The Person-Centered Care in Nursing Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Person-centered care, holistic nursing, and cultural humility.

Health care workers should possess numerous competencies in order to provide their patients with high-quality care. However, the current landscape of health care is characterized by the changing power dynamic between medical professionals and patients that challenges their traditional roles within the system. Thus, the person-centered care approach, which allows patients to become active participants in their own treatment, is currently predominant in health care. This post is dedicated to person-centered care and the role and application of principles of holistic nursing, cultural humility, and self-reflection in nursing practice.

A person-centered strategy in nursing concerns patients being actively involved in the health care process. Person-centered care can be defined as an approach that takes into consideration “a person’s context and individual expression, preferences, and beliefs” (Santana et al., 2018, p. 430). Furthermore, it involves other stakeholders in the patient’s health in the decision-making process, for example, their family, friends, and caregivers participating in the patient care (Byrne et al., 2020). Thus, the person-centered care approach urges nurses to partner with their patients to design a more comprehensive and individualized care plan that translates into the patients receiving high-quality medical care and experiencing better health outcomes. Overall, it can be argued that, at its core, person-centered care is the approach that shows respect and consideration to the patients. It means viewing clients as persons with their own views and desires towards their health that should be taken into account when delivering care.

In my future role as a nursing practitioner, I will try to apply the principles of holistic nursing, cultural humility, and self-reflection in order to enhance the experience of patients assigned to me. Person-centered care can be viewed as a holistic approach to nursing as it takes account of different dimensions relating to the whole well-being of a person (Santana et al., 2018). Thus, holistic practice is not restricted to the aspects of physical and psychological health and well-being of a patient but considers the impact of cultural and religious beliefs and social environment on them. In my practice, I aim to include details on patients’ beliefs, socio-economic backgrounds, and social environment into their medical history to improve their health care experience and promote their health and well-being.

Furthermore, to provide patients with holistic health care, it is crucial for nursing practitioners to have cultural humility and self-reflection skills. Cultural humility in nursing is an ability of a nurse to enter a relationship with a patient “with the intention of honoring their beliefs, customs, and values” (Stubbe, 2020, p. 49). Thus, cultural humility involves a nurse’s understanding that patients know more about the nuances of their beliefs and customs. Therefore, their opinion should be the leading one regarding spiritual and cultural practices relating to health care. In my future practice, I will ask patients about the aspects of their beliefs, customs, and traditions that I am unfamiliar with to avoid stereotyping. I will also ensure that other medical professionals on the team are aware of these nuances. In addition, cultural humility demands continuous self-evaluation and self-reflection from nursing practitioners (Masters et al., 2019). Self-reflection allows nurses to examine their professional practices relating to clinical actions and person-centered care, allowing them to grow and develop further. I will strive to reflect on my encounters with patients to deliver better care and grow as a professional.

In summary, person-centered care is an integral approach in contemporary health care. It ensures that patients are put in the center of the health care process, and medical professionals account for their culture, personal beliefs, and preferences. Such competencies as the holistic approach to nursing, cultural humility, and self-reflection allow nursing practitioners to ensure the opinions and desires of the patients are considered and to provide them with high-quality care.

Byrne, A., Baldwin, A., & Harvey, C. (2020). Whose centre is it anyway? Defining person-centred care in nursing: An integrative review. PLOS ONE , 15 (3), 1–21. Web.

Masters, C., Robinson, D., Faulkner, S., Patterson, E., McIlraith, T., & Ansari, A. (2019). Addressing biases in patient care with the 5Rs of cultural humility, a clinician coaching tool. Journal of General Internal Medicine , 34 (4), 627–630. Web.

Santana, M. J., Manalili, K., Jolley, R. J., Zelinsky, S., Quan, H., & Lu, M. (2018). How to practice person-centred care: A conceptual framework. Health Expectations , 21 (2), 429–440. Web.

Stubbe, D. E. (2020). Practicing cultural competence and cultural humility in the care of diverse patients. Focus , 18 (1), 49–51. Web.

- Person-centered Approach vs. Cognitive-Behavioral Approach

- Psychology. Existential and Person-Centered Theories

- The Person-Centered Theory by Carl Rogers

- The Merging of Departments for Cost Containment

- The Future of Nursing Workforce in 50 Years

- Doctor of Nursing Practice Essentials in Psychiatry

- Middle-Range Theories and Conceptual Models

- Nursing Theory Discussion Board

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, June 6). The Person-Centered Care in Nursing. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-person-centered-care-in-nursing/

"The Person-Centered Care in Nursing." IvyPanda , 6 June 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/the-person-centered-care-in-nursing/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'The Person-Centered Care in Nursing'. 6 June.

IvyPanda . 2023. "The Person-Centered Care in Nursing." June 6, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-person-centered-care-in-nursing/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Person-Centered Care in Nursing." June 6, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-person-centered-care-in-nursing/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Person-Centered Care in Nursing." June 6, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-person-centered-care-in-nursing/.

Academic Support for Nursing Students

No notifications.

Disclaimer: This essay has been written by a student and not our expert nursing writers. View professional sample essays here.

View full disclaimer

Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this essay are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of NursingAnswers.net. This essay should not be treated as an authoritative source of information when forming medical opinions as information may be inaccurate or out-of-date.

Person-centred Care Essay

Info: 2359 words (9 pages) Nursing Essay Published: 11th Feb 2020

Reference this

Introduction: Reflective essay on person centred care

If you need assistance with writing your nursing essay, our professional nursing essay writing service is here to help!

Our nursing and healthcare experts are ready and waiting to assist with any writing project you may have, from simple essay plans, through to full nursing dissertations.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

- Nursing Essay Writing Service

- Nursing Dissertation Service

- Reflective Writing Service

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on the NursingAnswers.net website then please:

Our academic writing and marking services can help you!

- Marking Service

- Samples of our Work

- Full Service Portfolio

Related Lectures

Study for free with our range of nursing lectures!

- Drug Classification

- Emergency Care

- Health Observation

- Palliative Care

- Professional Values

Write for Us

Do you have a 2:1 degree or higher in nursing or healthcare?

Study Resources

Free resources to assist you with your nursing studies!

- APA Citation Tool

- Example Nursing Essays

- Example Nursing Assignments

- Example Nursing Case Studies

- Reflective Nursing Essays

- Nursing Literature Reviews

- Free Resources

- Reflective Model Guides

- Nursing and Healthcare Pay 2021

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Whose centre is it anyway? Defining person-centred care in nursing: An integrative review

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Central Queensland University School of Nursing, Midwifery and Social Science, Townsville, Queensland, Australia

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing

- Amy-Louise Byrne,

- Adele Baldwin,

- Clare Harvey

- Published: March 10, 2020

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229923

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

The aims of this literature review were to better understand the current literature about person-centred care (PCC) and identify a clear definition of the term PCC relevant to nursing practice.

Method/Data sources

An integrative literature review was undertaken using The Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Medline, Scopus and Pubmed databases. The limitations were English language, full text articles published between 1998 and 2018 within Australian, New Zealand, Canada, USA, Europe, Ireland and UK were included. The international context off PCC is then specifically related to the Australian context.

Review methods

The review adopted a thematic analysis to categorise and summarise themes with reference to the concept of PCC. The review process also adhered to the Preferred Reporting System for Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) and applied the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tools to ensure the quality of the papers included for deeper analysis.

While definitions of PCC do exist, there is no universally used definition within the nursing profession. This review has found three core themes which contribute to how PCC is understood and practiced, these are People , Practice and Power . This review uncovered a malalignment between the concept of PCC and the operationalisation of the term; this misalignment was discovered at both the practice level, and at the micro, meso and micro levels of the healthcare service.

The concept of PCC is well known to nurses, yet ill-defined and operationalised into practice. PCC is potentially hindered by its apparent rhetorical nature, and further investigation of how PCC is valued and operationalised through its measurement and reported outcomes is needed. Investigation of the literature found many definitions of PCC, but no one universally accepted and used definition. Subsequently, PCC remains conceptional in nature, leading to disparity between how it is interpreted and operationalised within the healthcare system and within nursing services.

Citation: Byrne A-L, Baldwin A, Harvey C (2020) Whose centre is it anyway? Defining person-centred care in nursing: An integrative review. PLoS ONE 15(3): e0229923. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229923

Editor: Janhavi Ajit Vaingankar, Institute of Mental Health, SINGAPORE

Received: September 17, 2019; Accepted: February 18, 2020; Published: March 10, 2020

Copyright: © 2020 Byrne et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work. The publication is funded under the first authors Research Higher Degree (PhD) budget.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Healthcare is changing, for both providers and recipients of care, with ongoing challenges to traditional roles and power balances. The causative factors of changes to the way healthcare is provided are complex, but one contributing factor is easier access to healthcare information and better-informed populations [ 1 ] whereby people as healthcare consumers have access to healthcare information through multiple media. On the surface, consumers are no longer seen as passive recipients of care, but rather as valuable and active members of the healthcare team. The concept of Person-Centred Care (PCC) is used to describe a certain model for the role of the patient within the healthcare system and the way in which care is provided to the patient [ 2 , 3 ]. Globally, there is continued advocacy for person-centred, individualised care [ 4 ], with the contemporary term for PCC being frequently presented in healthcare discourse, and frequently associated with the safety and quality of healthcare service provision [ 5 , 6 ]. Indeed, partnering with consumers within a person-centred framework is now a fundamental requirement for Australian healthcare services, meaning that they cannot achieve accreditation without demonstration of PCC [ 7 ]. Hence, PCC is now seen in healthcare service strategy and models of care, designed to support the voice of the patient and the role of the healthcare service in engaging with patients [ 6 ]. PCC also forms part of the Australian nursing professional standards [ 8 ] yet is paradoxically described as an ‘extra’ to nursing practice [ 9 ], taking a back seat to nursing tasks and errands that make up the day to day regime of the nurse.

Despite the discourse around PCC, and the requirements of PCC within healthcare, there appears to be no universally accepted definition of the term. This leaves the concept open to interpretation and potential confusion, particularly when personnel, in this case nurses, attempt to operationalise it. This review investigated the meaning of PCC with reference to nurses across different practice settings and specialities. To further facilitate the understanding [ 10 ] and theory development of the concept of PCC, this review adopted an integrative review methodology [ 11 ].

In the late 1950’s and 60’s, PCC, and care for the entire self was first described in the context of psychiatry, such as in Rogers’ ‘On becoming a person’ [ 12 ]. Patient-centred medicine was a term first coined by psychoanalyst Michael Balint. Balint was instrumental in the education of general practitioners around psychodynamic factors of patients and challenged the traditional illness-orientated model [ 13 ]. Balint’s challenge extended beyond the traditional healthcare model to include both the physical and psychosocial as part of the practitioner’s role. Balint explained; “Here , in additional to trying to discover a localized illness or illnesses , the doctor also has to examine the whole person in order to form what we call an ‘overall diagnosis . ’ The patient , in fact , has to be understood as a unique human-being . ” [ 13 p269].

The idea of caring for the whole person, and the divide between traditional medical practice and the psychosocial needs of the patient was discussed by Engle in 1977. He wrote; “The dominant model of disease today is biomedical…It assumes disease to be fully accounted for by deviations from the norm of measurable biological (somatic) variables . It leaves no room within its framework for the social , psychological , and behavioural dimensions of illness . ” [ 14 p379]. The biopsychosocial model proposed provided a new basis for care which included care of the mind and body. Over the succeeding years, this model of care and the notion of patient centre care continued to evolve, with many iterations of the term moving with the changing climate of healthcare systems.

PCC gained significant traction through the Institute of Medicines (IOM) 2001 report ‘Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System in the 21 st Century’ [ 15 ] as a key element of quality healthcare. The IOM provided one of the first contemporary definitions, stating that PCC “encompasses qualities of compassion , empathy and responsiveness to the needs , values and expressed preferences of the individual patient” [ 15 p48]. The World Health Organization continues to advocate for integrated care that is in tune with the patient’s wants and needs through the framework on Integrated People-Centred Care. This includes the vision that “all people have equal access to quality health services that are co-produced in a way that meets their life course needs” . [ 5 ] This framework aims to improve engagement of people and communities, strengthen governance and accountability, reorientate the model of healthcare, and coordinate services across sectors [ 5 ], seeing people as important contributors and decision makers over their own care.

More recently, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) defines PCC as an “innovative approach to the planning , delivery , and evaluation of health care … [involving] mutually beneficial partnerships among health care providers , patients , and families . ” [ 2 p13]. Thus, PCC has become an integral element of care from a quality, planning and practice level, and therefore appears prominently in Australian healthcare service discourse and associated models of care, often presented as an underpinning philosophy for the way in which nursing care is provided [ 3 ]. The concept of PCC continues to evolve, notably in the change to ‘person’ rather than ‘patient’ in recognition of the whole person, not simply the disease process. Other variables such as Family-centred care are used more in the context of aged care and paediatrics [ 16 , 17 ].

As the term has become more common in healthcare discourse, frameworks have emerged to allow the term to be operationalised into practice. There are several person-centred nursing frameworks including the Senses [ 18 ], VIP [ 19 ], 6 C’s [ 20 ], The Burford Model [ 21 ] and McCormack and McCance’s framework [ 22 ]. These frameworks describe elements such as attributes of staff, methods of interactions, coordination of care and services, the care environment and consideration of outcomes of care. These examples provide insight into attempts to operationalise PCC, into individual practice and healthcare service provision.

Nurses are the healthcare professionals who spend the most time with people and are therefore in a position to act as their advocates, with nursing staff managing the continuity of care [ 23 ]. This review seeks to investigate the meaning of person-centred nursing practice, and acts as a starting point for a wider study into the concept of PCC for people with long term conditions. Consumers of healthcare navigate a complex and fragmented system, with fragmentation leading to patients feeling lost, and a decrease in the quality of services offered [ 24 ]. This places even greater importance on a partnership between provider and receiver, particularly in the face of increasing chronicity/complexity of care. Within this fragmented and complex system, the patient must always remain at the centre of their care. Hence, there is a need for a robust definition to ensure PCC is more clearly operationalised and care delivered is designed around the needs of the patient, rather than trying to make the patient fit within the system.

This review uses the term person rather than patient in recognition of the person as a whole. Where clarity is required, the term healthcare consumer is used; a term frequently used in Australia.

The aim of this literature review was to understand better from the literature how nurses operationalise the definition of PCC.

Search questions

This literature review sought to answer the following questions:

- Is there a commonly/generally accepted definition for PCC that is used by nurses?

- How do nurses operationalise PCC in practice?

Search strategy

An integrative literature review was conducted using the terms Person Cent* Care OR Patient Cent* Care AND Nurs* AND Definition OR Meaning OR understanding OR Concept. The search was expanded to include similar terms and concepts such as patient/person-centredness and personalisation. A major subject heading of ‘patient centred care’ was used within the searches. This review is positioned within the nursing discipline; therefore, articles were included if they were specific to nursing or if they included nursing texts in the review. English language, full text articles published between 1998 and 2018 were included. Publications from Australia and New Zealand, Canada, USA, Europe, UK and Ireland were included to gain an understanding of PCC in the western context. The Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Medline, Scopus and Pubmed databases were searched. This search is registered with PROSPERO (ID number 148778) and was completed in March 2019. While the search strategy includes international literature, this will be related back to the Australian context, in order to understand how PCC operates within Australia.

Data extraction

The framework, from Whittemore and Knafl [ 11 ], describes a comprehensive review, identifying the maximum number of eligible primary sources and requires the researcher to explicitly justify decisions made in the sampling. Using this framework, a total of 1817 articles met the search terms, highlighting the volume of literature available on the concept of PCC. Table 1 provides the scope of inclusions and exclusions. From this, 255 articles were selected for review.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229923.t001

After removal of duplicates, 203 articles were subjected to full review. A further refined strategy excluded Key Performance Indicators (KPI), service measures, assessment tools and validations as the goal was defining the term, rather than to assess how it is measured; these represented a large proportion of the articles within the search. A total of 44 articles were subjected to quality review. To ensure adequate rigour, reliability and relevance, all articles were evaluated against the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) systematic and qualitative review checklists [ 25 , 26 ] by the lead author and reviewed by a senior researcher on the team. The relevance of the papers and the quality of the reviews/articles themselves was appraised. All articles were appraised against the aims of this review. Following this, a total of 17 articles were included in the final review. Fig 1 provides the summary for the search process while S1 File provides the PRISMA checklist.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229923.g001

Using the previously identified framework that allowed for data from diverse methods and approaches to be analysed and compared, a constant comparison method was used to convert data from different categories into patterns, themes and relationships. The data is thus displayed below in Table 2 to encompass the full depth of the concept and to provide new understanding, and its implications to practice [ 11 ]. Table 2 demonstrates the characteristics of the articles reviewed including their design methods, populations and findings.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229923.t002

This review set out to investigate if a universal definition of PCC for nursing exists and is used; what was uncovered was a deeper understanding of the concept and operationalisation of PCC, highlighting a malalignment between concept and reality. Three (3) core themes were identified in the review process, each of which is comprised of two (2) sub-themes. These three core themes of People , Practice , and Power , with the respective sub-themes are discussed are summarised in Table 3 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229923.t003

Theme 1: People

Unsurprisingly, the most common threads in the literature about PCC relate to people and, consistent with the philosophy of PCC, is described as basic, human kindness and respectful behaviour [ 22 , 27 , 28 , 29 ]. The core theme of People comprises two sub-themes: Recognising uniqueness and Partnerships .

Recognising uniqueness.

PCC, as the name suggests, is care that is considered and based on the individual person, who is the recipient of care. Prominent in the literature are the concepts of personhood, individuality and uniqueness [ 16 , 28 , 30 ]. Individuality, and the sense of self, understands that each person has their own unique wants, needs and desires [ 16 , 29 ] Personhood reinforces and values the complete person, with an understanding that illness affects the entire person [ 31 ]; an holistic consideration of the person that extends to family interventions and involvement [ 27 , 32 ] described as developing and maintaining trust within the family unit [ 33 , 34 ]. Uniqueness is central to this subtheme as recognition of the person as a unique being leads to unique and tailored care, based on the needs of the whole person [ 16 , 29 ].

Partnership.

The literature discusses the need for a relationship between healthcare provider and healthcare receiver as a way of facilitating information, knowledge and decision making. The term ‘relationship’ is prominent in the literature including the terms therapeutic relationship [ 16 ], clinical relationship [ 35 ] and partnership [ 29 , 36 , 37 ]. This is described in the contexts of cohesive, cooperative teams [ 29 , 32 ], mutuality between provider and receiver [ 38 ], and the balance of power and the sharing of knowledge [ 16 ]. These themes are further developed through the practice of the nurse and are thus carried forward to the next theme, Practice.

Theme 2: Practice

PCC is a product of person-centred practice, particularly in the context of nursing. However, the ability to practice PCC is influenced by professional and system factors. The core theme of Practice is comprised of the sub-themes Doing and Space .

‘Doing’ refers to the complex interplay of professional attributes, behaviours and tasks that makes up the daily remit of the nurse; that is, the ‘doing’ of nursing is a combination of these things within the care environment. Personal attributes of nursing staff emerge as a common element in the literature related to PCC. The literature describes attributes such as communication, respect, values, empathy, compassion and non-judgemental behaviour [ 9 , 29 ]. Lusk and Fater [ 7 ] further describe such attributes as caring, faith and hope, trust, relationships, teaching, learning and listening. In describing a framework to facilitate the practice of person-centred care, McCormack and McCance [ 22 ] discussed professional competence, interpersonal skill, job commitment and professional insight. Others have extended this to include understanding vulnerability, fear, the patient identity [ 30 ] and highlight the need to recognise the person as competent to make decisions [ 31 ]. This view, centred on dignity and privacy and the moral and ethical behaviours of the nurse [ 16 , 28 ], facilitates the relationship and balance of power with the person. Delivering whole person care includes elements such as respect for the individual [ 16 ], and planning care that is based on individual needs [ 25 ]. In practice, this is described as the person being valued for their lived experience, life stories [ 9 , 16 ] and the continuation of self [ 34 ]. Kitson et al. [ 35 ] describe this as addressing both the physical and emotional needs of the person and alleviating anxiety.

The existing literature alludes to the idea of opening a space to practice PCC. The literature describes this as being flexible within the care, offering choice [ 9 , 31 ], and creating opportunities for people to engage [ 34 ]. Practicing PCC involves freely giving information to the person [ 36 ] and finding the time to listen and engage with them [ 36 , 39 ], which implies that PCC is a proactive way of delivering nursing care. Gachoud et al. [ 32 ] found that nurses see themselves as most important in delivering PCC, with Doctors playing a lesser role in PCC practice. This understanding creates a concept whereby nurses are pivotal in creating an environment in which the person can truly engage.

While PCC is an individual practice method, the environment within which nurses’ practice must be considerate and supportive of the delivery of PCC as a significant priority; a view supported by McCormack and McCance [ 22 ] in their description of organisational systems and leadership within PCC. Despite competing priorities and the associated tasks of daily practice, nurses must find and open a space to practice PCC as an essential element of the profession. Interestingly, PCC within the literature is often discussed as an addition to nursing tasks. Edvardsson et al. state that promoting PCC in aged care includes doing ‘little extras’ [ 9 p50], such as understanding the patient’s life story, making eye contact and using the person’s name. Marshall et al. found that nurses describe PCC as ‘making the effort’ and ‘going the extra mile’ [ 37 p2667], being helpful and timely with care and attention. Others describe making choices available [ 16 ], ascertaining priorities [ 27 ] and doing the ‘right’ thing [ 31 ].

Theme 3: Power

PCC as a concept is about balancing power between the provider and receiver of care. The notion of PCC is imbued with connotation of power, discussed in relation to all elements of the care and is intertwined in some way with all themes within this review. The sub-themes of Power are the Power over one’s care and the Power to practice PCC .

Power over one’s care.

The idea of power balance is discussed in the literature and includes the sharing of knowledge [ 29 ], respect for decision making and individualised care based on these decisions [ 28 , 17 ]. Further to this is the notion of the person having ‘active’ involvement in the care process [ 22 , 35 ]. This is described through identification of the person’s strengths and reinforcing this through the care continuum [ 16 , 38 ]. In addition to this, the literature describes empowerment, promoting the sense of self efficacy [ 31 , 33 , 37 ], supporting the person to be as self-managing as possible [ 36 ] or to have a level of autonomy in their care. Here, the person holds the power in care planning and decision making throughout the care journey and there is a responsibility of knowledge transference and the maintenance of personal autonomy [ 35 ]. This is apparent in the literature through concepts such as control, rights, patient involvement and participation [ 27 , 33 , 35 ]. PCC, however, places importance on a marriage between provider and receiver as a process of sharing knowledge, rather being entirely self-governing, in which the provider (as the custodian of knowledge) has an obligation to impart knowledge.

The power to practice PCC.

The need for care systems to be innovative and make a commitment to PCC comes through in the literature [ 22 ], as well as the need for the environment to allow for flexibility and to factor time and space to practice PCC [ 9 , 36 ]. This is a significant shift from the traditional biomedical model, whereby emphasis on personal choice [ 33 ] and partnerships [ 17 ] must be considered within all layers of the healthcare system. Barriers and enablers including workplace culture, leadership [ 22 ], policy and practice, organisational systems, environment [ 28 , 35 ], workload, and ward culture [ 37 ] were identified. The literature also included topics around cost [ 28 ], care coordination [ 28 , 33 ] and of course, outcomes of clinical care provided [ 27 , 29 , 30 ].

Jakimowicz et al. [ 30 ] noted the conflict between system standards, benchmarking and the provision of PCC in a time poor environment. Consistently, the literature discussed the idea of measuring PCC as a method of quantifying this important element of nursing practice amongst the myriad of measurable tasks nursing time is allocated to. The need and ability to measure PCC is cited as crucial for quality improvement of care [ 31 , 38 ]. This review excluded articles related to the measurement of PCC as the primary aim was to find how PCC was defined, however this was still very much a part of the discussion around the meaning and practice of PCC. Morgan and Yoder [ 31 ] discussed several measurement tools, finding them to align more with the effect of care rather than the care directly. Lawrence & Kinn [ 27 ] found that outcome measures used where often in line with the needs and requirements of clinicians, auditors and researchers, or hospital clinical outcomes [ 33 ], rather than with the goals of the patient. Outcomes vary from self-care, patient satisfaction, well-being and improved quality of care [ 28 , 31 , 38 ] to improved adherence and decreased hospitalisation [ 29 ]. This highlights competing priorities within the nursing profession and demonstrates that nursing time is conflicted between what they ‘should’ do and what they ‘must’ do, hence highlighting a nurses limited power to practice PCC in the context of the system standards.

The review demonstrates that the concept of PCC is indeed a method of providing care, or the way in which nurses deliver care. To be person-centred, the nurse must recognise the person as unique, form meaningful partnerships, open a space within the doing of their day to involve and engage with the person, allowing the person control and power of their care.

It is interesting to note that while the existing literature covers a wide variety of clinical areas, and patient and staff perspectives, there were indeed core common themes of PCC. Despite the core concepts associated with PCC taking on more importance within certain clinical areas; for example, continuation of self in aged care [ 9 , 34 ], patient advocacy for intensive care [ 30 ], or communication in stroke care [ 27 ], they are consistent across specialities with the themes building on one another. Perhaps the reason why PCC has been so widely accepted is that the characteristics are simple, kind, human interactions, valuing both the person and the care provider. While definitions of PCC exist, there is no one universally used definition of PCC in nursing practice, potentially compounding a degree of separation between practice and healthcare systems. The findings demonstrate a tension between the theory and the conceptualisation of PCC, and as a result, the operationalisation of the term at both the practice level and a wider healthcare service level.

At the practice level, the theory/practice gap for PCC was evident. The theory/practice gap includes elements of practice failing to reflect theory, perceptions of theory being irrelevant to practice, and ritualistic nursing practice. Consequences of the theory/practice gap can greatly influence nursing practice and collaboration [ 40 ]. In the context of PCC, the theory/practice gap is apparent in the challenge of translating the ideas of PCC into a concrete concept. It is of significance that PCC is seen as ‘extra’ or additional to nursing tasks when these professional behaviours are in line with the Australian Nursing Professional Standards [ 8 ], which requires that they are an intrinsic element of the nursing profession. In fact, to be a registered nurse in Australia one must demonstrate respect for the person as the expert, respect autonomy and “ share knowledge and practice that supports person-centred care” [ 8 ]. This highlights an important matter for consideration; why are core elements of PCC being viewed as ‘going the extra mile’ rather than a core competency for nurses? Certainly, from the perspective of the professional standards, PCC should not be the road less travelled, but rather the daily standard practice of nursing. One answer to this may be the task orientation of the contemporary nursing culture that sees nurses required to meet organisational time allocations for care [ 41 ]. Sharp, McAllister and Broadbent [ 42 ] uncovered a tension between PCC and nursing culture, finding that nurses were increasingly bogged down with tasks and processes, taking them away from the people that they provide nursing care for. These authors found that this led to a feeling of frustration and helplessness in nurses who appear to have accepted the culture of auditable, measurable activities and processes, particularly within the climate of organisational accreditation requirements. This activity-based nursing environment manifests in missed nursing care largely related to patient centred elements, e.g. discharge planning, communication within the healthcare team, absence of adequate patient education on key factors of care such as medication guidance, functional assessment and so on [ 43 , 44 ].

Further, it is apparent that the concept of PCC cannot be isolated from other philosophies of nursing practice and in fact, is embedded in other approaches to nursing care. For example, as outlined by Kim [ 45 ], nursing is defined by dimensions, rather than characteristics. If PCC is considered as a dimension, a complex, interwoven mix of characteristics, then it is possible to gain some concrete understanding of PCC in the context of all clinical areas. The five dimensions proposed by Kim reflect the ‘human’ side of nursing practice, and like the general interpretation of PCC, shows how human interactions, values and knowledge combine to provide care. Kim goes on to say that these dimensions vary with individual nurses and changing clinical situations; which seems to fit with the current confusion about PCC giving choice and decision-making power to patients. As found in this review, PCC attempts to balance the power between providers of care and receivers, giving choice and decision-making power. Yet the focus on nursing tasks and prioritisation of these tasks is evident, demonstrating the malalignment between concept and practice, where research has identified that the current task-oriented system of nursing does fail to meet the care needs of patients [ 46 ].

Nursing practice, however, is only one element of delivering PCC within the healthcare system. This disparity extends between the concept of PCC and its ability to exist within the current healthcare system itself, where time to care is explicitly rationed through budgets that do not allow for individualised person-centred care [ 47 ].

The notion of PCC is one centred on mutuality and a balance of power; a distinct move from the paternalistic biomedical model to a biopsychosocial model that is guided by the person, rather than the disease process. However, in current healthcare services, care is often system centred. That is, care is organised, funded and coordinated in a way that meets the needs of the system or service [ 28 , 33 ]. System fragmentation is understood to have significant influence on people accessing care, whereby people with long-term and complex conditions are most vulnerable to the negative impact from the lack of care coordination and cohesion [ 48 ].

In Australia, complex funding models are central to the concept of system fragmentation which begins at the Commonwealth and State funding levels [ 48 ], making it difficult for patients to navigate the system. System silos remain a significant issue for healthcare services and for the delivery of care, with Medicare models remaining fragmented for specialist services [ 49 ]. The States are the healthcare system managers, yet the federal government holds the responsibility of leading primary healthcare. This presents a challenge in provided collaborative and integrated services, particularly for those with long-term conditions [ 50 ]. The OECD highlight the importance of reducing system fragmentation in order to ‘Improve the co-ordination of patient care .’ [ 50 p1].

Indeed, system fragmentation leads to an increased ‘treatment burden’, whereby poor treatment coordination, ineffective communication and confusion about treatments can contribute to poor health outcomes and greater levels of cost, time, travel and medications for the person [ 51 ] Sav et al. [ 51 ] discuss the need for individualised and coordinated services across specialities as a requirement for reducing treatment burden. In addition to this, the Australian Charter of Healthcare Rights prescribes the rights of those seeking care in any Australian service and includes the right to access, respect, communication and participation [ 52 ]. Accreditation of healthcare services is conditional to evidence of multi-level partnerships with consumers of health. Positive partnerships (PCC) are clearly linked to improved access to care, which in turn leads to reports of positive experiences and better-quality healthcare. Of critical importance at an organisational and government level, the standards also describe this partnership as a mechanism for reducing hospital costs through improved rates of preventable hospitalisation and reducing hospital length of stay [ 7 ].

Potentially Preventable Hospitalisations (PPH) place considerable economic and resource burden on the healthcare system, with approximately 47% of PPH being attributed to long-term conditions [ 53 ]. Thus, reducing preventable hospitalisation is a measurable target for healthcare services under the National Healthcare Agreement as a way of controlling the escalating costs of care and maintaining sound fiscal management of public services [ 54 ]. In line with the ACSQHC standard Partnering with Consumers , PCC has been introduced to some services as a mechanism for improving communication between services and those with long term conditions. What is less clear, is how care tailored to the individuals wants and needs of the patient (PCC), exists within a system predominately focused on reducing variation and the associated costs of care. While the philosophy of PCC naturally fits within the care environment, understanding how effective it is, how the person is included and how outcomes important to the person are captured, take a lower precedent to the measure of reduced hospital costs, self-efficacy and reduced hospitalisation. Capturing what is important for the individual presents a difficult task for services providing population-based care.

These system wide constraints provide a considerable challenge to nurses in their attempts to operationalise the concept of PCC. Nursing, it seems, has become task orientated, a sentiment supported by Foe & Kitson who found that nurses are constrained by a ‘checklist’ mentality, whereby completing and documenting tasks is seen as more important than engaging with the person [ 55 p100]. These tasks and checklists align with the requirements of the National Standards for hospital accreditation. An example of this is the need to collect data on the use of invasive devices or the allocated time intervals in which screening (such as skin inspection and falls risk) must occur; for example within eight (8) hours of admission [ 7 ]. Indeed, policy and procedure for nursing practice reflect that of the need of accreditation and national policy requirements as opposed to the needs of individual people. While partnering with consumers is an important element of the standards [ 7 ], quantifying the way in which healthcare services and indeed nurses engage with patients is less clear. Kitson states ‘ Nursing theory , it would seem , has been limited by the profession’s ability to systematically document the complexity and richness of what happens when nurses and patients (and their careers) interact’ [ 35 p99], an issue it seems stemming from the fact that nursing interventions promoting person-centred, compassionate care are poorly described, with little to no consensus on the term, and interventions that do exist are poorly evaluated [ 56 ]. On top of this, nurses are generally not encouraged, nor enabled to reflect on practice in order to generate new insights and nursing practice [ 35 ]. Molina-Mula et al. [ 23 ], discuss the nursing profession as being the key to professional teamwork models, meeting the needs of patients and thereby increasing their personal decision-making capacity. However, it is possible that PCC is hindered by the level of professional autonomy, time and space afforded to nurses [ 57 ]. Indeed, the malalignment discussed herein, demonstrates that nurses may be hindered at higher levels of system compliance or difficulties in coordinating care services, which permeates nursing culture and ultimately nursing practice, limiting their ability to provide PCC that is individualised to the people seeking care.

Finally, while this review excluded articles related to the measurement and indicators of PCC, this is undoubtedly linked to its perceived meaning and how it is operationalised. This review demonstrates that the understanding of PCC is made up of how and where PCC appears in healthcare discourse and shows that PCC is potentially skewed by how it is(n’t) measured and the outcomes that are(n’t) reported as a product of PCC. This finding presents a framework within which further investigation of the concept of PCC (Meaning, Practice, Measures, Outcomes) within healthcare services could be undertaken. This proposed framework will be applied by the author to conduct further research into the role of PCC within nurse-led service for people with long-term conditions.

Implications for practice

This review highlights the dominant discourse around the concept of PCC yet uncovered the idea of malalignment between the rhetoric and the reality of the concept. Further exploration of the alignment between healthcare services and the goal of PCC may prove beneficial in ensuring the practice of PCC is fostered from all levels of the healthcare service. The above provides a rationale for why the definition of PCC should be provided, given that the concept is currently somewhat nebulous in nature. A consistent definition, with reference to all levels of the healthcare service including practice, will ensure that the concept stays true to the philosophy of compassionate and balanced care. Any definition provided should carefully consider how PCC is measured and prioritised within the healthcare system, which has the potential to move the concept from its current rhetorical nature, to a genuine commitment and priority of nurses and services. Lastly, the review provides a basis for the importance of nursing education and workforce development of the concept and the practice of PCC, given the apparent barriers that nurses may face in delivering PCC.

Limitations

This integrated review was limited to articles relating to the nursing profession and hence has excluded reviews on PCC in relation to other disciplines. Practice related elements such as procedure, service measures and outcomes of PCC were excluded from this review as the aim was to find a generalised way of defining the term. Furthermore, only one framework met the criteria of the search strategy and was included, there are however, several frameworks for PCC in nursing and hence some elements of PCC and their definitions may have been excluded.

This review was performed with published literature only, with no investigation of grey literature undertaken. PCC is often discussed in healthcare service literature, including procedure, service profiles and service strategy. This information will undoubtedly have an impact on how nurses understand and practice PCC within their own area and within their service. This review was designed to investigate a universal definition of PCC as described in the literature and hence chose to limit this to an academic search. The practice of PCC from a policy to practice perspective perpetuates meaning and will be the subject of further research for the author.

This review was conducted as a starting point for the author’s research higher degree (PhD) studies, and hence the search strategy and quality processes were completed by one person. All elements of the review were discussed at length with academic supervisors to ensure adequate rigor and accuracy throughout the search, review and integrative process.

The concept of PCC is well known to nurses, yet ill-defined and operationalised into practice. Healthcare service policy and care provisions, and indeed nursing services, need a clear definition of PCC in order to work toward embedding it into practice and into models of care in a meaningful and genuine way. However, PCC is potentially hindered by its apparent rhetorical nature, and further investigation of how PCC is valued and operationalised through its measurement and reported outcomes will serve the philosophy of PCC well. Investigation of the literature found many definitions of PCC, but no one universally accepted and used definition. Subsequently, PCC remains conceptional in nature, leading to disparity between how it is(n’t)operationalised within the healthcare system and within nursing services. In light of the malalignment discovered within this review, a universal definition of PCC is not provided herein; instead, this review highlights the need for further investigation of PCC between the levels of the healthcare service (at the micro, meso and macro levels) and how this influences the critical work that nurses do in supporting people through their healthcare journey.

Supporting information

S1 file. prisma checklist..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229923.s001

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 2. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare. Patient-centred care: Improving quality and safety by focusing care on patients and consumers. [Internet]. Sydney: ACSQHC; 2010. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/PCCC-DiscussPaper.pdf (2010).

- PubMed/NCBI

- 4. Health Consumers Queensland. Consumer and Community Engagement Framework for Health Organisations and Consumers. Brisbane: HCQ; 2017. http://www.hcq.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/HCQ-CCE-Framework-2017.pdf

- 5. World Health Organization. WHO framework on integrated people-centred health Services [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2016. http://www.who.int/servicedeliverysafety/areas/people-centred-care/ipchs- what/en/

- 6. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare. Person-centred healthcare organisations. Sydney: ACSQHC; 2018. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/patient-and-consumer-centred-care/person-centred-organisations/

- 7. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare. National Quality and Safety Health Service Standards Second edition. Sydney: ACSQHC; 2017. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/National-Safety-and-Quality-Health-Service-Standards-second-edition.pdf .

- 8. Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia. Registered Nurse Standards of Practice. Sydney: NMBA; 2016. https://www.nursingmidwiferyboard.gov.au/Codes-Guidelines-Statements/Professional-standards/registered-nurse-standards-for-practice.aspx

- 10. Broome ME Integrative literature reviews for the development of concepts. In Rodgers BL, Knafl KA, editors. Concepts Development in Nursing. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co; 1993. p.231–250.

- 12. Rogers RR. On becoming a person. New York: Houghton Mifflin; 1995.

- 15. Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A new health system for the 21st Century. Washington: IOM; 2001. https://www.med.unc.edu/pediatrics/quality/documents/crossing-the-quality-chasm .

- 18. Nolan MR, Brown J, Davies S, Nolan J, Keady J. The Senses Framework: improving care or older people through relationship-centred approach: Getting research into practice [Internet]. Sheffield: 2006. http://shura.shu.ac.uk/280/1/PDF_Senses_Framework_Report.pdf

- 19. Brooker D. Person-Centred Dementia Care: Making Services Better. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2007.

- 20. National Health Service (NHS). The 6 Cs. London: NHS; 2016. https://www.england.nhs.uk/leadingchange/about/the-6cs/

- 21. Johns C. The Burford NDU model: Caring in practice. Cambridge: Oxford; 1994.

- 25. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. Systematic Review. Oxford: CASP; 2018. https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Systematic-Review-Checklist-2018_fillable-form.pdf

- 26. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. Qualitative research. Oxford: CASP; 2018. https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf

- 45. Kim HS. Five Dimensions of Nursing Practice. In: Kim HS. The Essence of Nursing Practice: Philosophy and Perspective. New York: Springer publishing company; 2015. p. 81–102

- 49. Calder R, Dunkin R, Rochford C, Nichols T. Australian Health Services: too complex to navigate. A review of the national reviews of Australia’s health service arrangements. Melbourne: Australian Health Policy Collaboration; 2019. https://www.vu.edu.au/sites/default/files/australian-health-services-too-complex-to-navigate.pdf

- 50. Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development. Heath Policy Overview Health Policy Australia. Paris: OECD; 2015. http://www.oecd.org/australia/Health-Policy-in-Australia-December-2015.pdf

- 52. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare. Australian Charter of Healthcare Rights. Sydney: ACSQHC; 2008. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/australian-charter-healthcare-rights

- 53. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Potentially preventable hospitalisations in Australia by small geographic area. Canberra: AIHW; 2019. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/primary-health-care/potentially-preventable-hospitalisations/contents/overview

- 54. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Healthcare Agreement. Canberra: AIHW; 2019. https://meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/download.phtml?customDownloadType=mrIndicatorSetAdvanced&itemIds%5B%5D=698954&shortNames=long&includeRMA=0&userFriendly=userFriendly&form=long&media=pdf

Domain 2: Person-Centered Care

Descriptor: Person-centered care focuses on the individual within multiple complicated contexts, including family and/or important others. Person-centered care is holistic, individualized, just, respectful, compassionate, coordinated, evidence-based, and developmentally appropriate. Person-centered care builds on a scientific body of knowledge that guides nursing practice regardless of specialty or functional area.

Contextual Statement: Person-centered care is the core purpose of nursing as a discipline. This purpose intertwines with any functional area of nursing practice, from the point of care where the hands of those that give and receive care meet, to the point of systems-level nursing leadership. Foundational to person-centered care is respect for diversity, differences, preferences, values, needs, resources, and the determinants of health unique to the individual. The person is a full partner and the source of control in team-based care. Person-centered care requires the intentional presence of the nurse seeking to know the totality of the individual’s lived experiences and connections to others (family, important others, community). As a scientific and practice discipline, nurses employ a relational lens that fosters mutuality, active participation, and individual empowerment. This focus is foundational to educational preparation from entry to advanced levels irrespective of practice areas.

With an emphasis on diversity, equity, and inclusion, person-centered care is based on best evidence and clinical judgment in the planning and delivery of care across time, spheres of care, and developmental levels. Contributing to or making diagnoses is one essential aspect of nursing practice and critical to an informed plan of care and improving outcomes of care (Olson et al., 2019). Diagnoses at the system-level are equally as relevant, affecting operations that impact care for individuals. Person-centered care results in shared meaning with the healthcare team, recipient of care, and the healthcare system, thus creating humanization of wellness and healing from birth to death.

Search for Resources

Entry-Level Domain 2 Competencies

2.1 Engage with the Individual in establishing a caring relationship.

2.1a Demonstrate qualities of empathy.

2.1b Demonstrate compassionate care.

2.1c Establish mutual respect with the individual and family.

2.2 Communicate effectively with individuals.

2.2a Demonstrate relationship-centered care.

2.2b Consider individual beliefs, values, and personalized information in communications.

2.2c Use a variety of communication modes appropriate for the context.

2.2d Demonstrate the ability to conduct sensitive or difficult conversations.

2.2e Use evidence-based patient teaching materials, considering health literacy, vision, hearing, and cultural sensitivity.

2.2f Demonstrate emotional intelligence in communications.

2.3 Integrate assessment skills in practice.

2.3a Create an environment during assessment that promotes a dynamic interactive experience.

2.3b Obtain a complete and accurate history in a systematic manner.

2.3c Perform a clinically relevant, holistic health assessment.

2.3d Perform point of care screening/diagnostic testing (e.g. blood glucose, PO2, EKG).

2.3e Distinguish between normal and abnormal health findings.

2.3f Apply nursing knowledge to gain a holistic perspective of the person, family, community, and population.

2.3g Communicate findings of a comprehensive assessment.

2.4 Diagnose actual or potential health problems and needs.

2.4a Synthesize assessment data in the context of the individual’s current preferences, situation, and experience.

2.4b Create a list of problems/health concerns.

2.4c Prioritize problems/health concerns.

2.4d Understand and apply the results of social screening, psychological testing, laboratory data, imaging studies, and other diagnostic tests in actions and plans of care.

2.4e Contribute as a team member to the formation and improvement of diagnoses.

2.5 Develop a plan of care.

2.5a Engage the individual and the team in plan development.

2.5b Organize care based on mutual health goals.

2.5c Prioritize care based on best evidence.

2.5d Incorporate evidence-based intervention to improve outcomes and safety.

2.5e Anticipate outcomes of care (expected, unexpected, and potentially adverse).

2.5f Demonstrate rationale for plan.

2.5g Address individuals’ experiences and perspectives in designing plans of care.

2.6 Demonstrate accountability for care delivery.

2.6a Implement individualized plan of care using established protocols.

2.6b Communicate care delivery through multiple modalities.

2.6c Delegate appropriately to team members.

2.6d Monitor the implementation of the plan of care.

2.7 Evaluate outcomes of care.

2.7a Reassess the individual to evaluate health outcomes/goals.

2.7b Modify plan of care as needed.

2.7c Recognize the need for modifications to standard practice.

2.8 Promote self-care management.

2.8a Assist the individual to engage in self-care management.

2.8b Employ individualized educational strategies based on learning theories, methodologies, and health literacy.

2.8c Educate individuals and families regarding self-care for health promotion, illness prevention, and illness management.

2.8d Respect individuals and families’ self-determination in their healthcare decisions.

2.8e Identify personal, system, and community resources available to support self-care management.

2.9 Provide care coordination.

2.9a Facilitate continuity of care based on assessment of assets and needs.

2.9b Communicate with relevant stakeholders across health systems.

2.9c Promote collaboration by clarifying responsibilities among individual, family, and team members.

2.9d Recognize when additional expertise and knowledge is needed to manage the patient.

2.9e Provide coordination of care of individuals and families in collaboration with care team.

Advanced-Level Domain 2 Competencies

2.1d Promote caring relationships to effect positive outcomes.

2.1e Foster caring relationships.

2.2g Demonstrate advanced communication skills and techniques using a variety of modalities with diverse audiences.

2.2h Design evidence-based, person-centered engagement materials.

2.2i Apply individualized information, such as genetic/genomic, pharmacogenetic, and environmental exposure information in the delivery of personalized health care.

2.2j Facilitate difficult conversations and disclosure of sensitive information.

2.3h Demonstrate that one’s practice is informed by a comprehensive assessment appropriate to the functional area of advanced nursing practice.

2.4f Employ context driven, advanced reasoning to the diagnostic and decision-making process.

2.4g Integrate advanced scientific knowledge to guide decision making.

2.5h Lead and collaborate with an interprofessional team to develop a comprehensive plan of care.

2.5i Prioritize risk mitigation strategies to prevent or reduce adverse outcomes.

2.5j Develop evidence-based interventions to improve outcomes and safety.

2.5k Incorporate innovations into practice when evidence is not available.

2.6e Model best care practices to the team.

2.6f Monitor aggregate metrics to assure accountability for care outcomes.

2.6g Promote delivery of care that supports practice at the full scope of education.

2.6h Contribute to the development of policies and processes that promote transparency and accountability.

2.6i Apply current and emerging evidence to the development of care guidelines/tools.

2.6j Ensure accountability throughout transitions of care across the health continuum.

2.7d Analyze data to identify gaps and inequities in care and monitor trends in outcomes.

2.7e Monitor epidemiological and system-level aggregate data to determine healthcare outcomes and trends.

2.7f Synthesize outcome data to inform evidence-based practice, guidelines, and policies.

2.8f Develop strategies that promote self-care management.

2.8g Incorporate the use of current and emerging technologies to support self-care management.

2.8h Employ counseling techniques, including motivational interviewing, to advance wellness and self-care management.

2.8i Evaluate adequacy of resources available to support self-care management.

2.8j Foster partnerships with community organizations to support self-care management.

2.9f Evaluate communication pathways among providers and others across settings, systems, and communities.

2.9g Develop strategies to optimize care coordination and transitions of care.

2.9h Guide the coordination of care across health systems.

2.9i Analyze system-level and public policy influence on care coordination.

2.9j Participate in system-level change to improve care coordination across settings.

The Person-Centred Nursing Framework

- First Online: 27 April 2021

Cite this chapter

- Brendan McCormack 4 &

- Tanya McCance 5

9258 Accesses

9 Citations

In this chapter, the Person-centred Nursing Framework developed by McCormack and McCance [1, 2] will be described, and an updated framework will be presented. This will be placed in the context of the origins of the framework, which are founded on the concepts of caring and person-centredness. The evolution of the framework will be discussed, highlighting the changes over time that have characterised its development. The position of the Person-centred Nursing Framework as a middle-range theory will be explored and placed in the context of nursing theory development as a basis for practice. Finally, we will illustrate the centrally of the framework to knowledge generation that demonstrates a strong relationship between the theory, practice and research of person-centred practice.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Person-Centered Nursing and Other Health Professions

Person-Centred Care, Theory, Operationalisation and Effects

The Concept of Individualised Care

McCormack B, McCance TV. Development of a framework for person-centred nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56(5):1–8.

Article Google Scholar

McCormack B, McCance T. Person-centred nursing: theory and practice. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell; 2010.

Book Google Scholar

Gadamar HG. Truth and method. New York: Crossroad; 1989.

Google Scholar

McCormack B. Negotiating partnerships with older people—a person-centred approach. Basingstoke: Ashgate; 2001.

McCormack B. A conceptual framework for person-centred practice with older people. Int J Nurs Pract. 2003;9:202–9.

Heidegger M. Being and time. Oxford: Blackwell; 2005.

McCance TV. Caring in nursing practice: the development of a conceptual framework. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2003;17(2):101–16.

McCormack B, McCance T, Slater P, McCormick J, McArdle C, Dewing J. Person-centred outcomes and cultural change. In: Manley K, McCormack B, Wilson V, editors. International practice development in nursing and healthcare. Oxford: Blackwell; 2008. p. 189–214.

Fawcett J. Analysis and evaluation of conceptual models of nursing. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis; 1995.

Lynch B, McCance T, McCormack B, Brown D. The development of the person-centred situational leadership framework: revealing the being of person-centredness in nursing homes. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27:427–40.

McCance T, Gribben B, McCormack B, Laird E. Promoting person-centred practice within acute care: the impact of culture and context on a facilitated practice development programme. Int Pract Dev J. 2013;3(1):2.

Buckley C, McCormack B, Ryan A. Valuing narrative in the care of older people. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(17–18):565–2577.

McCormack B, McCance T. United Kingdom: the person-centred nursing model. In: Fitzpatrick JJ, Whall AL, editors. Conceptual models of nursing: global perspectives. New Jersey: Pearson Education; 2016.

McCormack B, McCance T. Person-centred nursing and health care—theory and practice. Oxford: Wiley Publishing; 2017.

Slater P, McCance T, McCormack B. Exploring person-centred practice within acute hospital settings. Int Pract Dev J. 2015. http://www.fons.org/library/journal/volume5-person-centredness-suppl/article9 .

McCormack B, Dewing J, McCance T. Developing person-centred care: addressing contextual challenges through practice development. Online J Issues Nurs. 2011;16(2):3.

PubMed Google Scholar

McCormack B, Dewing J, Breslin L, Tobin C, Manning M, Coyne-Nevin A, et al. The implementation of a model of person-centred practice in older person settings: final report. Dublin: Office of the Nursing Services Director, Health Services Executive; 2010.

Gadow S. Existential advocacy: philosophical foundations of nursing. In: Spicker SF, Gadow S, editors. Nursing: images and ideals—opening dialogue with the humanities. New York: Springer; 1980.

Brown D, McCormack B. Exploring psychological safety as a component of facilitation within the Promoting Action Research in Health Services (PARiHS) framework through the lens of pain management practices with older people. J Adv Nurs. 2016;25:2921–32. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/jocn.13348 .

Carmona M. Place value: place quality and its impact on health, social, economic and environmental outcomes. J Urban Des. 2019;24(1):1–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2018.1472523 .

Seedhouse D. Health: the foundations for achievement. London: Wiley; 1986.

Titchen A, McCormack B, with Tyagi V. Dancing the mandalas of critical creativity in nursing and healthcare . Centre for Person-centred Practice Research, Queen Margaret University Edinburgh; 2020. https://www.cpcpr.org/critical-creativity .

Mekki TE, Øye C, Kristensen BM, Dahl H, Haaland A, Aas Nordin K, Strandos MR, Terum TM, Ydstebø AE, McCormack B. The inter-play between facilitation and context in the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services framework: a qualitative exploratory implementation study embedded in a cluster randomised controlled trial to reduce restraint in nursing homes. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73(11):2622–32.

Laird L, McCance T, McCormack B, Gribben B. Patients’ experiences of in-hospital care when nursing staff were engaged in a practice development programme to promote person-centredness: a narrative analysis study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(9):1454–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.05.002 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

New South Wales Health 2012 Essentials of care program in NSW, Australia. https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/nursing/culture/Documents/essentials-of-care-program-overview.pdf . Accessed Aug 2020.

Slater P, Bunting B, McCormack B. The development and pilot testing of an instrument to measure nurses’ working environment: the nursing context index. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2009;6(3):173–82.

McCormack B, McCarthy G, Wright J, Slater P, Coffey A. Development and testing of the context assessment index. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2009;6(1):27–35.

Slater P, McCance TV, McCormack B. The development and testing of the Person-centred Practice Inventory—Staff (PCPI-S). Int J Qual Health Care. 2017;29(4):541–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzx066 .

Wilson V, Dewing J, Cardiff S, Mekki TE, Øye C, McCance T. A person-centred observational tool: devising the Workplace Culture Critical Analysis Tool®. Int Pract Dev J. 2020;10:1. https://doi.org/10.19043/ipdj.101.003 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

McCance TV, Telford L, Wilson J, MacLeod O, Dowd A. Identifying key performance indicators for nursing and midwifery care using a consensus approach. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(7&8):1145–54.

McCance T, Hastings J, Dowler H. Evaluating the use of key performance indicators to evidence the patient experience. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24:3084–94.

McCance T, Wilson V. Using person-centred key performance indicators to improve paediatric services: an international venture. Int Pract Dev J. 2015;5:8. https://www.fons.org/library/journal/volume5-person-centredness-suppl/article8 .

McCance T, Wilson V, Korman K. Paediatric International Nursing Study: using person-centred key performance indicators to benchmark children’s services. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(13–14):2018–27.

Knowles M. The adult learner: a neglected species. 3rd ed. Houston: Gulf Publishing; 1984.

O’Donnell D, McCormack B, McCance T, McIlfatrick S. A meta-synthesis of person-centredness in nursing curricula. Int Pract Dev J. 2020;10(2)(special issue). https://doi.org/10.19043/ipdj.10Suppl2.002 .

McCormack B, Dewing J. International Community of Practice for Person-centred Practice: position statement on person-centredness in health and social care Curricula. Int Pract Dev J. 2019;9(1):3. https://doi.org/10.19043/ipdj.91.003 .

Haraldsdottir E, Donaldson K, Lloyd A, McCormack B. Reaching for the rainbow: person-centred practice in palliative care. Int Pract Dev J. 2020;10(1):5. https://www.fons.org/Resources/Documents/Journal/Vol10No1/IPDJ_10_01_05.pdf.

McCormack B, Dickson C, Smith T, Ford H, Ludwig S, Moyes R, Lee L, Adam E, Paton T, Lydon B, Spiller J. ‘It’s a nice place, a nice place to be’. The story of a practice development programme to further develop person-centred cultures in palliative and end-of-life care. Int Pract Dev J. 2018;8(1):2. https://doi.org/10.19043/ipdj81.002 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Division of Nursing, School of Health Science, Queen Margaret University, Musselburgh, UK

Brendan McCormack

School of Nursing, Ulster University, Newtownabbey, Northern Ireland

Tanya McCance

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Brendan McCormack .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Division of Nursing - School of Health Science, Queen Margaret University, Musselburgh, UK

School of Nursing, University of Ulster, Newtownabbey, UK

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

McCormack, B., McCance, T. (2021). The Person-Centred Nursing Framework. In: Dewing, J., McCormack, B., McCance, T. (eds) Person-centred Nursing Research: Methodology, Methods and Outcomes. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27868-7_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27868-7_2

Published : 27 April 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-27867-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-27868-7

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 03 September 2021

A literature-based study of patient-centered care and communication in nurse-patient interactions: barriers, facilitators, and the way forward

- Abukari Kwame 1 &

- Pammla M. Petrucka 2

BMC Nursing volume 20 , Article number: 158 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

399k Accesses

179 Citations

97 Altmetric

Metrics details

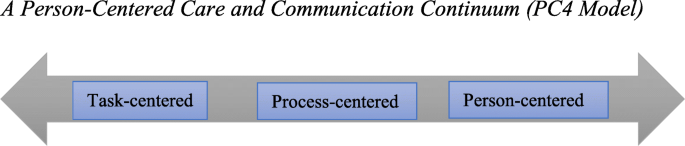

Providing healthcare services that respect and meet patients’ and caregivers’ needs are essential in promoting positive care outcomes and perceptions of quality of care, thereby fulfilling a significant aspect of patient-centered care requirement. Effective communication between patients and healthcare providers is crucial for the provision of patient care and recovery. Hence, patient-centered communication is fundamental to ensuring optimal health outcomes, reflecting long-held nursing values that care must be individualized and responsive to patient health concerns, beliefs, and contextual variables. Achieving patient-centered care and communication in nurse-patient clinical interactions is complex as there are always institutional, communication, environmental, and personal/behavioural related barriers. To promote patient-centered care, healthcare professionals must identify these barriers and facitators of both patient-centered care and communication, given their interconnections in clinical interactions. A person-centered care and communication continuum (PC4 Model) is thus proposed to orient healthcare professionals to care practices, discourse contexts, and communication contents and forms that can enhance or impede the acheivement of patient-centered care in clinical practice.

Peer Review reports

Providing healthcare services that respect and meet patients’ and their caregivers’ needs are essential in promoting positive care outcomes and perceptions of quality of care, thus constituting patient-centered care. Care is “a feeling of concern for, or an interest in, a person or object which necessitates looking after them/it” [ 1 ]. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) noted that to provide patient-centered care means respecting and responding to individual patient’s care needs, preferences, and values in all clinical decisions [ 2 ]. In nursing care, patient-centered care or person-centered care must acknowledge patients’ experiences, stories, and knowledge and provide care that focuses on and respects patients’ values, preferences, and needs by engaging the patient more in the care process [ 3 ]. Healthcare providers and professionals are thus required to fully engage patients and their families in the care process in meaningful ways. The IOM, in its 2003 report on Health Professions Education , recognized the values of patient-centered care and emphasized that providing patient-centered care is the first core competency that health professionals’ education must focus on [ 4 ]. This emphasis underscored the value of delivering healthcare services according to patients’ needs and preferences.

Research has shown that effective communication between patients and healthcare providers is essential for the provision of patient care and recovery [ 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ]. Madula et al. [ 6 ], in a study on maternal care in Malawi, noted that patients reported being happy when the nurses and midwives communicated well and treated them with warmth, empathy, and respect. However, other patients said poor communication by nurses and midwives, including verbal abuse, disrespect, or denial from asking questions, affected their perceptions of the services offered [ 6 ]. Similarly, Joolaee et al. [ 9 ] explored patients’ experiences of caring relationships in an Iranian hospital where they found that good communication between nurses and patients was regarded as “more significant than physical care” among patients.