What is Gestalt Psychology? Theory, Principles, & Examples

Nathalia Bustamante

Harvard Graduate School of Education

Nathalia Bustamante is a Brazilian journalist at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Key Takeaways

- Gestalt psychology is a school of thought that seeks to understand how the human brain perceives experiences. It suggests that structures, perceived as a whole, have specific properties that are different from the sum of their individual parts.

- For instance, when reading a text, a person perceives each word and sentence as a whole with meaning, rather than seeing individual letters; and while each letterform is an independent individual unit, the greater meaning of the text depends on the arrangement of the letters into a specific configuration.

- Gestalt grew from the field of psychology in the beginning of the 19th Century. Austrian and German psychologists started researching the human mind’s tendency to try to make sense of the world around us through automatic grouping and association.

- The Gestalt Principles, or Laws of Perception, explain how this behavior of “pattern seeking” operates. They offer a powerful framework to understand human perception, and yet are simple to assimilate and implement.

- For that reason, the Gestalt Laws are appealing not only to psychologists but also to visual artists, educators and communicators.

What Does Gestalt Mean?

In a loose translation, the German word ‘Gestalt’ (pronounced “ge-shtalt”) means ‘configuration’, or ‘structure’. It makes a reference to the way individual components are structured by our perception as a psychical whole (Wulf, 1996). That structure provides a scientific explanation for why changes in spacing, organization and timing can radically transform how information is received and assimilated.

How the Gestalt Approach Formed?

Two of the main philosophical influences of Gestalt are Kantian epistemology and Husserl’s phenomenological method.

Both Kant and Husserls sought to understand human consciousness and perceptions of the world, arguing that those mental processes are not entirely mediated by rational thought (Jorge, 2010).

Similarly, the Gestalt researchers Wertheimer, Koffka and Kohler observed that the human brain tends to automatically organize and interpret visual data through grouping.

They theorized that, because of those “mental shortcuts”, the perception of the whole is different from the sum of individual elements.

This idea that the whole is different from the sum of its parts – the central tenet of Gestalt psychology – challenged the then-prevailing theory of Structuralism .

This school of thought defended that mental processes should be broken down into their basic components, to focus on them individually.

Structuralists believed that complex perceptions could be understood by identifying the primitive sensations it caused – such as the points that make a square or particular pitches in a melody.

Gestalt, on the other hand, suggests the opposite path. It argues that the whole is grasped even before the brain perceives the individual parts – like when, looking at a photograph, we see the image of a face rather than a nose, two eyes, and the shape of a chin.

Therefore, to understand the subjective nature of human perception, we should transcend the specific parts to focus on the whole.

Gestalt Psychologists

Max wertheimer.

The inaugural article of Gestalt Psychology was Max Wertheimer’s Experimental Studies of the Perception of Movement , published in 1912.

Wertheimer, then at the Institute of Psychology in Frankfurt am Main, described a visual illusion called apparent motion in this article.

Apparent motion is the perception of movement that results from viewing a rapid sequence of static images, as happens in the movies or in flip books.

Wertheimer realized that the perception of the whole (the group of figures in a sequence) was radically different from the perception of its components (each static image).

Wolfgang Köhler

Wolfgang Köhler was particularly interested in physics and natural sciences. He introduced the concept of psychophysical isomorphism – arguing that how a stimulus is received is influenced by the brain’s general state while perceiving it (Shelvock, 2016).

He believed that organic processes tend to evolve to a state of equilibrium – like soap bubbles, that start in various shapes but always change into perfect spheres because that is their minimum energy state.

In the same way, the human brain would “converge” towards a minimum energy state through a process of simplifying perception – a mechanism that he called Pragnanz (Rock & Palmer, 1990).

Kurt Koffka

Koffka contributed to expanding Gestalt applications beyond visual perception. In his major article, Principles of Gestalt psychology (1935) he detailed the application of the Gestalt Laws to topics such as motor action, learning and memory, personality and society.

He also played a key role in taking the Gestalt Theory to the United States, to where he emigrated after the rise of Nazism in Germany.

Gestalt principles

Gestalt’s principles, or Laws of Perception, were formalized by Wertheimer in a treaty published in 1923, and further elaborated by Köhler, Koffka, and Metzger.

The principles are grounded on the human natural tendency of finding order in disorder – a process that happens in the brain, not in the sensory organs such as the eye. According to Wertheimer, the mind “makes sense” of stimulus captured by the eyes following a predictable set of principles.

The brain applies these principles to enable individuals to perceive uniform forms rather than simply collections of unconnected images.

Although these principles operate in a predictable way, they are actually mental shortcuts to interpreting information. As shortcuts, they sometimes make mistakes – and that is why they can lead to incorrect perceptions.

Prägnanz (law of simplicity)

- The law of Prägnanz is also called “law of simplicity” or “law of good figure”. It states that when faced with a set of ambiguous or complex objects, the human brain seeks to make them as simple as possible.

- The “good figure” is an object or image that can easily be perceived as a whole.

- A good example of this process is our perception of the Olympic logo. We tend to see overlapping circles (the simpler version) rather than a series of curved, connected lines (Dresp-Langley, 2015).

- This law suggests that we tend to group shapes, objects or design elements that share some similarity in terms of color, shape, orientation, texture or size.

- The law of proximity states that shapes, objects or design elements located near each other tend to be perceived as a group.

- Conversely, randomly located items tend to be perceived as isolated.

- This principle can be applied to direct attention to key elements within a design: the closer visual elements are to each other, the more likely they will be perceived as related to each other, and too much negative space between elements serve to isolate them from one another.

Common Region

- This law proposes that elements that are located within the same closed region – such as inside a circle or a shape – tend to be perceived as belonging to the same group.

- Those clearly defined boundaries between the inside and the outside of a shape create a stronger connection between elements, and can even overpower the law of Proximity or of Similarity.

- This law argues that shapes, objects or design elements that are positioned in a way that suggests lines, curves or planes will be perceived as such, and not as individual elements.

- We perceptually group the elements together to form a continuous image.

- This law suggests that the human brain has a natural tendency to visually close gaps in forms, particularly when identifying familiar images.

- When information is missing, our focus goes to what is present and automatically “fills” the missing parts with familiar lines, colors or patterns.

- Once a form has been identified, even if additional gaps are introduced, we still tend to visually complete the form, in order to make them stable.

- IBM’s iconic logo is one example of applied closure – blue horizontal lines are arranged in three stacks that we “close” to form the letterforms (Graham 2008).

The classic gestalt principles have been extended in various directions. The ones above are some of the most commonly cited, but there are others, such as the symmetry principle (symmetrical components will tend to be grouped together) and the common faith principle (elements tend to be perceived as grouped together if they move together).

Applications of Gestalt

Gestalt Psychology and the Laws of Perception influenced research from a multitude of disciplines – including linguistic, design, architecture and visual communication.

Gestalt Therapy

Gestalt therapy was founded by Frederick (Fritz) and Laura Perls in the 1940s. It focuses on the phenomenological method of awareness that distinguishes perceptions, feelings and actions from their interpretations.

It believes that explanations and interpretations are less reliable than the concrete – what is directly perceived and felt. It is a therapy rooted in dialogue, in which patients and therapists discuss differences in perspectives (Yontef, G, 1993).

Design Professor and specialist Gregg Berryman pointed out, in his book Notes on Graphic Design and Visual Communication (1979), that ‘Gestalt perceptual factors build a visual frame of reference which can provide the designer with a reliable psychological basis for the spatial organization of graphic information’.

In essence, Gestalt provided a framework of understanding upon which designers can make decisions.

What made gestalt theory appealing to visual artists and designers is its attempt to explain “pattern seeking” in human behavior.

The Gestalt Laws provided scientific validation of compositional structure, and were used by designers in the mid-twentieth century to explain and improve visual work.

They are particularly useful in the creation of posters, magazines, logos and billboards in a meaningful and organized way. More recently, they have also been applied to the design of websites, user interfaces and digital experiences (Graham 2008).

Product Development

The product’s form and other perceptual attributes such as color and texture are crucial in influencing customer’s buying decisions.

Product development has adopted Gestalt Laws in approaches that consider how the target customer will perceive the final product.

By considering these perceptions, the product developer is better able to understand potential risks, ambiguities and meanings of the product he or she is working on (Cziulik & Santos 2012).

Education and Learning

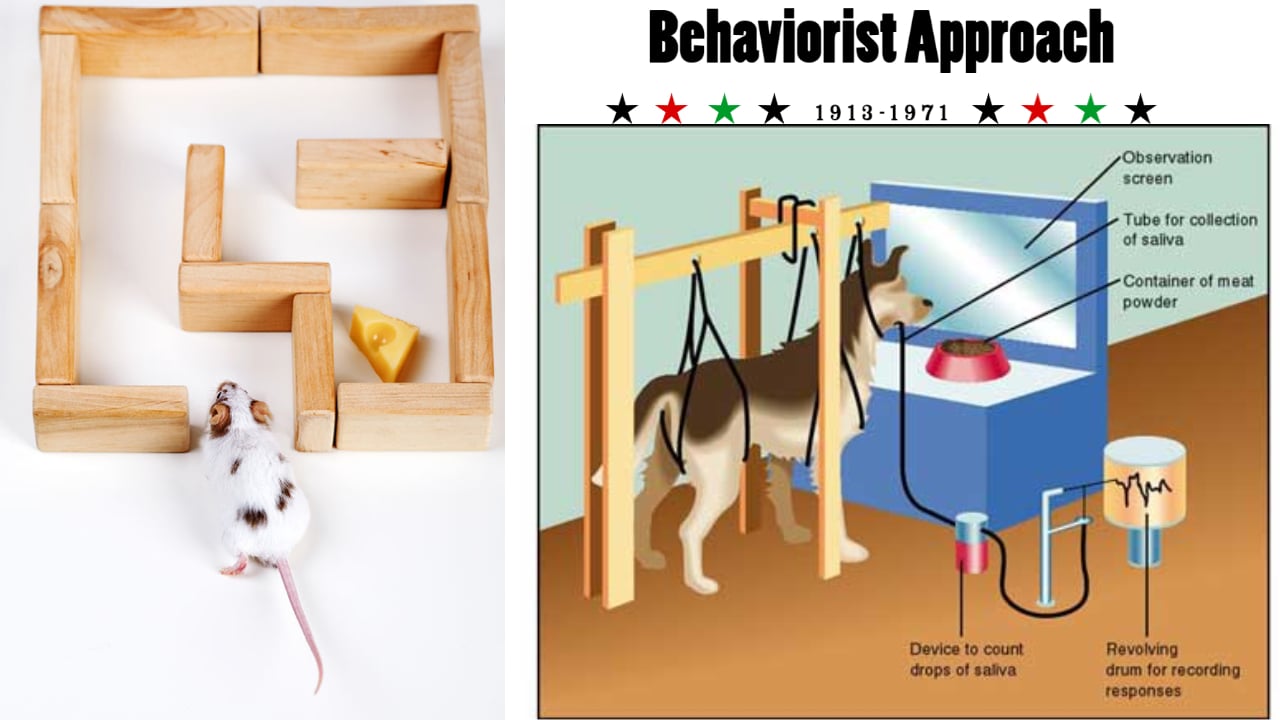

In Education, Gestalt Theory was applied as a reaction to behaviorism, which reduced experiences to simple stimulus-response reflections.

Gestalt suggested that students should perceive the whole of the learning goal, and then discover the relations between parts and the whole. That meant that teachers should provide the basic framework of the lesson as an organized and meaningful structure, and then go into details.

That would help students to understand the relation between contents and the overall goal of the lesson.

Problem-based learning methodologies also arose based on Gestalt principles.

When students are exposed to the whole of a problem, they can “make sense” of it before engaging in introspective thinking to analyze the connection between elements and craft independent solutions (Çeliköz et al. 2019).

The Gestalt Principles are applied to the design of advertisement, packaging and even physical stores.

Researchers that investigated how consumers form overall impressions of consumption objects found that they usually integrate visual information with their own evaluation of specific features (Zimmer & Golden, 1988).

More recent applications also analyze how consumer perceptions apply to online shopping environments. The fundamental Gestalt Laws are thus applied to site architecture and visual impact (Demangeot, 2010).

Gestalt Legacy

Most psychologists consider that the Gestalt School, as a theoretical field of study, died with its founding fathers in the 1940s. Two main reasons may have contributed to that decline.

The first reason are institutional and personal constraints: after they left Germany, Wetheimer, Koffka and Köhler obtained positions in which they could conduct research, but could not train PhDs.

At the same time, most of the students and researchers that had remained in Germany broadened the scope of their research beyond Gestalt topics.

The second reason for the decline of Gestalt Psychology were empirical findings dismantling Köhler’s electrical field theory that sought to explain the brain’s functioning.

Neuroscience and cognitive science emerged in the 1960s as stronger frameworks for explaining the functioning of the brain.

Still, nearly all psychology students can expect to find at least one chapter dedicated to Gestalt Psychology in their textbooks.

Similarly, fundamental questions about the subjective nature of perception and awareness are still addressed in contemporary scientific research – with the perks of counting on advanced methods that were not available for the Gestaltists in the first half of the XX Century (Wagemans et al, 2012).

Berryman, G. (1979). Notes on Graphic Design and Visual Communication. Los Altos. William Kaufmann. Inc., t979.

Cziulik, C., & dos Santos, F. L. (2011). An approach to define formal requirements into product development according to Gestalt principles. Product: Management and Development, 9(2), 89-100.

Çeliköz, N., Erisen, Y., & Sahin, M. (2019). Cognitive Learning Theories with Emphasis on Latent Learning, Gestalt and Information Processing Theories. Online Submission, 9(3), 18-33.

Demangeot, C., & Broderick, A. J. (2010). Consumer perceptions of online shopping environments: A gestalt approach. Psychology & Marketing, 27(2), 117-140.

Dresp-Langley, B. (2015). Principles of perceptual grouping: Implications for image-guided surgery. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1565.

Graham, L. (2008). Gestalt theory in interactive media design. Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences, 2(1).

Jorge, MLM. (2010) Implicaciones epistemológicas de la noción de forma en la psicología de la Gestalt. Revista de Historia de la Psicología. vol. 31, núm. 4 (diciembre)

O”Connor, Z. (2015). Colour, contrast and gestalt theories of perception: The impact in contemporary visual communications design. Color Research & Application, 40(1), 85-92.

Rock, I., & Palmer, S. (1990). The legacy of Gestalt psychology . Scientific American, 263(6), 84-91.

Shelvock, M. T. (2016). Gestalt theory and mixing audio. Innovation in Music II, 1-14.

Wagemans, J., Elder, J. H., Kubovy, M., Palmer, S. E., Peterson, M. A., Singh, M., & von der Heydt, R. (2012). A century of Gestalt psychology in visual perception : I. Perceptual grouping and figure–ground organization. Psychological bulletin, 138(6), 1172.

Yontef, G., & Simkin, J. (1993). Gestalt therapy: An introduction. Gestalt Journal Press.

Zimmer, M. R., & Golden, L. L. (1988). Impressions of retail stores: A content analysis of consume. Journal of retailing, 64(3), 265.

Further Information

Wagemans, J., Elder, J. H., Kubovy, M., Palmer, S. E., Peterson, M. A., Singh, M., & von der Heydt, R. (2012). A century of Gestalt psychology in visual perception: I. Perceptual grouping and figure–ground organization. Psychological bulletin, 138(6), 1172.

Raffagnino, R. (2019). Gestalt Therapy Effectiveness: A Systematic Review of Empirical Evidence. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 7(6), 66-83.

Related Articles

Soft Determinism In Psychology

Branches of Psychology

Social Action Theory (Weber): Definition & Examples

Adult Attachment , Personality , Psychology , Relationships

Attachment Styles and How They Affect Adult Relationships

Personality , Psychology

Big Five Personality Traits: The 5-Factor Model of Personality

Learning Theories , Psychology

Behaviorism In Psychology

Gestalt Theory: Understanding Perception and Organization

Gestalt theory, a psychological framework developed in the early 20th century by German psychologists Max Wertheimer, Wolfgang Köhler, and Kurt Koffka, provides valuable insights into how humans perceive and make sense of the world around them. The term “gestalt” itself translates to “form” or “whole” in German, emphasizing the theory’s focus on understanding patterns and configurations rather than isolated elements.

At its core, gestalt theory suggests that our minds naturally organize sensory information into meaningful wholes or coherent patterns. Instead of perceiving individual parts separately, we tend to perceive objects as complete entities with inherent relationships among their components. This holistic approach to perception allows us to recognize familiar objects and scenes effortlessly.

One of the fundamental principles of gestalt theory is known as “the law of proximity.” This principle states that elements that are close to each other tend to be perceived as belonging together. For example, when presented with a group of dots arranged closely in space, we will perceive them as forming a single shape or pattern rather than separate entities.

Overall, gestalt theory offers valuable insights into human perception and cognition by highlighting our innate tendency to organize sensory information into meaningful wholes. By understanding these underlying principles, we can gain a deeper appreciation for how our minds construct meaning from the world around us.

Overview of Gestalt Theory

Gestalt theory is a psychological framework that focuses on how people perceive and experience the world around them. It emphasizes that our perception is not simply a collection of individual elements, but rather, it is influenced by the way these elements are organized into meaningful patterns or “Gestalts.” In this section, we’ll delve into the key concepts and principles of Gestalt theory.

One fundamental principle of Gestalt theory is the idea that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. This means that when we perceive something, we don’t just see individual objects or elements in isolation. Instead, our minds automatically organize these elements into cohesive wholes. For example, when looking at a painting, we don’t focus solely on each brushstroke or color patch; instead, we perceive it as a complete image with its own unique meaning and emotional impact.

Another important concept in Gestalt theory is known as “figure-ground relationship.” According to this principle, our minds naturally separate visual stimuli into distinct figures (the objects of interest) and background (the surrounding context). This separation allows us to focus our attention on specific elements while simultaneously perceiving their relation to the broader environment. For instance, when observing a tree in a forest, we can distinguish it from the other trees and appreciate its form despite being surrounded by foliage.

Gestalt psychology also highlights the role of perceptual grouping in shaping our perception. Our brains tend to group similar elements together based on various factors such as proximity (objects close to each other are seen as related), similarity (objects that share common features are grouped together), continuity (we tend to perceive smooth curves rather than abrupt changes), and closure (our tendency to fill in missing information to create complete shapes).

Additionally, Gestalt theorists emphasize that perception involves more than just visual stimuli; it encompasses all aspects of human experience including auditory, tactile, olfactory sensations, and even abstract concepts. Gestalt theory suggests that our minds naturally organize and interpret these diverse stimuli in a holistic manner, seeking patterns, meaning, and coherence.

By understanding the principles of Gestalt theory, we can gain insights into how our perception works and how we make sense of the world around us. It offers valuable perspectives for fields such as psychology, design, art, and even problem-solving. As we explore further in this article, we’ll delve into specific examples and applications of Gestalt theory to better grasp its practical implications.

Remember, this section is just the beginning of our exploration into Gestalt theory. Stay tuned for more fascinating insights and real-world examples that will deepen your understanding of this influential psychological framework.

Key Principles of Gestalt Theory

Gestalt theory, coined by German psychologists in the early 20th century, is a school of thought that emphasizes how individuals perceive and interpret the world around them. In this section, we’ll delve into the key principles of Gestalt theory that shed light on our perceptual experiences.

- The Law of Proximity: According to the law of proximity, objects that are close to each other are perceived as belonging together. This principle highlights how our brains naturally group elements based on their physical closeness. For example, imagine a series of dots scattered randomly on a page. Our minds instinctively organize them into clusters or patterns based on their proximity.

- The Law of Similarity: The law of similarity states that objects with similar features tend to be grouped together in our perception. Whether it’s shape, color, size, or texture, similarities between elements influence how we perceive and categorize them. Think about an array of differently shaped fruits displayed at a farmers’ market; we tend to group similar fruits together based on their shared characteristics.

- The Law of Closure: The law of closure suggests that our brains have a tendency to complete incomplete shapes or figures by filling in missing information. Even when presented with fragmented visual stimuli, we unconsciously connect the dots and perceive them as whole objects or forms. This principle explains why we can identify familiar symbols like logos even when they’re partially obscured.

- The Law of Figure-Ground Relationship: The law of figure-ground relationship describes how we perceive an image by differentiating between the main object (the figure) and its background (the ground). Our minds automatically separate an object from its surroundings to create distinct focal points in our perception. For instance, when looking at a photograph against a textured backdrop, we effortlessly distinguish between the subject and its environment.

- The Law of Continuity:

The law of continuity posits that our brains prefer to perceive continuous, smooth patterns rather than abrupt changes or disruptions. This principle suggests that we tend to follow the smoothest path when perceiving visual information and that our minds naturally connect elements along a common pathway. For example, when observing a winding river, we perceive it as a continuous flow rather than separate segments.

Understanding these key principles of Gestalt theory gives us insights into how our minds organize and make sense of the world. By recognizing these fundamental principles, we can better appreciate the complexities of perception and apply them in various design disciplines such as graphic design, architecture, and psychology.

Perception and Organization in Gestalt Theory

When it comes to understanding how we perceive the world around us, Gestalt theory provides valuable insights. This theory highlights that our minds have a natural inclination to organize sensory information into meaningful patterns and wholes, rather than perceiving individual elements in isolation.

One key concept in Gestalt theory is the idea of “figure-ground” perception. It suggests that we instinctively separate objects or figures from their background, allowing us to focus our attention on what stands out. For example, imagine looking at a photograph of a person standing in front of a beautiful landscape. Our mind automatically distinguishes between the person (the figure) and the background scenery (the ground), enabling us to perceive each element separately.

Another important principle within Gestalt theory is the notion of “closure.” Our brains tend to fill in missing information or gaps when presented with incomplete stimuli. This means that even if we are only given fragments or partial shapes, we can still recognize them as complete objects. For instance, if you see an image consisting of several disconnected lines forming an incomplete square, your mind will likely perceive it as a whole square.

Furthermore, Gestalt theory emphasizes how our minds naturally seek simplicity and order in visual perception. The principle of “simplicity” suggests that we tend to interpret complex stimuli by organizing them into simpler forms or patterns. By doing so, we make sense of what we see and reduce cognitive load. For instance, when presented with a scatterplot graph displaying various data points, our brain might automatically group similar points together based on proximity or shape.

Overall, understanding perception and organization through the lens of Gestalt theory sheds light on how our minds process visual information. It reveals our innate ability to form coherent perceptions by grouping elements together based on their relationships and characteristics. By grasping these principles, we can gain deeper insights into human cognition and enhance various fields such as design, psychology, and even marketing.

Gestalt Laws and Their Applications

Let’s delve into the fascinating world of Gestalt theory and explore its laws and practical applications. Understanding these principles can provide valuable insights into how we perceive and interpret the world around us.

- Law of Proximity: According to this principle, objects that are close together tend to be perceived as a group or related. For instance, imagine a group of people standing in a line. Even though they are separate individuals, our brain automatically groups them together due to their proximity.

- Law of Similarity: The law of similarity states that objects that share similar visual characteristics, such as shape, size, color, or texture, are perceived as belonging to the same group. Consider a collection of circles and squares arranged randomly on a page; we instinctively group the circles together and the squares together based on their similarity.

- Law of Closure: This principle suggests that our minds tend to fill in missing information or gaps in order to perceive whole shapes or patterns. For example, if you see an incomplete circle with a small gap at the bottom, your brain will naturally complete it as a full circle.

- Law of Continuity: The law of continuity proposes that our brains prefer smooth and continuous lines rather than abrupt changes in direction or pattern. When presented with intersecting lines or curves, we perceive them as flowing continuously rather than disjoined segments.

- Law of Figure-Ground Relationship: This principle deals with how we distinguish between an object (figure) and its background (ground). Our brains tend to focus on one element while perceiving others as less prominent or secondary. Think about how you can easily differentiate between words on a page and the blank space surrounding them.

These laws have various real-world applications across different fields:

- Graphic Design: Designers often utilize Gestalt principles to create visually appealing layouts by leveraging proximity, similarity, closure, continuity techniques.

- Advertising: Advertisers use these laws to capture viewers’ attention and create memorable visuals that communicate their message effectively.

- User Experience (UX) Design: Applying Gestalt principles in UX design helps designers create intuitive interfaces, ensuring users can easily navigate through websites or applications.

- Psychology and Perception: The study of Gestalt theory has contributed significantly to our understanding of human perception and cognitive processes.

By recognizing the power of Gestalt laws and implementing them consciously, we can enhance communication, design, and overall user experience in various aspects of our lives.

Gestalt Therapy: A Practical Approach

When it comes to therapy, there are various approaches that aim to help individuals overcome challenges and improve their well-being. One such approach is Gestalt therapy, which focuses on the here and now, emphasizing self-awareness and personal responsibility. In this section, I’ll delve into the practical aspects of Gestalt therapy and how it can be applied in real-life situations.

- Awareness in the Present Moment: Gestalt therapy places great importance on being fully present in the current moment. This means paying attention to our thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations, and behaviors as they arise. By cultivating awareness of what is happening internally and externally, individuals can gain insight into their patterns of behavior and make more conscious choices.

For example, let’s say someone is struggling with anger management issues. Through Gestalt therapy techniques like focusing on bodily sensations associated with anger or exploring the underlying emotions triggering this response, individuals can develop a greater understanding of their anger triggers. This heightened awareness empowers them to respond differently in similar situations in the future.

- Taking Responsibility for One’s Actions: Another key aspect of Gestalt therapy is the emphasis on personal responsibility for one’s actions and choices. It encourages individuals to acknowledge that they have control over how they perceive situations and how they respond to them.

For instance, consider a person who constantly blames external circumstances for their unhappiness or lack of success. In Gestalt therapy sessions, they would be encouraged to explore their role in creating these outcomes and take ownership of their choices. By recognizing their ability to make different decisions or change perspectives, individuals become active participants in shaping their own lives.

- Integration of Parts: Gestalt therapists often work with clients to help integrate different parts of themselves that may feel disconnected or conflicting. This involves exploring inner dialogue between these parts and finding ways to bring them together harmoniously.

Let’s imagine someone struggling with indecisiveness and feeling torn between different desires or values. Through Gestalt therapy techniques like the “empty chair” exercise, where individuals have a dialogue with imagined aspects of themselves, they can explore conflicting thoughts and emotions. This process facilitates self-acceptance and integration, leading to greater clarity and decision-making ability.

In summary, Gestalt therapy offers a practical approach to personal growth and healing by focusing on present awareness, taking responsibility for one’s actions, and integrating different parts of oneself. By incorporating these principles into therapeutic practice, individuals can develop a deeper understanding of themselves and work towards making positive changes in their lives.

Critiques and Controversies Surrounding Gestalt Theory

When it comes to the field of psychology, Gestalt theory has undoubtedly made its mark. However, like any prominent theory, it is not without its fair share of critiques and controversies. Let’s delve into a few key points that have sparked debate among scholars and researchers.

- Reductionism: One criticism often leveled against Gestalt theory is its perceived lack of emphasis on reductionism. Some argue that the holistic approach advocated by Gestalt psychologists undermines the importance of breaking down complex psychological processes into smaller components for analysis. Critics contend that this limits our understanding of human behavior and cognition.

- Subjectivity and Interpretation: Another point of contention revolves around the subjective nature of perception in Gestalt theory. While proponents highlight how individuals actively organize sensory information into meaningful patterns, skeptics argue that interpretation plays a significant role in determining these patterns. This subjectivity raises questions about the reliability and universality of perceptual organization principles proposed by Gestalt psychologists.

- Empirical Evidence: In scientific circles, rigorous empirical evidence holds great significance when evaluating theories. Some critics claim that the experimental support for certain aspects of Gestalt theory is limited or inconclusive. They argue that more research is needed to validate some fundamental assertions put forth by this influential school of thought.

- Cultural Bias: A recurring concern within critiques surrounding many psychological theories is their potential cultural bias. Similar concerns arise with respect to Gestalt theory, as some scholars question whether its principles are applicable across diverse cultural contexts or if they are rooted in Western perspectives alone.

- Integration with Other Theories: Lastly, there are debates about how well Gestalt theory integrates with other branches of psychology and related disciplines such as neuroscience or cognitive psychology. Critics argue that despite its contributions, the gestalt framework might not fully account for all aspects of human behavior and cognition when considered alongside other theoretical frameworks.

It’s important to note that these criticisms and controversies do not negate the valuable contributions made by Gestalt theory. Rather, they serve as thought-provoking avenues for further exploration and refinement of our understanding of human perception and cognition.

In the next section, we’ll explore some real-world applications of Gestalt theory in various fields to showcase its practical relevance. Stay tuned!

Influence of Gestalt Theory on Modern Psychology

Gestalt theory, with its emphasis on the whole being greater than the sum of its parts, has had a profound influence on modern psychology. By examining how individuals perceive and interpret information, Gestalt theory has provided key insights into human cognition and behavior. Let’s delve into some examples that highlight the impact of this theory.

- Perception and Organization: Gestalt psychologists emphasized that our minds have an innate tendency to organize sensory stimuli into meaningful patterns. An example of this is the concept of figure-ground perception, where we naturally distinguish between objects (figures) and their surrounding background (ground). This understanding has greatly influenced research in visual perception, advertising design, and even user interface development.

- Problem-Solving and Insight: Gestalt theory also sheds light on problem-solving processes by emphasizing the role of insight or “aha” moments. According to this perspective, problem-solving involves restructuring our mental representation of a problem to achieve a sudden realization of the solution. This notion has informed various fields like education, cognitive psychology, and creativity studies.

- Holistic Approach in Therapy: The principles of Gestalt therapy align closely with its theoretical counterpart. Instead of focusing solely on isolated symptoms or behaviors, therapists using this approach aim to understand clients as integrated beings within their environment. The therapeutic process focuses on fostering self-awareness, personal growth, and enhancing relationships through exploring emotions in the present moment.

- Social Perception: Gestalt principles extend beyond individual perception to social contexts as well. Social psychologists have applied these ideas to explore how people form impressions about others based on fragmented information or cues they receive when encountering someone for the first time. This research highlights how our minds automatically fill in missing details to create a more coherent understanding of others’ personalities.

- Group Dynamics: Understanding group dynamics is another area significantly influenced by Gestalt theory concepts such as proximity, similarity, and closure. These principles help explain how individuals form affiliations, make group decisions, and perceive themselves as part of a larger collective. Such insights have informed fields like organizational psychology and leadership development.

Gestalt theory has left an indelible mark on modern psychology by offering novel perspectives on perception, problem-solving, therapy, social cognition, and group dynamics. Its holistic approach continues to shape our understanding of human behavior and enrich various domains within the field of psychology.

In this article, we have explored the fascinating concept of Gestalt theory and its impact on psychology and perception. Let’s summarize the key points we’ve discussed:

- Perception is more than the sum of its parts: According to Gestalt theory, our minds naturally organize sensory information into meaningful patterns and wholes. We perceive objects as unified entities rather than a collection of individual elements.

- The principles of Gestalt theory: We have examined several fundamental principles that govern how we perceive visual stimuli, including figure-ground relationship, proximity, similarity, closure, and continuity. These principles help us make sense of the world around us and facilitate efficient processing of visual information.

- Applications in various fields: Gestalt theory has found applications in many domains beyond psychology. It has influenced art, design, advertising, user experience (UX) design, and even problem-solving techniques. Understanding how people perceive and interpret visual information can greatly enhance communication and effectiveness in these areas.

- Limitations and criticisms: While Gestalt theory offers valuable insights into perception, it also faces criticism for oversimplifying complex cognitive processes. Some argue that it neglects other factors such as attention and memory that influence perception.

- Ongoing research: Despite being introduced over a century ago, researchers continue to explore the intricacies of Gestalt theory and its implications today. Advancements in neuroscience allow us to delve deeper into understanding how our brains process visual stimuli.

In conclusion,

Gestalt theory provides a framework for understanding how our minds organize sensory information to create meaningful perceptions of the world around us. By studying these perceptual principles, we gain insights into human cognition that can be applied across various disciplines.

Remembering that perception is not simply about individual elements but about the whole picture helps designers create visually appealing graphics or interfaces while advertisers use this knowledge to engage their target audience effectively.

As technology advances further and our understanding grows deeper through ongoing research efforts, we can expect to uncover even more about the intricacies of perception and its implications for our daily lives.

So, next time you marvel at a beautiful painting or get captivated by an engaging advertisement, remember that Gestalt theory plays a significant role in shaping your perception.

Related Posts

What Is Hedonic Adaptation and How Does It Affect Us?

How to Date Someone with BPD: Navigating Relationships

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

12.1.2: Restructuring – The Gestalt Approach

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 92780

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

One dominant approach to Problem Solving originated from Gestalt psychologists in the 1920s. Their understanding of problem solving emphasises behaviour in situations requiring relatively novel means of attaining goals and suggests that problem solving involves a process called restructuring. Since this indicates a perceptual approach, two main questions have to be considered:

- How is a problem represented in a person's mind?

- How does solving this problem involve a reorganisation or restructuring of this representation?

This is what we are going to do in the following part of this section.

How is a problem represented in the mind?

In current research internal and external representations are distinguished: The first kind is regarded as the knowledge and structure of memory , while the latter type is defined as the knowledge and structure of the environment, such like physical objects or symbols whose information can be picked up and processed by the perceptual system autonomously. On the contrary the information in internal representations has to be retrieved by cognitive processes.

Generally speaking, problem representations are models of the situation as experienced by the agent. Representing a problem means to analyse it and split it into separate components:

- objects, predicates

- state space

- selection criteria

Therefore the efficiency of Problem Solving depends on the underlying representations in a person’s mind, which usually also involves personal aspects. Analysing the problem domain according to different dimensions, i.e., changing from one representation to another, results in arriving at a new understanding of a problem. This is basically what is described as restructuring. The following example illustrates this:

The key in this story is that the older boy restructured the problem and found out that he used an attitude towards the younger which made it difficult to keep him playing. With the new type of game the problem is solved: the older is not bored, the younger not frustrated.

Possibly, new representations can make a problem more difficult or much easier to solve. To the latter case insight – the sudden realisation of a problem’s solution – seems to be related.

There are two very different ways of approaching a goal-oriented situation . In one case an organism readily reproduces the response to the given problem from past experience. This is called reproductive thinking .

The second way requires something new and different to achieve the goal, prior learning is of little help here. Such productive thinking is (sometimes) argued to involve insight . Gestalt psychologists even state that insight problems are a separate category of problems in their own right.

Tasks that might involve insight usually have certain features – they require something new and non-obvious to be done and in most cases they are difficult enough to predict that the initial solution attempt will be unsuccessful. When you solve a problem of this kind you often have a so called "AHA-experience" – the solution pops up all of a sudden. At one time you do not have any ideas of the answer to the problem, you do not even feel to make any progress trying out different ideas, but in the next second the problem is solved.

For all those readers who would like to experience such an effect, here is an example for an Insight Problem: Knut is given four pieces of a chain; each made up of three links. The task is to link it all up to a closed loop and he has only 15 cents. To open a link costs 2, to close a link costs 3 cents. What should Knut do?

If you want to know the correct solution, click to enlarge the image.

To show that solving insight problems involves restructuring , psychologists created a number of problems that were more difficult to solve for participants provided with previous experiences, since it was harder for them to change the representation of the given situation (see Fixation ). Sometimes given hints may lead to the insight required to solve the problem. And this is also true for involuntarily given ones. For instance it might help you to solve a memory game if someone accidentally drops a card on the floor and you look at the other side. Although such help is not obviously a hint, the effect does not differ from that of intended help.

For non-insight problems the opposite is the case. Solving arithmetical problems, for instance, requires schemas , through which one can get to the solution step by step.

Sometimes, previous experience or familiarity can even make problem solving more difficult. This is the case whenever habitual directions get in the way of finding new directions – an effect called fixation .

Functional fixedness

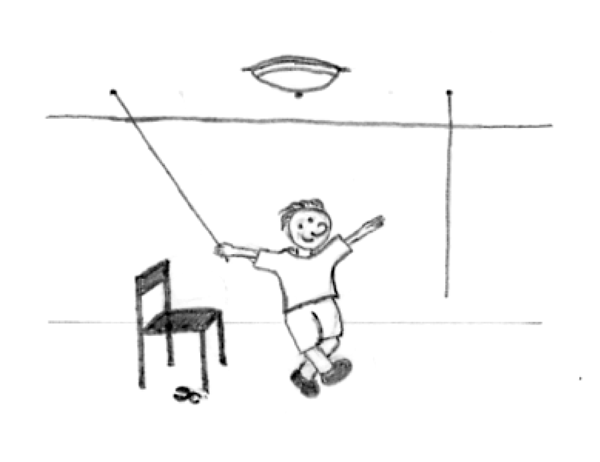

Functional fixedness concerns the solution of object-use problems . The basic idea is that when the usual way of using an object is emphasised, it will be far more difficult for a person to use that object in a novel manner. An example for this effect is the candle problem : Imagine you are given a box of matches, some candles and tacks. On the wall of the room there is a cork-board. Your task is to fix the candle to the cork-board in such a way that no wax will drop on the floor when the candle is lit. – Got an idea?

A further example is the two-string problem : Knut is left in a room with a chair and a pair of pliers given the task to bind two strings together that are hanging from the ceiling. The problem he faces is that he can never reach both strings at a time because they are just too far away from each other. What can Knut do?

Mental fixedness

Functional fixedness as involved in the examples above illustrates a mental set – a person’s tendency to respond to a given task in a manner based on past experience. Because Knut maps an object to a particular function he has difficulties to vary the way of use (pliers as pendulum's weight).

One approach to studying fixation was to study wrong-answer verbal insight problems . It was shown that people tend to give rather an incorrect answer when failing to solve a problem than to give no answer at all.

These wrong solutions are due to an inaccurate interpretation , hence representation , of the problem. This can happen because of sloppiness (a quick shallow reading of the problem and/or weak monitoring of their efforts made to come to a solution). In this case error feedback should help people to reconsider the problem features, note the inadequacy of their first answer, and find the correct solution. If, however, people are truly fixated on their incorrect representation, being told the answer is wrong does not help. In a study made by P.I. Dallop and R.L. Dominowski in 1992 these two possibilities were contrasted. In approximately one third of the cases error feedback led to right answers, so only approximately one third of the wrong answers were due to inadequate monitoring . [1]

Another approach is the study of examples with and without a preceding analogous task. In cases such like the water-jug task analogous thinking indeed leads to a correct solution, but to take a different way might make the case much simpler:

In fact participants faced with the 100 litre task first choose a complicate way in order to solve the second one. Others on the contrary who did not know about that complex task solved the 18 litre case by just adding three litres to 15.

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- PubMed/Medline

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Gestalt’s perspective on insight: a recap based on recent behavioral and neuroscientific evidence.

1. Introduction

2. the role of perceptual experience in problem-solving cognition: was the parallelism between bistable figures and insight problem-solving warranted, 3. the holistic approach: what has recent research discovered about the idea that solutions to problems sometimes come to mind in an off-on manner.

Using Koffka ’s ( 1935, p. 176 ) words: “The whole is something else than the sum of its parts, because summing is a meaningless procedure, whereas the whole-part relationship is meaningful”. Similarly, insight problem-solving is processed in a discrete off–on manner, and when solutions to problems emerge, they do so as a “whole”, and the solver cannot retroactively report the reasoning process that led him or her to the solution.

4. The Gestalt Psychologists Assume That the Solution to Problems Comes “With Sudden Clarity.” Can We See in This Statement a Proto-Assumption That Insightful Solutions Might Be Characterized by a Perception of Higher Accuracy?

5. conclusions and future directions, author contributions, institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, data availability statement, conflicts of interest.

- Becker, Maxi, Simone Kühn, and Tobias Sommer. 2021. Verbal insight revisited—Dissociable neurocognitive processes underlying solutions accompanied by an AHA! experience with and without prior restructuring. Journal of Cognitive Psychology 33: 659–84. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Beversdorf, D. Q., J. D. Hughes, B. A. Steinberg, L. D. Lewis, and K. M. Heilman. 1999. Noradrenergic modulation of cognitive flexibility in problem-solving. Neuroreport 10: 2763–67. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Bianchi, Ivana, Erika Branchini, Roberto Burro, Elena Capitani, and Ugo Savardi. 2020. Overtly prompting people to “think in opposites” supports insight problem-solving. Thinking & Reasoning 26: 31–67. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bijleveld, Erik, Ruud Custers, and Henk A. G. Aarts. 2009. The unconscious eye opener: Pupil dilation reveals strategic recruitment of resources upon presentation of subliminal reward cues. Psychological Science 20: 1313–15. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Bowden, Edward M., Mark Jung-Beeman, Jessica Fleck, and John Kounios. 2005. New approaches to demystifying insight. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 9: 322–28. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Campbell, Heather L., Madalina E. Tivarus, Ashleigh Hillier, and David Q. Beversdorf. 2008. Increased task difficulty results in greater impact of noradrenergic modulation of cognitive flexibility. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior 88: 222–29. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Chapman, C. Richard, Shunichi Oka, David H. Bradshaw, Robert C. Jacobson, and Gary W. Donaldson. 1999. Phasic pupil dilation response to noxious stimulation in normal volunteers: Relationship to brain evoked potentials and pain report. Psychophysiology 36: 44–52. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Corbetta, Maurizio, Gaurav Patel, and Gordon L. Shulman. 2008. The reorienting system of the human brain: From environment to theory of mind. Neuron 58: 306–24. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Coull, Jennifer T., Christian Büchel, Karl J. Friston, and Chris D. Frith. 1999. Noradrenergically mediated plasticity in a human attentional neuronal network. NeuroImage 10: 705–15. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Danek, Amory H. 2018. Magic tricks, sudden restructuring, and the Aha! experience: A new model of nonmonotonic problem-solving. In Insight . London: Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Danek, Amory H., and Carola Salvi. 2018. Moment of Truth: Why Aha! Experiences are Correct. The Journal of Creative Behavior 54: 484–86. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Danek, Amory H., and Jasmin M. Kizilirmak. 2021. The whole is more than the sum of its parts—Addressing insight problem solving concurrently from a cognitive and an affective perspective. Journal of Cognitive Psychology 33: 609–15. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Danek, Amory H., and Jennifer Wiley. 2017. What about False Insights? Deconstructing the Aha! Experience along Its Multiple Dimensions for Correct and Incorrect Solutions Separately. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 2077. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Danek, Amory H., Thomas Fraps, Albrecht von Müller, Benedikt Grothe, and Michael Öllinger. 2014. Working Wonders? Investigating insight with magic tricks. Cognition 130: 174–85. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- de Rooij, Alwin, Ruben D. Vromans, and Matthijs Dekker. 2018. Noradrenergic modulation of creativity: Evidence from pupillometry. Creativity Research Journal 30: 339–51. [ Google Scholar ]

- Duncan, Seth, and Lisa Feldman Barrett. 2007. The role of the amygdala in visual awareness. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 11: 190–92. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Einhäuser, Wolfgang, James Stout, Christof Koch, and Olivia Carter. 2008. Pupil dilation reflects perceptual selection and predicts subsequent stability in perceptual rivalry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105: 1704–09. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Ellen, Paul. 1982. Direction, experience, and hints in creative problem solving: Reply to Weisberg and Alba. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 111: 316–25. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Feldman, Harriet, and Karl Friston. 2010. Attention, Uncertainty, and Free Energy. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 4: 215. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Friston, Karl. 2009. The free-energy principle: A rough guide to the brain? Trends in Cognitive Sciences 13: 293–301. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Friston, Karl, Thomas FitzGerald, Francesco Rigoli, Philipp Schwartenbeck, and Giovanni Pezzulo. 2017. Active Inference: A Process Theory. Neural Computation 29: 1–49. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Friston, Karl, Thomas FitzGerald, Francesco Rigoli, Philipp Schwartenbeck, John O’Doherty, and Giovanni Pezzulo. 2016a. Active inference and learning. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 68: 862–79. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Friston, Karl, Vladimir Litvak, Ashwini Oswal, Adeel Razi, Klaas E. Stephan, Bernadette C. M. van Wijk, Gabriel Ziegler, and Peter Zeidman. 2016b. Bayesian model reduction and empirical Bayes for group (DCM) studies. Neuroimage 128: 413–31. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Haarsma, J., P. C. Fletcher, J. D. Griffin, H. J. Taverne, H. Ziauddeen, T. J. Spencer, C. Miller, T. Katthagen, I. Goodyer, K. M. J. Diederen, and et al. 2021. Precision weighting of cortical unsigned prediction error signals benefits learning, is mediated by dopamine, and is impaired in psychosis. Molecular Psychiatry 26: 9. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hedne, Mikael R., Elisabeth Norman, and Janet Metcalfe. 2016. Intuitive Feelings of Warmth and Confidence in Insight and Noninsight Problem Solving of Magic Tricks. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 1314. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Jung-Beeman, Mark, Edward M. Bowden, Jason Haberman, Jennifer L. Frymiare, Stella Arambel-Liu, Richard Greenblatt, Paul J. Reber, and John Kounios. 2004. Neural activity when people solve verbal problems with insight. PLoS Biology 2: 500–10. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kietzmann, Tim C., Stephan Geuter, and Peter König. 2011. Overt Visual Attention as a Causal Factor of Perceptual Awareness. PLoS ONE 6: e22614. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Koch, Christof, and Naotsugu Tsuchiya. 2007. Attention and consciousness: Two distinct brain processes. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 11: 16–22. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Koffka, Kurt. 1935. Principles of Gestalt Psychology . Brace: Harcourt. [ Google Scholar ]

- Köhler, Wolfgang. 1925. The Mentality of Apes . Brace: Harcourt, p. viii+, 342. [ Google Scholar ]

- Korovkin, Sergei, Anna Savinova, Julia Padalka, and Anastasia Zhelezova. 2021. Beautiful mind: Grouping of actions into mental schemes leads to a full insight Aha! experience. Journal of Cognitive Psychology 33: 620–30. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kounios, John, and Mark Beeman. 2009. The Aha! Moment: The Cognitive Neuroscience of Insight. Current Directions in Psychological Science 18: 210–16. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kounios, John, and Mark Beeman. 2014. The Cognitive Neuroscience of Insight. Annual Review of Psychology 65: 71–93. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kounios, John, Jennifer L. Frymiare, Edward M. Bowden, Jessica I. Fleck, Karuna Subramaniam, Todd B. Parrish, and Mark Jung-Beeman. 2006. The prepared mind: Neural activity prior to problem presentation predicts subsequent solution by sudden insight. Psychological Science 17: 882–90. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Kounios, John, Jessica I. Fleck, Deborah L. Green, Lisa Payne, Jennifer L. Stevenson, Edward M. Bowden, and Mark Jung-Beeman. 2008. The Origins of Insight in Resting-State Brain Activity. Neuropsychologia 46: 281–91. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Laeng, Bruno, and Dinu-Stefan Teodorescu. 2002. Eye scanpath during visual imagery reenact those of perception of the same visual scene. Cognitive Science 26: 207–31. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Laukkonen, Ruben E., and Jason M. Tangen. 2017. Can observing a Necker cube make you more insightful? Consciousness and Cognition: An International Journal 48: 198–211. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Laukkonen, Ruben E., Benjamin T. Kaveladze, Jason M. Tangen, and Jonathan W. Schooler. 2020. The dark side of Eureka: Artificially induced Aha moments make facts feel true. Cognition 196: 104122. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Laukkonen, Ruben E., Daniel J. Ingledew, Hilary J. Grimmer, Jonathan W. Schooler, and Jason M. Tangen. 2021. Getting a grip on insight: Real-time and embodied Aha experiences predict correct solutions. Cognition and Emotion 35: 918–35. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Laukkonen, Ruben E., Margaret Webb, Carola Salvi, Jason M. Tangen, Heleen A. Slagter, and Jonathan W. Schooler. 2023. Insight and the selection of ideas. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 153: 105363. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Maier, N. R. F. 1940. The behavior mechanisms concerned with problem solving. Psychological Review 47: 43–58. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Metcalfe, Janet. 1986. Feeling of knowing in memory and problem solving. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 12: 288–94. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Mungan, Esra. 2023. Gestalt theory: A revolution put on pause? Prospects for a paradigm shift in the psychological sciences. New Ideas in Psychology 71: 101036. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Oh, Yongtaek, Christine Chesebrough, Brian Erickson, Fengqing Zhang, and John Kounios. 2020. An insight-related neural reward signal. NeuroImage 214: 116757. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Salvi, Carola. 2023. Markers of Insight. Available online: https://osf.io/preprints/psyarxiv/73y5k (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Salvi, Carola, and Edward M. Bowden. 2016. Looking for creativity: Where do we look when we look for new ideas? Frontiers in Psychology 7: 161. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Salvi, Carola, Claudio Simoncini, Jordan Grafman, and Mark Beeman. 2020. Oculometric signature of switch into awareness? Pupil size predicts sudden insight whereas microsaccades predict problem-solving via analysis. NeuroImage 217: 116933. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Salvi, Carola, Emanuela Bricolo, John Kounios, Edward Bowden, and Mark Beeman. 2016. Insight solutions are correct more often than analytic solutions. Thinking & Reasoning 22: 443–60. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Salvi, Carola, Emanuela Bricolo, Steven L. Franconeri, John Kounios, and Mark Beeman. 2015. Sudden insight is associated with shutting out visual inputs. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review 22: 1814–19. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Salvi, Carola, Emily K. Leiker, Beatrix Baricca, Maria A. Molinari, Roberto Eleopra, Paolo F. Nichelli, Jordan Grafman, and Joseph E. Dunsmoor. 2021. The Effect of Dopaminergic Replacement Therapy on Creative Thinking and Insight Problem-Solving in Parkinson’s Disease Patients. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 646448. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Sara, Susan J. 2009. The locus coeruleus and noradrenergic modulation of cognition. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience 10: 211–23. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Sara, Susan J., and Sebastien Bouret. 2012. Orienting and reorienting: The locus coeruleus mediates cognition through arousal. Neuron 76: 130–41. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Smith, Roderick W., and John Kounios. 1996. Sudden insight: All-or-none processing revealed by speed-accuracy decomposition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 22: 1443–62. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Thorndike, Edward L. 1911. Animal Intelligence: Experimental Studies . New York: Macmillan. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tik, Martin, Ronald Sladky, Caroline Di Bernardi Luft, David Willinger, André Hoffmann, Michael J. Banissy, Joydeep Bhattacharya, and Christian Windischberger. 2018. Ultra-high-field fMRI insights on insight: Neural correlates of the Aha!-moment. Human Brain Mapping 39: 3241–52. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Webb, Margaret E., Daniel R. Little, and Simon J. Cropper. 2016. Insight Is Not in the Problem: Investigating Insight in Problem Solving across Task Types. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 1424. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Weisberg, Robert. 1986. Creativity: Genius and Other Myths . New York: W H Freeman/Times Books/Henry Holt & Co., p. 169. [ Google Scholar ]

- Weisberg, Robert W., and Joseph W. Alba. 1981. An examination of the alleged role of “fixation” in the solution of several “insight” problems. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 110: 169–92. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Weisberg. 2018. Problem solving. In The Routledge International Handbook of Thinking and Reasoning . Edited by L. J. Ball and V. A. Thompson. Routledge: Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 607–23. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wertheimer, Max. 1923. Untersuchungen zur Lehre von der Gestalt. II. Psychologische Forschung 4: 301–50. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wertheimer, Max. 1959. Productive Thinking . New York: Harper, p. xvi, 302. [ Google Scholar ]

| The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

Share and Cite

Vitello, M.; Salvi, C. Gestalt’s Perspective on Insight: A Recap Based on Recent Behavioral and Neuroscientific Evidence. J. Intell. 2023 , 11 , 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence11120224

Vitello M, Salvi C. Gestalt’s Perspective on Insight: A Recap Based on Recent Behavioral and Neuroscientific Evidence. Journal of Intelligence . 2023; 11(12):224. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence11120224

Vitello, Mary, and Carola Salvi. 2023. "Gestalt’s Perspective on Insight: A Recap Based on Recent Behavioral and Neuroscientific Evidence" Journal of Intelligence 11, no. 12: 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence11120224

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Gestalt psychology is a school of thought that seeks to understand how the human brain perceives experiences. It suggests that structures, perceived as a whole, have specific properties that are different from the sum of their individual parts.

One dominant approach to Problem Solving originated from Gestalt psychologists in the 1920s. Their understanding of problem solving emphasises behaviour in situations requiring relatively novel means of attaining goals and suggests that problem solving involves a process called restructuring.

Problem-Solving and Insight: Gestalt theory also sheds light on problem-solving processes by emphasizing the role of insight or “aha” moments. According to this perspective, problem-solving involves restructuring our mental representation of a problem to achieve a sudden realization of the solution.

One dominant approach to Problem Solving originated from Gestalt psychologists in the 1920s. Their understanding of problem solving emphasises behaviour in situations requiring relatively novel means of attaining goals and suggests that problem solving involves a process called restructuring.

The Gestalt psychologists’ theory of insight problem-solving was based on a direct parallelism between perceptual experience and higher-order forms of cognition (e.g., problem-solving).

This Gestalt theory of problem solving provides a sketchy high-level description of cre-ative problem solving, but no detailed psychological mechanism (especially process-based or computational mechanism) has been proposed. More recent research has turned to finding evidence supporting the existence of the individual stages of creative problem ...

in the last two decades, scientists have gained a deeper understanding of insight problem-solving due to the advancements in cognitive neuroscience. This review aims to provide a retrospective reading of Gestalt theory based on the knowledge accrued by adopting novel paradigms of research and investigating their neurophysiological correlates.

The gestalt psychologists proposed that restructuring (Umstrukturierung) is an essential process in thinking. This concept has not been integrated into the information-processing theory of problem solving.

The Gestalt account of problem-solving tells us that the structural quality of our perception assists the solution process, and when we fail to solve problems, this amounts to a failure to perceive the structure of the problem situation.

Abstract. Responds to the position of P. Ellen (see record 1983-07232-001) that Gestalt theory is the preferred explanation of productive problem solving. The present authors argue that one would not expect perfect transfer from their (see record 1982-02567-001) 4-dot training problem to the classic 9-dot problem.