Speaking and Writing: Similarities and Differences

by Alan | May 2, 2017 | Communication skills , public speaking , writing

Similarities and Differences Between Speaking and Writing

There are many similarities between speaking and writing. While I’ve never considered myself a writer by trade, I have long recognized the similarities between writing and speaking. Writing my book was the single best thing I’ve ever done for my business. It solidified our teaching model and clarified and organized our training content better than any other method I’d ever tried.

A few weeks ago I was invited by a client to attend a proposal writing workshop led by Robin Ritchey . Since I had helped with the oral end of proposals, the logic was that I would enjoy (or gain insight) from learning about the writing side. Boy, were they right. Between day one and two, I was asked by the workshop host to give a few thoughts on the similarities of writing to speaking. These insights helped me recognize some weaknesses in my writing and also to see how the two crafts complement each other.

Similarities between Speaking and Writing

Here are some of the similarities I find between speaking and writing:

- Rule #1 – writers are encouraged to speak to the audience and their needs. Speakers should do the same thing.

- Organization, highlight, summary (tell ‘em what you’re going to tell them, tell them, tell them what you told them). Structure helps a reader/listener follow along.

- No long sentences. A written guideline is 12-15 words. Sentences in speaking are the same way. T.O.P. Use punctuation. Short and sweet.

- Make it easy to find what they are looking for (Be as subtle as a sledgehammer!) .

- Avoid wild, unsubstantiated claims. If you are saying the same thing as everyone else, then you aren’t going to stand out.

- Use their language. Avoid internal lingo that only you understand.

- The audience needs to walk away with a repeatable message.

- Iteration and thinking are key to crafting a good message. In writing, this is done through editing. A well prepared speech should undergo the same process. Impromptu is slightly different, but preparing a good structure and knowing a core message is true for all situations.

- Build from an outline; write modularly. Good prose follows from a good structure, expanding details as necessary. Good speakers build from a theme/core message, instead of trying to reduce everything they know into a time slot. It’s a subtle mindset shift that makes all the difference in meeting an audience’s needs.

- Make graphics (visuals) have a point. Whether it’s a table, figure, or slide, it needs to have a point. Project schedule is not a point. Network diagram is not a point. Make the “action caption” – what is the visual trying to say? – first, then add the visual support.

- Find strong words. My editor once told me, “ An adverb means you have a weak verb. ” In the workshop, a participant said, “ You are allowed one adverb per document. ” Same is true in speaking – the more powerful your words, the more impact they will have. Really (oops, there was mine).

- Explain data, don’t rely on how obvious it is. Subtlety doesn’t work.

Differences between Speaking and Writing

There are also differences. Here are three elements of speaking that don’t translate well to (business) writing:

- Readers have some inherent desire to read. They picked up your book, proposal, white paper, or letter and thus have some motivation. Listeners frequently do not have that motivation, so it is incumbent on the speaker to earn attention, and do so quickly. Writers can get right to the point. Speakers need to get attention before declaring the point.

- Emotion is far easier to interpret from a speaker than an author. In business writing, I would coach a writer to avoid emotion. While it is a motivating factor in any decision, you cannot accurately rely on the interpretation of sarcasm, humor, sympathy, or fear to be consistent across audience groups. Speakers can display emotion through gestures, voice intonations, and facial expressions to get a far greater response. It is interesting to note that these skills are also the most neglected in speakers I observe – it apparently isn’t natural, but it is possible.

- Lastly, a speaker gets the benefit of a live response. She can answer questions, or respond to a quizzical look. She can spend more time in one area and speed through another based on audience reaction. And this also can bring an energy to the speech that helps the emotion we just talked about. With the good comes the bad. A live audience frequently brings with it fear and insecurity – and another channel of behaviors to monitor and control.

Speaking and writing are both subsets of the larger skill of communicating. Improving communication gives you more impact and influence. And improving is something anyone can do! Improve your speaking skills at our Powerful, Persuasive Speaking Workshop and improve your writing skills at our Creating Powerful, Persuasive Content Workshop .

Communication matters. What are you saying?

This article was published in the May 2017 edition of our monthly speaking tips email, Communication Matters. Have speaking tips like these delivered straight to your inbox every month. Sign up today and receive our FREE download, “Twelve Tips that will Save You from Making a Bad Presentation.” You can unsubscribe at any time.

Enter your email for once monthly speaking tips straight to your inbox…

GET FREE DOWNLOAD “Twelve Tips that will Save You from Making a Bad Presentation” when you sign up. We only collect, use and process your data according to the terms of our privacy policy .

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Recent posts.

- Reading Scripts

- Your First Words

- The Problem with “Them”

- Same Old Same Ol’

- I Don’t Have Time to Prepare

- Don’t Sound like you’re Reading

- Bad PowerPoint

- Desperate Times, Desperate Measures

- Three Phrases to Avoid When Trying to Convince

Enter your email for once monthly speaking tips straight to your inbox!

FREE eBOOK DOWNLOAD when you sign up . We only collect, use and process your data according to the terms of our privacy policy.

Thanks. Your tips are on the way!

MillsWyck Communications

Pin It on Pinterest

- My Portfolio

Writing vs. Speaking – The Similarities and Differences

If you work somewhere as a writer, you may have often heard your supervisor saying: ‘Please, try to write in the way you speak so that we can sell our products effectively.’ If you are an expert at Grammar, you may reply to your supervisor: How can I express punctuation marks while speaking? Both you and your supervisor are right. Writing and speaking do have similarities; however, people need to know that there are also differences between the two. Without further ado, let’s have a look at the similarities and differences between writing and speaking:

The Similarities between Writing and Speaking

Point #1: Writers are motivated to speak to the audience as per their needs while writing, and the speakers do the same thing.

Point #2: You need to highlight essential points in the form of a summary, whether you are writing or speaking.

Point #3: You need to stick to the point while writing, so you need to keep the length of your sentences to eight to fifteen (8 to 15) words while writing. You need to remain clear while speaking, so you need to remain restricted to a few words to convey your message correctly.

Point #4: While writing, you focus on keywords to convey your message, and you make a strong emphasis on words that can deliver your message well to the audience. Thus, both writers and speakers speak of the keywords.

Point #5: Make a valid claim if you want to sell, particularly if you’re going to sell your product by writing. You need to do the same while speaking; otherwise, your audience can switch to your competitors.

Point #6: Jargons are bad, so you shouldn’t use them while speaking and writing. Why? Because the whole world has no time to chat and produce slang words.

Point #7: Whether you speak or write, you need to repeat important words to ensure your message is being conveyed to the audience.

Point #8: You will need to come up with a good message to win your audience’s trust. Thus, you need to edit your content and proofread while reading; the same goes for speech.

Point #9: You need a theme to start with while writing or speaking.

Point #10: Pictures can speak a thousand words. You need to use them while you want to elaborate on something while writing. You also need to use the pictures to express your message to the target audience while giving a presentation.

Point #11: Use strong words while you speak or write. For instance, you can use the following sentence while speaking or writing: ‘Each participant has an equal chance (strong words) of selection.’

Point #12: Explain your point while writing and speaking to let the audience understand what you want to convey to them.

The Differences between Writing and Speaking

Point #1: Readers want to read whenever they have a desire for it. For example: ‘Readers may pick up a book, white paper, and a proposal to read it.’ Thus, writers can get the readers’ attention easily. However, the listeners don’t plan to listen to you all day; hence, you need to stick to the point while speaking to the audience.

Point #2: You can easily interpret emotion from a speaker than an author. Yes, writers can bring feelings in you; nonetheless, if you are writing a business letter, you should avoid emotional words if you want to get your reader’s attention. Business is a serious deal; therefore, you should avoid emotions in business writing.

Point #3: If you want to feel your audience’s response with your own eyes, you can rely on speaking. Why? Because writers don’t convey their messages in front of the audience.

Point #4: The proper usage of Grammar can make your write-ups better. You can’t do that while speaking because you make loads of grammatical mistakes while speaking. For instance, ‘A comma is used for a pause in writing; however, while speaking, you may avoid that pause and may spoil your speech to convey your message to the audience better.’

Finally, if you know many other similarities and differences between writing and speaking, you can share them in the form of comments.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

10 EXCELLENT RESOURCES TO FIND TRENDING TOPICS AND WRITE ARTICLES

Why Can You Trust a Freelance Content Writer?

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

I'M SOCIAL

Popular posts.

How Did Animation Proceed From Past to Present? Each Explainer Video Has a Value for Business

VALENTINE’S DAY

What Is a Logo?

Popular categories.

- Industry 17

- Content Writing 4

- Search Engine 4

- Ecommerce 1

MY FAVORITES

Top 5 most valuable fashion brands in the world, the mental health benefits of workouts, top 12 technology trends to follow in 2021, top 10 low investment business ideas in pakistan.

- Digital Offerings

- Biochemistry

- College Success

- Communication

- Electrical Engineering

- Environmental Science

- Mathematics

- Nutrition and Health

- Philosophy and Religion

- Our Mission

- Our Leadership

- Accessibility

- Diversity, Equity, Inclusion

- Learning Science

- Sustainability

- Affordable Solutions

- Curriculum Solutions

- Inclusive Access

- Lab Solutions

- LMS Integration

- Instructor Resources

- iClicker and Your Content

- Badging and Credidation

- Press Release

- Learning Stories Blog

- Discussions

- The Discussion Board

- Webinars on Demand

- Digital Community

- Macmillan Learning Peer Consultants

- Macmillan Learning Digital Blog

- Learning Science Research

- Macmillan Learning Peer Consultant Forum

- The Institute at Macmillan Learning

- Professional Development Blog

- Teaching With Generative AI: A Course for Educators

- English Community

- Achieve Adopters Forum

- Hub Adopters Group

- Psychology Community

- Psychology Blog

- Talk Psych Blog

- History Community

- History Blog

- Communication Community

- Communication Blog

- College Success Community

- College Success Blog

- Economics Community

- Economics Blog

- Institutional Solutions Community

- Institutional Solutions Blog

- Handbook for iClicker Administrators

- Nutrition Community

- Nutrition Blog

- Lab Solutions Community

- Lab Solutions Blog

- STEM Community

- STEM Achieve Adopters Forum

- Contact Us & FAQs

- Find Your Rep

- Training & Demos

- First Day of Class

- For Booksellers

- International Translation Rights

- Permissions

- Report Piracy

Digital Products

Instructor catalog, our solutions.

- Macmillan Community

- What Are the Differences Between Speaking and Writ...

What Are the Differences Between Speaking and Writing?

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Mark as New

- Mark as Read

- Printer Friendly Page

- Report Inappropriate Content

- basic writing

- digital composing

- professional development

- teaching advice

You must be a registered user to add a comment. If you've already registered, sign in. Otherwise, register and sign in.

- Bedford New Scholars 50

- Composition 565

- Corequisite Composition 58

- Developmental English 38

- Events and Conferences 6

- Instructor Resources 9

- Literature 55

- Professional Resources 4

- Virtual Learning Resources 48

What are the differences between writing and speaking?

Part of Language and Literacy Writing

Experimenting with language

- count 3 of 35

How to write a sentence

- count 4 of 35

How to write statement sentences

- count 5 of 35

- Constructed scripts

- Multilingual Pages

Differences between writing and speech

Written and spoken language differ in many ways. However some forms of writing are closer to speech than others, and vice versa. Below are some of the ways in which these two forms of language differ:

Writing is usually permanent and written texts cannot usually be changed once they have been printed/written out.

Speech is usually transient, unless recorded, and speakers can correct themselves and change their utterances as they go along.

A written text can communicate across time and space for as long as the particular language and writing system is still understood.

Speech is usually used for immediate interactions.

Written language tends to be more complex and intricate than speech with longer sentences and many subordinate clauses. The punctuation and layout of written texts also have no spoken equivalent. However some forms of written language, such as instant messages and email, are closer to spoken language.

Spoken language tends to be full of repetitions, incomplete sentences, corrections and interruptions, with the exception of formal speeches and other scripted forms of speech, such as news reports and scripts for plays and films.

Writers receive no immediate feedback from their readers, except in computer-based communication. Therefore they cannot rely on context to clarify things so there is more need to explain things clearly and unambiguously than in speech, except in written correspondence between people who know one another well.

Speech is usually a dynamic interaction between two or more people. Context and shared knowledge play a major role, so it is possible to leave much unsaid or indirectly implied.

Writers can make use of punctuation, headings, layout, colours and other graphical effects in their written texts. Such things are not available in speech

Speech can use timing, tone, volume, and timbre to add emotional context.

Written material can be read repeatedly and closely analysed, and notes can be made on the writing surface. Only recorded speech can be used in this way.

Some grammatical constructions are only used in writing, as are some kinds of vocabulary, such as some complex chemical and legal terms.

Some types of vocabulary are used only or mainly in speech. These include slang expressions, and tags like y'know , like , etc.

Writing systems : Abjads | Alphabets | Abugidas | Syllabaries | Semanto-phonetic scripts | Undeciphered scripts | Alternative scripts | Constructed scripts | Fictional scripts | Magical scripts | Index (A-Z) | Index (by direction) | Index (by language) | Index (by continent) | What is writing? | Types of writing system | Differences between writing and speech | Language and Writing Statistics | Languages

Page last modified: 23.04.21

728x90 (Best VPN)

Why not share this page:

If you like this site and find it useful, you can support it by making a donation via PayPal or Patreon , or by contributing in other ways . Omniglot is how I make my living.

Get a 30-day Free Trial of Amazon Prime (UK)

- Learn languages quickly

- One-to-one Chinese lessons

- Learn languages with Varsity Tutors

- Green Web Hosting

- Daily bite-size stories in Mandarin

- EnglishScore Tutors

- English Like a Native

- Learn French Online

- Learn languages with MosaLingua

- Learn languages with Ling

- Find Visa information for all countries

- Writing systems

- Con-scripts

- Useful phrases

- Language learning

- Multilingual pages

- Advertising

Comparing and Contrasting

What this handout is about.

This handout will help you first to determine whether a particular assignment is asking for comparison/contrast and then to generate a list of similarities and differences, decide which similarities and differences to focus on, and organize your paper so that it will be clear and effective. It will also explain how you can (and why you should) develop a thesis that goes beyond “Thing A and Thing B are similar in many ways but different in others.”

Introduction

In your career as a student, you’ll encounter many different kinds of writing assignments, each with its own requirements. One of the most common is the comparison/contrast essay, in which you focus on the ways in which certain things or ideas—usually two of them—are similar to (this is the comparison) and/or different from (this is the contrast) one another. By assigning such essays, your instructors are encouraging you to make connections between texts or ideas, engage in critical thinking, and go beyond mere description or summary to generate interesting analysis: when you reflect on similarities and differences, you gain a deeper understanding of the items you are comparing, their relationship to each other, and what is most important about them.

Recognizing comparison/contrast in assignments

Some assignments use words—like compare, contrast, similarities, and differences—that make it easy for you to see that they are asking you to compare and/or contrast. Here are a few hypothetical examples:

- Compare and contrast Frye’s and Bartky’s accounts of oppression.

- Compare WWI to WWII, identifying similarities in the causes, development, and outcomes of the wars.

- Contrast Wordsworth and Coleridge; what are the major differences in their poetry?

Notice that some topics ask only for comparison, others only for contrast, and others for both.

But it’s not always so easy to tell whether an assignment is asking you to include comparison/contrast. And in some cases, comparison/contrast is only part of the essay—you begin by comparing and/or contrasting two or more things and then use what you’ve learned to construct an argument or evaluation. Consider these examples, noticing the language that is used to ask for the comparison/contrast and whether the comparison/contrast is only one part of a larger assignment:

- Choose a particular idea or theme, such as romantic love, death, or nature, and consider how it is treated in two Romantic poems.

- How do the different authors we have studied so far define and describe oppression?

- Compare Frye’s and Bartky’s accounts of oppression. What does each imply about women’s collusion in their own oppression? Which is more accurate?

- In the texts we’ve studied, soldiers who served in different wars offer differing accounts of their experiences and feelings both during and after the fighting. What commonalities are there in these accounts? What factors do you think are responsible for their differences?

You may want to check out our handout on understanding assignments for additional tips.

Using comparison/contrast for all kinds of writing projects

Sometimes you may want to use comparison/contrast techniques in your own pre-writing work to get ideas that you can later use for an argument, even if comparison/contrast isn’t an official requirement for the paper you’re writing. For example, if you wanted to argue that Frye’s account of oppression is better than both de Beauvoir’s and Bartky’s, comparing and contrasting the main arguments of those three authors might help you construct your evaluation—even though the topic may not have asked for comparison/contrast and the lists of similarities and differences you generate may not appear anywhere in the final draft of your paper.

Discovering similarities and differences

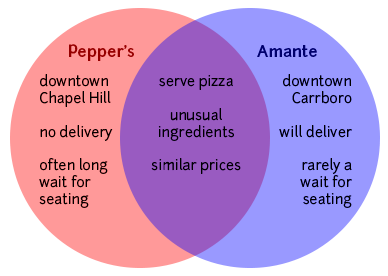

Making a Venn diagram or a chart can help you quickly and efficiently compare and contrast two or more things or ideas. To make a Venn diagram, simply draw some overlapping circles, one circle for each item you’re considering. In the central area where they overlap, list the traits the two items have in common. Assign each one of the areas that doesn’t overlap; in those areas, you can list the traits that make the things different. Here’s a very simple example, using two pizza places:

To make a chart, figure out what criteria you want to focus on in comparing the items. Along the left side of the page, list each of the criteria. Across the top, list the names of the items. You should then have a box per item for each criterion; you can fill the boxes in and then survey what you’ve discovered.

Here’s an example, this time using three pizza places:

As you generate points of comparison, consider the purpose and content of the assignment and the focus of the class. What do you think the professor wants you to learn by doing this comparison/contrast? How does it fit with what you have been studying so far and with the other assignments in the course? Are there any clues about what to focus on in the assignment itself?

Here are some general questions about different types of things you might have to compare. These are by no means complete or definitive lists; they’re just here to give you some ideas—you can generate your own questions for these and other types of comparison. You may want to begin by using the questions reporters traditionally ask: Who? What? Where? When? Why? How? If you’re talking about objects, you might also consider general properties like size, shape, color, sound, weight, taste, texture, smell, number, duration, and location.

Two historical periods or events

- When did they occur—do you know the date(s) and duration? What happened or changed during each? Why are they significant?

- What kinds of work did people do? What kinds of relationships did they have? What did they value?

- What kinds of governments were there? Who were important people involved?

- What caused events in these periods, and what consequences did they have later on?

Two ideas or theories

- What are they about?

- Did they originate at some particular time?

- Who created them? Who uses or defends them?

- What is the central focus, claim, or goal of each? What conclusions do they offer?

- How are they applied to situations/people/things/etc.?

- Which seems more plausible to you, and why? How broad is their scope?

- What kind of evidence is usually offered for them?

Two pieces of writing or art

- What are their titles? What do they describe or depict?

- What is their tone or mood? What is their form?

- Who created them? When were they created? Why do you think they were created as they were? What themes do they address?

- Do you think one is of higher quality or greater merit than the other(s)—and if so, why?

- For writing: what plot, characterization, setting, theme, tone, and type of narration are used?

- Where are they from? How old are they? What is the gender, race, class, etc. of each?

- What, if anything, are they known for? Do they have any relationship to each other?

- What are they like? What did/do they do? What do they believe? Why are they interesting?

- What stands out most about each of them?

Deciding what to focus on

By now you have probably generated a huge list of similarities and differences—congratulations! Next you must decide which of them are interesting, important, and relevant enough to be included in your paper. Ask yourself these questions:

- What’s relevant to the assignment?

- What’s relevant to the course?

- What’s interesting and informative?

- What matters to the argument you are going to make?

- What’s basic or central (and needs to be mentioned even if obvious)?

- Overall, what’s more important—the similarities or the differences?

Suppose that you are writing a paper comparing two novels. For most literature classes, the fact that they both use Caslon type (a kind of typeface, like the fonts you may use in your writing) is not going to be relevant, nor is the fact that one of them has a few illustrations and the other has none; literature classes are more likely to focus on subjects like characterization, plot, setting, the writer’s style and intentions, language, central themes, and so forth. However, if you were writing a paper for a class on typesetting or on how illustrations are used to enhance novels, the typeface and presence or absence of illustrations might be absolutely critical to include in your final paper.

Sometimes a particular point of comparison or contrast might be relevant but not terribly revealing or interesting. For example, if you are writing a paper about Wordsworth’s “Tintern Abbey” and Coleridge’s “Frost at Midnight,” pointing out that they both have nature as a central theme is relevant (comparisons of poetry often talk about themes) but not terribly interesting; your class has probably already had many discussions about the Romantic poets’ fondness for nature. Talking about the different ways nature is depicted or the different aspects of nature that are emphasized might be more interesting and show a more sophisticated understanding of the poems.

Your thesis

The thesis of your comparison/contrast paper is very important: it can help you create a focused argument and give your reader a road map so they don’t get lost in the sea of points you are about to make. As in any paper, you will want to replace vague reports of your general topic (for example, “This paper will compare and contrast two pizza places,” or “Pepper’s and Amante are similar in some ways and different in others,” or “Pepper’s and Amante are similar in many ways, but they have one major difference”) with something more detailed and specific. For example, you might say, “Pepper’s and Amante have similar prices and ingredients, but their atmospheres and willingness to deliver set them apart.”

Be careful, though—although this thesis is fairly specific and does propose a simple argument (that atmosphere and delivery make the two pizza places different), your instructor will often be looking for a bit more analysis. In this case, the obvious question is “So what? Why should anyone care that Pepper’s and Amante are different in this way?” One might also wonder why the writer chose those two particular pizza places to compare—why not Papa John’s, Dominos, or Pizza Hut? Again, thinking about the context the class provides may help you answer such questions and make a stronger argument. Here’s a revision of the thesis mentioned earlier:

Pepper’s and Amante both offer a greater variety of ingredients than other Chapel Hill/Carrboro pizza places (and than any of the national chains), but the funky, lively atmosphere at Pepper’s makes it a better place to give visiting friends and family a taste of local culture.

You may find our handout on constructing thesis statements useful at this stage.

Organizing your paper

There are many different ways to organize a comparison/contrast essay. Here are two:

Subject-by-subject

Begin by saying everything you have to say about the first subject you are discussing, then move on and make all the points you want to make about the second subject (and after that, the third, and so on, if you’re comparing/contrasting more than two things). If the paper is short, you might be able to fit all of your points about each item into a single paragraph, but it’s more likely that you’d have several paragraphs per item. Using our pizza place comparison/contrast as an example, after the introduction, you might have a paragraph about the ingredients available at Pepper’s, a paragraph about its location, and a paragraph about its ambience. Then you’d have three similar paragraphs about Amante, followed by your conclusion.

The danger of this subject-by-subject organization is that your paper will simply be a list of points: a certain number of points (in my example, three) about one subject, then a certain number of points about another. This is usually not what college instructors are looking for in a paper—generally they want you to compare or contrast two or more things very directly, rather than just listing the traits the things have and leaving it up to the reader to reflect on how those traits are similar or different and why those similarities or differences matter. Thus, if you use the subject-by-subject form, you will probably want to have a very strong, analytical thesis and at least one body paragraph that ties all of your different points together.

A subject-by-subject structure can be a logical choice if you are writing what is sometimes called a “lens” comparison, in which you use one subject or item (which isn’t really your main topic) to better understand another item (which is). For example, you might be asked to compare a poem you’ve already covered thoroughly in class with one you are reading on your own. It might make sense to give a brief summary of your main ideas about the first poem (this would be your first subject, the “lens”), and then spend most of your paper discussing how those points are similar to or different from your ideas about the second.

Point-by-point

Rather than addressing things one subject at a time, you may wish to talk about one point of comparison at a time. There are two main ways this might play out, depending on how much you have to say about each of the things you are comparing. If you have just a little, you might, in a single paragraph, discuss how a certain point of comparison/contrast relates to all the items you are discussing. For example, I might describe, in one paragraph, what the prices are like at both Pepper’s and Amante; in the next paragraph, I might compare the ingredients available; in a third, I might contrast the atmospheres of the two restaurants.

If I had a bit more to say about the items I was comparing/contrasting, I might devote a whole paragraph to how each point relates to each item. For example, I might have a whole paragraph about the clientele at Pepper’s, followed by a whole paragraph about the clientele at Amante; then I would move on and do two more paragraphs discussing my next point of comparison/contrast—like the ingredients available at each restaurant.

There are no hard and fast rules about organizing a comparison/contrast paper, of course. Just be sure that your reader can easily tell what’s going on! Be aware, too, of the placement of your different points. If you are writing a comparison/contrast in service of an argument, keep in mind that the last point you make is the one you are leaving your reader with. For example, if I am trying to argue that Amante is better than Pepper’s, I should end with a contrast that leaves Amante sounding good, rather than with a point of comparison that I have to admit makes Pepper’s look better. If you’ve decided that the differences between the items you’re comparing/contrasting are most important, you’ll want to end with the differences—and vice versa, if the similarities seem most important to you.

Our handout on organization can help you write good topic sentences and transitions and make sure that you have a good overall structure in place for your paper.

Cue words and other tips

To help your reader keep track of where you are in the comparison/contrast, you’ll want to be sure that your transitions and topic sentences are especially strong. Your thesis should already have given the reader an idea of the points you’ll be making and the organization you’ll be using, but you can help them out with some extra cues. The following words may be helpful to you in signaling your intentions:

- like, similar to, also, unlike, similarly, in the same way, likewise, again, compared to, in contrast, in like manner, contrasted with, on the contrary, however, although, yet, even though, still, but, nevertheless, conversely, at the same time, regardless, despite, while, on the one hand … on the other hand.

For example, you might have a topic sentence like one of these:

- Compared to Pepper’s, Amante is quiet.

- Like Amante, Pepper’s offers fresh garlic as a topping.

- Despite their different locations (downtown Chapel Hill and downtown Carrboro), Pepper’s and Amante are both fairly easy to get to.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

On the relationship between speech and writing with implications for behavioral approaches to teaching literacy

- PMID: 22477610

- PMCID: PMC2748615

- DOI: 10.1007/BF03392853

Two theories of the relationship between speech and writing are examined. One theory holds that writing is restricted to a one-way relationship with speech-a unidirectional influence from speech to writing. In this theory, writing is derived from speech and is simply a representation of speech. The other theory holds that additional, multidirectional influences are involved in the development of writing. The unidirectional theory focuses on correspondences between speech and writing while the multidirectional theory directs attention to the differences as well as the similarities between speech and writing. These theories have distinctive pedagogical implications. Although early behaviorism may be seen to have offered some support for the unidirectional theory, modern behavior analysis should be seen to support the multidirectional theory.

Relationship and Difference Between Speech and Writing in Linguistics

Back to: Pedagogy of English- Unit 4

Many differences exist between the written language and the spoken language. These differences impact subtitling which is a practice that has become highly prevalent in the modern age. It is a process used to translate what the speaker is saying for those of other languages or who are deaf.

The main difference between written and spoken languages is that written language is comparatively more formal and complex than spoken language. Some other differences between the two are as follows:

Writing is more permanent than the spoken word and is changed less easily. Once something is printed, or published on the internet, it is out there for the world to see permanently. In terms of speaking, this permanency is present only if the speaker is recorded but they can restate their position.

Apart from formal speeches, spoken language needs to be produced instantly. Due to this, the spoken word often includes repetitions, interruptions, and incomplete sentences. As a result, writing is more polished.

Punctuation

Written language is more complex than spoken language and requires punctuation. Punctuation has no equivalent in spoken language.

Speakers can receive immediate feedback and can clarify or answer questions as needed but writers can’t receive immediate feedback to know whether their message is understood or not apart from text messages, computer chats, or similar technology.

Writing is used to communicate across time and space for as long as the medium exists and that particular language is understood whereas speech is more immediate.

Use of Slang

Written and spoken communication uses different types of language. For instance, slang and tags are more often used when speaking rather than writing.

Speaking and listening skills are more prevalent in spoken language whereas writing and reading skills are more prevalent in written language.

Tone and pitch are often used in spoken language to improve understanding whereas, in written language, only layout and punctuation are used.

These are the major differences between spoken language and written language.

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Short Reports

Short Reports offer exciting novel biological findings that may trigger new research directions.

See Journal Information »

The human auditory system uses amplitude modulation to distinguish music from speech

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Psychology, New York University, New York, New York, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Psychology, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Affiliation Instituto de Neurobiología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Juriquilla, Querétaro, México

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Department of Psychology, New York University, New York, New York, United States of America, Ernst Struengmann Institute for Neuroscience, Frankfurt am Main, Germany, Center for Language, Music, and Emotion (CLaME), New York University, New York, New York, United States of America, Music and Audio Research Lab (MARL), New York University, New York, New York, United States of America

- Andrew Chang,

- Xiangbin Teng,

- M. Florencia Assaneo,

- David Poeppel

- Published: May 28, 2024

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3002631

- Reader Comments

Music and speech are complex and distinct auditory signals that are both foundational to the human experience. The mechanisms underpinning each domain are widely investigated. However, what perceptual mechanism transforms a sound into music or speech and how basic acoustic information is required to distinguish between them remain open questions. Here, we hypothesized that a sound’s amplitude modulation (AM), an essential temporal acoustic feature driving the auditory system across processing levels, is critical for distinguishing music and speech. Specifically, in contrast to paradigms using naturalistic acoustic signals (that can be challenging to interpret), we used a noise-probing approach to untangle the auditory mechanism: If AM rate and regularity are critical for perceptually distinguishing music and speech, judging artificially noise-synthesized ambiguous audio signals should align with their AM parameters. Across 4 experiments ( N = 335), signals with a higher peak AM frequency tend to be judged as speech, lower as music. Interestingly, this principle is consistently used by all listeners for speech judgments, but only by musically sophisticated listeners for music. In addition, signals with more regular AM are judged as music over speech, and this feature is more critical for music judgment, regardless of musical sophistication. The data suggest that the auditory system can rely on a low-level acoustic property as basic as AM to distinguish music from speech, a simple principle that provokes both neurophysiological and evolutionary experiments and speculations.

Citation: Chang A, Teng X, Assaneo MF, Poeppel D (2024) The human auditory system uses amplitude modulation to distinguish music from speech. PLoS Biol 22(5): e3002631. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3002631

Academic Editor: Manuel S. Malmierca, Universidad de Salamanca, SPAIN

Received: October 15, 2023; Accepted: April 17, 2024; Published: May 28, 2024

Copyright: © 2024 Chang et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All stimuli, experimental programs, raw data, and analysis codes have been deposited at a publicly available OSF repository ( https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/RDTGC ).

Funding: A.C. was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein Postdoctoral Individual National Research Service Award, National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders/National Institutes of Health (F32DC018205) and Leon Levy Scholarships in Neuroscience, Leon Levy Foundation/New York Academy of Sciences. X.T. was supported by Improvement on Competitiveness in Hiring New Faculties Funding Scheme, the Chinese University of Hong Kong (4937113). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Music and speech, two complex auditory signals, are frequently compared across many levels of biological sciences, ranging from system and cognitive neuroscience to comparative and evolutionary biology. As acoustic signals, they exhibit a range of interesting similarities (e.g., temporal structure [ 1 , 2 ]) and differences (e.g., music, but not speech, features discrete pitch intervals). In the brain, they are processed by both shared [ 3 – 6 ] and specialized [ 7 – 10 ] neural substrates. However, which acoustic information underpins a sound to be perceived as music or speech remains an open question.

One way to address the broader question of how music and speech are organized in the human mind/brain is to capitalize on ecologically valid, “real” signals, a more holistic approach. That strategy has the advantage of working with stimulus materials that are naturalistic and, therefore, engage the perceptual and neural systems in a typical manner (e.g., [ 11 , 12 ]). The disadvantage of adopting such an experimental attack is that it can be quite challenging to identify and isolate the components and processes that underpin perception. Here, we pursue the alternative reductionist approach: parametrically generating and manipulating ambiguous auditory stimuli with basic, analytically tractable amplitude modulation (AM) features. If the auditory system distinguishes music and speech according to the low-level acoustic parameters, the music/speech judgment on artificially noise-synthesized ambiguous audio signals should align with their AM parameters, even if no real music or speech is contained in the signal.

In the neural domain, AM is a basic acoustic feature that drives auditory neuronal circuits and underlying complex communicative functions across both humans and nonhuman animals. At the micro- and meso-levels, single-cell and population recording of auditory cortex neurons in nonhuman animals demonstrated various mechanisms to encode AM features (e.g., [ 13 , 14 ]). At the macro-level, human neuroimaging studies showed that the acoustic AM synchronizes the neural activities at auditory cortex and correlated with perception and speech comprehensions (e.g., [ 15 – 18 ]). A critical but underexplored gap is the mechanism of how low-level AM features affect a sound to be processed as a complex high-level signal such as music and speech.

Our experiments tested the hypothesis that a remarkably basic acoustic parameter can, in part , determine a sound to be perceptually judged as music or speech. The conjecture is that AM ( Fig 1 ) is one crucial acoustic factor to distinguish music and speech. Previous studies that quantified many hours and a wide variety of music and speech recordings showed distinct peak AM rates in the modulation spectrum: music peaks at 1 to 2 Hz and speech peaks at 3.5 to 5.5 Hz [ 19 – 21 ]. Consistent with those findings, these rate differences are also observed in spontaneous speech and music production [ 22 ]. Next, temporal regularity of AM could also be important, as music is often metrically organized with an underlying beat, whereas speech is not periodic and is better considered quasirhythmic [ 20 , 23 ]. Also, supporting the relevant role played by AM, neuroimaging evidence showed that temporally scrambled but spectrally intact signals weaken neural activity in speech- or music-related cortical clusters [ 9 , 24 ]. Finally, a preliminary study ( n = 12) showed that listeners were able to near-perfectly categorize 1-channel noise-vocoded realistic speech and music excerpts [ 19 ]. However, the noise-vocoding approach was insufficient to mechanistically pinpoint the degree to which AM rate and regularity contribute to music/speech distinction, as this manipulation preserved all the envelope temporal features above and beyond rate and regularity. For example, onset sharpness of speech envelope is encoded by the spoken language cortical network (superior temporal gyrus) and critical to comprehension [ 25 – 27 ]; also, the onset sharpness of the music envelope is crucial for timbre perception, e.g., a piano tone typically has a sharper onset than violin. We therefore build on the notion that the AM distinction between music and speech signals appears to be acoustically robust. However, in order to advance our understanding of potential mechanisms, we ask what aspects of the AM influence listeners to make this perceptual distinction. How acoustically reduced and simple can a signal be and still be judged to be speech or music?

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3002631.g001

Based on the literature, we hypothesized that stimuli with a lower-in-modulation-frequency and narrower-in-variance peak (i.e., higher temporal regularity, more isochrony) in the AM spectrum would be judged as music, while those with higher and broader peaks (i.e., lower temporal regularity) as speech. If these hypotheses are plausible, artificial sounds synthesized with the designated AM properties should be perceptually categorized accordingly. This noise-probing approach is conceptually similar to the reverse-correlation approach in studies seeking to understand what features are driving the “black-box” perceptual system (e.g., [ 28 , 29 ]). In short, we synthesized stimuli with specific AM parameters by “reversing” a pipeline for analyzing realistic, naturalistic music and speech recordings ( Fig 1B ). First, we used a lognormal function that resembles the empirically determined AM spectra reported in previous studies [ 19 , 20 ]; this function permits the independent manipulation of peak frequency and temporal regularity parameters. Next, after transforming each AM spectrum into a time-domain AM signal (inverse Fourier transform), that signal was used to modulate a flat white noise (i.e., low-noise noise) carrier to generate a 4-s duration experimental stimulus. This approach, importantly, eliminates typical spectral features of both music and speech. In our 4 online experiments, participants were told that each stimulus came from a real music or speech recording but was synthesized with noise, and their task was to judge whether it was music or speech. Although none of the stimuli sounded like real music or speech, participants’ judgments revealed how well each stimulus matched their internal representation of one or the other perceptual category.

In Experiment 1, we manipulated peak AM frequency while σ (the regularity parameter, or the width of the peak of the AM spectrum; see Methods ) was fixed at 0.35 (the value was chosen as it sounded the most “natural” or “comfortable” according to the informal feedback from colleagues in the lab). Stimuli were presented one at a time, and participants were requested to judge whether a stimulus is music or speech. Data from 129 participants were included in the analyses. The overall responses are presented in Fig 2A . To investigate the effect of peak frequencies, each participant’s responses (speech = 1, music = 0) were linearly regressed on the peak frequencies (mean ± standard error of R 2 = 0.53 ± 0.03; Fig 2B ). The response slopes were significantly above 0 ( Fig 2C ; t (128) = 7.70, p < 10 −11 , Cohen’s d = 0.68), suggesting that people judge sounds with a higher peak AM frequency as speech and sounds with a lower peak AM frequency as music. We then explored the association of this judgment with participants’ musical sophistication and found that the participants with a higher General Musical Sophistication score (Gold-MSI [ 30 ]; see Methods ) were more likely to have a higher response slope ( r (127) = 0.17, p = 0.056; but after removing 1 outlier: r (126) = 0.20, p = 0.023; Fig 2D ). We further split the participants by slope at 0 and performed an unequal-variance 2-sample t test without removing that 1 outlier. This analysis confirmed that the participants with a positive response slope have higher General Musical Sophistication scores than the participants with a negative slope ( t (57.25) = 2.96, p = 0.005, Cohen’s d = 0.57). We further correlated the response slope with each subscale of the musical sophistication index, but none of them were significant (unsigned r (127) < 0.16, p > 0.075). While null effects should be interpreted with caution, this suggests that general musical sophistication, rather than a specific musical aspect, is driving the outcome. In short, the findings show that the sounds with a higher peak AM frequency are more likely to be judged as speech and lower as music, and this tendency is positively associated with participants’ general musical sophistication.

( A ) The music vs. speech judgment response of each participant at different levels of AM peak frequencies. ( B ) Fitted regression lines of each participant’s response. ( C ) Each dot represents the response slope on peak frequencies of a participant, and the bar and the error bars represent the mean ± standard error. The participants’ response slopes were significantly above 0, suggesting that the participants tend to judge the stimuli with a higher peak AM frequency as speech and lower as music. ( D ) The response slopes and the General Musical Sophistication score of the participants were positively correlated, suggesting that the musically more sophisticated participants are more likely to judge the stimuli with a higher peak AM frequency as speech and a lower peak frequency as music. Note that the gray circle marks the outlier, and the regression line and the p -value reported on the figure were based on the analysis without the outlier. Underlying data and scripts are available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/RDTGC and in S1 Data .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3002631.g002

Note that we attempted to fit the data with a logistic psychometric function. Although the findings were consistent as the fitted slopes of the logistic model were also significantly above 0 ( t (128) = 6.85, p < 10 −9 ), suggesting the sounds with a higher peak AM frequency are more likely to be judged as speech over music, the R 2 of the logistic model were much lower than the linear model (mean R 2 difference: 0.19), so did the following experiments (see Methods for more details), suggesting that the linear model was a more appropriate model. Therefore, only the linear models were interpreted.

To investigate the effect of temporal regularity, in Experiment 2, we manipulated AM temporal regularity (σ) at 3 peak AM frequencies (1, 2.5, and 4 Hz, which roughly correspond to the AM range of music, a midpoint, and speech). The procedure was identical to Experiment 1, and data from 48 participants were included. The overall responses are presented in Fig 3A . Each participant’s responses were linearly regressed on the σ under each peak frequency ( R 2 = 0.37 ± 0.02; Fig 3B ). The response slopes were significantly above 0 for the peak frequency at 1 Hz ( t (47) = 6.19, p < 10 −6 , Cohen’s d = 0.89) and 2.5 Hz ( t (47) = 6.37, p < 10 −7 , Cohen’s d = 0.92), suggesting that listeners tend to judge sounds with lower temporal regularity (higher σ) as speech and higher regularity as music ( Fig 3C ). Note that this pattern was the opposite for the peak frequency at 4 Hz, with a lower effect size ( t (47) = −3.34, p = 0.016, Cohen’s d = 0.48). It suggests that the association between temporal regularity and the music judgment is conditional on the low-to-mid peak AM frequency range, and the influence of temporal regularity is weaker when peak AM frequency is in the AM range of speech. We also examined the associations between participants’ musical sophistication levels and response slope, but no correlation was significant ( Fig 3D ; unsigned r (46) < 0.13, p = 0.404).

( A ) The music vs. speech judgment response of each participant at different levels of temporal regularity (σ). ( B ) Fitted regression lines of each participant’s response. ( C ) The participants’ response slopes on σ were significantly above 0 for the peak AM frequencies at 1 and 2.5 Hz but not 4 Hz. This suggests that participants tend to judge the temporally more regular stimuli as music and irregular as speech, but this tendency was not observed when the peak frequency was as high as 4 Hz. ( D ) The response slopes and the General Musical Sophistication scores were not correlated at any peak AM frequencies. Underlying data and scripts are available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/RDTGC and in S1 Data . n . s ., nonsignificant.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3002631.g003

The dichotomy of the behavioral judgment that our task imposes could be a concern because it only allows a stimulus to be judged as music or speech, while ignoring other possible categories. It is, to be sure, reasonable to directly contrast music and speech, as these are arguably among the most dominant high-level auditory forms in human cognition, sharing many commonalities (cf., [ 1 , 9 ]), and a discrimination task between two categories is usually considered psychophysically more powerful than two separate detection tasks on each category [ 31 ]. However, other auditory categories, such as animal calls and environmental sounds, are critical in human perception as well. Therefore, we tested the robustness of the findings of Experiments 1 and 2 by replicating them with detection tasks, and we investigated whether there were effects specific to music or speech.

In Experiment 3, peak AM frequency was manipulated with σ fixed at 0.35; 80 participants were included in the analyses. In the “music detection” task, participants were instructed that 50% of the stimuli were music and 50% were not music (“others”), and they were asked to judge whether it was music or something else. For the “speech detection” task, the task was analogous. The 50% instruction was added to prevent participants with a strong response bias. Each participant performed both tasks with the same stimuli. The overall responses are presented in Fig 4A . Each participant’s responses (music or speech = 1, others = 0) were linearly regressed on peak frequency for each task ( R 2 = 0.68 ± 0.02; Fig 4B ). For the speech task, the response slopes were significantly above 0 ( t (79) = 12.79, p < 10 −20 , Cohen’s d = 1.43; Fig 4C ), suggesting that the sounds with a higher peak AM frequencies are more likely to be judged as speech over others. Musical sophistication did not correlate with the speech response slope ( r (78) = 0.04, p = 0.717; Fig 4D ). For the music task, the response slope was not significantly different from 0 ( t (79) = 0.49, p = 0.628, Cohen’s d = 0.05; Fig 4C ). Interestingly, there was a significant correlation suggesting that the more musically sophisticated participants are more likely to judge the sound with a lower peak AM frequency as music ( r (78) = −0.28, p = 0.011; Fig 4D ), and this is again confirmed by the unequal-variance 2-sample t test between split-data at slope equals to 0 ( t (72.57) = 2.66, p = 0.010, Cohen’s d = 0.58). We also correlated the response slope with each subscale; however, once again, none of them passed the Bonferroni-corrected statistical threshold at 0.01 (unsigned r (78) < 0.28, p > 0.013). Together, the effect of peak AM frequency reported in Experiment 1 is robustly replicated for the speech judgment, but the music judgment was conditional on participants’ general musical sophistication.

Results of Experiments 3 (A-D) and 4 (E-H). ( A ) The “music vs. others” and “speech vs. others” judgment response of each participant at different levels of peak AM frequencies. ( B ) The fitted regression line of each participant’s response. ( C ) The participants’ response slopes on peak frequencies were significantly above 0 for the speech task but not for the music task, suggesting that the participants tend to judge the stimuli with a higher peak AM frequency as speech. ( D ) The response slopes and the General Musical Sophistication scores of the participants were positively correlated for the music task but not for the speech task, suggesting that the musically more sophisticated participants are more likely to judge the stimuli with a lower peak AM frequency as music. ( E - H ) The same format as above, but at different levels of temporal regularity (σ). The participants tend to judge the stimuli with a higher temporal regularity as music. Underlying data and scripts are available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/RDTGC and in S1 Data . n . s ., nonsignificant.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3002631.g004

In Experiment 4, AM temporal regularity was manipulated while the peak AM frequency was fixed at 2 Hz (equally likely to be judged as music or speech, according to the previous experiments). The tasks were as in Experiment 3, and data from 78 participants were included. The overall responses are shown in Fig 4E . Each participant’s responses were linearly regressed on σ for each task ( R 2 = 0.32 ± 0.02; Fig 4F ). For the music task, the response slope was significantly below 0 ( t (77) = -4.95, p < 10 −5 , Cohen’s d = 0.56; Fig 4G ), suggesting that people tend to judge the sounds with higher temporal regularity (lower σ) as music. For the speech task, the response slopes were slightly above 0 but not reaching the statistical threshold ( t (77) = 1.89, p = 0.063, Cohen’s d = 0.21; Fig 4G ). We did not observe any associations between participants’ musical sophistication and response slope (unsigned r (76) < 0.13, p > 0.293; Fig 4H ). Together, the effect of AM temporal regularity reported in Experiment 2 was robustly replicated for music but only a trend was observed for speech.

These surprising findings and their replications show that listeners use acoustic amplitude modulations in sounds, one of the most basic features, fundamental to human auditory perception, to judge whether a sound is “like” music or speech, even when spectral features are eliminated. We show that peak AM frequency can affect high-level categorization: Sounds with a higher peak AM frequency tend to be judged as speech, those with a lower peak as music, especially among musically sophisticated participants. This pattern is consistent with previous quantifications of natural music recordings showing that the peak AM frequency of music is lower than speech [ 19 ]. This result might arise because of participants’ (implicit) knowledge of this acoustic feature. We note that, while the effect of peak AM frequency in Experiment 1 was robustly replicated in the speech task in Experiment 3, in the music task, the effect was more salient among musically sophisticated participants but not visible when pooling all participants. In other words, peak AM frequency is a universal cue for speech but not for music. A possible explanation is that this effect depends on listeners’ experience or sophistication with music or speech sounds. While our participants exhibited a ceiling effect for speech (as university students, every listener can be classified as an “expert” in speech), their musical sophistication scores appeared lower than the norm (Experiment 3 versus Müllensiefen and colleagues [ 30 ]: 71.39 versus 81.58, Cohen’s d = 0.49; but it is similar to other studies (e.g., [ 32 , 33 ])). The potential effect of speech expertise would need to be examined, for example, in future developmental studies in which expertise can be more carefully controlled.

Temporal regularity (and, in the extreme, isochrony, if σ = 0) of AM also has an effect: Sounds with more regular modulation are more likely to be judged as music than speech. This is consistent with the fact that Western music is usually metrically organized while speech is quasirhythmic [ 20 , 23 ]. There are a few aspects worth discussing. First, this effect is more relevant to music than to speech. The detection tasks in Experiment 4 show that the effect of temporal regularity is only robustly observed for music but not for speech. It appears that temporal regularity is a more prevalent principle than peak AM frequency to judge a sound as music as this effect does not depend on the listener’s musical sophistication. Second, in Experiment 2, the effect of temporal regularity was slightly opposite when the peak AM frequency was at 4 Hz. A possible explanation is that temporal regularity might be less critical for distinguishing music and speech when peak AM frequency is already in the canonical speech range 3.5 to 5.5 Hz [ 19 – 21 ]. Last but not least, while temporal regularity in the current parameter range did not drastically influence the auditory judgments, the current data demonstrate a clear pattern across participants: A sound with a more temporally regular AM is more like music.

AM is one of the most fundamental building blocks for auditory perception, and especially so for human speech. While frequency/spectral information is critical for auditory object identification, pitch perception, and timbre, AM is considered a key information-bearing component and critical for speech intelligibility [ 34 , 35 ]. AM, especially around the 2-4 Hz, is faithfully encoded by neurons in the primary auditory cortex [ 14 , 36 ]. While previous studies have demonstrated that temporal envelope information alone is arguably sufficient for speech perception (e.g., [ 37 ]), the current findings further show that AM rate can be used to identify a sound as speech or not (i.e., Fig 4C ). Relatedly, AM rate helps identify music, at least among musically sophisticated listeners. This could be for different reasons. First, music has salient features in both time and frequency domains. A recent survey showed that adults explicitly consider both AM regularity (rhythm/beat) and melody (frequency/spectral domain), but not AM rate, as being the primary acoustic features for distinguishing speech and song [ 38 ]. This is consistent with the current finding that people rely on AM regularity more than rate to identify music. Second, the association between AM rate and music perception might require musical experience. This is consistent with the neural entrainment studies showing that the fidelity of auditory cortex entraining to music rhythm is positively associated with the musical expertise of the listeners [ 25 , 39 ]. Together, our data provide the empirical advance that AM rate or regularity alone, regardless of the fine temporal features (e.g., onset sharpness) preserved by the noise-vocoded approach [ 19 ], have an effect on the music/speech judgment. Given that the AM rate and regularity are processed early in the auditory cortex [ 14 ], notably prior to superior temporal gyrus encoding of speech onset (e.g., [ 26 , 27 ]), AM rate or regularity should have more decisive roles than temporal envelope features for distinguishing music and speech at an early stage of the auditory cortical pathway.

The current study has four noteworthy limitations. First, the lognormal function can resemble the average AM spectrum of many hours of music or speech recordings [ 19 ], but it does not necessarily approximate individual recordings well. Second, the current forced-choice task design can only demonstrate how acoustic features affect the auditory judgments , but whether participants subjectively experienced the percepts of our stimuli as “reduced” forms of music or speech is unclear, as the rich spectral and timbral features of typical music or speech were by design eliminated from the stimuli. Third, while the current experimental design only showed the influences of AM rate and regularity on distinguishing music and speech, we did not compare their influences to those of other acoustic features. Although spectral or frequency modulation, orthogonal to AM, is another promising acoustic feature fundamental to auditory perception, the current study focuses on only the AM aspect as it has been demonstrated distinct between music and speech acoustics while the spectral aspect has not. Lastly, the factors that contributed to the substantial individual differences in music-related tasks remain unclear, and musical sophistication only partially accounts for it. Other perceptual and cognitive factors (e.g., preference for fast or slow music, unawareness of hearing loss among young adults) and experimental factors (e.g., whether the participants were exposed to any specific music or speech in the environment while performing our experiment online, remotely, and on their own) likely contributed to the individual differences as well. Nevertheless, our reductionist approach demonstrates the striking fact that music or speech judgment starts from basic acoustic features such as AM.

A related phenomenon that builds on the role of temporal structure can be illuminated by these data. The speech-to-song illusion demonstrates that, by looping a (real) speech excerpt, the perceptual judgment can gradually shift from speech toward song [ 40 – 42 ]. The effects reported here are consistent with the speech-to-song illusion: The low frequency power of the AM spectrum would emerge from the repeating-segment periodicity and, therefore, bias the judgment toward music. Supporting this view, this illusion disappears if speech is temporally jumbled in every repetition [ 40 ], which eliminates low-frequency periodicity across repetitions. Furthermore, consistent with our findings, the strength of the illusion is also positively associated with beat regularity and participants’ musical expertise [ 41 , 43 – 45 ].

The properties of AM that support the distinction of music and speech merit consideration in the context of human evolution and neurophysiology. Group cohesion and interpersonal interaction have been hypothesized as one primary function of music [ 46 – 53 ]. If music serves as an auditory cue for coordinating group behaviors, predictable temporal regularity at the optimal rate for human movements and audiomotor synchronization (1 to 2 Hz; [ 54 – 56 ]) would be important. And, in fact, motor brain networks are involved while processing auditory rhythms (e.g., [ 57 – 64 ]). The AM rate of speech, analogously, has been attributed to the neurophysiological properties of the specialized auditory-motor oscillatory network for speech perception and production, as well as the associated biomechanics of the articulatory movements [ 17 , 20 , 65 , 66 ]. Consistent with these data patterns, perceptual studies have also shown a general pattern that music versus speech task performance is optimal with rates ranging around 0.5 to 6.7 and 2 to 9 Hz, respectively [ 67 , 68 ].

The experimental results we present demonstrate that human listeners can use a basic acoustic feature fundamental to auditory perception to judge whether a sound is like music or speech. These data reveal a potential processing principle that invites both neurophysiological and evolutionary experiments and speculations that could further address the long-lasting questions on the comparison between music and speech in both the humanities and the sciences.

Resource availability

All stimuli, experimental programs, raw data, and analysis codes have been deposited at a publicly available OSF repository ( https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/RDTGC ).

Participants

The participants were students at New York University who signed up for the studies via the SONA online platform and received course credit for completing the experiments. The local Institutional Review Board (New York University’s Committee on Activities Involving Human Subjects) approved all protocols (IRB-FY2016-1357), in complete adherence to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided informed consent via an online form. Participants had self-reported normal hearing, were at least 18 years old, and reported no cognitive, developmental, neurological, psychiatric, or speech-language disorders. The total number of online participants was 488, and the data of 335 participants (208 females, 122 males, 5 other/prefer not to say, age range: 18 to 25) were included for analysis (see Quantification and statistical analysis for exclusion criteria, and Results for the sample size of each experiment).

The pipeline to generate audio stimuli with a designated peak AM frequency and temporal regularity parameters is composed of the following steps (resembling an inverse pipeline for analyzing audio recordings), which are conceptually illustrated in Fig 1 .

- An inverse fast Fourier transformation with random phases was applied to an AM spectrum to generate a 20-s time-domain signal with a 44.1-kHz sampling rate, and then it was transformed to an amplitude envelope [ 69 , 70 ].

- The resulting amplitude envelope was used to modulate a 20- to 20,000-Hz low-noise noise (LNN) carrier sound. The LNN is a white noise with a flat amplitude envelope [ 71 , 72 ], which ensures that the amplitude fluctuations of the final stimuli were not caused by the carrier signal.

- The middle 4-s segment of each 20-s amplitude-modulated LNN was extracted as a stimulus.

- There were 100, 50, 50, and 50 stimuli generated for each condition of Experiments 1 to 4, respectively, and the root-mean-square values of all the stimuli were equalized within each experiment. All steps were performed using MATLAB R2020a.

The experiments were programmed on PsychoPy Builder (v2020.1.2) and executed on the Pavlovia.org platform.

The participants were required to perform the experiment using a browser on their personal computer, in a quiet environment with headphones on, and each listener could set the audio volume at a comfortable level. First, only those participants who passed a headphone screening task (see below) could proceed. Next, the practice phase included 4 trials; the AM parameters of these stimuli were within the range of, but not identical to, the parameter values used in the subsequent testing phase. On each practice trial, a stimulus was presented, and then participants were asked to make a binary judgment by clicking a button on the screen, without time limit. After the response, the next trial started. A probe trial was inserted in the practice phase, which presented 1 to 4 brief tones without warning in a 2-s window with random stimulus-onset asynchronies, and the participants were requested to indicate the number of tones by pressing the corresponding key. Participants could repeat the practice phase until they felt comfortable to proceed to the testing phase. Only in Experiments 3 and 4, a practice phase was inserted prior to each of the first music and speech blocks.

In the testing phase, for Experiments 1 and 2, for each participant, a set of 150 unique stimuli (15 or 10 per condition in Experiments 1 or 2, respectively) were randomly drawn from the stimulus pool, and they were randomly ordered within each of the first and second half of the experiment, resulting in a total of 300 testing trials. There was no cue between two halves of the experiment. The participants were not instructed regarding the occurrence rates of “music” or “speech.”

For Experiments 3 and 4, within each of the first and second halves of the experiment, there were 1 music block and 1 speech block, randomly ordered. Within each block, there were 75 unique stimuli (15 per condition) randomly drawn from the stimulus pool, and the same set of stimuli was used for all 4 blocks for each participant, resulting in a total of 150 trials for each task and, therefore, totaling 300 testing trials for the entire experiment. Before and during each block, there were text and visual cues on the screen to remind the participants of the current block type. The participants were instructed that 50% of the trials were music or speech and 50% were not music or speech (“others”), respectively, for each block type.

For all the experiments, the procedure of each testing trial was identical to the practice trial. A self-paced break was inserted every 10 trials, and the percentage of progress in the experiment was shown on the screen during the break. Twelve probe trials were mixed with roughly even spaces with the testing trials.

After the experiment, participants were directed to another webpage to anonymously fill out demographic information, the Goldsmiths musical sophistication index, and other background and task-related questions (not analyzed).

Headphone screening task.

The participants were requested to perform a headphone screening task prior to the main task, to ensure that they used headphones to complete our online experiments [ 73 ]. On each trial, participants were asked to identify the quietest tone (3-alternative forced choice) among three 1-s duration 200 Hz pure tones (with 100 ms ramps), including a binaurally in-phase loud tone, an antiphase loud tone, and an in-phase quiet tone of (−6 dB). Stimuli were presented sequentially with counterbalanced orders across 6 trials. Because the antiphase loud tone would be attenuated by phase cancelation in the air if it was played through loudspeakers, the quietest tone can only be correctly identified with headphones. Participants had to perform at least 5 out of 6 trials correctly to proceed.

Goldsmith musical sophistication index (Gold-MSI).

The Gold-MSI is one of the most common and reliable indices and for assessing musicality [ 30 ]. It is composed of 39 questions to assess multiple aspects of music expertise, including active engagement, perceptual abilities, musical training, singing abilities, and emotional responses. The General Musical Sophistication subscale is a general index that covers all the aspects of Gold-MSI, which ranges from 18 to 126; the mean and the standard deviation of the norm (147,633 participants) are 81.58 and 20.62, and the reliability α is 0.926.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Since all participants completed the study online without supervision, we used several exclusion criteria to ensure data quality. (1) The participants who did not complete both the experiment and the questionnaire, who did not pass the headphone screening task, admitted not using headphones throughout the experiment, made the same response for all the trials, or whose probe trial accuracy below 90%, were excluded. These criteria excluded 41, 19, 31, and 23 participants from Experiments 1, 2, 3, and 4. (2) Since the participants were instructed that the occurrence rate of music/speech was 50% in Experiments 3 and 4, the participants whose response biases exceeded 50 ± 15% in any task were excluded. This criterion excluded 16 and 23 participants from Experiments 3 and 4. Statistical test significance was assessed with α = .05, two-tailed. The specific tests used are reported in the Results section. The computations were performed on MATLAB R2020a and R2021b.

Power analysis and sample sizes

As the effect size of this task was unknown, in the Experiment 1, we recruited more than 100 participants to reduce the risk of being underpowered and to estimate the statistical power for the following experiments. Based on the data of Experiment 1, a power analysis showed that the required number of participants was 20 when alpha level was set at 0.05 and statistical power at 0.8, and 36 when alpha level was set at 0.01 and statistical power at 0.9. Therefore, we targeted the sample size of Experiment 2 to be slightly above those levels ( n > 40). Although the tasks of Experiments 3 and 4 were similar to Experiments 1 and 2, the judgment of “speech versus others” and “music versus others” might have a lower statistical power than “music versus speech,” as “others” is not a well-defined category. Therefore, we set the target sample sizes to be double ( n ≈ 80) as the required sample size of alpha at 0.01 and power at 0.9.

Supporting information

S1 data. data underlying the plots in fig 2 – 4 ..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3002631.s001

Acknowledgments

We thank the Poeppel Lab members at New York University, Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics, Ernst Struengmann Institute for Neuroscience, and Benjamin Morillon for their comments and support.

- 1. Patel AD. Music, language, and the brain. Oxford University Press; 2008.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar