Home — Essay Samples — Education — Studying Abroad — The Positive Effects of Studying Abroad for Students

The Positive Effects of Studying Abroad for Students

- Categories: Studying Abroad

About this sample

Words: 484 |

Published: Mar 1, 2019

Words: 484 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Reasons for Studying Abroad

Works cited.

- Byram, M. (2018). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Routledge.

- Chieffo, L., & Griffiths, L. (2004). Bridging the divide: student perspectives of international study. Journal of Studies in International Education, 8(1), 32-47.

- Hadisaputro, R., & Utomo, Y. K. (2020). International Students’ Perceptions of Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Academic Performance in Indonesia. Journal of International Students, 10(2), 323-340.

- Li, M., & Bray, M. (2007). Cross-cultural perspectives on international students. International Education Journal, 8(2), 395-408.

- Mazzarol, T., Soutar, G. N., & Seng, M. S. (2003). The third wave: Future trends in international education. International Journal of Educational Management.

- Mitchell, K. E., & Latcheva, R. (2019). International Student Migration: Mapping the Field and New Research Agenda. Population, Space and Place, 25(1), e2193.

- Olt, M. R., & Yucesoylu, R. (2017). International student recruitment and enrollment strategies in higher education. Journal of International Students, 7(3), 587-603.

- Rienties, B., & Nolan, E. M. (2014). Understanding friendship and learning networks of international and host students using longitudinal social network analysis. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 41, 165-180.

- Stebleton, M. J., Soria, K. M., & Cherney, B. (2013). Experiences of international graduate students from Saudi Arabia: Factors that facilitate and hinder adjustment. Journal of College Student Development , 54(6), 617-634.

- Williams, E. A. (2005). Overseas students and intercultural adaptation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29(6), 689-711.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Heisenberg

Verified writer

- Expert in: Education

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 919 words

4 pages / 2033 words

1 pages / 605 words

3 pages / 1309 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Studying Abroad

Culture and its behavior are a sturdy part of everyone’s life. It has a major impact on our perspectives, our values, humor, hopes, believes, and worries. According to me, learning other cultures motivate us to visit and [...]

Education is a transformative journey that shapes individuals and prepares them for their future endeavors. When it comes to higher education, students face a critical decision: whether to pursue their studies in their home [...]

Study abroad programs hold a special place in higher education, offering students the opportunity to immerse themselves in new cultures, gain global awareness, and foster intercultural understanding. However, the path to [...]

International Baccalaureate Organization. (2020). Mission and strategy. Retrieved from 385-405.

Each year, number of students is increasing who look forward to study in the US, as they want to expand their educational experience in the world class system. But have any of us ever given it a random thought so as to why many [...]

Why would a student choose to study abroad? Why would someone choose to move to another country, and leave his or her whole life behind? There are many reasons for a person to choose to live abroad, or for a student to study [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

63 Study Abroad Essay Examples & Topics

Looking for study abroad topics to write about? Studying in another country is one of the most beneficial experiences for students.

- 🏆 Best Essay Examples

- 📌 Research Titles

- 🗺 Topics to Write about

❓ Questions About Studying Abroad

In your studying abroad essay, you might want to write about advantages and disadvantages of being an international student. Another option is to describe the process of making application for a scholarship. One more idea is to share your personal experience. Whether you’re planning to write an argumentative, descriptive, or persuasive essay, our article will be helpful. Here we’ve collected top studying abroad essay samples and research titles for scholarship papers.

🏆 Best Studying Abroad Essay Examples

- Why Studying Abroad Results in Better Education For most people, especially in developing nations, the only way to gain an education that will satisfy the demands of the international job market is by studying abroad.

- Should Students Study Abroad? Studying abroad offers students an opportunity to travel to new countries and have new experiences that expand their perceptions of the world.

- Education in Australia as a Tool of Promoting Equality of Opportunity The main objective of vocational education and training is to promote the people, the society, and the economy and to upgrade the labor market.

- Specifics of Studying Abroad The purpose of this paper is to discuss the most common benefits and drawbacks, as well as overall outcomes that are related to studying abroad and to recommend the ways to handle the drawbacks.

- Challenges of Studying Abroad A closer look at the information provided by the majority of the companies specializing in student transfer and the related services will reveal that a range of essential data, especially the information concerning the financial […]

- Declining Direct Public Support for Higher Education in USA Partisanship interest in the debate for renewal of the Higher Education Act and a Senate inquiry to validate the governance of the non-profit economic sectors of the United States has demonstrated the complexity of public […]

- The Social Role of Higher Education in UK In addition to this, higher education provides a set of values that changes the students to face the existing and the future problems facing the society and the various sectors of work that they operate […]

- International Education in Australia China is a good market for Australian education and in the year 2010 a sum of 284700 students from China left the country to further their studies most of them on their own expenses.

- The Criteria and Benefits That Allow Students to Work Abroad The most direct experience that a person gets while studying abroad is the understanding of the business world and economics. There is no doubt that the environments and culture of a country are the major […]

- A Benefits of Education Abroad One of the qualitative aspects of the educational reality in today’s world is the fact that, as time goes on, the number of students who decide in favor of studying abroad increases rather exponentially.

📌 Research Titles about Studying Abroad

- Do Study Abroad Programs Enhance the Employability of Graduates

- The Effect Of Study Abroad On Studying Abroad

- Culture and Study Abroad and Some Drawbacks

- How Does Study Abroad Affect A Student ‘s View Of Professional

- Analysis Of Some Of The Benefits Of Study Abroad

- Do People Who Study Abroad Become More Successful

- Increasing Number Of Worldwide People Go Study Abroad

- The Lowering Ages of Students Who Study Abroad

- Colleges Should Make It Mandatory: For Students To Study Abroad For Specific Major’s

- Should Students Spend Lots Of Money For Study Abroad

🗺 Study Abroad Topics to Write about

- The Cultural Shock That Students Face When They Study Abroad

- Advantages and Dis Advantages of Further Study Abroad

- Interlanguage Pragmatic Competence in the Study Abroad

- The Study Abroad Trip On Australia

- History Of Study Abroad And Exchange Programs

- An Analysis of Many Students Wishing to Study Abroad

- Most Study Abroad Program Should Be Rename Party Abroad They Are Waste of Time

- Why College Students Should Study Abroad

- Analysis Of Michelle Obama ‘s Reasons For Study Abroad

- Study Abroad Is Beneficial For All College Students

- The Journey of Traveling and The Study Abroad

- Analysis: Why Student Chose to Study Abroad

- The Benefits of Choosing to Study Abroad

- How Is Studying Abroad Helps Improve Language Skills?

- Which Country Are More Successful for Studying Abroad?

- Is Studying Abroad a Good Idea?

- Does Studying Abroad Induce a Brain Drain?

- Why Is Studying Abroad Beneficial?

- How Is the Studying Abroad Effects Learning About Different Cultures?

- What Are the Cons of Studying Abroad?

- Is Studying Abroad a Waste of Time?

- Does Studying Abroad Enhance Employability?

- What Are the Positive and Negative Influences of Studying Abroad?

- How Capital Accumulation Through Studying Abroad and Return Migration?

- Which Country Is Best for Studying Abroad?

- What Is Culture Shock When Studying Abroad?

- What Is the Impact of Studying Abroad on Global Awareness?

- What Are the Disadvantages of Studying Abroad?

- Which Country Is Cheapest for Studying Abroad?

- Is Studying Abroad Expensive?

- What Are Important Reasons for Studying Abroad?

- Is It Difficult to Studying Abroad?

- What Are the Advantages and Disadvantages of Studying Abroad?

- Which Country Is Hard for Studying Abroad In?

- What Is the Impact of Studying Abroad?

- What Are the Effects of Studying Abroad on College Students?

- What Are Main Hardships While Studying Abroad?

- Is It Better to Studying Abroad or Locally?

- Does Studying Abroad Help Academic Achievement?

- Does Studying Abroad Cause International Labor Mobility?

- What Are the Differences Between Studying Locally and Studying Abroad?

- Do Students Who Studying Abroad Achieve Tremendous Success?

- What Are the Pros and Cons of Studying Abroad?

- Motivation Research Ideas

- Brain-Based Learning Essay Titles

- Academic Dishonesty Research Ideas

- Machine Learning Ideas

- Listening Skills Essay Ideas

- Problem Solving Essay Ideas

- School Uniforms Topics

- Stress Titles

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, October 26). 63 Study Abroad Essay Examples & Topics. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/study-abroad-essay-examples/

"63 Study Abroad Essay Examples & Topics." IvyPanda , 26 Oct. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/study-abroad-essay-examples/.

IvyPanda . (2023) '63 Study Abroad Essay Examples & Topics'. 26 October.

IvyPanda . 2023. "63 Study Abroad Essay Examples & Topics." October 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/study-abroad-essay-examples/.

1. IvyPanda . "63 Study Abroad Essay Examples & Topics." October 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/study-abroad-essay-examples/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "63 Study Abroad Essay Examples & Topics." October 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/study-abroad-essay-examples/.

The impact of studying abroad - and of being made to return home again

David mckenzie.

Studying abroad is becoming increasingly common in many countries – with almost 3 million students educated each year at the tertiary level in a country other than their own. For developing countries in particular, studying abroad offers many of the promises and fears of brain drain (both of which I think are overblown). But understanding the causal impact is hard, because people self-select into whether or not to study abroad, and there are no lotteries or other experiments we can turn to for easy answers. Three recent non-experimental papers succeed to varying degrees in providing some convincing causal evidence.

The most convincing of the three studies is a recent paper by Matthias Parey and Fabian Waldinger which has just appeared in the Economic Journal. They consider the impact of studying abroad due to the European Erasmus student exchange program on whether German students live abroad in the first 5 years after graduating. They find studying abroad for a year during undergraduate studies (after which they return to finish their studies) increases the likelihood of working abroad early in the career by 15 percentage points, and provide some suggestive evidence that one of the channels for this might be through meeting a foreign partner, in addition to the more work-related channels.

The Erasmus study uses instrumental variables for identification. They rely on the fact that the Erasmus program was rolled out slowly through German universities and departments within universities. Controlling for a student’s entry cohort, subject, and university, they argue that the fact that, for example, there were scholarships for political science at University X but not for economics, whereas for University Y there were scholarships for economics but not political science, was due to idiosyncratic reasons such as particular faculty connections. What is very nice about the paper is that they take threats to the exclusions restrictions very seriously, and have more than 2 pages carefully discussing possible threats to identification, checks they can do to rule these threats out, and a whole lot of sensitivity analysis. They also note that while IV allows them to only estimate a local average treatment effect (LATE), this LATE is precisely the parameter of policy interest- the effects of studying abroad for those people who only study abroad due to the Erasmus program.

A second approach is used by Oosterbeek and Webbink in a paper just out in Economica . They consider Dutch students who apply to a scholarship program to study for year abroad of graduate study. The selection committee ranks all students, and only those whose rank is above a certain cut-off get a scholarship. This naturally leads to a regression discontinuity approach, which compares outcomes for students just above and just below this threshold. The downside is that the scholarship is pretty exclusive, so even pooling together multiple years of entrants still only gives 25 students just below the cutoff and 51 just above. They find for this group that studying abroad increases the likelihood of living outside of the Netherlands early in their career by 30 percentage points.

The identification idea is sound in this paper, but the small sample size makes it more difficult to do a number of the best practice smoothness checks around the discontinuity with any precision. Moreover, as is well-known, regression discontinuity designs only identify the treatment effect in the neighborhood of the discontinuity. In this case the sample is pretty specialized – talented Dutch students who apply for this particular scholarship, in a context where to apply for the scholarship they already have to have a definite plan of where they will study abroad, that it may be more difficult to generalize these findings.

A further challenge both these studies face is a common one in migration work – of actually being able to track migrants. Both surveys only look at people relatively soon after graduation, and tracking rates seem to still be only 51% in the Dutch survey and 25% in the German surveys. This points to the need for better systems of tracking migrants.

The third, and least convincing paper, is also the one that is likely of most direct interest to developing countries. In a paper appearing in a recent NBER volume, Kahn and MacGarvie try and examine the impacts of the U.S. Foreign Fulbright program on knowledge creation in sciences and engineering. The Fulbright program provides scholarships to enable foreign students to come to U.S. graduate schools, but then requires that these students return to their home countries for 2 years after graduation. [Fun fact: apparently working for the World Bank or other international organizations is a loophole]. The question then is whether and how forcing people to go back to their home countries after graduate study impacts on their careers. The authors find Fulbright recipients in sciences and engineering have significantly fewer high-impact publications and overall citations, with this result strongest for people from the poorest countries – i.e. being made to go back to a poor country is a career killer.

The result seems intuitive enough, but the identification is not very convincing. The authors employ a matching approach , attempting to match each Fulbright recipient to another foreign student in the U.S. on a few basic characteristics such as ranking of PhD institution, field of study, year of Ph.D., gender, and log GDP of the home country. This is not convincing for several reasons. First, it assumes that people who got Fulbrights would have been able to study abroad if they didn’t get them – whereas a regression discontinuity based on comparing those who just miss out on the Fulbright to those who get it might be more compelling. Second, matching is on the basis of variables which themselves might be outcomes of getting the Fulbright, not ex ante determinants. Third, matching is more convincing when there is a rich set of variables to match on, which definitely doesn’t describe this case. And finally, this is a case where I would find it hard to find matching convincing – given how important this Fulbright requirement to return is, I would expect to find people self-selecting into whether they apply or not (and whether they take it up or not) depending on their desire to return home.

The return requirements of the Fulbright and other scholarship programs certainly warrant further study. John Gibson and I have studied emigration from Papua New Guinea, and find many high-skilled individuals there who appear to have returned to PNG after studying in Australia because of a 2-year return requirement, and that few of these then seem to have subsequently left again. So I believe that these requirements may have large effects – but don’t think we know much about what the cost in terms of career prospects are of such requirements.

The impacts of policies to spur or hinder international student mobility are important to learn about, so it is great to see some papers starting to look at these issues – and to see plenty of scope for further work which builds on this. To get a broader view of new research in migration, take a look at the program for the 4 th Migration and Development Conference which was held a week ago at Harvard: lots of interesting new studies were presented.

Lead Economist, Development Research Group, World Bank

Join the Conversation

- Share on mail

- comments added

Error message

- College Study Abroad

- College Study Abroad Blog

Why Study Abroad? Top 7 Benefits of Studying Abroad in 2024

March 4, 2024

Authored By:

@cieestudyabroad Just a few of the countless benefits of studying abroad! #cieestudyabroad #studyabroad #benefits #whystudyabroad #internationalstudent #culturalexchange Same Cycle Different Day - xJ-Will

If the question “why study abroad?” has crossed your mind, you’ve probably done preliminary research to discover the benefits of studying abroad . During said research, you’ve likely come across reviews from study abroad alums describing their experiences as “life-changing.”

While that’s quite the high praise, the long-term impact of study abroad overwhelmingly shows the personal, professional, and academic benefits study abroad students gain from their programs do, in fact, change their lives.

Let's dig deeper into how study abroad is so life-changing and unpack the top 7 benefits of studying abroad , which include:

- Connecting with new cultures and languages

- Meeting locals and make a new home abroad

- Seeing the world and gain a new perspective

- Going on unique excursions that bring your studies to life

- Boosting your resume with international experience

- Forming lifelong friendships

- You'll experience best-in-class academics

From setting your career up for success in today’s increasingly globally diverse world to forming friendships all around the globe that’ll last a lifetime, you’ll end your CIEE program with numerous advantages of study abroad that are sure to positively benefit your future wherever you go next in life.

Discover Our Top 7 Benefits of Studying Abroad in College

1. you’ll connect with new cultures and languages..

One of the key benefits of studying abroad is being able to immerse yourself in a culture that’s different from your own. Maybe you’ll choose to study in Spain and live with a host family to learn how they cook authentic paella. Perhaps you’ll choose to study abroad in Sydney where you’ll learn about the Aboriginal culture that dates back more than 60,000 years ago. Maybe you’d like to study abroad in Jordan and visit Petra, home to Al-Khazneh, one of the oldest and most magnificent structures on the planet. Regardless of where you choose to go, one of the main benefits of studying abroad is connecting with new cultures, people, art, values, fashion, and more.

In the vein of making connections, studying abroad will also help you build new (or strengthen your existing) language skills in a native-speaking country. Being fully immersed in a culture that primarily speaks their native language is one of the most effective ways to develop and improve your foreign language skills. Whether you want to refine your Spanish language skills in Latin America , study Chinese for the first time in Shanghai , or put your Korean language skills to the test in Seoul , CIEE’s programs in 30+ diverse global cities around the world offer you plenty of places to learn an entirely new language or improve your existing knowledge in a real-world context.

2. You’ll meet locals who help you feel at home away from home.

Establishing your home away from home can be tricky, especially in the first few weeks in a new city. Thankfully, the people you meet abroad are determined to help you feel right at home. Not only will your host family welcome you into their home with open arms, but our on-site staff at each CIEE center work hard to foster a sense of community with you abroad as well.

Whether with your favorite local pastry shop owner or one of your professors, engaging with locals abroad can help you build a home away from home. Not to mention, feeling connected to your community abroad will combat any feelings of homesickness you may (or may not) experience during your program.

“I had a fantastic time and the CIEE Seoul staff were so attentive and helpful at all times. They were like my family here while on study abroad.” – Aaliyah A., Howard University.

3. you’ll see the world and gain a new perspective..

Challenging your worldview is one of the most important skills you gain from study abroad. During your time living and learning in a new country, you’ll not only explore new environments, but also gain a more nuanced perspective of humanity, geopolitics, the environment, and more. In doing so, you’ll have more empathy toward others, appreciate how other cultures approach work, religion, family, and so on, and acquire a deeper understanding of how the world works.

By the end of your program, your newfound global perspective will impact the way you approach your education, career, family, friends, and community back home, whether you realize it – or not.

Explore CIEE Study Abroad Programs

4. You’ll go on unique cultural excursions to bring your studies to life.

Each study abroad and global internship program at CIEE is infused with unique cultural excursions, giving you plenty of opportunities to take your learnings outside of the classroom for real-world application and impact. Through our one-of-a-kind excursions and study tours, you’ll apply your academics to the outside world by exploring important cultural sites, chatting with local guides, cooking authentic cuisine, and more!

From a day-trip two hours outside of Seville to the seaside city of Cadiz to an overnight excursion to the luxurious city of Marrakesh in Morocco to a visit to the National Museum of Korean Contemporary History in Seoul, CIEE’s cultural excursions offer something for everyone.

5. You’ll boost your resume with real-world international work experience.

Studies show 97% of students who study abroad find employment within 12 months of graduation and 25% earn higher salaries than their peers. With a global internship , you can boost your resume and gain the competitive edge you need to stand out to future employers. From problem-solving and communication skills to adaptability and cultural competence, companies love to hear about demonstrable skills gained abroad that you can bring to their organization.

Whether you long to intern with an environmental organization in Costa Rica where you’ll work hands-on to learn about sustainable waste management on a dairy farm or you’d love to spend your summer interning in Barcelona at a startup organization in the retail space, the career benefits you’ll gain during a global internship are unmatched and highly competitive.

From semester-long internships to summer internships to study abroad programs with internships baked into them to virtual opportunities , we offer global internships for all types of work experiences in a wide variety of industries that are guaranteed to benefit your future career.

6. You’ll form new friendships that’ll last a lifetime.

The moment your study abroad program begins, you’ll meet new people you likely wouldn’t have met otherwise and develop strong bonds with them through your shared cultural experiences.

From CIEE staff, professors, and administrators to your fellow classmates, you’ll form strong connections with your community abroad as you live and learn in a new city together every day both in and outside of the classroom.

What better way to make the most of your study abroad journey than sharing your experience with your new besties immersed in the program with you? With such a unique shared experience, it’s no wonder alums say they form long-lasting relationships with the friends they meet abroad.

“It was one of the most amazing experiences of my life. I discovered so much about myself and the new culture, as well as having made long-lasting friendships!” – Clara D., Arizona State University

7. you’ll enjoy best-in-class academics..

No matter which CIEE Study Abroad program and location you choose, you’ll take top-tier academic courses that earn you transferable college credits. We give you the option of enrolling in courses exclusively delivered by CIEE and courses offered by the host institutions we partner with, which may never have otherwise been available to you. Topics cover a wide variety of areas of study, including (but not limited to):

- Intercultural Communication

- Language Studies (e.g. varying levels of Spanish, Chinese, French, Japanese, Italian, Korean, etc.)

- Environmental Conservation

- History and Philosophical Studies

- Public Health

In addition to your coursework, you may also have the option to complete independent research or an internship in your desired field . To ensure the courses you complete abroad can be transferred to your host university, you should consult your study abroad advisor.

With study abroad benefits like these, it’s no wonder students often describe their study abroad experiences as life-changing. Rest assured that when you study abroad with CIEE, you’ll experience the main benefits of studying abroad discussed in this article, from receiving best-in-class academics to gaining a newfound worldview – and everything in between.

Ready to take the next step?

Start your application today!

- Activities & Excursions

- Best Time to Study Abroad

Related Posts

Seville to Portugal: a guide and my story

By: Maria Brunetta DOs: Purchase a Viva Viagem Card in Lisbon Take a half-day trip to Sintra Visit Porto for 2 days minimum See a “Fado” show, the traditional music... keep reading

Seville in the Spring: A once in a lifetime experience

By: Maria Brunetta Nothing could prepare me for the unique atmosphere that Seville has during the springtime. When we arrived on January 17th, the sun was shining and the air... keep reading

Mallorca: A Stopover For Many Birds (by Eli Talens)

Mallorca is well known for its magnificent beaches and the impressive mountain range of the Sierra de Tramontana, a line of peaks that crosses the island from east to west... keep reading

© 2024 CIEE. All Rights Reserved.

- Privacy Notice

- Terms & Conditions

Who benefits most from studying abroad? A conceptual and empirical overview

- Open access

- Published: 09 November 2021

- Volume 82 , pages 1049–1069, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Nicolai Netz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7272-3502 1

19k Accesses

17 Citations

21 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This editorial to the special issue on heterogeneous effects of studying abroad starts with a review of studies on the determinants and individual-level effects of studying abroad. On that basis, it illustrates the necessity to place more emphasis on effect heterogeneity in research on international student mobility. It then develops a typology of heterogeneous effects of studying abroad, which shall function as an agenda for future research in the field. Thereafter, the editorial introduces the contributions to the special issue. It concludes by summarising major findings and directions for future research.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Rationale of the special issue

In the last decades, the facilitation of international student mobility (ISM) has been a key action line of European higher education policy (Ferencz & Wächter, 2012 ). Since the 1950s, ISM has been promoted as a means to generate societal benefits through knowledge exchange, social cohesion, and economic prosperity (Baron, 1993 ). Since the 2009 Leuven Conference of the European ministers responsible for higher education, policy-makers have additionally emphasised the individual benefits of studying abroad for the mobile students (Ministerial Conference, 2009 , 2012 ). Footnote 1

Along with this development, both policy-makers and scholars have become increasingly interested in who gets access to the benefits of studying abroad. From a variety of disciplinary perspectives—including psychology, educational sciences, economics, and sociology—it matters which factors influence access to studying abroad, and how studying abroad affects individual life courses. In recent years, research has made great progress in answering these questions.

On the one hand, various studies have enhanced our understanding of the factors that influence study abroad participation. These studies have shown, for instance, that the likelihood of studying abroad depends on students’ personality traits (e.g. Bakalis & Joiner, 2004 ; Zimmermann & Neyer, 2013 ), beliefs, attitudes, norms, and corresponding benefit expectations (e.g. Petzold & Moog, 2018 ; Presley et al., 2010 ; Sánchez et al., 2006 ; Schnusenberg et al., 2012 ), socio-demographic features (for an overview, see Netz et al., 2020 ), such as their gender (e.g. Böttcher et al., 2016 ; Cordua & Netz, 2021 ; Salisbury et al., 2010 ; Van Mol, 2021 ), age (e.g. Messer & Wolter, 2007 ; Netz, 2015 ), ethnicity (e.g. Netz & Sarcletti, 2021 ; Pungas et al., 2015 ; Simon & Ainsworth, 2012 ), and social origin (e.g. Di Pietro, 2020 ; Lingo, 2019 ; Netz & Finger, 2016 ; Waters & Brooks, 2010 ), previous experience with spatial mobility (e.g. Carlson, 2013 ; Lörz et al., 2016 ), academic performance in school and higher education (e.g. Favero & Fucci, 2017 ; Wiers-Jenssen, 2011 ; Wiers-Jenssen & Try, 2005 ), and literacy, numeracy, technical, and foreign language skills (e.g. Di Pietro & Page, 2008 ; Kommers, 2020 ). Furthermore, various contextual factors shape students’ opportunities to study abroad. These factors include the attitudes, expectations, and resources of students’ parents (e.g. Bodycott, 2009 ; Brux & Fry, 2010 ; Hurst, 2019 ; Pimpa, 2003 ) and peers (e.g. Brooks & Waters, 2010 ; Van Mol & Timmerman, 2014 ), the support of faculty members (e.g. Paus & Robinson, 2008 ), students’ field of study (e.g. Iriondo, 2020 ; Schmidt & Pardo, 2017 ; Schnepf & Colagrossi, 2020 ), the design of study programmes (e.g. Perna et al., 2015 ), the availability of institutional or state funding (e.g. Kramer & Wu, 2021 ; Whatley, 2017 ), the economic wealth of countries, and the quality of national higher education systems (e.g. Beine et al., 2014 ; Rodríguez et al., 2011 ; Vögtle & Windzio, 2016 ).

On the other hand, impact evaluations have shown that studying abroad can influence various domains of students’ life courses. For instance, they have illustrated that studying abroad can affect students’ personality development (e.g. Niehoff et al., 2017 ; Richter et al., 2021 ; Zimmermann et al., 2021 ), identity (e.g. King & Ruiz-Gelices, 2003 ; Sigalas, 2010 ; Van Mol, 2013 ), language proficiency (e.g. Brecht et al., 1993 ; Jackson et al., 2020 ; Magnan & Back, 2007 ), multi- or intercultural sensitivity and competences (e.g. Anderson et al., 2006 ; Clarke et al., 2009 ; Williams, 2005 ; Wolff & Borzikowsky, 2018 ), self-efficacy (e.g. Milstein, 2005 ; Nguyen et al., 2018 ; Petersdotter et al., 2017 ), and academic development and achievement (e.g. Cardwell, 2020 ; McKeown et al., 2020 ; Nerlich, 2021 ; Whatley & Canché, 2021 ). In recent years, in particular, various studies have also examined the effects of studying abroad on graduates’ labour market outcomes (for an overview, see Netz & Cordua, 2021 ; Roy et al., 2019 ; Waibel et al., 2017 ; Wiers-Jenssen et al., 2020 ). Among other things, scholars have assessed the effects of studying abroad on the job search duration and the likelihood of employment (e.g. Di Pietro, 2015 ; Liwiński, 2019a ; Petzold, 2017a ), skills mismatch (e.g. Wiers-Jenssen & Try, 2005 ), involvement in international job tasks (e.g. Teichler, 2011 ; Wiers-Jenssen, 2008 ), international labour market migration (e.g. Di Pietro, 2012 ; Parey & Waldinger, 2011 ), the occupational status (e.g. Waibel et al., 2018 ), and wages (e.g. Jacob et al., 2019 ; Kratz & Netz, 2018 ).

This short literature review illustrates that existing research already provides a comprehensive overview of the determinants and individual-level effects of studying abroad. Yet, it has not sufficiently acknowledged a simple possibility: It is unlikely that all individuals benefit from studying abroad to the same extent. While several studies have performed sensitivity analyses to ensure the robustness of their results across groups of students, educational, employment, and living contexts, as well as types of stays abroad, only a few studies have explicitly focused on heterogeneity in the effects of studying abroad. Mostly, existing studies have concentrated on quantifying an average effect for all individuals in their respective population sample (as becomes evident in several literature reviews: Netz & Cordua, 2021 ; Roy et al., 2019 ; Waibel et al., 2017 ).

However, shifting the focus on effect heterogeneity is beneficial for various reasons—which is already widely acknowledged in the broader literature on returns to higher education (for examples, see Bauldry, 2014 ; Brand & Xie, 2010 ; Triventi, 2013 ; Walker, 2020 ). As the next section demonstrates, this focus is often a prerequisite for adequately testing specific theoretical assumptions. For instance, assumptions about group differences in individual behaviour and in the returns to education are at the heart of theoretical models deriving from social stratification research.

Explicitly modelling effect heterogeneity can also be imperative methodologically (Breen et al., 2015 ; Elwert & Winship, 2010 ). Especially when examining diverse samples of students, the proper specification of an effect of studying abroad usually requires scholars to capture differential selection, that is, individual or group-specific patterns of study abroad participation. Additionally, they need to capture the variables or types of stays abroad across which effects are assumed to exhibit the most substantial variation. In cases where the true effects of studying abroad are likely to differ notably across individuals, groups, or types of stays abroad, one may also question the validity of average effects for entire population samples and of broad summary measures of ISM. Hence, it is both theoretically and methodologically useful to address the question of who benefits most from studying abroad.

Last but not least, answering this question is crucial from a policy perspective. Not only does this create the basis for assessing the political promise that studying abroad yields individual benefits. It also helps answer the question of whether—or rather under which circumstances—the often costly ISM policies pay off. More knowledge about group-specific patterns of selection into ISM could help policy-makers reduce crowding-out effects. More knowledge about heterogeneous returns could ease targeted student support and compensatory measures. Such interventions could increase the efficiency of policy interventions and counteract the often-observed generation of social inequalities in the context of ISM.

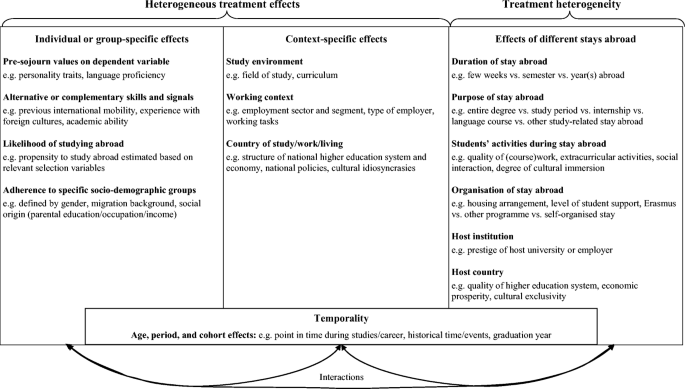

Heterogeneous effects of studying abroad: a typology for future research

Following the methodological literature in the social sciences (e.g. Breen et al., 2015 ; Carneiro et al., 2011 ; Elwert & Winship, 2010 ; Xie et al., 2012 ), we can conceptually distinguish different types of effect heterogeneity. In a first step, we can differentiate between heterogeneous treatment effects and treatment heterogeneity. A heterogeneous treatment effect arises if the outcome of a specific treatment—that is, an intervention or social phenomenon of interest—varies depending on the values of a third, moderating variable. In contrast, treatment heterogeneity describes the case that different treatments are under examination.

In research on the outcomes of studying abroad, it is difficult to neatly separate these two types of effect heterogeneity. Because two individuals are unlikely to complete the exact same type of stay abroad in practice, examining heterogeneous treatment effects will usually capture some degree of treatment heterogeneity—which is a problem that might generally not be considered enough in research on the outcomes of social phenomena. Still, applying the insights of the mentioned methodological literature and of different disciplinary approaches enables the development of an entire agenda for future research in the field (see Fig. 1 ). Footnote 2

A typology of heterogeneous effects of studying abroad

To begin with, the effect of studying abroad may be heterogeneous across individuals and groups. First of all, the pre-sojourn values on a dependent variable shape students’ potential to benefit from studying abroad. This perspective is particularly relevant for psychologists and educational scientists, who frequently capture their outcomes of interest using Likert scales. For instance, a very high pre-sojourn conscientiousness naturally limits students to indicate further personality development through studying abroad on a 5-point scale (Niehoff et al., 2017 ). Vice versa, this does not always imply that students with the lowest pre-sojourn values benefit most from studying abroad. With regard to language acquisition, for example, the potential to benefit from studying abroad seems to be limited for students who lack a linguistic basis to build upon (Magnan & Back, 2007 ). Thus, students with intermediate values on the examined dependent variables might in many respects be in a good position to benefit from studying abroad.

Relatedly, individuals’ alternative or complementary skills and signals may govern their potential to benefit from studying abroad. For instance, studying abroad could be less beneficial for students who have previously received similar treatments, such as international experience during school or higher education, or home-country experience with foreign cultures (Nguyen et al., 2018 ). In such cases, the marginal utility of additional international mobility could be decreasing. It is equally possible that sojourns abroad after graduation eclipse the signalling value of study-related stays abroad. Study abroad experience might also substitute other skills or signals. For example, students conveying negative signals, such as poor grades, might compensate their disadvantage through study abroad experience, and thus benefit more from studying abroad than students with good grades. This hypothesis, however, is not supported by initial evidence (Petzold, 2017b ). Theoretically, study abroad experience might also reinforce the signalling value of other personal features, and vice versa.

The effects of studying abroad may also vary depending on the likelihood of studying abroad. As the literature on economic returns to studying (abroad) illustrates, there are conflicting hypotheses in this regard: From a classical economic standpoint, the rationally acting and utility-maximising homo oeconomicus should invest in those educational options that are most likely to increase lifetime earnings. Therefore, those individuals who are most likely to study (abroad) should also benefit most from it (Willis & Rosen, 1979 ). In contrast, the sociological perspective highlights that social norms and opportunity structures influence the likelihood of studying (abroad) as much as rational cost-benefit considerations do (Brand & Xie, 2010 ). Moreover, contrary to individuals with a low likelihood of studying (abroad), individuals with a high likelihood of studying (abroad) might have good job prospects even if they do not study (abroad). In support of the sociological perspective, existing evidence suggests that students with a lower propensity to study abroad are more likely to benefit from it regarding their job prospects (Waibel et al., 2018 , 2020 ).

From a classical sociological standpoint, it is also relevant to explicitly analyse differences in the effect of studying abroad depending on students’ adherence to specific socio-demographic groups, as defined by ascribed characteristics such as their gender, migration background, and social origin. As shall be illustrated regarding social origin, this social stratification perspective also allows for competing scenarios: On the one hand, students from a high social origin could benefit more from studying abroad. They tend to be better equipped with material and cultural resources allowing them to profit from education (Savage & Egerton, 1997 ). Moreover, their habitus and capital endowments may allow them to better valorise their experiences and credentials in the labour market (Laurison & Friedman, 2016 ). On the other hand, students from a low social origin could benefit more. Considering that they are less likely to gain the skills and signals acquirable through studying abroad during their earlier life course, studying abroad could induce a compensatory levelling process (Schafer et al., 2013 ). Furthermore, students from a low social origin may be positively selected in terms of motivation and productivity characteristics, which could positively influence their likelihood of studying abroad and their later potential to capitalise on it. As they usually have to overcome higher financial and social burdens, they might solely decide to study abroad if they are strongly convinced of reaping its benefits (Waibel et al., 2020 ). Footnote 3

The effects of studying abroad are also likely to be context-specific. This means that stays abroad tend to result in different outcomes depending on the surroundings in which individuals live, study, or work. For example, the value of stays abroad will likely vary depending on students’ field of study (Nerlich, 2021 ). Studying abroad may be more relevant for academic development in modern languages and cultural sciences than, for instance, in chemistry. Its value may even vary depending on specific curricula within fields of study.

There is further reason to assume that graduates’ working contexts moderate the effects of studying abroad. The employment sector may moderate the effects of studying abroad in that private companies tend to remunerate study abroad experience more than public authorities (Wiers-Jenssen, 2011 ). Public-sector wage schemes are usually more rigid and can less flexibly reward additional assets such as study abroad experience. Its value may also vary across labour market segments: The value of study abroad experience may be higher in vocationally unspecific segments, in which graduates of fields such as the humanities, social sciences, and economics tend to work, than in vocationally specific segments, in which graduates of fields such as medicine and teaching tend to work (Kratz & Netz, 2018 ; Waibel et al., 2018 ). The reason could be that the rules of career success are more strictly regulated in vocationally specific segments, so that add-on signals are less valuable. Moreover, study abroad experience seems to pay off particularly when graduates work for multinational employers (Petzold, 2017a ; Wiers-Jenssen & Try, 2005 ). Eventually, the value of study abroad experience may largely depend on the working tasks that graduates complete on a daily basis.

The effects of studying abroad may further vary across the country of study, work, and living. To some extent, national differences regarding the already discussed features of study environments and working contexts may explain cross-country variation. Beyond that, there may be differences in the extent to which national higher education systems reward study abroad experience. So far, however, most internationally comparative studies have focused on differences in the labour market effects of studying abroad depending on the structure of national economies. These studies suggest that labour market returns to studying abroad tend to be highest in Southern and Eastern European countries, moderate in Central European countries, and smallest or even non-existent in Northern European countries (Humburg & van der Velden, 2015 ; Jacob et al., 2019 ; Rodrigues, 2013 ; Teichler, 2011 ; Van Mol, 2017 ). Adding to country-specific explanations (e.g. Van Mol, 2017 ), Jacob et al. ( 2019 ) suggest that “returns to international study experience in terms of hourly wage and class position [are] larger in countries with poorer university quality, lower international trade volume, higher graduate unemployment, and with relatively few students going abroad” (p. 500). Footnote 4

Besides structural features of higher education systems and economies, national policies may influence the effects of studying abroad, e.g. through programmes trying to attract internationally experienced graduates. Furthermore, various cultural idiosyncrasies—as defined e.g. by the national social system, prevalent religion and gender roles, openness to foreigners, degree of urbanisation, and official language(s)—might moderate the effects of studying abroad. In these respects, internationally comparative research is still in its infancy.

Regarding treatment heterogeneity, various facets of stays abroad are relevant from both theoretical and policy perspectives. The first facet is the duration of the stay abroad. Arguably, effects of studying abroad are—on average—less likely to manifest following very short stays of just a few days or weeks than following longer stays of several months or years (Dwyer, 2004 ). Some authors presume that the effect of studying abroad rises linearly with the time spent abroad. For example, Medina-López-Portillo ( 2004 ) “suggests that the longer the program, the more interculturally sensitive students are likely to become” (p. 185). It is equally possible that the learning curve and thus the marginal utility decrease with the time spent abroad, so that the relationship would follow a logarithmic pattern. Some evidence on the labour market effects of studying abroad is even in line with an inverted U-shape pattern, suggesting that the signalling value of stays abroad may first increase but then decrease again with rising duration. For instance, Rodrigues ( 2013 ) reports that studying abroad for three to 12 months yields a moderate wage premium, while studying abroad for less than three or more than 12 months yields no significant wage returns. Yet other studies report no effect heterogeneity depending on the time spent abroad. For instance, Schmidt and Pardo ( 2017 ) find no significant differences in the wage effects of 3-to-4 weeks as opposed to full-terms abroad.

The duration closely relates to the purpose of a stay abroad, which emphasises its function for competence development. For example, entire degrees and study periods abroad are likely to foster academic and generic intercultural skills, internships should help students acquire human capital that is particularly relevant professionally, and language courses may be most effective in improving language proficiency. Research comparing the effects of study periods and internships abroad concludes that internships abroad pay off slightly more in the labour market (Kratz & Netz, 2018 ; Van Mol, 2017 ). Footnote 5 A specific discussion revolves around the question of whether studying abroad entirely or partly is most beneficial. Evidence from Norway suggests that wage returns are higher for entire degrees than for study periods completed abroad (Wiers-Jenssen, 2011 ; Wiers-Jenssen & Try, 2005 ). In contrast, evidence from several (other) European countries suggests that employers prefer graduates who partly studied abroad over those who entirely studied abroad (Humburg & van der Velden, 2015 ). Ultimately, the extent to which graduates need general and country-specific human capital for their daily working life will be decisive in this respect.

An even more explicit focus on students’ actual activities is beneficial as well. Not least due to lacking standard criteria for evaluating the quality of stays abroad and of corresponding data, (quantitative) scholars have so far mostly treated stays abroad as black boxes concerning students’ activities. Logically, the quality of the coursework or work assignments matters. High-quality courses and ambitious assignments will likely influence the development of academic and professional skills more positively than sojourns that largely resemble touristic stays. Besides academic and professional activities, extracurricular activities may have a substantial bearing on the outcomes of studying abroad (Gozik & Oguro, 2020 ). In academic, professional, and extracurricular terms, students’ social contacts and the degree of immersion in their host culture also seem to play a vital role. For instance, establishing new relationships abroad is an essential catalyst for the positive effects of studying abroad on personality development (Zimmermann & Neyer, 2013 ). Similarly, intense interaction with host-country nationals is particularly important for improving oral foreign language proficiency (Engle & Engle, 2004 ; Jackson et al., 2020 ; Magnan & Back, 2007 ).

In this respect, the organisation of stays abroad comes into play. For instance, students’ housing arrangement—that is, whether they live in a host family, student residence, or off-campus apartment either with co-nationals, other non-nationals, host-country nationals, mixed groups, or alone—has received considerable attention in the study abroad literature. Regarding gains in language proficiency and other intercultural skills, however, the housing arrangement alone does not seem to be very predictive (Gozik & Oguro, 2020 ; Jackson et al., 2020 ). Rather, the previously discussed activities seem to matter. Moreover, a solid but not excessive level of student support, including pre-sojourn administrative and academic preparation, organisational support in the host country, post-sojourn follow-up reflection, and credit recognition can help students reap the benefits of studying abroad (Gozik & Oguro, 2020 ; Norris & Dwyer, 2005 ). Participation in specific study abroad programmes, as opposed to self-organised stays, may also influence the outcomes of studying abroad. Different programmes and self-organised stays abroad could either reflect the previously discussed types of treatment heterogeneity or have an unequal signalling value due to more or less restrictive or non-existent eligibility criteria. Footnote 6

The effects of studying abroad will arguably also depend on the host institution. Host universities and employers offering high-quality education, support, or working conditions should bring about better outcomes than institutions offering poor opportunity structures. In line with this view, there is evidence that European employers regard the prestige of graduates’ (host) universities during hiring processes as a signal of graduates’ level of skill acquisition (Humburg & van der Velden, 2015 ).

If employers cannot appraise the quality of graduates’ host institution, they may also draw on their own assumptions or factual information about the host country. For instance, stays in countries with effective higher education systems may signal high-quality learning experiences. Stays in countries with prosperous economies may signal the acquisition of professionally relevant skills. And stays in culturally exclusive countries may enable social distinction. Although only loosely linked to these theoretical thoughts, there is initial evidence on the labour market effects of sojourning in specific host countries: Examining graduates from institutions in Spain, Iriondo ( 2020 ) reports that wage returns to participation in the Erasmus programme are highest for stays in Germany, followed by stays in France, the Nordic countries, and the UK. Stays in countries such as Italy and Portugal do not seem to yield significant wage returns. Concentrating on returns to language acquisition rather than stays in specific host countries, Sorrenti ( 2017 ) reports that proficiency in German yields the highest wage returns for graduates from Italy, followed by proficiency in English, French, and Spanish. While there is some overlap between these findings, they also suggest that the value of stays in specific countries varies depending on graduates’ home country—and arguably also depending on various other factors, including the specific career that graduates intend to pursue.

Finally, temporality matters for analysing the outcomes of studying abroad. Methodologically, it is useful to differentiate age, period, and cohort effects (Winship & Harding, 2008 ). Age effects could result from the timing at which a stay abroad is completed. For instance, a stay abroad close to graduation might have stronger effects on the likelihood of employment than a stay abroad shortly after entering higher education. The former could help students broaden their professional networks and gain valuable information for their upcoming job search. In turn, an early stay abroad might have more substantial effects on academic development. Moreover, what matters is the point in graduates’ careers when we measure the outcomes of studying abroad. Existing evidence suggests that specific labour market effects of studying abroad may take several years to unfold (Netz & Cordua, 2021 ). A reason could be that the competences acquired through studying abroad cannot be applied immediately in many labour market entry positions.

Period effects would find their expression in a changing value of study abroad experience over time. Teichler and Janson ( 2007 ) suggest that the self-perceived professional value of Erasmus study abroad experience may have decreased between the late 1980s and 2005 with the increasing share of students studying abroad. While the scarcity value of study abroad experience has certainly decreased, it is equally possible that the skills acquired through studying abroad have become more relevant in continuously globalising labour markets.

Cohort effects are characterised by common events experienced by specific groups. For instance, the 2020 and 2021 graduation cohorts may not have been able to readily capitalise on possible study abroad experience because of hiring freezes and limited international cooperation in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. This may translate to long-term disadvantages (scarring effects) for these cohorts.

As already indicated, different types of effect heterogeneity may interact—or rather define an outcome in conjunction. For instance, we might observe different effects of studying abroad across social groups partly because different groups are more or less likely to work in specific labour market segments, where study abroad experience is either more or less remunerated. This pattern could also result from different social groups completing different stays abroad. Whether different study abroad treatments produce divergent effects may depend on the country of work/living. Finally, as time and space features are not separable, the discussed age, period, and cohort effects will always be defined by individual or group-specific effects, context-specific effects, and treatment heterogeneity. Clearly, it is difficult to empirically disentangle different types of effect heterogeneity using currently available data and methods. Still, their conceptual differentiation is vital for appropriate hypothesis testing and for pinpointing effective policy recommendations.

Articles of the special issue

The articles of this special issue engage with the developed research agenda. In doing so, they each contribute a unique analytical perspective by accentuating specific disciplinary angles, corresponding theoretical and methodological approaches, country contexts, outcomes of studying abroad, and types of effect heterogeneity.

The articles have their roots in psychology, economics, and sociology. Relatedly, they use diverse theoretical approaches (theories of personality traits, experiential learning, rational choice, human capital, signalling, statistical discrimination, social capital, and social stratification) and statistical methods (linear and multinomial logistic regressions, latent change models, multilevel models, growth curve models, and propensity score matching). They cover Anglo-Saxon, Continental and Southern European, and Scandinavian countries (UK, Germany, The Netherlands, Italy, and Norway). They focus on different outcomes of studying abroad (multicultural self-efficacy, metacognitive intercultural competence, intergroup anxiety, uptake of postgraduate education, job search duration, likelihood of employment, skills mismatch, and labour income). Thereby, they also explore the effects of studying abroad in different life course stages (during studies, the transition from higher education to work, and the early professional career). Finally, they consider a variety of the above-mentioned types of effect heterogeneity. These include individual or group-specific effects (contingent on pre-mobility values of specific dependent variables, alternative skills and signals, the likelihood of studying abroad, and the adherence to specific socio-demographic groups), context-specific effects (as defined by the study environment, working context, and country of work), treatment heterogeneity (depending on the purpose, organisation, and host country of stays abroad), and aspects of temporality (point during studies when a stay abroad was completed, point in career when its effect was measured, and graduation year).

The articles also have commonalities: In response to repeated calls for better approximations of causal effects of studying (e.g. Netz & Cordua, 2021 ; Waibel et al., 2017 ; Wiers-Jenssen et al., 2020 ), all articles employ statistical techniques that can reduce the bias resulting from the selective participation in ISM. Thereby, they also contribute to integrating the still often disconnected research streams on the determinants and on the effects of studying abroad. Moreover, they either use large-scale and mostly nationally representative observational data or experimental data to ensure the validity of the generated results. Some studies examine the same countries, types of stays abroad, outcomes, or types of effect heterogeneity. This allows for rough comparisons of their results.

In the first article, Julia Zimmermann , Henriette Greischel , and Kathrin Jonkmann ( 2020 ) examine the influence of studying abroad on different facets of multicultural effectiveness. Based on psychological theories of personality traits and experiential learning, they reason that studying abroad should increase multicultural self-efficacy as well as metacognitive intercultural competence and decrease intergroup anxiety. They also assume that these effects vary depending on selected socio-demographic characteristics and students’ previous international mobility. They test their hypotheses based on a countrywide purposive sample of students at higher education institutions in Germany, whom they surveyed three times during their studies. Using latent change models, they find evidence supporting their theoretical assumptions: Studying abroad slightly increases self-perceived multicultural self-efficacy and metacognitive intercultural competence. Moreover, it slightly lowers intergroup anxiety. Importantly, these developmental patterns do not vary depending on students’ socio-demographics—as defined by their gender, age, migration background, and parents’ professional qualification. However, students benefit most from studying abroad regarding the development of multicultural effectiveness when they are internationally mobile for the first time.

In the second article, Knut Petzold ( 2020 ) addresses the relevance of study abroad experience during hiring processes. Following economic theories of human capital, job market signalling, and statistical discrimination, he examines how the importance that human resource managers attach to studying abroad varies depending on the purpose and timing of stays abroad, graduates’ socio-demographic features, their other human capital characteristics, and the (inter)national orientation of employers. He bases his analysis on a factorial survey experiment administered to a purposive sample of German employers. Estimating multilevel models, he finds suggestive evidence that employers consider internships the most valuable (arguably because they generate the most specific human capital), followed by study periods and non-educational private stays abroad. Graduates with a migration background benefit less from study periods and private stays abroad than graduates without such a background, possibly because a migration background already signals transnational human capital. Also, Master graduates benefit less from study periods and internships abroad because they may already have more general and specific human capital than Bachelor graduates. Finally, employers value study abroad experience (insignificantly) more if they have a foreign branch, which could indicate a relatively higher value of transnational human capital for multinational employers.

In the third article, Jannecke Wiers-Jenssen and Liv Anne Støren ( 2020 ) explore whether studying abroad affects the risk of unemployment and skills mismatch about six months after graduation. Following theories of human capital and signalling, they hypothesise that this risk differs depending on graduates’ socio-demographics and working context. They test their hypotheses based on data from the Norwegian graduate survey. These data cover six graduation cohorts, who completed their studies between 2007 and 2017. Their multinomial logistic regressions show that most differentiated graduate groups do not differ significantly in their risk of unemployment and skills mismatch depending on whether they have studied abroad. However, they find that studying abroad reduces this risk among graduates of business and administration, who tend to work in the private sector. They conclude that their results contradict the hypothesis that study abroad experience pays off mainly among graduates of vocationally unspecific fields. Furthermore, they find that studying abroad reduces the risk of unemployment and skills mismatch particularly among graduates with high intake grades. They do not observe effect heterogeneity depending on the social origin or migration background. Therefore, they conclude that their results also contradict the hypothesis that those less likely to study abroad profit more from it.

In the fourth article, Christof Van Mol , Kim Caarls , and Manuel Souto-Otero ( 2020 ) assess the effect of studying abroad on the duration of the transition from higher education to work and on the monthly wage at 1.5 years after graduation. Starting from theoretical thoughts on human capital, signalling, and international prestige hierarchies of higher education systems and labour markets, they look at effect heterogeneity depending on the study level (Bachelor vs. Master), purpose of a stay abroad (study period vs. internship vs. both), and educational and economic features of students’ host countries. They test their hypotheses based on nationally representative graduate survey data from the Netherlands. Using linear regressions, they observe that the examined labour market effects of studying abroad vary slightly across study levels, purposes of stays abroad, and host countries. Against expectations, however, the observed effects and corresponding heterogeneity largely disappear after stricter controls for selection effects through propensity score matching. Also contrary to expectations, sojourns in countries with well-performing higher education systems come along with a longer duration of job search, possibly because students staying in such countries take more time to find jobs matching their high aspirations. Overall, the authors conclude that the well-performing higher education system and labour market in the Netherlands restrict graduates’ potential to further improve their labour market prospects through studying abroad.

In the fifth article, Béatrice d’Hombres and Sylke Schnepf ( 2021 ) examine the effect of studying abroad on the likelihood of postgraduate education and of employment in the first years after graduation. Referring to human capital, signalling, and social capital theories, they compare these labour market effects of studying abroad across countries and socio-economic groups. They draw on large-scale graduate survey data from Italy and the UK to test their hypotheses. In line with theory, their matching analyses indicate that studying abroad correlates with a greater likelihood of postgraduate education among graduates in Italy. They do not observe this link among graduates in the UK. The effect of studying abroad on the likelihood of employment is significantly positive both one and four years after graduation in Italy. In the UK, it is significantly positive six months after graduation and insignificant three years after graduation. Thus, the examined labour market returns to studying abroad are higher in Italy than in the UK. Against expectations, the effects of studying abroad on the likelihood of employment do not differ significantly across socio-economic groups. However, the effect of studying abroad on the likelihood of postgraduate education is larger among graduates from a low socio-economic background than among those with a high socio-economic background in Italy.

In the last article, Nicolai Netz and Michael Grüttner ( 2020 ) provide a sociological analysis of the relationship between studying abroad and the generation of social inequality. Drawing on social stratification theory, they argue that a scenario in which ISM increases social inequality (because graduates from an academic background benefit from cumulative advantages) is as plausible as a scenario in which ISM decreases social inequality (because graduates from a non-academic background benefit from compensatory levelling). Following these thoughts, they test whether the effect of studying abroad on labour income varies across social groups in the German labour market. Their study is based on nationally representative survey data capturing the first ten years of graduates’ careers, which they analyse using propensity score matching and random effects growth curve models. In line with the scenario of cumulative advantage, their results suggest that graduates from an academic background benefit more from studying abroad than graduates from a non-academic background. Considering that students from an academic background are also more likely to study abroad in the first place, they conclude that ISM fosters the reproduction of social inequality. They also find that the estimated returns to studying abroad are highest among those with the lowest propensity to study abroad. However, this pattern seems to be driven by the results for graduates from an academic background.

Taken together, the articles of the special issue provide a comprehensive answer to the question of who benefits most from studying abroad. At the same time, they clearly indicate a need for further research. Some major findings and directions for future research are highlighted in the concluding section.

Summary and conclusions

It is beyond the scope of this editorial to comprehensively summarise the wealth of empirical evidence that the articles of the special issue provide. However, the following lines highlight a few overarching themes.

To begin with, all contributions to the special issue illustrate that studying abroad has only moderate effects on the examined outcomes—if compared to other critical life events, skills, and signals. They equally demonstrate that the benefits of studying abroad are often confined to specific groups of students and graduates, contexts, and types of stays abroad. Consequently, they justify the initial claim that research on ISM should devote more attention to effect heterogeneity.

Additionally, the articles highlight the importance of adopting a life course perspective. This perspective does not only help scholars trace group-specific patterns of selection into study abroad experience. It also emphasises that specific groups of students may build up cumulative advantages or disadvantages over their life course due to (even minor) heterogeneous effects of studying abroad (Zimmermann et al., 2020 ). The life course perspective also stresses the importance of other aspects of temporality: Although further research is needed in this respect, there is evidence that the timing of a stay abroad matters (Petzold, 2020 ; Van Mol et al., 2020 ). Moreover, the effect of studying abroad seems to vary over graduates’ careers: Country differences notwithstanding, the labour market effects of studying abroad—especially with regard to labour income—seem to be more pronounced a few years after graduation than shortly thereafter (d’Hombres & Schnepf, 2021 ; Netz & Grüttner, 2020 ; Van Mol et al., 2020 ; Wiers-Jenssen & Støren, 2020 ).

Furthermore, the contributions to the special issue have produced evidence of diminishing marginal returns of gaining additional international experience. For instance, gains in multicultural effectiveness are particularly notable among students without previous sojourns abroad (Zimmermann et al., 2020 ). Also, graduates who can signal transnational human capital in other ways are less likely to benefit from studying abroad in terms of their probability of being hired (Petzold, 2020 ).

To further advance our knowledge on (heterogeneous) effects of studying abroad, we need panel data covering longer time frames. These data should ideally describe individuals’ life courses starting at early ages and throughout their entire educational and professional career. Such data would not only allow us to answer questions that are inherently longitudinal in nature, but also to integrate ISM research rooted in different disciplines and research communities. This would enable a shift from multidisciplinary to interdisciplinary research on the effects of studying abroad. For instance, it would be relevant to examine how differential changes in personality traits and intercultural competences due to study abroad experience translate into group-specific labour market outcomes. Answering such questions would also provide more knowledge about the mechanisms that can explain the observed heterogeneity in the effects of studying abroad.

Additionally, long-running panel data would bring about methodological advances: They would enable the application of statistical techniques allowing for better approximations of causal effects of studying abroad. At present, many surveys limit analyses of heterogeneous outcomes of studying abroad because they address individuals only after graduation. This limitation of graduate surveys explains the relative popularity of matching approaches, which cannot capture selection into study abroad experience based on unobserved characteristics. A fruitful complement to the extension of survey data would be the more frequent use of experimental designs in research on ISM.

Besides age effects, period effects and cohort effects warrant further attention in research on ISM. Once the required panel data are available for multiple student and graduate cohorts, scholars could examine whether the effects of studying abroad have changed over time. For instance, we still lack robust analyses testing the hypothesis that the labour market returns to studying abroad have declined over the past decades as a result of ISM becoming less exclusive (see also Waibel et al., 2017 ). Footnote 7

In line with previous evidence on occupational status benefits of studying abroad (Waibel et al., 2018 , 2020 ), evidence on the wage effects of studying abroad presented in this special issue confirms the tendency that those with a low propensity to study abroad benefit more from studying abroad than those with a high propensity to study abroad (Netz & Grüttner, 2020 ). However, it is noteworthy that all existing studies refer to graduates in the German labour market. Thus, further evidence is needed from other countries.

The findings are far less straightforward concerning effect heterogeneity depending on the social origin. In Italy, students from lower socio-economic backgrounds benefit more from studying abroad in terms of foreign language acquisition (Sorrenti, 2017 ) and the likelihood of postgraduate education (d’Hombres & Schnepf, 2021 ). Regarding the employment likelihood a few years after graduation, analyses of the returns to studying abroad report either no significant group differences (d’Hombres & Schnepf, 2021 ) or comparatively high returns for graduates from intermediate social backgrounds (Di Pietro, 2015 ). In Norway, the influence of studying abroad on graduates’ early-career risk of unemployment and skills mismatch does not vary significantly depending on parents’ educational attainment (Wiers-Jenssen & Støren, 2020 ). Similarly, Zimmermann et al. ( 2020 ) do not find significant differences by parents’ professional qualifications in the effect of studying abroad on multicultural effectiveness among students in Germany. However, wage returns to studying abroad are higher among graduates from an academic background in the German labour market (Netz & Grüttner, 2020 ). In Poland, too, graduates from an academic background benefit most from studying abroad in terms of the employment probability (Liwiński, 2019a ).

Concerning the migration background, the effect of studying abroad on multicultural effectiveness does not vary significantly in Germany (Zimmermann et al., 2020 ). Similarly, the effect of studying abroad on the risk of unemployment and skills mismatch does not vary significantly depending on whether graduates have a migration background in Norway. However, graduates with a migration background seem to benefit slightly less from study periods and private stays abroad regarding the propensity of being hired in Germany (Petzold, 2020 ). In summary, existing evidence on heterogeneous effects of studying abroad depending on socio-demographics is thus mixed. Footnote 8

Furthermore, there is conflicting evidence regarding the hypothesis that study abroad experience pays off more in vocationally unspecific than in vocationally specific labour market segments. Evidence from Germany concerning the influence of studying abroad on occupational status (Waibel et al., 2018 ) and on labour income (Kratz & Netz, 2018 ; Netz & Grüttner, 2020 ) supports this hypothesis. However, Wiers-Jenssen and Støren ( 2020 ) find no evidence of this pattern regarding the risk of unemployment and skills mismatch in Norway.