- IAS Preparation

- This Day in History

- This Day In History Dec - 02

Bhopal Gas Tragedy - [December 2, 1984] This Day in History

On the night of 2 December 1984, a gas leak at the Union Carbide India Limited (UCIL) pesticide plant in Bhopal led to the deaths of about 4000 people and adversely affected the health of lakhs of people. The disaster’s after-effects continue to this day. This article shares more details about the Bhopal Gas Tragedy.

Aspirants would find this article very helpful while preparing for the IAS Exam .

Background of the Bhopal Gas Tragedy

- UCIL was a pesticide plant which manufactured the pesticide carbaryl (chemical name: 1-naphthyl methylcarbamate) under the brand name Sevin.

- Carbaryl was discovered by an American company Union Carbide Corporation (UCC) which was UCIL’s parent company holding a majority stake. Minority stakes were held by Indian banks and the public.

- UCIL manufactured carbaryl using methyl isocyanate (MIC) as an intermediate. Although there are other methods to produce the end-product, they cost more.

- MIC is a highly toxic chemical and extremely dangerous to human health.

- Around midnight of 2 December 1984, residents of Bhopal surrounding the pesticide plant began to feel the irritating effects of MIC and started fleeing from the city. However, thousands were dead by morning.

Reasons for the Bhopal Gas Tragedy

- The government of India and activists blame UCIL for flouting safety norms and neglecting proper maintenance and safety procedures. During the build-up to the leak, the plant’s safety systems for the extremely poisonous MIC were not functioning.

- Many valves and lines were in disrepair, and many vent gas scrubbers, as well as the steam boiler meant for cleaning the pipes, were out of service.

- There were three tanks were MIC was stored and the leak occurred in tank E610. This tank contained 42 tons of MIC when it should have contained only 30 tons as per safety rules.

- During the late hours of that fateful night, water is believed to have entered a side pipe and into the tank when workers were trying to unclog it. This caused an exothermic reaction in the tank and increased the tank’s pressure slowly which led to the atmospheric venting of the gas.

- By 11:30 PM, the workers inside the plant were beginning to experience the effects of the toxin.

- There were three safety devices in the plant which could have averted the disaster had they been working properly – a refrigeration system, a flare tower and a vent gas scrubber. The refrigeration system was meant to cool the MIC tank, the flare tower was meant to burn the escaping MIC and the gas scrubber, which had been turned off at that time, was too small to handle a calamity of this scale.

- About 40 metric tons of MIC escaped into the atmosphere within 2 hours.

- The police in Bhopal were informed of the leak by about 1:00 AM. The public became aware of the leak mostly through direct contact with the gas and also by coming out into the open to see what the commotion was about. A timely warning that they should have looked for shelter might also have mitigated the effects of the tragedy.

Consequences of the Bhopal Tragedy

- Feeling of suffocation

- Severe eye irritation

- Burning in the respiratory tract

- Breathlessness

- Stomach pain and vomiting

- Blepharospasm (abnormal contraction or twitching of the eyelid)

- By the morning of 3 rd December, thousands of people had perished due to choking, pulmonary oedema and reflexogenic circulatory collapse. Autopsies indicated that not only lungs, people’s brains, kidneys and liver were also affected.

- The stillbirth rate went up by 300% and the neonatal mortality rate shot up by 200%.

- There were mass burials and cremations in Bhopal.

- Flora and fauna were also severely affected evident by a large number of animal carcasses being seen in the vicinity. Trees became barren within a few days. Supply of food became scarce due to fear of contamination. Fishing was also prohibited.

- The Indian government passed the Bhopal Gas Leak Disaster Act in March 1985 which gave the government the rights to legally represent all victims of the disaster whether in India or elsewhere.

- At least 200,000 children were exposed to the gas and they were more vulnerable owing to their small heights.

- Hospitals and clinics were flooded with victims and the medical staff was not adequately trained to handle MIC exposure.

- Lawsuits were filed against UCC in the US federal court. In one lawsuit, the court suggested UCC provide between $5 million and $10 million to help the victims. UCC agreed to pay $5 million. But the Indian government refused this offer and claimed $3.3 billion.

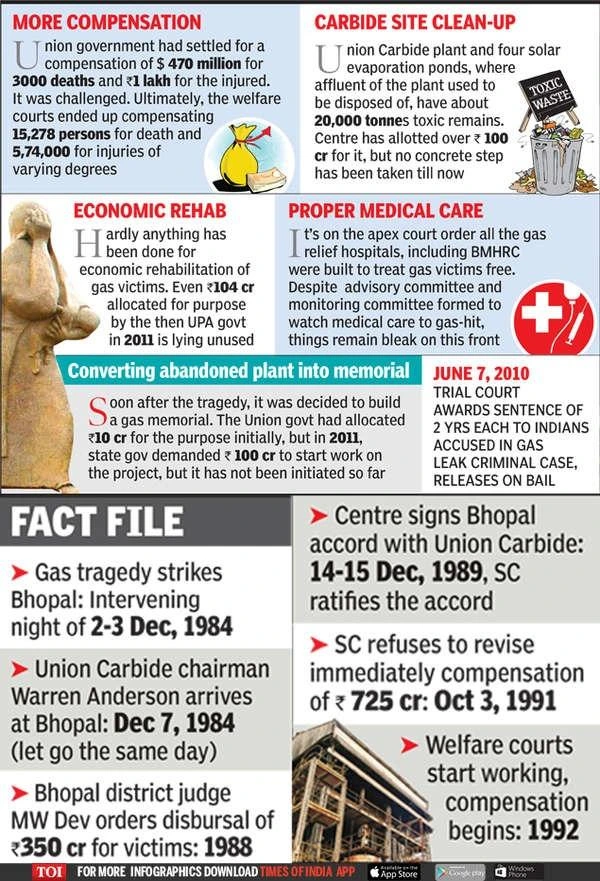

- An out-of-court settlement was reached in 1989 when UCC agreed to pay $470 million for damages caused and paid the sum immediately.

- In 1991, Bhopal authorities charged Warren Anderson, the CEO and Chairman of UCC at the time of the tragedy with manslaughter. He had come to Bhopal immediately after the disaster and was ordered by the Indian government to leave. After being charged, he failed to turn up in court and was declared a fugitive from justice by the Bhopal court in February 1992. Even though the central government pressed the US for extraditing Anderson, nothing came of it. Anderson died in 2014 never having faced trial.

Latest Events Regarding the Bhopal Gas Tragedy

- In 2010, 7 former UCIL employees were sentenced to 2 years imprisonment and fined Rs 1 lakh for causing death by negligence. Most of them were in their seventies and were released on bail.

- The gas leak has significant long-term health effects because of which people who were exposed are suffering till date. Problems include chronic eye problems, problems in the respiratory tract, neurological and psychological problems due to the trauma. Children who were exposed have problems such as stunted growth and intellectual impairments.

- A 2014 report said that survivors still suffer from serious medical conditions including birth defects for subsequent generations and heightened rates of cancer and tuberculosis.

- The disposal of toxic waste lying inside and in the vicinity of the factory is still a problem. The groundwater and the soil have also been severely polluted.

- The fight for justice by the victims of this man-made disaster is still going on.

- UCIL is now owned by Dow Chemical Company. UCC still maintains that the accident was a result of sabotage by disgruntled employees.

- It was reported in June 2020, that in the wake of the Wuhan Coronavirus pandemic, survivors of the Bhopal Gas Tragedy and their children accounted for 80% of the Covid-19 deaths in the city of Bhopal. As the virus targets those with weakened immune systems, the fatalities would increase in the coming days.

Bhopal Gas Tragedy – Download PDF Here

Also on this day

1855 : Birth of Narayan Ganesh Chandavarkar, Hindu reformer.

1988 : Benazir Bhutto became the first woman Prime Minister of Pakistan, and also the first woman to head a government in an Islamic state.

For more information about the general pattern of the UPSC Exams, visit the UPSC Syllabus page. Candidates can also find additional UPSC preparation in the table below:

Related Links

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

IAS 2024 - Your dream can come true!

Download the ultimate guide to upsc cse preparation, register with byju's & download free pdfs, register with byju's & watch live videos.

- Open access

- Published: 10 May 2005

The Bhopal disaster and its aftermath: a review

- Edward Broughton 1

Environmental Health volume 4 , Article number: 6 ( 2005 ) Cite this article

446k Accesses

226 Citations

761 Altmetric

Metrics details

On December 3 1984, more than 40 tons of methyl isocyanate gas leaked from a pesticide plant in Bhopal, India, immediately killing at least 3,800 people and causing significant morbidity and premature death for many thousands more. The company involved in what became the worst industrial accident in history immediately tried to dissociate itself from legal responsibility. Eventually it reached a settlement with the Indian Government through mediation of that country's Supreme Court and accepted moral responsibility. It paid $470 million in compensation, a relatively small amount of based on significant underestimations of the long-term health consequences of exposure and the number of people exposed. The disaster indicated a need for enforceable international standards for environmental safety, preventative strategies to avoid similar accidents and industrial disaster preparedness.

Since the disaster, India has experienced rapid industrialization. While some positive changes in government policy and behavior of a few industries have taken place, major threats to the environment from rapid and poorly regulated industrial growth remain. Widespread environmental degradation with significant adverse human health consequences continues to occur throughout India.

Peer Review reports

December 2004 marked the twentieth anniversary of the massive toxic gas leak from Union Carbide Corporation's chemical plant in Bhopal in the state of Madhya Pradesh, India that killed more than 3,800 people. This review examines the health effects of exposure to the disaster, the legal response, the lessons learned and whether or not these are put into practice in India in terms of industrial development, environmental management and public health.

In the 1970s, the Indian government initiated policies to encourage foreign companies to invest in local industry. Union Carbide Corporation (UCC) was asked to build a plant for the manufacture of Sevin, a pesticide commonly used throughout Asia. As part of the deal, India's government insisted that a significant percentage of the investment come from local shareholders. The government itself had a 22% stake in the company's subsidiary, Union Carbide India Limited (UCIL) [ 1 ]. The company built the plant in Bhopal because of its central location and access to transport infrastructure. The specific site within the city was zoned for light industrial and commercial use, not for hazardous industry. The plant was initially approved only for formulation of pesticides from component chemicals, such as MIC imported from the parent company, in relatively small quantities. However, pressure from competition in the chemical industry led UCIL to implement "backward integration" – the manufacture of raw materials and intermediate products for formulation of the final product within one facility. This was inherently a more sophisticated and hazardous process [ 2 ].

In 1984, the plant was manufacturing Sevin at one quarter of its production capacity due to decreased demand for pesticides. Widespread crop failures and famine on the subcontinent in the 1980s led to increased indebtedness and decreased capital for farmers to invest in pesticides. Local managers were directed to close the plant and prepare it for sale in July 1984 due to decreased profitability [ 3 ]. When no ready buyer was found, UCIL made plans to dismantle key production units of the facility for shipment to another developing country. In the meantime, the facility continued to operate with safety equipment and procedures far below the standards found in its sister plant in Institute, West Virginia. The local government was aware of safety problems but was reticent to place heavy industrial safety and pollution control burdens on the struggling industry because it feared the economic effects of the loss of such a large employer [ 3 ].

At 11.00 PM on December 2 1984, while most of the one million residents of Bhopal slept, an operator at the plant noticed a small leak of methyl isocyanate (MIC) gas and increasing pressure inside a storage tank. The vent-gas scrubber, a safety device designer to neutralize toxic discharge from the MIC system, had been turned off three weeks prior [ 3 ]. Apparently a faulty valve had allowed one ton of water for cleaning internal pipes to mix with forty tons of MIC [ 1 ]. A 30 ton refrigeration unit that normally served as a safety component to cool the MIC storage tank had been drained of its coolant for use in another part of the plant [ 3 ]. Pressure and heat from the vigorous exothermic reaction in the tank continued to build. The gas flare safety system was out of action and had been for three months. At around 1.00 AM, December 3, loud rumbling reverberated around the plant as a safety valve gave way sending a plume of MIC gas into the early morning air [ 4 ]. Within hours, the streets of Bhopal were littered with human corpses and the carcasses of buffaloes, cows, dogs and birds. An estimated 3,800 people died immediately, mostly in the poor slum colony adjacent to the UCC plant [ 1 , 5 ]. Local hospitals were soon overwhelmed with the injured, a crisis further compounded by a lack of knowledge of exactly what gas was involved and what its effects were [ 1 ]. It became one of the worst chemical disasters in history and the name Bhopal became synonymous with industrial catastrophe [ 5 ].

Estimates of the number of people killed in the first few days by the plume from the UCC plant run as high as 10,000, with 15,000 to 20,000 premature deaths reportedly occurring in the subsequent two decades [ 6 ]. The Indian government reported that more than half a million people were exposed to the gas [ 7 ]. Several epidemiological studies conducted soon after the accident showed significant morbidity and increased mortality in the exposed population. Table 1 . summarizes early and late effects on health. These data are likely to under-represent the true extent of adverse health effects because many exposed individuals left Bhopal immediately following the disaster never to return and were therefore lost to follow-up [ 8 ].

Immediately after the disaster, UCC began attempts to dissociate itself from responsibility for the gas leak. Its principal tactic was to shift culpability to UCIL, stating the plant was wholly built and operated by the Indian subsidiary. It also fabricated scenarios involving sabotage by previously unknown Sikh extremist groups and disgruntled employees but this theory was impugned by numerous independent sources [ 1 ].

The toxic plume had barely cleared when, on December 7, the first multi-billion dollar lawsuit was filed by an American attorney in a U.S. court. This was the beginning of years of legal machinations in which the ethical implications of the tragedy and its affect on Bhopal's people were largely ignored. In March 1985, the Indian government enacted the Bhopal Gas Leak Disaster Act as a way of ensuring that claims arising from the accident would be dealt with speedily and equitably. The Act made the government the sole representative of the victims in legal proceedings both within and outside India. Eventually all cases were taken out of the U.S. legal system under the ruling of the presiding American judge and placed entirely under Indian jurisdiction much to the detriment of the injured parties.

In a settlement mediated by the Indian Supreme Court, UCC accepted moral responsibility and agreed to pay $470 million to the Indian government to be distributed to claimants as a full and final settlement. The figure was partly based on the disputed claim that only 3000 people died and 102,000 suffered permanent disabilities [ 9 ]. Upon announcing this settlement, shares of UCC rose $2 per share or 7% in value [ 1 ]. Had compensation in Bhopal been paid at the same rate that asbestosis victims where being awarded in US courts by defendant including UCC – which mined asbestos from 1963 to 1985 – the liability would have been greater than the $10 billion the company was worth and insured for in 1984 [ 10 ]. By the end of October 2003, according to the Bhopal Gas Tragedy Relief and Rehabilitation Department, compensation had been awarded to 554,895 people for injuries received and 15,310 survivors of those killed. The average amount to families of the dead was $2,200 [ 9 ].

At every turn, UCC has attempted to manipulate, obfuscate and withhold scientific data to the detriment of victims. Even to this date, the company has not stated exactly what was in the toxic cloud that enveloped the city on that December night [ 8 ]. When MIC is exposed to 200° heat, it forms degraded MIC that contains the more deadly hydrogen cyanide (HCN). There was clear evidence that the storage tank temperature did reach this level in the disaster. The cherry-red color of blood and viscera of some victims were characteristic of acute cyanide poisoning [ 11 ]. Moreover, many responded well to administration of sodium thiosulfate, an effective therapy for cyanide poisoning but not MIC exposure [ 11 ]. UCC initially recommended use of sodium thiosulfate but withdrew the statement later prompting suggestions that it attempted to cover up evidence of HCN in the gas leak. The presence of HCN was vigorously denied by UCC and was a point of conjecture among researchers [ 8 , 11 – 13 ].

As further insult, UCC discontinued operation at its Bhopal plant following the disaster but failed to clean up the industrial site completely. The plant continues to leak several toxic chemicals and heavy metals that have found their way into local aquifers. Dangerously contaminated water has now been added to the legacy left by the company for the people of Bhopal [ 1 , 14 ].

Lessons learned

The events in Bhopal revealed that expanding industrialization in developing countries without concurrent evolution in safety regulations could have catastrophic consequences [ 4 ]. The disaster demonstrated that seemingly local problems of industrial hazards and toxic contamination are often tied to global market dynamics. UCC's Sevin production plant was built in Madhya Pradesh not to avoid environmental regulations in the U.S. but to exploit the large and growing Indian pesticide market. However the manner in which the project was executed suggests the existence of a double standard for multinational corporations operating in developing countries [ 1 ]. Enforceable uniform international operating regulations for hazardous industries would have provided a mechanism for significantly improved in safety in Bhopal. Even without enforcement, international standards could provide norms for measuring performance of individual companies engaged in hazardous activities such as the manufacture of pesticides and other toxic chemicals in India [ 15 ]. National governments and international agencies should focus on widely applicable techniques for corporate responsibility and accident prevention as much in the developing world context as in advanced industrial nations [ 16 ]. Specifically, prevention should include risk reduction in plant location and design and safety legislation [ 17 ].

Local governments clearly cannot allow industrial facilities to be situated within urban areas, regardless of the evolution of land use over time. Industry and government need to bring proper financial support to local communities so they can provide medical and other necessary services to reduce morbidity, mortality and material loss in the case of industrial accidents.

Public health infrastructure was very weak in Bhopal in 1984. Tap water was available for only a few hours a day and was of very poor quality. With no functioning sewage system, untreated human waste was dumped into two nearby lakes, one a source of drinking water. The city had four major hospitals but there was a shortage of physicians and hospital beds. There was also no mass casualty emergency response system in place in the city [ 3 ]. Existing public health infrastructure needs to be taken into account when hazardous industries choose sites for manufacturing plants. Future management of industrial development requires that appropriate resources be devoted to advance planning before any disaster occurs [ 18 ]. Communities that do not possess infrastructure and technical expertise to respond adequately to such industrial accidents should not be chosen as sites for hazardous industry.

Following the events of December 3 1984 environmental awareness and activism in India increased significantly. The Environment Protection Act was passed in 1986, creating the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) and strengthening India's commitment to the environment. Under the new act, the MoEF was given overall responsibility for administering and enforcing environmental laws and policies. It established the importance of integrating environmental strategies into all industrial development plans for the country. However, despite greater government commitment to protect public health, forests, and wildlife, policies geared to developing the country's economy have taken precedence in the last 20 years [ 19 ].

India has undergone tremendous economic growth in the two decades since the Bhopal disaster. Gross domestic product (GDP) per capita has increased from $1,000 in 1984 to $2,900 in 2004 and it continues to grow at a rate of over 8% per year [ 20 ]. Rapid industrial development has contributed greatly to economic growth but there has been significant cost in environmental degradation and increased public health risks. Since abatement efforts consume a large portion of India's GDP, MoEF faces an uphill battle as it tries to fulfill its mandate of reducing industrial pollution [ 19 ]. Heavy reliance on coal-fired power plants and poor enforcement of vehicle emission laws have result from economic concerns taking precedence over environmental protection [ 19 ].

With the industrial growth since 1984, there has been an increase in small scale industries (SSIs) that are clustered about major urban areas in India. There are generally less stringent rules for the treatment of waste produced by SSIs due to less waste generation within each individual industry. This has allowed SSIs to dispose of untreated wastewater into drainage systems that flow directly into rivers. New Delhi's Yamuna River is illustrative. Dangerously high levels of heavy metals such as lead, cobalt, cadmium, chrome, nickel and zinc have been detected in this river which is a major supply of potable water to India's capital thus posing a potential health risk to the people living there and areas downstream [ 21 ].

Land pollution due to uncontrolled disposal of industrial solid and hazardous waste is also a problem throughout India. With rapid industrialization, the generation of industrial solid and hazardous waste has increased appreciably and the environmental impact is significant [ 22 ].

India relaxed its controls on foreign investment in order to accede to WTO rules and thereby attract an increasing flow of capital. In the process, a number of environmental regulations are being rolled back as growing foreign investments continue to roll in. The Indian experience is comparable to that of a number of developing countries that are experiencing the environmental impacts of structural adjustment. Exploitation and export of natural resources has accelerated on the subcontinent. Prohibitions against locating industrial facilities in ecologically sensitive zones have been eliminated while conservation zones are being stripped of their status so that pesticide, cement and bauxite mines can be built [ 23 ]. Heavy reliance on coal-fired power plants and poor enforcement of vehicle emission laws are other consequences of economic concerns taking precedence over environmental protection [ 19 ].

In March 2001, residents of Kodaikanal in southern India caught the Anglo-Dutch company, Unilever, red-handed when they discovered a dumpsite with toxic mercury laced waste from a thermometer factory run by the company's Indian subsidiary, Hindustan Lever. The 7.4 ton stockpile of mercury-laden glass was found in torn stacks spilling onto the ground in a scrap metal yard located near a school. In the fall of 2001, steel from the ruins of the World Trade Center was exported to India apparently without first being tested for contamination from asbestos and heavy metals present in the twin tower debris. Other examples of poor environmental stewardship and economic considerations taking precedence over public health concerns abound [ 24 ].

The Bhopal disaster could have changed the nature of the chemical industry and caused a reexamination of the necessity to produce such potentially harmful products in the first place. However the lessons of acute and chronic effects of exposure to pesticides and their precursors in Bhopal has not changed agricultural practice patterns. An estimated 3 million people per year suffer the consequences of pesticide poisoning with most exposure occurring in the agricultural developing world. It is reported to be the cause of at least 22,000 deaths in India each year. In the state of Kerala, significant mortality and morbidity have been reported following exposure to Endosulfan, a toxic pesticide whose use continued for 15 years after the events of Bhopal [ 25 ].

Aggressive marketing of asbestos continues in developing countries as a result of restrictions being placed on its use in developed nations due to the well-established link between asbestos products and respiratory diseases. India has become a major consumer, using around 100,000 tons of asbestos per year, 80% of which is imported with Canada being the largest overseas supplier. Mining, production and use of asbestos in India is very loosely regulated despite the health hazards. Reports have shown morbidity and mortality from asbestos related disease will continue in India without enforcement of a ban or significantly tighter controls [ 26 , 27 ].

UCC has shrunk to one sixth of its size since the Bhopal disaster in an effort to restructure and divest itself. By doing so, the company avoided a hostile takeover, placed a significant portion of UCC's assets out of legal reach of the victims and gave its shareholder and top executives bountiful profits [ 1 ]. The company still operates under the ownership of Dow Chemicals and still states on its website that the Bhopal disaster was "cause by deliberate sabotage". [ 28 ].

Some positive changes were seen following the Bhopal disaster. The British chemical company, ICI, whose Indian subsidiary manufactured pesticides, increased attention to health, safety and environmental issues following the events of December 1984. The subsidiary now spends 30–40% of their capital expenditures on environmental-related projects. However, they still do not adhere to standards as strict as their parent company in the UK. [ 24 ].

The US chemical giant DuPont learned its lesson of Bhopal in a different way. The company attempted for a decade to export a nylon plant from Richmond, VA to Goa, India. In its early negotiations with the Indian government, DuPont had sought and won a remarkable clause in its investment agreement that absolved it from all liabilities in case of an accident. But the people of Goa were not willing to acquiesce while an important ecological site was cleared for a heavy polluting industry. After nearly a decade of protesting by Goa's residents, DuPont was forced to scuttle plans there. Chennai was the next proposed site for the plastics plant. The state government there made significantly greater demand on DuPont for concessions on public health and environmental protection. Eventually, these plans were also aborted due to what the company called "financial concerns". [ 29 ].

The tragedy of Bhopal continues to be a warning sign at once ignored and heeded. Bhopal and its aftermath were a warning that the path to industrialization, for developing countries in general and India in particular, is fraught with human, environmental and economic perils. Some moves by the Indian government, including the formation of the MoEF, have served to offer some protection of the public's health from the harmful practices of local and multinational heavy industry and grassroots organizations that have also played a part in opposing rampant development. The Indian economy is growing at a tremendous rate but at significant cost in environmental health and public safety as large and small companies throughout the subcontinent continue to pollute. Far more remains to be done for public health in the context of industrialization to show that the lessons of the countless thousands dead in Bhopal have truly been heeded.

Fortun K: Advocacy after Bhopal. 2001, Chicago , University of Chicago Press, 259.

Chapter Google Scholar

Shrivastava P: Managing Industrial Crisis. 1987, New Delhi , Vision Books, 196.

Google Scholar

Shrivastava P: Bhopal: Anatomy of a Crisis. 1987, Cambridge, MA , Ballinger Publishing, 184.

Accident Summary, Union Carbide India Ltd., Bhopal, India: December 3, 1984. Hazardous Installations Directorate. 2004, Health and Safety Executive

MacKenzie D: Fresh evidence on Bhopal disaster. New Scientist. 2002, 19 (1):

Sharma DC: Bhopal: 20 Years On. Lancet. 2005, 365 (9454): 111-112. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17722-8.

Article Google Scholar

Cassells J: Sovereign immunity: Law in an unequal world. Social and legal studies. 1996, 5 (3): 431-436.

Dhara VR, Dhara R: The Union Carbide disaster in Bhopal: a review of health effects. Arch Environ Health. 2002, 57 (5): 391-404.

Kumar S: Victims of gas leak in Bhopal seek redress on compensation. Bmj. 2004, 329 (7462): 366-10.1136/bmj.329.7462.366-b.

Castleman B PP: Appendix: the Bhopal disaster as a case study in double standards. The export of hazards: trans-national corporations and environmental control issues. Edited by: Ives J. 1985, London , Routledge and Kegan Paul, 213-222.

Mangla B: Long-term effects of methyl isocyanate. Lancet. 1989, 2 (8654): 103-10.1016/S0140-6736(89)90340-1.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Varma DR: Hydrogen cyanide and Bhopal. Lancet. 1989, 2 (8662): 567-568. 10.1016/S0140-6736(89)90695-8.

Anderson N: Long-term effects of mthyl isocyanate. Lancet. 1989, 2 (8662): 1259-10.1016/S0140-6736(89)92347-7.

Chander J: Water contamination: a legacy of the union carbide disaster in Bhopal, India. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2001, 7 (1): 72-73.

Tyagi YK, Rosencranz A: Some international law aspects of the Bhopal disaster. Soc Sci Med. 1988, 27 (10): 1105-1112. 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90305-X.

Carlsten C: The Bhopal disaster: prevention should have priority now. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2003, 9 (1): 93-94.

Bertazzi PA: Future prevention and handling of environmental accidents. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1999, 25 (6): 580-588.

Dhara VR: What ails the Bhopal disaster investigations? (And is there a cure?). Int J Occup Environ Health. 2002, 8 (4): 371-379.

EIA: India: environmental issues. Edited by: energy D. [ http://www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/cabs/indiaenv.html ]

CIA: The world factbook: India. [ http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/geos/in.html#Econ ]

Rawat M, Moturi MC, Subramanian V: Inventory compilation and distribution of heavy metals in wastewater from small-scale industrial areas of Delhi, India. J Environ Monit. 2003, 5 (6): 906-912. 10.1039/b306628b.

Vijay R, Sihorwala TA: Identification and leaching characteristics of sludge generated from metal pickling and electroplating industries by Toxicity Characteristics Leaching Procedure (TCLP). Environ Monit Assess. 2003, 84 (3): 193-202. 10.1023/A:1023363423345.

Karliner J: The corporate planet. 1997, San Francisco , Sierra Club Books, 247.

Bruno KKJ: Earthsummit,biz:The corporate takeover of sustainable development. 2002, Oakland, Ca , First Food Books, 237.

Power M: The poison stream: letter from Kerala. Harper's. 2004, August, 2004: 51-61.

Joshi TK, Gupta RK: Asbestos in developing countries: magnitude of risk and its practical implications. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2004, 17 (1): 179-185.

Joshi TK, Gupta RK: Asbestos-related morbidity in India. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2003, 9 (3): 249-253.

Union Carbide: Bhopal Information Center. wwwbhopalcom/ucshtm. 2005

Corporate Watch UK: DuPont: A corporate profile. [ http://www.corporatewatch.org.uk/profiles/dupont/dupont4.htm ]

Beckett WS: Persistent respiratory effects in survivors of the Bhopal disaster. Thorax. 1998, 53 Suppl 2: S43-6.

Misra UK, Kalita J: A study of cognitive functions in methyl-iso-cyanate victims one year after bhopal accident. Neurotoxicology. 1997, 18 (2): 381-386.

CAS Google Scholar

Irani SF, Mahashur AA: A survey of Bhopal children affected by methyl isocyanate gas. J Postgrad Med. 1986, 32 (4): 195-198.

Download references

Acknowledgements

J. Barab, B. Castleman, R Dhara and U Misra reviewed the manuscript and provided useful suggestions.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Columbia University, Mailman School of Public Health, 600 W, 168th St., New York, NY, 10032, USA

Edward Broughton

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Edward Broughton .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Authors’ original file for figure 1

Rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Broughton, E. The Bhopal disaster and its aftermath: a review. Environ Health 4 , 6 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-4-6

Download citation

Received : 21 December 2004

Accepted : 10 May 2005

Published : 10 May 2005

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-4-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Gross Domestic Product

- Indian Government

- Storage Tank

- Union Carbide Corporation

Environmental Health

ISSN: 1476-069X

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

THE BHOPAL DISASTER: HOW IT HAPPENED

By Stuart Diamond

- Jan. 28, 1985

The Bhopal gas leak that killed at least 2,000 people resulted from operating errors, design flaws, maintenance failures, training deficiencies and economy measures that endangered safety, according to present and former employees, company technical documents and the Indian Government's chief scientist.

Those are among the findings of a seven-week inquiry begun by reporters of The New York Times after the Dec. 3 leak of toxic methyl isocyanate gas at a Union Carbide plant in the central Indian city of Bhopal produced history's worst industrial disaster, stunning India and the world. Among the questions the tragedy raised were how it could have happened and who was responsible.

The inquiry involved more than 100 interviews in Bhopal, New Delhi, Bombay, New York, Washington, Danbury, Conn., and Institute, W. Va. It unearthed information not available even to the Union Carbide Corporation, the majority owner of the plant where the leak occurred, because the Indian authorities have denied corporate representatives access to some documents, equipment and personnel.

Evidence of Violations

The Times investigation produced evidence of at least 10 violations of the standard procedures of both the parent corporation and its Indian-run subsidiary.

Executives of Union Carbide India Ltd., which operated the plant, are reluctant to address the question of responsibility for the tragedy, in which about 200,000 people were injured. The plant's manager has declined to discuss the irregularities. The managing director of the Indian company refused to talk about details of the accident or the conditions that produced it, although he did say that the enforcement of safety regulations was the responsibility of executives at the Bhopal plant.

When questioned in recent days about the shortcomings disclosed in the inquiry by The Times, a spokesman at Union Carbide corporate headquarters in Danbury characterized any suggestion of the accident's causes as speculation and emphasized that Union Carbide would not ''contribute'' to that speculation.

(Articles describing the corporation's relationship with its Indian affiliate and its comments on the accident at Bhopal appear on page A7.)

Summary of Irregularities

A review by The Times of some company documents and interviews with chemical experts, plant workers, company officials and former officials disclosed these and other irregularities at Bhopal:

- When employees discovered the initial leak of methyl isocyanate at 11:30 P.M. on Dec. 2, a supervisor - believing, he said later, that it was a water leak - decided to deal with it only after the next tea break, several workers said. In the next hour or more, the reaction taking place in a storage tank went out of control. ''Internal leaks never bothered us,'' said one employee. Indeed, workers said that the reasons for leaks were rarely investigated. The problems were either fixed without further examination or ignored, they said.

- Several months before the accident, plant employees say, managers shut down a refrigeration unit designed to keep the methyl isocyanate cool and inhibit chemical reactions. The shutdown was a violation of plant procedures.

- The leak began, according to several employees, about two hours after a worker whose training did not meet the plant's original standards was ordered by a novice supervisor to wash out a pipe that had not been properly sealed. That procedure is prohibited by plant rules. Workers think the most likely source of the contamination that started the reaction leading to the accident was water from this process.

- The three main safety systems, at least two of which, technical experts said, were built according to specifications drawn for a Union Carbide plant at Institute, W. Va., were unable to cope with conditions that existed on the night of the accident. Moreover, one of the systems had been inoperable for several days, and a second had been out of service for maintenance for several weeks.

- Plant operators failed to move some of the methyl isocyanate in the problem tank to a spare tank as required because, they said, the spare was not empty as it should have been. Workers said it was a common practice to leave methyl isocyanate in the spare tank, though standard procedures required that it be empty.

- Instruments at the plant were unreliable, according to Shakil Qureshi, the methyl isocyanate supervisor on duty at the time of the accident. For that reason, he said, he ignored the initial warning of the accident, a gauge's indication that pressure in one of three methyl isocyanate storage tanks had risen fivefold in an hour.

- The Bhopal plant does not have the computer system that other operations, including the West Virginia plant, use to monitor their functions and quickly alert the staff to leaks, employees said. The management, they added, relied on workers to sense escaping methyl isocyanate as their eyes started to water. That practice violated specific orders in the parent corporation's technical manual, titled ''Methyl Isocyanate,'' which sets out the basic policies for the manufacture, storage and transportation of the chemical. The manual says: ''Although the tear gas effects of the vapor are extremely unpleasant, this property cannot be used as a means to alert personnel.''

- Training levels, requirements for experience and education and maintenance levels had been sharply reduced, according to about a dozen plant employees, who said the cutbacks were the result, at least in part, of budget reductions. The reductions, they said, had led them to believe that safety at the plant was endangered.

- The staff at the methyl isocyanate plant, which had little automated equipment, was cut from 12 operators on a shift to 6 in 1983, according to several employees. The plant ''cannot be run safely with six people,'' said Kamal K. Pareek, a chemical engineer who began working at the Bhopal plant in 1971 and was senior project engineer during the building of the methyl isocyanate facility there eight years ago.

- There were no effective public warnings of the disaster. The alarm that sounded on the night of the accident was similar or identical to those sounded for various purposes, including practice drills, about 20 times in a typical week, according to employees. No brochures or other materials had been distributed in the area around the plant warning of the hazards it presented, and there was no public education program about what to do in an emergency, local officials said.

- Most workers, according to many employees, panicked as the gas escaped, running away to save their own lives and ignoring buses that sat idle on the plant grounds, ready to evacuate nearby residents.

'A Top Priority'

At its headquarters in Danbury, the parent corporation said last month: ''Union Carbide regards safety as a top priority. We take great steps to insure that the plants of our affiliates, as well as our own plants, are properly equipped with safeguards and that employees are properly trained.''

Over the weekend, in response to questions from The Times, a corporate spokesman described the managers of the Indian affiliate as ''well qualified'' and cited their ''excellent record,'' adding that because of the possibility of litigation in India ''judicial and ethical rules and practices inhibit them from answering questions.''

However, the spokesman said: ''Responsibility for plant maintenance, hiring and training of employees, establishing levels of training and determining proper staffing levels rests with plant management.''

V. P. Gokhale, the chief operating officer of Union Carbide India Ltd., in his first detailed interview since Dec. 3, would not comment on specific violations or the causes of the accident, but he said the Bhopal plant was responsible for its own safety, with little scrutiny from outside experts.

The Indian company has one safety officer at its headquarters in Bombay, Mr. Gokhale said, but that officer is chiefly responsible for keeping up to date the safety manuals used at the company's plants.

Despite the Bhopal plant's autonomy on matters of safety, it was inspected in 1982 by experts from the parent company in the United States, and they filed a critical report.

In the interview, however, Mr. Gokhale contended that the many problems cited in the 1982 report had been corrected. ''There were no indications of problems,'' he said. ''We had no reason to believe there were any grounds for such an accident.''

Mr. Gokhale, who become managing director of Union Carbide India in December 1983 and has been with the company 25 years, added: ''There is no way with 14 factories and 28 sales branches all over the country and 9,000 employees that I could personally supervise any plant on a week-to-week basis.''

At perhaps a dozen points during a two-hour interview, he read his answers into a tape recorder, saying he would inform the parent corporation's Danbury headquarters of what he had said. He also made notes of some of his comments and said he would send them to Danbury for approval by Union Carbide lawyers.

Relationship of the Companies The precise relationship between Union Carbide's American headquarters and its Indian affiliate is a subject that Mr. Gokhale and other company officials have refused to discuss in detail. But an understanding of that relationship is a key element in pinpointing responsibility for the disaster at Bhopal. Lawyers from both the United States and India say it is also central to the lawsuits brought by Bhopal residents damaged by the accident.

Although the situation remains unclear, some evidence of the relationship between the Indian and American companies has begun to emerge. The United States corporation has direct representation on the Indian company's board. J. M. Rehfield, an executive vice president in Danbury, sits on that board, Mr. Gokhale acknowledged, as do four representatives of Union Carbide Eastern Inc., a division based in Hong Kong. Mr. Gokhale said the board of directors reviews reports on the Indian affiliate's operations.

Moreover, some key safety decisions affecting Bhopal were reportedly made or reviewed at the corporate headquarters in Danbury.

Srinivasan Varadarajan, the Indian Government's chief scientist, said his staff had been told by managers of the Bhopal plant that the refrigeration unit designed to chill the methyl isocyanate, which he said was very small and had never worked satisfactorily, had been disconnected because the managers had concluded after discussions with American headquarters that the device was not necessary.

A spokesman at corporate headquarters in Danbury, Thomas Failla, said: ''As far as we have been able to establish, the question of turning off the refrigeration unit was not discussed with anyone at Union Carbide Corporation.''

The methyl isocyanate operating manual in use at Bhopal, which was adapted by five Indian engineers from a similar document written for the West Virginia plant, according to a former senior official at Bhopal, says: ''Keep circulation of storage tank contents continuously 'ON' through the refrigeration unit.''

And a senior official of Union Carbide India said few if any people would have died Dec. 3 had the unit been running because it would have slowed the chemical reaction that took place during the accident and increased the warning time from two hours to perhaps two days.

Workers said that when the 30-ton refrigeration unit was shut down, electricity was saved and the Freon in the coils of the cooling unit was pumped out to be used elsewhere in the plant.

Mr. Gokhale specifically declined to answer questions about the refrigeration unit.

Employees Criticize Morale

Many employees at the Bhopal plant described a factory that was once a showpiece but that, in the face of persistent sales deficits since 1982, had lost much of its highly trained staff, its morale and its attention to the details that insure safe operation.

''The whole industrial culture of Union Carbide at Bhopal went down the drain,'' said Mr. Pareek, the former project engineer. ''The plant was losing money, and top management decided that saving money was more important than safety. Maintenance practices became poor, and things generally got sloppy. The plant didn't seem to have a future, and a lot of skilled people became depressed and left as a result.''

Mr. Pareek said he resigned in December 1983 because he was disheartened about developments at the plant and because he was offered a better job with Goodyear India Ltd. as a divisional production manager.

Mr. Gokhale termed the company's cost-cutting campaign simply an effort to reduce ''avoidable and wasteful expenditures.''

The corporate spokesman in Danbury said Union Carbide has ''an ongoing operations improvement program which involves, among other things, a regular review of ways to reduce costs.'' He said Union Carbide India was involved in such programs, ''but the details of those programs at the Bhopal plant are not known to us.''

The spokesman added: ''Financial information supplied to us indicated that the Bhopal plant was not profitable.''

In the absence of official company accounts, details of the accident and its causes have been provided by technical experts such as Dr. Varadarajan and Mr. Pareek and by three dozen plant workers, past and present company officials and other people with direct knowledge of the factory's operations. Many of them agreed to be interviewed only on condition that they not be identified. Most of the workers knew little English and spoke in Hindi through an interpreter.

They provided some documents but often relied upon their recollections because many plant files and even public records have been impounded by the Indian authorities investigating the accident.

'Potential for Serious Accident'

Nearly all those interviewed contended that the company had been neither technically nor managerially prepared for the accident. The 1982 inspection report seemed to support that view, saying the Bhopal plant's safety problems represented ''a higher potential for a serious accident or more serious consequences if an accident should occur.''

That report ''strongly'' recommended, among other things, the installation of a larger system that would supplement or replace one of the plant's main safety devices, a water spray designed to contain a chemical leak. That change was never made, plant employees said, and on Dec. 3 the spray was not high enough to reach the escaping gas.

The spokesman in Danbury said the corporation had been informed that Union Carbide India had taken ''all the action it considered necessary to respond effectively'' to the 1982 report.

Another of the safety devices, a gas scrubber or neutralizer, one of the systems said to have been built according to the specifications used at the West Virginia plant, was unable to cope with the accident because it had a maximum design pressure one-quarter that of the leaking gas, according to plant documents and employees.

The third safety system, a flare tower that is supposed to burn off escaping gases, would theoretically have been capable of handling about a quarter of the volume of the leaking gas were it not under such pressure, according to Mr. Pareek. The pressure, he said, was high enough to burst a tank through which gases must flow before being channeled up the flare tower. The tower was the second system described by technical experts as conforming to the specifications used in West Virginia.

In any case, the pressure limitations of the flare tower were immaterial because it was not operating at the time of the accident.

Guidelines for Design

A former executive at the Bhopal plant said the parent corporation had provided guidelines for the design of the scrubber, the flare tower and the spray system. But detailed design work for those systems and the entire plant, he said, was performed by Humphreys & Glasgow Consultants Pvt. Ltd. of Bombay, a subsidiary of Humphreys & Glasgow Ltd., a consulting company based in London. The London company in turn is owned by the Enserch Corporation of Dallas.

The spokesman in Danbury said the Union Carbide Corporation had provided its Indian affiliate with ''a process design package containing information necessary and sufficient'' for the affiliate to arrange the design and construction of the plant and its equipment.

The spokesman said the corporation had only incomplete information on the scrubber, flare tower and other pieces of equipment, and he declined to comment on their possible relationship to the accident.

It was unclear whether the limitations of the safety systems resulted from the guidelines provided by the Union Carbide Corporation or from the detailed designs.

Employees at the plant recalled after the accident that during the evening of Dec. 2 they did not realize how high the pressures were in the system. Suman Dey, the senior operator on duty, said he was in the control room at about 11 P.M. and noticed that the pressure gauge in one tank read 10 pounds a square inch, about five times normal. He said he had thought nothing of it.

Mr. Qureshi, an organic chemist who had been a methyl isocyanate supervisor at the plant for two years, had the same reaction half an hour later. The readings were probably inaccurate, he thought. ''There was a continual problem with instruments,'' he said later. ''Instruments often didn't work.''

Leak Found but Tea Is First

About 11:30 P.M., workers in the methyl isocyanate structure, about 100 feet from the control room, detected a leak. Their eyes started to water.

V. N. Singh, an operator, spotted a drip of liquid about 50 feet off the ground, and some yellowish-white gas in the same area. He said he went to the control room about 11:45 and told Mr. Qureshi of a methyl isocyanate leak. He quoted Mr. Qureshi as responding that he would see to the leak after tea.

Mr. Qureshi contended in an interview that he had been told of a water leak, not an escape of methyl isocyanate.

No one investigated the leak until after tea ended, about 12:40 A.M., according to the employees on duty.

Such inattention merely compounded an already dangerous situation, according to Dr. Varadarajan, the Government scientist.

He is a 56-year-old organic and biological chemist who holds doctoral degrees from Cambridge and Delhi universities and was a visiting lecturer in biological chemistry at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He heads the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, the Government's central research organization, which operates 42 national laboratories.

In the two weeks after the accident, Dr. Varadarajan said, he and a staff gathered from the research council questioned factory managers at Bhopal, directed experiments conducted by the plant's research staff and analyzed the results of those tests. Some of the experiments were conducted on methyl isocyanate that remained at the Bhopal plant after the accident, he said, and some were designed to measure the reliability of testing procedures used at the factory.

Dr. Varadarajan said in a long interview that routine tests conducted at the Bhopal factory used a faulty method, so the substance may have been more reactive than the company believed.

For example, he said, the Bhopal staff did not adequately measure the incidence in methyl isocyanate or the possible effects of chloride ions, which are highly reactive in the presence of small amounts of water. Chlorine, of which chloride is an ion, is used in the manufacture of methyl isocyanate.

Dr. Varadarajan argued that the testing procedure used at Bhopal assumed that all of the chloride ions present resulted from the breakdown of phosgene and therefore the tests measured phosgene, not chloride ions. Phosgene is used in the manufacture of methyl isocyanate, and some of it is left in the compound to inhibit certain chemical reactions.

When his staff secretly added chloride ions to methyl isocyanate to be tested by the factory staff, Dr. Varadarajan said, the tests concluded that 23 percent of the chloride was phosgene.

''As yet,'' the scientist said, ''Union Carbide has been unable to provide an unequivocal method of distinguishing between phosgene and chloride'' in methyl isocyanate.

Tests 'Made Routinely'

The Union Carbide spokesman in Danbury said: ''Tests for chloride-containing materials, including chloride ions in the tank are made routinely.''

Dr. Varadarajan said his staff had produced its own hypotheses of the accident's causes after Union Carbide failed to provide any, even on request.

The spokesman in Danbury said that a team of ''exceptionally well qualified'' chemists and engineers from Union Carbide had been studying the accident for seven weeks ''and still has not been able to determine the cause.'' He added:

''Anyone who attempts to state what caused the accident would be only speculating unless he has more facts than we have and has done more analysis, tests and experiments than we have. Anyone who speculates about the cause of the accident should conspicuously label it as speculation.''

Dr. Varadarajan's analysis, along with internal Union Carbide documents and conversations with workers, offers circumstantial evidence for at least one explanation of what triggered the accident.

There were 45 metric tons, or about 13,000 gallons, of methyl isocyanate in the tank that leaked, according to plant workers. That would mean the tank was 87 percent full.

Union Carbide's spokesman in Danbury said the tank contained only 11,000 gallons of the chemical, ''which was well below the recommended maximum working capacity of the 15,000- gallon tank.''

However, even that lower level - 73 percent of capacity - exceeds the limit set in the Bhopal operating manual, which says: ''Do not fill MIC storage tanks beyond 60 percent level.'' MIC is the abbreviation for methyl isocyanate.

And the parent corporation's technical manual suggests an even lower limit, 50 percent.

The reason for the restrictions, according to technical experts formerly employed at the plant, was that in case of a large reaction pressure in the storage tank would rise less quickly, allowing more time for corrective action before a possible escape of toxic gas.

For 13,000 gallons of the chemical, the amount reported by the plant staff, to have reacted with water, at least 1.5 tons or 420 gallons of water would have been required, according to Union Carbide technical experts.

But those experts said that an analysis of the tank's contents had not disclosed water-soluble urea, or biuret, the normal product of a reaction between water and methyl isocyanate.

Furthermore, all of those interviewed agreed that it was highly unlikely that 420 gallons of water could have entered the storage tank.

Hypothesis on the Cause Those observations led Dr. Varadarajan and his staff to suggest that there may have been another reaction: water and phosgene.

Phosgene, which was used as a chemical weapon during World War I, inhibits reactions between water and methyl isocyanate because water selectively reacts first with phosgene.

But Dr. Varadarajan said his study had found that the water-phosgene reaction produced something not suggested in the Union Carbide technical manual: highly corrosive chloride ions, which can react with the stainless steel walls of a tank, liberating metal corrosion products - chiefly iron - and a great deal of heat.

The heat, the action of the chloride ions on methyl isocyanate, which releases more heat, and the chloride ions' liberation of the metals could combine to start a runaway reaction, he said.

''Only a very small amount of water would be needed to start a chain reaction,'' he said, estimating the amount at between one pint and one quart.

Beyond its routine checks for the presence of chloride, the corporate spokesman said in Danbury, Union Carbide specifies that tanks be built of certain types of stainless steel that do not react with methyl isocyanate.

He did not say whether the specified types of stainless steel react with chloride ions.

Dr. Varadarajan said his hypothesis had been confirmed by laboratory experiments in which the methyl isocyanate polymerized, or turned into a kind of plastic, about 15 tons of which was found in the tank that leaked.

Other Contaminants Possible

But that is not the only possible explanation of the disaster at Bhopal. Although water breaks down methyl isocyanate in the open air, it can react explosively with the liquid chemical in a closed tank. Lye can also react with it in a closed tank, but in the gas neutralizer, or scrubber, a solution of water and lye neutralizes escaping gas. Beyond water and lye, methyl isocyanate reacts strongly, often violently, with a variety of contaminants, including acids, bases and metals such as iron.

Most of those contaminants are present at the plant under certain conditions. Water is used for washing and condenses on pipes, tanks and other equipment colder than the surrounding air. Lye, or sodium hydroxide, a base, is sometimes used to clean equipment. Metals are the corrosion products of the stainless steel tanks used to store methyl isocyanate.

Union Carbide Corporation's technical manual on methyl isocyanate, published in 1976, recognizes the dangers. It says that metals in contact with methyl isocyanate can cause a ''dangerously rapid'' reaction. ''The heat evolved,'' it adds, ''can generate a reaction of explosive violence.'' When the chemical is not refrigerated, the manual says, its reaction with water ''rapidly increases to the point of violent boiling.'' The presence of acids or bases, it adds, ''greatly increases the rate of the reaction.'' Sources of Contaminants

Investigators from both Union Carbide India and its parent corporation have found evidence of at least five contaminants in the tank that leaked, according to nuclear magnetic resonance spectrographs that were obtained by The New York Times and analyzed by two Indian technical experts at the request of The Times. Among the contaminants, a senior official of the Indian company said, were water, iron and lye.

The water came from the improperly sealed pipe that had been washed, workers speculated, or perhaps was carried into the system after it had condensed in nitrogen that is used to replace air in tanks and pipes to reduce the chance of fire.

In the days before the accident, workers said, they used nitrogen in an unsuccessful attempt to pressurize the tank that leaked on Dec. 3. The nitrogen is supposed to be sampled for traces of moisture, but ''we didn't check the moisture all the time,'' said Mr. Qureshi, the supervisor.

During the same period, the workers said, they added lye to the scrubber, which is connected to the storage tanks by an intricate set of pipes and valves that are supposed to be closed in normal conditions but that workers said were sometimes open or leaking.

Dr. Varadarajan said he was particularly troubled that, in the absence of what he considered sufficient basic research on the stability of commercial methyl isocyanate, it was stored in such large quantities. ''I might keep a small amount of kerosene in my room for my stove,'' he said, ''but I don't keep a large tank in the room.''

The Union Carbide Corporation decided that it would be more efficient to store the chemical in large quantities, former officials of the Indian affiliate said, so that a delay in the production of methyl isocyanate would not disrupt production of the pesticides of which it is a component.

Many plants store methyl isocyanate in 52-gallon drums, which are considered safer than large tanks because the quantity in each storage vessel is smaller. The chemical was stored in drums at Bhopal when it was imported from the United States. Tank storage began in 1980, when Bhopal started producing its own methyl isocyanate.

The Union Carbide technical manual for methyl isocyanate suggests that drum storage is safer. With large tank storage, it says, contamination - and, therefore, accidents - are more likely. The drums do not typically require refrigeration, the manual says. But it cautions that refrigeration is necessary for bulk storage.

Training Was Limited

Although the storage system increased the risk of trouble at Bhopal, the plant's operating manual for methyl isocyanate offered little guidance in the event of a large leak.

After telling operators to dump the gas into a spare tank if a leak in a storage tank cannot be stopped or isolated, the manual says: ''There may be other situations not covered above. The situation will determine the appropriate action. We will learn more and more as we gain actual experience.''

Some of the operators at the plant expressed disatisfaction with their own understanding of the equipment for which they were responsible.

M. K. Jain, an operator on duty on the night of the accident, said he did not understand large parts of the plant. His three months of instrument training and two weeks of theoretical work taught him to operate only one of several methyl isocyanate systems, he said. ''If there was a problem in another MIC system, I don't know how to deal with it,'' said Mr. Jain, a high school graduate.

Rahaman Khan, the operator who washed the improperly sealed pipe a few hours before the accident, said: ''I was trained for one particular area and one particular job. I don't know about other jobs. During training they just said, 'These are the valves you are supposed to turn, this is the system in which you work, here are the instruments and what they indicate. That's it.' ''

'It Was Not My Job'

As to the incident on the day of the accident, Mr. Khan said he knew the pipe was unsealed but ''it was not my job'' to do anything about it.

Previously, operators say, they were trained to handle all five systems involved in the manufacture and storage of methyl isocyanate. But at the time of the accident, they said, only a few of about 20 operators at Bhopal knew the whole methyl isocyanate plant.

The first page of the Bhopal operating manual says: ''To operate a plant one should have an adequate knowledge of the process and the necessary skill to carry out the different operations under any circumstances.''

Part of the preparatory process was ''what if'' training, which is designed to help technicians react to emergencies. C. S. Tyson, a Union Carbide inspector from the United States who studied the Bhopal plant in 1982, said recently that inadequate ''what if'' training was one of the major shortcomings of that facility.

Beyond training, workers raised questions about lower employment qualifications. Methyl isocyanate operators' jobs, which once required college science degrees, were filled by high school graduates, they said, and managers experienced in dealing with methyl isocyanate were often replaced by less qualified personnel, sometimes transfers from Union Carbide battery factories, which are less complex and potentially dangerous than methyl isocyanate operations.

Maintenance Team Reduced

The workers also complained about the maintenance of the Bhopal plant. Starting in 1984, they said, nearly all major maintenance was performed on the day shift, and there was a backlog of jobs. This situation was compounded, the methyl isocyanate operators said, because since 1983 there had been 6 rather than 12 operators on a shift, so there were fewer people to prepare equipment for maintenance.

As a result of the backlog, the flare tower, one of the plant's major safety systems, had been out of operation for six days at the time of the accident, workers said. It was awaiting the replacement of a four-foot pipe section, they said, a job they estimated would take four hours.

The vent gas scrubber, the employees said, had been down for maintenance since Oct. 22, although the plant procedures specify that it be ''continously operated'' until the plant is ''free of toxic chemicals.''

The plant procedures specify that the chiller must be operating whenever there is methyl isocyanate in the system. The Bhopal operating manual says the chemical must be maintained at a temperature no higher than 5 degrees centigrade or 41 degrees Fahrenheit. It specifies that a high temperature alarm is to sound if the methyl isocyanate reaches 11 degrees centigrade or 52 degrees Fahrenheit.

But the chiller had been turned off, the workers said, and the chemical was usually kept at nearly 20 degrees centigrade, or 68 degrees Fahrenheit. They said plant officials had adjusted the temperature alarms to sound not at 11 degrees but at 20 degrees centigrade.

That temperature, they maintained, is well on the way to methyl isocyanate's boiling point, 39.1 degrees centigrade, or 102.4 degrees Fahrenheit. Moreover, Union Carbide's 1976 technical manual warns specifically that if methyl isocyanate is kept at 20 degrees centigrade a contaminant can spur a runaway reaction. The manual says the preferred temperature is 0 degrees centigrade, or 32 degrees Fahrenheit.

If the refrigeration unit had been operating, a senior official of the Indian company said, it would have taken as long as two days, rather than two hours, for the methyl isocyanate reaction to produce the conditions that caused the leak. This would have given plant personnel sufficient time to deal with the mishap and prevent most, if not all, loss of life, he said.

The methyl isocyanate operating manual directs workers unable to contain a leak in a storage tank to dump some of the escaping gas into a 15,000- gallon tank that was to remain empty for that purpose. But the workers on duty said that during the accident they never opened the valve to the spare tank, and their supervisors never ordered them to do so. The workers said they had not tried to use the spare tank because its level indicator said it was 22 percent full and they feared that hot gas from the leaking tank might spark another reaction in the spare vessel.

The level indicator, according to the operators on duty that night, was wrong. The spare tank contained only 437 gallons of methyl isocyanate, not the 3,300 gallons indicated by the gauge.

Nonetheless, standard procedures had been violated. The operating manual says, ''Always keep one of the storage tanks empty. This is to be used as dump tank during emergency.'' It provides that any tank less than 20 percent full be emptied completely.

The spokesman in Danbury said, ''Our investigators did find some MIC in a spare tank,'' adding: ''We do not know when and how the MIC got into the spare tank.'' NEXT: What happened that night.

Win up to 100% Scholarship

- UPSC Online

- UPSC offline and Hybrid

- UPSC Optional Coaching

- UPPCS Online

- BPSC Online

- MPSC Online

- MPPSC Online

- WBPSC Online

- OPSC Online

- UPPCS Offline Coaching

- BPSC Offline Coaching

- UPSC Test Series

- State PSC Test Series

- DAILY CURRENT AFFAIRS

- SUBJECT WISE CURRENT AFFAIRS

- DAILY EDITORIAL ANALYSIS

- DAILY CURRENT AFFAIRS QUIZ

- Daily Prelims(MCQs) Practice

- Daily Mains Answer Writing

- Free Resources

- Offline Centers

- NCERT Notes

- UDAAN Notes

- UPSC Syllabus

- UPSC Prelims PYQs

- UPSC Mains PYQs

- Prelims Preparation

Bhopal Gas Leak 1984: Causes, Impact, and Post-Disaster Measures

Context: December 2 and 3, 2023 marks the 39th anniversary of the Bhopal Gas Tragedy, occurred aftermath of Bhopal Gas Leak.

The Bhopal Gas Leak Tragedy: Union Carbide Factory and the Deadly Chemical Disaster

- Construction of Factory: The Union Carbide factory was built in 1969 to produce the pesticide Sevin , which was the brand name for carbaryl , using methyl isocyanate (MIC) as an intermediary.

- Chemical Process : The Bhopal factory employed the process where methylamine reacts with phosgene to form MIC, which was in turn reacted with 1-naphthol to form the final product, carbaryl.

- Accumulation of Deadly Chemical: Despite the lack of demand for pesticides, the production process continued leading to an accumulation of unused MIC at the factory in underground tanks.

The Bhopal Gas Leak Tragedy: Unveiling the Worst Industrial Disaster in History

- The Event: Bhopal Gas Leak is often considered the worst industrial disaster in history, which not only resulted in deaths but also chronic diseases.

- Cause Bhopal Gas Leak: The disaster was caused on December 3, 1984 when 40 tons of toxic methyl isocyanate (MIC) gas leaked out of a pesticide factory in the city of Bhopal.

- Each of these tanks was pressurized with inert nitrogen gas , which allowed liquid MIC to be pumped out of each tank as needed.

- On 2nd December, water accidentally entered one of the underground tanks holding MIC, triggering an instant exothermic reaction caused by the presence of contaminants, high ambient temperatures, and various other factors.

- Gaseous MIC began escaping from atmospheric vents , with 40 tonnes of the highly toxic gas escaping within 2 hours.

- Symptoms of Exposure : Symptoms of the gas exposure included coughing, severe eye irritation, a feeling of suffocation, burning in the respiratory tract, breathlessness, stomach cramps, and vomiting .

- Causes of Death: Choking, reflexogenic circulatory collapse, and pulmonary oedema were the primary causes of death in people.

Root Causes of the Bhopal Gas Leak Disaster: A Chronicle of Neglect, Safety Lapses, and Regulatory Gaps

- Lack of Knowledge: The workers in charge of handling the plant did not have knowledge about the dangerous nature of the chemicals and thus observed general laxity in safety rules.

- Emergency Plans: The plant was being run without adequate safety measures , including emergency plans in case of disaster.

- Lack of Specific Laws: There was a lack of specific laws in India at the time for handling such matters related to industrial leak.

- Flare towers and sirens were not in operation. Water hoses were not strong enough to contain gas leak from a height.

- Safety Neglect: There were allegations of neglect of safety equipment for saving costs, including safety valve, refrigeration of tanks etc.

- Underinvestment: Investments for improving the plant were stopped . There were reduced funds for maintenance, and employee training was also compromised.

Bhopal Gas Leak Aftermath: Tragedy’s Lingering Impact on Health, Environment, and Community Displacement

- Deaths: The poisonous gas killed thousands of people in a short span of time, with the final number being estimated at about 25,000.

- Long-term Health Impact: People born in Bhopal after 1985 have a hig her risk of cancer, lower education accomplishment and higher rates of disabilities .

- Underground Water Pollution: Studies revealed that the sources of water around the factory were deemed unfit for consumption and many handpumps were sealed.

- Displacement: Large number of people were forcibly evacuated from the site for the fears of further leak of gas.

- Food Scarcity: People living in the proximity of the factory had to discard all food sources for the fear of contamination.

Aftermath of Bhopal Gas Leak: Compensation Challenges, Legal Actions, and Post-Disaster Regulatory Measures

- The Indian government and Union Carbide struck a mutual deal and compensation of $470 million was given by UC. However, there are complaints regarding delay in release of money.

- Charges against Officials : Charges were filed against Union Carbide chairman and other officials. They were released on bail and never faced punishment.

- The act strengthens the regulations on pollution control and environment protection by hazardous industries.

- Public Liability Insurance Act of 1991: The law provides public liability insurance for providing immediate relief to the persons affected by an accident occurring while handling any hazardous substance.

The Characteristics, Uses, and Health Impacts of Methyl Isocyanate (MIC) – Root Cause of Bhopal Gas Leak

- About: Methyl Isocyanate (MIC) is a flammable chemical that evaporates when exposed to air. It is liquid in form and has colourless pungent features.

- Production: Methyl Isocyanate is obtained by reacting methylamine with phosgene .

- It is also used in production of polyurethane foams and plastics.

- Density: Gaseous methyl isocyanate is slightly denser than air and hence accumulates near the ground level.

- Incompatibility: Methyl Isocyanate reacts violently with water and also incompatible with oxidizers, acids, alkalis, amines, iron, tin, and copper .

- Exposure to the chemical may cause irritation of the skin or eyes and severe ocular damage.

- Ingestion of the chemical could produce severe gastrointestinal irritation .

- Inhalation of the chemical may cause severe pulmonary edema and injury to the alveolar walls of the lung and death.

- Treatment for exposure: There is no antidote available against methyl isocyanate. Treatment mainly includes removal of the victim from the contaminated area and support of respiratory and cardiovascular functions .

Conclusion:

The Bhopal Gas Leak disaster remains to be one of the biggest industrial disasters of all time. The lives of people affected have never been the same.

Frequently Asked Questions

When did the bhopal gas leak disaster occur, which company was involved in the disaster, what was the name of the gas responsible for the disaster, what are the reasons for the disaster, which laws were introduced post the disaster.

UPDATED :

Recommended For You

UPSC Application Form 2024, Steps for Registration, Apply On...

Telangana Foundation Day 2024 Theme, History, Significance, ...

CSAT Books for UPSC Prelims

Download upsc prelims question paper 2024, to be updated soo....

World Milk Day 2024 Date, Theme, History, Statistics and Ind...

UPSC Prelims Admit Card 2024, Steps to Download UPSC Prelims...

Latest comments.

UPSC Results 2024 Live, Result Declared, Down...

UPSC Topper 2024 – Download List, Marks...

UPSC CSE Final Result 2024 – Prelims, M...

Recent posts, upsc application form 2024, steps for registr..., telangana foundation day 2024 theme, history,..., download upsc prelims question paper 2024, to..., world milk day 2024 date, theme, history, sta..., archive calendar.

THE MOST LEARNING PLATFORM

Learn From India's Best Faculty

Our Courses

Our initiatives, beginner’s roadmap, quick links.

PW-Only IAS came together specifically to carry their individual visions in a mission mode. Infusing affordability with quality and building a team where maximum members represent their experiences of Mains and Interview Stage and hence, their reliability to better understand and solve student issues.

Subscribe our Newsletter

Sign up now for our exclusive newsletter and be the first to know about our latest Initiatives, Quality Content, and much more.

Contact Details

G-Floor,4-B Pusha Road, New Delhi, 110060

- +91 9920613613

- [email protected]

Download Our App

Biginner's roadmap, suscribe now form, fill the required details to get early access of quality content..

Join Us Now

(Promise! We Will Not Spam You.)

CURRENT AF.

<div class="new-fform">

Select centre Online Mode Hybrid Mode PWonlyIAS Delhi (ORN) PWonlyIAS Delhi (MN) PWonlyIAS Lucknow PWonlyIAS Patna Other

Select course UPSC Online PSC ONline UPSC + PSC ONLINE UPSC Offline PSC Offline UPSC+PSC Offline UPSC Hybrid PSC Hybrid UPSC+PSC Hybrid Other

</div>

- International

- Today’s Paper

- EXIT POLL RESULTS 2024

- 🗳️ History of Elections

- Premium Stories

- Brand Solutions