- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.4: The Body of the Research Proposal

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 180380

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Drawing on guidelines developed in the UBC graduate guide to writing proposals (Petrina, 2009), we highlight eight steps for constructing an effective research proposal:

- Presenting the topic

- Literature Review

- Identifying the Gap

- Research Questions that addresses the Gap

- Methods to address the research questions

Data Analysis

- Summary, Limitations and Implications

In addition to those eight sections, research proposals frequently include a research timeline. We discuss each of these eight sections as well as producing a research timeline below.

Presenting The Topic (Statement of Research Problem)

The research proposal should begin with a hook to entice your readers. Like a steaming fresh pie on a windowsill, you want to allure your reader by presenting your topic (the pie on the sill) and then alluding to its importance (the delicious scent and taste of the cooling cherry pie). This can be done in many ways, so long as you are able to entice your reader to the core themes of your research. Some suggestions include:

Highlighting a paradox that your work will attempt to resolve e.g., “Why is it that social research has been shown to bring about higher net-positive outcomes than natural scientific research, but is funded less?” or “Why is it that women earn less than men in meritocratic societies even though they have more qualifications?” Paradoxes are popular because they draw on problematics (see Chapter 1) and indicate an obstacle in the thinking of fellow researchers that you may offer hope in resolving.

- Presenting a narrative introduction (often used in ethnographic papers) to the problem at hand. The following opening statement from Bowen, Elliott & Brenton (2014, p. 20) illustrates:

It’s a hot, sticky Fourth of July in North Carolina, and Leanne, a married working-class black mother of three, is in her cramped kitchen. She’s been cooking for several hours, lovingly preparing potato salad, beef ribs, chicken legs, and collards for her family. Abruptly, her mother decides to leave before eating anything. “But you haven’t eaten,” Leanne says. “You know I prefer my own potato salad,” says her mom. She takes a plateful to go anyway,

- Provide an historical overview of the problem, discussing its significance in history and indicating how that interrelates to the present: “On January 23rd, 2020, tears were shed as cabbies heard the news of Uber’s approval to operate in the city of Vancouver.”

- Introduce your positionality to the problem: How did it come of concern? How are you personally related to the social problem in question? The following introduction by Germon (1999, p.687) illustrates:

Throughout the paper I locate myself as part of the disabled peoples movement, and write from a position of a shared value base and analyses of a collective experience. In doing so, I make no apology for flouting academic pretentions of objectivity and neutrality. Rather, I believe I am giving essential information which clarifies my motivation and political position

- Begin with a quotation : Because this is an overused technique, if you use it, make sure that it addresses your research question and that you can explicitly relate to it in the body of your introduction. Do not start with a quotation for the sake of.

- Begin with a concession : Start with a statement recognizing an opinion or approach different from the one you plan to take in your thesis. You can acknowledge the merits in a previous approach but show how you will improve it or make a different argument, e.g., “Although critical theory and antiracism explain oppression and exploitation in contemporary society, they do not fully address the experiences of Indigenous peoples”.

- Start with an interesting fact or statistics : This is a sure way to draw attention to the topic and its significance e.g. “Canada is the fourth most popular destination country in the world for international students in 2018, with close to half a million international students” (CBIE, 2018)

- A definition : You may start by defining a key term in your research topic. This is useful if it distinguishes how you plan to use a term or concept in your thesis.

The above strategies are not exhaustive nor are they only applicable to the introduction of your research proposal. They can be used to introduce any section of your thesis or any paper. Regardless of the strategy that you use to introduce your topic, remember that the key objective is to convince your reader that the issue is problematic and is worth investigating. A well developed statement of research problem will do the following:

- Contextualize the problem . This means highlighting what is already known and how it is problematic to the specific context in which you wish to study it. By highlighting what is already known, you can build on key facts (such as the prevalence and whether it has received attention in the past). Please note that this is not the literature review; you are simply fleshing out a few pertinent details to introduce the topic in a few sentences or a paragraph.

- Specify the problem by describing precisely what you plan to address. In other words, elaborate on what we need to know. For example, building on your contextualization of the problem, you can specify the problem with a statement such as: “There is an abundance of literature on international migration. In fact, the IOM (2018) estimates that there are close to 258 million international migrants globally, who contribute billions to the global economy. However, not much is known about the extent of intra-regional migration in the global south such as within the African continent. There is, hence, a pressing need to study this phenomenon in greater detail.”

- Highlight the relevance of the problem . This means explaining to the readers why we need to know this information, who will be affected, who will benefit?

- Outline the goal and objectives of the research.

- The goal of your research is what you hope to achieve by answering the research question. To write the goal of your research, go back to your research question and state the results you intend to obtain. For example, if your research question is “What effect does extended social media use have on female body images?”, the goal of your research could be stated as “The goal of this study is to identity the point at which social media use negatively impact female body images so that they can be informed about how to use it responsibly.

- The objectives of your study is a further elaboration on your goals i.e., details about the steps that you will take to achieve the goal. Based on the goal above, you probably will study incidents of depression among female social media users, changes in self-esteem and incidents of eating disorders. These could translate into objectives such as to: (1) compare the incidents of depression among female social media users based on length of use (2) assess changes in female social media users’ self esteem (3) determine if there are differences in the incidents of eating disorder among female social media users based on extent of use. Notice that in achieving those objectives, you will be able to reach the goal of answering your research question.

In summary, you should strive to have one goal for each research question. If your project has only one research question, one goal is sufficient. Your objectives are the pathways (or steps) that will get you to achieve the goal i.e., what will you need to do in order to answer the research question. Summarize the steps in no more than two or three objectives per goal.

Brief Literature Review

After the problem and rationale are introduced, the next step is to frame the problem within the academic discourse. This involves conducting a preliminary literature review covering, inter alia, the history of the phenomena itself and the scholarly theories and investigations that have attempted to understand it (Petrina, 2009). In elaborating on the history of the concepts and theories, you should also attempt to draw attention to the theories which will guide your own research (or which will be contested by your research). By foregrounding the major ways of perceiving the problem, you will then set the stage for your own methodology: the major concepts and tools you will use to investigate/interpret the problem.

While in graduate research proposals the literature review often composes a section of its own (Petrina, 2009), in undergraduate research this step can be incorporated into the introduction. However, you should avoid, as Wong (n.d.) writes, framing your research question “in the context of a general, rambling literature review,” where your research question “may appear trivial and uninteresting.” Try to respond to seminal papers in the literature and to identify clearly for your reader the key concepts in the literature that you will be discussing. Part of outlining the scholarly discussion should also focus on clarifying the boundaries of your topic. While making the significance concrete, try to hone in on select themes that your research will evaluate. This way, when you go to outline the methods you will use, the topic will have clearly defined boundaries and concerns. See chapter 5 for more guidance on how to construct an extended literature review.

Box 2.1 – Tips for the Literature Review

- Summarize : The literature in your literature review is not going to be exhaustive but it should demonstrate that you have a good grasp on key debates and trends in the field

- Quality not quantity : Despite the fact that this is non-exhaustive, there is no magic number of sources that you need. Do not think in terms of how many sources are sufficient. Think about presenting a decent representation of key themes in the literature.

- Highlight theory and methodology of your sources (if they are significant). Doing so could help justify your theoretical and methodological decisions, whether you are departing from previous approaches or whether you are adopting them.

- Synthesize your results. Do not simply state “According to Robinson (2021)….According to Wilson (2021)… etc”. Instead, find common grounds between sources and summarize the point e.g., “Researchers argue that we should not list our literature (Bartolic, 2021; Robinson, 2020; Wilson 2021).

- Justify methodological choice

- Assess and Evaluate: After assessing the literature in your field, you should be able to answer the following questions: Why should we study (further) this research topic/problem?

- Contribution : At the end of the literature, you should be able to determine contributions will my study make to the existing literature?

As you briefly discuss the key literature concerning your topic of interest, it is important that you allude to gaps. Gaps are ambiguities, faults, and missing aspects of previous studies. Think about questions that you have which are not answered by existing literature. Specifically, think about how the literature might insufficiently address the following, and locate your research as filling those gaps (see UNE, 2021):

- Population or sample : size, type, location, demography etc. [Are there specific populations that are understudied e.g., Indigenous people, female youth, BIPOC, the elderly etc.]

- Research methods : qualitative, quantitative, or mixed [Has the research in the area been limited to just a few methods e.g., all surveys? How is yours different?]

- Data analysis [Are you using a different method of analysis than those used in the literature?]

- Variables or conditions [Are you examining a new or different set of variables than those previously studied? Are the conditions under which your study is being conducted unique e.g., under pandemic conditions]

- Theory [Are you employing a theory in a new way?]

Refer to Chapter 6 (Literature Review) for more detail about this process and for a discussion on common types of gaps in social research.

Box 2.2 – Identifying a Gap

To indicate the usefulness and originality of your research, you should be conscious of how your research is both unique from previous studies in the field and how its findings will be useful. When you write your thesis or research report, you will expound on these gaps some more. However, in the body of your proposal, it is important that you explicitly highlight the insufficiency of existing literature (i.e. gaps). Below are some phrases that you can use to indicate gaps:

- …has not been clarified, studied, reported, or elucidated

- further research is required or needed

- …is not well reported

- key question(s) remains unanswered

- it is important to address …

- …poorly understood or known

- Few studies have (UNE, 2021)

Research Questions & Research Questions that Address the Gap

The gaps and literature you outline should set the context for your research questions. In outlining the major issues concerning your topic, you should have raised key concepts and actors (Wong, n.d.). Your research question should attempt to engage or investigate the key concepts previously stated, showing to your reader that you have developed a line of inquiry that directly touches upon gaps in the previous literature that can be concretely investigated (ie. concepts that are operationalized). After indicating what your research intends to study, formulate this gap into a set of research questions which make investigating this gap tangible. Refer to the previous chapter for more advice about devising a solid research question. Remember, as McCombes (2021) notes, a good research question is:

- Focused on a single problem or issue

- Researchable using primary and/or secondary sources

- Feasible to answer within the timeframe and practical constraints

- Specific enough to answer thoroughly

- Complex enough to develop the answer over the space of a paper or thesis (i.e., not answerable with a simple yes/no)

- Provide scope for debate Original (not one that is answered already)

- Relevant to your field of study and/or society more broadly.

Methods to Address Research Questions

By the time you begin writing your methodology section, you would have already introduced your topic and its significance, and have provided a brief account of its scholarly history (literature review) and the gaps you will be filling. The methods section allows you to discuss how you intend to fulfill said gap. In the methods section, you also indicate what data you intend to investigate (content: including the time, place, and variables) and how you intend to find it (the methods you will use to reveal content e.g., qualitative interviewing, discourse analysis, experimental research, and comparative research). Your ability to outline these steps clearly and plausibly will indicate whether your research is repeatable, possible, and effective. Repeatable research allows other researchers to repeat your methods and find the same results (Bhattacherjee, 2012), thereby proving that your findings were not invented but are discoverable by all. Your descriptions must be specific enough so that other researchers can repeat them and arrive at the same results. It is important in this section that you also justify why you believe this specific methodology is the most effective for answering the research question. This does not need to be extensive, but you should at least briefly note why you think, for instance, qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods (and your specific proposed approach) are appropriate for answering your research question. For more details about writing an immaculate methodology, refer to Chapter 7.

This short section requires you to discuss how you intend to interpret your findings. You will need to ask yourself five critical questions before you write this section: (1) will theory guide the interpretation of the results? (2) Will I use a matrix with pre-established codes to categorize results? (3) Will I use an inductive approach such as grounded theory that does not go into an investigation with strict codes? (4) Will I use statistics to explain trends in numerical data? (5) Will I be using a combination of these or another strategy to interpret my findings?This section should also include some discussion of the theories that you intend to use to possibly explain or understand your data. Be sure to outline key notions and explain how they will be operationalized to extrapolate the data you may receive. Again, this section also does not have to be extensive. At this point, you are demonstrating that you have given thought to what you intend to do with the data once you have collected it. This may change later on, but make sure that the proposed analytical strategy is appropriate to the data collected, for example, if you are evaluating newspaper discourse on the coronavirus pandemic, unless you intend to code the data quantitatively, you would not be expected to use statistics. Content, thematic or discourse analysis might be more intuitive. See the Data Analysis (Chapters 9 and 10) for more details.

Summarize, Engage with Limitations, and Implicate

After you have outlined the literature, the gaps in the literature, how you intend to investigate that gap, and how you intend to analyze what you have found, it is important to again reiterate the significance of your study. Allude to what your study could find and what this would mean . This requires returning to the significant territory that began your proposal and linking it to how your study could help to explain/change this understanding or circumstance. Report on the possible beneficial outcomes of your study. For instance, say you study the impact of welfare checks on homelessness. Then you could respond to the following question: How could my findings improve our responses to homelessness? How could it make welfare policies more effective? Remember you must explain the usefulness or benefits of the study to both the outside world and the research community. In addition to noting your strengths, also reflect on the weaknesses. All research has limitations but you need to demonstrate that you have taken steps to mitigate those that can be mitigated and that the research is valuable despite the weaknesses. Be straightforward about the things your study will not be able to find, and the potential obstacles that will be presented to you in conducting your study (in research that is conducted with a population, be sure to note harms/benefits that might come to them). With this in mind, try to address these obstacles to the best of your ability and to prove the value of your study despite inevitable tradeoffs. However, do not finish with a long list of inadequacies. End with a magnanimous crescendo –with the impression that despite the trials and limitations of research, you are prepared for the challenge and the challenge is well worth overcoming. This means reiterating the significance, potential uses and implications of the findings.

Box 2.3 – Seven Tips for Getting Started with Your Proposed Methodology

- Introduce the overall methodological approach (e.g., qualitative, quantitative, mixed)

- Indicate how the approach fits the overall research design (e.g., setting, participants, data collection process)

- Describe the specific methods of data collection (e.g., interviews, surveys, ethnography, secondary data etc.)

- Explain how you intend to analyze and interpret your results (i.e. statistical analysis, grounded theory; outline any theoretical framework that will guide the analysis; see below ).

- If necessary, provide background and rationale for unfamiliar methodologies.

- Highlight the ethical process including whether institutional ethics review was done

- Address potential limitations ( see below )

Bhattacherjee, Anol. (2012). Social Science Research: Principles, Methods, and Practices Textbooks Collection. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1002&context=oa_textbooks

Bowen, S., Elliott, S., & Brenton, J. (2014). The joy of cooking? Contexts , 13(3), 20-25.

CBIE [Canadian Bureau for International Education] (2018, August). International students in Canada . https://cbie.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/International-Students-in-CanadaENG.pdf

Germon, P. (1999). Purely academic? Exploring the relationship between theory and political activism. Disability & Society, 14(5), 687-692.

International Organization on Migration. (2018). “Global Migration Indicators.” global_migration_indicators_2018.pdf (iom.int)

McCombes, S. (2021, March 22). Developing Strong Research Questions: Criteria and Examples. Scribbr . https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-questions/

UNE (2021). Gaps in the literature. UNE Library services. https://library.une.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Gaps-in-the-Literature.pdf

Petrina, Stephen. (2009). “Thesis Dissertation and Proposal Guide For Graduate Students.”

https://edcp-educ.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2013/08/researchproposal1.pdf

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

The goal of a research proposal is twofold: to present and justify the need to study a research problem and to present the practical ways in which the proposed study should be conducted. The design elements and procedures for conducting research are governed by standards of the predominant discipline in which the problem resides, therefore, the guidelines for research proposals are more exacting and less formal than a general project proposal. Research proposals contain extensive literature reviews. They must provide persuasive evidence that a need exists for the proposed study. In addition to providing a rationale, a proposal describes detailed methodology for conducting the research consistent with requirements of the professional or academic field and a statement on anticipated outcomes and benefits derived from the study's completion.

Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005.

How to Approach Writing a Research Proposal

Your professor may assign the task of writing a research proposal for the following reasons:

- Develop your skills in thinking about and designing a comprehensive research study;

- Learn how to conduct a comprehensive review of the literature to determine that the research problem has not been adequately addressed or has been answered ineffectively and, in so doing, become better at locating pertinent scholarship related to your topic;

- Improve your general research and writing skills;

- Practice identifying the logical steps that must be taken to accomplish one's research goals;

- Critically review, examine, and consider the use of different methods for gathering and analyzing data related to the research problem; and,

- Nurture a sense of inquisitiveness within yourself and to help see yourself as an active participant in the process of conducting scholarly research.

A proposal should contain all the key elements involved in designing a completed research study, with sufficient information that allows readers to assess the validity and usefulness of your proposed study. The only elements missing from a research proposal are the findings of the study and your analysis of those findings. Finally, an effective proposal is judged on the quality of your writing and, therefore, it is important that your proposal is coherent, clear, and compelling.

Regardless of the research problem you are investigating and the methodology you choose, all research proposals must address the following questions:

- What do you plan to accomplish? Be clear and succinct in defining the research problem and what it is you are proposing to investigate.

- Why do you want to do the research? In addition to detailing your research design, you also must conduct a thorough review of the literature and provide convincing evidence that it is a topic worthy of in-depth study. A successful research proposal must answer the "So What?" question.

- How are you going to conduct the research? Be sure that what you propose is doable. If you're having difficulty formulating a research problem to propose investigating, go here for strategies in developing a problem to study.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Failure to be concise . A research proposal must be focused and not be "all over the map" or diverge into unrelated tangents without a clear sense of purpose.

- Failure to cite landmark works in your literature review . Proposals should be grounded in foundational research that lays a foundation for understanding the development and scope of the the topic and its relevance.

- Failure to delimit the contextual scope of your research [e.g., time, place, people, etc.]. As with any research paper, your proposed study must inform the reader how and in what ways the study will frame the problem.

- Failure to develop a coherent and persuasive argument for the proposed research . This is critical. In many workplace settings, the research proposal is a formal document intended to argue for why a study should be funded.

- Sloppy or imprecise writing, or poor grammar . Although a research proposal does not represent a completed research study, there is still an expectation that it is well-written and follows the style and rules of good academic writing.

- Too much detail on minor issues, but not enough detail on major issues . Your proposal should focus on only a few key research questions in order to support the argument that the research needs to be conducted. Minor issues, even if valid, can be mentioned but they should not dominate the overall narrative.

Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sanford, Keith. Information for Students: Writing a Research Proposal. Baylor University; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences, Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Structure and Writing Style

Beginning the Proposal Process

As with writing most college-level academic papers, research proposals are generally organized the same way throughout most social science disciplines. The text of proposals generally vary in length between ten and thirty-five pages, followed by the list of references. However, before you begin, read the assignment carefully and, if anything seems unclear, ask your professor whether there are any specific requirements for organizing and writing the proposal.

A good place to begin is to ask yourself a series of questions:

- What do I want to study?

- Why is the topic important?

- How is it significant within the subject areas covered in my class?

- What problems will it help solve?

- How does it build upon [and hopefully go beyond] research already conducted on the topic?

- What exactly should I plan to do, and can I get it done in the time available?

In general, a compelling research proposal should document your knowledge of the topic and demonstrate your enthusiasm for conducting the study. Approach it with the intention of leaving your readers feeling like, "Wow, that's an exciting idea and I can’t wait to see how it turns out!"

Most proposals should include the following sections:

I. Introduction

In the real world of higher education, a research proposal is most often written by scholars seeking grant funding for a research project or it's the first step in getting approval to write a doctoral dissertation. Even if this is just a course assignment, treat your introduction as the initial pitch of an idea based on a thorough examination of the significance of a research problem. After reading the introduction, your readers should not only have an understanding of what you want to do, but they should also be able to gain a sense of your passion for the topic and to be excited about the study's possible outcomes. Note that most proposals do not include an abstract [summary] before the introduction.

Think about your introduction as a narrative written in two to four paragraphs that succinctly answers the following four questions :

- What is the central research problem?

- What is the topic of study related to that research problem?

- What methods should be used to analyze the research problem?

- Answer the "So What?" question by explaining why this is important research, what is its significance, and why should someone reading the proposal care about the outcomes of the proposed study?

II. Background and Significance

This is where you explain the scope and context of your proposal and describe in detail why it's important. It can be melded into your introduction or you can create a separate section to help with the organization and narrative flow of your proposal. Approach writing this section with the thought that you can’t assume your readers will know as much about the research problem as you do. Note that this section is not an essay going over everything you have learned about the topic; instead, you must choose what is most relevant in explaining the aims of your research.

To that end, while there are no prescribed rules for establishing the significance of your proposed study, you should attempt to address some or all of the following:

- State the research problem and give a more detailed explanation about the purpose of the study than what you stated in the introduction. This is particularly important if the problem is complex or multifaceted .

- Present the rationale of your proposed study and clearly indicate why it is worth doing; be sure to answer the "So What? question [i.e., why should anyone care?].

- Describe the major issues or problems examined by your research. This can be in the form of questions to be addressed. Be sure to note how your proposed study builds on previous assumptions about the research problem.

- Explain the methods you plan to use for conducting your research. Clearly identify the key sources you intend to use and explain how they will contribute to your analysis of the topic.

- Describe the boundaries of your proposed research in order to provide a clear focus. Where appropriate, state not only what you plan to study, but what aspects of the research problem will be excluded from the study.

- If necessary, provide definitions of key concepts, theories, or terms.

III. Literature Review

Connected to the background and significance of your study is a section of your proposal devoted to a more deliberate review and synthesis of prior studies related to the research problem under investigation . The purpose here is to place your project within the larger whole of what is currently being explored, while at the same time, demonstrating to your readers that your work is original and innovative. Think about what questions other researchers have asked, what methodological approaches they have used, and what is your understanding of their findings and, when stated, their recommendations. Also pay attention to any suggestions for further research.

Since a literature review is information dense, it is crucial that this section is intelligently structured to enable a reader to grasp the key arguments underpinning your proposed study in relation to the arguments put forth by other researchers. A good strategy is to break the literature into "conceptual categories" [themes] rather than systematically or chronologically describing groups of materials one at a time. Note that conceptual categories generally reveal themselves after you have read most of the pertinent literature on your topic so adding new categories is an on-going process of discovery as you review more studies. How do you know you've covered the key conceptual categories underlying the research literature? Generally, you can have confidence that all of the significant conceptual categories have been identified if you start to see repetition in the conclusions or recommendations that are being made.

NOTE: Do not shy away from challenging the conclusions made in prior research as a basis for supporting the need for your proposal. Assess what you believe is missing and state how previous research has failed to adequately examine the issue that your study addresses. Highlighting the problematic conclusions strengthens your proposal. For more information on writing literature reviews, GO HERE .

To help frame your proposal's review of prior research, consider the "five C’s" of writing a literature review:

- Cite , so as to keep the primary focus on the literature pertinent to your research problem.

- Compare the various arguments, theories, methodologies, and findings expressed in the literature: what do the authors agree on? Who applies similar approaches to analyzing the research problem?

- Contrast the various arguments, themes, methodologies, approaches, and controversies expressed in the literature: describe what are the major areas of disagreement, controversy, or debate among scholars?

- Critique the literature: Which arguments are more persuasive, and why? Which approaches, findings, and methodologies seem most reliable, valid, or appropriate, and why? Pay attention to the verbs you use to describe what an author says/does [e.g., asserts, demonstrates, argues, etc.].

- Connect the literature to your own area of research and investigation: how does your own work draw upon, depart from, synthesize, or add a new perspective to what has been said in the literature?

IV. Research Design and Methods

This section must be well-written and logically organized because you are not actually doing the research, yet, your reader must have confidence that you have a plan worth pursuing . The reader will never have a study outcome from which to evaluate whether your methodological choices were the correct ones. Thus, the objective here is to convince the reader that your overall research design and proposed methods of analysis will correctly address the problem and that the methods will provide the means to effectively interpret the potential results. Your design and methods should be unmistakably tied to the specific aims of your study.

Describe the overall research design by building upon and drawing examples from your review of the literature. Consider not only methods that other researchers have used, but methods of data gathering that have not been used but perhaps could be. Be specific about the methodological approaches you plan to undertake to obtain information, the techniques you would use to analyze the data, and the tests of external validity to which you commit yourself [i.e., the trustworthiness by which you can generalize from your study to other people, places, events, and/or periods of time].

When describing the methods you will use, be sure to cover the following:

- Specify the research process you will undertake and the way you will interpret the results obtained in relation to the research problem. Don't just describe what you intend to achieve from applying the methods you choose, but state how you will spend your time while applying these methods [e.g., coding text from interviews to find statements about the need to change school curriculum; running a regression to determine if there is a relationship between campaign advertising on social media sites and election outcomes in Europe ].

- Keep in mind that the methodology is not just a list of tasks; it is a deliberate argument as to why techniques for gathering information add up to the best way to investigate the research problem. This is an important point because the mere listing of tasks to be performed does not demonstrate that, collectively, they effectively address the research problem. Be sure you clearly explain this.

- Anticipate and acknowledge any potential barriers and pitfalls in carrying out your research design and explain how you plan to address them. No method applied to research in the social and behavioral sciences is perfect, so you need to describe where you believe challenges may exist in obtaining data or accessing information. It's always better to acknowledge this than to have it brought up by your professor!

V. Preliminary Suppositions and Implications

Just because you don't have to actually conduct the study and analyze the results, doesn't mean you can skip talking about the analytical process and potential implications . The purpose of this section is to argue how and in what ways you believe your research will refine, revise, or extend existing knowledge in the subject area under investigation. Depending on the aims and objectives of your study, describe how the anticipated results will impact future scholarly research, theory, practice, forms of interventions, or policy making. Note that such discussions may have either substantive [a potential new policy], theoretical [a potential new understanding], or methodological [a potential new way of analyzing] significance. When thinking about the potential implications of your study, ask the following questions:

- What might the results mean in regards to challenging the theoretical framework and underlying assumptions that support the study?

- What suggestions for subsequent research could arise from the potential outcomes of the study?

- What will the results mean to practitioners in the natural settings of their workplace, organization, or community?

- Will the results influence programs, methods, and/or forms of intervention?

- How might the results contribute to the solution of social, economic, or other types of problems?

- Will the results influence policy decisions?

- In what way do individuals or groups benefit should your study be pursued?

- What will be improved or changed as a result of the proposed research?

- How will the results of the study be implemented and what innovations or transformative insights could emerge from the process of implementation?

NOTE: This section should not delve into idle speculation, opinion, or be formulated on the basis of unclear evidence . The purpose is to reflect upon gaps or understudied areas of the current literature and describe how your proposed research contributes to a new understanding of the research problem should the study be implemented as designed.

ANOTHER NOTE : This section is also where you describe any potential limitations to your proposed study. While it is impossible to highlight all potential limitations because the study has yet to be conducted, you still must tell the reader where and in what form impediments may arise and how you plan to address them.

VI. Conclusion

The conclusion reiterates the importance or significance of your proposal and provides a brief summary of the entire study . This section should be only one or two paragraphs long, emphasizing why the research problem is worth investigating, why your research study is unique, and how it should advance existing knowledge.

Someone reading this section should come away with an understanding of:

- Why the study should be done;

- The specific purpose of the study and the research questions it attempts to answer;

- The decision for why the research design and methods used where chosen over other options;

- The potential implications emerging from your proposed study of the research problem; and

- A sense of how your study fits within the broader scholarship about the research problem.

VII. Citations

As with any scholarly research paper, you must cite the sources you used . In a standard research proposal, this section can take two forms, so consult with your professor about which one is preferred.

- References -- a list of only the sources you actually used in creating your proposal.

- Bibliography -- a list of everything you used in creating your proposal, along with additional citations to any key sources relevant to understanding the research problem.

In either case, this section should testify to the fact that you did enough preparatory work to ensure the project will complement and not just duplicate the efforts of other researchers. It demonstrates to the reader that you have a thorough understanding of prior research on the topic.

Most proposal formats have you start a new page and use the heading "References" or "Bibliography" centered at the top of the page. Cited works should always use a standard format that follows the writing style advised by the discipline of your course [e.g., education=APA; history=Chicago] or that is preferred by your professor. This section normally does not count towards the total page length of your research proposal.

Develop a Research Proposal: Writing the Proposal. Office of Library Information Services. Baltimore County Public Schools; Heath, M. Teresa Pereira and Caroline Tynan. “Crafting a Research Proposal.” The Marketing Review 10 (Summer 2010): 147-168; Jones, Mark. “Writing a Research Proposal.” In MasterClass in Geography Education: Transforming Teaching and Learning . Graham Butt, editor. (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015), pp. 113-127; Juni, Muhamad Hanafiah. “Writing a Research Proposal.” International Journal of Public Health and Clinical Sciences 1 (September/October 2014): 229-240; Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005; Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Punch, Keith and Wayne McGowan. "Developing and Writing a Research Proposal." In From Postgraduate to Social Scientist: A Guide to Key Skills . Nigel Gilbert, ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2006), 59-81; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences , Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- << Previous: Writing a Reflective Paper

- Next: Generative AI and Writing >>

- Last Updated: May 7, 2024 9:45 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper: Writing a Research Proposal

- Purpose of Guide

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- The Research Problem/Question

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Evaluating Sources

- Reading Research Effectively

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- What Is Scholarly vs. Popular?

- Is it Peer-Reviewed?

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism [linked guide]

- Annotated Bibliography

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

The goal of a research proposal is to present and justify the need to study a research problem and to present the practical ways in which the proposed study should be conducted. The design elements and procedures for conducting the research are governed by standards within the predominant discipline in which the problem resides, so guidelines for research proposals are more exacting and less formal than a general project proposal. Research proposals contain extensive literature reviews. They must provide persuasive evidence that a need exists for the proposed study. In addition to providing a rationale, a proposal describes detailed methodology for conducting the research consistent with requirements of the professional or academic field and a statement on anticipated outcomes and/or benefits derived from the study's completion.

Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005.

How to Approach Writing a Research Proposal

Your professor may assign the task of writing a research proposal for the following reasons:

- Develop your skills in thinking about and designing a comprehensive research study;

- Learn how to conduct a comprehensive review of the literature to ensure a research problem has not already been answered [or you may determine the problem has been answered ineffectively] and, in so doing, become better at locating scholarship related to your topic;

- Improve your general research and writing skills;

- Practice identifying the logical steps that must be taken to accomplish one's research goals;

- Critically review, examine, and consider the use of different methods for gathering and analyzing data related to the research problem; and,

- Nurture a sense of inquisitiveness within yourself and to help see yourself as an active participant in the process of doing scholarly research.

A proposal should contain all the key elements involved in designing a completed research study, with sufficient information that allows readers to assess the validity and usefulness of your proposed study. The only elements missing from a research proposal are the findings of the study and your analysis of those results. Finally, an effective proposal is judged on the quality of your writing and, therefore, it is important that your writing is coherent, clear, and compelling.

Regardless of the research problem you are investigating and the methodology you choose, all research proposals must address the following questions:

- What do you plan to accomplish? Be clear and succinct in defining the research problem and what it is you are proposing to research.

- Why do you want to do it? In addition to detailing your research design, you also must conduct a thorough review of the literature and provide convincing evidence that it is a topic worthy of study. Be sure to answer the "So What?" question.

- How are you going to do it? Be sure that what you propose is doable. If you're having trouble formulating a research problem to propose investigating, go here .

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Failure to be concise; being "all over the map" without a clear sense of purpose.

- Failure to cite landmark works in your literature review.

- Failure to delimit the contextual boundaries of your research [e.g., time, place, people, etc.].

- Failure to develop a coherent and persuasive argument for the proposed research.

- Failure to stay focused on the research problem; going off on unrelated tangents.

- Sloppy or imprecise writing, or poor grammar.

- Too much detail on minor issues, but not enough detail on major issues.

Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal . The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sanford, Keith. Information for Students: Writing a Research Proposal . Baylor University; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal . International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences, Articles, and Books . The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal . University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Structure and Writing Style

Beginning the Proposal Process

As with writing a regular academic paper, research proposals are generally organized the same way throughout most social science disciplines. Proposals vary between ten and twenty-five pages in length. However, before you begin, read the assignment carefully and, if anything seems unclear, ask your professor whether there are any specific requirements for organizing and writing the proposal.

A good place to begin is to ask yourself a series of questions:

- What do I want to study?

- Why is the topic important?

- How is it significant within the subject areas covered in my class?

- What problems will it help solve?

- How does it build upon [and hopefully go beyond] research already conducted on the topic?

- What exactly should I plan to do, and can I get it done in the time available?

In general, a compelling research proposal should document your knowledge of the topic and demonstrate your enthusiasm for conducting the study. Approach it with the intention of leaving your readers feeling like--"Wow, that's an exciting idea and I can’t wait to see how it turns out!"

In general your proposal should include the following sections:

I. Introduction

In the real world of higher education, a research proposal is most often written by scholars seeking grant funding for a research project or it's the first step in getting approval to write a doctoral dissertation. Even if this is just a course assignment, treat your introduction as the initial pitch of an idea or a thorough examination of the significance of a research problem. After reading the introduction, your readers should not only have an understanding of what you want to do, but they should also be able to gain a sense of your passion for the topic and be excited about the study's possible outcomes. Note that most proposals do not include an abstract [summary] before the introduction.

Think about your introduction as a narrative written in one to three paragraphs that succinctly answers the following four questions :

- What is the central research problem?

- What is the topic of study related to that problem?

- What methods should be used to analyze the research problem?

- Why is this important research, what is its significance, and why should someone reading the proposal care about the outcomes of the proposed study?

II. Background and Significance

This section can be melded into your introduction or you can create a separate section to help with the organization and narrative flow of your proposal. This is where you explain the context of your proposal and describe in detail why it's important. Approach writing this section with the thought that you can’t assume your readers will know as much about the research problem as you do. Note that this section is not an essay going over everything you have learned about the topic; instead, you must choose what is relevant to help explain the goals for your study.

To that end, while there are no hard and fast rules, you should attempt to address some or all of the following key points:

- State the research problem and give a more detailed explanation about the purpose of the study than what you stated in the introduction. This is particularly important if the problem is complex or multifaceted .

- Present the rationale of your proposed study and clearly indicate why it is worth doing. Answer the "So What? question [i.e., why should anyone care].

- Describe the major issues or problems to be addressed by your research. Be sure to note how your proposed study builds on previous assumptions about the research problem.

- Explain how you plan to go about conducting your research. Clearly identify the key sources you intend to use and explain how they will contribute to your analysis of the topic.

- Set the boundaries of your proposed research in order to provide a clear focus. Where appropriate, state not only what you will study, but what is excluded from the study.

- If necessary, provide definitions of key concepts or terms.

III. Literature Review

Connected to the background and significance of your study is a section of your proposal devoted to a more deliberate review and synthesis of prior studies related to the research problem under investigation . The purpose here is to place your project within the larger whole of what is currently being explored, while demonstrating to your readers that your work is original and innovative. Think about what questions other researchers have asked, what methods they have used, and what is your understanding of their findings and, where stated, their recommendations. Do not be afraid to challenge the conclusions of prior research. Assess what you believe is missing and state how previous research has failed to adequately examine the issue that your study addresses. For more information on writing literature reviews, GO HERE .

Since a literature review is information dense, it is crucial that this section is intelligently structured to enable a reader to grasp the key arguments underpinning your study in relation to that of other researchers. A good strategy is to break the literature into "conceptual categories" [themes] rather than systematically describing groups of materials one at a time. Note that conceptual categories generally reveal themselves after you have read most of the pertinent literature on your topic so adding new categories is an on-going process of discovery as you read more studies. How do you know you've covered the key conceptual categories underlying the research literature? Generally, you can have confidence that all of the significant conceptual categories have been identified if you start to see repetition in the conclusions or recommendations that are being made.

To help frame your proposal's literature review, here are the "five C’s" of writing a literature review:

- Cite , so as to keep the primary focus on the literature pertinent to your research problem.

- Compare the various arguments, theories, methodologies, and findings expressed in the literature: what do the authors agree on? Who applies similar approaches to analyzing the research problem?

- Contrast the various arguments, themes, methodologies, approaches, and controversies expressed in the literature: what are the major areas of disagreement, controversy, or debate?

- Critique the literature: Which arguments are more persuasive, and why? Which approaches, findings, methodologies seem most reliable, valid, or appropriate, and why? Pay attention to the verbs you use to describe what an author says/does [e.g., asserts, demonstrates, argues, etc.] .

- Connect the literature to your own area of research and investigation: how does your own work draw upon, depart from, synthesize, or add a new perspective to what has been said in the literature?

IV. Research Design and Methods

This section must be well-written and logically organized because you are not actually doing the research, yet, your reader must have confidence that it is worth pursuing . The reader will never have a study outcome from which to evaluate whether your methodological choices were the correct ones. Thus, the objective here is to convince the reader that your overall research design and methods of analysis will correctly address the problem and that the methods will provide the means to effectively interpret the potential results. Your design and methods should be unmistakably tied to the specific aims of your study.

Describe the overall research design by building upon and drawing examples from your review of the literature. Consider not only methods that other researchers have used but methods of data gathering that have not been used but perhaps could be. Be specific about the methodological approaches you plan to undertake to obtain information, the techniques you would use to analyze the data, and the tests of external validity to which you commit yourself [i.e., the trustworthiness by which you can generalize from your study to other people, places, events, and/or periods of time].

When describing the methods you will use, be sure to cover the following:

- Specify the research operations you will undertake and the way you will interpret the results of these operations in relation to the research problem. Don't just describe what you intend to achieve from applying the methods you choose, but state how you will spend your time while applying these methods [e.g., coding text from interviews to find statements about the need to change school curriculum; running a regression to determine if there is a relationship between campaign advertising on social media sites and election outcomes in Europe ].

- Keep in mind that a methodology is not just a list of tasks; it is an argument as to why these tasks add up to the best way to investigate the research problem. This is an important point because the mere listing of tasks to be performed does not demonstrate that, collectively, they effectively address the research problem. Be sure you explain this.

- Anticipate and acknowledge any potential barriers and pitfalls in carrying out your research design and explain how you plan to address them. No method is perfect so you need to describe where you believe challenges may exist in obtaining data or accessing information. It's always better to acknowledge this than to have it brought up by your reader.

Develop a Research Proposal: Writing the Proposal . Office of Library Information Services. Baltimore County Public Schools; Heath, M. Teresa Pereira and Caroline Tynan. “Crafting a Research Proposal.” The Marketing Review 10 (Summer 2010): 147-168; Jones, Mark. “Writing a Research Proposal.” In MasterClass in Geography Education: Transforming Teaching and Learning . Graham Butt, editor. (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015), pp. 113-127; Juni, Muhamad Hanafiah. “Writing a Research Proposal.” International Journal of Public Health and Clinical Sciences 1 (September/October 2014): 229-240; Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005; Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal . The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Punch, Keith and Wayne McGowan. "Developing and Writing a Research Proposal." In From Postgraduate to Social Scientist: A Guide to Key Skills . Nigel Gilbert, ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2006), 59-81; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal . International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences, Articles, and Books . The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal . University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- << Previous: Purpose of Guide

- Next: Types of Research Designs >>

- Last Updated: Sep 8, 2023 12:19 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.txstate.edu/socialscienceresearch

The Library Is Open

The Wallace building is now open to the public. More information on services available.

- RIT Libraries

- Social/Behavioral Sciences Research Guide

- Writing a Research Proposal

This InfoGuide assists students starting their research proposal and literature review.

- Introduction

- Research Process

- Types of Research Methodology

- Data Collection Methods

- Anatomy of a Scholarly Article

- Finding a topic

- Identifying a Research Problem

- Problem Statement

- Research Question

- Research Design

- Search Strategies

- Psychology Database Limiters

- Literature Review Search

- Annotated Bibliography

- Writing a Literature Review

Writing a Rsearch Proposal

A research proposal describes what you will investigate, why it’s important, and how you will conduct your research. Your paper should include the topic, research question and hypothesis, methods, predictions, and results (if not actual, then projected).

Research Proposal Aims

The format of a research proposal varies between fields, but most proposals will contain at least these elements:

Literature review

- Research design

Reference list

While the sections may vary, the overall objective is always the same. A research proposal serves as a blueprint and guide for your research plan, helping you get organized and feel confident in the path forward you choose to take.

Proposal Format

The proposal will usually have a title page that includes:

- The proposed title of your project

- Your supervisor’s name

- Your institution and department

Introduction The first part of your proposal is the initial pitch for your project. Make sure it succinctly explains what you want to do and why.. Your introduction should:

- Introduce your topic

- Give necessary background and context

- Outline your problem statement and research questions To guide your introduction , include information about:

- Who could have an interest in the topic (e.g., scientists, policymakers)

- How much is already known about the topic

- What is missing from this current knowledge

- What new insights will your research contribute

- Why you believe this research is worth doing

As you get started, it’s important to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the most important research on your topic. A strong literature review shows your reader that your project has a solid foundation in existing knowledge or theory. It also shows that you’re not simply repeating what other people have done or said, but rather using existing research as a jumping-off point for your own.

In this section, share exactly how your project will contribute to ongoing conversations in the field by:

- Comparing and contrasting the main theories, methods, and debates

- Examining the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches

- Explaining how will you build on, challenge, or synthesize prior scholarship

Research design and methods

Following the literature review, restate your main objectives . This brings the focus back to your project. Next, your research design or methodology section will describe your overall approach, and the practical steps you will take to answer your research questions. Write up your projected, if not actual, results.

Contribution to knowledge

To finish your proposal on a strong note, explore the potential implications of your research for your field. Emphasize again what you aim to contribute and why it matters.

For example, your results might have implications for:

- Improving best practices

- Informing policymaking decisions

- Strengthening a theory or model

- Challenging popular or scientific beliefs

- Creating a basis for future research

Lastly, your research proposal must include correct citations for every source you have used, compiled in a reference list . To create citations quickly and easily, you can use free APA citation generators like BibGuru. Databases have a citation button you can click on to see your citation. Sometimes you have to re-format it as the citations may have mistakes.

- << Previous: Writing a Literature Review

Edit this Guide

Log into Dashboard

Use of RIT resources is reserved for current RIT students, faculty and staff for academic and teaching purposes only. Please contact your librarian with any questions.

Help is Available

Email a Librarian

A librarian is available by e-mail at [email protected]

Meet with a Librarian

Call reference desk voicemail.

A librarian is available by phone at (585) 475-2563 or on Skype at llll

Or, call (585) 475-2563 to leave a voicemail with the reference desk during normal business hours .

Chat with a Librarian

Social/behavioral sciences research guide infoguide url.

https://infoguides.rit.edu/researchguide

Use the box below to email yourself a link to this guide

School of Social Sciences

How to write a research proposal

You will need to submit a research proposal with your PhD application. This is crucial in the assessment of your application and it warrants plenty of time and energy.

Your proposal should outline your project and be around 1,500 words.

Your research proposal should include a working title for your project.

Overview of the research

In this section, you should provide a short overview of your research. You should also state how your research fits into the research priorities of your particular subject area.

Here you can refer to the research areas and priorities of a particular research grouping or supervisor.

You must also state precisely why you have chosen to apply to the discipline area and how your research links into our overall profile.

Positioning of the research

This should reference the most important texts related to the research, demonstrate your understanding of the research issues, and identify existing gaps (both theoretical and practical) that the research is intended to address.

Research design and methodology

This section should identify the information that is necessary to carry out the analysis and the possible research techniques that could deliver the information.

Ethical considerations

You should identify and address any potential ethical considerations in relation to your proposed research. Please discuss your research with your proposed supervisor to see how best to progress your ideas in line with University of Manchester ethics guidance, and ensure that your proposed supervisor is happy for you to proceed with your application.

Your research proposal will be used to assess the quality and originality of your ideas, whether you are able to think critically and whether you have a grasp of the relevant literature. It also gives us important information about the perspectives you intend to take on your research area, and how you fit into the department's research profile overall. This is helpful when assigning a supervisor.

If you are applying to study an Economics postgraduate research programme, our advice and requirements are slightly different:

- How to write an economics proposal

Supervisors

We encourage you to discuss your proposal informally with a potential supervisor before making a formal application to ensure it is of mutual interest.

Please note that we cannot guarantee that we will be able to allocate you to the supervisor you initially contact and that we may allocate you to another expert in the area.

- Find a supervisor

Flexibility

You will not be forced to follow the proposal exactly once you have started to study. It is normal for students to refine their original proposal, in light of detailed literature review, further consideration of research approaches and comments received from your supervisors (and other academic staff).

Pitfalls to avoid

We sometimes have to reject students who meet the academic requirements but have not produced a satisfactory research proposal, therefore:

- Make sure that your research idea, question or problem is very clearly stated and well-grounded in academic research.

- Make sure that your proposal is well focused and conforms exactly to the submission requirements described here.

- Poorly specified, jargon-filled or rambling proposals will not convince us that you have a clear idea of what you want to do.

The University uses electronic systems to detect plagiarism and other forms of academic malpractice and for assessment. All Humanities PhD programmes require the submission of a research proposal as part of the application process. The Doctoral Academy upholds the principle that where a candidate approaches the University with a project of study, this should be original. While it is understandable that research may arise out of previous studies, it is vital that your research proposal is not the subject of plagiarism.

Example proposals

- Philosophy - Example 1

- Philosophy - Example 2

- Politics - Example 1

- Politics - Example 2

- Social Anthropology - Example 1

- Social Anthropology - Example 2

- Social Statistics - Example 1

- Social Statistics - Example 2

- Sociology - Example 1

- Sociology - Example 2

Further help

The following books may help you to prepare your research proposal (as well as in doing your research degree).

- Bell, J. (1999): Doing Your Research Project: A Guide for First-time Researchers in Education & Social Science , (Oxford University Press, Oxford).

- Baxter, L, Hughes, C. and Tight, M. (2001): How to Research , (Open University Press, Milton Keynes).

- Cryer, P. (2000): The Research Student's Guide to Success , (Open University, Milton Keynes).

- Delamont, S., Atkinson, P. and Parry, O. (1997): Supervising the PhD , (Open University Press, Milton Keynes).

- Philips, E. and Pugh, D. (2005): How to get a PhD: A Handbook for Students and their Supervisors , (Open University Press, Milton Keynes).

If you need help and advice about your application, contact the Postgraduate Admissions Team.

Admissions contacts

University guidelines

You may also find it useful to read the advice and guidance on the University website about writing a proposal for your research degree application.

Visit the University website

Research Proposal Example/Sample

Detailed Walkthrough + Free Proposal Template

If you’re getting started crafting your research proposal and are looking for a few examples of research proposals , you’ve come to the right place.

In this video, we walk you through two successful (approved) research proposals , one for a Master’s-level project, and one for a PhD-level dissertation. We also start off by unpacking our free research proposal template and discussing the four core sections of a research proposal, so that you have a clear understanding of the basics before diving into the actual proposals.

- Research proposal example/sample – Master’s-level (PDF/Word)

- Research proposal example/sample – PhD-level (PDF/Word)

- Proposal template (Fully editable)

If you’re working on a research proposal for a dissertation or thesis, you may also find the following useful:

- Research Proposal Bootcamp : Learn how to write a research proposal as efficiently and effectively as possible

- 1:1 Proposal Coaching : Get hands-on help with your research proposal

PS – If you’re working on a dissertation, be sure to also check out our collection of dissertation and thesis examples here .

FAQ: Research Proposal Example

Research proposal example: frequently asked questions, are the sample proposals real.

Yes. The proposals are real and were approved by the respective universities.

Can I copy one of these proposals for my own research?

As we discuss in the video, every research proposal will be slightly different, depending on the university’s unique requirements, as well as the nature of the research itself. Therefore, you’ll need to tailor your research proposal to suit your specific context.

You can learn more about the basics of writing a research proposal here .

How do I get the research proposal template?

You can access our free proposal template here .

Is the proposal template really free?

Yes. There is no cost for the proposal template and you are free to use it as a foundation for your research proposal.

Where can I learn more about proposal writing?

For self-directed learners, our Research Proposal Bootcamp is a great starting point.

For students that want hands-on guidance, our private coaching service is recommended.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Research Proposal Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

10 Comments

I am at the stage of writing my thesis proposal for a PhD in Management at Altantic International University. I checked on the coaching services, but it indicates that it’s not available in my area. I am in South Sudan. My proposed topic is: “Leadership Behavior in Local Government Governance Ecosystem and Service Delivery Effectiveness in Post Conflict Districts of Northern Uganda”. I will appreciate your guidance and support

GRADCOCH is very grateful motivated and helpful for all students etc. it is very accorporated and provide easy access way strongly agree from GRADCOCH.

Proposal research departemet management

I am at the stage of writing my thesis proposal for a masters in Analysis of w heat commercialisation by small holders householdrs at Hawassa International University. I will appreciate your guidance and support

please provide a attractive proposal about foreign universities .It would be your highness.

comparative constitutional law

Kindly guide me through writing a good proposal on the thesis topic; Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Financial Inclusion in Nigeria. Thank you

Kindly help me write a research proposal on the topic of impacts of artisanal gold panning on the environment

I am in the process of research proposal for my Master of Art with a topic : “factors influence on first-year students’s academic adjustment”. I am absorbing in GRADCOACH and interested in such proposal sample. However, it is great for me to learn and seeking for more new updated proposal framework from GRADCAOCH.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

17 Research Proposal Examples

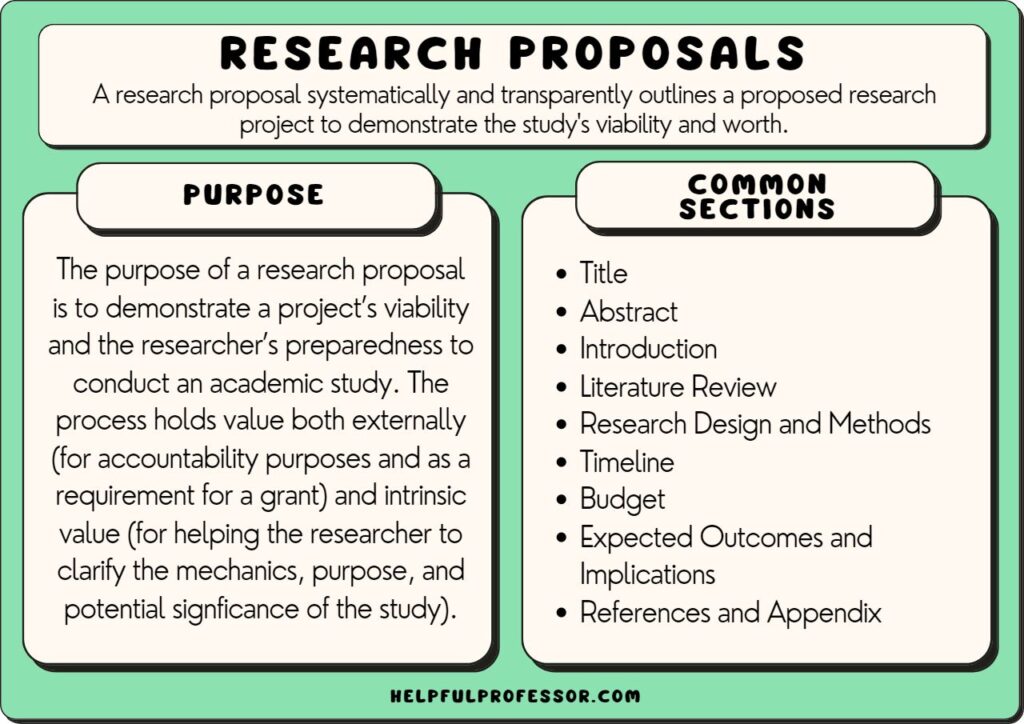

A research proposal systematically and transparently outlines a proposed research project.

The purpose of a research proposal is to demonstrate a project’s viability and the researcher’s preparedness to conduct an academic study. It serves as a roadmap for the researcher.

The process holds value both externally (for accountability purposes and often as a requirement for a grant application) and intrinsic value (for helping the researcher to clarify the mechanics, purpose, and potential signficance of the study).

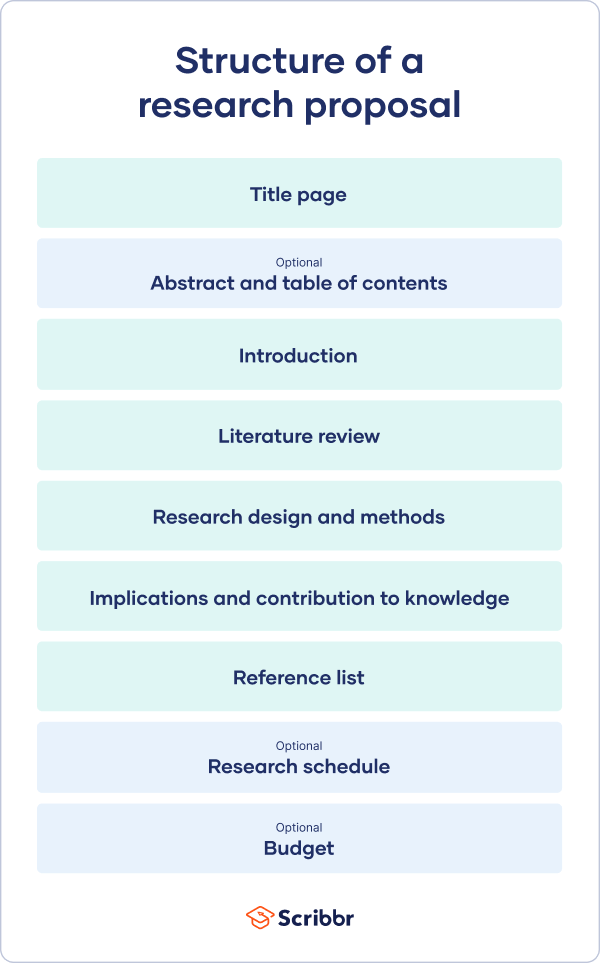

Key sections of a research proposal include: the title, abstract, introduction, literature review, research design and methods, timeline, budget, outcomes and implications, references, and appendix. Each is briefly explained below.

Watch my Guide: How to Write a Research Proposal

Get your Template for Writing your Research Proposal Here (With AI Prompts!)

Research Proposal Sample Structure

Title: The title should present a concise and descriptive statement that clearly conveys the core idea of the research projects. Make it as specific as possible. The reader should immediately be able to grasp the core idea of the intended research project. Often, the title is left too vague and does not help give an understanding of what exactly the study looks at.

Abstract: Abstracts are usually around 250-300 words and provide an overview of what is to follow – including the research problem , objectives, methods, expected outcomes, and significance of the study. Use it as a roadmap and ensure that, if the abstract is the only thing someone reads, they’ll get a good fly-by of what will be discussed in the peice.