An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

What does originality in research mean? A student's perspective

Affiliation.

- 1 University of South Wales Cardiff, UK.

- PMID: 25059081

- DOI: 10.7748/nr.21.6.8.e1254

Aim: To provide a student's perspective of what it means to be original when undertaking a PhD.

Background: A review of the literature related to the concept of originality in doctoral research highlights the subjective nature of the concept in academia. Although there is much literature that explores the issues concerning examiners' views of originality, there is little on students' perspectives.

Review methods: A snowballing technique was used, where a recent article was read, and the references cited were then explored. Given the time constraints, the author recognises that the literature review was not as extensive as a systematic literature review.

Discussion: It is important for students to be clear about what is required to achieve a PhD. However, the vagaries associated with the formal assessment of the doctoral thesis and subsequent performance at viva can cause considerable uncertainty and anxiety for students.

Conclusion: Originality in the PhD is a subjective concept and is not the only consideration for examiners. Of comparable importance is the assessment of the student's ability to demonstrate independence of thought and increasing maturity so they can become independent researchers.

Implications for research/practice: This article expresses a different perspective on what is meant when undertaking a PhD in terms of originality in the doctoral thesis. It is intended to help guide and reassure current and potential PhD students.

Keywords: PhD; Student perspectives; doctoral research; originality.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- An integrative review of threshold concepts in doctoral education: Implications for PhD nursing programs. Tyndall DE, Firnhaber GC, Kistler KB. Tyndall DE, et al. Nurse Educ Today. 2021 Apr;99:104786. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104786. Epub 2021 Jan 23. Nurse Educ Today. 2021. PMID: 33549957 Review.

- Originality and the PhD: what is it and how can it be demonstrated? Gill P, Dolan G. Gill P, et al. Nurse Res. 2015 Jul;22(6):11-5. doi: 10.7748/nr.22.6.11.e1335. Nurse Res. 2015. PMID: 26168808

- A student's perspective of managing data collection in a complex qualitative study. Dowse EM, van der Riet P, Keatinge DR. Dowse EM, et al. Nurse Res. 2014 Nov;22(2):34-9. doi: 10.7748/nr.22.2.34.e1302. Nurse Res. 2014. PMID: 25423940

- Ethics and originality in doctoral research in the UK. Snowden A. Snowden A. Nurse Res. 2014 Jul;21(6):12-5. doi: 10.7748/nr.21.6.12.e1244. Nurse Res. 2014. PMID: 25059082

- The student-supervisor relationship in the phD/Doctoral process. Gill P, Burnard P. Gill P, et al. Br J Nurs. 2008 May 22-Jun 11;17(10):668-71. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2008.17.10.29484. Br J Nurs. 2008. PMID: 18563010 Review.

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Measuring originality in science

- Open access

- Published: 11 November 2019

- Volume 122 , pages 409–427, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Sotaro Shibayama ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6701-9828 1 &

- Jian Wang 2

18k Accesses

38 Citations

28 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Originality has self-evident importance for science, but objectively measuring originality poses a formidable challenge. We conceptualise originality as the degree to which a scientific discovery provides subsequent studies with unique knowledge that is not available from previous studies. Accordingly, we operationalise a new measure of originality for individual scientific papers building on the network betweenness centrality concept. Specifically, we measure the originality of a paper based on the directed citation network between its references and the subsequent papers citing it. We demonstrate the validity of this measure using survey information. In particular, we find that the proposed measure is positively correlated with the self-assessed theoretical originality but not with the methodological originality. We also find that originality can be reliably measured with only a small number of subsequent citing papers, which lowers computational cost and contributes to practical utility. The measure also predicts future citations, further confirming its validity. We further characterise the measure to guide its future use.

Similar content being viewed by others

How to design bibliometric research: an overview and a framework proposal

Literature reviews as independent studies: guidelines for academic practice

How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As science progresses through discoveries of new knowledge, originality constitutes one of the core values in science (Gaston 1973 ; Hagstrom 1974 ; Merton 1973 ; Storer 1966 ). As such, originality is highly regarded in the recognition system of science and is relevant for critical science decisions such as funding allocation, hiring, tenure evaluation, and scientific awards (Dasgupta and David 1994 ; Merton 1973 ; Stephan 1996 ; Storer 1966 ). Despite its importance, originality of scientific discoveries is hard to measure. In practice, originality is often evaluated by means of peer reviews (Chubin and Hackett 1990 ), which is feasible only in a small scale, whereas assessing originality in a large scale poses a formidable challenge. Though bibliometric studies have recently made a considerable advancement in measuring various aspects of scientific discoveries (Boudreau et al. 2016 ; Foster et al. 2015 ; Lee et al. 2015 ; Trapido 2015 ; Uzzi et al. 2013 ; Wang et al. 2017 ), originality per se has rarely been measured. This study proposes a new measure of originality building on the network betweenness centrality concept (Borgatti and Everett 2006 ; Freeman 1979 ) and measures the originality of a scientific paper based on the directed citation network between its references and subsequent papers citing the focal paper. To validate the proposed originality measure, we conducted a questionnaire survey and demonstrate that the proposed measure is significantly correlated with the self-assessed theoretical originality but not with the methodological originality. The result also shows that the measure can predict the number of citations that the focal paper receives in the future, which further confirms the validity of the measure. We also find that the originality can be reliably measured with only a small number of subsequent citing papers. This substantially lowers computational cost compared to previous related bibliometric measures and facilitates practical use of the measure.

Literature review

Though originality is one of the core values in science, there is not yet a clear consensus on what it exactly means (Dirk 1999 ; Guetzkow et al. 2004 ). In a broad sense, originality could mean anything new (e.g., new method, new theory, and new observation) that adds to the common stock of scientific knowledge. To differentiate the degree of newness, the sociology of science literature has argued that scientific discoveries can either conform to the tradition or depart from it, and only the latter is considered to be original (Bourdieu 1975 ; Kuhn 1970 ). Following this stream of thoughts, we define originality as the degree to which a scientific discovery provides subsequent studies with unique knowledge that is not available from previous studies. As further explained, this definition is in line with the network betweenness centrality concept and allows a straightforward operationalisation.

Existing measures of originality

Despite the theoretical interest in and practical relevance of originality, how to measure originality is under-developed. In small scales, a few studies explored the aspects in which research must be new in order to be perceived by scientists as original (Dirk 1999 ; Guetzkow et al. 2004 ). Dirk ( 1999 ) conducted a questionnaire survey to evaluate three dimensions (hypotheses, methods, and results) of newness, finding that life scientists consider research with unreported hypotheses as original rather than research with new methods. Through in-depth interviews of social scientists, Guetzkow et al. ( 2004 ) also identified various dimensions of newness associated with perceived originality: approach, theory, method, data, and findings. They also found that relevant dimensions of originality can differ across scientific fields.

Bibliometric techniques for science decisions have been rapidly developing thanks to the advanced computing power and enriched bibliometric data (Hicks et al. 2015 ). A few approaches to measure the newness (originality, novelty, creativity, etc.) of a study are worth noting, although they are not necessarily labelled as “originality.” The first approach considers originality as a quality established only through reuse of a study by subsequent studies or the collective evaluation by peer scientists, but not as an intrinsic quality of a study (Merton 1973 ). For example, Wang ( 2016 ), following the definition of creativity (Amabile 1983 ), argues that forward citation counts can be viewed as peer recognition of novelty and usefulness, and therefore is a proxy for creativity.

The second approach is more recently developed and views originality as an inherent quality of a scientific paper that can be measured at the time of publication, irrespective of subsequent use of the paper. This approach has several nuanced conceptualisation strategies. One strategy focuses on the newness of a study based on the introduction of a new concept or object. For example, Azoulay et al. ( 2011 ) measured the novelty of an article based on the age of keywords assigned to the article. Within the field of biochemistry, Foster et al. ( 2015 ) also measured the novelty on the basis of new chemical entities introduced in a study. This approach is intuitively straightforward but requires a reliable and up-to-date dictionary encoding all existing concepts and objects, which is not always the case.

Another strategy is based on the assumption that integrating a broader scope of knowledge is a sign of newness. For example, the originality of a patent is operationalised as the diversity of technological domains it cites, where diversity is measured using the Herfindahl-type index of patent classes that the focal patent cite (Hall et al. 2001 ; Harrigan et al. 2017 ; Trajtenberg et al. 1997 ). A similar approach is used to measure the interdisciplinarity of scientific papers (Stirling 2007 ; Wang et al. 2015 ; Yegros–Yegros et al. 2015 ), though it conceptually features diversity rather than originality.

A third strategy, building on the combinatorial novelty perspective, views novelty as making new or unusual combinations of pre-existing knowledge components, where knowledge components can be operationalised by keywords (Boudreau et al. 2016 ), referenced articles (Trapido 2015 ), referenced journals (Uzzi et al. 2013 ; Wang et al. 2017 ), and chemical entities (Foster et al. 2015 ). An obvious limitation of this approach is that it captures only the combinatorial novelty but not other types of novelty.

Our proposed conceptualisation of originality lies between these two approaches. We consider originality to be rooted in a set of information included in a focal scientific paper. However, we argue that the value of the paper is realised through its reuse by other scientists, and that its originality is established through its interaction with other scientists and follow-on research (Latour and Woolgar 1979 ; Merton 1973 ; Whitley 1984 ). A few recently developed measures, though not conceptualised as originality, are in line with this approach. For example, Funk and Owen-Smith ( 2017 ) assess whether an invention destabilises or consolidates existing technology streams, by examining the pattern of forward citations to a focal patent and its references. This measure is adopted by Wu et al. ( 2019 ) to evaluate the disruptiveness of scientific papers. Similarly, Bu et al. ( 2019 ) measure the independent impact of papers based on the co-citation and bibliographic coupling between a focal paper and its citing papers.

Proposed measure of originality

Base measure.

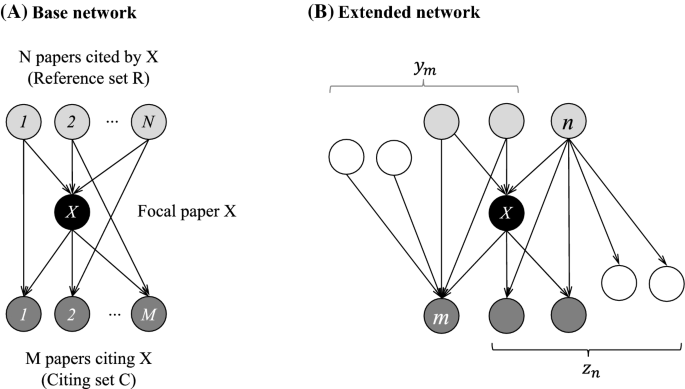

We propose to measure the originality of an individual scientific papers based on its cited papers (i.e., references) and citing papers (i.e. follow-on research). We draw on subsequent papers that cite the focal paper to evaluate whether the authors of these subsequent citing papers perceive the focal paper as an original source of knowledge (Fig. 1 A). Suppose that the focal paper X cites a set of prior papers ( reference set R ) and is cited by a set of subsequent papers ( citing set C ). If X serves as a more original source of knowledge, then the citing papers (i.e., papers in citing set C ) are less likely to rely on papers that are cited by X (i.e., papers in reference set R ). In contrast, if X is not original but an extension of R , then C will probably also cite R together with X . In other words, we exploit the evaluation by the authors of follow-on research to measure the originality of the focal paper.

Directed network of papers and citations. Note: Papers are the nodes, and citation links are the directional edges, where nodes with arrowheads cite nodes with arrow tails

This idea is operationalised as follows. Suppose that the focal paper X cites N references and is cited by M subsequent papers. For the n -th reference ( \( n \in \left\{ {1, \ldots ,N} \right\} \) ) and the m -th citing subsequent paper ( \( m \in \left\{ {1, \ldots ,M} \right\} \) ), define \( x_{nm} \) as follows:

In Fig. 1 A, for example, \( x_{11} = 1 \) and \( x_{12} = 0 \) . If a subsequent citing paper m cites few references of X , it implies that X provides original knowledge for m that is not provided by reference set R . In contrast, if the subsequent citing paper m cites many references of X , it implies that the author of m perceives the focal study X as being unoriginal. Thus, the originality score of the focal study X evaluated by the author of m is the share of papers cited both by X and by m :

This calculation is repeated for M citing papers, and the mean value is used as the originality score for X :

This measure corresponds to the proportion of 0’s in the citation matrix (i.e., missing citation links) between the cited and citing papers of X . This measure ranges from 0 to 1, and a higher value implies a higher level of originality.

To add a theoretical basis to the proposed measure, we draw on the network centrality framework (Borgatti and Everett 2006 ; Freeman 1979 ). In short, Eq. ( 3 ) is equivalent to the normalised betweenness centrality of X in the directed citation network (see Appendix 1 ). Betweenness centrality is defined as the number of the shortest paths that pass through the focal node among every pair of nodes in a connected network (Freeman 1979 ). Betweenness centrality has been used as a measure of mediation and brokerage in various networks, such as transportation flow and employee interaction in organisations (Flynn and Wiltermuth 2010 ; Gomez et al. 2013 ; Puzis et al. 2013 ). The intuition is that a directed network represents the flow of information from origins (e.g., cited papers) to destinations (e.g., citing papers), and that a node with a high level of betweenness centrality plays an important intermediary role in passing information in the network. This is consistent with the derivation of our measure. High values in the proposed originality measure indicate that the focal paper X cannot be bypassed in the flow of knowledge from old studies to recent studies; in other words, X provides original knowledge.

Prior bibliometric studies have used betweenness centrality to analyse citation networks, but most studies have treated citation networks as undirected. Because the information of citation direction is lost, the interpretation of betweenness centrality has been concerned more with connectedness than with information flow (Leydesdorff 2007 ). Previous studies have also found that papers with high betweenness centrality tend to receive more citations in the future (Shibata et al. 2007 ; Topirceanu et al. 2018 ).

Note that the proposed measure restricts the scope of network to the immediate neighbours of a focal node, whereas most previous studies draw on the whole network. Although this constraint overlooks information about remote nodes and links, using the whole network is not without limitation. Importantly, the computation with the whole network causes “double counting” because many paths between remote nodes can share the same subsets of links (Borgatti and Everett 2006 ; Brandes 2008 ). It also incurs substantial computational burden especially for large networks. A few variant betweenness centrality operationalisations have been proposed to address these issues (Borgatti and Everett 2006 ). Among others, k -betweenness centrality (or bounded-distance betweenness centrality) considers only paths with length of k or shorter, where k is a positive integer (Freeman et al. 1991 ). Two-betweenness centrality is a special case, which considers only immediate neighbours to focal nodes (Gould and Fernandez 1989 ), as our proposed measures do. Previous studies have found that k -betweenness centrality with small k ’s can reasonably predict the betweenness centrality of the whole network (Ercsey-Ravasz et al. 2012 ), while it substantially reduces the computational cost.

Weighted measure

A potential weakness of the base measure in Eq. ( 3 ) is that it can be biased by the number of references cited by papers in citing set C , as well as the number of citations received by papers in reference set R . Namely, subsequent papers with many references are more likely to cite papers in reference set R , and highly cited papers in reference set R are more likely to be cited by subsequent papers in citing set C (Fig. 1 B). To correct these potential biases, we propose Eqs. ( 4 ) and ( 5 ) as weighted measures:

where \( y_{m} \) is the reference count of the m -th paper in citing set C , \( z_{n} \) is the citation count of the n -th paper in reference set R , and L is an arbitrary positive number. Appendix 2 further explains the derivation of the weighted measures.

Use of citations for bibliometric measures

Our proposed operationalisation strategy for originality is based on citation links between scientific papers. Although citation network has been widely used for science studies and research evaluations (Garfield 1955 ; Hicks et al. 2015 ; Martin and Irvine 1983 ; Uzzi et al. 2013 ), a few potential limitations are worth noting. In particular, though one paper citing another paper is supposed to indicate an intellectual connection between them (Garfield 1955 ; Small 1978 ), citations may embody different information. For example, citing papers may be considerably influenced by citing papers but may cite them only casually; citing papers may be built on cited papers but may disprove them (Bornmann and Daniel 2008 ; De Bellis 2009 ); and citations may be generated for social and political motivations rather than for intellectual reasons (De Bellis 2009 ; Gilbert 1977 ).

One important complication pertains to field differences. For example, some disciplines (e.g., mathematics) have less citing papers or shorter reference lists (Moed et al. 1985 ); some disciplines (e.g., social sciences) tend to cite older papers than others (e.g., natural sciences) (Price 1986 ); and the citation accumulation process is slower in some fields (e.g., social sciences and mathematics) than others (e.g., medical and chemistry) (Glänzel and Schoepflin 1995 ). As later discussed, these differences might call for adjustment in the scope of the citing set and the weighting, even though the generic framework applies to all fields.

For assessing the criterion validity of our originality measure for individual papers, we conducted a questionnaire survey of the authors of these papers to enquire into self-assessed originality. We selected a sample of active scientists who earned their PhD degrees in the field of life sciences in 1996–2011 in Japan for the following reasons. First, we need articles published several years ago (but not too recently) to compute our originality measure based on their forward citations. Second, we focus on papers from PhD dissertation projects, which are usually the first research project that scientists engage in and could help their recollection. We also expect that the respondents’ desirability bias in evaluating originality could be mitigated since dissertation projects are usually decided by supervisors rather than respondents themselves. Finally, we focus on a single field of life sciences to rule out the heterogeneity across different scientific disciplines. Footnote 1

We randomly chose 573 scientists who meet the following conditions: (1) the information of PhD degree is publicly available through online dissertation databases, (2) the PhD dissertation projects were in the field of life sciences according to the funding information, and (3) the scientists remain in academic careers as of 2018. We mailed a survey to the scientists and collected 268 responses (response rate = 47%). As 22 respondents had no papers during the PhD period, we used remaining 246 scientists as the main sample.

Self-assessed measures of originality

The respondents of the survey were asked to evaluate their own dissertation projects in two dimensions of originality: theoretical and methodological (Dirk 1999 ). Each dimension is measured in a three-point scale—0: not original (all or most of the theories/methods had already been reported in prior literature, or the project did not aim at the originality in the dimension), (1) somewhat original (part of the theories/methods had already been reported in prior literature, and (2) original (the theories/methods had not been reported in prior literature).

Computing proposed originality measures

We selected 564 papers that the respondents published as the first or second author in the year of their graduation or 1–2 year before. We exclude papers published after graduation because they can be either from PhD dissertation or from postdoc research, which may confound our analysis. From Web of Science (WoS), we obtained the bibliometric information of the focal papers, their references, and subsequent citing papers up to 2018. We then identified all citation links between the references and citing papers.

In computing the originality measures, the scope of citing set C can be arbitrarily chosen. For example, it may include all existing citing papers to date or may be a single citing paper. Since the choice of citing sets can influence the quality of the measurement as well as the computational cost, we prepare two series of citing sets and assess their validities. The first series is based on the publication year of citing papers. The citing set C ( t ) includes citing papers published within t years after the publication of the focal paper ( t = 1, 2, …). For example, C (3) includes citing papers published in the same year as the focal paper or 1–3 years after that. Note that the size of C ( t ) can differ between focal papers when they have different forward citation counts. The second series of citing sets control for this variation. The citing set C [ s ] consists of the first s citing papers ( s = 1, 2,…). In order to control for the timing of the publication of citing papers, we include citing papers published only within three years after the focal paper. Footnote 2

The second weighted measure (Eq. 5 ) uses the forward citation count of each cited paper ( z n ) in reference set R . Here, the time-window of the forward citation can be also arbitrarily chosen. In this validation exercise, we use the one-year period after the publication of the focal paper as the citation time-window.

As above discussed, citation accumulation process differs across scientific fields. Thus, the optimal choice of the citing set (parameters t and s ) as well as the citation time-window for the forward citation to the reference set should be identified in respective fields.

Predicting future citations

We also examine whether the proposed measure can predict future citation impact for assessing the construct validity of our proposed originality measure (Babbie 2012 ). Specifically, we use a dummy variable (Top10) as the dependent variable, coded 1 if a paper is among the top 10% highly-cited as of 2018 in the same cohort of papers with the same publication year and in the same field, and 0 otherwise.

Correlation with self-assessed originality

First, we establish the criterion-related validity of the proposed originality measure (Babbie 2012 ). From randomly selected 246 scientists, we obtained the information of self-assessed originality of their past papers by a questionnaire survey. For potential multi-dimensionality of the originality concept, we measured two dimensions of originality: theoretical and methodological (see Appendix 3 for the distribution of the measures) (Dirk 1999 ). Then, we computed the proposed originality measures for 564 journal articles published by the survey respondents Footnote 3 to analyse the correlations with the survey measures.

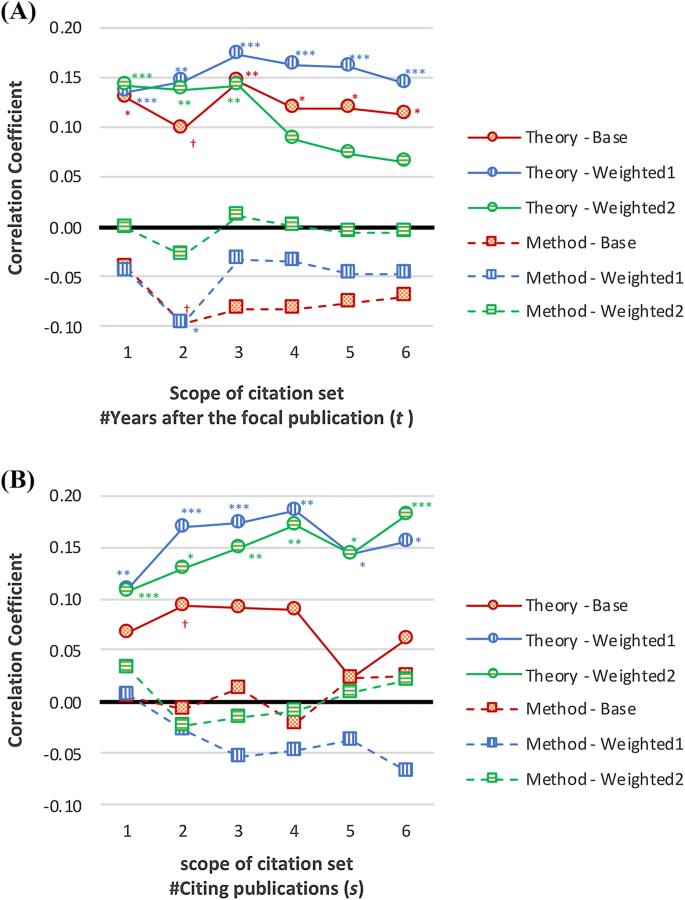

Because the scope of citing set C can influence the quality of the measurement, we assess the validity of a series of citing sets. We first calculate the originality scores using citing papers published within the first t years after the focal paper ( t = 1,…, 6). For each pair between the two survey measures (theory and method) and the three bibliometric measures (base and two weighted measures) with different citing sets, Fig. 2 A shows the correlation coefficients. We observe that our proposed originality measures have significantly positive correlations with the survey measure of theoretical originality (for example, r base = 0.130, p < 0.05; r weighted1 = 0.136, p < 0.001; r weighted2 = 0.142, p < 0.001 at t = 1) but not with the methodological originality ( p > 0.1). Provided that the previous literature found that life scientists tended to perceive theoretical newness, but not methodological newness, as relevant for originality (Dirk 1999 ), our proposed measures appear to capture the relevant dimension of originality. As to the size of the citing sets, the result indicates that the correlation with self-assessed theoretical originality is significant by using the citing papers only in the first year. A slight increase of the correlation coefficients is observed by using a larger citing sets ( t = 3), but too large citing sets do not improve the correlation. This result suggests using citing papers only in the first or a few years for assessing originality, especially considering the computational cost for large citing sets. Comparing the base and weighted measures, the three originality measures indicate similar levels of positive correlation at t = 1. While the base measure shows rather stable correlations over time, weighted measure 1 has an increase in the first few years and weighted measure 2 has a decrease after the third year. Figure 3 a illustrates the joint distribution of the self-assessed measure and the originality measures based on the first-year citing papers.

Correlation between the proposed originality measures and self-assessed originality. Note: † p < 0.1; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. A The sample size ranges from 461 to 547. B The sample size ranges from 354 to 540. Since our respondents can have multiple papers during their PhD study, we introduced a weight (the reciprocal of the paper count) into the computation of correlation coefficients. See Online Supplement for the correlation analyses

Joint distribution of self-assessed originality and proposed originality measures

Next, we alternatively focus on the first s citing papers to calculate our originality measures ( s = 1, …, 6). Figure 2 b confirms significant correlations with theoretical originality (for example, r base = 0.093, p < 0.1; r weighted1 = 0.169, p < 0.001; r weighted2 = 0.130, p < 0.05 at s = 2) but not with methodological originality ( p > 0.1), though the correlation with the base measure becomes mostly insignificant. The result also suggests that only the first few citing papers contribute to the positive correlation with theoretical originality and that including more citing papers does not improve the correlation. Figure 3 b shows the joint distribution of the self-assessed measure and the originality measure.

For the respondents who have multiple papers during their PhD study, we also took the mean of the originality measures for each respondent, and analysed the correlation at the scientist level instead of the paper level. This approach tends to present higher correlation coefficients (See Online Supplement), probably because taking the mean mitigates potential volatility of the originality measures at the paper level.

These results imply that the originality measures can be calculated with a small number of citing papers published shortly after the focal paper. That is, reliable measurement is feasible without needing to wait for a long time and with limited computational cost, lending practical utility to the proposed measures.

Prediction of future citation

We next test whether the proposed measures can predict the citation impact in the future. We compute the originality measures based on the first-year citing papers as the independent variable and predict whether the focal paper becomes among the top 10% highly-cited using citation count up to 2018. The regression model is specified as

As the dependent variable is binary, we use a logit regression model, and f is the logistic function. As a scientist can have multiple papers in the sample, we control for random errors at the scientist level ( μ ). Finally, we control for the log number of references ( N ) and citations in the first year ( M ). The model prediction is based on the maximum likelihood estimation. Here we focus on focal papers before 2008 so that the time window for accumulating citations is at least 10 years.

Table 1 A presents the result of the analyses, finding significantly positive coefficients: b base = 9.316, p < 0.01 (Model 1); b weighted1 = 13.167, p < 0.1 (Model 2); b weighted2 = 35.700, p < 0.05 (Model 3). Figure 4 a graphically illustrates the result, suggesting that papers with higher originality scores are significantly more likely to be highly cited in the future. Noticeably, the citation count in the first year ( M ) significantly correlates with both the dependent variable and the originality measures, which can confound the analysis. Thus, we test the predicting power of the originality measures with a fixed number of citing papers, by using the sub-sample of papers that have at least s citations in the first three year ( s = 2, 3, and 4). Table 1 B summarises the results, suggesting that the originality measures computed only with a few citing papers can reasonably predict future citations. Figure 4 b graphically presents the result, suggesting that focal papers with higher originality scores are significantly more likely to be highly cited. Because we expect a positive association between originality and future citations, this finding demonstrates the construct validity of our originality measure (Babbie 2012 ).

Prediction of citation rank. Note: The probability of a focal paper falling within top 10 percentile is predicted on the basis of regression models (Table 1 ). To facilitate interpretation, the horizontal axis takes the percentile of the originality measures. Error bars indicate one standard error

Characterisation of originality measures

We further investigate the behaviour of the proposed originality measures. Specifically, we examine the following ideas. First, since the above analyses suggest that citing papers in later time horizon have little added value for measuring originality, we test to what extent remote citing papers are relevant for measuring originality. Second, the proposed measures are positively correlated with the citation count and the reference count of the focal article, so we aim to confirm that the proposed measures do capture the originality of focal papers even after these confounding factors are controlled. Third, since any bibliometric indicator can be biased by contextual factors, we test particularly whether the publication year and the subfields of focal papers influence the measures.

To these ends, we compute a series of originality measures (Orig) based on citing papers in t -th year following the publication year of the focal paper ( t = 1, …, 10). Here, the citing set includes papers in the specific one year (but not up to that year). We regress this series of originality scores on the self-assessed originality measure, as well as other confounding factors (Table 2 ). The regression model is specified as

where \( \varvec{D}^{T} \) is a row vector of time dummies with the t -th entry \( d_{t} = 1 \) and other entries = 0; OrigTheory is the self-assessed originality measure; N is the number of references; M is the number of citing papers in the citing set; \( \varvec{Field}^{T} \) is a row vector of field dummies; \( \varvec{PubYear}^{T} \) is a row vector of publication-year dummies; \( \mu \) is the random error at the scientist level; and \( \nu \) is the random error at the paper level. The model prediction is based on the maximum likelihood estimation.

First, the result finds that the time dummies ( d 1 , …, d 10 ) have significantly positive coefficients ( p < 0.001) and their magnitude increases over time. This implies that the proposed originality measure increases over time when we include citing papers that is timewise more distant from the focal paper. This is probably because citing papers generally deviate from the focal study over time, and this implies that using long time windows for assessing originality could cause errors rather than to add information.

Second, the models include the interaction terms between the time dummies and the self-assessed originality measure ( OrigTheory ) to evaluate the temporal dynamics in the correlation between the self-assessed originality and the proposed originality measures. Each interaction term is concerned with to what extent the citing papers in the particular year capture the originality of the focal paper. Consistent with the above analyses, the result shows that the coefficients of the interaction terms are significant only in the first few years (base: t = 1 (Model 1), weighted 1: t = 1, 3, 5 (Model 2), weighted 2: t = 1 (Model 3)). This suggests that citing papers in later time horizon do not provide additional information about originality.

Third, as expected, both citation count ( M ) and the number of references ( N ) are positively correlated with the originality measures. Even after controlling for them, the proposed measures are significantly positively correlated with the self-assessed originality measure. Thus, the proposed measures seem to capture the true originality.

Fourth, the models include series of dummy variables for publication years ( PubYear ) and scientific subfields, and the result finds their negligible effects on the proposed measures except for the base measure (Model 1). Thus, at least within the scope of our sample, the contextual difference of the proposed measures seems limited.

The results highlight several features of the proposed measure. First, it presents a significant correlation with scientists’ self-assessment of originality. In particular, the proposed measure is correlated with theoretical newness (but not with methodological newness), which has previously been found as the main source of originality in life sciences (Dirk 1999 ). Because of multi-dimensionality of originality (Guetzkow et al. 2004 ), it is crucial to understand what aspect of originality is captured by any bibliometric indicator. Second, the operationalisation of our proposed measure is consistent with the betweenness centrality in a directed network (Borgatti and Everett 2006 ; Freeman 1979 ). Betweenness centrality has already been actively used in bibliometric studies, but prior studies have rarely analysed directed citation network to identify the flow of knowledge. Third, our measure builds not only on references but also on forward citations and therefore can be manipulated to a lesser extent by authors. Because of this advantage, our measure provides a robust tool for studying science as well as for research evaluation and science decision-making. Fourth, our proposed measure requires a smaller computational cost, especially when compared with the previous novelty measures that require information about the whole universe of papers. Our results suggest that the proposed measure can be computed with limited scope of citation network and without needing to wait for a long time after publication. This adds to the practical utility of our proposed measure. Fifth, our proposed measure helps predict future citation impact. Original discoveries are supposed to be the source of scientific progress, and the result shows that papers with a higher level of originality are also more likely to be highly cited in the long run. This adds to the validity of the proposed measure. Sixth, this study characterises the detailed behaviour of the measure, including its temporal dynamics and contextual contingencies. The result offers guidance for using the measures in future research.

Our approach has a few limitations and further research is needed. First, although we assume that citation links embody the flow of knowledge, citations can be made for various reasons (Bornmann and Daniel 2008 ; Martin and Irvine 1983 ; Wang 2014 ), which challenges the validity of our measure. Second, the proposed measure can be computed only if a citation is made. In addition certain types of original discoveries may be recognised only long after their publication (e.g., sleeping beauties) (Van Raan 2004 ), which cannot be captured by our measure based on short-time citations. Third, there are important differences between disciplines in citation behaviour, but our validation is limited to the field of life sciences. The field is known to have the fastest citation accumulation process compared with other disciplines (Wang 2013 ), which allows us to compute the originality measure in a short time window, but other fields might need longer citation time windows. Future research should identify the optional citing sets for different fields. Fourth, as self-reported originality measures can be biased, the proposed measure could be further validated by alternative approaches such as the use of scientific awards (e.g., Nobel prize) and a text analysis to detect languages associated with originality.

In conclusion, this study proposes a new bibliometric measure of originality. Although originality is a core value in science (Dasgupta and David 1994 ; Merton 1973 ; Stephan 1996 ; Storer 1966 ), measuring originality in a large scale has been a formidable challenge. Our proposed measure builds on the network betweenness centrality concept (Borgatti and Everett 2006 ; Freeman 1979 ) and demonstrates several favourable features as discussed above. We expect that the proposed measure offers an effective tool not only for scholarly research on science but also for practices in research evaluation and various science decision-makings.

Note that our validity exercise is made only in the field of life sciences. Since the citation cycle can differ between fields, future research should assess the validity of our measure in other disciplines.

This time-window is chosen because our evaluation of C ( t ) suggests that citations only in the first few years are informative (see the next section). The measure is not calculated if a focal paper received fewer than s citing papers within 3 years.

See Online Supplement for the distribution of the measures.

Amabile, T. M. (1983). The social psychnology of creativity: A componential conceptualization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 357–376.

Google Scholar

Azoulay, P., Zivin, J. S. G., & Manso, G. (2011). Incentives and creativity: Evidence from the academic life sciences. Rand Journal of Economics, 42, 527–554.

Babbie, E. R. (2012). The practice of social research . Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing.

Barabasi, A. L., & Albert, R. (1999). Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science, 286, 509–512.

MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar

Borgatti, S. P., & Everett, M. G. (2006). A graph-theoretic perspective on centrality. Social Networks, 28, 466–484.

Bornmann, L., & Daniel, H. D. (2008). What do citation counts measure? A review of studies on citing behavior. Journal of Documentation, 64, 45–80.

Boudreau, K. J., Guinan, E. C., Lakhani, K. R., & Riedl, C. (2016). Looking across and looking beyond the knowledge frontier: Intellectual distance, novelty, and resource allocation in science. Management Science, 62, 2765–2783.

Bourdieu, P. (1975). The specificity of the scientific field and the social conditions for the progress of reason. Social Science Information, 14, 19–47.

Brandes, U. (2008). On variants of shortest-path betweenness centrality and their generic computation. Social Networks, 30, 136–145.

Bu, Y., Waltman, L., Huang, Y. 2019. A multidimensional perspective on the citation impact of scientific publications. arXiv preprint arXiv:1901.09663 .

Chubin, D. E., & Hackett, E. J. (1990). Peerless science: Peer review and U.S. science policy . Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Dasgupta, P., & David, P. A. (1994). Toward a new economics of science. Research Policy, 23, 487–521.

De Bellis, N. (2009). Bibliometrics and citation analysis: From the science citation index to cybermetrics . Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press.

Dirk, L. (1999). A measure of originality: The elements of science. Social Studies of Science, 29, 765–776.

Ercsey-Ravasz, M., Lichtenwalter, R. N., Chawla, N. V., & Toroczkai, Z. (2012). Range-limited centrality measures in complex networks. Physical Review E, 85, 066103.

Flynn, F. J., & Wiltermuth, S. S. (2010). Who’s with me? False consensus, brokerage, and ethical decision making in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 53, 1074–1089.

Foster, J. G., Rzhetsky, A., & Evans, J. A. (2015). Tradition and innovation in scientists’ research strategies. American Sociological Review, 80, 875–908.

Freeman, L. C. (1979). Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Social Networks, 1, 215–239.

Freeman, L. C., Borgatti, S. P., & White, D. R. (1991). Centrality in values graphs—A measure of betweenness based on network flow. Social Networks, 13, 141–154.

MathSciNet Google Scholar

Funk, R. J., & Owen-Smith, J. (2017). A dynamic network measure of technological change. Management Science, 63, 791–817.

Garfield, E. (1955). Citation indexes for science—New dimension in documentation through association of ideas. Science, 122, 108–111.

Gaston, J. C. (1973). Originality and competition in science . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Gilbert, G. N. (1977). Referencing as persuasion. Social Studies of Science, 7, 113–122.

Glänzel, W., & Schoepflin, U. (1995). A bibliometric study on ageing and reception processes of scientific literature. Journal of information Science, 21, 37–53.

Gomez, D., Figueira, J. R., & Eusebio, A. (2013). Modeling centrality measures in social network analysis using bi-criteria network flow optimization problems. European Journal of Operational Research, 226, 354–365.

Gould, R. V., & Fernandez, R. M. (1989). Structures of mediation: A formal approach to brokerage in transaction networks. Sociological Methodology, 19, 89–126.

Guetzkow, J., Lamont, M., & Mallard, G. (2004). What is originality in the humanities and the social sciences? American Sociological Review, 69, 190–212.

Hagstrom, W. O. (1974). Competition in science. American Sociological Review, 39, 1–18.

Hall, B. H., Jaffe, A. B., & Trajtenberg, M. (2001). The NBER patent citation data file: Lessons, insights and methodological tools. NBER Working Paper , 8498.

Harrigan, K. R., Di Guardo, M. C., Marku, E., & Velez, B. N. (2017). Using a distance measure to operationalise patent originality. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 29, 988–1001.

Hicks, D., Wouters, P., Waltman, L., De Rijcke, S., & Rafols, I. (2015). The leiden manifesto for research metrics. Nature, 520, 429–431.

Kuhn, T. S. (1970). The structure of scientific revolutions . Chicago, MI: University of Chicago Press.

Latour, B., & Woolgar, S. (1979). Laboratory life: The social construction of scientific facts . Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

Lee, Y.-N., Walsh, J. P., & Wang, J. (2015). Creativity in scientific teams: Unpacking novelty and impact. Research Policy, 44, 684–697.

Leydesdorff, L. (2007). Betweenness centrality as an indicator of the interdisciplinarity of scientific journals. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58, 1303–1319.

Martin, B. R., & Irvine, J. (1983). Assessing basic research: Some partial indivators of scientific progress in radio astronomy. Research Policy, 12, 61–90.

Merton, R. K. (1973). Sociology of science . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Moed, H. F., Burger, W., Frankfort, J., & Van Raan, A. (1985). The application of bibliometric indicators: Important field- and time-dependent factors to be considered. Scientometrics, 8, 177–203.

Price, D. J. D. (1986). Little science, big science . New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Puzis, R., Altshuler, Y., Elovici, Y., Bekhor, S., Shiftan, Y., & Pentland, A. (2013). Augmented betweenness centrality for environmentally aware traffic monitoring in transportation networks. Journal of Intelligent Transportation Systems, 17, 91–105.

Shibata, N., Kajikawa, Y., & Matsushima, K. (2007). Topological analysis of citation networks to discover the future core articles. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58, 872–882.

Small, H. G. (1978). Cited documents as concept symbols. Social Studies of Science, 8, 327–340.

Stephan, P. E. (1996). The economics of science. Journal of Economic Literature, 34, 1199–1235.

Stirling, A. (2007). A general framework for analysing diversity in science, technology and society. Journal of the Royal Society, Interface, 4, 707–719.

Storer, N. (1966). The social system of science . New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Topirceanu, A., Udrescu, M., & Marculescu, R. (2018). Weighted betweenness preferential attachment: A new mechanism explaining social network formation and evolution. Scientific Reports, 8, 14.

Trajtenberg, M., Henderson, R., & Jaffe, A. (1997). University versus corporate patents: A window on the basicness of invention. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 5, 19–50.

Trapido, D. (2015). How novelty in knowledge earns recognition: The role of consistent identities. Research Policy, 44, 1488–1500.

Uzzi, B., Mukherjee, S., Stringer, M., & Jones, B. (2013). Atypical combinations and scientific impact. Science, 342, 468–472.

Van Raan, A. (2004). Sleeping beauties in science. Scientometrics, 59, 467–472.

Wang, J. (2013). Citation time window choice for research impact evaluation. Scientometrics, 94, 851–872.

Wang, J. (2014). Unpacking the matthew effect in citations. Journal of Informetrics, 8, 329–339.

Wang, J. (2016). Knowledge creation in collaboration networks: Effects of tie configuration. Research Policy, 45, 68–80.

Wang, J., Thijs, B., & Glänzel, W. (2015). Interdisciplinarity and impact: Distinct effects of variety, balance, and disparity. PLoS ONE, 10, e0127298.

Wang, J., Veugelers, R., & Stephan, P. E. (2017). Bias against novelty in science: A cautionary tale for users of bibliometric indicators. Research Policy, 46, 1416–1436.

White, D. R., & Borgatti, S. P. (1994). Betweenness centrality measures for directed graphs. Social Networks, 16, 335–346.

Whitley, R. (1984). The intellectual and social organization of the sciences . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wu, L., Wang, D., & Evans, J. A. (2019). Large teams develop and small teams disrupt science and technology. Nature, 566, 378–382.

Yegros-Yegros, A., Rafols, I., & D’este, P. (2015). Does interdisciplinary research lead to higher citation impact? The different effect of proximal and distal interdisciplinarity. PLoS ONE, 10, e0135095.

Download references

Acknowledgments

Open access funding provided by Lund University. This study was financially supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (16K01235).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Economics and Management, Lund University, 22363, Lund, Sweden

Sotaro Shibayama

Leiden University, 2333 CA, Leiden, The Netherlands

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sotaro Shibayama .

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 1 (PDF 295 kb)

We claim that the proposed measure in Eq. ( 3 ) is equivalent to the normalised betweenness centrality of X in the directed network, in which the focal paper X , papers in citing set C , and papers in reference set R are the nodes, and citation links between them are directional edges. The normalised betweenness centrality of node X is defined as

where \( \sigma_{nm} \left( X \right) \) is the number of paths from node n to node m that are shortest and go through node X , \( \sigma_{nm} \) is the number of paths from node n to node m that are shortest, and S is a normalisation factor: the number of all possible paths among all nodes in the network (Freeman 1979 ).

In the given network, the shortest path between n and m is either a direct citation link from m to n or an indirect citation link through X . In either case, the shortest path is unique. Thus, \( \sigma_{nm} = 1 \forall n,m \) . If m cites n (i.e., \( x_{nm} = 1 \) ), n and m are directly linked, and thus, \( \sigma_{nm} \left( X \right) = 0 \) . If m does not cite n (i.e., \( x_{nm} = 0 \) ), then n and m are linked only through X , and thus, \( \sigma_{nm} \left( X \right) = 1 \) . Thus, \( \sigma_{nm} \left( X \right) = 1 - x_{nm} \) .

In directed networks, the number of possible paths is given as \( S = (l_{I} - 1)(l_{O} - 1) \) , where \( l_{I} \) is the number of nodes with incoming links and \( l_{O} \) is the number of nodes with outgoing links (White and Borgatti 1994 ). In the given network, \( l_{I} = M + 1 \) and \( l_{O} = N + 1 \) . Therefore,

To address potential biases in the originality measure in Eq. ( 3 ), we propose weighted measures in Eqs. ( 4 ) and ( 5 ) that control for the reference count of each paper in citing set C and the citation count of each paper in reference set R .

Suppose that papers choose their references from the universe of all existing papers with different probabilities (Barabasi and Albert 1999 ). Each paper in the universe has different visibility or the likelihood of being cited, which we denote by \( f( \cdot ) \) —a non-decreasing function of the citation count of the paper. Focus on the citations between the n th reference in R and the m -th citing paper in C . Suppose that the m -th citing paper chooses one reference from the universe of papers. The probability of the n -th reference being cited is given by \( f\left( {z_{n} } \right) \) . Since the m -th citing paper has \( y_{m} \) references, the probability of the n -th reference being one of the references is given by \( 1 - \left( {1 - f\left( {z_{n} } \right)} \right)^{{y_{m} }} \cong y_{m} f\left( {z_{n} } \right) \) , where the approximation holds because \( f\left( {z_{n} } \right) \ll 1 \) . Summing this up across all combinations of references and citing papers, the expected number of citations between R and C, \( E\left( {\mathop \sum \limits_{m = 1}^{M} \mathop \sum \limits_{n = 1}^{N} x_{nm} } \right) \) , is given by \( \mathop \sum \limits_{m = 1}^{M} y_{m} \mathop \sum \limits_{n = 1}^{N} f\left( {z_{n} } \right) \) . In Eq. ( 3 ), we use \( MN \) to normalise \( \mathop \sum \limits_{m = 1}^{M} \mathop \sum \limits_{n = 1}^{N} x_{nm} \) . An alternative normalisation factor is the expected value of \( \mathop \sum \limits_{m = 1}^{M} \mathop \sum \limits_{n = 1}^{N} x_{nm} \) . Hence,

In particular, we employ two forms of \( f( \cdot ) \) . For simplicity, we first assume that \( f( \cdot ) \) is a constant function: \( f\left( {z_{n} } \right) = 1/L \) , which gives the weighted measure in Eq. ( 4 ). Here, \( L \) is an adjusting factor such that the summation of \( f( \cdot ) \) across the universe of papers equals 1, or the number of the papers in the universe. Second, following the prior literature (Barabasi and Albert 1999 ), we assume that \( f( \cdot ) \) is proportionate to the citation count of each paper: \( f\left( {z_{n} } \right) = z_{n} /L \) , where L is the total number of forward citations that exist in the paper universe. This gives the second weighted measure in Eq. ( 5 ). Though L is unknown, we assume that L is constant across our sample papers. To facilitate interpretation, we set L such that the minimum value of originality scores is zero.

Description of self-assessed originality measures. Note: A N = 236. B N = 234.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Shibayama, S., Wang, J. Measuring originality in science. Scientometrics 122 , 409–427 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-019-03263-0

Download citation

Received : 29 March 2019

Published : 11 November 2019

Issue Date : January 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-019-03263-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Scientific originality

- Network centrality

- Citation network

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Enroll & Pay

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Degree Programs

Original Research

An original research paper should present a unique argument of your own. In other words, the claim of the paper should be debatable and should be your (the researcher’s) own original idea. Typically an original research paper builds on the existing research on a topic, addresses a specific question, presents the findings according to a standard structure (described below), and suggests questions for further research and investigation. Though writers in any discipline may conduct original research, scientists and social scientists in particular are interested in controlled investigation and inquiry. Their research often consists of direct and indirect observation in the laboratory or in the field. Many scientists write papers to investigate a hypothesis (a statement to be tested).

Although the precise order of research elements may vary somewhat according to the specific task, most include the following elements:

- Table of contents

- List of illustrations

- Body of the report

- References cited

Check your assignment for guidance on which formatting style is required. The Complete Discipline Listing Guide (Purdue OWL) provides information on the most common style guide for each discipline, but be sure to check with your instructor.

The title of your work is important. It draws the reader to your text. A common practice for titles is to use a two-phrase title where the first phrase is a broad reference to the topic to catch the reader’s attention. This phrase is followed by a more direct and specific explanation of your project. For example:

“Lions, Tigers, and Bears, Oh My!: The Effects of Large Predators on Livestock Yields.”

The first phrase draws the reader in – it is creative and interesting. The second part of the title tells the reader the specific focus of the research.

In addition, data base retrieval systems often work with keywords extracted from the title or from a list the author supplies. When possible, incorporate them into the title. Select these words with consideration of how prospective readers might attempt to access your document. For more information on creating keywords, refer to this Springer research publication guide.

See the KU Writing Center Writing Guide on Abstracts for detailed information about creating an abstract.

Table of Contents

The table of contents provides the reader with the outline and location of specific aspects of your document. Listings in the table of contents typically match the headings in the paper. Normally, authors number any pages before the table of contents as well as the lists of illustrations/tables/figures using lower-case roman numerals. As such, the table of contents will use lower-case roman numbers to identify the elements of the paper prior to the body of the report, appendix, and reference page. Additionally, because authors will normally use Arabic numerals (e.g., 1, 2, 3) to number the pages of the body of the research paper (starting with the introduction), the table of contents will use Arabic numerals to identify the main sections of the body of the paper (the introduction, literature review, methods, results, discussion, conclusion, references, and appendices).

Here is an example of a table of contents:

ABSTRACT..................................................iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS...............................iv

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS...........................v

LIST OF TABLES.........................................vii

INTRODUCTION..........................................1

LITERATURE REVIEW.................................6

METHODS....................................................9

RESULTS....................................................10

DISCUSSION..............................................16

CONCLUSION............................................18

REFERENCES............................................20

APPENDIX................................................. 23

More information on creating a table of contents can be found in the Table of Contents Guide (SHSU) from the Newton Gresham Library at Sam Houston State University.

List of Illustrations

Authors typically include a list of the illustrations in the paper with longer documents. List the number (e.g., Illustration 4), title, and page number of each illustration under headings such as "List of Illustrations" or "List of Tables.”

Body of the Report

The tone of a report based on original research will be objective and formal, and the writing should be concise and direct. The structure will likely consist of these standard sections: introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion . Typically, authors identify these sections with headings and may use subheadings to identify specific themes within these sections (such as themes within the literature under the literature review section).

Introduction

Given what the field says about this topic, here is my contribution to this line of inquiry.

The introduction often consists of the rational for the project. What is the phenomenon or event that inspired you to write about this topic? What is the relevance of the topic and why is it important to study it now? Your introduction should also give some general background on the topic – but this should not be a literature review. This is the place to give your readers and necessary background information on the history, current circumstances, or other qualities of your topic generally. In other words, what information will a layperson need to know in order to get a decent understanding of the purpose and results of your paper? Finally, offer a “road map” to your reader where you explain the general order of the remainder of your paper. In the road map, do not just list the sections of the paper that will follow. You should refer to the main points of each section, including the main arguments in the literature review, a few details about your methods, several main points from your results/analysis, the most important takeaways from your discussion section, and the most significant conclusion or topic for further research.

Literature Review

This is what other researchers have published about this topic.

In the literature review, you will define and clarify the state of the topic by citing key literature that has laid the groundwork for this investigation. This review of the literature will identify relations, contradictions, gaps, and inconsistencies between previous investigations and this one, and suggest the next step in the investigation chain, which will be your hypothesis. You should write the literature review in the present tense because it is ongoing information.

Methods (Procedures)

This is how I collected and analyzed the information.

This section recounts the procedures of the study. You will write this in past tense because you have already completed the study. It must include what is necessary to replicate and validate the hypothesis. What details must the reader know in order to replicate this study? What were your purposes in this study? The challenge in this section is to understand the possible readers well enough to include what is necessary without going into detail on “common-knowledge” procedures. Be sure that you are specific enough about your research procedure that someone in your field could easily replicate your study. Finally, make sure not to report any findings in this section.

This is what I found out from my research.

This section reports the findings from your research. Because this section is about research that is completed, you should write it primarily in the past tense . The form and level of detail of the results depends on the hypothesis and goals of this report, and the needs of your audience. Authors of research papers often use visuals in the results section, but the visuals should enhance, rather than serve as a substitute, for the narrative of your results. Develop a narrative based on the thesis of the paper and the themes in your results and use visuals to communicate key findings that address your hypothesis or help to answer your research question. Include any unusual findings that will clarify the data. It is a good idea to use subheadings to group the results section into themes to help the reader understand the main points or findings of the research.

This is what the findings mean in this situation and in terms of the literature more broadly.

This section is your opportunity to explain the importance and implications of your research. What is the significance of this research in terms of the hypothesis? In terms of other studies? What are possible implications for any academic theories you utilized in the study? Are there any policy implications or suggestions that result from the study? Incorporate key studies introduced in the review of literature into your discussion along with your own data from the results section. The discussion section should put your research in conversation with previous research – now you are showing directly how your data complements or contradicts other researchers’ data and what the wider implications of your findings are for academia and society in general. What questions for future research do these findings suggest? Because it is ongoing information, you should write the discussion in the present tense . Sometimes the results and discussion are combined; if so, be certain to give fair weight to both.

These are the key findings gained from this research.

Summarize the key findings of your research effort in this brief final section. This section should not introduce new information. You can also address any limitations from your research design and suggest further areas of research or possible projects you would complete with a new and improved research design.

References/Works Cited

See KU Writing Center writing guides to learn more about different citation styles like APA, MLA, and Chicago. Make an appointment at the KU Writing Center for more help. Be sure to format the paper and references based on the citation style that your professor requires or based on the requirements of the academic journal or conference where you hope to submit the paper.

The appendix includes attachments that are pertinent to the main document but are too detailed to be included in the main text. These materials should be titled and labeled (for example Appendix A: Questionnaire). You should refer to the appendix in the text with in-text references so the reader understands additional useful information is available elsewhere in the document. Examples of documents to include in the appendix include regression tables, tables of text analysis data, and interview questions.

Updated June 2022

Originality and critical analysis

A classic postgraduate research project presents aims/hypotheses of a particular study, and then demonstrates arguments that clearly addresses these aims/hypotheses. Postgraduate research projects must demonstrate a degree of originality and analysis. This can cause anxiety as it is difficult to determine what constitutes original work. For this reason, it is best to address the concept of originality when you are choosing your research topic.

Originality in an academic context.

Originality does not mean re-inventing the wheel. New inventions or discoveries come very rarely in reality. The idea is to ensure you are not simply repeating what another researcher has done before. Producing an original piece of work simply means moving an idea forward by an incremental amount for the next generation to continue developing.

Critical analysis

At postgraduate level it is important to demonstrate an ability to critically analyse your data/evidence. You need to look beyond the raw data and ask yourself ‘what does this mean?’

So, analysis can mean:

You should be able to demonstrate critical thinking and analysis. Do not take anything you see or hear for granted, put it all into context, and ask yourself whether the whole picture makes sense. If there are things that don’t seem to fit, ask yourself why.

Your finished dissertation, thesis or presentation should be predominantly your own work. While it is important to put your work into the context of previous studies, examiners are interested in what you have done and what you are thinking, and therefore the bulk of your work should be demonstrably identifiable as your contribution to the subject.

See our webpage for further information on Critical thinking

The next section describes the strategies and models used in research.

- Cancer Nursing Practice

- Emergency Nurse

- Evidence-Based Nursing

- Learning Disability Practice

- Mental Health Practice

- Nurse Researcher

- Nursing Children and Young People

- Nursing Management

- Nursing Older People

- Nursing Standard

- Primary Health Care

- RCN Nursing Awards

- Nursing Live

- Nursing Careers and Job Fairs

- CPD webinars on-demand

- --> Advanced -->

| | | |

- Clinical articles

- Expert advice

- Career advice

- Revalidation

Student experience Previous Next

What does originality in research mean a student’s perspective, mandy edwards phd student, university of south wales cardiff, uk.

Aim To provide a student’s perspective of what it means to be original when undertaking a PhD.

Background A review of the literature related to the concept of originality in doctoral research highlights the subjective nature of the concept in academia. Although there is much literature that explores the issues concerning examiners’ views of originality, there is little on students’ perspectives.

Review methods A snowballing technique was used, where a recent article was read, and the references cited were then explored. Given the time constraints, the author recognises that the literature review was not as extensive as a systematic literature review.

Discussion It is important for students to be clear about what is required to achieve a PhD. However, the vagaries associated with the formal assessment of the doctoral thesis and subsequent performance at viva can cause considerable uncertainty and anxiety for students.

Conclusion Originality in the PhD is a subjective concept and is not the only consideration for examiners. Of comparable importance is the assessment of the student’s ability to demonstrate independence of thought and increasing maturity so they can become independent researchers.

Implications for research/practice This article expresses a different perspective on what is meant when undertaking a PhD in terms of originality in the doctoral thesis. It is intended to help guide and reassure current and potential PhD students.

Nurse Researcher . 21, 6, 8-11. doi: 10.7748/nr.21.6.8.e1254

This article has been subject to double blind peer review

None declared

Received: 10 June 2013

Accepted: 29 August 2013

Student perspectives - originality - PhD - doctoral research

User not found

Want to read more?

Already have access log in, 3-month trial offer for £5.25/month.

- Unlimited access to all 10 RCNi Journals

- RCNi Learning featuring over 175 modules to easily earn CPD time

- NMC-compliant RCNi Revalidation Portfolio to stay on track with your progress

- Personalised newsletters tailored to your interests

- A customisable dashboard with over 200 topics

Alternatively, you can purchase access to this article for the next seven days. Buy now

Are you a student? Our student subscription has content especially for you. Find out more

25 July 2014 / Vol 21 issue 6

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DIGITAL EDITION

- LATEST ISSUE

- SIGN UP FOR E-ALERT

- WRITE FOR US

- PERMISSIONS

Share article: What does originality in research mean? A student’s perspective

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience.

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

Stack Exchange Network

Stack Exchange network consists of 183 Q&A communities including Stack Overflow , the largest, most trusted online community for developers to learn, share their knowledge, and build their careers.

Q&A for work

Connect and share knowledge within a single location that is structured and easy to search.

How to review a paper for originality?

Originality with timeliness is among the most important criteria for a paper to get published.

Many a times when we are reviewing a paper, we are faced with dilemma as to how much of it is original, how much of it is based on another paper, and how much of it is just repetition in a slightly different context. Also, at times papers cater to interdisciplinary and cross-area and it may seem that the idea is original.

- What preparation does the reviewer need to have in order to review a paper justly?

- How do you judge the originality of a paper?

- publications

- peer-review

- 4 One tip which you may find useful: I have found that often, the closest existing work to the reviewed manuscript is the authors' previous work. So by reading the authors' previous work you can see whether they have made a large advancement or a small increment. – Bitwise Commented Aug 6, 2013 at 15:32

I've reviewed more than 50 papers, and my preparation to review them has varied widely. At least a few of them have drawn heavily on papers I've written. Generally, these are extending my results. Typically, I ask myself: What does this paper add? Is it something I would have thought of easily or not? If yes, why didn't I include it in my paper?

In contrast, I've also reviewed some papers that I was not well prepared for. They were in my general field, but in a subarea that I hadn't worked in. These papers took a lot more work. ( Up to 10x as long for me to review as a paper in an area where I'm very familiar.) For papers in an area that's new to me, I often have to look up (and skim) at least a few of the references from the introduction to judge whether the paper is original. Originality has at least two very different levels . The easier one to achieve is: (1) this result is new , and doesn't follow simply from anything previous. The much harder one is, (2) this technique is fundamentally new and produces interesting results. If the results are interesting, most journals are happy to publish articles of type (1). Articles of type (2) are much rarer, and can potentially open entire new fields.

- Preparation : you need to either know the subarea well or be willing to read a lot to learn about it.

- Originality : What papers does it draw on? How likely is it that a reader of those would be able to write this paper? Answering this question may require you to read a lot of background.

- Why would you agree to review papers in an area new to you? – user13107 Commented Aug 7, 2013 at 1:33

- First, let me clarify that it was usually a subarea that I had not done research in, although I had often heard a lecture on something related before. Typically I said yes because I either wanted to learn more about that area or the work of that specific author, or because I wanted to get experience refereeing for that particular journal (similar to the reasons I would opt to teach a new class in an area I didn't know that well yet). – Dan C Commented Aug 7, 2013 at 13:50

You must log in to answer this question.

Not the answer you're looking for browse other questions tagged publications peer-review ..

- Featured on Meta

- Upcoming sign-up experiments related to tags

Hot Network Questions

- At what point does working memory and IQ become a problem when trying to follow a lecture?

- Is it possible to cast a bonus action spell and then use the Ready action to activate a magic item and cast another spell off-turn with your reaction?

- Form all possible well-formed strings of 'n' nested pairs of 2 types of ASCII brackets

- Binding to an IP address on an interface that comes and goes

- Are these called ring binders in American English or files?

- Round Cake Pan with Parchment Paper

- What's this plant with saw-toothed leaves, scaly stems and white pom-pom flowers?

- how to make the beamer contents align to center

- Did the Father sin by not answering Jesus request?

- May a minor light one of the havdalah wicks

- Interface Panel not Updating correctly

- How does this over-voltage protection diode work?

- How did the contracted perfect passive work?

- How do I open the locked door in Fungal Wastes?

- Where can one find "the Puzzle benchmark" from Hennessy’s MIPS paper?

- Why does Ethiopian Airlines have flights between Tokyo and Seoul?

- Why are worldships not shaped like worlds?

- Can we use 3rd person singular for "Come Find"?

- Why does setting a variable readonly in the outer scope prevents defining a local variable with the same name?

- Tips on removing solder stuck in very small hole

- Can I add a 100amp breaker to my 200amp meter main for my detached garage?

- Could a kickback have caused my mitre saw fence to bend?

- What is the difference between NP=EXP and ETH, and what does the community believe about their truth?

- Problems with \dot and \hbar in sfmath following an update

Current students

- Staff intranet

- Find an event

Research skills for HDR students

- Overview and planning

- Theses including publications

Originality

- Structuring your thesis

- Literature reviews

- Writing up results

- Interpreting results

Originality is one of the most important criteria for a successful thesis. Your thesis should be a significant addition to the accumulated knowledge within your discipline, which implies it must offer something new.