- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.7: Leadership and the Qualities of Political Leaders

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 128427

- Robert W. Maloy & Torrey Trust

- University of Massachusetts via EdTech Books

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Standard 4.7: Leadership and the Qualities of Political Leaders

Apply the knowledge of the meaning of leadership and the qualities of good leaders to evaluate political leaders in the community, state, and national levels. (Massachusetts Curriculum Framework for History and Social Studies) [8.T4.7]

FOCUS QUESTION: What is effective political leadership?

Standard 4.7 addresses political leadership and the qualities that people seek in those they choose for leadership roles in democratic systems of government.

Leadership involves multiple skills and talents. It has been said that an effective leader is someone who knows "when to lead, when to follow, and when to get out of the way" (the phrase is attributed to the American revolutionary Thomas Paine). In this view, effective leaders do much more than give orders. They create a shared vision for the future and viable strategic plans for the present. They negotiate ways to achieve what is needed while also listening to what is wanted. They incorporate individuals and groups into processes of making decisions and enacting policies by developing support for their plans.

Different organizations need different types of leaders. A commercial profit-making firm needs a leader who can grow the business while balancing the interests of consumers, workers, and shareholders. An athletic team needs a leader who can call the plays and manage the personalities of the players to achieve success on the field and off it. A school classroom needs a teacher-leader who knows the curriculum and pursues the goal of ensuring that all students can excel academically, socially, and emotionally. Governments—local, state, and national—need political leaders who can fashion competing ideas and multiple interests into policies and practices that will promote equity and opportunity for all.

The Massachusetts learning standard on which the following modules are based refers to the "qualities of good leaders," but what does a value-laden word like "good" mean in political and historical contexts? "Effective leadership" is a more nuanced term. What is an effective political leader? In the view of former First Lady Rosalynn Carter, "A leader takes people where they want to go. A great leader takes people where they don't necessarily want to go, but ought to be."

Examples of effective leaders include:

- Esther de Berdt is not a well-known name, but during the Revolutionary War, she formed the Ladies Association of Philadelphia to provide aid (including raising more than $300,000 dollars and making thousands of shirts) for George Washington's Continental Army.

- Mary Ellen Pleasant was an indentured servant on Nantucket Island, an abolitionist leader before the Civil War and a real estate and food establishment entrepreneur in San Francisco during the Gold Rush, amassing a fortune of $30 million dollars which she used to defend Black people accused of crimes. Although she lost all her money in legal battles and died in poverty, she is recognized today as the " Mother of Civil Rights in California ."

- Ida B. Wells , born a slave in Mississippi in 1862, began her career as a teacher and spent her life fighting for Black civil rights as a journalist, anti-lynching crusader and political activist. She was 22 years-old in 1884 when she refused to give up her seat to a White man on a railroad train and move to a Jim Crow car, for which she was thrown off the train. She won her court case, but that judgement was later reversed by a higher court. She was a founder of National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored Women.

- Sylvia Mendez , the young girl at the center of the 1946 Mendez v. Westminster landmark desegregation case; Chief John Ross , the Cherokee leader who opposed the relocation of native peoples known as the Trail of Tears; and Fred Korematsu , who challenged the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, are discussed elsewhere in this book.

The INVESTIGATE and UNCOVER modules for this topic explore five more women and men, straight and gay, Black and White, who demonstrated political leadership throughout their lives. ENGAGE asks who would you consider are the most famous Americans in United States history?

Modules for this Standard Include:

- INVESTIGATE: Frances Perkins, Margaret Sanger, and Harvey Milk - Three Examples of Political Leadership

- UNCOVER: Benjamin Banneker, George Washington Carver, and Black Inventors' Contributions to Math, Science, and Politics

- MEDIA LITERACY CONNECTIONS: Celebrities' Influence on Politics

4.7.1 INVESTIGATE: Frances Perkins, Margaret Sanger, and Harvey Milk - Three Examples of Political Leadership

Three individuals offer ways to explore the multiple dimensions of political leadership and social change in the United States: one who was appointed to a government position, one who assumed a political role as public citizen, and one who was elected to political office.

- Appointed: An economist and social worker, Frances Perkins was appointed as Secretary of Labor in 1933, the first woman to serve in a President Cabinet.

- Assumed: Margaret Sanger was a nurse and political activist who became a champion of reproductive rights for women. She opened the first birth control clinic in Brooklyn in 1916.

- Elected: Harvey Milk was the first openly gay elected official in California in 1977. He was assassinated in 1978. By 2020, a LGBTQ politician has been elected to a political office in every state.

Frances Perkins and the Social Security Act of 1935

An economist and social worker, Frances Perkins was Secretary of Labor during the New Deal—the first woman member of a President’s Cabinet. Learn more: Frances Perkins, 'The Woman Behind the New Deal.'

Francis Perkins was a leader in the passage of the Social Security Act of 1935 that created a national old-age insurance program while also giving support to children, the blind, the unemployed, those needing vocational training, and family health programs. By the end of 2018, the Social Security trust funds totaled nearly $2.9 trillion. There is more information at the resourcesforhistoryteachers wiki page Frances Perkins and the Social Security Act .

Margaret Sanger and the Struggle for Reproductive Rights

Margaret Sanger was a women's reproductive rights and birth control advocate who, throughout a long career as a political activist, achieved many legal and medical victories in the struggle to provide women with safe and effective methods of contraception. She opened the nation's first birth control clinic in Brooklyn, New York in 1916.

Margaret Sanger's collaboration with Gregory Pincus led to the development and approval of the birth control pill in 1960. Four years later, in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), the Supreme Court affirmed women's constitutional right to use contraceptives. There is more information at the resourcesforhistoryteachers wiki page Margaret Sanger and Reproductive Rights for Women .

However, Margaret Sanger's political and public health views include disturbing facts. In summer 2020, Planned Parenthood of Greater New York said it would remove her name from a Manhattan clinic because of her connections to eugenics, a movement for selective breeding of human beings that targeted the poor, people with disabilities, immigrants and people of color.

Harvey Milk, Gay Civil Rights Leader

In 1977, Harvey Milk became the first openly gay man to be elected to public office in California by winning a seat on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, the city’s legislative body.

To win that election, Harvey Milk successfully built a coalition of immigrant, elderly, minority, union, gay, and straight voters focused on a message of social justice and political change. He was assassinated after just 11 months in office, becoming a martyr for the gay rights movement. There is more information at a resourcesforhistoryteachers wiki page, Harvey Milk, Gay Civil Rights Leader .

Suggested Learning Activities

- What personal qualities and public actions do you think make a person a leader?

- Who do you consider to be an effective leader in your school? In a job or organization in the community? In a civic action group?

- How can you become a leader in your school or community?

Online Resources for Frances Perkins, Margaret Sanger, and Harvey Milk

- Frances Perkins , FDR Presidential Library and Museum

- Her Life: The Woman Behind the New Deal , Frances Perkins Center

- Margaret Sanger Biography , National Women's History Museum

- Margaret Sanger (1879-1966) , American Experience PBS

- Harvey Milk Lesson Plans using James Banks’ Four Approaches to Multicultural Teaching , Legacy Project Education Initiative

- Harvey Milk pages from the New York Times

- Teaching LGBTQ History and Why It Matters , Facing History and Ourselves

- Official Harvey Milk Biography

- Harvey Milk's Political Accomplishments

- Harvey Milk: First Openly Gay Male Elected to Public Office in the United States, Legacy Project Education Initiative

4.7.2 UNCOVER: Benjamin Banneker, George Washington Carver, and Black Inventors' Contributions to Math, Science, and Politics

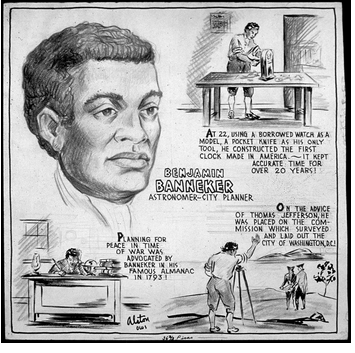

Benjamin banneker.

Benjamin Banneker was a free Black astronomer, mathematician, surveyor, author, and farmer who was part of the commission which made the original survey of Washington, D.C. in 1791.

Benjamin Banneker was "a man of many firsts" ( Washington Interdependence Council, 2017, para. 1 ). In the decades before and after the American Revolution, he made the first striking clock made of indigenous American parts, he was the first to track the 17-year locust cycle, and he was among the first farmers to employ crop rotation to improve yield.

Between 1792 and 1797, Banneker published a series of annual almanacs of astronomical and tidal information with weather predictions, doing all the mathematical and scientific calculations himself ( Benjamin Banneker's Almanac ). He has been called the first Black Civil Rights leader because of his opposition to slavery and his willingness to speak out against the mistreatment of Native Americans.

George Washington Carver

Born into slavery in Diamond, Missouri around 1864, George Washington Carver became a world-famous chemist and agricultural researcher. It is said that he single-handedly revolutionized southern agriculture in the United States, including researching more than 300 uses of peanuts, introducing methods of prevent soil depletion, and developing crop rotation methods.

A monument in Diamond, Missouri, of a statue showing Carver as a young boy, was the first ever national memorial to honor an African American ( George Washington Carver National Monument ).

Benjamin Banneker and George Washington Carver are just two examples from the long history of Black Inventors in the United States. Many of the names and achievements are not known today - Elijah McCoy, Granville Woods, Madame C J Walker, Thomas L. Jennings, Henry Blair, Norbert Rillieux, Garrett Morgan, Jan Matzeliger - but with 50,000 total patents, Black people accounted for more inventions during the period 1870 to 1940 than immigrants from every country except England and Germany ( The Black Inventors Who Elevated the United States: Reassessing the Golden Age of Invention , Brookings (November 23, 2020).

You can learn more details about these innovators at the African American Inventors of the 19th Century page on the resourcesforhistoryteachers wiki.

- Create 3D digital artifacts (using TinkerCad or another 3D modeling software ) that represent Banneker's and Carver's contributions to math, science, and politics.

- Bonus Points: Create a board (or digital) game that incorporates the 3D artifacts and educates others about Banneker and Carver.

- Using the online resources below and your own Internet research findings, write a people's history for Benjamin Banneker or George Washington Carver.

Online Resources for Benjamin Banneker, George Washington Carver and Black Inventors

- Benjamin Banneker from Mathematicians of the African Diaspora , University of Buffalo

- Mathematician and Astronomer Benjamin Banneker Was Born November 8, 1731 , Library of Congress

- Benjamin Banneker, African American Author, Surveyor and Scientist, resourcesforhistoryteachers wiki page

- George Washingto n Car ver , National Peanut Board

- George Washington Carver, State Historical Society of Missouri

- 16 Surprising Facts about George Washington Carver , National Peanut Board

4.7.3 ENGAGE: Who Do You Think Are the Most Famous Americans?

In 2007 and 2008, Sam Wineburg and a group of Stanford University researchers asked 11th and 12th grade students to write names of the most famous Americans in history from Columbus to the present day ( Wineburg & Monte-Sano, 2008 ). The students could not include any Presidents on the list. The students were then asked to write the names of the five most famous women in American history. They could not list First Ladies.

To the surprise of the researchers, girls and boys from across the country, in urban and rural schools, had mostly similar lists: Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, Harriet Tubman, Susan B. Anthony, and Benjamin Franklin were the top five selections. Even more surprising, surveys of adults from an entirely different generation produced remarkably similar lists.

The researchers concluded that a broad "cultural curriculum" conveyed through media images, corporate advertising, and shared information has a far greater effect on what is learned about people in history than do textbooks and classes in schools.

Media Literacy Connections: Celebrities' Influence on Politics

During elections, celebrities might endorse a political candidate or issue in hopes that their fans will follow in their footsteps. Oprah Winfrey's endorsement of Barack Obama for President in 2008 has been cited as the most impactful celebrity endorsement in history ( U.S. Election: What Impact Do Celebrity Endorsements Really Have? The Conversation , October 4, 2016).

Do celebrity endorsements make a real difference for voters? Researchers are undecided. In 2018, 65,000 people registered to vote in Tennessee after Taylor Swift (who had 180 million followers on Instagram) endorsed two Democratic Congressional candidates - one candidate won and the other lost. Swift's endorsement was followed by more than 212,000 new voter registrations across the country, mostly among those in the 18 to 24 age group. Perhaps what celebrities say has more impact on younger voters?

Can you think of some examples of celebrities who have shared their political views or endorsements on social media? Who are these celebrities? In what ways did they influence politics?

In these activities, you will analyze media endorsements by celebrities, and then develop a request (or pitch) to convince a celebrity to endorse your candidate for President in the next election.

- Activity 1: Analyze Celebrity Endorsements in the Media

- Activity 2: Request a Celebrity Endorsement for a Presidential Candidate

- As a class or with a group of friends, write individual lists of the 10 most famous or influential Americans in United States history.

- Explore similarities and differences across the lists.

- How many women or people of color were on the lists?

- Investigate the reasons for the similarities and differences.

- Returning to the Sam Wineburg study, "Why were Hispanic Americans, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and LGBTQ individuals left off the lists?" (see the full study here: " 'Famous Americans': The Changing Pantheon of American Heroes ")

- Research an individual's work and contributions, and in 200-250 words describe who they are, why you selected them, and what aspect of their work is important to the field. Within your description, include at least 2 links relevant to this individual ( Plan from Royal Roads University ).

Standard 4.7 Conclusion

Effective political leadership is an essential ingredient of a vibrant democracy. Unlike dictators or despots, effective leaders offer plans for change and invite people to join in and help to achieve those goals. Effective leaders work collaboratively and cooperatively, not autocratically. INVESTIGATE looked at three democratic leaders who entered political life in different ways: Frances Perkins, who was appointed to a Presidential Cabinet; Margaret Sanger, who assumed a public role as an advocate and activist; and Harvey Milk, who was elected to political office. UNCOVER reviewed the life and accomplishments of Benjamin Banneker and George Washington Carver. ENGAGE asked who people think are the most famous Americans in United States history.

The character of American democracy: Values-based leadership

Subscribe to governance weekly, jill long thompson jlt jill long thompson board chair and ceo, farm credit administration; former member of the u.s. house of representatives.

November 12, 2020

During the Watergate investigation, President Richard Nixon’s supporters would often argue that because they agreed with his policy positions, they could overlook his ethical and moral shortcomings. At that time a member of the U.S. House, Earl Landgrebe from my home state of Indiana, took this position to the extreme when he said, “Don’t confuse me with the facts” because he had made up his mind and would continue to support the president.

We hear a similar sentiment expressed today by supporters of President Donald Trump as they support his continuing claims that the election was fraudulent. This reflects a belief by some that ethical leadership is not important, or even relevant, so long as elected officials advance policies with which they agree. This kind of thinking is a threat to our democracy and our country.

Democracy is a form of government built on a foundation of ethical principles and it cannot survive unless those principles are honored and protected. Values matter because how we adopt laws is as important as the laws we adopt, and all of us are charged with protecting the self-governing principles that are the foundation of our great nation. Unethical leadership can undermine the democratic process, and even democracy itself.

Values-based leadership is essential to preserving and protecting democratic principles and there are at least three widely recognized moral virtues that are central to ensuring the governing process is democratic: truthfulness, justice, and temperance.

Truthfulness

When leaders lie, it is usually because the facts are not on their side and they do not want others to know the truth. They think the lie benefits them personally, usually at a cost to the rest of us. According to The Washington Post, The Fact Checker determined in August of this year that President Trump had made 22,000 false and misleading claims since taking office.

These untruths hurt our democracy because when our leaders deceive us, it becomes more challenging for the public to learn the facts. And that makes it more challenging for citizens to provide meaningful input. This undermines the all-important role of the citizenry in the policy-making process and it will most likely lead to the adoption of policies that are flawed because decisions based on falsehoods are usually bad decisions.

I came of age when the nation was deeply divided over our involvement in the Vietnam War and I very much wanted to believe that our political leaders were telling us the truth and that the anti-war protesters were wrong. But by the time I had completed my freshman year of college, critical content of the Pentagon Papers had been leaked to the press, confirming the very criticism the protesters were raising. Had the citizenry been told the truth, the course of history could have been changed for the better.

And today, we have lost tens of thousands of lives to COVID-19 that could have been saved had President Trump stated to the public what he said in his interviews with Robert Woodward.

Justice exists only when there is fairness in the process of governing. It requires those in leadership positions to consider the varied interests of all and to protect equality of participation. There must also be transparency.

Voter suppression of any kind is unjust and a threat to democracy. For example, how we draw congressional district maps influences the fairness of our elections. When congressional districts are construed in ways that concentrate voters of one political party in a smaller number of districts than is representative of the actual number of voters in that party, it can result in one party receiving a larger share of seats than votes.

As an example, in 2016 Republican candidates running for the U.S. House received 49.9 percent of the votes cast, while Democratic candidates received 47.3 percent of the votes cast. But Republicans won 55.2 percent, and Democrats won 44.8 percent of the seats in the House. In other words, Republicans got a “seats bonus.” Such gerrymandering suppresses the voices of voters across the country and clearly undercuts the most basic democratic principle of political equality.

Temperance is also central to democratic leadership. In democracy we do not each get our way, but we must respect the right we all have to work with our fellow citizens and address our challenges in a way that moves us forward as a people. Respect for the rights of others is essential. Good leaders do not divide and conquer, but rather, they bring people together through the democratic process. We are all in this together and we must all work together for the greater good of our nation.

Democracy is a principled form of government in which we all matter, and values-based leadership is central to preserving and protecting this great democratic experiment we call the United States of America.

Jill Long Thompson is a former Member of the U.S. House of Representatives, former Under Secretary at U.S.D.A., and former Board Chair and CEO at the Farm Credit Administration. She is a visiting scholar with the Ostrom Workshop at Indiana University Bloomington and has authored a book, The Character of American Democracy, published by Indiana University Press on September 15, 2020. The opinions expressed in this essay are hers and do not necessarily reflect those of Indiana University.

Related Content

Elaine Kamarck

September 24, 2019

Vanessa Williamson

October 17, 2023

Michael Hais, Doug Ross, Morley Winograd

February 1, 2022

Campaigns & Elections Presidency

Governance Studies

Center for Effective Public Management

May 31, 2024

Daniel S. Schiff, Kaylyn Jackson Schiff, Natália Bueno

May 30, 2024

Online Only

10:00 am - 11:00 am EDT

The Personal Characteristics of Political Leaders: Quantitative Multiple-Case Assessments

Cite this chapter.

- Dean Keith Simonton

Part of the book series: Jepson Studies in Leadership ((JSL))

1286 Accesses

3 Citations

A fundamental principle of political psychology is that psychology matters in the understanding of politics. Because both psychology and politics represent complex phenomena, with many manifestations, this tenet can adopt many different specific forms. Nonetheless, for the purposes of this chapter, two points stand out. First, an important subdiscipline of psychology deals with the personal characteristics of people. This subdiscipline is most commonly referred to as differential psychology, that is, the study of individual differences (Chamorro-Premuzic, Stumm, & Furnham, 2011). Second, a critical feature of politics is its leaders—the phenomenon of political leadership . Especially important are heads of state, whether presidents, prime ministers, monarchs, or dictators (Ludwig, 2002). These persons are reputed to have an exceptional influence, for good or ill, on their political system, whether democracy, autocracy, or oligarchy. Because political leaders remain persons, despite their exalted status in society, they too can vary in their personal characteristics. Furthermore, this variation can have consequences for their leadership, such as their ideology, decision making, or performance (Simonton, 1995). Hence, a central research topic must necessarily include the differential psychology of political leadership—the study of the personal characteristics of political leaders.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Ballard, E. J., & Suedfeld, P. (1988). Performance ratings of Canadian prime ministers: Individual and situational factors. Political Psychology, 9 , 291–302.

Article Google Scholar

Balz, J. (2010). Ready to lead on day one: Predicting presidential greatness from political experience. PS: Political Science and Politics, 43 , 487–492.

Google Scholar

Barber, J. D. (2008). The presidential character: Predicting performance in the White House (4th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bass, B. M., Avolio, B. J., & Goodheim, L. (1987). Biography and the assessment of transformational leadership world-class level. Journal of Management, 13 , 7–19.

Chamorro-Premuzic, T., Stumm, S., & Furnham, A. (Eds.) (2011). The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of individual differences . New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

Cohen, J. E. (2003). The polls: Presidential greatness as seen in the mass public: An extension and application of the Simonton model. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 33 , 913–924.

Copeland, G. W. (1983). When Congress and the president collide: Why presidents veto legislation. Journal of Politics, 45 , 696–710.

Costantini, E., & Craik, K. H. (1980). Personality and politicians: California party leaders, 1960–1976. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38 , 641–661.

Cox, C. (1926). The early mental traits of three hundred geniuses . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Craik, K. H. (1988). Assessing the personalities of historical figures. In W. M. Runyan (Ed.), Psychology and historical interpretation (pp. 196–218). New York: Oxford University Press.

Curry, J. L., & Morris, I. L. (2010). Explaining presidential greatness: The roles of peace and prosperity? Presidential Studies Quarterly, 40 , 515–530.

Davidson, J. R. T., Conner, K. M., & Swartz, M. (2006). Mental illness in U.S. presidents between 1776 and 1974: A review of biographical sources. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 194 , 47–51.

Deluga, R. J. (1997). Relationship among American presidential charismatic leadership, narcissism, and related performance. Leadership Quarterly, 8 , 51–65.

Deluga, R. J. (1998). American presidential proactivity, charismatic leadership, and rated performance. Leadership Quarterly, 9 , 265–291.

Donley, R. E., & Winter, D. G. (1970). Measuring the motives of public officials at a distance: An exploratory study of American presidents. Behavioral Science, 15 , 227–236.

Emrich, C. G., Brower, H. H., Feldman, J. M., & Garland, H. (2001). Images in words: Presidential rhetoric, charisma, and greatness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46 , 527–557.

Etheredge, L. S. (1978). Personality effects on American foreign policy, 1898–1968: A test of interpersonal generalization theory. American Political Science Review, 78 , 434–451.

Feldman, O., & Valenty, L. O. (Eds.). (2001). Profiling political leaders: Cross-cultural studies of personality and behavior . Westport, CT: Praeger.

Galton, F. (1869). Hereditary genius: An inquiry into its laws and consequences . London: Macmillan.

Book Google Scholar

Goethals, G. R. (2005). Presidential leadership. Annual Review of Psychology, 56 , 545–570.

Gottschalk, L. A., Uliana, R., & Gilbert, R. (1988). Presidential candidates and cognitive impairment measured from behavior in campaign debates. Public Administration Review, 48 , 613–619.

Hart, R. P. (1984). Verbal style and the presidency: A computer-based approach . New York: Academic Press.

Hermann, M. G. (1980a). Assessing the personalities of Soviet Politburo members. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 6 , 332–352.

Hermann, M. G. (1980b). Explaining foreign policy using personal characteristics of political leaders. International Studies Quarterly, 24 , 7–46.

Hermann, M. G. (2005). Assessing leadership style: A trait analysis. In J. D. Post (Ed.), The psychological assessment of political leaders (pp. 178–212). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Holmes, J. E., & Elder, R. E. (1989). Our best and worst presidents: Some possible reasons for perceived performance. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 19 , 529–557.

House, R. J., Spangler, W. D., & Woycke, J. (1991). Personality and charisma in the U.S. presidency: A psychological theory of leader effectiveness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36 , 364–396.

Kenney, P. J., & Rice, T. W. (1988). The contextual determinants of presidential greatness. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 18 , 161–169.

Knapp, R. H. (1962). A factor analysis of Thorndike’s ratings of eminent men. Journal of Social Psychology, 56 , 67–71.

Kynerd, T. (1971). An analysis of presidential greatness and “President rating.” Southern Quarterly, 9 , 309–329.

Lee, J. R. (1975). Presidential vetoes from Washington to Nixon. Journal of Politics, 37 , 522–546.

Ludwig, A. M. (1995). The price of greatness: Resolving the creativity and madness controversy . New York: Guilford Press.

Ludwig, A. M. (2002). King of the mountain: The nature of political leadership . Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky.

Maranell, G. M. (1970). The evaluation of presidents: An extension of the Schlesinger polls. Journal of American History, 57 , 104–113.

McCann, S. J. H. (1992). Alternative formulas to predict the greatness of U.S. presidents: Personological, situational, and zeitgeist factors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62 , 469–479.

McCann, S. J. H. (1995). Presidential candidate age and Schlesinger’s cycles of American history (1789–1992): When younger is better. Political Psychology, 16 , 749–755.

Miles, C. C., & Wolfe, L. S. (1936). Childhood physical and mental health records of historical geniuses. Psychological Monographs, 47 , 390–400.

Miller, N. L., & Stiles, W. B. (1986). Verbal familiarity in American presidential nomination acceptance speeches and inaugural addresses. Social Psychology Quarterly, 49 , 72–81.

Murray, R. K., & Blessing, T. H. (1983). The presidential performance study: A progress report. Journal of American History, 70 , 535–555.

Nice, D. C. (1984). The influence of war and party system aging on the ranking of presidents. Western Political Quarterly, 37 , 443–455.

Porter, C. A., & Suedfeld, P. (1981). Integrative complexity in the correspondence of literary figures: Effects of personal and societal stress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40 , 321–330.

Post, F. (1994). Creativity and psychopathology: A study of 291 world-famous men. British Journal of Psychiatry, 165 , 22–34.

Post, J. M. (Ed.). (2003). The psychological assessment of political leaders: With profiles of Saddam Hussein and Bill Clinton . Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Ridings, W. J., Jr., & McIver, S. B. (1997). Rating the presidents: A ranking of U.S. leaders, from the great and honorable to the dishonest and incompetent . Secaucus, NJ: Citadel Press.

Ringelstein, A. C. (1985). Presidential vetoes: Motivations and classification. Congress & the Presidency, 12 , 43–55.

Rohde, D. W., & Simon, D. M. (1985). Presidential vetoes and congressional response: A study of institutional conflict. American Journal of Political Science, 29 , 397–427.

Rubenzer, S. J., & Faschingbauer, T. R. (2004). Personality, character, & leadership in the White House: Psychologists assess the presidents . Washington, DC: Brassey’s.

Rubenzer, S. J., Faschingbauer, T. R., & Ones, D. S. (2000). Assessing the U.S. presidents using the revised NEO Personality Inventory. Assessment, 7 , 403–420.

Simon, A., & Uscinski, J. (2012). Prior experience predicts presidential performance. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 42 , 514–548.

Simonton, D. K. (1981). Presidential greatness and performance: Can we predict leadership in the White House? Journal of Personality, 49 , 306–323.

Simonton, D. K. (1983). Intergenerational transfer of individual differences in hereditary monarchs: Genes, role-modeling, cohort, or sociocultural effects? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44 , 354–364.

Simonton, D. K. (1984a). Leader age and national condition: A longitudinal analysis of 25 European monarchs. Social Behavior and Personality, 12 , 111–114.

Simonton, D. K. (1984b). Leaders as eponyms: Individual and situational determinants of monarchal eminence. Journal of Personality, 52 , 1–21.

Simonton, D. K. (1985). The vice-presidential succession effect: Individual or situational basis? Political Behavior, 7 , 79–99.

Simonton, D. K. (1986a). Dispositional attributions of (presidential) leadership: An experimental simulation of historiometric results. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 22 , 389–418.

Simonton, D. K. (1986b). Presidential greatness: The historical consensus and its psychological significance. Political Psychology, 7 , 259–283.

Simonton, D. K. (1986c). Presidential personality: Biographical use of the Gough Adjective Check List. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51 , 149–160.

Simonton, D. K. (1987). Presidential inflexibility and veto behavior: Two individual-situational interactions. Journal of Personality, 55 , 1–18.

Simonton, D. K. (1988). Presidential style: Personality, biography, and performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55 , 928–936.

Simonton, D. K. (1991a). Latent-variable models of posthumous reputation: A quest for Galton’s G . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60 , 607–619.

Simonton, D. K. (1991b). Personality correlates of exceptional personal influence: A note on Thorndike’s (1950) creators and leaders. Creativity Research Journal, 4 , 67–78.

Simonton, D. K. (1991c). Predicting presidential greatness: An alternative to the Kenney and Rice Contextual Index. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 21 , 301–305.

Simonton, D. K. (1992). Presidential greatness and personality: A response to McCann (1992). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63 , 676–679.

Simonton, D. K. (1995). Personality and intellectual predictors of leadership. In D. H. Saklofske & M. Zeidner (Eds.), International handbook of personality and intelligence (pp. 739–757). New York: Plenum.

Chapter Google Scholar

Simonton, D. K. (1996). Presidents’ wives and First Ladies: On achieving eminence within a traditional gender role. Sex Roles, 35 , 309–336.

Simonton, D. K. (1998). Mad King George: The impact of personal and political stress on mental and physical health. Journal of Personality, 66 , 443–466.

Simonton, D. K. (1999). Significant samples: The psychological study of eminent individuals. Psychological Methods, 4 , 425–451.

Simonton, D. K. (2001a). Kings, queens, and sultans: Empirical studies of political leadership in European hereditary monarchies. In O. Feldman & L. O. Valenty (Eds.), Profiling political leaders: Cross-cultural studies of personality and behavior (pp. 97–110). Westport, CT: Praeger.

Simonton, D. K. (2001b). Predicting presidential greatness: Equation replication on recent survey results. Journal of Social Psychology, 141 , 293–307.

Simonton, D. K. (2002). Intelligence and presidential greatness: Equation replication using updated IQ estimates. Advances in Psychology Research, 13 , 143–153.

Simonton, D. K. (2003). Qualitative and quantitative analyses of historical data. Annual Review of Psychology, 54 , 617–640.

Simonton, D. K. (2006). Presidential IQ, Openness, Intellectual Brilliance, and leadership: Estimates and correlations for 42 US chief executives. Political Psychology, 27 , 511–639.

Simonton, D. K. (2008). Presidential greatness and its socio-psychological significance: Individual or situation? Performance or attribution? In C. Hoyt, G. R. Goethals, & D. Forsyth (Eds.), Leadership at the crossroads: Vol. 1, Psychology and leadership (pp. 132–148). Westport, CT: Praeger.

Simonton, D. K. (2009a). The “other IQ”: Historiometric assessments of intelligence and related constructs. Review of General Psychology, 13 , 315–326.

Simonton, D. K. (2009b). Presidential leadership styles: How do they map onto charismatic, ideological, and pragmatic leadership? In F. J. Yammarino & F. Dansereau (Eds.), Research in MultiLevel Issues: Vol. 8. Multi-level issues in organizational behavior and leadership (pp. 123–133). Bingley, UK: Emerald.

Simonton, D. K. (2013). Presidential leadership. In M. G. Rumsey (Ed.), Oxford handbook of leadership (pp. 327–342). New York: Oxford University Press.

Simonton, D. K. (2014). Significant samples—not significance tests! The often overlooked solution to the replication problem. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 8 , 11–12.

Simonton, D. K., & Song, A. V. (2009). Eminence, IQ, physical and mental health, and achievement domain: Cox’s 282 geniuses revisited. Psychological Science, 20 , 429–434.

Smith, C. P. (Ed.). (1992). Motivation and personality: Handbook of thematic content analysis . Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Song, A. V., & Simonton, D. K. (2007). Studying personality at a distance: Quantitative methods. In R. W. Robins, R. C. Fraley, & R. F. Krueger (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in personality psychology (pp. 308–321). New York: Guilford Press.

Sorokin, P. A. (1926). Monarchs and rulers: A comparative statistical study. II. Social Forces, 4 , 523–533.

Spangler, W. D., & House, R. J. (1991). Presidential effectiveness and the leadership motive profile. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60 , 439–455.

Suedfeld, P. (2010). The cognitive processing of politics and politicians: Archival studies of conceptual and integrative complexity. Journal of Personality, 78 , 1669–1702.

Suedfeld, P., & Bluck, S. (1993). Changes in integrative complexity accompanying significant life events: Historical evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64 , 124–130.

Suedfeld, P., & Leighton, D. C. (2002). Early communications in the war against terrorism: An integrative complexity analysis. Political Psychology, 23 , 585–599.

Suedfeld, P., & Rank, A. D. (1976). Revolutionary leaders: Long-term success as a function of changes in conceptual complexity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34 , 169–178.

Suedfeld, P., Corteen, R. S., & McCormick, C. (1986). The role of integrative complexity in military leadership: Robert E. Lee and his opponents. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 16 , 498–507.

Suedfeld, P., Guttieri, K., & Tetlock, P. E. (2003). Assessing integrative complexity at a distance: Archival analyses of thinking and decision making. In J. M. Post (Ed.), The psychological assessment of political leaders: With profiles of Saddam Hussein and Bill Clinton (pp. 246–270). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Suedfeld, P., Tetlock, P. E., & Ramirez, C. (1977). War, peace, and integrative complexity. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 21 , 427–442.

Suedfeld, P., Tetlock, P. E., & Streufert, S. (1992). Conceptual/integrative complexity. In C. P. Smith (Ed.), Motivation and personality: Handbook of thematic content analysis (pp. 393–400). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Suedfeld, P., Wallace, M. D., & Thachuk, K. L. (1993). Changes in integrative complexity among Middle East leaders during the Persian Gulf crisis. Journal of Social Issues, 49 , 183–199.

Tetlock, P. E. (1981a). Personality and isolationism: Content analysis of senatorial speeches. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41 , 737–743.

Tetlock, P. E. (1981b). Pre-to postelection shifts in presidential rhetoric: Impression management or cognitive adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41 , 207–212.

Tetlock, P. E. (1984). Cognitive style and political belief systems in the British House of Commons. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46 , 365–375.

Tetlock, P. E., & Boettger, R. (1989). Cognitive and rhetorical styles of traditionalist and reformist Soviet politicians: A content analysis study. Political Psychology, 10 , 209–232.

Tetlock, P. E., Bernzweig, J., & Gallant, J. L. (1985). Supreme Court decision making: Cognitive style as a predictor of ideological consistency of voting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48 , 1227–1239.

Tetlock, P. E., Crosby, F., & Crosby, T. L. (1981). Political psychobiography. Micropolitics, 1 , 191–213.

Tetlock, P. E., Hannum, K. A., & Micheletti, P. M. (1984). Stability and change in the complexity of senatorial debate: Testing the cognitive versus rhetorical style hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46 , 979–990.

Thoemmes, F. J., & Conway, L. G., III (2007). Integrative complexity of 41 U.S. presidents. Political Psychology, 28 , 193–226.

Thorndike, E. L. (1936). The relation between intellect and morality in rulers. American Journal of Sociology, 42 , 321–334.

Thorndike, E. L. (1950). Traits of personality and their intercorrelations as shown in biographies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 41 , 193–216.

Watts, A. L., Lilienfeld, S. O., Smith, S. F., Miller, J. D., Campbell, W. K., Waldman, I. D., … Faschingbauer, T. J. (2013, October 8). The double-edged sword of grandiose narcissism: Implications for successful and unsuccessful leadership among U.S. presidents. Psychological Science , online first doi:10.1177/0956797613491970

Wendt, H. W., & Light, P. C. (1976). Measuring “greatness” in American presidents: Model case for international research on political leadership? European Journal of Social Psychology, 6 , 105–109.

Wendt, H. W., & Muncy, C. A. (1979). Studies of political character: Factor patterns of 24 U.S. vice-presidents. Journal of Psychology, 102 , 125–131.

Winter, D. G. (1973). The power motive . New York: Free Press.

Winter, D. G. (1980). An exploratory study of the motives of southern African political leaders measured at a distance. Political Psychology, 2 , 75–85.

Winter, D. G. (1987). Leader appeal, leader performance, and the motive profiles of leaders and followers: A study of American presidents and elections. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52 , 196–202.

Winter, D. G. (2002). Motivation and political leadership. In L. Valenty & O. Feldman (Eds.), Political leadership for the new century: Personality and behavior among American leaders (pp. 25–47). Westport, CT: Praeger.

Winter, D. G. (2003). Measuring the motives of political actors at a distance. In J. M. Post (Ed.), The psychological assessment of political leaders: With profiles of Saddam Hussein and Bill Clinton (pp. 153–177). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Winter, D. G., & Carlson, D. G. (1988). Using motive scores in the psychobiographical study of an individual: The case of Richard Nixon. Journal of Personality, 56 , 75–103.

Woods, F. A. (1906). Mental and moral heredity in royalty . New York: Holt.

Woods, F. A. (1909, November 19). A new name for a new science. Science, 30 , 703–704.

Woods, F. A. (1911, April 14). Historiometry as an exact science. Science, 33 , 568–574.

Woods, F. A. (1913). The influence of monarchs . New York: Macmillan.

Zullow, H. M., & Seligman, M. E. P. (1990). Pessimistic rumination predicts defeat of presidential candidates, 1900 to 1984. Psychological Inquiry, 1 , 52–61.

Download references

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Copyright information.

© 2014 George R. Goethals, Scott T. Allison, Roderick M. Kramer, and David M. Messick

About this chapter

Simonton, D.K. (2014). The Personal Characteristics of Political Leaders: Quantitative Multiple-Case Assessments. In: Goethals, G.R., Allison, S.T., Kramer, R.M., Messick, D.M. (eds) Conceptions of Leadership. Jepson Studies in Leadership. Palgrave Macmillan, New York. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137472038_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137472038_4

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Print ISBN : 978-1-137-47202-1

Online ISBN : 978-1-137-47203-8

eBook Packages : Palgrave Business & Management Collection Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

What makes a good political leader – and how can we tell before voting?

Senior Lecturer, School of Management, Massey University

Disclosure statement

Suze Wilson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Massey University provides funding as a member of The Conversation NZ.

Massey University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

For many people, voting is not just a right, it’s an act of civic duty. Even more than that, some voters base their decisions on what they believe best serves society as a whole, not what might personally advantage them.

The trick, of course, is how to exercise that vote in a responsible, informed and considered manner. Understanding the policies of different parties is obviously a key part of that, in which case resources such as Policy.nz and Vote Compass can be helpful.

But what of the individual characteristics of candidates and would-be leaders? What can the research tell us about what to look for? Given they are “actors” on the political “stage”, how do we evaluate their performance?

Of course, leadership isn’t a solo act. Many things determine what leaders can and can’t do. But what makes them tick – how their personality or character informs their actions – is enduringly fascinating . In fact, we know a lot about the beliefs, attitudes and behaviours that can help distinguish between good and bad leaders.

Confusing confidence with competence

Given “good” leadership is generally accepted as being both ethical and effective, it stands to reason “bad” leaders tend to fail on one or both counts. They either breach accepted principles of ethical or moral conduct, or they act in ways that detract from achieving desired results.

This distinction helps demystify leadership by highlighting that the qualities we least admire in others are also what scholars have long flagged as danger signs in leaders: arrogance, vanity, dishonesty, manipulation, abuse of power, lack of care for others, cowardice and recklessness.

Read more: Romantic heroes or ‘one of us’ – how we judge political leaders is rarely objective or rational

Notably, though, bad leaders can appear charming, confident and driven to achieve, despite seeking power for selfish reasons.

Numerous studies have identified the ways in which narcissists and what are sometimes called corporate psychopaths can be highly skilled at manipulating people into believing they’ve got what it takes, but will typically lead in destructive and dysfunctional ways. Other studies have shown the negative effects of “ Machiavellian ” leadership styles.

There is also a tendency to confuse competence – the actual knowledge and skills needed to perform a leadership role – with confidence. Good leaders tend to be relatively humble about their abilities and knowledge. This means they’re better listeners, more sensitive to others’ needs, and better able to collaborate effectively.

Read more: America's leaders are older than they've ever been. Why didn't the founding fathers foresee this as a problem?

Practical wisdom

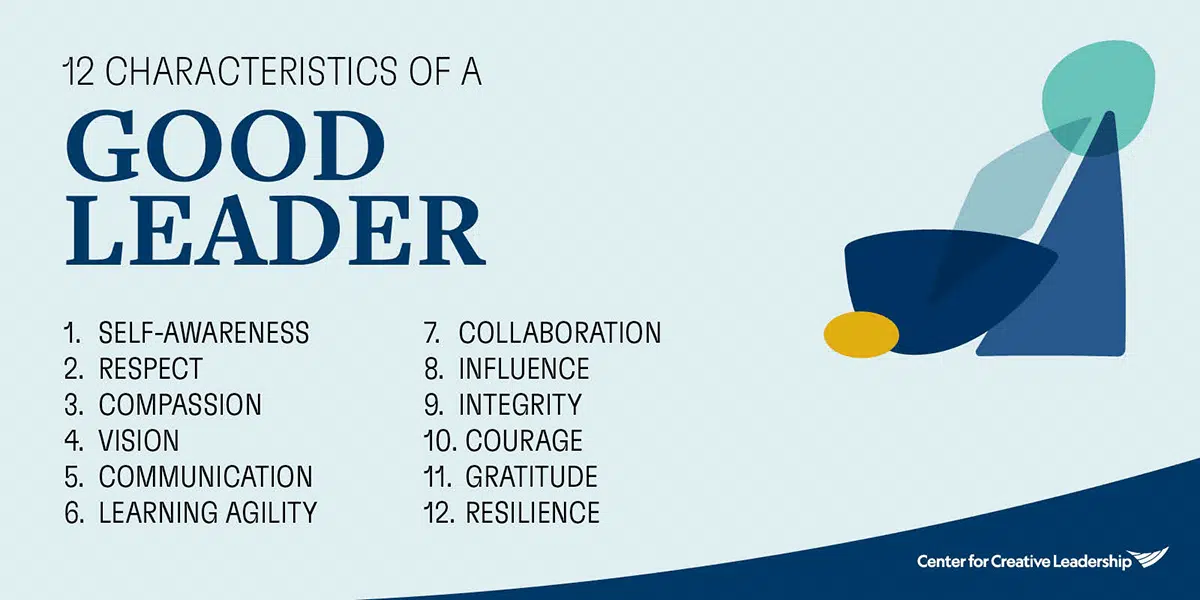

None of this fascination with leadership is new. The Classical Greek philosopher Aristotle argued good leaders possess a range of character virtues in the “middle ground” between what he called the “vices” of excess or deficiency. Courage, for example, is the virtuous mid-point between the vices of recklessness and cowardice.

The modern character virtues leadership researchers emphasise include humanity, humility, integrity, temperance, justice, accountability, courage, transcendence, drive and collaboration.

Each attribute helps a leader deal more effectively with some aspect of their role. Humanity, for instance, enables a leader to be considerate, empathetic and compassionate. Temperance helps them remain calm, composed, patient and prudent, even in testing circumstances.

Deployed together, these character virtues help foster sound judgment, insight, decisiveness – allowing a leader to calmly handle complex, unfolding challenges.

For Aristotle, the ideal leader could demonstrate what he called “phronesis”, or practical wisdom. This wasn’t necessarily about delivering perfect, painless solutions. Indeed, phronesis might mean adopting the least-worst option – which is often the case when dealing with the complex task of running a country.

There is also no single personality “type” most suited to good leadership. But studies indicate those who are proactive, optimistic, believe in themselves and can manage their anxieties stand a better chance. Empathy, a sense of duty and a commitment to upholding positive social values also underpin the attributes of good leaders.

Evaluating political leadership

No leader will be perfect. But each character or personality flaw impedes their capacity for wise judgment and dealing with the demands of their role. A wise leader, therefore, is one who has deep and accurate insight into their personal foibles and has strategies to mitigate for those tendencies.

Political leaders will obviously seek to present their policies, parties and themselves in a positive light, something known as “ impression management ”. This is where critical questioning and fact checking by journalists and experts can play a vital role.

Read more: NZ Election 2023: from one-way polls to threats of coalition ‘chaos’, it’s been a campaign of two halves

But gauging a leader’s “true” personality or character is more difficult. And we first need to be aware that our impressions and evaluations of leaders are not entirely driven by reason or logic.

Secondly, we can look for recurring patterns of behaviour in different situations over time. We should pay particular heed to behaviour under pressure, when it becomes more difficult to “mask” true feelings and motives.

Thirdly, we can consider the values that underpin a leader’s policies, who benefits from them, and what messages these convey to the community at large.

In the long run, a leader’s results bear consideration. But we need to assess these fairly, accounting for what was beyond their control. We should be mindful to avoid “ hindsight bias ” – the tendency to imagine events were predictable because we know they’ve occurred.

It should be no surprise that what constitutes good leadership has been studied and debated for thousands of years. Leaders have power and we’ve always wanted them to use it wisely. An informed voting choice makes that more likely.

- New Zealand

- NZ Election 2023

Head of School, School of Arts & Social Sciences, Monash University Malaysia

Chief Operating Officer (COO)

Clinical Teaching Fellow

Data Manager

Director, Social Policy

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Contentious Politics and Political Violence

- Governance/Political Change

- Groups and Identities

- History and Politics

- International Political Economy

- Policy, Administration, and Bureaucracy

- Political Anthropology

- Political Behavior

- Political Communication

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Philosophy

- Political Psychology

- Political Sociology

- Political Values, Beliefs, and Ideologies

- Politics, Law, Judiciary

- Post Modern/Critical Politics

- Public Opinion

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- World Politics

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Personality and political behavior.

- Matthew Cawvey , Matthew Cawvey Department of Political Science, University of Illinois

- Matthew Hayes , Matthew Hayes Department of Political Science, Indiana University

- Damarys Canache Damarys Canache Department of Political Science, University of Illinois

- and Jeffery J. Mondak Jeffery J. Mondak Department of Political Science, University of Illinois

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.221

- Published online: 25 January 2017

“Personality” refers to a multifaceted and enduring internal, or psychological, structure that influences patterns in a person’s actions and expressed attitudes. Researchers have associated personality with such attributes as temperament and values, but most scholarly attention has centered on individual differences in traits, or general behavioral and attitudinal tendencies. The focus on traits was reinvigorated with the rise of the Big Five personality framework in the 1980s and 1990s, when cross-cultural evidence pointed to the existence of the dimensions of openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and emotional stability. Studies have found these five trait dimensions to be highly heritable and stable over time, leading researchers to argue that the Big Five exert a causal impact on attitudes and behavior. The stability of traits also contrasts with more dynamic individual-level characteristics such as mood or with contextual factors in a person’s environment. Explanations of human decision-making, therefore, would be incomplete without attention to personality traits.

With these considerations in mind, political scientists have devoted an increasing amount of attention to the study of personality and citizen attitudes and behavior. The goal of this research program is not to claim that personality traits offer the only explanation for why some citizens fulfill the basic duties of citizenship, such as staying informed and turning out to vote, and others do not. Instead, scholars have studied personality in order to understand why individuals in the same economic and political environment differ in their political attitudes and actions. And accounting for the consistent influence of personality can illuminate the magnitude of environmental factors and other individual-level attributes that do shift over time.

Research on personality and political behavior has explored several substantive topics, including political information, attitudes, and participation. Major findings in this burgeoning literature include the following: (1) politically interested and knowledgeable citizens tend to exhibit high levels of openness to experience, (2) ideological liberalism is more prevalent among individuals high in openness and low in conscientiousness, and (3) citizens are more likely to participate in politics if they are high in openness and extraversion.

Although the personality and politics literature has shown tremendous progress in recent years, additional work remains to be done to produce comprehensive explanations of political behavior. Studies currently focus on the direct impact of traits on political attitudes and actions, but personality also could work through other individual-level attitudes and characteristics to influence behavior. In addition, trait effects may occur only in response to certain attitudes or contextual factors. Instead of assuming that personality operates in isolation from other predictors of political behavior, scholars can build on past studies by mapping out and testing interrelationships between psychological traits and the many other factors thought to influence how and how well citizens engage the world of politics.

- political behavior

- personality

- comparative politics

Connecting Personality and Citizen Politics

Most of us have taken personality tests online, tests that purport to reveal matters such as which movie star, musical performer, TV character, or breed of dog we are most like. We also observe personality differences in our friends. We know which acquaintances tend to be outgoing, which are the most responsible, and which dissolve into nervous wrecks under the slightest of pressures. We probably can rate ourselves on these same criteria. These examples demonstrate that we encounter personality differences on a daily basis and that we tend to possess an intuitive understanding of what personality is and why it is important.

It is a small step from these everyday brushes with personality to appreciating how and why social scientists study the possible impact of personality on people’s attitudes and behaviors. Personality psychologists and researchers in many other fields have directed considerable effort toward defining personality, cataloguing personality traits, determining how best to measure those traits, learning about the origins of differences in personality, and gauging the extent to which personality influences how people think and act. Political scientists have conducted some of this research. Comparative political behavior scholars recognize that many factors contribute to differences in how citizens engage the political world. Increasingly, these scholars acknowledge that people’s fundamental psychological characteristics—that is, their personalities—are among those factors.

The present article provides a broad case for the value of incorporating personality in research on comparative political behavior. In developing this case, we address three issues. First, we examine what personality is. In the past 25 to 30 years, consensus has emerged that personality traits are central components, but not the only components, of personality. Moreover, consensus exists that the bulk of personality trait structure can be represented with information on a relative handful of dimensions.

The most prominent framework, and the one that has received the most attention in political science, is the Big Five, or Five-Factor, approach. This framework focuses on the trait dimensions of openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. We explain the logic of this perspective, and discuss its relative strengths and limitations.

Second, we discuss why personality is thought to be important for political behavior. Applied research has linked variation in the Big Five trait dimensions to a staggering array of phenomena. Within the realm of citizen politics, the list includes everything from core political values to decisions about whether to display political yard signs. We recap some of the most important findings from this literature and explain why these effects are presumed to exist. Third, we offer some thoughts on how personality and politics might be studied most productively. Research in the past decade has identified links between personality traits and many aspects of comparative political behavior. Moving forward, it is important that we think about how best to integrate these insights with our broader accounts of the factors that influence political behavior. We argue that careful attention must be paid both to how personality is conceptualized and to how we theorize and test its role in politics.

As this article proceeds, we present the material in a nontechnical manner. Our goal is to provide a conceptual overview of personality and politics, not to discuss the intricacies of particular studies. That said, we include citations to both foundational works in this area and to illustrative examples of successful research. We hope that readers develop an understanding of what personality entails, why variation in personality traits may be consequential for political behavior, and how we can most fruitfully incorporate personality into our broader accounts of citizens’ political attitudes and actions.

What is Personality?

Research on political behavior seeks to understand why people think and act the way they do when it comes to politics: why they identify as liberals or conservatives, why they approve or disapprove of the president or parliament, why they did or did not vote in the most recent election, why they follow news about politics closely or not at all. Underlying most of this research is a concern with the quality of governance. Scholars hope that by understanding why people behave as they do, research can foster more capable citizens, ultimately bringing better elected officials and more representative policies.

Like all human behavior, political behavior is influenced by a complex array of factors. Some of these factors are external to the individual, such as the structure of a nation’s political system, or the occurrence of an economic downturn. Others are more personal, such as one’s level of intelligence or the decision to get married or change careers. We also can differentiate factors on the basis of whether they are relatively permanent and stable, or momentary and changing. An adult’s level of formal education and a nation’s selection of political institutions generally fall into the first category, whereas policy proposals and people’s emotional responses to political events are more likely to change over time.

With these distinctions in mind, most of us likely would assume that people’s personalities are best conceived of as personal attributes rather than as forces external to the individual. And they are stable and enduring rather than temporary and fleeting. Such an understanding of personality is consistent with what empirical research has shown. Appreciation for what this implies for whether and how personality may influence political behavior requires that we step back and consider both the meaning of personality and the causes of variation in personality across individuals.

Personality can be defined as a multifaceted and enduring internal, or psychological, structure that influences patterns of behavior (Mondak, 2010 ). Several aspects of this definition require explanation. First, personality is internal to the individual. We are not assigned our personalities at work or school; instead, they are part of us, and we carry them with us as we move from situation to situation. Importantly, conceiving of personality as an internal psychological structure implies that personality cannot be measured directly. We cannot crawl inside a person’s head and spot the extraversion. Instead, personality is measured indirectly, with information about the general patterns of thought and action assumed to be related to different components of personality. A second key point is that personality endures and is highly heritable. The heritability of personality means that much of the variation in personality across individuals is rooted in biology (e.g., Riemann, Angleitner, & Strelau, 1997 ). To a large extent we are born with the tendency to be extraverted, to be conscientious, and so on.

A great deal of research also shows that personality as measured in early childhood corresponds closely with personality measured later in life. Personality does change incrementally over the life cycle; for example, people tend to become more conscientious and emotionally stable with age. But these changes happen to virtually everyone. Thus, if one friend is more conscientious than the other at age 15, she likely still will be more conscientious at age 50, even if both friends are more conscientious at 50 than they were at 15. When psychologists measure personality in individuals at repeated points over the course of several years, they observe very high correlations (e.g., Costa & McCrae, 1988 ). Not only is personality itself stable over time, so too are its effects on political attitudes and behavior (Bloeser, Canache, Mitchell, Mondak, & Poore, 2015 ).

Beyond being internal to the individual and stable over time, two additional aspects of our definition of personality require elaboration. First, personality is multifaceted. The bulk of our discussion focuses on personality traits, the aspects of personality that have received the greatest scholarly attention. Personality traits are psychological characteristics of individuals, which means they are basic units of personality. Personality psychologists note that most of the thousands of adjectives used to describe people—terms such as punctual, gregarious, and polite—represent personality traits. Apart from traits, there is debate about personality’s components, but researchers agree that elements such as motives, values, and perhaps even intelligence, are part of personality (e.g., Caprara & Vecchione, 2013 ).

The last noteworthy aspect of our definition is that personality influences behavior. This, of course, is why scholars outside of the field of psychology care about personality. If personality influences behavior, then information about an individual’s personality may help us understand how the person acts, and with what success, in contexts such as school, the workplace, social relationships, and the world of politics. As is shown in the next section, a wealth of research has identified links between personality and virtually all matters of interest to students of comparative political behavior.

The Big Five

Because thousands of distinct personality traits have been identified (Allport & Odbert, 1936 ), trait psychology would be a hodgepodge without some sort of ordering framework. Personality psychologists have recognized this circumstance for decades and have proposed models of personality trait structure ranging in size from two or three trait dimensions to 16 or more. The Big Five, or Five-Factor, perspective emerged out of research conducted on behalf of the U.S. Air Force in the late 1950s (e.g., Tupes & Christal, 1958 ), although it was not until the late 1980s that this approach truly took off among personality psychologists (e.g., Costa & McCrae, 1988 ). The derivation of the Big Five was empirical rather than theoretical. Researchers examined how people—in the earliest work, Air Force officers—rated themselves on a large number of adjectives and then administered a statistical technique, factor analysis, to determine how many underlying dimensions best represented the data’s structure. A five-factor structure was obtained. Today, the Big Five trait typology enjoys a dominant role in the field, along with corresponding popularity as a vehicle for applied research in political science and many other disciplines.

The Big Five trait dimensions are openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. 1 We refer to these as trait dimensions rather than as traits because each is broad and encompasses several subsidiary facets. Researchers who make use of the Big Five contend that the framework captures the bulk of variation in personality trait structure. However, they do not assume that all aspects of personality, or even all personality traits, are represented by the Big Five. The Big Five approach thus constitutes a very good starting point for applied research on personality. But we should be aware of the possibility that, depending on our research questions, we might need to augment it with information on other traits. It is also possible that a framework superior to the Big Five eventually will emerge.

For students of comparative political behavior, an advantage of the Big Five is its cross-cultural applicability. Measures of the Big Five trait dimensions have been translated into dozens of languages, and researchers have administered these questionnaires throughout the world. More impressively, the same basic five-factor structure is observed in these applications (e.g., McCrae & Costa, 1997 ). This does not mean that personality structures are exactly the same everywhere. It may be, for example, that an unmeasured sixth or seventh trait dimension is prominent in a given nation. At the very least, the evidence shows that the dimensions of openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism are present in people across a wide array of language groups, cultures, and nations.

To illustrate average levels of the Big Five across countries, we refer to the 2010 AmericasBarometer. This survey fielded personality questions to residents of 24 countries in North America, Latin America, and the Caribbean. Respondents were asked two items for each of the Big Five. Their responses were logged, combined, and recoded to range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and emotional stability. 2 Figure 1 depicts the responses to the personality items in four AmericasBarometer countries: Brazil, Jamaica, Mexico, and the United States. The dots in the figure represent the average score for that trait in the country, and the bars indicate the level of variation as measured by plus or minus one standard deviation. We find that answers vary somewhat from country to country, with Jamaicans providing slightly higher average responses for each of the Big Five than residents in the other three countries. Nevertheless, the degree of variation across individuals within each country is much greater than variation in the average response from one country to the next. This has two implications for cross-national research. First, in terms of personality, individuals of all types are found in each nation. Absent such variation, we might have questioned the value of obtaining information on personality, as there is little or no analytical benefit in studying “variables” that do not vary. Second, because there is considerably more variation within nations than between them, data on the Big Five facilitate the study of individual-level similarities and differences that transcend national boundaries.

Figure 1. The Big Five in Four Countries.

Note : Dots represent the average score for that trait in the respective country. Bars indicate the level of variation in the country (plus or minus one standard deviation).

We now turn to a brief discussion of each trait dimension.

Openness refers to a curiosity about the world and a corresponding willingness to learn about different perspectives and to participate in new activities. Individuals scoring high in openness to experience are described as being imaginative, analytical, and creative. Like all aspects of personality, openness is linked to behaviors we might view as desirable and others we might see as undesirable. For example, people with high levels of openness seek out information and thus tend to be well-informed (Mondak, 2010 ). However, these same individuals often show a heightened willingness to take risks, such as with respect to the consumption of drugs and alcohol (Booth-Kewley & Vickers, 1994 ).

Conscientiousness is a trait dimension that includes the disposition to be dependable, organized, and punctual and a volitional tendency to be hardworking and industrious. People with high levels of conscientiousness typically excel in domains such as school and the workplace (Barrick & Mount, 1991 ). Conscientiousness also is related to physical fitness, maintaining a healthy lifestyle, and the avoidance of personal risk (Booth-Kewley & Vickers, 1994 ).

Extraversion is the personality trait dimension with the longest history in academic research, with discussion of extraversion tracing back a full century. Although numerous other trait typologies preceded the emergence of the Big Five, nearly all have reserved a spot for extraversion (e.g., Eysenck & Wilson, 1978 ). Individuals scoring high in extraversion exhibit an inherent sociability. They are bold, outgoing, and talkative. Extraversion is associated with a preference for, and success in, activities that involve interaction with others (e.g., Barrick & Mount, 1991 ).

Agreeableness is the fourth Big Five trait dimension. Like extraversion, agreeableness is seen primarily in the context of individuals’ interactions with others. Adjectives used to represent those scoring high in agreeableness include “warm,” “kind,” “sympathetic,” and “generous.” High levels of agreeableness correspond with success in interpersonal relationships and collaborative ventures and with attachments to others such as those manifested in feelings of sense of community and trust (e.g., Lounsbury, Loveland, & Gibson, 2003 ).

Neuroticism , the final Big Five trait dimension, is also sometimes referred to by its opposite, emotional stability. Terms such as “tense” and “emotional” are used to represent neuroticism, whereas terms such as “calm” and “relaxed” indicate emotional stability. Like extraversion, research on neuroticism dates back a full century and explores a number of outcomes. High levels of neuroticism correspond with an increased risk of depression, whereas low levels correspond with certain career choices, such as becoming a surgeon or member of the clergy (Francis & Kay, 1995 ).

Research abounds on the meaning and significance of personality and on personality frameworks such as the Big Five. Given the enormity of the research record, we have presented a necessarily brief and simplified overview. This introduction hints at why political scientists increasingly consider personality when attempting to understand variation in people’s political attitudes and behaviors.

Why Study Personality and Political Behavior?

Differences in people’s personalities are hardly the only sources of variation in political behavior. To the contrary, we know that patterns of political behavior vary with demographic attributes, socioeconomic status, aspects of the social context, media exposure, enduring values and political orientations, and more. With that in mind, what is to be gained by adding personality to the mix? What would factoring in personality teach us about the bases of political behavior, and what, if anything, might attention to personality reveal about all of the other factors thought to matter for how citizens engage the political world? This section reviews what empirical research has shown regarding relationships between the Big Five and the sorts of variables of interest to students of comparative political behavior.