- Writing Center

- Current Students

- Online Only Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Parents & Family

- Alumni & Friends

- Community & Business

- Student Life

- Video Introduction

- Become a Writing Assistant

- All Writers

- Graduate Students

- ELL Students

- Campus and Community

- Testimonials

- Encouraging Writing Center Use

- Incentives and Requirements

- Open Educational Resources

- How We Help

- Get to Know Us

- Conversation Partners Program

- Workshop Series

- Professors Talk Writing

- Computer Lab

- Starting a Writing Center

- A Note to Instructors

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review

- Research Proposal

- Argument Essay

- Rhetorical Analysis

How to Write Meaningful Peer Response Praise

Praise is an important element of peer and teacher feedback—it can, to quote Donald Daiker, “lift the hearts, as well as the pens” of student authors—but substantive praise is one of the most challenging modes of feedback to compose (112). How can writing instructors move student responders beyond standard comments such as “Great paper!” or “I liked it” or “Good details”? This chapter is a guide for students in composition classes, and aims to help them understand the importance of giving and receiving detailed, conversational praise; it presents scenarios for conceptualizing how to write praise, provides sample student writing excerpts that invite students to practice writing praise, offers and analyzes examples of different types of student-authored praise comments, and provides an array of approaches to writing praise comments.

In some first year writing classes, peer feedback days parallel the char- acters’ journey into the Appalachian caves in Neil Marshall’s horror film The Descent .* A group of female friends goes on an annual thrill-seeking adventure, climbing their way through a complex, uncharted cave, only to encounter some ferocious monsters, as well as their own inner demons. Vivian Sobchack characterizes the chaos depicted in the film this way: “Eventually trapped within the cave system by a rock slide, the six women become separated, each person or little group fitfully lit through different means to allow us to see their struggles in stroboscopic glimpses—and then often to wish we hadn’t” (41).

Comparing the film to a first year writing class, the “descent” into peer feedback can sometimes leave all parties lost and helpless: we teachers bemoan the ragged and inconsistent quality of some peer comments, and you, who often complain only to us when your peers do a slack job writing comments on your work. Too often, all of us “wish we hadn’t” wasted time at all doing peer response.

A few years ago, I had a student (we’ll call him Ray) whose peer response routine involved shuffling through his peers’ papers—which were to be responded to as homework—and writing generic comments quickly at the start of class. “Good opening,” he would write, then next to each paragraph, “Give examples,” and at the bottom, “I like the ending, but maybe expand.” I began to realize all his comments were the same, and a student who was in his group confirmed that he never read his partners’ essays before writing feedback.

Now, that’s a descent .

Why go into the cave at all, we might ask, especially if even one of your peers approaches the task with such disregard? Or, what about the fact that some writers ignore your feedback anyway, preferring to only pay attention to the instructor’s comments, because “they are the one giving the grade”? Not too long ago, Fred, a student taking his second composition course with me, told his group as he handed his peer feedback to them: “You can ignore these; I’m just trying to get plusses on my feedback.” (I assign grades of Plus, Check, or Check Minus on feedback, with some brief commentary about how responders could improve next time.) I was struck by Fred’s admission, and his willingness to participate in writing peer responses that he didn’t fully stand behind.

The psychology going on in peer groups reminds me of some of the conclusions I drew working on my dissertation on peer response while a graduate student at Florida State University. I collected and studied my students’ peer feedback and their thoughts about the feedback they gave/ received. I noticed that:

- Students placed greater value in professors’ feedback vs. peers’, usually ignoring peer responses unless they were forced to use them in revisions;

- Students often felt poorly qualified to write meaningful responses, since they saw themselves as merely adequate, “not good enough to tell someone else how to write;”

- Students were often reluctant to write questions, which they viewed as critical, because they did not want to be perceived as “judging” their peers’ experiences, thoughts, or feelings;

Students would often judge their peers’ writing based on what they thought a teacher would want, rather than their own criteria for what makes writing good; and

Students initially tended to comment on things that were easier to “fix” like grammar or spelling mistakes, and paragraph size.

You may see yourself in one or more of these attitudes, and you may have received or given feedback similarly to Ray or Fred. Such attitudes and approaches are natural: given how sensitive the act of sharing an essay can be, these attitudes and others create a complex dynamic in small groups, leading some of us to prefer to avoid peer feedback, especially if we have not established trust with our group. As a result of these ways of thinking, some writers become frustrated working in small groups, because they don’t put much faith in the process or in the weak comments they anticipate receiving.

As a way of free falling right into this metaphorical dark cave, let’s jumpstart your class discussion of peer response strategies. I recognize that there are additional types of feedback, such as asking questions, giving advice, and editing or correcting errors, but this essay is going to focus on one important type of feedback.

How to Write Meaningful Praise

Think of a favorite food (I’m sure you have many, but pick one for now.). Why do you like it? What can you say about that food that conveys why that food is enjoyable to you? It is not enough, really, to say that you like it “because it tastes good.” In this sense, good just becomes an empty word that doesn’t really say anything.

I like pepperoni pizza. My two favorite places are Angelone’s in Port- land, Maine, and Burke Street Pizza in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. What I really like is how, on theirs, the slices of pepperoni curl up just a little and get crispy around the edges, leaving a tiny bit of oil residue in- side. I also like how their pepperoni slices can easily be bitten into, rather than the big round slabs of pepperoni that some pizzerias use, which sort of slide off whole when you chomp into them, pulling along large segments of cheese. Sure, there are plenty of places that offer adequate pizza, but only rare places like these make pepperoni pizzas that I really like.

It is easy (and somewhat distracting!) to come up with details to de- scribe the foods we like; but, what about writing we like? Why do we like it? What does it mean to “like” an opening sentence, an image, an insight? Since you don’t want to be that student who just jots generic comments down the margins in a hurry, like Ray made a habit of doing, I encourage your class, before workshops even begin, to do an inventory of what makes you like (or dislike) certain features of writing. Not just what makes writing “good,” but what makes writing really work for us, as individual readers.

Are you a reader who likes detail in the form of facts and data—such as a newspaper article about Dustin Pedroia’s injury, one that provides statistics showing how well the Red Sox play when he has been in the line-up compared to their win-loss record without him? Or are you a reader who likes to “discern” by reading in between the lines what an author might mean? Do you like to learn about new things, places, people, ideas, when you read, or do you prefer to read about that which is familiar? Do you like writing that makes you feel sadness or frustration, or do you prefer to read stories that look on the brighter side? It is good to know these things about yourself, as you approach any new text.

Now consider this: Is it even possible to like the writing that you and your peers have to do for classes? Not always. But, I would argue that you don’t have to like the academic writing your peers share with you (i.e., enjoy it the way I enjoy most any article about the Boston Red Sox) in order to praise what’s working for you as a reader.

Meaningful praise, then, is feedback that recognizes something that is working for you as a reader, that gives you an opportunity to have a dialogue with the author, and that expresses some sort of appreciation for the work the writer has done, or for the writer herself.

I remember when my student who wrote about his football experiences included a detail about coaches making him run up and down the bleachers with garbage bags wrapped tightly around his torso so he could get “in condition” for the upcoming game (I believe this is not allowed anymore). He did not use extensive description or need to. Through one well-chosen detail, he was able to illustrate what the players had to do and reveal some of the complexities of being a competitive athlete: his detail allowed the reader to imagine the exhaustion, and to question the methods the coaches used to get some players into shape. Praising the student’s use of detail had to involve more than just telling him “nice detail.” It meant explaining, as succinctly as I could fit in the margin, what made it work, for me as one reader: “A nice detail. You’ve already got me appreciating the physical and emotional stress an elite athlete experiences. It must have been draining. How do you feel now about the coaches’ methods?” Here is an alternative praise comment, from a peer who likes the passage because he can relate to it: “Good description. Our coaches used to do this too. I like how you make people who don’t know what it’s like understand what we go through to compete.”

Practice Session 1

Let’s practice writing praise in response to an actual sample of student writing, the beginning of a personal exploration by Lili Velez. As you read the following excerpt, consider what praise you could write:

Examinations Outside the Classroom

We panic, we pack, we get to college, and then panic again, moaning, “I wish I had known I’d need this!” “This” could be any- thing from that extra pillow to the answers to a high school test on Hamlet , or it might be something more abstract, like how to deal with issues we never thought we would encounter outside a classroom. For example, when a philosophy professor asks us to examine what is evil and what is good, that’s okay; we’re getting graded on it. But do we ask such questions in the cafeteria? In the dormitory? At home? Who needs to ponder academic questions outside of class? It’s an invasion of our private lives. I thought so until a question followed me home and shook up my ideas on what belonged in the classroom and what I should never be without.

It was English 102, in small group discussion of my friend Donna’s paper, which was about whether fighting was a natural tendency, as it is in other animals that live in groups. (337)

It would be easy enough to write next to Lili’s first paragraph “good opening.” It would be simple enough to say that the opening is “descriptive” or “captivating.” But, if you like the opening of this essay, what really causes your positive reaction? Even just as a draft, why does this opening work for you, as a reader? Take a moment to write two or three sentences describing what it is you like about Lili’s writing so far, and imagine you are writing these words directly to her in a conversation.

Is it the word choice? The arrangement of sentences? Her use of detail (the pillow, Hamlet )? Does it have something to do with the voice or tone? The way she uses questions? It could be any or all of these things, or something else altogether. I liked the commas and repetition in the first sentence, which create a sense of tension in the writing. (I am the kind of reader who likes some tension in what I read.) I also liked the feeling of momentum. Even just a little bit into the second paragraph, I am curious to hear more about what happened in her small group and the discussion about Donna’s paper. As Keith Hjortshoj describes in The Transition to College Writing :

Beginnings are points of departure, when readers expect to learn what this writing is about and the general direction it will take. Even if these beginnings do not explicitly map the routes the writing will travel, they tell us where this journey will start, point us in a certain direction, and provide some bearings for the next move. (115)

Lili is trying to do just that: engage the reader, point us in a specific direction, and pose a central question that will guide the exploration forward.

Elaine Mamon, Lili’s instructor in the class, praised Lili for her courage to tackle a challenging topic and for making the reader “feel like getting into the conversation” (Velez 340).

Practice Session 2

When writing meaningful praise, you might consider using a technique associated with rhetorician Donald Murray, who was known for writing his praise to students using this format: “I like the way you…” (qtd. in Daiker 111). By including some praise written this way, you help writers enhance their audience awareness. As you read the following excerpt, the opening of a personal essay my student Nick wrote about declining wildlife in Pennsylvania, write 2–3 praise comments in Murray’s “I like the way you…” format:

Where the Wild Things Roamed

And there we found ourselves, on my hike in the woods with my dog Loki, his eyes fixed upon a herd of deer who stared back at him with the same intense interest. You could see it stir within them, the ancient war between their kind, Loki likely thinking “Must chase! Must bite!” though he probably does not know why, and the deer screaming in their minds, “The wolf! The wolf!” despite the ironic fact that these deer have never seen a wolf. For there are no wolves in these woods, nor in all of Pennsylvania. Gone are the days of wolves and mountain lions prowling through these woods giving the deer something to truly fear rather than this would-be predator at the end of my leash.

And here I am looking at these deer and wondering, “How are you all that’s left?” (Brewster 1)

After completing your praise comments, I recommend talking with others in class about what you praised, how you worded each comment, and what it was like writing responses this way.

Donald Daiker believes that writers become less apprehensive when they “experience success” and that “genuine praise can lift the hearts, and the pens, of the writers who sit in our classrooms” (106, 112). After receiving fifteen sets of feedback from his classmates throughout the semester, which all had to include several praise comments, Nick explained his emerging confidence: “I ended up deciding to let my creativity loose despite how un- comfortable it made me. I ended up finding myself greatly enjoying some of my later works. The more confident I became in my writings the more I experimented with my creativity.” In one of his final peer comments on a classmate’s meta-essay, Nick acknowledges the role positive peer feedback had played in their mutual development: “Great point and I agree. We helped one another write about more personal feelings and dilemmas.”

Examples of Peer Response Praise

Let’s look at several other praise comments Nick writes on his classmates’ essays. For context, most of the papers students wrote in this class revolved around animals, or writing, and sometimes both:

- Repeating the questions was an effective follow-up to your intro sentence

- Nice allusion. Very creative way of describing your writings.

- Notice how Nick refers to specific choices the writer had made. Here are some comments Nick writes on Carolyn’s essay about six cats she has owned throughout her life. Sometimes, Nick praises Carolyn for the choices she makes as a writer, and sometimes he praises her personally, but all of them are conversational:

- Good details that add to each cat’s character

- Interesting how everyone ended up getting their “own” cat

- The font change is a good touch [Carolyn had switched fonts for a passage that recreated a letter she would have written as a child to her cat who had passed away]

- Recognizing how you’ve changed over time and looking back on your younger self is such a human thing to do and extremely relatable. I think we’ve all been there.

- Great imagery and comical, picturing this level of organization from a child

- LOL! Nice touch and some comic relief after the passing of Chester

Occasionally, Nick writes what Rick Straub and Ronald Lunsford refer to as combination comments, wherein a praise comment is joined with a question or tentative advice. For example, in response to Jordan’s essay about his dog Quinn, Nick writes:

- Good descriptions [of Quinn]. Maybe could add more? Hair type, face, size?

On Rose’s essay, which analyzes the effects of a social media influencer who hoards animals (particularly rats and reptiles), Nick combines praise, analysis, and a rhetorical question:

- Good point. It does certainly appear we care about some animals more than others. Would people care more if it was a room full of puppies, for example?

Notice how in responding to Rose’s argument, Nick has joined the conversation as a reader. The best peer feedback does not just inflate the writer’s ego but keeps the conversation about the writing, and about the topic, moving forward. The praise you receive can help you understand what goes on in your readers’ minds, and better shape your writing for an audience.

In his article “Responding—Really Responding—To Other Students’ Writing,” Straub encourages you to “Challenge yourself to write as many praise comments as criticisms. When you praise, praise well. Sincerity and specificity are everything when it comes to a compliment” (192). Nick includes a good deal of praise in his sets of feedback, and his comments are specific and sincere.

Final Advice and Thoughts

You may try to write your peer response using different color pens—for example, green for praise, orange for combination comments, or green to praise stylistic techniques and blue to praise ideas. Also, give yourself enough space and time to write conversational praise. As an example, Andrea writes in the space next to Jordan’s title “The Unwritten”: I really like your title—it fits well with the theme running through about things we must accept in life that are too complicated to be written in a rulebook. Since you only mention writing a couple times in the piece, it’s nice and subtle. In the left margin of Carolyn’s essay “Alone,” Andrea writes, I like the repetition of the two phrases “ but I am alone” and “my cat who is on my chest.” Even though there are multiple metaphors in this piece, keeping the repetition going grounds the reader to where the narrator is and really creates the feeling of what it’s like when your body isn’t moving but your brain is going a million miles an hour. Andrea writes small and can fit this comment in the top margin, but you may want to write lengthier praise on the back of the page or in an endnote/letter to the author. Although it takes a bit more time to write such conversational praise, compared to “Good title,” or “I like the repetition,” Andrea’s comments say so much more to Jordan and Carolyn. They are examples of what Donald Daiker would describe as “genuine praise” (112).

Being a peer responder is not just about being a good one or a bad one, it is, just as it is with your writing, about your investment in joining a real conversation with others. When combined with additional types of peer feedback that you will practice—such as asking questions, giving advice for revision, critiquing an argument’s shortcomings, and/or making corrections—praising well and with sincerity will help your classmates improve their writing and enhance their desire to write with a specific audience in mind. Together, you will avoid “the descent” and develop as writers and readers, and maybe even enjoy the journey together.

Works Cited

Teacher resources for "how to write meaningful peer response praise" by ron depeter, introduction for teachers.

Instructors could assign this essay in a first-year or upper-level writing course or workshop, during the early part of a semester when students are practicing peer feedback. The essay is in some sense an indirect sequel to Straub’s “Response—Really Responding—To Other Students’ Writing,” looking more in-depth at one specific mode of peer response. It is recommended that students have opportunities to practice writing feedback— perhaps on one or more sample essays that the instructor has collected from previous students. Ideally, students should practice writing each mode of commentary (for example, 1–2 sessions writing praise, 1–2 sessions writing questions/advice, 1–2 sessions combining several modes) before diving into small group or whole class workshops. Ideally, the instructor can give some feedback or grades on the practice feedback, letting the students know how they are doing and how they might improve (e.g., write more comments, make comments more specific, etc.). After each peer feedback practice session, and in the “real” workshops with classmates, students can reflect in their journal/class discussion on how they feel they are coming along as responders, as well as how they feel about the comments received. Such meta-writings are essential threads that facilitate the students’ growth as readers and responders.

Discussion Questions

- Do any of the attitudes about peer response that DePeter discusses in the beginning of his essay apply to you (e.g., not wanting to “judge” others or regarding a teacher’s feedback as more important than peers’)? Where do you imagine these attitudes come from?

- How do you think Nick (or any peer) would feel hearing the praise comments written in the Donald Murray style of “I like the way you…”? What effect would such praise have on the writer, com- pared to just seeing “Good” next to a passage?

- Do you feel there is a difference between what you feel is “good writing,” and that which teachers have identified as “good?” If so, what accounts for these different expectations? What is your definition of “good writing?”

Can you think of ways that Nick or Andrea’s peer response praise could be even sharper, or more helpful to an author?

Discuss experiences you have had in other classes sharing peer response. Have they been a metaphorical “Descent,” or enjoyable journeys? What made your peer response sessions in the past work, or not work?

This essay was written by Ron DePeter and published as a chapter in Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing , Volume 3, a peer-reviewed open textbook series for the writing classroom. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) .

Contact Info

Kennesaw Campus 1000 Chastain Road Kennesaw, GA 30144

Marietta Campus 1100 South Marietta Pkwy Marietta, GA 30060

Campus Maps

Phone 470-KSU-INFO (470-578-4636)

kennesaw.edu/info

Media Resources

Resources For

Related Links

- Financial Aid

- Degrees, Majors & Programs

- Job Opportunities

- Campus Security

- Global Education

- Sustainability

- Accessibility

470-KSU-INFO (470-578-4636)

© 2024 Kennesaw State University. All Rights Reserved.

- Privacy Statement

- Accreditation

- Emergency Information

- Report a Concern

- Open Records

- Human Trafficking Notice

Writing Center

Peer response.

- meets the assignment requirements

- has a clear purpose or goal

- has a clear thesis or main point

- stays on topic

- makes a strong argument or clearly presents information

- offers persuasive evidence or relevant information

- has clear organization

- uses a style suitable for the audience

- is formatted correctly

- accept criticism and consider the responder’s comments. Responders know whether or not they understand something. If a responder says, “I don’t get it,” the writer should assume the problem might be the in the work itself.

- provide the responder with all the information needed to give helpful feedback. It’s difficult to comment on an assignment if it’s unclear what the assignment entailed.

- maintain ownership of the work. The work is the writer’s creation. What happens to it is the writer’s decision. While the writer should consider the responder’s comments respectfully, in the end, the writer must choose what is best.

- Pair up with a partner. Identify one person to be the responder and the other to be the writer.

- The writer reads his or her own work out loud or delivers the presentation using slides, an outline or notes. The responder writes down his or her thoughts on a separate piece of paper without speaking. The responder should focus on high-order concerns such as the thesis, organization, the logic of the argument, and the tone of the paper. Grammar and small errors can wait. (Don’t skip the reading aloud, even if it makes you uncomfortable: saying your own words out loud can help you identify problems you’d miss when reading silently.)

- When the writer has finished, the responder gets 1-2 minutes to state his or her impressions out loud. The writer should not answer objections, explain, or ask questions, but simply listen attentively to the responder’s reactions, comments, and concerns. The responder should be tactful but honest and specific. The responder can also offer praise, as well as criticism.

- Now, the writer can speak. The pair should discuss the feedback and answer any questions or point out specific parts of the essay that were a problem. This cooperative period should last anywhere from 1-5 minutes, or longer if more discussion is needed.

- The writer and the responder should switch roles. Repeat steps 2-4.

- Once both partners have received feedback, they trade places. Both should read each other’s work silently to themselves looking for low-order concerns like spelling, punctuation, word choice, etc. If one partner notices a recurring or large problem in the other’s work (such as sentence fragments, poorly designed slides, or a pattern of misplaced commas), he or she should mention it and make suggestions about how to fix it.

The Four Be’s

Also recommended for you:.

Peer Response (Composition)

Glossary of Grammatical and Rhetorical Terms

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

In composition studies , peer response is a form of collaborative learning in which writers meet (usually in small groups, either face-to-face or online) to respond to one another's work. Also called peer review and peer feedback . In Steps to Writing Well (2011), Jean Wyrick summarizes the nature and purpose of peer response in an academic setting: "By offering reactions, suggestions, and questions (not to mention moral support), your classroom colleagues may become some of your best writing teachers."

The pedagogy of student collaboration and peer response has been an established field in composition studies since the late 1970s.

See the observations below. Also see:

- Collaborative Writing

- Audience Analysis

- Audience Analysis Checklist

- Holistic Grading

- Implied Audience

- Online Journals for Composition Instructors

- Writing Center

- Writing Portfolio

- Writing Process

Observations

- "The teacherless writing class . . . tries to take you out of darkness and silence. It is a class of seven to twelve people. It meets at least once a week. Everyone reads everyone else's writing. Everyone tries to give each writer a sense of how his words were experienced. The goal is for the writer to come as close as possible to being able to see and experience his own words through seven or more people. That's all." (Peter Elbow, Writing Without Teachers . Oxford University Press, 1973; rev. ed. 1998)

- "Writing collaboratively has all the characteristics that theorists of cognitive development maintain are essential for the intellectual commitments of adulthood: The experience is personal. The response groups promote intellectual risk-taking within a community of support. They allow students to focus on issues that invite the application of academic knowledge to significant human problems. Thinking and writing are grounded in discussion and debate. Reading and responding to peers' writing asks for interpersonal and personal resolution of multiple frames of reference. In this sense, collaborative writing courses at all levels provide an essential opportunity to practice becoming members of an intellectual, adult community." (Karen I. Spear, Peer Response Groups in Action: Writing Together in Secondary Schools . Boynton/Cook, 1993)

- Peer Review Guidelines for the Reviewer "If you are the reviewer, remember that the writer has spent a long time on this work and is looking to you for constructive help, not negative comments. . . . In that spirit, offer suggestions about how to revise some of the awkward places, rather than merely listing them. Instead of saying 'This opener doesn't work!' indicate why it doesn't work and offer possible alternatives. . . . "It is also important that you try to read the piece from the point of view of the intended audience. Do not try to reformulate a technical report into a novel or vice versa. . . . "As you read, make no comments to the author--save them for later. If you need to ask the writer for clarification of the prose, that is likely a flaw in the writing and needs to be noted for discussion after you have finished reading the entire piece." (Kristin R. Woolever, About Writing: A Rhetoric for Advanced Writers . Wadsworth, 1991)

- Students gain confidence, perspective, and critical thinking skills from being able to read texts by peers on similar tasks.

- Students get more feedback on their writing than they could from the teacher alone.

- Students get feedback from a more diverse audience bringing multiple perspectives.

- Students receive feedback from nonexpert readers on ways in which their texts are unclear as to ideas and language.

- Peer review activities build a sense of classroom community.

- Benefits and Pitfalls of Peer Response "[A] number of practical benefits of peer response for L2 [ second-language ] writers have been suggested by various authors: On the other hand, researchers, teachers, and student writers themselves have identified potential and actual problems with peer response. The most prominent complaints are that student writers do not know what to look for in their peers' writing and do not give specific, helpful feedback, that they are either too harsh or too complimentary in making comments, and that peer feedback activities take up too much classroom time (or the corollary complaint that not enough time is allotted by teachers and the students feel rushed)." (Dana Ferris, Response to Student Writing: Implications for Second Language Students . Lawrence Erlbaum, 2003)

Also Known As: peer feedback, peer review, collaboration, peer criticism, peer evaluation, peer critique

- Holistic Grading (Composition)

- A Writing Portfolio Can Help You Perfect Your Writing Skills

- What Is an Annotated Bibliography?

- reader-based prose

- Feedback in Communication Studies

- What Is a Critique in Composition?

- The Whys and How-tos for Group Writing in All Content Areas

- Audience Analysis in Speech and Composition

- revision (composition)

- Self-Evaluation of Essays

- Prewriting for Composition

- Focusing in Composition

- What Is Contrastive Rhetoric?

- Definition and Examples of Composition-Rhetoric

- The Drafting Stage of the Writing Process

Tips for Effective Peer Response

Peer response, done well, can greatly improve the quality of your writing in your final draft. Many people confuse peer response with editing or proofreading. Peer response is not just proofreading--in fact, proofreading is only one small part of the peer response (and for some projects proofreading doesn’t come into play at all). Peer response is the process of responding to writing at macro and micro levels and in ways that offer helpful, constructive feedback.

General Tips For Both Writers and Responders

As a peer, you are a well-qualified person to read and respond to your peer’s drafts. You’ve been in the class, you know the assignment, you’re a thinking reader. Providing the writer feedback on what you thought as you read the draft is helpful and important. You are not expected to look at it with the eye of an instructor nor do you need special training to give your opinion.

Think about the assignment and review the grading criteria. Of course, you and all of your peers want to get the highest grade possible. You can help each other with this goal by closely reviewing the grading criteria that will be used to evaluate the finished paper. Does the work you’re responding to fit the parameters of the assignment? Does it include all the required parts of the assignment? If you are concerned that the paper is missing an assignment element or does not fully answer a question in the prompt, be sure to express your concerns to your classmate and offer suggestions.

Specific Tips For Writers

Tell your peer responder what you want feedback on specifically. If you know you strugglewith a particular element (integrating tables, for example), ask you peer to be sure to provide feedback about that.

- If possible, share your work with at least two different people. Each reader may have different perspectives that help you think about your writing in different ways.

- Use peer response to reflect on your own writing. By practicing response techniques with your peers, you may find that you have a different perspective on your own writing when you look at it again.

- Remember that not all advice given during peer response must be taken. Each responder may offer different advice that may be contradictory or may go against your own vision for your work. Consider the responses of your peers seriously but remember that the final choices for your writing rest with you.

Specific Tips For Responders

Comment on things that the writer does particularly well. We’re all human and no one wants to only get told what can be better. Also, by being shown what’s working really well, writers than have a model for how to improve other sections that may not be working so well. Be sure to highlight the parts of the paper that are effective and make that feedback part of your response. What did you like best about the paper? What did you think was most effective? Why?

- Comment on things that the writer could improve. Every written project, no matter how good, can always be improved. You absolutely want to offers suggestions to the writer on ways to revise their paper to make it better. The weakest peer responses are when someone says, “Looks good” or just writes “Nice” or “Great.”

- Frame all your feedback in constructive ways that offer suggestions. Note how you word your feedback and be sure to keep it friendly, constructive, and supportive. Remember to be encouraging and positive – peer response is for the benefit of all parties.

- If possible, provide both oral and written feedback. Using the comment feature in Google Drive or in Word, can also be helpful.

- Provide feedback on macro issues of organization and content. Is the main idea of the paper clear? Does it stay focused throughout? Is it arranged in a way that makes sense? Could the argument be organized in a more effective manner? Is enough and appropriate evidence provided to support the points being made?

- Provide feedback on micro issues of organization and content. This may require a second reading where you pay close attention to sentence-level issues such as word choice, sentence length, and tone.

- If appropriate, provide feedback on use of visuals. Tables and figures are important in many papers. Be sure to check that these are labeled correctly and referenced in-text.

- If you catch any misspellings, typos, punctuation or grammar errors, formatting mistakes, etc., be sure to let your classmate know. While peer response is more than proofreading, helping to catch these minor errors will also aid your classmate in turning in the most polished work possible.

Howe Writing Initiative ‧ Farmer School of Business ‧ Miami University

If you need this resource in another format for accessibility, please contact [email protected]

Readings on Writing

How to Write Meaningful Peer Response Praise

Ron depeter, chapter description.

Praise is an important element of peer and teacher feedback—it can, to quote Donald Daiker, “lift the hearts, as well as the pens” of student authors—but substantive praise is one of the most challenging modes of feedback to compose (112). How can writing instructors move student responders beyond standard comments such as “Great paper!” or “I liked it” or “Good details”? This chapter is a guide for students in composition classes, and aims to help them understand the importance of giving and receiving detailed, conversational praise; it presents scenarios for conceptualizing how to write praise, provides sample student writing excerpts that invite students to practice writing praise, offers and analyzes examples of different types of student-authored praise comments, and provides an array of approaches to writing praise comments.

Alternate Downloads:

You may also download this chapter from Parlor Press or WAC Clearinghouse.

Writing Spaces is published in partnership with Parlor Press and WAC Clearinghouse .

Unit 8: Academic Writing Resources

48 Peer Response Training

To be effective, peer response , also known as peer review or peer feedback , involves:

- the ability to identify what to comment on

- knowing what to look for in an essay and what to ignore

- knowing how to frame your comments effectively so the writer can understand what you mean and have an idea of how to revise.

The following information will help you better understand what to focus on and how to respond.

What should I comment on?

What you comment on for draft one will be different for draft two. In this class, you will conduct peer review for the first drafts of your essays. Below are some guidelines for things to focus on and things to ignore in the first drafts:

What makes comments effective?

Effective peer review comments are specific, clear, and tactful.

Academic Writing I Copyright © by UW-Madison ESL Program is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Sign Up for Mailing List

- Search Search

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Incorporating Peer Response

At mit, the use of students to respond to each other’s work in progress is long standing. robert valentine in a 1903 technology review article described undergraduates in engineering responding to the writing of their classmates. what valentine supported then is certainly true today: responding to the work of peers is essential in the process of learning to be a professional. nevertheless, resistance to incorporating peer response often comes from adherence to several myths that surround this practice:.

Myth: Student peer review is “the blind leading the blind” One question behind this myth is, “How can my students offer effective feedback when they have little control of their own writing or speaking?” The assumption here is that students need to be expert communicators and to share that expertise in the process of offering feedback. Well, one of the most powerful effects of peer review is the way it helps the reviewers articulate what they see or don’t see happening in another student’s text. That language of review then has the opportunity to loop back into the reviewer’s own writing or speaking, ultimately strengthening that work. In other words, through this process students are learning how to articulate and apply the criteria for successful writing.

Myth: Student peer review wastes class time Many students (and faculty) have unfortunately had the experience of peer review sessions that were unstructured and time consuming. However, if students are offered structured and focused opportunities to review each other’s work, time will be used efficiently. Often out-of-class preparation is key here: students might read drafts outside of class, and, even more important, writers/speakers will offer specific questions that they want answered in response to their drafts. In-class peer review does take time, particularly with large classes, but it is usually time well spent.

Myth: Student peer review will devolve into error correction Another common experience for students is to feel that in peer review their role is to be the “grammar police” and mark up peer’s drafts in the same manner that they’ve had drafts marked up by instructors. Certainly, if the focus for a particular peer-review session is on the mechanics of writing or editing, error correction might be appropriate. However, structure is again key here–students need specific focus and guidelines on how to respond, as well as models of effective response. Students will surely have access to each other’s work through the process of peer review, and that access might offer opportunities for plagiarism. However, students also have access outside of class, and combating plagiarism involves far more than limiting students’ opportunities to see what someone else’s draft paper or talk says (for more on plagiarism, see ). Instead, students need the opportunity to develop their ideas in the midst of a scholarly community, just as professional academics do. From this experience, students might have the opportunity to be inspired by someone else’s approach or argument or analysis, just as reading the literature in one’s field can offer inspiration for new ideas.

Myth: Students are too hard on each other and might be mean Once again, students offer peer review based on previous experiences and the guidelines (or lack thereof) under which they’re operating. By offering models, guidelines, and specific focus, instructors can easily discuss what separates constructive feedback from mean-spiritedness. Studies have shown, in fact, that students tend to offer many more positive comments to their peers than do instructors.

Myth: Students are too easy on each other and might validate poor work Without clear focus or guidelines, students can easily fall back on “Well, I liked it,” and nothing more as their response to a peer. But by engaging in structured and focused peer review, students will learn the language of response, and, in particular, learn from their instructors what experienced professionals will focus on and expect in the writing and speaking of other professional. Interestingly, the same studies that show that students are more positive in their response to student writing also show that students revise more extensively in response to positive comments.

No One Writes Alone: Peer Review in the Classroom

The value of peer response in ci subjects.

Why should you consider using peer response? Research has shown that peer response offers students many pedagogical benefits:

- Highlights the social dimension of writing and makes the audience that students are trying to persuade a tangible group rather than an imagined construction.

- Allows students to see other possibilities for developing the kind of writing they’re producing.

- Recasts response to student writing as a generative aid to idea development that’s common in all disciplines, rather than simply as evaluation and “correction.”

- Helps students to understand that critical feedback (both peer and instructor) is not merely personal and idiosyncratic, but stems from socially shared conventions of knowledge production and persuasion.

- Allows students practice in acting as an authority on those shared conventions—in identifying and articulating what they are and how they function. Thus, it makes implicit learning explicit.

- Gives students practice in the kinds of oral interaction around developing ideas, the kinds of intellectual give and take between scholars, that is common in all disciplines.

- Leads to deeper understanding and higher order learning.

How would it work into the already tight syllabus? Peer response can take a variety of forms:

- Students can respond to each others’ papers in groups of 3 or 4 students, inside or outside of class, with or without direct instructor supervision.

- Students can be prepared for responding with assignment-specific guidelines, which require student action and response (see examples).

- Students can work through a small number of papers collectively, in a whole-class workshop.

- Students can respond to each others’ writing through an online format, perhaps using the Forum function of Stellar, or through file sharing, such as through Google Docs.

When is the best time to incorporate peer response? Peer response can work at various stages of the process:

- When the paper is returned, before a required revision.

- Between stages of a longer research paper.

- With shorter response papers, focused on developing the ideas more fully, perhaps into longer assignments.

- A few days before a paper is due, with a requirement that students share a complete draft.

Examples of Poor Peer Responses

Peer Response is a two way street. You will be giving peer response, and you will be receiving it. The more you do peer response, the more you see how helpful it is to get feedback from your readers as you work on a writing piece. As you review peer responses you have received, remember that you are the ultimate "author," and you decide what to use or not use from this feedback.

Free Web Counter (Since 1/12/16)

Facilitating Effective Peer Review Sessions

Main navigation.

PWR is committed to the use of small-group writing workshops. While some students doubt the value of peer group work, when well executed these groups can be both effective and enjoyable. While some instructors keep students in the same small groups all quarter, other instructors create new student groups for every assignment. Both strategies have merit.

Peer Review Group Suggestions

- Pay attention to the way you present the concept of peer review to your students. Explain clearly the rationale for doing this activity and demonstrate your commitment to it.

- Make the work count. You may assign points for it as a part of your class activities and informal writing component of your grade; remember that you need to be transparent in your evaluation criteria for anything that you are “grading,” including group work.

- Prepare clear and specific Peer Response Guideline Sheets for each peer response session.

- In a remote learning context, consider creating peer review groups by student time zone, especially if the peer review groups are meeting outside of class time.

- Spend some time with each group. Take notes on the activity, on how well the group is working; who is contributing strong, focused responses; who needs to improve, etc.

- At the end of the session, remind the students to turn in all their peer responses with their revised essays.

- Take time to respond briefly but cogently to each peer response, noting areas of strength and weakness and ways in which the responder can offer more explicit and helpful advice.

- Take time in the next class to refer to some of the most useful comments made in peer response and specify why they are more helpful than others.

- Be patient. Experienced instructors say that getting the groups working well together takes several weeks; with persistence and encouragement from you, they will get there.

- Consider changing the peer response structure. For instance, have the peer groups act as the editorial board of a journal.

See also some examples of peer review sheets from our PWR Canvas Archive

Engaging in Peer Review

There are times when we write in solitary and intend to keep our words private. However, in many cases, we use writing as a way of communicating. We send messages, present and explain ideas, share information, and make arguments. One way to improve the effectiveness of this written communication is through peer-review.

What is Peer-Review?

In the most general of terms, peer-review is the act of having another writer read what you have written and respond in terms of its effectiveness. This reader attempts to identify the writing's strengths and weaknesses, and then suggests strategies for revising it. The hope is that not only will the specific piece of writing be improved, but that future writing attempts will also be more successful. Peer-review happens with all types of writing, at any stage of the process, and with all levels of writers.

Sometimes peer-review is called a writing workshop.

What is a Writing Workshop?

Peer-review sessions are sometimes called writing workshops. For example, students in a writing class might bring a draft of some writing that they are working on to share with either a single classmate or a group, bringing as many copies of the draft as they will need. There is usually a worksheet to fill out or a set questions for each peer-review reader to answer about the piece of writing. The writer might also request that their readers pay special attention to places where he or she would like specific help. An entire class can get together after reading and responding to discuss the writing as a group, or a single writer and reader can privately discuss the response, or the response can be written and shared in that way only.

Whether peer-review happens in a classroom setting or not, there are some common guidelines to follow.

Common Guidelines for Peer-Review

While peer-review is used in multiple contexts, there are some common guidelines to follow in any peer-review situation.

If You are the Writer

If you are the writer, think of peer-review as a way to test how well your writing is working. Keep an open mind and be prepared for criticism. Even the best writers have room for improvement. Even so, it is still up to you whether or not to take the peer-review reader's advice. If more than one person reads for you, you might receive conflicting responses, but don't panic. Consider each response and decide for yourself if you should make changes and what those changes will be. Not all the advice you get will be good, but learning to make revision choices based on the response is part of becoming a better writer.

If You are the Reader

As a peer-review reader, you will have an opportunity to practice your critical reading skills while at the same time helping the writer improve their writing skills. Specifically, you will want to do as follows:

Read the draft through once

Start by reading the draft through once, beginning to end, to get a general sense of the essay as a whole. Don't write on the draft yet. Use a piece of scratch paper to make notes if needed.

Write a summary

After an initial reading, it is sometimes helpful to write a short summary. A well written essay should be easy to summarize, so if writing a summary is difficult, try to determine why and share that with the writer. Also, if your understanding of the writer's main idea(s) turns out to be different from what the writer intended, that will be a place they can focus their revision efforts.

Focus on large issues

Focus your review on the larger writing issues. For example, the misplacement of a few commas is less important than the reader's ability to understand the main point of the essay. And yet, if you do notice a recurring problem with grammar or spelling, especially to the extent that it interferes with your ability to follow the essay, make sure to mention it.

Be constructive

Be constructive with your criticisms. A comment such as "This paragraph was boring" isn't helpful. Remember, this writer is your peer, so treat him/her with the respect and care that they deserve. Explain your responses. "I liked this part" or "This section doesn't work" isn't enough. Keep in mind that you are trying to help the writer revise, so give him/her enough information to be able to understand your responses. Point to specific places that show what you mean. As much as possible, don't criticize something without also giving the writer some suggestion for a possible solution. Be specific and helpful.

Be positive

Don't focus only on the things that aren't working, but also point out the things that are.

With these common guidelines in mind, here are some specific questions that are useful when doing peer-review.

Questions to Use

When doing peer-review, there are different ways to focus a response. You can use questions that are about the qualities of an essay or the different parts of an essay.

Questions to Ask about the Qualities of an Essay

When doing a peer-review response to a piece of writing, one way to focus it is by answering a set of questions about the qualities of an essay. Such qualities would be:

Organization

- Is there a clearly stated purpose/objective?

- Are there effective transitions?

- Are the introduction and conclusion focused on the main point of the essay?

- As a reader, can you easily follow the writer's flow of ideas?

- Is each paragraph focused on a single idea?

- At any point in the essay, do you feel lost or confused?

- Do any of the ideas/paragraphs seem out of order, too early or too late to be as effective as they could?

Development and Support

- Is each main point/idea made by the writer clearly developed and explained?

- Is the support/evidence for each point/idea persuasive and appropriate?

- Is the connection between the support/evidence, main point/idea, and the overall point of the essay made clear?

- Is all evidence adequately cited?

- Are the topic and tone of the essay appropriate for the audience?

- Are the sentences and word choices varied?

Grammar and Mechanics

- Does the writer use proper grammar, punctuation, and spelling?

- Are there any issues with any of these elements that make the writing unreadable or confusing?

Revision Strategy Suggestions

- What are two or three main revision suggestions that you have for the writer?

Questions to Ask about the Parts of an Essay

When doing a peer-review response to a piece of writing, one way to focus it is by answering a set of questions about the parts of an essay. Such parts would be:

Introduction

- Is there an introduction?

- Is it effective?

- Is it concise?

- Is it interesting?

- Does the introduction give the reader a sense of the essay's objective and entice the reader to read on?

- Does it meet the objective stated in the introduction?

- Does it stay focused on this objective or are there places it strays?

- Is it organized logically?

- Is each idea thoroughly explained and supported with good evidence?

- Are there transitions and are they effective?

- Is there a conclusion?

- Does it work?

Peer-Review Online

Peer-review doesn't happen only in classrooms or in face-to-face situations. A writer can share a text with peer-review readers in the context of a Web classroom. In this context, the writer's text and the reader's response are shared electronically using file-sharing, e-mail attachments, or discussion forums/message boards.

When responding to a document in these ways, the specific method changes because the reader can't write directly on the document like they would if it were a paper copy. It is even more important in this context to make comments and suggestions clear by thoroughly explaining and citing specific examples from the text.

When working with an electronic version of a text, such as an e-mail attachment, the reader can open the document or copy/paste the text in Microsoft Word, or other word-processing software. In this way, the reader can add his or her comments, save and then send the revised document back to the writer, either through e-mail, file sharing, or posting in a discussion forum.

The reader's overall comments can be added either before or after the writer's section of text. If all the comments will be included at the end of the original text, it is still a good idea to make a note in the beginning directing the writer's attention to the end of the document. Specific comments can be inserted into appropriate places in the document, made clear by using all capital letters enclosed with parenthesis. Some word-processing software also has a highlighting feature that might be helpful.

Benefits of Peer Review

Peer-review has a reflexive benefit. Both the writer and the peer-review reader have something to gain. The writer profits from the feedback they get. In the act of reviewing, the peer-review reader further develops his/her own revision skills. Critically reading the work of another writer enables a reader to become more able to identify, diagnose, and solve some of their own writing issues.

Peer Review Worksheets

Here are a few worksheets that you can print out and use for a peer-review session.

Parts of an Essay

- My audience is:

- My purpose is:

- The main point I want to make in this text is:

- One or two things that I would appreciate your comments on are:

- After reading through the draft one time, write a summary of the text. Do you agree with the writer's assessment of the text's main idea?

- In the following sections, answer the questions that would be most helpful to the writer or that seem to address the most relevant revision concerns. Refer to specific places in their text, citing examples of what you mean. Use a separate piece of paper for your responses and comments. Also, write comments directly on the writer's draft where needed.

- Is it effective? Concise? Interesting?

- Is there a conclusion? Does it work?

Finally, what are two or three revision suggestions you have for the writer?

Qualities of an Essay

- After reading through the draft one time, write a summary of the text.

- In the following sections, answer the questions that would be most helpful to the writer or that seem to address the most relevant revision concerns. Use a separate piece of paper for your responses and comments. Also, write comments directly on the writer's draft where needed.

- Is the connection between the support/evidence, main point/idea, and the overall point of the essay made clear?Is all evidence adequately cited?

Salahub, Jill . (2007). Peer Review. Writing@CSU . Colorado State University. https://writing.colostate.edu/guides/guide.cfm?guideid=43

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

5.7: Sample Response Essays

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 92549

.jpg?revision=2)

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Media Alternative

Listen to an audio version of this page (36 sec):

- Sample response paper "Spread Feminism, Not Germs" in PDF with margin notes

- Sample response paper "Spread Feminism, Not Germs" accessible version with notes in parentheses

- Sample response paper "Typography and Identity" in PDF with margin notes

- Sample response paper "Typography and Identity" accessible version with notes in parentheses

ENG 523 Graduate Creative Nonfiction -- The Peer Response

In the peer response, your task is to assume the role of an editor already committed to the eventual publication of the essay. At the same time, your task is not to decide whether you like the piece, in its parts, or as a whole. You're not in the business of judging. It's not done. You're not being asked to say whether the essay is good or bad. Those questions aren't appropriate questions to ask until the piece is finished. The words-- good, bad, like, dislike --aren't appropriate words in this workshop. In the peer response, you attempt to describe and analyze the formal qualities of the draft. You're being asked to describe the draft as a system. Hopefully, what this does for you, as a peer reviewer, is take the pressure off. If you're not sure what the essay's limited persona is, then your job is to say you're not sure, or to make a guess. Your hesitance is important for the author to hear. If the obstacles in the rising action sequence aren't formidable enough yet, or the essay doesn't complicate itself (lacks rising action), your job is to say so. Again, you're describing the draft, not the author. We all want to make our pieces better, and our first task is just to respond to what's right there, on the page. Because all too often, the author has a lot more in their head than is on the page, and they think they've communicated something that they haven't yet, and they think the story means one thing, and the reader thinks it means something else.

In the Peer Response, you must help the author improve the piece. Because of this, you must always remember to be conscientious and constructive. Take a risk, say something that will help the author make their piece better, but say it in a way that can be received well. Always remember, this is a work in progress. As you're reading, always keep in mind what the essay might still become, not just what it already is. Think about the next draft, and the draft after that.

Choose from any of the prompts below which compel you as they relate to your peer's draft. You can write your entire response on one prompt. You can write a response to three prompts or six, or four! Be thoughtful. Look closely and avoid vague generalizations. Always remember: DO NO HARM. Your task is to have the author read your response, feel encouraged by it, but also have a concrete sense of what they might do next.

The Peer Response Buffet

What is the essay about? What are its large concerns? What about what it's about? What does the essay have to say about its subject? This is what Vivian Gornick refers to as the "story": "the insight, the wisdom, the thing one has come to say."

What is the essay's limited persona? Is the persona limited enough?

Why is this memoir being told now ? In other words, how is this problem still a dilemma for the author at the time of writing? How is this problem still vexing, still thrashing around inside the author? (If the author seems at peace now with this problem, there's often no clear reason why this is being told. If the author seems too much at peace (and you don't buy it), perhaps this is because the resolution is over-simplified, and the author hasn't yet embraced how this problem continues in the present.

- Is there a "time-of-writing" voice in the draft that is struggling to make sense of the past? How might this voice be rendered more fully? What might this voice reflect on? (Lopate's Retrospection & Reflection speaks to this.)

Do you have all the basic orienting facts? If not, what's missing?

How is the essay an exploration of change? How might this change be made more clear?

What does the narrator want? What's in the way? Are the obstacles formidable enough?

- How does the beginning of the memoir create an "exchange of expectations" between the author and the reader? Does the piece, as it evolves, meet these expectations? How does it fail (in this draft) to meet those expectations? How might it better meet these expectations in the next draft? Do the expectations created by the beginning of the memoir need to change? Does the beginning need to change?

What questions do you have that the essay does not yet answer?

- Are the scenes rendered in this draft the most important scenes? What needs to be dramatized still? What needs to be more dramatized?

What other craft areas might be developed that would make the draft stronger and more compelling? (A characterization more complexly drawn; the setting better described; an object or metaphor put to further use.)

What patterns are established that might be further developed? How do patterns of characterization, say, relate to patterns of imagery, or plot or diction?

In what way is the draft ambitious? How might this be enhanced?

The Peer Response should be 1-3 pages double spaced, typed . Make sure to indicate which questions you are answering by including the number above, along with your response to it.

Make sure to bring TWO COPIES of your peer response. One to give to me and one to give to the author.

Margin notes are the place where you say to the author: Nice image , or great dialogue , or good description , or Funny , or great transition , good characterization . When I like something in a draft, I usually put a checkmark by it. In your margin notes, you can heap on the praise and good will and fellowship. So read the draft with a pen in your hand, making margin notes along the way. Should you point out spelling errors, typos, individual sentences which confused you? Sure, that would help the author clean up their draft, but the real work is in the answers to the "big picture" questions up above.

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

How to Write a Peer Review

When you write a peer review for a manuscript, what should you include in your comments? What should you leave out? And how should the review be formatted?

This guide provides quick tips for writing and organizing your reviewer report.

Review Outline

Use an outline for your reviewer report so it’s easy for the editors and author to follow. This will also help you keep your comments organized.

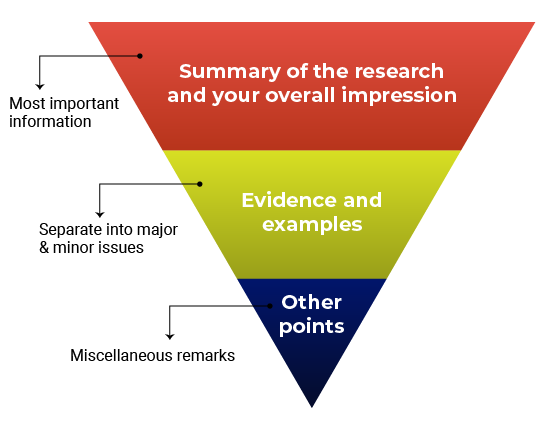

Think about structuring your review like an inverted pyramid. Put the most important information at the top, followed by details and examples in the center, and any additional points at the very bottom.

Here’s how your outline might look:

1. Summary of the research and your overall impression

In your own words, summarize what the manuscript claims to report. This shows the editor how you interpreted the manuscript and will highlight any major differences in perspective between you and the other reviewers. Give an overview of the manuscript’s strengths and weaknesses. Think about this as your “take-home” message for the editors. End this section with your recommended course of action.

2. Discussion of specific areas for improvement

It’s helpful to divide this section into two parts: one for major issues and one for minor issues. Within each section, you can talk about the biggest issues first or go systematically figure-by-figure or claim-by-claim. Number each item so that your points are easy to follow (this will also make it easier for the authors to respond to each point). Refer to specific lines, pages, sections, or figure and table numbers so the authors (and editors) know exactly what you’re talking about.

Major vs. minor issues

What’s the difference between a major and minor issue? Major issues should consist of the essential points the authors need to address before the manuscript can proceed. Make sure you focus on what is fundamental for the current study . In other words, it’s not helpful to recommend additional work that would be considered the “next step” in the study. Minor issues are still important but typically will not affect the overall conclusions of the manuscript. Here are some examples of what would might go in the “minor” category:

- Missing references (but depending on what is missing, this could also be a major issue)

- Technical clarifications (e.g., the authors should clarify how a reagent works)

- Data presentation (e.g., the authors should present p-values differently)

- Typos, spelling, grammar, and phrasing issues

3. Any other points

Confidential comments for the editors.

Some journals have a space for reviewers to enter confidential comments about the manuscript. Use this space to mention concerns about the submission that you’d want the editors to consider before sharing your feedback with the authors, such as concerns about ethical guidelines or language quality. Any serious issues should be raised directly and immediately with the journal as well.

This section is also where you will disclose any potentially competing interests, and mention whether you’re willing to look at a revised version of the manuscript.

Do not use this space to critique the manuscript, since comments entered here will not be passed along to the authors. If you’re not sure what should go in the confidential comments, read the reviewer instructions or check with the journal first before submitting your review. If you are reviewing for a journal that does not offer a space for confidential comments, consider writing to the editorial office directly with your concerns.

Get this outline in a template

Giving Feedback

Giving feedback is hard. Giving effective feedback can be even more challenging. Remember that your ultimate goal is to discuss what the authors would need to do in order to qualify for publication. The point is not to nitpick every piece of the manuscript. Your focus should be on providing constructive and critical feedback that the authors can use to improve their study.

If you’ve ever had your own work reviewed, you already know that it’s not always easy to receive feedback. Follow the golden rule: Write the type of review you’d want to receive if you were the author. Even if you decide not to identify yourself in the review, you should write comments that you would be comfortable signing your name to.

In your comments, use phrases like “ the authors’ discussion of X” instead of “ your discussion of X .” This will depersonalize the feedback and keep the focus on the manuscript instead of the authors.

General guidelines for effective feedback

- Justify your recommendation with concrete evidence and specific examples.

- Be specific so the authors know what they need to do to improve.

- Be thorough. This might be the only time you read the manuscript.

- Be professional and respectful. The authors will be reading these comments too.

- Remember to say what you liked about the manuscript!

Don’t

- Recommend additional experiments or unnecessary elements that are out of scope for the study or for the journal criteria.

- Tell the authors exactly how to revise their manuscript—you don’t need to do their work for them.

- Use the review to promote your own research or hypotheses.

- Focus on typos and grammar. If the manuscript needs significant editing for language and writing quality, just mention this in your comments.

- Submit your review without proofreading it and checking everything one more time.

Before and After: Sample Reviewer Comments

Keeping in mind the guidelines above, how do you put your thoughts into words? Here are some sample “before” and “after” reviewer comments

✗ Before

“The authors appear to have no idea what they are talking about. I don’t think they have read any of the literature on this topic.”

✓ After

“The study fails to address how the findings relate to previous research in this area. The authors should rewrite their Introduction and Discussion to reference the related literature, especially recently published work such as Darwin et al.”

“The writing is so bad, it is practically unreadable. I could barely bring myself to finish it.”

“While the study appears to be sound, the language is unclear, making it difficult to follow. I advise the authors work with a writing coach or copyeditor to improve the flow and readability of the text.”

“It’s obvious that this type of experiment should have been included. I have no idea why the authors didn’t use it. This is a big mistake.”

“The authors are off to a good start, however, this study requires additional experiments, particularly [type of experiment]. Alternatively, the authors should include more information that clarifies and justifies their choice of methods.”

Suggested Language for Tricky Situations

You might find yourself in a situation where you’re not sure how to explain the problem or provide feedback in a constructive and respectful way. Here is some suggested language for common issues you might experience.

What you think : The manuscript is fatally flawed. What you could say: “The study does not appear to be sound” or “the authors have missed something crucial”.

What you think : You don’t completely understand the manuscript. What you could say : “The authors should clarify the following sections to avoid confusion…”

What you think : The technical details don’t make sense. What you could say : “The technical details should be expanded and clarified to ensure that readers understand exactly what the researchers studied.”

What you think: The writing is terrible. What you could say : “The authors should revise the language to improve readability.”

What you think : The authors have over-interpreted the findings. What you could say : “The authors aim to demonstrate [XYZ], however, the data does not fully support this conclusion. Specifically…”

What does a good review look like?

Check out the peer review examples at F1000 Research to see how other reviewers write up their reports and give constructive feedback to authors.

Time to Submit the Review!

Be sure you turn in your report on time. Need an extension? Tell the journal so that they know what to expect. If you need a lot of extra time, the journal might need to contact other reviewers or notify the author about the delay.

Tip: Building a relationship with an editor

You’ll be more likely to be asked to review again if you provide high-quality feedback and if you turn in the review on time. Especially if it’s your first review for a journal, it’s important to show that you are reliable. Prove yourself once and you’ll get asked to review again!

- Getting started as a reviewer

- Responding to an invitation

- Reading a manuscript

- Writing a peer review

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

- UNC Chapel Hill

Category: Peer

Creating a response space in multiparty classroom settings for students using eye-gaze accessed speech-generating devices..