कोविड-19 के दौरान स्वास्थ्य और कुशलता

मौजूदा गतिरोध के दरमियान, हम सब के लिए स्वस्थ जीवनशैली कायम रखना बहुत मुश्किल हो गया है। वित्तीय मामलों, बच्चों की देख-भाल, बुजुर्ग माता-पिता, नौकरी की सुरक्षा पर आए संकट आदि से जुड़ी अनिश्चितता और चिंताओं ने हमारी जीवनचर्या, जीवनशैली और मानसिक स्वास्थ्य सभी को अस्त-व्यस्त कर दिया है। भविष्य की अनिश्चितता, अनवरत चल रही न्यूज कवरेज और सोशल मीडिया पर लगातार आते संदेशों की बाढ़ से हमारी चिंता का बढ़ जाना स्वभाविक है। ऐसी स्थितियों में तनाव होना सामान्य है। तनाव से हमारे सोने और खाने-पीने की आदत बदल जाती है, इससे चिड़चिड़ापन या भावनात्मक ज्वार आता है, मानसिक संबल घट जाता है और लोग शराब या दूसरी लत में पड़ने लगते हैं। अगर आप ऐसा कुछ महसूस कर रहे हैं तो मदद हासिल करने से हिचकिचाएं नहीं।* स्वस्थ जीवनशैली अपनाए रखना और अपनी पुरानी जीवनचर्या में लौट आना भी बहुत महत्वपूर्ण है।

तनाव से निपटने और अपने मानसिक, शारीरिक व सामाजिक स्वास्थ्य को कायम रखने के कुछ नुस्खे-

*भारत – राष्ट्रीय मानसिक स्वास्थ्य और तंत्रिका विज्ञान संस्थान (निमहांस) ने स्वास्थ्य और परिवार कल्याण मंत्रालय के साथ साझेदारी में यह मानसिक-सामाजिक टोल-फ्री हेल्पलाइन नंबर 08046110007 शुरू किया है।

मानसिक स्वास्थ्य

शारीरिक स्वास्थ्य

सामाजिक स्वास्थ्य

- connect with us

- 1800-572-9877

- [email protected]

- We’re on your favourite socials!

Frequently Search

Couldn’t find the answer? Post your query here

- अन्य आर्टिकल्स

कोरोना वायरस पर निबंध (Essay on Coronavirus in Hindi) - Covid-19 महामारी पर हिंदी में निबंध

Updated On: January 09, 2024 05:14 pm IST

- कोरोना वायरस पर निबंध (Essay on Coronavirus in Hindi) 100, …

- कोरोना वायरस पर निबंध (Essay on Coronavirus in Hindi) 100 …

- कोरोना वायरस पर निबंध (Essay on Coronavirus in Hindi) 200 …

- कोरोना वायरस पर निबंध (Essay on Coronavirus in Hindi) 500 …

- कोरोना वायरस पर निबंध 10 लाइन हिंदी में (Essay on …

कोरोना वायरस पर निबंध (Essay on Coronavirus in Hindi) 100, 200 और 500 शब्दों में

कोरोना वायरस पर निबंध (essay on coronavirus in hindi) 100 शब्दों में , कोरोना वायरस पर निबंध (essay on coronavirus in hindi) 200 शब्दों में, कोरोना वायरस पर निबंध (essay on coronavirus in hindi) 500 शब्दों में, covid-19 पर निबंध - प्रस्तावना , कोरोना वायरस की उत्पत्ति, कोरोना वायरस से बचाव के उपाय.

- अपने हाथों को बार-बार धोएं। हाथ धोने से कोरोना वायरस के फैलने का जोखिम कम हो जाता है। हाथों को कम से कम 20 सेकंड तक साबुन और पानी से धोना चाहिए। यदि साबुन और पानी उपलब्ध नहीं हैं, तो अल्कोहल-आधारित हैंड सैनिटाइज़र का उपयोग किया जा सकता है।

- संक्रमित व्यक्ति से दूर रहें। कोरोना वायरस संक्रमित व्यक्ति के खांसने या छींकने से निकलने वाले महीन बूंदों के माध्यम से फैलता है। यदि आप किसी ऐसे व्यक्ति के संपर्क में हैं जो संक्रमित है, तो अपने लक्षणों पर ध्यान दें और यदि आपके कोई लक्षण दिखाई दें तो तुरंत चिकित्सा सहायता लें।

- सार्वजनिक स्थानों पर मास्क पहनें। मास्क पहनने से कोरोना वायरस के फैलने से बचाव में मदद मिल सकती है।

- अपने चेहरे को छूने से बचें। अपने चेहरे को छूने से कोरोना वायरस आपके शरीर में प्रवेश कर सकता है।

- स्वस्थ आहार खाएं, पर्याप्त नींद लें और नियमित रूप से व्यायाम करें।

- भीड़-भाड़ वाले स्थानों पर जाने से बचें।

- सार्वजनिक परिवहन का उपयोग करने से बचें।

COVID-19 पर निबंध - निष्कर्ष

कोरोना वायरस पर निबंध 10 लाइन हिंदी में (essay on coronavirus in 10 lines in hindi) .

- कोरोना वायरस उन वायरस के समूह से है जो बहुत तेजी से संक्रमित करते हैं।

- कोरोना वायरस की शुरुआत चीन के वुहान शहर से हुई जहां इसे इंसानों ने बनाया।

- भारत में कोरोना वायरस का पहला मामला जनवरी 2020 में सामने आया था।

- कोरोना वायरस खांसने और छींकने से फैलता है और खांसते और छींकते समय हमें अपना मुंह और नाक ढक लेना चाहिए।

- हमें अपनी सुरक्षा के लिए मास्क पहनना चाहिए और अपने हाथों को नियमित रूप से साफ करना चाहिए।

- हमारी सुरक्षा के लिए, सरकार ने इस वायरस के प्रसार को रोकने के लिए पूरे देश को बंद कर दिया था।

- कोरोना वायरस के कारण स्कूल को ऑनलाइन कर दिया गया था और छात्र घर से पढ़ाई करते थे।

- कोरोना वायरस के कारण लॉकडाउन में सभी लोग घर पर थे।

- इस दौरान बहुत से लोगों ने अपने परिवार के सदस्यों के साथ खूब समय बिताया।

- खुद को सुरक्षित रखने के लिए नियमित रूप से हाथ धोना और चेहरे पर मास्क पहनना बहुत जरूरी है।

Are you feeling lost and unsure about what career path to take after completing 12th standard?

Say goodbye to confusion and hello to a bright future!

क्या यह लेख सहायक था ?

सबसे पहले जाने.

लेटेस्ट अपडेट प्राप्त करें

क्या आपके कोई सवाल हैं? हमसे पूछें.

24-48 घंटों के बीच सामान्य प्रतिक्रिया

व्यक्तिगत प्रतिक्रिया प्राप्त करें

बिना किसी मूल्य के

समुदाय तक पहुंचे

समरूप आर्टिकल्स

- मदर्स डे पर निबंध (Mothers Day Essay in Hindi): मातृ दिवस पर हिंदी में निबंध

- शिक्षक दिवस पर निबंध (Teachers Day Essay in Hindi) - टीचर्स डे पर 200, 500 शब्दों में हिंदी में निबंध देखें

- दिल्ली विश्वविद्यालय (डीयू) में साउथ कैंपस कॉलेजों की लिस्ट (List of South Campus Colleges in DU): चेक करें टॉप 10 रैंकिंग

- लेक्चरर बनने के लिए करियर पथ (Career Path to Become a Lecturer): योग्यता, प्रवेश परीक्षा और पैटर्न

- KVS एडमिशन लिस्ट 2024-25 (प्रथम, द्वितीय, तृतीय) की जांच कैसे चेक करें (How to Check KVS Admission List 2024-25How to Check KVS Admission List 2024-25 (1st, 2nd, 3rd): डायरेक्ट लिंक, लेटेस्ट अपडेट, क्लास 1 उच्च कक्षा के लिए स्टेप्स

- 2024 के लिए भारत में फर्जी विश्वविद्यालयों की नई लिस्ट (Fake Universities in India): कहीं भी एडमिशन से पहले देख लें ये सूची

नवीनतम आर्टिकल्स

- 100% जॉब प्लेसमेंट वाले टॉप इंस्टिट्यूट (Top Institutes With 100% Job Placements): हाई पैकेज, टॉप रिक्रूटर यहां दखें

- हरियाणा पॉलिटेक्निक परीक्षा 2024 (Haryana Polytechnic Exam 2024): यहां चेक करें संबंधित तारीखें, परीक्षा पैटर्न और काउंसलिंग प्रोसेस

- यूपी पुलिस सिलेबस 2024 (UP Police Syllabus 2024 in Hindi) - सिपाही, हेड कांस्टेबल भर्ती पाठ्यक्रम हिंदी में देखें

- 10वीं के बाद डिप्लोमा कोर्स (Diploma Courses After 10th): मैट्रिक के बाद बेस्ट डिप्लोमा कोर्स, एडमिशन, फीस और कॉलेज की लिस्ट देखें

- पर्यावरण दिवस पर निबंध (Essay on Environment Day in Hindi) - विश्व पर्यावरण दिवस पर हिंदी में निबंध कैसे लिखें

- भारत में पुलिस रैंक (Police Ranks in India): बैज, स्टार और वेतन वाले पुलिस पद जानें

- जेएनवीएसटी रिजल्ट 2024 (JNVST Result 2024): नवोदय विद्यालय कक्षा 6वीं और 9वीं का रिजल्ट

- 10वीं के बाद सरकारी नौकरियां (Government Jobs After 10th) - जॉब लिस्ट, योग्यता, भर्ती और चयन प्रक्रिया की जांच करें

- 10वीं के बाद आईटीआई कोर्स (ITI Courses After 10th in India) - एडमिशन प्रोसेस, टॉप कॉलेज, फीस, जॉब स्कोप जानें

- यूपीएससी सीएसई मेन्स पासिंग मार्क्स 2024 (UPSC CSE Mains Passing Marks 2024)

नवीनतम समाचार

- CBSE 12th टॉपर्स 2024 लिस्ट: राज्य और स्ट्रीम-वार टॉपर के नाम, मार्क्स प्रतिशत देखें

- CBSE 12th रिजल्ट 2024 लिंक एक्टिव: आसानी से डाउनलोड करें इंटर की मार्कशीट

- MP Board 10th Toppers 2024 List Available: MPBSE 10वीं के डिस्ट्रिक्ट वाइज टॉपर्स की लिस्ट देखें

ट्रेंडिंग न्यूज़

Subscribe to CollegeDekho News

- Select Stream Engineering Management Medical Commerce and Banking Information Technology Arts and Humanities Design Hotel Management Physical Education Science Media and Mass Communication Vocational Law Others Education Paramedical Agriculture Nursing Pharmacy Dental Performing Arts

कॉलेजदेखो के विशेषज्ञ आपकी सभी शंकाओं में आपकी मदद कर सकते हैं

- Enter a Valid Name

- Enter a Valid Mobile

- Enter a Valid Email

- By proceeding ahead you expressly agree to the CollegeDekho terms of use and privacy policy

शामिल हों और विशेष शिक्षा अपडेट प्राप्त करें !

Details Saved

Your College Admissions journey has just begun !

Try our AI-powered College Finder. Feed in your preferences, let the AI match them against millions of data points & voila! you get what you are looking for, saving you hours of research & also earn rewards

For every question answered, you get a REWARD POINT that can be used as a DISCOUNT in your CAF fee. Isn’t that great?

1 Reward Point = 1 Rupee

Basis your Preference we have build your recommendation.

Vikram Patel: India’s Mental Health, Before and During COVID-19

Oct 21, 2020 | Announcements , Faculty , India , News

Around the world, the COVID-19 pandemic has hit communities hard, with many people suffering from the virus itself, facing unemployment, or unable to interact with family and friends. As time goes on, the effects of the pandemic are not limited to just our physical health, but have impacted our mental health, as well.

We spoke with Vikram Patel, the Pershing Square Professor of Global Health in the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine at Harvard Medical School, to learn more about the status of mental health in India and South Asia at large, both before and during the pandemic.

Professor Patel will take part in an upcoming seminar on November 9, “The Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health in China, India, and the United States,” alongside other panelists from Harvard University, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, and Central South University, to compare the current state of mental health across countries.

Can you tell us a little about what you are currently researching?

My main focus has been on scaling-up approaches that we have demonstrated are effective in improving access to quality mental health care — principally, the delivery of psychosocial interventions by frontline providers, such as community health workers, for the prevention and treatment of mental health problems. Much of my work is centered on translating the robust implementation science findings into real-world impact.

In general, how would you summarize the status of mental health in India? What is the prevalence of mental health issues in the region?

Even before the pandemic, we had very good data to inform our understanding of the burden of mental health problems in India, mainly from the Government of India’s National Health Survey conducted about 3 years ago with a large representative sample of over 30,000 participants from around the country.

The survey showed that about 10% of India’s adult population met clinical criteria for a mental health disorder. That would translate to anywhere from 70-100 million people at the time of the survey. The survey also showed that the most common problems were mood and anxiety disorders, and that very high proportions of persons affected had neither received nor sought any kind of care in the previous twelve months, approaching nearly 90% for the mood and anxiety disorders.

What are the challenges in addressing mental health disorders in India? Are there differences in the approach to mental healthcare across countries of South Asia?

I think there are a lot of similarities in the challenges and opportunities for addressing mental health problems in the different countries of South Asia. The countries share a similar social, historical, and cultural context. Of course, there are also some differences too, but I think the similarities are far greater. From my first-hand experience in India, the barriers to addressing mental health disorders can be categorized in two buckets. The first are supply-side barriers, notably the inadequate number of healthcare workers skilled to provide mental health care. The fact that there are more psychiatrists of Indian origin working in the US than in India itself gives us a sense of the enormous shortage of mental health practitioners. Even these few practitioners are located in urban areas and in the private sector, which negatively affects access to mental healthcare by rural and low-income communities.

There is also the demand-side barrier: communities are reluctant to access mental healthcare, which has been historically organized in a way that is heavily influenced by biomedical framing of “diagnoses, doctors, and drugs.” For the general population, such a framing is foreign to their understanding of mental health issues. Furthermore, most psychiatric beds are located in mental hospitals, built during the colonial era and associated with coercion, removal from society, and sedative medication. This history and imagery has contributed to the stigma about seeking mental healthcare.

Have you observed differences or similarities in how mental health issues impact low-, middle-, and high-income countries?

My main research into mental health focuses on African and South Asian contexts. Based on this experience and my clinical practice in four countries, I have observed that the core phenomena that characterize broad categories of mental health disorders are remarkably similar across contexts and cultures — and, besides, there are similarities in how people respond to interventions. Thus, mental health disorders are universal health experiences with similar “core” features and responses to interventions.

That said, culture and context greatly influence the way mental health disorders are experienced, understood, and responded to, and thus mental healthcare must embrace a diversity of perspectives, experiences, and providers.

How can South Asia’s governments and communities improve efforts toward addressing mental health?

We must move away from the narrow binary biomedical approach to mental health. Each and every one of us must value our own mental health, which is best understood as a dimension, as opposed to only being concerned about suffering from a mental health disorder.

The binary approach of diagnoses and disorders works well for infectious diseases, but not for mental health. If we approach our thinking about mental health across a dimension, we see that there is a range of actions each of us can engage in, from promotion and prevention to care and recovery. The need of the hour is to scale up what works.

There is robust evidence on the effective delivery of psychosocial intervention by frontline workers in community and primary care settings. For people with serious mental illnesses, like schizophrenia, healthcare workers need to think more about ways for social inclusion, and work must be done toward the elimination of coercion and involuntary treatment. And, of course, we must invest in prevention by targeting adverse environments, especially in childhood and adolescence.

You have an upcoming event in November that will delve into the impact of COVID-19 in China, the US, and India. How would you summarize the impact of COVID-19 on mental health in India?

COVID has helped bring the issue of mental health out of the shadows, which is a very welcome development. Much of this attention has been focused on mood and anxiety problems, triggered by the uncertainty and a growing sense of frustration in the face of the pandemic.

The truth is that uncertainty is affecting everyone, but its impact is disproportionate across populations. Low-income or disadvantaged communities have been much worse hit, for example, due to the potential loss of income and work. This has led to significant adverse mental health consequences, and I fear that this will lead to a steep increase in mental health problems throughout the vulnerable communities of India.

Additionally, during lockdown, many routine healthcare services shut down. People with serious mental illnesses rely on routine care. The shutdown spells disaster for people who need such continuing care. Though the impact has not yet been documented, I fear a steep increase of relapses in this vulnerable group of persons.

Have there been changes in India regarding the approach to mental health since the onset of COVID-19?

It’s been a bit of a mixed picture. On one hand, there is a lot of community action that is being led by frontline workers, civil society organizations, and NGOs — India’s greatest assets. These groups are working across the country, and they are sometimes the only source of support for marginalized communities.

On the other hand, it has been a sorry tale of disregard for the disproportionate impact of lockdown and the pandemic on rural, marginalized, and low-income populations. When the definitive history of the pandemic response around the world and in India is written, what will stand out is this disregard by the privileged, from politicians and bureaucrats to the wealthy and even some scientists, to the devastating impact of lockdown on the millions who are voiceless.

What are your top recommendations to care for one’s own mental health during the pandemic? What are your main concerns?

I think uncertainty is the main stressor that has been affecting people everywhere — including here in the US. Uncertainty is part of the human condition, and from an evolutionary perspective, humans are geared to respond to uncertainty in ways that protect ourselves. In times like these, however, when uncertainty is chronic, pervasive, unanticipated, there is no sense of when it will end, and when every day seems to bring more bad news, combined with concerns about upcoming elections, political polarization, and climate change, these uncertainties significantly affect mental health.

So, how do we mitigate the adverse effects of these uncertainties on our mental health? We can’t simply wish it away. There are certain things that can be done to help: maintain a routine and structure in your day and minimize the time reading or watching news — as the media deals with so many negatives. Be as aware of your mental health as you are of your physical health, and acknowledge distress and speak to a trusted person when you are distressed. Focus on the present; there is little to be gained by worrying about the future. Meditate, exercise, and do things that are meaningful to yourself and others around you. Right now, it’s a great time to get into community action; it’s something that is desperately needed and can build and enhance your well-being.

In the coming weeks and months, what is needed to avert a mental health crisis in South Asia or even around the world?

I’m extremely concerned about the global mental health crisis that we will face. Even before the pandemic, there was significant, robust data that showed worsening mental health, especially in young people, around the world, and in the US suicide mortality has increased 50% in last decade in this demographic.

The pandemic with its uncertainties and the economic recessions will likely cause this burden of mental health problems to worsen. Even before the pandemic, mental healthcare was not fit for purpose. We now have a historic and urgent opportunity to reimagine the future of mental healthcare. There is always the call for more investment, but that must be guided by the best science on what is cost effective in mental healthcare. We must also pay attention to a human rights perspective, which necessitates us to deliver healthcare in a way that always respects and protects a person’s dignity. ☆

———

Join us on Monday, November 9 at 8:15 PM EST to listen to Vikram Patel and others discuss the impact of COVID-19 on mental health in China, India, and the United States.

Register via zoom : https://harvard.zoom.us/webinar/register/wn_cldc-z0uqsuno0ykyonf5g.

☆ All opinions expressed by our interview subjects are their own and do not reflect the views of the Mittal Institute and its staff.

Recent Posts

- A Look Back on Mittal Institute’s Spring Flagship Events: May 2-3, 2024

- Aisha Kokan ’26 Studied Mental Health in India through LMSAI Grant

- Storykit Program Inspires Academic Excellence in Pakistan Schools

- Annual Symposium Preview: Genetics and Medicine

- Annual Symposium Preview: Understanding Climate in South Asia

Yearly Archive

- Afghanistan

- Announcements

- Arts at LMSAI

- India Seminar Series

- Arts at SAI

- Graduate Student Associates

- South Asia in the News

- Research Affiliates

- Social Enterprise

- Name * First Last

- Affiliation Please List your Professional Affiliation

- Current Harvard Student

- Harvard Alumni

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

The effect of covid-19 and related lockdown phases on young peoples' worries and emotions: novel data from india.

- 1 Department of Psychology, Magadh University, Bodh Gaya, India

- 2 Department of Psychology, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India

- 3 Department of Psychology, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King's College London, London, United Kingdom

- 4 Division of Psychology, Department of Life Sciences, and Center for Cognitive Neuroscience, College of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Brunel University, London, United Kingdom

The COVID-19 pandemic has posed unprecedented stress to young people. Despite recent speculative suggestions of poorer mental health in young people in India since the start of the pandemic, there have been no systematic efforts to measure these. Here we report on the content of worries of Indian adolescents and identify groups of young people who may be particularly vulnerable to negative emotions along with reporting on the impact of coronavirus on their lives. Three-hundred-and-ten young people from North India (51% male, 12–18 years) reported on their personal experiences of being infected by the coronavirus, the impact of the pandemic and its' restrictions across life domains, their top worries, social restrictions, and levels of negative affect and anhedonia. Findings showed that most participants had no personal experience (97.41%) or knew anyone (82.58%) with COVID-19, yet endorsed moderate-to-severe impact of COVID-19 on their academics, social life, and work. These impacts in turn associated with negative affect. Participants' top worries focused on academic attainments, social and recreational activities, and physical health. More females than males worried about academic attainment and physical health while more males worried about social and recreational activities. Thus, Indian adolescents report significant impact of the pandemic on various aspects of their life and are particularly worried about academic attainments, social and recreational activities and physical health. These findings call for a need to ensure provisions and access to digital education and medical care.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had far-reaching consequences on the physical and mental health of individuals as well as the health of economies across the globe. While young people may be less susceptible to severe forms of the illness, suffering milder symptoms, lower morbidity, and better prognosis compared to adults ( 1 , 2 ) they have experienced an upsurge in stress ( 3 , 4 ) precipitating loneliness, anxiety and depression in many ( 5 – 8 ). As emotional symptoms in adolescence can become associated with many serious mental health outcomes including suicide, long-term physical health consequences, and significant healthcare burden ( 9 – 11 ), the effect of COVID-19 on young people's mental health could be more damaging in the longer run than the infection itself ( 12 ). Measuring early signs of mental health challenges such as worries and negative emotions in young people is thus an urgent priority for researchers ( 13 , 14 ) as well as policy-makers, including identifying those most vulnerable to mental health difficulties. While this information is crucial for both high- and low-income countries, countries with lower resources dedicated to mental health may benefit more from early forecasts of these needs.

India has one of the highest COVID-19 infection rates in the world with over 2.5 million confirmed cases and the death toll on the rise ( 15 , 16 ). The first case of COVID-19 was identified on January 30, 2020 in Kerala ( 17 ) in a student who had returned from Wuhan, China ( 18 ). However, since March 2020, there has been an upsurge in the spread of the infection. In response, the Government imposed a nationwide lockdown to prevent community transmission of the infection. Despite some regional differences in the extent of lockdown restrictions, based on total COVID-19 cases in that region ( 18 ), everyone in India has experienced closure of educational and training institutions; hotels and restaurants; malls, cinemas, gyms, sports centers; and places of worship. A recent correspondence article by Patra and Patro ( 19 ) speculated that school closures in particular may have been especially damaging for young people and highlighted the urgent need to address mental health issues in Indian adolescents. Yet there have been no such systematic efforts to our knowledge. Here, we report new data from a small cohort of young people from India. We describe their experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic and the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on their daily life. We describe the content of the most common worries reported by young people alongside quantitative measures of current negative and (absence of) positive emotions—symptom-markers of common mental health difficulties such as anxiety and depression. We then assess which young people (in terms of gender, age, and socioeconomic status) are particularly susceptible to reporting more negative emotions and fewer positive emotions. In India, before the pandemic started, public awareness around mental health in young people had been increasing along with the recognition that such problems can be economically costly ( 20 ). Our data can thus signpost emerging, potentially costly mental health problems post-pandemic.

Participants and General Procedures

This study received approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University (Ref No.: Dean/2020/EC/1975) and King's College London Research Ethics Committee (Ref: HR-19/20-18250). Participants were recruited between June 5, 2020 and July 12, 2020. Prospective participants from different states of North India (Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, New Delhi, West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh, Gujrat) and their parents were identified by circulating information about the study including eligibility criteria (aged 12–18 years; currently residing in India) through social media sites, such as Facebook and WhatsApp. Interested and eligible individuals were sent bilingual (Hindi and English) information sheets (one for young people, one for the parents if the participant was aged 12–17 years). Those who agreed to participate after reading the information sheet received the survey link for both the English and Hindi versions and were requested to complete one based on their language preference. The survey link began with a question about the participants' age. If the participant was 18 years, they viewed and completed a consent form with an electronic signature and their contact details for follow-up assessments. Any participant aged 12–17 years was presented with an assent form with a parental/guardian consent form. To verify that parent/guardian consents were authentic, follow-up phone contact was made with the parent/guardian using the provided contact details. Survey questions were not presented further for incomplete consent/assent forms.

The online survey was developed using Qualtrics software (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). The first third of the survey comprised questions around demographics, personal experiences and knowledge of others who had been infected by the coronavirus, extent of social restrictions and social contact, and the impact of the viral outbreak on various life domains. The second third of the survey included measures of poor mental health such as negative affect, anhedonia (absence of positive affect), and the content of worries. The final third included measures of well-being (positive aspects of mental health), more specific negative emotional experiences (loneliness, boredom) and a cognitive measure (positive and negative future imagery) (presented elsewhere). All Hindi translations used the translation-back-translation method. MS completed the first set of translations, which were back translated by TS. JL checked the back-translations. Where there were definitional discrepancies with the original scale, these were discussed with RP and VK and re-translations were done by MS. The average time taken by the participant to complete the survey was 20 min.

Demographics

Participants submitted information on their age, sex assigned at birth, family monthly income level, and number of family members.

Personal Experiences of and Knowledge of Close Others With COVID-19

Five items (with yes/no responses) measured the extent to which participants had experienced the infection: have you ever been affected or suspected of having the coronavirus infection at any time, do you currently have a confirmed diagnosis of coronavirus infection, are you currently suspected of having a diagnosis of coronavirus infection, have you had a past confirmed diagnosis of coronavirus infection but have now recovered, have you had a past suspected diagnosis of coronavirus infection but have now recovered. Five items (with yes/no responses) assessed whether participants knew others who had experienced the infection, including: a family member, friend, other acquaintance (e.g., classmate), other individual known indirectly (e.g., acquaintance of a family member/friend/acquaintance), know no one with the illness. If the participants endorsed one of the first 4 items, they were asked whether the individual affected had recovered, were still recovering, were hospitalized or had passed away.

Social Restrictions Associated With COVID-19

To describe the extent of reduced social contact, participants indicated the total number of days spent in self-isolation (i.e., not leaving the house), days in which they spent 15 min or more outside the house, days in which they had face-to-face contact with another person for 15 min or more, days in which they had a phone or video call with another person for 15 min or more.

Impact of COVID-19

Participants rated the impact of the outbreak (including associated lockdown measures) on work, study, finances, social life (including leisure activities), relationship with family, physical health, emotions, and caring responsibilities (for children/siblings or elderly/fragile family members) over the last 2 weeks on a 5-point scale (0 = not applicable/none, 1 = very mildly, 2 = mildly, 3 = moderately, 4 = severely). Responses were summed across items to create a total impact score. In the current sample, the internal consistency reliability for the impact items was 0.706.

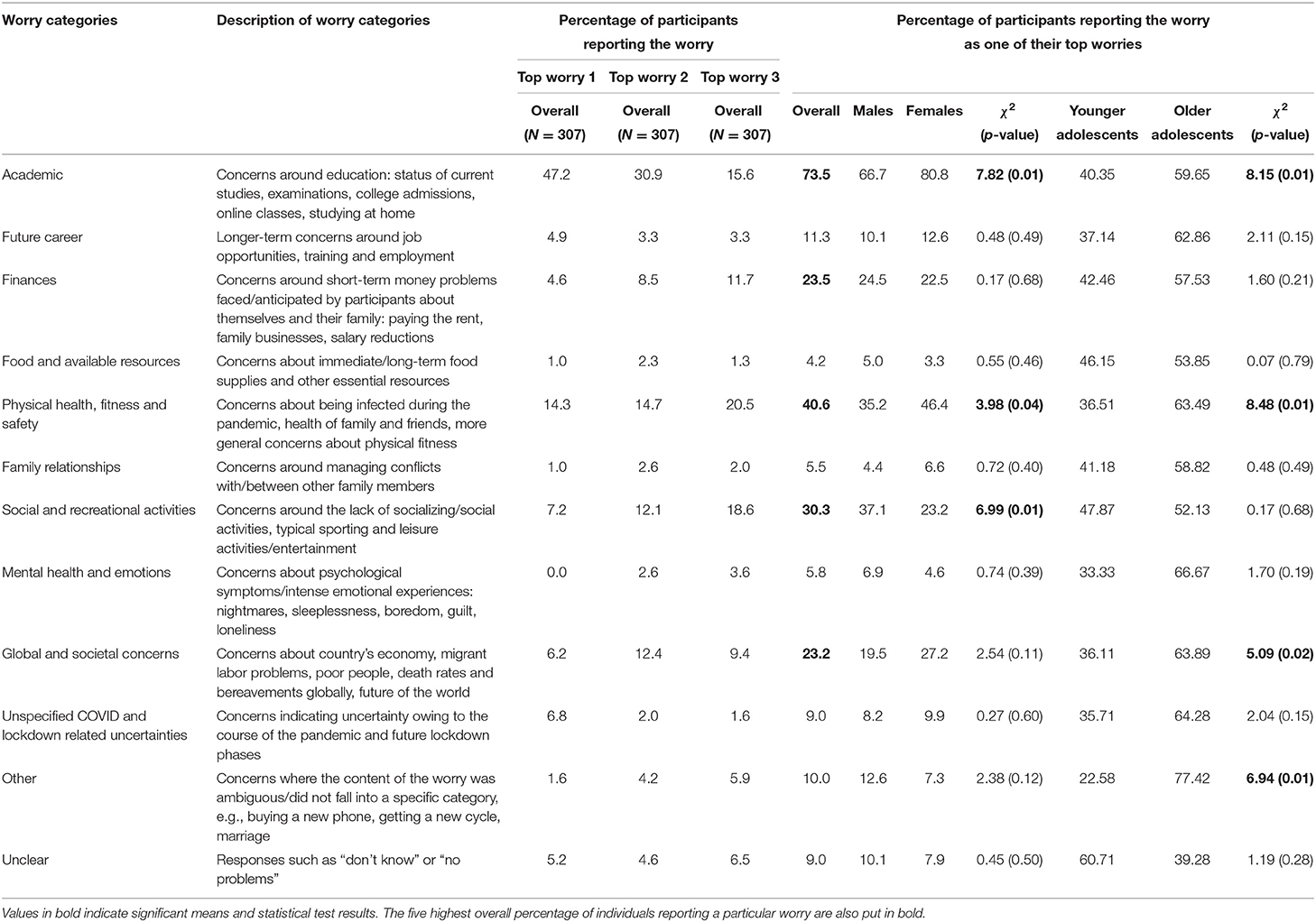

Content of Worries

Participants were asked to write down their top 3 worries using free text boxes. All free text responses were reviewed by two researchers (MS, TS), who then independently derived “worry categories” based on these responses. The categories proposed by MS and TS were then reviewed by RP, VK, and JL. Where common categories were identified by both researchers these were used in the final worry categories. Where there were differences, these were resolved through discussions, using the life domains listed in the COVID-19 impact questions to help guide the identification of conceptually distinct areas. The final 12 categories along with their descriptions are shown in Table 4 . Using this coding scheme and definitions, all responses were coded by both MS and TS independently to assess inter-rater agreement (Cohen's Kappa reliability). This was 0.98 for Worry 1, 0.90 for Worry 2, and 0.91 for Worry 3.

Negative Affect

The 10 negative affect items from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule ( 21 ) were used to assess negative emotions. Respondents used a 5- point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely) to indicate the extent to which they experienced the given mood states during the last 2 weeks. A total negative affect score, ranging from 10 to 50, was created by summing across the scores of individual items. Cronbach's alpha was 0.878.

Nine items (nos. 1, 3, 4, 5, 7, 9, 10, 13, and 14) from the 14-item Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale ( 22 ) were used to index anhedonia, the inability to experience pleasure; the remaining 7 items were deemed unlikely to apply during lockdown phases. Four response options were given for each item (strongly disagree, disagree, agree, or strongly agree), where strongly disagree and disagree were scored 1 and agree and strongly agree, scored 0. A summed score across items therefore ranged from 0 to 14, where higher scores indicated greater absence of positive affect. Cronbach's alpha was 0.723.

Statistical Analyses

After presenting the demographic characteristics of the sample, gender differences in age and income were analyzed using independent sample t -tests. Descriptives of young peoples' personal experiences of the infection, knowledge of others with the infection, the effect of lockdown on social isolation and contact with others and impact across other life domains were presented next. Before conducting any statistical analysis, the data were checked for fulfilling the assumptions for normality ( 23 ). The data did not show serious deviations from normality based on the histogram plots, except a slight positive skew for anhedonia. The skewness and kurtosis values of the data were also within the recommended limit of ±2 ( 24 , 25 ), most being < 1 (except for anhedonia which was >1). Thus, we employed parametric analyses for all the variables except for anhedonia which was explored using non-parametric tests. We investigated the degree to which the overall impact of COVID-19 across life domains varied as a function of gender (using independent samples t -test) and age and family income levels (using bivariate correlations). For the worry data, the percentage of individuals endorsing each worry category was calculated for each of the top 3 worries (first, second, third). However, in the final analysis, we collapsed across the top 3 worries to generate an overall percentage across participants of endorsing that worry among one of their top 3 worries. This meant, for instance, that any participant who rated the same worry across all 3 of their top worries was only represented once. The final percentage of young people endorsing the worry categories was compared across gender and for interpretability, by categorical age groups (Younger adolescents = 12–15 years; Older adolescents = 16–18 years) using chi-square tests. Finally, we presented data on negative affect and absence of positive affect (anhedonia); we investigated how these variables varied across gender, age, and per capita monthly income using multiple linear regression models; we further assessed whether inclusion of interaction terms significantly added to variance explained. Given a slight positive skew for anhedonia, we log-transformed this variable when conducting the regression analysis. To complement the multiple regression analysis of demographic predictors and their interactions, we also ran a series of parametric and non-parametric t -tests and correlations for negative affect and anhedonia, respectively, to assess the extent to which gender, age and family income levels individually associated with these variables. Correlations also assessed the extent to which the overall impact of COVID-19 associated with negative affect and anhedonia.

Demographic Characteristics

The final sample comprised 310 Asian-Indian adolescents (Mean age = 15.69 years; SD = 1.92) of whom 159 were males (Mean age = 15.60 years; SD = 1.98) and 151 were females (Mean age = 15.78 years; SD = 1.87). Males and females did not differ significantly in age, t (308) = −0.84, p = 0.40, d = 0.05. Furthermore, the Levene's test of equality of variances indicated an equal spread of scores in males and females ( F = 0.89, p = 0.34). Only 192 participants provided data for monthly per capita family income, which ranged from 125 to 150,000 Rupees (Mean = 9698.20; SD = 18315.22) with no significant mean or variance differences in the monthly per capita income between males and females [Male Mean = 8343.61; SD = 15065.95; Female Mean = 11439.82; SD = 21768.30; t (190) = −1.16, p = 0.25], d = 0.16, Levene's test of equality of variances: F = 2.63, p = 0.10.

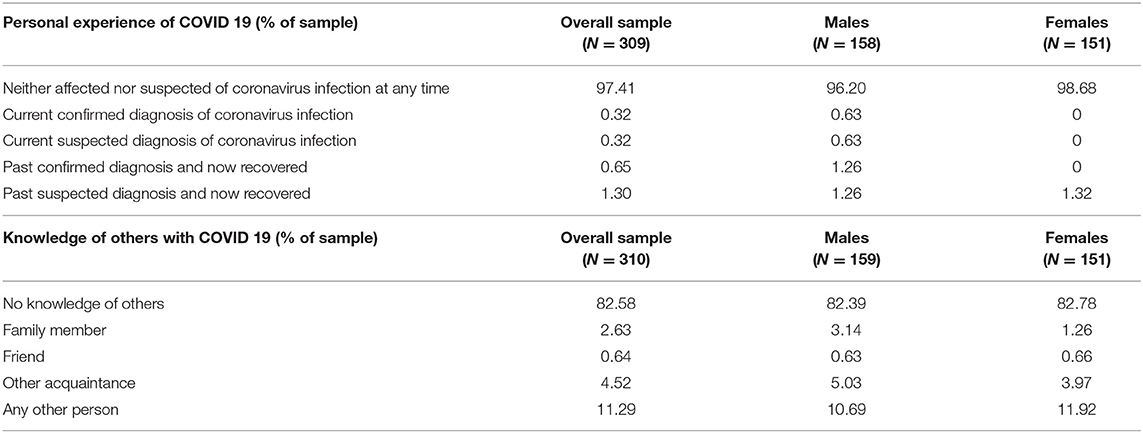

Experiences of COVID-19

Item-level data for personal experiences and knowledge of close others with COVID-19 infections are presented in Table 1 for all participants; and males and females separately. Most young people had not personally experienced or known someone with the coronavirus infection. Of those who did report knowing someone infected with COVID-19, just under half (49.09%) reported that the affected person they knew had recovered from the infection, 12.73% reported that the person was still recovering, 14.54% reported that the known person was hospitalized, while 25.45% participants reported that the affected person passed away.

Table 1 . Personal experience of and knowledge of others with COVID-19 (Of note, while the first set of questions about personal experiences of COVID-19 reflects mutually exclusive response options (therefore adding up to 100%), the set of questions around knowledge of others are not all mutually exclusive. For instance, a participant reporting a family member as well as an acquaintance infected with the virus would be included twice, once when calculating the percentage of participants reporting an infected family member and once when calculating the percentage of participants having an infected acquaintance. Therefore, participants having knowledge of others with COVID-19 do not add up to 100%).

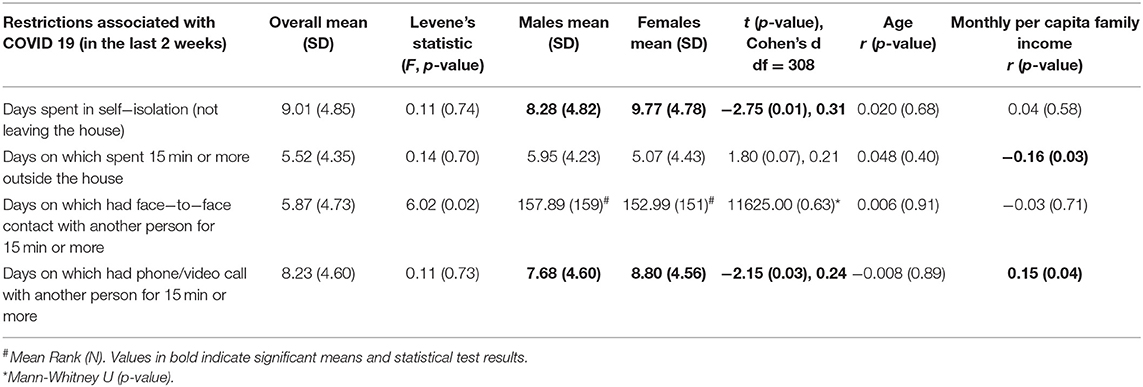

Social Restrictions and Impact of COVID-19

Item-level data for questions around social restrictions and reduced social contact are presented in Table 2 for all participants, for male and females separately; and correlations with age and monthly per capita family income. Compared to males, female participants spent significantly more days in self-isolation and more days engaging in phone or video call for 15 min or more. Participants with lower monthly per capita income spent more days in which they were out for 15 min or more, but fewer days engaging in phone or video calls. Age did not correlate with perceived social restrictions.

Table 2 . Restrictions associated with COVID−19.

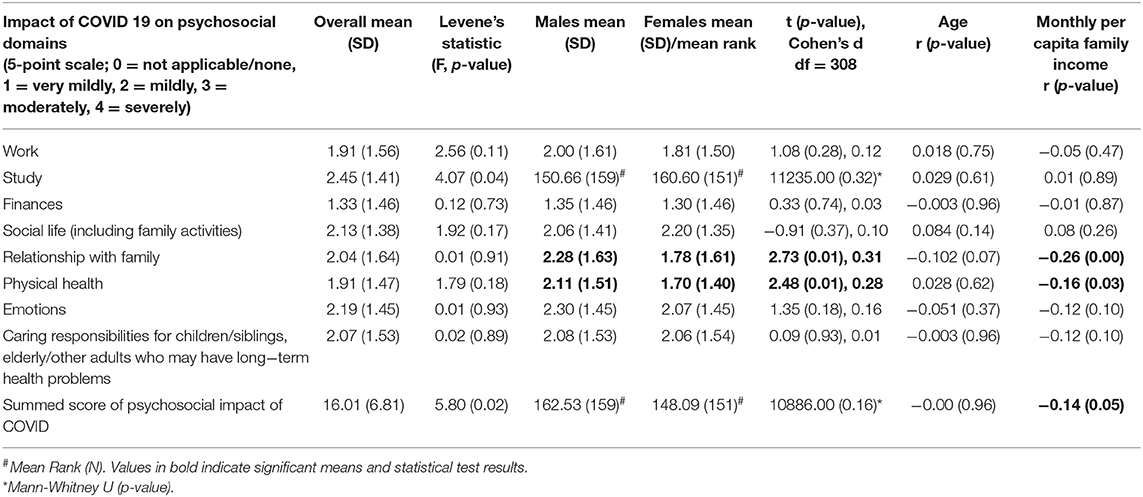

Mean ratings of the impact of COVID-19 on various life domains are presented in Table 3 . Looking at how many young people endorsed moderate-to-severe impact for each domain, 43.6% reported this on their work, 56.8% on their studies, and 48.4% on their social life and recreational activities. Just under half of young people reported moderate-to-severe impact of the pandemic on their family relationships (48.4%), on their caring responsibilities (49.4%) and on their physical health (42.6%). However, 52% reported this for their emotions. For finances, moderate-to-severe impact was reported by 26.8% of young people. Sex, age, and per capita monthly income effects were examined on each domain-specific impact score and the total score, summed across mean ratings for each domain ( Table 3 ). No significant associations emerged between age and impact across any domain ( Table 3 ). Males reported higher mean impact scores for relationships with family members and physical health. Participants with lower per capita income experienced more impact of COVID-19 across life domains (indicated by total impact score) than those with higher monthly per capita income.

Table 3 . Impact of COVID-19 on psychosocial domains.

The percentages of young people endorsing each worry category for each of their top 3 worries are presented in the first three columns of Table 4 . These were used to derive the overall percentages of young people endorsing each worry category as one of their top 3 worries presented in Column 4. Using this fourth column, we noted that most participants reported education and studies (Academic) as one of their top worries. The second most common worry of participants centered around “Physical health, fitness, and safety.” Worries about “Social and recreational activities” also emerged as a major concern for several participants, followed by “Finances.” Some participants also listed “Global and societal concerns.” More females reported concerns about “Academic,” and “Physical health, fitness, and safety,” compared to males ( Table 4 ) while male participants reported more worries around “Social and recreational activities” activities than female participants. Comparison of worries across the adolescent groups revealed that while a higher percentage of older adolescents reported each of the worries as one of their top three worries compared to younger adolescents (except for “Unclear” category), the differences were statistically significant only for “Academic,” “Physical health, fitness, and safety,” “Global and societal concerns,” and “Other” categories ( Table 4 ).

Table 4 . Participants' reported content of top three worries over the last 2 weeks.

A stepwise multiple regression was conducted with negative affect as the dependent variable and age, gender, and per capita monthly income as predictors in step 1 and their interaction terms (i.e., age x gender, age x per capita monthly income, gender x per capita monthly income, and age x gender x per capita monthly income) entered in step 2. Results indicated that the model predicted by the demographic variables was non-significant, F (3,187) = 2.11, p = 0.10 (Adjusted R 2 = 0.017). Nor did the inclusion of interaction terms significantly increase variance explained, R 2 change = 0.004, p = 0.36, F (4,186) = 1.79, p = 0.13 (Adjusted R 2 = 0.016). These findings suggested that males and females did not differ on total negative affect, t (305) = −0.90, p = 0.37, d = 0.10 [Male mean = 21.67 (SD = 8.78), Female mean = 22.51 (SD = 7.85)], Levene's test of equality of variances: F = 0.46, p = 0.50. Nor were there significant correlations with age ( r = 0.09, p = 0.10) and per capita monthly income ( r = −0.11, p = 0.13). However, significant correlations emerged between negative affect and reported impact of COVID-19 across life domains ( r = 0.26, p < 0.001). Negative affect correlated (mostly) weakly but significantly with impact of COVID-19 on social life ( r = 0.13, p = 0.02), relationship with family ( r = 0.14, p = 0.01), physical health ( r = 0.20, p < 0.001), emotions ( r = 0.23, p < 0.001), and caring responsibilities ( r = 0.18, p < 0.001), but not with work ( r = 0.11, p = 0.06), study ( r = 0.07, p = 0.22), and finances ( r = 0.11, p = 0.06).

A stepwise multiple regression, similar to that conducted for “negative affect” was conducted for anhedonia but with the log-transformed scores since the anhedonia scores were slightly positively skewed. Results showed that the model with all demographic predictors was non-significant, Model 1: F (3,156) = 1.44, p = 0.23 (Adjusted R 2 = 0.008). Inclusion of interaction terms did not significantly increase the variance explained, R 2 change = 0.000, p = 0.85, F (4,155) = 1.08, p = 0.37 (Adjusted R 2 = 0.002). Assessment of the individual demographic predictors showed that males (Mean Rank = 165.43) reported higher levels of anhedonia than females (Mean Rank = 141.09); Mann–Whitney U = 9838.50, N1 = 156, N2 = 150, p = 0.01. Participants belonging to families with higher monthly per capita income experienced lower levels of anhedonia ( r s = −0.17, p = 0.02). However, there were no significant correlations between reported impact summed across life domains and anhedonia ( r s = −0.02, p = 0.74). While anhedonia correlated positively but weakly with impact of COVID-19 on physical health ( r s = 0.13, p = 0.02), it showed a significant but weak negative relationship with impact of COVID-19 on study ( r s = −0.20, p < 0.001) and social life ( r s = −0.11, p < 0.05). Anhedonia did not correlate significantly with the impact of COVID-19 on work ( r s = 0.01, p = 0.93), finances ( r s = −0.02, p = 0.70), relationship with family ( r s = 0.09, p = 0.13), emotions ( r s = −0.04, p = 0.45), and caring responsibilities ( r s = −0.02, p = 0.73).

This paper describes baseline data for a cohort of Indian adolescents recruited to a study aiming to assess the longitudinal impact of COVID-19 on negative emotions, worries and strategies used to manage these emotions. Participants were recruited at a time when the total number of coronavirus-infected people in India stood at 236,184 and ended when the total number of infections was 879,466, showing a consistent rise during the period of (baseline) data collection ( 16 ). Yet, even during this period of rising infections, personal experiences and knowledge of others who had been exposed to the coronavirus infection were uncommon for most of our participants. Nonetheless, participants reported moderate-to-severe impact of COVID-19. The impact data together with qualitative data on their top worries, underscored academic studies as a salient area of concern for most young people in this cohort, a likely outcome of social distancing measures preventing school attendance and educational progress. Other salient worries for young people were concerns over the health and safety of self and loved ones and the absence of age-typical social and recreational activities, again expected worries emerging due to the pandemic itself and associated lockdown measures. Interestingly, young people commonly reported worries for their own finances as well as the Indian and global economy, and society more generally. Significantly higher percentage of older adolescents (16–18 years) than younger ones (12–15 years) were worried about their academics, physical health and safety, global and societal concerns and other kinds of worries, which can be expected since with increasing age, the academic work and curriculum gets more difficult and late adolescence is also the crucial time for career explorations ( 26 ). Adolescence is a time of emerging independence (taking on more responsibilities for their own future) but also of interdependence, where self-construal becomes linked to roles and commitments to other groups in society ( 27 ). Identifying the content of these stressors and worries can help governments decide where to propose subsequent policy changes and facilitate society-wide measures. Beyond the need for dedicated mental health services (helplines, centers) called for in earlier papers [e.g., ( 28 )], our data specifically underscore the need for investment of resources into the safe opening of schools, changes to the curriculum and/or the provision of digital education to all young people. Reassurance over access to quality medical care is also a priority.

Within these impacts and worries, there were some gender differences. More females than males reported Academic as a top worry (though this gender difference was not replicated in quantitative impact ratings), which is likely since Indian adolescent females have been reported “more sincere” toward studies than Indian adolescent males, potentially meaning they are more committed and motivated to academic achievement ( 29 ). Males reported a greater impact of COVID-19 on physical health in quantitative ratings; in the Indian context male adolescents are more likely to engage in outdoor sports ( 30 ) and experience fewer sociocultural barriers to outdoor physical activity ( 31 ) than female adolescents. This difference between genders where males spent more time out of the house than females, may also have emerged because males identified social and recreational activities as a top concern; females by contrast, followed restrictions associated with COVID reporting more days in social isolation and on phone/video calls. Perhaps relatedly, more females expressed worries over physical health, fitness, and safety from contracting the virus than male participants. Sedentary lifestyles resulting from the lockdown ( 32 ) may not only affect childhood obesity but can also significantly affect mental health of adolescents. Some interesting trends were also noted in relation to socio-economic status (SES) of the participants, as indexed by the per capita monthly income of their families. Lower SES was associated with a higher impact of COVID across life domains but particularly with impacts on physical health and family. Lower SES was associated with more days participants spent outside of the home, which could explain the reported impact on physical health. Adolescents belonging to lower SES may be residing in crowded living situations, which together with parental stress due to the economic crisis ( 33 ), may mean them having to navigate more complicated family dynamics. Higher SES was associated with more days spent on phone/video calls, probably because participants belonging to higher SES have greater access to laptops, smartphones, and/or tablets than those from lower SES.

In terms of negative and (absence of) positive emotions, means reported in our sample using translated versions of standardized questionnaires were commensurate with those reported in general youth population samples in the west ( 34 ). Self-reported negative affect did not correlate with age, SES and did not vary between males and females but was greater in those reporting more impact of COVID-19 across life domains. Males and those from lower SES reported more anhedonia. These findings pursued longitudinally in time can help us to identify those who show propensity for anxiety/depression across time allowing us to signpost need for mental health resources. Although anhedonia was negatively linked with the impact of COVID-19 on study and social life of the participants, these associations were weak.

There are several study limitations. First, the sample has been obtained using convenience sampling methods (using social media) and responders were only from a few North Indian states. Hence it is difficult to say how representative it is of 12–18 year old Indian adolescents. Moreover, given the study survey requirements, only participants who had access to the Internet and had a registered phone number (to verify parental consent) could be recruited, biasing the study sample composition. However, SES classes seemed to be adequately represented since using the Modified BG Prasad Socio-economic Classification 2019 ( 35 ), (although there was some missing data) the sample reflected the entire continuum of SES classes in India. Second, as data was collected online, qualitative responses were unprobed and very often single word answers had to be coded, affecting the reliability of these data. Nonetheless, inter-rater reliability using this coding scheme was high. Third, participants did not report on whether they lived in rural or urban areas of their respective cities, and therefore our data cannot speak to rural-urban differences in adolescents' worries, negative and positive emotions. Future studies should measure and compare the impact of rural and urban populations on these indices of poor mental health. Finally, many of the scales used were not standardized. However, as internal consistencies were acceptable, this study adds potential new measures for future studies of young people in the Indian context.

Conclusions

Our study showed that even though a handful of participants had personal experiences of or knew someone who had been infected by COVID-19, all our participants reported considerable impact of the pandemic on various aspects of their life, which was linked to higher negative affectivity. Adolescents also expressed worries about their studies, physical health and safety as well as social and recreational activities, with some gender differences. While our findings are unable to demonstrate causality between the impact of these COVID-19 related changes and worries, negative affect and anhedonia, nonetheless, the findings highlight the urgent need for government policy makers to take concrete steps to mitigate potential adverse effects of the pandemic on the mental health of Indian adolescents.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Institutional Ethics Committee, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University (Ref No.: Dean/2020/EC/1975); King's College London Research Ethics Committee (Ref: HR-19/20-18250). Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

JL, MS, VK, RP, TH, LR, and TS contributed to the conception and design of the study. RP, TS, JL, VK, and MS contributed to the development of study materials, contributed to analysis, and interpretation of study data. MS and TS contributed to acquisition of study data. MS and JL wrote first draft of the paper. VK, RP, TS, TH, and LR critiqued the output for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. Ludvigsson JF. Systematic review of COVID 19 in children shows milder cases and a better prognosis than adults. Acta Paediatr. (2020) 109:1088–95. doi: 10.1111/apa.15270

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Götzinger F, Santiago-García B, Noguera-Julián A, Lanaspa M, Lancella L, Carducci FIC, et al. COVID-19 in children and adolescents in Europe: a multinational, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. (2020) 4:653–61. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30177-2

3. Ellis WE, Dumas TM, Forbes LM. Physically isolated but socially connected: Psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Canad J Behav Sci. (2020) 52:177. doi: 10.1037/cbs0000215

4. Ozamiz-Etxebarria N, Dosil-Santamaria M, Picaza-Gorrochategui M, Idoiaga-Mondragon N. Stress, anxiety, and depression levels in the initial stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in a population sample in the northern Spain. Cadernos Saúde Públ. (2020) 36:e00054020. doi: 10.1590/0102-311x00054020

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G, Han M, Xu X, Dong J, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res . (2020) 287:112934. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934

6. Chen F, Zheng D, Liu J, Gong Y, Guan Z, Lou D. Depression and anxiety among adolescents during COVID-19: a cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 88:36–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.061

7. Zhou SJ, Zhang LG, Wang LL, Guo ZC, Wang JQ, Chen JC, et al. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2020) 29:749–58. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01541-4

8. UK Youth. The Impact of COVID-19 on Young People & The Youth Sector . (2020). Available online at: www.ukyouth.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/UK-Youth-Covid-19-Impact-Report-External-Final-08.04.20.pdf (accessed July 22, 2020).

9. Rivenbark JG, Odgers CL, Caspi A, Harrington H, Hogan S, Houts RM, et al. The high societal costs of childhood conduct problems: evidence from administrative records up to age 38 in a longitudinal birth cohort. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2018) 59:703–10. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12850

10. Ewest F, Reinhold T, Vloet TD, Wenning V, Bachmann CJ. Health insurance expenses caused by adolescents with a diagnosis of conduct disorder. Kindheit Entwicklung. (2013) 22:41–7. doi: 10.1026/0942-5403/a000097

CrossRef Full Text

11. Bernfort L, Nordfeldt S, Persson J. ADHD from a socio-economic perspective. Acta Paediatr. (2008) 97:239–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00611.x

12. Depoux A, Martin S, Karafillakis E, Preet R, Wilder-Smith A, Larson H. The pandemic of social media panic travels faster than the COVID-19 outbreak. J Travel Med. (2020) 27:taaa031. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa031

13. O'Connor DB, Aggleton JP, Chakrabarti B, Cooper CL, Creswell C, Dunsmuir S, et al. Research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: a call to action for psychological science. Br J Psychol. (2020) 111:603–29. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12468

14. Holmes EA, O'Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:P547–60. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1

15. Gupta A, Banerjee S, Das S. Significance of geographical factors to the COVID-19 outbreak in India. Model Earth Syst Environ. (2020) 6:2645–53. doi: 10.1007/s40808-020-00838-2

16. Worldometers (2020). Available online at: http://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/india/

17. PIB Delhi. Update on Novel Coronavirus: One Positive Case Reported in Kerala . (2020). Available online at: https://pib.gov.in/pressreleaseiframepage.aspx?prid=1601095 (accessed July 22, 2020).

18. Kaushik S, Kaushik S, Sharma Y, Kumar R, Yadav JP. The Indian perspective of COVID-19 outbreak. VirusDisease . (2020) 31:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s13337-020-00587-x

19. Patra S, Patro BK. COVID-19 and adolescent mental health in India. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 293:113429. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113429

20. Gururaj G, Varghese M, Benegal V, Rao GN, Pathak K, Singh LK, et al. National Mental Health Survey of India, 2015-16: Summary Report . Bengaluru: National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (2016).

21. Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. (1988) 54:1063–70. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

22. Snaith RP, Hamilton M, Morley S, Humayan A, Hargreaves D, Trigwell P. A scale for the assessment of hedonic tone the Snaith–Hamilton pleasure scale. Br J Psychiatry. (1995) 167:99–103. doi: 10.1192/bjp.167.1.99

23. Field A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS (3rd ed.). London: Sage Publications Ltd. (2009).

Google Scholar

24. Trochim WM, Donnelly JP. The Research Methods Knowledge Base 3rd ed. Cincinnati: Atomic Dog (2006).

25. Gravetter F, Wallnau L. Essentials of Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences 8th ed. Belmont: Wadsworth (2014).

26. Tiedeman DV, O'Hara RP. Career Development: Choice and Adjustment . New York, NY: College Entrance Examination Board (1963).

27. Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol Rev. (1991) 98:224–53. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

28. Das S. Mental health and psychosocial aspects of COVID-19 in India: the challenges and responses. J Health Manag. (2020) 22:197–205. doi: 10.1177/0972063420935544

29. Dhull I, Kumari S. Academic stress among adolescent in relation to gender. Int J Appl Res. (2015) 1:394–6. Available online at: https://www.allresearchjournal.com/archives/?year=2015&vol=1&issue=11&part=F&ArticleId=931

30. Swaminathan S, Selvam S, Thomas T, Kurpad AV, Vaz M. Longitudinal trends in physical activity patterns in selected urban south Indian school children. Ind J Med Res. (2011) 134:174–80.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

31. Satija A, Khandpur N, Satija S, Mathur Gaiha S, Prabhakaran D, Reddy KS, et al. Physical activity among adolescents in India: a qualitative study of barriers and enablers. Health Educ Behav. (2018) 45:926–34. doi: 10.1177/1090198118778332

32. Rundle AG, Park Y, Herbstman JB, Kinsey EW, Wang YC. COVID-19–related school closings and risk of weight gain among children. Obesity. (2020) 28:1008–9. doi: 10.1002/oby.22813

33. Cluver L, Lachman JM, Sherr L, Wessels I, Krug E, Rakotomalala S, et al. Parenting in a time of COVID-19. Lancet. (2020) 395:E64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30736-4

34. Leventhal AM, Unger JB, Audrain-McGovern J, Sussman S, Volk HE, Strong DR. Measuring anhedonia in adolescents: a psychometric analysis. J Pers Assess. (2015) 97:506–14. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2015.1029072

35. Pandey VK, Aggarwal P, Kakkar R. Modified BG prasad socio-economic classification, update-2019. Ind J Commun Health. (2019) 31:123–5. Available online at: https://www.iapsmupuk.org/journal/index.php/IJCH/article/view/1055

Keywords: COVID-19, young people, India, worries, emotions

Citation: Shukla M, Pandey R, Singh T, Riddleston L, Hutchinson T, Kumari V and Lau JYF (2021) The Effect of COVID-19 and Related Lockdown Phases on Young Peoples' Worries and Emotions: Novel Data From India. Front. Public Health 9:645183. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.645183

Received: 11 January 2021; Accepted: 26 April 2021; Published: 20 May 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Shukla, Pandey, Singh, Riddleston, Hutchinson, Kumari and Lau. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jennifer Y. F. Lau, jennifer.lau@kcl.ac.uk ; Tushar Singh, tusharsinghalld@gmail.com

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 03 October 2022

How COVID-19 shaped mental health: from infection to pandemic effects

- Brenda W. J. H. Penninx ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7779-9672 1 , 2 ,

- Michael E. Benros ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4939-9465 3 , 4 ,

- Robyn S. Klein 5 &

- Christiaan H. Vinkers ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3698-0744 1 , 2

Nature Medicine volume 28 , pages 2027–2037 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

40k Accesses

127 Citations

488 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Epidemiology

- Infectious diseases

- Neurological manifestations

- Psychiatric disorders

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has threatened global mental health, both indirectly via disruptive societal changes and directly via neuropsychiatric sequelae after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Despite a small increase in self-reported mental health problems, this has (so far) not translated into objectively measurable increased rates of mental disorders, self-harm or suicide rates at the population level. This could suggest effective resilience and adaptation, but there is substantial heterogeneity among subgroups, and time-lag effects may also exist. With regard to COVID-19 itself, both acute and post-acute neuropsychiatric sequelae have become apparent, with high prevalence of fatigue, cognitive impairments and anxiety and depressive symptoms, even months after infection. To understand how COVID-19 continues to shape mental health in the longer term, fine-grained, well-controlled longitudinal data at the (neuro)biological, individual and societal levels remain essential. For future pandemics, policymakers and clinicians should prioritize mental health from the outset to identify and protect those at risk and promote long-term resilience.

Similar content being viewed by others

A longitudinal analysis of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of middle-aged and older adults from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging

Global prevalence of mental health issues among the general population during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and carer mental health: an international multicentre study

In 2019, the COVID-19 outbreak was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO), with 590 million confirmed cases and 6.4 million deaths worldwide as of August 2022 (ref. 1 ). To contain the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) across the globe, many national and local governments implemented often drastic restrictions as preventive health measures. Consequently, the pandemic has not only led to potential SARS-CoV-2 exposure, infection and disease but also to a wide range of policies consisting of mask requirements, quarantines, lockdowns, physical distancing and closure of non-essential services, with unprecedented societal and economic consequences.

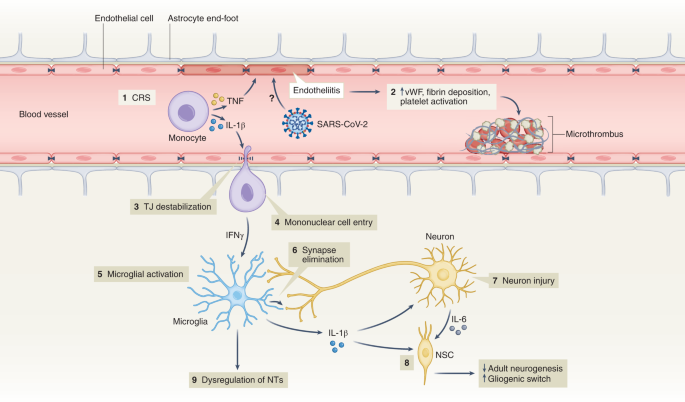

As the world is slowly gaining control over COVID-19, it is timely and essential to ask how the pandemic has affected global mental health. Indirect effects include stress-evoking and disruptive societal changes, which may detrimentally affect mental health in the general population. Direct effects include SARS-CoV-2-mediated acute and long-lasting neuropsychiatric sequelae in affected individuals that occur during primary infection or as part of post-acute COVID syndrome (PACS) 2 —defined as symptoms lasting beyond 3–4 weeks that can involve multiple organs, including the brain. Several terminologies exist for characterizing the effects of COVID-19. PACS also includes late sequalae that constitute a clinical diagnosis of ‘long COVID’ where persistent symptoms are still present 12 weeks after initial infection and cannot be attributed to other conditions 3 .

Here we review both the direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 on mental health. First, we summarize empirical findings on how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted population mental health, through mental health symptom reports, mental disorder prevalence and suicide rates. Second, we describe mental health sequalae of SARS-CoV-2 virus infection and COVID-19 disease (for example, cognitive impairment, fatigue and affective symptoms). For this, we use the term PACS for neuropsychiatric consequences beyond the acute period, and will also describe the underlying neurobiological impact on brain structure and function. We conclude with a discussion of the lessons learned and knowledge gaps that need to be further addressed.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on population mental health

Independent of the pandemic, mental disorders are known to be prevalent globally and cause a very high disease burden 4 , 5 , 6 . For most common mental disorders (including major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorder), environmental stressors play a major etiological role. Disruptive and unpredictable pandemic circumstances may increase distress levels in many individuals, at least temporarily. However, it should be noted that the pandemic not only resulted in negative stressors but also in positive and potentially buffering changes for some, including a better work–life balance, improved family dynamics and enhanced feelings of closeness 7 .

Awareness of the potential mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is reflected in the more than 35,000 papers published on this topic. However, this rapid research output comes with a cost: conclusions from many papers are limited due to small sample sizes, convenience sampling with unclear generalizability implications and lack of a pre-COVID-19 comparison. More reliable estimates of the pandemic mental health impact come from studies with longitudinal or time-series designs that include a pre-pandemic comparison. In our description of the evidence, we, therefore, explicitly focused on findings from meta-analyses that include longitudinal studies with data before the pandemic, as recently identified through a systematic literature search by the WHO 8 .

Self-reported mental health problems

Most studies examining the pandemic impact on mental health used online data collection methods to measure self-reported common indicators, such as mood, anxiety or general psychological distress. Pooled prevalence estimates of clinically relevant high levels of depression and anxiety symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic range widely—between 20% and 35% 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 —but are difficult to interpret due to large methodological and sample heterogeneity. It also is important to note that high levels of self-reported mental health problems identify increased vulnerability and signal an increased risk for mental disorders, but they do not equal clinical caseness levels, which are generally much lower.

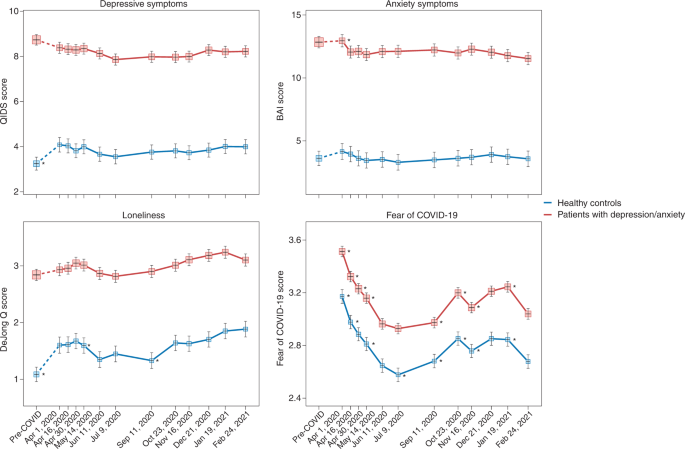

Three meta-analyses, pooling data from between 11 and 61 studies and involving ~50,000 individuals or more 13 , 14 , 15 , compared levels of self-reported mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic with those before the pandemic. Meta-analyses report on pooled effect sizes—that is, weighted averages of study-level effect sizes; these are generally considered small when they are ~0.2, moderate when ~0.5 and large when ~0.8. As shown in Table 1 , meta-analyses on mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic reach consistent conclusions and indicate that there has been a heterogeneous, statistically significant but small increase in self-reported mental health problems, with pooled effect sizes ranging from 0.07 to 0.27. The largest symptom increase was found when using specific mental health outcome measures assessing depression or anxiety symptoms. In addition, loneliness—a strong correlate of depression and anxiety—showed a small but significant increase during the pandemic (Table 1 ; effect size = 0.27) 16 . In contrast, self-reported general mental health and well-being indicators did not show significant change, and psychotic symptoms seemed to have decreased slightly 13 . In Europe, alcohol purchase decreased, but high-level drinking patterns solidified among those with pre-pandemic high drinking levels 17 . When compared to pre-COVID levels, no change in self-reported alcohol use (effect size = −0.01) was observed in a recent meta-analysis summarizing 128 studies from 58 (predominantly European and North American) countries 18 .

What is the time trajectory of self-reported mental health problems during the pandemic? Although findings are not uniform, various large-scale studies confirmed that the increase in mental health problems was highest during the first peak months of the pandemic and smaller—but not fully gone—in subsequent months when infection rates declined and social restrictions eased 13 , 19 , 20 . Psychological distress reports in the United Kingdom increased again during the second lockdown period 15 . Direct associations between anxiety and depression symptom levels and the average number of daily COVID-19 cases were confirmed in the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data 21 . Studies that examined longer-term trajectories of symptoms during the first or even second year of the COVID-19 pandemic are more sparse but revealed stability of symptoms without clear evidence of recovery 15 , 22 . The exception appears to be for loneliness, as some studies confirmed further increasing trends throughout the first COVID-19 pandemic year 22 , 23 . As most published population-based studies were conducted in the early time period in which absolute numbers of SARS-CoV2-infected individuals were still low, the mental health impacts described in such studies are most likely due to indirect rather than direct effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, it is possible that, in longer-term or later studies, these direct and indirect effects may be more intertwined.

The extent to which governmental policies and communication have impacted on population mental health is a relevant question. In cross-country comparisons, the extent of social restrictions showed a dose–response relationship with mental health problems 24 , 25 . In a review of 33 studies worldwide, it was concluded that governments that enacted stringent measures to contain the spread of COVID-19 benefitted not only the physical but also the mental health of their population during the pandemic 26 , even though more stringent policies may lead to more short-term mental distress 25 . It has been suggested that effective communication of risks, choices and policy measures may reduce polarization and conspiracy theories and mitigate the mental health impact of such measures 25 , 27 , 28 .

In sum, the general pattern of results is that of an increase in mental health symptoms in the population, especially during the first pandemic months, that remained elevated throughout 2020 and early 2021. It should be emphasized that this increase has a small effect size. However, even a small upward shift in mental health problems warrants attention as it has not yet shown to be returned to pre-pandemic levels, and it may have meaningful cumulative consequences at the population level. In addition, even a small effect size may mask a substantial heterogeneity in mental health impact, which may have affected vulnerable groups disproportionally (see below).

Mental disorders, self-harm and suicide

Whether the observed increase in mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic has translated into more mental disorders or even suicide mortality is not easy to answer. Mental disorders, characterized by more severe, disabling and persistent symptoms than self-reported mental health problems, are usually diagnosed by a clinician based on the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) criteria or with validated semi-structured clinical interviews. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, research systematically examining the population prevalence of mental disorders has been sparse. Unfortunately, we can also not strongly rely on healthcare use studies as the pandemic impacted on healthcare provision more broadly, thereby making figures of patient admissions difficult to interpret.

On a global scale and based on imputations and modeling from survey data of self-reported mental health problems, the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study 29 estimated that the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a 28% (95% uncertainty interval (UI): 25–30) increase in major depressive disorders and a 26% (95% UI: 23–28) increase in anxiety disorders. It should be noted that these estimations come with high uncertainty as the assumption that transient pandemic-related increases in mental symptoms extrapolate into incident mental disorders remains disputable. So far, only four longitudinal population-based studies have measured and compared current mental (that is, depressive and anxiety) disorder prevalence—defined using psychiatric diagnostic criteria—before and during the pandemic. Of these, two found no change 30 , 31 , one found a decrease 32 and one found an increase in prevalence of these disorders 33 . These studies were local, limited to high-income countries, often small-scale and used different modes of assessment (for example, online versus in-person) before and during the pandemic. This renders these observational results uncertain as well, but their contrast to the GBD calculations 29 is striking.

Time-series analysis of monthly suicide trends in 21 middle-income to high-income countries across the globe yielded no evidence for an increase in suicide rates in the first 4 months of the pandemic, and there was evidence of a fall in rates in 12 countries 34 . Also in the United States, there was a significant decrease in suicide mortality in the first pandemic months but a slight increase in mortality due to drug overdose and homicide 35 . A living systematic review 36 also concluded that, throughout 2020, there was no observed increase in suicide rates in 20 studies conducted in North America, Europe and Asia. Analyses of electronic health record data in the primary care setting showed reduced rates of self-harm during the first COVID-19 pandemic year 37 . In contrast, emergency department visits for self-harm behavior were unchanged 38 or increased 39 . Such inconsistent findings across healthcare settings may reflect a reluctance in healthcare-seeking behavior for mental healthcare issues. In the living systematic review, eight of 11 studies that examined service use data found a significant decrease in reported self-harm/suicide attempts after COVID lockdown, which returned to pre-lockdown levels in some studies with longer follow-up (5 months) 36 .

In sum, although calculations based on survey data predict a global increase of mental disorder prevalence, objective and consistent evidence for an increased mental disorder, self-harm or suicide prevalence or incidence during the first pandemic year remains absent. This observation, coupled with the only small increase in mental health symptom levels in the overall population, may suggest that most of the general population has demonstrated remarkable resilience and adaptation. However, alternative interpretations are possible. First, there is a large degree of heterogeneity in the mental health impact of COVID-19, and increased mental health in one group (for example, due to better work–family balance and work flexibility) may have masked mental health problems in others. Various societal responses seen in many countries, such as community support activities and bolstering mental health and crisis services, may have had mitigating effects on the mental health burden. Also, the relationship between mental health symptom increases during stressful periods and its subsequent effects on the incidence of mental disorders may be non-linear or could be less visible due to resulting alternative outcomes, such as drug overdose or homicide. Finally, we cannot rule out a lag-time effect, where disorders may take more time to develop or be picked up, especially because some of the personal financial or social consequences of the COVID pandemic may only become apparent later. It should be noted that data from low-income countries and longer-term studies beyond the first pandemic year are largely absent.

Which individuals are most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic?

There is substantial heterogeneity across studies that evaluated how the COVID pandemic impacted on mental health 13 , 14 , 15 . Although our society as a whole may have the ability to adequately bounce back from pandemic effects, there are vulnerable people who have been affected more than others.