Anthem for Doomed Youth Summary & Analysis by Wilfred Owen

- Line-by-Line Explanation & Analysis

- Poetic Devices

- Vocabulary & References

- Form, Meter, & Rhyme Scheme

- Line-by-Line Explanations

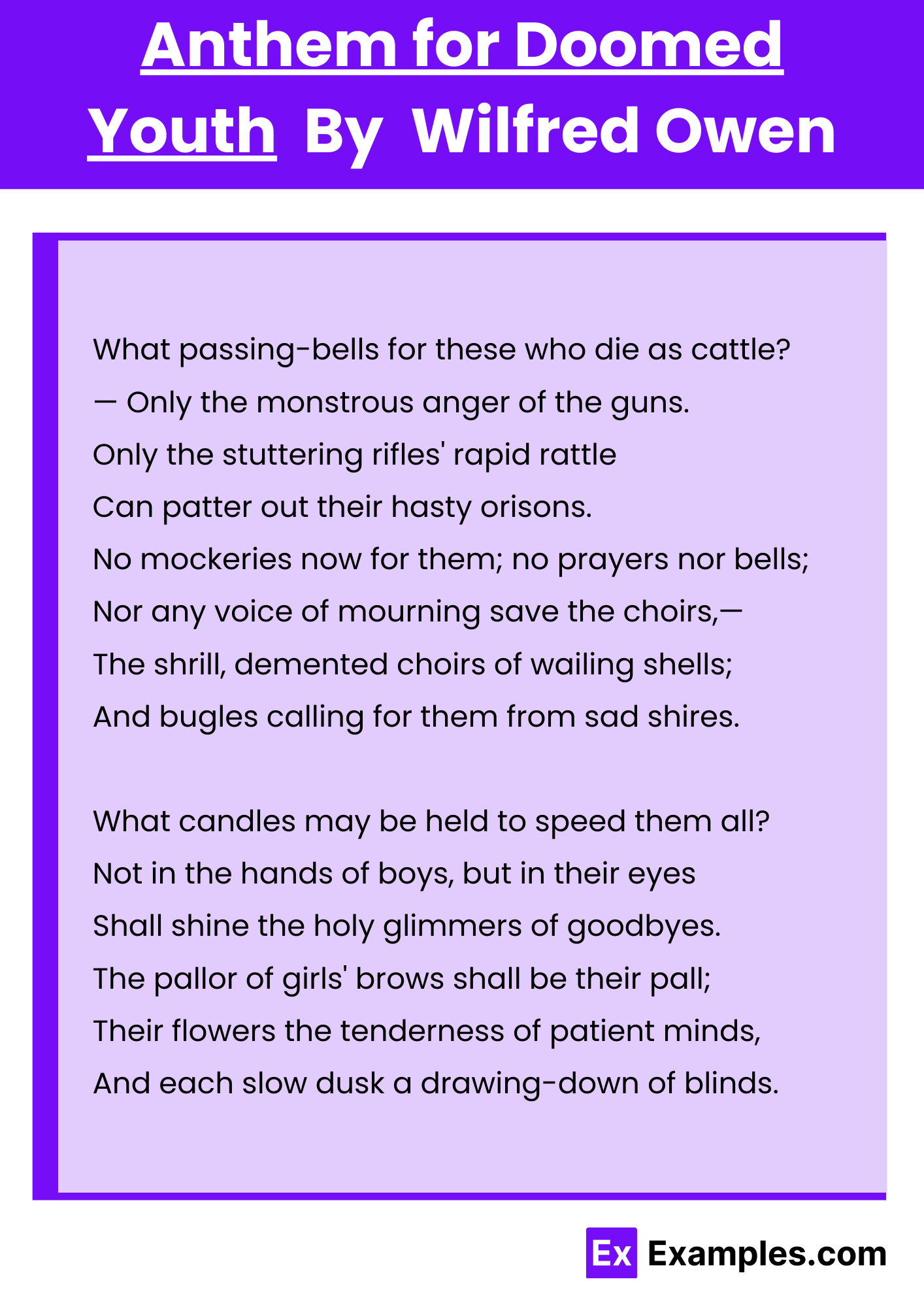

"Anthem for Doomed Youth" was written by British poet Wilfred Owen in 1917, while Owen was in the hospital recovering from injuries and trauma resulting from his military service during World War I. The poem laments the loss of young life in war and describes the sensory horrors of combat. It takes particular issue with the official pomp and ceremony that surrounds war (gestured to by the word "Anthem" in the title), arguing that church bells, prayers, and choirs are inadequate tributes to the realities of war. It is perhaps Owen's second most famous poem, after " Dulce et Decorum Est ."

- Read the full text of “Anthem for Doomed Youth”

| LitCharts |

The Full Text of “Anthem for Doomed Youth”

1 What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

2 — Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

3 Only the stuttering rifles' rapid rattle

4 Can patter out their hasty orisons.

5 No mockeries now for them; no prayers nor bells;

6 Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs,—

7 The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells;

8 And bugles calling for them from sad shires.

9 What candles may be held to speed them all?

10 Not in the hands of boys, but in their eyes

11 Shall shine the holy glimmers of goodbyes.

12 The pallor of girls' brows shall be their pall;

13 Their flowers the tenderness of patient minds,

14 And each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds.

“Anthem for Doomed Youth” Summary

“anthem for doomed youth” themes.

Nationalism, War, and Waste

- See where this theme is active in the poem.

Ritual and Remembrance

Line-by-line explanation & analysis of “anthem for doomed youth”.

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

— Only the monstrous anger of the guns. Only the stuttering rifles' rapid rattle Can patter out their hasty orisons.

No mockeries now for them; no prayers nor bells; Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs,— The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells;

And bugles calling for them from sad shires.

What candles may be held to speed them all? Not in the hands of boys, but in their eyes Shall shine the holy glimmers of goodbyes. The pallor of girls' brows shall be their pall;

Lines 13-14

Their flowers the tenderness of patient minds, And each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds.

“Anthem for Doomed Youth” Poetic Devices & Figurative Language

Alliteration.

- See where this poetic device appears in the poem.

End-Stopped Line

Personification, rhetorical question, “anthem for doomed youth” vocabulary.

Select any word below to get its definition in the context of the poem. The words are listed in the order in which they appear in the poem.

- Passing-bells

- See where this vocabulary word appears in the poem.

Form, Meter, & Rhyme Scheme of “Anthem for Doomed Youth”

Rhyme scheme, “anthem for doomed youth” speaker, “anthem for doomed youth” setting, literary and historical context of “anthem for doomed youth”, more “anthem for doomed youth” resources, external resources.

Poems in Response to Owen — A BBC show in which three contemporary poets respond to Wilfred Owen's poetry.

Learn More About War Poetry — A series of podcast documentaries from the University of Oxford about various aspects of World War I poetry, including some excellent material specifically about Wilfred Owen.

More Poems and Biography — A valuable resource of Owen's other poetry, and a look at his life.

A Reading by Stephen Fry — Internationally famous actor, comedian,and writer Stephen Fry reads the poem (with a bugle call in the background).

Bringing WWI to Life — In this clip, director Peter Jackson discusses his recent WWIfilm, They Shall Not Grow Old. Though technology, Jackson brings old war footage to vivid life, restoring a sense of the soldiers as actual people.

LitCharts on Other Poems by Wilfred Owen

Dulce et Decorum Est

Mental Cases

Spring Offensive

Strange Meeting

The Next War

Ask LitCharts AI: The answer to your questions

Anthem for Doomed Youth

By Wilfred Owen

‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ by Wilfred Owen presents an alternate view of the lost lives during World War I against nationalist propaganda.

Wilfred Owen

Nationality: English

He has been immortalized in several books and movies.

Key Poem Information

Unlock more with Poetry +

Central Message: Glorification of soldier deaths is senseless eulogization of the atrocious war

Themes: War

Speaker: Likely Wilfred Owen himself

Emotions Evoked: Anger , Grief , Guilt , Sadness

Poetic Form: Sonnet

Time Period: 20th Century

'Anthem for Doomed Youth' by Wilfred Owen is a stirring anti-war poem that not only highlights the dehumanizing atrocities of the war but questions its senseless glorification by blind nationalists.

Poem Analyzed by Elise Dalli

B.A. Honors Degree in English and Communications

It marked a turning point in his career. Working with Siegfried Sassoon (read Sassoon’s poetry here ), Wilfred Owen produced the majority of his writing while convalescing at Craiglockhart, and the poems that he wrote there remain among the most poignant of his pieces. ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ was written from September to October 1917.

Wilfred Owen wrote this poem in 1917 while recovering from shell shock or psychological trauma in Craiglockhart War Hospital after serving in the First World War as a British Soldier. After a firsthand experience of the war, Owen could see through the blind nationalism and expressed his concern over the promotion and glorification of the war. In the Craiglockhart War Hospital, he met fellow poet Siegfried Sasson, known for his unflinching realistic portrayal of the war. Sasson influenced Owen's romantic writing style , molding it into the strong criticism found in this poem. Sasson also had a hand in naming this poem.

Explore Anthem for Doomed Youth

- 2 Structure and Form

- 3 Analysis, Stanza by Stanza

- 4 Historical Background

Written in sonnet form, ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ serves as a dual rejection: both of the brutality of war, and of religion. The first part of the poem takes place during a pitched battle, whereas the second part of the poem is far more abstract and happens outside the war, calling back to the idea of the people waiting at home to hear about their loved ones. It was Siegfried Sassoon who gave the poem the title ‘Anthem’. This poem also draws quite heavily on Wilfred Owen’s love of poetry.

The Poem Analysis Take

Expert Insights by Jyoti Chopra

B.A. (Honors) and M.A. in English Literature

In ' Anthem for Doomed Youth ' Wilfred Owen transcends the nationalistic propaganda of his times and presents the adverse impact of the war on humanity and civilization. The poem questions the glorification of the war and martyrdom; however, it doesn't devalue the soldier's sacrifices. The poem suggests personal forms of remembrance for the lost soldiers instead of appropriating their deaths for the promotion of war and nationalistic propaganda. Furthermore, it humanizes and descends the soldiers from the hero -worship to accentuate the dehumanization of the war. Remarkably, it poignantly presents the profound physical and psychological pain the soldiers and their loved ones suffer, highlighting the immense cost of the war.

Structure and Form

‘ Anthem for Doomed Youth ‘ is a sonnet, characterized by its fourteen-line structure divided into an octave (the first eight lines) and a sestet (the final six lines). This format blends elements of both Petrarchan and Shakespearean sonnets , reflecting both the poem’s European war context and its British origins.

The poem is written in iambic pentameter , which means each line typically has five iambs (an unstressed- stressed syllable pattern). This meter gives the poem a measured, somber tone suitable for its theme of mourning and loss. There are variations, such as the hypercatalexis in the first line, which adds an extra syllable at the end of the line and conveys a sense of disruption and irregularity, mirroring the chaos of war.

Analysis, Stanza by Stanza

First stanza.

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle? Only the monstrous anger of the guns. Only the stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle Can patter out their hasty orisons. No mockeries now for them; no prayers nor bells; Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs, The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells; And bugles calling for them from sad shires.

‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ opens, as do many of Owen’s poems , with a note of righteous anger: what passing-bells for those who die as cattle? The use of the word ‘cattle’ in the opening line sets the tone and the mood for the rest of it – it dehumanizes the soldiers much in the same way that Owen sees the war dehumanizing the soldiers, bringing up imagery of violence and unnecessary slaughter. Owen made no secret that he was a great critic of the war; his criticism of pro-war poets has been immortalized in poems such as Dulce et Decorum Est , and in letters where Wilfred Owen wrote home. In ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth ,’ Owen makes no secret of the fact that he believes the war is a horrific waste of human life.

The first stanza of ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ continues in the pattern of a pitched battle, as though it were being written during the Pushover the trenches. Owen notes the ‘monstrous anger’ of the guns, the ‘stuttering rifles’, and the ‘shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells’. It’s a horrible world that Owen creates in those few lines, bringing forward the idea of complete chaos and madness, of an almost animalistic loss of control – but in the same paragraph, he also points out the near-reluctance of the soldiers fighting. At this point, a great deal of the British Army had lost faith in the war as a noble cause and was only fighting out of fear of court-martial, therefore the rifles stutter their ‘hasty orisons’. Orisons are a type of prayer, which further points out Owen’s lack of faith – he believes that war has overshadowed faith, that it has taken the place of belief. As he says in another poem, ‘we only know war lasts, rain soaks, and clouds sag stormy’.

Ironically, the use of onomatopoeia for the guns and the shells humanizes war far more than its counterparts. War seems a living being when reading this poem; much more so than the soldiers, or the mourners in the second stanza, and the words used – ‘monstrous anger’, ‘stuttering’, ‘shrill demented choirs’ – bring forward the image of war as not only human, but alive, a great monster chewing up everything in its path, including the soldiers that poured out their blood into shell holes. The quiet nature of the second stanza, and the use of softened imagery, brings out, in sharp relief, the differences between war and normal life, which has ceased to be normal at all.

Second Stanza

What candles may be held to speed them all? Not in the hands of boys, but in their eyes Shall shine the holy glimmers of good-byes. The pallor of girls’ brows shall be their pall; Their flowers the tenderness of patient minds, And each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds.

In the second stanza, Owen moves away from the war to speak about the people who have been affected by it: the civilians who mourn their lost brothers, fathers, grandfathers, and uncles, the ones who wait for them to come home and wind up disappointed and miserable when they don’t. The acute loss of life that Owen witnessed in the war is made all the more poignant and heartbreaking in the second stanza, which, compared to the first, seems almost unnaturally still. He speaks about the futility of mourning the dead who have been lost so carelessly, and by making the mourners youthful, he draws further attention to the youthfulness of the soldiers themselves. Note the clever use of words like pallor most often associated with death or dying.

Owen also frames this second stanza in the dusk. This is to signify the end, which of course for many of the soldiers it was their end. The second stanza is also considerably shorter than the first. It contains only six lines compared to the first which contains nine. The meter is far more even in the second stanza as well. This is only subtly different but the net effect is while the first stanza creates a frenetic, disjointed feel the second is more reflective of a solemnity.

The final line – ‘ And each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds ‘ – highlights the inevitability and the quiet of the second stanza, the almost pattern-like manner of mourning that has now become a way of life. It normalizes the funeral and hints at the idea that this is not the first, second, nor last time that such mourning will be carried out.

Throughout ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ there are heavy allusions to a great variety of writers.

- Lines 6 to 7 reference the poem ‘ To Autumn ‘, by John Keats (read more of Keats’ poems )

- Lines 10-11 reference ‘ The Wanderings of Oisin ‘, a poem by William Butler Yeats (read more Yeats’ poetry )

- Lines 10-13 also references ‘ A New Heaven ‘, a poem by Wilfred Owen himself.

Historical Background

Wilfred Edward Salter Owen was born at Plas Wilmont on the 18 th of March, 1893. He remains one of the leading poets of the First World War, despite most of his works being published posthumously. He was a second lieutenant in the Manchester regiment, though shortly after, he fell into a shell hole and was blown sky-high by a trench mortar, spending several days next to the remains of a fellow officer. Soon afterward, he was diagnosed as suffering from neurasthenia and was sent to Craiglockhart, where he met Siegfried Sassoon. This was the point where Owen began to work on his poetry .

Poetry + Review Corner

20th century, world war one (wwi).

Home » Wilfred Owen » Anthem for Doomed Youth

About Elise Dalli

Join the poetry chatter and comment.

Exclusive to Poetry + Members

Join Conversations

Share your thoughts and be part of engaging discussions.

Expert Replies

Get personalized insights from our Qualified Poetry Experts.

Connect with Poetry Lovers

Build connections with like-minded individuals.

The only way I could’ve passed my exams were using this website, Thank you!! Btw my friend recommended it to me!!

That’s excellent. I’m glad you have found the site useful. How did you get on in your exams? Is there anything we can do to make the site even better?

I tried finding an analysis in various websites when my brother told me about this. This website is truly wonderful and thank you for your help Elise.

Your brother is a man of taste! Glad you found us useful – tell your friends!

good analysis.

Thanks, Bob.

I thoroughly enjoyed this analysis, it gives great insight into Wilfred Owen and his works as well as common poetry of the time.

Great work !

Access the Complete PDF Guide of this Poem

Poetry+ PDF Guides are designed to be the ultimate PDF Guides for poetry. The PDF Guide consists of a front cover, table of contents, with the full analysis, including the Poetry+ Review Corner and numerically referenced literary terms, plus much more.

Get the PDF Guide

Experts in Poetry

Our work is created by a team of talented poetry experts, to provide an in-depth look into poetry, like no other.

Cite This Page

Dalli, Elise. "Anthem for Doomed Youth by Wilfred Owen". Poem Analysis , https://poemanalysis.com/wilfred-owen/anthem-for-doomed-youth/ . Accessed 8 June 2024.

Help Center

Request an Analysis

(not a member? Join now)

Poem PDF Guides

PDF Learning Library

Poetry + Newsletter

Poetry Archives

Poetry Explained

Poet Biographies

Useful Links

Poem Explorer

Poem Generator

Poem Solutions Limited, International House, 36-38 Cornhill, London, EC3V 3NG, United Kingdom

Discover and learn about the greatest poetry, straight to your inbox

Unlock the Secrets to Poetry

Download Poetry PDFs Guides

Complete Poetry PDF Guide

Perfect Offline Resource

Covers Everything Need to Know

One-pager 'snapshot' PDF

Offline Resource

Gateway to deeper understanding

Get this Poem Analysis as an Offline Resource

Poetry+ PDF Guides are designed to be the ultimate PDF Guides for poetry. The PDF Guide contains everything to understand poetry.

A Summary and Analysis of Wilfred Owen’s ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ is probably, after ‘ Dulce et Decorum Est ’, Wilfred Owen’s best-known poem. But like many well-known poems, it’s possible that we know it so well that we hardly really know it at all. In the following post, we offer a short analysis of Owen’s canonical war poem, and take a closer look at the language he employs.

‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’: introduction

Start with the title of Owen’s poem: ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’. The Oxford English Dictionary offers several different meanings for the word ‘anthem’, none of which is especially positive. ‘A rousing or uplifting popular song’: Owen’s poem may be popular, but it’s hardly uplifting.

‘A song officially adopted by a nation, school, or other body … typically used as an expression of identity and pride’: Owen’s poetry has definitely been adopted by schools around the country (and beyond his home country of the UK), but ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ is not exactly about pride – at least, Owen sees little to be proud of in the slaughter of thousands of young men in the name of war.

‘A poem … esp. one of praise or gladness’: we may praise the young men who are giving their lives for a senseless war, but there’s little to be glad about here.

Is ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’, then, an ironic title? Not exactly, but then it does have a wry edge, as a brief summary of the poem’s contents will reveal.

‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ is a sonnet divided into an octave (eight-line unit) and a sestet (a six-line unit). Although such a structure is usually associated with a Petrarchan or Italian sonnet , here the rhyme scheme suggests the English or Shakespearean sonnet: ababcdcdeffegg . The one twist is in the third quatrain, which is rhymed effe , with enclosed rhymes, rather than the more usual efef .

‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’: summary and analysis

As with Owen’s powerful use of pararhyme in his other poems (perhaps most powerfully of all in the couplets of his poem ‘Strange Meeting’ ), such a twist on the established rhyme scheme is designed to wrong-foot us, and remind us that nothing in this war is as it seems: the old certainties have broken down.

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle? — Only the monstrous anger of the guns. Only the stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle Can patter out their hasty orisons.

The octave lists a number of noises associated with battle and warfare, contrasting them with the respectful funeral sounds: the ‘passing bells’ mournfully announcing someone’s death are mutated into the sounds of gunfire; the ‘rapid rattle’ of the ‘stuttering rifles’ constitutes the only prayers (i.e. ‘orisons’) these poor doomed soldiers will hear.

Picking up on the prayer theme which also lurks in the ‘anthem’ of the poem’s title, there may be a faint pun in ‘patter’ on ‘paternoster’, the first words of the Lord’s Prayer in Latin : pater noster means ‘Our Father’. But this is a side-issue and need not detain us in our analysis of the poem. ‘Stuttering rifles’ is a nice example of onomatopoeia – or rather, a horrific example of it – with the repeated ‘r’ and ‘t’ sounds evoking the sound of the rifle-fire.

Note how the human voice has here been supplanted by the machinery of mechanised warfare: the rifles are described as ‘stuttering’, thus gesturing towards a monstrous form of anthropomorphism; ‘prayers’ and ‘orisons’, usually uttered by the human voice to God, are replaced by the sounds of the guns; the ‘choirs’ traditionally associated with church-music are not people singing, but the ‘shrill, demented’ sounds of the ‘wailing shells’ as they fly through the air and explode.

No mockeries now for them; no prayers nor bells; Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs,— The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells; And bugles calling for them from sad shires.

Where more traditional human activity does remain, such as in the playing of bugles, this, too, has been perverted so that it is inextricably bound up with military action.

What candles may be held to speed them all? Not in the hands of boys, but in their eyes Shall shine the holy glimmers of goodbyes.

How interesting, then, that the mechanical twisting of religious acts of devotion and respect which we are presented with in the octave should, in the sestet, be turned on its head.

Owen tells us that the most sincere ‘holy glimmer’ of respect for the dead soldiers is not found in the glimmer of candles (lighted as an act of remembrance) but in the brightly shining eyes of young boys (suggestive not only of the children made fatherless orphans by the war but also of their slightly older brothers, young boys of sixteen or seventeen who had gone off to fight in the war).

The pallor of girls’ brows shall be their pall; Their flowers the tenderness of patient minds, And each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds.

The ultimate funeral pall is no sheet placed over the tombs of dead soldiers but the pale brows of the young girls the men left behind (first for war and then, tragically and more permanently, in death), girls who have lost their sweethearts and are pale with grief.

The ‘tenderness of patient minds’ – ‘patient’ not only because those left at home had to wait patiently and agonisingly for news of their loved ones fighting at the front, but also in the sense of ‘suffering’ (the original meaning of ‘patient’) – will be more powerful a memorial for the dead men than the literal flowers placed on their graves.

Even the world itself, and the natural order, seems to mourn: every time the light fades from the land and dusk falls, it will be as though the world has gone into mourning every night for the dead men (the act of drawing down the blinds of a home was a common way of showing yours was a house in mourning).

In the last analysis, ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ is a clever sonnet but more than this, it’s an impassioned one: Wilfred Owen fills his poem with raw emotion which moves us in every line. The cleverness isn’t allowed to dominate, yet Owen’s use of mourning imagery and funeral conventions makes for a poem that not only makes us think, but moves us too.

If you found this commentary on ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ useful, you can discover more classic war poetry here .

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Type your email…

5 thoughts on “A Summary and Analysis of Wilfred Owen’s ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’”

Reblogged this on Greek Canadian Literature .

You set me thinking is it possible to know something so well we don’t know it at all ? Does familiarity breed contempt ? Do we become tired of explanation? Like a proof – reader do we just see lines of words? Can the old become new and fresh again or are we always seeking something new? Lastly just what are we searching for , perfection or oblivion?

For me, the most heartbreaking of all Wilfred Owen’s poems is The Parable of the Old Man and the Young. It turns what we expect of humanity on its head as I suppose war often does.

- Pingback: A Short Analysis of Wilfred Owen’s ‘The Last Laugh’ – Interesting Literature

- Pingback: A Short Analysis of Wilfred Owen’s ‘The Next War’ – Interesting Literature

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

- Poem Guides

- Poem of the Day

- Collections

- Harriet Books

- Featured Blogger

- Articles Home

- All Articles

- Podcasts Home

- All Podcasts

- Glossary of Poetic Terms

- Poetry Out Loud

- Upcoming Events

- All Past Events

- Exhibitions

- Poetry Magazine Home

- Current Issue

- Poetry Magazine Archive

- Subscriptions

- About the Magazine

- How to Submit

- Advertise with Us

- About Us Home

- Foundation News

- Awards & Grants

- Media Partnerships

- Press Releases

- Newsletters

Anthem for Doomed Youth

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Print this page

- Email this page

Poems and prose about conflict, armed conflict, and poetry's role in shaping perceptions and outcomes of war.

Dulce et Decorum Est

Arms and the boy, strange meeting, the last laugh, insensibility.

- Audio Poems

- Audio Poem of the Day

- Twitter Find us on Twitter

- Facebook Find us on Facebook

- Instagram Find us on Instagram

- Facebook Find us on Facebook Poetry Foundation Children

- Twitter Find us on Twitter Poetry Magazine

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Poetry Mobile App

- 61 West Superior Street, Chicago, IL 60654

- © 2024 Poetry Foundation

Wilfred Owen, who wrote some of the best British poetry on World War I, composed nearly all of his poems in slightly over a year, from August 1917 to September 1918. In November 1918 he was killed in action at the age of 25, one...

- Sorrow & Grieving

- Social Commentaries

- War & Conflict

Wilfred Owen: Poems

By wilfred owen, wilfred owen: poems summary and analysis of "anthem for doomed youth".

The speaker says there are no bells for those who die "like cattle" – all they get is the "monstrous anger of the guns". They have only the ragged sounds of the rifle as their prayers. They get no mockeries, no bells, no mourning voices except for the choir of the crazed "wailing shells" and the sad bugles calling from their home counties.

There are no candles held by the young men to help their passing, only the shimmering in their eyes to say goodbye. The pale faces of the girls will be what cover their coffins, patient minds will act as flowers, and the "slow dusk" will be the drawing of the shades.

This searing poem is one of Owen's most critically acclaimed. It was written in the fall of 1917 and published posthumously in 1920. It may be a response to the anonymous preface from Poems of Today (1916), which proclaims that boys and girls should know about the poetry of their time, which has many different themes that "mingle and interpenetrate throughout, to the music of Pan's flute, and of Love's viol, and the bugle-call of Endeavor, and the passing-bells of death."

The poem owes its more mature imagery and message to Owen's introduction to another WWI poet, Siegfried Sassoon, while he was convalescing in Edinburgh's Craiglockhart Hospital in August 1917. Sassoon was older and more cynical, and the meeting was a significant turning point for Owen. The poem is structured as a Petrarchan sonnet with a Shakespearean rhyme scheme and is an elegy or lament for the dead. Owen's meter is mostly iambic pentameter with some small derivations that keep the reader on his or her toes as they read. The meter reinforces the juxtapositions in the poem and the sense of instability caused by war and death.

Owen begins with a bitter tone as he asks rhetorically what "passing-bells" of mourning will sound for those soldiers who die like cattle in an undignified mass. They are not granted the rituals and rites of good Christian civilians back home. They do not get real prayers, only rifle fire. Their only "choirs" are of shells and bugles. This first set of imagery is violent, featuring weapons and harsh noises of war. It is set in contrast to images of the church; Owen is suggesting organized religion cannot offer much consolation to those dying on the front. Kenneth Simcox writes, "These religious images...symbolize the sanctity of life – and death – while suggesting also the inadequacy, the futility, even meaninglessness, of organized religion measured against such a cataclysm as war. To 'patter out' is to intone mindlessly, an irrelevance. 'Hasty' orisons are an irreverence. Prayers, bells, mockeries only."

In the second stanza the poem slows down and becomes more dolorous, less enraged. The poet muses that the young men will not have candles – the only light they will get will be the reflections in their fellow soldiers' eyes. They must have substitutions for their coffin covers ("palls"), their flowers, and their "slow dusk". The poem has a note of finality, of lingering sadness and an inability to avoid the reality of death and grief.

The critic Jon Silkin notes that, while the poem seems relatively straightforward, there is some ambiguity: "Owen seems to be caught in the very act of consolatory mourning he condemns...a consolation that permits the war's continuation by civilian assent, and is found ambiguously in the last line of the octet." Owen might be trying to make the case that his poetry is a more realistic form of the expression of grief and the rituals of mourning.

Wilfred Owen: Poems Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for Wilfred Owen: Poems is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

How could we interpret the symbol of ‘fruits’?

Poem title, please?

What are the similarities between the poems Next War and Dulce et Decorum est? for example how grief is portrayed through both is almost the same fashion

I'm not sure what you mean by "next war".

Experience of war in Dulce Et Decorum Est

"Dulce et Decorum est" is without a doubt one of, if not the most, memorable and anthologized poems in Owen's oeuvre. Its vibrant imagery and searing tone make it an unforgettable excoriation of WWI, and it has found its way into both literature...

Study Guide for Wilfred Owen: Poems

Wilfred Owen: Poems study guide contains a biography of Wilfred Owen, literature essays, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis of Wilfred Owen's major poems.

- About Wilfred Owen: Poems

- Wilfred Owen: Poems Summary

- Character List

Essays for Wilfred Owen: Poems

Wilfred Owen: Poems essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of Wilfred Owen's poetry.

- “Fellowships Untold”: The Role of Wilfred Owen’s Poetry in Understanding Comradeship During World War I

- Analysis of Owen's "Strange Meeting"

- The Development of Modernism as Seen through World War I Poetry and "The Prussian Officer"

- Commentary on the Poem “Disabled” by Wilfred Owen

- Commentary on the Poem "Anthem for Doomed Youth" by Wilfred Owen

E-Text of Wilfred Owen: Poems

Wilfred Owen: Poems e-text contains the full texts of select poems by Wilfred Owen.

- Introduction by Siegfried Sassoon

- Strange Meeting

- Greater Love

- Apologia pro Poemeta Mio

Wikipedia Entries for Wilfred Owen: Poems

- Introduction

- War service

Analysis Pages

- Alliteration

- Literary Devices

Tone in Anthem for Doomed Youth

A Mix of Satire and Sincerity: Throughout the poem, Owen satirically contrasts the imagery of battle with solemn funerary rites to illustrate the incompatibility of religion and combat. In the first stanza for example, the tone is satirical; the soldiers fight and die without receiving the proper religious commemoration for their sacrifice, their deaths marked by gunfire instead of bells, and the burial rites of the Church are described as “mockeries.” In the second stanza, the tone shifts from satire to sincerity. The “sad shires” lack the means to bury their honored dead, without the traditional items for funerary rights. However, this lack reveals genuine grief, which is powerful and original.

Tone Examples in Anthem for Doomed Youth:

Text of owen's poem.

"in their eyes Shall shine the holy glimmers of goodbyes. ..." See in text (Text of Owen's Poem)

The speaker takes the dark, deathly funerary images from the first stanza and recasts them to describe the other side of war: the grieving process. Instead of bullets and death, the speaker envisions the mourning boys whose tears glimmer in their eyes. By describing the other side of war, the speaker creates an introspective, meditative tone. He establishes that the mourner’s grief is spiritual and perpetual, unlike the earthly, finite scenes of the first stanza.

Subscribe to unlock »

"sad shires..." See in text (Text of Owen's Poem)

The final line of the first stanza announces the transition from the foreign war zone to the home country. The bugles call for the soldiers from “shires,” regions or counties in England under the rule of a governor or bishop. In the second stanza, the poem takes on a sombre tone and shifts to the grieving, or “sad,” homes of the fallen soldiers.

"passing-bells..." See in text (Text of Owen's Poem)

The word “passing-bell” refers to a church bell rung following a death to signal a moment of mourning and prayer. This word choice serves as auditory imagery, evoking the sound of bells rung for funerary service. Thus, the speaker immediately establishes a somber tone to the poem, one which contrasts sharply against the backdrop of war.

- National Poetry Month

- Materials for Teachers

- Literary Seminars

- American Poets Magazine

Main navigation

- Academy of American Poets

User account menu

Find and share the perfect poems.

Page submenu block

- literary seminars

- materials for teachers

- poetry near you

Anthem for Doomed Youth

Add to anthology.

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle? Only the monstrous anger of the guns. Only the stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle Can patter out their hasty orisons. No mockeries now for them; no prayers nor bells; Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs, The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells; And bugles calling for them from sad shires. What candles may be held to speed them all? Not in the hands of boys, but in their eyes Shall shine the holy glimmers of good-byes. The pallor of girls’ brows shall be their pall; Their flowers the tenderness of patient minds, And each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds.

This poem is in the public domain.

More by this poet

Dulce et decorum est.

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks, Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge, Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs And towards our distant rest began to trudge. Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind; Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Winter Song

The browns, the olives, and the yellows died, And were swept up to heaven; where they glowed Each dawn and set of sun till Christmastide, And when the land lay pale for them, pale-snowed, Fell back, and down the snow-drifts flamed and flowed.

The Unreturning

Newsletter sign up.

- Academy of American Poets Newsletter

- Academy of American Poets Educator Newsletter

- Teach This Poem

Anthem For Doomed Youth by Wilfred Owen: poem analysis

- wilfred-owen

This is an analysis of the poem Anthem For Doomed Youth that begins with:

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle? Only the monstrous anger of the guns. ... full text

More information about poems by Wilfred Owen

- Analysis of Dulce Et Decorum Est

- Analysis of Roundel

- Analysis of A Palinode

To view this video please enable JavaScript, and consider upgrading to a web browser that supports HTML5 video

- A place to publish and distribute your work on a high-authority poetry website.

- Balanced and credible private feedback from educators and authors.

- A respectful community of all levels of poetry enthusiasts.

- Additional premium tools and resources.

“Anthem for Doomed Youth” by Wilfred Owen Literature Analysis Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

War is one of the most horrific events that could possibly happen to our world. It is feared and avoided by generations of people. Even though the modern generations of humans growing up in the Western countries and on the territory of Global North have never faced real war, they are well aware of its terrors and scary consequences. The First and Second World Wars have taught people a memorable lesson. The events of the past still haunt some of the countries, the relics of the war are still being found in the places of former battlefields, the veterans are being honored and the films about the war times are still popular.

Of course, the modern humanity knows about the Wars not only from the history books and classes. The First and Second World Wars were massive events that caused horrible destructions and had millions of victims. Lots of people were enlisted in the army and fought at the front lines. Many of these people were poets and writers. Their works outlived the creators in order to serve as reminders of the awful and shocking circumstances these men and women had to witness.

Wilfred Owen was one of such poets. He was born in 1893 in England. He was a highly intelligent man and worked as a language tutor in France, until his patriotic duty sent him to the front line (Wilfred Owen, par. 3). All of the poems of Wilfred Owen are collected in a single volume. There are not many of his works, because this brave man died young.

He is a typical example of his generation, a young man with proper values that fought for his motherland and died at the battlefield as a hero, crossing the Sambre canal and leading his men (Wilfred Owen, par. 4). Owen’s style and works were strongly influenced by another great poet of the First World War times, Siegfried Sassoon (Biography of Wilfred Owen 2014, par. 2). Wilfred Owen was deeply touched by the scenes he observed during the war.

This is why many of his poems are tribute to the war times and reflect the pain and horror the young man had to experience every day. The descriptions of war in literature and poetry are much more striking than the dry facts from the history books. The art of using right words and comparisons in order to create the brightest associations in the minds of the readers requires a lot of talent and skills. Wilfred Owen possessed both, and this is why he is considered one of the greatest First World War poets in the world.

The poem called “Anthem for Doomed Youth” was written in 1917 in fall. The poet begins asking his readers a question about the young soldiers that are killed like cattle at the battle fields all over the world. Owen wonders what kind of “passing bells” (1) will say farewell to these boys and girls that barely saw the life. The poet describes the sounds of shooting guns and rifles and compares them to the prayers because these are the last and only sounds the young fighters hear before dying.

The author mentions that there are crowds of soldiers with such sad destinies that die together from both sides and remain forgotten and lost among the hundreds of other victims of the battles. The author answers his initial question saying that there are no “voices of mourning” (6) prepared for the unknown heroes. In the next lines of the poem Wilfred Owen says that the candle light that is always a part of the holy ritual will only shine in the eyes of the doomed young boys.

The poet mentions that these boys will remain lost in the battlefields, yet the memories about them will always live in the hearts of their loved ones and close people, and this is the only farewell ritual they will ever have. “The tenderness of patient minds” (13) will become the flowers on their graves. The last image the poet shares with his readers is the blinds being drawn down at dusk; this comparison is designed to remind of the civilian people at their homes during the war times grieving about the relatives and friends they lost. This last image also serves as a finalizing phrase that makes the poem complete and finished.

Wilfred Owen compares the routine of the front lines that surrounds the soldiers at the moments of their death with the only holy ritual they will have because under the circumstances of the war most of the soldiers that died at the battlefields were just forgotten, some of them never were properly buried.

The poem is called “Anthem for Doomed Youth” because Wilfred Owen got to personally observe the horrific conditions that were killing thousands of young soldiers every day. Most of these soldiers were under the age of twenty; they arrived to the front lines and were doomed. The ones that survived were called “the lost generation” because after they saw the realities of the war it was impossible for them to adjust to the normal life.

Works Cited

Biography of Wilfred Owen . Poem Hunter . 2014. Web.

Owen, Wilfred. Anthem for Doomed Youth . 2014. Web.

Owen, Wilfred . BBC . 2014. Web.

Owen, Wilfred. War Poetry . n. d. Web.

- War Poetry: Poets' Attitudes Towards War

- When is War Justifiable? Axiomatic Justification of War

- The Books "The Man I Killed" by O'Brien and "Anthem for Doomed Youth" by Owen

- Shakespeare Literature: Prophecy and Macbeth Morality

- Literary Analysis of "Hamlet" by William Shakespeare

- "Dover Beach" by Matthew Arnold Literature Critique

- A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Play by William Shakespeare

- Shakespeare’s Sonnet “Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer’s Day”

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, April 30). “Anthem for Doomed Youth” by Wilfred Owen Literature Analysis. https://ivypanda.com/essays/anthem-for-doomed-youth-by-wilfred-owen-literature-analysis/

"“Anthem for Doomed Youth” by Wilfred Owen Literature Analysis." IvyPanda , 30 Apr. 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/anthem-for-doomed-youth-by-wilfred-owen-literature-analysis/.

IvyPanda . (2020) '“Anthem for Doomed Youth” by Wilfred Owen Literature Analysis'. 30 April.

IvyPanda . 2020. "“Anthem for Doomed Youth” by Wilfred Owen Literature Analysis." April 30, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/anthem-for-doomed-youth-by-wilfred-owen-literature-analysis/.

1. IvyPanda . "“Anthem for Doomed Youth” by Wilfred Owen Literature Analysis." April 30, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/anthem-for-doomed-youth-by-wilfred-owen-literature-analysis/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "“Anthem for Doomed Youth” by Wilfred Owen Literature Analysis." April 30, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/anthem-for-doomed-youth-by-wilfred-owen-literature-analysis/.

Anthem for Doomed Youth

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle? — Only the monstrous anger of the guns. Only the stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle Can patter out their hasty orisons. No mockeries now for them; no prayers nor bells; Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs,— The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells; And bugles calling for them from sad shires. What candles may be held to speed them all? Not in the hands of boys, but in their eyes Shall shine the holy glimmers of goodbyes. The pallor of girls’ brows shall be their pall; Their flowers the tenderness of patient minds, And each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds.

Summary of Anthem for Doomed Youth:

Analysis of literary devices used in “anthem for doomed youth”.

“Not in the hands of boys, but in their eyes Shall shine the holy glimmers of goodbyes.”

Analysis of Poetic Devices Used in “Anthem for Doomed Youth”

Quotes to be used.

“What candles may be held to speed them all? Not in the hands of boys, but in their eyes Shall shine the holy glimmers of goodbyes. The pallor of girls’ brows shall be their pall; Their flowers the tenderness of patient minds, And each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds.”

Related posts:

Post navigation.

Home — Essay Samples — Literature — Wilfred Owen — Literary Analysis of “Anthem for Doomed Youth” by Wilfred Owen

Literary Analysis of "Anthem for Doomed Youth" by Wilfred Owen

- Categories: Wilfred Owen

About this sample

Words: 1852 |

10 min read

Published: Jun 29, 2018

Words: 1852 | Pages: 4 | 10 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr Jacklynne

Verified writer

- Expert in: Literature

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 887 words

4.5 pages / 1980 words

4 pages / 1725 words

7 pages / 3092 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Wilfred Owen’s “Strange Meeting” explores an extraordinary meeting between two enemy combatants in the midst of battle. Owen forgoes the familiar poetics of glory and honor associated with war and, instead, constructs a balance [...]

Death has been a prominent theme across literature, with its countless interpretations showcasing the diverse ways it has influenced different authors. Thomas Hardy's novel The Mayor of Casterbridge is described by Hardy as [...]

“Dulce et Decorum Est” is a poem written by Wilfred Owen that describes the horrors of World War I through the senses of a soldier. Owen uses extreme, harsh imagery to accurately describe how the war became all the soldiers were [...]

Owen effectively conveys the emotions of a hopeless soldier, through the development and progression of thought in ‘Wild With All Regrets’. He uses various parallel trains of thought simultaneously, such as the past, present and [...]

The manifestation of war within a society is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon that elicits a wide array of emotions and reactions among individuals. War, as a socio-political event, exerts profound influences on the lives [...]

"When Thomas More wrote Utopia in 1515, he started a literary genre with lasting appeal for writers who wanted not only to satirize existing evils but to postulate the state, a kind of Golden Age in the face of reality" (Hewitt [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Anthem for Doomed Youth

Ai generator.

Download Anthem for Doomed Youth Full Poem - PDF

Anthem for Doomed Youth Poem – by Wilfred Owen (Text-Version)

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle? — Only the monstrous anger of the guns. Only the stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle Can patter out their hasty orisons. No mockeries now for them; no prayers nor bells; Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs,— The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells; And bugles calling for them from sad shires.

What candles may be held to speed them all? Not in the hands of boys, but in their eyes Shall shine the holy glimmers of goodbyes. The pallor of girls’ brows shall be their pall; Their flowers the tenderness of patient minds, And each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds.

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

10 Examples of Public speaking

20 Examples of Gas lighting

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Are We Doomed? Here’s How to Think About It

By Rivka Galchen

In January, the computer scientist Geoffrey Hinton gave a lecture to Are We Doomed?, a course at the University of Chicago. He spoke via Zoom about whether artificial intelligence poses an existential threat. He was cheerful and expansive and apparently certain that everything was going to go terribly wrong, and soon. “I timed my life perfectly,” Hinton, who is seventy-six, told the class. “I was born just after the end of the Second World War. I was a teen-ager before there was AIDS . And now I’m going to die before the end.”

Most of the several dozen students had not been alive for even a day of the twentieth century; they laughed. In advance of Hinton’s talk, they had read about how A.I. could simplify the engineering of synthetic bioweapons and concentrate surveillance power into the hands of the few, and how a rogue A.I. could relentlessly pursue its goals regardless of the intentions of its makers—the whole grim caboodle. Hinton—who was a leader in the development of machine learning and who, since resigning from Google, last year, has become a public authority on A.I. threats—was asked about the efficacy of safeguards on A.I. “My advice is to be seventy-six,” he said. More laughter. A student followed up with a question about what careers he saw being eliminated by A.I. “It’s the first time I’ve seen anything that makes it good to be old,” he replied. He recommended becoming a plumber. “We all think what’s special about us is our intelligence, but it might be the sort of physiology of our bodies . . . is what’s, in the end, the last thing that’s better,” he said.

I was getting a sense of how Hinton processed existential threat: like the Fool in “King Lear.” And I knew how I processed it: in a Morse code of anxiety and calm, but with less intensity than I think about my pets or about Anna’s Swedish ginger thins. But how did these young people take in, or not take in, all the chatter about A.I. menaces, dying oceans, and nuclear arsenals, in addition to the generally pretty convincing end-times mood over all? I often hear people say that the youth give them hope for the future. This obscures the question of whether young people themselves have hope, or even think in such terms.

Are We Doomed? was made up of undergraduate and graduate students, and met for about three hours on Thursday afternoons. Each week, a guest expert gave a lecture and fielded questions about a topic related to existential risk: nuclear annihilation, climate catastrophe, biothreats, misinformation, A.I. The assigned materials were varied in genre, tone, and perspective. They included a 2023 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; the films “Dr. Strangelove,” by Stanley Kubrick, and “ Wall-E ,” by Pixar; Ursula K. Le Guin’s novel “The Dispossessed”; a publication from the Bipartisan Commission on Biodefense and Max Brooks called “Germ Warfare: A Very Graphic History”; and chapters of “The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity,” by the philosopher Toby Ord.

Daniel Holz, an astrophysicist, and James Evans, a computational scientist and sociologist, co-taught the course. Evans looks like he’s about to give a presentation on conceptual art, and Holz like he’s about to go hiking; both wear jeans. Holz is boyish, brightly melancholy, generous, and gently intense, and Evans is spirited, fun, and intimidatingly well and widely read. Evans and Holz taught Are We Doomed? once before, online, in the spring of 2021. “As difficult as the pandemic was, my mood was better then,” Holz told me in his office, where the most prominent decoration was a framed photograph of a very tall ocean wave. He had conceived of the course after making a series of thrilling research breakthroughs on black holes, neutron stars, and gravitational waves. “I fell into a postpartum depression of sorts,” he said. “I wanted to do something that felt relevant.” In addition to heading an astrophysics research group, Holz is the founding director of the Existential Risk Laboratory (XLab), at the University of Chicago, which describes itself as “dedicated to the analysis and mitigation of risks that threaten human civilization’s long-term survival.” In college, the other path of study that tempted Holz was poetry.

Evans’s research is focussed in part on how knowledge is built, especially scientific knowledge. He is the founder and director of Knowledge Lab, also at the University of Chicago, which uses computational science and other tools to make inquiries that can’t be made by more traditional means. Evans and a co-author recently published an article in Nature which, following the analysis of tens of millions of papers and patents, suggested that the most cited and impactful work is produced by researchers working outside their disciplines—a physicist doing biology, to give one example. Evans also studies complex systems, focussing on what leads them to collapse. He likes, basically, to be surprised, and to be open to surprise. “It was important to Daniel and me that there be a sense of play in the course, that there be a level of comfort with uncertainty and ignorance and being wrong,” Evans told me. It’s hard to envision what the future will look like, he said, because “today just feels like it did yesterday. It doesn’t feel like it’s any different. But there’s the potential for really nonlinear negative outcomes.” “Nonlinear” was a word that became as familiar as toast while I was observing this class—the idea of little changes that, at some threshold, lead to tremendous, possibly catastrophic, shifts.

On the first day of class, Holz told a story that is famous among scientists, though accounts of it vary. About five years after the end of the Second World War, during a visit to Los Alamos, the physicist Enrico Fermi was walking to lunch with a few colleagues. Scientists there were trying to develop a hydrogen bomb, a weapon easily a hundred times more powerful than the atomic bombs that devastated Japan. One of the scientists brought up a New Yorker cartoon that showed aliens unloading Department of Sanitation trash cans from a spaceship. The conversation moved on to other topics. Then Fermi asked, “But where is everybody?” They all laughed; somehow everyone understood that he was talking about aliens. Surely there existed alien life that was sufficiently advanced to say hello, and yet humanity had received no such greeting. How could that be?

The “Where is everybody?” problem came to be known as the Fermi paradox. One of the more compelling responses to the paradox is to ask, Can a civilization become technologically advanced enough to contact us before blowing itself up? For Fermi and his colleagues, the prospect of nuclear annihilation required no imaginative leap.

The average age of the people who worked on the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos was twenty-five, which is not much older than the students in the class at Chicago. The energy and conviction of youth is a superpower, for better and for worse. But young people live on the highest floors of the teetering tower of our civilization, and they will be the last ones to leave the building. They have the most to lose if the stairwells start to crumble.

On a sunny February afternoon, midway through the course, I spoke with some of the students in a conference room on the fourth floor of the building that houses the department of astronomy and astrophysics. The room overlooks a polymorphous Henry Moore sculpture (from different angles it looks like a skull, an army helmet, or a mushroom cloud) and the glass-domed university library, where robots retrieve your books from stacks that run fifty feet down.

Lucy, a senior majoring in math, deadpanned that she was taking the course because it wasn’t math. “And, also, I have an unrealized prepper soul,” she said. Olivia, a senior who designed her major around the question “How do we agreeably disagree?,” had previously taken a class on the history of the bomb. She thought that her interest also had to do with family background. “When you have people in your family who have survived the Holocaust, the question of ‘Are we doomed?’ is a really serious one,” she said. Audrey and Aidan, both physics majors, were especially interested in nuclear risk. Isaiah, a sociology major, said that he valued thinking about problems over the long term, on both a personal and a societal level. Mikko, a graduate student in sociology, had two relatives who worked in the nuclear field, which made him feel close to the topic; he was also invested in how the course related to sustainability. (Later, he told me that his own work was on a very different topic: it was about “shitty food porn” and the online communities in which people post photos of unappetizing food.)

Link copied

The students were talkative, confident, buoyant, very much at ease, and clever. Isaiah, for example, pointed out that “doom” was a pre-modern fire-and-brimstone term, quite different from “risk,” which was tied to modern ideas of chance and probability. In various ways, the students declared the class to be a form of social therapy. Although most described themselves as “pretty pessimistic” or “not a fatalist but not an optimist,” they seemed, as a group, to intuitively inhabit, and occasionally switch, roles: the pragmatist, the persuadable, the expert. But Mikko, who had long hair and black-painted fingernails, and often wore a trenchcoat, was the designated class naysayer. He argued that the question “Are we doomed?” was unproductive, because it obscured a progressive future for climate change. He found it problematic that the A.I. conversation was driven by its makers rather than by the people most affected by the technology. “I’m a natural-born hater,” he said, acknowledging that his fellow-students sometimes looked at him as if he were wearing spurs on a shared life raft.

I was more than charmed by the students, I admit. Their temperaments were brighter than my own, their thoughts more surprising. It was a tiny, unrepresentative group, but they didn’t resemble “young people” as they are portrayed in popular culture. When I asked them whether concern about the environment or other risks was likely to affect their decisions about having families, they looked at me as if I were a pitiable doomer—no, not really.

Holz is the chair of the Science and Security Board of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists , which sets the Doomsday Clock each year. The Bulletin was founded in 1945 by scientists in Chicago who had worked on the Manhattan Project and wanted to increase awareness, they wrote, of the “horrible effects of nuclear weapons and the consequences of using them.” (The first controlled and self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction—led by Fermi—had taken place beneath what was then the University of Chicago football field and is now a library.) The cover of the Bulletin’s first issue as a magazine was a clock set at seven minutes to midnight. The time was chosen, Holz explained, largely because it looked cool. But it was a powerful image; a ticking clock is a classic narrative device for a reason. “The farthest from midnight it ever went was seventeen minutes before midnight, at the end of the Cold War,” Holz said. A humble physical version of the clock—made of what looks to be cardboard and showing only a quarter of a clock face—is kept in a corner on the first floor of a building on the Chicago campus that houses the School of Public Policy and the Bulletin . Currently, the clock shows ninety seconds to midnight, the same as last year, and the closest to midnight it’s ever been.

Holz’s days often include listening to the detailed worries and assessments of non-agreeing experts who devote their lives to thinking about biothreats, nuclear risk, climate change, and perils from emerging technologies. It must, I imagine, feel like being pursued by a comically dogged black cloud. “It’s insane that one person can destroy civilization in thirty minutes, that that is the setup,” Holz said, in passing, while we were waiting for an elevator; no one can veto an American President who decides to launch a nuclear weapon. Yet, if you ask Holz anything about astrophysics, the sun returns. “Black holes are a beacon of hope and light,” he said, visibly pleased by the wordplay. (His papers have titles such as “How Black Holes Get Their Kicks: Gravitational Radiation Recoil Revisited” and “Shouts and Murmurs: Combining Individual Gravitational-Wave Sources with the Stochastic Background to Measure the History of Binary Black Hole Mergers.”) “Cosmology is a consolation, in part because it puts a positive valence on our smallness,” he explained. The universe is magnificent and more than immense, and we’re extremely minor and less than special—and then there are all those civilizations we keep not meeting. Somehow the vast, indifferent cosmos makes Holz feel more inspired to work to give humanity its best chance. “It’s the opposite of nihilism,” he said. “Because we’re not special, the onus is on us to make a difference.”

The students also had their own emotional weather systems. When I spoke to Lawton, a graduate student in international relations and a policy wonk, he said that he was “probably one of the most optimistic people here.” He wanted to work in government, and told me that he was counting on humanity’s desire to survive—that this desire, ultimately, would steer us from disaster. He also told me that he felt pretty different from the other students at Chicago, in part because he had attended a small college in Lakeland, Florida, and was working three part-time jobs, one of which was editing videos—work that, he pointed out lightheartedly, he would presumably soon lose to A.I. As a child, Lawton thought school was fantastic in every way; home was not a great place to be. He said that it was odd to have someone ask his opinion—he hated talking about himself and generally avoided it. When I asked him his age, he replied that he was born in 2000, the Year of the Dragon. I’m a Dragon, too, I told him. That reminded me that I was twice his age. I didn’t feel two Chinese Zodiac cycles older than him—but I did grow up thinking that the microwave was the end point toward which technology had been heading for all those years.

I was curious to learn the students’ first memories of the idea of an end-time. Mikko remembered as a kid seeing a trailer for a reality-TV show on the Discovery Channel, in which contestants battled for survival in faux post-apocalyptic environments. Isaiah recalled losing electricity during Hurricane Sandy. “I remember playing Monopoly by candlelight—at first, it was kind of novel, this lack of technology, but then it was just very depressing, so I think that was kind of when I had the sense that climate change can affect everyone,” he said. He went through a phase in middle school of being very interested in preppers and going deep into related Reddit threads. “Not much happened,” he said, smiling. “I didn’t have an allowance.”

At the start of the sixth week of class, Holz announced a linked film series that would screen at the Gene Siskel Film Center: “Godzilla,” “WarGames,” “Don’t Look Up,” “Contagion.” The visiting guest that week was Jacqueline Feke, a philosophy professor at the University of Waterloo. She guided students through the etymology of “utopia,” a word invented by the philosopher and statesman Thomas More, who was decapitated for treason. “Utopia” is the title of More’s book, from 1516, about an imagined idyllic place—speculative fiction, we might say today. More’s neologism suggested a place (from the Greek topos ) that is nowhere (from the Greek ou , meaning “not”). The readings, which included E. M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” and excerpts from Plato’s Republic, were less harrowing than those of other weeks, when students read chapters from “The Button: The New Nuclear Arms Race and Presidential Power from Truman to Trump,” by William J. Perry and Tom Z. Collina, and “The Uninhabitable Earth,” by David Wallace-Wells.

Imagining utopias, imagining dystopias—how do we get to a better place, or at least avoid getting to a much worse one? During the discussion, Mia, a graduate student in sociology who had experience in the corporate world, brought up “red teaming,” a practice common in tech and national security, in which you ask outsiders to expose your weaknesses—for example, by hacking into your security system. In this manner, red teaming functions like dystopian narratives do, allowing one to consider all the ways that things could go wrong.

But hiring people to hack into a system also lays out a road map for breaking into that system, another student argued. Thinking through how humans might go extinct, or how the world might be destroyed—wasn’t this unreasonably close to plotting human extinction?

“Yeah, it’s like ‘Don’t Create the Torment Nexus,’ ” someone called out, to laughter. This was a meme referring to the idea that if a person dreams up something meant to serve as a cautionary tale—for example, Frank Herbert’s small assassin drones that seek out their targets, from “Dune,” published in 1965—the real-life version will follow soon enough.

“Like, there’s a way that dystopian fiction is a blueprint—”

“It can be aspirational—”

“We’ll end up having a Terminator and a Skynet,” someone else said, in reference to the Arnold Schwarzenegger movies. The discussion was cheerfully derailing, with students interrupting one another.

“So are we thinking that we need to regulate dystopian fiction?” Holz asked sportively.

Evans pushed the logic: “Plato’s Republic says we can’t play music in minor keys because it’s too painful—do we want that?”

No, nobody wanted that, though the students had trouble articulating why.

“Maybe we need to stop teaching this class right now,” Evans proposed. The class laughed. “But we won’t.”

H. G. Wells, in his essay “The Extinction of Man,” writes of the possibility that human civilization might be devastated by “the migratory ants of Central Africa, against which no man can stand.” Wells chose an example that would be difficult to imagine, in part to point out the feebleness of human imagination. Although the term “existential risk” is often attributed to a 2002 paper by the philosopher Nick Bostrom, there is a long, unnamed tradition of thinking about the subject. Among the accomplishments of the sixteenth-century polymath Gerolamo Cardano is the concept that any series of events could have been different—that there was chance, there was probability. It was an intimation—in a time and place more comfortable with fate and God’s will—of how unlikely it was that we came to be, and how it’s not a given that we will continue to be. (Cardano’s mother supposedly tried to abort him; his three older siblings died of the plague.) A more modern formulation of this thinking can be found in the work of the astrophysicist J. Richard Gott, who argues that we can make predictions about how long something will last—be it the Berlin Wall or humanity—on the basis of the idea that we are almost certainly not in a special place in time. Assuming that we are in an “ordinary” place in the history of our species allows us to extrapolate how much longer we will last. Brandon Carter, another astrophysicist, made an analogous argument in the early eighties, using the number of people that have existed and will ever exist as the expanse. These and similar lines of thought have come to fall under the umbrella of the Doomsday Argument. The Doomsday Argument is not about assessing any particular risk—it’s a colder calculation. But it also prompts the question of whether we can steer the ship a bit to the left of the oncoming iceberg. The biologist Rachel Carson’s 1962 book, “Silent Spring,” for example, can be said to grapple with that question.

Jerry Brown, the two-time governor of California and three-time Presidential candidate, was set to speak to the class on a winter afternoon. One student was eating mac and cheese and another was drinking iced tea from a plastic cup with a candy-cane-striped straw. Holz entered the classroom while on a phone call. Brown’s voice could be heard on the other end, asking if “this generation” would know who Daniel Ellsberg was, or would he need to explain? Holz said that the students would know.

When Brown’s face was projected onto the classroom screen, he was red-cheeked and leaning in to the camera. “I don’t see the class,” he said, his voice on speaker. “There’s no audio here.” One of the T.A.s adjusted something on a laptop. Then Brown got going. He had plenty to say. “You’re young. The odds of a nuclear encounter in your lifetime is high,” he told the students. “I don’t want to sugarcoat this.”

Brown, eighty-six years old, spoke with the energy of someone sixty years his junior who has somehow had conversations with Xi Jinping and is deeply knowledgeable about the trillions of dollars spent on military weapons globally. “We’re in a real pickle,” he said. He brought up Ellsberg, a longtime advocate of nuclear disarmament. Ellsberg, who died last June, thought that the most likely scenario leading to nuclear war was a launch happening by mistake, Brown said. There are numerous examples of close calls. In June, 1980, the NORAD missile-warning displays showed twenty-two hundred Soviet nuclear missiles en route to the United States. Zbigniew Brzezinski, Jimmy Carter’s national-security adviser, was alerted by a late-night phone call. Fighter planes had been sent out to search the skies, and launch keys for the U.S.’s ballistic missiles were removed from their safes. Brzezinski had only minutes to decide whether to advise a retaliatory strike. Then he received another phone call: it was a false alarm, a computer glitch—there were no incoming missiles. In 1983, a Soviet early-warning satellite system reported five incoming American missiles. Stanislav Petrov, who was on duty at the command center, convinced his superiors that it was most likely an error; if the Americans were attacking, they wouldn’t have launched so few missiles. In both instances, only a handful of people stood between nuclear holocaust and the status quo.

“A world can go on for thousands of years, and then all hell can break loose,” Brown observed. Nonlinear. He spoke of the Gazans, the Ukrainians, the Jews in Germany in the nineteen-thirties. He spoke of the Native Americans. It wasn’t just a matter of worst fears being realized—it was a matter of catastrophes that had not been foreseen. It was only luck, Brown said, that we had gone seventy-five years without another nuclear bomb being dropped in combat.

The conversation shifted to student questions. What about the nuclear-arms package that Congress had passed? Was there a way to talk about nuclear disarmament without quashing nuclear energy? What did Brown think about the idea that with existential risk there’s no trial and error? How can predictions be made if they aren’t based on events that have happened? The time passed quickly, and Holz asked Brown if he was up for five more minutes. “I’m up for as long as you want,” he said. “We’re talking about the end of the world.”

Nuclear destruction had also been the topic of the first class of the term, when Rachel Bronson, the C.E.O. and president of the Bulletin , was the guest lecturer. In that first class, more than half the students had listed climate change as their foremost concern. By the end of the course, nuclear threats had become more of a concern, and students were speaking about climate change as “a multiplier”—by increasing migration, inequality, and conflict, it could increase the risk of nuclear war.

Toby Ord, who has systematically ranked existential risks, believes that A.I. is the most perilous, assigning to it a one-in-ten chance of ending human potential or life in the next hundred years. (He describes his assessments as guided by “an accumulation of knowledge and judgment” and necessarily not precise.) To nuclear technology, he assigns a one-in-a-thousand chance, and to all risks combined a one-in-six chance. “Safeguarding humanity’s future is the defining challenge of our time,” he writes. Ord arrived at his concerns in an interesting way; as a philosopher of ethics, his focus was on our responsibility to the most poor and vulnerable. He then extended the line of thinking: “I came to realize . . . that the people of the future may be even more powerless to protect themselves from the risks we impose.”

“I think about the Fermi paradox literally every day,” Olivia told me near the end of the course. “When you break down the notion that it’s not going to be aliens from other planets that will be the end of us, but instead potentially us , in our lack of responsibility . . .” But she wasn’t fearful or anxious. “I’d say I’m more interested in how we cope with existential threats than in the threats themselves.”

Finals week arrived. It’s like the world stops for finals, one student said, of the atmosphere on campus. Evans was doing downward dogs during a break in class; Holz was drinking a Coke. Both seemed discreetly tired, like parents nearing the end of their kids’ school sports tournament. The class had been a kind of high for everyone. And soon it would be over. The students had been working on their final projects; the assignment was to respond creatively to the themes of the class. In the 2021 course, a student wrote and illustrated a version of the children’s classic “Goodnight Moon” which was “adapted for doom.” (“Goodnight progress / And goodnight innovation / Goodnight conflict / Goodnight salvation.”) One group made a portfolio of homes offered for sale by Doomsday International Realty: a luxury nuclear bunker, a single-family home on the moon.

Lucy and three classmates were putting together syllabi that imagined what Are We Doomed? classes might look like at different points in time: the Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution, and the year 2054. The majority of Lucy’s contributions had been to the Industrial Revolution syllabus. Alexander Graham Bell was the guest lecturer on technology and society, and the readings for his week included works by John Stuart Mill, various Luddites, and Thomas Carlyle. Lucy spoke of how Carlyle wrote with alarm, in “Signs of the Times,” about what had been lost to mechanization, the decline of church power, and how public opinion was becoming a kind of police force—observations that, she pointed out, are still relevant. Everything was going to hell, and always has been. A question that came up repeatedly in class discussions was whether our current moment is distinctively risky; most experts argue that it is.

Lawton was working with two friends on a doomsday video game, in which a player makes a series of decisions that move the world closer to or farther from nuclear destruction. “You have three advisers: a scientist, a military chief of staff, and a monocled campaign manager who is focussed entirely on getting you reëlected,” he said. After facing these decisions, each with difficult trade-offs, the player receives an update on how various dangers—nuclear war, climate change, A.I., biothreats—have advanced or receded. If your decisions lead to nuclear annihilation, the screen reads “The last humans cower in vaults and caves, knowing they are witnessing their own extinction.”

Mikko, too, had incorporated a game into his final project. Holz had asked the class to think about how effective the Doomsday Clock was in drawing attention to existential risk. Mikko and his project partner wanted to develop graphics that would better communicate the idea of climate change as a progressive existential threat. “We are already knee-deep, and it’s about mitigation and adaptation,” he said. He thought that the Doomsday Clock, while effective, had a nihilistic feel: even though the time on it can be changed in either direction, our human experience is of time ceaselessly moving forward, which makes nuclear Armageddon feel like a foregone conclusion. The game Snakes and Ladders was an inspiration for one of the graphics, which included a stylized ladder. “More rungs can be added to the ladder or removed from it,” Mikko said, explaining that this made it focussed on action. With climate, he feels that it is not only counterproductive “but also a kind of cowardice” to give up. We can never go back to what we had before, he said, but that was “a prelapsarian ideal about being pushed out of the Garden of Eden.” In his own way, the nay-saying Mikko sounded like what most of us would call an optimist.

I decided to rewatch “La Jetée,” by Chris Marker, a short film from 1962 that was on the syllabus for the week of “Pandemics & Other Biological Threats.” In “La Jetée,” the protagonist is part of a science experiment that requires time travel to the past. But he must also travel to the future, so that he can bring back technology to save the present from a disastrous world war, left mostly undetailed, that has already occurred. The protagonist prefers returning to the past, where he has—as one does in French films from the nineteen-sixties—become close with a beautiful woman whom, before the time-travel experiments, he had seen only once.