IELTS Practice.Org

IELTS Practice Tests and Preparation Tips

- Sample Essays

IELTS sample essay: people now spend a lot of money on their wedding

by Manjusha Nambiar · Published April 23, 2012 · Updated October 21, 2012

Nowadays, people are spending increasingly large amounts of money on their marriage parties. Many people feel large and expensive weddings cause problems for the bride and groom. Do you agree? Use personal examples in your response.

This question was asked on an IELTS writing test held in Dubai on March 2012. It is taken from www.ieltsielts.com

Lavish wedding parties are the norm in many parts of the world. For example, in India parents don’t mind spending large amounts of their hard earned money on their children’s wedding. In fact, Indian parents start planning and saving for their daughter’s wedding from the day she is born.

In the Middle East, where arranged marriages are common, the cost of wedding is borne by the entire family. In the west, where arranged marriages are uncommon, the bride and the groom bear the cost of wedding. In any case, insane amounts of money are being spent on weddings. Expensive weddings cause problems not only for the bride and the groom but also for their families. Does that mean every marrying couple should opt for simple wedding ceremonies? Well, let’s see.

There is no denying the fact that a wedding is an occasion to celebrate. After all, it happens just once in a lifetime. The problem arises when people opt for weddings that they cannot afford. Spending borrowed money on a wedding is definitely not a wise idea. It will unnecessarily put a financial burden of the new couple even before they start their life together. Worse still, in India where dowry is a huge social problem many parents don’t prefer having a girl child because they cannot afford to pay huge amounts of dowry. In worst cases, it even leads to female infanticide. Parents abort a girl child even before she is born because they don’t want to spend millions of money on her wedding when she grows up.

After analyzing the situation, it is not hard to see that lavish weddings do more harm than good. While marrying couples should be allowed to choose the kind of wedding they should have, they should be under no compulsion to throw lavish parties that they cannot afford.

Tags: ielts essay ielts essay writing ielts model essay ielts sample essay ielts writing sample ielts essays

Manjusha Nambiar

Hi, I'm Manjusha. This is my blog where I give IELTS preparation tips.

- Next story IELTS letter writing: how to write an informal letter?

- Previous story IELTS gap fills essay

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- Academic Writing Task 1

- Agree Or Disagree

- Band 7 essay samples

- Band 8 Essay Samples

- Band 8 letter samples

- Band 9 IELTS Essays

- Discuss Both Views

- Grammar exercises

- IELTS Writing

- Learn English

- OET Letters

- Sample Letters

- Writing Tips

Enter your email address:

Delivered by FeedBurner

IELTS Practice

IELTS BAND7

Best coaching Tel:8439000086

Dehradun: 8439000086

Writing Task 2: Spending money on weddings.

Writing task 2.

You should spend 40 minutes on this task.

Write about the following topic:

Some people spend a lot of money for their wedding ceremonies. However, others feel like it is unnecessary to spend a lot.

Discuss both view points and give your own opinion..

Give reasons for your answer and include any relevant example from your own knowledge or experience.

Sample Answer

A weddings signifies the culture and traditions of a country. In the past few years, the wedding industry has marked a remarkable growth worldwide. Certainly, a wedding is not an unvoiced affair, but a magniloquent event. Some people believe that spending freely and lavishly on weddings is acceptable whereas, others think that it is not required at all. I will discuss about both the views in my essay.

On one hand, Indian weddings have a great contribution in generating employment. As wedding industry requires the services of other segments also like hospitality, catering, apparels, decoration and makeup etc. Additionally, an expansion of wedding industry indicates a substantial growth in other service sectors as well. What is more, marriage is once in a lifetime event. Therefore, people spend lavishly to make it a special and memorable moment. These weddings bring all family members, friends and relatives at one place. So, they get an opportunity to spend some quality time together with lots of fun and enjoyment.

On the other hand, predominantly, a tradition of grand marriages puts a burden on the people who are not affluent financially. People not only spend their lifelong savings on these weddings but also borrow lofty loans just to impress the society. In addition, varieties of cuisines are prepared and served to the guests. Many times a large portion of food remains unconsumed and is wasted eventually. This money can otherwise be invested and utilised for other productive endeavours.

To conclude, wedding is the most pious and auspicious ceremony in our life. It has lately become a subject of reputation and pride. In my opinion, in spite of spending money carelessly on these magnificent weddings, tying a knot should be a simple and private affair.

IELTS Dehradun Uttarakhand Tel: 8439000086 , 8439000087

- Discuss Both Views

- IELTS Essay Type

- IELTS preparation

WhatsApp us

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

How to Survive a Lavish Wedding

By Jen Doll

- July 20, 2017

Like many a human who has reached a certain age, I’ve spent a lot of my adult life going to weddings.

They’ve ranged from a beach in the Dominican Republic to City Hall to the traditionally formal evening event, complete with passed canapés, ice sculptures and sequined gowns. Before one of those ornate affairs, my date arrived clad in black jeans to pick me up. I spent most of the night feeling self-conscious that I’d brought along a guy who was less dressed up than the kitchen staff.

As I would eventually learn, one of the key ways to survive a lavish wedding is to let the embarrassing moments slide off you like good caviar. Don’t keep apologizing to people. It only draws attention to the gaffe, and anyway, the sartorial choices of you and your date aren’t the point of the wedding.

Start With the Invite

“We’re fortunate, we live in an information age, so anything you need to know is relatively easy to find out,” said Daniel Post Senning, a co-host of the Awesome Etiquette podcast and the great-great grandson of the famed etiquette author Emily Post. “The invitation is designed to tell you a lot. Is there a reception? Is there a reply card included? What’s the formality? Once upon a time invitations featured coded language: For instance, requesting ‘the honor of your presence’ versus ‘the favor of your company’ told you whether it would be held in a place of worship versus a home,” he said. “Or the use of the word ‘and’ versus the word ‘to,’ that is, “the marriage of someone and someone versus someone to someone.” The first indicates a Jewish wedding; the second a Christian one.

Know What to Wear

The invitation will also help you get dressed, said Shawn Rabideau, a wedding planning expert, of Shawn Rabideau Events & Design . First, check the dress code; it should appear in the lower-right corner of the invite or on a reception card.

“White tie is fancier than black tie; it’s a black tailcoat over a white starched shirt for men,” he explained. “A woman could get away with a beautiful ball gown for either.” If the wedding is indoors and after 6:30 p.m., it’s a fair bet that it’s black tie. If it’s an outdoor wedding, “Chances are you’ll be in the grass,” Mr. Rabideau noted. “Ladies, wear your heel protectors.” An outdoor wedding lends a little leeway in terms of attire: A linen or lighter-weight suit for men can be appropriate, and people might experiment with hat size a bit more, Mr. Post Senning said.

“If you’re friends with the family, ask what their colors are,” Mr. Rabideau instructed. A no-no would be matching the wedding party. “And don’t wear something too revealing. If you’re questioning, ‘Is this too much?’ then it probably is. If you find something elegant that fits the black-tie bill and you have nice shoes that are comfortable, you will fit in. You don’t need to spend thousands.”

Have Fun With Fancy

“A concept that I love is that when things get really formal, they sometimes get a little playful,” Mr. Post Senning told me. “The most formal shoes you can pair with a tux are velvet slippers.” Or consider the increasingly ornate and occasionally kooky hats seen on women at British royal weddings. “There’s a certain casual comfort and familiarity at the extremes of formality that are easy to forget about,” he said. “To have fun in that and play is part of enjoying it.”

When in Doubt, Ask

Anne Szustek, who has attended more than a dozen “white-tie optional” weddings, recommended asking “the person doing the inviting — the couple or the person bringing you as a plus-one — to get an idea and follow their lead” in terms of what to wear. (It’s totally fine to ask this and other questions of formality, Mr. Post Senning said.)

Ms. Szustek added that looking at wedding-focused media that center on the high end of things can be instructive. “Town & Country’s wedding section is the gold standard on this front,” Ms. Szustek said, referring to the lifestyle magazine.

“You can always call with a clarifying question about attire. Or food, especially if you have an allergy. The sooner the better,” Mr. Post Senning said. “You might say: ‘My spouse and I have dietary restrictions. Would it be O.K. if I spoke to your planner about that?’” Mr. Rabideau suggested. “Then it doesn’t become the bride’s problem.”

Pay Attention to the Couple, and Their Parents

It’s only polite, but there’s strategy to it.

“We went to a wedding in the English countryside, and the hat etiquette is that the mother of the bride dictates when all the ladies are able to remove their hats,” said Claire Mickelborough, an American who lived in London for nine years. “Two girls at my table took their hats off, and they were tapped on the shoulder by said mother of bride and told to put them back on until she chose when the time was right.”

Mortifying, and completely avoidable.

“If the bride and the mother of the bride are taking their shoes off, it’s O.K. for you to do the same,” Mr. Rabideau said. “If the groom or father of the bride takes their jacket off or loosens their tie, you can do so as well. Until that happens, you have to suck it up.”

Don’t Freak About Money

Mr. Post Senning advises guests to “know what your budget is and stick with it” with regard to the wedding you’re attending. Don’t spend more than you can comfortably afford on travel, gifts, attire and so on. (The same goes for the couple throwing the party.) He also enthusiastically debunked the idea that a gift should be the equivalent of the dinner you’re served. “It’s not an exchange,” he said. Nor should you compare yourself with others and what they might give. “It’s the thought that counts,” he said. “It’s about the relationship and wanting to reciprocate.”

Do bring a gift, however — that’s customary. “ Everybody has different budgets and price points,” Mr. Rabideau added. “If you are a guest, don’t feel the pressure to purchase the most lavish gift. Purchase something that will be memorable.”

Remember the Etiquette Basics

Mr. Post Senning laid out a few “minimums for no matter the wedding” for guests: R.S.V.P. in a timely manner with enough information. (Some indication of the form the reply should take should be part of the invitation.) Having accepted, show up on time: “Five to 10 minutes is great, 20 for a cushion, but you don’t want to become a burden and show up too early.” Then, “be prepared to enjoy yourself. It’s not enough to just drag your carcass there.”

From that, act like the gentle human you are. “One faux pas as a guest is walking up to anyone who is hosting and saying, ‘Wow, this must have cost you a lot of money.’ I’ve heard people say this!” Mr. Rabideau said. “If the food doesn’t come out exactly to your liking, if the coffee service isn’t fast enough, if the room is too cold or hot, keep your mouth shut.”

In that vein, don’t go around taking a ton of selfies. Do spend time observing everyone else and your surroundings. Don’t upstage the bride and groom. Don’t wear white. If celebrities are there, don’t ask for autographs. Do work from the outside in with your silverware. Above all, remember that you’re not the focus, and you should be fine.

Enjoy Yourself

In 2015, Jennifer Wright wrote an article for Town & Country about attending the wedding of her friend Katalina Sharkey De Solis to Ashley Hicks, Prince Philip’s godson. The event was held at the couple’s country estate and featured guests like Christian Louboutin and Giles Deacon. Lavish, sure, but “in a lot of ways it was also just the most laid-back wedding I’ve ever been to,” Ms. Wright told me. “I don’t recall there even being a dress code, except the kind you might be inclined to impose on yourself if you know Vogue staffers are showing up. They served pizza from a tent out back. It could have been in someone’s backyard, except it was on an estate.” It was also “the most fun wedding I’ve ever been to,” she said.

Lavish doesn’t have to mean old-school, black-tie events at New York institutions, with caviar ladled out with gold spoons by men in white. It doesn’t have to mean scary, either. And, really, you can take heart in the fact that there simply aren’t that many of them.

“The lavish weddings are probably 1 to 2 percent of the weddings that take place,” Mr. Rabideau said. If you’re invited to one, “pinch yourself,” Mr. Post Senning said. “Enjoy a Champagne that’s expensive, try the caviar, enjoy the views and the experience. It can be a real treat.”

Update July 27, 2017:

An earlier version of this article included a quotation from a wedding planning expert that referred incorrectly to attire at white-tie weddings. While it can include a white jacket in some regions, the more common attire would include a black tailcoat over a white starched shirt.

Jen Doll is the author of “Save the Date: The Occasional Mortifications of a Serial Wedding Guest.”

Weddings Trends and Ideas

Keeping Friendships Intact: The soon-to-be-married couple and their closest friends might experience stress and even tension leading up to their nuptials. Here’s how to avoid a friendship breakup .

‘Edible Haute Couture’: Bastien Blanc-Tailleur, a luxury cake designer based in Paris, creates opulent confections for high-profile clients , including European royalty and American socialites.

Reinventing a Mexican Tradition: Mariachi, a soundtrack for celebration in Mexico, offers a way for couples to honor their heritage at their weddings.

Something Thrifted: Focused on recycled clothing , some brides are finding their wedding attire on vintage sites and at resale stores.

Brand Your Love Story: Some couples are going above and beyond to personalize their weddings, with bespoke party favors and custom experiences for guests .

Going to Great Lengths : Mega wedding cakes are momentous for reasons beyond their size — they are part of an emerging trend of extremely long cakes .

Essay Papers Writing Online

How to master the art of writing a successful cause and effect essay that captivates your readers and earns you top grades.

Are you intrigued by the interconnected nature of events and phenomena? Do you aspire to unravel the hidden threads that link causes to effects? Crafting a cause and outcome essay provides an excellent platform to explore and dissect these connections, allowing you to showcase your analytical skills and express your ideas with precision and clarity.

In this comprehensive guide, we will delve deep into the art of writing cause and outcome essays, equipping you with effective strategies, invaluable tips, and real-life examples that will help you master the craft. Whether you are a seasoned writer looking to enhance your skills or a beginner eager to embark on a new writing journey, this guide has got you covered.

Throughout this journey, we will navigate the intricate realm of cause and outcome relationships, examining how actions, events, and circumstances influence one another. We will explore the essential elements of a cause and outcome essay, honing in on the importance of a strong thesis statement, logical organization, and compelling evidence. By the end of this guide, you will possess the necessary tools to produce a captivating cause and outcome essay that engages your readers and leaves a lasting impact.

Tips for Writing a Cause and Effect Essay

When composing a paper that focuses on exploring the connections between actions and their consequences, there are several essential tips that can help you write a compelling cause and effect essay. By following these guidelines, you can ensure that your essay is well-structured, clear, and effectively communicates your ideas.

By following these tips, you can enhance your ability to write a compelling cause and effect essay. Remember to analyze the causes and effects carefully, organize your ideas effectively, provide clear explanations, use transitional words, and proofread your essay to ensure a polished final piece of writing.

Understand the Purpose and Structure

One of the most important aspects of writing a cause and effect essay is understanding its purpose and structure. By understanding these key elements, you can effectively communicate the relationship between causes and effects, and present your argument in a clear and organized manner.

In a cause and effect essay, the purpose is to analyze the causes of a specific event or phenomenon and explain the effects that result from those causes. This type of essay is often used to explore the connections between different factors and to demonstrate how one event leads to another.

To structure your cause and effect essay, consider using a chronological or sequential order. Start by introducing the topic and providing some background information on the causes you will discuss. Then, present your thesis statement, which should clearly state your main argument or claim.

In the body paragraphs, discuss each cause or group of causes in a separate paragraph. Provide detailed explanations, examples, and evidence to support your claims. Make sure to use transitional words and phrases to guide the reader through your essay and to show the logical progression of causes and effects.

Finally, in the conclusion, summarize your main points and restate your thesis, reinforcing your overall argument. You can also discuss the broader implications of your analysis and suggest possible solutions or further research.

By understanding the purpose and structure of a cause and effect essay, you can effectively convey your ideas and arguments to your readers. This will help them follow your reasoning and see the connections between causes and effects, leading to a more convincing and impactful essay.

Choose a Topic

When embarking on the journey of writing a cause and effect essay, one of the first steps is to choose an engaging and relevant topic. The topic sets the foundation for the entire essay, determining the direction and scope of the content.

To select an effective topic, it is important to consider your interests, as well as the interests of your intended audience. Think about subjects that captivate you and inspire curiosity. Consider current events, personal experiences, or areas of study that pique your interest. By choosing a topic that you are genuinely passionate about, you will be more motivated to conduct thorough research and present compelling arguments.

Additionally, it is essential to select a topic that is relevant and meaningful. Identify an issue or phenomenon that has a clear cause-and-effect relationship, allowing you to explore the connections and consequences in depth. Look for topics that are timely and impactful, as this will ensure that your essay resonates with readers and addresses significant issues in society.

Moreover, a well-chosen topic should have enough depth and breadth to support a comprehensive analysis. Avoid selecting topics that are too broad or shallow, as this can make it challenging to delve into the causes and effects in a meaningful way. Narrow down your focus to a specific aspect or aspect of a broader topic to ensure that you have enough material to explore and analyze.

In conclusion, choosing a topic for your cause and effect essay is a critical step that will shape the entire writing process. By selecting a topic that aligns with your interests, is relevant and meaningful, and has enough depth and breadth, you will lay the foundation for a compelling and informative essay.

Conduct Thorough Research

Before diving into writing a cause and effect essay, it is essential to conduct a comprehensive research on the topic of your choice. This research phase will provide you with the necessary background information and context to develop a strong and well-supported essay.

During the research process, explore various sources such as books, academic journals, reputable websites, and credible news articles. Utilize synonyms for “research” like “investigate” or “explore” to keep your writing engaging and varied.

Avoid relying solely on a single source or biased information. Instead, strive to gather a variety of perspectives and data points that will enhance the credibility and validity of your essay.

Take notes as you research, highlighting key points, statistics, and quotes that you may want to include in your essay. Organize your findings in a clear and structured manner, making it easier to refer back to them as you begin writing.

Incorporating well-researched evidence and supporting examples into your cause and effect essay will lend credibility to your arguments, making them more persuasive and convincing. By conducting thorough research, you will be able to present a well-rounded and informed analysis of the topic you are writing about.

Create an Outline

One of the crucial steps in writing any type of essay, including cause and effect essays, is creating an outline. An outline helps to organize your thoughts and ideas before you start writing, ensuring that your essay has a clear and logical structure. In this section, we will discuss the importance of creating an outline and provide some tips on how to create an effective outline for your cause and effect essay.

When creating an outline, it is important to start with a clear understanding of the purpose and main points of your essay. Begin by identifying the main cause or event that you will be discussing, as well as its effects or consequences. This will serve as the foundation for your outline, allowing you to structure your essay in a logical and coherent manner.

Once you have identified the main cause and effects, it is time to organize your ideas into a clear and logical order. One effective way to do this is by using a table. Create a table with two columns, one for the cause and one for the effect. Then, list the main causes and effects in each column, using bullet points or short phrases. This will help you see the connections between the different causes and effects, making it easier to write your essay.

In addition to listing the main causes and effects, it is also important to include supporting details and examples in your outline. These can help to strengthen your argument and provide evidence for your claims. Include specific examples, facts, and statistics that support each cause and effect, and organize them under the relevant point in your outline.

Lastly, make sure to review and revise your outline before you start writing your essay. Check for any gaps in your logic or missing information, and make any necessary adjustments. Your outline should serve as a roadmap for your essay, guiding you through the writing process and ensuring that your essay is well-structured and coherent.

In conclusion, creating an outline is an essential step in writing a cause and effect essay. It helps to organize your thoughts and ideas, ensuring that your essay has a clear and logical structure. By identifying the main cause and effects, organizing your ideas into a table, including supporting details and examples, and reviewing your outline, you can create an effective outline that will guide you through the writing process.

Develop the Body Paragraphs

Once you have identified the main causes and effects of the topic you are writing about, it is time to develop your body paragraphs. In these paragraphs, you will present specific evidence and examples to support your claims. The body of your essay should be well-structured and focused, with each paragraph addressing a single cause or effect.

Start each body paragraph with a topic sentence that clearly states the main point you will be discussing. Then, provide detailed explanations and evidence to support your argument. This can include statistics, research findings, expert opinions, or personal anecdotes. Remember to use clear and concise language to convey your ideas effectively.

In order to make your writing more coherent, you can use transition words and phrases to connect your ideas and create a logical flow between paragraphs. Words like “because”, “as a result”, “therefore”, and “consequently” can be used to show cause and effect relationships.

Additionally, it is important to use paragraph unity, which means that each paragraph should focus on a single cause or effect. Avoid including unrelated information or discussing multiple causes/effects in a single paragraph, as this can confuse the reader and weaken your argument.

Furthermore, consider using examples and evidence to enhance the clarity and persuasiveness of your arguments. Concrete examples and real-life scenarios can help illustrate the cause and effect relationship and make your writing more engaging to the reader.

- Use accurate data and precise details to back up your claims

- Include relevant research and studies to support your arguments

- Provide real-life examples and cases that demonstrate the cause and effect relationship

In conclusion, developing the body paragraphs of your cause and effect essay is crucial in presenting a well-structured and persuasive argument. By using topic sentences, clear explanations, transition words, and relevant evidence, you can effectively convey your ideas and convince the reader of the cause and effect relationship you are discussing.

Related Post

How to master the art of writing expository essays and captivate your audience, convenient and reliable source to purchase college essays online, step-by-step guide to crafting a powerful literary analysis essay, tips and techniques for crafting compelling narrative essays.

The financial burden of weddings on India’s poorest families

A culture of extravagance and exploitative practices force brides’ families to spend beyond their means – but change could be under way.

New Delhi, India – New Delhi-based schoolteacher Sunita Sharma was very excited about her wedding in November 2019 to her neighbour, an electrician. The 26-year-old had saved up $2,000 from her monthly salary of $200 for the wedding expenses.

But that was not enough. Her mother also had to sell off the family’s small piece of land to buy her only daughter a trousseau – furniture, a television and a refrigerator. The rest of the money went into booking a small wedding hall, hiring a local music band and catering for a party of 200 guests.

Keep reading

In pictures: kashmir’s elaborate weddings muted by covid-19, coronavirus: how an indian wedding and funeral infected 100, india police stop interfaith marriage citing ‘love jihad’ law, two weddings, somali style.

However, a last-minute demand from her fiancé’s father sent the Sharmas into a panic. He wanted his son to be given a car as well. Sunita pleaded that a car would be out of their budget as they had already exhausted all their funds. Besides, her father had died when she was 19 and so, as the oldest of four, she had worked very hard to feed her family.

But the groom’s family would have none of it. “My fiancé said that if the wedding was to be formalised, the car’s precondition would have to be met. Ultimately, the wedding was called off,” says Sunita.

Though she has since married and moved on, Sharma’s harrowing experience mirrors that of millions of Indians, and it is a plight that affects poor and lower-middle-class families most severely.

The Indian wedding – colourful and cacophonous – is an occasion often marked by hundreds, if not thousands, of guests, lavish banquets and venues and brides and grooms kitted out in eye-popping costumes and jewellery. Some 10 million weddings take place each year in a market worth $50bn. But the occasion also puts enormous social pressure on the bride’s family to spend vast sums of money in order to fulfil the demands of the groom’s family and impress relatives.

Failure to do so can have ramifications. The marriage may be called off, or the family may end up borrowing from informal moneylenders, a common practice as many in India still rely on cash and not bank transactions . These loans can come at an astronomical interest rate, indebting the family for life. Weddings that have been called off have driven brides and their parents to commit suicide due to fear of social opprobrium. Harassment over dowry – money and other goods demanded by the groom’s family – a practice that is officially illegal but still continues, can lead to deaths and suicides.

The weddings of the wealthy, the trappings of social tradition and the entrenched practice of dowry put immense pressure on lower-middle-class and poor families. But some social initiatives are hoping to change that.

A culture of extravagance

The high-profile nuptials of the rich and famous set impossibly high standards for the middle classes and the poor to emulate, triggering unnecessary social pressures, according to Dr Ranjana Kumari, director of the Center for Social Research, a New Delhi-based think-tank.

In 2018, the wedding of Isha Ambani, the daughter of Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest man, cost a rumoured $100m. The multiple-destination celebration starring guests like Hillary Clinton and Beyonce dominated national news for days.

The five-day 2016 nuptials of the daughter of mining baron and politician Gali Janardhana Reddy at an estimated cost of $74m had gold-plated invitation cards, 50,000 guests and samba dancers flown in from Brazil. In 2004, for the $60m, week-long marriage of steel tycoon Lakshmi Mittal’s daughter Vanisha to London-based investment banker Amit Bhatia, about 1,000 guests, including Bollywood stars, were flown to France. The festivities included an Eiffel Tower fireworks display and a private show by Kylie Minogue.

Such extravagance, according to Kumari, seems especially misplaced in a country where millions of people go hungry. India ranks 94th out of the 107 assessed countries on the 2020 Global Hunger Index with a level of hunger that is categorised as “serious”. According to the Index, 14 percent of Indians are undernourished and 34.7 percent of children under the age of five are stunted.

High wedding expenditure also seems incongruous in a country ridden with glaring societal inequities. Today, the wealthiest 1 percent hold four times the wealth held by the poorest 70 percent of the population, or 953 million people, according to an Oxfam report.

In recent years, lawmakers have tried to curb excessive wedding spending and the pressure this places on underprivileged families.

In 2017, the Marriages (Compulsory Registration and Prevention of Wasteful Expenditure) Bill was introduced in parliament, proposing that families who spend more than 5 lakh (about US$7,000) on a wedding must donate 10 percent of the overall cost of the weddings to brides from poor families.

Bollywood’s influence

In an iniquitous social setting such as India’s, the role of Bollywood or the Hindi film industry in creating pressure to overspend on weddings cannot be ignored, say observers. “In Indian movies, wedding functions are highly glamourised events with fancy attires, and song and dance sequences in scenic locales. As cinema has a powerful hold over the mind of the masses, such depiction creates an aspiration among all classes of youth to mimic such splendour at their own weddings too,” says Kumari.

The proliferation of international global fashion chains in second and third-tier Indian cities is further creating newer avenues for consumption at weddings among all classes, say some.

“Everybody is into designer merchandise these days,” says Pratibha Chahal, a Mumbai-based sociologist. “Add to it the trend of hiring wedding planners, stylists, florists and multiple vendors for weddings and you have a toxic cocktail which has added so many unwanted layers to an Indian wedding today. All this expense pushes up cost dramatically.”

This level of consumption was not prevalent earlier, says Chalal, referring to the decades prior to the 1970s, which is when weddings started to evolve. Back then, weddings were largely family affairs and everyone pitched in to cook, decorate the house and handle all functions themselves, she says.

“Indian weddings are more about showing off one’s wealth and status and not really about the institution,” says Veena Trikha, 55, a schoolteacher whose son married last year. “It puts middle-class families under tremendous social pressure to spend more, perpetuating a culture of overconsumption. The perception of what society thinks about us always drives our thinking.”

An obsession with gold ornaments, also considered auspicious, is another factor contributing to overspending. “Indians are known to mortgage properties, take as many personal loans as they can afford or beg and borrow just to ensure that there’s enough display of gold at a wedding. In certain regions, people explicitly demand gold as dowry in the name of ancestral tradition. Even the poorest of parents will try to give at least one gold chain to their daughter to save face,” adds Kumari.

Unsurprisingly, India is the world’s second-largest consumer of gold, buying nearly 700 tonnes in 2019. More than half of this demand can be attributed to bridal jewellery, according to Chahal.

‘Girls are reduced to all about being married off’

Beyond the influence of unrealistic weddings, one of the grimmest aspects of a culture of overconsumption is the social malaise of the dowry. Dowries can include cash, real estate, cars, jewellery and other material items.

Middle-class and poor families often start planning for their daughter’s marriage from the time she is born.

According to Sunita, whose family faced crippling dowry demands, girls are considered a “curse” for poor families because parents see them as a burden due to the wedding expenses involved in their marriage. “Girls are reduced to all about being married off,” she says. “Her education, her career, her happiness – everything takes a back seat in front of her marriage.”

“Marrying off a daughter is an onerous responsibility in our section of society; there’s nothing joyous about it,” says Rani Devi, 56, a small-hold farmer from Hardoi district of the northern state of Uttar Pradesh whose daughter Shanti, 21, was recently married to a man from a neighbouring village.

Devi says that as her son-in-law had a bachelor’s degree, his family demanded a motorcycle and a gold chain for the groom for which she had to borrow about $1,000 from her relatives.

“As a widow, I requested the boy’s family to settle for a simple ceremony at a local temple, but he refused. His family said it was a matter of social status for them that their only son have an elaborate wedding. We had to pay for all the groom’s wedding arrangements too,” she says.

As girls are often seen as a financial liability, wedding expenses related to their nuptials could also be one of the reasons for the country’s skewed sex ratio, say experts.

India’s current gender ratio (112 males/100 females) is driven by a parental preference for sons that leads to sex-selective abortion practices and gender imbalances, according to Delhi-based obstetrician and gynaecologist Dr Samriddhi Kakkar.

“The son is seen as an investment in the future; as someone who will take care of old parents, unlike daughters who marry and leave the home. So a premium is placed on the son’s birth. As dowry is invariably involved in a daughter’s wedding, she is seen as a liability,” says Kakkar.

“In India, men have a rate card,” explains New Delhi-based civil rights layer Shashikala Kandhari.

“Those with better education or secure government jobs have greater brand value in the matrimonial market. And that worth is assessed by the amount of dowry – in cash or kind – they will get upon marriage from the bride’s family. In India’s patriarchal society, men have always been valued over women and the practice of dowry is an offshoot of that retrogressive mindset,” says Kandhari.

Dowry exploitation

Despite economic progress, this heinous custom of dowry still flourishes in India across all levels of society, making women vulnerable to exploitation and abuse.

According to Kandhari, the practice exists despite comprehensive legal provisions. Under the Dowry Prohibition Act of 1961, both giving and accepting dowry in India is an offence and the punishment for violating it is at least five years of imprisonment, and a fine of either $200 or the value of the dowry given, whichever is higher.

According to the National Crime Records Bureau, every hour an Indian woman is driven to suicide or is murdered over dowry. Every four minutes, a woman faces cruelty from her in-laws or husband. In December last year, a 27-year-old woman set her house on fire and then jumped into the blaze with her two sons in a village in the state of Rajasthan. She was allegedly harassed for dowry by her husband and his family.

In another case reported in Bengaluru in early 2020, a husband demanded cash a few weeks after marriage despite receiving a kilogramme of gold in dowry as per his demands. When his wife refused, he burned her alive.

“In 1983, Sections 304B and 498A of the Indian Penal Code were also enacted to prohibit cruelty by husband or his relatives towards a woman,” says Kandhari, the lawyer. These sections are intended to help women seek redressal for cruelty and harassment. In the case of a woman’s death, prison sentences can be extended for life.

However, due to poor implementation of the law, most dowry cases take years to be resolved. Backlogs in courts and a lack of solid evidence to prove that dowry was demanded means the perpetrators are rarely convicted, according to Kandhari. Between 2006 and 2016, only one of every seven cases ended in a conviction, with five resulting in an acquittal and one being withdrawn, according to the National Crime Records Bureau.

Debt bondage

According to research by Pragati Gramodyog Evam Samaj Kalyan Sansthan (PGS), a pan-India non-profit that focuses on the intergenerational slavery of marginalised communities, more than 60 percent of Indian families turn to money lenders to borrow funds for wedding ceremonies.

“We have come across hundreds of cases in our fieldwork where marriage expenses have pushed poor families to slavery,” says Subedar Singh, media coordinator at PGS. “Loans to cover wedding costs come with impossibly high interest rates, causing many families to fall into bondage to pay off the debt. Indebtedness in rural India is very high due to high expenditure on two social occasions – wedding and death ceremonies. The culture (of expensive ceremonies) is so entrenched in rural communities that it makes thousands of poor fall into debt bondage.”

PGS cofounder Jyoti Singh, whose late husband Sunit Singh launched the organisation in 1986, says that with social pressures at work, even the poorest families have to stretch themselves financially to organise weddings that are beyond their means.

“If they don’t, fingers are pointed at them. Some are even ostracised or their daughters tortured till the parents capitulate to the groom’s demands. In some Indian villages, the groom’s family typically asks the bride’s family to cover the entire cost of the wedding in addition to giving cash or other gifts. Lack of education, poverty, and patriarchy exacerbate these pressures,” adds the activist.

Singh adds that as many poor Indians do not have bank accounts, or often do not use them, they invariably turn to upper-caste moneylenders when they require large sums of money for their weddings. “They are rarely able to repay these debts because moneylenders impose annual interest rates of over 100 percent. As a result, poor families are often forced to become bonded labourers, slaving up to 18 hours in brick kilns, rice mills, construction sites, mines or steel factories,” she adds.

Law enforcement is virtually non-existent due to a thriving landowner-police-politician nexus, according to Subedar Singh, which precludes investigations into debt bondage. “When cases actually make their way to court, a judiciary overburdened with a backlog of cases and the ignorance of the poor about the intricacies of law leads to traffickers’ acquittals,” he says.

Winds of change

Notwithstanding the culture of extravagance and the social malaises linked with Indian weddings, change is under way. Civil society organisations and individuals are stepping in to strike at the roots of customs that push families into elaborate weddings.

To combat debt bondage, PGS for the past seven years has organised group weddings for couples whose families are at risk of slavery. The ceremonies are kept simple and guests limited to 50 from each side to prevent the families from accruing crippling debt. “Instead of about $1,000 – the amount a typical wedding in these areas (rural northern India) usually costs – each family only pays only $15 for the ceremony so that they don’t fall into debt. Our network of donors pitch in to help as well,” explains Jyoti Singh.

These events encourage the families to invest any money they have saved in small businesses, buying cattle or sending their children to school, adds the activist, and show others an alternative way for weddings to be done.

Kiku Ram and Rani Kumar, both 26 and farmers in Noida, Uttar Pradesh were married at one such event last year. “I’d never imagined that my wedding would be a happy occasion incurring no financial burden on my parents. Throughout my childhood I was witness to my parents worrying about my marriage expenses. But my community wedding solved all their problems,” says Rani. “I wish every girl in society could marry like this.”

According to Suresh Kumar Goyal, coordinator for Narayan Seva Sansthan, a non-profit that organises mass weddings across India for underprivileged and physically disabled people, such weddings send out the right social message – that marriages ought to be joyous occasions and free of any kind of burden.

Launched in 1985, the non-profit organises two community weddings every year for 51 couples in different parts of the country. “All expenses for the nuptial ceremonies are borne by our organisation and our donors. All these families belong to the lowest rung of society and are financially incapable of formalising their own weddings,” says Goyal.

Kanyadaan India Foundation, another pan-India non-profit, was similarly set up to help poor families marry their daughters off in a dignified way. “We try to support the girl and her family by bearing all expenses of the wedding so that dowry and suicide due to lack of funds for marriages do not happen,” says the organisation’s spokesperson.

#Notobigfatwedding

Individual efforts are also targeting patriarchal and established wedding conventions. Hammad Rahman, CEO of Muslim matrimonial website Nikah Forever, has launched the #Notobigfatwedding campaign to popularise sustainable and minimalist weddings, cautioning people to not overspend.

The campaign has garnered more than a million signatures from the public over the past year. Rahman’s message is particularly pertinent as the coronavirus has forced people across different segments of society to opt for simpler weddings.

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Nikah Forever (@nikahforever)

“We aim to promote this idea among youngsters. This is the ideal time to make people realise that we should reject useless traditions that encourage pompous weddings. It’s great to see people adjusting their wedding expenditure even if it is due to the COVID-19 threat. Our campaign aims to remind the world that weddings are the union of two souls rather than a trade-off between wealth and status,” elaborates Rahman.

Smita Gupta, a wedding planner, has seen people shying away from excessive spending due to the pandemic and believes this pattern could be here to stay. “It is clear that the industry will look very different post-pandemic.”

As the wider wedding culture faces a shift, experts feel that, apart from private initiatives, the government too needs to step in to organise mass sensitisation campaigns that educate the public about the ills of dowry, debt bondage related to marriages and the need to have simple weddings.

Better education can empower women to stand up and challenge illegal practices like dowry while helping men fight the pressures dictating that they conform to such social norms, says Kumari.

“Increasing government transparency regarding the investigation and prosecution of exploitative moneylenders and establishment of fast-track courts that address debt bondage are also critical to strike at the roots of irrelevant social customs that cripple the poor,” says Kandhari.

Cause and Effect Essay Outline: Types, Examples and Writing Tips

20 June, 2020

9 minutes read

Author: Tomas White

This is a complete guide on writing cause and effect essays. Find a link to our essay sample at the end. Let's get started!

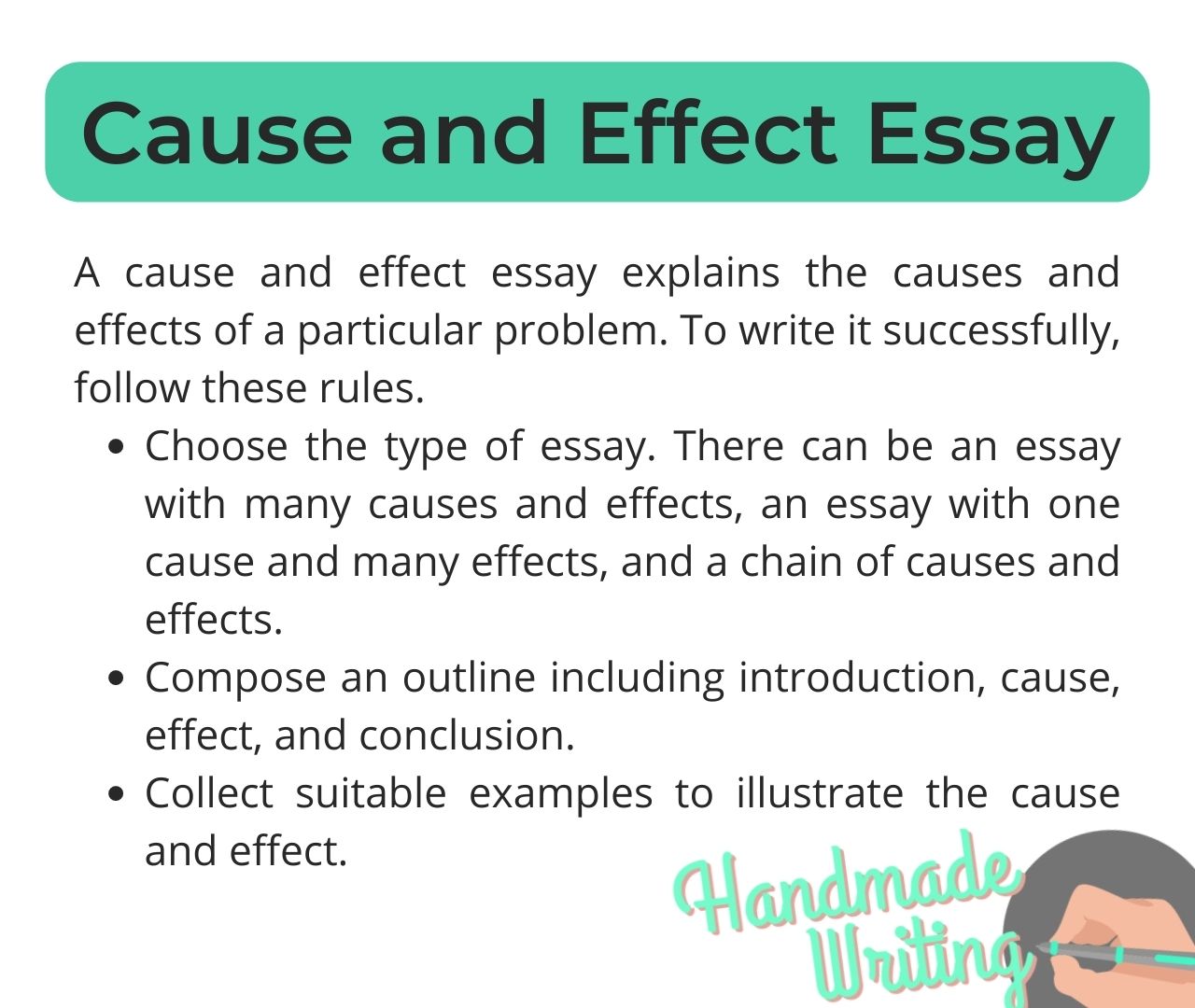

What is a Cause and Effect Essay?

A cause and effect essay is the type of paper that the author is using to analyze the causes and effects of a particular action or event. A curriculum usually includes this type of exercise to test your ability to understand the logic of certain events or actions.

If you can see the logic behind cause and effect in the world around you, you will encounter fewer problems when writing. If not, writing this kind of paper will give you the chance to improve your skillset and your brain’s ability to reason.

“Shallow men believe in luck or in circumstance. Strong men believe in cause and effect.” ― Ralph Waldo Emerson

In this article, the Handmade Writing team will find out how to create an outline for your cause and effect essay – the key to successful essay writing.

Types of the Cause and Effect Essay

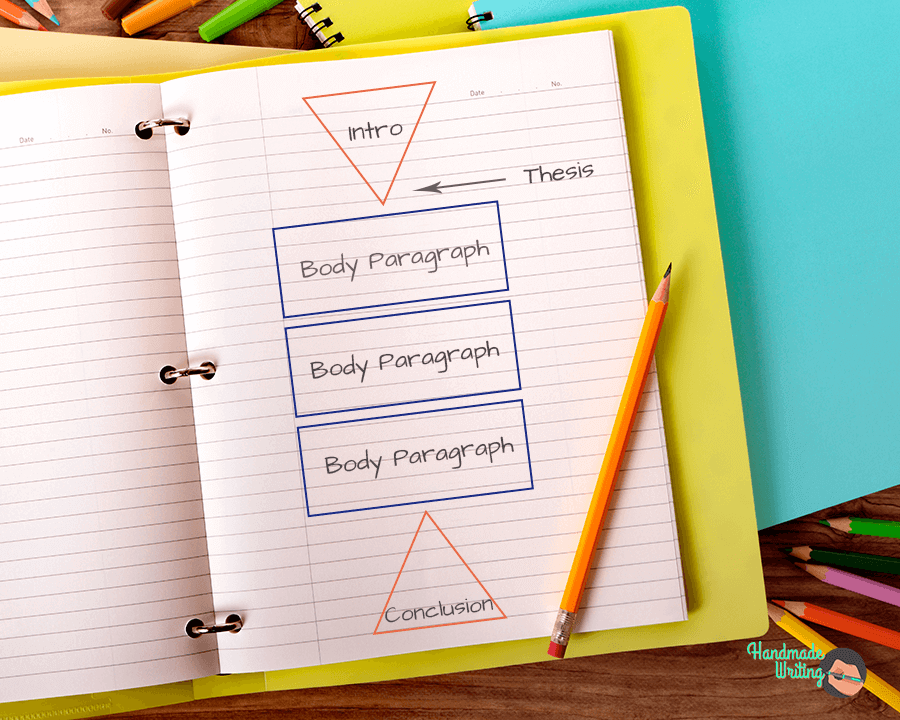

Before writing this kind of essay, you need to draft the structure. A good structure will result in a good paper, so it’s important to have a plan before you start. But remember , there’s no need to reinvent the wheel: just about every type of structure has already been formulated by someone.

If you are still unsure about the definition of an essay, you can take a look at our guide: What is an Essay?

Generally speaking, there are three types of cause and effect essays. We usually differentiate them by the number of and relationships between the different causes and the effects. Let’s take a quick look at these three different cases:

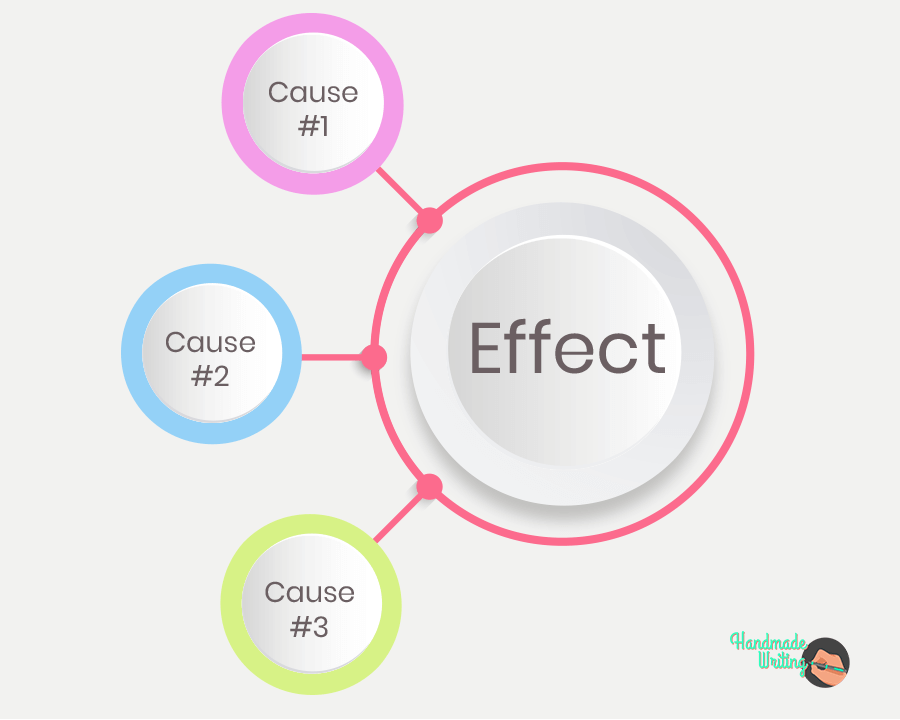

1. Many causes, one effect

This kind of essay illustrates how different causes can lead to one effect. The idea here is to try and examine a variety of causes, preferably ones that come from different fields, and prove how they contributed to a particular effect. If you are writing about World War I, for example, mention the political, cultural, and historical factors that led to the great war.

By examining a range of fundamental causes, you will be able to demonstrate your knowledge about the topic.

Here is how to structure this type of essay:

- Introduction

- Cause #3 (and so on…)

- The effect of the causes

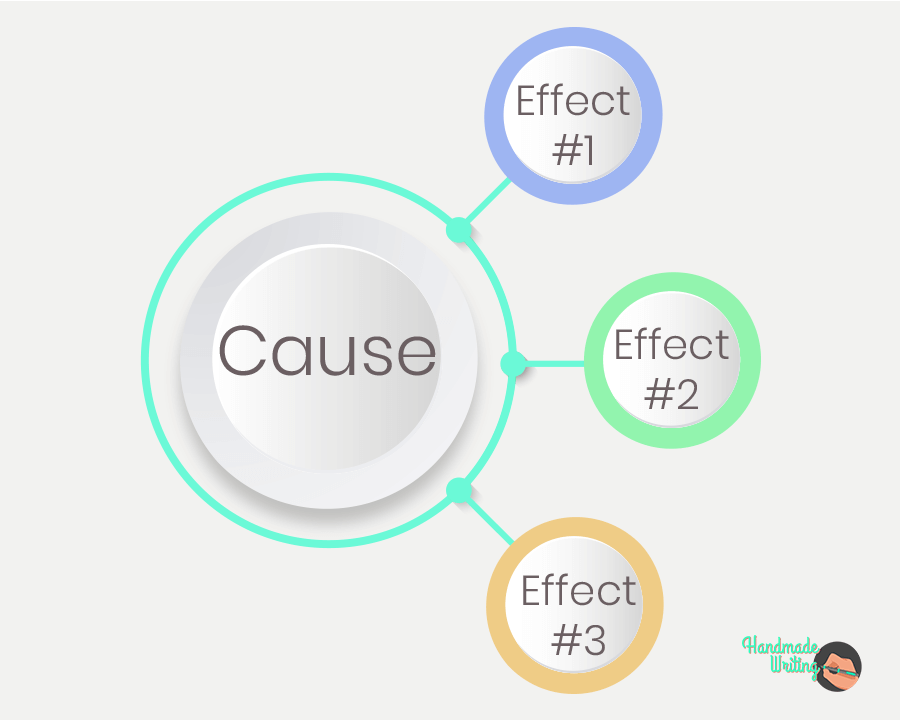

2. One cause, many effects

This type of cause and effect essay is constructed to show the various effects of a particular event, problem, or decision. Once again, you will have to demonstrate your comprehensive knowledge and analytical mastery of the field. There is no need to persuade the reader or present your argument . When writing this kind of essay, in-depth knowledge of the problem or event’s roots will be of great benefit. If you know why it happened, it will be much easier to write about its effects.

Here is the structure for this kind of essay:

- Effect #3 (and so on…)

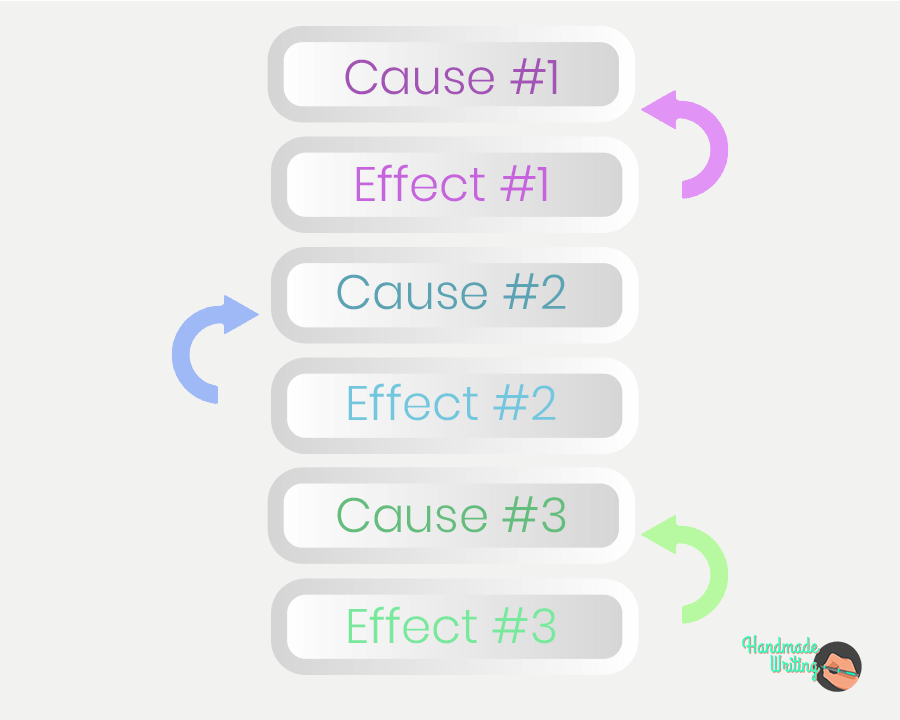

3. Chain of causes and effects

This is the most challenging type. You need to maintain a chain of logic that demonstrates a sequence of actions and consequences, leading to the end of the chain. Although this is usually the most interesting kind of cause and effect essay, it can also be the most difficult to write.

Here is the outline structure:

- Effect #1 = Cause #2

- Effect #2 = Cause #3

- Effect #3 = Cause #4 (and so on…)

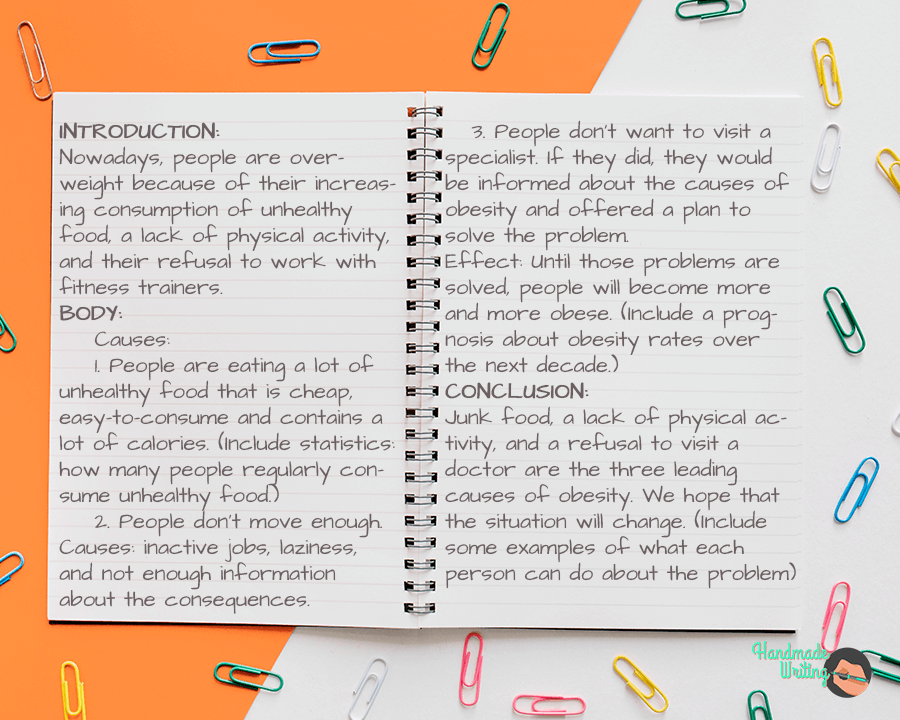

Cause and Effect Essay Outline Example

Let’s take a look at an example. Below, you will find an outline for the topic “The causes of obesity” (Type 1) :

As you can see, we used a blended strategy here. When writing about the ever-increasing consumption of unhealthy food, it is logical to talk about the marketing strategies that encourage people to buy fast food. If you are discussing fitness trainers, it is important to mention that people need to be checked by a doctor more often, etc.

In case you face some issues with writing your Cause and Effect essay, you can always count on our Essay Writers !

How do I start writing once I have drafted the structure?

If you start by structuring each paragraph and collecting suitable examples, the writing process will be much simpler. The final essay might not come up as a classic five paragraph essay – it all depends on the cause-effect chain and the number of statements of your essay.

In the Introduction, try to give the reader a general idea of what the cause and effect essay will contain. For an experienced reader, a thesis statement will be an indication that you know what you are writing about. It is also important to emphasize how and why this problem is relevant to modern life. If you ever need to write about the Caribbean crisis, for instance, state that the effects of the Cold War are still apparent in contemporary global politics.

Related Post: How to write an Essay introduction | How to write a Thesis statement

In the Body, provide plenty of details about what causes led to the effects. Once again, if you have already assembled all the causes and effects with their relevant examples when writing your plan, you shouldn’t have any problems. But, there are some things to which you must pay particular attention. To begin with, try to make each paragraph the same length: it looks better visually. Then, try to avoid weak or unconvincing causes. This is a common mistake, and the reader will quickly realize that you are just trying to write enough characters to reach the required word count.

Moreover, you need to make sure that your causes are actually linked to their effects. This is particularly important when you write a “chained” cause and effect essay (type 3) . You need to be able to demonstrate that each cause was actually relevant to the final result. As I mentioned before, writing the Body without preparing a thorough and logical outline is often an omission.

The Conclusion must be a summary of the thesis statement that you proposed in the Introduction. An effective Conclusion means that you have a well-developed understanding of the subject. Notably, writing the Conclusion can be one of the most challenging parts of this kind of project. You typically write the Conclusion once you have finished the Body, but in practice, you will sometimes find that a well-written conclusion will reveal a few mistakes of logic in the body!

Cause and Effect Essay Sample

Be sure to check the sample essay, completed by our writers. Use it as an example to write your own cause and effect essay. Link: Cause and effect essay sample: Advertising ethic issues .

Tips and Common Mistakes from Our Expert Writers

Check out Handmadewriting paper writing Guide to learn more about academic writing!

A life lesson in Romeo and Juliet taught by death

Due to human nature, we draw conclusions only when life gives us a lesson since the experience of others is not so effective and powerful. Therefore, when analyzing and sorting out common problems we face, we may trace a parallel with well-known book characters or real historical figures. Moreover, we often compare our situations with […]

Ethical Research Paper Topics

Writing a research paper on ethics is not an easy task, especially if you do not possess excellent writing skills and do not like to contemplate controversial questions. But an ethics course is obligatory in all higher education institutions, and students have to look for a way out and be creative. When you find an […]

Art Research Paper Topics

Students obtaining degrees in fine art and art & design programs most commonly need to write a paper on art topics. However, this subject is becoming more popular in educational institutions for expanding students’ horizons. Thus, both groups of receivers of education: those who are into arts and those who only get acquainted with art […]

Cause And Effect Essay Guide

Cause And Effect Essay Examples

Best Cause and Effect Essay Examples To Get Inspiration + Simple Tips

People also read

How To Write A Cause and Effect Essay - Outline & Examples

230+ Cause and Effect Essay Topics to Boost Your Academic Writing

How to Create a Cause and Effect Outline - An Easy Guide

You need to write a cause and effect essay for your assignment. Well, where should you start?

Establishing a relationship between causes and effects is no simple task. You need to ensure logical connections between variables with credible evidence.

However, don't get overwhelmed by the sound of it. You can start by reading some great cause and effect essay examples.

In this blog, you can read cause and effect essays to get inspiration and learn how to write them. With these resources, you'll be able to start writing an awesome cause and effect paper.

Let’s dive in!

- 1. What is a Cause and Effect Essay?

- 2. Cause and Effect Essay Examples for Students

- 3. Free Cause and Effect Essay Samples

- 4. Cause and Effect Essay Topics

- 5. Tips For Writing a Good Cause and Effect Essay

What is a Cause and Effect Essay?

A cause and effect essay explores why things happen (causes) and what happens as a result (effects). This type of essay aims to uncover the connections between events, actions, or phenomena. It helps readers understand the reasons behind certain outcomes.

In a cause and effect essay, you typically:

- Identify the Cause: Explain the event or action that initiates a chain of events. This is the "cause."

- Discuss the Effect: Describe the consequences or outcomes resulting from the cause.

- Analyze the Relationship: Clarify how the cause leads to the effect, showing the cause-and-effect link.

Cause and effect essays are common in various academic disciplines. For instance, studies in sciences, history, and the social sciences rely on essential cause and effect questions. For instance, "what are the effects of climate change?", or "what are the causes of poverty?"

Now that you know what a cause and effect is, let’s read some examples.

Cause and Effect Essay Examples for Students

Here is an example of a well-written cause and effect essay on social media. Let’s analyze it in parts to learn why it is good and how you can write an effective essay yourself.

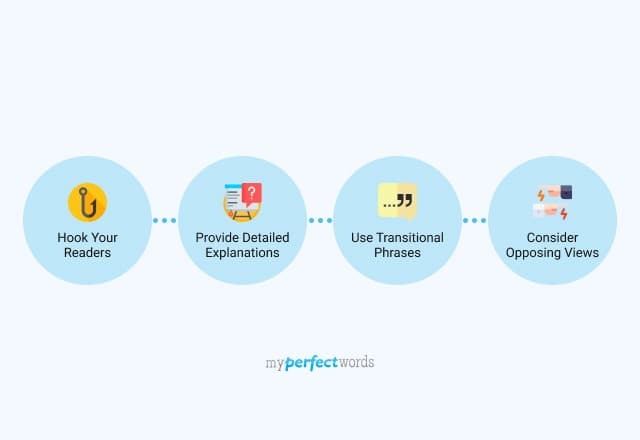

The essay begins with a compelling hook that grabs the reader's attention. It presents a brief overview of the topic clearly and concisely. The introduction covers the issue and ends with a strong thesis statement , stating the essay's main argument – that excessive use of social media can negatively impact mental health.

The first body paragraph sets the stage by discussing the first cause - excessive social media use. It provides data and statistics to support the claim, which makes the argument more compelling. The analysis highlights the addictive nature of social media and its impact on users. This clear and evidence-based explanation prepares the reader for the cause-and-effect relationship to be discussed.

The second body paragraph effectively explores the effect of excessive social media use, which is increased anxiety and depression. It provides a clear cause-and-effect relationship, with studies backing the claims. The paragraph is well-structured and uses relatable examples, making the argument more persuasive.

The third body paragraph effectively introduces the second cause, which is social comparison and FOMO. It explains the concept clearly and provides relatable examples. It points out the relevance of this cause in the context of social media's impact on mental health, preparing the reader for the subsequent effect to be discussed.

The fourth body paragraph effectively explores the second effect of social comparison and FOMO, which is isolation and decreased self-esteem. It provides real-world consequences and uses relatable examples.

The conclusion effectively summarizes the key points discussed in the essay. It restates the thesis statement and offers practical solutions, demonstrating a well-rounded understanding of the topic. The analysis emphasizes the significance of the conclusion in leaving the reader with a call to action or reflection on the essay's central theme.

This essay follows this clear cause and effect essay structure to convey the message effectively:

Read our cause and effect essay outline blog to learn more about how to structure your cause and effect essay effectively.

Free Cause and Effect Essay Samples

The analysis of the essay above is a good start to understanding how the paragraphs in a cause and effect essay are structured. You can read and analyze more examples below to improve your understanding.

Cause and Effect Essay Elementary School

Cause and Effect Essay For College Students

Short Cause and Effect Essay Sample

Cause and Effect Essay Example for High School

Cause And Effect Essay IELTS

Bullying Cause and Effect Essay Example

Cause and Effect Essay Smoking

Cause and Effect Essay Topics

Wondering which topic to write your essay on? Here is a list of cause and effect essay topic ideas to help you out.

- The Effects of Social Media on Real Social Networks

- The Causes And Effects of Cyberbullying

- The Causes And Effects of Global Warming

- The Causes And Effects of WW2

- The Causes And Effects of Racism

- The Causes And Effects of Homelessness

- The Causes and Effects of Parental Divorce on Children.

- The Causes and Effects of Drug Addiction

- The Impact of Technology on Education

- The Causes and Consequences of Income Inequality

Need more topics? Check out our list of 150+ cause and effect essay topics to get more interesting ideas.

Tips For Writing a Good Cause and Effect Essay

Reading and following the examples above can help you write a good essay. However, you can make your essay even better by following these tips.

- Choose a Clear and Manageable Topic: Select a topic that you can explore thoroughly within the essay's word limit. A narrowly defined topic will make it easier to establish cause-and-effect relationships.

- Research and Gather Evidence: Gather relevant data, statistics, examples, and expert opinions to support your arguments. Strong evidence enhances the credibility of your essay.

- Outline Your Essay: Create a structured outline that outlines the introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion. This will provide a clear roadmap for your essay and help you present causes and effects clearly and coherently.

- Transitional Phrases: Use transitional words and phrases like "because," "due to," "as a result," "consequently," and "therefore" to connect causes and effects within your sentences and paragraphs.

- Support Each Point: Dedicate a separate paragraph to each cause and effect. Provide in-depth explanations, examples, and evidence for each point.

- Proofread and Edit: After completing the initial draft, carefully proofread your essay for grammar, punctuation, and spelling errors. Additionally, review the content for clarity, coherence, and flow.

- Peer Review: Seek feedback from a peer or someone familiar with the topic to gain an outside perspective. They can help identify any areas that need improvement.

- Stay Focused: Avoid going off-topic or including irrelevant information. Stick to the causes and effects you've outlined in your thesis statement.

- Revise as Needed: Don't hesitate to make revisions and improvements as needed. The process of revising and refining your essay is essential for producing a high-quality final product.

To Sum Up ,

Cause and effect essays are important for comprehending the intricate relationships that shape our world. With the help of the examples and tips above, you can confidently get started on your essay.

If you still need further help, you can hire a professional writer to help you out. At MyPerfectWords.com , we’ve got experienced and qualified essay writers who can help you write an excellent essay on any topic and for all academic levels.

So why wait? Contact us and request ' write an essay for me ' today!

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Caleb S. has been providing writing services for over five years and has a Masters degree from Oxford University. He is an expert in his craft and takes great pride in helping students achieve their academic goals. Caleb is a dedicated professional who always puts his clients first.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Do migrant remittances affect household spending? Focus on wedding expenditures

Jakhongir kakhkharov.

1 College of Business, Government and Law, Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia

Muzaffarjon Ahunov

2 Endicott College of International Studies, Woosong University Jayang-Dong, Dong-gu, Daejeon, South Korea

We use nationally representative survey data and propensity score matching to investigate the impact of remittances from labor migrants on households’ wedding expenditures. The investigation provides evidence that remittance-receiving households spend a smaller share of their budget on wedding ceremonies. Since lavish wedding ceremonies serve the purpose of increasing households' social status through conspicuous displays of wealth, the study concludes that remittance-recipient households are less likely to be engaged in conspicuous consumption than are households that do not receive remittances.

Introduction

International remittances refer to money that workers who are employed outside their countries send home. These unilateral transfers attract the attention of researchers and policymakers worldwide because of their size and potential as an external source of capital for emerging economies’ development.

The body of research that studies how international remittances impact households' consumption and investment patterns in remittance-receiving countries has surged over the past decade. We contribute to this literature in three ways: First, we investigate whether remittances are spent on a type of conspicuous consumption, that is, status-signaling wedding ceremonies. Although the literature on the way migrants and their families use remittances is abundant, only a few studies scrutinize the impact of remittances on conspicuous consumption. The meager extant literature on the relationship reaches contradictory conclusions. For instance, households in the Philippines that receive remittances spend more on consumer goods and leisure (Tabuga 2007 ), while remittance income does not significantly affect conspicuous consumption in Sri Lanka (De and Ratha 2012 ). We address this contradiction and focus on a specific type of conspicuous consumption–excessive expenditures on wedding ceremonies.

Second, focusing on lavish wedding ceremonies as a type of conspicuous consumption allows us to compare the consumption patterns of remittance-receiving households with those of non-recipient households through the lens of informal institutions like customs and behavior patterns that the remittance research largely ignores. In particular, the literature and policymakers express concerns that traditional and cultural structures that emphasize status-oriented activities may adversely influence how remittances are spent (Ilkhamov 2013 ; Irnazarov 2015 ; Reeves 2012 ). These expenditures are often substantial in traditional societies. For instance, Irnazarov ( 2015 ) estimates the cost of a wedding in Uzbekistan at around US$10,000, including dowry expenses, about twenty times the average monthly wage of an Uzbek laborer working in Russia (Petrova 2017 ). A similar situation occurs in neighboring Tajikistan, where ‘ peer pressure and comparisons with neighbors are indeed key factors in holding lavish ceremonies in a country in which almost half of the population lives in poverty. When someone spends $2,000 for a wedding, a neighbor will usually try to spend the same or even more money for their ceremonies’ (Najibullah 2007 , p. 2). In the context of Central Asia, these lavish ceremonies are likely to divert household resources from spending on asset accumulation, health, education, and other important matters; they are even likely to push households into debt. As a result, both Uzbekistan and Tajikistan introduced bans on the size of these traditional ceremonies.

Third, we place our research in the infrequently studied transition context of Uzbekistan, a country that has seen large inflows of remittances during the last two decades. As such, this paper is related to the Kakhkharov et al. ( 2020 ) and Kakhkharov and Ahunov ( 2020 ) studies, which use the same dataset. However, in contrast with Kakhkharov et al. ( 2020 ), we specifically focus on a particular type of expenditure (wedding ceremonies) and use a different methodology. This allows us to scrutinize the link between remittances and a particular type of conspicuous consumption. As to the Kakhkharov and Ahunov ( 2020 ) work, the study merely compares mean household expenditures to draw inferences regarding the differences in expenditures of households receiving and not receiving remittances. The present research extends the analysis using rigorous econometric techniques and arrives at results contrary to the conclusions stated in Kakhkharov and Ahunov ( 2020 ). Uzbekistan’s experience could be relevant to other transition countries in Central Asia that are at a similar stage in their paths to becoming market economies and share similar histories, traditions, cultures, and levels of exposure to remittances.

Whether institutional environment and traditions similarly influence the spending behavior of households that receive remittances and those that do not have important policy implications. If remittance-receiving households’ expenditure patterns differ from those of non-recipient households, factors beyond the characteristics of households, local institutional environment, traditions, and policy-making may need to be investigated to determine the effect of these monetary flows on economic development. Moreover, if remittances are invested in human capital, education, health, or small business, their positive impact on economic growth is maximized (Acosta 2011 ), but if remittances are spent mainly on conspicuous consumption, their effect may not be productive to the economy as a whole (Chami et al. 2003 ).

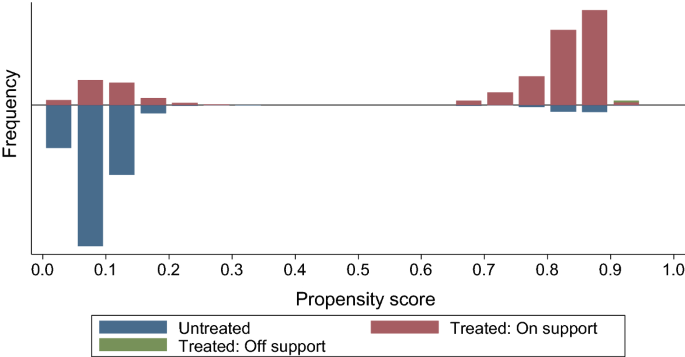

This paper uses household-level data from the Uzbekistan Jobs, Skills, and Migration Survey jointly administered by the German Agency for International Development (GIZ) and the World Bank in 2013. The survey covers 1,500 households, and it is nationally representative. We, therefore, can investigate the impact of remittances on certain household expenditures items, especially traditional ceremonies. In contrast with most empirical studies in this area, which apply ordinary least squares (OLS) methodology supplemented by a sample-selection procedure or instrumental variable estimations, we use a propensity score matching (PSM) methodology to evaluate the impact of remittances on household expenditures. This methodology is often used to assess the effects of policies because it can give accurate results in non-experimental settings (Caliendo and Kopeinig 2008 ; Dehejia and Wahba 1999 ). The results of our analysis provide evidence that households that receive remittances tend to spend a smaller share of their earnings on traditional ceremonies and a greater share on other large non-food items than do households that do not receive remittances. These results show that remittance recipients are less likely to engage in conspicuous consumption.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature on the topic, while Sect. 3 presents the data and the research methodology. Section 4 reports the results, and Sect. 5 draws conclusions and discusses policy implications.

Literature review

Arguing that almost everyone wants to display wealth and attain the rank associated with it, Adam Smith (1759) was among the first scholars to suggest the significance of conspicuous consumption as a motivator of human behavior. The rigorous theoretical study of social status and conspicuous consumption dates back to Veblen ( 1899 ), who defines conspicuous consumption as consumption that has the purpose of demonstrating one’s economic position to others. Ireland (1994) and Bagwell and Bernheim ( 1996 ) further developed the theory of conspicuous consumption as a signal of wealth. Since then, conspicuous consumption has become a well-researched area, but most research still focuses on luxury goods and ignores luxury experiences like expensive wedding celebrations. This paper investigates this unconventional type of households’ conspicuous consumption in the context of international remittances received in Uzbekistan.

Lavish celebrations of weddings and other life events to enhance the status of households are common in developing countries and the transition economies of the former Soviet Union. Exorbitant celebrations are documented in scholarly discourse for India (Bloch et al. 2004 ; Rao 2001 ), Namibia (Pauli 2013 ), Tajikistan (Marat 2008 ), and Kazakhstan (Werner 1997 ), among other countries. These expenditures could be considered reasonable if they help maintain social bonds and networks to cope with poverty (Rao 2001 ). Still, many observers find that conspicuous consumption frequently comes at the expense of basic and more productive needs, such as education and healthcare (Charles et al. 2009 ; Linssen et al. 2011 ).

The expenditure decisions of households are related to a large extent to the reasons why migrants send remittances. Therefore, Lucas and Stark ( 1985 ) develop a theoretical framework for micro-level investigations on remittances and pin down three principal motivations for sending remittances at the household level. These are pure altruism, pure self-interest, and tempered altruism or enlightened self-interest. The problem is that in many cases, these motives could account for a similar type of migration and remittance behaviors.

A valuable framework for studying remittances, migration, and household expenditures is the New Economics of Labor Migration (NELM), developed by Stark ( 1991 ) and colleagues to link remittance behavior to migration decisions. According to NELM, households decide to send a household member to work in another country to improve the family’s well-being by maximizing joint income and minimizing risks. Therefore, the primary purpose of remittances is to provide additional funding, insurance in case the primary source of family income falters, and financial protection for a rainy day. The NELM is an original, sensible, and functional framework used extensively in studies of remittances and migration. However, the NELM framework assumes that households act rationally and neglects the role of informal social institutions (e.g., traditions, positions, norms, community, extended family, informal associations) as determinants of behavior (Aslan 2011 ; Hagen-Zanker 2010 ). In the context of Uzbekistan, the present research shows that these informal social institutions and traditions have less influence over the spending decisions of households that receive remittances than they do over households that do not, indicating that remittances are transforming social institutions.

Carling ( 2014 ) uses a “scripts” approach to explain the expenditure behavior of remittance recipients and transformations in social and non-economic institutions. This approach in the context of the present paper is more appropriate because the NELM’s focus on economic utility may obscure the relational aspects of remittances (Åkesson 2011 ), which appear to be a dominant factor for interpreting the expenditures patterns of Uzbek households receiving remittances. Indeed, migrants may “authorize” (one of the scripts suggested by Carling ( 2014 )) particular expenditures on the migrant’s behalf, households may “pool” (another script proposed by Carling ( 2014 )) their resources for the wedding ceremony purposes. Modern information and communication technologies (ICT), in turn, enable migrants to monitor how remittances are spent, which imbues expenditures with the identity of the remitter (Åkesson 2011 ). Thus, the “scripts” framework differs from the NELM because it may explain the spending behavior of households based not exclusively on motivations to remit but also on expectations of a remitter how the remitted money should be spent. These expectations, in turn, could be impacted and shaped by the environment migrants live and work that could result in shifts in the perceptions of appropriate spending behavior that is prevailing in their home country.

Even though the empirical evidence that a big part of remittances is spent on conspicuous consumption remains limited, several studies voiced concerns about wasting the income from remittances in the status-oriented consumption of goods and services (Airola 2007 ; Carling 2008 ; Zarate‐Hoyos 2004 ). Day and Içduygu ( 1999 ) use interviews with migrant households to demonstrate some cases of conspicuous consumption. Likewise, Tabuga ( 2007 ), using quantile regressions, shows that remittance-receiving households allocate more to conspicuous consumption in the Philippines than their peers that do not receive remittances. Since data for leisure were not disaggregated, Tabuga recommends a more detailed study of leisure, and we respond to this call by focusing on a specific type of family occasion (wedding ceremonies) for the case of Uzbekistan. Contrary to these findings, De and Ratha ( 2012 ) document that remittances in Sri Lanka do not have a statistically significant impact on another type of conspicuous consumption–the accumulation of ‘luxury’ assets like motor vehicles and land.

Studies applying advanced econometric methods to identify the relationship between remittances and household expenditures in Central Asia remain scant. One of the few such examples is Clément ( 2011 ), who applies PSM analysis to a dataset for Tajikistan to show that households that receive remittances spend more on food, non-food items, and health than do households that do not. Analogously to Kakhkharov et al. ( 2020 ), Clément ( 2011 ) finds no evidence of a significant effect of remittances on education expenditures.

Uzbekistan is the most populous (33.5 million inhabitants) and the primary migrant worker sending country in the former USSR. Russia and Kazakhstan are the main destinations for the predominantly seasonal labor migration of migrant workers from Uzbekistan. Estimates indicate about 2.5 million Uzbek labor migrants are abroad, with some two million working in Russia (IWPR 2021 ). These migratory flows have complex repercussions on the societies and economies of Russia, Kazakhstan, and impoverished Uzbekistan. Labor out-migration eases unemployment-fueled social tension and political instability (Laruelle 2007 ). For example, despite travel restrictions introduced during the Covid-19 pandemic, the total volume of recorded remittances from Russia to Uzbekistan reached US$ 4.24 billion in 2020 (Central Bank of Russia 2020 ). This makes up roughly 7.6% of Uzbekistan’s GDP. Remittances from Kazakhstan appear to be small at US$ 351 million (TASS 2021 ). However, the long land border between Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan and the visa-free regime may have facilitated the informal flow of remittances. The figures for officially recorded remittances may significantly underestimate the volume of total remittances (Kakhkharov et al. 2017 ).