information Gathering

The committee conducted an extensive review of the literature pertaining to peer victimization and bullying. In some instances, the committee drew upon the broader literature on aggression and violence. The review began with an English-language literature search of online databases, including ERIC, Google Scholar, Lexis Law Reviews Database, Medline, PubMed, Scopus, PsycInfo, and Web of Science, and was expanded as literature and resources from other countries were identified by committee members and project staff as relevant. The committee drew upon the early childhood literature since there is substantial evidence indicating that bullying involvement happens as early as preschool (see Vlachou et al., 2011 ). The committee also drew on the literature on late adolescence and looked at related areas of research such as maltreatment for insights into this emerging field.

The committee used a variety of sources to supplement its review of the literature. The committee held two public information-gathering sessions, one with the study sponsors and the second with experts on the neurobiology of bullying; bullying as a group phenomenon and the role of bystanders; the role of media in bullying prevention; and the intersection of social science, the law, and bullying and peer victimization. See Appendix A for the agendas for these two sessions. To explore different facets of bullying and give perspectives from the field, a subgroup of the committee and study staff also conducted a site visit to a northeastern city, where they convened four stakeholder groups comprised, respectively, of local practitioners, school personnel, private foundation representatives, and young adults. The site visit provided the committee with an opportunity for place-based learning about bullying prevention programs and best practices. Each focus group was transcribed and summarized thematically in accordance with this report’s chapter considerations. Themes related to the chapters are displayed throughout the report in boxes titled “Perspectives from the Field”; these boxes reflect responses synthesized from all four focus groups. See Appendix B for the site visit’s agenda and for summaries of the focus groups.

The committee also benefited from earlier reports by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine through its Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education and the Institute of Medicine, most notably:

- Reducing Risks for Mental Disorders: Frontiers for Preventive Intervention Research ( Institute of Medicine, 1994 )

- Community Programs to Promote Youth Development ( National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2002 )

- Deadly Lessons: Understanding Lethal School Violence ( National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2003 )

- Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People: Progress and Possibilities ( National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009 )

- The Science of Adolescent Risk-Taking: Workshop Report ( Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2011 )

- Communications and Technology for Violence Prevention: Workshop Summary ( Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2012 )

- Building Capacity to Reduce Bullying: Workshop Summary ( Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2014c )

- The Evidence for Violence Prevention across the Lifespan and Around the World: Workshop Summary ( Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2014a )

- Strategies for Scaling Effective Family-Focused Preventive Interventions to Promote Children’s Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Health: Workshop Summary ( Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2014b )

- Investing in the Health and Well-Being of Young Adults ( Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015 )

Although these past reports and workshop summaries address various forms of violence and victimization, this report is the first consensus study by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine on the state of the science on the biological and psychosocial consequences of bullying and the risk and protective factors that either increase or decrease bullying behavior and its consequences.

Terminology

Given the variable use of the terms “bullying” and “peer victimization” in both the research-based and practice-based literature, the committee chose to use the current CDC definition quoted above ( Gladden et al., 2014, p. 7 ). While the committee determined that this was the best definition to use, it acknowledges that this definition is not necessarily the most user-friendly definition for students and has the potential to cause problems for students reporting bullying. Not only does this definition provide detail on the common elements of bullying behavior but it also was developed with input from a panel of researchers and practitioners. The committee also followed the CDC in focusing primarily on individuals between the ages of 5 and 18. The committee recognizes that children’s development occurs on a continuum, and so while it relied primarily on the CDC defini-

tion, its work and this report acknowledge the importance of addressing bullying in both early childhood and emerging adulthood. For purposes of this report, the committee used the terms “early childhood” to refer to ages 1-4, “middle childhood” for ages 5 to 10, “early adolescence” for ages 11-14, “middle adolescence” for ages 15-17, and “late adolescence” for ages 18-21. This terminology and the associated age ranges are consistent with the Bright Futures and American Academy of Pediatrics definition of the stages of development. 4

A given instance of bullying behavior involves at least two unequal roles: one or more individuals who perpetrate the behavior (the perpetrator in this instance) and at least one individual who is bullied (the target in this instance). To avoid labeling and potentially further stigmatizing individuals with the terms “bully” and “victim,” which are sometimes viewed as traits of persons rather than role descriptions in a particular instance of behavior, the committee decided to use “individual who is bullied” to refer to the target of a bullying instance or pattern and “individual who bullies” to refer to the perpetrator of a bullying instance or pattern. Thus, “individual who is bullied and bullies others” can refer to one who is either perpetrating a bullying behavior or a target of bullying behavior, depending on the incident. This terminology is consistent with the approach used by the FPBP (see above). Also, bullying is a dynamic social interaction ( Espelage and Swearer, 2003 ) where individuals can play different roles in bullying interactions based on both individual and contextual factors.

The committee used “cyberbullying” to refer to bullying that takes place using technology or digital electronic means. “Digital electronic forms of contact” comprise a broad category that may include e-mail, blogs, social networking Websites, online games, chat rooms, forums, instant messaging, Skype, text messaging, and mobile phone pictures. The committee uses the term “traditional bullying” to refer to bullying behavior that is not cyberbullying (to aid in comparisons), recognizing that the term has been used at times in slightly different senses in the literature.

Where accurate reporting of study findings requires use of the above terms but with senses different from those specified here, the committee has noted the sense in which the source used the term. Similarly, accurate reporting has at times required use of terms such as “victimization” or “victim” that the committee has chosen to avoid in its own statements.

4 For details on these stages of adolescence, see https://brightfutures.aap.org/Bright%20Futures%20Documents/3-Promoting_Child_Development.pdf [October 2015].

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

This report is organized into seven chapters. After this introductory chapter, Chapter 2 provides a broad overview of the scope of the problem.

Chapter 3 focuses on the conceptual frameworks for the study and the developmental trajectory of the child who is bullied, the child who bullies, and the child who is bullied and also bullies. It explores processes that can explain heterogeneity in bullying outcomes by focusing on contextual processes that moderate the effect of individual characteristics on bullying behavior.

Chapter 4 discusses the cyclical nature of bullying and the consequences of bullying behavior. It summarizes what is known about the psychosocial, physical health, neurobiological, academic-performance, and population-level consequences of bullying.

Chapter 5 provides an overview of the landscape in bullying prevention programming. This chapter describes in detail the context for preventive interventions and the specific actions that various stakeholders can take to achieve a coordinated response to bullying behavior. The chapter uses the Institute of Medicine’s multi-tiered framework ( National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009 ) to present the different levels of approaches to preventing bullying behavior.

Chapter 6 reviews what is known about federal, state, and local laws and policies and their impact on bullying.

After a critical review of the relevant research and practice-based literatures, Chapter 7 discusses the committee conclusions and recommendations and provides a path forward for bullying prevention.

The report includes a number of appendixes. Appendix A includes meeting agendas of the committee’s public information-gathering meetings. Appendix B includes the agenda and summaries of the site visit. Appendix C includes summaries of bullying prevalence data from the national surveys discussed in Chapter 2 . Appendix D provides a list of selected federal resources on bullying for parents and teachers. Appendix E provides biographical sketches of the committee members and project staff.

Berne, S., Frisén, A., Schultze-Krumbholz, A., Scheithauer, H., Naruskov, K., Luik, P., Katzer, C., Erentaite, R., and Zukauskiene, R. (2013). Cyberbullying assessment instruments: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 18 (2), 320-334.

Bradshaw, C.P., Waasdorp, T.E., and Johnson, S.L. (2015). Overlapping verbal, relational, physical, and electronic forms of bullying in adolescence: Influence of school context. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44 (3), 494-508.

Burk, F.L. (1897). Teasing and bullying. The Pedagogical Seminary, 4 (3), 336-371.

Currie, C., Zanotti, C., Morgan, A., Currie, D., de Looze, M., Roberts, C., Samdal, O., Smith, O.R., and Barnekow, V. (2012). Social determinants of health and well-being among young people. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe.

Eisenberg, M.E., and Aalsma, M.C. (2005). Bullying and peer victimization: Position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. Journal of Adolescent Health, 36 (1), 88-91.

Espelage, D.L., and Swearer, S.M. (2003). Research on school bullying and victimization: What have we learned and where do we go from here? School Psychology Review, 32 (3), 365-383.

Farrington, D., and Ttofi, M. (2009). School-based programs to reduce bullying and victimization: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 5 (6).

Finkelhor, D., Ormrod, R.K., and Turner, H.A. (2007). Poly-victimization: A neglected component in child victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect , 31 (1), 7-26.

Gladden, R.M., Vivolo-Kantor, A.M., Hamburger, M.E., and Lumpkin, C.D. (2014). Bullying Surveillance among Youths: Uniform Definitions for Public Health and Recommended Data Elements, Version 1.0 . Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and U.S. Department of Education.

Godleski, S.A., Kamper, K.E., Ostrov, J.M., Hart, E.J., and Blakely-McClure, S.J. (2015). Peer victimization and peer rejection during early childhood. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44 (3), 380-392.

Hamburger, M.E., Basile, K.C., and Vivolo, A.M. (2011). Measuring Bullying Victimization, Perpetration, and Bystander Experiences: A Compendium of Assessment Tools. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

Hellström, L., Persson, L., and Hagquist, C. (2015). Understanding and defining bullying—Adolescents’ own views. Archives of Public Health, 73 (4), 1-9.

Holt, M.K., Vivolo-Kantor, A.M., Polanin, J.R., Holland, K.M., DeGue, S., Matjasko, J.L., Wolfe, M., and Reid, G. (2015). Bullying and suicidal ideation and behaviors: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 135 (2), e496-e509.

Hopkins, L., Taylor, L., Bowen, E., and Wood, C. (2013). A qualitative study investigating adolescents’ understanding of aggression, bullying and violence. Children and Youth Services Review, 35 (4), 685-693.

Hymel, S., and Swearer, S.M. (2015). Four decades of research on school bullying: An introduction. American Psychologist, 70 (4), 293.

Institute of Medicine. (1994). Reducing Risks for Mental Disorders: Frontiers for Preventive Intervention Research. Committee on Prevention of Mental Disorders. P.J. Mrazek and R.J. Haggerty, Editors. Division of Biobehavioral Sciences and Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. (2011). The Science of Adolescent Risk-taking: Workshop Report . Committee on the Science of Adolescence. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. (2012). Communications and Technology for Violence Prevention: Workshop Summary . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. (2014a). The Evidence for Violence Prevention across the Lifespan and around the World: Workshop Summary . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. (2014b). Strategies for Scaling Effective Family-Focused Preventive Interventions to Promote Children’s Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Health: Workshop Summary . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. (2014c). Building Capacity to Reduce Bullying: Workshop Summary . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. (2015). Investing in the Health and Well-Being of Young Adults . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kim, Y.S., and Leventhal, B. (2008). Bullying and suicide. A review. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 20 (2), 133-154.

Koo, H. (2007). A time line of the evolution of school bullying in differing social contexts. Asia Pacific Education Review, 8 (1), 107-116.

Kota, R., Schoohs, S., Benson, M., and Moreno, M.A. (2014). Characterizing cyberbullying among college students: Hacking, dirty laundry, and mocking. Societies, 4 (4), 549-560.

McDougall, P., and Vaillancourt, T. (2015). Long-term adult outcomes of peer victimization in childhood and adolescence: Pathways to adjustment and maladjustment. American Psychologist, 70 (4), 300.

Monks, C.P., and Smith, P.K. (2006). Definitions of bullying: Age differences in understanding of the term and the role of experience. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 24 (4), 801-821.

National Institute of Justice. (2015). Comprehensive School Safety Initiative. 2015. Available: http://nij.gov/topics/crime/school-crime/Pages/school-safety-initiative.aspx#about [October 2015].

National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. (2002). Community Programs to Promote Youth Development . Committee on Community-Level Programs for Youth. J. Eccles and J.A. Gootman, Editors. Board on Children, Youth, and Families, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. (2003). Deadly Lessons: Understanding Lethal School Violence . Case Studies of School Violence Committee. M.H. Moore, C.V. Petrie, A.A. Barga, and B.L. McLaughlin, Editors. Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. (2009). Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders among Young People: Progress and Possibilities. Committee on the Prevention of Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse Among Children, Youth, and Young Adults: Research Advances and Promising Interventions. M.E. O’Connell, T. Boat, and K.E. Warner, Editors. Board on Children, Youth, and Families, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Olweus, D. (1978). Aggression in the Schools: Bullies and Whipping Boys. Washington, DC: Hemisphere.

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at School. What We Know and Whal We Can Do. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Olweus, D. (1996). Bully/victim problems in school. Prospects, 26 (2), 331-359.

Slonje, R., and Smith, P.K. (2008). Cyberbullying: Another main type of bullying? Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 49 (2), 147-154.

Smith, P. ., and Monks, C. . (2008). Concepts of bullying: Developmental and cultural aspects. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 20 (2), 101-112.

Sourander, A. (2010). The association of suicide and bullying in childhood to young adulthood: A review of cross-sectional and longitudinal research findings. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 55 (5), 282.

Sticca, F., and Perren, S. (2013). Is cyberbullying worse than traditional bullying? Examining the differential roles of medium, publicity, and anonymity for the perceived severity of bullying. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42 (5), 739-750.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2015). Safe Schools/Healthy Students. 2015. Available: http://www.samhsa.gov/safe-schools-healthy-students/about [November 2015].

Tanrikulu, I., and Campbell, M. (2015). Correlates of traditional bullying and cyberbullying perpetration among Australian students. Children and Youth Services Review , 55 , 138-146.

Tokunaga, R.S. (2010). Following you home from school: A critical review and synthesis of research on cyberbullying victimization. Computers in Human Behavior, 26 (3), 277-287.

U.S. Department of Education. (2015). Safe and Supportive Schools . Available: http://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/us-department-education-awards-388-million-safe-and-supportive-school-grants [October 2015].

Vaillancourt, T., Trinh, V., McDougall, P., Duku, E., Cunningham, L., Cunningham, C., Hymel, S., and Short, K. (2010). Optimizing population screening of bullying in school-aged children. Journal of School Violence, 9 (3), 233-250.

van Geel, M., Vedder, P., and Tanilon, J. (2014). Relationship between peer victimization, cyberbullying, and suicide in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association. Pediatrics, 168 (5), 435-442.

Vivolo, A.M., Holt, M.K., and Massetti, G.M. (2011). Individual and contextual factors for bullying and peer victimization: Implications for prevention. Journal of School Violence, 10 (2), 201-212.

Vlachou, M., Andreou, E., Botsoglou, K., and Didaskalou, E. (2011). Bully/victim problems among preschool children: A review of current research evidence. Educational Psychology Review, 23 (3), 329-358.

Wolke, D., and Lereya, S.T. (2015). Long-term effects of bullying. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 100 (9), 879-885.

Ybarra, M.L., Espelage, D.L., and Mitchell, K.J. (2014). Differentiating youth who are bullied from other victims of peer-aggression: The importance of differential power and repetition. Journal of Adolescent Health, 55 (2), 293-300.

This page intentionally left blank.

Bullying has long been tolerated as a rite of passage among children and adolescents. There is an implication that individuals who are bullied must have "asked for" this type of treatment, or deserved it. Sometimes, even the child who is bullied begins to internalize this idea. For many years, there has been a general acceptance and collective shrug when it comes to a child or adolescent with greater social capital or power pushing around a child perceived as subordinate. But bullying is not developmentally appropriate; it should not be considered a normal part of the typical social grouping that occurs throughout a child's life.

Although bullying behavior endures through generations, the milieu is changing. Historically, bulling has occurred at school, the physical setting in which most of childhood is centered and the primary source for peer group formation. In recent years, however, the physical setting is not the only place bullying is occurring. Technology allows for an entirely new type of digital electronic aggression, cyberbullying, which takes place through chat rooms, instant messaging, social media, and other forms of digital electronic communication.

Composition of peer groups, shifting demographics, changing societal norms, and modern technology are contextual factors that must be considered to understand and effectively react to bullying in the United States. Youth are embedded in multiple contexts and each of these contexts interacts with individual characteristics of youth in ways that either exacerbate or attenuate the association between these individual characteristics and bullying perpetration or victimization. Recognizing that bullying behavior is a major public health problem that demands the concerted and coordinated time and attention of parents, educators and school administrators, health care providers, policy makers, families, and others concerned with the care of children, this report evaluates the state of the science on biological and psychosocial consequences of peer victimization and the risk and protective factors that either increase or decrease peer victimization behavior and consequences.

READ FREE ONLINE

Welcome to OpenBook!