- Find Articles in Other Languages

- Find Books & Videos in Other Languages

Finding Articles in Other Languages

Finding articles in specific languages is very similar to finding articles in English, but with some key changes:

- Use search terms in your target language. For example, to find articles about climate change in Spanish, try calentamiento global, ensuciamiento de aire, or gases de invernadero.

- Limit your search results to your target language using the database's filters, if any. These filters might appear at the beginning of your search, on the advanced search page, or on the results page. See the examples below. The example on the left is from JSTOR, showing the language filter on its advanced search page. The example on the right is from OneSearch, showing the language filter, which is available on the All Filters menu from the results page.

NOTE : Our databases don't translate articles. These search tips can only find articles that were originally written in your target language.

In addition to OneSearch (see below), we recommend the following databases for finding articles in foreign languages.

Partially peer reviewed. Some full-text content.

Partially peer reviewed. Some full-text content. Open access.

Peer reviewed. Some full-text content.

To use OneSearch, go to the UVU Fulton Library Homepage link below. OneSearch is the main search box on the page. Enter search terms into the box, then hit enter or click the magnifying glass. Once your search runs, you can filter your results clicking the All Filters button that appears below the search box.

- UVU Fulton Library Homepage The library's main page. Access OneSearch, help options, library hours, and more.

Library Help

- Call : 801.863.8840

- Text : 801.290.8123

- In-Person Help

- Email a Librarian

- Make an Appointment

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Find Books & Videos in Other Languages >>

- Last Updated: Apr 30, 2024 1:44 PM

- URL: https://uvu.libguides.com/languages-guide

Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

Research Papers in Foreign Languages

As the simultaneously dreaded and much-awaited Dean’s Date comes around again, many of us find ourselves writing final research papers for our foreign language classes. Conducting research and writing a long paper in a language in which we are not fully fluent is both harder and very different from writing one in our native language. Personally, I have spent the past few days writing a paper for French 307 discussing the ethics of weapons development, a fairly technical subject which presented a number of challenges.

The first challenge was conducting the research in French. As a beginner in this area, I found it difficult to launch directly into Google.fr searches for exclusively French texts. I was lacking the relevant technical vocabulary for my subject, so I simply did not know what keywords to search and oftentimes could not entirely understand the papers I found. After floundering a bit, I found that the best way to go about the research was to alternate between French and English sources—initially, I might read an English source to get an idea of what I was looking for, and then I would search for a similar one in French. Reading the two in parallel allowed me to develop a better understanding of the French vocabulary required. As I built up my knowledge, I was able to use fewer and fewer English sources to guide me. While I still relied on English sources to give me ideas for what I wanted more in-depth information on (after all, there aren’t too many articles in French about US Department of Defense projects), I found myself using them just as a jumping-off point, rather than as a crutch to help me understand the French sources.

The next challenge was writing the actual paper. Most people in the early stages of learning a foreign language will simply write the paper in their native language and then translate it directly. However, as we reach proficiency, we tend to become more comfortable writing directly in the language. Nevertheless, this is no easy task, even if it produces better results than a direct translation. As such, it is very important to write a good outline—in either language—so that you have an organized plan for your writing. Then, it is a matter of slowly piecing together the general concept of what you want to say and the vocabulary and nuances of the foreign language that most accurately convey your message. It is important not to adhere too strictly to a certain phrasing you might have in your head, as this may not directly translate in the other language and will instead obscure the meaning you wish to convey. Rather, construct the message first, and then figure out, directly in the foreign language, how you can best describe it.

Writing a paper in another language is challenging, but ultimately extremely rewarding. It forces you to expand your vocabulary and comprehension in that language, and to think more creatively and flexibly about your own writing. It is an exercise that can improve your writing in your native language as well, as you learn to find more creative and subtle ways to express a message. The skills learned through this process can be very useful in the future—you never know when the perfect source for your topic might be in another language, and mastering the ability to find and comprehend foreign language sources now can help you tremendously in the future.

–Alexandra Koskosidis, Engineering Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 08 March 2023

Changing perceptions of language in sociolinguistics

- Jiayu Wang 1 ,

- Guangyu Jin 1 , 2 &

- Wenhua Li 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 91 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

7037 Accesses

1 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Language and linguistics

This paper traces the changing perceptions of language in sociolinguistics. These perceptions of language are reviewed in terms of language in its verbal forms, and language in vis-à-vis as a multimodal construct. In reviewing these changing perceptions, this paper examines different concepts or approaches in sociolinguistics. By reviewing these trends of thoughts and applications, this article intends to shed light on ontological issues such as what constitutes language, and where its place is in multimodal practices in sociolinguistics. Expanding the ontology of language from verbal resources toward various multimodal constructs has enabled sociolinguists to pursue meaning-making, indexicalities and social variations in its most authentic state. Language in a multimodal construct entails the boundaries and distinctions between various modes, while language as a multimodal construct sees language itself as multimodal; it focuses on the social constructs, social meaning and language as a force in social change rather than the combination or orchestration of various modes in communication. Language as a multimodal construct has become the dominant trend in contemporary sociolinguistic studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Comparing the language style of heads of state in the US, UK, Germany and Switzerland during COVID-19

The art of rhetoric: persuasive strategies in Biden’s inauguration speech: a critical discourse analysis

How Spanish speakers express norms using generic person markers

Introduction.

This article will review a range of sociolinguistic concepts and their applications in multimodal studies, in relation to how language has been conceptualized in sociolinguistics. While there are reviews of specific areas of research in sociolinguistics, including prosody and sociolinguistic variation (Holliday, 2021 ), language and masculinities (Lawson, 2020 ), and Language change across the lifespan (Sankoff, 2018 ), there have been few reviews works set out to delineate the most fundamental ontological questions in sociolinguistic studies; that is, what is and what constitutes language? How do sociolinguists perceive language in relation to other semiotic resources that are part and parcel of social meaning-making and social interaction? Relevant discussions are scattered in passing mainly in the introductory sections of various sociolinguistic works, such as Blommaert ( 1999 ), García and Li ( 2014 ) and Makoni and Pennycook ( 2005 ). However, there have not been review articles systematically dealing with the changing perceptions of language in sociolinguistic studies.

These issues are worthwhile to pursue in the sense that though sociolinguistics studies language, yet no reviews were done regarding what on earth constitutes language, especially in relation to a wider range of semiotic resources. What even makes the review more imperative is that in an increasingly globalized and high-tech world, linguistic practices are complicated by the super-diversity of ethnic fluidity, communications technologies, and globalized cross-cultural art.

Centring on the ontological perception of language in sociolinguistics, this article consists of five sections. After the “Introduction” section, the next section will review traditional (socio)linguistic perceptions of language as written or spoken signs or symbols that people use to communicate or interact with each other. The next section will review representative sociolinguistic approaches that place language in multimodal settings which involve the relationship between language and other semiotic resources. They are categorized as the conceptualizations of “language in multimodal construct” and “language as multimodal construct”. These conceptualizations share the common feature that language is not researched merely in terms of written and spoken signs and symbols, but it is probed (1) in relation to its multimodal contexts and (re)contextualization (regarding language in multimodal construct), (2) in terms of its own materiality and spatiality, and linguistic representations of multimodality, for instance, social (inter)action and “smellscapes” (Pennycook and Otsuji, 2015a ) which are in turn conflated with linguistic features (regarding language as multimodal construct). The penultimate section and the last section will present a critical reflection and a conclusion of the review, respectively.

Language as written and spoken signs and symbols

What constitutes language(s)? Saussure ( 1916 ) distinguishes between langue and parole. The former refers to the abstract, systematic rules and conventions of the signifying system, while the latter represents language in daily use. Chomsky ( 1965 ) refers to them as competence (corresponding to langue) and performance (corresponding to parole). Chomsky ( 1965 ) assumes that performance is bound up with “grammatically irrelevant conditions as memory limitations, distractions, shifts of attention and interest, and errors (random or characteristic) in applying his knowledge of this language in actual performance” (Chomsky, 1965 , pp. 3–4). He advocates that the agenda of linguistics should be the study of competence of “an ideal speaker-listener, in a completely homogeneous speech-community, who knows its (the speech community’s) language perfectly” (in brackets original). His conception of the ideal language rules out the “imperfections” arising from the influences of social or pragmatic dimensions in real language use. This can be seen as the conception of language as innate human competence. By contrast, constructionists have argued that language cannot be separated from the societal and social domain; social reality is constructed through languages (Berger and Luckmann, 1966 ), and linguistics should take social dimensions into account, as shown by Systemic Functional Linguistics developed by Halliday. These approaches to language studies, nevertheless, do not pay much attention to the ontological issues of language or linguistics concerning what constitutes language, whether languages can be separated from each other, and whether there are different conceptions of language(s).

Sociolinguistics, taking as its departure an interdisciplinary attempt to be the sociology regarding linguistic issues or linguistics regarding sociological issues, faces the ambivalent positioning of whether it should be sociologically oriented (that is, more explanatory) or linguistically oriented (that is, more descriptive) (Cameron, 1990 ). Also, there are contentions regarding whether more attention should be paid to epistemically linguistic minutiae (as in conversation analysis or CA), or to the macro-social interpretation of ideology not necessarily dependent on the evident orientation of the participants (as in critical discourse analysis, or CDA), as debated in Blommaert ( 2005 ) and Schegloff ( 1992 , 1998a / 1998b , 1999 ). As such, more sociolinguists than linguists in other disciplines are concerned with the ontology of language regarding its nature and its relation with broader social structures. In other words, such concerns can, firstly, justify the identity of sociolinguistics being either a branch of sociology, or linguistics, or even more broadly, anthropology. They can also delineate the contour of the macro vis-à-vis micro research subjects: are languages seen as separate systems, or inseparable but relatively fixed systems or an integrated construction in relation to their social dimensions of power, ideology and hegemony?

Such ontological concerns are important, because different approaches to research may be engendered accordingly. For instance, variational sociolinguistics is concerned with the linguistic differences within a language (standard language vis-à-vis its variations in dialects) and examines how these differences are linked to social aspects of linguistic practices, such as gender and social status. These differences within a certain category of language may be placed in the changing situations of various language communities or areas (e.g., Labov, 1963 , 1966 ), or in contextualized pragmatic situations (Agha, 2003 ; Eckert, 2008 ). Assumptions of separable or separate languages may be well-encapsulated in the works regarding language ideology and linguistic differentiation, such as the studies by Kroskrity ( 1998 ), Irvine and Gal ( 2000 ), as well as considerable other works on bilingualism or multilingualism. These works treat language as belonging to different standard systems (e.g., English, French, German, and so on) and can be pursued by “enumerating” these categories. In other words, these standard language systems are seen as having clear boundaries between them, and language can be researched by attributing different linguistic resources to (one of) these systems. The stance of the inseparability of language problematizes the enumeration of languages, by discrediting their explanatory potential in linguistic practices. In pedagogical contexts, transnational students are found using language features beyond the boundaries of language systems (Creese and Blackledge, 2010 ; Lewis et al., 2012 ). In the context of youth or urban culture, there are loosely fixed assumptions between language and ethnicity (Maher, 2005 ; Woolard, 1999 ). In some globalized contexts, new communications technologies as well as globalization itself are changing the traditional power structure in linguistic practices (Jacquemet, 2005 ; Jørgensen, 2008 ; Jørgensen et al., 2011 ). Furthermore, Makoni and Pennycook ( 2005 ), by advocating the disinvention of languages, problematize the process of “historical amnesia” (Makoni and Pennycook, 2005 , p. 149) of bi- and multilingualism, and their tradition of enumerating languages which reduces sociolinguistics to at best a “pluralization of monolingualism” (Makoni and Pennycook, 2005 , p. 148). However, this does mean that languages cannot be probed as standard categories. It holds a more intricate stance: on the one hand, it problematizes the separation of languages, as language is characterized by fluidity in multi-ethnic settings; on the other hand, it assumes the fixity of the relationship between a given (standard) language and its corresponding identity, ethnicity, and other societal factors (Otsuji and Pennycook, 2010 ); fluidity and fixity, however, are not binary attributes that exclude each other; they coexist, mutually influence each other in real-life linguistic practices. By the same token, Blackledge and Creese ( 2010 ) and Martin-Jones et al. ( 2012 ) also hold a dynamic view on language and identity: while language functions as “heritage” (see Blackledge and Creese, 2010 , pp. 164–180) and the positioning or maintenance of national identity, the bondage, however, frequently loosens as it is always contested, resisted and “disinvented” (Makoni and Pennycook, 2005 ). Table 1 illustrates three kinds of sociolinguistic conceptualizations of language.

The above discussion briefly delineates how contemporary sociolinguistic studies attempt to capture the complex ways in which the notion of language is construed, resisted or reinvented in and through practices. Most of these approaches are based on the traditional assumption of language as written signs and symbols in its verbal forms. Other forms of resources are generally seen as contexts where these verbal signs and symbols take place. They are contextual facets that contribute to the ideological and sociological corollary of language use, but they are not seen as ontological components in linguistics. Later developments, which integrate multimodal studies into sociolinguistics, show differing stances regarding the ontology of language, as shown in the next section.

Language in vis-à-vis as multimodal construct

Jewitt ( 2013 , p. 141) defines multimodality as “an inter-disciplinary approach that understands communication and representation to be more than about language”. This should be seen as a definition oriented toward social semiotics, in which different semiotic resources are seen as various modes of representation or communication through semiosis. For a sociolinguistic version of the definition, we prefer to interpret it as language in vis-à-vis as a multimodal construct. By using the word “construct”, we would like to point out that multimodality or multimodal conventions enter into sociolinguistic studies because they are socially constructed; that is, sociolinguists research these multimodal dimensions because they are semiotic resources and practices which are constructed by social subjects with power, manipulation and ideology. They are not neutral resources by which people communicate information or by which the process of meaning-making, or semiosis, is realized. Instead, they are a social construct that constitutes the type of Foucauldian knowledge in which sociological power and ideology lie at the core. In this sense, the notions, frameworks, and approaches that we discuss as follows are socially critical in nature and are predominantly related to socially constructed ideologies such as hegemony, power, and identity. As Makoni and Pennycook ( 2005 ) note, languages are “invented” by the dominant (colonial) groups through classification and naming in history; they are not neutral practices and they are constructed and invested with ideologies, power and inequality. Sociolinguistics thus needs a historically critical perspective. In fact, since its birth, sociolinguistics has been a discipline focusing on language use in relation to socially critical issues, such as gender, race, class and politics. This focus can date back as early as Labov’s ( 1963 , 1966 ) ethnographical research on variations of English on the island of Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts and in New York City. The sound change or phonetic features are studied in relation to ethnicity, social stratification and class. Agha ( 2003 ) and Eckert ( 2008 ) also probe the phonetic features or regional change of variations in relation to ethnicity and social and economic status.

In fact, the above-mentioned concerns of sociolinguistics are also consistent with CDA (see Wang and Jin, 2022 ; Wang and Yang, 2022 ), especially multimodal critical discourse analysis (MCDA), which also contributes to the research trend in terms of language in multimodality. Kress and van Leeuwen ( 1996 ) postulates a set of visual grammar based on systemic functional grammar. Machin ( 2016 ) and Machin and Mayr ( 2012 ) and other scholars have also adopted MCDA in various types of discourse. Semiotic resources other than language are analysed to reveal the social construct of power, ideology, and inequality in relation to verbal resources (Wang, 2014 , 2016a , 2016b ). Language in the multimodal construct in sociolinguistics is quite similar to the social semiotic and critical discourse approach to multimodality: language is seen as one type of resource, amongst other non-language resources (visual, aural, embodied, and spatial) in the meaning-making process. The difference lies in that sociolinguistic approaches toward language in multimodality have much more focus on social interaction, power and ideology and their research frequently includes ethnographical data and observations. Language as a multimodal construct, by contrast, sees language as a more integral part of multimodal resources, and vice versa; less distinct boundaries are seen as existing between languages and non-languages. These two trends of conceptions are discussed below.

Language in multimodal construct

To place language studies in the multimodal construct is not a new practice in sociolinguistics. Agha ( 2003 , p. 29) analyses the Bainbridge cartoon, treating accent not as “object of metasemiotic scrutiny”, but as an integral element in “the social perils of improper demeanour in many sign modalities” such as dress, posture, gait and gesture. His discussion demonstrates how language studies can be embedded in a larger multimodal scope. Language is contextualized by its peripheral multimodal paralinguistic sign systems. In Eckert ( 2008 , p. 25), the process of “bricolage” (Hebdige, 1984 ), in which “individual resources can be interpreted and combined with other resources to construct a more complex meaningful entity”, is linked to the style and language variations which reflect social meaning. She gives examples of how the clothing of students at Palo Alto High School affords them certain types of styles to convey social meaning. Eckert ( 2001 ), Coupland ( 2003 , 2007 ) and other scholars’ research represent the “third-wave” sociolinguistic studies, which see the use of variation in terms of personal and social styles (Eckert, 2012 ). Language and other semiotic resources constitute a stylistic complex that makes social meaning and constructs social styles and identities together. Goodwin ( 2007 ) extensively encompasses multimodal interaction in the examination of participation, stance and affect in a “homework” interaction between a father and his daughter, where gaze, gesture, and the spatial environment are taken into account. Goodwin’s research is partly premised on Bourdieu’s ( 1991 , pp. 81–89) associating bodily hexis with habitus , which is also a notion that is multimodal in itself. The deployment of different bodily modes in different contexts of participation (such as homework, archaeology, and surgery) depends on conventions of various social practices or their respective habitus .

Research regarding language in multimodal construct shares some common ground with the social semiotic approach towards multimodality. First, in communication, there are different modes of resources or semiotic types that convey social meaning and embed ideology. Second, these resources consist of language and “non-language”: the former being written or spoken signs and symbols that social actors use to communicate, and the latter being visual, aural, or embodied ones in that language are situated. Third, meaning-making is done through the orchestration of these resources.

In contrast to social semiotic approaches, with an anthropology-oriented concern, language in the multimodal construct as a sociological and sociolinguistic approach usually bases itself on ethnographical observations of social interaction. Language is seen as a component in social interactional discourse; other semiotic modes or resources are also important resources through which language use is contextualized. To be more specific, language in multimodal construct shows concerns with language as one type of semiotic resource that is placed in multimodal contexts in the following aspects:

First, meaning-making through other resources is seen as “add-ons” to that of language. In other words, language indexes social meaning and ideology in collaboration with other types of resources. An example is Agha’s ( 2003 ) analysis of the Bainbridge cartoon in which clothes, demeanour, and even body shape work in collaboration with accent in conveying register and social status. Second, language as one type of social meaning-making resource can be conceptualized in relation to the meaning-making process of other resources. For example, the process of “bricolage” is probed in relation to variations with their indexed styles and social categorization in terms of “gender and adolescence” (Eckert, 2008 , p. 458). This concept is used to offer clues regarding how “the differential use of variables constituted distinct styles associated with different communities of practice” (Eckert, 2008 , p. 458). Third, language is one of the communicative modes in social interactional discourse. It does not necessarily take the central role, because other types of resources, such as gestures, gaze, and the environment where these actions take place, jointly constitute the social meaning-making process. This can be best encapsulated in Goodwin’s ( 2007 ) analysis of the “homework” interaction between a father and his daughter. In this quite mundane interactional discourse, the father uses different embodied actions to negotiate different moral and affective stances through the “homework interaction” with his daughter. Conversation as a linguistic resource plays a role in the interaction, while embodied actions are key factors in affecting these stances.

Language as a multimodal construct

A slightly different approach to studies of language in multimodal contexts is to view it as a multimodal construct: either in the way that language is considered as autonomously constituting the semiotic texture (e.g., in the art form of the “text art” where text is also seen as picture) or in the way that some traditionally assumed extra-linguistic modes are considered as special forms or dimensions of language. This trend of research includes recent studies on language in space, social interactional multimodal discourse analysis, and new concepts or conceptualizations of language in society, as discussed below.

Language in space: semiotic landscape, place semiotics, and discourse geography

Jaworski and Thurlow ( 2010 ) review the notion of spatialization , that is, the semiotics and discursivity of space (Jaworski and Thurlow, 2010 ), and the extension of the notion of the linguistic landscape. By so doing, they frame the concept of semiotic landscape as encapsulating how written discourse interacts with other multimodal discursive resources with blurring boundaries in between.

In their opinion, space is “not only physically but also socially constructed, which necessarily shifts absolutist notions of space towards more communicative or discursive conceptualizations” (Jaworski and Thurlow, 2010 , p. 7). Sociological research on space thus is more oriented toward spatialization, “the different processes by which space comes to be represented, organized and experienced” (Jaworski and Thurlow, 2010 , p. 6). This spatialization—as represented discursively—is intrinsically multimodal:

Echoing the sentiments of Kress and van Leeuwen quoted at the start of this chapter, Markus and Cameron argue that ‘[b]uildings themselves are not representations’ (p. 15), but ways of organizing space for their users; in other words, the way buildings are used and the way people using them relate to one another, is largely dependent on the spoken, written and pictorial texts about these buildings… Architecture and language (spoken and written) may then form an even more complex, multi-layered landscape (or cityscape) combining built environment, writing, images, as well as other semiotic modes, such as speech, music, photography, and movement…(Jaworski and Thurlow, 2010 , pp. 19–20)

The “spatial turn” (Jaworski and Thurlow, 2010 , p. 6) in sociolinguistics thus adds the analytical dimensions of multimodal resources to the traditional concept of the linguistic landscape. Written language itself does convey social meaning and ideologies, while it is situated in materiality (the materials it is written on) and spatiality (the places where it appears). The concept of the semiotic landscape blurs the traditional boundary between language and non-language.

Different from social semiotic approaches towards multimodality, researchers of semiotic landscape pay predominant attention to the “metalinguistic or metadiscursive nature of ideologies” (Jaworski and Thurlow, 2010 , p. 11). In Kallen’s words, the concept of semiotic landscape starts from the assumption that “sinage is indexical of more than the ostensive message of the sign”. (Kallen, 2010 , p. 41); signage indexes ideologies that are embedded in, or indicated by, different types of space or spatiality: city centre, tourist places, districts and so on. Less interest is invested in the process of semiosis regarding how different modes of signs are orchestrated to communicate information, which is one of the primary endeavours of social semiotics (Li and Wang, 2022 ; Wang, 2014 , 2019 ; Wang and Li, 2022 ). As such, in ethnographical studies or data analysis, language, materiality, and spatiality are usually seen as interwoven with each other, with no distinct boundaries in between; or at least, boundary-marking is not the primary concern of semiotic landscape.

In the same vein, Scollon and Scollon ( 2003 , p. 2) coin the term “geosemiotics” (or “place semiotics”) which is “the study of the social meaning of signs and discourses and of our actions in the material world”. Their research objects are signs in public places. The conceptual framework of “geosemiotics” sees language as a multimodal construct in terms of the following aspects. First, verbal language is analysed by using social semiotic approaches to visuals. Code preference (regarding which language is seen as “primary” language) shown on signs or buildings is analysed by using Kress and van Leeuwen’s ( 1996 , p. 208) conception of compositional meaning indexed by different positions in pictures. Second, language is seen as multimodal itself. Language on signs or buildings is analysed in terms of the multimodal inscription (see Scollon and Scollon, 2003 , pp. 129–142) that includes fonts, letter form, material quality, layering and state changes. Third, the emplacement (referring to meaning-making through positioning signs in different places) in geosemiotics, similar to Jaworski and Thurlow’s ( 2010 ) approach towards the semiotic landscape, is predominantly concerned with spatiality and metalinguistic or metadiscursive ideology, rather than the interaction and orchestration of different modes (language vis-à-vis non-language) in semiosis.

Similar to the concepts of semiotic landscape and place semiotics, Gu ( 2009 , 2012 ) postulates the framework of four-borne discourse and discourse geography. Based on Blommaert’s ( 2005 , p. 2) view of discourse as “language-in-action”, Gu analyses the language and activities in social actors’ trajectories of time and space in the land-borne situated discourse (LBSD): a type of discourse categorized by Gu ( 2009 ) according to different types of spatiality as carriers and places where the discourses take place. In Gu’s ( 2012 ) conceptualizations, language and discourse are metaphorically spatialized: language is seen in terms of the place where it takes place. Multimodality is evaluated based on space (Gu, 2009 ). Though it is arguable to what extent language is seen as a conflation of modes or semiotic attributes in Gu ( 2009 ), his work demarcates an ambivalent boundary between language and the “non-language”. Also, in “spatializing” language as discourse geography, it represents language and discourse as a PLACE or SPACE metaphor that is multimodal itself. In addition, it analyses the translation between different modes, for instance, the “modalization” of written language into visuals and sounds; visuals are also seen as forms of “modalized” language and vice versa. As such, Gu ( 2009 ) also represents the “spatial turn” of sociolinguistics which can be seen as the research trend that regards language as multimodal construct.

In general, the trend to spatialize language and discourse (or the “spatial turn”), with the concepts or frameworks such as semiotic landscape, place semiotics, and discourse geography, treats language as multimodal construct in the following two aspects. First, it focuses on metalinguistic or metadiscursive ideologies that are embedded in different modes of signs or symbols; also, Gu’s research metaphorically theorizes social interaction through multimodality. In other words, it posits that language itself is multimodal or modalizable in meaning-making. Written language has its multimodal dimensions such as facets of its inscription including fonts, letterform, material quality, layering and state changes (Scollon and Scollon, 2003 ). Different forms of language are multimodal in terms of spatiality: they can be naturally multimodal and aural-visual for instance in televised discourse; written language can also be “modalized” (Gu, 2009 , p. 11) into visuals (Gu, 2009 ). Overall, language is either considered as signs in the spatialized system or actions in trajectories of activities. It is an integral part of multimodal construct, where other modes (visual, gesture, action, and so on) are not peripheral or auxiliary, but frequently they also belong to linguistic resources, for instance, the visual resources in text arts.

Multimodal studies from the social interactional perspective

There are sociolinguistic approaches towards multimodality that combine social interactional sociolinguistics (Goffman, 1959 , 1963 , 1974 ), social semiotic approach towards multimodality (Kress and van Leeuwen, 1996 ), and intercultural communication (Wertsch, 1998 ). We summarize these approaches as multimodal studies from the social interactional perspective, which include mediated discourse analysis (Scollon and Scollon, 2003 ) and multimodal interaction analysis (Norris, 2004 ); the latter grew out of the former.

Multimodal studies from the social interactional perspective focus on people’s daily actions and interactions, and the environment and technologies with(in) which they take place. This trend of research sees discourse as (embedded in) social interaction and sets out to investigate social action through multimodal resources used in daily interaction, such as gestures, postures, and language (see Jones and Norris, 2005 ). In Norris’s ( 2004 ) framework for multimodal interaction analysis, units of analysis are a system of layered and hierarchical actions including the lower-level actions such as an utterance of spoken language, a gesture, or a posture, and the higher-level actions consisting of chains of higher-level actions. Norris ( 2004 ) also coins the term “modal density” to refer to the complexity of modes a social actor uses to produce higher-level actions.

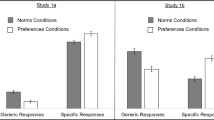

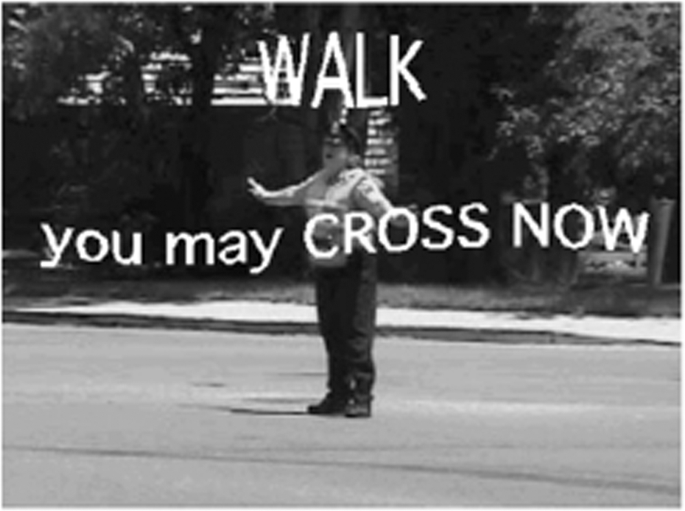

The focus on hierarchical levels of actions and the concept of “modal density” entail reflections on the question with regard to what constitute(s) mode and language. Language in multimodal interaction analysis is seen as a type of lower-level action amongst other different embodied resources that are at interactants’ disposal. These embodied resources are seen as different modes such as gesture, gaze, and proxemics. But arguably gestures and gazes in Norris ( 2004 ) are also seen as forms of language in interaction as well. Furthermore, regarding the mode of spoken language, Norris ( 2004 ) and her other works methodologically treat it as a multimodal construct where the pitches and intonation are visualized through various fonts in the wave-shaped annotation, along with the policeman’s gestures, as shown in Fig. 1 .

The policeman’s spoken language is treated as a multimodal construct where the pitches and intonation are visualized through various fonts in the wave-shaped annotation, along with his gestures.

Multimodal studies from the social interactional perspective, similar to other sociolinguistic approaches to multimodality, target the meta-modal or metadiscursive facets of ideology. This is done through a bottom-up approach, that is, examining the general social categories of such as power, dominance and ideology from people’s daily (inter)action. This trend of research focuses on basic units of actions in people’s daily interaction; the conception of mode and language is oriented toward seeing language as multimodal; the methodological treatment of languages also shows this orientation. Multimodal studies from the social interactional perspective are intended to reveal the ideology and power embedded in language as action. Overall, they perceive language as a multimodal construct in social (inter)action.

Metrolingualism, heteroglossia, polylanguaging and multimodality

In the second section of the paper, we mentioned the works on some similar notions such as metrolingualism and polylanguaging. In this section, we will review the latest application of the notion of metrolingualism in multimodal analysis and discuss why other related notions or approaches also encapsulate the conceptualization regarding language as a multimodal construct.

Metrolingualism is a concept postulated by Otsuji and Pennycook ( 2010 ) originally referring to “creative linguistic conditions across space and borders of culture, history and politics, as a way to move beyond current terms such as multilingualism and multiculturalism” (Otsuji and Pennycook, 2010 , p. 244). Their later works (Pennycook and Otsuji, 2014 , 2015a , 2015b ) develop the concept and reformulate it as a broader notion encompassing the everyday language use in the city and linguistic landscapes in urban settings.

In Pennycook and Otsuji ( 2014 , 2015b ), metrolingualism involves the practice of “metrolingual multitasking” (Pennycook and Otsuji, 2015b , p. 15), in which “linguistic resources, everyday tasks and social space are intertwined” (Pennycook and Otsuji, 2015b , p. 15). Metrolingualism thus is not only concerned with the mixed use of linguistic resources (from different languages), but it involves how language use is involved in broader multimodal practices such as (embodied) actions accompanying or included in the metrolingual process, (changing) space or places where these actions and language use take place, and the objects in the environment. Pennycook and Otsuji ( 2015b ) include an olfactory mode in their analysis of the metrolingual practices in cities. Smell is represented through linguistic or pictorial signs in the city and suburb to constitute “smellscapes” in relation to social activities, ethnicities, gender and races. Metrolingual smellscapes are represented through the conflation of written and visual signs and symbols (e.g., street signs), social activities (e.g., buying and selling, and riding a bus), objects (e.g., spices), and places or spaces (e.g., suburb markets, coffee shops, buses and trains). The conventional distinction between language and the non-language is less important, or not at issue here, as smells have to be represented through language or visuals, and more resources are conceptualized as metrolingual other than languages.

Language in Pennycook and Otsuji’s ( 2014 , 2015a , 2015b ) conception of metrolingualism, in this regard, is seen as being integrated into different types of activities and actions; it is also spatialized in the sense that metrolingual practice is seen as involving the organization of space, the relationship between “locution and location” (Pennycook and Otsuji, 2015b , p. 84), (historical) layers of cities (Pennycook and Otsuji, 2015b , p. 140). The spatialization is intrinsically multimodal, which we have discussed in earlier sections.

In relation to metrolingualism, Jaworski ( 2014 ) briefly reviews the history of arts and writing, from which he chose the art form of “text art” as his research subject. Referring to the notion of metrolingualism, he sees these art forms as “metrolingual art”, where language interacts with other modes or is seen as part of the visual mode. He suggests that it be useful to “extend the range of semiotic features amenable to metrolingual usage to include whole multimodal resources” (Jaworski, 2014 , p. 151). The multimodal representations in text art are realized by mixing, meshing and queering of the linguistic features, as well as by its relation to a “melange of styles, genres, content, and materiality” (Jaworski, 2014 , p. 151). In this regard, the multimodal affordances (Kress, 2010 ; Jewitt, 2009 ) realized by materiality (e.g., papers, cloths, walls where the language is written), media (e.g., soundtrack, video, moving images, etc.), and styles (e.g., fonts, letterform, layering like add-ons or decorations) are an integral part of the metrolingualism. Subsequently, he postulates that it would be useful to align the concept of heteroglossia with metrolingualism, so as “to extend the idea of metrolingualism beyond ‘hybrid and multilingual’ speaker practices (Otsuji and Pennycook, 2010 , p. 244) and move towards a more ‘generic’ view of metrolingualism as a form of heteroglossia” (Jaworski, 2014 , p. 152). In this way, it relates the subject position taken by the producers of the text arts to their social orientation or alignment as regards power, domination, hegemony, and ideology in a broader social realm. This is also in line with Bailey’s discussion about heterogliossia: “(a) heteroglossia can encompass socially meaningful forms in both bilingual and monolingual talk; (b) it can account for the multiple meanings and readings of forms that are possible, depending on one’s subject position, and (c) it can connect historical power hierarchies to the meanings and valences of particular forms in the here-and-now” (Bailey, 2007 , pp. 266–267; also quoted in Jaworski, 2014 , p. 153). Overall, Jaworski ( 2014 ) shows how metrolingualism and heteroglossia can be used to analyse features of language and their place in multimodal construct. He also discusses how other notions which are similar to metrolingualism may bear a relationship with multimodality in that they stress “the importance of linguistic features (rather than discrete languages) as resources for speakers to achieve their communicative aims” (Jaworski, 2014 , p. 138).

Apart from the concepts of metrolingualism and heteroglossia, Jaworski ( 2014 ) touches upon the relationship between polylanguaging and multimodality, but he does not elaborate on it. Jørgensen ( 2008 ) demonstrates how polylanguaging is concerned with the use of language features in language practice among adolescents in superdiverse societies. Some of these language features “would be difficult to categorize in any given language” (Jørgensen et al., 2011 , p. 25); that is, they do not belong to any standard language system (e.g., English, Chinese, German). In addition, emoticons are frequently used in communication via social networking software. If some of these language features do not belong to any given language, it is difficult to say whether they can be seen as languages. The attention on features of language hence blurs the boundary between language and other semiotic resources. Of course, these features can be seen as a type of linguistic (lexical, morphemic or phonemic) units which still belong to language, but they are frequently used in multimodal meaning-making. Below I use Jørgensen et al.’s ( 2011 , p. 26) example (Fig. 2 ) to illustrate this.

The “majority boy” makes use of resources from the minority’s language (the word “shark”).

Jørgensen et al.’s analysis of this example focuses on the “majority boy” using the word “shark”, which is a loan word from Arabic. As a majority member, he is using the minority’s language to which he is not entitled. Judging by the interaction, it can be seen that “both interlocutors are aware of the norm and react accordingly” (Jørgensen et al., 2011 , p. 25). As such he noted that one feature of polylanguaging is “the use of resources associated with different ‘languages’ even when the speaker knows very little of these” (Jørgensen et al., 2011 , p. 25).

What also needs attention but is not discussed by Jørgensen et al. ( 2011 ), is the interlocutors’ creative way to use these features in polylanguaging: the word “shark” is written as a prolonged “shaarkkk” in terms of its phonetic and visual effects. The creative configuration of the language feature “shark” functions to draw other interlocutors’ attention toward the polylanguaging practice. The emoticon “:D” following it is to demonstrate that the speaker knows that he is using language features by violating the “normal” rules; that is, he is using the minority language features to which he is not entitled. The repeated words “cough, cough”, followed by the emoticon “:D”, also demonstrate this.

Polylanguaging, as formulated by Jørgensen et al. ( 2011 ), deviates from the tradition of multilingualism to enumerate languages, but focuses on language features that may not belong to any given language. In this sense, the emoticons or creative configuration of words can also be seen as language features—the language features that are creatively used by a virtual community of (young) netizens in communication. These features are multimodal in the following aspects. First, they visualize the polylanguaging practice by creating new forms of words, for instance, the prolonged word “shaarkkk”. This creation itself is in fact also a process of polylanguaging, in the sense that it uses the features of common language, or language in people’s daily life (that is, non-cyber language) to create new cyber-language that is used by members of a virtual community. Second, these language features utilize the multimodal resources of embodiment in polylanguaging. For example, emoticons use different letters or punctuations (as language features from people’s daily written language) to represent different facial expressions and emotions. The repetition of the words “cough, cough”, as “a reference to a cliché way of expressing doubt or scepticism” (Jørgensen et al., 2011 , p. 27) also takes on an embodied stance. It shows that the interlocutors are aware that the majority boy is using the minority’s language to which he is not entitled. Hence, this embodied stance indexes the polylanguaging practice. To summarize what is discussed above, polylanguaging entails seeing language as a multimodal construct, as interlocutors creatively adapt language features in daily communication (face-to-face or written communication not involving the internet) or utilize embodied language features when polylanguaging in online communication.

Discussion and a critical reflection

In the sections “Language as written and spoken signs and symbols” and “Language in vis-à-vis as multimodal construct” above, we delineated the ontological perceptions of language in sociolinguistics, including language as spoken and written signs and symbols, language in vis-à-vis as a multimodal construct. In teasing out various trends of approaches, language in sociolinguistics is found to have undergone several stages of development. Language as spoken and written signs and symbols have been pursued in variational sociolinguistics, bi- and multilingualism, and the latest theoretical and conceptual trends of research that do not see language as separate and separable systems or codes. Language in sociolinguistics, however, has been predominantly placed in nuanced and complicated relationships with other semiotic resources. Research regarding language in multimodal constructs sees language and non-language resources as different modes, or types of resources. These different modes have boundaries, and efforts are made to see how each mode combines with each other in meaning-making; language itself is a distinctive type of mode, interdependent with but different from other modes. Research regarding language as a multimodal construct sees language itself as multimodal, language is spatialized (that is, probed in relation to various spatiality and materiality where they appear); in the social interactional approach to multimodality, it is embodied and seen as embedded in a layered and hierarchical system of modes (including gesture, posture, and intonation) in social interaction; in the latest concepts built on languaging, language is regarded as “inventions” (Makoni and Pennycook, 2005 ), as cross- and trans-cultural practice, instead of separable and enumerable codes, or system. Language is entangled and integrated with objects (for instance, signage, and the materiality where it appears) and multitasking with embodied resources (gestures, talking, and simultaneously doing other things).

Expanding the ontology of language from verbal resources toward various multimodal constructs has enabled sociolinguists to pursue meaning-making, indexicalities and social variations in its most authentic state. Language itself is multimodal, though it cannot be denied that language and other modes do have boundaries and distinctions (yet not always being so). Whenever a language is spoken, the stresses, intonations, and paralinguistic resources are all integrated into it. Focusing on language per se has generated fruitful outcomes in sociolinguistic studies, but placing language in the multi-semiotic resources has innovated the field and it has become the dominant trend in contemporary sociolinguistics. Both languages in or as multimodal constructs have captured the complex ways in which language interacts with multi-subjects, materiality, objects and spatiality. But it may be found that the latest research in sociolinguistics comes to increasingly see language itself as an intricate multimodal construct, as encapsulated by various new concepts and theories including translanguaging, metrolingualism, and polylanguaing, in the contexts of globalization, migration, multi-ethnicity, and new communication technologies. Language is not only seen as separable codes and systems spoken or written by a different group of people, but it entails a wider range of communicative repertoires including embodied meaning-making, objects and the environment where the written or spoken signs are placed. It hence may be speculated that sociolinguistics will be increasingly less concerned with the boundaries of language and non-language resources, but will focus more on the social constructs, social meaning, and language as a force in social change. The enumerating and separating way of studying language and multimodality—that is, delineating inter-semiotic boundaries and focusing on how modes of communication are combined in meaning-making—has generated various outcomes, especially in the field of grammar-oriented social semiotic research and MCDA. However, contemporary sociolinguistic studies have immensely expanded their scope toward a wider range of areas other than discursive, grammatical, and communicative. The three research paradigms regarding language as a multimodal construct reviewed in “Language as multimodal construct” have proved themselves as a feasible approach toward language in social interaction, geo-semiotics, and language use in ethnographical and multi-ethnic settings. The ontology of language in sociolinguistics, in this regard, may be perceived in terms of the sociology and societal facets of multimodal construct, rather than language placed in a multitude of semiotic types or the verbal resources per se. A critical reflection on the ontology of language is one of the prerequisites of innovations in contemporary linguistics, which is also the objective of this comprehensive review.

As can be seen through the above discussion, there are several versions of the perception of language in sociolinguistics. First, perceptions of language as a written or verbal system are moving from, or have moved from, the enumerating traditions bi- or multi-lingualism towards seeing language as an inseparable entity with fixity and fluidity. In other words, new approaches in sociolinguistics come to see languages as comprising different features, repertories, or resources, rather than different or discrete standard languages such as English, French, German and so on. The negotiation, construction, or attribution of ethnicity, identity, power and ideologies through language also has taken on a more dynamic and diverse look. Second, there is sociolinguistic research that places language with in the multimodal construct. Language is seen as being contextualized by other multimodal semiotics that is seen as “non-language”. However, more research comes to see language as multimodal construct; that is, language, be it written or spoken, is multimodal in itself as it comprises multimodal elements such as type, font, materiality, intonation, embodied representations and so on. It is also activated (seen as actions or activities) or spatialized in different approaches such as mediated discourse analysis, multimodal interaction analysis, geosemiotics, semiotic landscape, and metrolingualism discussed earlier. Third, these changing perceptions of languages in sociolinguistics result from researchers’ innovative efforts to view language from different perspectives. More importantly, they arise from the fact that language itself is also changing as society changes. As mentioned in the beginning, the world has been increasingly globalized and communications technologies have fundamentally changed the ways people interact with each other. Linguistic practices are complicated by the super-diversity of ethnic fluidity (e.g., the diversity of ethnic groups and the ever-present changes in ethnic structure), communications technologies, and globalized cross-cultural art.

In sum, it can be argued that contemporary sociolinguistics has become increasingly concerned with languaging (trans-, poly-, metro-, and pluri- and so on), rather than languages as a type of (static and fixed) verbal resource with demarcated boundaries separating them from other multimodal resources. Language is multimodal; it is embedded in or represents social activities, places or spaces, objects, and smells. Language in society belongs to and constitutes the “semiotic assemblage” (Pennycook, 2017 ) that can be better analysed holistically so as to reach an understanding of “how different trajectories of people, semiotic resources and objects meet at particular moments and places” (Pennycook, 2017 , p. 269). At a fundamental level of sociolinguistic ontology, this trend of research reflects the changing ways in which sociolinguists come to understand what language is and how it should be understood as part of a more general range of semiotic practices.

Agha A (2003) The social life of cultural value. Language Commun 23(3–4):231–273

Article Google Scholar

Berger P, Luckmann T (1966) The social construction of reality: a treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Doubleday, New York

Google Scholar

Blackledge A, Creese A (2010) Multilingualism: a critical perspective. Continuum, London

Blommaert J (Ed.) (1999) Language ideological debates, vol. 2. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin

Blommaert J (2005) Discourse: a critical introduction. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Book Google Scholar

Bourdieu P (1991) Language and symbolic power [Thompson JB (ed and introd)] (trans: Raymond G, Adamson M). Polity Press/Blackwell, Cambridge

Bailey B (2007) Heteroglossia and boundaries. In: Heller M (Ed.) Bilingualism: a social approach. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, pp. 257–274

Chapter Google Scholar

Cameron D (1990) Demythologizing sociolinguistics: why language does not reflect society. In: Joseph J, Taylor T (eds) Ideologies of language. Routledge, London, pp. 79–93

Chomsky N (1965) Aspects of the theory of syntax. MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Coupland N (2003) Sociolinguistic authenticities. J Sociolinguist 7(3):417–431

Coupland N (2007) Style: language variation and identity. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Creese A, Blackledge A (2010) Translanguaging in the bilingual classroom: a pedagogy for learning and teaching? Mod Language J 94:103–115

Eckert P, Rickford JR (Eds.) (2001) Style and sociolinguistic variation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Eckert P (2008) Variation and the indexical field. J Sociolinguist 12(4):453–476

Eckert P (2012) Three waves of variation study: the emergence of meaning in the study of sociolinguistic variation. Annu Rev Anthropol 41(1):87–100

García O, Li W (2014) Translanguaing: language, bilingualism and education. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Goffman E (1959) The presentation of self in everyday life. Doubleday, New York, NY

Goffman E (1963) Behavior in public places. Free Press, New York, NY

Goffman E (1974) Frame analysis. Harper & Row, New York, NY

Goodwin C (2007) Participation, stance, and affect in the organization of activities. Discourse Soc 18(1):53–73

Gu Y (2009) Four-borne discourses: towards language as a multi-dimensional city of history. In: Li W, Cook V (eds.) Linguistics in the real world. Continuum, London, pp. 98–121

Gu Y (2012) Discourse geography. In: Gee JP, Hanford M (eds.) The Routledge handbook of discourse analysis. Routledge, London, pp. 541–557

Hebdige D (1984) Framing the youth ‘problem’: the construction of troublesome adolescence. In: Garms-Homolová V, Hoerning EM, Schaeffer D (eds.) Intergenerational Relationships. Lewiston, NY: C. J. Hogrefe, pp.184–195

Holliday N (2021) Prosody and sociolinguistic variation in American Englishes. Annu Rev Linguist 7:55–68

Irvine JT, Gal S (2000) Language ideology and linguistic differentiation. In: Kroskrity PV (ed.) Regimes of language: ideologies, polities, and identities. School of American Research Press, Santa Fe, pp. 35–84

Jaworski A (2014) Metrolingual art: multilingualism and heteroglossia. Int J Biling 18(2):134–158

Jaworski A, Thurlow C (eds.) (2010) Semiotic landscapes: language, image, space. Continuum, New York

Jewitt C (2009) Different approaches to multimodality. In: Jewitt C (ed) The Routledge handbook of multimodal analysis. Routledge, Abingdon, pp. 28–39

Jewitt C (2013) Multimodality and digital technologies in the classroom. In: de Saint-Georges I, Weber J (eds) Mulitlingualism and multimodality: current challenges for educational studies. Sense Publishing, Boston, pp. 141–152

Jørgensen JN (2008) Poly-lingual languaging around and among children and adolescents. Int J Multiling 5(3):161–176

Jørgensen JN, Karrebæk MS, Madsen LM, Møller JS (2011) Polylanguaging in superdiversity. Diversities 13(2):23–37

Jacquemet M (2005) Transidiomaticpractices: language and power in the age of globalization. Language Commun 25:257–277

Jones R, Norris S (2005) Discourse as action/discourse in action. In: Norris S, Jones R (eds) Discourse in action: introducing mediated discourse analysis. Routledge, London, pp. 1–3

Kallen J (2010) Changing landscapes: language, space and policy in the Dublin linguistic landscape. In: Jaworski A, Thurlow C (eds) Semiotic landscapes: language, image, space. New York: Continuum, pp. 41–58

Kress GR (2010) Multimodality: a social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. Routledge, London

Kress GR, van Leeuwen T (1996) Reading Images: the grammar of graphic design. Routledge, London

Kroskrity PV (1998) Arizona Tewa Kiva speech as a manifestation of linguistic ideology. In: Schieffelin BB, Woolard KA, Kroskrity P (eds) Language ideologies: practice and theory. Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 103–122

Labov W (1963) The social motivation of a sound change. Word 19(3):273–309

Labov W (1966) Hypercorrection by the lower middle class as a factor in linguistic change. Sociolinguistics 1966:84–113

Lawson R (2020) Language and masculinities: history, development, and future. Annu Rev Linguist 6(1):409–434

Lewis WG, Jones B, Baker C (2012) Translanguaging: origins and development from school to street and beyond. Educ Res Eval 18(7):641–654

Li W, Wang J (2022) Chronotopic identities in contemporary Chinese poetry calligraphy. Poznan Stud Contemp Linguist 58(4):861–884

Machin D (2016) The need for a social and affordance-driven multimodal critical discourse studies. Discourse Soc 27(3):322–334

Machin D, Mayr A (2012) How to do critical discourse analysis: a multimodal introduction. Sage, London

Maher J (2005) Metroethnicity, language, and the principle of Cool. Int J Sociol Language 11:83–102

Makoni S, Pennycook A (2005) Disinventing and (re)constituting languages. Crit Inq Language Stud 2(3):137–156

Martin-Jones M, Blackledge A, Creese A (eds) (2012) The Routledge handbook of multilingualism. Routledge, London

Norris S (2004) Analyzing multimodal interaction: a methodological framework. Routledge, London

Otsuji E, Pennycook A (2010) Metrolingualism: fixity, fluidity and language in flux. Int J Multiling 7:240–254

Pennycook A (2017) Translanguaging and semiotic assemblages. Int J Multiling 14(3):1–14

Pennycook A, Otsuji E (2014) Metrolingual multitasking and spatial repertoires: ‘Pizza mo two minutes coming’. J Socioling 18(2):161–184

Pennycook A, Otsuji E (2015a) Making scents of the landscape. Linguist Landsc 1(3):191–212

Pennycook A, Otsuji E (2015b) Metrolingualism. Language in the city. Routledge, New York

Sankoff G (2018) Language change across the lifespan. Annu Rev Linguist 4:297–316

Schegloff EA (1992) In another context. In: Duranti A, Goodwin C (eds) Rethinking context: language as an interactive phenomenon. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 191–227

Schegloff EA (1998a) Positioning and interpretative repertoires: conversation analysis and poststructuralism in dialogue: reply to Wetherell. Discourse Soc 9(3):413–416

Schegloff EA (1998b) Reply to Wetherell. Discourse Soc 9(3):457–60

Schegloff EA (1999) ‘Schegloff’s texts’ as ‘Billig’s data’: a critical reply. Discourse Soc 10(4):558–572

Scollon R, Scollon S (2003) Discourses in place: language in the material world. Routledge, New York

Saussure F (1916) Course in general linguistics. Duckworth, London

Wang J (2014) Criticising images: critical discourse analysis of visual semiosis in picture news. Crit Arts 28(2):264–286

Wang J (2016a) Multimodal narratives in SIA’s “Singapore Girl” TV advertisements—from branding with femininity to branding with provenance and authenticity? Soc Semiot 26(2):208–225

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Wang J (2016b) A new political and communication agenda for political discourse analysis: critical reflections on critical discourse analysis and political discourse analysis. Int J Commun 10:19

ADS Google Scholar

Wang J (2019) Stereotyping in representing the “Chinese Dream” in news reports by CNN and BBC. Semiotica 2019(226):29–48

Wang J, Jin G (2022) Critical discourse analysis in China: history and new developments. In: Aronoff M, Chen Y, Cutler C (eds) Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.013.909

Wang J, Li W (2022) Situating affect in Chinese mediated soundscapes of suona. Soc Semiot. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2022.2139171

Wang J, Yang M (2022) Interpersonal-function topoi in Chinese central government’s work report (2020) as epidemic (counter-) crisis discourse. J Language Politics. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.22022.wan

Wertsch JV (1998) Voices of the mind: a sociocultural approach to mediated action. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Woolard K (1999) Simultaneity and bivalency as strategies in bilingualism. J Linguist Anthropol 8(1):3–29

Download references

Acknowledgements

Our thanks are extended to Dr. William Dezheng Feng for his constructive advice on the earlier drafts of the paper. This work is supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (Project No. 18CYY050); the Foreign Language Education Foundation of China (Project No. ZGWYJYJJ11A030); and the Self-Determined Research Funds of CCNU from MOE for basic research and operation (Project No. CCNU20TD008).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Central China Normal University, Wuhan, China

Jiayu Wang, Guangyu Jin & Wenhua Li

Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Hohhot, China

Guangyu Jin

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All three authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. JW mainly participated in drafting the work. GJ revised it critically for important intellectual content. WL participated in major intellectual contributions to the Chinese versions of the paper (unpublished); her ideas and points are integrated into the final version of this paper. All three authors are corresponding authors responsible for the final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Jiayu Wang , Guangyu Jin or Wenhua Li .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Additional information.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Wang, J., Jin, G. & Li, W. Changing perceptions of language in sociolinguistics. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10 , 91 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01574-5

Download citation

Received : 12 September 2022

Accepted : 20 February 2023

Published : 08 March 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01574-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

The Hidden Bias of Science’s Universal Language

The vast majority of scientific papers today are published in English. What gets lost when other languages get left out?

Newton’s Principia Mathematica was written in Latin; Einstein’s first influential papers were written in German; Marie Curie’s work was published in French. Yet today, most scientific research around the world is published in a single language, English.

Since the middle of the last century, things have shifted in the global scientific community. English is now so prevalent that in some non-English speaking countries, like Germany, France, and Spain, English-language academic papers outnumber publications in the country’s own language several times over. In the Netherlands, one of the more extreme examples, this ratio is an astonishing 40 to 1.

A 2012 study from the scientific-research publication Research Trends examined articles collected by SCOPUS, the world’s largest database for peer-reviewed journals. To qualify for inclusion in SCOPUS, a journal published in a language other than English must at the very least include English abstracts; of the more than 21,000 articles from 239 countries currently in the database, the study found that 80 percent were written entirely in English. Zeroing in on eight countries that produce a high number of scientific journals, the study also found that the ratio of English to non-English articles in the past few years had increased or remained stable in all but one.

This gulf between English and the other languages means that non-English articles, when they get written at all, may reach a more limited audience. On SCImago Journal Rank —a system that ranks scientific journals by prestige, based on the citations their articles receive elsewhere—all of the top 50 journals are published in English and originate from either the U.S. or the U.K.

In short, scientists who want to produce influential, globally recognized work most likely need to publish in English—which means they’ll also likely have to attend English-language conferences, read English-language papers, and have English-language discussions. In a 2005 case study of Korean scientists living in the U.K., the researcher Kumju Hwang, then at the University of Leeds, wrote: “The reason that [non-native English-speaking scientists] have to use English, at a cost of extra time and effort, is closely related to their continued efforts to be recognized as having internationally compatible quality and to gain the highest possible reputation.”

It wasn’t always this way. As the science historian Michael Gorin explained in Aeon earlier this year, from the 15th through the 17th century, scientists typically conducted their work in two languages: their native tongue when discussing their work in conversation, and Latin in their written work or when corresponding with scientists outside their home country.

“Since Latin was no specific nation’s native tongue, and scholars all across European and Arabic societies could make equal use of it, no one ‘owned’ the language. For these reasons, Latin became a fitting vehicle for claims about universal nature,” Gordin wrote. “But everyone in this conversation was polyglot, choosing the language to suit the audience. When writing to international chemists, Swedes used Latin; when conversing with mining engineers, they opted for Swedish.”

As the scientific revolution progressed through 17th and 18th centuries, Gordin continued, Latin began to fall out of favor as the scientific language of choice:

Galileo Galilei published his discovery of the moons of Jupiter in the Latin Sidereus Nuncius of 1610, but his later major works were in Italian. As he aimed for a more local audience for patronage and support, he switched languages. Newton’s Principia (1687) appeared in Latin, but his Opticks of 1704 was English (Latin translation 1706).

But as this shift made it more difficult for scientists to understand work done outside of their home countries, the scientific community began to slowly consolidate its languages again. By the early 19th century, just three—French, English, and German—accounted for the bulk of scientists’ communication and published research; by the second half of the 20th century, only English remained dominant as the U.S. strengthened its place in the world, and its influence in the global scientific community has continued to increase ever since.

As a consequence, the scientific vocabularies of many languages have failed to keep pace with new developments and discoveries. In many languages, the words “quark” and “chromosome,” for example, are simply transliterated from English. In a 2007 paper, the University of Melbourne linguist Joe Lo Bianco described the phenomenon of “domain collapse,” or “the progressive deterioration of competence in [a language] in high-level discourses.” In other words, as a language stops adapting to changes in a given field, it can eventually cease to be an effective means of communication in certain contexts altogether.

In many countries, college-level science education is now conducted in English—partially because studying science in English is good preparation for a future scientific career, and partially because the necessary words often don’t exist in any other language. A 2014 report from the University of Oxford found that the use of English as the primary language of education in non-English speaking countries is on the rise, a phenomenon more prevalent in higher education but also increasingly present in primary and secondary schools.

But even with English-language science education around the world, non-native speakers are still often at a disadvantage.

“Processing the content of the lectures in a different language required a big energetic investment, and a whole lot more concentration than I am used to in my own language,” said Monseratt Lopez, a McGill University biophysicist originally from Mexico.

“I was also shy to communicate with researchers, from fear of not understanding quite well what they were saying,” she added. “Reading a research paper would take me a whole day or two as opposed to a couple of hours.”

Sean Perera, a researcher in science communication from the Australian National University, described the current situation this way: “The English language plays a dominant role, one could even call it a hegemony … As a consequence, minimal room or no room at all is allowed to communicators of other languages to participate in science in their own voice—they are compelled to translate their ideas into English.”

In practice, this attitude selects for only a very specific way of looking at the world, one that can make it easy to discount other types of information as nothing more than folklore. But knowledge that isn’t produced via traditional academic research methods can still have scientific value—indigenous tribes in Indonesia , for example, knew from their oral histories how to recognize the signs of an impeding earthquake, enabling them to flee to higher ground before the 2004 tsunami hit. Similarly, the Luritja people of central Australia have passed down an ancient legend of a deadly “fire devil” crashing from the sun to the Earth—which, geologists now believe, describes a meteorite that landed around 4,700 years ago.

“It is all part of a growing recognition that Indigenous knowledge has a lot to offer the scientific community,” the BBC wrote in an article describing the Luritja story. “But there is a problem—indigenous languages are dying off at an alarming rate, making it increasingly difficult for scientists and other experts to benefit from such knowledge.”

Science’s language bias, in other words, extends beyond what’s printed on the page of a research paper. As Perera explained it, so long as English remains the gatekeeper to scientific discourse, shoehorning scientists of other cultural backgrounds into a single language comes with “the great cost of losing their unique ways of communicating ideas.”

“They gradually lose their own voice,” he said—and over time, other ways of understanding the world can simply fade away.

Graduate College

Science of language.

Ashby Martin, a third-year doctoral student in the neuroscience program, didn’t always want to study the brain. Initially, he wanted to be a librarian. At a young age, he memorized his library card number and looked up to the librarians. “My favorite place to go was the library,” he said. “Librarians get to give people knowledge and resources all for free. They give everyone the same access.”

Buried in books, Martin found himself wanting to investigate things that were unknown; things that hadn’t been written down yet or even discovered, especially about the brain.

This inclination led Martin to pursue neuroscience. Martin received his bachelor’s in neuroscience and behavior at the University of Notre Dame before joining Iowa’s doctoral program. The faculty, the connection to the hospital, and the foundational research that originated on campus were driving factors in his decision to come here. Martin specifically recalled Iowa’s psychological studies on patient S.M. (“The Woman with No Fear”) and meeting program director Dr. Dan Tranel.

“That’s the past. [Tranel] is part of the present, and I could be part of the future. My research could be part of that future,” he says.

Third-year doctoral student Ashby Martin. Photo provided by Ashby Martin.

Connecting through language

At Iowa, Martin studies developmental neurolinguistics, particularly in young children who are bilingual in Spanish and English. His focus is on “numbers as language”, and he examines the neurological impact and visual representation of shifting between the individual’s multiple linguistic repertories through neurological imaging.

One in three children under the age of eight speaks two languages. In Iowa, there are robust multilingual communities including West Liberty, Columbus Junction, and Amish populations who speak Pennsylvanian Dutch. As part of his studies, Martin has been able to connect with some of these multilingual communities in addition to participants in the Iowa City area.

“Visually you can see the learning happening,” he says. “You can connect with people and share something local Iowans actually have . You can share effects that you see in their brains.”