To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, developing a robust case study protocol.

Management Research Review

ISSN : 2040-8269

Article publication date: 4 July 2023

Issue publication date: 11 January 2024

Case study research has been applied across numerous fields and provides an established methodology for exploring and understanding various research contexts. This paper aims to aid in developing methodological rigor by investigating the approaches of establishing validity and reliability.

Design/methodology/approach

Based on a systematic review of relevant literature, this paper catalogs the use of validity and reliability measures within academic publications between 2008 and 2018. The review analyzes case study research across 15 peer-reviewed journals (total of 1,372 articles) and highlights the application of validity and reliability measures.

The evidence of the systematic literature review suggests that validity measures appear well established and widely reported within case study–based research articles. However, measures and test procedures related to research reliability appear underrepresented within analyzed articles.

Originality/value

As shown by the presented results, there is a need for more significant reporting of the procedures used related to research reliability. Toward this, the features of a robust case study protocol are defined and discussed.

- Case study research

- Systematic literature review

Burnard, K.J. (2024), "Developing a robust case study protocol", Management Research Review , Vol. 47 No. 2, pp. 204-225. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-11-2021-0821

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2023, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

All feedback is valuable.

Please share your general feedback

Report an issue or find answers to frequently asked questions

Contact Customer Support

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Cardiovasc Echogr

- v.28(3); Jul-Sep 2018

How to Write a Research Protocol: Tips and Tricks

Matteo cameli.

Department of Cardiovascular Diseases, University of Siena, Siena, Italy

Giuseppina Novo

1 Biomedical Department of Internal Medicine and Medical Specialties, Cardiology Unit, University of Palermo, Palermo, Italy

Maurizio Tusa

2 Division of Cardiology, IRCCS Policlinico San Donato, Italy

Giulia Elena Mandoli

Giovanni corrado.

3 Department of Cardiology, Valduce Hospital, Como, Italy

Frank Benedetto

4 Division of Cardiology, Bianchi-Melacrino-Morelli Hospital, Reggio Calabria, Italy

Francesco Antonini-Canterin

5 High Specialization Rehabilitation Hospital, ORAS, Motta di Livenza, Treviso, Italy

Rodolfo Citro

6 Heart Department, University Hospital “San Giovanni di Dio e Ruggi D’Aragona”, Salerno, Italy

The first drafting of the protocol for a new research project should start from a solid idea with one or more of these goals:

- Overcoming the limits of the current knowledge in a determinate field with the aim of bridging a “knowledge gap”

- Bringing something new in a scarcely explored field

- Validating or nullifying previous results obtained in limited records by studies on a wider population.

A research proposal born with the intent to convince the others that your project is worthy and you are able to manage it with a complete and specific work plan. With a strong idea in mind, it is time to write a document where all the aspects of the future research project must be explained in a precise, understandable manner. This will successively help the researcher to present it and process and elaborate the obtained results.[ 1 ] The protocol manuscript should also underline both the pros and the potentialities of the idea to put it under a new light.[ 2 ]

Our paper will give the authors suggestions and advices regarding how to organize a research protocol, step by step [ Table 1 ].

Main sections and subsections in a complete research protocol

| Main investigator |

| Name |

| Address |

| Phone/fax |

| Number of involved centers (for multi-centric studies) |

| Indicate the reference center |

| Title of the study |

| Protocol ID (acronym) |

| Keywords (up to 7 specific keywords) |

| Rationale of the study (describe current scientific evidence in support of the research with a possible sub-section for the references) |

| Study design |

| Monocentric/multicentric |

| Perspective/retrospective |

| Controlled/uncontrolled |

| Open-label/single-blinded or double-blinded |

| Randomized/nonrandomized |

| parallel branches/ overlapped branches |

| Experimental/observational |

| Others |

| Primary objective |

| Endpoints (main primary and secondary endpoints to be listed) |

| Expected results |

| Analyzed criteria |

| Main variables/endpoints of the primary analysis |

| Main variables/endpoints of the secondary analysis |

| Safety variables |

| Quality of life (if applicable) |

| Health economy (if applicable) |

| Visits and examinations |

| Therapeutic plan and goals |

| Visits/controls schedule (also with graphics) |

| Comparison to treatment products (if applicable) |

| Dose and dosage for the whole time period |

| Formulation and power of the studied drugs |

| Method of administration of the studied drugs |

| Informed consent |

| Study population |

| Short description of the main inclusion and exclusion criteria |

| Sample size |

| Estimate of the duration of the study |

| Best supposed perspective |

| Safety advisory |

| Classification needed |

| Requested funds |

| Additional features |

| On the main concept of the study |

A research protocol must start from the definition of the coordinator of the whole study: all the details of the main investigator must be reported in the first paragraph. This will allow each participant to know who ask for in case of doubts or criticalities during the research. If the study will be multicentric, in the first section must be written also the number of the involved centers, each one possibly matched with the corresponding reference investigator.

Second section: Specific features of the research study

After completing the administrative details, the next step is to provide and extend title of the study: This is made for identifying the field of research and the aim of the study itself in a sort of brief summary of the research; the title must be followed by a unique acronym, like an ID of the protocol. If the protocol has been already exposed and approved by the Ethical Committee, it is appropriate to include also protocol number.

A list of 3–7 keywords must be listed to simplify the collocation of the protocol in its field of research, including, for example, disease, research tools, and analyzed parameters (e.g. three-dimensional echocardiography, right ventricle, end-stage heart failure, and prognosis).

The protocol must continue stating the research background that is the rational cause on the base on which the study is pursued. This section is written to answer some of these questions: what is the project about? What is already available in this field in the current knowledge? Why we need to overcome that data? and How will the community will from the present study?

As for an original research manuscript, the introduction to the project must include a brief review of the literature (with corresponding references). It is also fundamental to support the premises of the study, to underline the importance of the project in that particular time period and above all, of the materials and methods that will be employed. The rationale should accurately put in evidence the current lack in that field of scientific knowledge, following a precise, logical thread with concrete solutions regarding how to overcome the gaps and to conclude with the hypothesis of the project. A distinct paragraph can be dedicated to references, paying attention to select only the previous papers that can help the reader to focus the attention on the topic and to not excessively extend the list. In the references paragraph, the main studies regarding the object of the research but also state-of-art reviews updating the most recent discoveries in the field should be inserted.

The section should successively expose the study design: monocentric or multicentric, retrospective or prospective, controlled or uncontrolled, open-label or blinded, randomized or nonrandomized, and observational or experimental. It should also be explained why that particular design has been chosen.

At this point, the author must include the primary objective of the research, that is, the main goal of the study. This is a crucial part of the proposal and more than 4–5 aims should be avoided to do not reduce the accuracy of the project. Using verbs as “to demonstrate,” “to assess,” “to verify,” “to improve,” “to reduce,” and “to compare” help to give relevance to this section. Add also a description of the general characteristics of the population that will be enrolled in the study (if different subgroups are planned, the criteria on the base of which they will be divided should be specified); primary and secondary end-points, including all the variables that represent the measure of the objective (e.g., all-cause death, cardiovascular death, hospitalization, and side effects of a drug) follow in this section.

All the single parameters and variables that will be assessed during the study must be accurately and precisely listed along with the tools, the methods, the process schedule timing, and the technical details by which they will be acquired; Here, the author should explain how the Investigators who work in the other involved centers have to sent their results and acquired data to the Core Laboratory (e.g. by filled databases or by sending images).

A special attention must then be paid to clarify the planning of each examination the study patients will undergo: basal evaluation, potential follow-up schedule, treatment strategy plan, comparison between new and already-in-use drugs, dose and dosage of the treatment in case of a pharmacological study. This part can be enhanced by flowcharts or algorithms that allow a more immediate comprehension and interpretation of the study strategy.

This section may result more complete if one more subsection, illustrating the expected results, is included. Considering the idea at the base on the project, the endpoints and the pre-arranged objectives, the author can explain how its research project will

- Contribute to optimize the scientific knowledge in that specific field

- Give real successive implications in clinical practice

- Pave the way for future scientific research in the same or similar area of interest, etc.

The study population must be specified in detail, starting from inclusion criteria (including age and gender if it is planned to be restricted) and exclusion criteria: the more precise are the lists, the more accurate the enrollment of the subjects will be to avoid selection biases. This will also help to raise the success rate of the project and to reduce the risks of statistical error during the successive analysis of the data. The sample size should be planned and justified on the base of a statistic calculation considering the incidence and prevalence of the disease, frequency of use of a drug, etc., and possibly also indicating if the study considers a minimal or maximal number of subjects for each enrollment center (in case of multicentric studies).

This section of the protocol should end with some indications regarding timing and duration of the study: Starting and end of enrollment date, starting and end of inclusion date, potential frequency of control examinations, and timing of the analysis of the acquired data. If already settled, it can be useful to indicate also the type of statistical analysis that the investigators will apply to the data.

It is always necessary to prepare an informed consent to be proposed to the patient where premises, methods, and aims of the research together with advantages (e.g., some visits or diagnostic examinations for free) and possible risks derived from the participation to the study.

In this short section, various pieces of information regarding safety of the study must be added (a classification is fundamental in case of studies that expect the use of invasive procedures or drugs use). Usually, for nonobservational studies, an insurance coverage must be considered.

If the investigators have requested or plan to request funding or financial support, all the obtained resources must be listed to avoid conflicts of interest.

C ONCLUSION

Writing a complete and detailed document is a paramount step before starting a research projects. The protocol, as described in this paper, should be simply and correctly written but must clarify all the aspects of the protocol. The document could be divided into three different sessions to give all the parts the appropriate attention.

R EFERENCES

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Reasons to Submit

- About Journal of Surgical Protocols and Research Methodologies

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, contents of a research study protocol, conflict of interest statement, how to write a research study protocol.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Julien Al Shakarchi, How to write a research study protocol, Journal of Surgical Protocols and Research Methodologies , Volume 2022, Issue 1, January 2022, snab008, https://doi.org/10.1093/jsprm/snab008

- Permissions Icon Permissions

A study protocol is an important document that specifies the research plan for a clinical study. Many funders such as the NHS Health Research Authority encourage researchers to publish their study protocols to create a record of the methodology and reduce duplication of research effort. In this paper, we will describe how to write a research study protocol.

A study protocol is an essential part of a research project. It describes the study in detail to allow all members of the team to know and adhere to the steps of the methodology. Most funders, such as the NHS Health Research Authority in the United Kingdom, encourage researchers to publish their study protocols to create a record of the methodology, help with publication of the study and reduce duplication of research effort. In this paper, we will explain how to write a research protocol by describing what should be included.

Introduction

The introduction is vital in setting the need for the planned research and the context of the current evidence. It should be supported by a background to the topic with appropriate references to the literature. A thorough review of the available evidence is expected to document the need for the planned research. This should be followed by a brief description of the study and the target population. A clear explanation for the rationale of the project is also expected to describe the research question and justify the need of the study.

Methods and analysis

A suitable study design and methodology should be chosen to reflect the aims of the research. This section should explain the study design: single centre or multicentre, retrospective or prospective, controlled or uncontrolled, randomised or not, and observational or experimental. Efforts should be made to explain why that particular design has been chosen. The studied population should be clearly defined with inclusion and exclusion criteria. These criteria will define the characteristics of the population the study is proposing to investigate and therefore outline the applicability to the reader. The size of the sample should be calculated with a power calculation if possible.

The protocol should describe the screening process about how, when and where patients will be recruited in the process. In the setting of a multicentre study, each participating unit should adhere to the same recruiting model or the differences should be described in the protocol. Informed consent must be obtained prior to any individual participating in the study. The protocol should fully describe the process of gaining informed consent that should include a patient information sheet and assessment of his or her capacity.

The intervention should be described in sufficient detail to allow an external individual or group to replicate the study. The differences in any changes of routine care should be explained. The primary and secondary outcomes should be clearly defined and an explanation of their clinical relevance is recommended. Data collection methods should be described in detail as well as where the data will be kept secured. Analysis of the data should be explained with clear statistical methods. There should also be plans on how any reported adverse events and other unintended effects of trial interventions or trial conduct will be reported, collected and managed.

Ethics and dissemination

A clear explanation of the risk and benefits to the participants should be included as well as addressing any specific ethical considerations. The protocol should clearly state the approvals the research has gained and the minimum expected would be ethical and local research approvals. For multicentre studies, the protocol should also include a statement of how the protocol is in line with requirements to gain approval to conduct the study at each proposed sites.

It is essential to comment on how personal information about potential and enrolled participants will be collected, shared and maintained in order to protect confidentiality. This part of the protocol should also state who owns the data arising from the study and for how long the data will be stored. It should explain that on completion of the study, the data will be analysed and a final study report will be written. We would advise to explain if there are any plans to notify the participants of the outcome of the study, either by provision of the publication or via another form of communication.

The authorship of any publication should have transparent and fair criteria, which should be described in this section of the protocol. By doing so, it will resolve any issues arising at the publication stage.

Funding statement

It is important to explain who are the sponsors and funders of the study. It should clarify the involvement and potential influence of any party. The sponsor is defined as the institution or organisation assuming overall responsibility for the study. Identification of the study sponsor provides transparency and accountability. The protocol should explicitly outline the roles and responsibilities of any funder(s) in study design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing and dissemination of results. Any competing interests of the investigators should also be stated in this section.

A study protocol is an important document that specifies the research plan for a clinical study. It should be written in detail and researchers should aim to publish their study protocols as it is encouraged by many funders. The spirit 2013 statement provides a useful checklist on what should be included in a research protocol [ 1 ]. In this paper, we have explained a straightforward approach to writing a research study protocol.

None declared.

Chan A-W , Tetzlaff JM , Gøtzsche PC , Altman DG , Mann H , Berlin J , et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials . BMJ 2013 ; 346 : e7586 .

Google Scholar

- conflict of interest

- national health service (uk)

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| January 2022 | 201 |

| February 2022 | 123 |

| March 2022 | 271 |

| April 2022 | 354 |

| May 2022 | 429 |

| June 2022 | 380 |

| July 2022 | 405 |

| August 2022 | 560 |

| September 2022 | 539 |

| October 2022 | 690 |

| November 2022 | 671 |

| December 2022 | 609 |

| January 2023 | 872 |

| February 2023 | 1,165 |

| March 2023 | 1,277 |

| April 2023 | 1,183 |

| May 2023 | 1,292 |

| June 2023 | 1,117 |

| July 2023 | 1,040 |

| August 2023 | 936 |

| September 2023 | 941 |

| October 2023 | 1,028 |

| November 2023 | 993 |

| December 2023 | 910 |

| January 2024 | 1,251 |

| February 2024 | 1,051 |

| March 2024 | 1,411 |

| April 2024 | 991 |

| May 2024 | 895 |

| June 2024 | 677 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- JSPRM Twitter

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 2752-616X

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press and JSCR Publishing Ltd

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- No results found

THE CASE STUDY PROTOCOL

Research methodology.

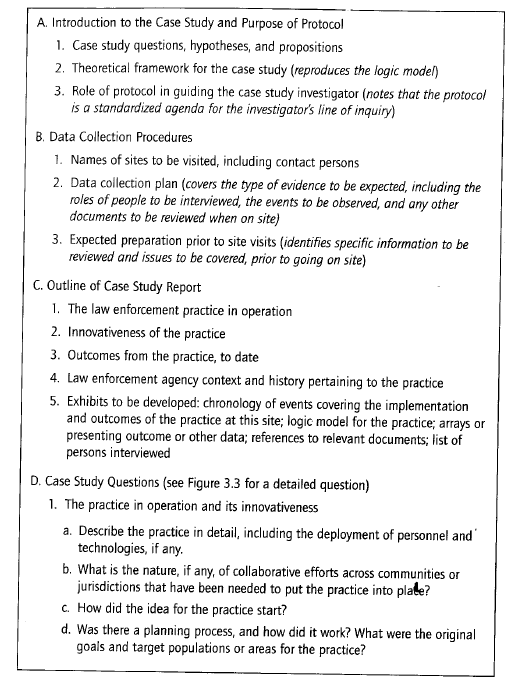

The case study protocol defines the procedures and general rules to be followed using the protocol which is different from a survey questionnaire” (Yin, 2009, p. 79). The case study protocol and a survey questionnaire are both directed at a single data point, whether it’s a single case or a single respondent (Yin, 2009). A case study protocol is always needed when

performing a multiple-case study (Yin, 2009). The protocol is a major way of increasing the

reliability of case study research and is intended to guide the researcher in carrying out data

collection from a single case (Yin, 2009). A case study protocol should have at least the following sections (Yin, 2009, p. 81):

1. Overview of the case study project (project objectives and auspices, case study issues, and relevant readings about the topic being investigated).

2. Field procedures (presentation of credentials, access to the case study “sites”, language pertaining to the protection of human subjects, sources of data, and procedural reminders).

3. Field procedures (the specific questions that the case study must keep in mind in collecting data, “table shells” for specific arrays of data, and the potential sources of information for answering each question …).

4. Investigator guide for the case study report (outline, format of the data, use and presentation of other documentation, and bibliographical information).

The importance of the protocol helps the researcher to remain focused on the topic and problem areas. This intuitive knowledge of the context and perspective will guide the researcher in the search for supporting information. By writing an overview of the case study, the researcher allows potential knowledge seeker to capitalize on the products of the case study and understand beforehand, the intent and depth of the case study research. There are also potential guidelines for field procedure. A researcher’s “field procedure of the protocol need to emphasize the major tasks in collecting data, including gaining access to key organizations or interviewees” (Yin, 2009, p. 85):

1. Having sufficient resources while in the field – including a personal computer, writing instruments, paper, paper clips, and a pre-established, quiet place to write notes privately.

2. Developing a procedure for calling for assistance and guidance, if needed, from other case study investigators or colleagues.

3. Making a clear schedule of the data collection activates that are expected to be completed within specified periods of time.

4. Providing for unanticipated events, including changes in the availability of interviewees as well as changes in the mood and motivation of the case study investigator.

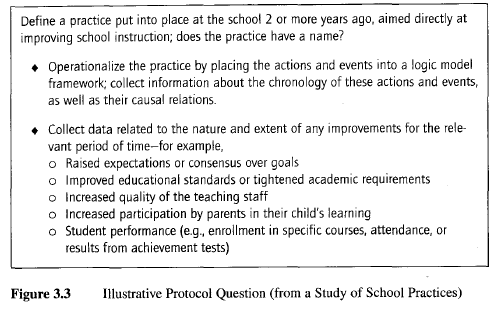

“The heart of the protocol is a set of substantive questions reflecting your actual line of inquiry” (Yin, 2009, p. 86). Each question should be “posed to you, the investigator, not to an

interviewee” and linked to a source of evidence (Yin, 2009, p. 86). Each question of this protocol should reflect a specific type/level potentially categorized by Yin’s five levels of questions below (Yin, 2009, p. 86):

1. Level 1: question asked of specific interviewees.

2. Level 2: questions asked of the individual case (these are the questions in the case study protocol to be answered by the investigator during a single case, even when the single case is part of a larger, multiple-case study).

3. Level 3: questions asked of the pattern of findings across multiple cases.

4. Level 4: questions asked of the entire study – for example, calling the information beyond the case study evidence and including other literature or published data that may have been reviewed.

5. Level 5: normative questions about policy recommendations and conclusions, going beyond the narrow scope of study.

“The questions should cater to the unit of analysis of the case study, which may be at a different level from the unit of data collection of the case study” (Yin, 2009, p. 88). “The common

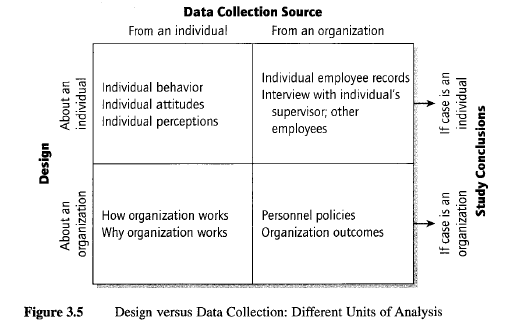

confusion begins because the data collection sources may be individual people (e.g., interviews with individuals), whereas the unit of analysis of your case study may be a collective (e.g., the organization to which the individual belongs) - a frequent design when the case is about the organization, community, or social group” (Yin, 2009, p. 88). Table 6 below illustrates design verses data collection using different units of analysis:

Individual behavior Individual attitudes Individual perceptions

Individual employee records Interview with individual’s supervisor; other employees

How organization works

Why organization works Personnel policiesOrganization outcomes

Abo ut a n indi vidua l Abo ut a n or ga ni za tion De sig n

From an individual From an organization

Data Collection Source

Table 6: Design verses Data Collected

Table 6 above, Design verses Data Collection, helps the researcher to identify exactly what data is desired and ensures parallel information is collected from different sites as during a multiple case study (Yin, 2009, p. 89). The researcher should include an outline in the protocol to guide

in the collection, presentation, and formatting of data (Yin, 2009). This rigor allows other researchers to follow the case (Yin, 2009). The researcher may choose a pilot case to discover unforeseen issues or challenges (Yin, 2009). The protocol helps align the researcher’s data collection efforts.

The case study protocol defines the procedures and general rules to be followed using the protocol (Yin, 2009). Yin (2009) reminds the researcher that the protocol is a major way of increasing the reliability of case study research and is intended to guide the researcher in carrying out data collection from a single case. The case study protocol should contain at minimum the following sections (Yin, 2009): (1) Overview of the case study project; (2) Field procedures (credentials); (3) Field procedures (questions); and (4) a form of investigator guide for the case study report. The importance of the protocol helps the researcher to remain focused on the topic and problem areas. Design verses Data Collection helps the researcher to identify exactly what data is desired and ensures parallel information is collected from different (Yin, 2009). The case study protocol is used in the collection of case study evidence as described in the next section.

- PROJECT MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS (PMS)

- PMS: PMBOK PERSPECTIVE

- CYBERNETICS: PRELUDE TO THE VSM

- VIABLE SYSTEM MODEL (VSM)

- ORIGINS OF THE VSM

- SYSTEM FOUR

- CASE STUDY RESEARCH

- COMPONENTS OF RESEARCH DESIGN

- CASE STUDY DESIGNS

- THE CASE STUDY PROTOCOL (You are here)

- COLLECTING CASE STUDY EVIDENCE

- FRAMEWORK DEVELOPMENT

- DATA COLLECTION STRATEGIES

- ROLE OF THE RESEARCHER

- PROJECT Q: A CASE STUDY

Related documents

Study protocol

Publishing study protocols in BMC Public Health is part of our commitment to improving research standards by promoting transparency, reducing publication bias, and enhancing the reproducibility of study design and analysis. We consider study protocols for proposed or ongoing prospective clinical research that provide a detailed account of the hypothesis, rationale and methodology of the study, and the associated ethical requirements. By publishing your protocol with us, it becomes a fully citable open-access article.

We evaluate study protocol submissions on a case-by-case basis and consider only those for proposed or ongoing studies that have not completed participant recruitment at the time of submission. We encourage authors to submit their study protocols well in advance of participant recruitment completion and confirm the study status within the cover letter.

Study protocols for pilot or feasibility studies are not considered, and authors are encouraged to submit the pilot results as a research article and the study protocol for the definitive study. Additionally, we may not consider study protocols where authors have other articles published or under consideration relating to the same protocol. Please note that study protocols for systematic reviews are not considered by the BMC Series journals.

If a proposed study protocol has obtained formal ethical approval and undergone independent peer-review from a major funding body, it will usually be considered for publication without further peer-review. Please ensure the Declarations section in your manuscript outlines the funding information, including whether it was peer reviewed and information about ethical approval. In some cases, the Editor may request to see the peer-review reports from the funder and/or may send the protocol for additional peer review.

Please note that study protocols without major external funding or ethics approval may not be considered for publication.

Protocols of randomized controlled trials should follow the SPIRIT guidelines and must have a trial registration number included in the last line of the abstract, as described in our editorial policies. Please provide a completed SPIRIT checklist as a supplementary file when submitting your protocol.

When conducting peer-review of study protocols, the intention is not to change the study design. Instead, we ask our reviewers to evaluate and report on the study's adequacy in testing the hypothesis, whether there is sufficient detail for replication or comparison, the appropriateness of the planned statistical analysis, and the acceptability of the writing.

The final decision on whether to consider a study protocol for publication will rest with the Editor, and appeals will not be considered.

To ensure a smooth submission process, please take note of the following before submitting:

- Confirm the status of your study within the cover letter.

- Ensure that the Declarations section is complete and contains ethical approval and funding information.

- For protocols describing clinical trials, provide a completed copy of the SPIRIT checklist as a supplementary file.

Professionally produced Visual Abstracts

BMC Public Health will consider visual abstracts. As an author submitting to the journal, you may wish to make use of services provided at Springer Nature for high quality and affordable visual abstracts where you are entitled to a 20% discount. Click here to find out more about the service, and your discount will be automatically be applied when using this link.

What we are looking for

The journal considers protocols for ongoing or proposed large-scale, prospective studies related to public health and public health management activities and submissions should provide a detailed account of the hypothesis, rationale and methodology of the study. We are particularly interested in protocols for public health interventions aimed at improving health outcomes of populations.

Protocols for clinical research will not be considered and should be submitted to the relevant BMC Series medical journal.

Preparing your manuscript

The information below details the section headings that you should include in your manuscript and what information should be within each section.

Please note that your manuscript must include a 'Declarations' section including all of the subheadings (please see below for more information).

The title page should:

- "A versus B in the treatment of C: a randomized controlled trial", "X is a risk factor for Y: a case control study", "What is the impact of factor X on subject Y: A systematic review"

- or for non-clinical or non-research studies: a description of what the article reports

- if a collaboration group should be listed as an author, please list the Group name as an author. If you would like the names of the individual members of the Group to be searchable through their individual PubMed records, please include this information in the “Acknowledgements” section in accordance with the instructions below

- Large Language Models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT , do not currently satisfy our authorship criteria . Notably an attribution of authorship carries with it accountability for the work, which cannot be effectively applied to LLMs. Use of an LLM should be properly documented in the Methods section (and if a Methods section is not available, in a suitable alternative part) of the manuscript

- indicate the corresponding author

The Abstract should not exceed 350 words. Please minimize the use of abbreviations and do not cite references in the abstract. The abstract must include the following separate sections:

- Background: the context and purpose of the study

- Methods: how the study will be performed

- Discussion: a brief summary and potential implications

- Trial registration: If your article reports the results of a health care intervention on human participants, it must be registered in an appropriate registry and the registration number and date of registration should be in stated in this section. If it was not registered prospectively (before enrollment of the first participant), you should include the words 'retrospectively registered'. See our editorial policies for more information on trial registration

Three to ten keywords representing the main content of the article.

The Background section should explain the background to the study, its aims, a summary of the existing literature and why this study is necessary or its contribution to the field.

Methods/Design

The methods section should include:

- the aim, design and setting of the study

- the characteristics of participants or description of materials

- a clear description of all processes, interventions and comparisons. Generic drug names should generally be used. When proprietary brands are used in research, include the brand names in parentheses

- the type of statistical analysis used, including a power calculation if appropriate.

This should include a discussion of any practical or operational issues involved in performing the study and any issues not covered in other sections.

List of abbreviations

If abbreviations are used in the text they should be defined in the text at first use, and a list of abbreviations should be provided.

Declarations

All manuscripts must contain the following sections under the heading 'Declarations':

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication, availability of data and materials, competing interests, authors' contributions, acknowledgements.

- Authors' information (optional)

Please see below for details on the information to be included in these sections.

If any of the sections are not relevant to your manuscript, please include the heading and write 'Not applicable' for that section.

Manuscripts reporting studies involving human participants, human data or human tissue must:

- include a statement on ethics approval and consent (even where the need for approval was waived)

- include the name of the ethics committee that approved the study and the committee’s reference number if appropriate

Studies involving animals must include a statement on ethics approval and for experimental studies involving client-owned animals, authors must also include a statement on informed consent from the client or owner.

See our editorial policies for more information.

If your manuscript does not report on or involve the use of any animal or human data or tissue, please state “Not applicable” in this section.

If your manuscript contains any individual person’s data in any form (including any individual details, images or videos), consent for publication must be obtained from that person, or in the case of children, their parent or legal guardian. All presentations of case reports must have consent for publication.

You can use your institutional consent form or our consent form if you prefer. You should not send the form to us on submission, but we may request to see a copy at any stage (including after publication).

See our editorial policies for more information on consent for publication.

If your manuscript does not contain data from any individual person, please state “Not applicable” in this section.

All manuscripts must include an ‘Availability of data and materials’ statement. Data availability statements should include information on where data supporting the results reported in the article can be found including, where applicable, hyperlinks to publicly archived datasets analysed or generated during the study. By data we mean the minimal dataset that would be necessary to interpret, replicate and build upon the findings reported in the article. We recognise it is not always possible to share research data publicly, for instance when individual privacy could be compromised, and in such instances data availability should still be stated in the manuscript along with any conditions for access.

Authors are also encouraged to preserve search strings on searchRxiv https://searchrxiv.org/ , an archive to support researchers to report, store and share their searches consistently and to enable them to review and re-use existing searches. searchRxiv enables researchers to obtain a digital object identifier (DOI) for their search, allowing it to be cited.

Data availability statements can take one of the following forms (or a combination of more than one if required for multiple datasets):

- The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the [NAME] repository, [PERSISTENT WEB LINK TO DATASETS]

- The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

- All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

- The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due [REASON WHY DATA ARE NOT PUBLIC] but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

- Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

- The data that support the findings of this study are available from [third party name] but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of [third party name].

- Not applicable. If your manuscript does not contain any data, please state 'Not applicable' in this section.

More examples of template data availability statements, which include examples of openly available and restricted access datasets, are available here .

BioMed Central strongly encourages the citation of any publicly available data on which the conclusions of the paper rely in the manuscript. Data citations should include a persistent identifier (such as a DOI) and should ideally be included in the reference list. Citations of datasets, when they appear in the reference list, should include the minimum information recommended by DataCite and follow journal style. Dataset identifiers including DOIs should be expressed as full URLs. For example:

Hao Z, AghaKouchak A, Nakhjiri N, Farahmand A. Global integrated drought monitoring and prediction system (GIDMaPS) data sets. figshare. 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.853801

With the corresponding text in the Availability of data and materials statement:

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the [NAME] repository, [PERSISTENT WEB LINK TO DATASETS]. [Reference number]

If you wish to co-submit a data note describing your data to be published in BMC Research Notes , you can do so by visiting our submission portal . Data notes support open data and help authors to comply with funder policies on data sharing. Co-published data notes will be linked to the research article the data support ( example ).

All financial and non-financial competing interests must be declared in this section.

See our editorial policies for a full explanation of competing interests. If you are unsure whether you or any of your co-authors have a competing interest please contact the editorial office.

Please use the authors initials to refer to each authors' competing interests in this section.

If you do not have any competing interests, please state "The authors declare that they have no competing interests" in this section.

All sources of funding for the research reported should be declared. If the funder has a specific role in the conceptualization, design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript, this should be declared.

The individual contributions of authors to the manuscript should be specified in this section. Guidance and criteria for authorship can be found in our editorial policies .

Please use initials to refer to each author's contribution in this section, for example: "FC analyzed and interpreted the patient data regarding the hematological disease and the transplant. RH performed the histological examination of the kidney, and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript."

Please acknowledge anyone who contributed towards the article who does not meet the criteria for authorship including anyone who provided professional writing services or materials.

Authors should obtain permission to acknowledge from all those mentioned in the Acknowledgements section.

See our editorial policies for a full explanation of acknowledgements and authorship criteria.

If you do not have anyone to acknowledge, please write "Not applicable" in this section.

Group authorship (for manuscripts involving a collaboration group): if you would like the names of the individual members of a collaboration Group to be searchable through their individual PubMed records, please ensure that the title of the collaboration Group is included on the title page and in the submission system and also include collaborating author names as the last paragraph of the “Acknowledgements” section. Please add authors in the format First Name, Middle initial(s) (optional), Last Name. You can add institution or country information for each author if you wish, but this should be consistent across all authors.

Please note that individual names may not be present in the PubMed record at the time a published article is initially included in PubMed as it takes PubMed additional time to code this information.

Authors' information

This section is optional.

You may choose to use this section to include any relevant information about the author(s) that may aid the reader's interpretation of the article, and understand the standpoint of the author(s). This may include details about the authors' qualifications, current positions they hold at institutions or societies, or any other relevant background information. Please refer to authors using their initials. Note this section should not be used to describe any competing interests.

Footnotes can be used to give additional information, which may include the citation of a reference included in the reference list. They should not consist solely of a reference citation, and they should never include the bibliographic details of a reference. They should also not contain any figures or tables.

Footnotes to the text are numbered consecutively; those to tables should be indicated by superscript lower-case letters (or asterisks for significance values and other statistical data). Footnotes to the title or the authors of the article are not given reference symbols.

Always use footnotes instead of endnotes.

Examples of the Vancouver reference style are shown below.

See our editorial policies for author guidance on good citation practice

Web links and URLs: All web links and URLs, including links to the authors' own websites, should be given a reference number and included in the reference list rather than within the text of the manuscript. They should be provided in full, including both the title of the site and the URL, as well as the date the site was accessed, in the following format: The Mouse Tumor Biology Database. http://tumor.informatics.jax.org/mtbwi/index.do . Accessed 20 May 2013. If an author or group of authors can clearly be associated with a web link, such as for weblogs, then they should be included in the reference.

Example reference style:

Article within a journal

Smith JJ. The world of science. Am J Sci. 1999;36:234-5.

Article within a journal (no page numbers)

Rohrmann S, Overvad K, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Jakobsen MU, Egeberg R, Tjønneland A, et al. Meat consumption and mortality - results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. BMC Medicine. 2013;11:63.

Article within a journal by DOI

Slifka MK, Whitton JL. Clinical implications of dysregulated cytokine production. Dig J Mol Med. 2000; doi:10.1007/s801090000086.

Article within a journal supplement

Frumin AM, Nussbaum J, Esposito M. Functional asplenia: demonstration of splenic activity by bone marrow scan. Blood 1979;59 Suppl 1:26-32.

Book chapter, or an article within a book

Wyllie AH, Kerr JFR, Currie AR. Cell death: the significance of apoptosis. In: Bourne GH, Danielli JF, Jeon KW, editors. International review of cytology. London: Academic; 1980. p. 251-306.

OnlineFirst chapter in a series (without a volume designation but with a DOI)

Saito Y, Hyuga H. Rate equation approaches to amplification of enantiomeric excess and chiral symmetry breaking. Top Curr Chem. 2007. doi:10.1007/128_2006_108.

Complete book, authored

Blenkinsopp A, Paxton P. Symptoms in the pharmacy: a guide to the management of common illness. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1998.

Online document

Doe J. Title of subordinate document. In: The dictionary of substances and their effects. Royal Society of Chemistry. 1999. http://www.rsc.org/dose/title of subordinate document. Accessed 15 Jan 1999.

Online database

Healthwise Knowledgebase. US Pharmacopeia, Rockville. 1998. http://www.healthwise.org. Accessed 21 Sept 1998.

Supplementary material/private homepage

Doe J. Title of supplementary material. 2000. http://www.privatehomepage.com. Accessed 22 Feb 2000.

University site

Doe, J: Title of preprint. http://www.uni-heidelberg.de/mydata.html (1999). Accessed 25 Dec 1999.

Doe, J: Trivial HTTP, RFC2169. ftp://ftp.isi.edu/in-notes/rfc2169.txt (1999). Accessed 12 Nov 1999.

Organization site

ISSN International Centre: The ISSN register. http://www.issn.org (2006). Accessed 20 Feb 2007.

Dataset with persistent identifier

Zheng L-Y, Guo X-S, He B, Sun L-J, Peng Y, Dong S-S, et al. Genome data from sweet and grain sorghum (Sorghum bicolor). GigaScience Database. 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.5524/100012 .

Figures, tables and additional files

See General formatting guidelines for information on how to format figures, tables and additional files.

Submit manuscript

Important information

Editorial board

For authors

For editorial board members

For reviewers

- Manuscript editing services

Annual Journal Metrics

2022 Citation Impact 4.5 - 2-year Impact Factor 4.7 - 5-year Impact Factor 1.661 - SNIP (Source Normalized Impact per Paper) 1.307 - SJR (SCImago Journal Rank)

2023 Speed 32 days submission to first editorial decision for all manuscripts (Median) 173 days submission to accept (Median)

2023 Usage 24,332,405 downloads 24,308 Altmetric mentions

- More about our metrics

Peer-review Terminology

The following summary describes the peer review process for this journal:

Identity transparency: Single anonymized

Reviewer interacts with: Editor

Review information published: Review reports. Reviewer Identities reviewer opt in. Author/reviewer communication

More information is available here

- Follow us on Twitter

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Corpus ID: 39692556

Designing a Case Study Protocol for Application in IS Research

- Hilangwa Maimbo , G. Pervan

- Published in Pacific Asia Conference on… 2005

- Computer Science

Figures and Tables from this paper

87 Citations

Guidelines for conducting and reporting case study research in software engineering, designing a case study template for theory building, integrating process inquiry and the case method in the study of is failure, an interpretive approach for data collection and analysis, exploratory case study research: outsourced project failure, using interpretive qualitative case studies for exploratory research in doctoral studies: a case of information systems research in small and medium enterprises, use of a quality monitoring methodology and platform in industrial software development – a feasibility study, it project portfolio assessment criteria: development and validation of a reference model, product derivation in practice, case studies research in the bioeconomy: a systematic literature review, 19 references, case study research: a multi‐faceted research approach for is.

- Highly Influential

Using case study research to build theories of IT implementation

Using a positivist case study methodology to build and test theories in information systems : illustrations from four exemplary studies, case study research: design and methods, a paradigmatic and methodological examination of information systems research from 1991 to 2001, research methods for business : a skill building approach (5th edition), combining is research methods: towards a pluralist methodology, on the use of construct reliability in mis research: a meta-analysis, is/it investment and organisational performance in the financial services sector: a credit union case study, developing an historical tradition in mis research, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Alternative Quality Management Systems for Highway Construction (2015)

Chapter: appendix c: case study protocol.

Below is the uncorrected machine-read text of this chapter, intended to provide our own search engines and external engines with highly rich, chapter-representative searchable text of each book. Because it is UNCORRECTED material, please consider the following text as a useful but insufficient proxy for the authoritative book pages.

APPENDIX C: CASE STUDY PROTOCOL C.1 Overview of Case Study Background Information Delivering highway projects using alternative project delivery methods demands a shift in the traditional agency quality assurance (QA) and quality control (QC) programs to accommodate the faster pace of design and construction as well as the redistribution of responsibilities among project stakeholders. Thus, the objectives of this research are to: ï§ Identify and understand alternative quality management systems ï§ Develop guidelines for their use in highway construction projects Alternative project delivery in highway construction often requires the application of alternative quality management systems that emphasize contractor quality control and quality assurance. These new systems allow owners to have confidence through a verification of contractor quality system processes. They also permit state transportation agencies (STAs) to satisfy due diligence requirements for federal- aid highway projects. For example, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 9001 quality management system regulates quality management at all levels from material suppliers through the contractors to owners. It requires a formal project performance evaluation after completion and uses that information to publish contractor performance ratings, which can then be used for future contractor prequalification. The U. S. Army Corps of Engineersâ quality management system relies on detailed guide specifications and rigorous on-site testing by contractors. The Corps has used alternative project delivery on a routine basis for over thirty years on a wide variety of heavy civil projects that include roads and bridges, and as a result, furnishes an excellent analog from which to draw lessons learned and best practices that apply to highway design and construction. Research is needed to provide guidance on the use of alternative quality management systems for highway construction projects using alternative delivery methods. This research needs to address the major quality issues associated with these methods including accelerated project timelines and the change of the designer-of-recordâs (DOR) contractual relationships with the owner to permit the required level of integration with the construction contractor. Issues of quality are further complicated by the addition of private funding of public projects in public-private partnerships (PPP). On these projects, an argument can be made that since the concessionaire is at risk for project performance the public agency has few if any reasons to involve itself in the quality management process. From current and past projects, there exists a limited but rapidly expanding body of experience associated with alternate methods of assuring quality. The purpose of this research is to bring together this relatively new body of experience and summarize it in one easily accessible reference treating the subject of QA in alternative projects. The case studies for this research will be used to learn how existing projects have managed quality in light of non-traditional delivery methods. After analyzing and comparing the various case studies, the information gathered will be condensed into working theories and used to modify what the authors of this research are calling the Integrated Quality Management Model (IQ2M) shown in Figure C1. The model was developed to be generic to all forms of project delivery and furnish a foundation for assigning quality management responsibilities between the owner, the designer, and the constructor. As such, it acts as a framework to structure the analysis of other 167

alternative project delivery quality systems that are common in highway construction and will be used in that manner in this research. Figure C1 â Integrated Quality Management Model (IQ2M) (adapted from Synthesis 376 (Gransberg and Molenaar 2008)) Relevant Definitions Across the highway construction and engineering industry, terms relating to quality often have multiple meanings that in some cases overlap with one another and in others supersede each other. To prevent confusion among several vital terms important to this study, the following definitions have been provided. These definitions are in accordance with the most recent issuance of the TRB Circular Glossary of Highway Quality Assurance Terms E-C137 and the NCHRP Synthesis 376. ⢠Quality: (1) The degree of excellence of a product or service. (2) The degree to which a product or service satisfies the needs of a specific customer. (3) The degree to which a product or service conforms to a given requirement. ⢠Quality Assurance (QA): All those planned and systematic actions necessary to provide confidence that a product or facility will perform satisfactorily in service. [QA addresses the overall problem of obtaining the quality of a service, product, or facility in the most efficient, economical, and satisfactory manner possible. Within this broad context, QA involves continued evaluation of the activities of planning, design, development of plans and specifications, advertising and awarding of contracts, construction, and maintenance, and the interactions of these activities.] TRB E-C074. 168

⢠Quality Control (QC): Also called process control. Those QA actions and considerations necessary to assess and adjust production and construction processes, so as to control the level of quality being produced in the end product. TRB E-C074. ⢠Quality Management (QM): The overarching system of policies and procedures that govern the performance of QA and QC activities. The totality of the effort to ensure quality in design and/or construction. ⢠Design-Bid-Build (DBB): A project delivery method where the design is completed either by in- house professional engineering staff or a design consultant before the construction contract is advertised. Also called the âtraditional method.â ⢠Design-Build (DB): A project delivery method where both the design and the construction of the project are simultaneously awarded to a single entity. ⢠Construction Manager-General Contractor (CMGC): A project delivery method where the contractor is selected during the design process and makes input to the design via constructability, cost engineering, and value analysis reviews. Once the design is complete, the same entity builds the projects as the general contractor. CMGC assumes that the contractor will self-perform a significant amount of the construction work. ⢠Construction Manager-at-Risk (CMR): A project delivery method similar to CMGC, but where the CM does not self-perform any of the construction work. ⢠Public Private Partnership (P3): A project delivery method where the agency contracts with a concessionaire organization to design, build, finance and operate an infrastructure facility for a defined extended period of time. ⢠Design deliverable: A product produced by the design-builderâs design team that is submitted for review to the agency (i.e. design packages, construction documents, etc.). ⢠Construction deliverable: A product produced by the design-builderâs construction team that is submitted for review to the agency (shop drawings, product submittals, etc.). Statement of Purpose The primary research objectives and research questions for this project are as follows: Objectives ⢠Document and categorize current practices and applications of Quality Management Systems (both traditional and alternative) in highway construction for all project delivery methods ⢠Explore how highway construction projects of all project delivery methods are effectively applying alternate quality management systems. (developing and implementing quality management systems) ⢠Identify benefits and limitations of the approaches 169

⢠Explore how to implement and apply quality management system for all methods of project delivery ⢠Produce a guidebook that will match appropriate quality management systems to selected alternative delivery methods o Describes the quality systems in the I2QM model o Discusses the barriers to each system o Gives guidance for individual roles in development and adoption of alt. quality management models in their agency ⢠Produce a research report that addresses the implications of adopting the guidelines and the barriers to implementation Research Questions 1. What is the fundamental definition of quality and what is the underlying purpose of a âquality program?â 2. How are projects using alternative delivery methods currently applying quality management systems? 3. What are the advantages and disadvantages to the contractor and the owner of alternative quality management systems relating to various project delivery alternatives? 4. What changes must be made to the baseline quality management system to adapt to evolving project delivery methods? Relevant Readings The protocol is based largely on the following documents and research reports. ï§ NCHRP Project 10-83 Proposal ï§ Coding Structure for NCHRP Project 10-83 ï§ TRB Circular E-C137 Glossary of Highway Quality Assurance Terms ï§ NCHRP Synthesis 376 ï§ NCHRP Synthesis 40-02 170

C.2 Field Procedures Project Researchers The following is a list of the project investigators and their contact information. ï§ Keith R. Molenaar, Ph.D. â Principal Investigator K. Stanton Lewis Chair and Associate Professor Construction Engineering and Management Program Department of Civil, Environmental, and Architectural Engineering University of Colorado at Boulder Campus Box 428, ECOT 643 Boulder, Colorado 80309-0428 Telephone: 303-735-4276 Facsimile: 303-492-7317 E-mail: [email protected] ï§ Douglas D. Gransberg, Ph.D., P.E. â Co-Principal Investigator Donald and Sharon Greenwood Chair and Professor of Construction Engineering Construction Engineering and Management Program Department of Civil, Construction, & Environmental Engineering Iowa State University 456 Town Engineering Ames, IA 50011 Telephone: 515-294-4148 E-mail: [email protected] ï§ David N. Sillars, Ph.D. â Co-Principal Investigator R.C Wilson Chair and Associate Professor Construction Engineering and Management Program Civil and Construction Engineering Oregon State University 220 Owen Hall Corvallis, Oregon 97331 Telephone: 541 737-8058 Fax: 541 737-3300 Email: [email protected] ï§ Elizabeth R. Kraft Graduate Student Construction Engineering and Management Program Department of Civil, Environmental, and Architectural Engineering University of Colorado at Boulder Campus Box 428 Boulder, Colorado 80309-0428 171

Telephone: Facsimile: Email: [email protected] ï§ Nickie West Graduate Student Construction Engineering and Management Program Department of Civil, Construction, & Environmental Engineering Iowa State University 456 Town Engineering Ames, IA 50011 Telephone: Facsimile: E-mail: [email protected] ï§ Landon S. Harman Graduate Student Construction Engineering and Management Program Civil and Construction Engineering Oregon State University 220 Owen Hall Corvallis, Oregon 97331 Telephone: Email: [email protected] Case Study delegation Note: The information in this section will not be available until after potential case studies have been identified and selected for study. When this information is available, this section will list who will be contacting each case study, what the scope of their questions/role will be, and who will be following up to garner additional information or thank participants for their time and effort. Case Study Identification and Schedule Case study project selection criteria In the original research proposal, it was stated that âa concerted effort will be made to select case study projects from transportation agencies that have mature experience with at least two different project delivery methods.â A total of 6 â 12 case studies will be performed with at least two of the case studies coming from a non-STA (USACE or the FTA). Additionally 2 pilot studies will be conducted and reviewed prior to the remaining studies to validate the case study protocol and data coding and to ensure that the research objectives will be met by the data collected. Potential case studies will be identified in Task 1 of the research as a part of the initial survey that aims to identify alternative quality management systems currently in use. The results of this survey will be used to populate an initial list of potential case studies. Case study project selection protocol will involve three tiers of project information that must be present to move a potential case study project into the 172

final list of candidates. The case study candidates will be forwarded to the NCHRP Panel for approval. The tiers are as follows: 1. Project Factor Information: This tier seeks to create a uniform set of data points for every case study project to ensure that trends or disconnects found during analysis can be uniformly mapped across the entire case study population (Yin 2008). Examples of this information are project location, size, major type of construction, initial and final budget amounts, initial and final delivery periods, delivery method, and other factors as required. 2. Project Quality Factor Information: This tier seeks to explicitly define the precise details of the system used to manage quality across the case study projectâs life cycle. Examples of this information are quality plans, quality organization composition, use of consultants for independent technical review or independent assurance/oversight, quality audits, division of quality management responsibility between the various stakeholder in the project and other factors as required. 3. Project Performance Information: This tier seeks to measure, if possible, the success of the quality management system employed in each project. It will use to the extent possible the stipulated performance metrics for scope, schedule, cost, quality and risk that were created for each case study project and will attempt to back-calculate performance metrics for common areas in all the projects to furnish a means of comparison and to identify and quantify the magnitude of the trends and disconnects in the case study project population. In addition to the above, a concerted effort will be made to select case study projects from transportation agencies that have mature experience with at least two different project delivery methods. The FHWA Report to Congress on Design-Build Effectiveness (2006) identified more than 30 state STAs that had been authorized to delivery design-build projects under SEP-14 authority. However, of that sample 12 had not completed a single design-build project, another eight had only completed one design-build project, and only six had finished more than five design-build projects. Thus, at that point in time, for this project delivery method the quality management systems of only six STAs could have been impacted by multiple project experiences. Since that time additional experience has been gained and NCHRP Synthesis 376 (2008) reported that four STAs had completed five to 10 design-build projects and nine had completed greater than 10. Thus, depending on the final criterion for design-build experience, as many as 13 STAs will have potential case study design-build projects that had quality management systems that were tailored for DB project delivery. That is not the case in construction management at risk. NCHRP Synthesis 40-02 (2010) reported that only Florida and Utah have completed more than a single construction management at risk project. Thus, case study projects with construction management at risk tailored quality management systems will have to come from those two STAs or from another mode of transportation such as transit. To summarize, the primary criterion for case study project selection will be the requirement to have come from an agency that has sufficient experience with a given project delivery method that the potential exists that the project was designed and built using a quality management system that was modified from the baseline design-bid-build system based on actual experience, using the USACE cyclical quality management system where quality management experience is fed back into the quality planning process to continuously improve the performance of the system itself. 173

This list of potential case studies created from the previously mentioned protocol will be supplemented by the Industry Advisory Board and the investigatorsâ industry contacts. The following three pieces of information will have been collected for each case study as a part of the survey in Task 1: (1) name and location of the project; (2) description of the project delivery, procurement, and contracting method in use; and (3) description of the quality management system. The goal for selecting the case studies will be to generate a cross section of cases that allow for analysis of the advantages and disadvantages of the quality management systems across the various project delivery method characteristics. To ensure that this goal is met, the following criteria will be placed on the case study selection will include: ⢠Quality management systems for design and construction; ⢠Quality assurance by all parties and independent auditors; ⢠Project quality assurance including independent verification and independent acceptance; ⢠Project delivery methods including design-build, construction manager-at-risk, and PPP; ⢠Procurement methods including best value, A+B, and qualifications-based selection; and ⢠Payment methods including incentives, lump sum, and guaranteed maximum price. Case study informant selection Once a case study project has been selected, several members of the team directly associated with creating and implementing the quality management plan will need to be interviewed. While many people are responsible for ensuring quality on a project during its lifecycle from conception through construction, we will seek to speak with â at a minimum â enough project team members to fully satisfy the research objectives and goals. This may include speaking with representatives from the ownerâs, designerâs, and contractorâs project team to develop a full picture of the quality management systems utilized on a project and their relation to each other. Potential interviewees include the following: ï§ Agency project manager, contracting manager, quality manager, etc. ï§ Project design manager, construction manager, design quality manager, construction quality manager, etc. ï§ Designer quality manager, project manager ï§ Contractor preconstruction manager, quality manager, project manager ï§ Third party quality assurance/quality control inspectors 174

Case Study Basic Data and Research Delegation Tables # Case Study Name Location Organization Contact (Information) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 # Case Study Name Contacted? Lead Investigato r Interview Type Intervie w Date Follow-up Date 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 175

# Case Study Name Materials/Documents Received 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 C.3 Requested Documents The following is a list of documents that will be requested. However, successful completion of the research study does not require that each of the documents is collected. A subset of these documents will likely be collected depending upon the unique attributes of the project being studied. ⢠Project RFP/RFQ ⢠Project RFP/RFQ Response ⢠Project Quality Management Plan ⢠Project Design Quality Plan ⢠Project Construction Quality Plan ⢠Agency/Company Quality Plan ⢠Project Quality Organizational Chart ⢠Copy of the contract with the engineer/contractor/consultant ⢠Organizational document that outlines its approach to quality assurance on project Case Study Questions This section seeks to formalize the interview questions asked of each case study to allow for easier comparison and analysis between case studies later on. Each interview will be unique and largely guided by the case study participants. To draw out the pertinent information, specific questions may be needed while some of the questions listed here may not be relevant. In modifying the protocol questions, generality should still be maintained so that the results can still be readily compared and categorized according to the coding structure. 176

Questionnaire The purpose of the questionnaire is to identify how state highway agencies (SHA) have implemented alternative QA programs and from that baseline, identify commonly used practices for dissemination and use by SHAs that intend to implement alternative procurement on future projects or alternative QA methods in their current program. The questionnaire consists of closed ended questions which will allow the researchers to perform a quantitative analysis. The data gathered by the questionnaire will be used to validate the case study findings. Ideally this questionnaire will be completed by the respondent prior to the interview. If it is not completed prior to the interview then it will be requested that the respondent complete it during the interview. The questionnaire is included in APPENDIX B. Background and Overall Quality Questions Background ï§ Background information to keep track of who we spoke with on each project ï§ Relevant prior experience used to potentially weight their opinions in later comparison 1. Name, occupation, employer 2. What are you current duties, especially related to QM, QA, QC? 3. Have you held any positions prior to your current position related to QM, QA, or QC? If so, please briefly list that information. 4. How long have you held your current position? 5. Have you worked on projects of different project delivery methods? If so specifically what project delivery methods do you have experience with? 6. How many years of experience do you with projects using baseline/DBB quality systems? 7. Name and location of the project for which you are answering project-specific questions Overall Understanding of Quality ï§ Examines the overall understanding of quality and the informants attitudes towards quality ï§ Establishes a baseline of traditional/DBB quality for comparison 8. How do you define project quality? 9. What is your understanding of the differences between quality management, quality assurance, and quality control? 10. In your experience, how has quality management been approached on a traditional/DBB project? ï§ Project by project basis? ï§ During the RFP process? ï§ Dictated by owner agency? If so, how is it dictated?? Specifications, performance⦠11. What are the critical elements/milestones of a quality management plan on a traditional/DBB project? 12. How are the quality roles and responsibilities divided on a traditional/DBB project? 13. In your experience, what quality systems/procedures have been successful on traditional/DBB projects? 177

14. What are some characteristics of a successful quality management plan, regardless of the project delivery method, contracting method, or procurement method? Organizational Questions ï§ Provides the needed categories and statistics (from the coding structure) to later sort and group the enterprise level QM information we receive. As not everyone selected for an interview will have answered the survey, these questions are not redundant Please answer the following questions related to quality management at different phases of a project for the organization you work for as a whole. Please be as thorough as possible when discussing what quality management systems may exist and be utilized within your organization. 15. Of the projects your organization designs/builds/owns what percent of the projects are managed using the following delivery methods: ï§ Design-bid-build (DBB): ______ ï§ Design-build (DB): _______ ï§ Construction Manager/General Contractor (CM/GC): _______ ï§ Public-Private-Partnership (PPP): _______ ï§ Other (please list): _______ 16. Of the projects your organization designs/builds/owns what percent of the projects are procured using the following procurement methods: ï§ Cost: ______ ï§ Best-value: _______ ï§ Qualifications: _______ ï§ Design: _________ 17. Of the projects your organization designs/builds/owns what percent of the projects utilize the following contract payment methods: ï§ Payment type: ________ ï§ Incentive type: ________ 18. If you work for a STA, what due diligence requirements must your organization meet in your state for quality assurance purposes on public projects? ï§ Please list applicable laws, reporting requirements, or processes required in your state ï§ Can you utilize new or alternative quality management practices that produce equal or superior quality projects to meet these requirements? If not, what legal barriers prevent you from doing so? ï§ If so, what steps are required to do this? Has this been done before? Please describe if it has. 19. Does your organization perform any in-house design work? ï§ On what percent of your projects do you perform in-house design? ï§ Do you have formal quality assurance systems in place for this process? ï§ If so, please describe this process. 20. Does your organization self-perform any construction work? ï§ On what percent of your projects do you self-perform some amount of construction? ï§ Do you have formal quality assurance systems in place for this process? ï§ If so, what are they? 178