Centre for Education and International Development (CEID), IOE

A forum for staff, students, alumni and guests to write about and around CEID's five thematic areas of engagement.

What do we mean by gender equality in education, and how can we measure it?

By CEID Blogger, on 18 May 2021

By Helen Longlands

Gender equality in education is a matter of social justice, concerned with rights, opportunities and freedoms. Gender equality in education is crucial for sustainable development, for peaceful societies and for individual wellbeing. At local, national and global levels, gender equality in education remains a priority area for governments, civil society and multilateral organisations. The United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals and 2020-2030 Decade of Action commit the global community to achieving quality education (Goal 4) and gender equality (Goal 5) by 2030. The G7 Foreign and Development Ministers, meeting this summer in the UK, have made fresh commitments to supporting gender equality and girls’ education , which build on those they made in 2018 and 2019 . Yet fulfilling these agendas and promises not only depends on galvanising sufficient support and resourcing but also on developing sufficient means of measuring and evaluating progress.

The urgency for gender equality in education has been compounded by the profound impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic, which has exposed, exacerbated and created new forms of intersecting inequalities and injustices associated with gender and education. School closures have resulted in millions more children out of school, many of whom may never return, particularly the poorest and most marginalised girls . While UNESCO estimates that over 11 million girls are at risk of not going back to school once the worst of the pandemic is over, the Malala Fund indicates this figure could be as high as 20 million . Cases of violence against women and children have also risen during the pandemic. A recent review by the Centre for Global Development of studies on low and middle income countries presents evidence of an increase in incidences of various forms of gender-based violence, including intimate partner violence, harassment, and violence against children. Assessment by UN Women connects this rise in violence to Covid-19 measures and consequences, including the closures of schools, suspension of community support systems, and increasing rates of unemployment and alcohol abuse. Meanwhile, heavier burdens of caregiving responsibilities during the pandemic, as well as reduced access to sexual and reproductive health knowledge and resources , limited availability of technology to support learning , and low levels of digital technology skills have gendered dimensions and risk further widening existing gender inequalities and power imbalances associated with education.

The effects of the pandemic add to the challenges of achieving gender equality in education and to the complexities involved in evaluating progress towards it. As we continue to develop and extend response, recovery and sustainability initiatives, to build back better , it is important to have explicit and honest discussions about gender and other intersecting inequalities in education. And it is vital to ensure we have robust and reliable ways of identifying, evaluating and holding people to account for these inequalities and their underlying causes in order to build more just and resilient societies. How we do this, however, is not straightforward and presents many conceptual and practical challenges around understanding, accessing and utilising the information, resources and approaches we need. What do we mean when we talk about gender equality in education, how can we measure progress towards it, and how will we know when we achieve it?

The AGEE project’s theoretical and methodological approach draws on key ideas from the capability approach, including the importance of public debate and democratic deliberation, recognition of how inequalities, opportunities and freedoms connect to the complexities of the physical, political and social environment as well as the distribution of resources, and a focus on both the interpersonal and the individual. We see these ideas as crucial components to identifying, understanding and meaningfully measuring gender inequalities and equality in education in diverse local contexts in ways that capture both unique and more general issues as well as longstanding and emerging concerns.

Thus our aim is to help refocus the policy attention beyond gender parity in education to a more substantive understanding and recognition of what gender equality in education could or should entail within and across different contexts, and provide clarity on the data needed for public policy. Gender parity comprises a simple ratio of girls to boys or women to men in a given aspect of education, such as enrolment, participation, attainment or teacher deployment. Gender parity is a clear and uncomplicated measure, which makes it appealing to policymakers and practitioners, and has led to its widespread use as a measure of gender equality in education in national and global development frameworks. This is seen in many of the targets for SDG4 on education and previously in the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (2000-2015). However, gender parity is also an inadequate measure on its own because it is unable to capture more complex forms of gender inequality, the conditions and practices that underpin them, the ways in which they intersect with other forms of inequality and injustice, and the short and longer term consequences for individuals and societies. While it is important to ensure all children can access, attend and complete school, which are all issues that gender parity can monitor, it cannot measure issues such as girls’ or boys’ lived experiences of gender discrimination or violence in and around school, or gender inequalities associated with curricula, learning materials, pedagogic approaches or work practices.

Ongoing consultations and debates with stakeholders at community, national and international level are thus key components of AGEE’s research approach. Through them, we have sought to develop a deeper understanding of local, national and global forms of gender inequality and injustice in education and the ways these interconnect. We have scrutinised whether or not existing measurement techniques document this in order to enhance work on gender equality in policy and practice. Over the past few years, through workshops, interviews, technical meetings, academic papers, conference presentations, seminars and teaching, we have engaged in critical participatory dialogue with a wide range of key national and international stakeholders in education and gender, including representatives from governments, national statistics offices, civil society, international organisations, academics and students. This dialogue has explored and interrogated understandings of and debates around gender, accountability, measurement and data, and collated information on the range of factors, relationships, conditions and available data associated with gender equality in education.

Through this in-depth participatory process, we have developed, adapted and refined the AGEE Framework. The Framework is designed to be robust and comprehensive as well as flexible and adaptable, in order both to capture complex, enduring and widespread forms of inequalities, and to be responsive to local characteristics and changing conditions, including forms of crisis. The AGEE Framework comprises six interconnected domains for monitoring and evaluating gender equality in education: Resources; Values; Opportunities; Participation in Education; Knowledge, Understanding and Skills; and Outcomes. And we have identified a number of indicators and related existing or potential data sources to populate these domains.

If you would like to learn more about the AGEE project and engage with our work to support gender equality in education, please visit our website: www.gendereddata.org , where you can find more information about our research and the AGEE Framework, and join our community of practice.

Join the special event on May 27, 2021 where the AGEE Framework will be presented in detail : The politics of measuring gender equality in education: Perspectives for the G7

Acknowledgements:

Members of the AGEE project team: Elaine Unterhalter (UCL and AGEE PI), Rosie Peppin Vaughan (UCL), Relebohile Moletsane (UKZN), Esme Kadzamira (University of Malawi) and Catherine Jere (UEA).

Filed under CEID , Gender , Inequalities

One Response to “What do we mean by gender equality in education, and how can we measure it?”

your blog is very useful and your content ideas is wonderful nice job…

Leave a Reply

Name (required)

Mail (will not be published) (required)

CEID | Twitter | Facebook

Recent Posts

- Demystifying Doctoral Research Fieldwork – “Expecting the Unexpected”

- A Call for Peace with Justice in the Occupied Palestinian Territories and Israel – recognising the pivotal role of education

- The perfect immigration policy? ‘Educate’ children of migrants to pull up the drawbridge

- Learning the history, identity, and education of Tibetans-in-exile through Tibetan Terms

- The Elephant in the (Class)room

Subscribe by Email

Completely spam free, opt out any time.

Please, insert a valid email.

Thank you, your email will be added to the mailing list once you click on the link in the confirmation email.

Spam protection has stopped this request. Please contact site owner for help.

This form is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Gender stereotypes: Primary schools urged to tackle issue

- Published 31 May 2021

Tackling gender stereotypes could help prevent violence, the letter suggests

Calling girls "sweetie" or boys "mate" in primary school perpetuates gender stereotypes, campaigners say.

In a letter to the education secretary in England, various groups are calling on the government to address the language and ideas used in schools.

Stereotypes limit children's aspirations and create inequalities that help fuel gender-based violence, they say.

The government says challenging stereotypes is in its guidance.

The letter to Education Secretary Gavin Williamson is signed by various groups including Girlguiding UK, the Fawcett Society and the National Education Union.

It says the curriculum, books and language used in schools reinforce ideas of how girls and boys should look and behave.

It suggests schools should "actively challenge gender stereotypes" from an early age before they become ingrained.

Gender stereotypes in adverts banned

Fathers of girls 'less prone to sexism'

NSPCC abuse helpline 'takes hundreds of calls'

"Evidence shows us that gender stereotyping is everywhere and it causes serious, long-lasting harm," according to Felicia Willow, chief executive of the Fawcett Society, which campaigns for gender equality.

"These stereotypes are deeply embedded, they last a lifetime and we know they are one of the reasons we see violence against women and girls," she said.

The debate about a culture of sexual abuse in schools has escalated in recent months after the website Everyone's Invited, set up to allow survivors of sexual abuse to share their experiences, attracted more than 16,000 posts. Some were from children as young as nine.

The letter calls for schools to be a key part of the response and urges the government to ensure more specialist resources and training are made available to nurseries and primary schools.

It suggests this could lead to an improvement in other areas such as encouraging more girls to study science, technology and maths, helping to improve boys' reading skills and increasing children's well-being.

Lifting Limits, one of the signatories to the letter, is a charity that works with primary schools, enabling teachers and pupils to learn how to spot and challenge stereotypes.

Its chief executive, Caren Gestetner, says without sexist intent, language can often perpetuate ideas about what it means to be "normal" as a girl or boy.

She says examples include addressing boys as mate or girls as sweetie or using phrases such as, "We need a strong man to open that", or, "Make sure you ask Mummy to sign the form".

'Gender detectives'

Teacher Megan Quinn, who works at Gospel Oak Primary School in north London, said the whole school started "questioning things together, looking and thinking like gender detectives".

Pupils spotted examples in books and noticed that the actions in a French lesson, which were being used to teach masculine and feminine articles like "le" or "la", were based on gender stereotypes.

Staff also examined the curriculum and decided to add more female scientists and composers while a lesson about dance looked at male dancers.

The letter also calls on the government to ensure a new compulsory Relationships and Sex Education (RSE) curriculum, introduced last autumn, is fully rolled out in England.

It focuses on relationships in primary schools and sex and relationships in secondary schools.

Due to the pandemic, schools were allowed to delay the lessons until the summer term.

A spokesperson for the Department for Education said: "Schools should be places where all pupils feel safe and are protected from harm."

"Important issues such as personal privacy, consent and challenging stereotypes about gender are part of our guidance to ensure more young people have a better understanding of how to behave towards their peers, including online."

Ofsted is also undertaking a review into safeguarding measures in schools and colleges in England which will be published shortly.

Related Topics

- Violence against women

- Sex education

- Influential Trans People of the Last 100 Years

- Gender Pay Gaps in the UK

- Gender Inequality in the British Education System

- By Gina in Gender Issues

Despite attempts to counter gender inequality issues in the United Kingdom, it is still possible to see inequality in the British education system. Some of these problems are structural, whereas other issues are problems which are caused by wider society. Inequality within the education system can lead to inequality when the pupils grown up, including implications in terms of future employment prospects.

Achievements

Recent data analysis suggests that boys are struggling to keep up with girls at key curriculum milestones. By Key Stage 2 (7 to 11 year olds) girls are already moving ahead of boys in their test scores. In the 2015 test scores, around 83% of girls achieved a level 4 or higher score, whereas only 77% of boys in the same age group were able to attain level 4 or higher. These trends continued up to GCSE level, with around 10% more girls earning 5 or more A* – C grades than boys who were achieving the same standard.

There is now a disparity amongst the amount of male and female school-leavers applying to university. UCAS data suggests that female school-leavers in England are 35% more likely to apply for university than their male peers are. This gap widens even further amongst applicants from the lowest socio-economic backgrounds. Women from disadvantaged backgrounds are 58% more likely to apply for university than men from the same background.

Another inequality issue within the British education system is the difference in levels of men and women who are employed as teaching and support staff. Just 15% of primary school teachers are male, meaning that many children are lacking a positive male role model within their educational framework. Some schools do not have any male staff members at all. This can be particular problematic for children with learning difficulties that mean that they respond better with men.

Around 38% of teachers in state secondary school are male, but there is still a gender divide based on the subjects taught by men. Male teachers are more likely to specialise in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) and PE, whereas women are more likely to teach humanities and languages. A lack of educational role models in STEM and PE can put some girls off taking these subjects. The effect is particularly visible amongst teenage girls who feel that male PE teachers cannot understand their needs properly.

Research also suggests that male teachers are more likely to be employed in high ranking roles within a school, such as Head of Department or Head Teacher. Studies have shown that many women in education see their role as vocational and prefer teaching to administrative or managerial roles, even though the pay grade is lower. One of the major challenges for the education system is making Head Teacher roles more appealing to female applicants.

Many schools say that they would like to hire more male teachers; however fewer men apply for each advertised role in teaching. The Department of Education is currently discussing strategies to recruit and retain more male teachers, and to encourage male teachers to consider a wider range of subjects.

Sexism within Education

Over three quarters of female secondary school pupils in the UK who attend mixed schools claim that they have been on the receiving end of sexist comments from other pupils. There are also concerns about the sexualisation of young girls within the educational environment. It is now harder than ever for young people to escape from sexism and sexualisation, due to the increased use of social media. Many young people do not know where to turn when they receive unwanted sexual content or comments from their peers when they are outside of the classroom.

Many male pupils have also stated that they feel under intense pressure to look and act in a certain way. The number of adolescent males who are suffering from body dysmorphia has increased in recent years. Male pupils must also be supported with previously under-reported problems.

In order to reduce sexism and sexualisation over social media, schools must improve their reporting and safeguarding policies. More should be done to encourage pupils to come forwards if they are suffering from sexism. Sexism should also be studied in a wider social context to help to educate pupils.

29 comments

Skip to comment form

- Mirade pretty on 15/11/2018 at 7:59 PM

If the world was as understanding 25 years ago I would be a woman called mirade and work in fashion. I have now found the courage to be myself but I know that I am in for a bumpy ride. Looking for funding. I have had to struggle all my life and have ended up with no savings. But soon as I am able I am really looking forward to being a female employee. I have been a carpenter forman on Heathrow t5 and gchq Twickenham rugby ground and am a good worker. I am hoping for the best advice you can give me. I suffer from anxiety and finding it hard to get help. Xxxx

- Sally on 22/01/2019 at 10:24 AM

Cheers for that!

- mary on 14/05/2019 at 10:58 AM

Unfortunately I completely understand where your coming from. As a now middle aged women I have lost so many opportunities in life due to my gender, they all say the world is your oyster but for us women it is not! I hope my children do not face the same sexism I have undergone x

- John on 30/09/2019 at 2:50 PM

As a male from a working class background in the ’80’s, I was the first member of my family to go into higher education ( At a Polytechnic ) to do a degree. I didn’t feel I fitted in with the middle class environment and fell into a laddish culture with a few other similar lads. Needless to say, my work ethic wasn’t there and I got a poor degree. Luckily for me I later did a second degree by correspondence in a subject I was passionate about and got a decent degree. I’m now a Primary school teacher but still feel like an imposter among the largely middle class workforce.

- Jeremy Jacobs on 25/10/2019 at 1:32 PM

“Recent data analysis suggests that boys are struggling to keep up with girls at key curriculum milestones. ” Can someone please explain to me why this is an “”achievement”?

- L on 11/06/2020 at 1:02 PM

Because the author is a misandrist?!

- Emily Clarke on 25/10/2022 at 1:57 PM

I sensed that also.

- Alex on 11/07/2020 at 5:09 PM

I don’t think the author is claiming it’s an achievement that boys are struggling to keep up with girls. Rather, the section is called Achievements in reference to test scores and university applications, and then the content is that boys have lower test scores i.e. lower levels of achievement.

- Ruth on 07/12/2019 at 1:00 PM

Dear, dear …. “Boys are struggling to keep up with girls at key curriculum milestones”: 83% of girls versus 77% of boys, is cited as one example of data supporting this …. a difference of 6%? Perhaps Gina had a string of very poor maths teachers in high school and in science too (I’m a science teacher myself) to interpret a 6% difference as real evidence of struggling. And now we’ve got a problem of too many women going to university, apparently! … And I think the argument about too few female science teachers is now well and truly redundant. Certainly, it does seem easier to recruit male than female maths teachers but in fact, it’s hard to recruit maths teachers full-stop … If there were no female maths teachers in a school, I would find that disappointing and concerning. But a story I find of far greater interest is John’s and the problem of a cultural class-divide and exclusion (which goes beyond gender). Genuinely opening up the horizons of working class kids is surely a pressing issue , and is no doubt influenced by the way the profession presents itself, eg negatively if perhaps too middle-class. Genuine diversity amongst the teacher population, and within schools, is surely essential and best for all students.

- M on 13/01/2020 at 9:43 PM

As a science teacher, I would expect you to understand statistics better than to simply discount a figure as irrelevant. Given the number of students this figure is based upon, 6% is certainly significant and will have a low margin of error. This is also significant due to the fact that once behind, it’s difficult to catch up, as I hope you would be aware of as a teacher.

- A bloke on 22/08/2023 at 10:44 PM

Dearest Jeremy and your acolytes

Looks like you have completely misinterpreted what is meant by Achievements. The heading “achievement” is to show how there is a great disparity of academic achievement concerning boys and girls. The conclusion is that the current education system is clearly working against boys ability to achieve as well as girls and those from low income backgrounds on particular.

In other words you missed the point entirely presumably as you are so enamoured of the idea of finding evidence of misandry (of which there is not a shred).

What motivated this interpretation? Or was it perhaps a failing in your education – which is ironic, don’t you think?

- Rory on 29/12/2021 at 12:29 AM

Exactly right Ruth!

- Darren Newton on 29/01/2024 at 1:58 PM

The author is not saying it is an achievement. Rather, it’s a statistic about how young people are achieving in education based on test scores etc- not necessarily a positive or negative statement but just a statistic.

- Darren on 19/06/2020 at 8:46 PM

Femanism is the real problem. Before you groan and roll your eyes please read on. Female teachers are over represented in the class room, therefore Femanism is over represented in the class room. Femanism isn’t about true equality anymore, It’s about cherry picking what they want to keep and ignoring the inconvienient bits. Gender bias against boys is rampant, especially in Primary and Secondary settings. Dont beleive me…pick a random set of state secondary school websites (and colleges come to that) and you will see a huge bias towards promoting girls in a positive light. Some websites will leave you wondering whether boys even attend said institution let alone if they actually achieve anything. It has been going on for so long most don’t even notice the bias. Its perpetuated via subtle and some not so subtle positive discrimination against boys. A lot of parents are not well informed or in the know as to what and how subjects are taught in school these days, due to their hectic lives and lack of spare time. Also schools hide behind a cloak of opaqueness, blaming lack of resources for a lack of transparency. If you take into account the amount of positive discrimination against boys and the fact that boys develop later than girls and only catch up by the age of 18 years, boys are doing really well to be where they are!

The comment Ruth made is indicative of a biased teacher, someone who is indoctrinated (knowingly or unknowingly) into the positive discrimination culture against boys. I would be concerned if she was teaching my Sons with such an attitude towards a problem that is now being taken very serious at the highest levels of government.

Ruth is more interested in ‘cultural class-divide and exclusion (which goes beyond gender)’ except roughly 50% of those individuals will be male. This is nothing more than an attempt to divert attention away from the elephant in the room, an inconvenient truth.

- Anna on 12/02/2021 at 11:55 PM

Darren, at least you feel once like women for last hundreds of years. So from my perspective a few years with girls on the main cover is like a drop in an ocean. In my view, we need to all strive to create a society where there is a place for everyone to be themselves, stop feeding children with things like boys are curious and girls are naughty. Despite the window dressing on the school websites as a mother (of a boy and a girl) I still feel the curriculum for a meaningful gender balanced approach is not there.

Trust me your boys will have (as you had) a better starting position than many girls due to cultural often home grown understanding of world , but I can completely understand that any attempt to change that dominance is uncomfortable for fathers and many mothers of boys to accept.

- jeame on 16/06/2022 at 10:52 PM

That doesn’t make sense girls do better all through education and they are studies that show that female teachers treat boys differently, and even mark them lower for the same work.

- Joe on 19/08/2022 at 12:47 PM

That’s not true though, boys fall behind at all levels of education and are far less likely to go university than girls, and boys from disadvantage areas are even more affected, and women seen to get the best start they get paid more and better job opportunities until their mid 30s.

- Emily Clarke on 25/10/2022 at 2:11 PM

“A gender-balanced approach” is just a synonym for “suitable for girls”. Boys and girls are not the same yet the curriculum and classroom applaud females and feminine behaviour and chastise typical male behaviour. Girls get a gold star and boys get judged as dysfunctional females and put on medication. The classroom environment is torture for young boys and unfortunately modern feminism thinks they deserve it which is a bit of a problem when the majority of teachers are middle-class female liberals.

- Adam Charles on 26/06/2023 at 11:14 PM

So two wrongs make a right? Like I would not mind, you have shown the approach to the issues men and boys face on a daily basis, is to wrtie if off due to “toxic masculinity”, and use straw man arguments that men and boys are raised to be entitled, and boys are curious and girls are naughty, when those things are not the case.

Until we admit, that the problems men and boys at least in education exist, and are due to sexism, and look at the real issues men and boys face, we won’t have parity, and certainly not equality.

- L on 19/06/2021 at 7:20 PM

you really shouldn’t raise children with that attitude dazza?

- DAZZA on 27/09/2022 at 10:11 AM

Yass slay agreed! dazza, You should not even be able to raise a lemon with that attitude!

- A bloke on 22/08/2023 at 10:53 PM

Is it feminist that more women than men work in occupations such as teaching and nursing?

far ore senior medics are men than women (majority of nurses) and so

Is it feminist at secondary level, that women make up 62 per cent of the workforce but just 38 per cent of headteachers. Those 62% being – you guessed it MEN.

And most early years childcare providers have women staff showing that women should play a caring and nurturing role rather than men – how is that feminist exactly?

I recommend you do some reading on the subject. You’ll be surprised how your understanding can be improved

- Darren Churchill on 30/06/2020 at 10:21 AM

I recently added a comment relating to the Gender Inequality in the British Education System. It has not been added to the comments section. Please could you explain why? Thank you.

- Gina on 08/07/2020 at 11:25 AM Author

I have been busy with other things but I’ve added your comment now. Thank you.

- Kevin Heath on 25/02/2021 at 8:48 PM

Keep going like your going now in western world and we will eventually get to the stage no males go to university only females. Or at least no white males. For absolute sure we are close to that as regards no poor white boys going to university. They are not helped by female teachers who cheat and mark up girls scores and mark down boys scores. Such so called teachers who systematically cheat a whole gender outta their greatest chance to build a good life should be sacked and prosecuted.

- Cherry on 23/03/2021 at 9:06 AM

My 11 year old boy said this morning before school why are girls treated differently to boys, he explained he lost 5 mins of break yesterday and a girl in he’s class did the same thing and didn’t loose any time ? In nursery girls were nurtured more than boys I noticed teachers had a preference for girls could this have something to do with it

- Saad on 15/01/2022 at 9:25 AM

In my view, we all are same . Only social division makes us divided.

- Gary on 27/07/2023 at 9:29 AM

It’s time to admit that the problem lies with boys themselves, not with perceived inequality of treatment. Boys and girls were achieving nearly equally up until the mid 1980’s. So what happened? . . . There was a big change in the social aspect of education in the 1980’s which reflected a general social change in society. In schools this was known as School Centred, and Child Centred Education, In School Centred Education schools decided how children were to be taught which was usually within a rigid framework (as I well remember being a pupil of the 1950s/1960s). This particularly suited boys as their learning was directed, often in a disciplined environment. With the movement to Child Centred Education (where the child directs their own education) boys have generally lost their way whereas girls tend to be independent learners and naturally aspire. Boys, on the other hand, generally languish and do no more than absolutely necessary, and are more disruptive. Additionally boys receive a rush of testosterone around age 14 which tends to make them more resistant to being taught. This was countered in my school days by my mother who drove me to succeed at school. This parental encouragement and discipline is now sadly lacking generally, and boys need it the most! Indian and Chinese parents still provide this parental support for their children and their boys are achieving at least as well as their girls. They also outperform all other ethnic groups. Unfortunately I believe that the social change that has led to boys’ underachievement is irreversible.

- Bea on 02/02/2024 at 9:15 AM

Hi, loved this article, I am currently writing a master assignment on the topic of gender bias in UK classrooms, i was hoping You’d be able to provide some of the sources for the data referred to.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your e-mail address will not be published.

Recent Posts

- Should Toys be Gender Specific?

- Gender-based Violence

Recent Comments

- Diana on Influential Trans People of the Last 100 Years

- Bea on Gender Inequality in the British Education System

- Darren Newton on Gender Inequality in the British Education System

- A bloke on Gender Inequality in the British Education System

- Privacy Policy

© 2024 GenderTrust.org.uk.

- Universities

The gender gap

Parents overestimate sons’ maths skills more than daughters’, study finds

Brief letters Goodbye to gallery audio guides at last

Opinion More women are thriving in science – does that mean attitudes have changed?

More than half of British girls lack confidence learning maths, poll finds

Dame Teresa Rees obituary

First Edition newsletter Wednesday briefing: Five key issues facing women – from misogyny to the ‘motherhood penalty’

Female university graduates have bigger Hecs debts but earning less than men, research reveals

The Zoom revolution largely benefited men. Is job sharing the way forward for women’s workplace flexibility?

Australian Politics ‘The prize is enormous’: can Australia achieve full gender equality?

We must raise boys’ attainment – but not at the expense of girls

If i mention the ‘modern male struggle’, do you roll your eyes it’s time to stop looking away.

Offensive graffiti, attitudes targeted in NSW bid to improve conditions for female construction workers

Lionesses’ legacy at risk as school PE fails girls, experts warn

Underestimated: why young women are shying away from economics

Covid has intensified gender inequalities, global study finds

Girls overtake boys in A-level and GCSE maths, so are they ‘smarter’?

Women in technology Why aren’t more girls in the UK choosing to study computing and technology?

Johnson accused of hypocrisy over G7 girls’ education pledge

Gender stereotyping is harming young people's mental health, finds UK report

Uk's white female academics are being privileged above women – and men – of colour.

- Higher education

- Gender pay gap

- Women (Society)

The UK education system preserves inequality – new report

- Imran Tahir

Published on 13 September 2022

Our new comprehensive study, shows that education in the UK is not tackling inequality.

- Education and skills

- Poverty, inequality and social mobility

- Social mobility

Link to read article

The Conversation

Your education has a huge effect on your life chances. As well as being likely to lead to better wages, higher levels of education are linked with better health, wealth and even happiness . It should be a way for children from deprived backgrounds to escape poverty.

However, our new comprehensive study , published as part of the Institute for Fiscal Studies Deaton Review of Inequalities , shows that education in the UK is not tackling inequality. Instead, children from poorer backgrounds do worse throughout the education system.

The report assesses existing evidence using a range of different datasets. These include national statistics published by the Department for Education on all English pupils, as well as a detailed longitudinal sample of young people from across the UK. It shows there are pervasive and entrenched inequalities in educational attainment.

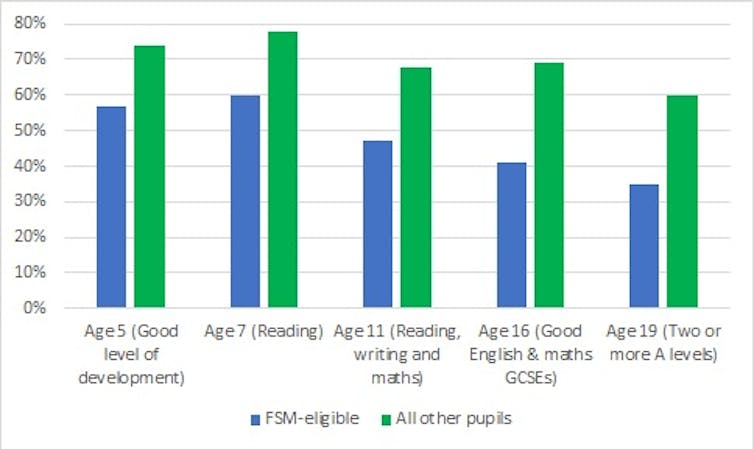

Unequal success

Children from disadvantaged households tend to do worse at school. This may not be a surprising fact, but our study illustrates the magnitude of this disadvantage gap. The graph below shows that children who are eligible for free school meals (which corresponds to roughly the 15% poorest pupils) in England do significantly worse at every stage of school.

Even at the age of five, there are significant differences in achievement at school. Only 57% of children who are eligible for free school meals are assessed as having a good level of development in meeting early learning goals, compared with 74% of children from better off households. These inequalities persist through primary school, into secondary school and beyond.

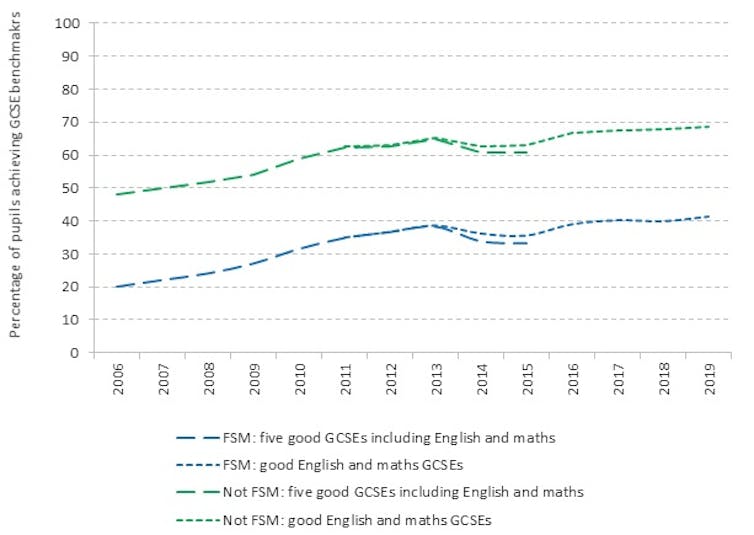

Differences in educational attainment aren’t a new phenomenon . What’s striking, though, is how the size of the disadvantage gap has remained constant over a long period of time. The graph below shows the percentage of students in England reaching key GCSE benchmarks by their eligibility for free school meals from the mid-2000s.

Over the past 15 years, the size of the gap in GCSE attainment between children from rich and poor households has barely changed. Although the total share of pupils achieving these GCSE benchmarks has increased over time, children from better-off families have been 27%-28% more likely to meet these benchmarks throughout the period.

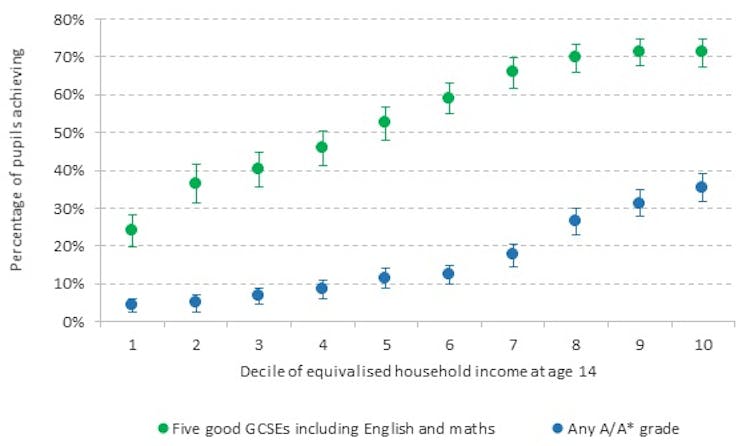

Household income

While eligibility for free school meals is one way of analysing socio-economic inequalities, it doesn’t capture the full distribution of household income. Another way is to group young people according to their family income. The graph below shows young people grouped by decile. This means that young people are ordered based on their family’s income at age 14 and placed into ten equal groups.

The graph shows the percentage of young people in the UK obtaining five good GCSEs, and the share obtaining at least one A or A* grade at GCSE, by the decile of their family income. With every increase in their family’s wealth, children are more likely to do better at school.

More than 70% of children from the richest tenth of families earn five good GCSEs, compared with fewer than 30% in the poorest households. While just over 10% of young people in middle-earning families (and fewer than 5% of those in the poorest families) earned at least one A or A* grade at GCSE, over a third of pupils from the richest tenth of families received at least one top grade.

Inequalities into adulthood

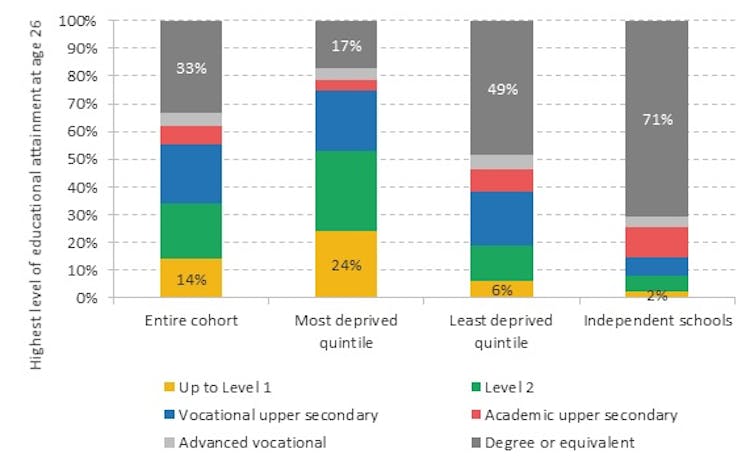

The gaps between poor and rich children during the school years translate into huge differences in their qualifications as adults. This graph shows educational attainment ten years after GCSEs (at the age of 26) for a group of students who took their GCSE exams in 2006.

The four bars show the distribution of qualifications at age 26 separately for the entire group, people who grew up in the poorest fifth of households, those who grew up in the richest fifth of households, and those who attended private schools.

There is a strong relationship between family background and eventual educational attainment. More than half of children who grew up in the most deprived households hold qualifications of up to GCSE level or below. On the other hand, almost half of those from the richest households have graduated from university.

The gap between private school students and the most disadvantaged is even more stark. Over 70% of private school students are university graduates by the age of 26, compared with less than 20% of children from the poorest fifth of households.

Young people from better-off families do better at all levels of the education system. They start out ahead and they end up being more qualified as adults. Instead of being an engine for social mobility, the UK’s education system allows inequalities at home to turn into differences in school achievement. This means that all too often, today’s education inequalities become tomorrow’s income inequalities.

Research Economist

Imran joined the IFS in 2019 and works in the Education and Skills sector.

Comment details

Suggested citation.

Tahir, I. (2022). The UK education system preserves inequality – new report [Comment] The Conversation. Available at: https://ifs.org.uk/articles/uk-education-system-preserves-inequality-new-report (accessed: 20 May 2024).

More from IFS

Understand this issue.

Sure Start achieved its aims, then we threw it away

15 April 2024

Why inheritance tax should be reformed

18 January 2024

How important is the Bank of Mum and Dad?

15 December 2023

Policy analysis

The short- and medium-term impacts of Sure Start on educational outcomes

9 April 2024

Sure Start greatly improved disadvantaged children’s GCSE results

What you need to know about the new childcare entitlements

28 March 2024

Academic research

Police infrastructure, police performance, and crime: Evidence from austerity cuts

24 April 2024

Imagine your life at 25: Gender conformity and later-life outcomes

Labour market inequality and the changing life cycle profile of male and female wages

Gender inequality in the UK - Statistics & Facts

Gender pay gap, views on gender equality, key insights.

Detailed statistics

Gender pay gap in the UK 1997-2023

Average annual earnings for full-time employees in the UK 1999-2023, by gender

Gender pay gap in the UK 2023, by sector

Editor’s Picks Current statistics on this topic

The global gender gap index 2023

Business Enterprise

Share of female held leadership positions in FTSE companies UK 2022

Politics & Government

Women's opinion on progress in gender balance in politics Great Britain 2024

Further recommended statistics

Positions of power.

- Basic Statistic The global gender gap index 2023

- Basic Statistic Share of female held leadership positions in FTSE companies UK 2022

- Premium Statistic Proportion of females MPs in the UK Parliament 1979-2019

- Basic Statistic Number of female MPs in the UK parliament 1979-2019, by party

- Premium Statistic Proportion of women in government cabinets in the UK 2004-2023

Share of female held leadership positions in FTSE companies in the United Kingdom in 2022

Proportion of females MPs in the UK Parliament 1979-2019

Proportion of Female Members of Parliament in the United Kingdom from 1979 to 2019

Number of female MPs in the UK parliament 1979-2019, by party

Number of female Members of Parliament in the United Kingdom from 1979 to 2019, by political party

Proportion of women in government cabinets in the UK 2004-2023

Proportion of female cabinet members in governments of the United Kingdom from 2004 to 2023

- Basic Statistic Gender pay gap in the UK 1997-2023

- Basic Statistic Gender pay gap in the UK 1997-2023, by age

- Basic Statistic Average annual earnings for full-time employees in the UK 1999-2023, by gender

- Basic Statistic Average weekly earnings for full-time employees in the UK 1997-2023, by gender

- Basic Statistic Average full-time hourly wage in the UK 1997-2023, by gender

- Basic Statistic Average weekly earnings for full-time employees in the UK 2023, by age and gender

- Premium Statistic Gender pay gap in the UK 2023, by sector

Gender pay gap for median gross hourly earnings in the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2023

Gender pay gap in the UK 1997-2023, by age

Gender pay gap for full-time median gross hourly earnings in the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2023, by age group

Median annual earnings for full-time employees in the United Kingdom from 1999 to 2023, by gender (in nominal GBP)

Average weekly earnings for full-time employees in the UK 1997-2023, by gender

Median weekly earnings for full-time employees in the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2023, by gender (in nominal GBP)

Average full-time hourly wage in the UK 1997-2023, by gender

Median hourly earnings for full-time employees in the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2023, by gender (in nominal GBP)

Average weekly earnings for full-time employees in the UK 2023, by age and gender

Median weekly earnings for full-time employees in the United Kingdom in 2023, by age and gender (in GBP)

Gender pay gap for gross hourly earnings in the United Kingdom in 2023, by industry sector

- Basic Statistic Number of people unemployed in the UK 1971-2024, by gender

- Basic Statistic Unemployment rate in the UK 1971-2024, by gender

- Basic Statistic Youth unemployment rate in the UK 1992-2024, by gender

- Basic Statistic Employment rate in the UK 1971-2023, by gender

- Basic Statistic Number of self-employed workers in the UK 1992-2024, by gender

- Basic Statistic Overall weekly hours worked in the UK 1971-2023, by gender

Number of people unemployed in the UK 1971-2024, by gender

Number of people unemployed in the United Kingdom from 1st quarter 1971 to 1st quarter 2024, by gender (in 1,000s)

Unemployment rate in the UK 1971-2024, by gender

Unemployment rate in the United Kingdom from 1st quarter 1971 to 1st quarter 2024, by gender

Youth unemployment rate in the UK 1992-2024, by gender

Youth unemployment rate in the United Kingdom from 2nd quarter 1992 to 1st quarter 2024, by gender

Employment rate in the UK 1971-2023, by gender

Employment rate in the United Kingdom from 1st quarter 1971 to 4th quarter 2023, by gender

Number of self-employed workers in the UK 1992-2024, by gender

Number of self-employed workers in the United Kingdom from 2nd quarter 1992 to 1st quarter 2024, by gender (in 1,000s)

Overall weekly hours worked in the UK 1971-2023, by gender

Overall weekly hours worked for all employees in the United Kingdom from 1st quarter 1971 to 4th quarter 2023, by gender (in million hours worked)

- Basic Statistic Women's opinions on if equal pay has been achieved Great Britain 2024

- Basic Statistic Women's opinion on progress in gender balance in politics Great Britain 2024

- Basic Statistic Women's opinion on progress in equality in household responsibilities in Britain 2024

- Basic Statistic Women's opinion on progress in addressing sexual misconduct Great Britain 2024

- Premium Statistic Attitudes towards gender equality in Great Britain 2019, by gender

- Premium Statistic Most important issues faced by women and girls in Great Britain 2019

- Premium Statistic Actions for achieving gender equality in Great Britain 2019

- Premium Statistic Confidence in gender equality progressing in Great Britain 2019, by area

Women's opinions on if equal pay has been achieved Great Britain 2024

Do you personally think gender equality has been achieved in relation to equal pay? (August 2019 to February 2024)

Women's opinion on progress in gender balance in politics Great Britain 2024

Do you think gender equality has been achieved in relation to equal gender balance in politics? (August 2019 to February 2024)

Women's opinion on progress in equality in household responsibilities in Britain 2024

Do you think gender equality has been achieved in relation to household responsibilities? (August 2019 to February 2024)

Women's opinion on progress in addressing sexual misconduct Great Britain 2024

Do you think gender equality has been achieved in relation to openly talking about / addressing sexual misconduct? (August 2019 to February 2024)

Attitudes towards gender equality in Great Britain 2019, by gender

Attitudes towards gender equality in Great Britain in 2019, by gender*

Most important issues faced by women and girls in Great Britain 2019

Which of the following do you think are the most important issues facing women and girls in Great Britain?*

Actions for achieving gender equality in Great Britain 2019

To what extent do you think the following actions would make a positive impact to achieving gender equality?

Confidence in gender equality progressing in Great Britain 2019, by area

How confident do you feel that discrimination against women in Great Britain will have ended in the next 20 years in the following areas?

Further reports

Get the best reports to understand your industry.

- Wage inequality in the U.S.

- Gender inequality in Italy

- Gender pay gap in the financial sector in the United Kingdom

- Gender inequality in the UK

Mon - Fri, 9am - 6pm (EST)

Mon - Fri, 9am - 5pm (SGT)

Mon - Fri, 10:00am - 6:00pm (JST)

Mon - Fri, 9:30am - 5pm (GMT)

The Importance of Collaborative Non-Government and Government Efforts to advance Equal Education: Enhancing Gender Equality and Social Inclusion

The Importance of Non-Government and Government Collaborative Efforts to advance Equal Education: Enhancing Gender Equality and Social Inclusion

With the Education World Forum taking place next week in London, 120 Ministers from 114 countries will come together to try to answer the forum’s overarching question: ‘ How should we prioritise policy and implementation for Stronger, Bolder, Better, Education?’

Within the education sector, Gender Equality and Social Inclusion (GESI) work can often be siloed and marginalised, but the techniques used by GESI experts to facilitate organisational, policy and pedagogical shifts are among the most advanced techniques in the development and humanitarian sectors, and much can be learned from feminist methodologies to answer the broad question posed by the Education World Forum’s for this year’s gathering.

To achieve meaningful and lasting change, collaboration between non-government actors and governments—both national and local—is imperative. This constructive collaboration fosters greater synergies, the co-creation and implementation of effective policies, shifts in social norms, and organisational changes that collectively propel societies towards greater equality and inclusivity. Such collaboration is also vital in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly those focused on gender equality (SDG 5), quality education (SDG 4), and reduced inequalities (SDG 10).

The Role of Social Development Direct (SDDirect) in GESI-related systems change

At SDDirect, we currently deliver GESI technical support to two large, UK FCDO-funded long-term projects where our focus is on shifting organisational and social paradigms within governing education structures: Partnership for Learning for All ( PLANE ) , in Nigeria (led by DAI) and the Syria Education Programme ( SEP ) in North-West Syria (led by Chemonics) [1] . Drawing on our 25 years of experience in the delivery of GESI and organisational change, we approach this work with a long-term view, encouraging progressive and sustainable change. We support government-led initiatives and meet individual staff members within the various branches of the MoE where they are currently at in their GESI journey. We then guide individuals towards GESI-transformative education policies, practices and procedures whilst also seeking to transform GESI-related social norms. This approach acknowledges that change is a slow process and acknowledges that policy implementation is only half of the story of sustainable: ‘stronger, bolder, better education.’

Key Levers of Change

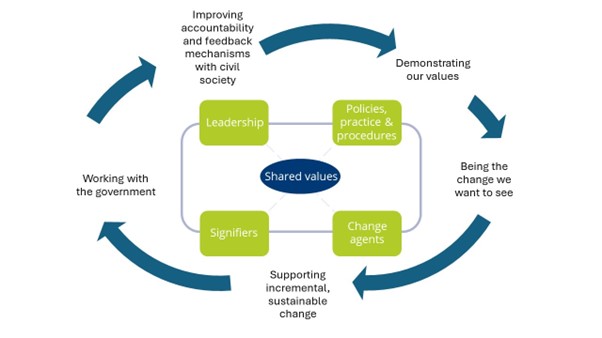

To effectively promote gender equality and social inclusion within government structures and education institutions (inclusive of safe and equitable access to education and disability-inclusive education), it is imperative to foster a positive organisational culture and to change harmful social norms among individuals working within those organisations. Several key levers are pivotal in shaping a safe, inclusive, and gender-responsive culture, each playing a distinct and vital role:

- Shared Values: Establishing and upholding organisational values that prioritise safety, empowerment, and accountability is essential. These shared values serve to unify staff and guide decision-making processes, fostering an environment where individuals feel safe and empowered to challenge unacceptable behaviour and practices.

- Leadership: Effective leadership is paramount in championing ethical and inclusive behaviours and practices. Leaders within government structures and educational institutions must actively promote accountability and shared ownership in upholding organisational values. Their role is pivotal in driving cultural change and fostering a collective commitment to GESI principles.

- Policies, Practices & Procedures: Clear and comprehensive policies, practices, and procedures are indispensable in outlining the implementation of meaningful changes. These frameworks ensure that all staff members understand their responsibilities in creating a safe, inclusive and gender-responsive education system.

- Change Agents: Small groups of dedicated individuals can serve as catalysts for significant and sustainable change within organisations and systems. These change agents, whether formal or informal, unite around shared beliefs and advocate for behaviours and actions that promote organisational and systemic transformation.

- Signifiers: Visible reminders and regular engagement opportunities are crucial for embedding safe, inclusive and gender-responsive practices across all levels of the organisation and system. Signifiers, such as training sessions, awareness campaigns, and accessible reporting mechanisms, serve to reinforce the importance of our objectives and empower staff to adopt proactive behaviours that uphold organisational values.

By leveraging these levers and actively cultivating a transformative culture, government structures and educational institutions can drive meaningful change in policy, practice, and procedure, thereby fostering greater safety, inclusivity and equity within the education system.

Figure 1: SDDirect’s approach to influencing social norms within the education system

Methods to Influence Key Levers:

In order to influence the key levers discussed above and shown in Figure 1, SDDirect applies the following inter-linked methods and approaches:

- Demonstrating Commitment to Values and ‘ Being the Change we Want to See :’

We firmly believe in embodying the principles we advocate, both within our team and in our engagement with government and education stakeholders. We are dedicated to exemplifying the objectives we are working towards as a program, starting with ensuring equal and fair representation of women, men, and people with disabilities within ours and our partners.

We empower our team members to develop their knowledge, attitudes, skills, and behaviours, including through values clarification exercises. This enables them to confidently address issues of inclusion, disability, and safeguarding within our program and in their interactions with stakeholders.

As part of our commitment to inclusivity, we establish tools and platforms that foster inclusive discussions on how best to achieve our objectives. For example, we actively challenge biases when making decisions for the PLANE program, ensuring that our actions align with our values of equity and inclusivity.

Every member of our team is encouraged to openly discuss and reflect on our impact in addressing the challenges of inclusion, gender equality, social inclusion, disability rights, and safeguarding in the education system. Each output of our programme actively seeks ways to communicate proactively about these critical issues.

We identify effective strategies for delivering inclusive education and leverage evidence to advocate for the scaling up of our program activities. Safety is paramount in all our endeavours, and we continuously assess and enhance the safety measures in our activities.

- Collaborating with Government for Incremental, Sustainable Change:

Recognizing the importance of incremental progress, we work closely with government entities to support sustainable change within the education system. While we prioritise building a strong foundation for inclusion, we remain vigilant against behaviours that perpetuate exclusion.

Our engagement with the government is guided by ethical principles, ensuring the protection of our counterparts, stakeholders, and students. We actively support disruptors within and outside the education system who champion positive change and challenge the status quo.

To maintain accountability and uphold high standards, each output lead takes ownership of implementing minimum standards, which are reviewed annually to ensure effectiveness and relevance.

- Enhancing Accountability and Feedback Mechanisms with Civil Society:

We actively seek to strengthen the engagement of citizens and civil society organisations with government to promote inclusive plans, processes, and policies. Recognizing the influential role of civil society in the education sector, we prioritize feedback mechanisms and accountability measures to ensure transparency and responsiveness to community needs.

Case Study: Nigeria and North-West Syria

Using this approach has led to transformative and sustainable changes in Nigeria, where we have supported the government in conducting GESI and Safeguarding analyses of policies, worked with government agencies at the local level to support training and mentorship, and collaborated with schools to implement action plans for increased safeguards. This approach has led to requests for more support and ultimately to more transformative GESI and safeguarding work from the Government, with actors within the government seeing the PLANE team as allies and supporters of their work. We hope to replicate this approach in North-West Syria in collaboration with our SEP consortium partners.

For international development and humanitarian actors, working in collaboration with national and local governments is not just beneficial—it is essential for achieving sustainable and transformative change in gender equality and social inclusion as well as in other areas of education.

By combining resources, expertise, and political will, these partnerships can develop and implement effective policies, shift social norms, and create inclusive organisational cultures. For policymakers and education specialists, embracing collaboration is key to fostering environments where all individuals, regardless of gender or social status, can thrive and contribute to their societies. This is how we answer the Education World Forum’s overarching question. This is how we facilitate stronger, bolder, better education, that is safe, equitable and, importantly, sustainable.

In the pursuit of a more just and equitable world, the importance of such collaborative efforts cannot be overstated. As we move forward, let us prioritise and strengthen these partnerships to ensure that no one is left behind in the march towards gender equality and social inclusion, fulfilling the promise of the Sustainable Development Goals.

[1] In North-west Syria, the SEP project works with the Education Directorates, a governing actor within the education system.

Civil service diversity jobs are superficial, patronising and wasting taxpayers’ money

Esther McVey’s ‘common sense’ measures are long overdue, but welcome nonetheless for countering the woke measures swamping the public sector

It’s hard to keep a straight face when reading the words “common sense minister” in a headline. Are we really at a point where cabinet ministers are needed to represent and enforce basic, positive, human attributes? Have we lost sight of those attributes to such an extent that we need a physical embodiment, Mr. Men-style, for things like “logic”, “integrity”, and “resilience”?

The answer, sadly, is a resounding “yes”, and yesterday “common sense minister” Esther McVey took a major step in delivering on the promise she made six months ago – when the veteran Tory MP was given the unofficial title in Rishi Sunak’s cabinet reshuffle and vowed to “ensure all parts of the public sector embrace common sense instead of political correctness.” Yesterday, McVey took aim at the flabbiest, feeblest and least common-sensical of those public sectors: the civil service .

Over the past decade the supposedly impartial body that describes its core values as “honesty, integrity, impartiality and objectivity” and its core aims as “setting direction”, “engaging people” and “delivering results” has become a shell of its former self, so focused on empty woke ideologies and evangelism that it seems to have forgotten who it is there to serve, let alone the results it exists to deliver.

Enough. In her speech on Monday, McVey announced a ban on the civil service jobs dedicated to diversity, equality and inclusion (DEI) and an end to the money wasted on “woke hobby horses” , warning that the public sector must not become a “pointless job creation scheme for the politically correct.”

That ship has sailed – although better late than never and we can still turn it around. We’re talking about a sector that employs an estimated 10,000 diversity officials with an average salary of £42,000, putting the annual cost of those evangelicals alone at £557 million. But if you were looking to join, say, a “Menopause Network”, a “ Vegan and Vegetarian Network ”, or a “Cross-Government Introverts Network”, the civil service was the place to go.

If you wanted to spend your days immersed in “gender pay audits”, “unconscious bias training courses” and “equality impact assessments”, you’d come to the right place. And how gratifying it must be to have such lofty focal points? After all, who wants to get bogged down with benefits and pensions or the running of employment services and prisons when you could be spending public money on defending the rights of vegan chocolate and building “a supportive community” that helps bring introverts out of themselves?

Detailing how new guidance on third-party expenditure also means that officials will be banned from spending their department’s budget on external DEI campaign groups, experts or consultants, McVey made two crucially important points. First, that the benefits of these endless DEI campaigns, programmes and incentives are “unproven to say the least”. Which hasn’t mattered until now, because it’s all about optics. And second, that “diversity in the Civil Service should never just be measured in terms of race and sex.” That it’s not enough, again, to be seen to do the right thing, if you’re not actually doing the right thing.

This goes for every public sector. Because if you’re filling positions according to a quota defined by a person’s race or sex, you’re ironically proving yourself to be guilty of every ism. When “it should also be about background and differences of opinion and perspective,” says McVey, adding: “Above all it should be about merit.”

A classic example of where this patronising and reductive brand of groupthink gets us is the reaction to Zadie Smith’s New Yorker essay, published last week. In it, the writer praised the “brave students” demanding Israel ends its military attacks on Gaza at Columbia University but made the grievous error of stating that Jewish students should not be made to feel unsafe on university campuses. Cue the Twitter/X backlash, much of which either covertly or overtly seems to be saying that Smith had, as one Times columnist put it yesterday, “betrayed her racial identity.” By saying her opinions are only valid if they cohere with those of other people “like her”, she is being reduced from an intelligent voice to an emblem of her race.

The parallels are clear. Where diversity of any form becomes tokenistic, where it takes the focus off the matter at hand and places it firmly on ideological groupthink, it has zero value. It’s a waste of breath, space, energy – and in the case of the civil service, hard-earned taxpayers’ cash. Time to bring back common sense. I think we’ll all find that a little goes a long way.

- Civil service,

- Esther McVey,

- Gender equality

- Facebook Icon

- WhatsApp Icon

Cookies on GOV.UK

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We’d like to set additional cookies to understand how you use GOV.UK, remember your settings and improve government services.

We also use cookies set by other sites to help us deliver content from their services.

You have accepted additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

You have rejected additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

- International

- Foreign affairs

- Gender, equality, disability and social inclusion analyses in Latin America and the Caribbean: invitation for expressions of interest

- Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office

Latin America and Caribbean gender, equality, disability and social inclusion (GEDSI) analysis: draw-down service

Published 15 May 2024

© Crown copyright 2024

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] .

Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/gender-equality-disability-and-social-inclusion-analyses-in-latin-america-and-the-caribbean-invitation-for-expressions-of-interest/latin-america-and-caribbean-gender-equality-disability-and-social-inclusion-gedsi-analysis-draw-down-service

The Latin America Gender and Equalities Charter includes a commitment for all UK missions to conduct GEDSI analysis by 2025.

The objective is to strengthen the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office’s ( FCDO ) understanding of the equality dynamics in the region, so we can better identify opportunities to deliver on the UK’s equality priorities.

The purpose of this commission is to produce a responsive, expert, and experienced draw-down service to offer research for eligible UK embassies and consulates in Latin America and the Caribbean.

This service is intended to provide research from end-to-end. From developing a concept, delivering the research, sharing recommendations and findings, and supporting actions.

The budget for this contract is £200,000. This will cover 4 to 6 pieces of analysis.

Thematic and methodological experience

The FCDO is looking for teams of suppliers who have:

expertise in gender studies or related disciplines in the social sciences. At least one member of the supplier team must possess a postgraduate degree in a related discipline

demonstrable experience of delivering projects in the gender space. It is desirable that they also have a track record of working in Latin America and/or Caribbean

a sound ability to conduct desk-based and field research

native or near native written comprehension in Spanish and English and be able to communicate verbally and in writing to a professional level.

How to apply

Completed expressions of interest (EOIs) templates should be emailed to [email protected] by 4pm BST on 31 May 2024. Late submissions may not be considered.

You should include all relevant information, including:

- email address

- position / job title

- organisation name

- department name (if applicable)

We will send by 3 June 2024 full terms of reference (ToRs) to suppliers who submit an EOI . The deadline to submit a full proposal is 1 July 2024.

If you have any questions or need clarification on this EOI submission process, email [email protected] .

Is this page useful?

- Yes this page is useful

- No this page is not useful

Help us improve GOV.UK

Don’t include personal or financial information like your National Insurance number or credit card details.

To help us improve GOV.UK, we’d like to know more about your visit today. Please fill in this survey (opens in a new tab) .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

By Helen Longlands Gender equality in education is a matter of social justice, concerned with rights, opportunities and freedoms. Gender equality in education is crucial for sustainable development, for peaceful societies and for individual wellbeing. At local, national and global levels, gender equality in education remains a priority area for governments, civil society and multilateral ...

Calling girls "sweetie" or boys "mate" in primary school perpetuates gender stereotypes, campaigners say. In a letter to the education secretary in England, various groups are calling on the ...

Education is a human right that supports other rights. It is essential for gender equality, lasting poverty reduction, and building prosperous, resilient economies and peaceful, stable societies.

Details. Interventions to enhance girls' education and gender equality: a rigorous review of literature by Unterhalter, E et al (2014). Published 2 July 2014.

Article 14 of the Istanbul Convention, on education, states that signatories should include teaching materials on gender equality and non-stereotyped gender roles. 45 The Government's refreshed Violence Against Women and Girls Strategy prioritised prevention and acknowledged that educational interventions were effective at changing attitudes ...

This study provides an overview of the current status of gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls in the UK in relation to the global commitments to achieving the UN's Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. The report focuses on the UK's successes as well as gaps and priorities for further action in five key areas: participation ...

Gender stereotypes are often an unconscious notion, which can unjustly confine individuals' pathways to that of those deemed acceptable in society. ... Gender Stereotypes in the UK Primary Schools: Student and Teacher Perceptions. ... Gender stereotypes in education: Development, consequences, and interventions. European Journal of ...

The diagram below sets out the understanding that girls' education and gender equality are affected by processes within and beyond schools. The development and implementation of interventions to improve girls' schooling and enhance gender equality are affected by aspects of context at local, national and global levels.

The government has published Gender equality at every stage: a roadmap for change, setting out the vision and actions to tackle the persistent gendered inequalities women and men face across their ...

Report: Gender Equality in Higher Education - Maximising Impacts. On 10 March 2022, we launched a report exploring the gender equality challenges in higher education across the world, and strategies for positive change. Read the report and watch the recording of our launch event below.

Additionally, the latest ONS data on suicides in England and Wales found that between 2010 and 2021, suicide rates had increased amongst females in the following age groups: 10 to 24 years: 2.1 to 2.5 per 100,000 females. 25 to 44 years: 4.7 to 5.7 per 100,000 females. 45 to 64 years: 5.9 to 6.4 per 100,000 females.

Another inequality issue within the British education system is the difference in levels of men and women who are employed as teaching and support staff. Just 15% of primary school teachers are male, meaning that many children are lacking a positive male role model within their educational framework. Some schools do not have any male staff ...

Female university graduates have bigger Hecs debts but earning less than men, research reveals. Average student debt balance has risen 10% and taking longer to pay off, affecting major life events ...

Higher education institutions are important for gender equality 6 Higher education can perpetuate gender inequalities 7 Intersectionality 7 Legal and policy frameworks 7 ... contribution to addressing challenges of gender inequality both in the UK and around the world. Maddalaine Ansell Director of Education Gillian Cowell Head, Gender and ...

This is non-statutory advice from the Department for Education. It has been produced to help schools to understand how the Equality Act affects them and how to fulfil their duties under the Act. It has been updated to include information on same-sex marriage. On 1 October 2010, the Equality Act 2010 replaced all existing equality legislation such

Introduction. Girls' education and gender inequalities associated with education were areas of major policy attention before the COVID-19 pandemic, and remain central to the agendas of governments, multilateral organisations and international NGOs in thinking about agendas to build back better, more equal or to build forward (Save the Children Citation 2020; UN Women Citation 2021; UNESCO ...

Equalities in policymaking and delivery. Equality and diversity are critical to delivering DfE 's vision: we enable children and learners to thrive by protecting the vulnerable and ensuring the ...

A&P Plans set out the actions providers are taking to increase access to, success in, and progression from higher education by students from disadvantaged and under-represented groups. Planned spending on A&P Plans from 2020/21 to 2024/25 is to increase from just over £550 million to around £565 million.

However, our new comprehensive study, published as part of the Institute for Fiscal Studies Deaton Review of Inequalities, shows that education in the UK is not tackling inequality. Instead, children from poorer backgrounds do worse throughout the education system. The report assesses existing evidence using a range of different datasets.

The low share of women in top positions certainly contributes to the overall gender pay gap in the United Kingdom, which stood at 14.9 percent for all workers in 2022, and 8.3 percent for full ...

2. KEY FACTORS IN EXPLAINING GENDER PARITY IN ENROLMENTS AND PERFORMANCE Market Related Factors The transformation in girls' education in the UK is the result of a considerable range of factors, not least the efforts of gender equality reformers and government and school policy makers committed to improving female education.

Education, Relationships and Sex Education and Health Education (England) Regulations 2019, made under sections 34 and 35 of the Children and Social Work Act 2017, make relationships education compulsory for all pupils receiving primary education and relationships and sex education (RSE) compulsory for all pupils receiving secondary

Government sources told BBC News about plans to ban sex education for under-nines, as well as teaching about gender identity, on Wednesday.

The Importance of Non-Government and Government Collaborative Efforts to advance Equal Education: Enhancing Gender Equality and Social Inclusion With the Education World Forum taking place next week in London, 120 Ministers from 114 countries will come together to try to answer the forum's…

It may be that traditional attitudes to gender roles, lower perceived benefits of daughters' relative to sons' education, and threats to respectability and modesty expressed by parents in ...

The new guidance could also see English schools banned from introducing any sex education materials to children before school year 5, when pupils turn nine. Britain's Conservative government has increasingly leaned into the debate around gender, and previously ordered English schools to inform parents if their children want to transition gender.

Women and girls at the centre of FCDO 's operations, and investment. commit to at least 80% of FCDO 's bilateral aid programmes having a focus on gender equality by 2030 (using OECD DAC ...

If you wanted to spend your days immersed in "gender pay audits", "unconscious bias training courses" and "equality impact assessments", you'd come to the right place.

The Latin America Gender and Equalities Charter includes a commitment for all UK missions to conduct GEDSI analysis by 2025.. The objective is to strengthen the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development ...