अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी पर निबंध (Freedom of Speech Essay in Hindi)

अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी भारत के नागरिकों के मौलिक अधिकारों में से एक है। दुनिया भर के कई देश अपने नागरिकों को उनके विचारों और सोच को साझा करने तथा उन्हें सशक्त बनाने के लिए अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी की अनुमति देते हैं। भारत सरकार और अन्य कई देश अपने नागरिकों को अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी प्रदान करते हैं। ऐसा विशेष रूप से जहाँ-जहाँ लोकतांत्रिक सरकार है उन देशों में है।

अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी पर छोटे तथा बड़े निबंध (Short and Long Essay on Freedom of Speech in Hindi, Abhivyakti ki Azadi par Nibandh Hindi mein)

अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी पर निबंध – 1 (250 – 300 शब्द).

दुनिया भर के अधिकांश देशों के नागरिकों को दिए गए मूल अधिकारों में अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी शामिल है। यह अधिकार उन देशों में रहने वाले लोगों को कानून द्वारा दंडित होने के डर के बिना अपने मन की बात करने के लिए सक्षम बनाता है।

अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी की उत्पत्ति

अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी की अवधारणा बहुत पहले ही उत्पन्न हुई थी। इंग्लैंड के विधेयक अधिकार 1689 ने संवैधानिक अधिकार के रूप में अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी को अपनाया और यह अभी भी प्रभाव में है। 1789 में फ्रेंच क्रांति ने मनुष्य और नागरिकों के अधिकारों की घोषणा को अपनाया। इसके साथ ही एक स्वतंत्र नतीजे के रूप में अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी की पुष्टि हुई। अनुच्छेद 11 में अभिव्यक्ति और अभिव्यक्ति की घोषणा कहती है:

“सोच और विचारों का नि:शुल्क संचार मनुष्य के अधिकारों में सबसे अधिक मूल्यवान है। हर नागरिक तदनुसार स्वतंत्रता के साथ बोल सकता है, लिख सकता है तथा अपने शब्द छाप सकता है लेकिन इस स्वतंत्रता के दुरुपयोग के लिए भी वह उसी तरह जिम्मेदार होगा जैसा कि कानून द्वारा परिभाषित किया गया है”।

मानव अधिकारों की सार्वभौमिक घोषणा 1948 में अपनाई गई थी। इस घोषणा के तहत यह भी बताया गया है कि हर किसी को अपने विचारों और राय को अभिव्यक्त करने की स्वतंत्रता होनी चाहिए। अभिव्यक्ति और अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी अब अंतरराष्ट्रीय और क्षेत्रीय मानवाधिकार कानून का एक हिस्सा बन गया हैं।

अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी – लोकतंत्र का आधार

एक लोकतांत्रिक सरकार अपने देश की सरकार को चुनने के अधिकार सहित अपने लोगों को विभिन्न अधिकार देती है। अभिव्यक्ति और अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी एक लोकतांत्रिक राष्ट्र के आधार के रूप में जानी जाती है।

अगर निर्वाचित सरकार शुरू में स्थापित मानकों के मुताबिक प्रदर्शन नहीं कर रही है और नागरिकों को इससे सम्बंधित मुद्दों पर अपनी राय देने का अधिकार नहीं है तो सरकार का चयन ही फायदेमंद नहीं है। यही कारण है कि लोकतांत्रिक राष्ट्रों में अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी का अधिकार एक जरूरी अधिकार है। यह लोकतंत्र का आधार है।

अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी लोगों को अपने विचारों को साझा करने और समाज में सकारात्मक परिवर्तन लाने की शक्ति प्रदान करती है।

इसे यूट्यूब पर देखें : Abhivyakti ki Azadi par Nibandh

Abhivyakti ki Ajadi par Nibandh – निबंध 2 (400 शब्द)

अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी को मूल अधिकार माना जाता है। हर व्यक्ति को यह हक़ मिलना चाहिए। यह भारतीय संविधान द्वारा भारत के नागरिकों को दिए गए सात मौलिक अधिकारों में से एक है। यह स्वतंत्रता के अधिकार का एक हिस्सा है जिसमें अभिव्यक्ति और अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी, जीवन और स्वतंत्रता के अधिकार, आंदोलन की स्वतंत्रता, निवास की स्वतंत्रता, किसी पेशे का अभ्यास करने का अधिकार, संघ या सहकारी समितियों के गठन की स्वतंत्रता, दोषसिद्धि अपराधों में बचाव का अधिकार और कुछ मामलों में गिरफ्तारी के खिलाफ संरक्षण के लिए।

अभिव्यक्ति की ज़रुरत क्यों है ?

नागरिकों के साथ-साथ राष्ट्र के भी पूरे विकास और प्रगति के लिए अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी आवश्यक है। जो व्यक्ति बोलता है या सुनता है उस पर प्रतिबंध लगाकर किसी व्यक्ति के विकास में बाधा उत्पन्न हो सकती है। इससे परेशानी और असंतोष पैदा हो सकता है जिससे तनाव बढ़ जाता है। असंतोष से भरे लोगों की वजह से कोई भी राष्ट्र सही दिशा में कभी नहीं बढ़ सकता।

अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी चर्चाओं को निमंत्रण देती है जो समाज के विकास के लिए आवश्यक विचारों के आदान-प्रदान में मदद करती है। यह देश की राजनीतिक व्यवस्था के बारे में एक राय व्यक्त करने के लिए आवश्यक है। जब सरकार को यह पता चल जाता है कि उसके क़दमों पर निगरानी रखी जा रही है और इसे द्वारा उठाए जा रहे कदमों को चुनौती दी जा सकती है या आलोचना की जा सकती है तब सरकार और अधिक जिम्मेदारी से कार्य करती है।

अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी – दूसरे अधिकारों से संबंधित

अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी अन्य अधिकारों से निकटता से संबंधित है। यह मुख्य रूप से नागरिकों को दिए गए अन्य अधिकारों की रक्षा के लिए आवश्यक है। यह केवल तब होता है जब लोगों को स्वतंत्र रूप से अपने विचार व्यक्त करने और बोलने का अधिकार होता है तो वे गलत होने वाली किसी भी चीज के खिलाफ अपनी आवाज उठा सकते हैं। यह चुनाव प्रक्रिया में शामिल होने की बजाए लोकतंत्र में सक्रिय भाग लेने के लिए सक्षम बनाती है। इस प्रकार वे दूसरे अधिकारों की रक्षा कर सकते हैं। जैसे बराबरी का अधिकार, धर्म के अधिकार की स्वतंत्रता, शोषण के खिलाफ अधिकार और गोपनीयता का अधिकार सिर्फ तभी जब उनके पास अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी और अभिव्यक्ति का अधिकार है।

यह उचित निर्णय के अधिकार से भी निकटता से संबंधित है। अभिव्यक्ति और अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी एक व्यक्ति को एक मुकदमे के दौरान स्वतंत्र रूप से अपनी बात कहने में सक्षम बनाता है जो अत्यंत आवश्यक है।

अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी किसी भी प्रकार के अन्याय के खिलाफ आवाज उठाने की शक्ति देती है। उन देशों की सरकारों को, जो सूचना का अधिकार और अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी पेश करती हैं, नागरिकों की सोच और विचारों का स्वागत करना तथा बदलाव के लिए तैयार रहना चाहिए।

निबंध 3 (500 शब्द)

अभिव्यक्ति और अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी भारत के नागरिकों की गारंटी के मूल अधिकारों में से एक है। यह स्वतंत्रता के अधिकार के तहत आती है जो भारतीय संविधान में शामिल सात मौलिक अधिकारों में से एक है। अन्य अधिकारों में बराबरी का अधिकार, धर्म की स्वतंत्रता का अधिकार, सांस्कृतिक और शैक्षिक अधिकार, गोपनीयता का अधिकार, शोषण के खिलाफ अधिकार और संवैधानिक उपाय के अधिकार शामिल हैं।

भारत में अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी

भारत का संविधान हर नागरिक को स्वतंत्रता की अभिव्यक्ति प्रदान करता है हालांकि कुछ सीमाओं के साथ। इसका मतलब यह है कि लोग स्वतंत्र रूप से दूसरों के बारे में अपने विचारों को व्यक्त कर सकते हैं साथ ही सरकार, राजनीतिक प्रणाली, नीतियों और नौकरशाही के प्रति भी। हालांकि नैतिक आधार, सुरक्षा और उत्तेजना पर अभिव्यक्ति को प्रतिबंधित किया जा सकता है। भारतीय संविधान में स्वतंत्रता के अधिकार के तहत देश के नागरिकों के पास निम्नलिखित अधिकार हैं:

- स्वतंत्रता से बोलने तथा अपनी राय और विचारों को स्वतंत्र रूप से व्यक्त करने की आज़ादी।

- किसी भी हथियार और गोला-बारूद के बिना शांति से इकट्ठे होने की स्वतंत्रता।

- समूहों, यूनियनों और संघों के लिए स्वतंत्रता।

- स्वतंत्र रूप से देश के किसी भी हिस्से में घूमने के लिए।

- देश के किसी भी हिस्से में बसने के लिए स्वतंत्रता।

- किसी पेशे का अभ्यास करने की स्वतंत्रता।

- किसी भी तरह के व्यापार या उद्योग में शामिल होने की स्वतंत्रता बशर्ते वह गैरकानूनी ना हो।

भारत सही अर्थों में एक लोकतांत्रिक देश के रूप में जाना जाता है। यहां के लोगों को सूचना का अधिकार है और सरकार की गतिविधियों पर वे अपनी राय भी दे सकते हैं। अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी मीडिया को उन सभी ख़बरों को साझा करने की शक्ति देती है जो देश में और साथ ही दुनिया भर में चल रही है। यह लोगों को अधिक जागरूक बनाती है और उन्हें दुनिया भर से नवीनतम घटनाओं के साथ जुड़ा हुआ रखती है।

अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी का कमज़ोर पहलू

जहाँ अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी एक व्यक्ति को अपनी राय और विचारों को साझा करने और अपने समाज और साथी नागरिकों की भलाई के लिए योगदान करने का मंच प्रदान करती है वही इसके साथ कई कमज़ोर पहलू भी जुड़े हुए हैं। बहुत से लोग इस स्वतंत्रता का दुरुपयोग करते हैं। वे सिर्फ अपने विचारों को व्यक्त नहीं करते बल्कि दूसरों पर भी उन्हें लागू करते हैं। वे गैरकानूनी गतिविधियां करने के लिए लोगों का समूह बनाते हैं। मीडिया अपने विचारों और राय को व्यक्त करने के लिए भी स्वतंत्र है। कभी-कभी उनके द्वारा साझा की जाने वाली जानकारी आम जनता में आतंक पैदा करती है। अलग-अलग सांप्रदायिक समूहों की गतिविधियों से संबंधित कुछ समाचारों ने भी अतीत में सांप्रदायिक दंगों को जन्म दिया है। इससे समाज की शांति और सद्भाव में बाधा आ गई है।

इंटरनेट ने अभिव्यक्ति और अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी बढ़ा दी है। सोशल मीडिया प्लेटफार्मों के आगमन ने इसे और आगे बढ़ाया है। लोग इन दिनों हर चीज़ पर और सब कुछ पर अपने विचार देने के लिए उत्सुक है चाहे उन्हें इसके बारे में ज्ञान हो या नहीं। वे बिना किसी की भावनाओं की कद्र करते हुए या उनके मान-सम्मान का लिहाज़ करते हुए नफरतपूर्ण टिप्पणियां लिखते हैं। यह निश्चित रूप से इस आजादी का दुरुपयोग कहा जा सकता है और इसे तुरंत बंद होना चाहिए।

प्रत्येक देश को अपने नागरिकों को बोलने और अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी प्रदान करनी चाहिए। हालांकि इसे पहले स्पष्ट रूप से परिभाषित किया जाना चाहिए ताकि यह व्यक्तियों के साथ-साथ समाज में सकारात्मक परिवर्तन लाने में मदद कर सके और यह सामान्य कार्य को बाधित ना करे।

निबंध 4 (600 शब्द)

अधिकांश देश अपने नागरिकों को अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी देते हैं ताकि वे अपने विचारों को साझा कर सकें और अलग-अलग मामलों पर अपनी राय दे सकें। यह एक व्यक्ति के साथ ही समाज के विकास के लिए आवश्यक माना जाता है। जहाँ अधिकतर देशों ने अपने नागरिकों को यह आजादी प्रदान की है वहीँ कई देशों ने इससे दूरी बना रखी है।

कई देश अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी देते हैं

न केवल भारत बल्कि दुनिया के कई देश अपने नागरिकों को अभिव्यक्ति और अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी का अधिकार देते हैं। मानव अधिकारों की संयुक्त राष्ट्र सार्वभौमिक घोषणा वर्ष 1948 में शामिल कथन इस प्रकार है:

“प्रत्येक व्यक्ति को राय और अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी का अधिकार है। इस अधिकार में हस्तक्षेप के बिना अपनी बात रखने की स्वतंत्रता और किसी भी मीडिया के माध्यम से सूचनाओं और विचारों को तलाशने और प्राप्त करने के लिए स्वतंत्रता शामिल है।”

दक्षिण अफ्रीका, सूडान, पाकिस्तान, ट्यूनीशिया, हांगकांग, ईरान, इज़राइल, मलेशिया, जापान, फिलीपींस, दक्षिण कोरिया, सऊदी अरब, संयुक्त अरब अमीरात, थाईलैंड, न्यूजीलैंड, यूरोप, डेनमार्क, फिनलैंड और चीन कुछ ऐसे देशों में से हैं जो अपने नागरिकों को अभिव्यक्ति देने और अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी प्रदान करते हैं।

एक तरफ तो इन देशों ने अपने नागरिकों को अभिव्यक्ति और अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी का अधिकार दिया है वही दूसरी तरफ ये अधिकार किस हद तक जनता और मीडिया को प्रदान किए गए है, यह हर देश के हिसाब से अलग-अलग है।

जिन देशों में अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी नहीं है

ऐसे कई देश हैं जो अपने नागरिकों को पूर्ण नियंत्रण बनाए रखने के लिए अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी का अधिकार नहीं देते हैं। यहां इनमें से कुछ देशों पर एक नजर डाली गई है:

- उत्तर कोरिया: यह देश अपने नागरिकों के साथ-साथ अपनी मीडिया को भी अभिव्यक्ति और अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी प्रदान नहीं करता है। इस प्रकार सरकार न केवल लोगों के विचारों और राय को अभिव्यक्त करने की स्वतंत्रता नहीं देती बल्कि इसके नागरिकों की जानकारी भी रखती है।

- सीरिया: सीरिया की सरकार अपने आतंकवाद के लिए जानी जाती है। यहां के लोग अपने मूल मानवीय अधिकार, जो स्वतंत्रता व अभिव्यक्ति और अभिव्यक्ति का अधिकार है, से वंचित हैं।

- 3 . क्यूबा: क्यूबा एक और देश है जो अपने नागरिकों को अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी प्रदान नहीं करता है। क्यूबा के नागरिकों को सरकार या किसी भी राजनीतिक दल की गतिविधियों पर कोई नकारात्मक टिप्पणी देने की अनुमति नहीं है। यहां पर सरकार ने इंटरनेट उपयोग पर भी प्रतिबंध लगा रखा है ताकि लोगों को इसके माध्यम से कुछ भी व्यक्त करने का मौका न मिले।

- बेलारूस: यह एक ऐसा देश है जो बोलने और अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी प्रदान नहीं करता है। लोग अपनी राय बता नहीं सकते या सरकार के काम की आलोचना नहीं कर सकते। बेलारूस में सरकार या किसी राजनीतिक मंत्री की आलोचना करना कानूनन अपराध है।

- ईरान: ईरान के नागरिकों को यह पता नहीं है कि अपनी राय व्यक्त करने और जनता के बीच अपने विचारों को स्वतंत्र रूप से साझा करना कैसा होता है। कोई भी ईरानी नागरिक सार्वजनिक कानूनों या इस्लामी मानकों के खिलाफ किसी भी तरह का असंतोष व्यक्त नहीं कर सकता।

- बर्माः बर्मा की सरकार का मत है कि अभिव्यक्ति और अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी अनावश्यक है। नागरिकों से कहा जाता है कि वे अपने विचार या राय को व्यक्त न करें खासकर यदि वह किसी नेता या राजनीतिक दल के खिलाफ हैं। बर्मा में मीडिया का संचालन सरकार द्वारा किया जाता है।

- लीबिया: इस देश के अधिकांश लोग यह नहीं जानते हैं कि अभिव्यक्ति और अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी वास्तव में क्या है। लीबिया की सरकार अपने नागरिकों पर अत्याचार करने के लिए जानी जाती है। इंटरनेट के ज़माने में दुनिया भर के लोग किसी भी मामले पर अपने विचार व्यक्त करने के लिए स्वतंत्र हैं लेकिन इस देश में नहीं। इंटरनेट पर सरकार की आलोचना के लिए लीबिया में कई लोगों को गिरफ्तार किया गया है।

अभिव्यक्ति और अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी एक मूल मानव अधिकार है जो प्रत्येक देश के नागरिकों को दी जानी चाहिए। यह देखना बहुत दुखदाई है कि किस प्रकार कुछ देशों की सरकार अपने नागरिकों को ये आवश्यक मानव अधिकार भी प्रदान नहीं करती है और अपने स्वयं के स्वार्थी उद्देश्यों को पूरा करने के लिए उनका दमन करती है।

संबंधित पोस्ट

मेरी रुचि पर निबंध (My Hobby Essay in Hindi)

धन पर निबंध (Money Essay in Hindi)

समाचार पत्र पर निबंध (Newspaper Essay in Hindi)

मेरा स्कूल पर निबंध (My School Essay in Hindi)

शिक्षा का महत्व पर निबंध (Importance of Education Essay in Hindi)

बाघ पर निबंध (Tiger Essay in Hindi)

Leave a comment.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Hindi Law Blog

- constitution of India 1950

- Freedom of Speech and Expression

फ्रीडम ऑफ स्पीच एंड एक्सप्रेशन अंडर द कंस्टीट्यूशन ऑफ़ इंडिया (वाक् और अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता के मुख्य तत्व)

यह लेख इंदौर इंस्टीट्यूट ऑफ लॉ, इंदौर के छात्र Aditya Dubey ने लिखा है। इस लेख में लेखक ने भारत के संविधान के तहत परिभाषित अभिव्यक्ति और अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता (फ्रीडम ऑफ एक्सप्रेशन) की अवधारणा के साथ-साथ इसके महत्व और उन आधारों पर चर्चा की है जिन पर भारत सरकार द्वारा इसे प्रतिबंधित किया जा सकता है। इस लेख का अनुवाद Revati Magaonkar ने किया है।

Table of Contents

परिचय (इंट्रोडक्शन)

भाषण और अभिव्यक्ति (फ्रीडम ऑफ स्पीच एंड एक्सप्रेशन) की स्वतंत्रता को भारत के संविधान के अनुच्छेद 19(1)(a) के तहत परिभाषित किया गया है जिसमें कहा गया है कि भारत के सभी नागरिकों को भाषण और अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता का अधिकार है। इस अनुच्छेद के पीछे का दर्शन भारत के संविधान की प्रस्तावना (प्रिएंबल) में दिया गया है- ‘जहां अपने सभी नागरिकों को उनके विचार और अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता को सुरक्षित करने के लिए एक गंभीर संकल्प किया जाता है। हालाँकि, इस अधिकार का प्रयोग भारत के संविधान के अनुच्छेद 19 (2) के तहत लगाए गए कुछ उद्देश्यों के लिए उचित प्रतिबंधों (संक्शन्स) के अधीन है।

भाषण और अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता के मुख्य तत्व क्या हैं (व्हाट आर द मैन एलीमेंट्स ऑफ़ स्पीच एंड एक्सप्रेशन)

ये वाक्/बोलने और अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता के निम्नलिखित आवश्यक तत्व हैं:

- यह अधिकार पूरी तरह से भारत के एक नागरिक के लिए उपलब्ध है, न कि अन्य देशों के व्यक्तियों यानी विदेशी नागरिकों के लिए।

- अनुच्छेद 19(1)(a) के तहत बोलने की स्वतंत्रता में किसी भी तरह के मुद्दे के बारे में अपने विचार और राय व्यक्त करने का अधिकार शामिल है और इसे किसी भी तरह के माध्यम से किया जा सकता है, जैसे मुंह के शब्दों से, लिखकर, छपाई द्वारा, चित्रांकन (पोर्ट्रेचर) के माध्यम से या किसी फिल्म के माध्यम से किया जा सकता है।

- यह अधिकार सम्पूर्ण रूप से नहीं है क्योंकि यह भारत सरकार को ऐसे कानून बनाने की अनुमति देता है जो भारत की संप्रभुता और अखंडता (सोवर्गिनिटी एंड इंटिग्रिटी) या राज्य की सुरक्षा, या विदेशी राष्ट्रों के साथ मैत्रीपूर्ण संबंधों (फ्रैंडली रिलेशन), शालीनता और नैतिकता (डीसेंसी एंड मोरालीटी) और अदालत की अवमानना (कंटेंप्ट ऑफ़ कोर्ट), मानहानि और अपराध के लिए उकसाना यहां तक कि सार्वजनिक व्यवस्था (पब्लिक आर्डर) से जुड़े मामलों में उचित प्रतिबंध लगा सकते हैं।

- किसी भी नागरिक की अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता पर इस तरह का प्रतिबंध राज्य की कार्रवाई से उतना ही लगाया जा सकता है जितना कि उसकी निष्क्रियता (इनेक्शन) से लगाया जा सकता है। इस प्रकार, यदि राज्य की ओर से अपने सभी नागरिकों को वाक् और अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता के मौलिक अधिकार (फंडामेंटल राइट) की गारंटी देने में विफलता पाई जाती है, तो यह भी अनुच्छेद 19 (1) (a) का उल्लंघन होगा।

अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता कैसे महत्वपूर्ण है (हाउ इज फ्रीडम ऑफ एक्सप्रेशन इज इंपॉर्टेंट)

भारत जैसे लोकतंत्र (डेमोक्रेटिक) में, भाषण और अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता की अवधारणा (एक्रीडिटेशन) मुद्दों की स्वतंत्र चर्चा के द्वार खोलती है। भाषण की स्वतंत्रता पूरे देश में सामाजिक, आर्थिक और राजनीतिक मामलों पर जनमत के बनाने और प्रदर्शन में बहुत महत्वपूर्ण भूमिका निभाती है। यह अपने दायरे के भीतर, विचारों के प्रसार और आदान-प्रदान से संबंधित स्वतंत्रता, सूचना के प्रसार को सुनिश्चित करता है, जो बाद में, कुछ मुद्दों पर उनके दृष्टिकोण (पॉइंट ऑफ व्यू) के साथ-साथ किसी की राय बनाने में मदद करता है और उन मामलों पर बहस को जन्म देता है जिनमें जनता शामिल होती है। जब तक अभिव्यक्ति राष्ट्रवाद, देशभक्ति और राष्ट्र प्रेम तक सीमित है, तब तक राष्ट्रीय ध्वज का उन भावनाओं की अभिव्यक्ति के रूप में उपयोग एक मौलिक अधिकार होगा।

भारत की स्वतंत्र न्यायपालिका ने माना है और कहा है कि यह एक राय है कि किसी भी जानकारी को प्राप्त करने का अधिकार भाषण और अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता के अधिकार का एक और हिस्सा है और किसी भी प्रकार के हस्तक्षेप (इंटरफेरेंस) के बिना किसी भी प्रकार की जानकारी को संप्रेषित (ट्रांसमिट) करने और प्राप्त करने का अधिकार एक महत्वपूर्ण है। इस अधिकार का पहलू ऐसा इसलिए है, क्योंकि कोई व्यक्ति पर्याप्त जानकारी प्राप्त किए बिना एक सूचित राय नहीं बना सकता है, या एक सूचित विकल्प (ऑप्शन) नहीं बना सकता है और सामाजिक, राजनीतिक या सांस्कृतिक (कल्चरल) रूप से प्रभावी ढंग से भाग ले सकता है।

देश के किसी भी नागरिक को किसी भी प्रकार की सूचना प्रसारित करने के लिए प्रिंट माध्यम एक शक्तिशाली उपकरण है। इस प्रकार, संविधान के तहत किसी व्यक्ति के भाषण और अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता के अधिकार की संतुष्टि के लिए मुद्रित सामग्री (प्रिंटेड मटेरियल) तक पहुंचना बहुत महत्वपूर्ण है। यदि राज्य की ओर से वैकल्पिक सुलभ प्रारूपों (अल्टरनेटिव फॉर्मेट) में सामग्री के प्रिंट हानि वाले लोगों तक पहुंच को सक्षम करने के लिए विधायी प्रावधान (लेजिस्लेटिव प्रोविजन) करने में कोई विफलता पाई जाती है, तो यह भाषण और अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता के अधिकार से वंचित होगा और इस तरह की निष्क्रियता राज्य (इनएक्टिवीटी स्टेट ) संविधान (कंस्टीट्यूशन) के गलत स्थान पर गिर जाएगा। यह सुनिश्चित करना राज्य की ओर से एक दायित्व है कि कानून में पर्याप्त प्रावधान किए गए हैं जो प्रिंट हानि वाले लोगों को सुलभ प्रारूपों में मुद्रित सामग्री तक पहुंचने में सक्षम बनाता है।

अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता के तहत प्रेस की स्वतंत्रता की कोई अलग गारंटी नहीं है क्योंकि यह पहले से ही अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता में शामिल है, जो देश के सभी नागरिकों को दी जाती है।

प्रेस की स्वतंत्रता का क्या अर्थ है (व्हाट इज मींट बाय फ्रीडम ऑफ प्रेस)

भारत के संविधान में कहीं भी प्रेस की स्वतंत्रता का उल्लेख नहीं है। हालाँकि, यह संविधान के अनुच्छेद 19 के तहत निर्धारित भाषण और अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता (हालांकि सीधे व्यक्त नहीं) के अर्थ के तहत एक अधिकार के रूप में मौजूद है। यदि लोकतंत्र का अर्थ यह है कि सरकार देश की जनता की है, जनता की है और जनता के लिए है, तो यह आवश्यक है कि प्रत्येक नागरिक को राष्ट्र की लोकतांत्रिक प्रक्रिया (डेमोक्रेटिक प्रोसेस) में सक्रिय रूप से भाग लेने का अधिकार हो। स्वतंत्र प्रेस के बिना कुछ मामलों पर मुक्त बहस और खुली चर्चा संभव नहीं है।

प्रेस की स्वतंत्रता में लोकतंत्र का एक स्तंभ शामिल है और वास्तव में यह लोकतांत्रिक संगठन की नींव पर बना हुआ है। भारत के सर्वोच्च न्यायालय द्वारा कई निर्णयों में यह माना गया है कि प्रेस की स्वतंत्रता भाषण और अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता का एक हिस्सा है और भारत के संविधान के अनुच्छेद 19 (1) (a) के तहत कवर किया गया है, इसका कारण यह है कि प्रेस की स्वतंत्रता और कुछ नहीं बल्कि भाषण और अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता का एक पहलू है। इसलिए, यह ठीक ही समझा गया है कि प्रेस यह लोगों के विचारों को सभी तक पहुँचाने के लिए एक माध्यम माना जाता है और फिर भी इसे उन सीमाओं से जुड़े रहना पड़ता है जो संविधान द्वारा अनुच्छेद 19 (2) के तहत उन पर थोपी गई हैं।

मामला (केस)

इंडियन एक्सप्रेस न्यूजपेपर्स (बॉम्बे) प्राइवेट लिमिटेड बनाम यूनियन ऑफ इंडिया.

इस मामले में यह देखने के बाद स्थापित किया गया था कि “प्रेस की स्वतंत्रता” शब्द का प्रयोग अनुच्छेद 19 के परिभाषा के तहत नहीं किया गया है, लेकिन यह भारत के संविधान के अनुच्छेद 19 (1) (ए) के भीतर इसके सार के रूप में दिया गया है, और इसलिए, प्रेस की स्वतंत्रता में कोई हस्तक्षेप (इंटर्फियरांस) नहीं हो सकता है जिसमें जनहित और सुरक्षा शामिल है। इसलिए, यह निष्कर्ष निकाला गया कि किसी पत्रिका (मैगज़ीन) के सेंसरशिप को लागू करना या किसी समाचार पत्र को किसी भी मुद्दे के बारे में अपने विचारों को प्रकाशित करने से रोकना जिसमें जनहित शामिल है, ऐसा कृत्य प्रेस की स्वतंत्रता पर प्रतिबंध होगा।

वे कौन से आधार हैं जिन पर इस स्वतंत्रता को प्रतिबंधित किया जा सकता है (व्हाट आर द ग्राउंड्स ऑन व्हिच धिस फ्रीडम कैन बी रेस्ट्रिक्टेड)

ऐसे कई आधार हैं जिन पर राज्य द्वारा कुछ उचित प्रतिबंधों तक भाषण और अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता को प्रतिबंधित किया जा सकता है। इस तरह के प्रतिबंधों को भारत के संविधान के अनुच्छेद 19 के खंड (क्लॉज) (2) के तहत परिभाषित किया गया है जो निम्नलिखित के तहत स्वतंत्र भाषण पर कुछ प्रतिबंध लगाता है:

- राज्य की सुरक्षा

- विदेशी राज्यों के साथ मैत्रीपूर्ण संबंध

- सार्वजनिक व्यवस्था

- शालीनता और नैतिकता

- न्यायालय की अवमानना

- किसी अपराध के लिए उकसाना, और

- भारत की संप्रभुता और अखंडता।

राज्य की सुरक्षा (सिक्युरिटी ऑफ़ स्टेट)

राज्य की सुरक्षा से जुड़े वर्गों में भाषण और अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता पर कुछ उचित प्रतिबंध (रिस्ट्रिक्शन) लगाए जा सकते हैं। ‘राज्य की सुरक्षा’ शब्द को ‘सार्वजनिक व्यवस्था’ शब्द से अलग करने की आवश्यकता है क्योंकि वे समान हैं लेकिन उनकी तीव्रता (इंटेंसिटी) के मामले कई और भिन्न हैं। इसलिए, राज्य की सुरक्षा सार्वजनिक अव्यवस्था (पब्लिक डिसऑर्डर) के गंभीर रूपों को बताती है, इसका एक उदाहरण विद्रोह (रेबेलियन) हो सकता है, जैसे कि राज्य के खिलाफ युद्ध छेड़ना, भले ही वह राज्य के एक हिस्से के खिलाफ हो, आदि।

केस : पीपुल्स यूनियन फॉर सिविल लिबर्टीज (पीयूसीएल) बनाम यूनियन ऑफ इंडिया (एआईआर 1997 एससी 568)

यह मामला , देश में हो रहे टेलीफोन टैपिंग के लगातार मामलों के खिलाफ पीयूसीएल द्वारा भारत के संविधान के अनुच्छेद 32 के तहत जनहित याचिका (पीआईएल) दायर की गई थी और इस प्रकार भारतीय टेलीग्राफ अधिनियम, 1885 की धारा 5(2) की वैधता को चुनौती दी गई। तब यह देखा गया कि “सार्वजनिक आपातकाल की घटना” और “सार्वजनिक सुरक्षा के हित में” धारा 5(2) के तहत दिए गए प्रावधानों (प्रोविजन) के आवेदन के लिए एक अनिवार्य शर्त है। यदि इन दोनों में से कोई भी शर्त मामले से अनुपस्थित है, तो भारत सरकार को इस धारा के तहत अपनी शक्ति का प्रयोग करने का कोई अधिकार नहीं है। इसलिए, टेलीफोन टैपिंग अनुच्छेद 19(1)(a) का उल्लंघन होगा जब तक कि यह अनुच्छेद 19(2) के तहत उचित प्रतिबंधों के आधार पर नहीं आता है।

विदेशी राज्यों के साथ मैत्रीपूर्ण संबंध (फ्रैंडली रिलेशन विथ फोरेन स्टेटस्)

प्रतिबंध के लिए यह आधार 1951 के संविधान (प्रथम संशोधन) अधिनियम द्वारा जोड़ा गया था। राज्य को बोलने और अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता पर उचित प्रतिबंध लगाने का अधिकार है यदि यह अन्य राज्यों के साथ भारत के मैत्रीपूर्ण संबंधों को नकारात्मक (नेगेटिव) रूप से प्रभावित कर रहा है।

सार्वजनिक व्यवस्था (पब्लिक ऑर्डर)

प्रतिबंध के लिए यह आधार संविधान (प्रथम संशोधन) अधिनियम, 1951 द्वारा भी जोड़ा गया था, यह रोमेश थापर बनाम मद्रास राज्य (AIR 1950 SC 124) के मामले में सर्वोच्च न्यायालय के निर्णय से उत्पन्न स्थिति को पूरा करने के लिए किया गया था। भारत के सर्वोच्च न्यायालय के अनुसार, सार्वजनिक व्यवस्था कानून, व्यवस्था और राज्य की सुरक्षा से बहुत अलग है। ‘सार्वजनिक व्यवस्था’ शब्द सार्वजनिक शांति, सार्वजनिक सुरक्षा और शांति की भावना को दर्शाता है। जो कुछ भी सार्वजनिक शांति को भंग करता है, बदले में, जनता को परेशान करता है। लेकिन सिर्फ सरकार की आलोचना (क्रिटिसिजम) से लोक व्यवस्था (पब्लिक ऑर्डर) भंग नहीं हो जाती। एक कानून जो किसी भी वर्ग की धार्मिक भावनाओं को दुखाता है, उसे सार्वजनिक व्यवस्था बनाए रखने के उद्देश्य से वैध (वेलिड) और उचित प्रतिबंध माना गया है।

शालीनता और नैतिकता (डिसेंसी एंड मोरालिटी)

इन्हें भारतीय दंड संहिता 1860 (इंडियन पीनल कोड) की धारा 292 से 294 के तहत परिभाषित किया गया है, जो शालीनता और नैतिकता के आधार पर भाषण और अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता पर प्रतिबंध के उदाहरण बताता है, और यह अश्लील शब्दों (ऑब्सेंस वर्ड्स) की बिक्री या वितरण या प्रदर्शन (डिलीवरी ऑर डिस्प्ले) को प्रतिबंधित करता है।

न्यायालय की अवमानना (कंटेंप्ट ऑफ़ कोर्ट)

अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता का अधिकार किसी भी तरह से किसी व्यक्ति को अदालतों की अवमानना करने की अनुमति नहीं देता है। अदालत की अवमानना की अभिव्यक्ति को न्यायालय की अवमानना अधिनियम, 1971 की धारा 2 के तहत परिभाषित किया गया है। ‘अदालत की अवमानना’ शब्द अधिनियम के तहत दीवानी अवमानना (सिविल कंटेंप्ट) या आपराधिक अवमानना (क्रिमिनल कंटेंप्ट) से संबंधित है।

मानहानि (डिफेमेशन)

भारत के संविधान के अनुच्छेद 19 का खंड (2) किसी भी व्यक्ति को ऐसा बयान देने से रोकता है जिससे समाज की नजर में दूसरे की प्रतिष्ठा को ठेस पहुंचे। मानहानि भारत में एक गंभीर अपराध है और इसे भारतीय दंड संहिता की धारा 499 और 500 के तहत परिभाषित किया गया है। अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता का अधिकार अनिवार्य (मंडेटरी) रूप से पूर्ण नहीं है। इसका मतलब किसी अन्य व्यक्ति की प्रतिष्ठा को ठेस पहुंचाने की आजादी नहीं है (जो संविधान के अनुच्छेद 21 के तहत संरक्षित है)। हालांकि ‘सत्य’ को मानहानि के खिलाफ बचाव माना जाता है, लेकिन बचाव तभी मदद करेगा जब ‘बयान (स्टेटमेंट) जनता की भलाई के लिए’ दिया गया हो और यह स्वतंत्र न्यायपालिका (इंडिपेंडेंट ज्यूडिशियरी) द्वारा मूल्यांकन (एवालूएशन) किए जाने वाले तथ्य (फैक्ट) का सवाल है।

अपराध के लिए उकसाना (इनसाइटमेंट टू एन ऑफेंस)

यह एक और आधार है जिसे 1951 के संविधान (प्रथम संशोधन) अधिनियम द्वारा भी जोड़ा गया था। संविधान किसी व्यक्ति को ऐसा कोई भी बयान देने से रोकता है जो अन्य लोगों को अपराध करने के लिए उकसाता है या प्रोत्साहित करता है।

भारत की संप्रभुता और अखंडता (सोवर्गीनिटी एंड इंटिग्रिटी ऑफ़ इंडिया)

इस आधार को बाद में 1963 के संविधान (सोलहवां संशोधन) अधिनियम द्वारा जोड़ा गया था। इसका उद्देश्य केवल किसी को भी ऐसे बयान देने से रोकना या प्रतिबंधित करना है जो देश की अखंडता और संप्रभुता को सीधे चुनौती देते हैं।

निष्कर्ष (कंक्लूज़न)

भाषण के माध्यम से किसी की राय व्यक्त करना भारत के संविधान द्वारा गारंटीकृत मूल अधिकारों में से एक है और आधुनिक (मॉडर्न) संदर्भ में, भाषण और अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता का अधिकार केवल शब्दों के माध्यम से अपने विचारों को व्यक्त करने तक ही सीमित नहीं है बल्कि इसमें लेखन के संदर्भ (रेफरेंस) में, या दृश्य-श्रव्य (ऑडियो विजुअल) के माध्यम से, या संचार (कम्युनिकेशन) के किसी अन्य तरीके के माध्यम से विचार उन लोगों का प्रसार भी शामिल है। इस अधिकार में प्रेस की स्वतंत्रता का अधिकार, सूचना का अधिकार आदि भी शामिल है। इसलिए इस लेख से यह निष्कर्ष निकाला जा सकता है कि एक लोकतांत्रिक राज्य के समुचित कार्य (प्रॉपर फंक्शनिंग) के लिए स्वतंत्रता की अवधारणा बहुत आवश्यक है।

भारत के संविधान के अनुच्छेद 19 के तहत बताए गए “सार्वजनिक व्यवस्था के हित में” और “उचित प्रतिबंध” शब्दों का उपयोग यह इंगित (पॉइंट) करने के लिए किया जाता है कि इस धारा के तहत प्रदान किए गए अधिकार पूर्ण नहीं हैं और उन्हें अन्य लोगों की सुरक्षा राष्ट्र की और सार्वजनिक व्यवस्था और शालीनता बनाए रखने के लिए के लिए प्रतिबंधित किया जा सकता है।

संबंधित लेख लेखक से और अधिक

कंपनी अधिनियम 2013 की धारा 137, सिद्धाराजू बनाम कर्नाटक राज्य (2020) और (2021), केरल राज्य बनाम एन.एम.थॉमस (1976), कोई जवाब दें जवाब कैंसिल करें.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

EDITOR PICKS

Popular posts, popular category.

- Law Notes 1784

- Indian Penal Code 1860 267

- constitution of India 1950 265

- General 229

- Code of Criminal Procedure 143

- Indian Contract Act 1872 131

- Code of Civil Procedure1908 102

iPleaders consists of a team of lawyers hell-bent on figuring out ways to make law more accessible. While the lack of access to affordable and timely legal support cuts across all sectors, classes and people in India, where it is missed most, surprisingly, are business situations.

Contact us: [email protected]

© Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

- UP News Today Live

- Ebrahim Raisi

- CM ममता पर अभद्र बयान मामला

- 5th Phase Voting

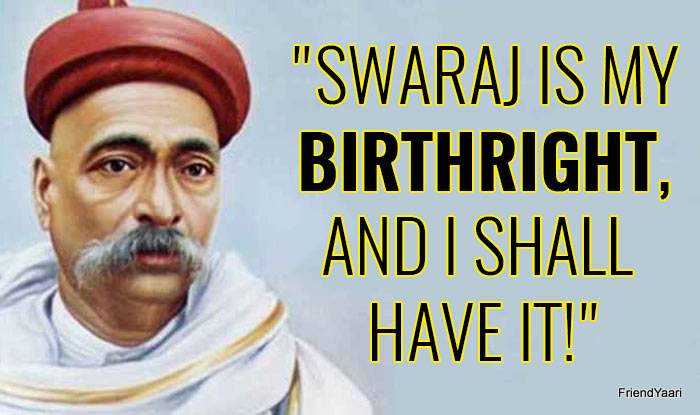

5 Famous Speeches: सुभाष के तुम मुझे खून दो… से गांधी के करो या मरो तक, स्वतंत्रता संग्राम के पांच यादगार भाषण

स्वतंत्रता के 75वें वर्ष के मौके पर अमर उजाला आपको उन पांच भाषणों के बारे में बता रहा है जिन्होंने आजादी की लड़ाई में गहरी छाप छोड़ी। आइये जानते हैं उन भाषणों को....

Link Copied

विस्तार .vistaar {display: flex; flex-direction: row; justify-content: space-between; align-items: center;} .vistaar .followGoogleNews {display:flex;align-items:center;justify-content:center;font-size:14px;line-height:15px;color:#424242; padding:3px 7px 3px 12px;border:1px solid #D2D2D2;border-radius:50px} .vistaar .followGoogleNews a {display:inline-flex;justify-content:center;align-items:center} .vistaar .followGoogleNews span{margin:0 5px} @media only screen and (max-width:320px){ .vistaar .followGoogleNews {font-size:11px;padding:3px 2px 3px 7px} } Follow Us

रहें हर खबर से अपडेट, डाउनलोड करें Android Hindi News apps , iOS Hindi News apps और Amarujala Hindi News apps अपने मोबाइल पे| Get all India News in Hindi related to live update of politics, sports, entertainment, technology and education etc. Stay updated with us for all breaking news from India News and more news in Hindi .

एड फ्री अनुभव के लिए अमर उजाला प्रीमियम सब्सक्राइब करें

Next Article

Please wait...

अपना शहर चुनें

Today's e-Paper

News from indian states.

- Uttar Pradesh News

- Himachal Pradesh News

- Uttarakhand News

- Haryana News

- Jammu And Kashmir News

- Rajasthan News

- Jharkhand News

- Chhattisgarh News

- Gujarat News

- Health News

- Fitness News

- Fashion News

- Spirituality

- Daily Horoscope

- Astrology Predictions

- Astrologers

- Astrology Services

- Age Calculator

- BMI Calculator

- Income Tax Calculator

- Personal Loan EMI Calculator

- Car Loan EMI Calculator

- Home Loan EMI Calculator

Entertainment News

- Bollywood News

- Hollywood News

- Movie Reviews

- Photo Gallery

- Hindi Jokes

Sports News

- Cricket News

- Live Cricket Score

Latest News

- Technology News

- Car Reviews

- Mobile Apps

- Sarkari Naukri

- Sarkari Result

- Career Plus

- Business News

- Europe News

Trending News

- UP Board Result

- HP Board Result

- UK Board Result

- Utility News

- Bizarre News

- Special Stories

Other Properties:

- My Result Plus

- SSC Coaching

- Gaon Junction

- Advertise with us

- Cookies Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Products and Services

- Code of Ethics

Delete All Cookies

फॉन्ट साइज चुनने की सुविधा केवल एप पर उपलब्ध है

अमर उजाला एप इंस्टॉल कर रजिस्टर करें और 100 कॉइन्स पाएं, केवल नए रजिस्ट्रेशन पर, अब मिलेगी लेटेस्ट, ट्रेंडिंग और ब्रेकिंग न्यूज आपके व्हाट्सएप पर.

सभी नौकरियों के बारे में जानने के लिए अभी डाउनलोड करें अमर उजाला ऐप

क्षमा करें यह सर्विस उपलब्ध नहीं है कृपया किसी और माध्यम से लॉगिन करने की कोशिश करें

भारत के संविधान का अनुच्छेद-19 (भाषण और अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता) |Article-19 (Freedom of Speech and Expression)

आज हम लिखित अथवा मौखिक रूप से प्रकट की गयी अभियुक्त की स्वतंत्रता के सम्बन्ध मे सम्पूर्ण जानकारी आपके साथ साझा करेंगे। इसके अलावा किसी व्यक्ति को अपनी बात प्रकट करने की क्या स्वतंत्रता हमारे भारत के संविधान मे दिया गया है, यह भी जानकारी देंगे। भाषण एवंम् अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता (Freedom of Speech and Expression) के बारे मे सम्पूर्ण जानकारी इस लेख के माध्यम जानेंगें। किसी व्यक्ति को अपनी बात लिखित या मौखिक रूप से समाज के समक्ष रखने के कुछ नियम एवंम् सयंम होते है, जिसके तहत वह अपने कथन को समाज के प्रति रखा जा सकता है, जिसे हमारे संविधान मे अनुच्छेद-19 (Article-19) मे परिभाषित किया गया है।

संविधान के भाग 3 में मौलिक अधिकारों का वर्णन किया गया है ये अधिकार प्रत्येक नागरिक के विकास के लिए बेहद जरूरी है, Article-19 , को भी मौलिक अधिकार की श्रेणी में रखा गया है। आज हम इस लेख में अनुच्छेद 19 में वर्णित विभिन्न प्रकार के मौलिक अधिकार के बारे में भी जानेंगे साथ ही, इनका क्या अर्थ होता है, यह स्पष्ट करेंगे। आखिर आर्टिकल 19 क्या है। What is Article 19 (Freedom of Speech and Expression) in Hindi.

आर्टिकल-19 मे प्रत्येक व्यक्ति अपनी लिखित एवंम् मौखिक बात रखने के लिये भारत के संविधान मे अधिकारों को परिभाषित किया गया है। भाषण एवंम् अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता प्रत्येक व्यक्ति का मौलिक अधिकार होता है। यह अधिकार आम नागरिक एवंम् पत्रकारिता/प्रेस के विचारो को प्रकट करने की स्वतंत्रता पर भी आधारित है।

आर्टिकल 19 क्या है ? (What is Article 19 )

भारत के संविधान के अनुच्छेद 19 के तहत लिखित और मौखिक रूप से अपना मत प्रकट करने हेतु अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता के अधिकार का प्रावधान किया गया है, किंतु अभियक्ति की स्वतंत्रता का अधिकार निरपेक्ष नहीं है इस पर युक्तियुक्त निर्बंधन हैं। भारत की एकता, अखंडता एवं संप्रभुता पर खतरे की स्थिति में, वैदेशिक संबंधों पर प्रतिकूल प्रभाव की स्थिति में, न्यायालय की अवमानना की स्थिति में इस अधिकार को बाधित किया जा सकता है। भारत के सभी नागरिकों को विचार करने, भाषण देने और अपने व अन्य व्यक्तियों के विचारों के प्रचार की स्वतंत्रता प्राप्त है। प्रेस/पत्रकारिता भी विचारों के प्रचार का एक साधन ही है इसलिये अनुच्छेद 19 में प्रेस की स्वतंत्रता भी सम्मिलित है।

अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता (freedom of expression) या बोलने की स्वतंत्रता (freedom of speech) किसी व्यक्ति या समुदाय द्वारा अपने मत और विचार को बिना प्रतिशोध, अभिवेचन या दंड के डर के प्रकट कर पाने की स्थिति होती है। इस स्वतंत्रता को सरकारें, जनसंचार कम्पनियाँ, और अन्य संस्थाएँ बाधित कर सकती हैं। इसलिये यह अधिकार प्रत्येक व्यक्ति का मौलिक अधिकार माना गया है। अनुच्छेद 19 में प्रयुक्त ‘अभिव्यक्ति’ शब्द इसके क्षेत्र को बहुत विस्तृत कर देता है। विचारों के व्यक्त करने के जितने भी माध्यम हैं जैसे लिखित अथवा मौखिक वे अभिव्यक्ति, पदावली के अन्तर्गत आ जाते हैं। इस प्रकार अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता में प्रेस की स्वतन्त्रता भी सम्मिलित है। विचारों का स्वतन्त्र प्रसारण ही इस स्वतन्त्रता का मुख्य उद्देश्य है। यह भाषण द्वारा या समाचार-पत्रों द्वारा किया जा सकता है। अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता में किसी व्यक्ति के विचारों को किसी ऐसे माध्यम से अभिव्यक्त करना सम्मिलित है जिससे वह दूसरों तक उन्हे संप्रेषित(Communicate) कर सके। इस प्रकार इनमें संकेतों, अंकों, चिह्नों तथा ऐसी ही अन्य क्रियाओं द्वारा किसी व्यक्ति के विचारों की अभिव्यक्ति सम्मिलित है।

संविधान के अनुच्छेद 19 में 6 तरह की स्वतंत्रताओं का उल्लेख है जो निम्न है – संविधान के अनुच्छेद 19 में 6 तरह की स्वतंत्रताओं के बारे में एक एक करके हम देखने का प्रयास करते हैं।

अनुच्छेद-19 ( Indian Constitution Article 19)

“Protection of certain rights regarding freedom of speech, etc”– All citizens shall have the right- (a) to freedom of speech and expression; (b) to assemble peaceably and without arms; (c) to form associations or unions 2[or co-operative societies]; (d) to move freely throughout the territory of India; (e) to reside and settle in any part of the territory of India; 3[and] (g) to practise any profession, or to carry on any occupation, trade or business. “भाषण की स्वतंत्रता आदि के संबंध में कतिपय अधिकारों का संरक्षण”- सभी नागरिकों को अधिकार होगा- (क) भाषण और अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता के लिए; (ख) शांतिपूर्वक और हथियारों के बिना इकट्ठा होने के लिए; (ग) संघों या यूनियनों 2 [या सहकारी समितियों] बनाने के लिए; (घ) भारत के पूरे क्षेत्र में स्वतंत्र रूप से स्थानांतरित करने के लिए; (ड़) भारत के क्षेत्र के किसी भी हिस्से में रहने और बसने के लिए; 3 [और] (छ) कोई व्यवसाय करना, या कोई उपजीविका, व्यापार या व्यापार करना।

अनुच्छेद-19(A) | बोलने की आजादी (freedom of speech)

भारत के संविधान मे आर्टिकल 19(A) में भारत के सभी नागरिकों को विचार करने, भाषण देने और अपने व अन्य व्यक्तियों के विचारों के प्रचार की स्वतंत्रता (freedom of speech and expression) प्राप्त है। प्रेस भी अपने विचारों के प्रचार का एक साधन होने के कारण Article-19(A) में प्रेस की स्वतंत्रता भी शामिल है लेकिन नागरिकों को विचार और अभिव्यक्ति की यह स्वतंत्रता असीमित रूप से प्राप्त नहीं है ।

भारत के संविधान मे प्रत्येक व्यक्ति को बोलने का अधिकार जन्मजात दिया गया है यदि प्रत्येक व्यक्ति को बोलना बंद कर दिया गया तो हमारी आवाज़ और हमारे विचार सीमित हो जाएंगे। इसलिए भारतीय संविधान के अनुच्छेद 19(A) के अंदर हमें बोलने की स्वतंत्रता दी गई है और इसे लागू भी किया गया है , यह हमारा मौलिक अधिकार है अतः यदि कोई व्यक्ति किसी के बोलने पर पाबंधी अथवा अपनी बात रखने पर एतराज करता है, तो हम न्यायालय भी जा सकते हैं ।

अनुच्छेद-19(B) | सभा की आजादी (freedom of assembly)

भारत के संविधान मे आर्टिकल 19(B) में व्यक्तियों के द्वारा अपने विचारों के प्रचार के लिए शांतिपूर्वक और बिना किन्हीं शस्त्रों के सभा या सम्मलेन करने का अधिकार प्रदान किया गया है और व्यक्तियों द्वारा जुलूस या प्रदर्शन का आयोजन भी किया जा सकता है। यहाँ भी यह स्वतंत्रता (assemble peacefully and without arms) असीमित नहीं है और राज्य के द्वारा सार्वजनिक सुरक्षा के हित में व्यक्ति की इस स्वतंत्रता को सीमित किया जा सकता है।

भारत के संविधान मे प्रत्येक व्यक्ति को सभा बनाने/सभा मे उपस्थित होने की आजादी है, प्रत्येक व्यक्ति को शांतिपूर्वक और बिना किन्हीं शस्त्रों के सभा या सम्मलेन बनाने या उपस्थित होने की आजादी दिया गया है। इसलिए भारतीय संविधान के अनुच्छेद 19(B) के अंदर सभा बनाने या उपस्थित होने की स्वतंत्रता दी गई है और इसे लागू भी किया गया है , यह हमारा मौलिक अधिकार है अतः यदि कोई व्यक्ति किसी को सभा बनाने या उपस्थित होने पर एतराज करता है, तो हम न्यायालय भी जा सकते हैं ।

अनुच्छेद-19(C) | संघ बनाने की आजादी (freedom of association)

भारत के संविधान मे आर्टिकल 19(C) मे सभी नागरिकों को समुदायों और संघों के निर्माण की स्वतंत्रता प्रदान की गई है परन्तु यह स्वतंत्रता भी उन प्रतिबंधों के अधीन है, जिन्हें राज्य साधारण जनता के हितों को ध्यान में रखते हुए लगाता है। इस स्वतंत्रता की आड़ में व्यक्ति ऐसे समुदायों का निर्माण नहीं कर सकता जो षड्यंत्र करें अथवा सार्वजनिक शान्ति और व्यवस्था को भंग करें।

भारत के संविधान मे प्रत्येक व्यक्ति को संघ बनाने या उपस्थित होने की आजादी है, प्रत्येक व्यक्ति को सार्वजनिक शांति और बिना किसी षणयंत्र के अथवा किसी आम नागरिक को कोई परेशानी को ध्यान मे रखते हुये ऐसे संघ बनाने या उपस्थित होने की आजादी दी गयी है। इसलिए भारतीय संविधान के अनुच्छेद 19(C) के अंदर संघ बनाने या उपस्थित होने की स्वतंत्रता दी गई है और इसे लागू भी किया गया है , यह हमारा मौलिक अधिकार है अतः यदि कोई व्यक्ति किसी को संघ बनाने या उपस्थित होने पर एतराज करता है, तो हम न्यायालय भी जा सकते हैं ।

अनुच्छेद-19(D) | पूरे देश मे आने-जाने की आजादी (freedom of movement throughout the country)

भारत के संविधान मे आर्टिकल 19(D) भारत के सभी नागरिक बिना किसी प्रतिबंध या विशेष अधिकार-पत्र के सम्पूर्ण भारतीय क्षेत्र में कही भी घूम सकते हैं।

भारत के संविधान मे प्रत्येक व्यक्ति को पूरे भारत देश मे आने-जाने की आजादी है, प्रत्येक व्यक्ति को किसी गैर-इरादे (भागने के उद्देश्य निहित न हो) अथवा किसी आम नागरिक को किसी परेशानी को ध्यान मे रखते हुये ऐसे भारत के किसी भी राज्य मे घूमने की आजादी दी गयी है। इसलिए भारतीय संविधान के अनुच्छेद 19(D) के अंदर पूरे भारत देश मे घूमने की आजादी की स्वतंत्रता दी गई है और इसे लागू भी किया गया है , यह हमारा मौलिक अधिकार है अतः यदि कोई व्यक्ति किसी को भारत के किसी राज्य मे आने-जाने पर एतराज करता है, तो हम न्यायालय भी जा सकते हैं ।

अनुच्छेद-19(E) | पूरे देश मेँ बसने की/रहने की आजादी (Freedom to settle/reside throughout the country)

भारत के संविधान मे आर्टिकल 19(E) भारत के प्रत्येक नागरिक को भारत में कहीं भी रहने या बस जाने की स्वतंत्रता प्रदान की गई है। भ्रमण और निवास के सम्बन्ध में यह व्यवस्था संविधान द्वारा अपनाई गई इकहरी नागरिकता के अनुरूप है, भ्रमण और निवास की इस स्वतंत्रता पर भी राज्य सामान्य जनता के हित और अनुसूचित जातियों और जनजातियों के हितों में यक्ति-युक्त प्रतिबंध लगा सकता है।

भारत के संविधान मे प्रत्येक व्यक्ति को पूरे भारत देश मे बसने या रहने की आजादी है, प्रत्येक व्यक्ति को किसी गैर-इरादे (भागने के उद्देश्य निहित न हो) अथवा किसी आम नागरिक को किसी परेशानी को ध्यान मे रखते हुये ऐसे भारत के किसी भी राज्य मे बसने या रहने की आजादी दी गयी है। इसलिए भारतीय संविधान के अनुच्छेद 19(E) के अंदर पूरे भारत देश मे बसने या रहने की आजादी की स्वतंत्रता दी गई है और इसे लागू भी किया गया है , यह हमारा मौलिक अधिकार है अतः यदि कोई व्यक्ति किसी को भारत के किसी राज्य मे बसने या रहने पर एतराज करता है, तो हम न्यायालय भी जा सकते हैं ।

अनुच्छेद-19(G) | कोई भी व्यापार एवं जीविका की आजादी (Freedom of any trade and livelihood)

भारत के संविधान मे आर्टिकल 19(G) भारत में सभी नागरिकों को इस बात की स्वतंत्रता है कि वे अपनी आजीविका के लिए कोई भी पेशा, व्यापार या कारोबार कर सकते हैं | राज्य साधारणतया व्यक्ति को न तो कोई विशेष नौकरी, व्यापार या व्यवसाय करने के लिए बाध्य करेगा और न ही उसके इस प्रकार के कार्य में बाधा डालेगा. किन्तु इस सबंध में भी राज्य को यह अधिकार प्राप्त है कि वह कुछ व्यवसायों के सम्बन्ध में आवश्यक योग्यताएं निर्धारित कर सकता है अथवा किसी कारोबार या उद्योग को पूर्ण अथवा आंशिक रूप से अपने हाथ में ले सकता है।

भारत के संविधान मे प्रत्येक व्यक्ति को पूरे भारत देश मे कोई भी नौकरी, व्यापार करके जीविका चलाने की आजादी है, बशर्ते किसी गैर-कानूनी तरीके व्यापार से नही। प्रत्येक व्यक्ति को नौकरी, व्यापार करके जीविका चलाने की आजादी है। इसलिए भारतीय संविधान के अनुच्छेद 19(G) के अंदर पूरे भारत देश मे कोई भी नौकरी, व्यापार एवं किसी प्रकार से जीविका अर्जित करने की स्वतंत्रता दी गई है और इसे लागू भी किया गया है , यह हमारा मौलिक अधिकार है अतः यदि कोई व्यक्ति किसी को भारत के किसी राज्य मे कोई भी नौकरी, व्यापार एवं अन्य कोई जीविका अर्जित करने पर एतराज करता है, तो हम न्यायालय भी जा सकते हैं ।

नोट- भारत के संविधान के भाग 3 मे मौलिक अधिकारो मे अनुच्छेद-19 भी, प्रत्येक व्यक्ति का एक जन्मसिद्ध अधिकार है, लेकिन जो कोई व्यक्ति इस अधिकार का अनुचित लाभ उठाता है जैसे- भारत की एकता, अखंडता एवं संप्रभुता पर खतरा जैसे स्थिति मे, वैदेशिक संबंधों पर प्रतिकूल प्रभाव की स्थिति में, न्यायालय की अवमानना की स्थिति में उपरोक्त अधिकारों को बाधित करता है अथवा अपने शब्दों से किसी को ठेस पहुचाता है, जो गैर-कानूनी होता है, तो ऐसी दशा मे वह व्यक्ति दोषी माना जायेगा।

इसे भी पढ़े–

अनुच्छेद-21 (Article-21) | निजता का अधिकार | Right to Privacy भारत के संविधान का अनुच्छेद-22 | Article-22 | गिरफ्तारी के खिलाफ संरक्षण | Protection Against Arrest

हमारा प्रयास अनुच्छेद-19 (Article-19) भाषण और अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता (Freedom of Speech and Expression) की पूर्ण जानकारी, आप तक प्रदान करने का है, उम्मीद है कि उपरोक्त लेख से आपको संतुष्ट जानकारी प्राप्त हुई होगी, फिर भी अगर आपके मन में कोई सवाल हो, तो आप कॉमेंट बॉक्स में कॉमेंट करके पूछ सकते है।

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

भारत में भाषण और अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता Freedom of Speech & Expression in India Hindi

आज हम बात करेंगे भारत में भाषण और अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता Freedom of Speech & Expression in India Hindi

हमारा भारत देश विविधताओं का देश है। यहाँ भांति भांति के लोग पाए जाते हैं और उन्हीं के होने में हैं – अलग-अलग प्रकार के चेहरे, बोलियां, संस्कार, संस्कृति , स्वभाव, जीवन शैली, रहन-सहन, खाना-पीना और भी ना जाने बहुत कुछ।

पर हमारे हिंदुस्तान की खूबसूरती इसी बात में है कि इतनी भिन्नता के साथ भी अनेकता में एकता वाली बात है। यही सुंदरता है भारतीय होने की, पर सबसे मजेदार एवं रोचक बात यह है कि इतने अलग अलग प्रकार के लोगों के साथ जो बात सबसे ज्यादा उभर कर आती है, जो बात सबसे अहम है, वह है सब के विचार।

विचार असल में होते क्या है? विचार दरअसल एक व्यक्ति के चरित्र की पहचान होती है, विचार जिंदा है तो मनुष्य जिंदा है। विचारों के कारण ही एक व्यक्ति की शख्सियत बनती है या बिगड़ती है। अगर विचार अच्छे होंगे शुद्ध होंगे निर्मल निश्चल होंगे तो जीवन भी सुखमय होगा।

सभी आसपास के लोग भी आपसे स्नेह एवं प्रेम रखेंगे, दुनिया सलाम करेगी, कठिन से कठिन परिस्थितियों में, मुश्किलों के हालात में भी अगर एक इंसान जिंदा रह पाता है, तो वह अपनी सकारात्मक सोच के कारण ही रह पाता है।

विचार दरअसल सोच है, सोच जो हमारे दिमाग में चलती रहती है, सोच से ही जीवन बिखरता है और बनता ।है अगर वहीं दूसरी ओर आपके विचार खराब होंगे घुटन और नकारात्मकता से भरे होंगे, तो कितना ही कुछ कर ले फिर भी जीवन में आप का कभी भला नहीं हो पाएगा, आप बस दुखों में ही डूबे रहेंगे।

फिर विचारों से भी ऊपर बात आती है विचारों की अभिव्यक्ति की!! बिल्कुल, जो भी आपके विचार हैं आपको उनकी अभिव्यक्ति करनी आनी चाहिए, मतलब अगर आपके पास अच्छे से अच्छे विचार हैं आपकी सोच अच्छी है पर आप उन शब्दों को बोल नहीं पा रहे हैं तो सब बेकार है। अर्थात आपको आपके विचारों को अभिव्यक्त करना आना चाहिए।

आपको अपनी सोच के बारे में बताना आना चाहिए, आप क्या सोचते हैं आपकी ज़ुबान पर आना चाहिए, तभी बात बनेगी। मतलब सीधे शब्दों में कहें तो दिल की बात जुबान पर आनी चाहिए।

फिर हम आए इस बात पर कि भारत में विचारों की अभिव्यक्ति पर कितनी स्वतंत्रता है, तो जवाब मिला जुला होगा। थोड़ा खट्टा थोड़ा मीठा होगा!! दरअसल सच्ची बात कहें तो हमारे देश में विचारों की अभिव्यक्ति पर कोई जबरन रोक-टोक नहीं है, आपके जो मन की बात है वह आप कह सकते हैं जिससे चाहे उससे कह सकते हैं, किसी पर भी कोई प्रकार की जबरदस्ती नहीं है, पूरा खुलापन है विचारों का।

आप अपने मन की बात बिना रोक-टोक अभिव्यक्त कर सकते हैं पूरी स्वतंत्रता है इस बात की!! परंतु कभी-कभी कुछ लोग इस स्वतंत्रता का गलत फायदा उठाने की कोशिश करते हैं और देश में अशांति फैलाने में जुटे रहते हैं। दरअसल होता क्या है कि विचारों की अभिव्यक्ति करने का भी एक अंदाज होता है एक तरीका होता है, विचारों को सही प्रकार सही ढंग से व्यक्त करना भी एक कला है।

कभी-कभी लोग अच्छी सोच को भी गलत शब्दों में डालकर बोल देते हैं, उनकी सोच या उनकी मंशा गलत नहीं होती है बस उनका अंदाज उनका तरीका और कभी-कभी बस वक्त भी गलत हो जाता है। ऐसे में होता क्या है कि बेचारा व्यक्ति बुरी परिस्थितियों में फंस जाता है और कटाक्ष एवं मजाक का पात्र बन जाता है।

फिर आते हैं वह लोग जो जानबूझकर कड़वी बात करते हैं, जानते हुए भी घटिया हरकतें करते हैं। ऐसे लोग भड़काऊ उत्तेजक बयान बाजी करके नकारात्मकता फैलाने की कोशिश करते हैं, ऐसे में होता यह है कि जो लोग इन सब चीजों से अनजान है मासूम है वह इन सब का आकस्मिक शिकार बन जाते हैं और कभी-कभी अपने आसपास के लोगों से झगड़ा कर बैठते हैं।

कुछ लोगों का तो मकसद ही होता है नकारात्मकता का माहौल पैदा करना और इन मंसूबों में वह कामयाब हो जाते हैं क्योंकि काफी लोग इन खराब लोगों की घटिया दर्जे की राजनीति से अनजान रहते हैं। देश में, मुल्क में तो हमेशा ही मुहब्बत, प्रेम की लहर होनी चाहिए और सकारात्मकता फैलाने के लिए हमारे विचार सबसे बड़ा जरिया होते हैं, तो बस इन्हीं विचारों को ढंग से नाप तोल कर व्यक्त करें तो ही बेहतर होगा।

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

HiHindi.Com

HiHindi Evolution of media

अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता पर निबंध | Essay On Freedom Of Speech In Hindi

Essay On Freedom Of Speech In Hindi अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता पर निबंध : हमारा भारत एक लोकतांत्रिक देश हैं, हमारा संविधान नागरिकों को कई प्रकार के मौलिक अधिकार देता है जिनमें समानता, स्वतंत्रता, धार्मिक आजादी और अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी मुख्य हैं.

आज के निबंध में हम फ्रीडम ऑफ़ स्पीच क्या है इसके पक्ष विपक्ष में तर्क वितर्क आलोचना आदि बिन्दुओं को जानेगे.

अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता पर निबंध Essay On Freedom Of Speech In Hindi

नवजात शिशु का क्रन्दन बाहरी दुनियां के प्रति उसकी प्रतिक्रिया की अभिव्यक्ति हैं. अभिव्यक्ति की इच्छा किसी व्यक्ति की भावनाओं, कल्पनाओं एवं चिन्तन से प्रेरित हैं और अपनी अपनी क्षमता के अनुरूप होती हैं.

अपनी भावना या मत को अभिव्यक्त करने की आकांक्षा कभी कभी इतनी मजबूत बन जाती हैं कि व्यक्ति अकेला होने पर भी खुद से बात करने लगता हैं, मगर अभिव्यक्ति की निर्दोषता और सदोषता का प्रश्न तभी उठता हैं, जब अभिव्यक्ति बातचीत का रूप लेती हैं व्यक्तियों के बीच या समूहों के बीच.

हमारे मौलिक अधिकारों में अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी का मौलिक अधिकार शामिल किया गया हैं. इसका सरल सा अर्थ यह है कि हम अपने हक हकूक के लिए आवाज उठा सकते हैं.

अपने खिलाफ हो रहे अन्याय का खुलकर प्रतिरोध कर सकते हैं. बोलने की आजादी का दायरा भी सिमित रखा गया हैं, हम केवल मर्यादा में बने रहकर ही आवाज उठा सकते हैं.

अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी की उत्पत्ति

अगर थोड़ा अतीत में झांके तो बोलने की आजादी की सबसे पहले मांग इंग्लैंड में की गई थी, तदोपरांत वहां वर्ष 1689 में मौलिक अधिकार के रूप में अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी को मान्यता मिली.

इस स्वतंत्रता के तहत सभी नागरिकों को अपने विचारों और भावनाओं को बिना शासकीय बंदिश के अभिव्यक्त करने की पूर्णरूपेण आजादी प्रदान की गई हैं.

यह अधिकार उसे लिखित मुद्रित रूप में अपने विचारों को अभिव्यक्त करने की आजादी देता हैं. अन्य मौलिक अधिकारों की भांति इसके उल्लंघन की स्थिति में व्यक्ति कोर्ट जा सकता हैं.

भारतीय संविधान के मूल अधिकारों में अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी के अधिकार को सार्वभौमिक रूप से सर्वसहमति से स्वीकार किया गया था.

बोलने की आजादी की सीमाएं

वैसे तो प्रत्येक संवैधानिक अधिकार के साथ कुछ उपबन्ध बनाए गये हैं जो ये सीमा निर्धारित करते है कि किस हद तक उस अधिकार का उपयोग मर्यादापूर्ण हैं. देश के संविधान का अनुच्छेद 21 अपने नागरिकों को अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी देता हैं मगर कुछ युक्तियुक्त निर्बंधनों के साथ.

वो इस तरह की अगर एक इंसान की अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी का प्रभाव देश की एकता अखंडता और सम्प्रभुता को प्रभावित करने वाला हो तो अथवा सामाजिक सौहार्द, न्यायालय की अवमानना से जुड़ा हो तो उसे प्रतिबंधित किया गया हैं.

बोलने की आजादी के नाम पर किसी को गाली देने अथवा अपमानित करने की वकालत भारतीय संविधान नहीं करता हैं.

अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी जरूरत क्यों है?

मनुष्य अन्य सभी जीवों की तुलना में इसलिए श्रेष्ठ हैं क्योंकि उनके पास विचार करने की शक्ति हैं तथा वह अपने भावों को किसी भाषा के माध्यम से अभिव्यक्त करने में समक्ष हैं. समतामूलक समाज में यह आवश्यक हो जाता हैं कि प्रत्येक नागरिक को अपनी बात कहने का अधिकार हो.

राजशाही में इनकी अवहेलना की जाती थी, अत्याचार के खिलाफ बोलने वालों को डरा धमका कर चुप करा दिया जाता था. मगर आधुनिक लोकतांत्रिक समाज के समुचित विकास के लिए नागरिकों को सर्वांगीण विकास के मौके उपलब्ध कराने में अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी एक बड़ा पहलू हैं जो हर हालत में उपलब्ध होना ही चाहिए.

अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता की बदौलत ही दूसरों के विचारों को समझने उन पर चर्चा और आम सहमति बन सकती हैं, यही लोकतंत्र का बुनियादी आधार हैं.

राजनैतिक पार्टी हो या समाज जहाँ विभिन्नताएं है स्वभाविक हैं विचारों में भी अलग अलग राय हो सकती हैं अतः सभी को अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी के अधिकार दिए बिना समाज व देश की तरक्की नहीं की जा सकती.

अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता के दुरुपयोग

अन्य संवैधानिक अधिकारों की तरह अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता के अधिकार के भी दुरूपयोग की पर्याप्त सम्भावनाएं रहती हैं. इसकी बड़ी वजह यह हैं कि बोलने की आजादी की सीमाएं न तो स्पष्ट परिभाषित है न इनके दुरूपयोग को रोकने के न कोई विशिष्ट प्रबंध हैं.

भारत में फ्रीडम ऑफ़ स्पीच और एक्सप्रेशन के नाम पर आए दिन देश द्रोही बाते आम हैं. हर दिन देश को तोड़ने वाली वाली बाते बड़े बड़े मंचों से केवल फ्रीडम के नाम से कही जाती हैं.

देश की सेना, प्रधानमंत्री, हिन्दू धर्म के बारे में आए दिन वैसे विवादित ब्यान दिए जाते हैं जिन्हें अधिकारों की चादर ओढकर छिपाने का छद्म व्यापार सभी के सामने हैं.

किसी भी समाज में नागरिकों के विचारों का दमन करना ठीक नहीं हैं. विचारों का खुला प्रवाह विकास की राह खोलता हैं. साथ ही किसी नागरिक को किस हद तक जाकर बोलने की आजादी होनी चाहिए, इन पर कठोर कानून बनाकर समुचित व्यवस्था बनाएं जाने की जरूरत हैं.

आज सोशल मिडिया अभिव्यक्ति का एक बड़ा माध्यम हैं. जहाँ पर अच्छे विचारों के साथ ही देश की एकता और सौहार्द को बिगाड़ने वाले भड़कीले भाषण भी देखने मिलते हैं.

समय आ गया हैं राष्ट्र को तोड़ने की नियत से कहे जाने वाले विचारों का दमन आवश्यक हैं साथ ही आम आदमी को राष्ट्रीय एकता, सुरक्षा, सम्प्रभुता के विषयों को छोडकर अन्य पर बोलने अपने विचार रखने की स्वतंत्रता की रक्षा की जानी चाहिए.

- समानता का अधिकार पर निबंध

- सूचना का अधिकार अधिनियम 2005 निबंध

- शिक्षा का अधिकार अधिनियम पर निबंध

- स्वतंत्रता का अधिकार

- धार्मिक स्वतंत्रता का अधिकार क्या है

- मौलिक अधिकार का महत्व पर निबंध

हम उम्मीद करते है “ अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता पर निबंध Essay On Freedom Of Speech In Hindi ” में दी गई जानकारी आपको उपयोगी लगी होगी, फ्रीडम ऑफ़ स्पीच के बारे में आपके विचार हमारे साथ अवश्य शेयर करें.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

हिन्दीकुंज,Hindi Website/Literary Web Patrika

- मुख्यपृष्ठ

- हिन्दी व्याकरण

- रचनाकारों की सूची

- साहित्यिक लेख

- अपनी रचना प्रकाशित करें

- संपर्क करें

Header$type=social_icons

अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता पर निबंध

अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता पर निबंध अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता पर निबंध भारत में अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी अभिव्यक्ति की स्वतंत्रता Freedom Of Expression अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी पर बड़े निबंध Essay on Freedom of Speech in Hindi essay on freedom of speech in hindi देखा जाए तो अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी एक मूल मानव अधिकार है|

भारत में अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी

अभिव्यक्ति की ज़रुरत क्यों है , अभिव्यक्ति की आजादी का कमजोर कमजोर पक्ष , अन्याय के खिलाफ़ आवाज.

Please subscribe our Youtube Hindikunj Channel and press the notification icon !

Guest Post & Advertisement With Us

हिंदीकुंज में अपनी रचना प्रकाशित करें

कॉपीराइट copyright, हिंदी निबंध_$type=list-tab$c=5$meta=0$source=random$author=hide$comment=hide$rm=hide$va=0$meta=0.

- hindi essay

उपयोगी लेख_$type=list-tab$meta=0$source=random$c=5$author=hide$comment=hide$rm=hide$va=0

- शैक्षणिक लेख

उर्दू साहित्य_$type=list-tab$c=5$meta=0$author=hide$comment=hide$rm=hide$va=0

- उर्दू साहित्य

Advertisement

Most Helpful for Students

- हिंदी व्याकरण Hindi Grammer

- हिंदी पत्र लेखन

- हिंदी निबंध Hindi Essay

- ICSE Class 10 साहित्य सागर

- ICSE Class 10 एकांकी संचय Ekanki Sanchay

- नया रास्ता उपन्यास ICSE Naya Raasta

- गद्य संकलन ISC Hindi Gadya Sankalan

- काव्य मंजरी ISC Kavya Manjari

- सारा आकाश उपन्यास Sara Akash

- आषाढ़ का एक दिन नाटक Ashadh ka ek din

- CBSE Vitan Bhag 2

- बच्चों के लिए उपयोगी कविता

Subscribe to Hindikunj

Footer Social$type=social_icons

- नई कहानियां

- अनमोल इंडियंस

- घर हो तो ऐसा

- प्रेरक किसान

- प्रेरक बिज़नेस

- कहानी का असर

- हमारे बारे में

- Follow Us On

देश की आज़ादी के लिए कुर्बान वे नायक, जिनके बारे में शायद ही सुना हो आपने

देश 75वां स्वतंत्रता दिवस मना रहा है। देश की आज़ादी हमें कई लोगों के बलिदान, साहस और त्याग से मिली है। लेकिन ऐसे कई हीरोज़ हैं, जिनके साहस की कहानियां इतिहास के पन्नों पर धुमिल हो गई हैं।

1. एस आर शर्मा

2. गुमनाम फ्रीडम फाइटर्स में एक नाम निकुंजा सेन

3. उदय प्रसाद ‘उदय’

4. मींधू कुम्हार , गुमनाम फ्रीडम फाइटर्स में से एक

5. कैप्टन राम सिंह ठाकुर

We at The Better India want to showcase everything that is working in this country. By using the power of constructive journalism, we want to change India – one story at a time. If you read us, like us and want this positive movement to grow, then do consider supporting us via the following buttons:

Let us know how you felt

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Get your daily dose of uplifting stories, positive impact, and updates delivered straight into your inbox.

भारत के इन चटक अचारों का स्वाद , एक बार चखा तो हमेशा रहेगा याद

गर्मियों में इस तरह करें अपने तुलसी के पौधे की देखभाल

सौंधी सुगंध शाही Taste भारत की ये बिरयानी हैं सबसे Best

गर्मियां जाएंगे भूल, ये देसी समर ड्रिंक्स रखेंगे आपको कूल

राजस्थान की भीषण गर्मी में भी इनके घर में रहती है ठंडक

इन जगहों पर जाएं और खो जाएं सितारों की दुनिया में

रंगीले भारत के रंगीन शहर

भारत का गौरव बढ़ाने वाली वो कलाएं जिन्हें मिला है GI टैग

गर्मियां शुरू होने से पहले ही उगा ले ये सब्जियां

भारत को ऑस्कर दिलाने वाले अनमोल भारतीय

समाज की बेड़ियां तोड़ने वाली शक्तिशाली महिलाओं के विचार

Constitution of India

Home / constitution of india, constitutional law, freedom of speech & expression, 20-nov-2023.

- Constitution of India, 1950 (COI)

Introduction

- Freedom of speech and expression is contained in Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution of India, 1950 (COI).

- The essence of free speech is the ability to think and speak freely and to obtain information from others through publications and public discourse without fear of retribution, restrictions or repression by the Government.

Article 19(1)(a), COI

- The philosophy behind this Article lies in the Preamble of the Constitution, where a solemn resolve is made to secure to all its citizen, liberty of thought and expression.

- Freedom of Press

- Freedom of Commercial Speech

- Right to Broadcast

- Right to Information

- Right to Criticize

- Right to expression beyond national boundaries

- Right not to speak or right to silence

Essential Elements of Article 19(1)(a), COI

- This right is available only to a citizen of India and not to foreign nationals.

- It includes the right to express one’s views and opinions at any issue through any medium, e.g. by words of mouth, writing, printing, picture, film, movie etc.

- This right is, however, not absolute and it allows Government to frame laws to impose reasonable restrictions.

Article 19(2), COI

- The exercise of this right is, however, subject to reasonable restrictions for certain purposes imposed under Article 19(2) .

- The Article 19 (2) states that nothing in sub clause (a) of clause (1) shall affect the operation of any existing law, or prevent the State from making any law, in so far as such law imposes reasonable restrictions on the exercise of the right conferred by the said sub clause in the interests of the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, public order, decency or morality or in relation to contempt of court, defamation or incitement to an offence.

Significance of Article 19 (1)(a), COI

- Societal good : Liberty to express opinions and ideas without hindrance, and especially without fear of punishment plays a significant role in the development of a particular society.

- Self-development : Free speech is an integral aspect of each individual’s right to self-development and fulfilment. Restrictions inhibit our personality and its growth.

- Democratic value : Freedom of speech is the bulwark of democratic Government. This freedom is essential for the proper functioning of the democratic process as it allows people to criticize the government in a democracy, freedom of speech and expression open up channels of free discussion of issues.

- Ensure pluralism : Freedom of Speech reflects and reinforces pluralism, ensuring that diversity is validated and promotes the self-esteem of those who follow a particular lifestyle.

- In Romesh Thappar v. State of Madras (1950) : The Supreme Court (SC) observed that freedom of the press lays at the foundation of all democratic organizations.

- In Abbas v. Union of India (1970) : The SC made it clear that censorship of films including pre-censorship was constitutionally valid in India as it was a reasonable restriction imposed on Article 19(1)(a) of the COI.

- In Bennett Coleman and Co. v. Union of India (1972): The SC struck down the validity of the Newsprint Control Order, which fixed the maximum number of pages, holding it to be violative of provision of Article 19(1)(a) and not to be reasonable restriction under Article 19(2) of the COI.

- In Maneka Gandhi vs Union of India (1978) : The SC held that the freedom of speech and expression is not confined to National boundarie s.

- In Indian Express v. Union of India (1985) : The SC held that the Press plays a very significant role in the democratic machinery. The courts have a duty to uphold the freedom of press and invalidate all laws and administrative actions that abridge that freedom .

- In Bijoe Emmanuel v. State of Kerala (1986) : The SC held that the right to speak includes the right to be silent or to utter no words .

- In Union of India v. Assn. for Democratic Reforms (2002) : The SC held that one-sided information, disinformation, misinformation and noninformation, all equally create an uninformed citizenry which makes democracy a farce. Freedom of speech and expression includes the right to impart and receive information which includes freedom to hold opinions.

- Create new account

- Reset your password

Article 19: Mapping the Free Speech Debate in India

The Freedom of Speech and Expression is a fundamental right guaranteed to all citizens under the Constitution of India. However, the Constitution does not guarantee an absolute individual right to freedom of expression. Instead, it envisages reasonable restrictions that may be placed on this right by law.

Many laws that restrict free speech such as the laws punishing sedition, hate speech or defamation, derive their legitimacy from Article 19(2). Inspection of movies, books, paintings, etc, is also possible by way of this clause. Scholars note that censorship in India was, and still is, historically rooted in the discourse of protecting Indian values from outside forces and building and maintaining strong national unity post independence. Scholars conclude that any misuse of the law could be detrimental to arts and ideas.

The freedom to criticise and dissent are part of one’s broader freedom of speech, which is seen as fundamental to the functioning of a democracy. If a state’s citizenry is not free to express themselves, then their other civil and political rights are also under threat.

The freedom of expression, however, is paramount to the working of a democracy and it includes the right to offend. For a little over half a decade, questions of whether “hate speech” can be excused under the right to freedom of speech, have been raised by various quarters of society—their stance often varying from one case to the other.

The freedom of press is also crucial to the functioning of participative democracy. In the absence of a free press, citizens lose their ability to make informed decisions in a free and fair electoral process. In conclusion,

“Intolerance of dissent from the orthodoxy of the day has been the bane of Indian society for centuries. But it is precisely in the ready acceptance of the right to dissent, as distinct from its mere tolerance, that a free society distinguishes itself.” —A G Noorani, 1999

In this resource kit, we have collated over 200 articles from the EPW archive and built a repository of articles that cover these debates.

Scroll over the redacted text of Article 19 (1) (a) and Article (19) (2) below to explore more.

All citizens shall have the right to freedom of speech and expression …

Nothing in sub clause (a) of clause (1) shall affect the operation of any existing law, or prevent the State from making any law, in so far as such law imposes reasonable restrictions on the exercise of the right conferred by the said sub clause in the interests of the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State , friendly relations with foreign States, public order , decency or morality or in relation to contempt of court , defamation or incitement to an offence.

Freedom of Speech and Public Order

Laws maintaining public order seek to restrict and punish the harassment of individuals, hate speech and public nuisance. Any speech or publication considered prejudicial to these interests is subject to censorship. Restrictions on freedom of speech can also be invoked to curb the spread of misinformation and disinformation since these are likely to be inimical to public order.

While there are laws that punish offensive speech that may hurt the religious or cultural sentiments of sections of society, conservative groups have, on occasion, themselves posed a threat to public order in order to create a justification for restricting speech that may be critical of specific cultural or religious norms.

Articles in this section outline several such cases—the 1989 Supreme Court ruling to insert a disclaimer before a television serial on Tipu Sultan’s life claiming it depicts his life truly; the assassination of rationalist Narendra Dabholkar in 2013; the 2014 speech by Hindu Rashtra Sena leaders in Pune, that lead to communal violence and the death of Mohsin Sheikh; and the 2014 uproar against Perumal Murugan’s book, Madhorubhagan. Some articles also describe how right-wing groups across the country feel empowered to dictate what the people should read and watch.

It must be noted that while the intent of the speeches that have led to communal disharmony and violence can and must be questioned, at the same time, the use of the politics of “hurt religious sentiments” to organise violence must also be questioned. This leads to legal ambiguity. How can a distinction be drawn between individuals giving deliberate malicious speeches aimed at outraging religious sentiments and spreading enmity on the one hand and exercising their freedom of speech on the other?

- Freedom of Speech in Universities | A G Noorani, 1991

- Blasphemy and Religious Criticism | Nasim Ansari, 1992

- Hate Speech and Free Speech | A G Noorani, 1992

- Politics of Religious Hate-Beyond the Bills | Anil Nauriya, 1993

- Police as Film Censors | A G Noorani, 1995

- Hate Propaganda in Gujarat Press and Bardoli Riots | Ghanshyam Shah, 1998

- Art in the Time of Cholera | Sumanta Banerjee, 2000

- From Coercion to Power Relations | Someswar Bhowmik, 2003

- Habib Tanvir under Attack | Sudhanva Deshpande, 2003

- Cartoon Protests: Religion and Freedom | EPW Editorial, 2006

- Ban on Films: Break the Silence | EPW Editorial, 2007

- Taslima Case: Accountability of Elected Representatives | K G Kannabiran and Kalpana Kannabiran, 2007

- Free Speech - Hate Speech: The Taslima Nasreen Case | Iqbal A Ansari, 2008

- Films and Free Speech | A G Noorani, 2008

- Free Speech and Religion | A G Noorani, 2009

- Religion, Freedom of Speech and Imaging the Prophet | Sudha Sitharaman, 2010

- Cartoons, Caste and Politics | Manjit Singh, 2012

- Ambedkar Cartoon Controversy | EPW Editorial, 2012

- Cartoons, Textbooks and Politics of Pedagogy | G Arunima, 2012

- The Constitution, Cartoons and Controversies | Kumkum Roy, 2012

- Through the Lens of a Constitutional Republic | Peter Ronald deSouza, 2012

- Symbolic Injury as a Site of Protest | Sheba Tejani, 2012

- Ashis Nandy's Critics and India's Thriving Democracy | Indrajit Roy, 2013

- The Dilemmas and Challenges faced by the Rationalist Indian | T V Venkateswaran, 2013

- The Age of Hurt Sentiments | Kannan Sundaram, 2015

- Intolerance of Dissent | Megha Bahl and Sharmila Purkayastha, 2015

- The Tyranny of 'Hurt' Feelings | Ambrose Pinto, 2015

- Unofficial Censors | EPW Editorial, 2015

- 'Hurt': Old Sentiment, New Claims | Manash Bhattacharjee, 2015

- Instigators of Murderous Mobs | Prashant Singh, 2016

- The Republic of Reasons | Alok Rai, 2016

- Hate Speech, Hurt Sentiment, and the (Im)Possibility of Free Speech | Siddharth Narrain, 2016

- Harmful Speech and the Politics of Hurt Sentiments | Philipp Sperner, 2016

- Republic of Hurt Sentiments | Vikram Raghavan and Iqra Zainul Abedin, 2017

- The Game of Hurt Sentiments | EPW Editorial, 2017

- Sexual Harassment and the Limits of Speech | Rukmini Sen, 2017

- Dangerous Speech in Real Time: Social Media, Policing, and Communal Violence | Siddharth Narrain, 2017

- Social Media Accountability | Alok Prasanna Kumar, 2018

- A Blasphemy Law is Antithetical to India's Secular Ethos | Surbhi Karwa and Shubham Kumar, 2019

- India Needs a Fresh Strategy to Tackle Online Extreme Speech | Sahana Udupa, 2019

- Muzzling Artistic Liberty and Protesting Anti-conversion Bill in Jharkhand | Sujit Kumar, 2019

- Speech as Action | Richa Shukla and Dalorina Nath, 2020

- Do Indian Courts Face A Dilemma in Interpreting Hate Speech? | Neha Gupta and Kavya Gupta, 2020

Freedom of Speech and Reasonable Restrictions

“Freedom of expression is a privilege for some and denied to others while those strangling free expression continue to unabashedly sing the mantra of freedom and democracy’’ (EPW editorial, 16 September 2017). This quote captures the manner in which this freedom can be manipulated. For the functioning of any democracy, it is of importance that its citizens are guaranteed the freedom of speech with reasonable restrictions. The state has to ensure that its citizens can exercise this fundamental right without any threat to their personal liberty.

The implementation of this right in the context of book bans, censoring films and plays has often been contested in courts and judgments have taken a progressive stance. This freedom of expression applies not only to easily agreeable ideas but also to “ideas that offend, shock or disturb” the audience. The censor board has often overstepped its role as a certification body and outrageously demanded cuts in films and sometimes even a change in the narrative. The courts have rescued many films such as the Hindi film Udta Punjab, the Tamil film Ore Oru Gramathile and many others, from the subjective ruling of the censor board. In recent times, content put out on social media and the role of fake news in spreading disruptive misinformation has also become a subject of discussion in light of the manner in which restrictions can be placed. Scholars have discussed whether social media users or the platforms themselves should be held responsible for communications that promote hateful speech and intolerance. Discussions are geared towards the likely consequences of online censorship.

Articles in this section discuss the basis of “reasonable restrictions” to the freedom of speech in India on the grounds of “public interest.” The debates regarding what constitutes a “reasonable” restriction are also covered here.

- Censorship: Scope and Limitations | EPW Legal Correspondent, 1976

- Film Censorship | A G Noorani, 1983

- TV Films and Censorship | A G Noorani, 1990

- Film Censorship and Freedom | A G Noorani, 1994

- Who Draws the Line-Feminist Reflections on Speech and Censorship | Ratna Kapur, 1996

- Politics of Film Censorship | Someswar Bhowmik, 2002

- Mutilated Liberty and the Constitution | Nirmalendu Bikash Rakshit, 2003

- Book Banning | A G Noorani, 2007

- The Constitution and Censorship of Plays | A G Noorani, 2008

- Turning the Spotlight on the Media | EPW Editorial, 2011

- Censoring the Internet: The New Intermediary Guidelines | Rishab Bailey, 2012

- Does Censorship Ever Work? | Geeta Seshu, 2012

- We Do Not 'Like' | EPW Editorial, 2012

- Two Films, Two Opinions | EPW Editorial, 2015

- Certify, Not Censor | EPW Editorial, 2016

- The Persuasions of Intolerance | Janaki Srinivasan, 2016

- First Amendment to Constitution of India | C K Mathew, 2016

- Flight of Common Sense | EPW Editorial, 2016

- Taking Free Speech Seriously | Vikram Raghavan, 2016

- A Twisted Freedom | EPW Editorial, 2017

- Censorship through the Ages | Suhrith Parthasarathy, 2018

- The Real and the Fake in Democracy | Gopal Guru, 2019

- Proscribing the ‘Inconvenient’ | Dhaval Kulkarni, 2020

- Safeguarding Fundamental Rights | Madan Bhimrao Lokur, 2020

- Predicament of the Social Media Ordinance | EPW Editorial, 2020

Freedom of Speech and Morality

When it comes to maintaining decency and morality, the fundamental right to free speech can be restricted. This controversial ground of restriction has been the subject of much discussion and debate, especially in the context of censorship of art and literature, with most of the censoring having been sought to protect the public from depictions of obscenity. However, as was the case with maintaining public order, courts have not always applied the law consistently and are rooted in what has been referred to as a “colonial hangover of the moral police.”

The arts are particularly susceptible to judgments on morality and decency—cinema even more so. Several articles in this section deal with India’s film censor board, questioning its lack of clarity, purpose, people and qualifications. The censor board has been criticised for adhering to a “Victorian legacy” and clinging to India’s colonial past. Censorship legislation was introduced in 1918 when cinema needed to serve colonial interests. Films back then were politically manipulated, withdrawn or promoted depending on their material, something that seems to have been followed to varying degrees even post-independence. In 1998, the screening of Deepa Mehta’s film, Fire, was stopped by Shiv Sainiks and referred back to the censor board. Since then, there have been several instances of the Hindu right attempting to capture India’s cultural spaces and redefine “mainstream morality” in line with its idea of Indian society. Their actions, legal and otherwise, have been a major point of debate and discussion in the papers included in this section. The articles in this section cover issues from banning plays, revising books, controlling the media, in addition to censoring films.

Courts have sought to remove the arbitrariness in the characterisation of what constitutes public morality by devising various tests of acceptable standards of public speech. But these tests have changed and evolved over time. In this context, several articles raise the pertinent question of how morality should be defined and who has the authority to do so.

- From Obscenity to Gherao | Nireekshak, 1967

- Policemen and Obscenity | A G Noorani, 1981

- Women Films and Censorship | S Sujatha, 1982

- Bogey of the Bawdy-Changing Concept of Obscenity in 19th Century Bengali Culture | Sumanta Banerjee, 1987

- Police and Porn | A G Noorani, 1995

- Set This House on Fire | Carol Upadhya, 1998

- Mirror Politics: ‘Fire’, Hindutva and Indian Culture | Mary E John and Tejaswini Niranjana, 1999

- Cultural Politics of Fire | Ratna Kapur, 1999

- Conferring 'Moral Rights' on Actors | Vinay Ganesh Sitapati, 2003

- Entangled Histories | Anjali Arondekar, 2006

- Dance Bar Girls and the Feminist's Dilemma | Nalini Rajan, 2007

- The Item Number: Cinesexuality in Bollywood and Social Life | Rita Brara, 2010

- Cheerleaders in the Indian Premier League | Ashwini Tambe and Shruti Tambe, 2010

- 'Gaylords' of Bollywood: Politics of Desire in Hindi Cinema | Rama Srinivasan, 2011

- Yours Censoriously | Ashish Rajadhyaksha, 2014

- No Offence Taken | Avishek Parui, 2014

- Banning Child Pornography | Anant Kumar, 2016

- Colonial Hangover of the Moral Police | EPW Editorial, 2016

Freedom of Speech and Contempt of Court

Codified under the Contempt of Courts Act, 1971, the judiciary has the power to punish both civil and criminal contempt—civil contempt is the willful disobedience to a judgment and criminal contempt is when an act lowers the authority of the court, interferes with or obstructs the administration of justice. However, contempt of court sometimes conflicts with the fundamental right to freedom of speech. And while fair criticism of judicial pronouncements is not within the definition of contempt, the interpretation of contempt is in the hands of the courts themselves and can lead to arbitrary legal action against dissenters.

Articles in this section have discussed widening the ambit of contempt of court over the years and its failure to strike a balance between freedom of speech and the administration of justice.

The 1967 E M S Namboodiripad v T N Nambiar case, where Namboodiripad was convicted for contempt of court by the Kerala High Court; the 1999 Narmada Bachao Andolan v Union of India case where the Supreme Court contemplated contempt proceedings against Arundhati Roy; the 2001 proceedings against Delhi-based Wah India Magazine for “rating” judges; the 2016 Govindaswamy v State of Kerala case, where the Supreme Court issued a contempt notice to Justice Markandey Katju for criticising its judgment; the 2017 contempt proceedings against Justice C S Karnan, a sitting judge of the Calcutta High Court for levelling allegations of corruption against several judges without evidence, the 2020 contempt proceedings against advocate, Prashant Bhushan for two tweets about the conduct of the Chief Justice of India; against stand-up comedian Kunal Kamra and cartoonist Rachita Taneja for tweeting about the Supreme Court granting journalist Arnab Goswami interim bail—the articles in this section cover several such cases and highlight the underlying systemic issues and general institutional decline of the judiciary.

While some proceedings are perhaps warranted, scholars argue that the contempt jurisdiction was not meant to be used in this spirit. As India’s laws are based on English laws, it has also been pointed out that the contempt law is obsolete in England. Articles in this section suggest that a solution needs to be found, such that the implementation of this law protects the freedom of speech as well as permits the administration of justice in a fair manner.

- Freedom of Speech and Contempt of Court | S P Sathe, 1970

- Public Discussion and Contempt of Court | A G Noorani, 1984

- On Contempt, Contemners and Courts | Vinod Vyasulu, 1995

- NBA Contempt of Court Case | S P Sathe, 2001

- Contempt of Court and Free Speech | A G Noorani, 2001

- Judging the Judges | Sumanta Banerjee, 2002

- Accountability of the Supreme Court | S P Sathe, 2002

- Accountability of Supreme Court | P Chandrasekhar, 2002

- Ayodhya Issue and Freedom of Expression | P Radhakrishnan, 2002

- Truth on Its Way to Half a Victory | Sukumar Mukhopadhyay, 2006

- Judicial Accountability or Illusion? | Prashant Bhushan, 2006

- Judicial Pronouncements and Caste | Rakesh Shukla, 2006

- Uses and Abuses of the Potent Power of Contempt | Rahul Donde, 2007

- The Contempt of Evidence | Madhu Bhaduri, 2007

- Lawless Lawyers | A G Noorani, 2008

- Judicial Accountability: Asset Disclosures and Beyond | Prashant Bhushan, 2009

- The Insulation of India's Constitutional Judiciary | Abhinav Chandrachud, 2010

- Media Follies and Supreme Infallibility | Sukumar Muralidharan, 2012

- A Judicial Doctrine of Postponement and the Demands of Open Justice | Sukumar Muralidharan, 2012

- Supreme Court's Decision on Reporting of Proceedings | Raghav Shankar, 2012

- Defend Freedom of Expression | Kumari Jayawardena et al, 2014

- Debating Contempt of Court | Alok Prasanna Kumar, 2016

- The Curious Case of Justice Karnan | Smita Chakraburtty, 2017

- The Crisis in the Judiciary | Alok Prasanna Kumar, 2017

- Supreme No More | EPW Editorial, 2017

- A Decade of Decay | Alok Prasanna Kumar, 2020

- The Supreme Court: Then and Now | Justice A P Shah, 2020

- Contempt of Court: Does Criticism Lower the Authority of the Judiciary? | EPW Engage, 2021

Freedom of Speech and Defamation

Restrictions concerning defamation seek to protect an individual’s right to reputation and dignity against another’s right to free speech and information. Similar to other reasonable restrictions to free speech, the defamation law cuts both ways. As the individual’s right to reputation and dignity stems from the right to privacy and the right to life and liberty, it seeks to protect individuals from false and frivolous claims about their private lives that can harm their public image. On the other hand, defamation laws have been misused to harass the media and deter it from accurate reporting, and in more malicious cases such as those of sexual assault, they have been deployed against survivors forcing them to defend themselves. Articles in this section highlight the fact that defamation laws have been used to pursue SLAPPs (Strategic Litigation Against Public Participation) which accentuate pre-existing gendered power imbalances.

The 2021 criminal defamation case against Priya Ramani by M J Akbar is a classic example of a powerful man with greater resources, using the high cost of litigation to intimidate a sexual harassment survivor. A few other cases that have been featured are related to the press. Typically, the press is free to comment on any public figure and is not guilty of defamation unless the defendant proves otherwise. The 2008 defamation case by Justice P B Sawant against the television news channel Times Now; the 2005 defamation case against Mediaah and the 2011 case against The Hoot by the Times group itself, are a few of the cases that articles in this section comment on. While criminal defamation laws have been challenged in court, they have also been upheld as being constitutionally valid. Articles in this section have called for a debate on the defamation law, and an interrogation into the interests of “big business and big media and the state.”

- Defamation Bill: High Political Status | A Correspondent, 1988

- Retrogression and Defamation-The Cost of the Pending Bills | Anil Nauriya, 1988

- Local Bodies Cannot Sue for Libel | A G Noorani, 1992

- Law of Libel in Pakistan | A G Noorani, 2002

- Defamation and Public Advocacy | S P Sathe, 2003

- Judicial Meanderings in Patriarchal Thickets: Litigating Sex Discrimination in India | Kalpana Kannabiran, 2009

- Defamation and Its Real Dangers | EPW Editorial, 2011

- Browbeating Free Speech | Saurav Datta, 2013

- Legalising Defamation of Delinquent Borrowers | Shamba Dey, 2014

- Diminishing Values | Abir Dasgupta, 2017

- The Kejriwal Conundrum | EPW Editorial, 2018