What does the research say about how to reduce student misbehavior in schools?

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, rachel m. perera and rachel m. perera fellow - the brookings institution, governance studies , brown center on education policy melissa kay diliberti melissa kay diliberti assistant policy researcher - rand, ph.d. candidate - pardee rand graduate school @mkdiliberti.

September 21, 2023

- In response to concerning reports of increasing student misbehavior, lawmakers in at least eight states are working to make it easier for teachers and principals to suspend misbehaving students from school.

- However, research indicates that suspension-promoting policies do not reduce student misbehavior, nor do they make schools safer.

- Research on the effectiveness of alternative discipline practices like restorative justice programs and Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports suggests both are promising alternatives to punishment-based approaches.

- 12 min read

This blog is part of the “School Discipline in America” series. In this series, experts from Brookings and RAND explore how U.S. public schools approach student discipline and educators’ perspectives on disciplinary approaches and challenges, providing key insights into contemporary debates over student discipline practices and policies.

Schools across the U.S. have been reporting increased student misbehavior ever since students returned to in-person schooling following the COVID-19 pandemic-related school closures. While much about the heightened student behavioral challenges facing schools remains unknown, experts suspect students are still recovering from the trauma of the pandemic and struggling from missed social and emotional development opportunities.

In response to these concerning trends, lawmakers in at least eight states are working to make it easier for teachers and principals to remove misbehaving students from school. The policy proposals put forth by these lawmakers represent a stunning about-face after 10+ years of state- and district- led reforms to promote less-punitive approaches like restorative justice practices as alternatives to suspensions. These reforms were intended to replace the types of strict discipline policies that proliferated in the 1990s and early 2000s, which emphasized suspensions and expulsions as the solution to schools’ discipline problems. But heightened student misbehavior is now raising questions about the effectiveness of these reform efforts.

Supporters of these more punitive proposals argue that recent reforms have made schools too lenient and that less-punitive approaches aren’t effectively curbing disruptions. Opponents argue that reform efforts were stymied by a variety of factors—inadequate resources for implementation, educator buy-in, and ultimately pandemic disruptions—and that a return to strict discipline policies will wrongly punish kids who are dealing with lingering mental health issues and struggling to readjust to the norms of in-person schooling.

Have schools become too lenient when it comes to student misbehavior? Can less-punitive approaches to student discipline work, especially in the context of pandemic recovery?

Over the last year, we’ve used survey data from principals to understand the current landscape of school discipline policies and practices , principals’ perspectives on suspensions , and what principals say they need to reduce student misbehavior . In this post—the final installment in this series—we use findings from this work and a review of student discipline research to reflect on school discipline in the context of pandemic recovery. We also discuss what else state and district leaders can do to reduce student misbehavior and improve school climate.

More than a half dozen states are considering a return to stricter student discipline policies, including four that have already done so

In 2023 state legislative sessions, at least eight states introduced policy proposals related to school discipline, including four states (Arizona, Kentucky, Nevada, and West Virginia) where the bills have already become law. Although the specifics differ (see Table 1), these bills broadly aim to give educators more discretion to suspend and expel misbehaving students. This includes more discretion over which types of misbehaviors can be punished (e.g., a North Carolina bill would allow suspensions for cursing and dress code violations); the conditions under which schools can suspend students and for how long (e.g., Nevada’s new law removes a requirement that schools first attempt restorative justice practices); and which students can be suspended (e.g., a new Arizona law lowers the minimum suspension grade from 5th grade to kindergarten). Two states (Florida and Nebraska) would also loosen rules guiding when educators are allowed to physically restrain students.

Table 1. State legislation related to student discipline introduced in 2023

|

|

|

|

| Arizona | : Allows K-4 students (who are at least seven years old) to be suspended for up to two days (for no more than 10 days total in a school year). K-4 students can be suspended if their behavior is “determined to qualify as aggravating circumstances and the pupil’s behavior is persistent and unresponsive to targeted interventions.” |

|

| Florida | : Would allow teachers to remove “disobedient, disrespectful, violent, abusive, uncontrollable, or disruptive” students from their classrooms, and to use “reasonable force” to protect themselves or others from injury. | No |

| Kentucky | : Students removed from the same classroom three times in a 30-day period may be suspended for being “chronically disruptive.” Principals have the discretion to determine whether the student should remain in the classroom. Principals can permanently remove students from a classroom if they determine that their presence would “chronically disrupt the education process for other students.” |

|

| Nebraska | : Would allow teachers to use “reasonable physical intervention to safely manage the behavior of a student.” Would protect school personnel who engage in physical restraint from administrative or professional discipline if such physical intervention was “reasonable.” Requires school staff to receive behavioral awareness and intervention training. | No |

| Nevada | and : Reverses a 2019 law requiring school districts to adopt a restorative justice plan. Removes requirements that schools have individual behavioral plans in place before a student can be suspended or expelled. Lowers the age schools may suspend students from 11 to six. Requires a “plan of reinstatement” after students are suspended or expelled, and a “progressive discipline plan.” |

|

| North Carolina | : Would allow students to receive long-term suspensions for “inappropriate or disrespectful language, noncompliance with a staff directive, dress code violations, and minor fights that do not involve weapons or injuries.” | No |

| Texas | : Would allow teachers to remove students if a student is “unruly, disruptive, and abusive” and their behavior is impeding the teacher’s ability to teach. Teachers can remove a student after a single “disruptive” incident. | No |

| West Virginia | : Allows teachers to remove students from the classroom for disorderly conduct, willful disobedience, or cursing at a school employee. Students exhibiting persistently disruptive behavior may be transferred to alternative educational settings. Middle and high school teachers may remove disruptive students for the day; students removed three or more times in a month for disruptive behaviors may be suspended. |

|

What does the research say about these policy ideas?

Based on our review of the research, we believe a return to stricter discipline policies (such as those described in detail in Table 1) would sacrifice the learning, development, and well-being of one group of kids for the potential benefit of another. And the groups most likely to bear the burden of a return to stricter discipline policies are the same groups who were most harmed by similar policies the last time around—Black students and other students of color, as well as students with disabilities. Making matters worse, these groups are still recovering from being among those most negatively affected by the pandemic and pandemic-related disruptions to schooling.

Here’s how we came to this conclusion:

An abundance of research indicates that strict discipline policies that promote the use of suspensions as punishment—like the types of discipline policies that proliferated in the 1990s/2000s and the ones proposed in the 2023 legislative sessions— do not reduce student misbehavior , nor do they make schools safer . What’s more, suspension-promoting policies often led to sharp increases in suspension rates, especially for students of color. In fact, research on the ineffectiveness of strict discipline policies and the resulting over-suspension of Black, Native American, and Latino students was used as motivation for the discipline reform efforts that these new policy proposals aim to reverse.

The research identifies at least three reasons why strict discipline policies don’t work for misbehaving students:

- The theory of change is deeply flawed. These policies are based on a model of deterrence that assumes that students are rational decisionmakers who will take into account the known harsh consequences associated with breaking school rules (like getting suspended or expelled) before taking an action in violation of school rules. But kids’ brains aren’t capable of the type of reasoned thinking that a deterrence model of discipline requires. Experts also stress that “ behavior is skill, not will ,” meaning that relying on punishment to improve student behavior wrongly assumes that students have the skills (e.g., frustration tolerance and emotional regulation ) to meet school’s behavioral expectations in the first place.

- Increased discretion over who to remove from the classroom, for what reason, and how to punish them only leaves more room for conscious and unconscious biases to factor into educators’ decision-making. Discipline reforms of the 2010s sought to limit the impact of biases by defining, in law or policy, when students could not be suspended or expelled. They did so amid research documenting the prevalence of racial discrimination in educators’ disciplinary decision-making , and other work showing that racial disparities are larger for infractions that rely on subjective assessments (e.g., infractions like disruption, disobedience, and willful defiance). For example, in 2011, North Carolina lawmakers formalized guidance outlining the types of infractions that could merit long-term suspensions that explicitly excluded subjective, nonviolent infractions like inappropriate or disrespectful language and “noncompliance” with staff directions.

- Suspensions harm students academically, in both the short and long run. Suspensions are associated with lower subsequent test scores , and lower rates of high school and college graduation . And research suggests that the more students struggle academically, the more likely they are to act out, creating a vicious cycle that won’t end until the student is pushed out of school altogether.

How strict discipline policies benefit non-misbehaving students—if at all—is far less clear. Proponents of recent bills (including local teachers’ unions in some states) argue that increased suspensions for misbehaving students are necessary to preserve the learning environment for non-misbehaving students. Some studies have found that non-misbehaving students’ outcomes improve when their misbehaving peers are removed. However, if suspensions do not improve the behavior of suspended students over the long run, this benefit to the learning environment could be short-lived. Indeed, other research finds a negative relationship between non-misbehaving students’ test scores and peers’ suspensions. Still others find no effect. All told, the question of how suspension-promoting policies affect non-misbehaving students remains unsettled in the research literature.

What can policymakers do to support schools in their efforts to address heightened student misbehavior instead of returning to strict discipline policies?

Principals have consistently said they need two things to reduce student misbehavior: better training for teachers and more funding . In a November 2021 survey, for example, only one-third of a nationally representative sample of principals said their teachers had been adequately trained by their teacher preparation programs to deal with student misbehavior and discipline. Similarly, when asked in a May 2022 federal survey what their schools need to better support student behavior and socioemotional development, trainings on supporting students’ socioemotional development (70%) and classroom management strategies (51%) were among principals’ top answers.

Beyond teacher training, principals also say they need more support for student and staff mental health (79%) and to hire more teachers and/or other staff (60%) to better support student behavior. More funding for mental health supports, in particular, stands out as an area where policymakers could offer schools support. Schools needed more mental health supports before the COVID-19 pandemic—and that need has only intensified since then.

Inadequate training and resources are also likely why reform efforts, including those aimed at promoting alternative practices like restorative justice (RJ) programs or Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) , have stalled in some places. Research on the effectiveness of these two popular approaches—which our work shows became widespread in U.S. public schools over the last decade—suggests both are promising alternatives. A large body of research suggests that PBIS (a schoolwide program and set of practices that aim to make behavioral expectations clear and positively rewards students for following behavioral norms) reduce behavioral incidents and suspensions and improves school climate. While the literature on RJ programs—which aim to promote conflict resolution skills in lieu of punishment—is more nascent, early studies suggest similar positive effects on behavior and school climate. This is especially true in places where sufficient time and resources were dedicated to implementing either PBIS or RJ.

When proponents of stricter discipline policies argue that schools have become too lenient on student misbehavior, it’s possible they’re describing a real dynamic driven by inadequate implementation of alternative approaches. Put another way, if these programs haven’t been implemented well (or at all) and schools have done away with traditional forms of consequences, then students’ misbehaviors may in fact be going unchecked.

Students need more caring and supportive schooling environments, not more punitive ones

Figuring out how to prevent student misbehavior and improve school climate should be a top priority for state lawmakers. Instead of falling back on old approaches to student discipline that research has largely shown to be ineffective, policymakers should listen to what the vast majority of school leaders say they need: more resources for teacher-trainings, hiring of additional teachers and staff, and mental health supports. And given the promising track record of alternative approaches like PBIS and restorative justice—and the fact that implementation of these programs is already underway in a large share of K–12 public schools—policymakers should invest more resources to ensure their success.

Related Content

Rachel M. Perera, Melissa Kay Diliberti

June 8, 2023

February 23, 2023

January 19, 2023

The authors thank Ayanna Platt for excellent research assistance for this blog post.

Rachel M. Perera is an alumna of the Pardee RAND Graduate School and a past employee of the RAND Corporation during which time she completed the majority of her contribution to this project. Perera remains an adjunct policy researcher with the RAND Corporation and received financial support from RAND to complete this project. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of the authors and do not represent positions or policies of the RAND Corporation, Brookings Institution, its officers, employees, or other donors. Brookings is committed to quality, independence, and impact in all its work.

Education Policy K-12 Education

Governance Studies

U.S. States and Territories

Brown Center on Education Policy

Sofoklis Goulas

June 27, 2024

June 20, 2024

Modupe (Mo) Olateju, Grace Cannon, Kelsey Rappe

June 14, 2024

Comparing Teachers’ and Students’ Perspectives on the Treatment of Student Misbehavior

- Open access

- Published: 03 September 2022

- Volume 35 , pages 344–365, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Mathias Twardawski ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0543-277X 1 &

- Benjamin E. Hilbig 2

3569 Accesses

Explore all metrics

The treatment of student misbehavior is both a major challenge for teachers and a potential source of students’ perceptions of injustice in school. By implication, it is vital to understand teachers’ treatment of student misbehavior vis-à-vis students’ perceptions. One key dimension of punishment behavior reflects the underlying motives and goals of the punishment. In the present research, we investigated the perspectives of both teachers and students concerning the purposes of punishment. Specifically, we were interested in the extent to which teachers and students show preferences for either retribution (i.e., evening out the harm caused), special prevention (i.e., preventing recidivism of the offender), or general prevention (i.e., preventing imitation of others) as punishment goals. Therefore, teachers ( N = 260) and school students around the age of 10 ( N = 238) were provided with a scenario depicting a specific student misbehavior. Participants were asked to indicate their endorsement of the three goals as well as to evaluate different punishment practices that were perceived (in pretests) to primarily achieve one specific goal but not the other two. Results show that teachers largely prefer general prevention, whereas students rather prefer special prevention and retribution. This discrepancy was particularly large in participants’ evaluation of specific punishment practices, whereas differences between teachers’ and students’ direct endorsement of punishment goals were relatively small. Overall, the present research may contribute to the development of classroom intervention strategies that reduce conflicts in student–teacher-interactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

What schools need to know about fostering school belonging: a meta-analysis.

Is Empathy the Key to Effective Teaching? A Systematic Review of Its Association with Teacher-Student Interactions and Student Outcomes

Risk Factors for School Absenteeism and Dropout: A Meta-Analytic Review

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In everyday school life, teachers are tasked not only with preparing or giving lessons, but also with handling a wide range of student misbehaviors (Kulinna et al., 2006 ; Wheldall & Merrett, 1988 ). These situations harbor the risk of severe consequences for both teachers and students: For teachers, the extent of student misbehavior has found to be strongly linked to their well-being and health, and it has been identified as the most salient stressor related to burnout syndrome in teachers (Aloe et al., 2014 ; Brouwers & Tomic, 2000 ; McCormick & Barnett, 2011 ). Finding suitable and effective classroom intervention strategies for such incidents is thus a crucial challenge and major concern for teachers (Melnick & Meister, 2008 ). In the best case, student misbehavior can be prevented by positive and proactive classroom management approaches (Sugai & Horner, 2006 ). However, sometimes such misbehavior simply cannot be prevented by a well-prepared lesson (e.g., if it occurs during break). In such instances, the classroom may bear some resemblance to a courtroom, with the teacher representing the judge who is in charge of finding an appropriate response to misbehavior (Weiner, 2003 ).

For students, teachers’ treatment of student misbehavior is equally essential, as it is a fundamental cause of their perception of injustice in school (Fan & Chan, 1999 ; Israelashvili, 1997 ). Crucially, such injustice perceptions have a strong impact on students’ lives, both within the school (e.g., on students’ academic self-concept, motivation, and achievements; Peter et al., 2012 ) and beyond (e.g., on students’ attitudes toward democracy; Pretsch & Ehrhardt-Madapathi, 2018 ). Importantly, students’ perceptions of injustice in school are not limited to and indeed are only marginally influenced by the grading or evaluation of students’ performances. Instead, it is the treatment of student misbehavior that appears to be an important factor (Israelashvili, 1997 ). Research suggests that such situations are among the most frequently reported situations of students’ injustice experiences, even excluding situations of false allegations (Fan & Chan, 1999 ). In other words, even if the incident of student misbehavior appears to be clear (e.g., when it is obvious who the offender or victim is), students frequently feel treated unfairly by their teachers. Eventually, the “wrong” treatment of student misbehavior may cause severe negative outcomes, such as a negative classroom climate (Peter & Dalbert, 2010 ) or a strained relationship between most or even all students and teachers (Avtgis & Rancer, 2008 ; Ratcliff et al., 2010 ). In turn, a tense student–teacher relationship and the students’ perceptions of low support from the teacher may increase conflict and, eventually, the occurrence of further classroom misbehavior (Boyle et al., 1995 ; Bru et al., 2001 , 2002 ; Ertesvåg & Vaaland, 2007 ).

Consequently, it is vital to understand and study teachers’ responses to student misbehavior to identify characteristics that do not help but harm learning and instruction. This is the endeavor of the present research. More precisely, we examine teachers’ approaches to respond to student misbehavior and compare these with students’ preferences for how this misbehavior should be treated. We particularly scrutinize one aspect of teachers’ decision-making process that has not been analyzed from both the teachers’ and students’ perspectives in the past: the goals teachers intend to achieve when reacting to student misbehavior. That is, when punishing students for misbehavior, teachers may pursue a variety of different goals as described in detail below. Importantly, students may agree or disagree with these goals and, consequently, may perceive the punishment as more or less appropriate and just (Gollwitzer & Okimoto, 2021 ).

Retribution, Special Prevention, and General Prevention as Punishment Goals

There is a considerable body of literature discussing the goals individuals generally pursue when engaging in punishment (Carlsmith et al., 2002 ; Cushman, 2015 ; Goodwin & Gromet, 2014 ; Twardawski et al., 2020b ). On the broadest level, one can differentiate between two goals that are associated with the philosophical works by Immanuel Kant and Jeremy Bentham. According to Kant ( 1952 ) punishment should follow a deontological justice principle: An offender harms a victim, a society, and its rules, and causes an imbalance to the scales of justice. Consequently, punishment is legitimate and justified to rebalance the (moral) wrong that has been caused by the offense, paying back harm doers for their misconduct and, thus, restore justice (Gerber & Jackson, 2013 ). This is typically achieved by finding a proportionate punishment that “fits” the crime (Goodwin & Gromet, 2014 ). Accordingly, a justified punishment is primarily backward-oriented and concerned with the harm caused but not about future developments (Carlsmith et al., 2002 ). The punishment goal associated with this deontological justice principle is referred to as retribution (Carlsmith & Darley, 2008 ; Carlsmith et al., 2002 ) .

According to Bentham ( 1962 ), on the other hand, punishment should follow a utilitarian justice principle. Correspondingly, the intrinsically damaging act of punishment is justifiable if it leads to positive future consequences—in particular, by preventing future misbehavior (McCullough et al., 2013 ). That is, punishment should primarily be forward-oriented and used as an instrument to facilitate compliance with social norms and reducing norm violations (Rucker et al., 2004 ). This utilitarian perspective on people’s punishment behavior can further be differentiated into special prevention and general prevention (Twardawski et al., 2020b ) . A special preventive punishment is primarily concerned with offenders themselves and intends to prevent future recidivism (Keller et al., 2010 ). A general preventive punishment, in turn, is primarily concerned with other members of the community that might have learned of the offense and, therefore, may imitate the misbehavior if it remains unpunished (Goodwin & Benforado, 2015 ).

Teachers’ and Students’ Punishment Goals

Decades of research examined laypeople’s relative endorsement of these punishment goals (for an overview, see e.g., Carlsmith & Darley, 2008 ). Of particular relevance for the present research, recent literature suggests that the endorsement of punishment goals is subject to power and hierarchy, that is, people differing in power differ in their preferences for specific goals (Mooijman & Graham, 2018 ). Particularly, after observing misbehavior, powerful people respond with distrust and increased concerns about losing their power (Mooijman et al., 2015 ). To prevent the loss of power, they use punishment as an instrument to deter observers from imitating the misbehavior. Consequently, general prevention (i.e., deterring observers from imitating the misbehavior) is the preferred goal of punishment among people in powerful positions. Whereas, people who do not occupy leadership positions show a preference for retribution (i.e., to even out the wrong that has been done) rather than for special or general prevention (Mooijman et al., 2015 ). Importantly, teachers generally occupy an inherently powerful position in school (Reeve, 2009 ), suggesting that their punishment may be similarly designed to assert control (over the classroom). More precisely, teachers may acknowledge punishment as an instrument to communicate behavioral norms and such communication is, by definition, central to utilitarian (i.e., general preventive, but also special preventive) punishment.

Moreover, and in line with this reasoning, teachers’ behavior is generally led by educational goals, above and beyond delivering academic curricula. More precisely, professionals in education ultimately pursue the goal of shaping learners and help them developing to empowered, independent, and righteous individuals. This translates into teachers creating a pedagogical environment that helps educating fundamental social values and norms, both during lecturing and beyond (Husu & Tirri, 2007 ). Importantly, teachers also follow such educational principles in the face of student misbehavior (Coverdale, 2020 ; Goodman, 2020 ; Hand, 2020 ; Liu, 2017 ). For example, it has been suggested that teachers respond in such situations “for a myriad of reasons, including but not limited to moral education of students, maintaining safety, and creating an environment conducive to learning” (Thompson et al., 2020 , p. 79). Notably, all of these reasons can be subsumed under the umbrella of special and general prevention.

In sum, based on the above reasoning, it can be theorized that teachers’ endorsement of punishment in schools particularly follows utilitarian principles. Indeed, recent research suggests that teachers show a preference for general prevention (and special prevention) over retribution, at least when they attribute the misbehavior to controllable causes (Twardawski et al., 2020a ). In the present research, we follow up on this research by investigating which punishment goals teachers endorse in the face of a specific misbehavior and how they evaluate punishment practices that are perceived to serve different goals. We hypothesized that teachers show greater endorsement of general prevention compared to retribution. Given the natural overlap of special prevention and general prevention as two related, yet distinct aspects of utilitarian punishment, we also expected that teachers generally support special prevention over retribution, whereas we had no hypothesis regarding potential differences between special and general prevention. It should be noted that any hypotheses concerning the role of special prevention were necessarily more speculative, as past research only rarely considered the differences between general and special prevention and, often, did not explicitly examine special prevention.

As outlined above, it is not only vital to examine and understand the relative endorsement of punishment goals among teachers. Rather, it is equally important to consider the students’ perception of teachers’ punishment to identify potential characteristics of the punishment that may foster subjective injustice (Fan & Chan, 1999 ; Israelashvili, 1997 ). Differences between teachers’ and students’ relative endorsement of punishment goals may ultimately result in such undesirable outcomes (Mooijman et al., 2017 ). However, there is a lack of research on students’ endorsement of punishment goals and one could therefore derive contrary hypotheses for the students’ perspective: On the one hand, students are in a relatively less powerful position in the school context (Reeve, 2009 ) and, thus, should show less endorsement of general prevention than of retribution (Mooijman et al., 2015 ). On the other hand, this reasoning largely stems from research on adults, whereas evidence on children’s endorsement of punishment goals is scarce. In fact, the few existing insights into children’s punishment goals rather suggest that children value both retribution and prevention in their own punishment (Marshall et al., 2021 ; Twardawski & Hilbig, 2020 ). Therefore, it is unclear whether students show a relatively larger endorsement of retribution as compared to special and general prevention, especially when evaluating teachers’ reactions to student misbehavior. Consequently, investigating the extent to which students share teachers’ relative endorsement of punishment goals promises a fundamental contribution to the literature.

The Present Research

The primary goal of the present research is to examine and compare teachers’ and students’ relative endorsement of punishment goals. Therefore, we provided teachers and school students with a scenario describing a specific case of student misbehavior and tested whether teachers and students show similar preferences in punishment goals (i.e., retribution, special prevention, and general prevention) when directly asked to indicate their endorsement of these goals (Mooijman et al., 2015 ). That is, teachers were asked to imagine being in charge of reacting to this incident of student misbehavior and to indicate the degree to which they would want to achieve either of the three punishment goals. Similarly, students indicated their endorsement of the three goals when thinking about punishment of the offender in a structurally equivalent case of student misbehavior. We refer to this approach as the direct endorsement measure of teachers’ and students’ punishment goals.

In addition to analyzing teachers’ and students’ direct endorsement of the goals punishment ought to achieve in a specific case of student misbehavior, it is important to examine teachers’ assessment of concrete punishment practices vis-à-vis students’ perceptions of these practices. Specifically, research has shown that people’s direct endorsement of punishment goals is only weakly correlated with their actual punishment of a specific case of misbehavior (Crockett et al., 2014 ). This also applies to teachers, as their assessment of concrete punishment practices and the goals they purportedly endorse are similarly misaligned (Twardawski et al., 2020a ). For everyday school life, however, examining the perception of concrete and specific punishment practices may be equally important as the endorsement of rather abstract punishment goals—in particular if the evaluation of practices and abstract endorsement do not correspond perfectly. More specifically, teachers and students may agree on the endorsement of abstract punishment goals that may be pursued in response to a student misbehavior, but nonetheless disagree on a particular punishment practice designed to achieve these goals (or vice versa). Consequently, besides measuring teachers’ and students’ direct endorsement of abstract punishment goals in the case of a student misbehavior, we additionally measured teachers’ punishment goal preferences in a more indirect way, asking them to rate the appropriateness of three punishment practices that were perceived (in pretests) as primarily serving one of the goals. Vitally, we provided students with the same punishment practices and asked them to indicate the extent to which they evaluated these practices as fair, appropriate, and just, if shown by a teacher. We refer to this approach as the punishment practice evaluation measure of teachers’ and students’ punishment goal preferences.

Most critically, the core focus of the present research is to strictly examine whether teachers and students differ in their relative endorsement of various punishment goals and in how they evaluate corresponding punishment practices. More precisely, we examine the degree to which teachers and students show preferences with regard to the three punishment goals and compare these intra-individual preferences (i.e., the rank order of goals) between the two groups. Our hypothesis as stated above was that teachers indicate a preference for general (and special) prevention over retribution. For students’ punishment goal preferences, in turn, we had no strong a priori expectation, but deemed a preference for retribution most likely given the literature.

As recommended, we report how we determined our sample size, all data exclusions (if any), all manipulations, and all measures (Simmons et al., 2012 ). Furthermore, all materials (including instructions and materials of the pretest study; all materials are translated from German to English), along with all data, analyses scripts, and supplementary analyses are available on the OSF and can be accessed via the following link: https://osf.io/r5d8v/ .

Data were collected from both pre-service (that is university students becoming teachers) and in-service teachers in conjunction with a project on other research questions (Twardawski et al., 2020a ). In-service and pre-service teachers were recruited through mailing lists, social media platforms, personal contacts, and recruitment in schools to participate in a study lasting 10–15 min. For in-service teachers, 103 participants started an online-version of the questionnaire, with n = 74 (72%) completing it. Additionally, n = 67 teachers opted for completing a paper and pencil version of the questionnaire. The total sample of in-service teachers therefore comprised N = 141 participants. Around two thirds of these participants (i.e., n = 92; 65%) were female (two participants did not indicate their gender), and ages ranged between 23 and 70 years ( M = 40.77, SD = 11.13). For pre-service teachers, 160 participants started the questionnaire (all of them participated online), of which N = 119 (74%) completed it. In this final sample of pre-service teachers, ages ranged between 18 and 36 years ( M = 23.38, SD = 3.09) and 84% ( n = 100) of participants were female. These pre-service teachers were in their sixth semester of studies on average ( M = 5.61, SD = 3.23) and mostly studied teaching on high school level (35%), teaching for primary schools (28%), or special education (22%). In total, we collected complete data sets from N = 260 pre-service and in-service teachers, of whom n = 192 were female (74%).

Data from students were collected in the fifth and sixth grade of three public German schools, again, in conjunction with projects on other research questions (Twardawski et al., 2020a ). In total, N = 238 children from twelve school classes participated in the study. Around 45% of participants (i.e., n = 106) were female, most children’s mother language was German (92%), and ages ranged between 9 and 12 ( M = 10.46, SD = 0.61; one child did not indicate her age).

To evaluate the sample sizes of the teachers ( N = 260) and students ( N = 238) with regard to the planned within-subjects comparisons of teachers’ and students’ support for the three punishment goals (retribution, special prevention, and general prevention), two separate sensitivity power analyses were conducted using G*Power (Faul et al., 2007 , 2009 ). One of these power analyses was specified to detect within-subjects differences in participants’ assessment of the three punishment goals (i.e., as an estimate of teachers’ and students’ punishment goal preferences). Assuming a conventional α = 0.05, a nonsphericity correction of ε = 1, and a standard power criterion of 1 − β = .90, this resulted in a detectable effect size of f = .16 for the teacher and f = .15 for the student sample in a repeated measures ANOVA. We further evaluated the collective sample sizes of teachers and students (total N = 498) with regard to our main test of whether teachers and students differ in their relative endorsement of punishment goals. We therefore calculated a sensitivity power analysis to detect a within-between interaction in a mixed model with two groups (teachers and students) as between-subjects factor and the three punishment goals (retribution, special prevention, and general prevention) as within-subjects factor. Given a standard power criterion of 1 − β = .90, α = .05, number of groups = 2, number of measurements = 3, and nonsphericity correction ε = 1, this resulted in a detectable effect size of f = .11 in a mixed-model ANOVA. Thus, there was high statistical power for even relatively small effect sizes throughout.

Measures and Procedures

The teacher perspective.

Teachers had the chance to participate in the study online or via a paper and pencil version of the questionnaire. After providing informed consent, participants received a scenario describing a student destroying a recently prepared hand drum of another student. This scenario read as follows:

Within the past lessons, you manufactured hand drums with your students that you plan to use today. You briefly turn to the board. Once you face the class again, you see how Florin causes a hole in Maxi’s drum . As a result, the drum is broken. Footnote 1

Participants were then asked to provide answers on several control variables regarding the perception of the misbehavior, starting with (i.) the stability and (ii.) controllability of the cause of the student’s misbehavior. Furthermore, participants were asked to indicate (iii.) the student’s responsibility for what occurred, how much (iv.) anger and (v.) sympathy they would feel toward the misbehaving student as well as (vi.) to what degree it is possible to influence the student’s future behavior. Each response was rated on a 6-point scale ranging from 0 = “not at all” to 5 = “completely.” Next, they answered the punishment practice evaluation measure and rated the appropriateness of three punishment practices that teachers may use as a response to the displayed student misbehavior. Punishment practices are provided in Table 1 . These practices were designed based on the results of a thorough pretest (in an independent sample) and therein judged as serving predominantly one of the punishment goals. Footnote 2 Appropriateness of each practice was indicated on a 6-point scale ranging from 0 = “not at all appropriate” to 5 = “completely appropriate.” Finally, participants provided their direct endorsement of the three punishment goals in the specified situation of student misbehavior, indicating the goals they would want to accomplish if presented a chance or obliged to react to the misbehaving student. To this end, we adapted one item for each punishment goal (retribution, special prevention, and general prevention) from Orth ( 2003 ) and Weiner et al. ( 1997 ). The item measuring direct endorsement of retribution read as follows: “To what extent would you like to react to even out the wrong that Florin has done?”; the item measuring endorsement of special prevention read “To what extent would you like to react to prevent recidivism by Florin?”; and the item measuring endorsement of general prevention read “To what extent would you like to react to prevent other students of showing similar behavior in the future?” Each item was answered on a 6-point scale ranging from 0 = “not at all” to 5 = “completely,” with higher values indicating stronger endorsement of a particular punishment goal. After answering all questions, participants worked on several other tasks that pertained to a different research question (Twardawski et al., 2020a ). Thus, this part of the material will not be further discussed in the present article. Finally, participants provided demographic information, before they were fully debriefed and thanked.

The Student Perspective

Data from students were collected in schools. On arrival in the classroom, students provided the experimenters with the consent form signed by their parents or legal guardians. Then, students were seated individually in front of computers. Two experimenters welcomed the class and gave them verbal instructions on the subsequent tasks. The first task was on an unrelated research question (Twardawski & Hilbig, 2020 ) and will therefore not be further discussed in the present article. Subsequently, students provided demographic information before they were introduced to the main task. Therein, students were asked to indicate their perceptions of a misbehavior and different teacher responses to it. This misbehavior and the responses were presented in short comic strips. Using an exemplary misbehavior, students received comprehensive instructions on the procedure of the task, before working on the task individually. They were provided with a comic strip depicting one student destroying the recently prepared hand drum of the other student (i.e., a structurally equivalent scenario that teachers received). The gender of the misbehaving student and the victim were counterbalanced (i.e., it was either the boy destroying the drum of the girl or vice versa). Next, students received three comic strips depicting potential punishment responses of the teacher (either female or male; counterbalanced) in the comic—reflecting the punishment practice evaluation measure . Students were asked to rate the extent to which they perceived these practices as just , appropriate , and fair on 6-point scales ranging from 0 = “not at all” to 5 = “completely.” These three items per punishment practice were aggregated (that is, averaged) and showed high internal consistencies (retributive reaction: α = .92; special preventive reaction: α = .90; general preventive reaction: α = .93). Footnote 3 Similar to teachers, students further answered all of the control questions outlined above (i.e., the stability and controllability of the cause of the student’s misbehavior, the student’s responsibility for what occurred, how much anger and sympathy they would feel toward the misbehaving student, and to what degree it is possible to influence the student’s future behavior), as well as their direct endorsement of the three punishment goals in the specified situation. Mirroring the teachers’ materials, the item measuring direct endorsement of retribution read as follows: “Florin should be punished for their behavior to even out the wrong committed”; the item measuring endorsement of special prevention read “Florin should be punished for their behavior to prevent them from doing something like this again”; and the item measuring endorsement of general prevention read “Florin should be punished for their behavior to prevent others from imitating them.” Again, scales ranged from 0 = “not at all” to 5 = “completely.” Finally, students were fully debriefed and thanked.

Preliminary Data Analyses

Before conducting our main analyses, we first ensured that we could treat pre-service and in-service teachers as one homogeneous group. Therefore, we tested whether pre-service and in-service teachers differed systematically in their endorsement of punishment goals for both the direct endorsement and the punishment practice evaluation measure. For each measure of endorsement of punishment goals, we conducted a separate mixed model ANOVA predicting the endorsement of the three punishment goals (retribution, special prevention, and general prevention) as within-subjects factor and the sample (pre-service and in-service teachers) as between-subjects factor. It turned out that there were only negligible differences between pre-service and in-service teachers (the detailed results of these tests, including test statistics, are available online at the OSF). Thus, we considered it reasonable to combine the two groups to one group of teachers.

Additionally, we considered it vital to determine whether teachers and students perceived the student misbehavior itself in a similar manner. We therefore calculated a Spearman correlation between the mean ratings of all control variables we collected on participants’ perception of the scenario (i.e., the stability and controllability of the cause of the student’s misbehavior, the student’s responsibility for what occurred, how much anger and sympathy they would feel toward the misbehaving student, and to what degree it is possible to influence the student’s future behavior). This analysis revealed a very high correlation, r s = .83. Correspondingly, differences in punishment goal preferences between teachers and students cannot be ascribed to different perceptions of the student misbehavior itself and can therefore be reasonably be attributed to different preferences for how to deal with this misbehavior.

Main Analyses

For the main analyses, we first conducted in-depth within-subjects comparisons on teachers’ and students’ ratings per punishment goal measurement approach to examine their groups’ punishment goal preferences (i.e., the intra-individual rank order in the endorsement of the three punishment goals). Subsequently, we directly compared teachers’ and students’ preferences (i.e., the rank order) of punishment goals, again separately for each punishment goal measurement approach.

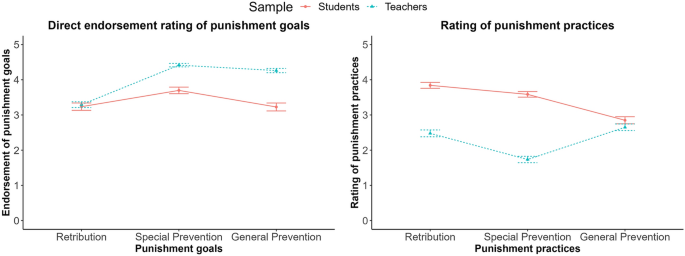

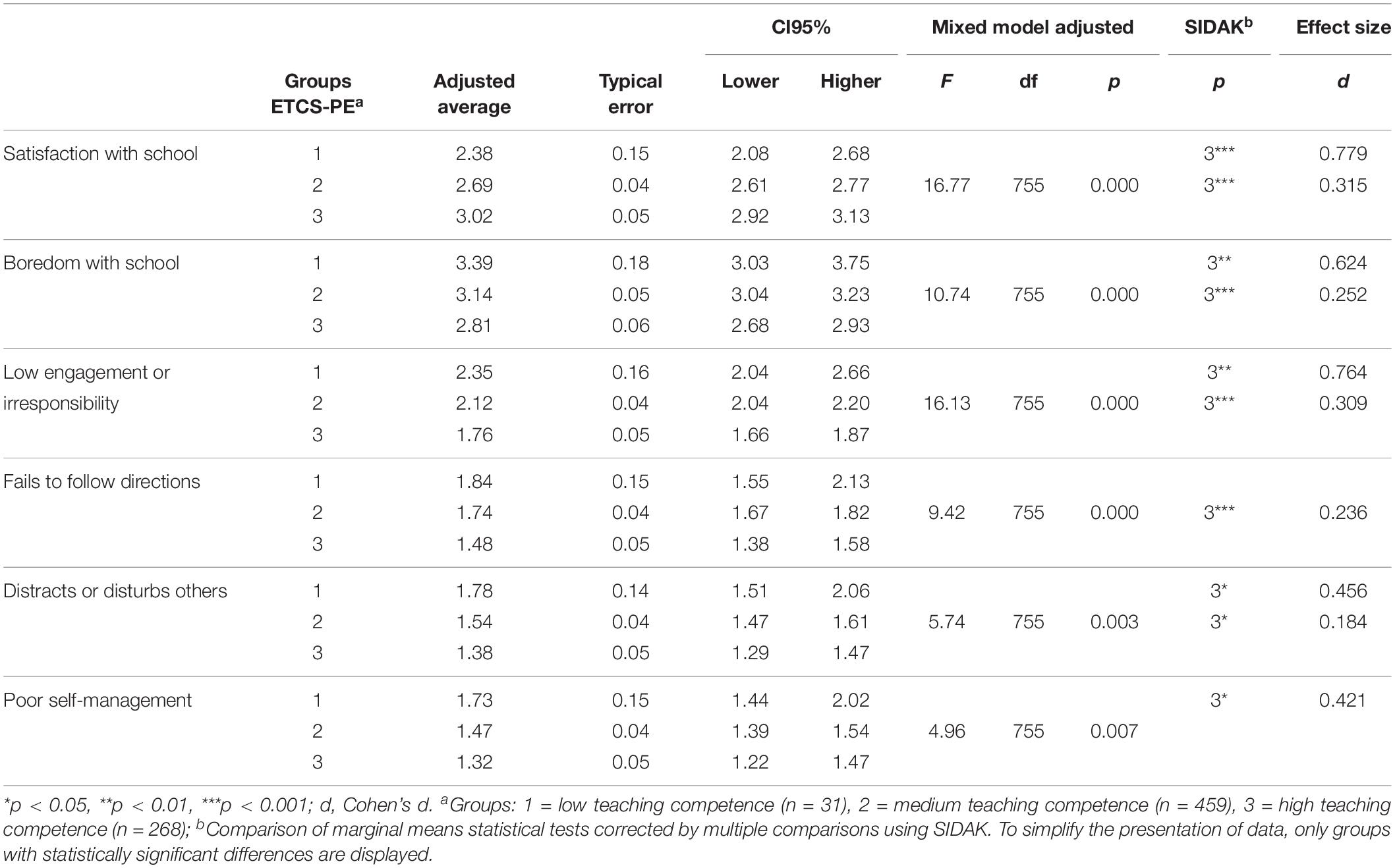

Direct Endorsement of Punishment Goals

As shown in Fig. 1 (left panel), teachers indicated a generally higher direct endorsement of utilitarian punishment goals as compared to retribution. Specifically, special prevention was the most endorsed goal ( M = 4.42, SD = 0.79), closely followed by general prevention ( M = 4.26, SD = 0.98). Notably, in line with our hypotheses, retribution received substantially lower endorsement ratings from teachers ( M = 3.29, SD = 1.30). To statistically test this pattern, we used a repeated measures ANOVA predicting the endorsement of the three punishment goals (retribution, special prevention, and general prevention) as within-subjects factor, followed by pairwise post-hoc t -tests. The analysis of variance confirmed significant differences between direct endorsement ratings of punishment goals, F (2, 518) = 109.20, p < .001, \({\hat{\upeta }}_{\mathrm{G}}^{2}\) = .19. As hypothesized, follow-up t -tests directly examining our hypothesis revealed significantly greater endorsement of general prevention compared to retribution, t (259) = 9.96, p < .001, d = 0.59. Likewise, special prevention received significantly greater endorsement than retribution, t (259) = 12.61, p < .001, d = 0.73. Interestingly, special prevention also received significantly higher ratings than general prevention, albeit yielding only a miniscule effect size, t (259) = 2.82, p = .005, d = 0.12.

Results. Comparison of teachers’ and students’ direct endorsement of the three punishment goals (left panel) and their evaluation of different punishment practices (right panel, i.e., teachers’ appropriateness ratings of the practices, and students’ evaluation of how fair, appropriate, and just the teachers’ punishment practices are). Error bars represent one standard error of the mean

Moreover, data revealed notable differences for students’ direct endorsement of the three punishment goals. That is, students indicated highest endorsement ratings for special prevention ( M = 3.70, SD = 1.44), whereas general prevention ( M = 3.23, SD = 1.74) and retribution ( M = 3.24, SD = 1.62) were equally supported. A repeated measures analysis of variance confirmed significant differences between endorsement ratings of punishment goals of students, F (2, 474) = 12.73, p < .001, \({\hat{\upeta }}_{\mathrm{G}}^{2}\) = .02. Follow-up t -tests revealed that special prevention was most endorsed and received slightly higher ratings than retribution, t (237) = 5.23, p < .001, d = 0.21, and general prevention, t (237) = 4.17, p < .001, d = 0.20. Differences between retribution and general prevention were negligible, t (237) = 0.07, p = .943, d = 0.003.

The core focus of the present research is a direct comparison of teachers’ and students’ punishment goal preferences (i.e., the rank order in punishment goals of the two groups). As can be seen in Fig. 1 (left panel), teachers’ and students’ direct endorsement of the three punishment goals particularly differed regarding the relative degree of endorsement of retribution. Specifically, whereas retribution received endorsement ratings descriptively comparable to special prevention and general prevention in students, it received substantially lower endorsement ratings compared to the other goals from teachers. To statistically test whether teachers and students actually differed in their preferences of punishment goals using this measurement approach, we conducted a mixed model ANOVA predicting the direct endorsement of the three punishment goals (retribution, special prevention, and general prevention) as within-subjects factor and the sample (teachers and students) as between-subjects factor. Most importantly, this analysis revealed a significant interaction of the goal to be rated and the sample, F (2, 992) = 27.88, p < .001, \({\hat{\upeta }}_{\mathrm{G}}^{2}\) = .02.

Punishment Practice Evaluation Measure of Punishment Goals

For the punishment practice evaluation measure, contrary to the direct endorsement measure of punishment goals, teachers rated the general preventive punishment practice as most appropriate ( M = 2.65, SD = 1.50), closely followed by the retributive practice ( M = 2.48, SD = 1.57). Importantly, the special preventive practice was rated as least appropriate ( M = 1.73, SD = 1.46). These patterns are also shown in Fig. 1 (right panel). Again, we conducted a repeated measures ANOVA to compare teachers’ appropriateness ratings of the three punishment practices, followed by pairwise post-hoc t -tests. The analysis of variance confirmed significant differences between appropriateness ratings of the three punishment practices, F (2, 518) = 29.12, p < .001, \({\hat{\upeta }}_{\mathrm{G}}^{2}\) = 0.06. In contrast to the direct endorsement measure and contrary to our hypothesis, follow-up t -tests revealed no significant differences between the general preventive and retributive punishment practices, t (259) = 1.28, p = .202, d = 0.08. Interestingly, the special preventive practice was rated significantly less appropriate than both the retributive practice, t (259) = − 5.64, p < .001, d = − 0.34, and the general preventive practice, t (259) = − 8.00, p < .001, d = − 0.43.

Similar to what we found for teachers, students’ evaluation of the three punishment practices also differed from students’ direct endorsement of punishment goals. That is, students indicated highest ratings for the retributive practice ( M = 3.84, SD = 1.30), closely followed by the special preventive practice ( M = 3.59, SD = 1.22). The general preventive practice received the lowest ratings ( M = 2.85, SD = 1.55). Again, we conducted a repeated measures ANOVA to compare students’ perceptions of the three punishment practices, followed by pairwise post-hoc t -tests. The analysis of variance confirmed significant differences between the evaluation of the three punishment practices, F (2, 474) = 49.42, p < .001, \({\hat{\upeta }}_{\mathrm{G}}^{2}\) = .09. Follow-up t -tests revealed that the retributive practice received significantly higher ratings than the general preventive practice, t (237) = 9.31, p < .001, d = 0.46, and the special preventive practice, t (237) = 2.58, p = .010, d = 0.14. However, the effect size of the latter was rather small. Furthermore, the special preventive practice received higher ratings than the general preventive practice, t (237) = 7.01, p < .001, d = 0.36.

Again, we directly compared teachers’ and students’ evaluations of the three punishment practices. As depicted in Fig. 1 (right panel), teachers and students differed substantially regarding their evaluations of the two preventive punishment practices. That is, both teachers and students rated the retributive practice in a comparable manner (i.e., both perceived it as relatively suitable). At the same time, the special preventive practice received the lowest appropriateness ratings from teachers, whereas students perceived this practice as relatively suitable (i.e., fair, just, and appropriate). Likewise, the general preventive practice yielded differences in that it received highest appropriateness ratings from teachers, but lowest ratings from students. Again, we tested whether teachers and students differed in their preferences for the three punishment practices (i.e., the group-level rank order) using a mixed model ANOVA with the three punishment practices (retributive practice, special preventive practice, and general preventive practice) as within-subjects factor and the sample (teachers and students) as between-subjects factor. This analysis again revealed a significant interaction of the punishment practice and the sample, F (2, 992) = 52.26, p < .001, \({\hat{\upeta }}_{\mathrm{G}}^{2}\) = .05.

Research suggests that teachers have to deal with student misbehavior on a daily basis (Kulinna et al., 2006 ; Wheldall & Merrett, 1988 ). This is not only particularly challenging for teachers (Aloe et al., 2014 ; Brouwers & Tomic, 2000 ), but also threatens to lead to perceived injustice among students (Fan & Chan, 1999 ; Israelashvili, 1997 ). Correspondingly, it is vital to investigate and analyze teachers’ classroom intervention strategies to understand the factors enhancing students’ perceptions of injustice. One key dimension of punishment behavior reflects the underlying motives and goals of the punishment (Carlsmith et al., 2002 ; Gromet & Darley, 2009 ). This aspect of the teachers’ punishment is of particular interest, given that teachers and students are likely to differ in their relative endorsement of punishment goals and these differences may ultimately result in undesirable outcomes, such as a self-perpetuating cycle of student misconduct and teacher punishment that is perceived as unjust (Mooijman & Graham, 2018 ).

Herein, we examined the perspectives of both teachers and school students on the goals of punishment in a specific situation of student misbehavior. Specifically, we investigated the extent to which (pre-service and in-service) teachers endorse retribution (i.e., evening out the harm caused), special prevention (i.e., preventing recidivism of the offender), and general prevention (i.e., preventing imitation of others) as goals of (their) punishment. We therefore provided teachers with a scenario describing a student destroying the belongings of another student and asked them to indicate to what extent they endorse the three punishment goals in this situation. Furthermore, we measured teachers’ relative endorsement of punishment goals in a more indirect way, asking them to rate the appropriateness of different punishment practices that were perceived as primarily achieving either of the goals (as shown in a pretest). Importantly, students were asked to indicate their endorsement of the three punishment goals as a basis for a response to a structurally equivalent student misbehavior that was used to study teachers’ perspectives. Additionally, students rated how fair, appropriate, and just they perceived teachers’ punishment practices designed to achieve different goals. In total, we thus investigated teachers’ and students’ preferences for retribution, special prevention, and general prevention as punishment goals and whether these preferences are comparable.

As hypothesized, teachers indicated a general preference for general prevention and special prevention over retribution. This was particularly true for general prevention, whereas special prevention was only preferred over retribution in the direct endorsement measure of punishment goals. Students indicated a favorable evaluation of teachers’ punishment practice that was linked to retribution, especially when compared to a more general preventive practice. That is, evaluating teacher’s punishment practices that are perceived as achieving different goals, students rated the retributive practice more favorably than the general (and, to a lesser degree, special) preventive practices. Conversely, for the direct endorsement measure, students rated special prevention as the most endorsed goal of punishment. Notably, differences in students’ endorsement of the three punishment goals were relatively rather small in general, suggesting that students have no strong punishment goal preferences when asked directly (mirroring the literature on explicit support of punishment goals in adults; Applegate et al., 1996 ; Carlsmith, 2008 ).

In sum and most importantly, the present research provides the opportunity to directly compare teachers’ and students’ approaches on punishment given the same incident of misbehavior (although materials were adapted to the age of participants, as is discussed below). Analyses comparing students’ and teachers’ relative endorsement of punishment goals indeed revealed substantial differences between students’ and teachers’ punishment goal preferences, in particular for the endorsement of general prevention. Whereas general prevention was least endorsed by students both when asked to indicate their endorsement directly and when evaluating teachers’ punishment practices linked to different goals, it consistently received high support by teachers. This may be particularly problematic, given that the pursuit of general prevention as the goal of punishment may have undesirable consequences. In fact, research in organizational psychology has shown that an authority’s punishment for general preventive purposes is perceived as a signal of distrust and actually leads to a decrease in rule compliance by subordinates (Mooijman et al., 2017 ). Correspondingly, it could be suggested that this decrease in rule compliance is due to differing goals of people with different hierarchical positions. However, although the present research points to this hypothesis, future research is needed to illuminate this further, in particular given that one cannot necessarily generalize from leaders reacting to subordinate misbehavior in organizational teams to teachers reacting to student misbehavior in schools.

Interesting for the general punishment goal literature, in both teachers and students, we found notable inconsistencies between the direct endorsement of punishment goals and the evaluation of practices that were perceived as achieving these goals. For example, whereas special prevention was consistently of highest preference for both teachers and students when directly asking for their endorsement of the goals, the corresponding punishment practice received relatively low ratings. Furthermore, retribution received rather low direct endorsement scores, whereas the retributive punishment practice was evaluated particularly positively. This is in line with considerable research showing that individuals endorse other goals in the abstract than they support when translated to concrete punishment practices (Applegate et al., 1996 ). Once more, this also emphasizes that methodological considerations are crucial for the study of people’s endorsement of punishment goals (Twardawski et al., 2020b ).

The present results also have several practical implications for the treatment of misbehavior in schools. Given notable discrepancies between teachers’ endorsement of punishment goals and their support for corresponding punishment practices, one might encourage teachers and individuals involved in teacher education to reflect on the topic of punishment in the educational setting and the goals they ought to achieve when responding to misbehaving students. This is particularly important, given that teachers expressed a consistent preference for general prevention as the goal of their punishment, whereas students’ endorsement of this goal was rather low—especially for the general preventive punishment practice. However, students’ negative evaluation of the general preventive practice was arguably to be expected, as one key of actual punishment practices that are meant to prevent future misbehavior is the public display of the offender, the misbehavior, and the punishment (Carlsmith, 2006 ; Keller et al., 2010 ) and such a public reprimand has been found to be unacceptable for students (Elliott et al., 1986 ).

Then again, the consistencies between teachers’ and students’ punishment goal preferences when directly asked for their endorsement of the goals may be cause for optimism in that it should be possible in principle to respond to student misbehavior without triggering students’ perception of injustice—and even without giving up on the goal of general prevention in punishment. That is, agreement of teachers and students was higher when thinking about punishment (and its goals) in the abstract (i.e., the direct endorsement measure) as compared to the evaluation of concrete punishment practices ought to achieve these goals. In light of this finding, teachers may consider to explicitly discuss classroom policies in collaboration with their students to manage potentially emerging student misbehavior. Receiving students’ commitment to such policies based on an abstract support of general preventive punishment may decrease the likelihood of perceived injustice, in case the policy has to be applied to treat a concrete case of student misbehavior (however, see qualifying results from research on the Three Strikes Initiative; Applegate et al., 1996 ).

An alternative approach that may circumvent the problems arising from differences between students’ and teachers’ perspectives concerning rather punitive reactions to misbehavior (as examined in the present research) follows the principles of restorative justice (Bazemore, 1998 ; Braithwaite, 1998 ). This philosophy of dealing with misbehavior considers the perspectives of victims, offenders, and the community in which the offense occurred to assign a punishment. One key aspect of this approach is a face-to-face meeting involving all parties: the victim, the offender, and other community members (Wenzel et al., 2010 ). In this meeting, offender and victim present their perspectives on the misbehavior and, using a consensus decision-making approach, work out an appropriate punishment for the offender with participation from all parties. Potentially, such restorative justice procedures may resolve the otherwise existing differences in students’ and teachers’ views on an appropriate punishment. In fact, various schools have already introduced justice approaches inspired by restorative justice—such as peer mediation in the case of student conflict or school community conferencing—and although most programs are still in their infancy, there is first evidence for its success with decreasing rates of bullying between students and more positive teacher-student-relationships (Gregory et al., 2016 ).

However, such approaches also entail wide-ranging challenges (McCluskey et al., 2008 ). For example, the implementation of restorative justice processes requires deep changes in school climate and, therefore, takes several years to run smoothly (Gregory et al., 2016 ). Furthermore, not all misconducts can go through such comprehensive processes (Varnham, 2005 ). Therefore, it is nevertheless important to improve teachers’ ability to independently deal with student misbehavior, and to find punishments that are both appropriate for teachers and perceived as fair by students. The present findings may be helpful to achieve this.

Before concluding, potential limitations of the present research should be acknowledged. First off, the punishment practice evaluation measure, despite the additional insights if affords, does yield certain challenges. Specifically, the punishment practices we extracted from the pretest were perceived as primarily achieving one of the goals (while being equally severe). However, they still also achieved the other two goals to some extent. In fact, the practices may even differ on dimensions we did not consider (and test) in our pretest (e.g., reputational concerns among teachers). However, creating punishment practices that exclusively achieve one punishment goal but no others (while being parallel on any other dimension) may render the teacher responses somewhat artificial (at best), simply because every-day punishment often serves multiple goals at the same time (Gromet & Darley, 2009 ). Therefore, endorsement of these practices in our research cannot be interpreted as a direct measure of punishment goal preferences. Nonetheless, given the typically moderate correlations between endorsement of abstract punishment goals and preferred punishment practices (Crockett et al., 2014 ; Twardawski et al., 2020a ), it seemed vital to additionally examine preferences on this specific level, too.

Moreover, we used scenarios and comic strips to investigate teachers’ and students’ perspectives on punishment, respectively, rather than observing actual behavior in schools. Indeed, there is arguably an inherent difference between situations actually occurring in class and such hypothetical scenarios (Hughes & Huby, 2004 ; Schoenberg & Ravdal, 2000 ). Of note, in the present research, extensive care was taken to ensure that the material was suitable (e.g., by consulting teachers to evaluate and improve the material) and to increase the relevance and authenticity of the student misbehavior and the concrete punishment practices of the teachers used. Additionally, similar methodological approaches have been successfully used to investigate teachers’ evaluation and decision-making in other domains (Baudson & Preckel, 2013 ). Nonetheless, future research may consider studying actual student misbehavior and punishment practices by teachers in school settings using field observations (Klein, 2008 ; Klein et al., 1993 ; Lipshitz et al., 2001 ).

Further associated with the scenario and comic strip used, teachers and students were confronted with structurally equivalent descriptions of a student misbehavior. However, presentation of the scenario was adjusted to the sample: Teachers read a verbal description of the misbehavior, whereas the misbehavior was presented as a comic strip to students (i.e., to reduce the amount of text). Such an adjustment of material is typical for developmental psychological research comparing the perspectives of adults and children (e.g., McCrink et al., 2010 ; Powell et al., 2012 ). Importantly, several control measures on the perception of the misbehavior (rather than the reactions evaluated as main variables) show that teachers and students perceived the situation very similarly, despite its adaptation to different formats. Nevertheless, differences between teachers’ and students’ perspectives may, to some extent, also be a product of this adaptation process.

Relatedly, data from students were exclusively collected in the classroom during school time. By contrast, teachers were provided with the possibility to opt for answering a paper and pencil or online version of the questionnaire and may have answered the questionnaire outside their school environment. While a mixed-mode assessments (i.e., the combination of a variety of survey modes) is becoming increasingly popular and can already be considered common practice (e.g., Dumont et al., 2019 ; Hübner et al., 2017 ; von Keyserlingk et al., 2020 ), the context of study participation may have influenced responses and, thus, the results yielded. In line with this reasoning, recent literature shows that unsupervised web-based study participation is not strictly equivalent to other assessment modes; although biases introduced by web-based testing were generally small (Zinn et al., 2021 ).

Additionally, we only used one specific instance of student misbehavior (i.e., a student destroying the belongings of another student). Therefore, the results obtained here may be subject to unknown specifics of this scenario and the punishment practices offered (Twardawski et al., 2020b ). Indeed, it could be argued that teachers’ and students’ endorsement of punishment goals may be influenced by other aspects of the misbehavior not addressed herein, such as the magnitude of harm caused (Carlsmith, 2006 ). It is up to future research to replicate and extend the present findings to more diverse forms of student misbehavior. This research could, additionally, also make use of different forms of data collection, such as conducting interviews or collecting other more qualitative data (e.g., Penderi & Rekalidou, 2016 ). Likewise, we only collected student data from a very specific age group (children around the age of 10). Our theorizing herein is mostly concerned with the position in the school context (i.e., being a teacher vs. a student) rather than age. Consequently, we would not expect that age strongly determines individuals’ relative endorsement of punishment goals in school. However, this is rather speculative and past research reported age differences in evaluations of classroom intervention strategies in some domains (e.g., Bear & Fink, 1991 ). Hence, further research is needed to examine the role of age on students’ endorsement of punishment goals.

Lastly, it should be mentioned that, regarding the students’ view on the misbehavior and punishment, the results of the present research are limited to the role of an uninvolved observer. By contrast, in many situations of misbehavior, there are several other perspectives involved, such as from perpetrators or victims (Schmitt et al., 2005 ). Therefore, future work will need to examine the students’ perspective on misbehavior and a teacher’s response to it from different perspectives.

In conclusion, the present research is the first to directly compare teachers’ and students’ views on the purposes of punishment in the school context. In light of the findings and the observation that the approach, as a whole, is fruitful, other researchers are strongly encouraged to integrate all perspectives (i.e., the teachers’ and students’ views) on the psychological analysis of teaching and instruction. Finally, we hope the present findings contribute to the development of classroom intervention strategies that may reduce rather than enhance conflicts in student–teacher-interactions.

Availability of Data and Materials

All materials (including instructions and materials of a pretest study; all materials are translated from German to English), along with all data, analyses scripts, and supplementary analyses are available on the OSF: https://osf.io/r5d8v/ .

Code Availability (Software Application or Custom Code)

All analyses code is made available on the OSF.

The names of the students in the scenario were chosen to be gender neutral.

To assess the degree to which the punishment practices served the three punishment goals, we provided participants ( N = 122; convenience sample) of our pre-study with definitions of the goals retribution, special prevention, and general prevention. Participants then rated the degree to which several possible punishment practices achieve these three goals. Additionally, participants rated the severity of the punishment practices to ensure that practices would be comparable in severity (to rule out the common confound between punishment severity and punishment goals; Mooijman & Graham, 2018 ). As a result, we were able to extract three punishment practices (one for each punishment goal) that were perceived as primarily serving one of the goals but not the other two. At the same time, these practices were perceived as approximately equally severe. Full information on the pretest of the punishment practice evaluation measure (including instructions, materials, data, and analyses) can be found on the OSF.

We re-ran all analyses on students’ assessment of the teachers’ punishment practices (i.e., the punishment practice evaluation measure) with the appropriateness item only. This helps comparing students’ and teachers’ relative endorsement of punishment goals as assessed with the punishment practice evaluation measure more directly, given that teachers also provided appropriateness ratings. Importantly, these additional analyses yielded similar results to what we report in the following sections on the compound of the three items used to assess students’ evaluations. We report these additional analyses in the supplementary materials on the OSF.

Aloe, A. M., Shisler, S. M., Norris, B. D., Nickerson, A. B., & Rinker, T. W. (2014). A multivariate meta-analysis of student misbehavior and teacher burnout. Educational Research Review, 12 , 30–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2014.05.003

Article Google Scholar

Applegate, B. K., Cullen, F. T., Turner, M. G., & Sundt, J. L. (1996). Assessing public support for three-strikes-and-you’re-out laws: Global versus specific attitudes. Crime & Delinquency, 42 (4), 517–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128796042004002

Avtgis, T. A., & Rancer, A. S. (2008). The relationship between trait verbal aggressiveness and teacher burnout syndrome in K-12 teachers. Communication Research Reports, 25 (1), 86–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824090701831875

Baudson, T. G., & Preckel, F. (2013). Teachers’ implicit personality theories about the gifted: An experimental approach. School Psychology Quarterly, 28 (1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000011

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bazemore, G. (1998). Restorative justice and earned redemption: Communities, victims, and offender reintegration. American Behavioral Scientist, 41 (6), 768–813. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764298041006003

Bear, G. G., & Fink, A. (1991). Judgments of fairness and predicted effectiveness of classroom discipline: Influence of problem severity and reputation. School Psychology Quarterly, 6 (2), 83–102. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0088810

Bentham, J. (1962). Principles of penal law. In J. Bowring (Ed.), The works of Jeremy Bentham (p. 396). William Tait.

Google Scholar

Boyle, G. J., Borg, M. G., Falzon, J. M., & Baglioni, A. J. J. (1995). A structural model of the dimensions of teacher stress. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 65 (1), 49–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1995.tb01130.x

Braithwaite, J. (1998). Restorative justice. In M. H. Tonry (Ed.), The handbook of crime and punishment (pp. 323–344). Oxford University Press.

Brouwers, A., & Tomic, W. (2000). A longitudinal study of teacher burnout and perceived self-efficacy in classroom management. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16 , 239–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(99)00057-8

Bru, E., Murgberg, T. A., & Stephens, P. (2001). Social support, negative life events and pupil misbehaviour among young Norwegian adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 24 (6), 715–727. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.2001.0434

Bru, E., Stephens, P., & Torsheim, T. (2002). Students’ perceptions of class management and reports of their own misbehavior. Journal of School Psychology, 40 (4), 287–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4405(02)00104-8

Carlsmith, K. M. (2006). The roles of retribution and utility in determining punishment. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42 (4), 437–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2005.06.007

Carlsmith, K. M. (2008). On justifying punishment: The discrepancy between words and actions. Social Justice Research, 21 (2), 119–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-008-0068-x

Carlsmith, K. M., & Darley, J. M. (2008). Psychological aspects of retributive justice. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 40 (07), 193–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(07)00004-4

Carlsmith, K. M., Darley, J. M., & Robinson, P. H. (2002). Why do we punish? Deterrence and just deserts as motives for punishment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83 (2), 284–299. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.83.2.284

Coverdale, H. B. (2020). What makes a response to schoolroom wrongs permissible? Theory and Research in Education, 18 (1), 23–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878520912997

Crockett, M. J., Özdemir, Y., & Fehr, E. (2014). The value of vengeance and the demand for deterrence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143 (6), 2279–2286. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000018

Cushman, F. (2015). Punishment in humans: From intuitions to institutions. Philosophy Compass, 10 (2), 117–133. https://doi.org/10.1111/phc3.12192

Dumont, H., Klinge, D., & Maaz, K. (2019). The many (subtle) ways parents game the system: Mixed-method evidence on the transition into secondary-school tracks in Germany. Sociology of Education, 92 (2), 199–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040719838223

Elliott, S. N., Witt, J. C., Galvin, G. A., & Moe, G. L. (1986). Children’s involvement in intervention selection: Acceptability of interventions for misbehaving peers. Professional Psychology, Research and Practice, 17 (3), 235–241. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.17.3.235

Ertesvåg, S. K., & Vaaland, G. S. (2007). Prevention and reduction of behavioural problems in school: An evaluation of the Respect program. Educational Psychology, 27 (6), 713–736. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410701309258