CPC Module 2

Post_title;>-->.

There are 9 questions in this CPC module 2 case study. Read the scenario carefully and ensure you understand it fully. You need to score at least 7 out of 9 to pass. Good luck!

Sign up to keep track of your progress

Tests Taken

Average Score

Your Progress

You're doing well! Carry on practising to make sure you're prepared for your test. You'll soon see your scores improve!

Do you wish to proceed?

1315 votes - average 4.8 out of 5

CPC Module 2 Quick View

Click the question box to reveal the correct answer. You can print the CPC Module 2 questions and answers by clicking the printer icon below.

Privacy Overview

- Study Materials

- Multiple- choice questions

- Hazard Perception

Module 2 Case Studies

14 sections accurate to the real test, 20 topics covering lorry driving, and hazard perception training, with case studies. All questions cover the accurate questions for the test.

our SCHOOL Goals 2019

Your career path begins here, tried and tested.

Our training materials are proven to work

Support From A Teacher

Get feedback, support and mentoring from a qualified teacher

99% Pass Rate

For every 100 students that train with us 99 pass.

Unlimited Training

Train until you pass your exams. Pass in 30 days or 1 day

- Fast Track Training International Ltd, 82-82 Radford Road, Hyson Green, Nottingham, United Kingdom, NG7 5FU

- [email protected]

- 01158376502

Quick Links

- Registration

Useful Links

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

© Fast Track Training International Ltd

Copyright © 2023. All rights reserved.

Cookies on GOV.UK

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We’d like to set additional cookies to understand how you use GOV.UK, remember your settings and improve government services.

We also use cookies set by other sites to help us deliver content from their services.

You have accepted additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

You have rejected additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

- Driving and transport

- HGV, bus and coach drivers

Become a qualified heavy goods vehicle (HGV) or bus driver

Returning to be an hgv or bus driver.

If you previously qualified, you do not have to do the full qualification process again to bring your Driver Certificate of Professional Competence ( CPC ) up to date.

Check and renew your licence

If you’re not sure whether your licence is still valid, you can check what vehicles you’re allowed to drive .

You need to renew your licence if it’s expired .

Bring your Driver CPC up to date

What you need to do depends on when you originally got your heavy goods vehicle ( HGV ) or bus licence.

Some employers offer help with the cost of training.

If you got an HGV licence before 10 September 2009 or a bus licence before 10 September 2008

You can either:

- complete 35 hours of Driver CPC training by finding and taking training courses

- take and pass the Driver CPC part 2 (case studies) and the Driver CPC part 4 (practical demonstration) tests

If you’ve already taken parts 2 and 4 of the Driver CPC tests, you cannot take them again. You must take 35 hours of training instead.

If you got an HGV licence on or after 10 September 2009 or a bus licence on or after 10 September 2008

You need to complete 35 hours of Driver CPC training by finding and taking training courses .

Any training you’ve done in the last 5 years counts towards the total. The training counts for 5 years from the date you took the course.

After you’ve completed your training or tests

Your new Driver CPC card will be sent to the address on your driving licence when you’ve completed your training or tests.

Check what you need to do once you’ve requalified .

Related content

Is this page useful.

- Yes this page is useful

- No this page is not useful

Help us improve GOV.UK

Don’t include personal or financial information like your National Insurance number or credit card details.

To help us improve GOV.UK, we’d like to know more about your visit today. Please fill in this survey .

Get A Quote

RENEW YOUR CPC - LIMITED COURSES AVAILABLE BOOK NOW RENEW YOUR CPC LIMITED COURSES AVAILABLE BOOK NOW

LGV Training News

The Driver CPC Module 2

- 18 Nov, 2013

- charlotte_mcghie

- Latest News

The Driver CPC Initial Qualification consists of two parts; Module 2 and Module 4. Module 2 is the ‘Case Study’ or theory test part of the Driver CPC Initial Qualification.

Conducted at the theory test centre, the Module 2 test generally takes about 30 minutes, although you have 90 minutes available in which to complete the test. It is a computer-based exercise with questions covering 7 different subject areas, all based on real-life situations which you may encounter as a professional HGV driver. It aims to check that you’re able to put your knowledge into practice.

Each of the 7 subject areas contains 6-8 questions, with a possible maximum score of 50 marks.

You must pass the driver cpc module 2 before you take module 4. In other words, the theory test must be passed before the practical part. Often, we organise the Module 2 test to occur after a candidate has taken their HGV training course, although you can do it alongside your Hazard Perception and Multiple Choice theory tests if you’re up to it!

To apply for the Driver CPC (module 2) theory test you must have a valid driving licence with provisional entitlement for the category in which you wish to do your test. Your Training Advisor will let you know when you’re ready.

I need extra help!

DSA provide a number of facilities for candidates with special needs, including:

English Voiceover – You can request an English voiceover if you feel that would help.

Extra time – If you have dyslexia or other reading difficulty you can request to have up to double time for Module 2. If you request to have more than standard time you will need to send in evidence of your reading difficulty to the theory test booking customer services.

How can I revise for the CPC Module 2?

The LGV Training Company provides totally flexible online revision material for the CPC Module 2.

Revise anytime, anywhere, on a PC, laptop, tablet or even on your mobile!

To find out more about the Driver CPC Initial Qualfication Module 2, please call us on 0800 0744 007.

Recent Articles

Understanding your lgv/hgv licence.

- 03 Apr, 2024

- LGV & HGV Trainer

- HGV Training

What is The Driver CPC Card?

- 12 Mar, 2024

How to Get Your CPC Card: A Guide for Every Aspiring Professional Driver

- 08 Feb, 2024

Call Free 0800 0744 007 Get A Quote

The Complete LGV & PCV

Cpc case study test.

Designed for iOS and for Android – The Complete LGV & PCV Driver CPC Case Study Test Module 2 UK is the most comprehensive and user friendly package for candidates for the CPC Module 2 test. Designed for phones and tablets.

Covers the entire DVSA syllabus

Gain access to the largest collection of professionally written CPC questions that cover the entire DVSA syllabus. Includes interactive practice mode, video tutorials and the complete searchable Highway code – prepare to pass!

Created for all iOS and Android devices

The best tool available for the iPhone, iPad, iPad Mini and all Android phones and tablets to prepare for the LGV & PCV Driver CPC Case Study Test Module 2. Use the content and approach that MILLIONS of users have practiced with to pass.

The best study aid available

Ideal for self-study or for trainers to use with their students. Study whenever and wherever. Internet connection required only to gain access to video and voiceovers only – WiFi connection recommended.

The Complete LGV & PCV Driver CPC Case Study Test Module 2 offers a simple and unique learning experience “study – practice – exam simulation” to ensure that you understand the concepts, pass first time and enjoy safe motoring.

Built on Learn2® technology – the approach used by millions.

Failed my CPC mod 2 twice. I bought this as there is no other revision out there. I've got to say the case study questions seem a bit hard but obviously if you put the time in to practice they get alot easier. I passed my CPC mod 2 straight away after purchasing this app so I'm happy. If I had known about this app on my first test I would of bought it then and would of stopped myself failing.

Google User

Hard questions compared to the official test, however if you ask me that's a good thing because it makes your test seem easy. 5*** thanks for the help. Price : Worth the money all day long I wouldn't of passed without it.

Definitely worth the price, this case study practice test is harder than the official test, this app makes people pass FIRST TIME. Highly recommend it, passed my official theory first time thanks to this App.

This app is so useful as there's so many things to learn for the HGV module 2. Edit: After a month of using this app I passed my mod 2 cpc first time

I was told that there was no revision material for the CPC test. This App got me through the test first time! I would suggest reading the "Info" section in the App. Once you've completed that, start doing some "Practice Case Studies," then go onto the "Official Style Tests." I scored 47/50 on the day, and as a first timer, I don't think I could've passed without this App. I would highly recommend it to any newbies looking to pass their CPC first time. Good luck in your exam!

Booked my CPC case studies then downloaded this app I didn’t stop using it for three days; this app helped a lot couldn’t have passed without it, thanks.

- Imagitech Ltd.

- Ethos, King's Road, SA1 Waterfront,

- SWANSEA SA1 8AS, UK

- +44 (0)1792 824438

Small Print

- Data Protection

- Terms of Service

- Privacy Policy

Credentials

- Home

- About

- H G V / L G V

- P C V

- B + E

- Initial CPC

- Periodic CPC

- Contact

- Images

- Videos

Initial Driver CPC Training

All professional LGV and PCV (lorry and bus) drivers legally must hold a Driver Certificate of Professional Competence certificate / Driver CPC qualification before they drive for living. Bains Training Services is one stop leading Driver CPC training provider in London to train you for Driver CPC qualifacations.

There are four modules in the Driver CPC: two are the same as the tests you’ll take for getting your LGV, PCV licence.

- Theory test is the same test as for your LGV licence

- Driver CPC case study test

- Driving ability test: this is the same as the practical test for your LGV licence

- Driver CPC demonstration test / Driver CPC Module 4

You can find more information about Driver CPC on GOV.UK or you can watch this DVSA video for an overview of the Driver CPC. You can also access the HGV and PCV industry guide to driver CPC.

As soon as you’ve passed all four modules, you’ll get a Driver Qualification Card (DQC) which you must carry with you while you’re driving a LGV / Truck or PCV / Bus.

Module 2 Driver CPC Case study

Candidates must pass the case study test before they take the practical D emonstration test. Like the theory test, it is a computer based test. There are different case studies for LGV drivers and PCV drivers. Case studies are short scenarios that you may face in your daily practice. We deliver Module 2 Driver CPC training in our office or you can buy study material from us and parctice at home on your computer. For module 2 training we sell DVDs and books to read and practice.

The case study test lasts 75 minutes and covers 7 case studies, 6 - 8 multiple choice questions from each case study with a possible maximum score of 50. Candidates need to score at least 40 out of 50 to pass the test. Before you start the test, you can have a practice session of up to 15 minutes.

Please watch the Driver CPC Module 2 case study video for an overview of test.

Module 4 Driver CPC Demonstration Test

Driver CPC Module 4 training is all about the safety and security of the vehicle. It is the second part of Driver CPC. Once you have passed your Module 2 (Case study test) you will need to go ahead with the Module 4 (Demonstration test). It lasts for 30 minutes with a pass mark of 80% with 15 out of 20 in each subject. Once you have passed, you will receive your Driver Qualification Card (DQC). The card will be valid for 5 years and you will then have to complete 35 hours Driver CPC Periodic training (Classroom training).

Driver CPC Module 4 training has two different versions. One for truck drivers called Driver CPC Module 4 Training for LGV . Driver CPC Module 4 Training for bus drivers called as Driver CPC Module 4 training for PCV . Module 4 needs to be completed by both LGV and PCV drivers. LGV drivers will need to demonstrate the use of the DVSA Load Securing Demonstration Trolley. Please watch the video that meets your needs.

Candidates will be asked to demonstrate their knowledge and ability in the following subject areas:

- Ability to load the vehicle with due regard for safety rules and proper vehicle use

- Security of the vehicle and contents

- Ability to prevent criminality and trafficking in illegal immigrants

- Ability to assess emergency situations

- Ability to prevent physical risk

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Study Suggests Genetics as a Cause, Not Just a Risk, for Some Alzheimer’s

People with two copies of the gene variant APOE4 are almost certain to get Alzheimer’s, say researchers, who proposed a framework under which such patients could be diagnosed years before symptoms.

By Pam Belluck

Scientists are proposing a new way of understanding the genetics of Alzheimer’s that would mean that up to a fifth of patients would be considered to have a genetically caused form of the disease.

Currently, the vast majority of Alzheimer’s cases do not have a clearly identified cause. The new designation, proposed in a study published Monday, could broaden the scope of efforts to develop treatments, including gene therapy, and affect the design of clinical trials.

It could also mean that hundreds of thousands of people in the United States alone could, if they chose, receive a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s before developing any symptoms of cognitive decline, although there currently are no treatments for people at that stage.

The new classification would make this type of Alzheimer’s one of the most common genetic disorders in the world, medical experts said.

“This reconceptualization that we’re proposing affects not a small minority of people,” said Dr. Juan Fortea, an author of the study and the director of the Sant Pau Memory Unit in Barcelona, Spain. “Sometimes we say that we don’t know the cause of Alzheimer’s disease,” but, he said, this would mean that about 15 to 20 percent of cases “can be tracked back to a cause, and the cause is in the genes.”

The idea involves a gene variant called APOE4. Scientists have long known that inheriting one copy of the variant increases the risk of developing Alzheimer’s, and that people with two copies, inherited from each parent, have vastly increased risk.

The new study , published in the journal Nature Medicine, analyzed data from over 500 people with two copies of APOE4, a significantly larger pool than in previous studies. The researchers found that almost all of those patients developed the biological pathology of Alzheimer’s, and the authors say that two copies of APOE4 should now be considered a cause of Alzheimer’s — not simply a risk factor.

The patients also developed Alzheimer’s pathology relatively young, the study found. By age 55, over 95 percent had biological markers associated with the disease. By 65, almost all had abnormal levels of a protein called amyloid that forms plaques in the brain, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s. And many started developing symptoms of cognitive decline at age 65, younger than most people without the APOE4 variant.

“The critical thing is that these individuals are often symptomatic 10 years earlier than other forms of Alzheimer’s disease,” said Dr. Reisa Sperling, a neurologist at Mass General Brigham in Boston and an author of the study.

She added, “By the time they are picked up and clinically diagnosed, because they’re often younger, they have more pathology.”

People with two copies, known as APOE4 homozygotes, make up 2 to 3 percent of the general population, but are an estimated 15 to 20 percent of people with Alzheimer’s dementia, experts said. People with one copy make up about 15 to 25 percent of the general population, and about 50 percent of Alzheimer’s dementia patients.

The most common variant is called APOE3, which seems to have a neutral effect on Alzheimer’s risk. About 75 percent of the general population has one copy of APOE3, and more than half of the general population has two copies.

Alzheimer’s experts not involved in the study said classifying the two-copy condition as genetically determined Alzheimer’s could have significant implications, including encouraging drug development beyond the field’s recent major focus on treatments that target and reduce amyloid.

Dr. Samuel Gandy, an Alzheimer’s researcher at Mount Sinai in New York, who was not involved in the study, said that patients with two copies of APOE4 faced much higher safety risks from anti-amyloid drugs.

When the Food and Drug Administration approved the anti-amyloid drug Leqembi last year, it required a black-box warning on the label saying that the medication can cause “serious and life-threatening events” such as swelling and bleeding in the brain, especially for people with two copies of APOE4. Some treatment centers decided not to offer Leqembi, an intravenous infusion, to such patients.

Dr. Gandy and other experts said that classifying these patients as having a distinct genetic form of Alzheimer’s would galvanize interest in developing drugs that are safe and effective for them and add urgency to current efforts to prevent cognitive decline in people who do not yet have symptoms.

“Rather than say we have nothing for you, let’s look for a trial,” Dr. Gandy said, adding that such patients should be included in trials at younger ages, given how early their pathology starts.

Besides trying to develop drugs, some researchers are exploring gene editing to transform APOE4 into a variant called APOE2, which appears to protect against Alzheimer’s. Another gene-therapy approach being studied involves injecting APOE2 into patients’ brains.

The new study had some limitations, including a lack of diversity that might make the findings less generalizable. Most patients in the study had European ancestry. While two copies of APOE4 also greatly increase Alzheimer’s risk in other ethnicities, the risk levels differ, said Dr. Michael Greicius, a neurologist at Stanford University School of Medicine who was not involved in the research.

“One important argument against their interpretation is that the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in APOE4 homozygotes varies substantially across different genetic ancestries,” said Dr. Greicius, who cowrote a study that found that white people with two copies of APOE4 had 13 times the risk of white people with two copies of APOE3, while Black people with two copies of APOE4 had 6.5 times the risk of Black people with two copies of APOE3.

“This has critical implications when counseling patients about their ancestry-informed genetic risk for Alzheimer’s disease,” he said, “and it also speaks to some yet-to-be-discovered genetics and biology that presumably drive this massive difference in risk.”

Under the current genetic understanding of Alzheimer’s, less than 2 percent of cases are considered genetically caused. Some of those patients inherited a mutation in one of three genes and can develop symptoms as early as their 30s or 40s. Others are people with Down syndrome, who have three copies of a chromosome containing a protein that often leads to what is called Down syndrome-associated Alzheimer’s disease .

Dr. Sperling said the genetic alterations in those cases are believed to fuel buildup of amyloid, while APOE4 is believed to interfere with clearing amyloid buildup.

Under the researchers’ proposal, having one copy of APOE4 would continue to be considered a risk factor, not enough to cause Alzheimer’s, Dr. Fortea said. It is unusual for diseases to follow that genetic pattern, called “semidominance,” with two copies of a variant causing the disease, but one copy only increasing risk, experts said.

The new recommendation will prompt questions about whether people should get tested to determine if they have the APOE4 variant.

Dr. Greicius said that until there were treatments for people with two copies of APOE4 or trials of therapies to prevent them from developing dementia, “My recommendation is if you don’t have symptoms, you should definitely not figure out your APOE status.”

He added, “It will only cause grief at this point.”

Finding ways to help these patients cannot come soon enough, Dr. Sperling said, adding, “These individuals are desperate, they’ve seen it in both of their parents often and really need therapies.”

Pam Belluck is a health and science reporter, covering a range of subjects, including reproductive health, long Covid, brain science, neurological disorders, mental health and genetics. More about Pam Belluck

The Fight Against Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s is the most common form of dementia, but much remains unknown about this daunting disease..

How is Alzheimer’s diagnosed? What causes Alzheimer’s? We answered some common questions .

A study suggests that genetics can be a cause of Alzheimer’s , not just a risk, raising the prospect of diagnosis years before symptoms appear.

Determining whether someone has Alzheimer’s usually requires an extended diagnostic process . But new criteria could lead to a diagnosis on the basis of a simple blood test .

The F.D.A. has given full approval to the Alzheimer’s drug Leqembi. Here is what to know about i t.

Alzheimer’s can make communicating difficult. We asked experts for tips on how to talk to someone with the disease .

HGV Theory Test Practice 2024

Pass all your hgv modules with our practice material.

Mock HGV Theory Test

The duration of this mock HGV Theory Test is 115 minutes (1 hour 55 minutes) . There are 100 multiple-choice questions . You need 85/100 to pass. You may check answers after each question or you can wait until the end of the test for your results. Good luck!

Sign up to keep track of your progress

Your Progress

You're doing well! Carry on practising to make sure you're prepared for your test. You'll soon see your scores improve!

Tests Taken

Average Score

Do you wish to proceed?

Prepare for your LGV Theory Test with these mock tests

Membership required

Do you want to pass first time?

Hgv theory test category lists.

- 1 Mock HGV Theory Test

- 2.1 Do you want to pass first time?

- 3 HGV Theory Test Category Lists

- 4 About the HGV Theory Test

- 5.1 Measurements

- 5.2 Driving hours & resting period regulations

- 5.3 Braking systems

- 5.4 Measurements

- 5.5 Restricted views

- 5.6 Vehicle condition

- 5.7 Safe & secure loading

- 5.8 Other road users

- 5.9 Manoeuvres

- 5.10 Incidents, accidents, and emergencies

- 5.11 Driver safety

- 5.12 Essential documents

- 5.13 Road and traffic signs

- 5.14 The road

- 6.1 Part 1a – Multiple choice test

- 6.2 Part two – Hazard Perception Test (Module 1b)

- 6.3 After the test

- 7 After passing

About the HGV Theory Test

The HGV theory test consists of two sections:

- Part 1a : A 2-hour multiple-choice test with 100 questions costing £26, and;

- Part 1b : A 30-minute hazard perception test with 19 clips including 20 scorable hazards, costing £11.

These tests do not have to be sat on the same day, but must be completed within 2 years of each other. If you do sit them on the same day, you can do them in whichever order you prefer. However, they must both be passed before you can move on to taking your practical test. The HGV theory test is designed to examine how much you know about everything affecting driving HGVs / LGVs. This means there are broad areas of knowledge you will need to understand. These broad areas are outlined below.

Knowledge Areas

Measurements.

You will need to know the length, width, height, and weight of HGVs / LGVs.

Why you need to know about it – Awareness of the size and weight of your vehicle ensures you are aware of which roads you are able to safely travel on. You will also be able to recognise when restrictions apply.

Driving hours & resting period regulations

You will need to know the rules in relation to rest periods and drivers’ hours. You will need to learn about driving limits, how to follow the tachograph rules, how to keep good records, and keeping your vehicle safe and secure.

Why you need to know about it – You need to be aware of legal requirements to ensure you obey the law and a safe to drive.

Braking systems

You need to learn about the 3 main braking systems on lorries – service, secondary, and parking. You will also need to learn how to take care of air brake systems, how to carry out emergency stops, and how to use escape lanes.

Why you need to know about it – You will need to know how to use them, look after them effectively with proper maintenance, and to understand why this is important.

Restricted views

You need to be aware that some areas around your vehicle will be restricted from your view. The view of other road users may also be restricted due to the size and dimensions of your vehicle.

Why you need to know about it – You need to be aware of this so that you take appropriate positions up on the road and so you and others can drive safely.

Vehicle condition

You will need to be able to spot defects and faults on your vehicle.

Why you need to know about it – AIt is your responsibility to report faults and defects when you notice them.

Safe & secure loading

You will need to understand about how to load a vehicle safely and securely.

Why you need to know about it – You will need to be aware of this in order to safely transport goods and recognise when you may need to use special signs to warn of dangerous loads.

Other road users

You need to be aware of how to carry out manoeuvres and take account of the extra length of your vehicle when turning.

Why you need to know about it – This will help you reduce the risks involved when you are overtaking or when other road users overtake you. It will also help you manage difficult conditions more safely for yourself and others.

Why you need to know about it – You will need to know this so you can manage blind spots and safely carry out manoeuvres in traffic.

Incidents, accidents, and emergencies

It is important to know what to do if you are involved in an accident or if you arrive at one. You will also need to know the safety equipment you are required to carry, how to report an incident, how to deal with fires, and tunnel safety.

Why you need to know about it – This will ensure you are able to help out if needed or know what actions to take if you have been involved to ensure yours and other road users’ safety.

Driver safety

You need to be aware of everything about driver safety from seatbelts, anticipating the road movements of other road users, and potential dangers when exiting your vehicle cab on the offside. You also need to consider driver tiredness, medication, and the importance of not using mobile phones.

To protect yourself and other road users and to meet legal requirements.

Essential documents

You will need to learn about the necessary documentation and regulations in relation to SORN, CPC, and MAM.

Why you need to know about it – You need to learn this because it is the driver’s responsibility. This will ensure you understand what licence categories mean and the restrictions on them. This will ensure you meet legal requirements and avoid fines.

Road and traffic signs

Your knowledge of road signs, road and lane markings, traffic lights, warnings, and signals that may be given by other drivers or the police.

Why you need to know about it – To ensure you can safely and effectively respond to vital instructions on the road and from other road users.

You will need to understand the effect of different weather conditions on the road, how to park safely at night, how to use and change lanes, and how to deal with road gradients.

Why you need to know about it – In order that you are able to reduce risk at all times in all conditions.

The Examination Process

Part 1a – multiple choice test.

The multiple-choice test lasts a total of 2 hours and usually takes place on a touch screen computer. You have 5 minutes set aside for instructions on what to do at the beginning. You can also use this period of five minutes to get comfortable with the touch screen computer and see how the multiple-choice questions will be laid out.

You will then have 1 hour and 55 minutes to answer 100 questions about the 14 areas outlined above. You will have a choice of responses to choose from for each question which will be asked individually. You can select the answer you think is correct either by touching the screen or by using a mouse. Sometimes, more than one answer may be given. You will be reminded of this if you try to move on without clicking on the correct number of answers for a given question. However, if you are unsure about a question and want to move on, you can flag it to return to later on in the test.

To pass the HGV theory test, you will need to get 85 out of 100.

There are 14 topics from which the questions will be drawn from:

- Braking systems – Types of braking system, using your brakes properly, connecting the airlines, maintenance and inspection

- Drivers’ hours and rest periods – Obeying driving limits, following tachograph rules, keeping the correct records, tiredness, vehicle security

- Environmental issues – Reducing fuel consumption and emissions, road surfaces, refuelling

- Essential documents – Documentation, regulations, the driver’s responsibility

- Incidents, accidents and emergencies – Breakdowns, what to do at the scene of an incident, dealing with a vehicle fire, reporting an incident, safety in tunnels

- Leaving the vehicle – Parking, leaving the cab, health and safety, security

- Other road users – Being aware of other road users, showing patience and care

- Restricted view – Mirrors and blind spots, awareness of your vehicle’s size, reversing large vehicles

- Road and traffic signs – Signs, road markings, lane markings, traffic lights and warnings, signals given by drivers and the police

- The driver – Consideration towards other road users, safety equipment, mobile phones when driving, fitness to drive, medication

- The road – Different weather conditions, parking at night, using lanes, dealing with gradients, reducing risk

- Vehicle condition – Wheels and tyres, vehicle maintenance and minor repairs, cold weather, trailer coupling

- Vehicle loading – Security of loads, weight distribution, transporting loads

- Vehicle weights and dimensions – Vehicle size, loading your vehicle, vehicle markings, speed limiters

Part two – Hazard Perception Test (Module 1b)

The hazard perception test lasts up to 25 minutes. It will begin with a short video tutorial video outlining how the test will work. If you miss anything, you can re-run the video again if you need to.

When you are ready, the test will begin. There are 19 video clips in the test. These all feature everyday scenes you might expect to find on the road. There is a total of 20 developing hazards across the 19 clips with each video containing at least one. As there are 20 developing hazards in 19 clips, one of them will have a second developing hazard for you to look out for.

There is a 10-second pause between each clip which allows you to survey the scene. The faster you respond to developing hazards, the better score you will get. In the test, you’ll need to respond to the developing hazards early. The top score for the fastest response to a hazard is five. However, the scenario will not change after you click. Instead, a red flag will appear at the bottom of your screen. This indicates your response has registered. If you have too many flags, you may be penalized.

Unlike the theory test, your hazard perception responses cannot be reviewed. This is because you will only have one chance to react when it comes to driving on the road for real and in your practical test.

You will need 67 out of 100 to pass the hazard perception test.

After the test

After the hazard perception test, you will be asked to answer some simple customer survey questions followed by some potential future sample questions. You are not required to answer these questions but if you do, any of the information you give will remain both anonymous and confidential. If you do take the sample questions, they will not change your test results.

After passing

On the day, you will receive a letter detailing your results for whichever part of the theory test that has been completed.

Once both parts are passed, a theory test certificate will be sent to you in the post. This has a theory test number on it which you will need to provide when booking your practical test. However, the test certificate is only valid for 2 years and there are no exceptions for this.

Modules 1a and 1b can be taken in any order, and at different sittings, but you must pass both modules to pass the theory test. Should you be required to take the CPC Module 2 case studies test, you may sit this test either before or after completing both theory test modules. You must have passed both the theory test and, if applicable, the case studies test to enable you to take the practical test.

- Open access

- Published: 09 May 2024

Evaluation of integrated community case management of the common childhood illness program in Gondar city, northwest Ethiopia: a case study evaluation design

- Mekides Geta 1 ,

- Geta Asrade Alemayehu 2 ,

- Wubshet Debebe Negash 2 ,

- Tadele Biresaw Belachew 2 ,

- Chalie Tadie Tsehay 2 &

- Getachew Teshale 2

BMC Pediatrics volume 24 , Article number: 310 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

89 Accesses

Metrics details

Integrated Community Case Management (ICCM) of common childhood illness is one of the global initiatives to reduce mortality among under-five children by two-thirds. It is also implemented in Ethiopia to improve community access and coverage of health services. However, as per our best knowledge the implementation status of integrated community case management in the study area is not well evaluated. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the implementation status of the integrated community case management program in Gondar City, Northwest Ethiopia.

A single case study design with mixed methods was employed to evaluate the process of integrated community case management for common childhood illness in Gondar town from March 17 to April 17, 2022. The availability, compliance, and acceptability dimensions of the program implementation were evaluated using 49 indicators. In this evaluation, 484 mothers or caregivers participated in exit interviews; 230 records were reviewed, 21 key informants were interviewed; and 42 observations were included. To identify the predictor variables associated with acceptability, we used a multivariable logistic regression analysis. Statistically significant variables were identified based on the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value. The qualitative data was recorded, transcribed, and translated into English, and thematic analysis was carried out.

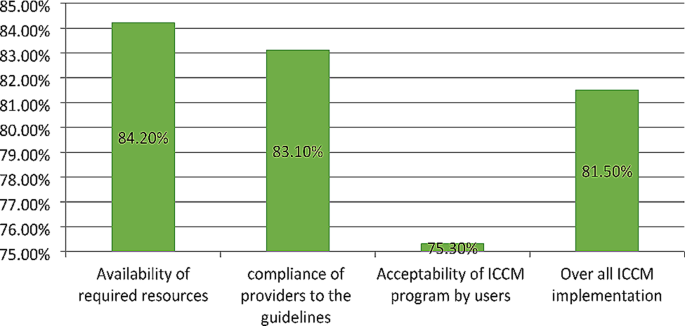

The overall implementation of integrated community case management was 81.5%, of which availability (84.2%), compliance (83.1%), and acceptability (75.3%) contributed. Some drugs and medical equipment, like Cotrimoxazole, vitamin K, a timer, and a resuscitation bag, were stocked out. Health care providers complained that lack of refreshment training and continuous supportive supervision was the common challenges that led to a skill gap for effective program delivery. Educational status (primary AOR = 0.27, 95% CI:0.11–0.52), secondary AOR = 0.16, 95% CI:0.07–0.39), and college and above AOR = 0.08, 95% CI:0.07–0.39), prescribed drug availability (AOR = 2.17, 95% CI:1.14–4.10), travel time to the to the ICCM site (AOR = 3.8, 95% CI:1.99–7.35), and waiting time (AOR = 2.80, 95% CI:1.16–6.79) were factors associated with the acceptability of the program by caregivers.

Conclusion and recommendation

The overall implementation status of the integrated community case management program was judged as good. However, there were gaps observed in the assessment, classification, and treatment of diseases. Educational status, availability of the prescribed drugs, waiting time and travel time to integrated community case management sites were factors associated with the program acceptability. Continuous supportive supervision for health facilities, refreshment training for HEW’s to maximize compliance, construction clean water sources for HPs, and conducting longitudinal studies for the future are the forwarded recommendation.

Peer Review reports

Integrated Community Case Management (ICCM) is a critical public health strategy for expanding the coverage of quality child care services [ 1 , 2 ]. It mainly concentrated on curative care and also on the diagnosis, treatment, and referral of children who are ill with infectious diseases [ 3 , 4 ].

Based on the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) recommendations, Ethiopia adopted and implemented a national policy supporting community-based treatment of common childhood illnesses like pneumonia, Diarrhea, uncomplicated malnutrition, malaria and other febrile illness and Amhara region was one the piloted regions in late 2010 [ 5 ]. The Ethiopian primary healthcare units, established at district levels include primary hospitals, health centers (HCs), and health posts (HPs). The HPs are run by Health Extension Workers (HEWs), and they have function of monitoring health programs and disease occurrence, providing health education, essential primary care services, and timely referrals to HCs [ 6 , 7 ]. The Health Extension Program (HEP) uses task shifting and community ownership to provide essential health services at the first level using the health development army and a network of woman volunteers. These groups are organized to promote health and prevent diseases through community participation and empowerment by identifying the salient local bottlenecks which hinder vital maternal, neonatal, and child health service utilization [ 8 , 9 ].

One of the key steps to enhance the clinical case of health extension staff is to encourage better growth and development among under-five children by health extension. Healthy family and neighborhood practices are also encouraged [ 10 , 11 ]. The program also combines immunization, community-based feeding, vitamin A and de-worming with multiple preventive measures [ 12 , 13 ]. Now a days rapidly scaling up of ICCM approach to efficiently manage the most common causes of morbidity and mortality of children under the age of five in an integrated manner at the community level is required [ 14 , 15 ].

Over 5.3 million children are died at a global level in 2018 and most causes (75%) are preventable or treatable diseases such as pneumonia, malaria and diarrhea [ 16 ]. About 99% of the global burden of mortality and morbidity of under-five children which exists in developing countries are due to common childhood diseases such as pneumonia, diarrhea, malaria and malnutrition [ 17 ].

In 2013, the mortality rate of under-five children in Sub-Saharan Africa decreased to 86 deaths per 1000 live birth and estimated to be 25 per 1000live births by 2030. However, it is a huge figure and the trends are not sufficient to reach the target [ 18 ]. About half of global under-five deaths occurred in sub-Saharan Africa. And from the top 26 nations burdened with 80% of the world’s under-five deaths, 19 are in sub-Saharan Africa [ 19 ].

To alleviate the burden, the Ethiopian government tries to deliver basic child care services at the community level by trained health extension workers. The program improves the health of the children not only in Ethiopia but also in some African nations. Despite its proven benefits, the program implementation had several challenges, in particular, non-adherence to the national guidelines among health care workers [ 20 ]. Addressing those challenges could further improve the program performance. Present treatment levels in sub-Saharan Africa are unacceptably poor; only 39% of children receive proper diarrhea treatment, 13% of children with suspected pneumonia receive antibiotics, 13% of children with fever receive a finger/heel stick to screen for malaria [ 21 ].

To improve the program performance, program gaps should be identified through scientific evaluations and stakeholder involvement. This evaluation not only identify gaps but also forward recommendations for the observed gaps. Furthermore, the implementation status of ICCM of common childhood illnesses has not been evaluated in the study area yet. Therefore, this work aimed to evaluate the implementation status of integrated community case management program implementation in Gondar town, northwest Ethiopia. The findings may be used by policy makers, healthcare providers, funders and researchers.

Method and material

Evaluation design and settings.

A single-case study design with concurrent mixed-methods evaluation was conducted in Gondar city, northwest Ethiopia, from March 17 to April 17, 2022. The evaluability assessment was done from December 15–30, 2021. Both qualitative and quantitative data were collected concurrently, analyzed separately, and integrated at the result interpretation phase.

The evaluation area, Gondar City, is located in northwest Ethiopia, 740 km from Addis Ababa, the capital city of the country. It has six sub-cities and thirty-six kebeles (25 urban and 11 rural). In 2019, the estimated total population of the town was 338,646, and 58,519 (17.3%) were under-five children. In the town there are eight public health centers and 14 health posts serving the population. All health posts provide ICCM service for more than 70,852 populations.

Evaluation approach and dimensions

Program stakeholders.

The evaluation followed a formative participatory approach by engaging the potential stakeholders in the program. Prior to the development of the proposal, an extensive discussion was held with the Gondar City Health Department to identify other key stakeholders in the program. Service providers at each health facility (HCs and HPs), caretakers of sick children, the Gondar City Health Office (GCHO), the Amhara Regional Health Bureau (ARHB), the Minister of Health (MoH), and NGOs (IFHP and Save the Children) were considered key stakeholders. During the Evaluability Assessment (EA), the stakeholders were involved in the development of evaluation questions, objectives, indicators, and judgment criteria of the evaluation.

Evaluation dimensions

The availability and acceptability dimensions from the access framework [ 22 ] and compliance dimension from the fidelity framework [ 23 ] were used to evaluate the implementation of ICCM.

Population and samplings

All under-five children and their caregivers attended at the HPs; program implementers (health extension workers, healthcare providers, healthcare managers, PHCU focal persons, MCH coordinators, and other stakeholders); and ICCM records and registries in the health posts of Gondar city administration were included in the evaluation. For quantitative data, the required sample size was proportionally allocated for each health post based on the number of cases served in the recent one month. But the qualitative sample size was determined by data saturation, and the samples were selected purposefully.

The data sources and sample size for the compliance dimension were all administrative records/reports and ICCM registration books (230 documents) in all health posts registered from December 1, 2021, to February 30, 2022 (three months retrospectively) included in the evaluation. The registries were assessed starting from the most recent registration number until the required sample size was obtained for each health post.

The sample size to measure the mothers’/caregivers’ acceptability towards ICCM was calculated by taking prevalence of caregivers’ satisfaction on ICCM program p = 74% from previously similar study [ 24 ] and considering standard error 4% at 95% CI and 10% non- responses, which gave 508. Except those who were seriously ill, all caregivers attending the ICCM sites during data collection were selected and interviewed consecutively.

The availability of required supplies, materials and human resources for the program were assessed in all 14HPs. The data collectors observed the health posts and collected required data by using a resources inventory checklist.

A total of 70 non-participatory patient-provider interactions were also observed. The observations were conducted per each health post and for health posts which have more than one health extension workers one of them were selected randomly. The observation findings were used to triangulate the findings obtained through other data collection techniques. Since people may act accordingly to the standards when they know they are observed for their activities, we discarded the first two observations from analysis. It is one of the strategies to minimize the Hawthorne effect of the study. Finally a total of 42 (3 in each HPs) observations were included in the analysis.

Twenty one key informants (14 HEWs, 3 PHCU focal person, 3 health center heads and one MCH coordinator) were interviewed. These key informants were selected since they are assumed to be best teachers in the program. Besides originally developed key informant interview questions, the data collectors probed them to get more detail and clear information.

Variables and measurement

The availability of resources, including trained healthcare workers, was examined using 17 indicators, with weighted score of 35%. Compliance was used to assess HEWs’ adherence to the ICCM treatment guidelines by observing patient-provider interactions and conducting document reviews. We used 18 indicators and a weighted value of 40%.

Mothers’ /caregivers’/ acceptance of ICCM service was examined using 14 indicators and had a weighted score of 25%. The indicators were developed with a five-point Likert scale (1: strongly disagree, 2: disagree, 3: neutral, 4: agree and 5: strongly agree). The cut off point for this categorization was calculated using the demarcation threshold formula: ( \(\frac{\text{t}\text{o}\text{t}\text{a}\text{l}\, \text{h}\text{i}\text{g}\text{h}\text{e}\text{s}\text{t}\, \text{s}\text{c}\text{o}\text{r}\text{e}-\,\text{t}\text{o}\text{t}\text{a}\text{l}\, \text{l}\text{o}\text{w}\text{e}\text{s}\text{t} \,\text{s}\text{c}\text{o}\text{r}\text{e}}{2}) +total lowest score\) ( 25 – 27 ). Those mothers/caregivers/ who scored above cut point (42) were considered as “satisfied”, otherwise “dissatisfied”. The indicators were adapted from the national ICCM and IMNCI implementation guideline and other related evaluations with the participation of stakeholders. Indicator weight was given by the stakeholders during EA. Indicators score was calculated using the formula \(\left(achieved \,in \%=\frac{indicator \,score \,x \,100}{indicator\, weight} \right)\) [ 26 , 28 ].

The independent variables for the acceptability dimension were socio-demographic and economic variables (age, educational status, marital status, occupation of caregiver, family size, income level, and mode of transport), availability of prescribed drugs, waiting time, travel time to ICCM site, home to home visit, consultation time, appointment, and source of information.

The overall implementation of ICCM was measured by using 49 indicators over the three dimensions: availability (17 indicators), compliance (18 indicators) and acceptability (14 indicators).

Program logic model

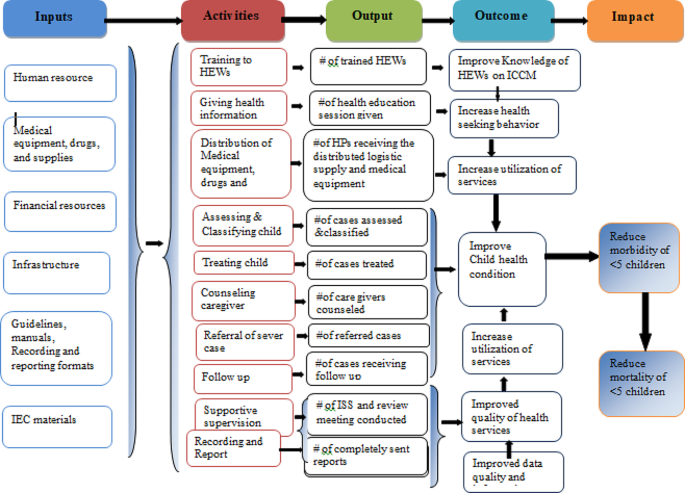

Based on the constructed program logic model and trained health care providers, mothers/caregivers received health information and counseling on child feeding; children were assessed, classified, and treated for disease, received follow-up; they were checked for vitamin A; and deworming and immunization status were the expected outputs of the program activities. Improved knowledge of HEWs on ICCM, increased health-seeking behavior, improved quality of health services, increased utilization of services, improved data quality and information use, and improved child health conditions are considered outcomes of the program. Reduction of under-five morbidity and mortality and improving quality of life in the society are the distant outcomes or impacts of the program (Fig. 1 ).

Integrated community case management of childhood illness program logic model in Gondar City in 2022

Data collection tools and procedure

Resource inventory and data extraction checklists were adapted from standard ICCM tool and check lists [ 29 ]. A structured interviewer administered questionnaire was adapted by referring different literatures [ 30 , 31 ] to measure the acceptability of ICCM. The key informant interview (KII) guide was also developed to explore the views of KIs. The interview questionnaire and guide were initially developed in English and translated into the local language (Amharic) and finally back to English to ensure consistency. All the interviews were done in the local language, Amharic.

Five trained clinical nurses and one BSC nurse were recruited from Gondar zuria and Wegera district as data collectors and supervisors, respectively. Two days training on the overall purpose of the evaluation and basic data collection procedures were provided prior to data collection. Then, both quantitative and qualitative data were gathered at the same time. The quantitative data were gathered from program documentation, charts of ICCM program visitors and, exit interview. Interviews with 21 KIIs and non-participatory observations of patient-provider interactions were used to acquire qualitative data. Key informant interviews were conducted to investigate the gaps and best practices in the implementation of the ICCM program.

A pretest was conducted to 26 mothers/caregivers/ at Maksegnit health post and appropriate modifications were made based on the pretest results. The data collectors were supervised and principal evaluator examined the completeness and consistency of the data on a daily basis.

Data management and analysis

For analysis, quantitative data were entered into epi-data version 4.6 and exported to Stata 14 software for analysis. Narration and tabular statistics were used to present descriptive statistics. Based on established judgment criteria, the total program implementation was examined and interpreted as a mix of the availability, compliance, and acceptability dimensions. To investigate the factors associated with ICCM acceptance, a binary logistic regression analysis was performed. During bivariable analysis, variables with p-values less than 0.25 were included in multivariable analysis. Finally, variables having a p-value less than 0.05 and an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) were judged statistically significant. Qualitative data were collected recorded, transcribed into Amharic, then translated into English and finally coded and thematically analyzed.

Judgment matrix analysis

The weighted values of availability, compliance, and acceptability dimensions were 35, 40, and 25 based on the stakeholder and investigator agreement on each indicator, respectively. The judgment parameters for each dimension and the overall implementation of the program were categorized as poor (< 60%), fair (60–74.9%), good (75-84.9%), and very good (85–100%).

Availability of resources

A total of 26 HEWs were assigned within the fourteen health posts, and 72.7% of them were trained on ICCM to manage common childhood illnesses in under-five children. However, the training was given before four years, and they didn’t get even refreshment training about ICCM. The KII responses also supported that the shortage of HEWs at the HPs was the problem in implementing the program properly.

I am the only HEW in this health post and I have not been trained on ICCM program. So, this may compromise the quality of service and client satisfaction.(25 years old HEW with two years’ experience)

All observed health posts had ICCM registration books, monthly report and referral formats, functional thermometer, weighting scale and MUAC tape meter. However, timer and resuscitation bag was not available in all HPs. Most of the key informant finding showed that, in all HPs there was no shortage of guideline, registration book and recording tool; however, there was no OTP card in some health posts.

“Guideline, ICCM registration book for 2–59 months of age, and other different recording and reporting formats and booklet charts are available since September/2016. However, OTP card is not available in most HPs.”. (A 30 years male health center director)

Only one-fifth (21%) of HPs had a clean water source for drinking and washing of equipment. Most of Key-informant interview findings showed that the availability of infrastructures like water was not available in most HPs. Poor linkage between HPs, HCs, town health department, and local Kebele administer were the reason for unavailability.

Since there is no water for hand washing, or drinking, we obligated to bring water from our home for daily consumptions. This increases the burden for us in our daily activity. (35 years old HEW)

Most medicines, such as anti-malaria drugs with RDT, Quartem, Albendazole, Amoxicillin, vitamin A capsules, ORS, and gloves, were available in all the health posts. Drugs like zinc, paracetamol, TTC eye ointment, and folic acid were available in some HPs. However, cotrimoxazole and vitamin K capsules were stocked-out in all health posts for the last six months. The key informant also revealed that: “Vitamin K was not available starting from the beginning of this program and Cotrimoxazole was not available for the past one year and they told us they would avail it soon but still not availed. Some essential ICCM drugs like anti malaria drugs, De-worming, Amoxicillin, vitamin A capsules, ORS and medical supplies were also not available in HCs regularly.”(28 years’ Female PHCU focal)

The overall availability of resources for ICCM implementation was 84.2% which was good based on our presetting judgment parameter (Table 1 ).

Health extension worker’s compliance

From the 42 patient-provider interactions, we found that 85.7%, 71.4%, 76.2%, and 95.2% of the children were checked for body temperature, weight, general danger signs, and immunization status respectively. Out of total (42) observation, 33(78.6%) of sick children were classified for their nutritional status. During observation time 29 (69.1%) of caregivers were counseled by HEWs on food, fluid and when to return back and 35 (83.3%) of children were appointed for next follow-up visit. Key informant interviews also affirmed that;

“Most of our health extension workers were trained on ICCM program guidelines but still there are problems on assessment classification and treatment of disease based on guidelines and standards this is mainly due to lack refreshment training on the program and lack of continuous supportive supervision from the respective body.” (27years’ Male health center head)

From 10 clients classified as having severe pneumonia cases, all of them were referred to a health center (with pre-referral treatment), and from those 57 pneumonia cases, 50 (87.7%) were treated at the HP with amoxicillin or cotrimoxazole. All children with severe diarrhea, very severe disease, and severe complicated malnutrition cases were referred to health centers with a pre-referral treatment for severe dehydration, very severe febrile disease, and severe complicated malnutrition, respectively. From those with some dehydration and no dehydration cases, (82.4%) and (86.8%) were treated at the HPs for some dehydration (ORS; plan B) and for no dehydration (ORS; plan A), respectively. Moreover, zinc sulfate was prescribed for 63 (90%) of under-five children with some dehydration or no dehydration. From 26 malaria cases and 32 severe uncomplicated malnutrition and moderate acute malnutrition cases, 20 (76.9%) and 25 (78.1%) were treated at the HPs, respectively. Of the total reviewed documents, 56 (93.3%), 66 (94.3%), 38 (84.4%), and 25 (78.1%) of them were given a follow-up date for pneumonia, diarrhea, malaria, and malnutrition, respectively.

Supportive supervision and performance review meetings were conducted only in 10 (71.4%) HPs, but all (100%) HPs sent timely reports to the next supervisory body.

Most of the key informants’ interview findings showed that supportive supervision was not conducted regularly and for all HPs.

I had mentored and supervised by supportive supervision teams who came to our health post at different times from health center, town health office and zonal health department. I received this integrated supervision from town health office irregularly, but every month from catchment health center and last integrated supportive supervision from HC was on January. The problem is the supervision was conducted for all programs.(32 years’ old and nine years experienced female HEW)

Moreover, the result showed that there was poor compliance of HEWs for the program mainly due to weak supportive supervision system of managerial and technical health workers. It was also supported by key informants as:

We conducted supportive supervision and performance review meeting at different time, but still there was not regular and not addressed all HPs. In addition to this the supervision and review meeting was conducted as integration of ICCM program with other services. The other problem is that most of the time we didn’t used checklist during supportive supervision. (Mid 30 years old male HC director)

Based on our observation and ICCM document review, 83.1% of the HEWs were complied with the ICCM guidelines and judged as fair (Table 2 ).

Acceptability of ICCM program

Sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics of participants.

A total of 484 study participants responded to the interviewer-administered questionnaire with a response rate of 95.3%. The mean age of study participants was 30.7 (SD ± 5.5) years. Of the total caregivers, the majority (38.6%) were categorized under the age group of 26–30 years. Among the total respondents, 89.3% were married, and regarding religion, the majorities (84.5%) were Orthodox Christian followers. Regarding educational status, over half of caregivers (52.1%) were illiterate (unable to read or write). Nearly two-thirds of the caregivers (62.6%) were housewives (Table 3 ).

All the caregivers came to the health post on foot, and most of them 418 (86.4%) arrived within one hour. The majority of 452 (93.4%) caregivers responded that the waiting time to get the service was less than 30 min. Caregivers who got the prescribed drugs at the health post were 409 (84.5%). Most of the respondents, 429 (88.6%) and 438 (90.5%), received counseling services on providing extra fluid and feeding for their sick child and were given a follow-up date.

Most 298 (61.6%) of the caregivers were satisfied with the convenience of the working hours of HPs, and more than three-fourths (80.8%) were satisfied with the counseling services they received. Most of the respondents, 366 (75.6%), were satisfied with the appropriateness of waiting time and 431 (89%) with the appropriateness of consultation time. The majority (448 (92.6%) of caregivers were satisfied with the way of communicating with HEWs, and 269 (55.6%) were satisfied with the knowledge and competence of HEWs. Nearly half of the caregivers (240, or 49.6%) were satisfied with the availability of drugs at health posts.

The overall acceptability of the ICCM program was 75.3%, which was judged as good. A low proportion of acceptability was measured on the cleanliness of the health posts, the appropriateness of the waiting area, and the competence and knowledge of the HEWs. On the other hand, high proportion of acceptability was measured on appropriateness of waiting time, way of communication with HEWs, and the availability of drugs (Table 4 ).

Factors associated with acceptability of ICCM program

In the final multivariable logistic regression analysis, educational status of caregivers, availability of prescribed drugs, time to arrive, and waiting time were factors significantly associated with the satisfaction of caregivers with the ICCM program.

Accordingly, the odds of caregivers with primary education, secondary education, and college and above were 73% (AOR = 0.27, 95% CI: 0.11–0.52), 84% (AOR = 0.16, 95% CI: 0.07–0.39), and 92% (AOR = 0.08, 95% CI: 0.07–0.40) less likely to accept the program as compared to mothers or caregivers who were not able to read and write, respectively. The odds of caregivers or mothers who received prescribed drugs were 2.17 times more likely to accept the program as compared to their counters (AOR = 2.17, 95% CI: 1.14–4.10). The odds of caregivers or mothers who waited for services for less than 30 min were 2.8 times more likely to accept the program as compared to those who waited for more than 30 min (AOR = 2.80, 95% CI: 1.16–6.79). Moreover, the odds of caregivers/mothers who traveled an hour or less for service were 3.8 times more likely to accept the ICCM program as compared to their counters (AOR = 3.82, 95% CI:1.99–7.35) (Table 5 ).

Overall ICCM program implementation and judgment

The implementation of the ICCM program in Gondar city administration was measured in terms of availability (84.2%), compliance (83.1%), and acceptability (75.3%) dimensions. In the availability dimension, amoxicillin, antimalarial drugs, albendazole, Vit. A, and ORS were available in all health posts, but only six HPs had Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Feedings, three HPs had ORT Corners, and none of the HPs had functional timers. In all health posts, the health extension workers asked the chief to complain, correctly assessed for pneumonia, diarrhea, malaria, and malnutrition, and sent reports based on the national schedule. However, only 70% of caretakers counseled about food, fluids, and when to return, 66% and 76% of the sick children were checked for anemia and other danger signs, respectively. The acceptability level of the program by caretakers and caretakers’/mothers’ educational status, waiting time to get the service and travel time ICCM sites were the factors affecting its acceptability. The overall ICCM program in Gondar city administration was 81.5% and judged as good (Fig. 2 ).

Overall ICCM program implementation and the evaluation dimensions in Gondar city administration, 2022

The implementation status of ICCM was judged by using three dimensions including availability, compliance and acceptability of the program. The judgment cut of points was determined during evaluability assessment (EA) along with the stakeholders. As a result, we found that the overall implementation status of ICCM program was good as per the presetting judgment parameter. Availability of resources for the program implementation, compliance of HEWs to the treatment guideline and acceptability of the program services by users were also judged as good as per the judgment parameter.

This evaluation showed that most medications, equipment and recording and reporting materials available. This finding was comparable with the standard ICCM treatment guide line [ 10 ]. On the other hand trained health care providers, some medications like Zink, Paracetamol and TTC eye ointment, folic acid and syringes were not found in some HPs. However the finding was higher than the study conducted in SNNPR on selected health posts [ 33 ] and a study conducted in Soro district, southern Ethiopia [ 24 ]. The possible reason might be due to low interruption of drugs at town health office or regional health department stores, regular supplies of essential drugs and good supply management and distribution of drug from health centers to health post.

The result of this evaluation showed that only one fourth of health posts had functional ORT Corner which was lower compared to the study conducted in SNNPR [ 34 ]. This might be due poor coverage of functional pipe water in the kebeles and the installation was not set at the beginning of health post construction as reported from one of ICCM program coordinator.

Compliance of HEWs to the treatment guidelines in this evaluation was higher than the study done in southern Ethiopia (65.6%) [ 24 ]. This might be due to availability of essential drugs educational level of HEWs and good utilization of ICCM guideline and chart booklet by HEWs. The observations showed most of the sick children were assessed for danger sign, weight, and temperature respectively. This finding is lower than the study conducted in Rwanda [ 35 ]. This difference might be due to lack of refreshment training and regular supportive supervision for HEWs. This also higher compared to the study done in three regions of Ethiopia indicates that 88%, 92% and 93% of children classified as per standard for Pneumonia, diarrhea and malaria respectively [ 36 ]. The reason for this difference may be due to the presence of medical equipment and supplies including RDT kit for malaria, and good educational level of HEWs.

Moreover most HPs received supportive supervision and performance review meeting was conducted and all of them send reports timely to next level. The finding of this evaluation was lower than the study conducted on implementation evaluation of ICCM program southern Ethiopia [ 24 ] and study done in three regions of Ethiopia (Amhara, Tigray and SNNPR) [ 37 ]. This difference might be due sample size variation.

The overall acceptability of the ICCM program was less than the presetting judgment parameter but slightly higher compared to the study in southern Ethiopia [ 24 ]. This might be due to presence of essential drugs for treating children, reasonable waiting and counseling time provided by HEWs, and smooth communication between HEWs and caregivers. In contrast, this was lower than similar studies conducted in Wakiso district, Uganda [ 38 ]. The reason for this might be due to contextual difference between the two countries, inappropriate waiting area to receive the service and poor cleanness of the HPs in our study area. Low acceptability of caregivers to ICCM service was observed in the appropriateness of waiting area, availability of drugs, cleanness of health post, and competence of HEWs while high level of caregiver’s acceptability was consultation time, counseling service they received, communication with HEWs, treatment given for their sick children and interest to return back for ICCM service.

Caregivers who achieved primary, secondary, and college and above were more likely accept the program services than those who were illiterate. This may more educated mothers know about their child health condition and expect quality service from healthcare providers which is more likely reduce the acceptability of the service. The finding is congruent with a study done on implementation evaluation of ICCM program in southern Ethiopia [ 24 ]. However, inconsistent with a study conducted in wakiso district in Uganda [ 38 ]. The possible reason for this might be due to contextual differences between the two countries. The ICCM program acceptability was high in caregivers who received all prescribed drugs than those did not. Caregivers those waited less than 30 min for service were more accepted ICCM services compared to those more than 30 minutes’ waiting time. This finding is similar compared with the study conducted on implementation evaluation of ICCM program in southern Ethiopia [ 24 ]. In contrary, the result was incongruent with a survey result conducted by Ethiopian public health institute in all regions and two administrative cities of Ethiopia [ 39 ]. This variation might be due to smaller sample size in our study the previous one. Moreover, caregivers who traveled to HPs less than 60 min were more likely accepted the program than who traveled more and the finding was similar with the study finding in Jimma zone [ 40 ].

Strengths and limitations

This evaluation used three evaluation dimensions, mixed method and different data sources that would enhance the reliability and credibility of the findings. However, the study might have limitations like social desirability bias, recall bias and Hawthorne effect.

The implementation of the ICCM program in Gondar city administration was measured in terms of availability (84.2%), compliance (83.1%), and acceptability (75.3%) dimensions. In the availability dimension, amoxicillin, antimalarial drugs, albendazole, Vit. A, and ORS were available in all health posts, but only six HPs had Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Feedings, three HPs had ORT Corners, and none of the HPs had functional timers.

This evaluation assessed the implementation status of the ICCM program, focusing mainly on availability, compliance, and acceptability dimensions. The overall implementation status of the program was judged as good. The availability dimension is compromised due to stock-outs of chloroquine syrup, cotrimoxazole, and vitamin K and the inaccessibility of clean water supply in some health posts. Educational statuses of caregivers, availability of prescribed drugs at the HPs, time to arrive to HPs, and waiting time to receive the service were the factors associated with the acceptability of the ICCM program.

Therefore, continuous supportive supervision for health facilities, and refreshment training for HEW’s to maximize compliance are recommended. Materials and supplies shall be delivered directly to the health centers or health posts to solve the transportation problem. HEWs shall document the assessment findings and the services provided using the registration format to identify their gaps, limitations, and better performances. The health facilities and local administrations should construct clean water sources for health facilities. Furthermore, we recommend for future researchers and program evaluators to conduct longitudinal studies to know the causal relationship of the program interventions and the outcomes.

Data availability

Data will be available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey

Health Center/Health Facility

Health Extension Program

Health Extension Workers

Health Post

Health Sector Development Plan

Integrated Community Case Management of Common Childhood Illnesses

Information Communication and Education

Integrated Family Health Program

Integrated Management of Neonatal and Childhood Illness

Integrated Supportive Supervision

Maternal and Child Health

Mid Upper Arm Circumference

Non-Government Organization

Oral Rehydration Salts

Outpatient Therapeutic program

Primary health care unit

Rapid Diagnostics Test

Ready to Use Therapeutic Foods

Sever Acute Malnutrition

South Nation Nationalities People Region

United Nations International Child Emergency Fund

World Health Organization

Brenner JL, Barigye C, Maling S, Kabakyenga J, Nettel-Aguirre A, Buchner D, et al. Where there is no doctor: can volunteer community health workers in rural Uganda provide integrated community case management? Afr Health Sci. 2017;17(1):237–46.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Mubiru D, Byabasheija R, Bwanika JB, Meier JE, Magumba G, Kaggwa FM, et al. Evaluation of integrated community case management in eight districts of Central Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0134767.

Samuel S, Arba A. Utilization of integrated community case management service and associated factors among mothers/caregivers who have sick eligible children in southern Ethiopia. Risk Manage Healthc Policy. 2021;14:431.

Article Google Scholar

Kavle JA, Pacqué M, Dalglish S, Mbombeshayi E, Anzolo J, Mirindi J, et al. Strengthening nutrition services within integrated community case management (iCCM) of childhood illnesses in the Democratic Republic of Congo: evidence to guide implementation. Matern Child Nutr. 2019;15:e12725.

Miller NP, Amouzou A, Tafesse M, Hazel E, Legesse H, Degefie T, et al. Integrated community case management of childhood illness in Ethiopia: implementation strength and quality of care. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;91(2):424.

WHO. Annual report 2016: Partnership and policy engagement. World Health Organization, 2017.

Banteyerga H. Ethiopia’s health extension program: improving health through community involvement. MEDICC Rev. 2011;13:46–9.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Wang H, Tesfaye R, Ramana NV, Chekagn G. CT. Ethiopia health extension program: an institutionalized community approach for universal health coverage. The World Bank; 2016.

Donnelly J. Ethiopia gears up for more major health reforms. Lancet. 2011;377(9781):1907–8.

Legesse H, Degefie T, Hiluf M, Sime K, Tesfaye C, Abebe H, et al. National scale-up of integrated community case management in rural Ethiopia: implementation and early lessons learned. Ethiop Med J. 2014;52(Suppl 3):15–26.

Google Scholar

Miller NP, Amouzou A, Hazel E, Legesse H, Degefie T, Tafesse M et al. Assessment of the impact of quality improvement interventions on the quality of sick child care provided by Health Extension workers in Ethiopia. J Global Health. 2016;6(2).

Oliver K, Young M, Oliphant N, Diaz T, Kim JJNYU. Review of systematic challenges to the scale-up of integrated community case management. Emerging lessons & recommendations from the catalytic initiative (CI/IHSS); 2012.

FMoH E. Health Sector Transformation Plan 2015: https://www.slideshare.net . Accessed 12 Jan 2022.

McGorman L, Marsh DR, Guenther T, Gilroy K, Barat LM, Hammamy D, et al. A health systems approach to integrated community case management of childhood illness: methods and tools. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2012;87(5 Suppl):69.

Young M, Wolfheim C, Marsh DR, Hammamy D. World Health Organization/United Nations Children’s Fund joint statement on integrated community case management: an equity-focused strategy to improve access to essential treatment services for children. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2012;87(5 Suppl):6.

Ezbakhe F, Pérez-Foguet A. Child mortality levels and trends. Demographic Research.2020;43:1263-96.

UNICEF, Ending child deaths from pneumonia and diarrhoea. 2016 report: Available at https://data.unicef.org. accessed 13 Jan 2022.

UNITED NATIONS, The Millinium Development Goals Report 2015: Available at https://www.un.org.Accessed 12 Jan 2022

Bent W, Beyene W, Adamu A. Factors Affecting Implementation of Integrated Community Case Management Of Childhood Illness In South West Shoa Zone, Central Ethiopia 2015.

Abdosh B. The quality of hospital services in eastern Ethiopia: Patient’s perspective.The Ethiopian Journal of Health Development. 2006;20(3).

Young M, Wolfheim C, Marsh DR, Hammamy DJTAjotm, hygiene. World Health Organization/United Nations Children’s Fund joint statement on integrated community case management: an equity-focused strategy to improve access to essential treatment services for children.2012;87(5_Suppl):6–10.

Obrist B, Iteba N, Lengeler C, Makemba A, Mshana C, Nathan R, et al. Access to health care in contexts of livelihood insecurity: a framework for analysis and action.PLoS medicine. 2007;4(10):e308.

Carroll C, Patterson M, Wood S, Booth A, Rick J, Balain S. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implementation science. 2007;2(1):1–9.

Dunalo S, Tadesse B, Abraham G. Implementation Evaluation of Integrated Community Case Management of Common Childhood Illness (ICCM) Program in Soro Woreda, Hadiya Zone Southern Ethiopia 2017 2017.

Asefa G, Atnafu A, Dellie E, Gebremedhin T, Aschalew AY, Tsehay CT. Health System Responsiveness for HIV/AIDS Treatment and Care Services in Shewarobit, North Shewa Zone, Ethiopia. Patient preference and adherence. 2021;15:581.

Gebremedhin T, Daka DW, Alemayehu YK, Yitbarek K, Debie A. Process evaluation of the community-based newborn care program implementation in Geze Gofa district,south Ethiopia: a case study evaluation design. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2019;19(1):1–13.

Pitaloka DS, Rizal A. Patient’s satisfaction in antenatal clinic hospital Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. Jurnal Kesihatan Masyarakat (Malaysia). 2006;12(1):1–10.

Teshale G, Debie A, Dellie E, Gebremedhin T. Evaluation of the outpatient therapeutic program for severe acute malnourished children aged 6–59 months implementation in Dehana District, Northern Ethiopia: a mixed-methods evaluation. BMC pediatrics. 2022;22(1):1–13.

Mason E. WHO’s strategy on Integrated Management of Childhood Illness. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2006;84(8):595.