An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Workplace Stress and Productivity: A Cross-Sectional Study

1 University of Oklahoma at Tulsa, Tulsa, OK

Rosey Zackula

2 Office of Research, University of Kansas School of Medicine-Wichita, Wichita, KS

Katelyn Dugan

3 Department of Population Health, University of Kansas School of Medicine-Wichita, Wichita, KS

Elizabeth Ablah

Introduction.

The primary purpose of this study was to evaluate the association between workplace stress and productivity among employees from worksites participating in a WorkWell KS Well-Being workshop and assess any differences by sex and race.

A multi-site, cross-sectional study was conducted to survey employees across four worksites participating in a WorkWell KS Well Being workshop to assess levels of stress and productivity. Stress was measured by the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) and productivity was measured by the Health and Work Questionnaire (HWQ). Pearson correlations were conducted to measure the association between stress and productivity scores. T-tests evaluated differences in scores by sex and race.

Of the 186 participants who completed the survey, most reported being white (94%), female (85%), married (80%), and having a college degree (74%). A significant inverse relationship was observed between the scores for PSS and HWQ, r = −0.35, p < 0.001; as stress increased, productivity appeared to decrease. Another notable inverse relationship was PSS with Work Satisfaction subscale, r =−0.61, p < 0.001. One difference was observed by sex; males scored significantly higher on the HWQ Supervisor Relations subscale compared with females, 8.4 (SD 2.1) vs. 6.9 (SD 2.7), respectively, p = 0.005.

Conclusions

Scores from PSS and the HWQ appeared to be inversely correlated; higher stress scores were associated significantly with lower productivity scores. This negative association was observed for all HWQ subscales, but was especially strong for work satisfaction. This study also suggested that males may have better supervisor relations compared with females, although no differences between sexes were observed by perceived levels of stress.

INTRODUCTION

Psychological well-being, which is influenced by stressors in the workplace, has been identified as the biggest predictor of self-assessed employee productivity. 1 The relationship between stress and productivity suggests that greater stress correlates with less employee productivity. 1 , 2 However, few studies have examined productivity at a worksite in relation to stress.

Previous research focused on burnout, job satisfaction, or psychosocial factors and their association with productivity; 3 – 7 all highlight the importance of examining overall stress on productivity. Other studies focused on self-perceived stress and employer-evaluated job performance instead of self-assessed productivity. 8 However, most studies examining this relationship have been occupation specific. 8 , 9 Larger studies examining this relationship were performed in other countries. 1 , 5 , 9 , 10

The purpose of this study was twofold. First, the study sought to elucidate the relationship between stress and productivity in four worksites in Kansas. Second, the study sought to examine potential differences in stress and productivity by sex and race.

Recruitment and Sampling Procedures

The target population was employees from four WorkWell KS worksites. WorkWell KS is a statewide worksite initiative in Kansas that provides leadership and resources for businesses and organizations to support worksite health. Because access to employee emails was unavailable, a URL link to an online survey was sent to the worksite contact, who was responsible for ensuring the distribution of the URL link to a cross-section of employees at the worksite. Following a WorkWell KS workshop (held in Topeka, Kansas on November 6, 2017) attendees from the four worksites were recruited to distribute a link to an online survey to their employees. Workshop attendees were members of wellness committees or were worksite representatives. Employee responses to the online survey were collected through mid-December 2017. No compensation was given for disseminating the survey link or for participating in the study. This study was approved by the University of Kansas School of Medicine-Wichita’s Human Subjects Committee.

Online Survey

The online survey comprised demographic items with two instruments, the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), 11 and the Health and Work Questionnaire (HWQ). 12 Demographic items included employee, sex, race, age, marital status, and highest level of education completed.

Perceived Stress Scale

Stress was measured by the PSS, a 10-item questionnaire designed for use in community samples. The purpose of the instrument is to assess global perceived stress during the past month. Each item is measured with a Likert-type scale (0 = Never, 1 = Almost Never, 2 = Sometimes, 3 = Fairly Often, 4 = Very Often). This scale is reversed on four positively stated questions. Scoring of the PSS is obtained by summing all responses. Results range from zero to 40, with higher PSS scores indicating elevated stress: scores of 0 – 13 are considered low stress, 14 – 26 moderate stress, and 27 – 40 are high perceived stress. The results for perceived stress were used by this study as an indication of psychological well-being.

Health and Work Questionnaire

The HWQ is a 24-item instrument that measures multidimensional worksite productivity. Productivity is assessed by asking respondents how they would describe their efficiency, overall quality of work, or overall amount of work in one week. All items are scaled with Likert-type response anchors, each ranging from 1 to 10 points. Most are positively worded items with response scales from least (scored as a 1) to most favorable (scored as a 10). Exceptions are items 1 and 16 through 24, which are negatively worded and reversed scored. Items are divided into six sub-scales: productivity, concentration/focus, supervisor relations, non-work satisfaction, work satisfaction, and impatience/irritability. As part of the HWQ, employees assessed productivity two ways: on themselves and how their supervisor or co-workers might perceive it. Accordingly, productivity is stratified into a self-assessed sub-score and perceived other-assessed sub-score. HWQ scores are tallied and averaged for each sub-scale, with higher scores generally indicating greater productivity.

The Consent Process

Representatives who participated in the WorkWell KS workshop sent an e-mail to their employees with a request to click on the link and complete the online survey. The link opened the electronic consent, which was the opening remark, followed by the two assessment instruments and the demographic items. Consent was implied by participation in the survey. To encourage survey participation, representatives also sent employees a few e-mail reminders at their own discretion.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis included descriptive statistics, measures of association, and comparisons of survey responses by sex and race. Descriptive statistics comprised response summaries; means and standard deviations were used for continuous variables, while frequency and percentages were used for categorical responses. The relationship between stress and productivity measures were assessed using Pearson correlations. Sex and race comparisons for PSS and HWQ subscales were evaluated using two-sided t-tests; alpha was set at 0.05 as the level of significance. Study participants with missing values were excluded pairwise from the analysis.

Response Rates

Four of nine worksites participated in the study, including two health departments (89 participants), one school district (76 participants), and one non-profit for the medically underserved (21 participants). A total of 188 employees opened the survey link, 186 employees answered the first question of the survey, and 174 employees completed the survey items. The 12 study participants with missing values were excluded from the pairwise analysis. The response rate, defined as those participants who completed the survey, was 58.6% (n = 174). To protect the confidentiality of respondents, data were aggregated and no other comparisons were made by location.

Participants who completed the survey included 174 employees from four worksites in Kansas. Of those who responded, 94% (155 out of 165) reported being white, 85% (142 of 167) reported being female, 81% (124 of 153) reported being between 30 and 59 years, and 60% (99 of 166) reported having a bachelor’s degree or higher ( Table 1 ).

Participant demographics.

With regard to measures of stress, the mean PSS was 16.4, with a standard deviation of 6.2, suggesting that employees have moderate levels of stress at these locations. This result was consistent with the HWQ question regarding “overall stress felt this week”, with a mean score of 4.7 (SD 2.5; 10 is “very stressed”). Regarding measures of productivity, the mean overall HWQ was 6.3 (SD 0.7). With the exception of reverse items, as noted below, scores of 10 indicated high levels of productivity. Mean scores by scale were: 7.3 (SD 1.0) for overall productivity, with 7.5 (SD 1.3) for own assessment, and 7.5 (SD 1.2) for perceived other’s assessment; 7.1 (SD 2.7) supervisor relations, 7.8 (SD 1.8) for non-work satisfaction, and 7.3 (SD 1.7) for work satisfaction. The mean scale for the reverse items scores were concentration/focus at 3.4 (SD 2.0), and impatience/irritability 3.2 (SD 1.6).

Correlations between the PSS and the HWQ subscales ranged from −0.61 to 0.55 ( Table 2 ). A negative association was observed between the PSS and the overall HWQ, r(177) = − 0.35, p < 0.001. While each of the positively-coded HWQ subscales was associated negatively with the PSS, the strongest correlation occurred between work satisfaction and PSS, r(177) = −0.61, p < 0.001, suggesting that as stress increases work satisfaction declines.

Measures of correlation within and between the PSS and HWQ.

HWQ: Health and Work Questionnaire mean score; PSS: Perceived Stress Scale mean score

In evaluating differences by sex, mean scores were significantly higher for males compared with females for the HWQ Supervisor Relations subscale (8.4 (SD 2.1) versus 6.9 (SD 2.7), respectively; p < 0.005; Table 3 ). No other sex differences were observed for either instrument. Similarly, there were no significant differences by race.

Comparing results of the PSS and the HWQ by sex.

Findings suggested there is an inverse association between overall stress and productivity; higher PSS scores were associated with lower HWQ scores. These findings are consistent with other cross-sectional studies comparing productivity and other measures of psychological well-being. 1 , 8 , 9 , 10 Thus, employer efforts to decrease stress in the workplace may benefit employee productivity levels.

In addition, males scored higher for supervisor relations in the HWQ than females. This finding may suggest that males have stronger relationships with their supervisors. Indeed, there is compelling evidence to suggest the main factor affecting job satisfaction and performance is the relationship between supervisors and employees. 13 Although, this relationship may be mitigated by employee-supervisor interactions of sex, race/ethnicity, status, education, age, support systems, and other factors, none of which were evaluated in the current study.

For example, Rivera-Torres et al. 14 suggested that women with support systems, defined as co-workers and supervisors, experienced less work stress than males. Results from this study seemed to support Rivera-Torres et al. 14 in that females tended to report higher levels of stress compared with males (although not significant) and reported weaker relationships with their supervisors. In addition, Peterson 15 evaluated what employee’s value at work and found that males and females differed significantly. When asked to rank work values, men valued pay/money/benefits along with results/achievement/success most, whereas women valued friends/relationships along with recognition/respect. Perhaps, more research is necessary to understand the nuances between co-worker and supervisor regarding work satisfaction and productivity.

The study contributes to the literature in the use of different metrics for psychological well-being, defined as stress. Multiple organizations within Kansas were evaluated for both productivity and stress. To our knowledge, the PSS and HWQ have never been used together to measure the relationship between stress and productivity. Results suggested that overall productivity (HWQ) was associated with the HWQ “work satisfaction” subscale. Perceived stress also had the strongest inverse relationship with HWQ sub-scale “work satisfaction” when compared with HWQ sub-scale “productivity”.

This study suggested that productivity, stress, and job satisfaction were correlated, therefore, additional research needs to include each of these variables in greater detail as the current literature has been mixed on their relationships and potential collinearity. For example, one study examining two occupations suggested psychological well-being (defined as psychological functioning) was associated with productivity, whereas job satisfaction did not. 7 In contrast, another study suggested that psychological well-being has been a bigger factor in job productivity than work satisfaction alone, but both are associated with job productivity. 9 This current study was able to examine this relationship by using the PSS and the HWQ together.

More research is needed to understand these differences by standardizing terminology. In this study, psychological well-being was defined as stress. However, other studies have defined psychological well-being as happiness or as one’s psychological functioning. 7 , 8 This study also expanded the relationship between psychological well-being and stress. Previous research focused more on the relationship between productivity and burnout or job satisfaction.

This study had limitations such as a small sample size (in number of organizations and number of employees). The sample size assessed small organizations in the United States, whereas many other large scale studies on stress occurred over multiple large organizations in other countries. 1 , 10 There was limited racial diversity in the current study, as 6.1% (10 of 165) reported being non-white. The population studied was also primarily female, limiting the strength of comparisons made between sexes. Furthermore, because worksites often share computers, questionnaires may have been completed using the same IP address; thus, we were unable to prevent multiple entries from the same individual.

The current study did not detect a difference in productivity or stress by race. This differed from other research. For instance, non-whites experience greater overall stress than whites potentially attributable to poorer employment status, income, and education. 16 Non-whites experience stress secondary to racial discrimination. 17 , 18 In one study, when examining productivity among university faculty, non-whites reported greater stress and produced less research (productivity) compared to whites. 16 Further research needs to be conducted on productivity and stress by race and ethnicity, and associated variables, such as employment status, income, education, and occupation, need to be accounted for in analysis. Differences between other research and the current study regarding race may be attributed to the fact that only 6% of respondents who answered race reported being non-white, making racial diversity in this study limited, although representative of the population sampled.

CONCLUSIONS

This study suggested there is a negative correlation between overall stress and productivity: higher stress scores were significantly associated with lower productivity scores. This negative association was observed for all HWQ subscales, but was especially strong for work satisfaction. This study also suggested that males may have better supervisor relations compared to females, although no differences between sexes were observed by perceived levels of stress. There was no difference in productivity or stress by race. The results of this study suggested that employer efforts to decrease employee stress in the workplace may increase employee productivity.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

How to Recover from Work Stress, According to Science

- Alyson Meister,

- Bonnie Hayden Cheng,

- Franciska Krings

Five research-backed strategies that actually work.

To combat stress and burnout, employers are increasingly offering benefits like virtual mental health support, spontaneous days or even weeks off, meeting-free days, and flexible work scheduling. Despite these efforts and the increasing number of employees buying into the importance of wellness, the effort is lost if you don’t actually recover. So, if you feel like you’re burning out, what works when it comes to recovering from stress? The authors discuss the “recovery paradox” — that when our bodies and minds need to recover and reset the most, we’re the least likely and able to do something about it — and present five research-backed strategies for recovering from stress at work.

The workforce is tired. While sustainable job performance requires us to thrive at work, only 32% of employees across the globe say they’re thriving. With 43% reporting high levels of daily stress, it’s no surprise that a wealth of employees feel like they’re on the edge of burnout, with some reports suggesting that up to 61% of U.S. professionals feel like they’re burning out at any moment in time. Those who feel tense or stressed out during the workday are more than three times as likely to seek employment elsewhere.

- Alyson Meister is a professor of leadership and organizational behavior at IMD Business School in Lausanne, Switzerland. Specializing in the development of globally oriented, adaptive, and inclusive organizations, she has worked with thousands of executives, teams, and organizations from professional services to industrial goods and technology. Her research has been widely published, and in 2021, she was recognized as a Thinkers50 Radar thought leader.

- Bonnie Hayden Cheng is an associate professor of management and strategy and the MBA program director at HKU Business School, University of Hong Kong. She is the chief resilience officer of Human at Work and serves as a scientific advisor of OneMind at Work. She works with senior executives of companies ranging from startups to Fortune 500, transforming corporate cultures by incorporating wellness into their business strategy. Follow her on Twitter: @drbcheng.

- ND Nele Dael is a senior behavioral scientist studying emotion, personality, and social skills in organizational contexts. She is leading research projects on workplace well-being at IMD Lausanne, focusing on stress and recovery. Nele is particularly tuned into new technologies for the benefit of research and application in human interaction, and her work has been published in several leading journals.

- FK Franciska Krings is professor of organizational behavior at HEC Lausanne, University of Lausanne. Her research interests include workforce diversity and discrimination, work-family balance, impression management, and (non)ethical behaviors. Her work has been published regularly in leading journals in the field.

Partner Center

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Work stress, mental health, and employee performance.

- 1 School of Business, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China

- 2 Henan Research Platform Service Center, Zhengzhou, China

The COVID-19 pandemic outbreak—as a typical emergency event—significantly has impacted employees' psychological status and thus has negatively affected their performance. Hence, along with focusing on the mechanisms and solutions to alleviate the impact of work stress on employee performance, we also examine the relationship between work stress, mental health, and employee performance. Furthermore, we analyzed the moderating role of servant leadership in the relationship between work stress and mental health, but the result was not significant. The results contribute to providing practical guidance for enterprises to improve employee performance in the context of major emergencies.

Introduction

Small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are the key drivers of economic development as they contribute >50, 60, 70, 80, and 90% of tax revenue, GDP, technological innovation, labor employment, and the number of enterprises, respectively. However, owing to the disadvantages of small-scale and insufficient resources ( Cai et al., 2017 ; Flynn, 2017 ), these enterprises are more vulnerable to being influenced by emergency events. The COVID-19 pandemic outbreak—as a typical emergency event—has negatively affected survival and growth of SMEs ( Eggers, 2020 ). Some SMEs have faced a relatively higher risk of salary reduction, layoffs, or corporate bankruptcy ( Adam and Alarifi, 2021 ). Consequently, it has made employees in the SMEs face the following stressors during the COVID-19 pandemic: First, employees' income, promotion, and career development opportunities have declined ( Shimazu et al., 2020 ). Second, as most employees had to work from home, family conflicts have increased and family satisfaction has decreased ( Green et al., 2020 ; Xu et al., 2020 ). Finally, as work tasks and positions have changed, the new work environment has made employees less engaged and less fulfilled at work ( Olugbade and Karatepe, 2019 ; Chen and Fellenz, 2020 ).

For SMEs, employees are their core assets and are crucial to their survival and growth ( Shan et al., 2022 ). Employee work stress may precipitate burnout ( Choi et al., 2019 ; Barello et al., 2020 ), which manifests as fatigue and frustration ( Mansour and Tremblay, 2018 ), and is associated with various negative reactions, including job dissatisfaction, low organizational commitment, and a high propensity to resign ( Lu and Gursoy, 2016 ; Uchmanowicz et al., 2020 ). Ultimately, it negatively impacts employee performance ( Prasad and Vaidya, 2020 ). The problem of employee work stress has become an important topic for researchers and practitioners alike. In this regard, it is timely to explore the impact of work stress on SME problems of survival and growth during emergency events like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although recent studies have demonstrated the relationship between work stress and employee performance, some insufficiencies persist, which must be resolved. Research on how work stress affects employee performance has remained fragmented and limited. First, the research into how work stress affects employee performance is still insufficient. Some researchers have explored the effects of work stress on employee performance during COVID-19 ( Saleem et al., 2021 ; Tu et al., 2021 ). However, they have not explained the intermediate path, which limits our understanding of effects of work stress. As work stress causes psychological pain to employees, in response, they exhibit lower performance levels ( Song et al., 2020 ; Yu et al., 2022 ). Thus, employees' mental health becomes an important path to explain the relationship mechanism between work stress and employee performance, which is revealed in this study using a stress–psychological state–performance framework. Second, resolving the mental health problems caused by work stress has become a key issue for SMEs during the COVID-19 pandemic. As the core of the enterprise ( Ahn et al., 2018 ), the behavior of leaders significantly influences employees. Especially for SMEs, intensive interactive communication transpires between the leader and employees ( Li et al., 2019 ; Tiedtke et al., 2020 ). Servant leadership, as a typical leader's behavior, is considered an important determinant of employee mental health ( Haslam et al., 2020 ). Hence, to improve employees' mental health, we introduce servant leadership as a moderating variable and explore its contingency effect on relieving work stress and mental health.

This study predominantly tries to answer the question of how work stress influences employee performance and explores the mediating impact of mental health and the moderating impact of servant leadership in this relationship. Mainly, this study contributes to the existing literature in the following three ways: First, this research analyzes the influence of work stress on employee performance in SMEs during the COVID-19 pandemic, which complements previous studies and theories related to work stress. Second, this study regards mental health as a psychological state and examines its mediating impact on the relationship between work stress and employee performance, which complements the research path on how work stress affects employee performance. Third, we explore the moderating impact of servant leadership, which has been ignored in previous research, thus extending the understanding of the relationship between the work stress and mental health of employees in SMEs.

To accomplish the aforementioned tasks, the remainder of this article is structured as follows: First, based on the literature review, we propose our hypotheses. Thereafter, we present our research method, including the processes of data collection, sample characteristics, measurement of variables, and sample validity. Subsequently, we provide the data analysis and report the results. Finally, we discuss the results and present the study limitations.

Theoretical background and hypotheses

Work stress and employee performance.

From a psychological perspective, work stress influences employees' psychological states, which, in turn, affects their effort levels at work ( Lu, 1997 ; Richardson and Rothstein, 2008 ; Lai et al., 2022 ). Employee performance is the result of the individual's efforts at work ( Robbins, 2005 ) and thus is significantly impacted by work stress. However, previous research has provided no consistent conclusion regarding the relationship between work stress and employee performance. One view is that a significant positive relationship exists between work stress and employee performance ( Ismail et al., 2015 ; Soomro et al., 2019 ), suggesting that stress is a motivational force that encourages employees to work hard and improve work efficiency. Another view is that work stress negatively impacts employee performance ( Yunus et al., 2018 ; Nawaz Kalyar et al., 2019 ; Purnomo et al., 2021 ), suggesting that employees need to spend time and energy to cope with stress, which increases their burden and decreases their work efficiency. A third view is that the impact of work stress on employee performance is non-linear and may exhibit an inverted U-shaped relationship ( McClenahan et al., 2007 ; Hamidi and Eivazi, 2010 ); reportedly, when work stress is relatively low or high, employee performance is low. Hence, if work stress reaches a moderate level, employee performance will peak. However, this conclusion is derived from theoretical analyses and is not supported by empirical data. Finally, another view suggests that no relationship exists between them ( Tănăsescu and Ramona-Diana, 2019 ). Indubitably, it presupposes that employees are rational beings ( Lebesby and Benders, 2020 ). Per this view, work stress cannot motivate employees or influence their psychology and thus cannot impact their performance.

To further explain the aforementioned diverse views, positive psychology proposes that work stress includes two main categories: challenge stress and hindrance stress ( Cavanaugh et al., 2000 ; LePine et al., 2005 ). Based on their views, challenge stress represents stress that positively affects employees' work attitudes and behaviors, which improves employee performance by increasing work responsibility; by contrast, hindrance stress negatively affects employees' work attitudes and behaviors, which reduces employee performance by increasing role ambiguity ( Hon and Chan, 2013 ; Deng et al., 2019 ).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, SMEs have faced a relatively higher risk of salary reductions, layoffs, or corporate bankruptcy ( Adam and Alarifi, 2021 ). Hence, the competition among enterprises has intensified; managers may transfer some stress to employees, who, in turn, need to bear this to maintain and seek current and future career prospects, respectively ( Lai et al., 2015 ). In this context, employee work stress stems from increased survival problems of SMEs, and such an external shock precipitates greater stress among employees than ever before ( Gao, 2021 ). Stress more frequently manifests as hindrance stress ( LePine et al., 2004 ), which negatively affects employees' wellbeing and quality of life ( Orfei et al., 2022 ). It imposes a burden on employees, who need to spend time and energy coping with the stress. From the perspective of stressors, SMEs have faced serious survival problems during the COVID-19 pandemic, and consequently, employees have faced greater hindrance stress, thereby decreasing their performance. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1 . Work stress negatively influences employee performance in SMEs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Work stress and mental health

According to the demand–control–support (DCS) model ( Karasek and Theorell, 1990 ), high-stress work—such as high job demands, low job control, and low social support at work—may trigger health problems in employees over time (e.g., mental health problems; Chou et al., 2015 ; Park et al., 2016 ; Lu et al., 2020 ). The DCS model considers stress as an individual's response to perceiving high-intensity work ( Houtman et al., 2007 ), which precipitates a change in the employee's cognitive, physical, mental, and emotional status. Of these, mental health problems including irritability, nervousness, aggressive behavior, inattention, sleep, and memory disturbances are a typical response to work stress ( Mayerl et al., 2016 ; Neupane and Nygard, 2017 ). If the response persists for a considerable period, mental health problems such as anxiety or depression may occur ( Bhui et al., 2012 ; Eskilsson et al., 2017 ). As coping with work stress requires an employee to exert continuous effort and apply relevant skills, it may be closely related to certain psychological problems ( Poms et al., 2016 ; Harrison and Stephens, 2019 ).

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the normal operating order of enterprises as well as employees' work rhythm. Consequently, employees might have faced greater challenges during this period ( Piccarozzi et al., 2021 ). In this context, work stress includes stress related to health and safety risk, impaired performance, work adjustment, and negative emotions, for instance, such work stress can lead to unhealthy mental problems. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2 . Work stress negatively influences mental health in SMEs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mediating role of mental health

Previous research has found that employees' mental health status significantly affects their performance ( Bubonya et al., 2017 ; Cohen et al., 2019 ; Soeker et al., 2019 ), the main reasons of which are as follows: First, mental health problems reduce employees' focus on their work, which is potentially detrimental to their performance ( Hennekam et al., 2020 ). Second, mental health problems may render employees unable to work ( Heffernan and Pilkington, 2011 ), which indirectly reduces work efficiency owing to increased sick leaves ( Levinson et al., 2010 ). Finally, in the stress context, employees need to exert additional effort to adapt to the environment, which, consequently, make them feel emotionally exhausted. Hence, as their demands remain unfulfilled, their work satisfaction and performance decrease ( Khamisa et al., 2016 ).

Hence, we propose that work stress negatively impacts mental health, which, in turn, positively affects employee performance. In other words, we argue that mental health mediates the relationship between work stress and employee performance. During the COVID-19 pandemic, work stress—owing to changes in the external environment—might have caused nervous and anxious psychological states in employees ( Tan et al., 2020 ). Consequently, it might have rendered employees unable to devote their full attention to their work, and hence, their work performance might have decreased. Meanwhile, due to the pandemic, employees have faced the challenges of unclear job prospects and reduced income. Therefore, mental health problems manifest as moods characterized by depression and worry ( Karatepe et al., 2020 ). Negative emotions negatively impact employee performance. Per the aforementioned arguments and hypothesis 2, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3 . Mental health mediates the relationship between work stress and employee performance in SMEs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Moderating role of servant leadership

According to the upper echelons theory, leaders significantly influence organizational activities, and their leadership behavior influences the thinking and understanding of tasks among employees in enterprises ( Hambrick and Mason, 1984 ). Servant leadership is a typical leadership behavior that refers to leaders exhibiting humility, lending power to employees, raising the moral level of subordinates, and placing the interests of employees above their own ( Sendjaya, 2015 ; Eva et al., 2019 ). This leadership behavior provides emotional support to employees and increase their personal confidence and self-esteem and thus reduce negative effects of work stress. In our study, we propose that servant leadership reduces the negative effects of work stress on mental health in SMEs.

Servant leadership can reduce negative effects of work stress on mental health in the following ways: Servant leaders exhibit empathy and compassion ( Lu et al., 2019 ), which help alleviate employees' emotional pain caused by work stress. Song et al. (2020) highlighted that work stress can cause psychological pain among employees. However, servant leaders are willing to listen to their employees and become acquainted with them, which facilitates communication between the leader and the employee ( Spears, 2010 ). Hence, servant leadership may reduce employees' psychological pain through effective communication. Finally, servant leaders lend employees power, which makes the employees feel trusted. Employees—owing to their trust in the leaders—trust the enterprises as well, which reduces the insecurity caused by work stress ( Phong et al., 2018 ). In conclusion, servant leadership serves as a coping resource that reduces the impact of losing social support and thus curbs negative employee emotions ( Ahmed et al., 2021 ). Based on the aforementioned analysis, we find that servant leaders can reduce the mental health problems caused by work stress. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4 . Servant leadership reduces the negative relationship between work stress and mental health in SMEs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methodology

Data collection and samples.

To assess our theoretical hypotheses, we collected data by administering a questionnaire survey. The questionnaire was administered anonymously, and the respondents were informed regarding the purpose of the study. Owing to the impact of the pandemic, we distributed and collected the questionnaires by email. Specifically, we utilized the network relationships of our research group with the corporate campus and group members to distribute the questionnaires. In addition, to ensure the quality of the questionnaires, typically senior employees who had worked for at least 2 years at their enterprises were chosen as the respondents.

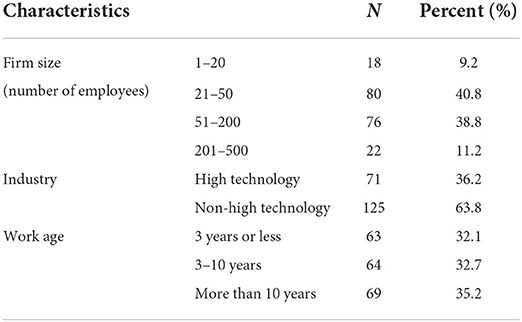

Before the formal survey, we conducted a pilot test. Thereafter, we revised the questionnaire based on the results of the trial investigation. Subsequently, we randomly administered the questionnaires to the target enterprises. Hence, 450 questionnaires were administered via email, and 196 valid questionnaires were returned—an effective rate of 43.6%. Table 1 presents the profiles of the samples.

Table 1 . Profiles of the samples.

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the sample. Based on the firm size, respondents who worked in a company with 1–20 employees accounted for 9.2%, those in a company with 21–50 employees accounted for 40.8%, those in a company with 51–200 employees accounted for 38.8%, and those in a company with 201–500 employees accounted for 11.2%. Regarding industry, the majority of the respondents (63.8%) worked for non-high-technology industry and 36.2% of the respondents worked for high-technology industry. Regarding work age, the participants with a work experience of 3 years or less accounted for 32.1%, those with work experience of 3–10 years accounted for 32.7%, and those with a work experience of more than 10 years accounted for 35.2%.

Core variables in this study include English-version measures that have been well tested in prior studies; some modifications were implemented during the translation process. As the objective of our study is SMEs in China, we translated the English version to Chinese; this translation was carried out by two professionals to ensure accuracy. Thereafter, we administered the questionnaires to the respondents. Hence, as the measures of our variables were revised based on the trial investigation, we asked two professionals to translate the Chinese version of the responses to English to enable publishing this work in English. We evaluated all the items pertaining to the main variables using a seven-point Likert scale (7 = very high/strongly agree, 1 = very low/strongly disagree). The variable measures are presented subsequently.

Work stress (WS)

Following the studies of Parker and DeCotiis (1983) and Shah et al. (2021) , we used 12 items to measure work stress, such as “I get irritated or nervous because of work” and “Work takes a lot of my energy, but the reward is less than the effort.”

Mental health (MH)

The GHQ-12 is a widely used tool developed to assess the mental health status ( Liu et al., 2022 ). However, we revised the questionnaire by combining the research needs and results of the pilot test. We used seven items to measure mental health, such as “I feel that I am unable (or completely unable) to overcome difficulties in my work or life.” In the final calculation, the scoring questions for mental health were converted; higher scores indicated higher levels of mental health.

Servant leadership (SL)

Following the studies by Ehrhart (2004) and Sendjaya et al. (2019) , we used nine items to measure servant leadership, including “My leader makes time to build good relationships with employees” and “My leader is willing to listen to subordinates during decision-making.”

Employee performance (EP)

We draw on the measurement method provided by Chen et al. (2002) and Khorakian and Sharifirad (2019) ; we used four items to represent employee performance. An example item is as follows: “I can make a contribution to the overall performance of our enterprise.”

Control variables

We controlled several variables that may influence employee performance, including firm size, industry, and work age. Firm size was measured by the number of employees. For industry, we coded them into two dummy variables (high-technology industry = 1, non-high-technology industry = 0). We calculated work experience by the number of years the employee has worked for the enterprise.

Common method bias

Common method bias may exist because each questionnaire was completed independently by each respondent ( Cai et al., 2017 ). We conducted a Harman one-factor test to examine whether common method bias significantly affected our data ( Podsakoff and Organ, 1986 ); the results revealed that the largest factor in our data accounted for only 36.219% of the entire variance. Hence, common method bias did not significantly affect on our study findings.

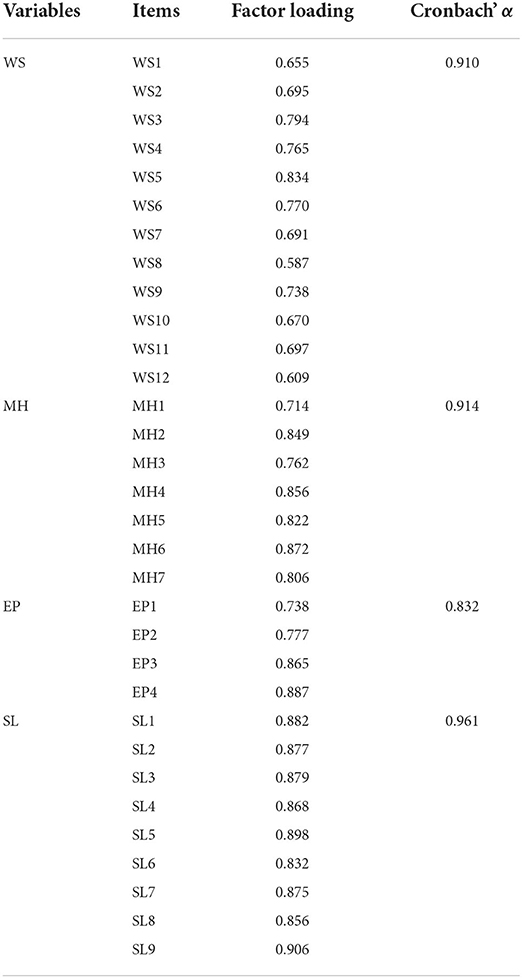

Reliability and validity

We analyzed the reliability and validity of our data for further data processing, the results of which are presented in Table 2 . Based on these results, we found that Cronbach's alpha coefficient of each variable was >0.8, thus meeting the requirements for reliability of the variables. To assess the validity of each construct, we conducted four separate confirmatory factor analyses. All the factor loadings exceeded 0.5. Overall, the reliability and validity results met the requirements for further data processing.

Table 2 . Results of confirmatory factor analysis and Cronbach's alpha coefficients.

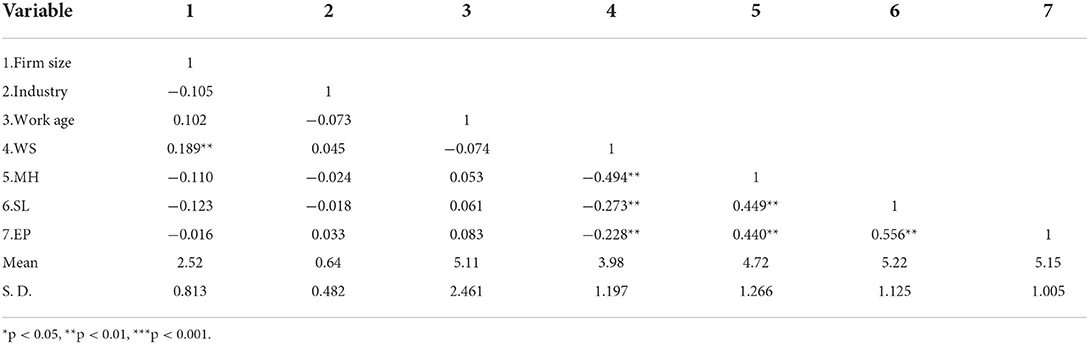

To verify our hypotheses, we used a hierarchical linear regression method. Before conducting the regression analysis, we performed a Pearson correlation analysis, the results of which are presented in Table 3 .

Table 3 . Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis.

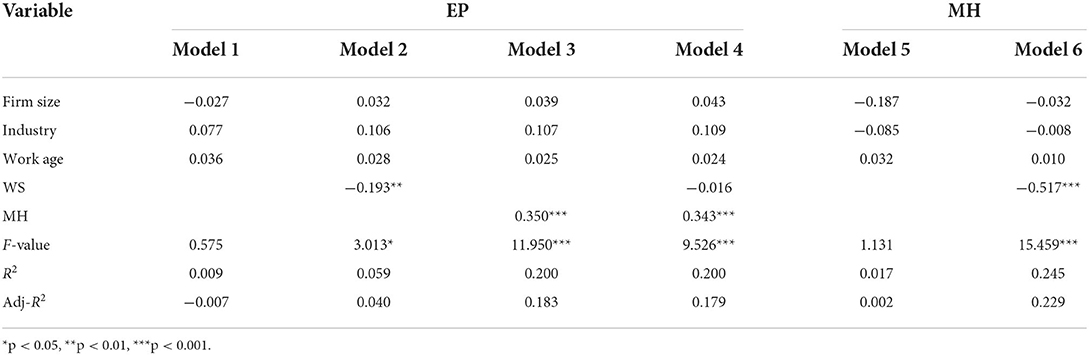

In the regression analysis, we calculated the variance inflation factor (VIF) of each variable and found that the VIF value of each variable was <3. Hence, the effect of multiple co-linearity is not significant. The results of regression analysis are presented in Tables 4 , 5 .

Table 4 . Results of linear regression analysis (models 1–6).

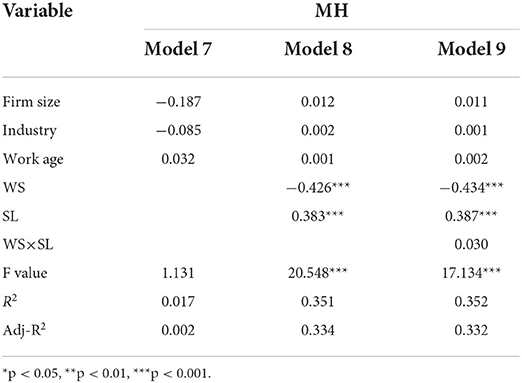

Table 5 . Results of linear regression analysis (models 7–9).

Table 4 shows that model 1 is the basic model assessing the effects of control variables on employee performance. In model 2, we added an independent variable (work stress) to examine its effect on employee performance. The results revealed that work stress negatively affects employee performance (β = −0.193, p < 0.01). Therefore, hypothesis 1 is supported. Model 5 is the basic model that examines the effects of control variables on mental health. In model 6, we added an independent variable (work stress) to assess its effect on mental health. We found that work stress negatively affects mental health (β = −0.517, p < 0.001). Therefore, hypothesis 2 is supported.

To verify the mediating effect of mental health on the relationship between work stress and employee performance, we used the method introduced by Kenny et al. (1998) , which is described as follows: (1) The independent variable is significantly related to the dependent variable. (2) The independent variable is significantly related to the mediating variable. (3) The mediating variable is significantly related to the dependent variable after controlling for the independent variable. (4) If the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable becomes smaller, it indicates a partial mediating effect. (5) If the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable is no longer significant, it indicates a full mediating effect. Based on this method, in model 4, mental health is significantly positively related to employee performance (β = 0.343, p < 0.001), and no significant correlation exists between work stress and employee performance (β = −0.016, p > 0.05). Hence, mental health fully mediates the relationship between work stress and employee performance. Therefore, hypothesis 3 is supported.

To verify the moderating effect of servant leadership on the relationship between work stress and mental health, we gradually added independent variables, a moderator variable, and interaction between the independent variables and moderator variable to the analysis, the results of which are presented in Table 5 . In model 9, the moderating effect of servant leadership is not supported (β = 0.030, p > 0.05). Therefore, hypothesis 4 is not supported.

For SMEs, employees are core assets and crucial to their survival and growth ( Shan et al., 2022 ). Specifically, owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, employees' work stress may precipitate burnout ( Choi et al., 2019 ; Barello et al., 2020 ), which influences their performance. Researchers and practitioners have significantly focused on resolving the challenge of work stress ( Karatepe et al., 2020 ; Tan et al., 2020 ; Gao, 2021 ). However, previous research has not clearly elucidated the relationship among work stress, mental health, servant leadership, and employee performance. Through this study, we found the following results:

Employees in SMEs face work stress owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, which reduces their performance. Facing these external shocks, survival and growth of SMEs may become increasingly uncertain ( Adam and Alarifi, 2021 ). Employees' career prospects are negatively impacted. Meanwhile, the pandemic has precipitated a change in the way employees work, their workspace, and work timings. Moreover, their work is now intertwined with family life. Hence, employees experience greater stress at work than ever before ( Gao, 2021 ), which, in turn, affects their productivity and deteriorates their performance.

Furthermore, we found that mental health plays a mediating role in the relationship between work stress and employee performance; this suggests that employees' mental status is influenced by work stress, which, in turn, lowers job performance. Per our findings, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, employees experience nervous and anxious psychological states ( Tan et al., 2020 ), which renders them unable to devote their full attention to their work; hence, their work performance is likely to decrease.

Finally, we found that leaders are the core of any enterprise ( Ahn et al., 2018 ). Hence, their leadership behavior significantly influences employees. Per previous research, servant leadership is considered a typical leadership behavior characterized by exhibiting humility, delegating power to employees, raising the morale of subordinates, and placing the interests of employees above their own ( Sendjaya, 2015 ; Eva et al., 2019 ). Through theoretical analysis, we found that servant leadership mitigates the negative effect of work stress on mental health. However, the empirical results are not significant possibly because work stress of employees in SMEs is rooted in worries regarding the future of the macroeconomic environment, and the resulting mental health problems cannot be cured merely by a leader.

Hence, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, employees experience work stress, which precipitates mental health problems and poor employee performance. To solve the problem of work stress, SMEs should pay more attention to fostering servant leadership. Meanwhile, organizational culture is also important in alleviating employees' mental health problems and thus reducing negative effects of work stress on employee performance.

Implications

This study findings have several theoretical and managerial implications.

Theoretical implications

First, per previous research, no consistent conclusion exists regarding the relationship between work stress and employee performance, including positive relationships ( Ismail et al., 2015 ; Soomro et al., 2019 ), negative relationships ( Yunus et al., 2018 ; Nawaz Kalyar et al., 2019 ; Purnomo et al., 2021 ), inverted U-shaped relationships ( McClenahan et al., 2007 ; Hamidi and Eivazi, 2010 ), and no relationship ( Tănăsescu and Ramona-Diana, 2019 ). We report that work stress negatively affects employee performance in SMEs during the COVID-19 pandemic; thus, this study contributes to the understanding of the situational nature of work stress and provides enriching insights pertaining to positive psychology.

Second, we established the research path that work stress affects employee performance. Mental health is a psychological state that may influence an individual's work efficiency. In this study, we explored its mediating role, which opens the black box of the relationship between work stress and employee performance; thus, this study contributes to a greater understanding of the role of work stress during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Finally, this study sheds light on the moderating effect of servant leadership, which is useful for understanding why some SMEs exhibit greater difficulty in achieving success than others during the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous research has explained the negative effect of work stress ( Yunus et al., 2018 ; Nawaz Kalyar et al., 2019 ; Purnomo et al., 2021 ). However, few studies have focused on how to resolve the problem. We identify servant leadership as the moderating factor providing theoretical support for solving the problem of work stress. This study expands the explanatory scope of the upper echelons theory.

Practice implications

First, this study elucidates the sources and mechanisms of work stress in SMEs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Employees should continuously acquire new skills to improve themselves and thus reduce their replaceability. Meanwhile, they should enhance their time management and emotional regulation skills to prevent the emergence of adverse psychological problems.

Second, leaders in SMEs should pay more attention to employees' mental health to prevent the emergence of hindrance stress. Employees are primarily exposed to stress from health and safety risks, impaired performance, and negative emotions. Hence, leaders should communicate with employees in a timely manner to understand their true needs, which can help avoid mental health problems due to work stress among employees.

Third, policymakers should realize that a key cause of employee work stress in SMEs is attributable to concerns regarding the macroeconomic environment. Hence, they should formulate reasonable support policies to improve the confidence of the whole society in SMEs, which helps mitigate SME employees' work stress during emergency events like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Finally, as work stress causes mental health problems, SME owners should focus on their employees' physical as well as mental health. Society should establish a psychological construction platform for SME employees to help them address their psychological problems.

Limitations and future research

This study has limitations, which should be addressed by further research. First, differences exist in the impact of the pandemic on different industries. Future research should focus on the impact of work stress on employee performance in different industries. Second, this study only explored the moderating role of servant leadership. Other leadership behaviors of leaders may also affect work stress. Future research can use case study methods to explore the role of other leadership behaviors.

This study explored the relationship between work stress and employee performance in SMEs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Using a sample of 196 SMEs from China, we found that as a typical result of emergency events, work stress negatively affects employees' performance, particularly by affecting employees' mental health. Furthermore, we found that servant leadership provides a friendly internal environment to mitigate negative effects of work stress on employees working in SMEs.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the patients/participants or patients/participants legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

BC: conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft, and visualization. LW: formal analysis. BL: investigation, funding acquisition, and writing—review and editing. WL: resources, project administration, and supervision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research was supported by the major project of Henan Province Key R&D and Promotion Special Project (Soft Science) Current Situation, Realization Path and Guarantee Measures for Digital Transformation Development of SMEs in Henan Province under the New Development Pattern (Grant No. 222400410159).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Adam, N. A., and Alarifi, G. (2021). Innovation practices for survival of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in the COVID-19 times: the role of external support. J. Innov. Entrepreneursh . 10, 1–22. doi: 10.1186/s13731-021-00156-6

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ahmed, I., Ali, M., Usman, M., Syed, K. H., and Rashid, H. A. (2021). Customer Mistreatment and Insomnia in Employees-a Study in Context of COVID-19. J. Behav. Sci. 31, 248–271.

Google Scholar

Ahn, J., Lee, S., and Yun, S. (2018). Leaders' core self-evaluation, ethical leadership, and employees' job performance: the moderating role of employees' exchange ideology. J. Bus. Ethics . 148, 457–470. doi: 10.1007/s10551-016-3030-0

Barello, S., Palamenghi, L., and Graffigna, G. (2020). Burnout and somatic symptoms among frontline healthcare professionals at the peak of the Italian COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res . 290, 113129. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113129

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bhui, K. S., Dinos, S., Stansfeld, S. A., and White, P. D. (2012). A synthesis of the evidence for managing stress at work: a review of the reviews reporting on anxiety, depression, and absenteeism. J. Environ. Public Health . 2012. doi: 10.1155/2012/515874

Bubonya, M., Cobb-Clark, D. A., and Wooden, M. (2017). Mental health and productivity at work: Does what you do matter?. Labour Econ . 46, 150–165. doi: 10.1016/j.labeco.2017.05.001

Cai, L., Chen, B., Chen, J., and Bruton, G. D. (2017). Dysfunctional competition and innovation strategy of new ventures as they mature. J. Bus. Res . 78, 111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.05.008

Cavanaugh, M. A., Boswell, W. R., Roehling, M. V., and Boudreau, J. W. (2000). An empirical examination of self-reported work stress among US managers. J. Appl. Psychol . 85, 65–74. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.85.1.65

Chen, I. S., and Fellenz, M. R. (2020). Personal resources and personal demands for work engagement: Evidence from employees in the service industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manage . 90, 102600. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102600

Chen, Z. X., Tsui, A. S., and Farh, J. L. (2002). Loyalty to supervisor vs. organizational commitment: Relationships to employee performance in China. J. Occupa. Organ. Psychol . 75, 339–356. doi: 10.1348/096317902320369749

Choi, H. M., Mohammad, A. A., and Kim, W. G. (2019). Understanding hotel frontline employees' emotional intelligence, emotional labor, job stress, coping strategies and burnout. Int. J. Hosp. Manage . 82, 199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.05.002

Chou, L., Hu, S., and Lo, M. (2015). Job stress, mental health, burnout and arterial stiffness: a cross-sectional study among Taiwanese medical professionals. Atherosclerosis . 241, e135–e135. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.04.468

Cohen, J., Schiffler, F., Rohmer, O., Louvet, E., and Mollaret, P. (2019). Is disability really an obstacle to success? Impact of a disability simulation on motivation and performance. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol . 49, 50–59. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12564

Deng, J., Guo, Y., Ma, T., Yang, T., and Tian, X. (2019). How job stress influences job performance among Chinese healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study. Environ. Health Prevent. Med . 24, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12199-018-0758-4

Eggers, F. (2020). Masters of disasters? Challenges and opportunities for SMEs in times of crisis. J. Bus. Res . 116, 199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.025

Ehrhart, M. G. (2004). Leadership and procedural justice climate as antecedents of unit-level organizational citizenship behavior. Pers. Psychol . 57, 61–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2004.tb02484.x

Eskilsson, T., Slunga Järvholm, L., Malmberg Gavelin, H., Stigsdotter Neely, A., and Boraxbekk, C. J. (2017). Aerobic training for improved memory in patients with stress-related exhaustion: a randomized controlled trial. BMC psychiatry . 17, 1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1457-1

Eva, N., Robin, M., Sendjaya, S., Van Dierendonck, D., and Liden, R. C. (2019). Servant leadership: a systematic review and call for future research. Leadersh. Q . 30, 111–132. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.07.004

Flynn, A. (2017). Re-thinking SME disadvantage in public procurement. J. Small Bus. Enter. Dev . 24, 991–1008. doi: 10.1108/JSBED-03-2017-0114

Gao, Y. (2021). Challenges and countermeasures of human resource manage in the post-epidemic Period. Int. J. Manage Educ. Human Dev . 1, 036–040.

Green, N., Tappin, D., and Bentley, T. (2020). Working from home before, during and after the Covid-19 pandemic: implications for workers and organisations. N. Z. J. Employ. Relat . 45, 5–16. doi: 10.24135/nzjer.v45i2.19

Hambrick, D. C., and Mason, P. A. (1984). Upper echelons: the organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad.Manage. Rev . 9, 193–206. doi: 10.2307/258434

Hamidi, Y., and Eivazi, Z. (2010). The relationships among employees' job stress, job satisfaction, and the organizational performance of Hamadan urban health centers. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J . 38, 963–968. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2010.38.7.963

Harrison, M. A., and Stephens, K. K. (2019). Shifting from wellness at work to wellness in work: Interrogating the link between stress and organization while theorizing a move toward wellness-in-practice. Manage. Commun. Q . 33, 616–649. doi: 10.1177/0893318919862490

Haslam, S. A., Reicher, S. D., and Platow, M. J. (2020). The New Psychology of Leadership: Identity, Influence and Power . London, UK: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781351108232

Heffernan, J., and Pilkington, P. (2011). Supported employment for persons with mental illness: systematic review of the effectiveness of individual placement and support in the UK. J. Mental Health . 20, 368–380. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2011.556159

Hennekam, S., Richard, S., and Grima, F. (2020). Coping with mental health conditions at work and its impact on self-perceived job performance. Employee Relat. Int. J . 42, 626–645. doi: 10.1108/ER-05-2019-0211

Hon, A. H., and Chan, W. W. (2013). The effects of group conflict and work stress on employee performance. Cornell Hosp. Q . 54, 174–184. doi: 10.1177/1938965513476367

Houtman, I., Jettinghof, K., and Cedillo, L. (2007). Raising Awareness of Stress at Work in Developing Countires: a Modern Hazard in a Traditional Working Environment: Advice to Employers and Worker Representatives . Geneva: World Health Organization.

Ismail, A., Saudin, N., Ismail, Y., Samah, A. J. A., Bakar, R. A., Aminudin, N. N., et al. (2015). Effect of workplace stress on job performance. Econ. Rev. J. Econ. Bus . 13, 45–57.

Karasek, R., and Theorell, T. (1990). Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity, and the Reconstruction of Working Life . New York: Basic Books.

Karatepe, O. M., Rezapouraghdam, H., and Hassannia, R. (2020). Job insecurity, work engagement and their effects on hotel employees' non-green and nonattendance behaviors. Int. J. Hosp. Manage . 87, 102472. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102472

Kenny, D., Kashy, D., and Bolger, N. (1998). Data analysis in social psychology. Handbook Soc. Psychol. 1, 233–268.

Khamisa, N., Peltzer, K., Ilic, D., and Oldenburg, B. (2016). Work related stress, burnout, job satisfaction and general health of nurses: a follow-up study. Int. J. Nurs. Pract . 22, 538–545. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12455

Khorakian, A., and Sharifirad, M. S. (2019). Integrating implicit leadership theories, leader–member exchange, self-efficacy, and attachment theory to predict job performance. Psychol. Rep . 122, 1117–1144. doi: 10.1177/0033294118773400

Lai, H., Hossin, M. A., Li, J., Wang, R., and Hosain, M. S. (2022). Examining the relationship between COVID-19 related job stress and employees' turnover intention with the moderating role of perceived organizational support: Evidence from SMEs in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health . 19, 3719. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19063719

Lai, Y., Saridakis, G., and Blackburn, R. (2015). Job stress in the United Kingdom: Are small and medium-sized enterprises and large enterprises different?. Stress Health . 31, 222–235. doi: 10.1002/smi.2549

Lebesby, K., and Benders, J. (2020). Too smart to participate? Rational reasons for employees' non-participation in action research. Syst. Pract. Action Res . 33, 625–638. doi: 10.1007/s11213-020-09538-5

LePine, J. A., LePine, M. A., and Jackson, C. L. (2004). Challenge and hindrance stress: relationships with exhaustion, motivation to learn, and learning performance. J. Appl. Psychol . 89, 883. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.89.5.883

LePine, J. A., Podsakoff, N. P., and LePine, M. A. (2005). A meta-analytic test of the challenge stressor–hindrance stressor framework: an explanation for inconsistent relationships among stressors and performance. Acad. Manage J . 48, 764–775. doi: 10.5465/amj.2005.18803921

Levinson, D., Lakoma, M. D., Petukhova, M., Schoenbaum, M., Zaslavsky, A. M., Angermeyer, M., et al. (2010). Associations of serious mental illness with earnings: results from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Br. J. Psychiatry . 197, 114–121. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.073635

Li, S., Rees, C. J., and Branine, M. (2019). Employees' perceptions of human resource Manage practices and employee outcomes: empirical evidence from small and medium-sized enterprises in China. Employee Relat. Int. J . 41, 1419–1433. doi: 10.1108/ER-01-2019-0065

Liu, Z., Xi, C., Zhong, M., Peng, W., Liu, Q., Chu, J., et al. (2022). Factorial validity of the 12-item general health questionnaire in patients with psychological disorders. Current Psychol . 1–9. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-02845-1

Lu, A. C. C., and Gursoy, D. (2016). Impact of job burnout on satisfaction and turnover intention: do generational differences matter?. J. Hosp. Tour. Res . 40, 210–235. doi: 10.1177/1096348013495696

Lu, J., Zhang, Z., and Jia, M. (2019). Does servant leadership affect employees' emotional labor? A Soc. information-processing perspective. J. Bus. Ethics . 159, 507–518. doi: 10.1007/s10551-018-3816-3

Lu, L. (1997). Hassles, appraisals, coping and distress: a closer look at the stress process. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci . 13, 503–510.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Lu, Y., Zhang, Z., Yan, H., Rui, B., and Liu, J. (2020). Effects of occupational hazards on job stress and mental health of factory workers and miners: a propensity score analysis. BioMed Res. Int . 2020. doi: 10.1155/2020/1754897

Mansour, S., and Tremblay, D. G. (2018). Work–family conflict/family–work conflict, job stress, burnout and intention to leave in the hotel industry in Quebec (Canada): moderating role of need for family friendly practices as “resource passageways”. Int. J. Human Res. Manage . 29, 2399–2430. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2016.1239216

Mayerl, H., Stolz, E., Waxenegger, A., Rásky, É., and Freidl, W. (2016). The role of personal and job resources in the relationship between psychoSoc. job demands, mental strain, and health problems. Front. Psychol . 7, 1214. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01214

McClenahan, C., Shevlin, M. G., Bennett, C., and O'Neill, B. (2007). Testicular self-examination: a test of the health belief model and the theory of planned behaviour. Health Educ. Res . 22, 272–284. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl076

Nawaz Kalyar, M., Shafique, I., and Ahmad, B. (2019). Job stress and performance nexus in tourism industry: a moderation analysis. Tour. Int. Interdiscip. J . 67, 6–21.

Neupane, S., and Nygard, C. H. (2017). Physical and mental strain at work: relationships with onset and persistent of multi-site pain in a four-year follow up. Int. J. Indus. Ergon . 60, 47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ergon.2016.03.005

Olugbade, O. A., and Karatepe, O. M. (2019). Stressors, work engagement and their effects on hotel employee outcomes. Serv. Indus. J . 39, 279–298. doi: 10.1080/02642069.2018.1520842

Orfei, M. D., Porcari, D. E., D'Arcangelo, S., Maggi, F., Russignaga, D., Lattanzi, N., et al. (2022). COVID-19 and stressful adjustment to work: a long-term prospective study about homeworking for bank employees in Italy. Front. Psychol . 13, 843095. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.843095

Park, S. K., Rhee, M. K., and Barak, M. M. (2016). Job stress and mental health among nonregular workers in Korea: What dimensions of job stress are associated with mental health?. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health . 71, 111–118. doi: 10.1080/19338244.2014.997381

Parker, D. F., and DeCotiis, T. A. (1983). Organizational determinants of job stress. Organ. Behav. Human Perform . 32, 160–177. doi: 10.1016/0030-5073(83)90145-9

Phong, L. B., Hui, L., and Son, T. T. (2018). How leadership and trust in leaders foster employees' behavior toward knowledge sharing. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J . 46, 705–720. doi: 10.2224/sbp.6711

Piccarozzi, M., Silvestri, C., and Morganti, P. (2021). COVID-19 in manage studies: a systematic literature review. Sustainability . 13, 3791. doi: 10.3390/su13073791

Podsakoff, P. M., and Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: problems and prospects. J. Manage . 12, 531–544. doi: 10.1177/014920638601200408

Poms, L. W., Fleming, L. C., and Jacobsen, K. H. (2016). Work-family conflict, stress, and physical and mental health: a model for understanding barriers to and opportunities for women's well-being at home and in the workplace. World Med. Health Policy . 8, 444–457. doi: 10.1002/wmh3.211

Prasad, K., and Vaidya, R. W. (2020). Association among Covid-19 parameters, occupational stress and employee performance: an empirical study with reference to Agricultural Research Sector in Hyderabad Metro. Sustain. Humanosphere . 16, 235–253.

Purnomo, K. S. H., Lustono, L., and Tatik, Y. (2021). The effect of role conflict, role ambiguity and job stress on employee performance. Econ. Educ. Anal. J . 10, 532–542. doi: 10.15294/eeaj.v10i3.50793

Richardson, K. M., and Rothstein, H. R. (2008). Effects of occupational stress manage intervention programs: a meta-analysis. J. Occup. Health Psychol . 13, 69–93. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.13.1.69

Robbins, S. P. (2005). Essentials of Organizational Behavior (8th ed.) . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Saleem, F., Malik, M. I., and Qureshi, S. S. (2021). Work stress hampering employee performance during COVID-19: is safety culture needed? Front . Psychol . 12, 655839. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.655839

Sendjaya, S. (2015). Personal and Organizational Excellence Through Servant Leadership Learning to Serve, Serving to Lead, Leading to Transform . Berlin, Germany: Springer.

Sendjaya, S., Eva, N., Butar Butar, I., Robin, M., and Castles, S. (2019). SLBS-6: Validation of a short form of the servant leadership behavior scale. J. Bus. Ethics . 156, 941–956. doi: 10.1007/s10551-017-3594-3

Shah, S. H. A., Haider, A., Jindong, J., Mumtaz, A., and Rafiq, N. (2021). The impact of job stress and state anger on turnover intention among nurses during COVID-19: the mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Front. Psychol . 12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.810378

Shan, B., Liu, X., Gu, A., and Zhao, R. (2022). The effect of occupational health risk perception on job satisfaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health . 19, 2111. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19042111

Shimazu, A., Nakata, A., Nagata, T., Arakawa, Y., Kuroda, S., Inamizu, N., et al. (2020). PsychoSoc. impact of COVID-19 for general workers. J. Occup. Health . 62, e12132. doi: 10.1002/1348-9585.12132

Soeker, M. S., Truter, T., Van Wilgen, N., Khumalo, P., Smith, H., Bezuidenhout, S., et al. (2019). The experiences and perceptions of individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia regarding the challenges they experience to employment and coping strategies used in the open labor market in Cape Town, South Africa. Work . 62, 221–231. doi: 10.3233/WOR-192857

Song, L., Wang, Y., Li, Z., Yang, Y., and Li, H. (2020). Mental health and work attitudes among people resuming work during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health . 17, 5059. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17145059

Soomro, M. A., Memon, M. S., and Bukhari, N. S. (2019). Impact of stress on employees performance in public sector Universities of Sindh. Sukkur IBA J. Manage. Bus . 6, 114–129. doi: 10.30537/sijmb.v6i2.327

Spears, L. C. (2010). Character and servant leadership: ten characteristics of effective, caring leaders. J. Virtues Leadersh . 1, 25–30.

Tan, W., Hao, F., McIntyre, R. S., Jiang, L., Jiang, X., Zhang, L., et al. (2020). Is returning to work during the COVID-19 pandemic stressful? A study on immediate mental health status and psychoneuroimmunity prevention measures of Chinese workforce. Brain Behav. Immun . 87, 84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.055

Tănăsescu, R. I., and Ramona-Diana, L. E. O. N. (2019). Emotional intelligence, occupational stress and job performance in the Romanian banking system: a case study approach. Manage Dyn. Knowl. Econ . 7, 323–335. doi: 10.25019/MDKE/7.3.03

Tiedtke, C., Rijk, D. E., Van den Broeck, A. A., and Godderis, L. (2020). Employers' experience on involvement in sickness absence/return to work support for employees with Cancer in small enterprises. J. Occup. Rehabil . 30, 635–645. doi: 10.1007/s10926-020-09887-x

Tu, Y., Li, D., and Wang, H. J. (2021). COVID-19-induced layoff, survivors' COVID-19-related stress and performance in hospital industry: the moderating role of social support. Int. J. Hosp. Manage . 95, 102912. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102912

Uchmanowicz, I., Karniej, P., Lisiak, M., Chudiak, A., Lomper, K., Wiśnicka, A., et al. (2020). The relationship between burnout, job satisfaction and the rationing of nursing care—A cross-sectional study. J. Nurs. Manage . 28, 2185–2195. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13135

Xu, S., Wang, Y. C., Ma, E., and Wang, R. (2020). Hotel employees' fun climate at work: effects on work-family conflict and employee deep acting through a collectivistic perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manage . 91, 102666. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102666

Yu, D., Yang, K., Zhao, X., Liu, Y., Wang, S., D'Agostino, M. T., et al. (2022). Psychological contract breach and job performance of new generation of employees: Considering the mediating effect of job burnout and the moderating effect of past breach experience. Front . Psychol . 13, 985604. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.985604

Yunus, N. H., Mansor, N., Hassan, C. N., Zainuddin, A., and Demong, N. A. R. (2018). The role of supervisor in the relationship between job stress and job performance. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci . 8, 1962–1970. doi: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i11/5560

Keywords: COVID-19, work stress, mental health, employee performance, social uncertainty

Citation: Chen B, Wang L, Li B and Liu W (2022) Work stress, mental health, and employee performance. Front. Psychol. 13:1006580. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1006580

Received: 29 July 2022; Accepted: 10 October 2022; Published: 08 November 2022.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2022 Chen, Wang, Li and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Biao Li, lib0023@zzu.edu.cn

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

A Systematic Review of Workplace Stress and Its Impact on Mental Health and Safety

- Conference paper

- First Online: 02 December 2023

- Cite this conference paper

- Gabriella Maria Schr Torres 12 ,

- Jessica Backstrom 12 &

- Vincent G. Duffy 12

Part of the book series: Lecture Notes in Computer Science ((LNCS,volume 14055))

Included in the following conference series:

- International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction

465 Accesses

Workplace stress and health are important subsets of the safety engineering field. Engineers need to maintain physical, emotional, and mental health to be productive and safe employees, which is beneficial to their employers through the reduction of accidents. Besides the human element, which may involve injury, death, or other lasting physical or mental consequences, accidents cost companies time, money, and valuable resources spent on extensive litigation. This paper focuses on mental health within the context of workplace stress since the globally felt adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic have brought high priority to research on identifying and combating mental health problems. While most mental health research focuses on healthcare professionals, our contribution is the extrapolation of this research to engineering. A systemic literature review was performed, which consisted of gathering data, using multiple bibliometric software, and providing discussion and conclusions drawn from the metadata. The software utilized for analysis included Vicinitas, Scopus, Google n-gram and Google Scholar, VOSviewer, Scite.ai, CiteSpace, BibExcel, Harzing, and MaxQDA. The original keywords included “workplace stress”, “mental health”, and “engineering,” but our analysis revealed additional trending terms of mindfulness, nursing, and COVID-19. Our findings showed that workplace stress is experienced throughout multiple industries and causes significant harm to employees and their organizations. There are practical solutions to workplace stress studied in nursing and construction that can be applied to other fields that need intervention.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Influence of psychosocial safety climate on occupational health and safety: a scoping review

Occupational stress among workers in the health service in Zimbabwe: causes, consequences and interventions

Workplace Stress and Health: Insights into Ways to Assist Healthcare Workers During COVID-19

Goetsch, D.: Chapter 11: stress and safety. In: Occupational Safety and Health for Technologists, Engineers, and Managers, Ninth, pp. 243–55. New York, Pearson (2019)

Google Scholar

Brauer, R.: Section 31–6: job stress and other stresses in chapter 31: human behavior and performance in safety. In: Safety and Health for Engineers, Third, pp. 921–24. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley (2016)

Sallinen, M., Kecklund, G.: Shift work, sleep, and sleepiness differences betwen shift schedules and systems. Scandanavian J. Work, Environ. Health 36 (2), 121–133 (2010)

Article Google Scholar

Moustafa, A.: Mental Health Effects of COVID-19. Elsevier, London (2021)

Latino, F., Cataldi, S., Fischetti, F.: Effects of an 8-week yoga-based physical exercise intervention on teachers’ burnout. Sustain. (Switzerland) 13 (4), 1–16 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042104

Darling, E.L., et al.: A mixed-method study exploring barriers and facilitators to midwives’ mental health in ontario. BMC Women’s Health 23 (155) (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02309-z

Ayalp, G.G., Serter, M., Metinal, Y.B., Tel, M.Z.: Well-being of construction professionals: modelling the root factors of job-related burnout among civil engineers at contracting organisations. In: Advances in Sociology Research, vol. 40, pp. 1–38 (2023)

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). 2022. Healthcare Workers: Work Stress & Mental Health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1 Dec 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/healthcare/workstress.html

University of Maryland. 2023. Systematic Review. University Libraries. 12 April 2023. https://lib.guides.umd.edu/SR/welcome

World Health Organization (WHO). 2022. “Mental Health.” WHO Newsroom. 17 June 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-ourresponse

Wasser, J.: NASA for Kids: Intro to Engineering. National Geographic. 27 Sept 2022. https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/nasa-kids-intro-engineering/

Borenstein, J.: 2020. Stigma, Prejudice, and Discrimination Against People with Mental Illnesses. American Psychiatric Association. Aug 2020. https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/stigma-and-discrimination