Locus of Control Theory In Psychology: Definition & Examples

Gabriel Lopez-Garrido

Undergraduate at Harvard University

Political Science and Psychology

Gabriel Lopez-Garrido is currently in his final year at Harvard University. He is pursuing a Bachelor's degree with a primary focus on Political Science (Government) and a minor in Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

Take-home Messages

- The term ‘Locus of control’ refers to how much control a person feels they have in their own behavior. A person can either have an internal or external locus of control (Rotter, 1954).

- People with a high internal locus of control perceive themselves as having much personal control over their behavior and are, therefore, more likely to take responsibility for their behavior. For example, I did well on the exams because I revised extremely hard.

- In contrast, a person with a high external locus of control perceives their behaviors as a result of external influences or luck – e.g., I did well on the test because it was easy.

- Research has shown that people with an internal locus of control tend to be less conforming and obedient (i.e., more independent). Rotter proposes that people with an internal locus of control are better at resisting social pressure to conform or obey, perhaps because they feel responsible for their actions.

- Locus of control is an important term to know in almost every branch of the psychology community. This is mainly because it can be applied in many aspects of daily life; whether the locus is external or internal, it will – by definition – affect your mind, body, and even actions.

- Fields like educational psychology, clinical psychology, and even health psychology have all made strides in researching the phenomenon to understand more about how one can control or improve one’s locus of control.

- Experts in the field of psychology often disagree with each other regarding whether differences should be attributed based on cultural differences or whether a more worldwide measure of locus of control will be more helpful when it comes to practical application.

Internal vs. External Locus of Control

Locus of control is how much individuals perceive that they themselves have control over their own actions as opposed to events in life occurring instead because of external forces. It is measured along a dimension of “high internal” to “high external”.

The concept was created by Julian B. Rotter in 1954, and it quickly became a central concept in the field of personality psychology.

An individual’s “locus” (plural “loci”) is conceptualized as internal (a conviction that one can handle one’s own life) or external (a conviction that life is constrained by outside factors which the individual can’t impact or that possibility or destiny controls their lives). There is a continuum, with most people lying in between.

A high internal perceive themselves as having a great deal of personal control and therefore are more inclined to take personal responsibility for their behavior, which they see are being a product of their own effect. High external perceive their behavior as being caused more by external forces or luck.

It is also worth mentioning that the term locus of control is not to be confused with attributional style . Locus of control refers to an idea connected with anticipations about the future, while attributional style is a concept that is instead concerned with finding explanations for past outcomes.

People with an internal locus of control accept occasions in their day-to-day existence as controllable. To be more specific, this means that they can recognize instances where destiny is controllable: for instance, an individual is taking a test for a driver’s license.

A person with an internal locus of control will attribute whether they pass or fail the exam due to their own capabilities. This individual would praise their own abilities if they passed the test and would also recognize the need to improve their own driving if they had instead failed the exam.

An individual with an external locus of control would perceive the same event differently. This individual would be more likely to blame other factors such as the weather, their current condition, or even the exam itself as an excuse rather than accept that the exam went the way it did because of personal decisions.

Rather than accept that part of the blame rests on them, the event is instead attributed to occur because of uncontrollable forces (destiny/fate/etc.).

Locus of control is one of the four elements of center self-assessments – one’s principal examination of oneself – alongside neuroticism , self-viability, and self-esteem.

The idea of center self-assessments was first inspected by Judge, Locke, and Durham (1997), and since has demonstrated to foresee a few work results, explicitly, work fulfillment and occupation performance.

In a subsequent report, Judge et al. (2002) contended that locus of control, neuroticism, self-viability, and confidence elements might all influence each other.

How it Works

The first recorded trace of the term Locus of Control comes from Julian B. Rotter’s work (1954) based on the social learning theory of personality. It is a great example of a generalized expectancy related to problem-solving, a strategy that applies to a wide variety of situations.

In 1966 Rotter distributed an article in Psychological Monographs that summed up around a decade of extensive research (by Rotter and his understudies), with most of this work actually never being published beforehand.

It is speculated that Locus of Control may have come beforehand as a term coined by a psychologist by the name of Alfred Adler . The evidence for this is lacking, however, so the main bulk of the credit for the concept lies in Rotter and his understudies” early works.

One of these understudies was William H. James. This psychologist would later go on to produce his own work in the field, but while he was under the tutelage of Rotter, he wanted to study what he denoted as “expectancy shifts.”

These “expectancy shifts” can be classified as follows:

Typical Expectancy Shifts

Typical expectancy shifts derive from the belief that success (or failure) will be the determining notion for whatever activity/action is preceded next (that is to say, if one succeeds at something, then the expectancy is that they will succeed again).

Let’s say – for example – that during a basketball game, a player shoots a basketball and scores a point. After attempting this three times and scoring all three, the player might come to believe that (due to the fact the player has been continuously successful) if they continue to shoot, they will continue to score.

Atypical Expectancy Shifts

Atypical expectancy shifts, which derive from the belief that success (or a failure) will not have any determining notion for whichever activity/action that follows it (that is to say, if one succeeds at an activity, then the expectancy for the subsequent one is independent of this result; one could fail or succeed).

To give an example of this, picture someone who is at a casino. This individual places a bet on the ball, landing on a red number in the roulette wheel.

After three spins of the wheel, the ball has landed once in a red number, once in a black number, and finally once in a green number. The individual will (hopefully) most likely come to the conclusion that the result of the spin is independent of the last result, with each individual spin being a stand-alone event.

Additional research supported the hypothesis that typical expectancy shifts were much more common amongst individuals who had confidence in their own abilities, whilst those who didn’t really believe in their capabilities tended to attribute their expectancies toward fate rather than skill.

In other words, the distinction lies in whether the cause is internal or external; those who have faith in their own abilities will look towards an internal cause and adapt a typical expectancy shift, while those who attribute their results to external causes will most likely exhibit an atypical expectancy shift.

Rotter has made strides in this area of his research, covering this phenomenon in multiple works (1975). He has talked about issues and confusion in others’ utilization of the interior versus outer build, explaining how misconceptions and miscommunication have led people to mistake Locus of Control for other psychological terms.

Measurement

There are multiple ways to measure locus of control, but by far, the most widely used questionnaire is the 13-item (plus six filler items) forced-choice scale of Rotter (1966). This questionnaire first came into the scene in 1966 and is arguably still the best way to determine the locus of control in the present day. This does not mean that this is the only popular questionnaire.

Another example is Bialer’s (1961) 23-item scale for children, which actually even predates Rotter’s work. Other examples would be the Crandall Intellectual Ascription of Responsibility Scale (Crandall, 1965) and the Nowicki-Strickland Scale (Nowicki & Strickland, 1973), though again, most of these are not used in favor of Rotter’s 1966 questionnaire.

One of his understudies (again, William H. James) was actually responsible for developing one of the earliest psychometric scales to assess locus of control for his unpublished doctoral dissertation, supervised by Rotter at Ohio State University. As just mentioned, however, the work remains unpublished yet it is an example of just how much influence Rotter and his students have over the origins of the term.

Many measures of locus of control have appeared since Rotter’s scale. These vary from the original that predate Rotter’s own original designs to the locus of controls designed specifically for groups – like children (such as the Stanford Preschool Internal-External Scale for three- to six-year-olds).

According to the data analyzed by Furnham and Steele (1993), they suggest that the most reliable, valid questionnaire for adults is The Duttweiler (1984) Internal Control Index (ICI), which might be the better scale. Right off the bat, an advantage these scales have is that they address perceived problems with the Rotter scales.

These issues include adjusting the forced-choice format, removing the susceptibility to social desirability and heterogeneity (as indicated by factor analysis), and the natural improvements that come from developing something almost 30 years after the Rotter scales.

One important thing to note is that while other scales existed in 1984 besides the Duttweiler scales to measure locus of control, they all appear to fall victim to the same problems that the Rotter scales never originally addressed.

The primary difference lies in the removal of the forced-choice format used in Rotter’s scale. Previously, individuals had to affirm whether the assertion presented by the scale was true or false.

However, with Duttweiler’s 28-item ICI, which utilizes a Likert-type scale, individuals must specify whether they would behave as described in each of the 28 statements rarely, occasionally, sometimes, frequently, or usually.

This approach makes the scale much more adaptable to human nature’s nuances than the original Rotter scales.

The ICI gives individuals much more choice by assessing variables pertinent to internal locus. These include but are not limited to cognitive processing, resistance to social influence, self-reliance, autonomy, and delay of gratification. Small validation studies have indicated that the scale had good internal consistency reliability (a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85)

Applications

The field most associated with locus of control is health psychology, mainly because the original scales to measure locus of control originated in the health domain of psychology.

These first scales were originally reviewed and approved by Furnham and Steele in 1993; they have since remained an essential part of health and other branches of psychology.

Out of the reviewed scales, The best-known in the field of health psychology are the Health Locus of Control Scale and the Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Scale, or MHLC (Wallston & Wallston, 2004).

The idea that health psychology and Locus of control go together is based on the concept that health may be attributed to three sources: internal factors (such as self-determination of a healthy lifestyle), powerful external factors (the words of a doctor or a loved one) or luck/destiny/coincidence.

Those that belong to the last group are almost impossible to deal with, given that they have a firm belief that nothing they will do can either change or avert what is going to happen either way.

The scales reviewed by Furnham and Steele (1993) have directly contributed to multiple areas of health psychology. Take, for example, Saltzer’s (1982) Weight Locus of Control Scale or Stotland and Zuroff’s (1990) Dieting Beliefs Scale.

Both these scales tackled the issue of obesity and shed light on how it affects different types of individuals. These scales do not limit themselves only to the physical aspects of individuals; take, for example, Wood and Letak’s (1982) Mental health locus of control scale.

These scales try to measure the stages of health and depression that an individual is currently in; there’s even a scale meant for measuring cancer and cancer-like symptoms (the Cancer Locus of Control Scale of Pruyn et al., 1990).

Perhaps the most important link that locus of control has to health psychology is Claire Bradley’s work, which links locus of control to the management of diabetes mellitus. This empirical data was reviewed by Norman and Bennet (1997) and they note that the data collected on whether certain health-related behaviors are related to internal health locus of control is, at best ambiguous.

For example, they point out that according to certain studies, locus of control was found to be linked with increased exercise, but also note how other studies have mentioned that the impact that exercise has on locus of control is either minimal or non-existent.

Activities such as jogging or running have long since been dismissed as lone factors for influencing any sort of command in one’s locus of control.

This ambiguity goes on in the study, with data on the relationship between internal health locus of control and other health-related behaviors also being suspicious.

These health-related behaviors include breast self-examination, weight control, and preventive-health behavior and in the study, it is said that alcohol consumption has a direct relationship with one’s internal locus of control.

Again with alcoholism as a factor, the same problems occur; the facts from the study begin to contradict themselves. During their analysis of the validity of the study, Norman and Bennett (1998) realized that some of the studies concluded by suggesting that a link existed between alcoholism and having an increased externality for health locus of control.

This goes against what is known right now, which is that – according to multiple other studies – alcoholism is related instead to increased internality in regards to an individual’s locus of control. The perceived notion is that alcoholism is directly related to the strength of the locus, not to what type of locus exists.

That is to say, it does not matter whether an individual has an internal or external locus of control; alcohol consumption is only related to the actual strength of that respective locus of control.

What is internal locus of control?

An internal locus of control refers to the belief that one can control their own life and the outcomes of events. Individuals with a high internal locus of control perceive their actions as directly influencing the results they experience.

What is external locus of control?

An external locus of control refers to the belief that external factors, such as fate, luck, or other people, are responsible for the outcomes of events in one’s life rather than one’s own actions.

Who proposed the locus of control concept?

The concept of locus of control was proposed by psychologist Julian B. Rotter in 1954.

Bennett, P., Norman, P., Murphy, S., Moore, L., & Tudor-Smith, C. (1998). Beliefs about alcohol, health locus of control, value for health and reported consumption in a representative population sample. Health Education Research, 13 (1), 25-32.

Bialer, I. (1961). Conceptualization of success and failure in mentally retarded and normal children. Journal of personality .

CRANDALL, V. C., KATKOVSKY, W., & CRANDALL, V. J. (1965) Children’s beliefs in their own control of reinforcements in intellectual-academic achievement situations. Child Development , 36, 91-109.

Duttweiler, P. C. (1984). The internal control index: A newly developed measure of locus of control. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 44 (2), 209-221.

Furnham, A., & Steele, H. (1993). Measuring locus of control: A critique of general, children’s, health‐and work‐related locus of control questionnaires. British Journal of Psychology, 84 (4), 443-479.

Nowicki, S., & Strickland, B. R. (1973). A locus of control scale for children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 40 (1), 148.

Norman, P., Bennett, P., Smith, C., & Murphy, S. (1997). Health locus of control and leisure-time exercise. Personality and Individual Differences, 23 (5), 769-774.

Norman, P., Bennett, P., Smith, C., & Murphy, S. (1998). Health locus of control and health behavior. Journal of Health Psychology, 3 (2), 171-180.

Rotter, J. B. (1954). Social learning and clinical psychology .

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological monographs: General and applied, 80 (1), 1.

Rotter, J. B. (1975). Some problems and misconceptions related to the construct of internal versus external control of reinforcement. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 43 (1), 56.

Saltzer, E. B. (1982). The weight locus of control (WLOC) scale: a specific measure for obesity research. Journal of Personality Assessment, 46 (6), 620-628.

Stotland, S., & Zuroff, D. C. (1990). A new measure of weight locus of control: The Dieting Beliefs Scale. Journal of personality assessment, 54 (1-2), 191-203.

Wallston, K. A., Strudler Wallston, B., & DeVellis, R. (1978). Development of the multidimensional health locus of control (MHLC) scales. Health education monographs, 6 (1), 160-170.

Wallston, K. A., & Wallston, B. S. (2004). Multidimensional health locus of control scale. Encyclopedia of health psychology , 171, 172.

Watson, M., Greer, S., Pruyn, J., & Van Den Borne, B. (1990). Locus of control and adjustment to cancer. Psychological Reports, 66 (1), 39-48.

Wood, W. D., & Letak, J. K. (1982). A mental-health locus of control scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 3 (1), 84-87.

Keep Learning

- Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological monographs: General and applied, 80(1), 1.

- Rotter, J. B. (1990). Internal versus external control of reinforcement: A case history of a variable. American psychologist, 45(4), 489.

- Stotland, S., & Zuroff, D. C. (1990). A new measure of weight locus of control: The Dieting Beliefs Scale. Journal of personality assessment, 54(1-2), 191-203.

- Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior

Related Articles

Social Science

Hard Determinism: Philosophy & Examples (Does Free Will Exist?)

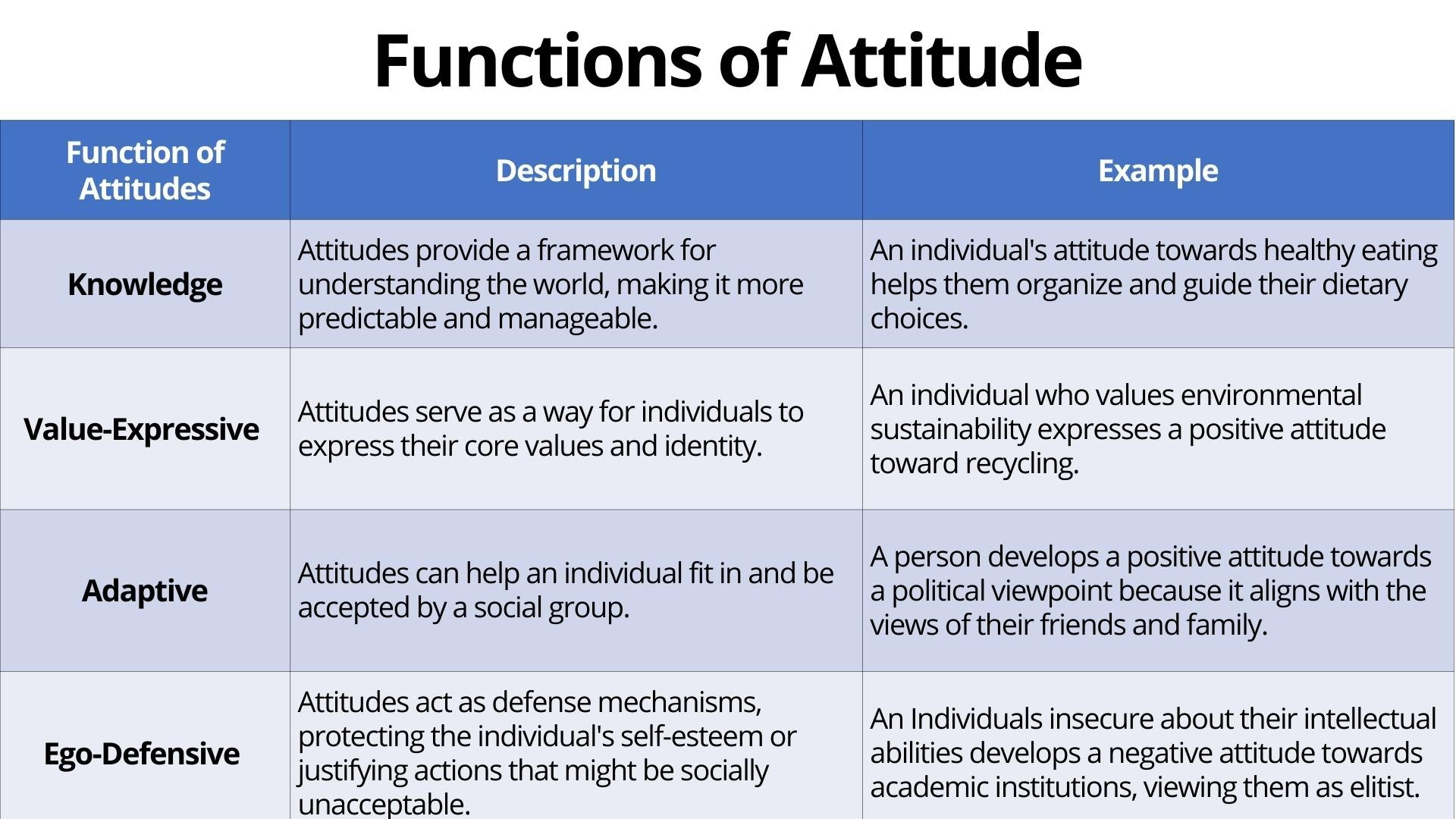

Functions of Attitude Theory

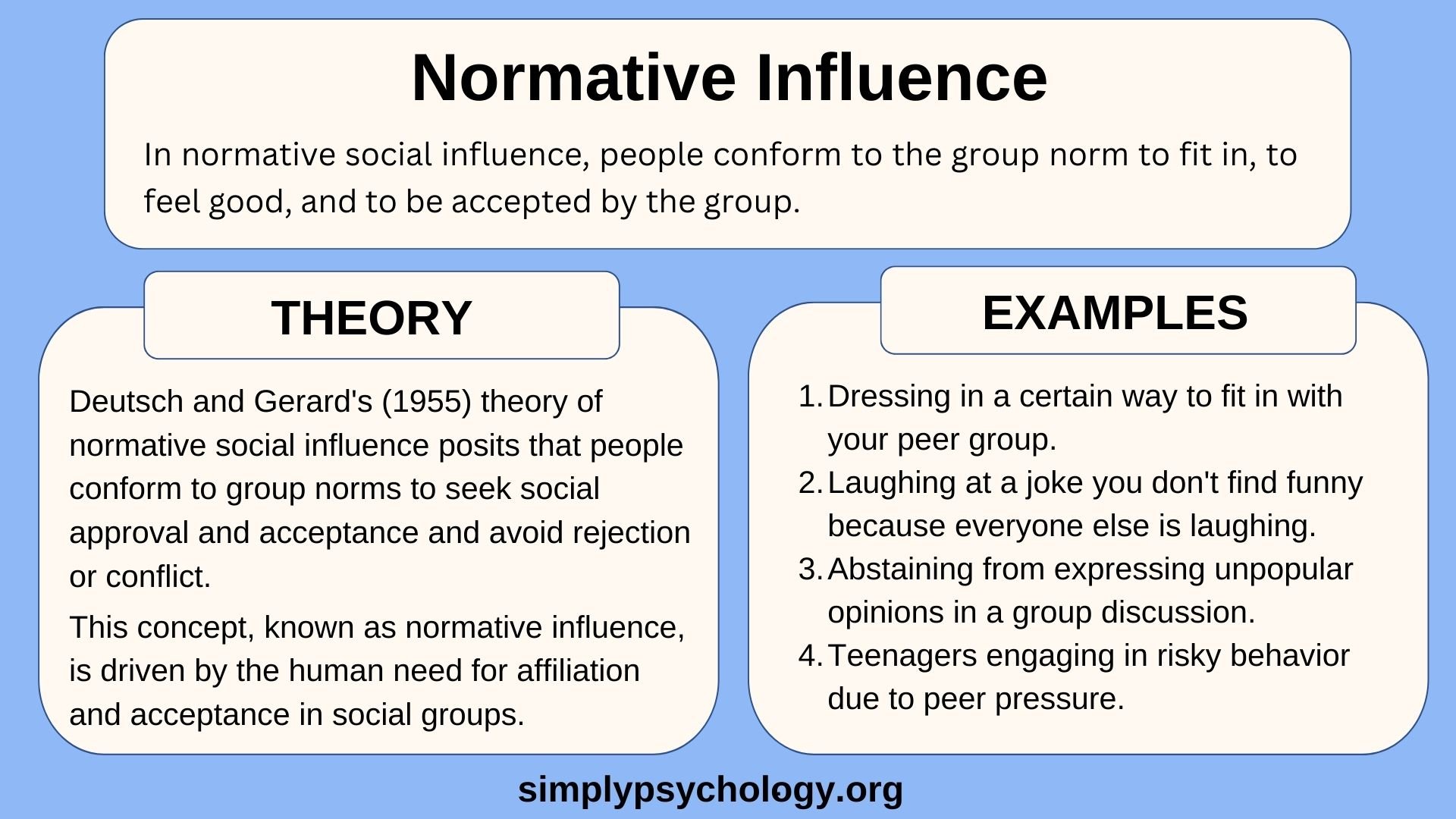

Understanding Conformity: Normative vs. Informational Social Influence

Social Control Theory of Crime

Emotions , Mood , Social Science

Emotional Labor: Definition, Examples, Types, and Consequences

Famous Experiments , Social Science

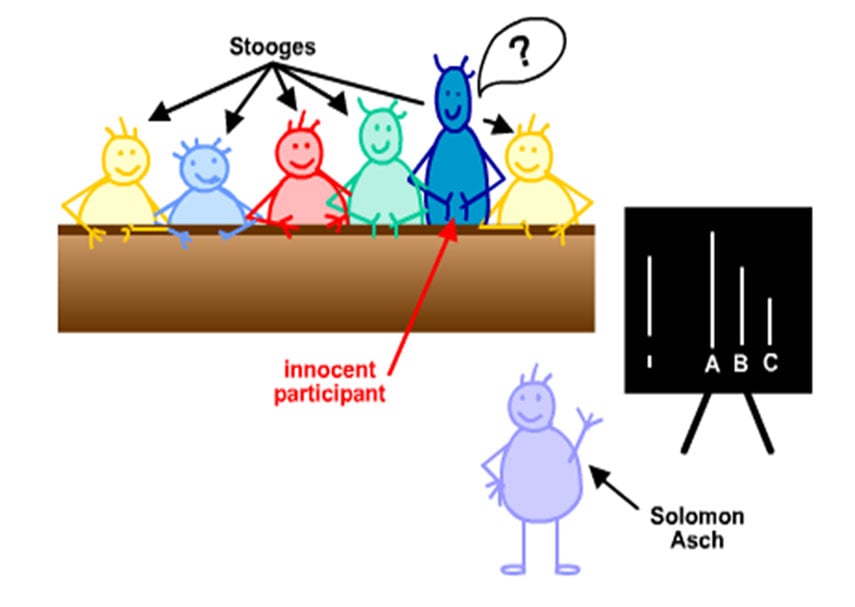

Solomon Asch Conformity Line Experiment Study

Locus of Control

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2022

- pp 2948–2952

- Cite this reference work entry

- Stephanie A. Robinson 3 &

- Margie E. Lachman 4

185 Accesses

Control beliefs ; Learned helplessness ; Perceived constraints ; Perceived control ; Primary and secondary control ; Sense of control ; Sense of mastery

Expectancies about the degree of influence one has on outcomes and events in their life (Rotter 1966 ). The locus of control is operationalized with self-assessments using items or statements that rate the degree one expects to be able to bring about desired outcomes or overcome external constraints in order to reach goals, in general or within specific domains and situations (Lachman et al. 2015 ).

The locus of control was first conceptualized by Julian Rotter ( 1966 ) in his social learning theory, where he described the locus of control as either internal (e.g., abilities, effort) or external (e.g., chance, fate, powerful others). While this line of work was prolific, there were limitations with its initial distinction between internal and external control. Internal and external control were described as two...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Almeida DM (2005) Resilience and vulnerability to daily stressors assessed via diary methods. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 14:64–68

Google Scholar

Baltes MM (1995) Dependency in old age: gains and losses. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 4:14–19

Bandura A (1977) Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev 84:191–215

Bandura A (1986) The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. J Soc Clin Psychol 4:359–373

Bierut LJ, Johnson EO, Saccone NL (2014) A glimpse into the future – personalized medicine for smoking cessation. Neuropharmacology 76(Pt B):592–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.09.009

Article Google Scholar

Bollini AM, Walker EF, Hamann S, Kestler L (2004) The influence of perceived control and locus of control on the cortisol and subjective responses to stress. Biol Psychol 67:245–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2003.11.002

Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC (eds) (2004) How healthy are we?: a national study of well-being at midlife. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Chipperfield JG, Hamm JM, Perry RP, Ruthig JC (2017) Perspectives on studying perceived control in the twenty-first century. In: The happy mind: cognitive contributions to well-being. Springer, Cham, pp 215–233

Eizenman DR, Nesselroade JR, Featherman DL, Rowe JW (1997) Intraindividual variability in perceived control in a older sample: the MacArthur successful aging studies. Psychol Aging 12:489

Heckhausen J, Wrosch C, Schulz R (2010) A motivational theory of life-span development. Psychol Rev 117(32). https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017668

Infurna FJ, Gerstorf D (2013) Linking perceived control, physical activity, and biological health to memory change. Psychol Aging 28:1147–1163. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033327

Infurna FJ, Luthar SS (2016) Resilience to major life stressors is not as common as thought. Perspect Psychol Sci 11:175–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615621271

Juster FT, Suzman R (1995) An overview of the health and retirement study. J Hum Resour 30:S7–S56

Lachman ME (1986) Locus of control in aging research: a case for multidimensional and domain-specific assessment. Psychol Aging 1:34–40. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.1.1.34

Lachman ME (2006) Perceived control over aging-related declines: adaptive beliefs and behaviors. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 15:282–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00453.x

Lachman ME, Andreoletti C (2006) Strategy use mediates the relationship between control beliefs and memory performance for middle-aged and older adults. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 61:P88–P94. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/61.2.P88

Lachman ME, Firth KM (2004) The adaptive value of feeling in control during midlife. In: Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC (eds) How healthy are we?: a national study of well-being in midlife. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 320–349

Lachman ME, Weaver SL (1998a) The sense of control as a moderator of social class differences in health and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 74:763–773

Lachman ME, Weaver SL (1998b) Sociodemographic variations in the sense of control by domain: findings from the MacArthur studies of midlife. Psychol Aging 13:553

Lachman ME, Rocke C, Rosnick C, Ryff CD (2008) Realism and illusion in Americans ’ temporal views of their life satisfaction the future. Psychol Sci 19:889–897. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02173.x

Lachman ME, Rosnick CB, Röcke C (2009) The rise and fall of control beliefs in adulthood: cognitive and biopsychosocial antecedents and consequences of stability and change over 9 years. In: Aging and cognition: research methodologies and empirical advances, pp 143–160. https://doi.org/10.1037/11882-007

Chapter Google Scholar

Lachman ME, Neupert SD, Agrigoroaei S (2011) The relevance of control beliefs for health and aging. In: Schaie KW, Willis SL (eds) Handbook of the psychology of aging, 7th edn. Elsevier, pp 175–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-380882-0.00011-5

Lachman ME, Agrigoroaei S, Rickenbach EH (2015) Making sense of control: change and consequences. In: Scott RA, Kosslyn SM (eds) Emerging trends in the social and behavioral sciences: an interdisciplinary, searchable, and linkable resource. Wiley, Hoboken, pp 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118900772.etrds0209

Langer EJ, Rodin J (1976) The effects of choice and enhanced personal responsibility for the aged: a field experiment in an institutional setting. J Pers Soc Psychol 34:191–198. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.34.2.191

Mallers MH, Claver M, Lares LA (2013) Perceived control in the lives of older adults: the influence of Langer and Rodin’s work on gerontological theory, policy, and practice. The Gerontologist 54:67–74. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnt051

Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, Walter T (2009) Internet-based personalized feedback to reduce 21st-birthday drinking: a randomized controlled trial of an event-specific prevention intervention. J Consult Clin Psychol 77:51–63. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014386

Neupert SD, Almeida DM, Charles ST (2007) Age differences in reactivity to daily stressors: the role of personal control. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 62:P216–P225. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/62.4.P216

Robinson S, Lachman M (2016) Perceived control and behavior change: a personalized approach. In: Perceived control: theory, research, and practice in the first 50 years. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 201–227

Robinson SA, Lachman ME (2018a) Daily control beliefs and cognition: the mediating role of physical activity. J Gerontol: Series B. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby081

Robinson SA, Lachman ME (2018b) Perceived control and cognition in adulthood: the mediating role of physical activity. Psychol Aging 33:769. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000273

Rodin J, Langer EJ (1977) Long-term effects of a control-relevant intervention with the institutionalized aged. J Pers Soc Psychol 35:897

Rothbaum F, Weisz JR, Snyder SS (1982) Changing the world and changing the self: a two-process model of perceived control. J Pers Soc Psychol 42:5–37. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.42.1.5

Rotter JB (1966) Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychol Monogr Gen Appl 80:1

Rowe JW, Kahn RL (1998) Successful aging. Pantheon/Random House, New York

Ruthig JC, Chipperfield JG, Newall NE, Perry RP, Hall NC (2007) Detrimental effects of falling on health and well-being in later life: the mediating roles of perceived control and optimism. J Health Psychol 12:231–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105307074250

Schulz R (1976) Effects of control and predictability on the physical and psychological well-being of the institutionalized aged. J Pers Soc Psychol 33:563

Schulz R, Heckhausen J (1999) Aging, culture and control: setting a new research agenda. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 54:P139–P145

Download references

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations Advanced Fellowship Program in Health Services Research, the Center for Healthcare Organization and Implementation Research (CHOIR), and Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial Veterans Hospital.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Center for Healthcare Organization and Implementation Research, Department of Veterans Affairs, Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial Veterans Hospital, Bedford, MA, USA

Stephanie A. Robinson

Department of Psychology, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA, USA

Margie E. Lachman

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Stephanie A. Robinson .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Population Division, Department of Economics and Social Affairs, United Nations, New York, NY, USA

Department of Population Health Sciences, Department of Sociology, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA

Matthew E. Dupre

Section Editor information

Institute of Psychogerontology, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg (FAU), Nürnberg, Germany

Susanne Wurm

Bielefeld University, Bielefeld, Germany

Anna E. Kornadt

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Robinson, S.A., Lachman, M.E. (2021). Locus of Control. In: Gu, D., Dupre, M.E. (eds) Encyclopedia of Gerontology and Population Aging. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22009-9_103

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22009-9_103

Published : 24 May 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-22008-2

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-22009-9

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

14.1: What is locus of control? How is it related to student achievement and assessment?

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 87641

- Jennfer Kidd, Jamie Kaufman, Peter Baker, Patrick O'Shea, Dwight Allen, & Old Dominion U students

- Old Dominion University

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

by Lucyna Russell

Learning Objectives

1. Readers will be able to understand what is locus of control.

2. Readers will know the difference between an internal and external locus of control.

3. Readers will learn how locus of control can affect student achievement.

4. Readers will learn what attribution training can do to help an external locus of control.

What is Locus of Control?

Do you believe that you are responsible for your fate or that fate is something that is determined. Depending on your answer can tell you what type of locus of control you may have. Locus of control is a psychological term that was developed by Julian B. Rotter in the 1950's (Neill,2006). Locus of control refers to an individuals beliefs about what determines their rewards or outcomes in life. Individuals locus of control can be classified along a specteum from internal to external (Mearns, 2006).

"Julian B. Rotter has been cited as one of the 100 most eminent psychologist of the 20th centrury. Rotter was 18th in frequency of citations in journal articles and 64th in overall eminence." (Haggbloom, 2002)

What are the Differences Between Internal and External Locus of Control?

A person who has an internal locus of control believes that their rewards in life are guided by their own decisions and efforts (Neill,2006). If they do not succeed at something, they believe it is due to their own lack of effort. For example, a student with an internal locus of control doesn't receive a good grade on his exam. He, therefore, concludes that he did not study enough for the exam. He realizes his efforts are what caused the grade and will have to try harder next time (Grantz, 2006).

A person who has an external locus of control believes that rewards or outcomes in life are determined by "luck, chance, or powerful others" (Mearns, 2008). If they do not succeed at something they believe that their lack of success is due to forces beyond their control. For example, a student with an external locus of control doesn't receive a good grade on his exam. He concludes that the test was written poorly and the teacher was incompetent. He blames the grade on external factors that were out of his control and doesn't see the need to try harder (Grantz, 2006).

- "Males tend to be more internal than females"

- "As people get older they tend to become more internal"

- "People higher up in organizational structures tend to be more internal"

(Neill, 2006)

How does Locus of Control Affect Student Achievement?

There have been a number of studies that conclude that there is a correlation between locus of control and academic achievement. These studies concluded that students with an internal locus of control had higher academic achievement than students with an external locus of control (Uget, 2007). The reason for the internals performing better academically comes from their belief that if they work hard and study, they will receive good grades. Therefore, they tend to study longer and spend more time on their homework (Grantz, 2006). On the other hand, externals believe they have no control over what grade they get. This belief may have been caused by many attempted school assignments that they failed, leading them to have low expectations of studying and school (Grantz, 2006). Any success that they might experience will be rationalized as luck or that the task was too easy. They have come to expect low success and whatever goals they do set are unrealistic (Uget, 2007).

Can an External Locus of Contol be Changed?

When there is a student in the classroom that seems to be having a hard time with his grades and shows no motivation for improvement that student may have an external locus of control. (Grantz, 2006). What can be done to help this student? Is there a way to motivate him? "Attribution training which concentrates on strenghthening the student's internal locus of control, may be helpful in increasing motivation" (Grantz, 2006). Part of attribution training is having say positive things about themselves. Some examples are, "I can do this" or "This can be done with hard work". Students train themselves into believing that they do have the control to change things (Grantz, 2006). Students should be encouraged to associate their academic hardships with the cause of their difficulties as they are being guided to see the effect of their actions (Uget, Habibah, Jegak 2007).

It seems that a persons locus of control can greatly affect their academic achievemnet. The way they perceive themselves and the world around them affects how well they will do in school. It only makes sense that if you work hard and study, then you will do well. However, students with an external locus of control do not feel that way and feel there is no need to try. This, of course, will greatly affect their academic achievement. Although there are ways of trying to change their thinking process, it may not be successful every time. It is important that we encourage our children at an early age and show them that hard work and diligence does make a difference.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

1. A student that believes he will get good grades if he works hard and studies has an/a

a. internal locus of conrol

b. external locus of control

c. locus of control

d. strong self esteem

2. A student that fails a test and says it was the teachers fault is said to have an/a

a. internal locus of control

d. low self esteem

3. Caleb is a third grade student who constantly says he cannot do the work, that it is too hard, and refuses to complete his tests would most likely have an/a. locus of control

a. locus of control

b. internal locus of control

c. low self esteem

d. external locus of control

4. Andrea is a fifth grade student who just failed a test. Andrea says to herself that she has to study more next time and try harder. Andrea has an/a. locus of control

c. internal locus of control

d. high self esteem

Grantz, Mandy. (2006). Do you have the power to succeed? Locus of control and its impact on education. Retrieved March 21, 2009, from http://www.units.muohio.edu/psybersite/control/education.shtml .

Haggbloom, S.J. et al. (2002). The 100 most eminent psychologists of the 20th century. Review of General Psychology,6,139-152.

Mearns, Jack. (2008). Social learning theory of Julian B. Rotter. Retrieved March 21, 2009, from http://psych.fullerton.edu/jmearns/rotter.htm .

Neill. James. (2006). What is locus of control? Retrieved March 21, 2009, from wilderdom.com/psychology/loc/LocusOfControlWhatIs.html.

Uget, A, Habibah, B., & Jegak, U. (2007). The influence of causal elements of control on academic achievement satisfaction. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 34(2), 120-8 Retrieved March 21, 2009, from education Full Text database.

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

7 Foundations of Locus of Control: Looking Back over a Half-Century of Research in Locus of Control of Reinforcement

- Published: September 2016

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Since its introduction by Julian Rotter in 1966, the construct of locus of control of reinforcement (LOC-R) appears to have evolved from a fairly clear and measurable variable into a complex system of varying definitions, measures, and applications. In this chapter, the authors review and evaluate this evolution. They first revisit the origins of LOC, then examine the adequacy and implications of the proliferation of terms like “perceived control” and others akin to it. The authors offer several examples of research paths that, in retrospect, they believe to have been salutary. Finally, based on their 45 year involvement in the study of LOC, they critically examine what they believe are the strengths and weaknesses in the literature on LOC and offer suggestions for future empirical and theoretical directions.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 2 |

| November 2022 | 5 |

| December 2022 | 4 |

| January 2023 | 10 |

| February 2023 | 9 |

| March 2023 | 5 |

| April 2023 | 2 |

| May 2023 | 7 |

| June 2023 | 3 |

| July 2023 | 2 |

| August 2023 | 2 |

| September 2023 | 2 |

| October 2023 | 6 |

| December 2023 | 4 |

| March 2024 | 8 |

| April 2024 | 10 |

| May 2024 | 8 |

| June 2024 | 3 |

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Locus of Control

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

When something goes wrong, it’s natural to cast blame on the perceived cause of the misfortune. Where an individual casts that blame can be related, in many cases, to a psychological construct known as “locus of control.”

- What Is Locus of Control?

- Self-Efficacy and Locus of Control

Locus of control refers to the degree to which an individual feels a sense of agency in regard to his or her life. Someone with an internal locus of control will believe that the things that happen to them are greatly influenced by their own abilities, actions, or mistakes. A person with an external locus of control will tend to feel that other forces—such as random chance, environmental factors, or the actions of others—are more responsible for the events that occur in the individual's life.

Like other constructs in personality psychology, locus of control falls on a spectrum. Genetic factors may influence one’s locus of control, as well as an individual’s childhood experiences—particularly the behaviors and attitudes modeled by their early caregivers.

Researchers have identified several areas in which one’s sense of control appears to affect outcomes, including education , health, and civic engagement. Overall, such research has generally suggested that those with a more internal locus of control are more successful, healthier, and happier than those with a more external locus.

Most people have either an internal or external locus of control. Those with an internal locus of control believe that their actions matter, and they are the authors of their own destiny. Those with an external locus of control attribute outcomes to circumstances or chance.

Many people believe that locus of control is something that you’re born with—an innate part of your personality. However, evidence suggests that parents can play a major role in how their child develops a locus of control. Encouraging a child’s independence and teaching them to associate actions with consequences can result in a better-developed internal locus of control.

Julian B. Rotter developed the locus of control concept in 1954, and it continues to play an important role in personality studies. In 1966, Rotter created a 13-item forced-choice scale in order to measure locus of control, though it is neither the only nor the most popular scale in use today.

Notice when you are self-victimizing or blaming other people for your hardships or negative feelings. Even if it’s true, try not to wallow in self-pity. Focus on the parts of the problem that are within your control—and let go of the rest, including the reactions of other people.

Another psychological concept related to locus of control is that of self-efficacy. Self-efficacy, as described by psychologist Albert Bandura, refers to one’s belief that they are able (or not able) to accomplish tasks and achieve their goals .

Though people with high self-efficacy also typically have a more internal locus of control, the two measures are not perfectly correlated. Someone, for example, may feel like they have the power to influence their own health while simultaneously feeling like they lack certain skills—such as cooking healthy meals—that would improve their health (high internal locus of control, but low self-efficacy).

Some research has suggested that one’s self-efficacy can be improved with practice, while locus of control is less easily influenced. There is some evidence, however, that one's locus of control may naturally change with age.

People with high self-efficacy also tend to have high self-sufficiency, an essential aspect of well-being. They are high in self-esteem, feel secure and content with themselves, and aren’t overly concerned with other people’s opinions of them. People with strong self-efficacy are more resilient and less likely to be destabilized by negative life events. Their locus of control is more likely to be internal than external.

There’s a powerful link between perceived control and health . The more that someone believes their actions determine their future, the more likely they are to engage in healthy behaviors, like eating well and exercising regularly. If, on the other hand, they feel like they have no control, such as when dealing with a terminal illness, they may experience negative symptoms, like stress and depression .

People with high self-efficacy and an internal locus of control tend to cope better with stress, because they feel like their actions make a difference. Meanwhile, those with an external locus of control or lower levels of self-efficacy are prone to feelings of helplessness, resulting in the excess release of the stress hormone cortisol. This, in turn, can lead to a sense of hopelessness and depression.

About 40 percent of people believe their partner is keeping secrets. Understanding why your partner might be hiding something can help you figure out how to cope.

If a relationship is awful, why don't they just leave? As it turns out, it is not that easy.

My disappointment taught me the value of radical acceptance and that our inner narratives define our experience.

Mentally traveling forward or backward in time can increase control, self-esteem, and coherence, according to a recent study. Here's how it works.

Temptation, low self-esteem, boredom, PTSD, and more.

Parents' desire for their children to cooperate and communicate with them can become harder to satisfy during adolescence.

We are acutely aware of the power of others to hurt us but not of our own power to hurt them. Why?

Although routines may seem to take away from spontaneity and surprises, for many, predictability and control are more satisfying.

For generations, Barbie has taught little girls that they can be anything. Barbie's big-screen story can teach everyone about authenticity and independence.

Improve concentration and cognition at work by avoiding this one activity.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

IResearchNet

What is Locus Of Control?

Locus of control (LOC) is a term used to refer to individual perceptions regarding personal control, particularly with regard to control over important outcomes. For example, have you ever tried to convince someone to vote, emphasizing the impact his or her vote could have in an election? Have you ever known someone who did not apply for a job promotion, deciding instead that his or her hard work did not matter as much as “who you know”? These examples illustrate how our motivation for performing a particular task may be influenced by how much we feel our actions influence certain outcomes or, conversely, the extent to which we feel end results will be due to forces outside of our control.

What Is Locus Of Control?