Water’s Edge

The story of bill may, the greatest male synchronized swimmer who ever lived, and his improbable quest for olympic gold., july 25, 2015 kazan, russia.

he Russian, pale and sour, ballet-walks heel-toe, heel-toe onto the pool deck in his bathing suit, which is designed to look like a communist-era military uniform. It consists of shorts, a real fold-down collar, actual epaulets and a black cross-body strap for ammunition. A woman, the Russian's partner, all nose and eyebrows in a lavender bathing suit decorated with appliqué flowers, prances out behind him tragically, and they embrace in this brightly lit arena in Kazan, at the first synchronized swimming world championship to include men. There is a TV camera here, and it projects the swimmers onto large screens for those in the cheap seats, and it immediately zooms in on the hammer and sickle insignia on the Russian's belt so that it seems to fill the arena. This elicits an eardrum-melting roar from the crowd, where a woman in the stands puts her hand to her face. A man nods heavily with memory. Did that judge just wipe away a tear? These are only the prelims in the mixed-gender technical duet event, but one day later during the finals, the audience, many of whom are here now, will react exactly the same way, as if their hearts are being broken anew for their tragic communist pasts.

Bill May, the United States' lone male synchronized swimmer, stands in the wings of the arena, a smile of teeth, teeth, teeth spread across his face. Bill May's smile is a wonder. When he leaves a room, its silhouette remains, like when you close your eyes after a camera flashes and all you can see is the bulb's yellow outline. He is still damp from his own routine, a red, white and blue warm-up suit covering his coral Speedo. If you didn't know Bill, you'd think this big smile, the one he wears as he watches his greatest competitors slow-motion-kill the home-team crowd dead, is his real smile.

More ESPN Mag

Strauss: How Nike lost Steph Curry

Subscribe to The Mag

But if you did know Bill, you'd know it isn't his real smile. How could it be? He is so close to losing the gold medal he was told he could never compete for, the medal he unretired for after a decade away from the sport. He dropped his whole life for seven months to train and travel to Russia and to stand atop the podium for what could be one final time, smiling his real smile, the one that spreads past the borders of his face so that it becomes the biggest thing about him. And here he is, different smile covering a lack of certainty he didn't acknowledge until maybe just now.

You could argue that Bill shouldn't be this nervous. Mixed-gender duets didn't officially exist even a year ago, so very few countries had a man ready to swim when synchro's governing body, Fédération Internationale de Natation (FINA), decided to allow male competitors at worlds. There are only six teams listed for the tech duet -- and the other five don't have Bill May . Everyone wants to win, yes, but this entire event is an audition of sorts too, and Bill knows that the fate of male synchronized swimming rests largely on his double-jointed shoulders. FINA brass are watching to see whether mixed-gender duets are compelling, whether people show up, whether they're not as much of a joke as everyone had assumed they'd be all these years. If FINA deems them Olympics-worthy, it will recommend that the International Olympic Committee consider including mixed-gender as an event. Which means the winners could be headed to Rio this summer, or more likely Tokyo in 2020. Which means Kazan could be Bill's big break -- Bill, a male synchronized swimmer, the male synchronized swimmer, could finally be in the Olympics. So what that it comes a full 10 years after he retired?

In his admirable and lonely career, Bill had won just about any competition that would have him. He stood damp and shiny on the podiums of the French Open, the Swiss Open, the Rome Open, the German Open, the U.S. nationals, gold medals gleaming from his chest, his smile (teeth, teeth, teeth) transmitting victory and stick-to-itiveness to all who watched. But Bill was always stopped short of the Olympic qualifiers, even as his female partners and the teams he trained with had medals placed around their necks. Synchro is a women's sport, but Bill was allowed to compete at many events because of the hassle it would have been to turn him away, because men can claim discrimination too, believe it or not. Yet despite that, he couldn't get into the qualifying events for the Olympics because he couldn't get into the Olympics because, well, synchro is a women's sport.

Bill remained poised and persuasive. He performed and charmed, and it almost worked. Everyone liked him. Even his detractors, even the people who excluded him or didn't speak up after they had promised to, even they tsk-tsked about what a shame it was when he retired in 2004 without a shot at worlds or the Olympics. But they are also quick to say, when the matter of discrimination comes up, that it wasn't that they were discriminating against men. Bill didn't represent throngs of boys fighting for equality; it was just him. You can't change an entire sport just for Bill, right?

“Bill knows that the fate of male synchronized swimming rests largely on his double-jointed shoulders.”

After 10 years away from synchro, Bill was doing fine. He had a speed-swimming team he trained with in Las Vegas, where he lived. He had two Weimaraners. He had people he loved in the Cirque du Soleil show he swam in two times each night. He had family. He was fine . He had learned to look at all he did as an accomplishment rather than a failure. He had learned to be proud to be a footnote to the sport, which is its own accomplishment, right? He was fine.

Then came Nov. 29, 2014, and Bill got word that FINA had voted to include two mixed-gender synchronized swimming events in the world championship. But word was that FINA had also started to worry about synchronized swimming losing traction at the Olympics. FINA figured some news, a rush of attention, might take synchro off the endangered list. Not to mention that the IOC president had recently called for the inclusion of more mixed-gender events.

Anyone else might have been bitter, being used and traded in FINA's attempt to save synchro after all these years of ignoring him. But Bill's answer? Who cares! He convinced and co-opted his former coach; recruited his (retired) former duet partner, an Olympian, for the free routine; and recruited a more recent (but still retired) Olympian for the technical. They set up schedules and pooled expenses and talked to their bosses about flexibility and their families about understanding. Then there they were, practicing for an event people never thought they'd live to see, doing it all because, what if it worked? They were adults with jobs and commitments. Yet each of them wondered: What if I could be a part of history? What if I could be the reason something changed?

Here in Kazan, the Russian cartwheels into the pool and his date flips in after him. The Russian is ostensibly going off to war, and his lady is desperately sad about it. But the storyline is hard to discern once they're in the pool because the technical duet (unlike the free duet to follow) is a set of predetermined elements in a predetermined order that every other team performs the exact same way, so there is little interplay between any two swimmers. Their music, a joyless Mikael Tariverdiev number misnamed "17 Moments of Spring," was edited so that it is randomly punctuated by the sounds of bombs falling and exploding -- not a great sound in an arena at an international sporting event, but by the second minute, you quit ducking for cover. At the end of the two minutes, they are both in a dead man's back float, and the crowd goes wild all over again, and Bill May's smile, which remember is not a real Bill May smile, becomes even less of a Bill May smile. This wasn't the plan. The plan was that Bill would do what he does, which is dazzle and win and beat the Russians. But this routine was so good (and in the Russians' home pool, no less) that it was hard to imagine even Bill topping it.

The music stops. The crowd stands. 2015 marks the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II, and the Russians are sentimental about their communist past, no matter the sport.

It is common knowledge that judges score more strictly at the start of an event (and the Americans went second, the Russians last). It is common knowledge that there is a real home-court advantage to synchro (and we are in Kazan). It is common knowledge that Russians have been crushing Americans in synchro since the U.S. released its grip on the gold in 2000 (and remains baffled as to how to get the gold back). And it is common knowledge that once the Russians dominate a sport, they are unwilling to let go.

The Russians take it: 88.8539, a full 2.1431 points higher than the score of Bill and his partner, Christina Jones. Bill smiles as he leaves the arena, and he smiles on the shuttle back to the athletes village. Yes, it was only the prelims, but that Russian routine, hoo boy. Only once he is behind that closed door does Bill May, the great wet hope of synchronized swimming, let himself consider the possibility of his storybook career ending with a loss.

As a teenager, Bill May moved across the country to become the first male member of the Santa Clara Aquamaids. Courtesy Bill May

Spring 1994 Tonawanda, New York

It seemed like a trick. It was as if a video had been paused and the image in front of you was frozen. But, no, this was live. Bill was 15 years old, at the qualifying meet for the national age-group championship, when he dove into the water for his solo routine and stopped in an upside-down vertical position without his lower body being fully immersed in the water. That's right, take a moment, picture it: He dived into the water, and once partially under, once he was in up to the waist, Bill stopped his lower body from entering the pool -- he froze, he halted acceleration, he defied inertia. The audience also froze, in surprise and awe, because how do you do that? How do you dive in and just stop without your entire body getting wet? How was it possible to see Bill May, the top of his shiny metallic suit still poking out of the water, in suspended animation?

The routine went on, a music medley that included the themes from Exodus and Dances With Wolves , and Bill did a spin rotation, dropping his leg into a side crane. But at that point, who cared about the rest of the routine? Whose brain was not still processing the feat? The only person who had ever done it before was another swimmer, Patti Rischard, a native of Tonawanda, many years before. Bill had done it as a sort of tribute, he says now. But maybe he also did it to see whether he could. Maybe he also did it to prove that he could.

The meet ended, and the winners were called to the podium. Bronze mounted and got her medal. Applause. Silver, who had been gold the year before, mounted. Applause. Bill got up there -- strong and tall and disconcertingly male and beaming his Bill May smile -- and just as the top medal was being placed over his head, he and everyone else heard booing from the audience. It was Silver's father, furious with the righteous anger of a man whose daughter had been edged out by a boy in an all-female sport.

No one was quite like Bill May. His likability began in the water. He knew how to hold a crowd, which is something a synchronized swimmer must do out of necessity, since no matter who you are, you are small in a pool, and you are always partially submerged, and so you have to find ways to be big. Bill could flick his pointed foot for comical effect or roll his wrist for a dramatic one. He knew how to move his head to demonstrate longing or excitement. Gender aside (or maybe gender to the point), no one had the same strength and swiftness to battle the water without being overtaken by it, to propel himself out of the pool with force despite not being allowed to touch the bottom. Nobody just plain didn't tire out the way Bill just plain didn't tire out.

“Bill didn't represent throngs of boys fighting for equality; it was just him.”

Still, no matter how much the world of synchro liked him personally, and no matter how much his female competitors admired his love of their sport, Bill was barely tolerated. Someone -- he doesn't know who -- called Bill's house and told his mother he was a sicko and a pervert for insisting on spending all day with girls in their bathing suits. Bill and his coach, Chris Carver, considered litigation after some competitions wouldn't allow him in, but they didn't have the money. Bill's camp had been optimistic, but the others' optimism waned while Bill's still glowed with the painfully American idea that life could be fair, that you could work hard and want something and that just the working and the wanting could win over hearts, knock down barriers and cause change in even the most ossified institutions.

The people who cared most about Bill worried. Dee O'Hara, Bill's first synchro coach, feared that he had no future. "Just do swimming," she pleaded. Speed-swimming. Or diving. Or gymnastics. She'd never seen such a gifted athlete. She didn't understand why he'd waste this kind of talent on a sport that, yes, she loved, but that was never going to welcome him as anything but an oddity and a hassle.

To Bill, though, none of those other sports was synchro. None of them was an opportunity to show how athletic you could be in the water and perform something that could elicit emotion from an audience. None of it was the costumes and the makeup and the music. Bill May lived for the costumes and the makeup and the music. He lived for the water. He was a performer, and an athlete, and both of those aspects of himself were too big to ignore. What better sport to showcase them in the water than synchronized swimming?

He should have felt discouraged, maybe even wanted to call it quits. But back when he was a young trainee, his coaches would goad him to excel by chiding him, telling him he wasn't a world champion yet, and that spurred him on, the idea that other people thought he could be a world champion, that even though he wasn't allowed into the world championship, here were people who knew what they were talking about using his name in the same sentence with "world championship." Here were people who believed that the time would come and they would all see Bill compete.

So he knows how well-regarded he was and still is as a swimmer. He still has all those medals. But as time went on, this was the thought that kept him hungry and began to eat at him: If you believed you belonged on a sport's biggest stage but were banned from that stage, wouldn't you always ask: Did I really belong?

Those who witnessed Bill May at his peak can say that he was the best, that he would have blown everyone out of the deep and gelatin-spattered water, but he'll never really know (and we'll never really know) unless he is allowed to compete in the Olympics, or even just the world championship. Which is to say that as Bill began to train for worlds, he didn't quite know either.

Bill May was told he would never have a future in synchronized swimming. But his love and passion for the sport fueled his desire to become one of the best synchronized swimmers in the world - and make history in the process. John Huet

May 2015 Santa Clara, California

The first thing Bill May will ask you when he meets you is: Where are you from and what is your favorite place to eat there? He will ask what your favorite ice cream flavor is and where you were when you first had it. We made a lot of Rocky IV jokes about the training and about Kazan -- the Cold War might be over, but in sports arenas everywhere, whenever it is the Russians vs. the Americans, that movie plays out again and again -- and my favorite joke is this: that the Russian male synchro contender will stomp over to Bill during the meet and say, "I will break you," and Bill will respond, "What's your favorite ice cream flavor?"

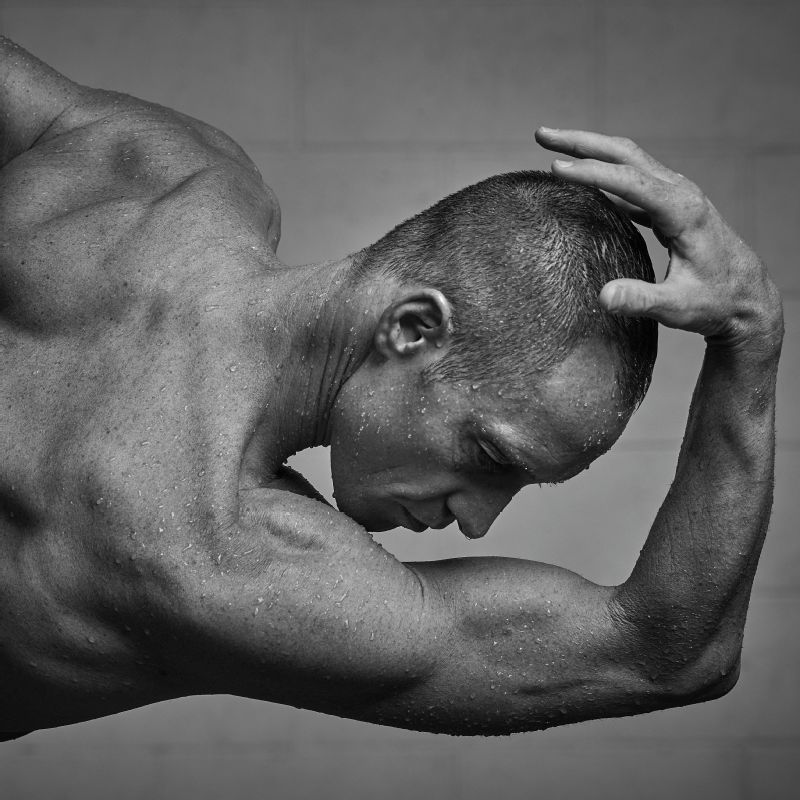

Bill May is 5-foot-9 and 155 pounds and carved like a statue. He won't eat mayonnaise or creamy dressings, but that's about all he won't eat. Between practices I watched him consume perhaps nearly every food that didn't contain mayonnaise or a creamy dressing. I've seen him devour a full order of pancakes as a side dish. I've seen him drink multilayered lemonade that looked like a watermelon -- and it wasn't delicious at all, I can promise you that. I've seen him order a refill of it anyway. I've seen him eat a doughnut the size of a newborn while in the pool. I've seen him, post-swim, eat a corned beef sandwich, a sandwich his large, smiley mouth wasn't technically large enough to accommodate. He made it work.

He has a mostly shaved head, with a very short mohawk that brings to mind a rooster, a little banana of hair that looks as if it's been dyed but he swears he never touches it, it's just that he's in the pool so much that it's permanently bleached from the sun and oxidized from the chlorine. When he laughs, he leans his head all the way back and opens up his giant jaw, and his laugh -- heh, heh, heh -- comes from deep within his solar plexus. His body is mostly hairless, his natural fur burned off by the chlorine after hours and hours in the pool, the hair under his arms lasered and smooth. One part of his Cirque du Soleil act involves walking around with his arm extended around the back of his neck, thanks to those double-jointed shoulders. When he first joined, one of the acrobats at Cirque told him, "People are looking at your armpits for two hours a night. You should get rid of the hair."

When Bill was 10, he started training with his local club, the Syracuse Synchro Cats, but they disbanded when their coach moved away. He and the other Synchro Cats set up elaborate car pools to be Oswego Lakettes, an hour each way, eating their dinner and doing their homework in the car. Still, that amounted to maybe four and a half hours in the pool per week, not enough to make a dent -- not enough to make a champion.

And so, when Bill was 16, he hid under the covers in his bedroom in Syracuse, New York, vibrating like a Chihuahua from nerves, and placed his first call to Chris Carver, the famous synchro coach who headed the Aquamaids in Santa Clara, California, and had led Team USA to the Olympics over and over. He'd seen her on TV receiving the Esther Williams award, synchro's version of a lifetime achievement award, and he'd read about her in synchro magazines, which are a thing that exists.

By the time he made that phone call, Carver had heard of him, as had the world of synchro -- the boy from upstate New York, good, not great, doing some better-than-average age-group stuff on the Oswego Lakettes, in a sport so stalwartly female that the names of the teams could also easily be the names of lady-brand cigarettes or sanitary napkins. But all she could think was, A boy! She invited Bill to Santa Clara in the fall of 1995, and there they wrote a duet routine. Among the Aquamaids' coaches at the time was French expat Stephan Miermont, one of the first male synchronized swimmers Bill met.

When it was time to go home after a week, Bill hesitated. Seeing the Aquamaids was like a "mind explosion," he says. There were these California girls, these "tanned beasts" who didn't have to drive an hour just to practice. How could he leave this place, where what he did was taken so seriously and done at such a high level? He asked Carver whether he could come and train with her, and she said yes. His mother was heartbroken. But she prayed on it and realized it was for the best. So Bill's family held back their tears and hugged him goodbye.

The board of the Aquamaids wasn't so easily convinced. The club is technically open to the public, but a boy had never applied for membership and there weren't rules in place to deal with one. How exactly could you integrate him? Synchro's ideal is a group of nose-plugged women looking as close to exactly alike as possible, doing moves that are as close to exactly alike as possible. How do you blend a man into that? What would he even wear?

But Carver didn't think that way. She had her young Aquamaids in the pool at 6 in the morning, lining up their brown-bagged snacks alongside the pool so they didn't have to leave except when nature called. She was so tough and abrasive that her appearance -- blond, blue-eyed, delicate -- became an unsettling comical facade. Carver bred winners in the gold standard and under her mantra: Anyone who has the desire should be able to do it. Bill had that desire. But that didn't persuade the board to let him swim. What, perhaps, did was just the faintest possibility of a lawsuit. Bill was an Aquamaid.

He lived in the homes of host families in Santa Clara. He finished high school and worked at a Baskin-Robbins while he trained. Everyone liked him. Yes, there was the man who booed and the phone call to tell him what a pervert he was. There were the jokes and some ridicule, but there was also something about Bill May that eventually wore people down. Smile.

And he was so happy. Nothing quite gave him the opportunity to tell his story like every pike and every ballet leg and every split and every splash. Smile . He was never able to articulate it until he joined Cirque du Soleil and met the trapeze artists who would say they felt more comfortable in the air. That was it, he realized. He was just more comfortable in the water. Smile .

When Bill was 19, Carver paired him with a young woman from the area named Kristina Lum, a rising star who had been an Aquamaid since she was 8. They began to perform duets together. Kristina would go on to perform in team synchro events at the 2000 Olympics, but she stuck with Bill for the duets, sacrificing a significant portion of her synchro career for someone who might never be able to swim with her in the Olympics.

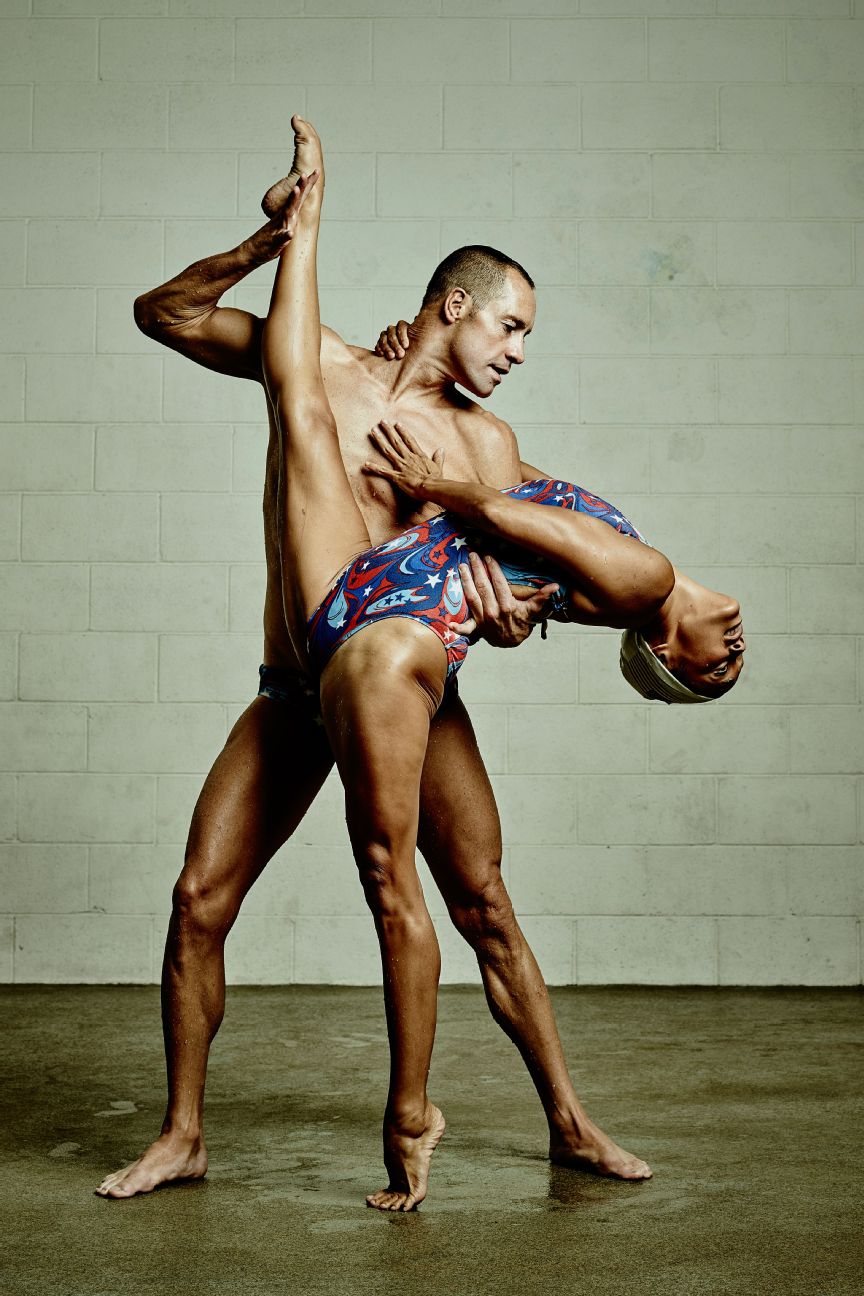

You should have seen them together. Unable to pretend that they were the same gender of swimmer, too different in body and movement to try the traditional synchro approach, unable to find a single bathing suit they both looked good in, they swam routines of romantic interplay, ballroom dancing on the water, often synchronized but never downplaying the fact that they were a man and a woman.

They played Adam and Eve, fig-leaf bathing suits made by a teammate's mother. In another routine, they were snakes, slithering all over each other. They did "Bolero." They did a tango. They were something to watch, Bill and Kristina. There are only so many female-female routines you could pull off. Bill and Kristina were refreshing.

In 2001, FINA met at a congress after the world championship. Bill and Chris Carver were told that an official from USA Synchro would request a vote for a mixed duet to be included in the next world championship. The vote wasn't on the official agenda; the USA Synchro delegate would have to bring it up for discussion.

In the run-up to the congress, the U.S. lobbied hard and got the support of many of FINA's countries, but not Russia. The Russians didn't have a male synchronized swimmer, and they'd just achieved dominance in regular synchro; they weren't going to give up their wins for the sake of gender equity, especially when they knew the Americans had Bill -- that's not the Russian way. But the other European countries were more progressive, and in Europe synchro is considered an art as much as a sport, so Bill was told to wait by the phone for confirmation that his moment had finally come.

But when the call came, he was told the resolution hadn't passed, although not because of any other country's interference. The vote never happened, and it never happened because the U.S. decided not to request it.

Carver was shocked. Bill was devastated -- his own people? He'd thought they were on his side. But he took a breath and he thought, "Hey, this was just part of the struggle, right? Just another hurdle to jump. Just another hill to climb. Just another sports metaphor to sports metaphor." Still, his own people? He couldn't shake the sense of betrayal he felt. But Bill is Bill -- that smile -- so he moved on, never confronting anyone, never even asking who didn't ask for the vote on his behalf.

He continued to train, but something was different. He was tired. Not physically -- getting physically tired isn't something that happens to Bill May. But the struggle was beginning to feel old. By now, his duet partners were retired. Kristina Lum was packing up for Vegas, where she'd gotten a job in the water show Le Rêve -- The Dream at the Wynn. His other duet partner, with whom he swam when Kristina was training for the Olympics, was now a nurse. Bill went to the 2004 Olympics in Athens to help cheer for the team he swam with. It was there that Bill May's essential Bill May-ness began to show its cracks.

As he sat in the stands as a spectator, as someone who was just watching the sport he dominated, he tried to keep in mind how much he had won, that he'd competed in Switzerland and in Rome. He remembered his love of the sport. He did love the sport. He does love the sport. But for the first time, he felt as if he had lost, as if all the goodwill and the skill and the stick-to-itiveness in the world couldn't help him. He was 25. All his original teammates had retired. Maybe it was time to give up and admit defeat.

That year, Cirque du Soleil called and asked whether he wanted to be in its underwater show, O . Stephan Miermont, his old Aquamaids coach, had performed in the show. Bill accepted the offer and packed his bags for Las Vegas and started choreographing his retirement routine.

To get to the synchronized swimming world championship, Bill convinced his partners, Kristina Lum Underwood (left) and Christina Jones (right), to come out of retirement. Kristina is his partner in the free routine, Christina in the technical routine. John Huet

May 2004 Santa Clara, California

On the day in 2004 when Bill May retired from synchronized swimming, the stands at the Avery Aquatic Center at Stanford were filled with Bill's friends and family and everyone he'd ever swum with. Chris Carver introduced him, and Bill came out to applause with his hands spread, neck craning; his routine had already begun. He looked up and around, as if he were an alien who had just landed on Earth. He was wearing a swimsuit that was a patchwork of more than 20 of the bathing suits he'd worn at all the competitions he'd won. Over the speakers, as part of the soundtrack, Chris Carver's voice boomed a prerecorded command, "Focus!" and she counted a quick eight. The music too was woven from much of the music he'd used for routines: "Bolero," "Singin' in the Rain," the Smashing Pumpkins' "Disarm."

A woman's voice was overlaid onto the soundtrack. She said, "Bill, where are you going? Stay here with me." There was the sound of a child cackling. A group of women sang, "Happy birthday to Billy." There were other cries from his lifetime of coaches. There was the news report from the night Princess Diana died, followed by the announcement of John Lennon's death, followed by more of Carver's counting, followed by an old news report about Bill May, about what an oddity it was to see a boy performing with girls, that "an athlete's highest honor, an Olympic medal, is out of reach for a male synchronized swimmer."

In the pool, he kept up with the soundtrack, twirling underwater rockets and pikes and fishtails that showed a frenetic distress, the miming of the opening of birthday presents, a portrait of a man gone mad.

He was going for a "schizophrenic" sort of thing because that's how he was feeling at the time: of many minds about his past and future. He tells me it was almost like a call to arms. Like, this is your final destiny. This is where your career ends and something else starts.

The routine finished on Sinatra's "We'll Meet Again," with Bill reaching up out of the pool with his left arm at something unseen while his right arm and legs flailed just below the water line to keep him afloat. And then, as the music ended and the applause swelled, he slowly sank beneath the surface, down, down, down, until you could no longer see him from the stands.

John Huet for ESPN

May 18, 2015 Fremont, California

Two months before flying to Kazan, Bill, his tech duet partner, Christina Jones, and I went to dinner at BJ's Restaurant and Brewhouse, a high-ceilinged sensory assault of an eatery that serves just about every kind of food. Bill asked whether I'd ever had a Pizookie. I told him I hadn't even heard of a Pizookie, and his eyes rolled and he told me to just wait until dessert time. A Pizookie is a warm ice cream sandwich that is served at this particular restaurant in a round tin reminiscent of a pizza. I told him I'd try it. Christina rolled her eyes and told me that on the way to the restaurant they passed an ice cream store that said "World's Best Milkshake" and Bill wanted to stop. He reminds her of Will Ferrell in Elf sometimes.

Bill and Christina were in California visiting Chris Carver. This was how it went these days: They'd perform Wednesday through Sunday in O on the Strip. While they were there, Carver would travel to them and they'd practice in the mornings before they each performed in two shows per night at Cirque. On Mondays, they'd head to the Santa Clara area, and they'd train morning and afternoon with Carver until it was time to go back on Wednesday.

Christina Jones is a Santa Clara purebred: tall and strong and blond-haired and blue-eyed and confident. She had never performed with Bill because of their age difference -- she's now 28 to his 37 -- but of course she knew who he was because he was a legend. In addition to competing nationally and internationally, the Aquamaids put on local pool operas, elaborately staged ballets for the community featuring their best swimmers, and young Christina Jones once sat in the bleachers, her jaw open in early ambition. She would go on to place first in the Pan Am Games in team and duet in 2007; she retired after placing fifth in the duet and team events in the Beijing Olympics in 2008.

In the fall of 2014, Christina was in bed when she opened her phone and saw an email from USA Synchro's CEO, Myriam Glez, saying that a mixed duet was finally being evaluated for inclusion in the FINA World Championships. Christina had been considered as Bill's potential tech partner because she is his same height and because she remains an excellent swimmer from her Cirque performances. She didn't read past the first paragraph. Instead, she shut her phone off and began to cry. She turned to her boyfriend, who is also a performer in O , and said, "I can't do this." But then she got out of bed and found an old competition suit in her closet, and she put it on and she jumped around, talking about her synchro days and Bill and all the competitions. "I can't do this," she said again. But her boyfriend looked at her, suddenly electric inside her old costume, and said, "Look at you. You're alive. You have to do this."

“But for the first time, he felt as if he had lost, as if all the goodwill and the skill and the stick-to-itiveness in the world couldn't help him.”

Kristina Lum was another story. Whereas Christina Jones had been chosen for her ability to synchronize well with Bill, which is what a tech routine is all about, Kristina was his rightful partner in free routine for the way they combined to become a thing of balletic beauty in the water, for all their history. She was the Ginger to his Fred, the Pippen to his Jordan. But Kristina was now Kristina Lum Underwood, married to another performer at Le Rêve . She had a child and was pregnant with her second when she got that same email. Kristina had given up no small number of duet opportunities because of her refusal to partner with anyone but Bill. This was all they'd ever wanted. But it was 10 years later, and well, would there be time to get in shape? Would there be time to commit to the practices with two kids and two Vegas shows each night? Who knew what it would be like to have two children instead of one? But her husband looked at her too and said, "You have to do this." She agreed. Then she didn't. Then she did.

Still, it was all theoretical until Nov. 29, 2014, when, after the second O performance of the evening, Bill and Christina received an email from USA Synchro president Judy McGowan that said: "As promised when we spoke in Vegas, FINA just passed the mixed duet. It will be in KAZAN.-yeah!"

They were in their dressing rooms. They wandered out into the hallways and met. They cried and hugged. That night, Bill texted Kristina Lum Underwood's husband. Kristina was now seven months pregnant, and it was close to midnight and Bill didn't want to be inconsiderate. But Kristina was awake and she looked at the phone, and she looked down at her belly and at the sleeping toddler in the other room, and her husband reminded her, "You have to do this," and she remembered that she had to do this.

Bill called Chris Carver and left a message, telling her the news and asking whether she'd be up to coaching. Chris was so overjoyed and numb -- was this really finally happening? She didn't call him back that night. She emailed him, saying that she'd call him back the next day, that she was crying with happiness for everyone. She never had to say yes. Her yes was always a given. She signed the email, "I sure do love you, Chrismom," which was the last sentimental thing she would say until the very end.

They got to choreographing. They used community pools around Las Vegas to practice, renting them out for as many hours as their schedules allowed, subject to all the degradations of community pools: old women doing aqua aerobics on the other side of the rope; children cannonballing into your part of the rented pool before a lifeguard can get to them and tell them the space is yours; a kid taking a dump in the pool, sidelining them from practicing for a full hour while the water rechlorinated. Chris Carver had flown in from Santa Clara that day, and they didn't like to waste time, and maybe saying the pool had rechlorinated by the time they got back in was generous. The only breaks they took were when they had to use the bathroom or when Kristina's husband brought her newborn by for nursing. Bill put over $40,000 on his credit card for pool rentals. USA Synchro could pitch in only $12,000 total. The rest would come from the formidable Aquamaids, who operate a long-standing and very successful bingo facility in Santa Clara, run by volunteer Aquamaid parents in charge of getting funds to the swimmers for costumes and competitions.

Bill still swam the two Cirque shows and put an hour's worth of makeup on each night. He still taught an abdominal workout to the other O cast members three times a week, twisting and lifting and pushing impossibly to get every single angle of their trunks to resist and grow stronger, to get them looking more like Bill. And he still swam his regular workout, an hour back and forth and back and forth in the pool each morning, and at night, when he was showered and his Weimaraners lay at the foot of his bed and he ceased movement for just the few hours he slept, he dreamed of Kazan.

That night at BJ's, the Pizookies arrived -- Bill's first, but he waited until I got mine to begin. A week after our dinner, he would stop eating candy and ice cream to get into shape for Kazan. A guy who hasn't made time for a romantic relationship in five years, a Mormon who doesn't drink caffeine, would be left with no distractions and no vices. He would be left only to train.

The Pizookie was not as good as Bill May said it would be, but it seemed important to him that I like it, so I rolled my eyes back as well and said it was delicious, and the whole time I was thinking that I wish in my life I had ever enjoyed any one thing as much as Bill May was enjoying this dessert right now.

After retiring from synchronized swimming in 2004, Bill became a swimmer in the Cirque du Soleil show "O" in Las Vegas. John Huet

May 18, 2015 Santa Clara, California

"I need to be put to death," Chris Carver said into a microphone from her small steel hut on the side of a high school pool. She is in her 70s, with white hair cut like a Dutch painter's and a face full of disappointment bordering on disgust. And could she be honest for a minute? If she was honest, if it was OK to confess something, it was that all she really wanted right now was for someone to kill her. "Euthanize me. Please." There were under-water speakers so Bill and Christina could hear the music for their routines, but also so they could never miss any of her missives when their synchronicity wasn't up to the exacting standards of her neurological perception, which is an eighth wonder of this world.

Bill and Christina bobbed to the surface, their heads perfectly still as a hundred mechanisms of the veteran synchronized swimmer, from an eggbeater to some good old-fashioned sculling, kept them afloat from below. They wore goggles and nose plugs, and their faces were covered in a thick layer of diaper cream. They were in the pool six or eight or 10 hours a day; there was no amount of drugstore sunscreen that could keep up with them. They awaited Chris Carver's feedback. She continued to beg for the sweet release of an immediate death.

This was nothing to Bill. Back when he was one of her full-time swimmers, back before he was an adult asking her to put her life on hold and train him as a favor, she would watch some of his elements and her verdict on them was that she would see him in hell. Once, after a particularly disappointing hybrid, she told him he looked like diarrhea. Perhaps the best possible description of Bill May is that when she said that, he couldn't help thinking while she yelled at him what a nice-sounding word "diarrhea" is.

Summer was coming. It was already May, and worlds are in July. Bill's other partner, Kristina Lum Underwood, was still in Las Vegas, working and taking care of her kids. The calendar was breathing down their necks.

Bill suggested that perhaps they should change their legs into a stronger position in the first hybrid, maybe a rocket, and at this Carver might have had one of those small strokes they detect only much later through blood work. "You can't still be changing things," she yelled. "You are always trying to change things, and it's May already and you need a routine!"

Chris Carver has been Bill's lone champion for many years. She met with resistance from the outside, from the inside, but still she remained his hardest-working advocate. But now that what they fought for had happened, she was left to figure out how to actually do it.

Christina Jones likes to show people a picture on her iPhone in which she and Bill are inverted, underwater, just with ballet legs poking out, and ask, "Whose legs are whose?" (I guessed wrong.) But still, Christina is a woman, and women more easily synchronize with each other than with men. (Can I get an amen, ladies?) So accommodations had to be made for the synchro moves, since the judges' detection methodology is so precise. They had to organize ways to appear the same, Bill slowing down, Christina speeding up, Bill jumping midway while Christina jumped high, only to be at the same level.

And their bodies are so different. Bill and Christina had been assessed at Cirque recently, as they are every year, and Bill's body fat was under 10 percent. "Christina, you're a cork," Carver yelled into the mic as Christina surfaced at twice Bill's speed. Maybe because of all of this, synchro's evolution into a single-sex sport was inevitable.

So when it was time to begin choreographing for the mixed-gender duet, nobody in the world of synchro quite knew what to do. Were they supposed to act like two girls doing synchro together, letting men in only on their terms? Or would they change the nature of the sport by turning the choreography into a water dance between a man and a woman? No new scoring guidelines were established. Everyone was lost.

Chris Carver decided to go all in on the man-woman thing and hope for the best. Her tech routine for Christina and Bill involved some deck work that is about her rejecting his advances, her diving away with him following. The free routine with Kristina overtly plays up her femininity and her smallness next to Bill, and he employs a strange double-jointedness in his shoulders to be scarier and larger than usual.

"If you're trying to look alike, why bother?" Carver said. "Why bring men into a sport and not change it?"

She oversaw the final practices, traveling back and forth, Santa Clara to Vegas, showing up in her devoted way, and said things like: "I was a big Breaking Bad fan. That jump reminded me of when they cut the guy's head off and put it on the turtle and it was just walking around."

In June, at the pool at the Henderson Multigenerational Center outside Vegas, Bill and Kristina Lum Underwood practiced their free routine. They were beautiful, wrapping their limbs around each other, no technical requirements to work around. He grabbed her, she fled, he grabbed her, she fled, he swallowed her up. Bill turned from Bill May to something nefarious. Kristina turned from Kristina Lum Underwood to something to be captured and possessed. Carver beseeched them to be flawless, "the way the Americans used to be." Bill missed a turn.

"You know," Carver said, "my dog has indigestion, so I've been giving him Pepcid AC." I'd been on this story for months now, and even I knew that this wasn't an innocuous statement, that she wasn't just telling a story.

"Do you need some Pepcid AC, Bill?" she said.

Bill didn't answer. He knew it was a trap.

"Because you're having brain farts."

Bill and Kristina have been performing together since they were teammates on the Santa Clara Aquamaids. Lum Underwood competed in Olympic team synchronized swimming. John Huet

July 18, 2015 Las Vegas, Nevada

The time to fly to Kazan arrived, and it didn't matter who was prepared and who wasn't. It was time to find out whether Bill would be a world champion. They all got ready, steadied themselves for what came next, a brief bracket of time that would come to define them, that would wreak havoc, good or bad, on their Wikipedia pages.

Chris Carver handed over day-to-day operations of the Aquamaids. Kristina Lum Underwood weaned her baby from nursing, and for the last time until after Kazan, she kissed her children and her husband and she looked out into the crowd at Le Rêve . Then she headed for the airport. Christina Jones walked her dog and cried on her boyfriend's shoulder, still unable to believe that this was happening, worried that the mantle of the legacy of no less than the career of Bill May rested too much on her shoulders.

And Bill May taught the last ab class to his colleagues at Cirque and played with his Weimaraners one last time. He told the teams he helps coach, the Desert Mermaids and the Water Beauties, that he'd be back soon. He performed his final shows at O , then he and Christina performed their routine in the pool onstage for their colleagues to thunderous applause. He prayed to God and his late grandmother, asking her to look out for him, to make sure God was on his side for this one. He turned a blind eye to the sour-sweet licorice he loves so much that haunted him from a jar in his kitchen. He swiped his credit card at the pool one more time, trying his hardest not to think about how high in the five digits the numbers were now. He turned his head away when he drove past BJ's, for he couldn't fall prey to another Pizookie. And he tried to take it day by day, tried to think that the stakes weren't quite as high as they were, that his body wasn't 10 years older than it was when last he smiled up at the judges. But the stakes were even greater now, and his body was 10 years older than it was then. It was one thing to be known as the man who could have been a contender if only he'd been allowed to show up. It was another thing to be invited and not win.

Dee O'Hara, Bill's first coach, boarded a plane to Kazan to see Billy go all the way. Bill's mother and sister boarded a plane. Team USA boarded its plane in matching warm-up suits. Christina Jones boarded the plane. Kristina Lum Underwood boarded the plane. Chris Carver boarded the plane. I boarded the plane.

And Bill May, wearing his regulation USA Synchro backpack, boarded the plane. The door shut behind him, and he took out an airplane pillow and tried to sleep before landing in Kazan.

Bill had the talent to be a gymnast or speed swimmer, but he was drawn to the combination of art and athleticism in synchronized swimming. John Huet

July 24, 2015 Kazan, Russia

The night before the tech preliminaries, Bill FaceTimes me from the athletes village, and when I answer, there is a cookie in the shape of a man on the screen instead of a person. "Hi, Taffy," says the cookie, and then I hear his Bill May laugh -- heh, heh, heh -- from his solar plexus to mine.

"So you're nervous," I ask the cookie.

"Yes," says the cookie, and the cookie nods.

"Not really," Christina Jones interrupts, pushing the cookie out of the way so I can see her. "Nervous implies we're not prepared. I'd say we're more anxious ."

To be clear, the goal at Kazan isn't just to win. The goal is to put on enough of a show that FINA decides to recommend this to the IOC as an event. It might be too late for Rio -- though they gave the swimmers only seven months to practice for worlds -- but there's Tokyo in 2020, and Bill will be only 41 by then. Still, 41. But make no mistake, the goal is also to win. And if I had bought the line about putting on a good show in the months leading up to Kazan, I no longer did.

The Russians are plucked from their amateur teams the moment they show talent, and they're sent to an incubator. The Russian male competitor was just a boy when he was moved to St. Petersburg to train. He is 16 years younger than Bill, and some things had changed a little since Bill's retirement. In Europe, men had started doing synchro -- just a few here and there -- many of them claiming to be inspired by the American, Bill May. But even now, the Russian is an oddity in Russia. He's its only male synchronized swimmer too. The Russians weren't always on board with male synchro, but once they were able to field a team and achieve dominance, they didn't have the same issues of camp and dubious masculinity that accompanied the questions that have surrounded Bill. In Russia, all athletes are regarded equally as heroes, as long as they win. In Russia, you're paid a salary with a pension so you can train full time and bring glory to the homeland. In America, you're working two Cirque du Soleil gigs and charging up your own credit card for pool rentals.

And at this point, what kind of person are you if you're not rooting for Bill May? Bill May, who will swim in a pool that still has some kid poop in it so he can get an extra hour of practice. Bill, a man who swam with women training for the Olympics, women who could complain about how tired they were and how sore they were, and Bill would keep his mouth shut thinking how he'd kill to be on the road they were on. Bill, who learned from me that it was Judy McGowan, the president of USA Synchro, who did not request the vote that day in 2001, on the day she promised she would -- she'd been ready to ask for the vote but was stopped by the president of FINA at the time and told that it was not in the best interest of the sport and its place in the Olympics to bring men in just now.

Yes, when Bill heard this from me, his immediate and only reaction was to say what respect he has for Judy, doing the right thing for the sport, fighting the way she always has for synchro, that it must have been a tough decision and that if she had received that vote, if he had been allowed in, well, he might even have been deprived of this moment he was having now, and what a shame that would be. Bill May, who represents the gifts that hard work and good intentions can sometimes bring. And now it's time to ask yourself again: At this point, what kind of person are you if you're not rooting for Bill May?

July 26, 2015 Kazan, Russia

And finally, after seven months of training and waiting and applying (and removing) diaper cream, it is time for Bill May and Christina Jones to compete in the tech finals. The Americans had lost the prelims to the Russians. It is hard to see how any improvement in their own routine could outdo the home-pool team. Still, Bill May leads onto the deck with his enormous smile -- his real, full one this time -- as he front-flips in his bright coral Speedo, followed by another flip and another while Jones stalks out on long legs onto the fore. He makes a show of trying to get Christina's attention, but she ignores him. He walks up to her and moves her chin to look at him, but she pulls away. He tugs at her shoulders, still nothing.

Eventually, Bill stands behind Christina, pointing right at her back, like "I've got my eyes on you," and they hold frozen for a moment, indicating that the deck work is over and that they are ready to start the routine. Christina wears a matching coral tank suit that, in describing how she wanted it to the costume maker, she asked to be "dripping in sparkles." (It is.)

The whistle sounds, and Christina, with her mile-long limbs, pulls up her leg and makes a loop of it with her arm, and Bill dives right through, into the water. Christina dives in after him and they plunge toward the bottom of the pool (but never at the bottom; they're not allowed to touch the bottom) to set up their jump, and then Christina darts to the surface, propelled by Bill's strength from beneath her. They both burst out of the water, smiles intact. They'd wanted their routine to be a big, splashy American thing, straight out of a time that exists only in American memory, that maybe ever existed only on a screen: bright smiles, fast moves, jazz hands, wholesome romantic jockeying, all soundtracked to a Harry Connick Jr. song called "Just Kiss Me," about a man who wants his vain girlfriend to stop applying red lipstick and just make out with him.

But this isn't Rocky IV , as I learned in my first few days in Kazan. These are not people who can be moved by the American spirit made manifest in bright smiles and jazz hands. No, in the muted, begrudging applause for Bill and Christina as they took the stage, suddenly it's easy to remember that maybe placing your bets on people loving America is no longer a great thing to do. We are no longer the people who helped topple communism.

The night the Russians won the preliminary tech routine, Chris Carver wrote to me that she was devastated, that she'd known the Russians were good, but my god, that routine. And Bill and Christina wrote emails saying how disappointed they were, asking would this affect how my story comes out, that I should know that they're prepared to just "leave it all in the pool" for the finals.

There had been very few reporters in the arena for the synchro events -- the media seemed generally more interested in the big-boned water polo players and poetic free divers. But now, for the finals, the media area is more crowded. All the FINA officials are also here, and I'm told later that it was the only event that all the officials had attended at the same time. I watch the officials shake hands with each other and take their seats. My energy is low. It's hard to think of any outcome that doesn't include the Russians, already dressed for totalitarian rule, being named the country's new leaders.

But Bill and Christina! They light up the room. This time, they seem to fill up the pool, their strokes crisper and more in sync, more mesmerizing. Their smiles are more playful and more arena-encompassing. That insipid Harry Connick Jr. song sounds new somehow, it sounds welcoming, not like the bombs falling and exploding. On the other side of the pool, where the teams and the people of Kazan have seated themselves, there is at least some faint clapping with the beat.

Their routine goes by in a flash of perfect synchronization and thousand-toothed smiles. And so they swim to the ladder, and they climb out of the pool, and they hug Chris Carver and Kristina Lum Underwood, both of whom are crying now (right along with me as a Russian reporter sneers that I should be more professional), and Bill and Christina remove errant pieces of bathing suit from between their butt cheeks while they move to the pool deck to await the score.

But the people of Kazan, their applause is still not deafening. The Russians, who went before the Americans on this day, stand in the wings, where Bill had been one day before as he and Christina had watched them. They are smiling. Because how could Bill and Christina possibly top the Russians? In Russia?

The numbers tabulate, and the swimmers look with stiff smiles at the board. Christina realizes the number a millisecond before Bill, and she takes a breath, almost as if she has been sucker-punched, and her face turns immediately from gracious athletic professional to motherf---ing world champion. Because, holy crap -- it's the Americans! Christina hugs Bill, whose face is a panoply of awe and openheartedness.

Their score is 88.5108 to the Russians' 88.2986. Within seconds, it looks as if Bill and Christina had been crying for hours. Carver cries too, because although she talks big, she has the same gooey center we all do. I cry, real red, white and blue tears, and stand to sing "The Star-Spangled Banner" loudly in ear range of that Russian reporter, and the winners mount the highest level of the podium, and a gold medal is placed around their necks. Bill kisses his and looks to the sky.

Bill and Christina are all smiles after winning the first gold medal for mixed gender technical duet at the Federation Internationale de Natation World Championships in July 2015. Matthias Hangst/Getty Images

July 30, 2015 Kazan, Russia

The Russian woman actually sneers when she sees their score, and her partner makes sure at the post-swim news conference to highlight the negligible difference in scores, a difference that did not bother him when the outcome favored him. But the free routine final remains. Bill and Kristina had won the preliminary free routine four days earlier and seem like a lock in the finals.

Their routine is lovely, but again, there are no guidelines, and perhaps it is too free, and results are not always clean and the world championship is not a movie and life is not fair -- this we all know by now. The judges seem to want something more traditional, something that promises them the changes that they are consenting to by judging a mixed-duet routine, by judging a man, won't be too harsh. So the Russians ultimately win with a mostly synchronized, sexless, genderless display of "Swan Lake."

At the post-swim news conference, Kristina Lum Underwood's children and husband clap for her and she says that she's given it her all and that she is proud, but a quarter of a point is a devastation if it's going in the wrong direction, maybe even more so than five points. It is only her years of good sportsmanship that keep Kristina from flipping the table and walking away, so convinced are we that the American free routine was better than the Russian one.

For the longest time, Bill couldn't get into Olympic qualifying events because he couldn't get into the Olympics. After winning the world championship in Kazan, he is closer to his Olympic dream than ever before. John Huet

At 2 a.m. in Kazan, we board a Turkish Airlines flight and go home, back to our lives. Chris Carver reunites with her dogs in Santa Clara, coaching the best swimmers on the Aquamaids, glorying in the win that seems to round out her career, still silently angry that the victory wasn't complete. The distance between nothing and a bronze medal is 100 miles. The distance between a bronze medal and a silver, 50. But the distance between a silver and a gold, well, they're still measuring, and they're not even close.

Christina Jones stops in Barcelona to meet some friends on the way back, with only her gold medal to her name after Turkish Airlines lost her luggage. She eventually makes it back to Vegas, to her dog and to her boyfriend, and to her friends at Cirque, who cheer when she arrives in the room. Eventually her luggage makes it back to her too. If the Olympics happen, she'll consider them. She never thought she'd go back to competing, but now she is a world champion; the thrill of winning is back in her bones.

More From Doubletruck

Doubletruck is the home for ESPN storytelling, a place to find great features, investigations and character portraits.

Doubletruck home »

Kristina Lum Underwood goes home to her kids and her husband. At work there is a huge display of Americana memorabilia and pictures waiting for her, courtesy of the co-workers who had been rooting for her stateside. On her finger now is a ring that she and Bill had made for each other, silver nose plugs to remind them that they came back, that what is over is never truly over while still you dream of it. They promised to go back to seeing each other maybe once a year, hi/bye, their lives being so different despite being the same, but they will have the same intimate familiarity they always did, of people who did something very special together a long time ago. If mixed-gender duets make it into the Olympics, she doesn't think she'll train. She's 40. The kids and the job, it's enough.

And Bill May, after eviscerating the Kazan airport's chocolate rations and relieving the Istanbul airport of its supply of ice cream, goes on a cruise to Alaska with a few of his swim team buddies, where he eats more ice cream but eventually comes home. He crouches in his doorway as the Weimaraners run to him and over him. He calls up his swim teams, ready to start training with them again. He walks into work at Cirque, and he too is cheered a welcome home by his friends.

The three of them, Bill and Christina and Kristina, are given a day of their very own in Las Vegas -- Sept. 16, 2015. The mayor hands them proclamations, and they stand straight and tall, in athlete mode, as they receive them. In California, Chris Carver is inducted into the San Jose Sports Hall of Fame.

Right now, there is not yet word on the Olympics, whether Bill will be allowed to compete in 2016 in Rio or in 2020 in Tokyo. Judy McGowan says that FINA still must make recommendations to the IOC but that she's hopeful: Whereas saving the sport all those years ago relied heavily on keeping it all female, the world now is a place that is leaning toward obliterating strict notions of gender completely. She doesn't regret not requesting the vote; her job was to protect the sport. But she would be lying if she said she wasn't crying along with the rest of us in Kazan.

I am home too. I've given my children their matryoshka dolls, and I've recovered from my jet lag and treated my heartburn and am on to my next story. I text and email with Bill and Christina and Kristina and Chris, and I try to explain to people how beautiful it was to see someone do the thing he was meant to do, but also the thing he was told repeatedly he never would. People nod, and I wonder whether they get it, whether I've conveyed it effectively.

These stories are a tragedy in a way: You walk into people's lives at the moment that something monumental is happening to them, and then you leave when it's over, as if you are the one marking their journey for them. Eventually I'm left with only memories of my tears and my breathlessness, and what it was like to be the only person in a stadium screaming and jumping. Now my memories are fading a little, and all I have is the fact of them. I can no longer feel what I felt when I was there. I can only remember the fact of the tears, the fact of the screaming, all of it.

But there is something that lingers: Since Kazan, every night in bed, when I hold for a few minutes in that space between when you're awake and when you're asleep that is a monster of memory and mirage, all the pictures of Bill's glorious days in Kazan morph into one. In my hallucination, it's Bill, in his warm-up suit, holding his gold medal in one hand and waving with the other, his smile extending beyond the borders of his face, his eyes wet but not quite crying, the moment after everything he has worked for in his life, everything he once hoped for and gave up on and hoped for again, has come true.

But in my hallucination, he is not standing on the podium. Instead, he is in the water, and he is propelled from his lower waist upward out of the pool, just like back in Tonawanda, by sheer will and energy and hard work and expertise and dedication and all that is good in an athlete, all that is good in sport and competition, and all that is good in a person. And as I fall asleep, he remains eternally waving, and his smile continues to grow beyond the borders of his face until it fills up the world.

- join the conversation

- follow @taffyakner

- follow @ESPN

More Stories

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Disney Ad Sales Site

- Work for ESPN

- Corrections

When Solo Synchronized Swimming Was an Olympic Sport

By mike rampton | jul 8, 2021.

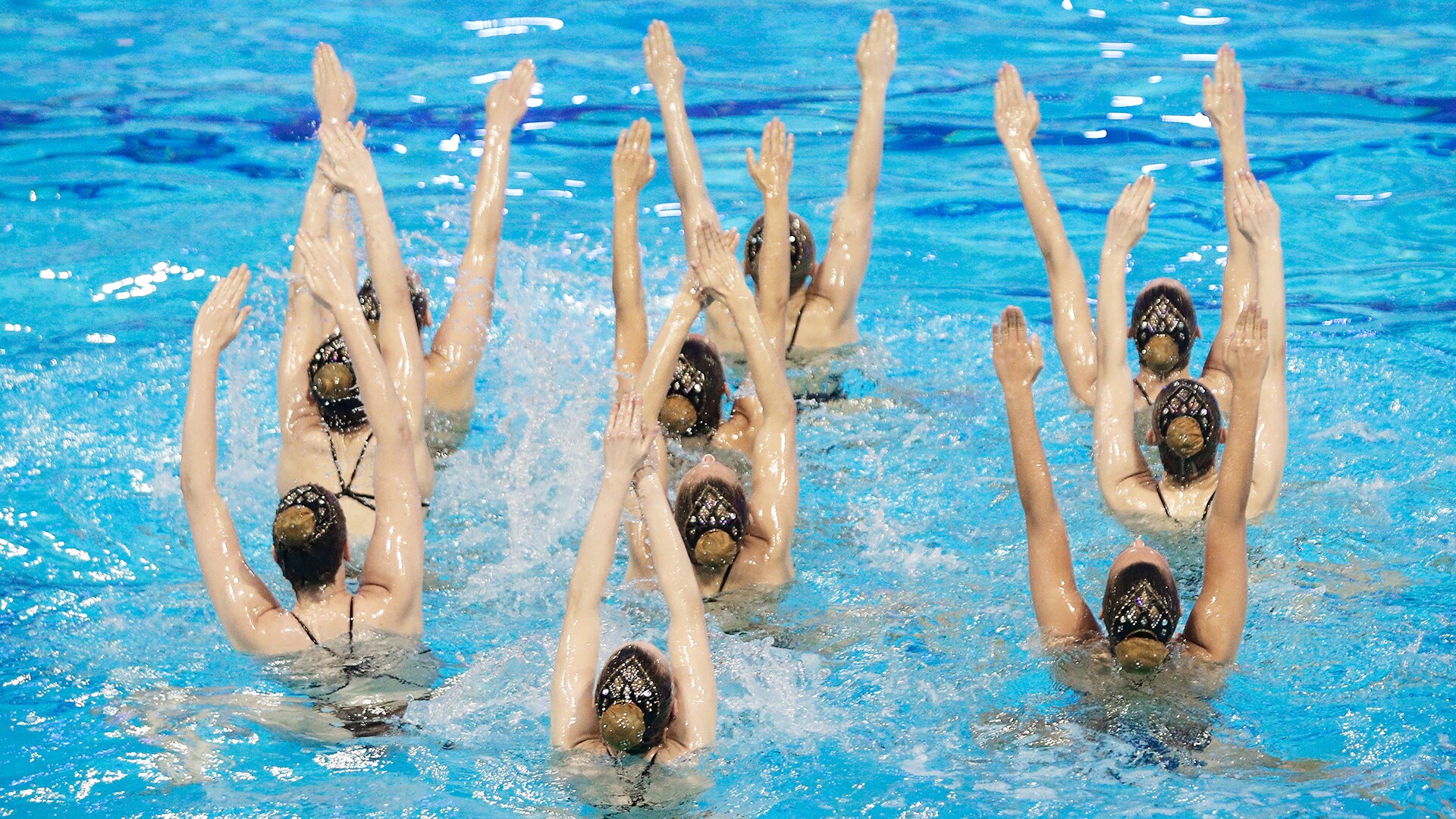

Ask most people about synchronized swimming and they're likely to picture something like the squad in the opening credits of the second Austin Powers movie —an endless line of identically-dressed women in nose plugs, doing perfectly-matched movements in a pool.

At the Olympic level, however, the sport is fiercely competitive, with swimmers in the duet and eight-woman categories vying for medals by executing expertly choreographed moves in perfect formation. But when synchronized swimming was first introduced as an official event at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games, it came in three varieties: duet, eight-woman—and, strangely, solo .

Putting the synch in synchronized

Technically, the synchronizing in "synchronized" swimming is to the music. But it's much harder to tell how good a job one person on their own is doing when compared to a team moving perfectly both to the music and with each other. With a solo performer, it kind of looks like either a swimmer who is also great at ballet or a ballet dancer who kicks ass at swimming. For a non-expert, unless someone starts visibly drowning, there’s essentially no way of knowing what does and doesn’t suck. Which perhaps explains why solo synchronized swimming's presence at the Olympics lasted for a mere three games, from 1984 to 1992 .

Solo synchronized swimming still exists outside of the Olympics, however, as both technical and free solo events. Technical solos involve following a set routine, while the free solo event at the FINA World Championships is quite a sight to behold, as the athletes regularly—and elegantly—execute swan dives, inverted pirouettes, and various other aquatic gymnastics.

“Solos really allow individual athletes to shine and express themselves, which may not necessarily happen if they only swam in a team or duet,” Christina Marmet, former competitor and founder/editor-in-chief of Inside Synchro (a website that dubs itself "the ultimate website for everything artistic synchronized swimming") tells Mental Floss. “Solos are a big driving force behind the evolution of the sport. That’s where athletes can flourish in technique, difficulty, artistry, and create new movements, new ways of moving in the water. At the lower age-group levels and nationally, solos are very important. They are a really great way for younger swimmers to improve their individual skills, to get stronger technically, to be more confident, and to gain some visibility to move on up to better clubs or to the national team.”

A foot to the face

While solo synchronized swimming won’t be on the schedule of the Tokyo Olympics later this month, nor will any other synchronized swimming—though it's all a bit semantic. In 2017, "synchronized swimming" was rechristened as "artistic swimming" in order to bring it in line with how gymnastics is described.

The other thing you won’t see? Dudes. While the World Championships have male, female, and mixed events, Olympic artistic swimming is an all-female affair, as men are not allowed to compete. In 2017, FINA did push to have a mixed duet event added to the roster for the 2020 Olympics, particularly considering its popularity in Japan, but it didn't happen. This is something Marmet hopes will change at some point, along with the general perception people have of the sport.

“One big challenge for the sport in general is to be taken seriously,” Marmet says. “People make fun of the sport itself, of solos, of the looks, and don't realize how difficult it is or how much work goes into it. Sure, we sometimes shoot ourselves in the foot with over-the-top makeup, headpieces or swimsuits. But it’s hard. Competitors never touch the bottom of the pool, and train eight hours a day every day in the water and on land.”

It is hard. Something you may well see are concussions. Artistic swimming, particularly in large teams, is extremely dangerous—with lots of fast-moving feet colliding with slower-moving heads. In 2016, Myriam Glez—then-chief executive of USA Synchro, the sport’s American organizing body, and a two-time Olympian—told The New York Times that being concussed at some point was all but guaranteed, saying, “I would say 100 percent of my athletes will get a concussion at some point. It might be minor, might be more serious, but at some point or another, they will get hit.”

Solo synchro might sound a bit silly to some, but at least it lessens the likelihood of a foot to the face.

Where Did ‘Synchronized Swimming’ Go?

More than 30 years after its Olympic debut, the sport was rebranded as “artistic swimming”—a controversial move that athletes fear could backfire.

If you’ve been watching the Olympics, you may have noticed that synchronized swimming has a new name. In July 2017, the International Swimming Federation, or FINA, announced that the sport would be called “artistic swimming,” effective immediately. Not everyone was a fan—to put it mildly.

“‘Artistic Swimming’ sounds like something society ladies did with their bosom friends at garden parties or after tea in the early 20th century,” wrote Jessica Lewis, one of more than 11,000 people from 88 countries who signed a petition against the renaming at the time. “Synchronized swimming is a REAL sport for REAL athletes.”

The change may seem minor to outside observers, but it has unleashed a furious debate over the sport’s identity and future. The majority of those within the world of synchronized swimming, or “synchro”—one of two women-only Olympic sports—had no inkling that the change was coming. Within days, Kris Harley-Jesson, a former synchro swimmer who has coached national teams in Europe and North America, had launched the aforementioned petition. Thousands of public comments written in multiple languages poured in, including from current and former swimmers and coaches at all levels of the sport.

Their concerns were numerous—that athletes did not appear to be consulted in the decision, that removing the word synchronized would erase the very essence of the sport, and that the financial cost of rebranding would fall to the teams themselves. But the biggest concern, by far, was that the term artistic would detract from the athleticism of the sport, which has always faced an uphill battle to be taken seriously. As one commenter wrote, “Synchro swimmers had a hard enough time convincing others that their sport is a real sport and is hard to do, without it having a ridiculous name.”

The change, according to multiple sources, including former FINA Executive Director Cornel Marculescu, came at the behest of International Olympic Committee President Thomas Bach, who thought a different name could better serve the sport. But regardless of the original impetus (the IOC declined my request to speak with Bach), synchro has lost the identity it had for more than eight decades. Now many athletes worry they could also lose the respect they spent so long earning from skeptics.

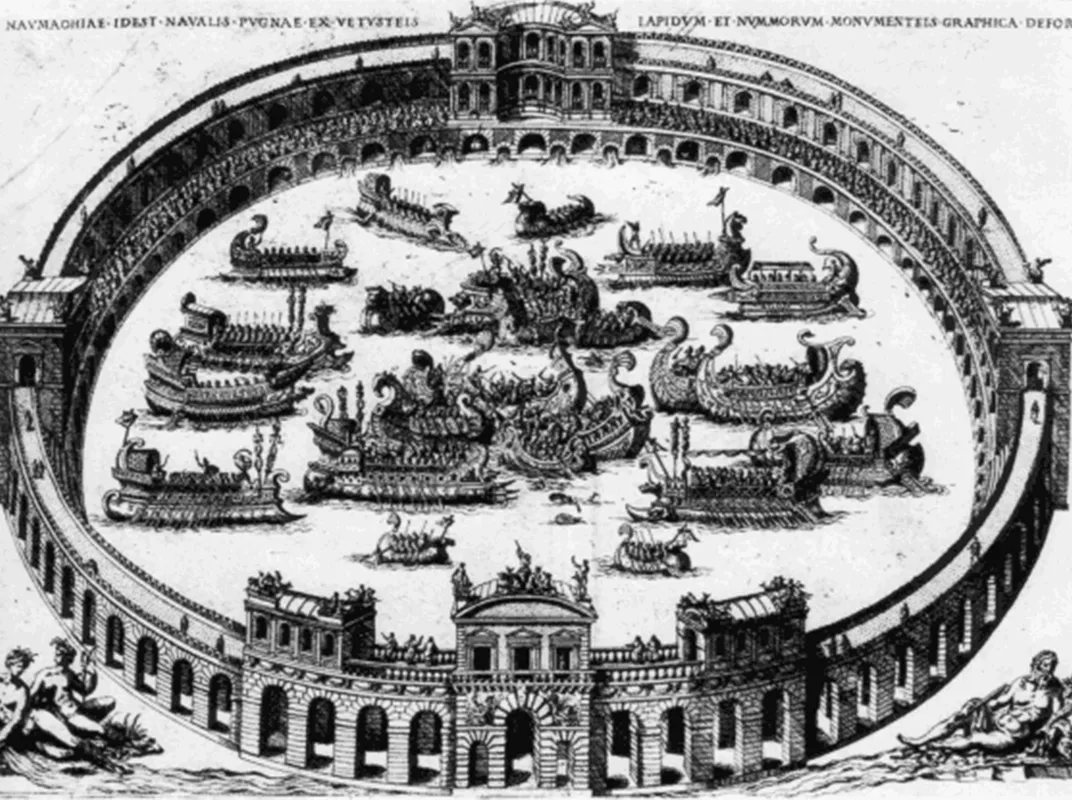

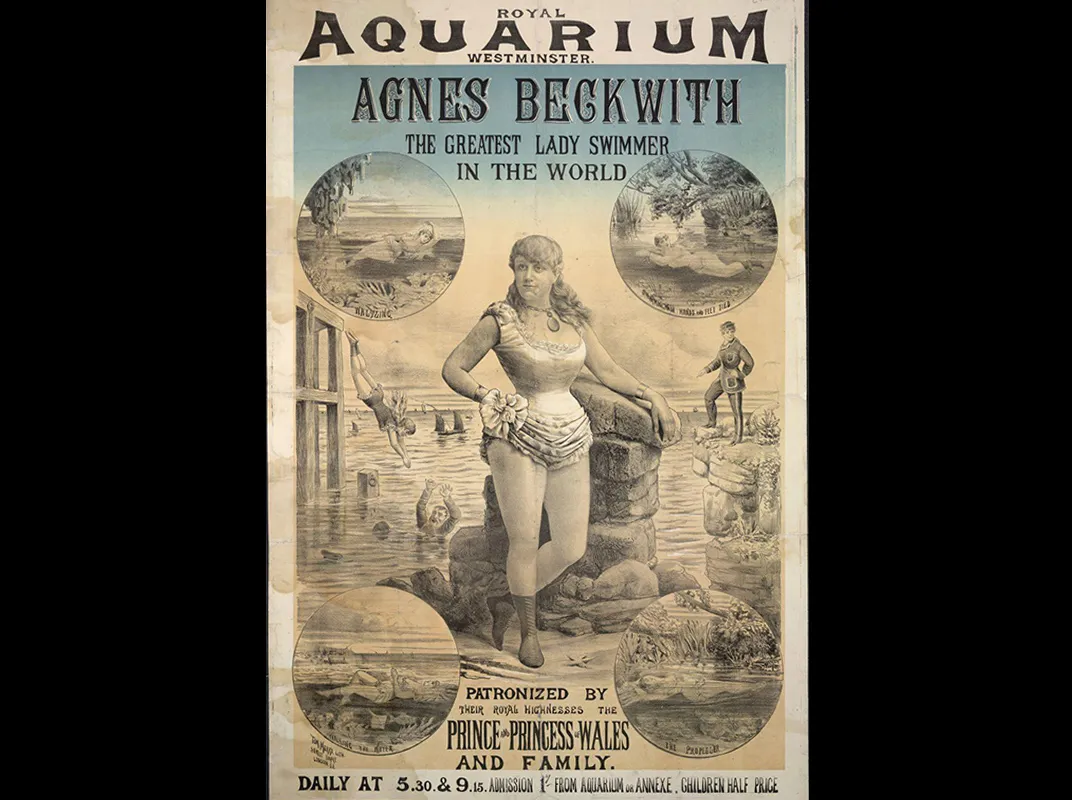

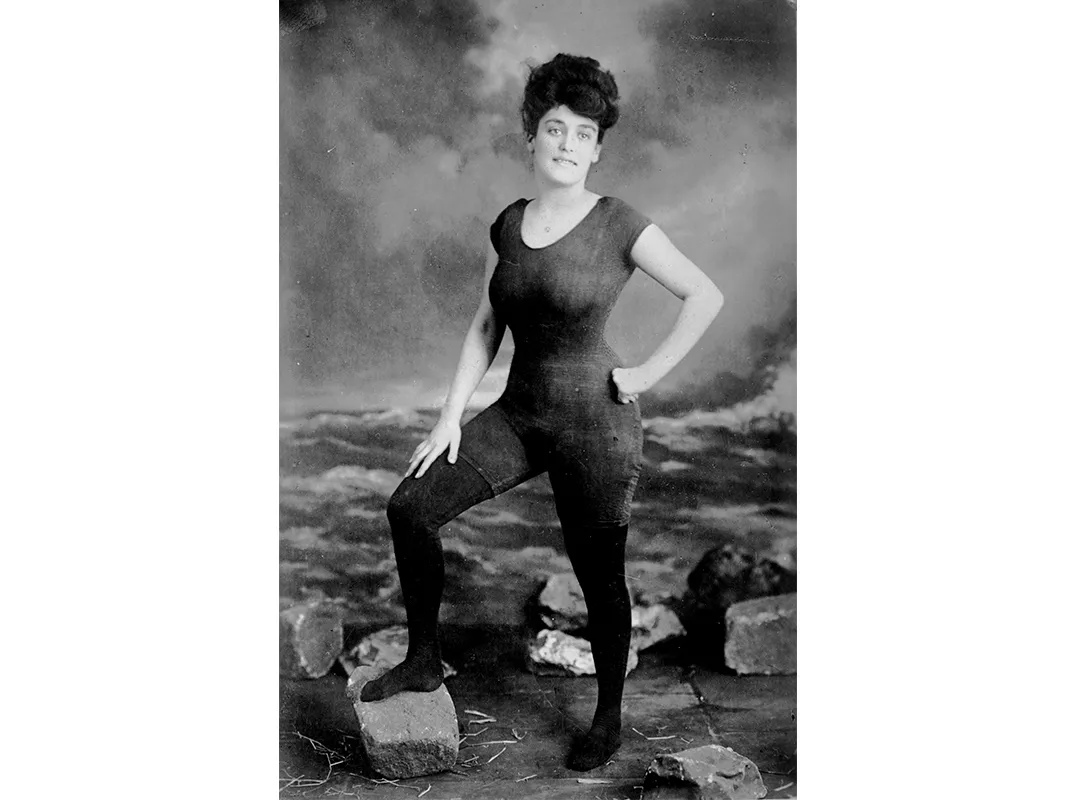

The name “synchronized swimming” dates back to the 1934 Chicago World’s Fair, where an emerging style of swimming made its mass debut. In the 1920s and ’30s, swim clubs across the United States were experimenting with floating patterns and swimming “stunts”—movements that prioritized form and group work over individual speed. Katharine Curtis, a physical-education instructor at the University of Chicago, added music from a poolside gramophone as a way to synchronize swimmers with a beat and with one another; she called her innovation “rhythmic swimming.” When the World’s Fair came to town, Curtis was asked to organize a show. She gathered 60 female swimmers and, under the name “Modern Mermaids,” they performed three times a day all summer, accompanied by a 12-piece band. When the radio announcer Norman Ross described the spectacle as “synchronized swimming,” the name stuck. Curtis saw competitive potential for this new swimming style and, in 1939, oversaw the first meet between teams. Within two years, synchro gained full acceptance by the Amateur Athletic Union, officially cementing it as a competitive sport.

Read: Watching Olympic skateboarding among 20 skeptical, aging skateboarders

While Curtis and others were moving aquatic performance in a more athletic direction, the American impresario Billy Rose saw an opportunity to link the chorus-girl aesthetic popularized by the Ziegfeld Follies with the rising interest in water-based entertainment. In 1937, he introduced his famous “aquacades,” variety shows featuring—according to one souvenir program—“the glamour of diving and swimming mermaids in water ballets of breath-taking beauty and rhythm.” The swimming champion Esther Williams was the face of Rose’s San Francisco production; she went on to launch her Hollywood career, becoming an international sensation in the ’40s and ’50s by starring in MGM’s aqua-musicals , swimming-themed films with elaborately choreographed water ballets.

By mid-century, synchronized swimming was a growing international sport with Olympic ambitions. Technologies such as underwater speakers and nose clips enabled swimmers to spend more time in difficult upside-down sequences (called “hybrids”) rather than in the geometric floating patterns associated with Williams’s films. Leaders within the sport took steps to distance it from its water-ballet cousin, discouraging theatrical costumes and props and making scoring more technical and less subjective. They organized Olympic exhibitions, starting at the 1952 Helsinki Games, to raise awareness of the sport.

Olympic induction seemed to be just around the corner. But longtime IOC President Avery Brundage wanted nothing to do with synchro, repeatedly dismissing it as “aquatic vaudeville.” Not until after his retirement did synchronized swimming join the Olympic program, making its debut at the 1984 Summer Games in Los Angeles.

Today, artistic (née synchronized) swimming has evolved nearly beyond recognition from its early years. Routines and movements are faster, lifts and throws have become ever more acrobatic and daring, and athletes spend many more hours per day in training. At the same time, scoring continues to evolve. Virginia Jasontek, the honorary secretary to the FINA Technical Artistic (formerly “Synchronized”) Swimming Committee, told me that a new deduction-based system is in the works alongside changes to make scoring difficulty and synchronization more technical.

Ironically, despite synchro’s efforts to move away from its show-biz origins, the IOC wants to highlight its entertainment value. “Today, sport should be a show,” Marculescu told me when I asked why the IOC pushed for the name change. “If sport today doesn’t provide this interest for television, if they don’t create a show, they lose ... viewers around the world.” He pointed out that synchro already has this audience appeal through its use of music and underwater footage. In exchange for changing the name, Marculescu added, the IOC said it would “keep it in the [Olympic] program and not reduce the number of swimmers”—an ever-looming threat, as cuts have to be made somewhere to add new events.

Photos: The 2019 artistic-swimming world championship

When Marculescu tasked the FINA Technical Synchronized Swimming Committee with proposing an alternative name to be voted on by the organization, the committee pushed back, according to Jasontek. “But then [Marculescu] came back to us a second time and said, ‘I really need you to come up with another name.’” Jasontek said the TSSC “fought hard” for a year and a half, but eventually decided that if the goal is to grow the sport and keep it relevant, it was better to lose the sport’s long-established brand than the good graces of FINA and the IOC. After debating a few names, the TSSC ultimately landed on artistic swimming, hoping it would align the sport with artistic gymnastics, an Olympic powerhouse, while also nodding at the sport’s artistry, which the IOC clearly valued. Not to mention that “artistic impression” is one of the three major scoring categories , along with “execution” and “difficulty,” and counts for a larger share of a routine’s total score than synchronization.

Read: The gymnast who won’t let her daughter do gymnastics

When the name change was brought for a vote at the 2017 FINA general congress, it passed quickly, says Judy McGowan, the president of USA Synchronized Swimming at the time, which she believes was by design. Normally, she told me, important issues specific to a single FINA discipline are first raised for discussion or a straw vote within that sport’s own technical congress. That way you have people who understand the sport voting on the issues that affect it, and not, for example, high divers voting on water-polo rules. But in this case, the vote was sent straight to the general congress, a body of delegates from across aquatic disciplines representing 176 countries—many of which don’t have synchronized swimming.

“I think the congress thought that if the FINA leadership thought it was a good idea, they should go along with it,” Jasontek said. One of the very few synchro delegates who was present, Lori Eaton, says the vote happened so quickly that there was no chance for deliberation and that most people around her didn’t even understand what had happened. Although general-congress meetings typically move swiftly, Eaton told me, “This one had a different feel to it. It’s like somebody said, ‘Hey, this is happening ... Let’s get the votes and be done with it.’”

For Harley-Jesson—who says neither FINA nor the IOC responded to the petition—the way the change happened comes down to “elitist men” at the IOC and FINA “old boy’s club” making unilateral decisions without consulting those with “the most skin in the game.” Her sentiments were echoed by many of those who signed the petition as well. “Once again the male dominated sports bodies want to control women’s sports,” one commenter wrote.

And yet, despite acquiescing to the IOC, the number of synchro athletes invited to the Olympics may still be cut. Although the same number of artistic swimmers—104—went to Tokyo as were in Rio, the IOC has currently allotted only 96 slots for the 2024 Olympics in Paris. Jasontek hopes the number may still be negotiable, but the disappointing reduction comes at a time when the sport is trying to expand and bring men into the Olympic fold. Mixed-gender duets were introduced at the 2015 FINA World Championships, in Kazan, Russia, and many are pushing to see the event added to the Olympics, which would open the door for men to compete at the highest level of the sport, but would also require more athlete spots.

A handful of countries have refused the new name, the most prominent being Russia—the winner of every Olympic synchronized-swimming gold medal of the 21st century. Most other countries, however, have had little choice but to conform. The U.S., which has fallen behind in the sport and missed qualifying a team for Tokyo by a fraction of a point (though the country did send a duet), was a longtime holdout. But last year, the national governing body for the sport officially changed its name to USA Artistic Swimming. Adam Andrasko, the group’s CEO, who oversaw the transition, pointed out the importance, particularly for a “judged sport,” of showing “alignment and solidarity with the international federation.” But more significant, Andrasko told me, the change presents a rebranding opportunity and the chance to show “how much more powerful and athletic” it has become.

Other athletes are also trying to be optimistic. Bill May of the U.S., who won the first mixed-duet technical world championship with his partner, Christina Jones, hopes that the shift in focus toward the artistry of the sport could also pave the way for new events vying for spots in the Olympic program. He gives the examples of the highlight routine, made up nearly entirely of the acrobatic throws and kaleidoscopic formations audiences love, and the mixed duet, unique for its dramatic interplay between the swimmers—both of which are about much more than people synchronizing in the water. “I think the name change is really going to help drive these new events and further the evolution of the sport,” May says.

For the athletes competing in Tokyo, artistic swimming is still, at its core, the same sport for which they have trained so hard—regardless of how it appears in the program. “I liked the old name, but the changes have already been adopted and it is unlikely that anything will change,” wrote the Russian Olympic gold medalist Alla Shishkina, who is competing in her third Olympiad. “Now it is not so important for me what my sport is called, the main thing is its essence. Grace, beauty, synchronicity, complexity, strength—this is what I have loved for many years.”

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center