When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write Your Methods

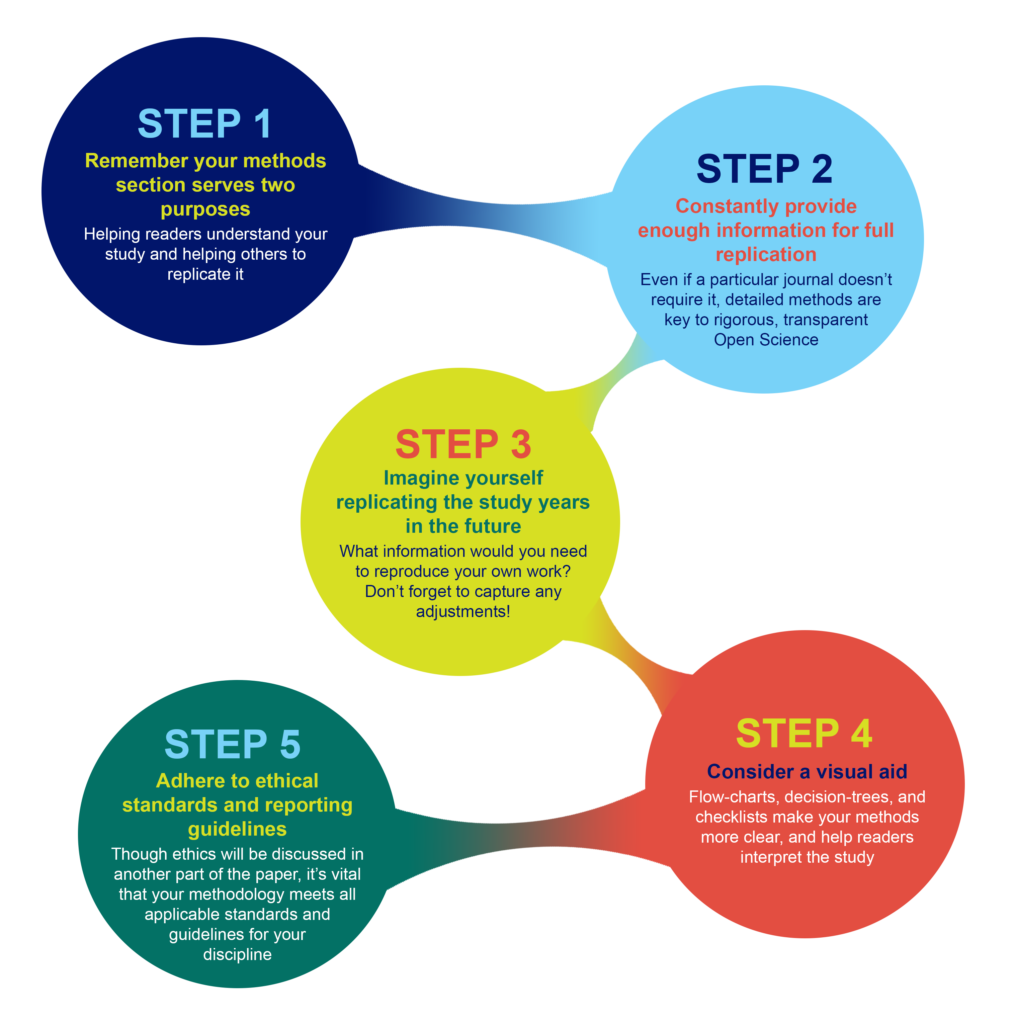

Ensure understanding, reproducibility and replicability

What should you include in your methods section, and how much detail is appropriate?

Why Methods Matter

The methods section was once the most likely part of a paper to be unfairly abbreviated, overly summarized, or even relegated to hard-to-find sections of a publisher’s website. While some journals may responsibly include more detailed elements of methods in supplementary sections, the movement for increased reproducibility and rigor in science has reinstated the importance of the methods section. Methods are now viewed as a key element in establishing the credibility of the research being reported, alongside the open availability of data and results.

A clear methods section impacts editorial evaluation and readers’ understanding, and is also the backbone of transparency and replicability.

For example, the Reproducibility Project: Cancer Biology project set out in 2013 to replicate experiments from 50 high profile cancer papers, but revised their target to 18 papers once they understood how much methodological detail was not contained in the original papers.

What to include in your methods section

What you include in your methods sections depends on what field you are in and what experiments you are performing. However, the general principle in place at the majority of journals is summarized well by the guidelines at PLOS ONE : “The Materials and Methods section should provide enough detail to allow suitably skilled investigators to fully replicate your study. ” The emphases here are deliberate: the methods should enable readers to understand your paper, and replicate your study. However, there is no need to go into the level of detail that a lay-person would require—the focus is on the reader who is also trained in your field, with the suitable skills and knowledge to attempt a replication.

A constant principle of rigorous science

A methods section that enables other researchers to understand and replicate your results is a constant principle of rigorous, transparent, and Open Science. Aim to be thorough, even if a particular journal doesn’t require the same level of detail . Reproducibility is all of our responsibility. You cannot create any problems by exceeding a minimum standard of information. If a journal still has word-limits—either for the overall article or specific sections—and requires some methodological details to be in a supplemental section, that is OK as long as the extra details are searchable and findable .

Imagine replicating your own work, years in the future

As part of PLOS’ presentation on Reproducibility and Open Publishing (part of UCSF’s Reproducibility Series ) we recommend planning the level of detail in your methods section by imagining you are writing for your future self, replicating your own work. When you consider that you might be at a different institution, with different account logins, applications, resources, and access levels—you can help yourself imagine the level of specificity that you yourself would require to redo the exact experiment. Consider:

- Which details would you need to be reminded of?

- Which cell line, or antibody, or software, or reagent did you use, and does it have a Research Resource ID (RRID) that you can cite?

- Which version of a questionnaire did you use in your survey?

- Exactly which visual stimulus did you show participants, and is it publicly available?

- What participants did you decide to exclude?

- What process did you adjust, during your work?

Tip: Be sure to capture any changes to your protocols

You yourself would want to know about any adjustments, if you ever replicate the work, so you can surmise that anyone else would want to as well. Even if a necessary adjustment you made was not ideal, transparency is the key to ensuring this is not regarded as an issue in the future. It is far better to transparently convey any non-optimal methods, or methodological constraints, than to conceal them, which could result in reproducibility or ethical issues downstream.

Visual aids for methods help when reading the whole paper

Consider whether a visual representation of your methods could be appropriate or aid understanding your process. A visual reference readers can easily return to, like a flow-diagram, decision-tree, or checklist, can help readers to better understand the complete article, not just the methods section.

Ethical Considerations

In addition to describing what you did, it is just as important to assure readers that you also followed all relevant ethical guidelines when conducting your research. While ethical standards and reporting guidelines are often presented in a separate section of a paper, ensure that your methods and protocols actually follow these guidelines. Read more about ethics .

Existing standards, checklists, guidelines, partners

While the level of detail contained in a methods section should be guided by the universal principles of rigorous science outlined above, various disciplines, fields, and projects have worked hard to design and develop consistent standards, guidelines, and tools to help with reporting all types of experiment. Below, you’ll find some of the key initiatives. Ensure you read the submission guidelines for the specific journal you are submitting to, in order to discover any further journal- or field-specific policies to follow, or initiatives/tools to utilize.

Tip: Keep your paper moving forward by providing the proper paperwork up front

Be sure to check the journal guidelines and provide the necessary documents with your manuscript submission. Collecting the necessary documentation can greatly slow the first round of peer review, or cause delays when you submit your revision.

Randomized Controlled Trials – CONSORT The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) project covers various initiatives intended to prevent the problems of inadequate reporting of randomized controlled trials. The primary initiative is an evidence-based minimum set of recommendations for reporting randomized trials known as the CONSORT Statement .

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses – PRISMA The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses ( PRISMA ) is an evidence-based minimum set of items focusing on the reporting of reviews evaluating randomized trials and other types of research.

Research using Animals – ARRIVE The Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments ( ARRIVE ) guidelines encourage maximizing the information reported in research using animals thereby minimizing unnecessary studies. (Original study and proposal , and updated guidelines , in PLOS Biology .)

Laboratory Protocols Protocols.io has developed a platform specifically for the sharing and updating of laboratory protocols , which are assigned their own DOI and can be linked from methods sections of papers to enhance reproducibility. Contextualize your protocol and improve discovery with an accompanying Lab Protocol article in PLOS ONE .

Consistent reporting of Materials, Design, and Analysis – the MDAR checklist A cross-publisher group of editors and experts have developed, tested, and rolled out a checklist to help establish and harmonize reporting standards in the Life Sciences . The checklist , which is available for use by authors to compile their methods, and editors/reviewers to check methods, establishes a minimum set of requirements in transparent reporting and is adaptable to any discipline within the Life Sciences, by covering a breadth of potentially relevant methodological items and considerations. If you are in the Life Sciences and writing up your methods section, try working through the MDAR checklist and see whether it helps you include all relevant details into your methods, and whether it reminded you of anything you might have missed otherwise.

Summary Writing tips

The main challenge you may find when writing your methods is keeping it readable AND covering all the details needed for reproducibility and replicability. While this is difficult, do not compromise on rigorous standards for credibility!

- Keep in mind future replicability, alongside understanding and readability.

- Follow checklists, and field- and journal-specific guidelines.

- Consider a commitment to rigorous and transparent science a personal responsibility, and not just adhering to journal guidelines.

- Establish whether there are persistent identifiers for any research resources you use that can be specifically cited in your methods section.

- Deposit your laboratory protocols in Protocols.io, establishing a permanent link to them. You can update your protocols later if you improve on them, as can future scientists who follow your protocols.

- Consider visual aids like flow-diagrams, lists, to help with reading other sections of the paper.

- Be specific about all decisions made during the experiments that someone reproducing your work would need to know.

Don’t

- Summarize or abbreviate methods without giving full details in a discoverable supplemental section.

- Presume you will always be able to remember how you performed the experiments, or have access to private or institutional notebooks and resources.

- Attempt to hide constraints or non-optimal decisions you had to make–transparency is the key to ensuring the credibility of your research.

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write an Abstract

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

News alert: UC Berkeley has announced its next university librarian

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Research methods--quantitative, qualitative, and more: overview.

- Quantitative Research

- Qualitative Research

- Data Science Methods (Machine Learning, AI, Big Data)

- Text Mining and Computational Text Analysis

- Evidence Synthesis/Systematic Reviews

- Get Data, Get Help!

About Research Methods

This guide provides an overview of research methods, how to choose and use them, and supports and resources at UC Berkeley.

As Patten and Newhart note in the book Understanding Research Methods , "Research methods are the building blocks of the scientific enterprise. They are the "how" for building systematic knowledge. The accumulation of knowledge through research is by its nature a collective endeavor. Each well-designed study provides evidence that may support, amend, refute, or deepen the understanding of existing knowledge...Decisions are important throughout the practice of research and are designed to help researchers collect evidence that includes the full spectrum of the phenomenon under study, to maintain logical rules, and to mitigate or account for possible sources of bias. In many ways, learning research methods is learning how to see and make these decisions."

The choice of methods varies by discipline, by the kind of phenomenon being studied and the data being used to study it, by the technology available, and more. This guide is an introduction, but if you don't see what you need here, always contact your subject librarian, and/or take a look to see if there's a library research guide that will answer your question.

Suggestions for changes and additions to this guide are welcome!

START HERE: SAGE Research Methods

Without question, the most comprehensive resource available from the library is SAGE Research Methods. HERE IS THE ONLINE GUIDE to this one-stop shopping collection, and some helpful links are below:

- SAGE Research Methods

- Little Green Books (Quantitative Methods)

- Little Blue Books (Qualitative Methods)

- Dictionaries and Encyclopedias

- Case studies of real research projects

- Sample datasets for hands-on practice

- Streaming video--see methods come to life

- Methodspace- -a community for researchers

- SAGE Research Methods Course Mapping

Library Data Services at UC Berkeley

Library Data Services Program and Digital Scholarship Services

The LDSP offers a variety of services and tools ! From this link, check out pages for each of the following topics: discovering data, managing data, collecting data, GIS data, text data mining, publishing data, digital scholarship, open science, and the Research Data Management Program.

Be sure also to check out the visual guide to where to seek assistance on campus with any research question you may have!

Library GIS Services

Other Data Services at Berkeley

D-Lab Supports Berkeley faculty, staff, and graduate students with research in data intensive social science, including a wide range of training and workshop offerings Dryad Dryad is a simple self-service tool for researchers to use in publishing their datasets. It provides tools for the effective publication of and access to research data. Geospatial Innovation Facility (GIF) Provides leadership and training across a broad array of integrated mapping technologies on campu Research Data Management A UC Berkeley guide and consulting service for research data management issues

General Research Methods Resources

Here are some general resources for assistance:

- Assistance from ICPSR (must create an account to access): Getting Help with Data , and Resources for Students

- Wiley Stats Ref for background information on statistics topics

- Survey Documentation and Analysis (SDA) . Program for easy web-based analysis of survey data.

Consultants

- D-Lab/Data Science Discovery Consultants Request help with your research project from peer consultants.

- Research data (RDM) consulting Meet with RDM consultants before designing the data security, storage, and sharing aspects of your qualitative project.

- Statistics Department Consulting Services A service in which advanced graduate students, under faculty supervision, are available to consult during specified hours in the Fall and Spring semesters.

Related Resourcex

- IRB / CPHS Qualitative research projects with human subjects often require that you go through an ethics review.

- OURS (Office of Undergraduate Research and Scholarships) OURS supports undergraduates who want to embark on research projects and assistantships. In particular, check out their "Getting Started in Research" workshops

- Sponsored Projects Sponsored projects works with researchers applying for major external grants.

- Next: Quantitative Research >>

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 11:09 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/researchmethods

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Methods | Definition, Types, Examples

Research methods are specific procedures for collecting and analysing data. Developing your research methods is an integral part of your research design . When planning your methods, there are two key decisions you will make.

First, decide how you will collect data . Your methods depend on what type of data you need to answer your research question :

- Qualitative vs quantitative : Will your data take the form of words or numbers?

- Primary vs secondary : Will you collect original data yourself, or will you use data that have already been collected by someone else?

- Descriptive vs experimental : Will you take measurements of something as it is, or will you perform an experiment?

Second, decide how you will analyse the data .

- For quantitative data, you can use statistical analysis methods to test relationships between variables.

- For qualitative data, you can use methods such as thematic analysis to interpret patterns and meanings in the data.

Table of contents

Methods for collecting data, examples of data collection methods, methods for analysing data, examples of data analysis methods, frequently asked questions about methodology.

Data are the information that you collect for the purposes of answering your research question . The type of data you need depends on the aims of your research.

Qualitative vs quantitative data

Your choice of qualitative or quantitative data collection depends on the type of knowledge you want to develop.

For questions about ideas, experiences and meanings, or to study something that can’t be described numerically, collect qualitative data .

If you want to develop a more mechanistic understanding of a topic, or your research involves hypothesis testing , collect quantitative data .

You can also take a mixed methods approach, where you use both qualitative and quantitative research methods.

Primary vs secondary data

Primary data are any original information that you collect for the purposes of answering your research question (e.g. through surveys , observations and experiments ). Secondary data are information that has already been collected by other researchers (e.g. in a government census or previous scientific studies).

If you are exploring a novel research question, you’ll probably need to collect primary data. But if you want to synthesise existing knowledge, analyse historical trends, or identify patterns on a large scale, secondary data might be a better choice.

Descriptive vs experimental data

In descriptive research , you collect data about your study subject without intervening. The validity of your research will depend on your sampling method .

In experimental research , you systematically intervene in a process and measure the outcome. The validity of your research will depend on your experimental design .

To conduct an experiment, you need to be able to vary your independent variable , precisely measure your dependent variable, and control for confounding variables . If it’s practically and ethically possible, this method is the best choice for answering questions about cause and effect.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Your data analysis methods will depend on the type of data you collect and how you prepare them for analysis.

Data can often be analysed both quantitatively and qualitatively. For example, survey responses could be analysed qualitatively by studying the meanings of responses or quantitatively by studying the frequencies of responses.

Qualitative analysis methods

Qualitative analysis is used to understand words, ideas, and experiences. You can use it to interpret data that were collected:

- From open-ended survey and interview questions, literature reviews, case studies, and other sources that use text rather than numbers.

- Using non-probability sampling methods .

Qualitative analysis tends to be quite flexible and relies on the researcher’s judgement, so you have to reflect carefully on your choices and assumptions.

Quantitative analysis methods

Quantitative analysis uses numbers and statistics to understand frequencies, averages and correlations (in descriptive studies) or cause-and-effect relationships (in experiments).

You can use quantitative analysis to interpret data that were collected either:

- During an experiment.

- Using probability sampling methods .

Because the data are collected and analysed in a statistically valid way, the results of quantitative analysis can be easily standardised and shared among researchers.

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to test a hypothesis by systematically collecting and analysing data, while qualitative methods allow you to explore ideas and experiences in depth.

In mixed methods research , you use both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis methods to answer your research question .

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Methodology refers to the overarching strategy and rationale of your research project . It involves studying the methods used in your field and the theories or principles behind them, in order to develop an approach that matches your objectives.

Methods are the specific tools and procedures you use to collect and analyse data (e.g. experiments, surveys , and statistical tests ).

In shorter scientific papers, where the aim is to report the findings of a specific study, you might simply describe what you did in a methods section .

In a longer or more complex research project, such as a thesis or dissertation , you will probably include a methodology section , where you explain your approach to answering the research questions and cite relevant sources to support your choice of methods.

Is this article helpful?

More interesting articles.

- A Quick Guide to Experimental Design | 5 Steps & Examples

- Between-Subjects Design | Examples, Pros & Cons

- Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

- Cluster Sampling | A Simple Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

- Confounding Variables | Definition, Examples & Controls

- Construct Validity | Definition, Types, & Examples

- Content Analysis | A Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

- Control Groups and Treatment Groups | Uses & Examples

- Controlled Experiments | Methods & Examples of Control

- Correlation vs Causation | Differences, Designs & Examples

- Correlational Research | Guide, Design & Examples

- Critical Discourse Analysis | Definition, Guide & Examples

- Cross-Sectional Study | Definitions, Uses & Examples

- Data Cleaning | A Guide with Examples & Steps

- Data Collection Methods | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

- Descriptive Research Design | Definition, Methods & Examples

- Doing Survey Research | A Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

- Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples

- Explanatory Research | Definition, Guide, & Examples

- Explanatory vs Response Variables | Definitions & Examples

- Exploratory Research | Definition, Guide, & Examples

- External Validity | Types, Threats & Examples

- Extraneous Variables | Examples, Types, Controls

- Face Validity | Guide with Definition & Examples

- How to Do Thematic Analysis | Guide & Examples

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

- Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria | Examples & Definition

- Independent vs Dependent Variables | Definition & Examples

- Inductive Reasoning | Types, Examples, Explanation

- Inductive vs Deductive Research Approach (with Examples)

- Internal Validity | Definition, Threats & Examples

- Internal vs External Validity | Understanding Differences & Examples

- Longitudinal Study | Definition, Approaches & Examples

- Mediator vs Moderator Variables | Differences & Examples

- Mixed Methods Research | Definition, Guide, & Examples

- Multistage Sampling | An Introductory Guide with Examples

- Naturalistic Observation | Definition, Guide & Examples

- Operationalisation | A Guide with Examples, Pros & Cons

- Population vs Sample | Definitions, Differences & Examples

- Primary Research | Definition, Types, & Examples

- Qualitative vs Quantitative Research | Examples & Methods

- Quasi-Experimental Design | Definition, Types & Examples

- Questionnaire Design | Methods, Question Types & Examples

- Random Assignment in Experiments | Introduction & Examples

- Reliability vs Validity in Research | Differences, Types & Examples

- Reproducibility vs Replicability | Difference & Examples

- Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

- Sampling Methods | Types, Techniques, & Examples

- Semi-Structured Interview | Definition, Guide & Examples

- Simple Random Sampling | Definition, Steps & Examples

- Stratified Sampling | A Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

- Structured Interview | Definition, Guide & Examples

- Systematic Review | Definition, Examples & Guide

- Systematic Sampling | A Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

- Textual Analysis | Guide, 3 Approaches & Examples

- The 4 Types of Reliability in Research | Definitions & Examples

- The 4 Types of Validity | Types, Definitions & Examples

- Transcribing an Interview | 5 Steps & Transcription Software

- Triangulation in Research | Guide, Types, Examples

- Types of Interviews in Research | Guide & Examples

- Types of Research Designs Compared | Examples

- Types of Variables in Research | Definitions & Examples

- Unstructured Interview | Definition, Guide & Examples

- What Are Control Variables | Definition & Examples

- What Is a Case-Control Study? | Definition & Examples

- What Is a Cohort Study? | Definition & Examples

- What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples

- What Is a Double-Barrelled Question?

- What Is a Double-Blind Study? | Introduction & Examples

- What Is a Focus Group? | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

- What Is a Likert Scale? | Guide & Examples

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

- What Is a Prospective Cohort Study? | Definition & Examples

- What Is a Retrospective Cohort Study? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples

- What Is an Observational Study? | Guide & Examples

- What Is Concurrent Validity? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Content Validity? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Convenience Sampling? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Convergent Validity? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Criterion Validity? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Deductive Reasoning? | Explanation & Examples

- What Is Discriminant Validity? | Definition & Example

- What Is Ecological Validity? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Ethnography? | Meaning, Guide & Examples

- What Is Non-Probability Sampling? | Types & Examples

- What Is Participant Observation? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

- What Is Predictive Validity? | Examples & Definition

- What Is Probability Sampling? | Types & Examples

- What Is Purposive Sampling? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Qualitative Observation? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

- What Is Quantitative Observation? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition & Methods

- What Is Quota Sampling? | Definition & Examples

- What is Secondary Research? | Definition, Types, & Examples

- What Is Snowball Sampling? | Definition & Examples

- Within-Subjects Design | Explanation, Approaches, Examples

- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

- Research Tips and Tools

Advanced Research Methods

Writing the research paper.

- What Is Research?

- Library Research

- Writing a Research Proposal

Before Writing the Paper

Methods, thesis and hypothesis, clarity, precision and academic expression, format your paper, typical problems, a few suggestions, avoid plagiarism.

- Presenting the Research Paper

Find a topic.

- Try to find a subject that really interests you.

- While you explore the topic, narrow or broaden your target and focus on something that gives the most promising results.

- Don't choose a huge subject if you have to write a 3 page long paper, and broaden your topic sufficiently if you have to submit at least 25 pages.

- Consult your class instructor (and your classmates) about the topic.

Explore the topic.

- Find primary and secondary sources in the library.

- Read and critically analyse them.

- Take notes.

- Compile surveys, collect data, gather materials for quantitative analysis (if these are good methods to investigate the topic more deeply).

- Come up with new ideas about the topic. Try to formulate your ideas in a few sentences.

- Review your notes and other materials and enrich the outline.

- Try to estimate how long the individual parts will be.

- Do others understand what you want to say?

- Do they accept it as new knowledge or relevant and important for a paper?

- Do they agree that your thoughts will result in a successful paper?

- Qualitative: gives answers on questions (how, why, when, who, what, etc.) by investigating an issue

- Quantitative:requires data and the analysis of data as well

- the essence, the point of the research paper in one or two sentences.

- a statement that can be proved or disproved.

- Be specific.

- Avoid ambiguity.

- Use predominantly the active voice, not the passive.

- Deal with one issue in one paragraph.

- Be accurate.

- Double-check your data, references, citations and statements.

Academic Expression

- Don't use familiar style or colloquial/slang expressions.

- Write in full sentences.

- Check the meaning of the words if you don't know exactly what they mean.

- Avoid metaphors.

- Almost the rough content of every paragraph.

- The order of the various topics in your paper.

- On the basis of the outline, start writing a part by planning the content, and then write it down.

- Put a visible mark (which you will later delete) where you need to quote a source, and write in the citation when you finish writing that part or a bigger part.

- Does the text make sense?

- Could you explain what you wanted?

- Did you write good sentences?

- Is there something missing?

- Check the spelling.

- Complete the citations, bring them in standard format.

Use the guidelines that your instructor requires (MLA, Chicago, APA, Turabian, etc.).

- Adjust margins, spacing, paragraph indentation, place of page numbers, etc.

- Standardize the bibliography or footnotes according to the guidelines.

- EndNote and EndNote Basic by UCLA Library Last Updated May 8, 2024 1144 views this year

- Zotero by UCLA Library Last Updated May 15, 2024 816 views this year

(Based on English Composition 2 from Illinois Valley Community College):

- Weak organization

- Poor support and development of ideas

- Weak use of secondary sources

- Excessive errors

- Stylistic weakness

When collecting materials, selecting research topic, and writing the paper:

- Be systematic and organized (e.g. keep your bibliography neat and organized; write your notes in a neat way, so that you can find them later on.

- Use your critical thinking ability when you read.

- Write down your thoughts (so that you can reconstruct them later).

- Stop when you have a really good idea and think about whether you could enlarge it to a whole research paper. If yes, take much longer notes.

- When you write down a quotation or summarize somebody else's thoughts in your notes or in the paper, cite the source (i.e. write down the author, title, publication place, year, page number).

- If you quote or summarize a thought from the internet, cite the internet source.

- Write an outline that is detailed enough to remind you about the content.

- Read your paper for yourself or, preferably, somebody else.

- When you finish writing, check the spelling;

- Use the citation form (MLA, Chicago, or other) that your instructor requires and use it everywhere.

Plagiarism : somebody else's words or ideas presented without citation by an author

- Cite your source every time when you quote a part of somebody's work.

- Cite your source every time when you summarize a thought from somebody's work.

- Cite your source every time when you use a source (quote or summarize) from the Internet.

Consult the Citing Sources research guide for further details.

- << Previous: Writing a Research Proposal

- Next: Presenting the Research Paper >>

- Last Updated: May 16, 2024 10:20 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/research-methods

Organizing Academic Research Papers: 6. The Methodology

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Executive Summary

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tertiary Sources

- What Is Scholarly vs. Popular?

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Annotated Bibliography

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- How to Manage Group Projects

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Essays

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Acknowledgements

The methods section of a research paper provides the information by which a study’s validity is judged. The method section answers two main questions: 1) How was the data collected or generated? 2) How was it analyzed? The writing should be direct and precise and written in the past tense.

Importance of a Good Methodology Section

You must explain how you obtained and analyzed your results for the following reasons:

- Readers need to know how the data was obtained because the method you choose affects the results and, by extension, how you likely interpreted those results.

- Methodology is crucial for any branch of scholarship because an unreliable method produces unreliable results and it misappropriates interpretations of findings .

- In most cases, there are a variety of different methods you can choose to investigate a research problem. Your methodology section of your paper should make clear the reasons why you chose a particular method or procedure .

- The reader wants to know that the data was collected or generated in a way that is consistent with accepted practice in the field of study. For example, if you are using a questionnaire, readers need to know that it offered your respondents a reasonable range of answers to choose from.

- The research method must be appropriate to the objectives of the study . For example, be sure you have a large enough sample size to be able to generalize and make recommendations based upon the findings.

- The methodology should discuss the problems that were anticipated and the steps you took to prevent them from occurring . For any problems that did arise, you must describe the ways in which their impact was minimized or why these problems do not affect the findings in any way that impacts your interpretation of the data.

- Often in social science research, it is useful for other researchers to adapt or replicate your methodology. Therefore, it is important to always provide sufficient information to allow others to use or replicate the study . This information is particularly important when a new method had been developed or an innovative use of an existing method has been utilized.

Bem, Daryl J. Writing the Empirical Journal Article . Psychology Writing Center. University of Washington; Lunenburg, Frederick C. Writing a Successful Thesis or Dissertation: Tips and Strategies for Students in the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2008.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Groups of Research Methods

There are two main groups of research methods in the social sciences:

- The empirical-analytical group approaches the study of social sciences in a similar manner that researchers study the natural sciences. This type of research focuses on objective knowledge, research questions that can be answered yes or no, and operational definitions of variables to be measured. The empirical-analytical group employs deductive reasoning that uses existing theory as a foundation for hypotheses that need to be tested. This approach is focused on explanation .

- The interpretative group is focused on understanding phenomenon in a comprehensive, holistic way . This research method allows you to recognize your connection to the subject under study. Because the interpretative group focuses more on subjective knowledge, it requires careful interpretation of variables.

II. Content

An effectively written methodology section should:

- Introduce the overall methodological approach for investigating your research problem . Is your study qualitative or quantitative or a combination of both (mixed method)? Are you going to take a special approach, such as action research, or a more neutral stance?

- Indicate how the approach fits the overall research design . Your methods should have a clear connection with your research problem. In other words, make sure that your methods will actually address the problem. One of the most common deficiencies found in research papers is that the proposed methodology is unsuited to achieving the stated objective of your paper.

- Describe the specific methods of data collection you are going to use , such as, surveys, interviews, questionnaires, observation, archival research. If you are analyzing existing data, such as a data set or archival documents, describe how it was originally created or gathered and by whom.

- Explain how you intend to analyze your results . Will you use statistical analysis? Will you use specific theoretical perspectives to help you analyze a text or explain observed behaviors?

- Provide background and rationale for methodologies that are unfamiliar for your readers . Very often in the social sciences, research problems and the methods for investigating them require more explanation/rationale than widely accepted rules governing the natural and physical sciences. Be clear and concise in your explanation.

- Provide a rationale for subject selection and sampling procedure . For instance, if you propose to conduct interviews, how do you intend to select the sample population? If you are analyzing texts, which texts have you chosen, and why? If you are using statistics, why is this set of statisics being used? If other data sources exist, explain why the data you chose is most appropriate.

- Address potential limitations . Are there any practical limitations that could affect your data collection? How will you attempt to control for potential confounding variables and errors? If your methodology may lead to problems you can anticipate, state this openly and show why pursuing this methodology outweighs the risk of these problems cropping up.

NOTE : Once you have written all of the elements of the methods section, subsequent revisions should focus on how to present those elements as clearly and as logically as possibly. The description of how you prepared to study the research problem, how you gathered the data, and the protocol for analyzing the data should be organized chronologically. For clarity, when a large amount of detail must be presented, information should be presented in sub-sections according to topic.

III. Problems to Avoid

Irrelevant Detail The methodology section of your paper should be thorough but to the point. Don’t provide any background information that doesn’t directly help the reader to understand why a particular method was chosen, how the data was gathered or obtained, and how it was analyzed. Unnecessary Explanation of Basic Procedures Remember that you are not writing a how-to guide about a particular method. You should make the assumption that readers possess a basic understanding of how to investigate the research problem on their own and, therefore, you do not have to go into great detail about specific methodological procedures. The focus should be on how you applied a method , not on the mechanics of doing a method. NOTE: An exception to this rule is if you select an unconventional approach to doing the method; if this is the case, be sure to explain why this approach was chosen and how it enhances the overall research process. Problem Blindness It is almost a given that you will encounter problems when collecting or generating your data. Do not ignore these problems or pretend they did not occur. Often, documenting how you overcame obstacles can form an interesting part of the methodology. It demonstrates to the reader that you can provide a cogent rationale for the decisions you made to minimize the impact of any problems that arose. Literature Review Just as the literature review section of your paper provides an overview of sources you have examined while researching a particular topic, the methodology section should cite any sources that informed your choice and application of a particular method [i.e., the choice of a survey should include any citations to the works you used to help construct the survey].

It’s More than Sources of Information! A description of a research study's method should not be confused with a description of the sources of information. Such a list of sources is useful in itself, especially if it is accompanied by an explanation about the selection and use of the sources. The description of the project's methodology complements a list of sources in that it sets forth the organization and interpretation of information emanating from those sources.

Azevedo, L.F. et al. How to Write a Scientific Paper: Writing the Methods Section. Revista Portuguesa de Pneumologia 17 (2011): 232-238; Butin, Dan W. The Education Dissertation A Guide for Practitioner Scholars . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, 2010; Carter, Susan. Structuring Your Research Thesis . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012; Lunenburg, Frederick C. Writing a Successful Thesis or Dissertation: Tips and Strategies for Students in the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2008. Methods Section . The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Writing the Experimental Report: Methods, Results, and Discussion . The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Methods and Materials . The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College.

Writing Tip

Statistical Designs and Tests? Do Not Fear Them!

Don't avoid using a quantitative approach to analyzing your research problem just because you fear the idea of applying statistical designs and tests. A qualitative approach, such as conducting interviews or content analysis of archival texts, can yield exciting new insights about a research problem, but it should not be undertaken simply because you have a disdain for running a simple regression. A well designed quantitative research study can often be accomplished in very clear and direct ways, whereas, a similar study of a qualitative nature usually requires considerable time to analyze large volumes of data and a tremendous burden to create new paths for analysis where previously no path associated with your research problem had existed.

Another Writing Tip

Knowing the Relationship Between Theories and Methods

There can be multiple meaning associated with the term "theories" and the term "methods" in social sciences research. A helpful way to delineate between them is to understand "theories" as representing different ways of characterizing the social world when you research it and "methods" as representing different ways of generating and analyzing data about that social world. Framed in this way, all empirical social sciences research involves theories and methods, whether they are stated explicitly or not. However, while theories and methods are often related, it is important that, as a researcher, you deliberately separate them in order to avoid your theories playing a disproportionate role in shaping what outcomes your chosen methods produce.

Introspectively engage in an ongoing dialectic between theories and methods to help enable you to use the outcomes from your methods to interrogate and develop new theories, or ways of framing conceptually the research problem. This is how scholarship grows and branches out into new intellectual territory.

Reynolds, R. Larry. Ways of Knowing. Alternative Microeconomics. Part 1, Chapter 3. Boise State University; The Theory-Method Relationship . S-Cool Revision. United Kingdom.

- << Previous: What Is Scholarly vs. Popular?

- Next: Qualitative Methods >>

- Last Updated: Jul 18, 2023 11:58 AM

- URL: https://library.sacredheart.edu/c.php?g=29803

- QuickSearch

- Library Catalog

- Databases A-Z

- Publication Finder

- Course Reserves

- Citation Linker

- Digital Commons

- Our Website

Research Support

- Ask a Librarian

- Appointments

- Interlibrary Loan (ILL)

- Research Guides

- Databases by Subject

- Citation Help

Using the Library

- Reserve a Group Study Room

- Renew Books

- Honors Study Rooms

- Off-Campus Access

- Library Policies

- Library Technology

User Information

- Grad Students

- Online Students

- COVID-19 Updates

- Staff Directory

- News & Announcements

- Library Newsletter

My Accounts

- Interlibrary Loan

- Staff Site Login

FIND US ON

- How it works

Published by Nicolas at March 21st, 2024 , Revised On March 12, 2024

The Ultimate Guide To Research Methodology

Research methodology is a crucial aspect of any investigative process, serving as the blueprint for the entire research journey. If you are stuck in the methodology section of your research paper , then this blog will guide you on what is a research methodology, its types and how to successfully conduct one.

Table of Contents

What Is Research Methodology?

Research methodology can be defined as the systematic framework that guides researchers in designing, conducting, and analyzing their investigations. It encompasses a structured set of processes, techniques, and tools employed to gather and interpret data, ensuring the reliability and validity of the research findings.

Research methodology is not confined to a singular approach; rather, it encapsulates a diverse range of methods tailored to the specific requirements of the research objectives.

Here is why Research methodology is important in academic and professional settings.

Facilitating Rigorous Inquiry

Research methodology forms the backbone of rigorous inquiry. It provides a structured approach that aids researchers in formulating precise thesis statements , selecting appropriate methodologies, and executing systematic investigations. This, in turn, enhances the quality and credibility of the research outcomes.

Ensuring Reproducibility And Reliability

In both academic and professional contexts, the ability to reproduce research outcomes is paramount. A well-defined research methodology establishes clear procedures, making it possible for others to replicate the study. This not only validates the findings but also contributes to the cumulative nature of knowledge.

Guiding Decision-Making Processes

In professional settings, decisions often hinge on reliable data and insights. Research methodology equips professionals with the tools to gather pertinent information, analyze it rigorously, and derive meaningful conclusions.

This informed decision-making is instrumental in achieving organizational goals and staying ahead in competitive environments.

Contributing To Academic Excellence

For academic researchers, adherence to robust research methodology is a hallmark of excellence. Institutions value research that adheres to high standards of methodology, fostering a culture of academic rigour and intellectual integrity. Furthermore, it prepares students with critical skills applicable beyond academia.

Enhancing Problem-Solving Abilities

Research methodology instills a problem-solving mindset by encouraging researchers to approach challenges systematically. It equips individuals with the skills to dissect complex issues, formulate hypotheses , and devise effective strategies for investigation.

Understanding Research Methodology

In the pursuit of knowledge and discovery, understanding the fundamentals of research methodology is paramount.

Basics Of Research

Research, in its essence, is a systematic and organized process of inquiry aimed at expanding our understanding of a particular subject or phenomenon. It involves the exploration of existing knowledge, the formulation of hypotheses, and the collection and analysis of data to draw meaningful conclusions.

Research is a dynamic and iterative process that contributes to the continuous evolution of knowledge in various disciplines.

Types of Research

Research takes on various forms, each tailored to the nature of the inquiry. Broadly classified, research can be categorized into two main types:

- Quantitative Research: This type involves the collection and analysis of numerical data to identify patterns, relationships, and statistical significance. It is particularly useful for testing hypotheses and making predictions.

- Qualitative Research: Qualitative research focuses on understanding the depth and details of a phenomenon through non-numerical data. It often involves methods such as interviews, focus groups, and content analysis, providing rich insights into complex issues.

Components Of Research Methodology

To conduct effective research, one must go through the different components of research methodology. These components form the scaffolding that supports the entire research process, ensuring its coherence and validity.

Research Design

Research design serves as the blueprint for the entire research project. It outlines the overall structure and strategy for conducting the study. The three primary types of research design are:

- Exploratory Research: Aimed at gaining insights and familiarity with the topic, often used in the early stages of research.

- Descriptive Research: Involves portraying an accurate profile of a situation or phenomenon, answering the ‘what,’ ‘who,’ ‘where,’ and ‘when’ questions.

- Explanatory Research: Seeks to identify the causes and effects of a phenomenon, explaining the ‘why’ and ‘how.’

Data Collection Methods

Choosing the right data collection methods is crucial for obtaining reliable and relevant information. Common methods include:

- Surveys and Questionnaires: Employed to gather information from a large number of respondents through standardized questions.

- Interviews: In-depth conversations with participants, offering qualitative insights.

- Observation: Systematic watching and recording of behaviour, events, or processes in their natural setting.

Data Analysis Techniques

Once data is collected, analysis becomes imperative to derive meaningful conclusions. Different methodologies exist for quantitative and qualitative data:

- Quantitative Data Analysis: Involves statistical techniques such as descriptive statistics, inferential statistics, and regression analysis to interpret numerical data.

- Qualitative Data Analysis: Methods like content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory are employed to extract patterns, themes, and meanings from non-numerical data.

The research paper we write have:

- Precision and Clarity

- Zero Plagiarism

- High-level Encryption

- Authentic Sources

Choosing a Research Method

Selecting an appropriate research method is a critical decision in the research process. It determines the approach, tools, and techniques that will be used to answer the research questions.

Quantitative Research Methods

Quantitative research involves the collection and analysis of numerical data, providing a structured and objective approach to understanding and explaining phenomena.

Experimental Research

Experimental research involves manipulating variables to observe the effect on another variable under controlled conditions. It aims to establish cause-and-effect relationships.

Key Characteristics:

- Controlled Environment: Experiments are conducted in a controlled setting to minimize external influences.

- Random Assignment: Participants are randomly assigned to different experimental conditions.

- Quantitative Data: Data collected is numerical, allowing for statistical analysis.

Applications: Commonly used in scientific studies and psychology to test hypotheses and identify causal relationships.

Survey Research

Survey research gathers information from a sample of individuals through standardized questionnaires or interviews. It aims to collect data on opinions, attitudes, and behaviours.

- Structured Instruments: Surveys use structured instruments, such as questionnaires, to collect data.

- Large Sample Size: Surveys often target a large and diverse group of participants.

- Quantitative Data Analysis: Responses are quantified for statistical analysis.

Applications: Widely employed in social sciences, marketing, and public opinion research to understand trends and preferences.

Descriptive Research

Descriptive research seeks to portray an accurate profile of a situation or phenomenon. It focuses on answering the ‘what,’ ‘who,’ ‘where,’ and ‘when’ questions.

- Observation and Data Collection: This involves observing and documenting without manipulating variables.

- Objective Description: Aim to provide an unbiased and factual account of the subject.

- Quantitative or Qualitative Data: T his can include both types of data, depending on the research focus.

Applications: Useful in situations where researchers want to understand and describe a phenomenon without altering it, common in social sciences and education.

Qualitative Research Methods

Qualitative research emphasizes exploring and understanding the depth and complexity of phenomena through non-numerical data.

A case study is an in-depth exploration of a particular person, group, event, or situation. It involves detailed, context-rich analysis.

- Rich Data Collection: Uses various data sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents.

- Contextual Understanding: Aims to understand the context and unique characteristics of the case.

- Holistic Approach: Examines the case in its entirety.

Applications: Common in social sciences, psychology, and business to investigate complex and specific instances.

Ethnography

Ethnography involves immersing the researcher in the culture or community being studied to gain a deep understanding of their behaviours, beliefs, and practices.

- Participant Observation: Researchers actively participate in the community or setting.

- Holistic Perspective: Focuses on the interconnectedness of cultural elements.

- Qualitative Data: In-depth narratives and descriptions are central to ethnographic studies.

Applications: Widely used in anthropology, sociology, and cultural studies to explore and document cultural practices.

Grounded Theory

Grounded theory aims to develop theories grounded in the data itself. It involves systematic data collection and analysis to construct theories from the ground up.

- Constant Comparison: Data is continually compared and analyzed during the research process.

- Inductive Reasoning: Theories emerge from the data rather than being imposed on it.

- Iterative Process: The research design evolves as the study progresses.

Applications: Commonly applied in sociology, nursing, and management studies to generate theories from empirical data.

Research design is the structural framework that outlines the systematic process and plan for conducting a study. It serves as the blueprint, guiding researchers on how to collect, analyze, and interpret data.

Exploratory, Descriptive, And Explanatory Designs

Exploratory design.

Exploratory research design is employed when a researcher aims to explore a relatively unknown subject or gain insights into a complex phenomenon.

- Flexibility: Allows for flexibility in data collection and analysis.

- Open-Ended Questions: Uses open-ended questions to gather a broad range of information.

- Preliminary Nature: Often used in the initial stages of research to formulate hypotheses.

Applications: Valuable in the early stages of investigation, especially when the researcher seeks a deeper understanding of a subject before formalizing research questions.

Descriptive Design

Descriptive research design focuses on portraying an accurate profile of a situation, group, or phenomenon.

- Structured Data Collection: Involves systematic and structured data collection methods.

- Objective Presentation: Aims to provide an unbiased and factual account of the subject.

- Quantitative or Qualitative Data: Can incorporate both types of data, depending on the research objectives.

Applications: Widely used in social sciences, marketing, and educational research to provide detailed and objective descriptions.

Explanatory Design

Explanatory research design aims to identify the causes and effects of a phenomenon, explaining the ‘why’ and ‘how’ behind observed relationships.

- Causal Relationships: Seeks to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Controlled Variables : Often involves controlling certain variables to isolate causal factors.

- Quantitative Analysis: Primarily relies on quantitative data analysis techniques.

Applications: Commonly employed in scientific studies and social sciences to delve into the underlying reasons behind observed patterns.

Cross-Sectional Vs. Longitudinal Designs

Cross-sectional design.

Cross-sectional designs collect data from participants at a single point in time.

- Snapshot View: Provides a snapshot of a population at a specific moment.

- Efficiency: More efficient in terms of time and resources.

- Limited Temporal Insights: Offers limited insights into changes over time.

Applications: Suitable for studying characteristics or behaviours that are stable or not expected to change rapidly.

Longitudinal Design

Longitudinal designs involve the collection of data from the same participants over an extended period.

- Temporal Sequence: Allows for the examination of changes over time.

- Causality Assessment: Facilitates the assessment of cause-and-effect relationships.

- Resource-Intensive: Requires more time and resources compared to cross-sectional designs.

Applications: Ideal for studying developmental processes, trends, or the impact of interventions over time.

Experimental Vs Non-experimental Designs

Experimental design.

Experimental designs involve manipulating variables under controlled conditions to observe the effect on another variable.

- Causality Inference: Enables the inference of cause-and-effect relationships.

- Quantitative Data: Primarily involves the collection and analysis of numerical data.

Applications: Commonly used in scientific studies, psychology, and medical research to establish causal relationships.

Non-Experimental Design

Non-experimental designs observe and describe phenomena without manipulating variables.

- Natural Settings: Data is often collected in natural settings without intervention.

- Descriptive or Correlational: Focuses on describing relationships or correlations between variables.

- Quantitative or Qualitative Data: This can involve either type of data, depending on the research approach.

Applications: Suitable for studying complex phenomena in real-world settings where manipulation may not be ethical or feasible.

Effective data collection is fundamental to the success of any research endeavour.

Designing Effective Surveys

Objective Design:

- Clearly define the research objectives to guide the survey design.

- Craft questions that align with the study’s goals and avoid ambiguity.

Structured Format:

- Use a structured format with standardized questions for consistency.

- Include a mix of closed-ended and open-ended questions for detailed insights.

Pilot Testing:

- Conduct pilot tests to identify and rectify potential issues with survey design.

- Ensure clarity, relevance, and appropriateness of questions.

Sampling Strategy:

- Develop a robust sampling strategy to ensure a representative participant group.

- Consider random sampling or stratified sampling based on the research goals.

Conducting Interviews

Establishing Rapport:

- Build rapport with participants to create a comfortable and open environment.

- Clearly communicate the purpose of the interview and the value of participants’ input.

Open-Ended Questions:

- Frame open-ended questions to encourage detailed responses.

- Allow participants to express their thoughts and perspectives freely.

Active Listening:

- Practice active listening to understand areas and gather rich data.

- Avoid interrupting and maintain a non-judgmental stance during the interview.

Ethical Considerations:

- Obtain informed consent and assure participants of confidentiality.

- Be transparent about the study’s purpose and potential implications.

Observation

1. participant observation.

Immersive Participation:

- Actively immerse yourself in the setting or group being observed.

- Develop a deep understanding of behaviours, interactions, and context.

Field Notes:

- Maintain detailed and reflective field notes during observations.

- Document observed patterns, unexpected events, and participant reactions.

Ethical Awareness:

- Be conscious of ethical considerations, ensuring respect for participants.

- Balance the role of observer and participant to minimize bias.

2. Non-participant Observation

Objective Observation:

- Maintain a more detached and objective stance during non-participant observation.

- Focus on recording behaviours, events, and patterns without direct involvement.

Data Reliability:

- Enhance the reliability of data by reducing observer bias.

- Develop clear observation protocols and guidelines.

Contextual Understanding:

- Strive for a thorough understanding of the observed context.

- Consider combining non-participant observation with other methods for triangulation.

Archival Research

1. using existing data.

Identifying Relevant Archives:

- Locate and access archives relevant to the research topic.

- Collaborate with institutions or repositories holding valuable data.

Data Verification:

- Verify the accuracy and reliability of archived data.

- Cross-reference with other sources to ensure data integrity.

Ethical Use:

- Adhere to ethical guidelines when using existing data.

- Respect copyright and intellectual property rights.

2. Challenges and Considerations

Incomplete or Inaccurate Archives:

- Address the possibility of incomplete or inaccurate archival records.

- Acknowledge limitations and uncertainties in the data.

Temporal Bias:

- Recognize potential temporal biases in archived data.

- Consider the historical context and changes that may impact interpretation.

Access Limitations:

- Address potential limitations in accessing certain archives.

- Seek alternative sources or collaborate with institutions to overcome barriers.

Common Challenges in Research Methodology

Conducting research is a complex and dynamic process, often accompanied by a myriad of challenges. Addressing these challenges is crucial to ensure the reliability and validity of research findings.

Sampling Issues

Sampling bias:.

- The presence of sampling bias can lead to an unrepresentative sample, affecting the generalizability of findings.

- Employ random sampling methods and ensure the inclusion of diverse participants to reduce bias.

Sample Size Determination:

- Determining an appropriate sample size is a delicate balance. Too small a sample may lack statistical power, while an excessively large sample may strain resources.

- Conduct a power analysis to determine the optimal sample size based on the research objectives and expected effect size.

Data Quality And Validity

Measurement error:.

- Inaccuracies in measurement tools or data collection methods can introduce measurement errors, impacting the validity of results.

- Pilot test instruments, calibrate equipment, and use standardized measures to enhance the reliability of data.

Construct Validity:

- Ensuring that the chosen measures accurately capture the intended constructs is a persistent challenge.

- Use established measurement instruments and employ multiple measures to assess the same construct for triangulation.

Time And Resource Constraints

Timeline pressures:.

- Limited timeframes can compromise the depth and thoroughness of the research process.

- Develop a realistic timeline, prioritize tasks, and communicate expectations with stakeholders to manage time constraints effectively.

Resource Availability:

- Inadequate resources, whether financial or human, can impede the execution of research activities.

- Seek external funding, collaborate with other researchers, and explore alternative methods that require fewer resources.

Managing Bias in Research

Selection bias:.

- Selecting participants in a way that systematically skews the sample can introduce selection bias.

- Employ randomization techniques, use stratified sampling, and transparently report participant recruitment methods.

Confirmation Bias:

- Researchers may unintentionally favour information that confirms their preconceived beliefs or hypotheses.

- Adopt a systematic and open-minded approach, use blinded study designs, and engage in peer review to mitigate confirmation bias.

Tips On How To Write A Research Methodology

Conducting successful research relies not only on the application of sound methodologies but also on strategic planning and effective collaboration. Here are some tips to enhance the success of your research methodology:

Tip 1. Clear Research Objectives

Well-defined research objectives guide the entire research process. Clearly articulate the purpose of your study, outlining specific research questions or hypotheses.

Tip 2. Comprehensive Literature Review

A thorough literature review provides a foundation for understanding existing knowledge and identifying gaps. Invest time in reviewing relevant literature to inform your research design and methodology.

Tip 3. Detailed Research Plan

A detailed plan serves as a roadmap, ensuring all aspects of the research are systematically addressed. Develop a detailed research plan outlining timelines, milestones, and tasks.

Tip 4. Ethical Considerations

Ethical practices are fundamental to maintaining the integrity of research. Address ethical considerations early, obtain necessary approvals, and ensure participant rights are safeguarded.

Tip 5. Stay Updated On Methodologies

Research methodologies evolve, and staying updated is essential for employing the most effective techniques. Engage in continuous learning by attending workshops, conferences, and reading recent publications.

Tip 6. Adaptability In Methods

Unforeseen challenges may arise during research, necessitating adaptability in methods. Be flexible and willing to modify your approach when needed, ensuring the integrity of the study.

Tip 7. Iterative Approach

Research is often an iterative process, and refining methods based on ongoing findings enhance the study’s robustness. Regularly review and refine your research design and methods as the study progresses.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the research methodology.

Research methodology is the systematic process of planning, executing, and evaluating scientific investigation. It encompasses the techniques, tools, and procedures used to collect, analyze, and interpret data, ensuring the reliability and validity of research findings.

What are the methodologies in research?

Research methodologies include qualitative and quantitative approaches. Qualitative methods involve in-depth exploration of non-numerical data, while quantitative methods use statistical analysis to examine numerical data. Mixed methods combine both approaches for a comprehensive understanding of research questions.

How to write research methodology?

To write a research methodology, clearly outline the study’s design, data collection, and analysis procedures. Specify research tools, participants, and sampling methods. Justify choices and discuss limitations. Ensure clarity, coherence, and alignment with research objectives for a robust methodology section.

How to write the methodology section of a research paper?

In the methodology section of a research paper, describe the study’s design, data collection, and analysis methods. Detail procedures, tools, participants, and sampling. Justify choices, address ethical considerations, and explain how the methodology aligns with research objectives, ensuring clarity and rigour.

What is mixed research methodology?

Mixed research methodology combines both qualitative and quantitative research approaches within a single study. This approach aims to enhance the details and depth of research findings by providing a more comprehensive understanding of the research problem or question.

You May Also Like

Discover Canadian doctoral dissertation format: structure, formatting, and word limits. Check your university guidelines.

What is a manuscript? A manuscript is a written or typed document, often the original draft of a book or article, before publication, undergoing editing and revisions.

Academic integrity: a commitment to honesty and ethical conduct in learning. Upholding originality and proper citation are its cornerstones.

Ready to place an order?

USEFUL LINKS

Learning resources, company details.

- How It Works

Automated page speed optimizations for fast site performance

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Paper

Definition:

Research Paper is a written document that presents the author’s original research, analysis, and interpretation of a specific topic or issue.

It is typically based on Empirical Evidence, and may involve qualitative or quantitative research methods, or a combination of both. The purpose of a research paper is to contribute new knowledge or insights to a particular field of study, and to demonstrate the author’s understanding of the existing literature and theories related to the topic.

Structure of Research Paper

The structure of a research paper typically follows a standard format, consisting of several sections that convey specific information about the research study. The following is a detailed explanation of the structure of a research paper:

The title page contains the title of the paper, the name(s) of the author(s), and the affiliation(s) of the author(s). It also includes the date of submission and possibly, the name of the journal or conference where the paper is to be published.

The abstract is a brief summary of the research paper, typically ranging from 100 to 250 words. It should include the research question, the methods used, the key findings, and the implications of the results. The abstract should be written in a concise and clear manner to allow readers to quickly grasp the essence of the research.

Introduction

The introduction section of a research paper provides background information about the research problem, the research question, and the research objectives. It also outlines the significance of the research, the research gap that it aims to fill, and the approach taken to address the research question. Finally, the introduction section ends with a clear statement of the research hypothesis or research question.

Literature Review

The literature review section of a research paper provides an overview of the existing literature on the topic of study. It includes a critical analysis and synthesis of the literature, highlighting the key concepts, themes, and debates. The literature review should also demonstrate the research gap and how the current study seeks to address it.

The methods section of a research paper describes the research design, the sample selection, the data collection and analysis procedures, and the statistical methods used to analyze the data. This section should provide sufficient detail for other researchers to replicate the study.

The results section presents the findings of the research, using tables, graphs, and figures to illustrate the data. The findings should be presented in a clear and concise manner, with reference to the research question and hypothesis.

The discussion section of a research paper interprets the findings and discusses their implications for the research question, the literature review, and the field of study. It should also address the limitations of the study and suggest future research directions.

The conclusion section summarizes the main findings of the study, restates the research question and hypothesis, and provides a final reflection on the significance of the research.

The references section provides a list of all the sources cited in the paper, following a specific citation style such as APA, MLA or Chicago.

How to Write Research Paper

You can write Research Paper by the following guide:

- Choose a Topic: The first step is to select a topic that interests you and is relevant to your field of study. Brainstorm ideas and narrow down to a research question that is specific and researchable.

- Conduct a Literature Review: The literature review helps you identify the gap in the existing research and provides a basis for your research question. It also helps you to develop a theoretical framework and research hypothesis.

- Develop a Thesis Statement : The thesis statement is the main argument of your research paper. It should be clear, concise and specific to your research question.

- Plan your Research: Develop a research plan that outlines the methods, data sources, and data analysis procedures. This will help you to collect and analyze data effectively.

- Collect and Analyze Data: Collect data using various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments. Analyze data using statistical tools or other qualitative methods.

- Organize your Paper : Organize your paper into sections such as Introduction, Literature Review, Methods, Results, Discussion, and Conclusion. Ensure that each section is coherent and follows a logical flow.

- Write your Paper : Start by writing the introduction, followed by the literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. Ensure that your writing is clear, concise, and follows the required formatting and citation styles.