- Introduction

- Reading + Resources

- How-To-Guide

- Our Approach

- The Problem

- Our Process

- Crisis of the Free Press System Map

- Go to B.A. Program

Exercises, Assignments, and More

The activities below explore key principles and practices of community-centered journalism. they’re all designed to foster a spirit of playful experimentation in students— from this will emerge new and better ways of empowering communities through journalism..

These exercises and assignments can be used with any level of journalism student. Educators should feel free to tweak the specifics of the assignment while making use of the playful structure upon which they are built.

Resource Type

These exercises can be used with any level of journalism student. Educators should feel free to tweak the specifics of the assignment while making use of the playful structure upon which they are built.

Fairy Tale Ledes

Theme: journalism basics, type: exercises, interviewing 102: the transcript, layouts and wireframes, theme: design, jacob’s ladder ledes, mind-mapping and storyboarding, theme: general, mapping and observing, theme: general, design, empower the audience, theme: community news, meet the audience, the elevator pitch, theme: general, journalism basics, story development: look, listen, map, interviewing 101: the vox pop, style guide, style hunt, interviewing 101: the sit-down, what is news, questions to ask + habits to build, theme: systems thinking, uncover assumptions + beliefs driving the system, uncover patterns in your story, map your story as a system, identify key stakeholders + information needs, visualize the systems in your reporting, create a guiding vision for your reporting, journalism ethics, newspapers and community, developing community agreements, theme: general, community news, what’s at stake and how to address it, develop a north star, community engagement, theme: community news, systems thinking, surfacing underlying patterns in a system, longreads analysis, stakeholder mapping, capture, cluster, connect, activity cards, type: cards.

Below is a sampling of syllabi used in actual undergraduate Journalism + Design courses at The New School since the program began in Fall 2014. Some of these courses have been taught many times by multiple instructors, who continue to iterate as they teach them again. Others were one-time experiments. Whatever the case, each syllabus reflects events that were current at the time as well as the perspective and passions of the instructor. The syllabi also reflect access to New York’s rich professional communities of journalists and designers.

Designing Digital Communities

Theme: experimental, community news, type: syllabi, news, narrative & design i, visualizing data, theme: design, data, podcasting & audio narratives, theme: multimedia, expanding your audience: designing for accessibility, news, narrative & design ii, engagement journalism, reporting for visuals, interaction design for news apps, designing news games, theme: systems thinking, design, journalism design toolkit, theme: code, general, design for journalists, data journalism bootcamp, theme: data, news, narrative & design iii, facts/alternative facts, theme: general, experimental, race & ethnicity in journalism, feature writing for the 21st century, theme: experimental, product design strategy for news organizations, web fundamentals, theme: code, evaluation rubrics.

These evaluation tools can help assess student understanding of design processes and how they are applied to journalism practice. Use them at the end of a project as a tool for assessment or reflection.

Journalism + Design Process Rubric

Type: evaluation rubrics, questions or feedback.

We’d love to hear about your experiences using these resources. Let us know how we can improve! Email [email protected] or complete our Feedback Form

10 News Writing Exercises for Journalism Students

Test your ability to produce well written news stories on deadline

- Writing Essays

- Writing Research Papers

- English Grammar

- M.S., Journalism, Columbia University

- B.A., Journalism, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Looking for a way to hone your news writing skills ? Try these news writing exercises. Each provides a set of facts or a scenario, and it's up to you to produce a story from it. You'll have to fill in the blanks with imaginary but logical information that you compile. To get the maximum benefit, force yourself to do these on a tight deadline:

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

It's 10:30 p.m. You're on the night shift at the Centerville Gazette and hear some chatter on the police scanner about a car crash out on Highway 32, a road that runs through a rural area of town. It sounds like a big crash, so you head to the scene.

Peopleimages/Getty Images

You're on the night shift again at the Centerville Gazette. You phone the cops to see if anything's going on. Lt. Jane Ortlieb of the Centerville Police Department tells you there was a shooting tonight at the Fandango Bar & Grill on Wilson Street in the Grungeville section of the city.

Shooting Follow-Up No. 1

Hill Street Studios/Getty Images

You're back at the Centerville Gazette on the day after the shooting outside the Fandango Bar & Grill on Wilson Street in the Grungeville section of town. You phone the cops to see if they have anything new on the case. Lt. Jane Ortlieb tells you that early this morning they arrested an ex-con named Frederick Johnson, 32, in connection with the shooting.

Shooting Follow-Up No. 2

VisitBritain/Getty Images

It's the day after police arrested Frederick Johnson in connection with the shooting death of Peter Wickham outside the Fandango Bar & Grill. You call Lt. Jane Ortlieb of the Centerville Police Department. She tells you that cops are having a perp walk today to take Johnson to the Centerville District Courthouse for his arraignment. She says to be outside the courthouse at 10 a.m. sharp.

It's Tuesday morning at the Centerville Gazette. Making your usual phone checks, you get word from the fire department about a house fire early this morning. Deputy Fire Marshal Larry Johnson tells you the blaze was in a row house in the Cedar Glen section of the city.

School Board Meeting

You’re covering a 7 p.m. meeting of the Centerville School Board. The meeting is being held in the auditorium of Centerville High School. The board begins with a discussion of ongoing cleanup at McKinley Elementary School, which experienced water damage during heavy rains and flooding two weeks ago in the city’s Parksburg section, near the Root River.

Plane Crash

Paul A. Souders/Getty Images

It’s 9:30 p.m. You're on the night shift at the Centerville Gazette. You hear some chatter on the police scanner and call the cops. Lt. Jack Feldman says he’s not sure what’s happening but he thinks a plane crashed near Centerville Airport, a small facility used mostly by private pilots flying single-engine craft. Your editor tells you to get over there as fast as you can.

RubberBall Productions/Getty Images

You're on the day shift at the Centerville Gazette. The city editor gives you some information on a teacher who has died and tells you to bang out an obit. Here's the information: Evelyn Jackson, a retired teacher, died yesterday at the Good Samaritan Nursing Home, where she had lived for the past five years. She was 79 and died of natural causes. Jackson had worked for 43 years as an English teacher at Centerville High School before retiring in her late 60s. She taught classes in composition, American literature , and poetry.

Yuri_Arcurs/Getty Images

The Centerville Chamber of Commerce is holding its monthly luncheon at the Hotel Luxe. An audience of about 100, mostly local businessmen and women, is in attendance. The guest speaker today is Alex Weddell, CEO of Weddell Widgets, a local, family-owned manufacturing firm and one of the city’s largest employers.

Soccer Game

Photo and Co/Getty Images

You're a sportswriter for the Centerville Gazette. You’re covering a soccer game between the Centerville Community College Eagles and the Ipswich Community College Spartans. The game is for the state conference title.

- 7 Copy-Editing Exercises for Journalism Students

- 15 News Writing Rules for Beginning Journalism Students

- Writing a Compelling, Informative News Lede

- Here's How to Cover a Journalism Beat Effectively

- 6 Tips for Writing About Live Events

- Finding Stories to Cover in Your Hometown

- What Makes a Story Newsworthy

- Enterprise Reporting

- Stream of Consciousness Writing

- How to Avoid Burying the Lede of Your News Story

- What Is a Breaking News Story?

- Learn to Write News Stories

- 10 Important Steps for Producing a Quality News Story

- Find Ideas for Enterprise Stories in Your Hometown

- The History of Modern Policing

- The Assassination of President William McKinley

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Teaching Expertise

- Classroom Ideas

- Teacher’s Life

- Deals & Shopping

- Privacy Policy

15 Journalism Activities For Elementary Students: Writing, Reporting, Pitching, And More

November 8, 2023 // by Lauren Du Plessis

Our fun list of 15 investigative activities is all you need to get started presenting the concept of journalism to school students. Not only will the journalistic skills employed by these activities aid students who have a dream of pursuing this career path, but they will also benefit all learners from various walks of life. By including journalism activities in your lesson plans, you’ll teach your pupils how to analyze information, ask the right questions and develop a good understanding of the world around them.

1. Analyze The News

One of the key roles of a journalist is to analyze and report on current affairs. This activity requires learners to locate assorted news sources, list them in order of reliability- explaining why in the process, and lastly, select a handful of news items and stipulate what exactly classifies them as news.

Learn More: Worksheet Place

2. Journalism Crossword

This crossword is a wonderful activity for testing learners’ understanding of assorted journalism vocabulary in the field. It’s the perfect tie-in to your next journalism teaching unit and we guarantee that your students will want to complete a whole heap more!

Learn More: Word Mint

3. Brainstorm

Brainstorming the concepts of reporting and the press is a stellar introduction to journalism. Complete this activity as a class by analyzing news in different locations. To help get you started we’d recommend taking a look at the following; news at school, local news, and even global stories!

Learn More: Teachers Pay Teachers

4. Take A Quiz

Investigative journalism relies on a few important features in order to produce good and accurate content. This fun quiz will help you as a teacher test students’ knowledge of these features and ensure that they come to grips with the importance of these elements.

Learn More: Study

5. Conduct An Interview

One of the more predominant aspects of journalism is interviewing. By pairing up and conducting a simple interview, pupils come to understand the significance of asking the right questions when it comes to gathering information and conducting research in the field.

6. Fairy Tale Newspaper Reporting

Who would’ve thought that fairy tales could be linked to a journalism unit? Well, they certainly can and they create the perfect way to explore the correct format of a newspaper article. Using this resource, your students will also come to understand the importance of ordering their information correctly as well as reporting relevant facts and remaining unbiased.

7. Story Development

Story development is crucial for investigative journalists. This activity requires students to walk around a particular location- gathering information by recording their surroundings either in written, audio, or video format. They’ll then regroup and share their findings for discussion and analysis before devising a compelling story.

Learn More: Google Docs

8. The Elevator Pitch

Similar to someone presenting an elevator pitch, credible journalists should be able to piece together a compelling body of information. This activity requires students to come up with a short yet persuasive speech in order to pique the interest of an assigned organization or news team.

Learn More: Wyoming Department of Education

9. Write A News Story

Infamous journalists are renowned for reporting harsh realities and may even be rather grueling in their interviews. This activity calls for students to observe an event, question someone who was directly involved, and then write out a news story- ensuring that they include at least one direct quote from the interviewee and bringing all separate pieces of a story together.

Learn More: Resilient Educator

10. Play A Current Events Game

Staying on top of current events is one of the leading career roles that a journalist undertakes. As a class, decide on 5 categories that one might find in a newspaper before asking your students to search through a newspaper to find one article relevant to each category.

Learn More: Education World

11. The Inverted Pyramid

The inverted pyramid activity is the perfect model to demonstrate to your class how to structure a news article. The activity also gives them an opportunity to practice one of the key skills a good journalist must possess- the ability to listen and record accurate information.

Learn More: American English

12. Celebrity Interview

Journalism students often have the opportunity to work with people from all walks of life. Of course, this dictates that the type of questions one will ask will differ from one interview to the next. This activity encourages students to put together questions that are suited to interviewing a celebrity.

13. Record A Radio Program

Community journalism takes shape in a number of ways. One of the ways that local news is reported is via the radio. In order to record a radio program students will need to develop the skill of consolidating large bodies of information and practice reporting only the key facts of assorted stories.

Learn More: Paths To Literacy

14. Analyze Features Of Journalistic Writing

To develop a decent journalist profile, learners should learn the key features of journalistic intake, writing, and reporting. As a class, discuss the features together- prompting your learners to think deeper about the features by proposing simple questions about them.

Learn More: Twinkl

15. Read The Newspaper Together

This is an awesome follow on activity from the one above as it allows you to check your student’s understanding of the features of journalistic writing. Pull an extract from the newspaper to analyze together and ask your students to identify various features by either highlighting or circling them before labeling them.

Learn More: Secondary English Coffeeshop Blogspot

Worksheetplace.com For Great Educators

Journalism Teaching Activities

An introduction to journalism and news teaching activities. This is a free teaching unit that requires critical thinking and exposes students to news, news sources and how to write the news. Writing a good news lead and using the inverted pyramid structure to learn how to write news for both print and televised. A grades 7-10 teaching unit aligned to the ELA standards. These free journalism and media teaching activities are available in both google apps and print format.

All worksheets are created by experienced and qualified teachers. Send your suggestions or comments .

Teaching Journalism: 5 Journalism Lessons and Activities

You and your students will absolutely love these journalism lessons! The beginning of a new school year can be hectic for journalism teachers who are tasked with simultaneously teaching new journalism students who don’t have any journalism experience while also planning and publishing content for the school newspaper.

If your class is anything like mine, it is a mix of returning and new students. This year, I only have three returning students, so it is almost like I am starting entirely from scratch.

Here are 5 journalism lessons to teach at the beginning of the year

1. staff interview activity.

One of the very first assignments I have my students do is partner up with a fellow staff member that they don’t know and interview them. This activity works on two things: first, it helps the class get to know one another. Secondly, it helps students proactive their interviewing skills in a low-stakes environment.

For this activity, I have students come up with 10 interview questions, interview one another and do a quick write-up so that students can have practice recording their interviews.

Before this activity, I go over interviewing skills with my students. We discuss the dos and don’ts of interviewing, we brainstorm good interviewing questions, and we talk about the need to go beyond simple answer questions.

2. Staff Bio

Another great activity for the beginning of the year is to have students write their staff bio. This provides students with an opportunity to write in the third person while also providing the most important information.

For my staff bios, I give students 80-100 words. I have them write their bios in the third person and in the present tense.

3. Collaborative News Story

For our first news story of the school year, I like to write one collaboratively as a staff. We go over the basics of journalism writing and then write together in one Google Doc. I do this as a learning activity so that new staff can see how we write journalistically. First, I have students work together in small groups to write the lead. Then, as a class, we craft one together. From there, we move on to building the story.

As we write the story, as a staff, we can then see what kind of information we need. I assign small groups of students to interview people and find quotes. Those groups then add that information to the story.

Once it is written, we edit and review the story together before it is published. This activity is particularly helpful because students get to see how we format quotes in our stories, how we refer to students and teachers in our stories, and how we go about the news-gathering process.

Once our collaborative story is done, new staff then have the green light to begin writing their own stories.

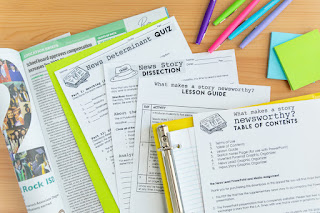

4. The News Determinants

You can also read more in-depth about the news determinants with this blog post about teaching the five news determinants .

5. AP Style Writing

As students are writing their first stories, I like to teach students about AP Style . I use this instructional presentation, and students assemble their AP Style mini flip books that they use as a reference all year long.

The news determinants and AP Style lessons are included in my journalism curriculum with many other resources that will make teaching and advising the middle school or high school newspaper much easier.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

Basic newswriting: Learn how to originate, research and write breaking-news stories

Syllabus for semester-long course on the fundamentals of covering and writing the news, including how identify a story, gather information efficiently and place it in a meaningful context.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by The Journalist's Resource, The Journalist's Resource January 22, 2010

This <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org/home/syllabus-covering-the-news/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org">The Journalist's Resource</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src="https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cropped-jr-favicon-150x150.png" style="width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;">

This course introduces tomorrow’s journalists to the fundamentals of covering and writing news. Mastering these skills is no simple task. In an Internet age of instantaneous access, demand for high-quality accounts of fast-breaking news has never been greater. Nor has the temptation to cut corners and deliver something less.

To resist this temptation, reporters must acquire skills to identify a story and its essential elements, gather information efficiently, place it in a meaningful context, and write concise and compelling accounts, sometimes at breathtaking speed. The readings, discussions, exercises and assignments of this course are designed to help students acquire such skills and understand how to exercise them wisely.

Photo: Memorial to four slain Lakewood, Wash., police officers. The Seattle Times earned the 2010 Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News Reporting for their coverage of the crime.

Course objective

To give students the background and skills needed to originate, research, focus and craft clear, compelling and contextual accounts of breaking news in a deadline environment.

Learning objectives

- Build an understanding of the role news plays in American democracy.

- Discuss basic journalistic principles such as accuracy, integrity and fairness.

- Evaluate how practices such as rooting and stereotyping can undermine them.

- Analyze what kinds of information make news and why.

- Evaluate the elements of news by deconstructing award-winning stories.

- Evaluate the sources and resources from which news content is drawn.

- Analyze how information is attributed, quoted and paraphrased in news.

- Gain competence in focusing a story’s dominant theme in a single sentence.

- Introduce the structure, style and language of basic news writing.

- Gain competence in building basic news stories, from lead through their close.

- Gain confidence and competence in writing under deadline pressure.

- Practice how to identify, background and contact appropriate sources.

- Discuss and apply the skills needed to interview effectively.

- Analyze data and how it is used and abused in news coverage.

- Review basic math skills needed to evaluate and use statistics in news.

- Report and write basic stories about news events on deadline.

Suggested reading

- A standard textbook of the instructor’s choosing.

- America ‘s Best Newspaper Writing , Roy Peter Clark and Christopher Scanlan, Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2006

- The Elements of Journalism , Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel, Three Rivers Press, 2001.

- Talk Straight, Listen Carefully: The Art of Interviewing , M.L. Stein and Susan E. Paterno, Iowa State University Press, 2001

- Math Tools for Journalists , Kathleen Woodruff Wickham, Marion Street Press, Inc., 2002

- On Writing Well: 30th Anniversary Edition , William Zinsser, Collins, 2006

- Associated Press Stylebook 2009 , Associated Press, Basic Books, 2009

Weekly schedule and exercises (13-week course)

We encourage faculty to assign students to read on their own Kovach and Rosentiel’s The Elements of Journalism in its entirety during the early phase of the course. Only a few chapters of their book are explicitly assigned for the class sessions listed below.

The assumption for this syllabus is that the class meets twice weekly.

Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 | Week 7 Week 8 | Week 9 | Week 10 | Week 11 | Week 12 | Weeks 13/14

Week 1: Why journalism matters

Previous week | Next week | Back to top

Class 1: The role of journalism in society

The word journalism elicits considerable confusion in contemporary American society. Citizens often confuse the role of reporting with that of advocacy. They mistake those who promote opinions or push their personal agendas on cable news or in the blogosphere for those who report. But reporters play a different role: that of gatherer of evidence, unbiased and unvarnished, placed in a context of past events that gives current events weight beyond the ways opinion leaders or propagandists might misinterpret or exploit them.

This session’s discussion will focus on the traditional role of journalism eloquently summarized by Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel in The Elements of Journalism . The class will then examine whether they believe that the journalist’s role has changed or needs to change in today’s news environment. What is the reporter’s role in contemporary society? Is objectivity, sometimes called fairness, an antiquated concept or an essential one, as the authors argue, for maintaining a democratic society? How has the term been subverted? What are the reporter’s fundamental responsibilities? This discussion will touch on such fundamental issues as journalists’ obligation to the truth, their loyalty to the citizens who are their audience and the demands of their discipline to verify information, act independently, provide a forum for public discourse and seek not only competing viewpoints but carefully vetted facts that help establish which viewpoints are grounded in evidence.

Reading: Kovach and Rosenstiel, Chapter 1, and relevant pages of the course text

Assignments:

- Students should compare the news reporting on a breaking political story in The Wall Street Journal , considered editorially conservative, and The New York Times , considered editorially liberal. They should write a two-page memo that considers the following questions: Do the stories emphasize the same information? Does either story appear to slant the news toward a particular perspective? How? Do the stories support the notion of fact-based journalism and unbiased reporting or do they appear to infuse opinion into news? Students should provide specific examples that support their conclusions.

- Students should look for an example of reporting in any medium in which reporters appear have compromised the notion of fairness to intentionally or inadvertently espouse a point of view. What impact did the incorporation of such material have on the story? Did its inclusion have any effect on the reader’s perception of the story?

Class 2: Objectivity, fairness and contemporary confusion about both

In his book Discovering the News , Michael Schudson traced the roots of objectivity to the era following World War I and a desire by journalists to guard against the rapid growth of public relations practitioners intent on spinning the news. Objectivity was, and remains, an ideal, a method for guarding against spin and personal bias by examining all sides of a story and testing claims through a process of evidentiary verification. Practiced well, it attempts to find where something approaching truth lies in a sea of conflicting views. Today, objectivity often is mistaken for tit-for-tat journalism, in which the reporters only responsibility is to give equal weight to the conflicting views of different parties without regard for which, if any, are saying something approximating truth. This definition cedes the journalist’s responsibility to seek and verify evidence that informs the citizenry.

Focusing on the “Journalism of Verification” chapter in The Elements of Journalism , this class will review the evolution and transformation of concepts of objectivity and fairness and, using the homework assignment, consider how objectivity is being practiced and sometimes skewed in the contemporary new media.

Reading: Kovach and Rosenstiel, Chapter 4, and relevant pages of the course text.

Assignment: Students should evaluate stories on the front page and metro front of their daily newspaper. In a two-page memo, they should describe what elements of news judgment made the stories worthy of significant coverage and play. Finally, they should analyze whether, based on what else is in the paper, they believe the editors reached the right decision.

Week 2: Where news comes from

Class 1: News judgment

When editors sit down together to choose the top stories, they use experience and intuition. The beginner journalist, however, can acquire a sense of news judgment by evaluating news decisions through the filter of a variety of factors that influence news play. These factors range from traditional measures such as when the story took place and how close it was to the local readership area to more contemporary ones, such as the story’s educational value.

Using the assignment and the reading, students should evaluate what kinds of information make for interesting news stories and why.

In this session, instructors might consider discussing the layers of news from the simplest breaking news event to the purely enterprise investigative story.

Assignment: Students should read and deconstruct coverage of a major news event. One excellent source for quality examples is the site of the Pulitzer Prizes , which has a category for breaking news reporting. All students should read the same article (assigned by the instructor), and write a two- or three-page memo that describes how the story is organized, what information it contains and what sources of information it uses, both human and digital. Among the questions they should ask are:

- Does the first (or lead) paragraph summarize the dominant point?

- What specific information does the lead include?

- What does it leave out?

- How do the second and third paragraphs relate to the first paragraph and the information it contains? Do they give unrelated information, information that provides further details about what’s established in the lead paragraph or both?

- Does the story at any time place the news into a broader context of similar events or past events? If so, when and how?

- What information in the story is attributed , specifically tied to an individual or to documentary information from which it was taken? What information is not attributed? Where does the information appear in the sentence? Give examples of some of the ways the sources of information are identified? Give examples of the verbs of attribution that are chosen.

- Where and how often in the story are people quoted, their exact words placed in quotation marks? What kind of information tends to be quoted — basic facts or more colorful commentary? What information that’s attributed is paraphrased , summing up what someone said but not in their exact words.

- How is the story organized — by theme, by geography, by chronology (time) or by some other means?

- What human sources are used in the story? Are some authorities? Are some experts? Are some ordinary people affected by the event? Who are some of the people in each category? What do they contribute to the story? Does the reporter (or reporters) rely on a single source or a wide range? Why do you think that’s the case?

- What specific facts and details make the story more vivid to you? How do you think the reporter was able to gather those details?

- What documents (paper or digital) are detailed in the story? Do they lend authority to the story? Why or why not?

- Is any specific data (numbers, statistics) used in the story? What does it lend to the story? Would you be satisfied substituting words such as “many” or “few” for the specific numbers and statistics used? Why or why not?

Class 2: Deconstructing the story

By carefully deconstructing major news stories, students will begin to internalize some of the major principles of this course, from crafting and supporting the lead of a story to spreading a wide and authoritative net for information. This class will focus on the lessons of a Pulitzer Prize winner.

Reading: Clark/Scanlan, Pages 287-294

Assignment: Writers typically draft a focus statement after conceiving an idea and conducting preliminary research or reporting. This focus statement helps to set the direction of reporting and writing. Sometimes reporting dictates a change of direction. But the statement itself keeps the reporter from getting off course. Focus statements typically are 50 words or less and summarize the story’s central point. They work best when driven by a strong, active verb and written after preliminary reporting.

- Students should write a focus statement that encapsulates the news of the Pulitzer Prize winning reporting the class critiqued.

Week 3: Finding the focus, building the lead

Class 1: News writing as a process

Student reporters often conceive of writing as something that begins only after all their reporting is finished. Such an approach often leaves gaps in information and leads the reporter to search broadly instead of with targeted depth. The best reporters begin thinking about story the minute they get an assignment. The approach they envision for telling the story informs their choice of whom they seek interviews with and what information they gather. This class will introduce students to writing as a process that begins with story concept and continues through initial research, focus, reporting, organizing and outlining, drafting and revising.

During this session, the class will review the focus statements written for homework in small breakout groups and then as a class. Professors are encouraged to draft and hand out a mock or real press release or hold a mock press conference from which students can draft a focus statement.

Reading: Zinsser, pages 1-45, Clark/Scanlan, pages 294-302, and relevant pages of the course text

Class 2: The language of news

Newswriting has its own sentence structure and syntax. Most sentences branch rightward, following a pattern of subject/active verb/object. Reporters choose simple, familiar words. They write spare, concise sentences. They try to make a single point in each. But journalistic writing is specific and concrete. While reporters generally avoid formal or fancy word choices and complex sentence structures, they do not write in generalities. They convey information. Each sentence builds on what came before. This class will center on the language of news, evaluating the language in selections from America’s Best Newspaper Writing , local newspapers or the Pulitzers.

Reading: Relevant pages of the course text

Assignment: Students should choose a traditional news lead they like and one they do not like from a local or national newspaper. In a one- or two-page memo, they should print the leads, summarize the stories and evaluate why they believe the leads were effective or not.

Week 4: Crafting the first sentence

Class 1: The lead

No sentence counts more than a story’s first sentence. In most direct news stories, it stands alone as the story’s lead. It must summarize the news, establish the storyline, convey specific information and do all this simply and succinctly. Readers confused or bored by the lead read no further. It takes practice to craft clear, concise and conversational leads. This week will be devoted to that practice.

Students should discuss the assigned leads in groups of three or four, with each group choosing one lead to read to the entire class. The class should then discuss the elements of effective leads (active voice; active verb; single, dominant theme; simple sentences) and write leads in practice exercises.

Assignment: Have students revise the leads they wrote in class and craft a second lead from fact patterns.

Class 2: The lead continued

Some leads snap or entice instead of summarize. When the news is neither urgent nor earnest, these can work well. Though this class will introduce students to other kinds of leads, instructors should continue to emphasize traditional leads, typically found atop breaking news stories.

Class time should largely be devoted to writing traditional news leads under a 15-minute deadline pressure. Students should then be encouraged to read their own leads aloud and critique classmates’ leads. At least one such exercise might focus on students writing a traditional lead and a less traditional lead from the same information.

Assignment: Students should find a political or international story that includes various types (direct and indirect) and levels (on-the-record, not for attribution and deep background) of attribution. They should write a one- or two-page memo describing and evaluating the attribution. Did the reporter make clear the affiliation of those who expressed opinions? Is information attributed to specific people by name? Are anonymous figures given the opportunity to criticize others by name? Is that fair?

Week 5: Establishing the credibility of news

Class 1: Attribution

All news is based on information, painstakingly gathered, verified and checked again. Even so, “truth” is an elusive concept. What reporters cobble together instead are facts and assertions drawn from interviews and documentary evidence.

To lend authority to this information and tell readers from where it comes, reporters attribute all information that is not established fact. It is neither necessary, for example, to attribute that Franklin Delano Roosevelt was first elected president in 1932 nor that he was elected four times. On the other hand, it would be necessary to attribute, at least indirectly, the claim that he was one of America’s best presidents. Why? Because that assertion is a matter of opinion.

In this session, students should learn about different levels of attribution, where attribution is best placed in a sentence, and why it can be crucial for the protection of the accused, the credibility of reporters and the authoritativeness of the story.

Assignment: Working from a fact pattern, students should write a lead that demands attribution.

Class 2: Quoting and paraphrasing

“Great quote,” ranks closely behind “great lead” in the pecking order of journalistic praise. Reporters listen for great quotes as intensely as piano tuners listen for the perfect pitch of middle C. But what makes a great quote? And when should reporters paraphrase instead?

This class should cover a range of issues surrounding the quoted word from what it is used to convey (color and emotion, not basic information) to how frequently quotes should be used and how long they should run on. Other issues include the use and abuse of partial quotes, when a quote is not a quote, and how to deal with rambling and ungrammatical subjects.

As an exercise, students might either interview the instructor or a classmate about an exciting personal experience. After their interviews, they should review their notes choose what they consider the three best quotes to include a story on the subject. They should then discuss why they chose them.

Assignment: After completing the reading, students should analyze a summary news story no more than 15 paragraphs long. In a two- or three-page memo, they should reprint the story and then evaluate whether the lead summarizes the news, whether the subsequent paragraphs elaborate on or “support” the lead, whether the story has a lead quote, whether it attributes effectively, whether it provides any context for the news and whether and how it incorporates secondary themes.

Week 6: The building blocks of basic stories

Class 1: Supporting the lead

Unlike stories told around a campfire or dinner table, news stories front load information. Such a structure delivers the most important information first and the least important last. If a news lead summarizes, the subsequent few paragraphs support or elaborate by providing details the lead may have merely suggested. So, for example, a story might lead with news that a 27-year-old unemployed chef has been arrested on charges of robbing the desk clerk of an upscale hotel near closing time. The second paragraph would “support” this lead with detail. It would name the arrested chef, identify the hotel and its address, elaborate on the charges and, perhaps, say exactly when the robbery took place and how. (It would not immediately name the desk clerk; too many specifics at once clutter the story.)

Wire service stories use a standard structure in building their stories. First comes the lead sentence. Then comes a sentence or two of lead support. Then comes a lead quote — spoken words that reinforce the story’s direction, emphasize the main theme and add color. During this class students should practice writing the lead through the lead quote on deadline. They should then read assignments aloud for critique by classmates and the professor.

Assignment: Using a fact pattern assigned by the instructor or taken from a text, students should write a story from the lead through the lead quote. They should determine whether the story needs context to support the lead and, if so, include it.

Class 2: When context matters

Sometimes a story’s importance rests on what came before. If one fancy restaurant closes its doors in the face of the faltering economy, it may warrant a few paragraphs mention. If it’s the fourth restaurant to close on the same block in the last two weeks, that’s likely front-page news. If two other restaurants closed last year, that might be worth noting in the story’s last sentence. It is far less important. Patterns provide context and, when significant, generally are mentioned either as part of the lead or in the support paragraph that immediately follows. This class will look at the difference between context — information needed near the top of a story to establish its significance as part of a broader pattern, and background — information that gives historical perspective but doesn’t define the news at hand.

Assignment: The course to this point has focused on writing the news. But reporters, of course, usually can’t write until they’ve reported. This typically starts with background research to establish what has come before, what hasn’t been covered well and who speaks with authority on an issue. Using databases such as Lexis/Nexis, students should background or read specific articles about an issue in science or policy that either is highlighted in the Policy Areas section of Journalist’s Resource website or is currently being researched on your campus. They should engage in this assignment knowing that a new development on the topic will be brought to light when they arrive at the next class.

Week 7: The reporter at work

Class 1: Research

Discuss the homework assignment. Where do reporters look to background an issue? How do they find documents, sources and resources that enable them to gather good information or identify key people who can help provide it? After the discussion, students should be given a study from the Policy Areas section of Journalist’s Resource website related to the subject they’ve been asked to explore.

The instructor should use this study to evaluate the nature structure of government/scientific reports. After giving students 15 minutes to scan the report, ask students to identify its most newsworthy point. Discuss what context might be needed to write a story about the study or report. Discuss what concepts or language students are having difficulty understanding.

Reading: Clark, Scanlan, pages 305-313, and relevant pages of the course text

Assignment: Students should (a) write a lead for a story based exclusively on the report (b) do additional background work related to the study in preparation for writing a full story on deadline. (c) translate at least one term used in the study that is not familiar to a lay audience.

Class 2: Writing the basic story on deadline

This class should begin with a discussion of the challenges of translating jargon and the importance of such translation in news reporting. Reporters translate by substituting a simple definition or, generally with the help of experts, comparing the unfamiliar to the familiar through use of analogy.

The remainder of the class should be devoted to writing a 15- to 20-line news report, based on the study, background research and, if one is available, a press release.

Reading: Pages 1-47 of Stein/Paterno, and relevant pages of the course text

Assignment: Prepare a list of questions that you would ask either the lead author of the study you wrote about on deadline or an expert who might offer an outside perspective.

Week 8: Effective interviewing

Class 1: Preparing and getting the interview

Successful interviews build from strong preparation. Reporters need to identify the right interview subjects, know what they’ve said before, interview them in a setting that makes them comfortable and ask questions that elicit interesting answers. Each step requires thought.

The professor should begin this class by critiquing some of the questions students drew up for homework. Are they open-ended or close-ended? Do they push beyond the obvious? Do they seek specific examples that explain the importance of the research or its applications? Do they probe the study’s potential weaknesses? Do they explore what directions the researcher might take next?

Discuss the readings and what steps reporters can take to background for an interview, track down a subject and prepare and rehearse questions in advance.

Reading: Stein/Paterno, pages 47-146, and relevant pages of the course text

Assignment: Students should prepare to interview their professor about his or her approach to and philosophy of teaching. Before crafting their questions, the students should background the instructor’s syllabi, public course evaluations and any pertinent writings.

Class 2: The interview and its aftermath

The interview, says Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Jacqui Banaszynski, is a dance which the reporter leads but does so to music the interview subject chooses. Though reporters prepare and rehearse their interviews, they should never read the questions they’ve considered in advance and always be prepared to change directions. To hear the subject’s music, reporters must be more focused on the answers than their next question. Good listeners make good interviewers — good listeners, that is, who don’t forget that it is also their responsibility to also lead.

Divide the class. As a team, five students should interview the professor about his/her approach to teaching. Each of these five should build on the focus and question of the previous questioner. The rest of the class should critique the questions, their clarity and their focus. Are the questioners listening? Are they maintaining control? Are they following up? The class also should discuss the reading, paying particularly close attention to the dynamics of an interview, the pace of questions, the nature of questions, its close and the reporter’s responsibility once an interview ends.

Assignment: Students should be assigned to small groups and asked to critique the news stories classmates wrote on deadline during the previous class.

Week 9: Building the story

Class 1: Critiquing the story

The instructor should separate students into groups of two or three and tell them to read their news stories to one another aloud. After each reading, the listeners should discuss what they liked and struggled with as the story audience. The reader in each case should reflect on what he or she learned from the process of reading the story aloud.

The instructor then should distribute one or two of the class stories that provide good and bad examples of story structure, information selection, content, organization and writing. These should be critiqued as a class.

Assignment: Students, working in teams, should develop an angle for a news follow to the study or report they covered on deadline. Each team should write a focus statement for the story it is proposing.

Class 2: Following the news

The instructor should lead a discussion about how reporters “enterprise,” or find original angles or approaches, by looking to the corners of news, identifying patterns of news, establishing who is affected by news, investigating the “why” of news, and examining what comes next.

Students should be asked to discuss the ideas they’ve developed to follow the news story. These can be assigned as longer-term team final projects for the semester. As part of this discussion, the instructor can help students map their next steps.

Reading: Wickham, Chapters 1-4 and 7, and relevant pages of the course text

Assignment: Students should find a news report that uses data to support or develop its main point. They should consider what and how much data is used, whether it is clear, whether it’s cluttered and whether it answers their questions. They should bring the article and a brief memo analyzing it to class.

Week 10: Making sense of data and statistics

Class 1: Basic math and the journalist’s job

Many reporters don’t like math. But in their jobs, it is everywhere. Reporters must interpret political polls, calculate percentage change in everything from property taxes to real estate values, make sense of municipal bids and municipal budgets, and divine data in government reports.

First discuss some of the examples of good and bad use of data that students found in their homework. Then, using examples from Journalist’s Resource website, discuss good and poor use of data in news reporting. (Reporters, for example, should not overwhelm readers with paragraphs stuffed with statistics.) Finally lead students through some of the basic skills sets outlined in Wickham’s book, using her exercises to practice everything from calculating percentage change to interpreting polls.

Assignment: Give students a report or study linked to the Journalist’s Resource website that requires some degree of statistical evaluation or interpretation. Have students read the report and compile a list of questions they would ask to help them understand and interpret this data.

Class 2: The use and abuse of statistics

Discuss the students’ questions. Then evaluate one or more articles drawn from the report they’ve analyzed that attempt to make sense of the data in the study. Discuss what these articles do well and what they do poorly.

Reading: Zinsser, Chapter 13, “Macabre Reminder: The Corpse on Union Street,” Dan Barry, The New York Times

Week 11: The reporter as observer

Class 1: Using the senses

Veteran reporters covering an event don’t only return with facts, quotes and documents that support them. They fill their notebooks with details that capture what they’ve witnessed. They use all their senses, listening for telling snippets of conversation and dialogue, watching for images, details and actions that help bring readers to the scene. Details that develop character and place breathe vitality into news. But description for description’s sake merely clutters and obscures the news. Using the senses takes practice.

The class should deconstruct “Macabre Reminder: The Corpse on Union Street,” a remarkable journey around New Orleans a few days after Hurricane Katrina devastated the city in 2005. The story starts with one corpse, left to rot on a once-busy street and then pans the city as a camera might. The dead body serves as a metaphor for the rotting city, largely abandoned and without order.

Assignment: This is an exercise in observation. Students may not ask questions. Their task is to observe, listen and describe a short scene, a serendipitous vignette of day-to-day life. They should take up a perch in a lively location of their choosing — a student dining hall or gym, a street corner, a pool hall or bus stop or beauty salon, to name a few — wait and watch. When a small scene unfolds, one with beginning, middle and end, students should record it. They then should write a brief story describing the scene that unfolded, taking care to leave themselves and their opinions out of the story. This is pure observation, designed to build the tools of observation and description. These stories should be no longer than 200 words.

Class 2: Sharpening the story

Students should read their observation pieces aloud to a classmate. Both students should consider these questions: Do the words describe or characterize? Which words show and which words tell? What words are extraneous? Does the piece convey character through action? Does it have a clear beginning, middle and end? Students then should revise, shortening the original scene to no longer than 150 words. After the revision, the instructor should critique some of the students’ efforts.

Assignment: Using campus, governmental or media calendars, students should identify, background and prepare to cover a speech, press conference or other news event, preferably on a topic related to one of the research-based areas covered in the Policy Areas section of Journalist’s Resource website. Students should write a focus statement (50 words or less) for their story and draw up a list of some of the questions they intend to ask.

Week 12: Reporting on deadline

Class 1: Coaching the story

Meetings, press conferences and speeches serve as a staple for much news reporting. Reporters should arrive at such events knowledgeable about the key players, their past positions or research, and the issues these sources are likely discuss. Reporters can discover this information in various ways. They can research topic and speaker online and in journalistic databases, peruse past correspondence sent to public offices, and review the writings and statements of key speakers with the help of their assistants or secretaries.

In this class, the instructor should discuss the nature of event coverage, review students’ focus statements and questions, and offer suggestions about how they cover the events.

Assignment: Cover the event proposed in the class above and draft a 600-word story, double-spaced, based on its news and any context needed to understand it.

Class 2: Critiquing and revising the story

Students should exchange story drafts and suggest changes. After students revise, the instructor should lead a discussion about the challenges of reporting and writing live on deadline. These likely will include issues of access and understanding and challenges of writing around and through gaps of information.

Weeks 13/14: Coaching the final project

Previous week | Back to top

The final week or two of the class is reserved for drill in areas needing further development and for coaching students through the final reporting, drafting and revision of the enterprise stories off the study or report they covered in class.

Tags: training

About The Author

The Journalist's Resource

Mizzou Logo

Missouri School of Journalism

University of missouri, resources for high school teachers.

Missouri School of Journalism high school journalism project: Free, online teaching resources for scholastic journalism teachers.

Choose from 25 modules to help you teach skills used in journalism, yearbook and related topics.

Individual module landing pages set you up with an overview of the lesson’s activities:

- Complete lesson plan

- “Do” activities

- Worksheets, examples and answer keys to support activities

- Readings and resources

- Various types of formative assessment

- A summative assessment at the end of each lesson in the form of a 10-question multiple choice quiz with feedback on correct and incorrect answers

- The plans also state the learning objectives to which those activities and readings are aligned and sets the expectations.

Please contact Professor Amy Simons at [email protected]

Get started today!

Shop officially licensed merch at our J-School Store. All profits go toward our scholarship fund.

Share your story.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Common Writing Assignments

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

These OWL resources will help you understand and complete specific types of writing assignments, such as annotated bibliographies, book reports, and research papers. This section also includes resources on writing academic proposals for conference presentations, journal articles, and books.

Understanding Writing Assignments

This resource describes some steps you can take to better understand the requirements of your writing assignments. This resource works for either in-class, teacher-led discussion or for personal use.

Argument Papers

This resource outlines the generally accepted structure for introductions, body paragraphs, and conclusions in an academic argument paper. Keep in mind that this resource contains guidelines and not strict rules about organization. Your structure needs to be flexible enough to meet the requirements of your purpose and audience.

Research Papers

This handout provides detailed information about how to write research papers including discussing research papers as a genre, choosing topics, and finding sources.

Exploratory Papers

This resource will help you with exploratory/inquiry essay assignments.

Annotated Bibliographies

This handout provides information about annotated bibliographies in MLA, APA, and CMS.

Book Report

This resource discusses book reports and how to write them.

Definitions

This handout provides suggestions and examples for writing definitions.

Essays for Exams

While most OWL resources recommend a longer writing process (start early, revise often, conduct thorough research, etc.), sometimes you just have to write quickly in test situations. However, these exam essays can be no less important pieces of writing than research papers because they can influence final grades for courses, and/or they can mean the difference between getting into an academic program (GED, SAT, GRE). To that end, this resource will help you prepare and write essays for exams.

Book Review

This resource discusses book reviews and how to write them.

Academic Proposals

This resource will help undergraduate, graduate, and professional scholars write proposals for academic conferences, articles, and books.

In this section

Subsections.

Lesson Plan November 17, 2017

The Paradise Papers: A Lesson in Investigative Journalism

Printable PDFs/Word Documents for this Lesson:

- Full lesson for students [PDF] [Word]

- Project Description for the Paradise Papers [PDF]

Objectives:

Students will be able to:

- Describe the process, identify the purpose, and evaluate the impact of investigative journalism

- Evaluate the use of different types of media in acheiving particular aims

- Create a resource that clearly and engagingly conveys information about the Paradise Papers

BREAKING NEWS! On your desk, you will find an envelope with a number written on it and a note card inside. On that note card, there is a tip —a piece of news about your school, neighborhood, or community that someone powerful doesn't want you to know. Your source (the person who left the envelope for you) has chosen to remain anonymous, meaning you don't know who they are. Your source's information might be true or untrue.

1. Brainstorm on your own:

- What steps could you take to determine whether this information is true and what the fuller story behind it is?

- What would be the benefits and drawbacks of keeping this information secret while you investigated it further?

- If you shared this information, who would be affected and how?

2. Find a partner who has an envelope with the same number as your own. Take 3 minutes to merge the steps you brainstormed into a single action plan, and discuss how you can most effectively work together. Then, take another two minutes to discuss what you will do with the information once you have thoroughly investigated it.

3. Discuss as a class:

- What advantages and disadvantages can you see to working with a partner on your investigation?

A few students should share their tip, plan for investigation, and plan for distributing information. The class can then discuss the potential impact of that story.

Introducing the Lesson:

UNESCO defines investigative journalism as "the unveiling of matters that are concealed either deliberately by someone in a position of power, or accidentally, behind a chaotic mass of facts and circumstances - and the analysis and exposure of all relevant facts to the public."

Investigative reporting projects can begin in many ways. Sometimes, a journalist notices a problem or something suspicious themselves and decides to research it some more. Other times, they receive a tip from a source and work to determine whether it is true and what the full story is. In still other cases, a source might provide a leak (send secret information), supplying all the necessary documentation, but requiring the journalist to piece together a narrative from the information and find a way to present it to the public.

- Are you familiar with any investigative journalism stories?

- What do you think is the difference between investigative journalism and other types of journalism?

Today, we are going to learn more about investigative journalists and their work by examining the Paradise Papers, a project from the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). This project exposes how political leaders, businesspeople, and the wealthy elite around the world use offshore entities to avoid taxes and cover up wrongdoing. With about 400 journalists working on 6 continents and in 30 languages to examine 13.4 million files for nearly an entire year, it is one of the largest investigative journalism projects in history.

Following this lesson, you will create a resource to clearly and engagingly convey information you have learned from the Paradise Papers to a lay audience, a vital part of investigative journalism.

Introducing Resource 1: " The True Story Behind the Secret Nine-Month Paradise Papers Investigation "

1. After watching the video, work individually or with a partner to create a short summary of what the Paradise Papers are and why they matter.

2. In the video, ICIJ Deputy Director Marina Walker says, "At ICIJ, the mission is to uncover those urgent stories of public interest that go beyond what any particular journalist or media organization can accomplish on his or her own." Consider:

- What is the ICIJ? How does it differ from other news outlets/organizations you are familiar with?

- How would you define a "story of public interest"?

- Why does the ICIJ work with journalists based all over the world?

3. This video introduces many reporters and shows them doing the behind-the-scenes work of investigative journalism. Discuss as a class:

- How would you describe the day-to-day work of an investigative journalist, based on what the video showed? What are their workplaces like? Did anything surprise you?

- What skills do you think are essential for an investigative journalist to have, and why?

- How does the job differ for journalists in different countries?

- What are some of the dangers of investigative journalism, and how do journalists cope with them?

- Investigative journalist Will Fitzgibbon mentions ICIJ's emphasis on releasing all information simultaneously as a team. What are some of the advantages and disadvantages to reporting this way?

Introducing Resource 2: Paradise Papers

1. Read the project description of the Paradise Papers on the Pulitzer Center website. Discuss: how do the summary and statement of import you wrote with your partner compare?

2. Next, explore the interactive within the project, " Paradise Papers: The Influencers ."

- What is your initial reaction to the interactive? How does it make you feel?

- Click through to read the stories about Wilbur Ross. What sections are included in the story, and what purpose do they serve? Do you find the information convincing? Easy to understand? Interesting?

- Take a look at one of the supporting documents . What is your initial reaction? How does it make you feel?

- What do you think the purpose of this interactive is? How effective is it in serving this purpose?

Activity and Discussion:

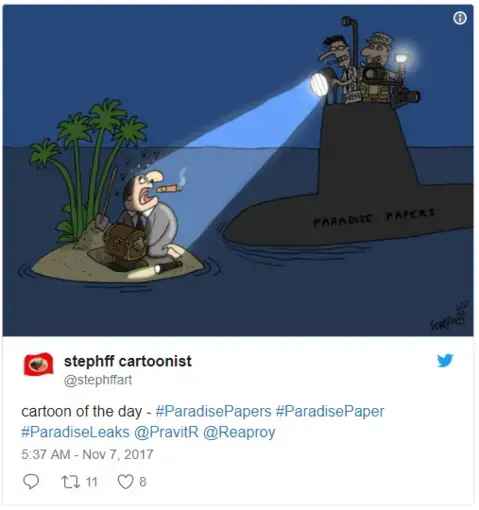

1. Summarize each of the following political cartoons in your own words:

It's unlikely that any private citizen is going to sit down and read 13.4 million files, no matter how significant their value. As such, it is the job of the investigative reporters involved to mine that data for digestible, engaging stories that the public needs and wants to hear.

2. Explore the Paradise Papers investigation on the Pulitzer Center and ICIJ websites. Make a list of the different ways the ICIJ has found to tell this story.

3. In small groups, compare your lists. Consider:

- For each item on your list, who do you think the target audience is?

- What do you think are the most effective ways in which the stories of the Paradise Papers have been told thus far?

- Can you identify any audience(s) these stories are unlikely to reach as a result of the ways it is currently being told?

- What additional ways would it be possible to tell these stories?

- What impacts have the Paradise Papers had already, and what further impact can you foresee?

4. Each group should share their main takeaway(s) from their conversation with the class.

Extension Activity:

1. Building on your final discussion, identify a target audience that you think should know about the Paradise Papers investigation. Create a resource that summarizes the following in a way that will resonate with your target audience:

- What are the Paradise Papers?

- Why are they important?

- How did journalists investigate the story?

You can create a video, infographic, lesson plan, or any other resource. You may alternatively plan a large-scale resource (for example, a museum installation or a play) that you describe in detail but do not execute.

2. Present your resource to the class. Following your presentation, discuss the strengths, weaknesses, and possible impact of such a resource.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.7

Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse media and formats, including visually and quantitatively, as well as in words.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.W.2

Write informative/explanatory texts to examine and convey complex ideas and information clearly and accurately through the effective selection, organization, and analysis of content.

Examples of tips you can write in students’ envelopes include:

- The company that supplies your school cafeteria with vegetables has continued selling spinach that might be contaminated with E. coli bacteria despite a recent recall.

- The recycling at the biggest company in your town does not actually get recycled at all; instead, the company sends it off to the landfill while claiming state tax benefits on the recycling equipment and process costs they don’t, in reality, have.

- Maintenance staff at your school is being paid less than minimum wage.

Ensure that students know these are hypothetical examples and not real tips.

To better understand the purpose/impact of this type of reporting and to contextualize the Paradise Papers, it may be useful for students to have some background in U.S. investigative journalism history. To assign as homework or review as a class, this list of noteworthy moments for investigative reporting in the U.S. from the Brookings Institution is one starting place.

Introducing Resource 1: “The True Story Behind the Secret Nine-Month Paradise Papers Investigation”

Depending on time constraints, students can be assigned to watch this video before class, or an excerpt (i.e. 0:00-12:50) can be screened.

Please help us understand your needs better by filling out this brief survey!

REPORTING FEATURED IN THIS LESSON PLAN

Snax Haven – How to Hide the Secret Sauce Recipe and Save Millions

Paradise Papers

ICIJ's global investigation that reveals the offshore activities of some of the world’s most...

Paradise Papers: The Influencers

- Close Menu Search

- Tips and Lessons

- Classroom in a Box

- Journalism Training

- News Literacy Principles

- Media Literacy Articles

- Curriculum and Lessons

- Q and A with the Pros

SchoolJournalism.org

Journalism lessons.

Some of the best, award-winning journalism teachers and professors from across the country have contributed their lessons and curriculum to SchoolJournalism.org.

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom in a Box Series

- Training Modules

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

7 Journalism Extracurriculars for High Schoolers

What’s covered:, extracurricular activities for aspiring journalism majors, how do extracurriculars impact your college chances.

If you’re a high school student who plans to go into journalism, there are many opportunities available for you to pursue your interest. Obvious choices include joining your school’s newspaper or volunteering at a local news organization. But what if your school doesn’t have a newspaper or your local news team isn’t interested in help from a high school student?

Niche interests like journalism might seem difficult to pursue at first glance, but rest assured, there are many extracurricular activities out there that will improve your skills and increase your experience to help prepare you for your future journalism pursuits.

Some of these opportunities are facilitated by your school, while others are independently run. To learn more about how to explore the field of journalism, read on.

1. Student Newspaper

This is the most obvious option for students who are interested in journalism. Many schools already have a school newspaper, and getting involved is usually as simple as talking to the editor or faculty advisor.

You may have to start in an entry-level role taking assigned stories, but you can think of this as good training for an actual career in journalism, where you’ll likely have a similar start. Over time you may be able to work towards a leadership position or at least start to source and pitch your own stories.

If your school doesn’t have a student newspaper, you might want to start one. Begin by finding a group of interested and skilled students. Choose a teacher as a potential faculty advisor. This should be someone who has taught you in the past and who has some kind of expertise in writing or publishing. Meet with that teacher to request advice and guidance.

Once you have the ball rolling, create a proposal for your school. Include any operating costs and details about how you plan to raise the funds needed to run the paper. While printing actual hard copies can be the most expensive part of operations, publishing online is a less expensive alternative that is becoming quite legitimate in the Information Age. Starting a student newspaper will allow you to pursue your interests while demonstrating your initiative and leadership skills.

2. Other Clubs

If you aren’t interested in writing for your school’s newspaper for whatever reason, bear in mind that there are other school clubs and organizations that can help you improve your journalism skills.

If you’re interested in broadcast journalism, you should consider organizations that emphasize technology and communications methods, as well as organizations that emphasize verbal presentation. These include:

- Radio Station

- Debate Club

- Model United Nations

If you have an interest in print journalism, you should consider organizations that emphasize writing skills and effective formatting. These include:

- Writer’s Group/Workshop

- Literary Magazine

- Poetry Club

- Quill and Scroll

- Journalism Club

- School Yearbook

- School Magazine

3. Volunteer Your Writing Skills

Any organization that produces written communications needs strong writers. Consider reaching out to local organizations that could use volunteers. These include:

- Animal shelters

- Food pantries

- Retirement homes

- Community centers

- Youth groups

- Your local church

These types of organizations generally welcome any publicity they can get, so they would likely be very happy to have your help. Offer to write a newsletter outlining recent changes or developments in the organization. Ask leaders for stories they would like to see highlighted or propose your own if you’re familiar with the organization.

Volunteering your writing services is a good way to build a portfolio. As you progress to more professional roles, you’ll be asked for samples of your work. Be sure to keep copies of everything you’ve written, especially when it has been formatted and printed as part of any professional copy.

Additionally, you could be a communications, social media, or public relations manager for any club on your school’s campus. Student government, service leagues, and activist organizations are often looking for help with outreach.

4. Enter a Writing Contest

There is a huge variety of writing contests available to high school students. If you want to gain some recognition or to win cash or scholarship prizes, entering one of these contests would be a good choice for you. Some writing contests even focus explicitly on journalistic writing.

For a complete list of some of the most respected writing contests open to high schoolers, check out The CollegeVine Ultimate Guide to High School Writing Contests .

5. Get Published

Similarly, you can submit your work to be published in existing journals or magazines. Many online news sites rely on submissions from freelance writers. Even if they don’t specifically seek work from high school students, they won’t necessarily know your age when you submit a piece of writing.

At some publications, you will only get one chance to be considered seriously. If you submit something that is not polished, they are unlikely to take your submissions seriously in the future. Proofread carefully and get constructive criticism from a teacher or peer before sending in your work.

Some online publications that might be good to start with include:

- jGirls+ Magazine (focus on Jewish girls)

- iGeneration Youth Magazine

- Affinity Magazine

- Cripple Media (focus on disabled communities)

- Ms. Magazine (focus on intersectional feminism)

- GeneseeSun.com (focus on upstate New York)

- BRIDGE: The Blufton University Literary Journal (focus on literature)

- Adolescent (focus on content creation)

Be sure to select carefully and keep in mind that publications that pay for submissions are likely to be more competitive and to hold you to higher standards overall. Consider submitting to smaller local or regional publications first.

6. Enroll in a Summer Program

Academic and extracurricular summer programs are becoming a more and more common way to pass the summer break. Many of these programs exist just for students interested in pursuing journalism. In these programs, you can expect to develop your journalistic skills, build important connections, and gain a better understanding of the field of journalism.

Some of the most renowned programs include:

1. National Student Leadership Conference’s Journalism, Film & Media Arts Summer Program

Location: Washington, D.C.

Duration: 9 days (sessions available in mid-June and early July)

Cost: $3,895

During this program, students travel to Washington, D.C., where they have the opportunity to explore the inner workings of important media outlets. Additionally, students get familiar with professional studio equipment and the methods of high-level journalism. Two tracks are offered—Newswriting & Investigative Reporting and Broadcast Journalism.

2. International Summer Schools (ISSOS) Journalism Programs

Location: Cambridge University

Duration: 3 weeks (July 12 – August 2, 2023)

Cost: $8,616 – $11,114

Through seminars and practical assignments, students attending ISSOS programs learn research skills, writing skills, and formatting skills. Students choose one Academic course and one Elective course, then supplement their learning through hands-on experiences outside of the classroom.

3. Cronkite Institute for High School Journalism

Location: Arizona State University Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication (Phoenix, AZ)

Duration: 1 week (June 11-17, 2023)

Camp Cronkite offers students three different tracks to pursue their journalistic interests—digital journalism, broadcast journalism, and sports media. Through the camp, students get exposed to the various elements and voices that go into the journalistic craft. 25-30 students are selected for the program each year.

4. AAJA JCamp Summer Program

Duration: 6 days

JCamp is a multicultural journalism program. The program focuses on the value of cross-cultural communication skills, the fundamentals of leadership, the importance of diversity in the newsroom and media, journalistic ethics, and the value of networking and career mapping.