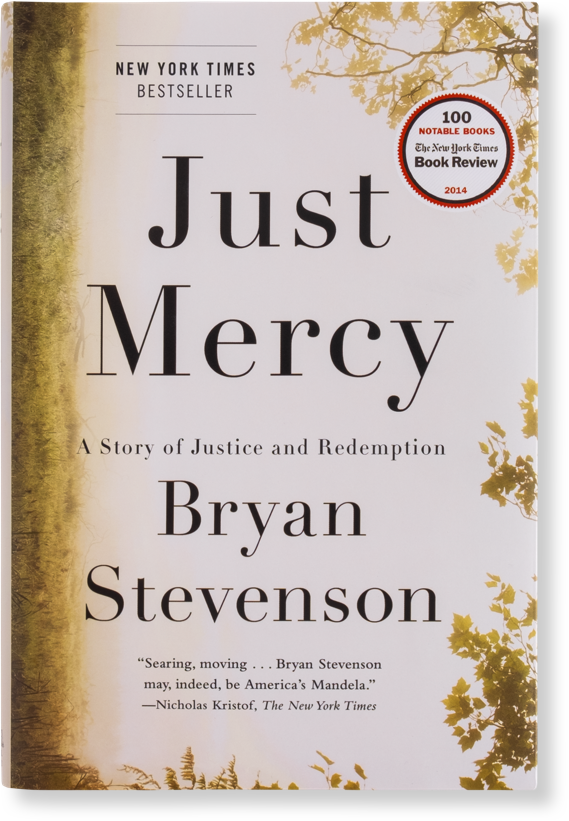

BOOK REVIEW – Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption by Bryan Stevenson

Bryan stevenson, just mercy: a story of justice and redemption , new york, spiegel & grau, an imprint of random house, 2014, 336pp. paperback 2015, reviewed by alan w. clarke.

Your Honor … It was far too easy to convict this wrongly accused man for murder and send him to death row for something he didn’t do and much too hard to win his freedom after proving his innocence. We have serious problems and important work that must be done …”

–Bryan Stevenson, in Walter McMillan’s case.1

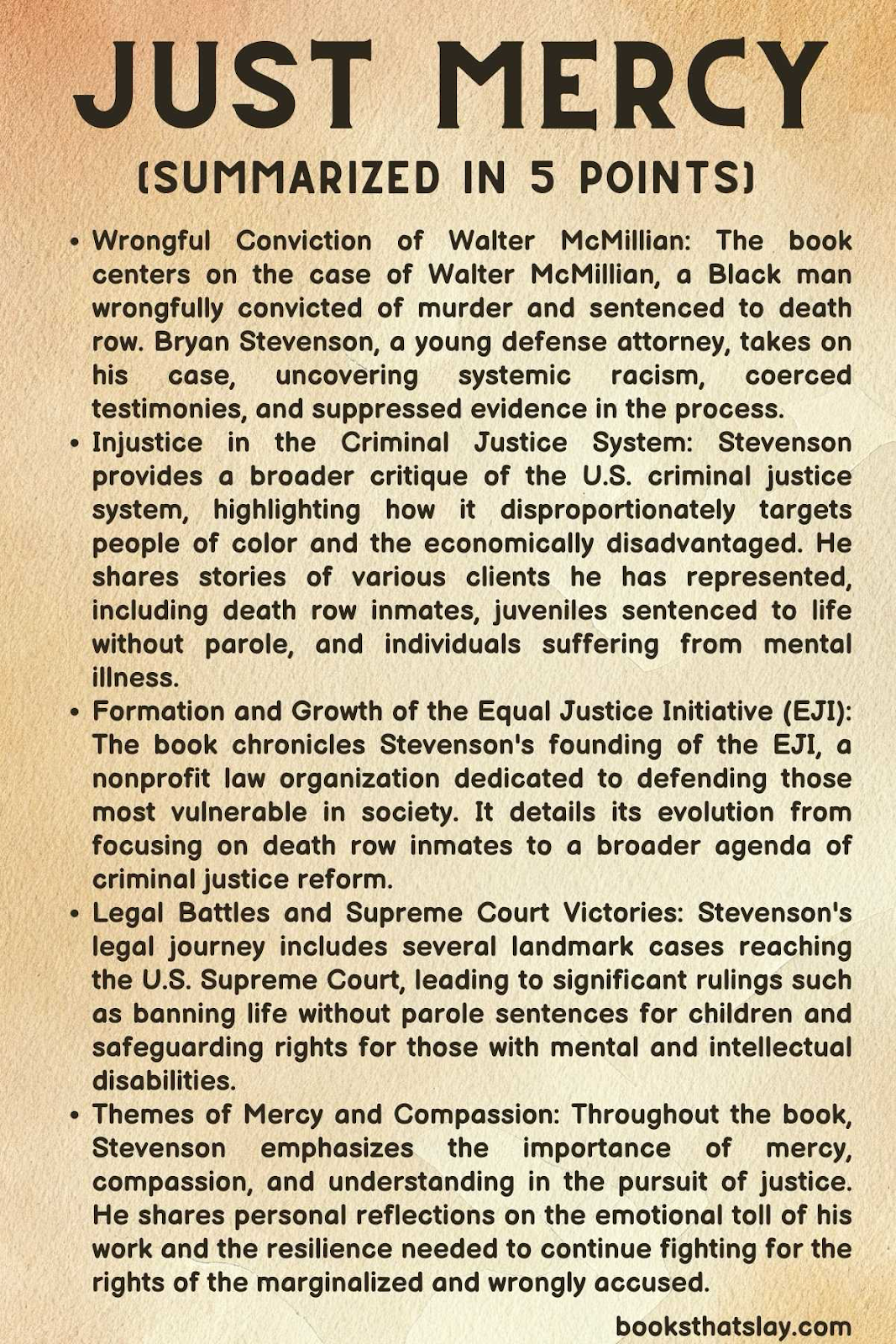

It is no longer reasonably debatable that our inefficient, expensive, broken, racist, criminal justice bureaucracy wrongfully condemns and executes the wholly innocent. That in itself marks an astonishing reordering of opinion since the 1980s when nearly 8 people in 10 supported the death penalty2 and a gubernatorial candidate in Alabama ran for office vowing to “fry them until their eyeballs pop out.”3 Riddled with race and class biases, the U.S. prison–industrial complex also ruins the lives of millions more—mostly poor, despised and discriminated–against minorities, generating the second highest imprisonment rate in the world, second only to the Seychelles4 and by far the largest total prison population of any nation on earth, roundly beating the far more populous China for this dubious distinction.5

Since 1973 courts have been forced, over vigorous and sometimes vicious opposition from prosecutors and police, to free 156 patently innocent victims of America’s experiment with capital punishment.6 While we can never know precisely how many innocent people have been killed by the state, scholars identify 13 who were executed despite probable innocence. In the case of Carlos DeLuna, evidence that Texas killed—perhaps “judicially murdered” would be a better phrase—an innocent man approaches certainty.7 Beyond capital punishment, and in our name, the carceral complex deploys a variety of formally neutral, seemingly facilitative and supposedly disinterested, but in practice racist and classist, mechanisms to ensure quick, inexpensive, but fallible convictions with cruelly long imprisonment for those without money or resources. Justitia may wear a blindfold but she unerringly detects race and class.

Enter into this Stygian morass a very bright, determined, idealistic, nearly broke, and at first splendidly naïve, Harvard trained lawyer, Bryan Stevenson. Just Mercy shines the clearest spotlight yet on our Jim Crow-style judicial pipeline to prison or death. What did he do? His conversation with civil rights icon Rosa Parks summarizes his project nicely:

Ms. Parks turned to me sweetly and asked, ‘now, Bryan tell me who you are and what you’re doing.’ … ‘Yes, ma’am. Well, I have a law project called the Equal Justice Initiative, and we’re trying to help people on death row. We’re trying to stop the death penalty actually. We’re trying to do something about prison conditions and excessive punishment. We want to free people who’ve been wrongfully convicted. We want to end unfair sentences in criminal cases and stop racial bias in criminal justice. We’re trying to help the poor and do something about indigent defense and the fact that people don’t get the legal help they need. We’re trying to help children in adult jails and prisons. We’re trying to do something about poverty and the hopelessness that dominates poor communities. We want to see more diversity in decision-making roles in the justice system. We’re trying to educate people to confront abuse of power by police and prosecutors . . . .’ Ms. Parks leaned back, smiling. ‘Ooooh, honey, all that’s going to make you tired, tired, tired.’8

Walter McMillian’s wrongful conviction predicated on perjured testimony, and a law enforcement cover-up, arguably constitutes Bryan Stevenson’s most celebrated case. It exposed nearly everything wrong with our criminal injustice system—starting with a racist Alabama judge with the improbably appropriate name, Robert E. Lee Key, Jr.—a man who, unlike his namesake, never stopped fighting the civil war. Key’s racism reeked from his first telephone conversation with Stevenson, “This is Judge Key, and you don’t want to have anything to do with this McMillian case. No one really understands how depraved this situation truly is, including me, but I know it’s ugly. These men might even be Dixie Mafia.”9

And, what was McMillian’s sin? A married, successful black man, he outraged the white community by dating a white woman.

Mr. McMillian, … did not have a history of violence, but he was well known in town for something else. Mr. McMillian, … was dating a white woman. … And one of his sons had married a white woman. Roots of suspicion.10

McMillian was arrested, tried, convicted and sentenced to death in Monroeville, Alabama, the natal county of favorite daughter Harper Lee. Her 1960 classic To Kill a Mockingbird eerily foreshadows this case. The film version of Lee’s novel was shot in Monroeville and Gregory Peck, as defense lawyer Atticus Finch, argued his fictional case in the old county courthouse. Brock Peters played the part of Tom Robinson, a black man wrongly charged with and convicted of raping a white woman. Adding to the irony, the community proudly stages a yearly production of the story with the Mockingbird Players. 11 The book, the film, the annually staged play, and a museum commemorating the trial, are the town’s main tourist attractions thus intertwining self-congratulatory civic vainglory with racism and dollops of rancid hypocrisy. 12

For Walter McMillian, as for the fictional Tom Robinson, Monroeville seethed with racism. “The intense rage of the arresting officers and the racist taunts and threats from uniformed police officers who did not know him were shocking.”13 McMillian’s arresting officer unleashed such a torrent of invective that all Walter heard was “‘[n]igger this,’ ‘nigger that,’ followed by insults and threats of lynching.” 14

That law enforcement somehow housed him on death row even before he was tried, much less convicted, speaks volumes about the cozy relationship between police, prosecutor and judge. Stevenson and the reader are left perplexed. How did they manage to put a presumptively innocent man onto death row before trial, verdict, sentence, or even the ordinary prison processes?15

One can only imagine McMillian’s horror at his precipitate and confused change in circumstances, one day innocent and free, and then in a bewildering instant transformed into an innocent man on death row. Sinking into deep despair, 16

[h]is body reacted to the shock of the situation. A lifelong smoker, Walter tried to smoke to calm his nerves, but at Holman [the prison housing Alabama’s death row] he found the experience of smoking nauseating and quit immediately. For days he couldn’t taste anything he ate. He couldn’t orient or calm himself. When he woke each morning, he would feel normal for a few minutes and then sink into terror upon remembering where he was. Prison officials had shaved his head and all the hair from his face. Looking into a mirror he didn’t recognize himself. 17

This is no ordinary case of the wrongful conviction of a black man on death row (the fact that such cases remain all too ordinary is a penetrating indictment of our criminal justice system). It was not even a typical case of wrongful conviction resisted at every level notwithstanding clear evidence of actual innocence, although this too occurs often enough as defensive prosecutors invent ever-nuttier hypotheses of guilt thus compounding their initial error. Far worse than mere incompetence tinged with racism, this capital case exposed the downright framing of an innocent black man, using perjured testimony, for having the audacity to date a white woman.

It is also a tale of perseverance. One follows in awe as Stevenson overcomes one obstacle after another in his improbable untangling of the web of deceit thrown up by law enforcement officers, the prosecutor and judge. Indeed, this is the part that any death penalty post-conviction lawyer will appreciate. Few lawyers harbor the talent, intellect and diligence to, with meager resources, untangle such a deceitful web as the one that ensnared Walter McMillian. This leads to a regrettable conclusion. He was lucky in two respects. First, he had one of the most effective and caring lawyers imaginable. How many others languish in our prisons who, if they have a lawyer at all, have one who isn’t up to such a daunting task?. Second, he had the good fortune, if good fortune it can be called, to draw a foolish judge, who over-rode the jury’s recommendation and sentenced him to death, thus inviting more attention to his case. “If the jury’s sentence of life in prison without parole had been left in place, Mr. McMillian might have been another forgotten black inmate in an Alabama prison.” 18

While working on multiple death row cases, Bryan Stevenson somehow found time to tackle the even more widespread problem of children as young as thirteen or fourteen years old increasingly sentenced in adult courts to life without the possibility of parole. In 2010, as a result of Stevenson’s advocacy, the Supreme Court invalidated “Life imprisonment without parole sentences imposed on children convicted of non-homicide crimes” holding such to be “cruel and unusual punishment and constitutionally impermissible.”19 Then in 2012, also as a result of his efforts, the Supreme Court held that, even in cases of homicide, life without the possibility of parole is unconstitutional.20 These two cases likely had a broader impact in the numbers of people affected than any other case he had handled.

For most lawyers, these achievements alone would mark a successful career in social justice advocacy. Stevenson, always pressed for time, nonetheless also turned his attention to wrongfully convicted “bad moms” whose children were stillborn, or suffered an unexplained death, or who were “criminally prosecuted and sent to prison for decades if there was any evidence that they had used drugs at any point during the pregnancy.” 21

In the process, he exposed an incompetent forensic pathologist “with a history of prematurely and incorrectly declaring deaths to be homicides without adequate supporting evidence.” 22 His work also helped start a movement to assist the “thousands of women—particularly poor women in difficult circumstances—whose children die unexpectedly” countering the wrongful “criminalization … and the persecution of poor women whose children die.” 23 In one case, the “discredited pathologist left Alabama but continues to serve as a practicing medical examiner in Texas.” 24

Stevenson has not only fought racism; he has experienced it. Late one night, exhausted from a hectic day, and while sitting for a few minutes in his car outside his apartment, listening to Sly and the Family Stone on the radio, a police SWAT team accosted him. Systematically humiliated and illegally searched before a growing crowd, he could hear people “talking about all the burglaries in the neighborhood. . . . There was a particularly vocal older white woman who loudly demanded that I be questioned about items she was missing.” 25

“’Ask him about my radio and my vacuum cleaner!’ Another lady asked about her cat who had been absent for three days.”26 Repeated complaints to the Atlanta Police Department’s administrative review process yielded the consistent response that the police had done no wrong. With a crushing caseload, and like so many young black men who have been harassed and stopped and illegally searched, Stevenson eventually dropped the matter. However, unlike those similarly situated young black men, Stevenson did get one last minor victory. Just Mercy exposes all the racism, bigotry and sheer incompetence of Atlanta’s police. It also reveals a callous administrative indifference all the way up the chain of command. Just Mercy shines a penetrating light on entrenched racism in our police and judicial systems. Given Ferguson, Black Lives Matter, and a host of recent incidents, this exposure of indecent, systemic failure is essential reading.

On September 11, 2013, after struggling for years with disabilities and dementia, Walter McMillan died. At his funeral Bryan Stevenson told the congregation at Limestone Faulk A.M.E. Zion Church:

Walter made me understand why we have to reform a system of criminal justice that continues to treat people better if they are rich and guilty than if they are poor and innocent . . . . Walter’s case taught me that fear and anger are a threat to justice; they can infect a community, a state, or a nation and make us blind, irrational, and dangerous . . . . mass imprisonment has littered the national landscape with carceral monuments of reckless and excessive punishment and ravaged communities with our hopeless willingness to condemn and discard the most vulnerable among us . . . . Walter’s case had taught me that the death penalty is not about whether people deserve to die for the crimes they commit, the real question of capital punishment in this country is, Do we deserve to kill? 27

Archbishop Desmond Tutu calls Bryan Stevenson “America’s young Nelson Mandela.” Indeed.

_____________________

- Bryan Stevenson, Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption, (2014) at 225.

- http://deathpenaltyinfo.org/national-polls-and-studies

- Alan W. Clarke, Procedural Labyrinths and the Injustice of Death: A Critique of Death Penalty Habeas Corpus (Part Two) , 30 U. Rich. L. Rev. 303, 355 (1996).

- World Prison Brief, Institute for Criminal Policy Research, available at http://www.prisonstudies.org/highest-to-lowest/prison_population_rate?field_region_taxonomy_tid=All

- Id . http://www.prisonstudies.org/highest-to-lowest/prison-population-total?field_region_taxonomy_tid=All

- Death Penalty Information Center, Innocence and the Death Penalty (April 18, 2016) http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/innocence-and-death-penalty.

- Robert Weisburg, Executing Justice: Anatomy of a Wrongful Execution by James Liebman & the Columbia DeLuna Project , 93 Tex. L. Rev. 1179 (2014).

- Stevenson, supra note 1 at 293.

- Peter Applebome, Alabama Releases Man Held on Death Row for Six Years , N.Y. Times, Mar. 3, 1993, available at http://www.nytimes.com/1993/03/03/us/alabama-releases-man-held-on-death-row-for-six-years.html.

- Jennifer Crossley Howard & Serge F. Kovaleski, ‘Mockingbird’ Reopens in Alabama, 11. Jennifer Crossley Howard & Serge F. Kovaleski, ‘Mockingbird’ Reopens in Alabama, and Drama Plays Out, N.Y, Times, April 17, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/18/books/a-mockingbird-reopens-in-alabama-and-drama-plays-out.html?_r=0.

- Peter Applebome, supra note 10, writes,

. Mr. McMillian’s case, which was given national attention last fall on the CBS News program “60 Minutes,” played out in Monroeville, Ala., best known as the home of the Harper Lee, whose “To Kill a Mockingbird,” told a painful story of race and justice in the small-town Jim Crow South. To many of his defenders, Mr. McMillian’s conviction for the killing seemed like an updated version of the book, in which a black man was accused of raping a white woman.”

- Stevenson, supra note 1, at 55.

- Stevenson writes, “It’s unclear how Tate was able to persuade Holman’s warden to house two pretrial detainees on death row, although Tate knew people at the prison from his days as a probation officer.” Id. at 53.

- Id. at 55–56.

- Stevenson, supra note 1, at 295.

- Miller v. Alabama, 567 U.S. ___ ; 132 S. Ct. 2455 (2012) held that life imprisonment for juveniles without the possibility of parole was unconstitutional. Bryan Stevenson argued the case for the juveniles. Stevenson, supra note 1, at 295-96.

- Stevenson, supra note 1, at 234.

- Id. at 230.

- Id. . at 233.

______________________

Alan W. Clarke is a professor of Integrated Studies at Utah Valley University in Orem, Utah and a contributing editor to National Lawyers Guild Review . His most recent book is Rendition to Torture, published by Rutgers University Press in 2012.

Share this:

I’m still learning from you, while I’m trying to achieve my goals. I definitely love reading all that is posted on your website.Keep the information coming. I liked it!

Inhatelittlenijjni ni ni. Nihg nighnigerzsdfbghuijuingyuisoundghtdghnbou

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Bryan Stevenson

Ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

Welcome to the LitCharts study guide on Bryan Stevenson's Just Mercy . Created by the original team behind SparkNotes, LitCharts are the world's best literature guides.

Just Mercy: Introduction

Just mercy: plot summary, just mercy: detailed summary & analysis, just mercy: themes, just mercy: quotes, just mercy: characters, just mercy: terms, just mercy: symbols, just mercy: theme wheel, brief biography of bryan stevenson.

Historical Context of Just Mercy

Other books related to just mercy.

- Full Title: Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption

- When Written: 2014

- Where Written: United States

- When Published: United States

- Literary Period: Contemporary nonfiction; 21st century African-American criticism

- Genre: Sociopolitical Nonfiction; Legal Nonfiction

- Setting: Monroeville, AL; Montgomery, AL; Atlanta, GA, and several other cities throughout the United States

- Climax: The climax occurs in Chapter 15, on the night of Jimmy Dill’s execution. Dill’s petition for clemency is denied within an hour of his scheduled execution, which is a devastating loss for Stevenson. In addition, Walter’s dementia is causing his decline, and EJI has an almost unmanageable docket of people needing relief. After his heartbreaking phone call with Dill moments before his death, Stevenson feels the weight of all the tragedy and injustice that he has witnessed over the years. He suffers a crisis of faith and considers quitting.

- Antagonist: The Criminal Justice/ Prison System

- Point of View: First Person

Summary and Study Guide

Part memoir , part exhortation for much-needed reform to the American criminal justice system, Bryan Stevenson’s Just Mercy is a heartrending and inspirational call to arms written by the activist lawyer who founded the Equal Justice Initiative, an Alabama-based organization responsible for freeing or reducing the sentences of scores of wrongfully convicted individuals. Stevenson’s memoir weaves together personal stories from his years as a lawyer with strong statements against racial and legal injustice, drawing a clear through line from Antebellum slavery and its legacy to today’s still-prejudiced criminal justice system.

Between the 1970s and 2014, when Stevenson’s memoir was published, the U.S. prison population increased from 300,000 to 2,300,000 – the highest incarceration rate in the world. Of those incarcerated, 58 percent identify as Black or Hispanic. The War on Drugs and “Tough on Crime” policing policies disproportionately target juveniles, women, people of color, the poor, and individuals with mental health issues, all too often the victims of inflated sentences and wrongful convictions resulting in the death penalty. Stevenson animates these harrowing statistics with stories from his years as a criminal defense lawyer, personalizing the political through a powerful series of cases.

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,600+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,850+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

The narrative backbone is the story of Walter McMillian , a young black man falsely accused of murdering a white woman in the small southern town where To Kill a Mockingbird is set. Chapters alternate between chronicling his trial, conviction, and the long road to justice and recounting the stories of other wrongfully persecuted individuals, including a 14-year old named Charlie who is sentenced to life in prison without parole for killing his mother’s abusive boyfriend. Taken as a whole, Just Mercy asks readers to consider the notion that the opposite of poverty is not wealth – it is justice.

By the start of the first chapter, “Mockingbird Players”, Stevenson is a member of the bar in both Georgia and Alabama, and has found himself defending McMillian for the murder of 18-year old Ronda Morrison. While there is no solid evidence pointing to McMillian as the murderer, false accusations, political machinations, and implicit bias against a black man known to be involved in an adulterous interracial relationship all add up to the accusation sticking.

The SuperSummary difference

- 8x more resources than SparkNotes and CliffsNotes combined

- Study Guides you won ' t find anywhere else

- 100+ new titles every month

The chapters that focus on cases outside of McMillian’s demonstrate the staggering legal injustices delivered upon marginalized populations and expose the larger, systemic causes and institutionalized prejudice at work in their uneven treatment.

Chapter 2, “Stand” details several incidents of police brutality and racial profiling, including an encounter Stevenson himself had while listening to music in front of his apartment late one night.

Chapter 4, “Old Rugged Cross”, describes the story of Vietnam War veteran Herbert Richardson, whose case illuminates the struggles Veterans often have in obtaining the medical and mental health support they need, while Chapter 6 (“Surely Doomed”) depicts how widespread legal injustice is for juveniles, many of whom are tried and convicted as adults and receive much harsher sentences than they deserve.

Chapter 8 introduces readers to Tracy, Ian, and Antonio, who continue Stevenson’s exploration of incarcerated children, in these cases for non-homicidal offenses. Through their stories, Stevenson exposes the truth about how children of color are often incarcerated or worse for the same acts white children engage in with impunity. At fourteen, Antonio Nunez became the youngest person in U.S. history to be condemned to death for a crime in which no one was physically injured.

Chapter 10, “Mitigation,” turns its critical lens on the poor and mentally ill prison population, who –though corrections officers are not properly trained to handle mental health issues – make up more than half of those currently incarcerated. The case-in-point in this chapter is Avery Jenkins, who committed murder during a psychotic episode. Through Stevenson’s interventions, he is ultimately moved to a mental health facility better equipped to care for him, one step closer to a society that chooses to rehabilitate rather than incarcerate.

Chapter 12 touches upon impoverished women imprisoned for infant mortality beyond their control, and welfare reform designed to persecute poor, single mothers, and Chapter 14 focuses on physically, cognitively, and behaviorally disabled children who end up imprisoned. Chapter 16 ends on a hopeful note, as on May 17, 2010, the U.S. Supreme Court announced that sentences of life imprisonment without parole imposed on children convicted of non-homicidal crimes was cruel and unusual punishment.

The chapters that trace the unfolding of Walter McMillian’s case build a narrative arc between the late 1980s, when McMillian was accused, and his eventual release in 1993. According to Stevenson’s account, the case involves countless missteps, including sentencing McMillian to the death penalty before his trial officially began, moving the trial proceedings to a wealthier, and thereby whiter, community, where McMillian was less likely to be judged by a jury of his peers, and ignoring several eyewitness accounts that definitively gave the defendant an alibi. Police misconduct (including a paid testimony), perjury, witnesses flipping, and rejected appeals to the state circuit courts also created setbacks. After less than three hours of deliberation, and despite his obvious innocence, the jury found McMillian guilty of the murder of Ronda Morrison and sentenced him to death.

Late-breaking assistance from the television show 60 Minutes raised awareness of the dubiousness of McMillian’s case, and convinced the Monroe County district attorney to bring in the Alabama Bureau of Investigation (ABI). Ultimately, the court ruled in favor of McMillian, and after six years on death row, he was released and cleared of all charges. McMillian became a cause célèbre for criminal justice reform, resulting in the Equal Justice Initiative being selected for an International Human Rights Award.

Chapter 15, “Broken”, ends with an impassioned plea for a reevaluation of the ethics of capital punishment. By 1999, increasing media coverage of the high rate of wrongful convictions finally began to lessen reliance on the death penalty. In the closing chapter of Just Mercy , the lesson Stevenson impresses upon his readers is the urgent need to acknowledge the brokenness of society-wide indifference to the most vulnerable populations in America. Criminal justice reform must begin and end with mercy .

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Related Titles

By Bryan Stevenson

Just Mercy (Adapted for Young Adults): A True Story of the Fight for Justice

Bryan Stevenson

Featured Collections

Audio Study Guides

View Collection

Books on Justice & Injustice

Books on U.S. History

#CommonReads 2020

Common Reads: Freshman Year Reading

Community Reads

True Crime & Legal

clock This article was published more than 9 years ago

Opinion Book review: ‘Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption’ by Bryan Stevenson

A story of justice and redemption.

By Bryan Stevenson Spiegel & Grau. 336 pp. $28

Rob Warden is executive director emeritus of the Center on Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern University School of Law.

Criminal justice in America sometimes seems more criminal than just — replete with error, malfeasance, racism and cruel, if not unusual, punishment, coupled with stubborn resistance to reform and a failure to learn from even its most glaring mistakes. And nowhere, let us pray, are matters worse than in the hard Heart of Dixie, a.k.a. Alabama, the adopted stomping ground of Bryan Stevenson, champion of the damned.

Stevenson, the visionary founder and executive director of the Montgomery-based Equal Justice Initiative, surely has done as much as any other living American to vindicate the innocent and temper justice with mercy for the guilty — efforts that have brought him, among myriad honors, a MacArthur genius grant and honorary degrees from Yale, Penn and Georgetown. Now 54, Stevenson has made his latest contribution to criminal justice in the form of an inspiring memoir titled "Just Mercy."

It will come as no surprise to those who have heard Stevenson speak or perused any of his briefs that “Just Mercy” is an easy read — a work of style, substance and clarity. Mixing commentary and reportage, he adroitly juxtaposes triumph and failure, neither of which is in short supply, against an unfolding backdrop of the saga of Walter McMillian, an innocent black Alabaman sentenced to death for the 1986 murder of an 18-year-old white woman.

Stevenson is something of an enigma. A lifelong bachelor, seemingly married to his work, he grew up in a working-class African American family in southern Delaware. Born five years after Brown v. Board of Education , he endured the indignities of the vestiges of Jim Crow. That, of course, might have set him on a path to champion the downtrodden.

When he was 16, however, his 86-year-old grandfather was murdered by adolescent marauders bent on nothing more than stealing the elderly man’s black-and-white TV. The trauma surrounding the senseless tragedy — occurring as it did in the wake of racially coded political rhetoric about crime — might have turned a lesser person into a reactionary zealot, but Stevenson took a higher road. Within a decade, as a newly minted lawyer, he forsook the wealth that was virtually guaranteed by his degrees from Harvard Law School and the Kennedy School of Government, taking what amounted to a vow of poverty to pursue civil rights law in the South. He began at the Southern Center for Human Rights in Atlanta before moving to Alabama to start the Equal Justice Initiative.

Thirty years on, he has won relief for scores of condemned prisoners; exonerated a number of innocent ones; fought to end the death penalty and life sentences without parole for juveniles; and confronted, with admirable albeit limited success, abuse of the mentally ill, the mentally handicapped and children in prison.

Of all the victories, Stevenson clearly takes the greatest satisfaction in the exoneration of McMillian, whose case played out in Monroeville, Ala. — a town immortalized by Harper Lee in "To Kill a Mockingbird." McMillian's conviction rested on testimony so preposterous that it's astonishing anyone could have believed it, especially in the face of six alibi witnesses, including a police officer, who placed him at a fish fry 11 miles from the scene of the crime when it occurred.

The prosecution sponsored two key witnesses, both of whom lied and one of whom complained in a tape-recorded pretrial interview withheld from the defense that he was being coerced to lie. The other witness, seeking favorable treatment from the prosecution for crimes of his own, testified that he’d seen McMillian’s low-rider truck near the crime scene. It turned out, however, that McMillian had not modified his truck into a low-rider until weeks after the crime.

A jury from which the prosecution had systematically excluded African Americans found McMillian guilty but recommended a life sentence, rather than death. In 34 of the 36 states with death penalties then on their books, jury recommendations were binding, the exceptions being Alabama and Florida, where judges were — and still are — empowered to override jury recommendations. That’s what evocatively named Judge Robert E. Lee Key Jr. did in the McMillian case.

McMillian most likely would have been executed had Stevenson not turned to an unconventional court of last resort — “60 Minutes,” which in late 1992 aired a devastating segment on the case. Three months later, the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals granted McMillian a new trial, and a few days after that, the prosecution dropped the charges.

Another sweet Stevenson victory grew out of his quest to understand why adolescents, like those who murdered his grandfather, are prone to commit violent acts with senseless, reckless abandon. Stevenson took on the representation of several clients sentenced to life in prison without parole for crimes committed as juveniles. In challenging their sentences, he emphasized, as he puts it in his memoir, “the incongruity of not allowing children to smoke, drink, vote . . . because of their well-recognized lack of maturing and judgment while simultaneously treating some of the most at-risk, neglected, and impaired children exactly the same as full-grown adults in the criminal justice system.”

One impaired child Stevenson represented was Evan Miller, who was 14 when he and two other youths beat a middle-aged man to death with a baseball bat after several hours of drinking and using drugs with him. Miller was sentenced to life without parole, but his cohorts accepted plea deals that gave them parole-eligible sentences. Stevenson took Miller's case to the U.S. Supreme Court , which in 2012 held in the case that mandatory life sentences without parole for children violated the Eighth Amendment.

Along the way, Stevenson suffered tragic defeats, some of which speak volumes about the politics of crime and punishment and the hypocrisy it breeds. A case in point is that of Michael Lindsey, who went to the Alabama electric chair in 1989, at age 28, for the murder of a 63-year-old neighbor woman. Lindsey’s guilt was not at issue, but he was black and the victim was white — a situation long known to make a harsh sentence likelier than when the races are reversed.

As in McMillian’s and 99 other Alabama cases so far, Lindsey’s jury recommended a life sentence, but the judge overrode the recommendation, sending him to death row. Stevenson sought clemency for Lindsey, but Gov. Guy Hunt denied it, declaring that he would not “go against the wishes of the community expressed by the jury” — although the jury, in fact, had expressed the wish that Lindsey be allowed to live. Never mind the truth.

A paramount problem with criminal justice in Alabama is that its trial judges are elected — as are those in 38 other states, according to the American Bar Association. Elected judges, not surprisingly, tend to behave like what they in fact are — politicians. As Stevenson explains, judicial candidates attract campaign contributions mostly from business interests in favor of tort reform or from civil trial lawyers against tort reform. The campaign financiers have little interest in criminal justice, but what matters to voters unschooled in tort reform is being tough on crime. “No judge wants to deal with attack ads that highlight the grisly details of a murder case in which the judge failed to impose the most severe punishment,” Stevenson points out.

Judicial override in capital cases has been substantially restricted by case law in Florida but remains unbridled in Alabama — which is and, despite Stevenson’s yeoman efforts, will remain for the foreseeable future a long way from Nirvana.

Thanks in significant part to Stevenson’s brilliance and dedication to a cause that hasn’t always been popular, the situation in Alabama and across the land is improving. Stevenson is not only a great lawyer, he’s also a gifted writer and storyteller. His memoir should find an avid audience among players in the legal system — jurists, prosecutors, defense lawyers, legislators, academics, journalists — and especially anyone contemplating a career in criminal justice.

Just Mercy Summary and Key Lessons

In “Just Mercy,” Bryan Stevenson invites us into his world of legal battles and moral challenges as he advocates for those crushed under the weight of a flawed justice system.

This isn’t just a book; it’s a journey through the heart of America’s struggle with racial and economic injustice, a story of resilience and the quest for mercy.

Just Mercy Summary

At the core of Stevenson’s memoir is the harrowing case of Walter McMillian, a Black businessman wrongfully convicted for the murder of Ronda Morrison.

The account of McMillian’s ordeal is a stark illustration of racial prejudice and legal malfeasance.

Stevenson, a young lawyer at the time, is drawn into Walter’s world, discovering a web of lies, coerced testimonies, and suppressed evidence that paints a chilling picture of a justice system in dire need of reform.

The narrative weaves between Walter’s case and Stevenson’s broader reflections on the American justice system, painting a vivid picture of the various ways it disproportionately impacts people of color and the poor.

From his early days as a law student, deeply moved by his first encounter with a death row inmate, to founding the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) in Alabama, Stevenson’s journey is more than a career – it’s a calling.

Stevenson’s relentless pursuit of justice sees him taking on the most challenging cases: from death row prisoners to juveniles sentenced to life without parole.

His empathy for these marginalized individuals transcends legal advocacy, often leading to deep, personal connections. One such bond is with Walter, who, despite his eventual exoneration and release , suffers the long-term consequences of his unjust imprisonment, passing away in 2013 with Stevenson delivering a moving eulogy.

“Just Mercy” isn’t just a tale of one man or one case.

It’s a mosaic of stories, featuring prisoners from diverse backgrounds, each echoing the broader themes of injustice and the need for compassion. These narratives are deftly interlaced with Stevenson’s reflections on larger societal issues like mental illness, poverty, and the challenges faced by incarcerated women.

A pivotal part of the book details Stevenson’s efforts with EJI to spearhead legal reforms. Their work leads to landmark Supreme Court rulings, including the unconstitutionality of sentencing children to life without parole and executing individuals with severe mental impairments.

Through these victories and heartbreaking losses, Stevenson’s belief in mercy as a crucial component of justice only strengthens.

He shares candidly about moments of doubt and despair, particularly following the execution of a mentally disabled man.

Yet, it’s through his own sense of brokenness that Stevenson finds a deeper connection to his calling, understanding that it’s often those who have suffered who can offer the most profound compassion and advocacy.

Also Read: Born a Crime Summary and Key Lessons

Key Lessons

1. the power of empathy and persistence in advocacy.

Empathy is a potent tool for change, particularly in systems resistant to reform. Bryan Stevenson’s journey in “Just Mercy” underscores the impact of approaching legal advocacy with a deep sense of empathy and understanding.

He shows how putting oneself in another’s shoes, particularly those who are marginalized and voiceless, can drive a more compassionate and effective form of advocacy.

Application

This lesson can be applied in various fields beyond law . Whether you’re in education , healthcare, business , or social work, approaching your profession with empathy can lead to more meaningful connections and impactful results.

This approach involves actively listening to others’ experiences, acknowledging their struggles, and advocating for their needs with persistence and dedication.

In the book, Stevenson tirelessly works to overturn Walter McMillian’s wrongful conviction.

Despite facing numerous obstacles, his empathetic understanding of Walter’s plight and the broader context of racial injustice fuels his relentless pursuit for justice.

This approach not only aids in Walter’s eventual release but also helps Stevenson in forming a deeper connection with him and other clients, enabling a more heartfelt and committed advocacy.

2. Recognizing and Challenging Systemic Injustice

“Just Mercy” highlights the importance of acknowledging and actively challenging systemic injustices, particularly those rooted in racial and economic biases.

Stevenson’s work demonstrates how systemic issues often manifest in individual cases and how addressing these broader patterns is crucial for true reform.

This lesson is valuable for individuals in any sector that deals with systemic issues, such as education, healthcare, social services, or criminal justice.

It involves developing an awareness of the larger systems at play, understanding how they affect individual lives, and striving to implement changes that address these underlying issues.

Throughout the book, Stevenson not only focuses on individual cases but also addresses the larger systemic problems, like the disproportionate incarceration of people of color and the poor.

His establishment of the Equal Justice Initiative is a direct response to these systemic injustices, aiming to provide legal representation to those who are most vulnerable and to challenge unfair sentencing practices and conditions of confinement.

Also Read: The Simple Path To Wealth Summary and Key Lessons

3. The Importance of Resilience in the Face of Adversity

Stevenson’s journey in “Just Mercy” teaches the importance of resilience when facing challenging and often disheartening circumstances.

The book shows that in the pursuit of justice and reform, setbacks and failures are inevitable, but perseverance and resilience can lead to significant breakthroughs and change.

This lesson is universally applicable, whether in personal endeavors, professional goals, or social activism.

It involves maintaining focus on your objectives despite obstacles, learning from failures, and persisting in your efforts, driven by a deep-seated belief in your cause.

A poignant instance of this lesson is Stevenson’s handling of the setbacks in Walter McMillian’s case.

Despite the frustration of legal hurdles and the initial failure to overturn Walter’s conviction, Stevenson doesn’t give up. His resilience is evident as he continues to investigate, uncover new evidence, and persist through the legal battles until he achieves justice for Walter.

This resilience in the face of adversity is a central theme in the book and a key driver of Stevenson’s success in advocating for criminal justice reform.

Final Thoughts

“Just Mercy” is more than an autobiography or a legal drama; it’s a powerful testament to the capacity for change in even the most daunting circumstances. Stevenson’s story is one of hope, a reminder that within the complexities of the legal system, there’s always room for humanity and mercy.

Read our other summaries

- No Excuses Summary and Key Lessons

- Irresistible Summary and Key Lessons | Adam Alter

- What Happened To You Summary and Key Lessons

- Salt: A World History Summary and Key Lessons

- The High 5 Habit Summary and Key Lessons

Sharing is Caring!

A team of Editors at Books That Slay.

Passionate | Curious | Permanent Bibliophiles

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Movie Reviews

'just mercy': an earnest, effective legal drama.

Andrew Lapin

Bryan Stevenson (Michael B. Jordan) defends wrongly condemned Walter McMillan (Jamie Foxx) in Destin Daniel Cretton's film. Jake Giles Netter/Warner Bros. hide caption

Bryan Stevenson (Michael B. Jordan) defends wrongly condemned Walter McMillan (Jamie Foxx) in Destin Daniel Cretton's film.

Just Mercy , the attorney Bryan Stevenson's 2014 bestseller, has already become a touchstone of criminal justice writing for helping change the conversation around capital punishment in America. It tells the true story of Stevenson's efforts to free a poor black man in Alabama, Walter McMillian, who spent six years on death row for a murder he plainly did not commit, imprisoned on flimsy evidence brought forward by a white sheriff and district attorney.

The invocation of race, class, and setting in McMillian's case is unmissable — particularly since he was from Monroeville, Alabama, home of Harper Lee and To Kill A Mockingbird , and residents seemed to be living out a remake of her novel with zero lessons learned. We're in a climate of heightened public awareness around these disparities in the criminal justice system, which means stories like this have become cultural flashpoints for reasons entirely beyond the crime itself. Case in point: The new film adaptation of Just Mercy opens one week after Curtis Flowers, a black man in Mississippi, found his own temporary relief from a two-decade legal saga that mirrors McMillian's own.

With all this weighted context, the fact that Just Mercy works is a pleasant surprise. Not only does the drama grant respect and dignity to the key figures of the original case, but writer-director Destin Daniel Cretton (adapting the book with co-writer Andrew Lanham) also touches on larger issues about the morality of the death penalty at large. The delayed exoneration of an innocent black man is a relatively straightforward narrative, one that tracks easily with audience sympathies (although the fact that this happened in the '90s, instead of the '50s, should disturb people). But to use McMillian's story to ask whether anyone , even the guilty, deserves the electric chair? That's a much thornier, more unsettling question, one more befitting the life's work of its hero.

N.C. Supreme Court Hears Arguments On Racial Bias In Death Penalty Cases

We follow Stevenson as he moves to Montgomery in 1989 to found the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit that provides legal assistance to death row cases in Alabama. The attorney is played by Michael B. Jordan, who's also a producer (as is Stevenson himself). Jordan's best-known roles ( Creed, Black Panther ) have him playing the brash young upstart with swagger for days, but here he has to bury his charisma underneath stuffy suits, legalese, and general unease. For once, his character's inexperience and outsider status work against him, although Jordan's never quite able to demonstrate what exactly is motivating this Harvard-educated Delaware native to voluntarily move to the Deep South to work on capital punishment cases for no money. The film's answer is essentially naked idealism, which is fine as things go, but it makes Stevenson seem more like a do-gooder cipher than a character.

Stevenson soon finds his ideal case in McMillian (Jamie Foxx), whose conviction for the murder of an 18-year-old white woman rested almost entirely on some fantastical witness testimony. Foxx's performance is a subtle balancing act, making McMillian a simple figure who has also seen his good faith hardened by years of unfair treatment. In testy exchanges, he maintains his innocence while also accepting, on some level, that death row has become his home.

Cretton doesn't dramatize the actual murder, keeping the film from drifting too far into lurid true-crime territory. He focuses instead on Stevenson's efforts to win the trust of McMillian's family, challenge the unsympathetic district attorney (Rafe Spall), convince a key witness (Tim Blake Nelson) to recant his testimony, and attempt to aid other men on death row at the same time. In a deeply affecting subplot, the great actor Rob Morgan ( Mudbound ) plays a mentally ill veteran who, though he's responsible for an innocent's death, is nevertheless a thinking, feeling person who must live with the knowledge that the electric chair awaits him. The scene in which he's prepared for his execution, eyebrows shaved off in silence amid the harsh yellow glare of the prison, is a vital reminder that we cannot look away from that which we choose to condone.

That Cretton makes this ambitious message work at all is in itself a sigh of relief. He's a big-hearted filmmaker with an eye for social causes, but the brilliance of his breakout film, the tender foster-care drama Short Term 12 ,was followed by the tone-deaf calamity of the memoir adaptation The Glass Castle , a movie incapable of recognizing the difference between eccentricity and outright abuse. Both starred Brie Larson, who also has a supporting role here, and though she's playing a real person (EJI's longtime operations director Eva Ansley), the script gives her no functional narrative purpose except to allow the audience to see a white face on the side of justice. In those moments and others, like a brief scene that makes no fewer than three heavily underlined references to Mockingbird , there are hints that Cretton may be too overwhelmed with the principle of what he's filming to do it justice as a film.

But ultimately Cretton pays enough attention to the tough details of McMillian's journey, and to the harsh realities of capital punishment and racism it prompts, to sell Just Mercy 's unflagging earnestness. What this movie really does well is bring the straightforward politics of a Mockingbird -esque crusading legal drama into our modern dialogue around mass incarceration and the death penalty. And even the happy ending leaves us with the unsettling knowledge that we're still far too deep in these woods.

- Biographies & Memoirs

- Community & Culture

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } -39% $11.06 $ 11 . 06 FREE delivery Saturday, May 18 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon.com Sold by: Amazon.com

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Save with Used - Good .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } $6.11 $ 6 . 11 FREE delivery May 25 - 31 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon Sold by: Martistore

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Follow the author

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption Paperback – August 18, 2015

Purchase options and add-ons.

- Print length 368 pages

- Language English

- Publisher One World

- Publication date August 18, 2015

- Dimensions 5.17 x 0.77 x 7.96 inches

- ISBN-10 9780812984965

- ISBN-13 978-0812984965

- Lexile measure 1130L

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Similar items that may ship from close to you

From the Publisher

Editorial Reviews

About the author, excerpt. © reprinted by permission. all rights reserved..

Chapter One

Mockingbird Players

The temporary receptionist was an elegant African American woman wearing a dark, expensive business suit—a well-dressed exception to the usual crowd at the Southern Prisoners Defense Committee (SPDC) in Atlanta, where I had returned after graduation to work full time. On her first day, I’d rambled over to her in my regular uniform of jeans and sneakers and offered to answer any questions she might have to help her get acclimated. She looked at me coolly and waved me away after reminding me that she was, in fact, an experienced legal secretary. The next morning, when I arrived at work in another jeans and sneakers ensemble, she seemed startled, as if some strange vagrant had made a wrong turn into the office. She took a beat to compose herself, then summoned me over to confide that she was leaving in a week to work at a “real law office.” I wished her luck. An hour later, she called my office to tell me that “Robert E. Lee” was on the phone. I smiled, pleased that I’d misjudged her; she clearly had a sense of humor.

“That’s really funny.”

“I’m not joking. That’s what he said,” she said, sounding bored, not playful. “Line two.”

I picked up the line.

“Hello, this is Bryan Stevenson. May I help you?”

“Bryan, this is Robert E. Lee Key. Why in the hell would you want to represent someone like Walter McMillian? Do you know he’s reputed to be one of the biggest drug dealers in all of South Alabama? I got your notice entering an appearance, but you don’t want anything to do with this case.”

“This is Judge Key, and you don’t want to have anything to do with this McMillian case. No one really understands how depraved this situation truly is, including me, but I know it’s ugly. These men might even be Dixie Mafia.”

The lecturing tone and bewildering phrases from a judge I’d never met left me completely confused. “Dixie Mafia”? I’d met Walter McMillian two weeks earlier, after spending a day on death row to begin work on five capital cases. I hadn’t reviewed the trial transcript yet, but I did remember that the judge’s last name was Key. No one had told me the Robert E. Lee part. I struggled for an image of “Dixie Mafia” that would fit Walter McMillian.

“ ‘Dixie Mafia’?”

“Yes, and there’s no telling what else. Now, son, I’m just not going to appoint some out-of-state lawyer who’s not a member of the Alabama bar to take on one of these death penalty cases, so you just go ahead and withdraw.”

“I’m a member of the Alabama bar.”

I lived in Atlanta, Georgia, but I had been admitted to the Alabama bar a year earlier after working on some cases in Alabama concerning jail and prison conditions.

“Well, I’m now sitting in Mobile. I’m not up in Monroeville anymore. If we have a hearing on your motion, you’re going to have to come all the way from Atlanta to Mobile. I’m not going to accommodate you no kind of way.”

“I understand, sir. I can come to Mobile, if necessary.”

“Well, I’m also not going to appoint you because I don’t think he’s indigent. He’s reported to have money buried all over Monroe County.”

“Judge, I’m not seeking appointment. I’ve told Mr. McMillian that we would—” The dial tone interrupted my first affirmative statement of the phone call. I spent several minutes thinking we’d been accidentally disconnected before finally realizing that a judge had just hung up on me.

I was in my late twenties and about to start my fourth year at the SPDC when I met Walter McMillian. His case was one of the flood of cases I’d found myself frantically working on after learning of a growing crisis in Alabama. The state had nearly a hundred people on death row as well as the fastest-growing condemned population in the country, but it also had no public defender system, which meant that large numbers of death row prisoners had no legal representation of any kind. My friend Eva Ansley ran the Alabama Prison Project, which tracked cases and matched lawyers with the condemned men. In 1988, we discovered an opportunity to get federal funding to create a legal center that could represent people on death row. The plan was to use that funding to start a new nonprofit. We hoped to open it in Tuscaloosa and begin working on cases in the next year. I’d already worked on lots of death penalty cases in several Southern states, sometimes winning a stay of execution just minutes before an electrocution was scheduled. But I didn’t think I was ready to take on the responsibilities of running a nonprofit law office. I planned to help get the organization off the ground, find a director, and then return to Atlanta.

When I’d visited death row a few weeks before that call from Robert E. Lee Key, I met with five desperate condemned men: Willie Tabb, Vernon Madison, Jesse Morrison, Harry Nicks, and Walter McMillian. It was an exhausting, emotionally taxing day, and the cases and clients had merged together in my mind on the long drive back to Atlanta. But I remembered Walter. He was at least fifteen years older than me, not particularly well educated, and he hailed from a small rural community. The memorable thing about him was how insistent he was that he’d been wrongly convicted.

“Mr. Bryan, I know it may not matter to you, but it’s important to me that you know that I’m innocent and didn’t do what they said I did, not no kinda way,” he told me in the meeting room. His voice was level but laced with emotion. I nodded to him. I had learned to accept what clients tell me until the facts suggest something else.

“Sure, of course I understand. When I review the record I’ll have a better sense of what evidence they have, and we can talk about it.”

“But . . . look, I’m sure I’m not the first person on death row to tell you that they’re innocent, but I really need you to believe me. My life has been ruined! This lie they put on me is more than I can bear, and if I don’t get help from someone who believes me—”

His lip began to quiver, and he clenched his fists to stop himself from crying. I sat quietly while he forced himself back into composure.

“I’m sorry, I know you’ll do everything you can to help me,” he said, his voice quieter. My instinct was to comfort him; his pain seemed so sincere. But there wasn’t much I could do, and after several hours on the row talking to so many people, I could muster only enough energy to reassure him that I would look at everything carefully.

I had several transcripts piled up in my small Atlanta office ready to move to Tuscaloosa once the office opened. With Judge Robert E. Lee Key’s peculiar comments still running through my head, I went through the mound of records until I found the transcripts from Walter McMillian’s trial. There were only four volumes of trial proceedings, which meant that the trial had been short. The judge’s dramatic warnings now made Mr. McMillian’s emotional claim of innocence too intriguing to put off any longer. I started reading.

Even though he had lived in Monroe County his whole life, Walter McMillian had never heard of Harper Lee or To Kill a Mockingbird. Monroeville, Alabama, celebrated its native daughter Lee shamelessly after her award-winning book became a national bestseller in the 1960s. She returned to Monroe County but secluded herself and was rarely seen in public. Her reclusiveness proved no barrier to the county’s continued efforts to market her literary classic—or to market itself by using the book’s celebrity. Production of the film adaptation brought Gregory Peck to town for the infamous courtroom scenes; his performance won him an Academy Award. Local leaders later turned the old courthouse into a “Mockingbird” museum. A group of locals formed “The Mockingbird Players of Monroeville” to present a stage version of the story. The production was so popular that national and international tours were organized to provide an authentic presentation of the fictional story to audiences everywhere.

Sentimentality about Lee’s story grew even as the harder truths of the book took no root. The story of an innocent black man bravely defended by a white lawyer in the 1930s fascinated millions of readers, despite its uncomfortable exploration of false accusations of rape involving a white woman. Lee’s endearing characters, Atticus Finch and his precocious daughter Scout, captivated readers while confronting them with some of the realities of race and justice in the South. A generation of future lawyers grew up hoping to become the courageous Atticus, who at one point arms himself to protect the defenseless black suspect from an angry mob of white men looking to lynch him.

Today, dozens of legal organizations hand out awards in the fictional lawyer’s name to celebrate the model of advocacy described in Lee’s novel. What is often overlooked is that the black man falsely accused in the story was not successfully defended by Atticus. Tom Robinson, the wrongly accused black defendant, is found guilty. Later he dies when, full of despair, he makes a desperate attempt to escape from prison. He is shot seventeen times in the back by his captors, dying ingloriously but not unlawfully.

Walter McMillian, like Tom Robinson, grew up in one of several poor black settlements outside of Monroeville, where he worked the fields with his family before he was old enough to attend school. The children of sharecroppers in southern Alabama were introduced to “plowin’, plantin’, and pickin’ ” as soon as they were old enough to be useful in the fields. Educational opportunities for black children in the 1950s were limited, but Walter’s mother got him to the dilapidated “colored school” for a couple of years when he was young. By the time Walter was eight or nine, he became too valuable for picking cotton to justify the remote advantages of going to school. By the age of eleven, Walter could run a plow as well as any of his older siblings.

Times were changing—for better and for worse. Monroe County had been developed by plantation owners in the nineteenth century for the production of cotton. Situated in the coastal plain of southwest Alabama, the fertile, rich black soil of the area attracted white settlers from the Carolinas who amassed very successful plantations and a huge slave population. For decades after the Civil War, the large African American population toiled in the fields of the “Black Belt” as sharecroppers and tenant farmers, dependent on white landowners for survival. In the 1940s, thousands of African Americans left the region as part of the Great Migration and headed mostly to the Midwest and West Coast for jobs. Those who remained continued to work the land, but the out-migration of African Americans combined with other factors to make traditional agriculture less sustainable as the economic base of the region.

By the 1950s, small cotton farming was becoming increasingly less profitable, even with the low-wage labor provided by black sharecroppers and tenants. The State of Alabama agreed to help white landowners in the region transition to timber farming and forest products by providing extraordinary tax incentives for pulp and paper mills. Thirteen of the state’s sixteen pulp and paper mills were opened during this period. Across the Black Belt, more and more acres were converted to growing pine trees for paper mills and industrial uses. African Americans, largely excluded from this new industry, found themselves confronting new economic challenges even as they won basic civil rights. The brutal era of sharecropping and Jim Crow was ending, but what followed was persistent unemployment and worsening poverty. The region’s counties remained some of the poorest in America.

Walter was smart enough to see the trend. He started his own pulpwood business that evolved with the timber industry in the 1970s. He astutely—and bravely—borrowed money to buy his own power saw, tractor, and pulpwood truck. By the 1980s, he had developed a solid business that didn’t generate a lot of extra money but afforded him a gratifying degree of independence. If he had worked at the mill or the factory or had had some other unskilled job—the kind that most poor black people in South Alabama worked—it would invariably mean working for white business owners and dealing with all the racial stress that that implied in Alabama in the 1970s and 1980s. Walter couldn’t escape the reality of racism, but having his own business in a growing sector of the economy gave him a latitude that many African Americans did not enjoy.

That independence won Walter some measure of respect and admiration, but it also cultivated contempt and suspicion, especially outside of Monroeville’s black community. Walter’s freedom was, for some of the white people in town, well beyond what African Americans with limited education were able to achieve through legitimate means. Still, he was pleasant, respectful, generous, and accommodating, which made him well liked by the people with whom he did business, whether black or white.

Walter was not without his flaws. He had long been known as a ladies’ man. Even though he had married young and had three children with his wife, Minnie, it was well known that he was romantically involved with other women. “Tree work” is notoriously demanding and dangerous. With few ordinary comforts in his life, the attention of women was something Walter did not easily resist. There was something about his rough exterior—his bushy long hair and uneven beard—combined with his generous and charming nature that attracted the attention of some women.

Walter grew up understanding how forbidden it was for a black man to be intimate with a white woman, but by the 1980s he had allowed himself to imagine that such matters might be changing. Perhaps if he hadn’t been successful enough to live off his own business he would have more consistently kept in mind those racial lines that could never be crossed. As it was, Walter didn’t initially think much of the flirtations of Karen Kelly, a young white woman he’d met at the Waffle House where he ate breakfast. She was attractive, but he didn’t take her too seriously. When her flirtations became more explicit, Walter hesitated, and then persuaded himself that no one would ever know.

After a few weeks, it became clear that his relationship with Karen was trouble. At twenty-five, Karen was eighteen years younger than Walter, and she was married. As word got around that the two were “friends,” she seemed to take a titillating pride in her intimacy with Walter. When her husband found out, things quickly turned ugly. Karen and her husband, Joe, had long been unhappy and were already planning to divorce, but her scandalous involvement with a black man outraged Karen’s husband and his entire family. He initiated legal proceedings to gain custody of their children and became intent on publicly disgracing his wife by exposing her infidelity and revealing her relationship with a black man.

For his part, Walter had always stayed clear of the courts and far away from the law. Years earlier, he had been drawn into a bar fight that resulted in a misdemeanor conviction and a night in jail. It was the first and only time he had ever been in trouble. From that point on, he had no exposure to the criminal justice system.

When Walter received a subpoena from Karen Kelly’s husband to testify at a hearing where the Kellys would be fighting over their children’s custody, he knew it was going to cause him serious problems. Unable to consult with his wife, Minnie, who had a better head for these kinds of crises, he nervously went to the courthouse. The lawyer for Kelly’s husband called Walter to the stand. Walter had decided to acknowledge being a “friend” of Karen. Her lawyer objected to the crude questions posed to Walter by the husband’s attorney about the nature of his friendship, sparing him from providing any details, but when he left the courtroom the anger and animosity toward him were palpable. Walter wanted to forget about the whole ordeal, but word spread quickly, and his reputation shifted. No longer the hard-working pulpwood man, known to white people almost exclusively for what he could do with a saw in the pine trees, Walter now represented something more worrisome.

Fears of interracial sex and marriage have deep roots in the United States. The confluence of race and sex was a powerful force in dismantling Reconstruction after the Civil War, sustaining Jim Crow laws for a century and fueling divisive racial politics throughout the twentieth century. In the aftermath of slavery, the creation of a system of racial hierarchy and segregation was largely designed to prevent intimate relationships like Walter and Karen’s—relationships that were, in fact, legally prohibited by “anti-miscegenation statutes” (the word miscegenation came into use in the 1860s, when supporters of slavery coined the term to promote the fear of interracial sex and marriage and the race mixing that would result if slavery were abolished). For over a century, law enforcement officials in many Southern communities absolutely saw it as part of their duty to investigate and punish black men who had been intimate with white women.

Although the federal government had promised racial equality for freed former slaves during the short period of Reconstruction, the return of white supremacy and racial subordination came quickly after federal troops left Alabama in the 1870s. Voting rights were taken away from African Americans, and a series of racially restrictive laws enforced the racial hierarchy. “Racial integrity” laws were part of a plan to replicate slavery’s racial hierarchy and reestablish the subordination of African Americans. Having criminalized interracial sex and marriage, states throughout the South would use the laws to justify the forced sterilization of poor and minority women. Forbidding sex between white women and black men became an intense preoccupation throughout the South.

In the 1880s, a few years before lynching became the standard response to interracial romance and a century before Walter and Karen Kelly began their affair, Tony Pace, an African American man, and Mary Cox, a white woman, fell in love in Alabama. They were arrested and convicted, and both were sentenced to two years in prison for violating Alabama’s racial integrity laws. John Tompkins, a lawyer and part of a small minority of white professionals who considered the racial integrity laws to be unconstitutional, agreed to represent Tony and Mary to appeal their convictions. The Alabama Supreme Court reviewed the case in 1882. With rhetoric that would be quoted frequently over the next several decades, Alabama’s highest court affirmed the convictions, using language that dripped with contempt for the idea of interracial romance:

The evil tendency of the crime [of adultery or fornication] is greater when committed between persons of the two races. . . . Its result may be the amalgamation of the two races, producing a mongrel population and a degraded civilization, the prevention of which is dictated by a sound policy affecting the highest interests of society and government.

Product details

- ASIN : 081298496X

- Publisher : One World; Reprint edition (August 18, 2015)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 368 pages

- ISBN-10 : 9780812984965

- ISBN-13 : 978-0812984965

- Lexile measure : 1130L

- Item Weight : 2.31 pounds

- Dimensions : 5.17 x 0.77 x 7.96 inches

- #1 in Criminal Procedure Law

- #5 in Criminology (Books)

- #147 in Memoirs (Books)

Videos for this product

Click to play video

Just Mercy Book.mov

Influencer Video

Review of Just Mercy by Bryan Stevenson | Worth a read?

🌟Turner Family Reviews🌟

Customer Review: Amazing

A very important read for everyone

The MusiCal MusiGal

If you read 1 book this year, read Just Mercy! Life changing

✅ Only the Best ✅

A troubling look at America’s broken criminal justice system.

Just Mercy Video

Merchant Video

The writing is easy to read but it's a heavy story

Should I Get It Reviews

About the author

Bryan stevenson.

Bryan Stevenson is the executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama, and a professor of law at New York University Law School. He has won relief for dozens of condemned prisoners, argued five times before the Supreme Court, and won national acclaim for his work challenging bias against the poor and people of color. He has received numerous awards, including the MacArthur Foundation “Genius” Grant.

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Reviews with images

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Advertisement

Supported by

‘Just Mercy,’ by Bryan Stevenson

- Share full article

By Ted Conover

- Oct. 17, 2014

Unfairness in the Justice system is a major theme of our age. DNA analysis exposes false convictions, it seems, on a weekly basis. The predominance of racial minorities in jails and prisons suggests systemic bias. Sentencing guidelines born of the war on drugs look increasingly draconian. Studies cast doubt on the accuracy of eyewitness testimony. Even the states that still kill people appear to have forgotten how; lately executions have been botched to horrific effect.

This news reaches citizens in articles and television spots about mistreated individuals. But “Just Mercy,” a memoir, aggregates and personalizes the struggle against injustice in the story of one activist lawyer.

Bryan Stevenson grew up poor in Delaware. His great-grandparents had been slaves in Virginia. His grandfather was murdered in a Philadelphia housing project when Stevenson was a teenager. Stevenson attended Eastern College (now Eastern University), a Christian institution outside Philadelphia, and then Harvard Law School. Afterward he began representing poor clients in the South, first in Georgia and then in Alabama, where he was a co-founder of the Equal Justice Initiative.

“Just Mercy” focuses mainly on that work, and those clients. Its narrative backbone is the story of Walter McMillian, whom Stevenson began representing in the late 1980s when he was on death row for killing a young white woman in Monroeville, Ala., the hometown of Harper Lee. Monroeville has long promoted its connection to “To Kill a Mockingbird,” which is about a black man falsely accused of the rape of a white woman. As Stevenson writes, “Sentimentality about Lee’s story grew even as the harder truths of the book took no root.” Walter McMillian had never heard of the book, and had scarcely been in trouble with the law. He had, however, been having an affair with a white woman, and Stevenson makes a persuasive case that it made McMillian, who cut timber for a living, vulnerable to prosecution.

McMillian’s ordeal is a good subject for Stevenson, first of all because it was so outrageous. The reader quickly comes to root for McMillian as authorities gin up a case against him, ignore the many eyewitnesses who were with him at a church fund-raiser at his home when the murder took place, and send him — before trial — to death row in the state pen. When the almost entirely white jury returns a sentence of life in prison, the judge, named Robert E. Lee Key, takes it upon himself to convert it to the death penalty.

Stevenson’s is not the first telling of this miscarriage of justice: “60 Minutes” did a segment on it, and the journalist Pete Earley wrote a book about the case, “Circumstantial Evidence” (1995). McMillian’s release in 1993 made the front page of The New York Times. But this book brings new life to the story by placing it in two affecting contexts: Stevenson’s life’s work and the deep strain of racial injustice in American life. McMillian’s was a foundational case for the author, both professionally and personally; the exoneration burnished his reputation. A strength of this account is that instead of the Hollywood moment of people cheering and champagne popping when the court finally frees McMillian, Stevenson admits he was “confused by my suddenly simmering anger.” He found himself thinking of how much pain had been visited on McMillian and his family and community, and about others wrongly convicted who hadn’t received the death penalty and thus were less likely to attract the attention of activist lawyers.

Stevenson uses McMillian’s case to illustrate his commitment both to individual defendants — he remained closely in touch until McMillian’s death last year — and to endemic problems in American jurisprudence. The more success Stevenson has fighting his hopeless causes, the more support he attracts. Soon he has won a MacArthur “genius” grant, Sweden’s Olof Palme prize and other awards and distinctions, and is attracting enough federal and foundation support to field a whole staff. By the second half of the book, they are taking on mandatory life sentences for children (now abolished) and broader measures to encourage Americans to recognize the legacy of slavery in today’s criminal justice system.

As I read this book I kept thinking of Paul Farmer, the physician who has devoted his life to improving health care for the world’s poor, notably Haitians. The men are roughly contemporaries, both have won MacArthur grants, both have a Christian bent and Harvard connections, Stevenson even quotes Farmer — who, it turns out, sits on the board of the Equal Justice Initiative. Farmer’s commitment to the poor was captured in Tracy Kidder’s “Mountains Beyond Mountains” (and Kidder’s advance praise adorns the back cover of “Just Mercy”).

A difference, and one that worried me at first, is that Farmer was fortunate enough to have Kidder as his Boswell, relieving him of the awkward task of extolling his own good deeds. Stevenson, writing his own book, walks a tricky line when it comes to showing how good can triumph in the world, without making himself look solely responsible.