- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Three Branches of Government

By: History.com Editors

Updated: September 4, 2019 | Original: November 17, 2017

The three branches of the U.S. government are the legislative, executive and judicial branches. According to the doctrine of separation of powers, the U.S. Constitution distributed the power of the federal government among these three branches, and built a system of checks and balances to ensure that no one branch could become too powerful.

Separation of Powers

The Enlightenment philosopher Montesquieu coined the phrase “trias politica,” or separation of powers, in his influential 18th-century work “Spirit of the Laws.” His concept of a government divided into legislative, executive and judicial branches acting independently of each other inspired the framers of the U.S. Constitution , who vehemently opposed concentrating too much power in any one body of government.

In the Federalist Papers , James Madison wrote of the necessity of the separation of powers to the new nation’s democratic government: “The accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive and judiciary, in the same hands, whether of one, a few, or many, and whether hereditary, self-appointed, or elected, may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny.”

Legislative Branch

According to Article I of the Constitution, the legislative branch (the U.S. Congress) has the primary power to make the country’s laws. This legislative power is divided further into the two chambers, or houses, of Congress: the House of Representatives and the Senate .

Members of Congress are elected by the people of the United States. While each state gets the same number of senators (two) to represent it, the number of representatives for each state is based on the state’s population.

Therefore, while there are 100 senators, there are 435 elected members of the House, plus an additional six non-voting delegates who represent the District of Columbia as well as Puerto Rico and other U.S. territories.

In order to pass an act of legislation, both houses must pass the same version of a bill by majority vote. Once that happens, the bill goes to the president, who can either sign it into law or reject it using the veto power assigned in the Constitution.

In the case of a regular veto, Congress can override the veto by a two-thirds vote of both houses. Both the veto power and Congress’ ability to override a veto are examples of the system of checks and balances intended by the Constitution to prevent any one branch from gaining too much power.

Executive Branch

Article II of the Constitution states that the executive branch , with the president as its head, has the power to enforce or carry out the laws of the nation.

In addition to the president, who is the commander in chief of the armed forces and head of state, the executive branch includes the vice president and the Cabinet; the State Department, Defense Department and 13 other executive departments; and various other federal agencies, commissions and committees.

Unlike members of Congress, the president and vice president are not elected directly by the people every four years, but through the electoral college system. People vote to select a slate of electors, and each elector pledges to cast his or her vote for the candidate who gets the most votes from the people they represent.

In addition to signing (or vetoing) legislation, the president can influence the country’s laws through various executive actions, including executive orders, presidential memoranda and proclamations. The executive branch is also responsible for carrying out the nation’s foreign policy and conducting diplomacy with other countries, though the Senate must ratify any treaties with foreign nations.

Judicial Branch

Article III decreed that the nation’s judicial power, to apply and interpret the laws, should be vested in “one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.”

The Constitution didn’t specify the powers of the Supreme Court or explain how the judicial branch should be organized, and for a time the judiciary took a back seat to the other branches of government.

But that all changed with Marbury v. Madison , an 1803 milestone case that established the Supreme Court’s power of judicial review, by which it determines the constitutionality of executive and legislative acts. Judicial review is another key example of the checks and balances system in action.

Members of the federal judiciary—which includes the Supreme Court, 13 U.S. Courts of Appeals and 94 federal judicial district courts—are nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate. Federal judges hold their seats until they resign, die or are removed from office through impeachment by Congress.

Implied Powers of the Three Branches of Government

In addition to the specific powers of each branch that are enumerated in the Constitution, each branch has claimed certain implied powers, many of which can overlap at times. For example, presidents have claimed exclusive right to make foreign policy, without consultation with Congress.

In turn, Congress has enacted legislation that specifically defines how the law should be administered by the executive branch, while federal courts have interpreted laws in ways that Congress did not intend, drawing accusations of “legislating from the bench.”

The powers granted to Congress by the Constitution expanded greatly after the Supreme Court ruled in the 1819 case McCulloch v. Maryland that the Constitution fails to spell out every power granted to Congress.

Since then, the legislative branch has often assumed additional implied powers under the “necessary and proper clause” or “elastic clause” included in Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution.

Checks and Balances

“In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty is this: You must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place, oblige it to control itself,” James Madison wrote in the Federalist Papers . To ensure that all three branches of government remain in balance, each branch has powers that can be checked by the other two branches. Here are ways that the executive, judiciary, and legislative branches keep one another in line:

· The president (head of the executive branch) serves as commander in chief of the military forces, but Congress (legislative branch) appropriates funds for the military and votes to declare war. In addition, the Senate must ratify any peace treaties.

· Congress has the power of the purse, as it controls the money used to fund any executive actions.

· The president nominates federal officials, but the Senate confirms those nominations.

· Within the legislative branch, each house of Congress serves as a check on possible abuses of power by the other. Both the House of Representatives and the Senate have to pass a bill in the same form for it to become law.

· Once Congress has passed a bill, the president has the power to veto that bill. In turn, Congress can override a regular presidential veto by a two-thirds vote of both houses.

· The Supreme Court and other federal courts (judicial branch) can declare laws or presidential actions unconstitutional, in a process known as judicial review.

· In turn, the president checks the judiciary through the power of appointment, which can be used to change the direction of the federal courts

· By passing amendments to the Constitution, Congress can effectively check the decisions of the Supreme Court.

· Congress can impeach both members of the executive and judicial branches.

Separation of Powers, The Oxford Guide to the United States Government . Branches of Government, USA.gov . Separation of Powers: An Overview, National Conference of State Legislatures .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Introductory essay

Written by the educators who created Cyber-Influence and Power, a brief look at the key facts, tough questions and big ideas in their field. Begin this TED Study with a fascinating read that gives context and clarity to the material.

Each and every one of us has a vital part to play in building the kind of world in which government and technology serve the world’s people and not the other way around. Rebecca MacKinnon

Over the past 20 years, information and communication technologies (ICTs) have transformed the globe, facilitating the international economic, political, and cultural connections and exchanges that are at the heart of contemporary globalization processes. The term ICT is broad in scope, encompassing both the technological infrastructure and products that facilitate the collection, storage, manipulation, and distribution of information in a variety of formats.

While there are many definitions of globalization, most would agree that the term refers to a variety of complex social processes that facilitate worldwide economic, cultural, and political connections and exchanges. The kinds of global connections ICTs give rise to mark a dramatic departure from the face-to-face, time and place dependent interactions that characterized communication throughout most of human history. ICTs have extended human interaction and increased our interconnectedness, making it possible for geographically dispersed people not only to share information at an ever-faster rate but also to organize and to take action in response to events occurring in places far from where they are physically situated.

While these complex webs of connections can facilitate positive collective action, they can also put us at risk. As TED speaker Ian Goldin observes, the complexity of our global connections creates a built-in fragility: What happens in one part of the world can very quickly affect everyone, everywhere.

The proliferation of ICTs and the new webs of social connections they engender have had profound political implications for governments, citizens, and non-state actors alike. Each of the TEDTalks featured in this course explore some of these implications, highlighting the connections and tensions between technology and politics. Some speakers focus primarily on how anti-authoritarian protesters use technology to convene and organize supporters, while others expose how authoritarian governments use technology to manipulate and control individuals and groups. When viewed together as a unit, the contrasting voices reveal that technology is a contested site through which political power is both exercised and resisted.

Technology as liberator

The liberating potential of technology is a powerful theme taken up by several TED speakers in Cyber-Influence and Power . Journalist and Global Voices co-founder Rebecca MacKinnon, for example, begins her talk by playing the famous Orwell-inspired Apple advertisement from 1984. Apple created the ad to introduce Macintosh computers, but MacKinnon describes Apple's underlying narrative as follows: "technology created by innovative companies will set us all free." While MacKinnon examines this narrative with a critical eye, other TED speakers focus on the ways that ICTs can and do function positively as tools of social change, enabling citizens to challenge oppressive governments.

In a 2011 CNN interview, Egyptian protest leader, Google executive, and TED speaker Wael Ghonim claimed "if you want to free a society, just give them internet access. The young crowds are going to all go out and see and hear the unbiased media, see the truth about other nations and their own nation, and they are going to be able to communicate and collaborate together." (i). In this framework, the opportunities for global information sharing, borderless communication, and collaboration that ICTs make possible encourage the spread of democracy. As Ghonim argues, when citizens go online, they are likely to discover that their particular government's perspective is only one among many. Activists like Ghonim maintain that exposure to this online free exchange of ideas will make people less likely to accept government propaganda and more likely to challenge oppressive regimes.

A case in point is the controversy that erupted around Khaled Said, a young Egyptian man who died after being arrested by Egyptian police. The police claimed that Said suffocated when he attempted to swallow a bag of hashish; witnesses, however, reported that he was beaten to death by the police. Stories about the beating and photos of Said's disfigured body circulated widely in online communities, and Ghonim's Facebook group, titled "We are all Khaled Said," is widely credited with bringing attention to Said's death and fomenting the discontent that ultimately erupted in the 2011 Egyptian Revolution, or what Ghonim refers to as "revolution 2.0."

Ghonim's Facebook group also illustrates how ICTs enable citizens to produce and broadcast information themselves. Many people already take for granted the ability to capture images and video via handheld devices and then upload that footage to platforms like YouTube. As TED speaker Clay Shirky points out, our ability to produce and widely distribute information constitutes a revolutionary change in media production and consumption patterns. The production of media has typically been very expensive and thus out of reach for most individuals; the average person was therefore primarily a consumer of media, reading books, listening to the radio, watching TV, going to movies, etc. Very few could independently publish their own books or create and distribute their own radio programs, television shows, or movies. ICTs have disrupted this configuration, putting media production in the hands of individual amateurs on a budget — or what Shirky refers to as members of "the former audience" — alongside the professionals backed by multi-billion dollar corporations. This "democratization of media" allows individuals to create massive amounts of information in a variety of formats and to distribute it almost instantly to a potentially global audience.

Shirky is especially interested in the Internet as "the first medium in history that has native support for groups and conversations at the same time." This shift has important political implications. For example, in 2008 many Obama followers used Obama's own social networking site to express their unhappiness when the presidential candidate changed his position on the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. The outcry of his supporters did not force Obama to revert to his original position, but it did help him realize that he needed to address his supporters directly, acknowledging their disagreement on the issue and explaining his position. Shirky observes that this scenario was also notable because the Obama organization realized that "their role was to convene their supporters but not to control their supporters." This tension between the use of technology in the service of the democratic impulse to convene citizens vs. the authoritarian impulse to control them runs throughout many of the TEDTalks in Cyber-Influence and Power.

A number of TED speakers explicitly examine the ways that ICTs give individual citizens the ability to document governmental abuses they witness and to upload this information to the Internet for a global audience. Thus, ICTs can empower citizens by giving them tools that can help keep their governments accountable. The former head of Al Jazeera and TED speaker Wadah Khanfar provides some very clear examples of the political power of technology in the hands of citizens. He describes how the revolution in Tunisia was delivered to the world via cell phones, cameras, and social media outlets, with the mainstream media relying on "citizen reporters" for details.

Former British prime minister Gordon Brown's TEDTalk also highlights some of the ways citizens have used ICTs to keep their governments accountable. For example, Brown recounts how citizens in Zimbabwe used the cameras on their phones at polling places in order to discourage the Mugabe regime from engaging in electoral fraud. Similarly, Clay Shirky begins his TEDTalk with a discussion of how cameras on phones were used to combat voter suppression in the 2008 presidential election in the U.S. ICTs allowed citizens to be protectors of the democratic process, casting their individual votes but also, as Shirky observes, helping to "ensure the sanctity of the vote overall."

Technology as oppressor

While smart phones and social networking sites like Twitter and Facebook have arguably facilitated the overthrow of dictatorships in places like Tunisia and Egypt, lending credence to Gordon Brown's vision of technology as an engine of liberalism and pluralism, not everyone shares this view. As TED speaker and former religious extremist Maajid Nawaz points out, there is nothing inherently liberating about ICTs, given that they frequently are deployed to great effect by extremist organizations seeking social changes that are often inconsistent with democracy and human rights. Where once individual extremists might have felt isolated and alone, disconnected from like-minded people and thus unable to act in concert with others to pursue their agendas, ICTs allow them to connect with other extremists and to form communities around their ideas, narratives, and symbols.

Ian Goldin shares this concern, warning listeners about what he calls the "two Achilles heels of globalization": growing inequality and the fragility that is inherent in a complex integrated system. He points out that those who do not experience the benefits of globalization, who feel like they've been left out in one way or another, can potentially become incredibly dangerous. In a world where what happens in one place very quickly affects everyone else — and where technologies are getting ever smaller and more powerful — a single angry individual with access to technological resources has the potential to do more damage than ever before. The question becomes then, how do we manage the systemic risk inherent in today's technology-infused globalized world? According to Goldin, our current governance structures are "fossilized" and ill-equipped to deal with these issues.

Other critics of the notion that ICTs are inherently liberating point out that ICTs have been leveraged effectively by oppressive governments to solidify their own power and to manipulate, spy upon, and censor their citizens. Journalist and TED speaker Evgeny Morozov expresses scepticism about what he calls "iPod liberalism," or the belief that technology will necessarily lead to the fall of dictatorships and the emergence of democratic governments. Morozov uses the term "spinternet" to describe authoritarian governments' use of the Internet to provide their own "spin" on issues and events. Russia, China, and Iran, he argues, have all trained and paid bloggers to promote their ideological agendas in the online environment and/or or to attack people writing posts the government doesn't like in an effort to discredit them as spies or criminals who should not be trusted.

Morozov also points out that social networking sites like Facebook and Twitter are tools not only of revolutionaries but also of authoritarian governments who use them to gather open-source intelligence. "In the past," Morozov maintains, "it would take you weeks, if not months, to identify how Iranian activists connect to each other. Now you know how they connect to each other by looking at their Facebook page. KGB...used to torture in order to get this data." Instead of focusing primarily on bringing Internet access and devices to the people in countries ruled by authoritarian regimes, Morozov argues that we need to abandon our cyber-utopian assumptions and do more to actually empower intellectuals, dissidents, NGOs and other members of society, making sure that the "spinternet" does not prevent their voices from being heard.

The ICT Empowered Individual vs. The Nation State

In her TEDTalk "Let's Take Back the Internet," Rebecca MacKinnon argues that "the only legitimate purpose of government is to serve citizens, and…the only legitimate purpose of technology is to improve our lives, not to manipulate or enslave us." It is clearly not a given, however, that governments, organizations, and individuals will use technology benevolently. Part of the responsibility of citizenship in the globalized information age then is to work to ensure that both governments and technologies "serve the world's peoples." However, there is considerable disagreement about what that might look like.

WikiLeaks spokesperson and TED speaker Julian Assange, for example, argues that government secrecy is inconsistent with democratic values and is ultimately about deceiving and manipulating rather than serving the world's people. Others maintain that governments need to be able to keep secrets about some topics in order to protect their citizens or to act effectively in response to crises, oppressive regimes, terrorist organizations, etc. While some view Assange's use of technology as a way to hold governments accountable and to increase transparency, others see this use of technology as a criminal act with the potential to both undermine stable democracies and put innocent lives in danger.

ICTs and global citizenship

While there are no easy answers to the global political questions raised by the proliferation of ICTs, there are relatively new approaches to the questions that look promising, including the emergence of individuals who see themselves as global citizens — people who participate in a global civil society that transcends national boundaries. Technology facilitates global citizens' ability to learn about global issues, to connect with others who care about similar issues, and to organize and act meaningfully in response. However, global citizens are also aware that technology in and of itself is no panacea, and that it can be used to manipulate and oppress.

Global citizens fight against oppressive uses of technology, often with technology. Technology helps them not only to participate in global conversations that affect us all but also to amplify the voices of those who have been marginalized or altogether missing from such conversations. Moreover, global citizens are those who are willing to grapple with large and complex issues that are truly global in scope and who attempt to chart a course forward that benefits all people, regardless of their locations around the globe.

Gordon Brown implicitly alludes to the importance of global citizenship when he states that we need a global ethic of fairness and responsibility to inform global problem-solving. Human rights, disease, development, security, terrorism, climate change, and poverty are among the issues that cannot be addressed successfully by any one nation alone. Individual actors (nation states, NGOs, etc.) can help, but a collective of actors, both state and non-state, is required. Brown suggests that we must combine the power of a global ethic with the power to communicate and organize globally in order for us to address effectively the world's most pressing issues.

Individuals and groups today are able to exert influence that is disproportionate to their numbers and the size of their arsenals through their use of "soft power" techniques, as TED speakers Joseph Nye and Shashi Tharoor observe. This is consistent with Maajid Nawaz's discussion of the power of symbols and narratives. Small groups can develop powerful narratives that help shape the views and actions of people around the world. While governments are far more accustomed to exerting power through military force, they might achieve their interests more effectively by implementing soft power strategies designed to convince others that they want the same things. According to Nye, replacing a "zero-sum" approach (you must lose in order for me to win) with a "positive-sum" one (we can both win) creates opportunities for collaboration, which is necessary if we are to begin to deal with problems that are global in scope.

Let's get started

Collectively, the TEDTalks in this course explore how ICTs are used by and against governments, citizens, activists, revolutionaries, extremists, and other political actors in efforts both to preserve and disrupt the status quo. They highlight the ways that ICTs have opened up new forms of communication and activism as well as how the much-hailed revolutionary power of ICTs can and has been co-opted by oppressive regimes to reassert their control.

By listening to the contrasting voices of this diverse group of TED speakers, which includes activists, journalists, professors, politicians, and a former member of an extremist organization, we can begin to develop a more nuanced understanding of the ways that technology can be used both to facilitate and contest a wide variety of political movements. Global citizens who champion democracy would do well to explore these intersections among politics and technology, as understanding these connections is a necessary first step toward MacKinnon's laudable goal of building a world in which "government and technology serve the world's people and not the other way around."

Let's begin our exploration of the intersections among politics and technology in today's globalized world with a TEDTalk from Ian Goldin, the first Director of the 21st Century School, Oxford University's think tank/research center. Goldin's talk will set the stage for us, exploring the integrated, complex, and technology rich global landscape upon which the political struggles for power examined by other TED speakers play out.

Navigating our global future

i. "Welcome to Revolution 2.0, Ghonim Says," CNN, February 9, 2011. http://www.cnn.com/video/?/video/world/2011/02/09/wael.ghonim.interview.cnn .

Relevant talks

Gordon Brown

Wiring a web for global good.

Clay Shirky

How social media can make history.

Wael Ghonim

Inside the egyptian revolution.

Wadah Khanfar

A historic moment in the arab world.

Evgeny Morozov

How the net aids dictatorships.

Maajid Nawaz

A global culture to fight extremism.

Rebecca MacKinnon

Let's take back the internet.

Julian Assange

Why the world needs wikileaks.

Global power shifts

Shashi Tharoor

Why nations should pursue soft power.

13.1 Contemporary Government Regimes: Power, Legitimacy, and Authority

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the nature of governing regimes.

- Define power, authority, and legitimacy.

- Explain the relationships among power, authority, and legitimacy.

- Discuss political history and contemporary political and legal developments surrounding governing regimes.

A government can be defined as a set of organizations, with their associated rules and procedures, that has the authority to exercise the widest scope of power —the ability to impose its will on others to secure desired outcomes—over a defined area. Government authority includes the power to have the final say over when the use of force is acceptable, and governments seek to exercise their authority with legitimacy. This is a complex definition, so this section unpacks its elements one by one.

A government both claims the right and has the ability to exercise power over all people in a defined geographic area. The leadership of a church or a mosque, for example, can refuse to offer religious services to certain individuals or can excommunicate them. However, such organizations have no right to apply force to impose their will on non-congregants. In contrast, governments reserve for themselves the broadest scope of rightful power within their area of control and can, in principle, impose their will on vast areas of the lives of all people within the territories over which they rule. During the COVID-19 pandemic, only governments both claimed and exercised the right to close businesses and to forbid religious institutions to hold services. The pandemic also highlights another feature of governments: almost all governments seek to have and to exercise power in order to create at least minimal levels of peace, order, and collective stability and safety.

As German social scientist Max Weber maintained, almost all governments seek to have and to enforce the right to have the final say over when violence is acceptable within their territory. Governments often assert what Weber called a monopoly on the right to use violence , reserving for themselves either the right to use violence or the right to approve its use by others. 1 The word monopoly might be misleading. In most countries, citizens have a right to use violence in self-defense; most governments do not maintain that they alone can exercise the acceptable use of violence. Where the government recognizes the right to use violence in self-defense, it will seek to reserve for itself the right to decide when, in its judgment, that use is acceptable.

Imagine a landlord confronting a tenant who has not paid their rent. The landlord cannot violently seize the renter and forcibly evict them from the apartment; only the police—an agency of the state—can acceptably do that. Nevertheless, the law of many countries recognizes a right of self-defense by means of physical violence. In many US states, for example, if a person enters your house unlawfully with a weapon and you suspect they constitute a threat to you or your family, you have a broad right to use force against that intruder in self-defense (a principle that forms the core of the “ castle doctrine ”). In addition, private security guards can sometimes use force to protect private property. The government retains the right to determine, via its court system, whether these uses of force meet the criteria for being judged acceptable. Because the government sets these criteria, it can be said to have the final say on when the use of force is permissible.

Authority is the permission, conferred by the laws of a governing regime, to exercise power. Governments most often seek to authorize their power in the form of some decree or set of decrees—most often in the form of a legal constitution that sets out the scope of the government’s powers and the process by which laws will be made and enforced. The enactment of codes of criminal law, the creation of police forces, and the establishment of procedures surrounding criminal justice are clear examples of the development of authorized power. To some degree, the constitution of every government authorizes the government to impose a prohibition, applicable in principle to all people in its territory, on certain behaviors. Individuals engaging in those behaviors are subject to coercive enforcement by the state’s police force, which adheres to defined lines of authority and the rules police departments must follow.

Governmental regulations are another type of authorized government power. The laws that structure a regime usually give the government the authority to regulate individual and group behaviors. For example, Article 1 Section 8 of the US Constitution authorizes the federal government to regulate interstate commerce. When large commercial airlines fly individuals across state lines for a fee, they engage in interstate commerce. The federal government therefore has the authority to regulate airline safety requirements and flight patterns. Pursuant to this authority, the federal government has established an agency, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), to issue these regulations, which are ultimately backed by the state’s coercive enforcement power.

Weber argued that those who structure regimes are likely to choose, on the basis of the regime’s own best interests, to create authority that is clearly spelled out in a regime’s constitutional law. 2 When lines of authority in the government are clear, especially in the context of the state’s criminal law, the people living in a regime are less fearful of the state. This helps the state secure the people’s support. When the scope of the government’s authority is clear, people can understand how their government is structured and functions and are therefore less likely to be surprised by governmental actions. This can be especially important for the economy. To follow the example above, if laws regulating the private ownership of commercial airlines are constantly open to unexpected change, some people may be wary of working in the industry or investing their money in these companies’ stock. Predictable governmental action can encourage these investments. With increased economic activity, the government can tax the productive output, amassing resources to help it achieve whatever its goals might be. In addition, clearly defined structures of authority in the form of stable bureaucratic institutions allow a government to exercise power more efficiently and cost-effectively, once again enabling it to amass more resources to serve its objectives. 3

The use of physical force to directly restrain behavior is just one of the ways governments exercise power. Governments also tax. In a sense, the taxing authority of government is a necessary corollary of its authority to impose behavior-restricting rules: almost all governments must derive revenue through taxes in order to finance the maintenance of their laws and to ensure peace and public order. However, that authority also allows governments to exercise power to achieve a wide variety of ends, funding everything from foreign wars to a social safety net or a set of social programs. Taxation is another way governments regulate people’s behavior: if you don’t pay your taxes, the government is authorized to punish you—a principle true across the world, even if the levels of enforcement for not paying taxes vary across regimes.

The authority to tax illustrates another aspect of governmental power: the use of authority to shape society by creating incentives for particular kinds of behavior. In the United States, the federal tax code enables taxpayers to deduct large charitable donations from their taxable income as a way to encourage individuals to give to charities. Additionally, homeowners can deduct the interest they pay on their home mortgage, thereby reducing their annual federal tax obligation. This use of government power is meant to encourage people to own homes rather than rent. In the United States, at least, the federal government has encouraged homeownership due to a belief that homeownership helps people build closer ties with and involvement in local communities and thus increases civic participation, and that owning a home correlates with greater levels of long-term savings, which can provide individuals greater financial security in their retirement. 4 (For some people, their house is their largest asset, which can help to finance their retirement.) Conversely, governments can impose “sin taxes”—that is, taxes on products like alcohol and cigarettes, discouraging their use. Some lawmakers have proposed levying higher taxes on bullets to discourage gun violence, and some areas have taxed sugary soft drinks to discourage their consumption as a way to improve public health. 5

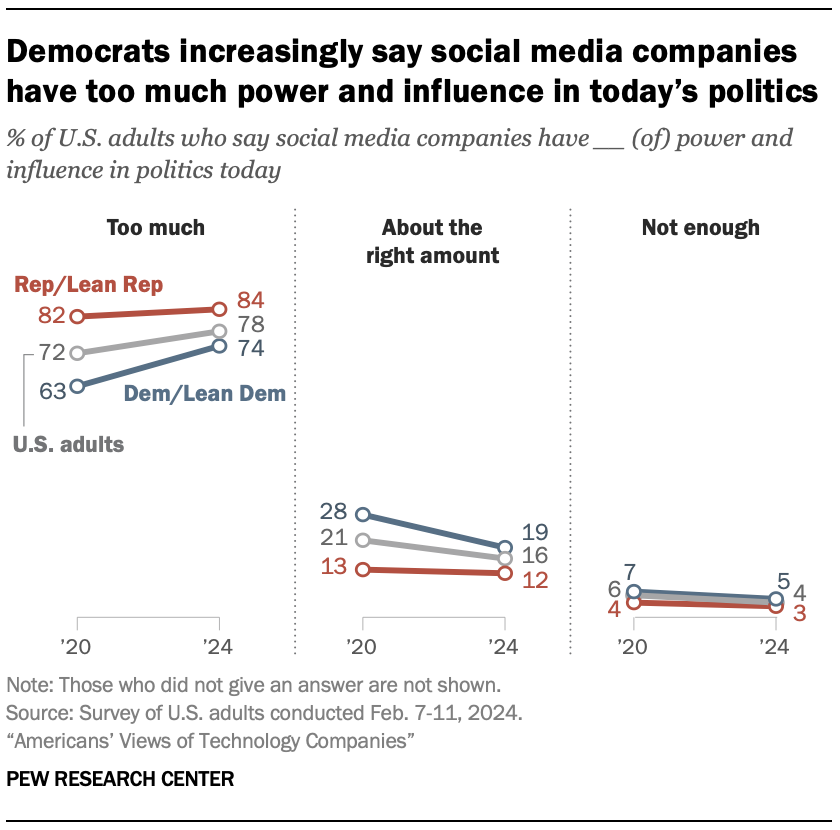

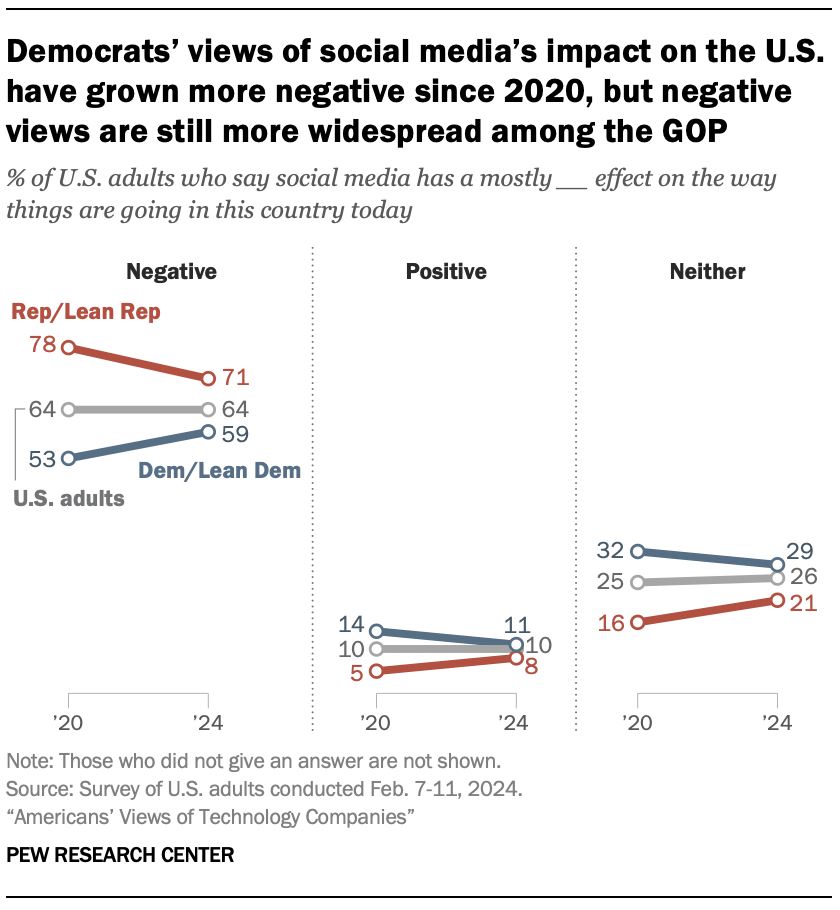

Show Me the Data

Beyond taxation, governmental leaders can use their office to influence public opinion. Governmental authorities are often authorized to use the government’s assets to promote their policies: the president of the United States, for example, is authorized to use Air Force One (the presidential jet) to travel the country in order to promote policy proposals. (Presidents are not, however, allowed to use Air Force One for free to conduct political fundraising.) Additionally, members of the United States Congress are authorized to send letters to constituents, free of charge, describing or defending the policies they support. Tools like these allow governments to exercise the power of influence and persuasion. The chief executive is usually the governmental official who takes the greatest advantage of this form of power. In the United States, presidents such as Teddy Roosevelt became famous for skillfully using the “ bully pulpit ,” that is, the power of the president to shape the opinions of the population and, through this, potentially to influence members of other branches of the government, especially elected legislators.

Presidents and prime ministers often give speeches or issue proclamations to exert this power. President Barack Obama, for example, following a long tradition in American politics, spoke often of what “we as Americans” value as a way to persuade the populace to support the policy agenda of his administration. Take the following example from one of Obama’s speeches. In the speech, he defended his administration’s decision to change the priorities of federal immigration officials to less rigorously enforce laws requiring the deportation of undocumented individuals when those individuals entered the country as children—the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, program. Arguing that children brought to the country by their parents should not have to live in fear of deportation, Obama remarked:

“My fellow Americans, we are and always will be a nation of immigrants. We were strangers once, too. And whether our forebears were strangers who crossed the Atlantic, or the Pacific, or the Rio Grande, we are here only because this country welcomed them in and taught them that to be an American is about something more than what we look like, or what our last names are, or how we worship. What makes us Americans is our shared commitment to an ideal—that all of us are created equal, and all of us have the chance to make of our lives what we will.” (emphasis added) 6

By using rhetoric that attempts to define the national ethos, governments can seek to exercise power by shaping the population’s sense of itself and its place in history.

Most governments establish authority not only to exercise power, but also in the pursuit of legitimacy. Legitimacy can be seen from two different vantage points. Following Weber, the term is often used to mean the widespread belief that the government has the right to exercise its power. In this sense—which can be called broad legitimacy —the concept describes a government trait. Legitimacy can also be seen from the perspective of individuals or groups who make determinations about whether their government is or is not legitimate—that is, rightfully exercising power, or what can be called judgments about legitimacy . In either sense, legitimacy is measured in perceptions of the rightfulness of government actions—the sense that those actions are morally appropriate and consistent with basic justice and social welfare.

It is quite possible for a small group or a small set of groups to conclude that their government is illegitimate and so does not have the right to exercise authorized power even as the vast majority think that government is rightfully exercising authorized power. In this case, since the dissenting group is small and the great majority see their government as legitimate, the state can be deemed broadly legitimate. Broad legitimacy, therefore, is defined not as unanimous agreement by the people that a government’s authority is rightfully exercised, but simply as a broad sentiment that it is.

Finding Legitimacy: What Does Legitimacy Mean to You?

In this Center for Public Impact video, people from around the world talk about what government legitimacy means to them.

Legitimacy is a vague concept. Citizens’ judgments about legitimacy entail the often-difficult determinations of what is or is not rightful and thus consistent with morality, justice, and social welfare. Judging rightfulness can be a challenging task, as can the determination of whether a regime truly possesses broad legitimacy. Though you cannot always say for certain that a government truly has broad legitimacy, broad illegitimacy is often easy to detect. Indications of governments that do not have broad legitimacy can take many forms, including sustained protests, very low levels of trust in the regime as captured by polling data, and widespread calls for revising or abandoning the constitution.

The most effective governments, Weber argued, not only have laws that clearly authorize power but also have some substantial measure of broad legitimacy. Broadly legitimate governments can exercise power without the threat of popular rebellion, and the state can more readily rely on people to follow the law. These conditions can spare the government the cost of large standing police forces or militaries, and those resources in turn can be allocated in other areas. Unsurprisingly, most governments seek to legitimize their rule.

In the United States, many debates over rival understandings of law and public policy are not debates over legitimacy. For example, many groups in the United States disagree over certain tax policies; some want to increase taxes to pay for greater services, while others want to lower taxes to encourage economic growth. Yet those who oppose a particular tax law rarely refer to it as illegitimate since the law is recognized as coming from a process that has widespread popular support—that is, from the lawmaking process authorized in the US Constitution. Therefore, tax laws that many disfavor are usually not seen as illegitimate, but simply as unpopular or unwise and thus in need of change.

However, in the United States today, more and more debates surrounding law, public policy, and election results are expressed in terms of judgments of their legitimacy or illegitimacy. A true loss of legitimacy, either in the eyes of a small group or in the eyes of the broad populace, occurs only when a law is determined to be so wrong or harmful that it is not right for the government to enact it. In many cases in the United States today, allegations of illegitimacy contend not that a law or electoral result lacks legitimacy because the substance of the law or election outcome is so egregious that it is not a rightful thing for the government to do or to permit, but because they claim the US Constitution does not authorize the law or the process that resulted in a particular outcome.

Consider the 2020 election and debates involving the administration of President Joe Biden . Many supporters of Donald Trump hold that President Biden is an illegitimate president, 7 but they contend not so much that he is so unacceptable that his holding the office of president is inconsistent with morality, justice, and social welfare, but that the governmental officials in charge of running the 2020 presidential election process acted inappropriately or even, some contend, engaged in criminal ballot tampering. For these reasons, to them Biden’s current presidency is unrightful because they see the process by which he was elected as unauthorized. 8 Numerous post-election audits have found the allegations to be without merit. 9 In an April 2021 poll, about three-quarters of Republicans, a quarter of Democrats, and half of Independents indicated that they believe the 2020 election was affected by cheating. 10

These debates are complicated, and it is difficult to pinpoint the origin, rationale, and true motivation behind these judgments that the election results, for example, are illegitimate. What can be said is that there seem to be not only deeply rooted disagreements in the United States over what policies are best, but also deep disagreements about whether a variety of laws or governmental actions are in fact authorized by the Constitution—a development arising because of deepening disagreements among citizens about what the Constitution and the rules it contains actually mean.

Some public allegations that a law or electoral outcome is illegitimate in the sense that it is unauthorized may be mere covers for the genuine view that the laws or the electoral results are themselves unrightful, even if they were authorized. Those making such claims may not wish to be seen as protesting authorized governmental activity since to do so could make them appear lawless or even revolutionary.

The Legitimate Exercise of Power

In some cases, the constitutional law of a governing regime authorizes the suspension of established laws and regulations, allowing the government to act without defined limits on the scope of its authorized actions. A common way this can occur is in regimes that authorize the government to declare states of emergency that suspend the government’s adherence to the ordinary scope of authorized power.

There are strong reasons for states to resist invoking a condition of emergency. Clear lines of government authority, especially in the context of the state’s criminal law, tend to make people less fearful of the state, allowing the state more easily to call upon the people for support and thus enhancing the state’s legitimacy. Nevertheless, many regimes have the authority to declare emergencies—often in response to threats to public safety, such as terrorism—and to act in only vaguely specified ways during these periods.

45 Years Ago, a State of Emergency Was Declared in India

In 1975, during a time of social and political unrest, India’s national government declared a nationwide state of emergency, allowing the government to suspend civil liberties.

States generally see the establishment of public security as critical to their continued broad legitimacy: a state that cannot protect its people is likely to lose the widespread sentiment that it has the right to rule. Yet many states realize the potential negative consequences of unpredictable or unrestrained state action. For this reason, many regimes authorize the declaration of states of emergency , but only for limited periods of time. In France, for example, the president can declare a state of emergency for no more than 12 days, after which any extension must be approved by a majority vote of the legislature. 11 This power was enacted in response to terrorist attacks in 2015 and was renewed periodically until 2017. The state of emergency allowed, for example, certain otherwise unauthorized police procedures, such as searching for evidence without a warrant issued by a judge. 12 France’s law authorizing emergency declarations dates to the 1950s, and that it is fully authorized by the French Constitution and widely approved 13 illustrates that in some circumstances governing regimes can legitimately exercise sweeping and unstructured governmental powers. 14

Where there is broad public support, regimes may periodically and legitimately reauthorize states of emergency. Take, for example, the State of Israel. Israeli law authorizes two different forms of declarations of emergency, one that can be issued only by the legislature and one that can be issued by the government’s executive officials without the need for the legislature’s approval. The first form, which allows the government “to alter any law temporarily,” 15 can remain in effect for up to one year and can be renewed indefinitely. This allows governmental officials to use sweeping powers restricted only by the vague statement that emergency enactments may not “allow infringement upon human dignity.” 16 In addition, The Basic Laws of Israel allow the Israeli government—independent of a declaration of emergency by the legislature—to declare a condition of emergency. 17 These decrees can remain in effect for three months but can also be renewed indefinitely. 18 Pursuant to this authority, the government in 1948 issued an Emergency Defense Regulation that authorized the “establishing [of] military tribunals to try civilians without granting the right of appeal, allowing sweeping searches and seizures, prohibiting publication of books and newspapers, demolishing houses, detaining individuals administratively for an indefinite period, sealing off particular territories, and imposing curfew.” 19 This regulation has been renewed every year since 1948; today it applies mostly to the West Bank. 20 Both forms of emergency decrees have broad support in Israel, 21 indicating the popular sentiment that the Israeli government has the right to invoke such sweeping and unrestricted protocols because of the widely held belief among Israelis that the country faces serious and ongoing threats.

Even when such declarations are authorized and have initial broad support, the extensive use of emergency decrees risks undermining the regime’s legitimacy. In the early 1970s, then-president of the Philippines Ferdinand Marcos tested the limits of using emergency declarations to claim sweeping powers. In General Order No. 1, issued on September 22, 1972, Marcos declared:

“I, Ferdinand E. Marcos, President of the Philippines, by virtue of the powers vested in me by the Constitution as Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of the Philippines, do hereby proclaim that I shall govern the nation and direct the operation of the entire Government, including all its agencies and instrumentalities.” 22

As one scholar relates, Marcos “took great pains to ensure that his actions would align with the dictates of the law.” 23 The Philippine Constitution at the time allowed the president, in his role as Commander in Chief, to declare an emergency and to use emergency powers. 24 To ensure he could remain in office beyond the two four-year terms allotted to each president by the constitution, Marcos called for a constitutional convention, which was ratified by the population and which changed the position of president into that of a prime minister who could serve as long as the parliament approved. After an additional constitutional change in 1981 that made the office of president once again directly elected by voters, Marcos successfully ran for president, pledging to continue to exercise sweeping unrestricted powers. 25 Marcos has thus been called a “constitutional dictator,” 26 one who came to rule with unrestrained power through a popular constitution and as a leader who himself enjoyed wide popularity.

Martial Law in the Philippines

In 1972, the president of the Phillippines, Ferdinand Marcos, declared martial law. This video clip describes what led up to the proclamation and the extreme conditions in place in the Phillippines under martial law.

At least, that is, at first. Over time, Marcos’s support deteriorated as people tired of his often chaotic and increasingly cruel dictatorship. By 1986, his People Power Revolution saw the electorate turn on him, and the United States pressured him to respect the electoral outcome and leave office. 27

A regime that assumes long-lasting, sweeping, and only vaguely defined authority as the Philippines did under Marcos can become a police state (sometimes called a security state )—that is, a state that uses its police or military force to exercise unrestrained power. When states do not operate within clearly defined legal rules, political scientists say that the government in those states has little respect for the rule of law .

Governments may also exercise unauthorized but legitimate forms of power. Although the absence of authority can be grounds for judging an exercise of power to be illegitimate, this is not always the case. Examples of unauthorized but legitimate government activities tend to fall at two ends of the spectrum of public importance: governmental actions that are generally considered rather insignificant and actions that are deemed to be of tremendous importance, especially in grave moments of crisis.

On one end of the spectrum, as a result of the federal National Minimum Drinking Age Act of 1984, the legal age to purchase or publicly consume alcohol anywhere in the United States is 21. However, this law allows states to make exceptions to the age requirement for individuals under 21 who possess or consume alcohol in the presence of responsible parents. Not all states have created exceptions in their alcohol laws, and the possession of alcohol by anyone under the age of 21 is always technically illegal. 28 But in a number of these states there is such widespread sentiment that possession is acceptable in the presence of responsible adults that there is wide agreement that the state can exercise the unauthorized power to choose not to enforce the law under these conditions.

On the other end of the spectrum, during perceived moments of grave emergency, such as a dire terrorist threat, there may be broad agreement that the government may, legitimately exercise the unauthorized use of power. Princeton professor Kim Lane Scheppele notes that since 9/11 a number of world governments have made “quick responses [to terrorism] that violate the constitutional order followed by a progressive normalization.” 29 These actions might be limited in number, and the broader population may be unaware of their details and scope. Nevertheless, it is arguable that the population is aware that its government is taking unauthorized action in response to terrorist threats and that it supports the government’s right to do so.

The Illegitimate Exercise of Power and the Challenge of Revolutionary Change

Some regimes, though they have established lines of authority, may come to be broadly illegitimate over time. Throughout history, there are many examples of times when the sense that a regime was no longer legitimate led the people to revolt, either by sustained, widespread peaceful protests—such as in the Velvet Revolution in November of 1989 that led to the dissolution of the communist regime of Czechoslovakia—or by internal violent regime change—that is, the use of revolutionary violence. Revolutions intent on removing a constitution almost always seek to replace one constitution with another. Is there a standard of justice that transcends the constitutional law of a particular regime, a standard that can guide a people as they seek to free themselves from one constitution and replace it with another? Historically, in the Western political context, the standard of basic morality, justice, and social welfare has been the set of natural rights guaranteed by the natural law. More recently, the standard is referred to most often as fundamental human rights. (See also Chapter 2: Political Behavior Is Human Behavior and Chapter 3: Political Ideology .) The meaning of these concepts—natural law, natural rights, and human rights—is often contested, and this disagreement complicates any efforts to establish new constitutions to replace illegitimate regimes. Successful revolutionary change faces numerous challenges, including the fact that people might agree that a regime is not worthy of support, but their reasons for that opinion may differ. 30

In the 1930s and 1940s in India, Mahatma Gandhi employed civil disobedience to protest British imperil rule. One way a group can seek to change a law or even an entire governing system is to engage in civil disobedience , the nonviolent refusal to comply with authorized exercises of power. In the 1960s, civil rights groups such as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference led by Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. used civil disobedience to protest racial discrimination. Although both started out as small protest movements, they grew into movements capable of undermining the broad legitimacy of the governing regimes they opposed.

Methods of Developing Legitimacy

Widespread support for the right of the government to rule can come from a variety of sources. Max Weber argued that broad legitimacy develops in three primary ways. 31 The first of these is what he calls traditional legitimacy , where the governing regime embraces traditional cultural myths and accepted folkways. The United Arab Emirates can be considered an example of a regime with traditional legitimacy. Located in the far eastern section of the Arabian Peninsula, the seven small states that make up the UAE are joined together in a loose confederation, with each ruled by a monarch or emir. This system aligns with long-standing traditional practices of tribal chieftains associating together in a loose alliance to meet common objectives.

The second way legitimacy can accrue, according to Weber, is through charismatic legitimacy , when forceful leaders have personal characteristics that captivate the people. There are many examples of charismatic legitimacy throughout political history. Ruhollah Khomeini , a senior Shi‘a cleric who died in 1989, held remarkable appeal in Iran in the 1970s. Seen by many Iranians as a stern man of God, he was widely thought to be unaffected by the wealth, power, and corruption that so many Iranians saw as typifying the regime of the shah (or king) of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi . Khomeini was revered for his mysticism and his love of poetry. His personal magnetism played a large role in mobilizing Iranians to topple Pahlavi’s government and to replace it with the contemporary constitution of Iran, which establishes a Shi‘a theocracy , 32 a system of government in which religious leaders have authorized governmental power and possess either direct control over the government or enough authorized power to control the government’s policies. 33

Charismatic Che Guevara: Cuban Revolutionary

Revolutionary Che Guevara is revered in Cuba as an anti-establishment hero.

Weber’s third type of legitimacy is what he calls rational-legal legitimacy . This type of legitimacy develops as a result of the clarity and even-handedness with which a regime relates to the people. Take the example of Otto von Bismarck (1815–1898), who as the prime minister of Prussia forged a united German state. This new regime gained legitimacy not only because of the shared German culture of the formerly independent German states, but also because of the efficiency of its state bureaucracy, which established a uniform system of law administered by trained public servants.

Based on Weber’s analysis, a regime can secure legitimacy if the following are true:

- The regime solidifies and advances the material interests of a large percentage of the population.

- The regime advances deeply held moral and/or religious principles or advances strongly valued cultural traditions.

- The regime both supports religious, moral, or cultural values and advances the people’s economic interests.

- Based on an emotional sentiment, the people feel a strong emotional connection with the state.

- Based on a habitual respect for the government, the people unreflectively support the regime.

Legitimacy can be thought of as emerging from the agency of the people, who give their support to the regime either as a result of rational reflection, emotional attachment, or the acceptance of customary ways of relating to political power. However, one should not think of the agency of the people, by which they confer legitimacy on the regime, as something that is necessarily wholly independent of the actions of the regime itself. It is possible for a regime to shape the way people relate to it. Regimes employ different tactics toward that end, including government-controlled education, state control of the media and arts and entertainment sectors, and associating the regime, at least in the people’s perceptions, with the cultural or religious views predominant among the governed. As such, although some regimes may well enjoy broad legitimacy by the free choice of their citizenry, the possibility also exists that regimes gain legitimacy through what economist Edward Herman and philosopher and linguist Noam Chomsky call (in a different context) “ manufactured consent ”—that is, the shaping of the people’s response to the regime by state programs and activities designed to instill support for the regime, programs that might begin early in the citizens’ lives or that might affect citizens in subtle ways. 34 Examples of this can include widespread and rather blatant government propaganda , usually defined as misleading statements and depictions meant to persuade by means other than rational engagement, or subtle control over the content of what is taught in schools.

The contemporary government of the Eastern European nation of Belarus provides an especially vivid example of a regime seeking to manufacture consent through a coordinated effort to control access to information. Until the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, Belarus was a part of the Soviet state. After it established independence from the defunct Soviet Union, Belarus adopted a constitution that—on paper at least—requires free and fair elections for major government positions and affirms freedom of the press. Upon taking office as president after his victory in the 1994 election, the current Belarusian president Alexander Lukashenko promised to allow broad civil liberties. 35 Yet, over the past 25 years, Lukashenko has exerted tremendous control over the media, including the internet. 36 Media content in Belarus is heavily restricted such that opposition voices are almost never depicted positively, 37 and the regime has used its control over the media to promote Belarusian independence and Belarusian nationalism. 38 It is in this context that Lukashenko has continued to be reelected. The support he receives can be seen as being, to a large degree, a function of his government’s control over the formation of public opinion. To this extent, Lukashenko has followed the tradition of communist nations such as the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China, which have a long history of controlling their people’s access to information while advancing throughout society the state’s preferred political messages. The exercise of manufactured consent may not always be so overt in other countries, but it may be just as effective.

Failed and Fragile States

When a state’s ability to exercise control such that it can provide minimal conditions of law, order, and social stability deteriorates to a precariously low level, it is called a fragile state . Fragile states still assert the authority to rule but have serious difficulties actually ruling. The erosion of a state’s legitimacy can lead to state fragility. A fragile state can also occur when a broadly legitimate state has its capacity to provide order depleted as a result of an external force, such as an invading army. 39

If a fragile state loses the capacity to provide minimal conditions of law, order, and social stability entirely, it becomes a failed state . A failed state can emerge either when a state has collapsed so thoroughly that it lacks any governmental power altogether or when a shadow government has emerged—that is, an organization not authorized or desired by the government asserting rule over an area that effectively displaces and serves the same function as the official government. In this situation, internal violent regime change can occur, for if the shadow government becomes strong enough, it can mobilize sufficient power to dislodge entirely the existing regime and install itself as the authorized governmental entity. It may in the process have developed broad legitimacy, or it may simply have sufficient military power to take over the government, possessing the power of government and imposing laws that authorize its rule but not enjoying the wide support of the populace. A fragile government is one that is at serious risk of failing in either of these two ways or of experiencing violent regime change.

In the early 2020s, a shadow government formed in large sections of Afghanistan , and the forces of that shadow government carried out violent regime change. From 1996 until 2001, the Taliban , an extremist Sunni Islamic movement, ruled the Afghan government. In 2001, in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks orchestrated by Al Qaeda, a coalition of Western nations invaded Afghanistan. Due to concerns that the Afghan government had allowed the Al Qaeda terrorist network headed by Osama bin Laden to operate within the country’s borders, this coalition removed the Taliban from government. The coalition replaced the Taliban government with a governing regime that had considerable elements of representative democracy.

In early 2021, a shadow government led by members of the Taliban resurfaced in areas of Afghanistan. In some of these areas, the Taliban enjoyed wide popularity. Writing in January of 2021, the reporter Mujib Mashal described one such area, the city of Alingar:

“Alingar is . . . an example of how the Taliban have figured out local arrangements to act like a shadow government in areas where they have established control. The insurgents collect taxes . . . and have committees overseeing basic services to the public, including health, education and running local bazaars.” 40

In August 2021, the capital of Afghanistan, Kabul, fell to Taliban forces, and the more democratic regime collapsed. The Taliban has since consolidated its power, issued laws authorizing its regime, and sought to secure legitimacy among the broad Afghan population. Whether Afghanistan’s restored Taliban regime will endure remains an open question.

The current regime of Afghanistan represents a clear example of a fragile state. Fragile states either have a tenuous ability to keep the peace, administer court and educational systems, provide minimal sanitary and health services, and achieve stated goals such as conducting elections, or they are at risk of harboring within them rival organizations that can achieve these goals. Somalia is another example of a fragile state. 41 In more than 30 years of civil war, the regime governing Somalia has at times been at risk of failing to provide even a minimal level of security and stability. The condition in the country has stabilized somewhat from its low point in the early 1990s, when the risk of famine was so acute that the United States deployed military troops in Somalia to protect United Nations workers providing humanitarian relief in the country (a deployment that became controversial in the United States due to significant US military casualties). 42 Somalia, however, still shows signs of fragility. Although the Somali government scheduled national elections to take place in the summer of 2021—the first to be held in decades—these elections have been indefinitely postponed in the face of continuing instability in the region. 43

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-political-science/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Mark Carl Rom, Masaki Hidaka, Rachel Bzostek Walker

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Political Science

- Publication date: May 18, 2022

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-political-science/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-political-science/pages/13-1-contemporary-government-regimes-power-legitimacy-and-authority

© Jan 3, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Explore the Constitution

- The Constitution

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

- Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

Explore our new 15-unit high school curriculum.

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, classroom resources by topic, federalism and the separation of powers, introduction.

When crafting the Constitution, one of the central concerns of the Founding generation was how best to control government power. With the new Constitution, the Framers looked to strike an important balance—creating a new national government that was more powerful than the one that came before it while still protecting the American people’s most cherished liberties. They settled on a national government with defined but limited powers. Instead of placing authority in the hands of a single person (like a king), a small group of people (like an aristocracy), or even the whole people (like a direct democracy), the Framers divided power in two ways. At the national level, the Framers divided power between the three branches of government—the legislative branch, the executive branch and the judicial branch. This process of dividing power between different branches of government is called the separation of powers. From there, the Framers further divided power between the national government and the states under a system known as federalism.

Big Questions

What is the separation of powers how does it work what is federalism and how does it work, where do we see these constitutional principles in the constitution why are they needed, what are some of the key battles over the separation of powers and federalism in american history (and today), video: class recording.

Briefing Document

Video: constitution 101 lecture.

Constitution 101

Module 6: Separation of Powers and Federalism

More Video Lessons

Additional Resources

Does the separation of powers need a rewrite.

One prominent legal scholar offers a “friendly amendment” to Justice Robert Jackson’s famous concurrence in Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer.

Hamilton’s vision of federalism, national authority, and judicial review

How the right and left can unite around federalism, rumored federal medical marijuana changes raise federalism issues.

United States Attorney General Jeff Sessions is expected to release a report this week that may urge more federal interdiction against state-level medical marijuana programs – a move that would raise some compelling legal and policy questions.

Divided Power: The Re-Emergence of Federalism and the 17th Amendment

Federalism fight leads off big supreme court week.

A dispute over power sharing between the federal government and state government leads off a big week of Supreme Court cases on Monday. And it involves college football and New Jersey Governor Chris Christie.

The future of federalism

In a special live event at Georgetown University, Josh Blackman of the South Texas College of Law in Houston and Peter Edelman of Georgetown discuss the fate of federalism in the Trump era.

Two State Attorneys General on Federalism and States’ Rights Today

Attorneys General Phil Weiser of Colorado and Mark Brnovich of Arizona join for a bipartisan conversation exploring federalism and more.

Classroom Materials

Explore federalism on the interactive constitution.

- Article I - Congress

- Article II - The Presidency

- Article III - The Supreme Court

- Article I, Section 3 (the original Senate)

- Article I, Section 8 (the powers of Congress—especially the Commerce Clause and the Necessary and Proper Clause)

- Article I, Section 10 (limitations on the powers of the states)

- Article III (division of power between the state and federal courts)

- Article IV (Privilege and Immunities Clause and Fugitive Slave/Rendition Clause)

- Article VI (Supremacy Clause)

- 10th Amendment

- 13th Amendment, Section 2 (Enforcement Clause)

- 14th Amendment, Section 5 (Enforcement Clause)

- 15th Amendment, Section 2 (Enforcement Clause)

- Video: Interactive Constitution Tutorial

Explore Federalism and the Separation of Powers Questions

Plans of Study

Keep learning, more from the national constitution center.

Explore our new 15-unit core curriculum with educational videos, primary texts, and more.

Search and browse videos, podcasts, and blog posts on constitutional topics.

Founders’ Library

Discover primary texts and historical documents that span American history and have shaped the American constitutional tradition.

Modal title

Modal body text goes here.

Share with Students

Chapter 3: American Federalism

The Division of Powers

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the concept of federalism

- Discuss the constitutional logic of federalism

- Identify the powers and responsibilities of federal, state, and local governments

Modern democracies divide governmental power in two general ways; some, like the United States, use a combination of both structures. The first and more common mechanism shares power among three branches of government—the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary. The second, federalism, apportions power between two levels of government: national and subnational. In the United States, the term federal government refers to the government at the national level, while the term states means governments at the subnational level.

FEDERALISM DEFINED AND CONTRASTED

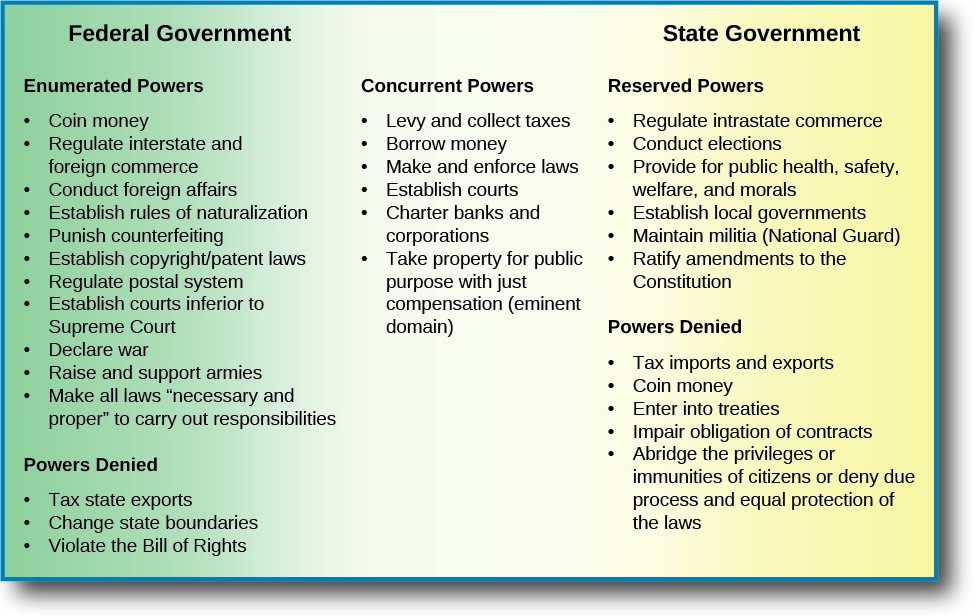

Federalism is an institutional arrangement that creates two relatively autonomous levels of government, each possessing the capacity to act directly on behalf of the people with the authority granted to it by the national constitution. [1] Although today’s federal systems vary in design, five structural characteristics are common to the United States and other federal systems around the world, including Germany and Mexico.

First, all federal systems establish two levels of government, with both levels being elected by the people and each level assigned different functions. The national government is responsible for handling matters that affect the country as a whole, for example, defending the nation against foreign threats and promoting national economic prosperity. Subnational, or state governments, are responsible for matters that lie within their regions, which include ensuring the well-being of their people by administering education, health care, public safety, and other public services. By definition, a system like this requires that different levels of government cooperate, because the institutions at each level form an interacting network. In the U.S. federal system, all national matters are handled by the federal government, which is led by the president and members of Congress, all of whom are elected by voters across the country. All matters at the subnational level are the responsibility of the fifty states, each headed by an elected governor and legislature. Thus, there is a separation of functions between the federal and state governments, and voters choose the leader at each level. [2]

The second characteristic common to all federal systems is a written national constitution that cannot be changed without the substantial consent of subnational governments. In the American federal system, the twenty-seven amendments added to the Constitution since its adoption were the result of an arduous process that required approval by two-thirds of both houses of Congress and three-fourths of the states. The main advantage of this supermajority requirement is that no changes to the Constitution can occur unless there is broad support within Congress and among states. The potential drawback is that numerous national amendment initiatives—such as the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which aims to guarantee equal rights regardless of sex—have failed because they cannot garner sufficient consent among members of Congress or, in the case of the ERA, the states.

Third, the constitutions of countries with federal systems formally allocate legislative, judicial, and executive authority to the two levels of government in such a way as to ensure each level some degree of autonomy from the other. Under the U.S. Constitution, the president assumes executive power, Congress exercises legislative powers, and the federal courts (e.g., U.S. district courts, appellate courts, and the Supreme Court) assume judicial powers. In each of the fifty states, a governor assumes executive authority, a state legislature makes laws, and state-level courts (e.g., trial courts, intermediate appellate courts, and supreme courts) possess judicial authority.

While each level of government is somewhat independent of the others, a great deal of interaction occurs among them. In fact, the ability of the federal and state governments to achieve their objectives often depends on the cooperation of the other level of government. For example, the federal government’s efforts to ensure homeland security are bolstered by the involvement of law enforcement agents working at local and state levels. On the other hand, the ability of states to provide their residents with public education and health care is enhanced by the federal government’s financial assistance.