- Get started with computers

- Learn Microsoft Office

- Apply for a job

- Improve my work skills

- Design nice-looking docs

- Getting Started

- Smartphones & Tablets

- Typing Tutorial

- Online Learning

- Basic Internet Skills

- Online Safety

- Social Media

- Zoom Basics

- Google Docs

- Google Sheets

- Career Planning

- Resume Writing

- Cover Letters

- Job Search and Networking

- Business Communication

- Entrepreneurship 101

- Careers without College

- Job Hunt for Today

- 3D Printing

- Freelancing 101

- Personal Finance

- Sharing Economy

- Decision-Making

- Graphic Design

- Photography

- Image Editing

- Learning WordPress

- Language Learning

- Critical Thinking

- For Educators

- Translations

- Staff Picks

- English expand_more expand_less

Critical Thinking and Decision-Making - Logical Fallacies

Critical thinking and decision-making -, logical fallacies, critical thinking and decision-making logical fallacies.

Critical Thinking and Decision-Making: Logical Fallacies

Lesson 7: logical fallacies.

/en/problem-solving-and-decision-making/how-critical-thinking-can-change-the-game/content/

Logical fallacies

If you think about it, vegetables are bad for you. I mean, after all, the dinosaurs ate plants, and look at what happened to them...

Let's pause for a moment: That argument was pretty ridiculous. And that's because it contained a logical fallacy .

A logical fallacy is any kind of error in reasoning that renders an argument invalid . They can involve distorting or manipulating facts, drawing false conclusions, or distracting you from the issue at hand. In theory, it seems like they'd be pretty easy to spot, but this isn't always the case.

Watch the video below to learn more about logical fallacies.

Sometimes logical fallacies are intentionally used to try and win a debate. In these cases, they're often presented by the speaker with a certain level of confidence . And in doing so, they're more persuasive : If they sound like they know what they're talking about, we're more likely to believe them, even if their stance doesn't make complete logical sense.

False cause

One common logical fallacy is the false cause . This is when someone incorrectly identifies the cause of something. In my argument above, I stated that dinosaurs became extinct because they ate vegetables. While these two things did happen, a diet of vegetables was not the cause of their extinction.

Maybe you've heard false cause more commonly represented by the phrase "correlation does not equal causation ", meaning that just because two things occurred around the same time, it doesn't necessarily mean that one caused the other.

A straw man is when someone takes an argument and misrepresents it so that it's easier to attack . For example, let's say Callie is advocating that sporks should be the new standard for silverware because they're more efficient. Madeline responds that she's shocked Callie would want to outlaw spoons and forks, and put millions out of work at the fork and spoon factories.

A straw man is frequently used in politics in an effort to discredit another politician's views on a particular issue.

Begging the question

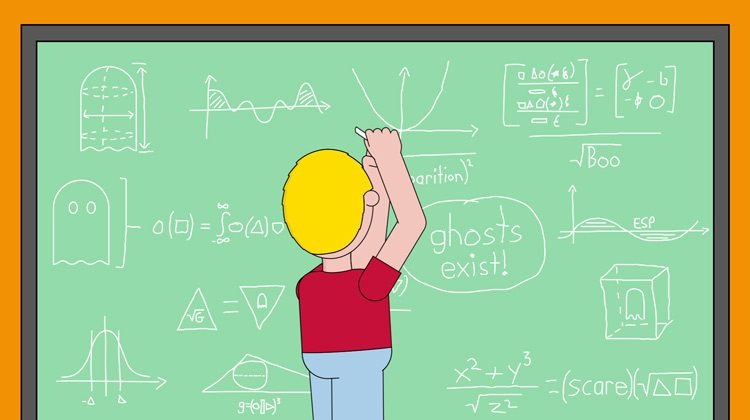

Begging the question is a type of circular argument where someone includes the conclusion as a part of their reasoning. For example, George says, “Ghosts exist because I saw a ghost in my closet!"

George concluded that “ghosts exist”. His premise also assumed that ghosts exist. Rather than assuming that ghosts exist from the outset, George should have used evidence and reasoning to try and prove that they exist.

Since George assumed that ghosts exist, he was less likely to see other explanations for what he saw. Maybe the ghost was nothing more than a mop!

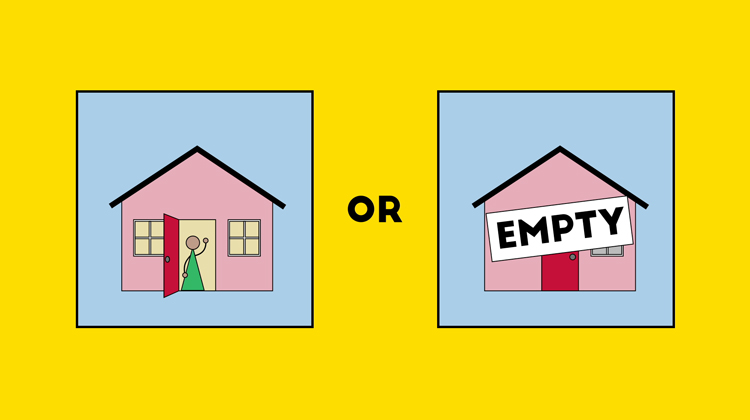

False dilemma

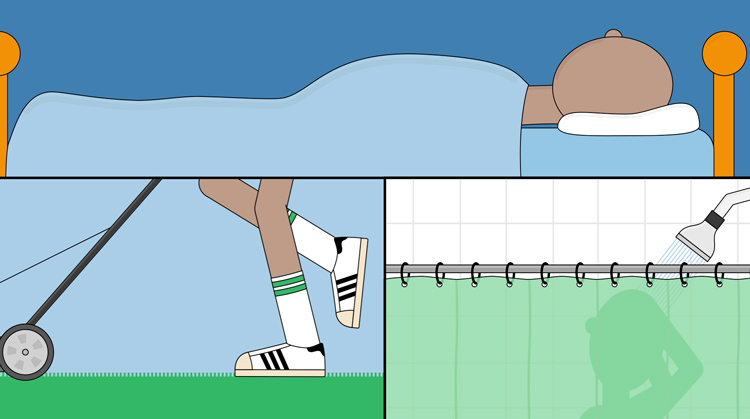

The false dilemma (or false dichotomy) is a logical fallacy where a situation is presented as being an either/or option when, in reality, there are more possible options available than just the chosen two. Here's an example: Rebecca rings the doorbell but Ethan doesn't answer. She then thinks, "Oh, Ethan must not be home."

Rebecca posits that either Ethan answers the door or he isn't home. In reality, he could be sleeping, doing some work in the backyard, or taking a shower.

Most logical fallacies can be spotted by thinking critically . Make sure to ask questions: Is logic at work here or is it simply rhetoric? Does their "proof" actually lead to the conclusion they're proposing? By applying critical thinking, you'll be able to detect logical fallacies in the world around you and prevent yourself from using them as well.

Logical Fallacies

Definition of a 'fallacy'.

A misconception resulting from flaw in reasoning, or a trick or illusion in thoughts that often succeeds in obfuscating facts/truth.

A formal fallacy is defined as an error that can be seen within the argument's form. Every formal fallacy is a non sequitur (or, an argument where the conclusion does not follow from the premise.)

An informal fallacy refers to an argument whose proposed conclusion is not supported by the premises. This creates an unpersuasive or unsatisfying conclusion.

What are Logical Fallacies?

Logical fallacies are errors in reasoning or argumentation that can undermine the validity of an argument. They are often used to mislead or distract from the truth, or to win an argument by appealing to emotions rather than reason. It's important to be aware of these fallacies in order to critically evaluate arguments and avoid being misled.

These mistakes in reasoning can be both intentional and unintentional, often leading to false or misleading conclusions. They undermine the strength and credibility of an argument, making it difficult to persuade others or arrive at accurate judgments.

There are two main types of logical fallacies: formal and informal. Formal fallacies involve errors in the structure or form of an argument, while informal fallacies arise from errors in the content, context, or delivery of the argument.

Logical fallacies can be difficult to identify, as they often involve seemingly reasonable arguments that, upon closer examination, reveal underlying flaws. To avoid falling prey to logical fallacies, it is essential to develop critical thinking skills and a solid understanding of the principles of logic and argumentation. By doing so, one can more effectively evaluate arguments and engage in rational discourse, leading to more accurate and reliable conclusions. | More

Books About Logical Fallacies

A few books to help you get a real handle on logical fallacies.

Logical Fallacies (Common List + 21 Examples)

We all talk, argue, and make choices every day. Sometimes, the things we or others say can be a bit off or don't make complete sense. These mistakes in our thinking can make our points weaker or even wrong.

Logical fallacies are mistakes in how we reason or argue a point. They can be small mix-ups or times when someone tries to trick us on purpose.

By learning about these errors, you can better spot them when you hear or read them. As you read on, you'll learn more about these tricky mistakes and how to steer clear of them.

Introduction to Logical Fallacies

Imagine you're piecing together a puzzle. Each piece needs to fit perfectly for the whole picture to make sense. In conversations and debates, our arguments are like those puzzle pieces. They need to fit well together, making our points clear and strong.

However, sometimes, a piece might be bent or out of place, making the whole picture a bit off. That's how logical fallacies work in our discussions. They're like those misfit puzzle pieces that can make our whole argument seem less clear or even wrong.

Logical fallacies, in simple terms, are errors or mistakes in our reasoning. You might come across them when you're chatting with a friend, watching the news, or even reading a book.

Some of these mistakes happen because we don't know better, while others might be used intentionally to mislead or persuade.

Let's say you're discussing which ice cream flavor is the best. Your friend might say, "Well, my grandma thinks vanilla is the best, so it must be!" This kind of reasoning isn't strong because one person's opinion, even if it's your grandma, doesn't prove a point for everyone.

This is an example of a fallacy called appeal to authority . It’s just one of the many logical fallacies you'll come across.

When we talk about logical fallacies, we often categorize them into two main types: informal and formal.

Informal Fallacies

Think of these as mistakes or errors in reasoning that arise from the content of the arguments rather than the structure.

They're called 'informal' because they deal with everyday language and common conversations. These fallacies often involve statements that might sound true initially, but upon closer inspection, they don't hold up.

Examples include the ad hominem argument or fallacy, where someone attacks the person rather than their argument, or the appeal to authority , where someone assumes a statement is true because an expert or authority says so.

Formal Fallacies

These are a bit more, well, formal. They deal with errors in the structure or form of an argument.

It doesn't matter what the content of the argument is; if it's structured wrongly, it's a formal fallacy. You can think of these like a math problem: if you don't follow the right steps, you won't get the right answer.

An example of a formal fallacy is the affirming the consequent , which goes like this: "If it rains, the ground will be wet. The ground is wet. Therefore, it rained." While the statements might sound logical, the conclusion doesn't necessarily follow from the premises.

In a nutshell, while informal fallacies stem from the content of arguments and often arise in casual conversations, formal fallacies are all about structure, and they can be spotted regardless of the topic being discussed.

All fallacies can be proven wrong because they have flawed reasoning or insufficient supporting evidence, make an irrelevant point, or don't have an actual argument. Even if it seems like they come to a logical conclusion, they do so in an illogical way.

Common Logical Fallacies

Let's look at some of the most common logical fallacy examples.

Ad Hoc Fallacy

This is a fallacy where someone makes up a reason on the spot to support their argument, even if it doesn't make sense.

Picture this: you're debating about climate change and its causes. Your friend, instead of using scientific evidence, says, "Well, it's just a cycle the Earth goes through. My grandpa said so!" This is an Ad Hoc Fallacy. The reason is made up on the spot and doesn't hold up to scrutiny.

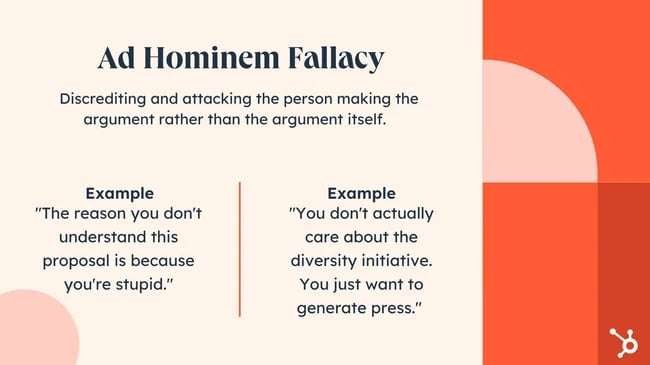

Ad Hominem Fallacy

This is when someone attacks the person instead of their argument.

Imagine you're chatting about which game is the best, and instead of giving reasons, someone says, "Well, you wear glasses so that you wouldn’t understand!" That's not a good reason, right?

Anecdotal Fallacy

An Anecdotal Fallacy occurs when someone relies on personal experiences or individual cases as evidence for a general claim, overlooking larger and more reliable data.

Appeal to Pity

An Appeal to Pity Fallacy is an argument that attempts to win you over by eliciting your sympathy or compassion rather than relying on logical reasoning.

Straw Man Fallacy

Here, someone changes or oversimplifies another person's argument to make it easier to attack. It's like building a weak version of the original point and then knocking it down.

Person A: "I think we should have more regulations on industrial pollution to protect the environment." Person B: "Why do you want to destroy jobs and hurt our economy by shutting down all industries?" In this case, Person A never said they wanted to shut down all industries, but Person B set up a "straw man" version of Person A's argument to knock it down.

Ecological Fallacy

An Ecological Fallacy occurs when you make conclusions about individual members of a group based only on the characteristics of the group as a whole.

- Bandwagon Fallacy

This one's about popularity. Just because many people believe something doesn't mean it's true.

Remember when everyone believed the earth was flat? Being popular doesn't always mean being right.

Loaded Question

A loaded question fallacy is a trick question that contains an assumption or constraint that unfairly influences the answer, leading you toward a particular conclusion.

Slippery Slope Fallacy

This is when someone says that if one thing happens, other bad things will follow without good reasons.

Like if someone says, "If we let kids have phones, next they'll want to drive cars at 10 years old!" It's a big jump without clear logic connecting the two.

False Cause Fallacy

This is thinking one thing causes another just because they happen together.

Like believing every time you wear a certain shirt, your team wins. It's fun to think about, but the shirt probably isn't the reason for the win.

Appeal to Probability

An Appeal to Probability Fallacy is a misleading reasoning technique that assumes if something is likely, it must be certain to happen.

Appeal to Authority Fallacy

We talked about this one earlier! Just because someone famous or important believes something doesn't make it true.

Hasty Generalization Fallacy

This is when someone makes a broad claim based on very limited evidence .

For instance, after seeing two movies with a particular actor and not liking them, you declare, "All movies with this actor are terrible."

False Dichotomy Fallacy

This fallacy occurs when someone presents only two options or solutions when more exist.

Example: "You're either with us, or you're against us." In reality, someone might be neutral or have a more nuanced opinion.

Proof Fallacy (Argument from Ignorance)

This is when someone assumes something is true because it hasn't been proven false or vice versa.

Example: "No one has ever proven that aliens don't exist, so they must be real."

Tu Quoque Fallacy

This fallacy points out hypocrisy as an argument against the claim. It's like saying, "You too!"

Example: "Why are you telling me not to smoke when you used to smoke?"

Post Hoc Fallacy ( Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc)

This fallacy assumes that if 'B' occurred after 'A', then 'A' must have caused 'B'.

Example: "I wore my lucky socks, and then passed my exam. My socks made me pass!"

No True Scotsman Fallacy

This fallacy happens when someone redefines a term to fit their own writing or argument or to exclude a counterexample.

Person A: "No Scotsman puts sugar in his porridge." Person B: "But my uncle Angus is a Scotsman, and puts sugar in his porridge." Person A: "Well, no true Scotsman puts sugar in his porridge."

Texas Sharpshooter Fallacy

This cognitive bias is when someone focuses on a subset of their data and ignores the rest to make a point.

Looking at a large set of data and only selecting the bits that support your claim, like a shooter firing randomly at a barn wall, then painting a target around the shots that are closest together.

Middle Ground Fallacy

Middle Ground is the belief that a compromise between two conflicting positions must be the truth or the best solution.

Red Herring Fallacy

This fallacy introduces an irrelevant topic to distract from the original argument.

For instance, when asked about pollution levels, a politician says, "We have some of the best parks in the country, and our citizens love spending time in nature."

False Analogy Fallacy

Any time someone says "X is like Y" to compare one thing with something else that isn't the same but does share similarities, they're making a false analogy .

For instance, saying cars and bicycles are the same because they both have wheels is an oversimplification.

Circular Reasoning Fallacy

This logical fallacy makes the mistake of using a claim to support itself . A is true because B is true.

Perhaps you've seen a commercial claiming a product is the best because so many people buy it. But when pressed on how they know so many buy it, they respond because the product is the best.

Accident Fallacy

An Accident Fallacy is the misuse of a general rule by applying it to a specific case it doesn’t properly address.

Begging the Question Fallacy

A begging-the question-fallacy occurs when the argument's conclusion is assumed in its premise. In other words, it's a form of circular reasoning where the thing you're trying to prove is already assumed to be true.

- Appeal to Ignorance

An Appeal to Ignorance Fallacy occurs when someone argues that a claim is true simply because it has not been proven false, or vice versa.

Fallacy of Composition

A fallacy of composition is the flawed reasoning that concludes what is true for individual parts must also be true for the entire group or system they belong to.

Equivocation Fallacy

An equivocation fallacy occurs when a word or phrase is used with two meanings in the same argument, leading to confusion or a misleading conclusion.

Naturalistic Fallacy

A naturalistic fallacy , also known as the appeal to nature fallacy, comes to a false conclusion by assuming that everything in nature is moral and right.

Why Do We Fall for Fallacies?

Everyone, at some point, has believed in something that turned out to be not entirely true. Just like when we believe in myths or fairy tales , there's something in our brains that can sometimes make us accept ideas without fully questioning them. This is where logical fallacies sneak in.

Firstly, our brains love shortcuts . These shortcuts, called heuristics , help us make decisions faster.

For example, if you've always had great pizza from a particular restaurant, the next time you think of pizza, your brain will likely suggest that place.

But shortcuts can also lead us astray. If someone speaks confidently, our brains might take a shortcut and believe them, even if what they're saying has mistakes.

Secondly, emotions play a big role . We're humans, after all! If someone tells a sad story, we might feel so touched that we don't stop to think if the story proves the point they're making.

Or if everyone in our group believes something, we might feel the need to fit in and believe it too. This is known as groupthink , a classic trap many fall into.

Lastly, sometimes it's just easier . Questioning everything and thinking critically can be tiring. So, there are moments when we might accept something because it's simpler or because we don't want to start an argument.

But here's the good news: by learning about logical fallacies and understanding why we sometimes fall for them, you can train your brain to spot and avoid these traps.

The History of Logical Fallacies

Back in the day, long before smartphones and computers, people gathered and debated big ideas in places like Greece. One of the smartest guys around then was a man named Aristotle . He's often thought of as the first person who cared about logical thinking.

Aristotle started to notice that some arguments, even if they sounded good, had problems in them. He began to point out these mistakes and gave them names. Many of the fallacies he talked about are still recognized today!

After Aristotle, many other thinkers also became interested in how we argue and reason. They noticed that these mistakes, or fallacies, weren't just random errors. They followed patterns.

Fast forward to modern times, and this study hasn't stopped. It's become even more important.

Today, with information everywhere - on TV, the internet, and social media - it's crucial to sort out what's reliable from what's not . Teachers, writers, and even politicians study logical fallacies to communicate better and avoid misleading people.

Basic Argument Structure

A good argument is built piece by piece, ensuring each is supported by the other. Understanding how arguments are put together helps you spot when a part of the argument doesn't make sense.

At the heart of any argument are two main parts: premises and conclusions .

Think of the premises as the foundation of the argument. They're the facts or reasons you give. The conclusion is the point you're trying to make based on those reasons.

Let's use a simple example. Imagine you say:

- All dogs bark. (This is a premise.)

- Rover is a dog. (This is another premise.)

- So, Rover barks. (This is the conclusion.)

In this case, the argument is pretty solid. Both premises support the conclusion. But, if you have a shaky premise like "All cats bark," your conclusion will be off, even if it sounds right.

Sometimes, arguments have more than two premises, or they might be more complicated. But no matter how big or fancy the argument is, the same rule applies: the premises must be solid to support a good conclusion.

Logical Fallacy Examples in Life

Logical fallacies might seem small or harmless, but they can influence our decisions, beliefs, and actions in significant ways.

Advertising

Consider the world of advertising. Ads often use emotional appeals or bandwagon techniques to convince you to buy a product.

"Everyone's using this toothpaste, so you should too!" or "This celebrity loves our shoes, and you will too!"

If we don't recognize these as bandwagon or appeal to authority fallacies, we might end up spending money on things we don't need.

Social Media

Then there's the realm of social media. We've all seen heated debates in comment sections.

People might attack someone's character instead of their ideas, which is the ad hominem fallacy. Or, someone might oversimplify another person's viewpoint, setting up a straw man argument to easily tear it down.

When we're unaware of these tactics, it's easy to get dragged into unproductive or hurtful conversations.

And it's not just online. In real life, we make decisions based on information from friends, family, news, and many other sources.

If we're not careful, we might base important choices on faulty logic. Like believing a certain health remedy works just because a famous person endorses it without checking the actual science behind it.

Tips to Avoid Falling for Logical Fallacies

Understanding logical fallacies is half the battle. But how do you avoid them in real life? It's a bit like avoiding potholes on a road. Once you know where they are and what they look like, you can steer clear.

Here are some handy tips to help you navigate the landscape of logic more safely.

- Stay Curious: Always be open to learning. The more knowledge you gather, the better you'll be able to recognize when something doesn't add up.

- Question Everything: Just because something sounds right doesn't mean it is. Like a detective, look for evidence and ask yourself if an argument makes sense.

- Slow Down: Our world is fast-paced. But sometimes, taking a moment to think before responding or making a decision can save you from falling into a logical trap.

- Stay Humble: Remember, it's okay to be wrong. If someone points out a flaw in your reasoning, thank them. It's a chance to learn and grow.

- Discuss with Others: Talking things out can be a great way to spot flaws. Different perspectives can shine a light on areas you might have missed.

- Educate Yourself: There are plenty of resources, including books and courses, that can deepen your understanding of logical thinking. The more you learn, the sharper your logic skills will become.

- Practice Makes Perfect: Like any skill, spotting logical fallacies gets easier with practice. Challenge yourself by analyzing arguments in articles, shows, or conversations. The more you do it, the better you'll get.

Remember, nobody's perfect. We all slip up from time to time. But with these tips in your toolkit, you'll be well on your way to clearer, more logical thinking.

Spot the Fallacy Quiz

Try to identify each fallacy based on the examples provided. The answers are provided at the end.

- "My mom said that broccoli is good for me, so it must be true."

- "Either you stand with us, or you’re against us."

- "She can’t be a great scientist. Have you seen how disorganized her office is?"

- "We know our product is the best because it’s the top-selling item in its category."

- "He can’t be a criminal; he comes from a nice family and attended a prestigious university."

- "Well, you smoke cigarettes, so you have no right to tell me not to eat junk food."

- "We can’t let the students have extra recess time; soon, they’ll want the whole school day to be a playground."

- "Everyone’s going to the big football game, so it must be amazing."

- "No one has proven that ghosts don’t exist, so they must be real."

- "He’s never been to Asia, so he can't possibly know how to prepare Asian cuisine."

- "You can’t trust John’s political opinion because he’s just a mechanic."

- "We’ve always done it this way, so it’s the best way to keep doing it."

- "You believe in evolution? Well, that’s just a theory!"

- "If you cared about the environment, you wouldn't drive a car."

- "Since you didn’t deny the allegations immediately, you must be guilty."

- "We don’t know what causes thunder, so it must be the gods showing their anger."

- "This anti-aging cream must work; see all these photos of people who look younger after using it!"

- "No Scotsman puts sugar on his porridge!"

- "If we allow people to protest, it will encourage lawlessness and chaos."

- "We can't believe in climate change. Think of all the jobs we will lose in traditional industries!"

- Appeal to Authority

- False Dichotomy/Black and White Fallacy

- Genetic Fallacy

- Slippery Slope

- Argument from Ignorance

- No True Scotsman

- Appeal to Tradition

- Black-and-White Fallacy

- Argument from Silence

- God of the Gaps/Argument from Ignorance

- Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc

- Appeal to Consequence

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) about Logical Fallacies

What is a logical fallacy? A logical fallacy is an error or flaw in reasoning. These errors can weaken arguments and can be intentional or unintentional. They often appear to sound convincing but are based on faulty logic.

Why do people use logical fallacies? Some people might use them unintentionally due to a lack of knowledge or clarity in thinking. Others might use them strategically to persuade or deceive, especially if they believe their audience won't recognize the fallacy.

Are all fallacies intentional? No. Many fallacies are the result of honest mistakes or oversights in reasoning. However, some can be used manipulatively in debates, advertisements, or persuasive speeches.

What’s the difference between an informal and a formal fallacy? Informal fallacies are mistakes in reasoning based on the content of an opponent's argument, often arising in everyday language. Formal fallacies are structural errors in an argument, regardless of the argument's content.

Can a statement be true even if it contains a logical fallacy? Yes. A fallacy indicates flawed reasoning, not necessarily a false conclusion. However, conclusions reached through fallacious reasoning should be critically evaluated.

How can I improve my ability to spot logical fallacies? Educate yourself on different types of fallacies, engage in discussions, analyze arguments in various media, and regularly practice identifying them. Over time, spotting most common logical fallacies will become second nature.

Are logical fallacies a modern concept? No. The study of fallacies dates back to ancient Greece, with philosophers like Aristotle detailing various types of flawed arguments.

Why is it essential to recognize logical fallacies? Recognizing fallacies can help you make better decisions, strengthen your own arguments, and avoid being misled by faulty reasoning.

Can a logical fallacy be valid in some contexts? While the reasoning may be flawed, the underlying point someone is trying to make could still be valid. However, it's essential to separate the valid point from the fallacious argument.

Grasping the nuances of logical fallacies is more than just an academic exercise—it's a life skill.

In a world saturated with information, discerning sound arguments from flawed ones is invaluable. As you continue your journey in understanding and recognizing these fallacies, you're not only refining your ability to think critically but also empowering yourself to engage more constructively in discussions and debates.

Remember, pursuing clear, logical, critical thinking is a journey, not a destination. As you grow and learn, you'll become better equipped to navigate the complex landscape of ideas and arguments that surround us daily.

Related posts:

- Ad Hoc Fallacy (29 Examples + Other Names)

- Genetic Fallacy (28 Examples + Definition)

- Appeal to Ignorance Fallacy (29 Examples + Description)

- Hasty Generalization Fallacy (31 Examples + Similar Names)

- Appeal to Force Fallacy (Description + 9 Examples)

Reference this article:

About The Author

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

Jessie Ball duPont Library

Critical thinking skills, watch the fallacies.

- Need Research Help?

- Research Help

Although there are more than two dozen types and subtypes of logical fallacies, these are the most common forms that you may encounter in writing, argument, and daily life:

Example: Special education students should not be required to take standardized tests because such tests are meant for nonspecial education students.

Example: Two out of three patients who were given green tea before bedtime reported sleeping more soundly. Therefore, green tea may be used to treat insomnia.

- Sweeping generalizations are related to the problem of hasty generalizations. In the former, though, the error consists in assuming that a particular conclusion drawn from a particular situation and context applies to all situations and contexts. For example, if I research a particular problem at a private performing arts high school in a rural community, I need to be careful not to assume that my findings will be generalizable to all high schools, including public high schools in an inner city setting.

Example: Professor Berger has published numerous articles in immunology. Therefore, she is an expert in complementary medicine.

Example: Drop-out rates increased the year after NCLB was passed. Therefore, NCLB is causing kids to drop out.

Example: Japanese carmakers must implement green production practices, or Japan‘s carbon footprint will hit crisis proportions by 2025.

In addition to claims of policy, false dilemma seems to be common in claims of value. For example, claims about abortion‘s morality (or immorality) presuppose an either-or about when "life" begins. Our earlier example about sustainability (―Unsustainable business practices are unethical.‖) similarly presupposes an either/or: business practices are either ethical or they are not, it claims, whereas a moral continuum is likelier to exist.

Begging the Question/Circular Reasoning

Hasty Generalization

Sweeping Generalization

Non Sequitur

Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc

False Dilemma

- << Previous: Abduction

- Next: Need Research Help? >>

- Last Updated: Jul 28, 2020 5:53 PM

- URL: https://library.sewanee.edu/critical_thinking

Research Tools

- Find Articles

- Find Research Guides

- Find Databases

- Ask a Librarian

- Learn Research Skills

- How-To Videos

- Borrow from Another Library (Sewanee ILL)

- Find Audio and Video

- Find Reserves

- Access Electronic Resources

Services for...

- College Students

- The School of Theology

- The School of Letters

- Community Members

Spaces & Places

- Center for Leadership

- Center for Speaking and Listening

- Center for Teaching

- Floor Maps & Locations

- Ralston Listening Library

- Study Spaces

- Tech Help Desk

- Writing Center

About the Library

- Where is the Library?

- Library Collections

- New Items & Themed Collections

- Library Policies

- Library Staff

- Friends of the Library

Jessie Ball duPont Library, University of the South

178 Georgia Avenue, Sewanee, TN 37383

931.598.1664

3 Fallacies

I. what a re fallacies 1.

Fallacies are mistakes of reasoning, as opposed to making mistakes that are of a factual nature. If I counted twenty people in the room when there were in fact twenty-one, then I made a factual mistake. On the other hand, if I believe that there are round squares I believe something that is contradictory. A belief in “round squares” is a mistake of reasoning and contains a fallacy because, if my reasoning were good, I would not believe something that is logically inconsistent with reality.

In some discussions, a fallacy is taken to be an undesirable kind of argument or inference. In our view, this definition of fallacy is rather narrow, since we might want to count certain mistakes of reasoning as fallacious even though they are not presented as arguments. For example, making a contradictory claim seems to be a case of fallacy, but a single claim is not an argument. Similarly, putting forward a question with an inappropriate presupposition might also be regarded as a fallacy, but a question is also not an argument. In both of these situations though, the person is making a mistake of reasoning since they are doing something that goes against one or more principles of correct reasoning. This is why we would like to define fallacies more broadly as violations of the principles of critical thinking , whether or not the mistakes take the form of an argument.

The study of fallacies is an application of the principles of critical thinking. Being familiar with typical fallacies can help us avoid them and help explain other people’s mistakes.

There are different ways of classifying fallacies. Broadly speaking, we might divide fallacies into four kinds:

- Fallacies of inconsistency: cases where something inconsistent or self-defeating has been proposed or accepted.

- Fallacies of relevance: cases where irrelevant reasons are being invoked or relevant reasons being ignored.

- Fallacies of insufficiency: cases where the evidence supporting a conclusion is insufficient or weak.

- Fallacies of inappropriate presumption: cases where we have an assumption or a question presupposing something that is not reasonable to accept in the relevant conversational context.

II. Fallacies of I nconsistency

Fallacies of inconsistency are cases where something inconsistent, self-contradictory or self-defeating is presented.

1. Inconsistency

Here are some examples:

- “One thing that we know for certain is that nothing is ever true or false.” – If there is something we know for certain, then there is at least one truth that we know. So it can’t be the case that nothing is true or false.

- “Morality is relative and is just a matter of opinion, and so it is always wrong to impose our opinions on other people.” – But if morality is relative, it is also a relative matter whether we should impose our opinions on other people. If we should not do that, there is at least one thing that is objectively wrong.

- “All general claims have exceptions.” – This claim itself is a general claim, and so if it is to be regarded as true we must presuppose that there is an exception to it, which would imply that there exists at least one general claim that does not have an exception. So the claim itself is inconsistent.

2. Self- D efeating C laims

A self-defeating statement is a statement that, strictly speaking, is not logically inconsistent but is instead obviously false. Consider these examples:

- Very young children are fond of saying “I am not here” when they are playing hide-and-seek. The statement itself is not logically consistent, since it is not logically possible for the child not to be where she is. What is impossible is to utter the sentence as a true sentence (unless it is used for example in a telephone recorded message.)

- Someone who says, “I cannot speak any English.”

- Here is an actual example: A TV program in Hong Kong was critical of the Government. When the Hong Kong Chief Executive Mr. Tung was asked about it, he replied, “I shall not comment on such distasteful programs.” Mr. Tung’s remark was not logically inconsistent, because what it describes is a possible state of affairs. But it is nonetheless self-defeating because calling the program “distasteful” is to pass a comment!

III. Fallacies of R elevance

1. taking irrelevant considerations into account.

This includes defending a conclusion by appealing to irrelevant reasons, e.g., inappropriate appeal to pity, popular opinion, tradition, authority, etc. An example would be when a student failed a course and asked the teacher to give him a pass instead, because “his parents will be upset.” Since grades should be given on the basis of performance, the reason being given is quite irrelevant.

Similarly, suppose someone criticizes the Democratic Party’s call for direct elections in Hong Kong as follows: “These arguments supporting direct elections have no merit because they are advanced by Democrats who naturally stand to gain from it.” This is again fallacious because whether the person advancing the argument has something to gain from direct elections is a completely different issue from whether there ought to be direct elections.

2. Failing to T ake R elevant C onsiderations into A ccount

For example, it is not unusual for us to ignore or downplay criticisms because we do not like them, even when those criticisms are justified. Or sometimes we might be tempted to make a snap decision, believing knee-jerk reactions are the best when, in fact, we should be investigating the situation more carefully and doing more research.

Of course, if we fail to consider a relevant fact simply because we are ignorant of it, then this lack of knowledge does not constitute a fallacy.

IV. Fallacies of Insufficiency

Fallacies of insufficiency are cases where insufficient evidence is provided in support of a claim. Most common fallacies fall within this category. Here are a few popular types:

1. Limited S ampling

- Momofuku Ando, the inventor of instant noodles, died at the age of 96. He said he ate instant noodles every day. So instant noodles cannot be bad for your health.

- A black cat crossed my path this morning, and I got into a traffic accident this afternoon. Black cats are really unlucky.

In both cases the observations are relevant to the conclusion, but a lot more data is needed to support the conclusion, e.g., studies show that many other people who eat instant noodles live longer, and those who encounter black cats are more likely to suffer from accidents.

2. Appeal to I gnorance

- We have no evidence showing that he is innocent. So he must be guilty.

If someone is guilty, it would indeed be hard to find evidence showing that he is innocent. But perhaps there is no evidence to point either way, so a lack of evidence is not enough to prove guilt.

3. Naturalistic F allacy

- Many children enjoy playing video games, so we should not stop them from playing.

Many naturalistic fallacies are examples of fallacy of insufficiency. Empirical facts by themselves are not sufficient for normative conclusions, even if they are relevant.

There are many other kinds of fallacy of insufficiency. See if you can identify some of them.

V. Fallacies of Inappropriate Presumption

Fallacies of inappropriate presumption are cases where we have explicitly or implicitly made an assumption that is not reasonable to accept in the relevant context. Some examples include:

- Many people like to ask whether human nature is good or evil. This presupposes that there is such a thing as human nature and that it must be either good or bad. But why should these assumptions be accepted, and are they the only options available? What if human nature is neither good nor bad? Or what if good or bad nature applies only to individual human beings?

- Consider the question “Have you stopped being an idiot?” Whether you answer “yes” or “no,” you admit that you are, or have been, an idiot. Presumably you do not want to make any such admission. We can point out that this question has a false assumption.

- “Same-sex marriage should not be allowed because by definition a marriage should be between a man and a woman.” This argument assumes that only a heterosexual conception of marriage is correct. But this begs the question against those who defend same-sex marriages and is not an appropriate assumption to make when debating this issue.

VI. List of Common Fallacies

A theory is discarded not because of any evidence against it or lack of evidence for it, but because of the person who argues for it. Example:

A: The Government should enact minimum-wage legislation so that workers are not exploited. B: Nonsense. You say that only because you cannot find a good job.

ad ignorantiam (appeal to ignorance)

The truth of a claim is established only on the basis of lack of evidence against it. A simple obvious example of such fallacy is to argue that unicorns exist because there is no evidence against their existence. At first sight it seems that many theories that we describe as “scientific” involve such a fallacy. For example, the first law of thermodynamics holds because so far there has not been any negative instance that would serve as evidence against it. But notice, as in cases like this, there is evidence for the law, namely positive instances. Notice also that this fallacy does not apply to situations where there are only two rival claims and one has already been falsified. In situations such as this, we may justly establish the truth of the other even if we cannot find evidence for or against it.

ad misericordiam (appeal to pity)

In offering an argument, pity is appealed to. Usually this happens when people argue for special treatment on the basis of their need, e.g., a student argues that the teacher should let them pass the examination because they need it in order to graduate. Of course, pity might be a relevant consideration in certain conditions, as in contexts involving charity.

ad populum (appeal to popularity)

The truth of a claim is established only on the basis of its popularity and familiarity. This is the fallacy committed by many commercials. Surely you have heard of commercials implying that we should buy a certain product because it has made to the top of a sales rank, or because the brand is the city’s “favorite.”

Affirming the consequent

Inferring that P is true solely because Q is true and it is also true that if P is true, Q is true.

The problem with this type of reasoning is that it ignores the possibility that there are other conditions apart from P that might lead to Q. For example, if there is a traffic jam, a colleague may be late for work. But if we argue from his being late to there being a traffic jam, we are guilty of this fallacy – the colleague may be late due to a faulty alarm clock.

Of course, if we have evidence showing that P is the only or most likely condition that leads to Q, then we can infer that P is likely to be true without committing a fallacy.

Begging the question ( petito principii )

In arguing for a claim, the claim itself is already assumed in the premise. Example: “God exists because this is what the Bible says, and the Bible is reliable because it is the word of God.”

Complex question or loaded question

A question is posed in such a way that a person, no matter what answer they give to the question, will inevitably commit themselves to some other claim, which should not be presupposed in the context in question.

A common tactic is to ask a yes-no question that tricks people into agreeing to something they never intended to say. For example, if you are asked, “Are you still as self-centered as you used to be?”, no matter whether you answer “yes” or ”no,” you are bound to admit that you were self-centered in the past. Of course, the same question would not count as a fallacy if the presupposition of the question were indeed accepted in the conversational context, i.e., that the person being asked the question had been verifiably self-centered in the past.

Composition (opposite of division)

The whole is assumed to have the same properties as its parts. Anne might be humorous and fun-loving and an excellent person to invite to the party. The same might be true of Ben, Chris and David, considered individually. But it does not follow that it will be a good idea to invite all of them to the party. Perhaps they hate each other and the party will be ruined.

Denying the antecedent

Inferring that Q is false just because if P is true, Q is also true, but P is false.

This fallacy is similar to the fallacy of affirming the consequent. Again the problem is that some alternative explanation or cause might be overlooked. Although P is false, some other condition might be sufficient to make Q true.

Example: If there is a traffic jam, a colleague may be late for work. But it is not right to argue in the light of smooth traffic that the colleague will not be late. Again, his alarm clock may have stopped working.

Division (opposite of composition)

The parts of a whole are assumed to have the same properties as the whole. It is possible that, on a whole, a company is very effective, while some of its departments are not. It would be inappropriate to assume they all are.

Equivocation

Putting forward an argument where a word changes meaning without having it pointed out. For example, some philosophers argue that all acts are selfish. Even if you strive to serve others, you are still acting selfishly because your act is just to satisfy your desire to serve others. But surely the word “selfish” has different meanings in the premise and the conclusion – when we say a person is selfish we usually mean that he does not strive to serve others. To say that a person is selfish because he is doing something he wants, even when what he wants is to help others, is to use the term “selfish” with a different meaning.

False dilemma

Presenting a limited set of alternatives when there are others that are worth considering in the context. Example: “Every person is either my enemy or my friend. If they are my enemy, I should hate them. If they’re my friend, I should love them. So I should either love them or hate them.” Obviously, the conclusion is too extreme because most people are neither your enemy nor your friend.

Gambler’s fallacy

Assumption is made to take some independent statistics as dependent. The untrained mind tends to think that, for example, if a fair coin is tossed five times and the results are all heads, then the next toss will more likely be a tail. It will not be, however. If the coin is fair, the result for each toss is completely independent of the others. Notice the fallacy hinges on the fact that the final result is not known. Had the final result been known already, the statistics would have been dependent.

Genetic fallacy

Thinking that because X derives from Y, and because Y has a certain property, that X must also possess that same property. Example: “His father is a criminal, so he must also be up to no good.”

Non sequitur

A conclusion is drawn that does not follow from the premise. This is not a specific fallacy but a very general term for a bad argument. So a lot of the examples above and below can be said to be non sequitur.

Post hoc, ergo propter hoc (literally, “ after this, therefore because of this ” )

Inferring that X must be the cause of Y just because X is followed by Y.

For example, having visited a graveyard, I fell ill and infer that graveyards are spooky places that cause illnesses. Of course, this inference is not warranted since this might just be a coincidence. However, a lot of superstitious beliefs commit this fallacy.

Red herring

Within an argument some irrelevant issue is raised that diverts attention from the main subject. The function of the red herring is sometimes to help express a strong, biased opinion. The red herring (the irrelevant issue) serves to increase the force of the argument in a very misleading manner.

For example, in a debate as to whether God exists, someone might argue that believing in God gives peace and meaning to many people’s lives. This would be an example of a red herring since whether religions can have a positive effect on people is irrelevant to the question of the existence of God. The positive psychological effect of a belief is not a reason for thinking that the belief is true.

Slippery slope

Arguing that if an opponent were to accept some claim C 1 , then they have to accept some other closely related claim C 2 , which in turn commits the opponent to a still further claim C 3 , eventually leading to the conclusion that the opponent is committed to something absurd or obviously unacceptable.

This style of argumentation constitutes a fallacy only when it is inappropriate to think if one were to accept the initial claim, one must accept all the other claims.

An example: “The government should not prohibit drugs. Otherwise the government should also ban alcohol or cigarettes. And then fatty food and junk food would have to be regulated too. The next thing you know, the government would force us to brush our teeth and do exercises every day.”

Attacking an opponent while falsely attributing to them an implausible position that is easily defeated.

Example: When many people argue for more democracy in Hong Kong, a typical “straw man” reply is to say that more democracy is not warranted because it is wrong to believe that democracy is the solution to all of Hong Kong’s problems. But those who support more democracy in Hong Kong never suggest that democracy can solve all problems (e.g., pollution), and those who support more democracy in Hong Kong might even agree that blindly accepting anything is rarely the correct course of action, whether it is democracy or not. Theses criticisms attack implausible “straw man” positions and do not address the real arguments for democracy.

Suppressed evidence

Where there is contradicting evidence, only confirming evidence is presented.

VII. Exercises

Identify any fallacy in each of these passages. If no fallacy is committed, select “no fallacy involved.”

1. Mr. Lee’s views on Japanese culture are wrong. This is because his parents were killed by the Japanese army during World War II and that made him anti-Japanese all his life.

2. Every ingredient of this soup is tasty. So this must be a very tasty soup.

3. Smoking causes cancer because my father was a smoker and he died of lung cancer.

4. Professor Lewis, the world authority on logic, claims that all wives cook for their husbands. But the fact is that his own wife does not cook for him. Therefore, his claim is false.

5. If Catholicism is right, then no women should be allowed to be priests. But Catholicism is wrong. Therefore, some women should be allowed to be priests.

6. God does not exist because every argument for the existence of God has been shown to be unsound.

7. The last three times I have had a cold I took large doses of vitamin C. On each occasion, the cold cleared up within a few days. So vitamin C helped me recover from colds.

8. The union’s case for more funding for higher education can be ignored because it is put forward by the very people – university staff – who would benefit from the increased money.

9. Children become able to solve complex problems and think of physical objects objectively at the same time that they learn language. Therefore, these abilities are caused by learning a language.

10. If cheap things are no good then this cheap watch is no good. But this watch is actually quite good. So some good things are cheap.

Critical Thinking Copyright © 2019 by Brian Kim is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Everyday Psychology. Critical Thinking and Skepticism.

What are Logical Fallacies? | Critical Thinking Basics

Logical fallacies are errors in reasoning or flawed arguments that can mislead or deceive. They often appear plausible but lack sound evidence or valid reasoning, undermining the credibility of an argument. These errors can be categorized into various types, such as ad hominem attacks, strawman arguments, and false cause correlations.

Impact on Critical Thinking, Communication, and Social Interactions

The presence of logical fallacies hampers critical thinking by leading individuals away from rational and evidence-based conclusions. In communication, they can create confusion, weaken the persuasiveness of an argument, and hinder the exchange of ideas.

In social interactions, reliance on fallacious reasoning can strain relationships, impede collaboration, and contribute to misunderstandings.

Benefits of Identifying and Managing Logical Fallacies

Learning to identify logical fallacies enhances critical thinking skills, enabling individuals to analyze arguments more effectively and make informed decisions. In communication, recognizing fallacies empowers individuals to construct more compelling and convincing arguments, fostering clearer and more meaningful exchanges.

Moreover, the ability to manage logical fallacies promotes healthier social interactions by minimizing misunderstandings, encouraging constructive dialogue, and fostering a more intellectually robust and collaborative environment.

RETURN TO THE MAIN RESOURCE PAGE: CRITICAL THINKING BASICS

Share this:

Critical Thinking - Writing Lab Tips and Strategies: Logical Fallacies

Logical fallacies.

Fallacies are fake or deceptive arguments, arguments that may sound good but prove nothing.

Ad Hominem Argumen t : Attacking the person instead of the argument.

Appeal to Closure : The argument that the issue must be decided so that those involved can have "closure."

Appeal to Heaven : Arguing that one's position or action is right because God said so. As Christians, we believe God has revealed his will through Scripture, but we can still fall into this fallacy if we attempt to justify ourselves apart from what the Bible says. Even if we are being consistent with Scripture, we may still be accused of this fallacy.

Appeal to Pity : Urging an audience to “root for the underdog” regardless of the issues at hand.

Appeal to Tradition : It's always been this way, it should continue to be this way.

Argument from Consequences : The fallacy of arguing that something cannot be true because if it were the consequences would be unacceptable.

Argument from Ignorance: The fallacy that since we don’t know whether a claim is true or false, it must be false (or that it must be true).

Argument from Inertia: The argument to continue on as before because changing would be admitting that one is wrong and that one had sacrificed needlessly.

Argument from Motives: The argument that someone must be wrong because their motives are wrong. Also, the reverse: someone is right because their motives are right.

Argumentum ad Baculam: Attempting to persuade through threats. Also applies to indirect forms of threat.

Argumentum ex Silentio: The fallacy that if sources remain silent or say nothing about a given subject or question this in itself proves something about the truth of the matter.

Bandwagon: The fallacy of arguing that because "everyone" supposedly thinks or does something, it must be right.

Begging the Question : Falsely arguing that something is true by repeating the same statement in different words.

Big Lie Technique: Repeating a lie, slogan or deceptive half-truth over and over (particularly in the media) until people believe it without further proof or evidence.

Blind Loyalty: Arguing something is right solely because a respected leader or source says it is right.

Blood is Thicker than Water: Automatically regarding something as true because one is related to (or knows and likes, or is on the same team as) the individual involved.

Bribery: Persuading with gifts instead of logic.

The Complex Question : Demanding a direct answer to a question containing acceptable and unacceptable parts. Example: "Yes or no: Have you stopped beating your wife yet?" "I never beat my--" "Just answer me: Yes or no?"

Diminished Responsibility : The argument that one is less responsible for an action because one's judgment was altered. Example: "I was high, so I shouldn't be fined for speeding; it wasn't my fault."

Either-Or Reasoning: Falsely offering only two possible alternatives even though a broad range of possible alternatives are available.

”E" for Effort: Arguing that something must be right, valuable, or worthy of credit simply because someone has put so much sincere good-faith effort or even sacrifice and bloodshed into it.

Equivocation : Deliberately failing to define one's terms, or deliberately using words in a different sense than the one the audience will understand.

Essentializing : A fallacy that proposes a person or thing “is what it is and that’s all that it is,” and at its core will always be what it is right now (E.g., "All ex-cons are criminals, and will still be criminals even if they live to be 100."). Also refers to the fallacy of arguing that something is a certain way "by nature," an empty claim that no amount of proof can refute.

False Analogy : Incorrectly comparing one thing to another in order to draw a false conclusion.

Finish the Job: Arguing that an action or standpoint may not be questioned or discussed because there is "a job to be done," falsely assuming all "jobs" are never to be questioned.

Guilt by Association: Trying to refute someone's arguments or actions by evoking the negative ethos of those with whom one associates.

The Half Truth (also Card Stacking, Incomplete Information).Telling the truth but deliberately omitting important key details in order to falsify the larger picture and support a false conclusion.

I Wish I Had a Magic Wand: Regretfully (and falsely) proclaiming oneself powerless to change a bad or objectionable situation because there is no alternative.

Just in Case : Basing one's argument on a far-fetched or imaginary worst-case scenario rather than on reality. Plays on fear rather than reason.

Lying with Statistics : Using true figures and numbers to “prove” unrelated claims.

MYOB (Mind Your Own Business) Arbitrarily prohibiting any discussion of one's own standpoints or behavior, no matter how absurd, dangerous, evil or offensive, by drawing a phony curtain of privacy around oneself and one's actions.

Name-Calling: Arguing that, simply because of who someone is, any and all arguments, disagreements or objections against his or her standpoint are automatically racist, sexist, anti-Semitic, bigoted, discriminatory or hateful.

Non Sequitur : Offering reasons or conclusions that have no logical connection to the argument at hand.

Overgeneralization: Incorrectly applying one or two examples to all cases.

The Paralysis of Analysis : Arguing that since all data is never in, no legitimate decision can ever be made and any action should always be delayed until forced by circumstances.

Playing on Emotions : Ignoring facts and calling on emotion alone.

Political Correctness ("PC"): Proposing that the nature of a thing or situation can be changed simply by changing its name.

Post Hoc Argument : Arguing that because something comes at the same time or just after something else, the first thing is caused by the second.

Red Herring : An irrelevant distraction, attempting to mislead an audience by bringing up an unrelated, but usually emotionally loaded issue.

Reductionism : Deceiving an audience by giving simple answers or slogans in response to complex questions, especially when appealing to less educated or unsophisticated audiences.

Reifying : The fallacy of treating imaginary categories as actual, material "things."

Sending the Wrong Message : Attacking a given statement or action, no matter how true, correct or necessary, because it will "send the wrong message." In effect, those who uses this fallacy are publicly confessing to fraud and admitting that the truth will destroy the fragile web of illusion that has been created by their lies.

Shifting the Burden of Proof: Challenging opponents to disprove a claim, rather than asking the person making the claim to defend his/her own argument.

Slippery Slope : The common fallacy that "one thing inevitably leads to another."

Snow Job : "Proving” a claim by overwhelming an audience with mountains of irrelevant facts, numbers, documents, graphs and statistics that they cannot be expected to understand.

Straw Man : Setting up a phony version of an opponent's argument, and then proceeding to knock it down with a wave of the hand.

Taboo : Unilaterally declaring certain arguments, standpoints or actions to be not open to discussion.

Testimonial : When a standpoint or product is supported by a well-known or respected figure who is not an expert and who was probably well paid for the endorsement.

They're Not Like Us : Arbitrarily disregarding a fact, argument, or objection because those involved "are not like us," or "don't think like us."

TINA (There Is No Alternative): Squashing critical thought by announcing that there is no realistic alternative to a given standpoint, status or action, ruling any and all other options irrelevant and any further discussion is simply a waste of time.

Transfer : Falsely associating a famous person or thing with an unrelated standpoint.

Tu Quoque: Defending a shaky or false standpoint or excusing one's own bad action by pointing out that one's opponent's acts or personal character are also open to question, or even worse.

We Have to Do Something : Arguing that in moments of crisis one must do something, anything , at once, even if it is an overreaction, is totally ineffective or makes the situation worse, rather than "just sitting there doing nothing."

Where there’s smoke, there’s fire : Quickly drawing a conclusion and/or taking action without sufficient evidence.

For more in-depth discussion of these fallacies, refer to http://utminers.utep.edu/omwilliamson/ENGL1311/fallacies.htm

Subject Guide

I'm trying to think critically, but I'm a frog

- << Previous: Home

- Last Updated: May 17, 2023 3:05 PM

- URL: https://libguides.grace.edu/CriticalThinking

Passion doesn’t always come easily. Discover your inner drive and find your true purpose in life.

From learning how to be your best self to navigating life’s everyday challenges.

Discover peace within today’s chaos. Take a moment to notice what’s happening now.

Gain inspiration from the lives of celebrities. Explore their stories for motivation and insight into achieving your dreams.

Where ordinary people become extraordinary, inspiring us all to make a difference.

Take a break with the most inspirational movies, TV shows, and books we have come across.

From being a better partner to interacting with a coworker, learn how to deepen your connections.

Take a look at the latest diet and exercise trends coming out. So while you're working hard, you're also working smart.

Sleep may be the most powerful tool in our well-being arsenal. So why is it so difficult?

Challenges can stem from distractions, lack of focus, or unclear goals. These strategies can help overcome daily obstacles.

Unlocking your creativity can help every aspect of your life, from innovation to problem-solving to personal growth.

How do you view wealth? Learn new insights, tools and strategies for a better relationship with your money.

9 Logical Fallacies That You Need to Know To Master Critical Thinking

When you learn about logic, language becomes a game you can win..

William James, who was known as the grandfather of psychology, once said: “A great many people think they are thinking when they are merely rearranging their prejudices.” All of us think, every day. But there’s a difference between thinking for thinking’s sake, and thinking in a critical way. Deliberate, controlled, and reasonable thinking is rare.

There are multiple factors that are impairing people’s ability to think critically, from technology to changes in education. Some experts have speculated we’re approaching a crisis of critical thinking , with many students graduating “without the ability to construct a cohesive argument or identify a logical fallacy.”

RELATED: How to Tell if ‘Political Correctness’ Is Hurting Your Mental Health

That's a worrying trend, as critical thinking isn’t only an academic skill, but essential to living a high-functioning life. It’s the process by which to arrive at logical conclusions. And in through that process, logical fallacies are a significant hazard.

This article will explore logical fallacies in order to equip you with the knowledge on how to think in skillful ways, for the biggest benefits. As a result, you'll be able to detect deception of flawed logic, in others, and yourself. And you'll be equipped to think proper thoughts, rather than simply rearrange prejudices.

What Is a Logical Fallacy?

The study of logic originates back to the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 b.c.e), who started to systematically identify and list logical fallacies. The origin of logic is linked to the Greek logos , which translates to language, reason, or discourse. Logical fallacies are errors of reason that invalidate an argument. The use of logical fallacies changes depending on a person’s intention. Although for many, they’re unintentional, others may deliberately use logical fallacies as a type of manipulative behavior .

Detecting logical fallacies is crucial to improve your level of critical thinking, to avoid deceit, and to spot poor reasoning; within yourself and others. The influential German philosopher Immanuel Kant once said; “All our knowledge begins with the senses, proceeds then to the understanding, and ends with reason. There is nothing higher than reason.”

RELATED: Fundamental Attribution Error: Definition & Examples

Throughout history, the world’s greatest thinkers have promoted the value of reasoning. Away from academia, reason is the ability to logically process information, and arrive at an accurate conclusion, in the quest for truth. Striving to be more reasonable or calm under pressure is a virtuous act. It’s a noble pursuit, one which in its nature will inspire your personal development, and allow you to become the best version of yourself.

Why Critical Thinking Is Important

It seems like humanity has never been so polarized, separated into different camps and stances; Democrats vs. Liberals, vegans vs. meat eaters, vaccinated vs. unvaccinated, pro-life vs. pro-choice. There’s nothing inherently wrong with thinking critically, and taking a stand. However, what is unusual is the tendency for people to lean into one extreme or the other, neglecting to explore gray areas or complexity.

Many of the positions people take are chosen for them. It takes a lot of effort to research a point of view. And even then, we’re faced with the challenge of information overload, fake news, conspiracy, and even credible news which is dismissed as conspiracy. Far from academic debates or politicians facing off during leadership races, the ability to share respectful dialogue is an essential part of understanding our place in the world, and maintaining human relationships.

The hot topics facing humanity aren’t going to be resolved by reactivity or over-emotionality . There should be room for all sorts of emotions to surface; it’s understandable to feel anger, grief, anxiety, etc, faced with global events. But critical thinking asks for a more reasoned, calm consideration, not getting completely carried away with emotions, but appealing to higher judgment.

Examples of When to Use Critical Thinking

It’s not always clear why critical thinking is so valuable. Isn’t it only useful for education, philosophy, science, or politics? Not quite. When applied appropriately, logic has a universal appeal in life. Examples include:

- Problem-solving : “The problem is not that there are problems,” wrote psychiatrist Theodore Isaac Rubin, “the problem is expecting otherwise, and thinking that having problems is a problem.” Life is full of problems. Fortunately, that means life is full of opportunities to problem solve. Critical thinking is an essential problem-solving skill, from managing your time to organizing your finances.

- Making optimal decisions : the more logical you are, and the less you fall into logical fallacies, the better your decision-making becomes . Decisions are the steps towards your goals, each decision making you closer to, or away from, what you really desire.

- Understanding complex subjects : with attention spans reducing due to social media and technology, it’s becoming rare to take time to attempt to understand complex topics, away from repeating what others have said. Whether through self-study or to comprehend global events, critical thinking is essential to understand complexity.

- Improving relationships : adding a dose of logic to your interactions will allow you to make better choices in relationships. Many “messy” forms of communication, from guilt-tripping to passive aggression, are illogical. By tapping into a more balanced point of view, you’ll better overcome conflict, argue your point (when necessary), or explain the way you feel.

The Most Common Logical Fallacies

When you begin to explore logical fallacies, language becomes a game. There’s a sense of having a cheat sheet in communication, understanding the underlying dynamics at play. Of course, it’s not as straightforward as a mechanical understanding — emotional intelligence, and non-verbal body language has a role to play, too. We’re humans, not computers. But gaining mastery of logic puts you ahead of the majority of people, and helps you avoid cognitive bias.

What’s more, most people fall into logical fallacies without being aware. Once you can detect these mechanisms, within yourself and with others, you’ll have an upper hand in many key areas of life, not least in a professional setting, or in any place you need to persuade or argue a point. The list is ever-growing and vast, but below are the most common logical fallacies to get the ball rolling:

1. Ad Hominem

Originating from a Latin phrase meaning “to the person,” ad hominem is an attack on the person, not the argument. This has a twofold impact — it deflects attention away from the validity of the argument, and second, it can provoke the person to enter a defensive mindset. If you’re aware of this fallacy, it can keep you from taking the bait, and instead keeping the focus on the argument.

Perhaps the most popular example of this in recent times is the viral interview between Jordan Peterson and Cathy Newman. Love him or hate him, Peterson is an embodiment of logic, sidestepping Newman’s ad hominem attacks and fallacies in a calm and controlled manner.

2. Red Herring

You might have heard of this phrase in the context of fiction: a red herring is an irrelevant piece of information thrown into the mix, in order to distract from other relevant details, commonly used in detective stories. In a political context, you might see a politician respond to criticism by talking about something positive they’ve done. For example, when asked why unemployment is so high, they may say “we’ve made a lot of effort to improve working conditions in certain areas.”

A popular type of red herring in modern discourse is "what aboutism," a form of counter-accusation. If the person mentioning unemployment is a fellow politician, the same politician may say: “what about unemployment rates when your party was in charge?”

3. Tu Quoque Fallacy

Closely related to the above, and in some ways, a mixture of the ad hominem and a red herring, is the tu quoque fallacy (pronounced tu-KWO-kway and originating from the Latin “you too”). This is a counter-accusation that accuses someone of hypocrisy. Rather than acknowledging what's been said, someone responds with a direct allegation. For example, if you’re in an argument and your partner raises their voice, you may bring that to their attention, only for them to say: “you raise your voice all the time!”.

4. Straw Man

The straw man logical fallacy is everywhere, especially in dialogue on hot-topic issues, because it's effective in shutting down someone else’s perspective. The person runs with someone’s point, exaggerates it, then attacks the exaggerated version — the straw man — seemingly in an appropriate way. For example, when your partner asks if you could do the washing up, you might respond: “are you saying I don’t support you around the house? That’s unfair.”

On the global stage, one of the big straw man arguments in recent times is the rhetoric of the anti-vaxxer, applied to resistance to mandated vaccines, social distancing, or lockdowns. The simplified term is a way of positioning someone as extreme, even if raising valid points, or looking to open dialogue about the repercussions of certain political choices, made without the option for the population to have their say.

5. Appeal to Authority

If someone in a position of authority says something is true, it must be true. This type of logical fallacy is ingrained in the psyche in childhood, where your parents' (or adults around you) word was final. Society is moving increasingly in this direction, especially in the fields of science. But that doesn’t come without risk, as even experts are known not to get things right.

In addition, many positions of authority aren’t always acting in pursuit of honesty or truth, if other factors (such as financial donations) have influence. While appeals to authority used to gravitate around religious leaders, a 2022 study found that, when linked with scientists, untrue statements are more likely to be believed, in what researchers call the Einstein effect .

6. False Dichotomy

Also known as the false dilemma, this logical fallacy presents limited options in certain scenarios in a way that is inaccurate. It’s closely linked to black-or-white thinking or all-or-nothing thinking, presenting two extremes without options in between. This is perhaps one of the most invasive logical fallacies in navigating life’s demands. For example, you either go to the gym or become unhealthy.

These limitations require a dose of psychological flexibility and creative thinking to overcome. They require exploring other alternatives. In the example above, that would mean looking at other ways to become healthy and exercise, such as running outdoors or going swimming.

7. Slippery Slope Fallacy

Similar to the straw man fallacy, the slippery slope is a way of taking an issue to a hypothetical extreme and then dismissing it based on what could happen. The potential of one thing leading to another, and the repercussions of that chain of events, may cause the original issue to be overlooked. For example, if you fail to set a boundary in one situation, you’ll forever be stuck in accepting certain behaviors.

The issue with this fallacy is that a valid process of critical thinking is to look at what decisions can lead to in the future. Rather than dismiss outright, however, it pays to make reasoned decisions, avoid jumping to conclusions, and see how things unfold over time.

8. Sunk Cost Fallacy

This is the logical fallacy that, when having already invested in something, you continue to invest in order to get return on your sunk costs. Although using gambling terminology (such as chasing losses on roulette) the sunk cost can apply to any area of life. The investment itself doesn’t have to be financial. For example, investing lots of time and energy into a creative project, or a relationship.

The sunk cost fallacy causes people to overlook a true and accurate analysis of the situation in the present moment, instead choosing to continue because of past decisions.

9. Hasty Generalisation

Also known as an over-generalization or faulty generalization, this logical fallacy makes general claims based on little evidence. Before writing this article, I went to a new gym, where my toiletry bag was stolen. You could argue it’s bad luck for something like that to happen on your first visit. If I decide that the gym isn’t safe, and make a hasty generalization, I may end up not going again. But what if the rate of theft in this gym was below the average in the city, and I was just unlucky? What if it wasn’t stolen, but someone absent-mindedly put it in their bag?