What Is Education? Insights from the World's Greatest Minds

Forty thought-provoking quotes about education..

Posted May 12, 2014 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

As we seek to refine and reform today’s system of education , we would do well to ask, “What is education?” Our answers may provide insights that get to the heart of what matters for 21st century children and adults alike.

It is important to step back from divisive debates on grades, standardized testing, and teacher evaluation—and really look at the meaning of education. So I decided to do just that—to research the answer to this straightforward, yet complex question.

Looking for wisdom from some of the greatest philosophers, poets, educators, historians, theologians, politicians, and world leaders, I found answers that should not only exist in our history books, but also remain at the core of current education dialogue.

In my work as a developmental psychologist, I constantly struggle to balance the goals of formal education with the goals of raising healthy, happy children who grow to become contributing members of families and society. Along with academic skills, the educational journey from kindergarten through college is a time when young people develop many interconnected abilities.

As you read through the following quotes, you’ll discover common threads that unite the intellectual, social, emotional, and physical aspects of education. For me, good education facilitates the development of an internal compass that guides us through life.

Which quotes resonate most with you? What images of education come to your mind? How can we best integrate the wisdom of the ages to address today’s most pressing education challenges?

If you are a middle or high school teacher, I invite you to have your students write an essay entitled, “What is Education?” After reviewing the famous quotes below and the images they evoke, ask students to develop their very own quote that answers this question. With their unique quote highlighted at the top of their essay, ask them to write about what helps or hinders them from getting the kind of education they seek. I’d love to publish some student quotes, essays, and images in future articles, so please contact me if students are willing to share!

What Is Education? Answers from 5th Century BC to the 21 st Century

- The principle goal of education in the schools should be creating men and women who are capable of doing new things, not simply repeating what other generations have done. — Jean Piaget, 1896-1980, Swiss developmental psychologist, philosopher

- An education isn't how much you have committed to memory , or even how much you know. It's being able to differentiate between what you know and what you don't. — Anatole France, 1844-1924, French poet, novelist

- Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world. — Nelson Mandela, 1918-2013, South African President, philanthropist

- The object of education is to teach us to love beauty. — Plato, 424-348 BC, philosopher mathematician

- The function of education is to teach one to think intensively and to think critically. Intelligence plus character - that is the goal of true education — Martin Luther King, Jr., 1929-1968, pastor, activist, humanitarian

- Education is what remains after one has forgotten what one has learned in school. Albert Einstein, 1879-1955, physicist

- It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it. — Aristotle, 384-322 BC, Greek philosopher, scientist

- Education is the power to think clearly, the power to act well in the world’s work, and the power to appreciate life. — Brigham Young, 1801-1877, religious leader

- Real education should educate us out of self into something far finer – into a selflessness which links us with all humanity. — Nancy Astor, 1879-1964, American-born English politician and socialite

- Education is not the filling of a pail, but the lighting of a fire. — William Butler Yeats, 1865-1939, Irish poet

- Education is freedom . — Paulo Freire, 1921-1997, Brazilian educator, philosopher

- Education is not preparation for life; education is life itself. — John Dewey, 1859-1952, philosopher, psychologist, education reformer

- Education is the key to unlock the golden door of freedom. — George Washington Carver, 1864-1943, scientist, botanist, educator

- Education is an admirable thing, but it is well to remember from time to time that nothing that is worth knowing can be taught. — Oscar Wilde, 1854-1900, Irish writer, poet

- The whole purpose of education is to turn mirrors into windows. — Sydney J. Harris, 1917-1986, journalist

- Education's purpose is to replace an empty mind with an open one. — Malcolm Forbes, 1919-1990, publisher, politician

- No one has yet realized the wealth of sympathy, the kindness and generosity hidden in the soul of a child. The effort of every true education should be to unlock that treasure. — Emma Goldman, 1869 – 1940, political activist, writer

- Much education today is monumentally ineffective. All too often we are giving young people cut flowers when we should be teaching them to grow their own plants. — John W. Gardner, 1912-2002, Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare under President Lyndon Johnson

- Education is simply the soul of a society as it passes from one generation to another. — Gilbert K. Chesterton, 1874-1936, English writer, theologian, poet, philosopher

- Education is the movement from darkness to light. — Allan Bloom, 1930-1992, philosopher, classicist, and academician

- Education is learning what you didn't even know you didn't know. -- Daniel J. Boorstin, 1914-2004, historian, professor, attorney

- The aim of education is the knowledge, not of facts, but of values. — William S. Burroughs, 1914-1997, novelist, essayist, painter

- The object of education is to prepare the young to educate themselves throughout their lives. -- Robert M. Hutchins, 1899-1977, educational philosopher

- Education is all a matter of building bridges. — Ralph Ellison, 1914-1994, novelist, literary critic, scholar

- What sculpture is to a block of marble, education is to the soul. — Joseph Addison, 1672-1719, English essayist, poet, playwright, politician

- Education is the passport to the future, for tomorrow belongs to those who prepare for it today. — Malcolm X, 1925-1965, minister and human rights activist

- Education is the key to success in life, and teachers make a lasting impact in the lives of their students. — Solomon Ortiz, 1937-, former U.S. Representative-TX

- The very spring and root of honesty and virtue lie in good education. — Plutarch, 46-120AD, Greek historian, biographer, essayist

- Education is a shared commitment between dedicated teachers, motivated students and enthusiastic parents with high expectations. — Bob Beauprez, 1948-, former member of U.S. House of Representatives-CO

- The most influential of all educational factors is the conversation in a child’s home. — William Temple, 1881-1944, English bishop, teacher

- Education is the leading of human souls to what is best, and making what is best out of them. — John Ruskin, 1819-1900, English writer, art critic, philanthropist

- Education levels the playing field, allowing everyone to compete. — Joyce Meyer, 1943-, Christian author and speaker

- Education is what survives when what has been learned has been forgotten. — B.F. Skinner , 1904-1990, psychologist, behaviorist, social philosopher

- The great end of education is to discipline rather than to furnish the mind; to train it to the use of its own powers rather than to fill it with the accumulation of others. — Tyron Edwards, 1809-1894, theologian

- Let us think of education as the means of developing our greatest abilities, because in each of us there is a private hope and dream which, fulfilled, can be translated into benefit for everyone and greater strength of the nation. — John F. Kennedy, 1917-1963, 35 th President of the United States

- Education is like a lantern which lights your way in a dark alley. — Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, 1918-2004, President of the United Arab Emirates for 33 years

- When educating the minds of our youth, we must not forget to educate their hearts. — Dalai Lama, spiritual head of Tibetan Buddhism

- Education is the ability to listen to almost anything without losing your temper or self-confidence . — Robert Frost, 1874-1963, poet

- The secret in education lies in respecting the student. — Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1803-1882, essayist, lecturer, and poet

- My mother said I must always be intolerant of ignorance, but understanding of illiteracy. That some people, unable to go to school, were more educated and more intelligent than college professors. — Maya Angelou, 1928-, author, poet

©2014 Marilyn Price-Mitchell. All rights reserved. Please contact for permission to reprint.

Marilyn Price-Mitchell, Ph.D., is an Institute for Social Innovation Fellow at Fielding Graduate University and author of Tomorrow’s Change Makers.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

What’s the point of education? It’s no longer just about getting a job

Researcher for the University of Queensland Critical Thinking Project; and Online Teacher at Education Queensland's IMPACT Centre, The University of Queensland

Disclosure statement

Luke Zaphir does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Queensland provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

This essay is part of a series of articles on the future of education.

For much of human history, education has served an important purpose, ensuring we have the tools to survive. People need jobs to eat and to have jobs, they need to learn how to work.

Education has been an essential part of every society. But our world is changing and we’re being forced to change with it. So what is the point of education today?

The ancient Greek model

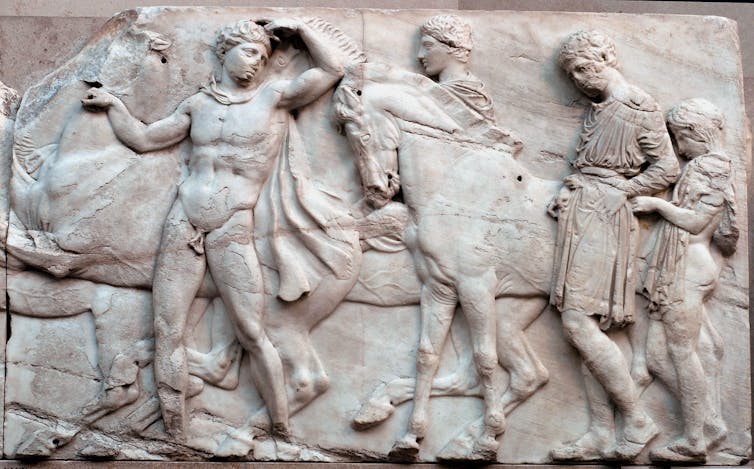

Some of our oldest accounts of education come from Ancient Greece. In many ways the Greeks modelled a form of education that would endure for thousands of years. It was an incredibly focused system designed for developing statesmen, soldiers and well-informed citizens.

Most boys would have gone to a learning environment similar to a school, although this would have been a place to learn basic literacy until adolescence. At this point, a child would embark on one of two career paths: apprentice or “citizen”.

On the apprentice path, the child would be put under the informal wing of an adult who would teach them a craft. This might be farming, potting or smithing – any career that required training or physical labour.

The path of the full citizen was one of intellectual development. Boys on the path to more academic careers would have private tutors who would foster their knowledge of arts and sciences, as well as develop their thinking skills.

The private tutor-student model of learning would endure for many hundreds of years after this. All male children were expected to go to state-sponsored places called gymnasiums (“school for naked exercise”) with those on a military-citizen career path training in martial arts.

Those on vocational pathways would be strongly encouraged to exercise too, but their training would be simply for good health.

Read more: Guide to the classics: Homer's Iliad

Until this point, there had been little in the way of education for women, the poor and slaves. Women made up half of the population, the poor made up 90% of citizens, and slaves outnumbered citizens 10 or 20 times over .

These marginalised groups would have undergone some education but likely only physical – strong bodies were important for childbearing and manual labour. So, we can safely say education in civilisations like Ancient Greece or Rome was only for rich men.

While we’ve taken a lot from this model, and evolved along the way, we live in a peaceful time compared to the Greeks. So what is it that we want from education today?

We learn to work – the ‘pragmatic purpose’

Today we largely view education as being there to give us knowledge of our place in the world, and the skills to work in it. This view is underpinned by a specific philosophical framework known as pragmatism. Philosopher Charles Peirce – sometimes known as the “father of pragmatism” – developed this theory in the late 1800s.

There has been a long history of philosophies of knowledge and understanding (also known as epistemology). Many early philosophies were based on the idea of an objective, universal truth. For example, the ancient Greeks believed the world was made of only five elements: earth, water, fire, air and aether .

Read more: Where to start reading philosophy?

Peirce, on the other hand, was concerned with understanding the world as a dynamic place. He viewed all knowledge as fallible. He argued we should reject any ideas about an inherent humanity or metaphysical reality.

Pragmatism sees any concept – belief, science, language, people – as mere components in a set of real-world problems.

In other words, we should believe only what helps us learn about the world and require reasonable justification for our actions. A person might think a ceremony is sacred or has spiritual significance, but the pragmatist would ask: “What effects does this have on the world?”

Education has always served a pragmatic purpose. It is a tool to be used to bring about a specific outcome (or set of outcomes). For the most part, this purpose is economic .

Why go to school? So you can get a job.

Education benefits you personally because you get to have a job, and it benefits society because you contribute to the overall productivity of the country, as well as paying taxes.

But for the economics-based pragmatist, not everyone needs to have the same access to educational opportunities. Societies generally need more farmers than lawyers, or more labourers than politicians, so it’s not important everyone goes to university.

You can, of course, have a pragmatic purpose in solving injustice or creating equality or protecting the environment – but most of these are of secondary importance to making sure we have a strong workforce.

Pragmatism, as a concept, isn’t too difficult to understand, but thinking pragmatically can be tricky. It’s challenging to imagine external perspectives, particularly on problems we deal with ourselves.

How to problem-solve (especially when we are part of the problem) is the purpose of a variant of pragmatism called instrumentalism.

Contemporary society and education

In the early part of the 20th century, John Dewey (a pragmatist philosopher) created a new educational framework. Dewey didn’t believe education was to serve an economic goal. Instead, Dewey argued education should serve an intrinsic purpose : education was a good in itself and children became fully developed as people because of it.

Much of the philosophy of the preceding century – as in the works of Kant, Hegel and Mill – was focused on the duties a person had to themselves and their society. The onus of learning, and fulfilling a citizen’s moral and legal obligations, was on the citizens themselves.

Read more: Explainer: what is inquiry-based learning and how does it help prepare children for the real world?

But in his most famous work, Democracy and Education , Dewey argued our development and citizenship depended on our social environment. This meant a society was responsible for fostering the mental attitudes it wished to see in its citizens.

Dewey’s view was that learning doesn’t just occur with textbooks and timetables. He believed learning happens through interactions with parents, teachers and peers. Learning happens when we talk about movies and discuss our ideas, or when we feel bad for succumbing to peer pressure and reflect on our moral failure.

Learning would still help people get jobs, but this was an incidental outcome in the development of a child’s personhood. So the pragmatic outcome of schools would be to fully develop citizens.

Today’s educational environment is somewhat mixed. One of the two goals of the 2008 Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians is that:

All young Australians become successful learners, confident and creative individuals, and active and informed citizens.

But the Australian Department of Education believes:

By lifting outcomes, the government helps to secure Australia’s economic and social prosperity.

A charitable reading of this is that we still have the economic goal as the pragmatic outcome, but we also want our children to have engaging and meaningful careers. We don’t just want them to work for money but to enjoy what they do. We want them to be fulfilled.

Read more: The Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians: what it is and why it needs updating

And this means the educational philosophy of Dewey is becoming more important for contemporary society.

Part of being pragmatic is recognising facts and changes in circumstance. Generally, these facts indicate we should change the way we do things.

On a personal scale, that might be recognising we have poor nutrition and may have to change our diet. On a wider scale, it might require us to recognise our conception of the world is incorrect, that the Earth is round instead of flat.

When this change occurs on a huge scale, it’s called a paradigm shift.

The paradigm shift

Our world may not be as clean-cut as we previously thought. We may choose to be vegetarian to lessen our impact on the environment. But this means we buy quinoa sourced from countries where people can no longer afford to buy a staple, because it’s become a “superfood” in Western kitchens.

If you’re a fan of the show The Good Place, you may remember how this is the exact reason the points system in the afterlife is broken – because life is too complicated for any person to have the perfect score of being good.

All of this is not only confronting to us in a moral sense but also seems to demand we fundamentally alter the way we consume goods.

And climate change is forcing us to reassess how we have lived on this planet for the last hundred years, because it’s clear that way of life isn’t sustainable.

Contemporary ethicist Peter Singer has argued that, given the current political climate, we would only be capable of radically altering our collective behaviour when there has been a massive disruption to our way of life.

If a supply chain is broken by a climate-change-induced disaster, there is no choice but to deal with the new reality. But we shouldn’t be waiting for a disaster to kick us into gear.

Making changes includes seeing ourselves as citizens not only of a community or a country, but also of the world.

Read more: Students striking for climate action are showing the exact skills employers look for

As US philosopher Martha Nussbaum argues, many issues need international cooperation to address . Trade, environment, law and conflict require creative thinking and pragmatism, and we need a different focus in our education systems to bring these about.

Education needs to focus on developing the personhood of children, as well as their capability to engage as citizens (even if current political leaders disagree) .

If you’re taking a certain subject at school or university, have you ever been asked: “But how will that get you a job?” If so, the questioner sees economic goals as the most important outcomes for education.

They’re not necessarily wrong, but it’s also clear that jobs are no longer the only (or most important) reason we learn.

Read the essay on what universities must do to survive disruption and remain relevant.

- Ancient Greece

- The future of education

Social Media Producer

Student Recruitment & Enquiries Officer

Dean (Head of School), Indigenous Knowledges

Senior Research Fellow - Curtin Institute for Energy Transition (CIET)

Laboratory Head - RNA Biology

"The Purpose of Education"

Author: King, Martin Luther, Jr. (Morehouse College)

Date: January 1, 1947 to February 28, 1947

Location: Atlanta, Ga.

Genre: Published Article

Topic: Martin Luther King, Jr. - Political and Social Views

Writing in the campus newspaper, the Maroon Tiger , King argues that education has both a utilitarian and a moral function. 1 Citing the example of Georgia’s former governor Eugene Talmadge, he asserts that reasoning ability is not enough. He insists that character and moral development are necessary to give the critical intellect humane purposes. King, Sr., later recalled that his son told him, “Talmadge has a Phi Beta Kappa key, can you believe that? What did he use all that precious knowledge for? To accomplish what?” 2

As I engage in the so-called “bull sessions” around and about the school, I too often find that most college men have a misconception of the purpose of education. Most of the “brethren” think that education should equip them with the proper instruments of exploitation so that they can forever trample over the masses. Still others think that education should furnish them with noble ends rather than means to an end.

It seems to me that education has a two-fold function to perform in the life of man and in society: the one is utility and the other is culture. Education must enable a man to become more efficient, to achieve with increasing facility the ligitimate goals of his life.

Education must also train one for quick, resolute and effective thinking. To think incisively and to think for one’s self is very difficult. We are prone to let our mental life become invaded by legions of half truths, prejudices, and propaganda. At this point, I often wonder whether or not education is fulfilling its purpose. A great majority of the so-called educated people do not think logically and scientifically. Even the press, the classroom, the platform, and the pulpit in many instances do not give us objective and unbiased truths. To save man from the morass of propaganda, in my opinion, is one of the chief aims of education. Education must enable one to sift and weigh evidence, to discern the true from the false, the real from the unreal, and the facts from the fiction.

The function of education, therefore, is to teach one to think intensively and to think critically. But education which stops with efficiency may prove the greatest menace to society. The most dangerous criminal may be the man gifted with reason, but with no morals.

The late Eugene Talmadge, in my opinion, possessed one of the better minds of Georgia, or even America. Moreover, he wore the Phi Beta Kappa key. By all measuring rods, Mr. Talmadge could think critically and intensively; yet he contends that I am an inferior being. Are those the types of men we call educated?

We must remember that intelligence is not enough. Intelligence plus character—that is the goal of true education. The complete education gives one not only power of concentration, but worthy objectives upon which to concentrate. The broad education will, therefore, transmit to one not only the accumulated knowledge of the race but also the accumulated experience of social living.

If we are not careful, our colleges will produce a group of close-minded, unscientific, illogical propagandists, consumed with immoral acts. Be careful, “brethren!” Be careful, teachers!

1. In 1925, the Maroon Tiger succeeded the Athenaeum as the campus literary journal at Morehouse. In the first semester of the 1947–1948 academic year, it won a First Class Honor Rating from the Associated Collegiate Press at the University of Minnesota. The faculty adviser to the Maroon Tiger was King’s English professor, Gladstone Lewis Chandler. King’s “The Purpose of Education” was published with a companion piece, “English Majors All?” by a fellow student, William G. Pickens. Among the many prominent black academicians and journalists who served an apprenticeship on the Maroon Tiger staff were Lerone Bennett, Jr., editor of Ebony ; Brailsford R. Brazeal, dean of Morehouse College; S. W. Garlington, city editor of New York’s Amsterdam News ; Hugh Gloster, president of Morehouse College; Emory O. Jackson, editor of the Birmingham World ; Robert E. Johnson, editor of Jet ; King D. Reddick of the New York Age ; Ira De A. Reid, chair of the Sociology Department at Atlanta University; and C. A. Scott, editor and general manager of the Atlanta Daily World . See The Morehouse Alumnus , July 1948, pp. 15–16; and Edward A. Jones, A Candle in the Dark: A History of Morehouse College (Valley Forge, Pa.: Judson Press, 1967), pp. 174, 260, 289–292.

2. Martin Luther King, Sr., with Clayton Riley, Daddy King: An Autobiography (New York: William Morrow, 1980), p. 143. In an unpublished autobiographical statement, King, Sr., remembered a meeting between Governor Eugene Talmadge and a committee of blacks concerning the imposition of the death penalty on a young black man for making improper remarks to a white woman. King, Sr., reported that Talmadge “sent us away humiliated, frustrated, insulted, and without hope of redress” (“The Autobiography of Daddy King as Told to Edward A. Jones” [n.d.], p. 40; copy in CKFC). Six months before the publication of King’s article, Georgia’s race-baiting former governor Eugene Talmadge had declared in the midst of his campaign for a new term as governor that “the only issue in this race is White Supremacy.” On 12 November, the black General Missionary Baptist Convention of Georgia designated his inauguration date, 9 January 1947, as a day of prayer. Talmadge died three weeks before his inauguration. See William Anderson, The Wild Man from Sugar Creek: The Political Career of Eugene Talmadge (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1975), pp. 226–237; Joseph L. Bernd, “White Supremacy and the Disfranchisement of Blacks in Georgia, 1946,” Georgia Historical Quarterly 66 (Winter 1982): 492–501; Clarence M. Wagner, Profiles of Black Georgia Baptists (Atlanta: Bennett Brothers, 1980), p. 104; and Benjamin E. Mays, Born to Rebel: An Autobiography (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1987), pp. 221–223.

Source: Maroon Tiger (January-February 1947): 10.

© Copyright Information

In the quest to transform education, putting purpose at the center is key

Subscribe to the center for universal education bulletin, emily markovich morris and emily markovich morris fellow - global economy and development , center for universal education @emilymarmorris ghulam omar qargha ghulam omar qargha fellow - global economy and development , center for universal education.

February 16, 2023

This commentary is the first of a three-part series on (1) why it is important to define the purpose of education, (2) how historical forces have interacted to shape the purposes of today’s modern schooling systems , and (3) the role of power in reshaping how the purpose of school is taken up by global education actors in policy and practice .

Education systems transformation is creating buzz among educators, policymakers, researchers, and families. For the first time, the U.N. secretary general convened the Transforming Education Summit around the subject in 2022. In tandem, UNESCO, UNESCO Institute for Statistics, UNICEF, the World Bank, and the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) co-authored “ From Learning Recovery to Education Transformation ” to lay a roadmap for how to move from COVID-19 school closures to systems change. Donor institutions like the Global Partnership for Education’s most recent strategy centers on systems transformation, and groups like the Global Campaign for Education are advocating for broader public engagement on transformative education.

Unless we anchor ourselves and define where we are coming from and where we want to go as societies and institutions, discussions on systems transformation will continue to be circuitous and contentious.

What is missing from the larger discussion on systems transformation is an intentional and candid dialogue on how societies and institutions are defining the purpose of education. When the topic is discussed, it often misses the mark or proposes an intervention that takes for granted that there is a shared purpose among policymakers, educators, families, students, and other actors. For example, the current global focus on foundational learning is not a purpose unto itself but rather a mechanism for serving a greater purpose — whether for economic development, national identity formation, and/or supporting improved well-being.

The Role of Purpose in Systems Transformation

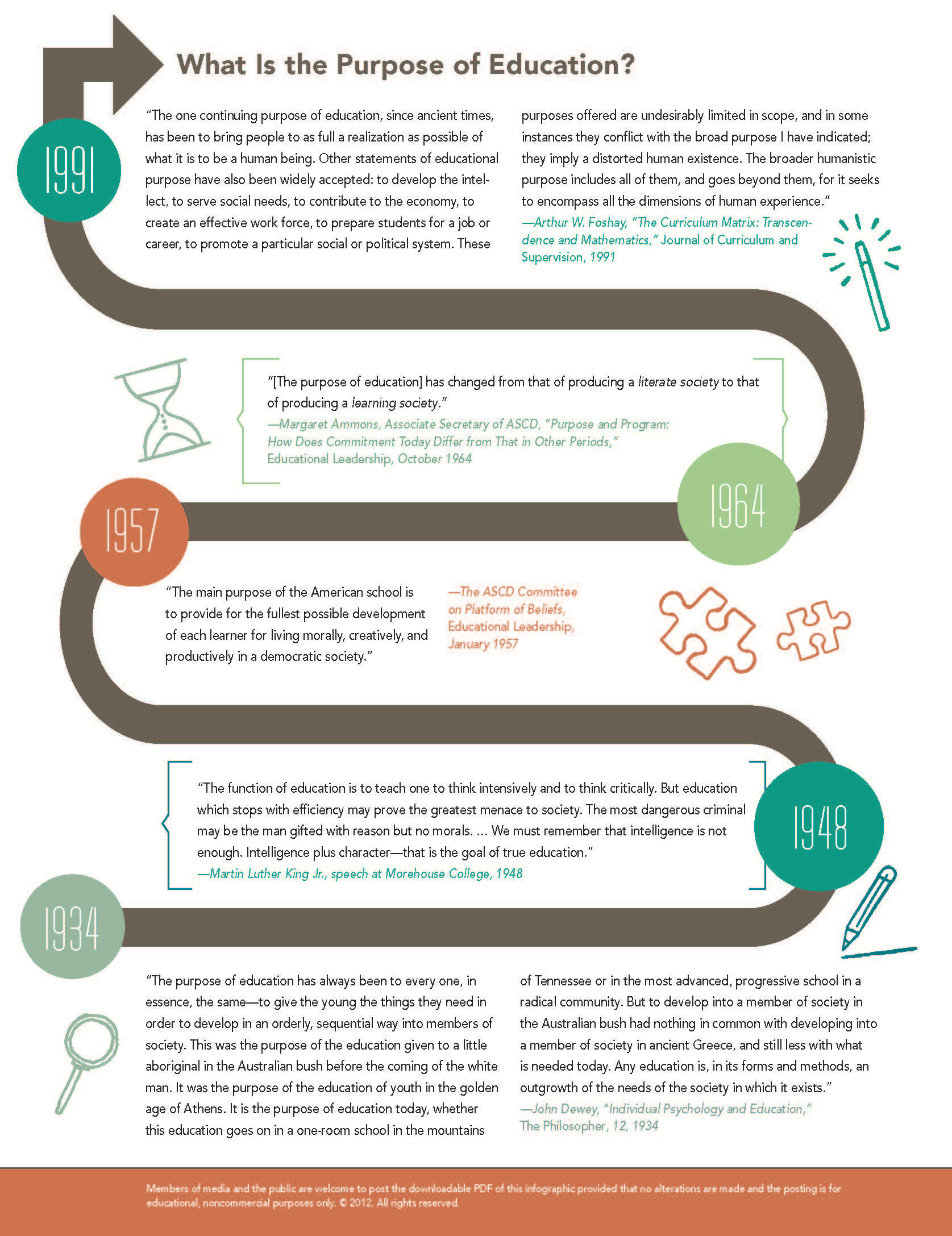

The purpose of education has sparked many conversations over the centuries. In 1930, Eleanor Roosevelt wrote in her essay in Pictorial Review , “What is the purpose of education? This question agitates scholars, teachers, statesmen, every group, in fact, of thoughtful men and women.” She argues that education is critical for building “good citizenship.” As Martin Luther King, Jr. urged in his 1947 essay, “ The Purpose of Education ,” education transmits “not only the accumulated knowledge of the race but also the accumulated experience of social living.” King urged us to see the purpose of education as a social and political struggle as much as a philosophical one.

In contemporary conversations, the purpose of education is often classified in terms of the individual and social benefits—such personal, cultural, economic, and social purposes or individual/social possibility and individual/social efficiency . However, when countries and communities define the purpose, it needs to be an intentional part of the transformation process. As laid out in the Center for Universal Education’s (CUE’s) policy brief “ Transforming Education Systems: Why, What, and How ,” defining and deconstructing assumptions is critical to building a “broadly shared vision and purpose” of education.

Education and the Sustainable Development Goals

Underlying all the different purposes of education lies the foundational framing of education as a human right in the Sustainable Development Goals. People of all races, ethnicities, gender identities, abilities, languages, religions, socio-economic status, and national or social origins have the right to an education as affirmed in Article 26 of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights . This legal framework has fueled the education for all movement and civil rights movements around the world, alongside the Convention of the Rights of the Child of 1989 , which further protects children’s rights to a quality, safe, and equitable education. Defending people’s right to education regardless of how they will use their education helps keep us from losing sight of why we are having these conversations.

Themes in education from the Sustainable Development Goals cross multiple purposes. For example, lifelong learning and environmental education are two key areas that extend across purposes. Lifelong learning emphasizes that education extends across age groups, education levels, modalities, and geographies. In some contexts, lifelong learning can be professional growth for economic development, but it can also be practice for spiritual growth. Similarly, environmental education may be taught as sustainable development or the balance among economic, social, and environmental protections through well-being and flourishing — or taught through a perspective of culturally sustaining practices influenced by Indigenous philosophies in education.

Five Key Purposes of Education

The purposes of education overlap and intersect, but pulling them apart helps us interrogate the dominant ways of framing education in the larger ecosystem and to draw attention to those that receive less attention. Categories also help us move from very philosophical and academic conversations into practical discussions that educators, learners, and families can join. Although these five categories do not do justice to the complexity of the conversation, they are a start.

- Education for economic development is the idea that learners pursue an education to eventually obtain work or to improve the quality, safety, or earnings of their current work. This purpose is the most dominant framing used by education systems around the world and part of the agenda to modernize and develop societies according to different stages of economic growth . This economic purpose is rooted in the human capital theory, which poses that the more schooling a person completes, the higher their income, wages, or productivity ( Aslam & Rawal, 2015; Berman, 2022 ). Higher individual earnings lead to greater household income and eventually higher national economic growth. In addition to the World Bank , global institutions like the United States Agency for International Development and the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development often position education primarily in relation to economic development. The promise of education as a key to social mobility and helping individuals and communities improve their economic circumstances also falls under this purpose ( World Economic Forum ).

- Education for building national identities and civic engagement positions education as an important conduit for promoting national, community, or other identities. With the emergence of modern states, education became a key tool for building national identity — and in some contexts , also democratic citizenship as demonstrated in Eleanor Roosevelt’s essay; this motivation continues to be a primary purpose in many localities ( Verger, Lubienski, & Steiner-Khamsi, 2016 ). Today this purpose is heavily influenced by human right s education — or the teaching and learning of — as well as peace education, to “sustain a just and equitable peace and world” ( Bajaj & Hantzopoulus, 2016, p. 1 ). This purpose is foundational to civics and citizenship education and international exchange programming focused on building global citizenship to name a few.

- Education as liberation and critical conscientization looks at the centrality of education in confronting and redressing different forms of structural oppression. Martin Luther King wrote about the purpose of education “to teach one to think intensively and to think critically.” Educator and philosopher Paolo Freire wrote extensively about the importance of education in developing a critical consciousness and awareness of the roots of oppression, and in identifying opportunities to challenge and transform this oppression through action. Critical race, gender , disabilities, and other theories in education further examine the ways education reproduces multiple and intersectional subordinations , but also how teaching and learning has the power to redress oppression through cultural and social transformation. As liberatory and critical educator, bell hooks wrote, “To educate as a practice of freedom is a way of teaching that anyone can learn” ( hooks, 1994, p. 13 ). Efforts to teach social justice and equity—from racial literacy to gender equity—often draw on this purpose.

- Education for well-being and flourishing emphasizes how learning is fundamental to building thriving people and communities. Although economic well-being is a component of this purpose, it is not the only purpose—rather social, emotional, physical and mental, spiritual and other forms of well-being are also privileged. Amartya Sen’s and Martha Nussbaum’s work on well-being and capabilities have greatly informed this purpose. They argue that individuals and communities must define education in ways that they have reason to value beyond just an economic end. The Flourish Project has been developing and advocating an ecological model for helping understand and map these different types of well-being. Vital to this purpose are also social and emotional learning efforts that support children and youth in acquiring knowledge, attitudes, and skills critical to positive mental and emotional health, relationships with others, among other areas ( CASEL, 2018 ; EASEL Lab, 2023 ).

- Education as culturally and spiritually sustaining is one of the purposes that receives insufficient attention in global education conversations. This purpose is critical to the past, present, and future field of education and emphasizes building relationships to oneself and one’s land and environment, culture, community, and faith. Centered in Indigenous philosophies in education , this purpose encompasses sustaining cultural knowledges often disregarded and displaced by modern schooling efforts. Borrowing from Django Paris’s concept of “culturally sustaining pedagogy , ” the purpose of teaching and learning goes beyond “building bridges” among the home, community, and school and instead brings together the learning practices that happen in these different domains. Similarly neglected in the discourse is the purpose of education for spiritual and religious development, which can be intertwined with Indigenous pedagogies , as well as education for liberation, and education for well-being and flourishing. Examples include the Hibbert Lectures of 1965 , which argue that Christian values should guide the purposes of education, and scholars of Islamic education who delve into the purposes of education in the Muslim world. Indigenous pedagogies, as well as spiritual and religious teaching , predate modern school movements, yet this undercurrent of moral, religious, character, and spiritual purposes of education is still alive in much of the world.

Beyond the Buzz

The way we define the purpose of education is heavily influenced by our experiences, as well as those of our families, communities, and societies. The underlying philosophies of education that are presented both influence our education systems and are influenced by our education systems. Unless we anchor ourselves and define where we are coming from and where we want to go as societies and institutions, discussions on systems transformation will continue to be circuitous and contentious. We will continue to focus on upgrading and changing standards, competencies, content, and practices without looking at why education matters. We will continue to fight over the place of climate change education, critical race theory, socio-emotional learning, and religious learning in our schools without understanding the ways each of these fits into the larger education ecosystem.

The intent of this blog is not to box education into finite purposes, but to remind us in the quest for systems transformation that there are multiple ways to see the purpose of education. Taking time to dig into the philosophies, histories, and complexities behind these purposes will help us ensure that we are headed toward transformation and not just adding to the buzz.

Related Content

Amelia Peterson

February 15, 2023

Devi Khanna, Amelia Peterson

February 10, 2023

Ghulam Omar Qargha, Rangina Hamidi, Iveta Silova

September 16, 2022

Global Education K-12 Education

Global Economy and Development

Center for Universal Education

Modupe (Mo) Olateju, Grace Cannon, Kelsey Rappe

June 14, 2024

Emily Markovich Morris, Laura Nóra, Richaa Hoysala, Max Lieblich, Sophie Partington, Rebecca Winthrop

May 31, 2024

Online only

9:30 am - 11:00 am EDT

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Prehistoric and primitive cultures

- Mesopotamia

- North China

- The Hindu tradition

- The introduction of Buddhist influences

- Classical India

- Indian influences on Asia

- Xi (Western) Zhou (1046–771 bce )

- Dong (Eastern) Zhou (770–256 bce )

- Qin autocracy (221–206 bce )

- Scholarship under the Han (206 bce –220 ce )

- Introduction of Buddhism

- Ancient Hebrews

- Education of youth

- Higher education

- The institutions

- Physical education

- The primary school

- Secondary education

- Early Roman education

- Roman modifications

- Education in the later Roman Empire

- Ancient Persia

- Elementary education

- Professional education

- Early Russian education: Kiev and Muscovy

- Influences on Muslim education and culture

- Aims and purposes of Muslim education

- Organization of education

- Major periods of Muslim education and learning

- Influence of Islamic learning on the West

- From the beginnings to the 4th century

- From the 5th to the 8th century

- The Irish and English revivals

- The cultural revival under Charlemagne and his successors

- Influences of the Carolingian renaissance abroad

- Education of the laity in the 9th and 10th centuries

- Monastic schools

- Urban schools

- New curricula and philosophies

- Thomist philosophy

- The Italian universities

- The French universities

- The English universities

- Universities elsewhere in Europe

- General characteristics of medieval universities

- Lay education and the lower schools

- The foundations of Muslim education

- The Mughal period

- The Tang dynasty (618–907 ce )

- The Song (960–1279)

- The Mongol period (1206–1368)

- The Ming period (1368–1644)

- The Manchu period (1644–1911/12)

- The ancient period to the 12th century

- Education of the warriors

- Education in the Tokugawa era

- Effect of early Western contacts

- The Muslim influence

- The secular influence

- Early influences

- Emergence of the new gymnasium

- Nonscholastic traditions

- Dutch humanism

- Juan Luis Vives

- The early English humanists

- Luther and the German Reformation

- The English Reformation

- The French Reformation

- The Calvinist Reformation

- The Roman Catholic Counter-Reformation

- The legacy of the Reformation

- The new scientism and rationalism

- The Protestant demand for universal elementary education

- The pedagogy of Ratke

- The pedagogy of Comenius

- The schools of Gotha

- Courtly education

- The teaching congregations

- Female education

- The Puritan reformers

- Royalist education

- The academies

- John Locke’s empiricism and education as conduct

- Giambattista Vico, critic of Cartesianism

- The condition of the schools and universities

- August Hermann Francke

- Johann Julius Hecker

- The Sensationists

- The Rousseauists

- National education under enlightened rulers

- Spanish and Portuguese America

- French Québec

- New England

- The new academies

- The middle colonies

- The Southern colonies

- Newfoundland and the Maritime Provinces.

- The social and historical setting

- The pedagogy of Pestalozzi

- The influence of Pestalozzi

- The pedagogy of Froebel

- The kindergarten movement

- The psychology and pedagogy of Herbart

- The Herbartians

- Other German theorists

- French theorists

- Spencer’s scientism

- Humboldt’s reforms

- Developments after 1815

- Girls’ schools

- The new German universities

- Development of state education

- Elementary Education Act

- Secondary and higher education

- The educational awakening

- Education for females

- New Zealand

- Education under the East India Company

- Indian universities

- The Meiji Restoration and the assimilation of Western civilization

- Establishment of a national system of education

- The conservative reaction

- Establishment of nationalistic education systems

- Promotion of industrial education

- Social and historical background

- Influence of psychology and other fields on education

- Traditional movements

- Progressive education

- Child-centred education

- Scientific-realist education

- Social-reconstructionist education

- Major trends and problems

- Early 19th to early 20th century

- Education Act of 1944

- The comprehensive movement

- Further education

- Imperial Germany

- Weimar Republic

- Nazi Germany

- Changes after World War II

- The Third Republic

- The Netherlands

- Switzerland

- Expansion of American education

- Curriculum reforms

- Federal involvement in local education

- Changes in higher education

- Professional organizations

- Canadian educational reforms

- The administration of public education

- Before 1917

- The Stalinist years, 1931–53

- The Khrushchev reforms

- From Brezhnev to Gorbachev

- Perestroika and education

- The modernization movement

- Education in the republic

- Education under the Nationalist government

- Education under communism

- Post-Mao education

- Communism and the intellectuals

- Education at the beginning of the century

- Education to 1940

- Education changes during World War II

- Education after World War II

- Pre-independence period

- The postindependence period in India

- The postindependence period in Pakistan

- The postindependence period in Bangladesh

- The postindependence period in Sri Lanka

- South Africa

- General influences and policies of the colonial powers

- Education in Portuguese colonies and former colonies

- German educational policy in Africa

- Education in British colonies and former colonies

- Education in French colonies and former colonies

- Education in Belgian colonies and former colonies

- Problems and tasks of African education in the late 20th century

- Colonialism and its consequences

- The second half of the 20th century

- The Islamic revival

- Migration and the brain drain

- The heritage of independence

- Administration

- Primary education and literacy

- Reform trends

- Malaysia and Singapore

- Philippines

- Education and social cohesion

- Education and social conflict

- Education and personal growth

- Education and civil society

- Education and economic development

- Primary-level school enrollments

- Secondary-level school enrollments

- Tertiary-level school enrollments

- Other developments in formal education

- Literacy as a measure of success

- Access to education

- Implications for socioeconomic status

- Social consequences of education in developing countries

- The role of the state

- Social and family interaction

- Alternative forms of education

What was education like in ancient Athens?

How does social class affect education attainment, when did education become compulsory, what are alternative forms of education, do school vouchers offer students access to better education.

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- World History Encyclopedia - Education in the Elizabethan Era

- National Geographic - Geography

- Table Of Contents

What does education mean?

Education refers to the discipline that is concerned with methods of teaching and learning in schools or school-like environments, as opposed to various nonformal and informal means of socialization .

Beginning approximately at the end of the 7th or during the 6th century, Athens became the first city-state in ancient Greece to renounce education that was oriented toward the future duties of soldiers. The evolution of Athenian education reflected that of the city itself, which was moving toward increasing democratization.

Research has found that education is the strongest determinant of individuals’ occupational status and chances of success in adult life. However, the correlation between family socioeconomic status and school success or failure appears to have increased worldwide. Long-term trends suggest that as societies industrialize and modernize, social class becomes increasingly important in determining educational outcomes and occupational attainment.

While education is not compulsory in practice everywhere in the world, the right of individuals to an educational program that respects their personality, talents, abilities, and cultural heritage has been upheld in various international agreements, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948; the Declaration of the Rights of the Child of 1959; and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights of 1966.

Alternative forms of education have developed since the late 20th century, such as distance learning , homeschooling , and many parallel or supplementary systems of education often designated as “nonformal” and “popular.” Religious institutions also instruct the young and old alike in sacred knowledge as well as in the values and skills required for participation in local, national, and transnational societies.

School vouchers have been a hotly debated topic in the United States. Some parents of voucher recipients reported high levels of satisfaction, and studies have found increased voucher student graduation rates. Some studies have found, however, that students using vouchers to attend private schools instead of public ones did not show significantly higher levels of academic achievement. Learn more at ProCon.org.

Should corporal punishment be used in elementary education settings?

Whether corporal punishment should be used in elementary education settings is widely debated. Some say it is the appropriate discipline for certain children when used in moderation because it sets clear boundaries and motivates children to behave in school. Others say can inflict long-lasting physical and mental harm on students while creating an unsafe and violent school environment. For more on the corporal punishment debate, visit ProCon.org .

Should dress codes be implemented and enforced in education settings?

Whether dress codes should be implemented and enforced in education settings is hotly debated. Some argue dress codes enforce decorum and a serious, professional atmosphere conducive to success, as well as promote safety. Others argue dress codes reinforce racist standards of beauty and dress and are are seldom uniformly mandated, often discriminating against women and marginalized groups. For more on the dress code debate, visit ProCon.org .

Recent News

education , discipline that is concerned with methods of teaching and learning in schools or school-like environments as opposed to various nonformal and informal means of socialization (e.g., rural development projects and education through parent-child relationships).

(Read Arne Duncan’s Britannica essay on “Education: The Great Equalizer.”)

Education can be thought of as the transmission of the values and accumulated knowledge of a society. In this sense, it is equivalent to what social scientists term socialization or enculturation. Children—whether conceived among New Guinea tribespeople, the Renaissance Florentines, or the middle classes of Manhattan—are born without culture . Education is designed to guide them in learning a culture , molding their behaviour in the ways of adulthood , and directing them toward their eventual role in society. In the most primitive cultures , there is often little formal learning—little of what one would ordinarily call school or classes or teachers . Instead, the entire environment and all activities are frequently viewed as school and classes, and many or all adults act as teachers. As societies grow more complex, however, the quantity of knowledge to be passed on from one generation to the next becomes more than any one person can know, and, hence, there must evolve more selective and efficient means of cultural transmission. The outcome is formal education—the school and the specialist called the teacher.

As society becomes ever more complex and schools become ever more institutionalized, educational experience becomes less directly related to daily life, less a matter of showing and learning in the context of the workaday world, and more abstracted from practice, more a matter of distilling, telling, and learning things out of context. This concentration of learning in a formal atmosphere allows children to learn far more of their culture than they are able to do by merely observing and imitating. As society gradually attaches more and more importance to education, it also tries to formulate the overall objectives, content, organization, and strategies of education. Literature becomes laden with advice on the rearing of the younger generation. In short, there develop philosophies and theories of education.

This article discusses the history of education, tracing the evolution of the formal teaching of knowledge and skills from prehistoric and ancient times to the present, and considering the various philosophies that have inspired the resulting systems. Other aspects of education are treated in a number of articles. For a treatment of education as a discipline, including educational organization, teaching methods, and the functions and training of teachers, see teaching ; pedagogy ; and teacher education . For a description of education in various specialized fields, see historiography ; legal education ; medical education ; science, history of . For an analysis of educational philosophy , see education, philosophy of . For an examination of some of the more important aids in education and the dissemination of knowledge, see dictionary ; encyclopaedia ; library ; museum ; printing ; publishing, history of . Some restrictions on educational freedom are discussed in censorship . For an analysis of pupil attributes, see intelligence, human ; learning theory ; psychological testing .

Education in primitive and early civilized cultures

The term education can be applied to primitive cultures only in the sense of enculturation , which is the process of cultural transmission. A primitive person, whose culture is the totality of his universe, has a relatively fixed sense of cultural continuity and timelessness. The model of life is relatively static and absolute, and it is transmitted from one generation to another with little deviation. As for prehistoric education, it can only be inferred from educational practices in surviving primitive cultures.

The purpose of primitive education is thus to guide children to becoming good members of their tribe or band. There is a marked emphasis upon training for citizenship , because primitive people are highly concerned with the growth of individuals as tribal members and the thorough comprehension of their way of life during passage from prepuberty to postpuberty.

Because of the variety in the countless thousands of primitive cultures, it is difficult to describe any standard and uniform characteristics of prepuberty education. Nevertheless, certain things are practiced commonly within cultures. Children actually participate in the social processes of adult activities, and their participatory learning is based upon what the American anthropologist Margaret Mead called empathy , identification, and imitation . Primitive children, before reaching puberty, learn by doing and observing basic technical practices. Their teachers are not strangers but rather their immediate community .

In contrast to the spontaneous and rather unregulated imitations in prepuberty education, postpuberty education in some cultures is strictly standardized and regulated. The teaching personnel may consist of fully initiated men, often unknown to the initiate though they are his relatives in other clans. The initiation may begin with the initiate being abruptly separated from his familial group and sent to a secluded camp where he joins other initiates. The purpose of this separation is to deflect the initiate’s deep attachment away from his family and to establish his emotional and social anchorage in the wider web of his culture.

The initiation “curriculum” does not usually include practical subjects. Instead, it consists of a whole set of cultural values, tribal religion, myths , philosophy, history, rituals, and other knowledge. Primitive people in some cultures regard the body of knowledge constituting the initiation curriculum as most essential to their tribal membership. Within this essential curriculum, religious instruction takes the most prominent place.

The Purpose of Education—According to Students

Teens respond to questions about the role of schools and teachers in their lives.

Radio Atlantic recently examined a question that underpins many, if not most, debates about education in the U.S.: What are public schools for? Increasingly, it seems many American parents expect schools to first and foremost serve as pipelines into the workforce—places where kids develop the skills they need to get into a good college, land a good job, and ultimately have a leg up in society. For those parents, consistently low test scores are evidence that the country’s education system is failing. Conversely, other parents argue that public schools’ primary responsibility is to create an educated citizenry, to instill kids with the kinds of values integral to a democratic society—curiosity, empathy, an appreciation for diversity, and so on.

Nuanced answers to that core question abound, shaping public policy and inciting PTA debates. But rarely do students get asked what they expect out of school. What does the promise of education mean to public-school students? Magdalena Slapik, a photojournalist working on an oral-history book project, has been interviewing public-school K-12 students across the country over the past several years to see what they have to say.

The Hechinger Report , which produced this project in partnership with The Atlantic , is running longer excerpts for 10 students, exploring questions such as: What do kids really think about school? How would they change it? Do they agree with Education Secretary Betsy DeVos’s conclusion that the U.S. school system is a “mess”? The Atlantic has published an abridged version of those excerpts to zero in on what students think their schools, teachers, and educations are for.

What role should school and teachers play in students’ lives?

I feel like the teacher and the school share a similar role. When a student goes to a certain school, they all come from different backgrounds, different upbringings: who was home, who took care of them, how much they saw them, what their occupation was. All these factors make them all different. I feel like school should be a place where I can learn about their culture and where they came from and them learn about mine. And, of course, you know, have your science and math, and learn how to write. But also be, not necessarily a culture shock, but a place to broaden your mind.

If you don’t do it young, then you’ll never do it, in my opinion. If we don’t start appreciating the kid next to you who has a completely different family style or family structure and life experience, then you won’t do it when you’re older. You’ll look at it in a single-track way. I feel like that’s the role of a teacher and school as an institution. Just to create a space where students can fail, and still be like, “OK, I’m gonna try again, but in a different way.” Instead of saying, “Ok, I failed. I’m not going to be anything. Let me just quit.”

What do you think is the purpose of education, and what role should school play in a student’s life?

The role of school is to educate me, so that when I go out into society I can become productive. I can be a functioning member of society who can work, who can educate someone else, who can be a role model. That’s what I always thought it was. Now, I’m seeing the role of school—of education—[as] basically a pastime, like a public babysitter for whoever feels their children should be here.

What is the role school and teachers should play in students’ lives?

The role of education and the role of teachers is to empower students not just to do what they want, but to make mistakes. The more often you make mistakes, the more likely you will be to do something important. Messing up is something that we have to foster. Because, that’s how expressing yourself works—it’s when you get the chance to be wrong and to, you know, just sort of have a go at random things.

That’s the problem with our education system now … mistakes are the worst things you can make. The reason that that’s bad is because it encourages students —when they take a test or when they study for something or when they do projects—to be dead inside. To sort of be sterilized. And music and the arts are about being fully alive, and about just being completely in the moment, where all your senses are enlivened and working. That’s the kind of experience that school should foster and harness and be focused on. Not in trying to get everyone to line up and just sort of follow the rules and take orders. That kind of environment is really destructive.

What do you think the teacher’s role should be in students’ lives?

I think the teacher’s role is to engage the student and find what makes the student interested in the subject. It’s about finding passion, and I think this school does a really good job of that—allowing you to really search out what you want to do and find your passion. They don’t care if that’s in academics or art or sports. If you can’t find something that you’re actually interested in, you’re going to be living a life of lack, just going by. It’s the same with how I think the public-school system really fails with standardized testing. You’re just learning to take a test. You’re not learning to actually be happy.

What do you feel is the purpose of education?

I think education is important, but it also depends. I don’t feel like you need to have an A+ in whatever, calculus, to just be able to work a normal job and make above minimum wage or anything. They teach you about all this stuff that happened hundreds of years ago, which, I like history, but they don’t really teach you about how to go and get a job, how to live on your own, pay this, pay that, when you actually have to do it. Or [they don’t] actually [prepare] you for college and dealing with that.

What role do you think school and teachers should play in students’ lives?

I think the role of teachers and education in general is to help us progress as a society. Not only in our smarts or technology, but to help us progress as a human race: preparing us to tackle the issues that [our predecessors] couldn’t defeat.

This post appears courtesy of The Hechinger Report .

Why is Education Important and What is the Purpose of Education

“If you can read this, thank a teacher.” It’s a cliche, but it’s true. If it weren’t for education at all levels, you wouldn’t be able to read, write, speak, think critically, make informed decisions, know right from wrong, effectively communicate, or understand how the world works.

Another famous quote that proclaims the importance of education comes from George Orwell, “If people cannot write well, they cannot think well, and if they cannot think well, others will do their thinking for them.”

It goes without saying that an educated population advances a society, but why, exactly, do different subsets of education matter? Does physical education really make a difference, and do we need to be spending precious dollars on arts education? Unequivocally, the answer is yes, but continue reading below to find out why.

Why is Early Childhood Education Important

Before we can understand the importance of early childhood education, we should be on the same page about what age early childhood education refers to. Typically, early childhood education encompasses any education a child receives up until the age of eight, or around third grade.

During these initial years of life, children’s brains are growing and learning at a rapid rate, and learning typically comes very easy to them. The purpose of education at this stage is to build a solid foundation for children to build upon for the rest of their lives.

When looking at pre-school, one of the earliest educational opportunities, a meta-analysis of studies on the benefits of early childhood education found that “7–8 of every 10 preschool children did better than the average child in a control or comparison group” when looking at standard measures of intelligence and academic achievement. This makes sense, given that education in those early years sets children up for success.

Another study followed a group of students who were given early high-quality education and compared them to a control group. Years later, the students who were given a high-quality education performed better than the other students in many areas, both academically and socially. These students:

- Scored higher on standardized testing

- Had higher attendance rates

- Had fewer discipline referrals

- Were rated higher by their teachers in terms of behaviors, social interactions, and emotional maturity.

The list of studies showing the importance of early childhood education goes on virtually forever. In addition to the educational advantages students with high-quality early education see, they also often find more pleasure in learning. When parents and teachers instill a love of learning early on, children are more likely to continue to love learning as they go through school.

The better foundation they have from an early age, the more likely students are to find success and not get frustrated. When students struggle due to poor early childhood education, the more likely they are to give up. A solid foundation is protective against falling behind, which is imperative, because once students begin to fall behind, it becomes very hard to catch back up.

In addition to the obvious benefits to each child, multiple studies have also shown that early childhood education programs provide an economic benefit to society as well.

In an article from the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, the authors Arthur J. Rolnick and Rob Grunewald write, “Investment in human capital breeds economic success not only for those being educated, but also for the overall economy.” Later, they add:

“The quality of life for a child and the contributions the child makes to society as an adult can be traced back to the first few years of life. From birth until about 5 years old a child undergoes tremendous growth and change. If this period of life includes support for growth in cognition, language, motor skills, adaptive skills and social-emotional functioning, the child is more likely to succeed in school and later contribute to society.” Arthur J. Rolnick and Rob Grunewald

Early education also teaches kids how to be students. While it’s true that students shouldn’t be stuck in a desk all day and that they do some of their best learning out in the real world, the reality is that much of our formal education takes place inside a classroom. Early childhood education teaches kids how to learn and how to conduct themselves in a classroom.

Why is Bilingual Education Important

Bilingual education is a necessity for some students who speak a language at home that is different from the language spoken at their school. Although it can be a challenge, it turns out these students are at an advantage compared to their peers, and voluntary bilingual education prepares students to enter a global workforce.

According to an article from NPR , people who are bilingual are better at switching from one task to another, potentially due to their learned ability to switch from one language to the other. It seems their brains become wired to be better at these types of tasks that make up executive function, or “the mental processes that enable us to plan, focus attention, remember instructions, and juggle multiple tasks successfully.” ( Harvard )

Understanding a second language often makes it easier to understand your first language as well. In the same NPR article, the author writes about students enrolled in a bilingual education program who showed better performance in reading English than students enrolled in an English-only program.

Jennifer Steele, who observed these students, said “Because the effects are found in reading, not in math or science where there were few differences, she suggests that learning two languages makes students more aware of how language works in general, aka ‘metalinguistic awareness.’”

I personally experienced this benefit when I was in school. Although I am by no means bilingual, I took a second language, French, in middle school and high school, and I often found that the words I knew in French helped me understand and decipher new words in English. I also better understood the complexities of English grammar and verb forms after learning about them in a second language.

Another obvious benefit of bilingual education is increased opportunities in the workforce. An article for the Chicago Tribune reports that there has been increasing demand for bilingual education starting at an early age, partially due to the demand for bilingual employees. Specifically, the article notes that the following industries look for people who speak more than one language: health care, education, customer service, government, finance, information technology, social services, and law enforcement.

Why is Physical Education Important

A good physical education program can set a child up for a lifetime of healthy habits. When I was in elementary school, I can remember asking what the point of gym class was. By the time I was in high school though, I realized that gym class was one of the most important classes I had ever taken.

In my senior year, I took a strength and conditioning class, and it set me up for a lifetime of treating my body well through exercise and proper nutrition. Without that class, I would have been lost the first time I stepped into a gym on my college campus.

Physical education isn’t just important for older children; even at the preschool level, it’s an essential part of the school day. Spend time around any young child, and you’ll realize that they can’t sit still for long. With so much energy and excitement for exploring the world, they need to keep their bodies moving. One study in the Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health found that physical education increased both total physical activity and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity in preschool children.

An article for Livestrong.com also highlighted the importance of gym class because it increases the amount of physical exercise children get, it increases coordination and flexibility, it produces endorphins that elevate kids’ mood, and it provides important opportunities for kids to socialize with each other.

In addition to teaching kids lifelong skills about moving their bodies, gym class benefits the whole child; in a book titled Educating the Student Body , researchers found “a direct correlation between regular participation in physical activity and health in school-age children, suggesting that physical activity provides important benefits directly to the individual child.” Specifically, they found that physical education is associated with academic benefits, better social and emotional well-being, and that it might even be protective against heart disease and type 2 diabetes.

Why is arts and music education important

In a world where education budgets are continually being slashed, arts and music education are tragically often the first to go. For many students, the arts are what gets them to school each day, and without these classes as a creative outlet to look forward to, school can be a major struggle. These classes are a refuge for many students, especially those who don’t excel in a traditional classroom environment.

In addition to being a safe and happy place for students to go during the day, the arts have many other benefits. A study called “SAT Scores of Students Who Study the Arts: What We Can and Cannot Conclude about the Association” for the Journal of Aesthetic Education found that students who take arts courses in high school (including music, theatre, etc.) tend to have higher SAT scores. While standardized test scores aren’t everything, this connection certainly does suggest the arts play an integral part in overall student success.

The Brookings Institution , a nonprofit public policy organization, also found connections between arts education and student success. They conducted a randomized controlled trial to investigate the effect of arts education on students, and found students with more education in the arts had better academic, social, and emotional outcomes than the students with less access to the arts.

In addition to measurable changes like a decrease in disciplinary infractions and an increase in writing scores, they also found that “students who received more arts education experiences are more interested in how other people feel and more likely to want to help people who are treated badly.” In elementary students specifically, they found “increases in arts learning positively and significantly affect students’ school engagement, college aspirations, and their inclinations to draw upon works of art as a means for empathizing with others.”

Why is STEM education important

If you’ve heard anything about education in the last ten years or so, you’ve undoubtedly heard about the push for STEM education, which stands for science, technology, engineering, and math. Schools everywhere seem to be offering more STEM courses, and for good reason.

In a study of pre-service and novice elementary school teachers, 100% agreed that STEM education is important, citing reasons such as:

- Providing a foundation for later academics

- Making connections to everyday life

- Preparing students for jobs

- Promoting higher order thinking

The U.S. Department of Education also offers compelling reasons why STEM education is important:

“In an ever-changing, increasingly complex world, it’s more important than ever that our nation’s youth are prepared to bring knowledge and skills to solve problems, make sense of information, and know how to gather and evaluate evidence to make decisions. These are the kinds of skills that students develop in science, technology, engineering and math—disciplines collectively known as STEM. If we want a nation where our future leaders, neighbors, and workers have the ability to understand and solve some of the complex challenges of today and tomorrow, and to meet the demands of the dynamic and evolving workforce, building students’ skills, content knowledge, and fluency in STEM fields is essential.”

If that weren’t enough to convince you, the Smithsonian Science Education Center echoes a similar sentiment,

We must all recognize that we live in an era of constant scientific discovery and technological change, which directly affects our lives and requires our input as citizens. And we must recognize that as our economy increasingly depends on these revolutionary new advances, many new jobs will be created in STEM fields. If we are to stay competitive as a nation, then we need to build a scientifically literate citizenry and a bank of highly skilled, STEM-literate employees.

Education students in STEM subjects gives them the knowledge and skills they need to succeed in our digital world that changes by the day. Students learn skills they’ll use to take on jobs that don’t even exist yet.

Why is College Education Important

The importance of college education is sometimes called into question for many reasons. According to CNBC , more than one in five college graduates work in jobs that don’t require a degree. Statistics like this make people wonder if it’s worth spending years of their lives going into debt only to land a job they could have gotten without a degree.