Democracy Can Not Survive Without Education, Views Either For or Against

Democracy Can Not Survive Without Education, Express your views either for or against this statement. In a democracy which rests on the pillar of free people, one cannot survive without education. Education of its citizens takes predominance as the choices made by the people should be the outcome of a defined thought process, which cannot happen in a vacuum. Visit official website CISCE for detail information about ICSE Board Class-10

Democracy Can Not Survive Without Education, Views Either For or Against This Statement

For a healthy Democracy people should be educated but some time it has a dark face also . therefore there are two Face on question of Education in Democracy.

For The Statement

Every citizen from the richest to the poorest should receive education for the benefit of the society and the various interests of the society that need to be catered too. Citizens should be able to read and understand what is going on in the world and learn to keep their part in it and contribute towards democracy.

The Education needs to start right from a person’s childhood because if he is untaught, his ignorance and vices would cost us dearly, creating a need to correct them later on in life. On the other hand, if children are educated, they would imbibe virtue and values that would enable them to contribute as responsible citizens to the democracy.

Education should not just stop at the common man, but should also reach out for the training of able counselors so that they can administer the affairs of the country in all matters that include legislative, executive and judiciary. For a democracy to be alive, it needs people with truth and integrity in all the departments and that is possible only through education and by which a country can be led to prosperity, happiness, and power. Hence It is true that education is the backbone for any democracy to function well and all citizens must be educated.

Against The Statement

The common man, for example, might not be interested in the functioning and running of the governments and its departments such as the judicial, executive and legislative. He would probably be more concerned with fulfilling his immediate needs and relax, once his goal has been reached. He is not worried about the everyday happenings of a democracy.

To create a just society, the society can be under the control of the most cultivated and best-informed minds and ‘lovers of wisdom,’ according to Plato. There is truth to this as a healthy and just person is governed by knowledge and reason.

Most often, it is the ignorance of the common, which hinders their involvement in the processes of democracy, for they choose to be so. In such a case, it is not the educated and enlightened ones who mislead people. It is the lackadaisical or apathetic response to the democratic process. Therefore, it can be said that education of all citizens is not required for democracy to survive.

—: End of Democracy Can Not Survive Without Education, Views Either For or Against :–

Return to : ICSE Specimen Paper 2023 Solved

–: visit also :–

- ICSE Class-10 Textbook Solutions Syllabus Solved Paper Notes

- School will be closed on These Dates in August, Check Total Holidays

- High Salary Top Courses After 12th Science for Boys / Girls

- Which School Board is Better for IIT JEE and NEET Preparation?

- Which Entrance Exam Is Easier To Crack – NEET, IIT, JEE?.

- CISCE 2023 Exam: Clue of Board Paper Standard

- ICSE Board Paper Class-10 Solved Previous Year Question

Tithonus Short Answer: ISC Class-12 Poem Rhapsody Workbook Solutions

Tithonus Logic Based Questions: ISC Class 12 Poem Rhapsody Workbook Solutions

Tithonus MCQs: ISC Rhapsody Workbook Solutions Class 12 English

2 thoughts on “Democracy Can Not Survive Without Education, Views Either For or Against”

It was really very informative and interesting to read the solved topics. It would be very helpful if this trend continues.

we will try

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

The Role of Education in Democracy

- Posted October 8, 2020

- By Jill Anderson

Many people question the state of democracy in America. This is especially true of young people, who no longer share the same interest in democracy as the generations before them. Professor Danielle Allen , director of the Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics, has long studied what citizens need in order to succeed in democracy and how our social studies and civics education have impacted democracy.

"We have really disinvested in civic education and social studies. You can see that now in the comparison that we currently spend $54 per year per kid of federal dollars on STEM education and only 5 cents per year per kid on civics,” Allen says. “We have really ceased to lay the foundation in K–12 for young people to understand democracy, be motivated to participate in it, to have the skills and tools they need to participate effectively, and as a result, enjoy participation."

In this episode, Allen discusses how we got where we are today and what it will take to reinvest in education for democracy.

- Find ways to tell “an integrated version of U.S. history that is simultaneously honest about the crimes and wrongs of the past, but without falling into cynicism,” Allen says.

- When broaching a challenging topic in the classroom, begin from a place of inquiry. Try not to start with the instructional content or even understanding the issue, but let students think about what comes to mind about the issue and record their feelings and how they connect to it. “I think it’s really important that teachers be able to see what the starting points are – both analytically and emotionally that students have for engaging with these issues,” she says.

- To raise engaged citizens, Allen suggests bringing democratic practices of reason giving into the life of a family. “There are lots of lessons inside a family that can feed in to help the understanding of democratic practice,” Allen says.

I'm Jill Anderson. This is the Harvard EdCast. Harvard's Danielle Allen knows young people aren't as invested in democracy like the generations before them. Today, fewer than 30% under age 40 even consider it important to live in a democracy. Allen is a political theorist who's long studied what citizens need in order for democracy to succeed.

Education plays a big part in how we think about democracy, yet America's classrooms haven't always emphasized these subjects. With the presidential election just weeks away, I wanted to understand how education can preserve democracy and whether tensions rising in America signal a change underway.

Danielle Allen: In another moment of crisis in the country, The Cold War, the country really turned to science and technology to meet the moment. So there's the period during World War II, the Manhattan Project, for example, which really brought universities into the project of supporting national security with the pursuit of the atom bomb. That was a point in time, it was really the beginning of decades long investment in STEM education. That was important.

We needed to do that, but at the same time, over that same 50 year period, we have really disinvested in civic education and social studies. You can see that now in the comparison that we currently spend $54 per year per kid of federal dollars on STEM education and only 5 cents per year per kid on civics. So we have really ceased to lay the foundation in K–12 for young people to understand democracy, be motivated to participate in it, to have the skills and tools they need to participate effectively and as a result, enjoy participation.

Jill Anderson: We're also living in a time when teaching history is being really politicized and I'm wondering how you think we can effectively teach history and democracy to young people.

Danielle Allen: I've been really privileged over the last 15 months or so to be a part of a cross-institutional network under the banners and they call it the Educating for American Democracy Project and my center Harvard, the ethics centers participating. Jane Kamensky, who directs the Schlesinger Library for Women as a PI Tufts, Arizona state university and this group has pulled together a network of hundreds of scholars across the country with the goal of developing a blueprint, a roadmap for the integration of history and civics education K–12.

The reason I'm going through all of that is because at an early point in our work, directly thinking about the issue you just raised or polarization of our national history and polarization of education around civics, we decided that we were going to do two things on our roadmap.

One was to really structure it around inquiry to really focus on the kinds of questions that should be asked over the span of K–12 more so than on the answers and also that we would really focus on design challenges. That instead of seeing the disagreement about how to narrate our nation's history as a kind of end of the conversation, we would see it as the beginning of a conversation. So for instance, one of the design challenges we put to educators is that we have to find a way to tell an integrated version of US history that is simultaneously honest about the crimes and wrongs of the past, but without falling into cynicism and also appreciative in appropriate ways of the founding era without tipping into gamification.

So what we try to do is to say, "This is a design challenge. We don't know exactly what the answer is to meriting a history in this way that integrates clear-eyed view of the problems as well as a clear-eyed view of the goods and the potentialities, but we believe it can be done and we believe that this big country with so many committed educators is a place where we can experiment our way into solutions."

Jill Anderson: Right. One of the things I think is interesting as you look at the polls and voter turnout, and you often see young people not being as engaged, but when you look at some of the protests that have been happening around the country, it seems to be largely younger people. Is that a shift happening in our democracy where young people are maybe becoming more engaged?

Danielle Allen: It's certainly the case that young people are showing engagement through their participation in social movements and protests. In that regard, the moment is a lot like the 1960s with similar levels of engagement from young people. The question is whether or not young people who engage in the democracy tool of a social movement or of a protest can also understand themselves to have access to the tool of using political institutions. So social movements are an important part of the democracy toolkit, but they're just a part.

So it's really a question of whether or not young people see value in political institutions too, and can knit these things together. To some extent, I think that actually we really need to do work to redesign, even for example, our electoral system. So when we look around and we see that lots of people are disaffected or alienated or feel disempowered, that doesn't just mean that they're sort of haven't got enough education or don't have the right perspective.

It also means that our institutions aren't delivering what they promise. They're not responsive. They don't generally empower ordinary people and they very often don't deliver sort of equal representation. So in that regard, everybody, all citizens, civic participants have a job to do to think about redesigning our institutions so that they achieve those things.

On that front. I was again, fortunate to participate with a huge network of people through the American Academy Of Arts And Sciences, a commission on the future of the of practice of democratic citizenship and we released a report in June the 31 recommendations, a chunk of which are about redesigning our electoral system to deliver that responsive, empowering form of government that also provides equal representation.

Jill Anderson: Do you think something like this pandemic could be a tipping point because so much has moved online and I'm wondering how you think that might change civic action in education?

Danielle Allen: Well, the pandemic without any question is a huge exogenous shock, as we would say in social sciences, that it's a transformative event. Period. The magnitude is so significant. I think we're a very long way from being able to see and understand all of its impacts and consequences. For me personally, one of the things it has driven home is the weaknesses in our practices of governance. These weaknesses are partly institutional and partly cultural. Our polarization is one of the significant causes of our failure to come to grips with the current crisis. So I think for lots of people, the pandemic is really bringing our vulnerabilities to the surface. Also, for example, the disparate impacts across racial and ethnic groups of the disease and the underlying disparities in health equity has really come to the fore to visibility. So I think a lot of people are really focused in a more intensive way than in the past on addressing those problems.

I always sort of have a lot of confidence in the kind of creative energies of human beings when they really sort of see and face problems. So I believe that the moment does give us an opportunity to transform our conception of what we want for our society, what it means to name the public good, what it means to invest in the public good and my hope is that we'll be able to pull energy around a concept of the public good with us in the coming years.

Jill Anderson: We have this huge election coming up and the pandemic has somewhat overshadowed the election a little bit. I look at parents and their children and wonder are there things that parents could be doing at home to help raise their children to be more engaged and value democracy?

Danielle Allen: Well, I think there are a number of things. I mean, I actually think it matters to bring democratic practices of reason giving for example, into the life of a family. That can be very hard. Family structures are often and for very good reason, very hierarchical. So within the sort of context of hierarchical family structures, how can parents foster reason giving, hear their children's reasons for things, help their children understand what it means to engage in the back and forth around reasons, help them understand what it means for one person to lose out in one decision-making moment, but then to win out in another moment and nonetheless, even though we sort of exchange sacrifices for one another over the course of collective decision-making, our commitment to our social bond is so strong that that makes that sort of exchange of burdens tolerable. So I think there are lots of lessons inside a family that can feed into help the understanding of democratic practice.

Jill Anderson: One last final question would be if you have any thoughts or advice to share with the teachers out there who are working hard, and many of them working remotely to try to teach lessons about the upcoming election and all the things happening in the world.

Danielle Allen: So teachers really always have a hard job, and it's so hard now between the remote learning and the intensity of the external environment, the political questions and the debates and so forth. I think it's really important to remember that different students will bring different kinds of perspectives and exposures with them into the classroom. So I think when a teacher is trying to engage a hard topic, whether it's a hard element of history or a controversial issue in our contemporary debates, it's really important to start by bringing to the surface what's already in students' minds.

So maybe you use a Google doc, maybe you use a chat function, but when a topic comes up before sort of launching into the instructional content or the real digesting of the issue, just go ahead and let the students record the first thing that comes to mind for them when they hear the relevant issue and let them record the emotion that they connect to that issue. I think it's really important that teachers be able to see what the starting points are, both analytically and emotionally that students have for engaging with these [inaudible 00:10:35] issues.

Jill Anderson: Well, I want to thank you so much for taking the time and talking and sharing your thoughts today.

Danielle Allen: Thank you, Jill. Appreciate your interest.

Jill Anderson: Danielle Allen is the director of the Edmond J. Safra Center For Ethics at Harvard. She's a professor at the Harvard graduate school of education and faculty of arts and sciences. She leads the Democratic Knowledge Project, which focuses on how to strengthen and build that knowledge that democratic citizens need to operate their democracy. I'm Jill Anderson. This is the Harvard EdCast produced by the Harvard graduate school of education. Thanks for listening.

An education podcast that keeps the focus simple: what makes a difference for learners, educators, parents, and communities

Related Articles

Propaganda Education for a Digital Age

Love, Hope, and Education

Books, Movies, and Civic Engagement

Let’s educate tomorrow’s voters: Democracy depends on it

Subscribe to the center for universal education bulletin, elias blinkoff , elias blinkoff research scientist in the department of psychology and neuroscience - temple university @blinkoffe molly scott , and molly scott research scientist - temple university @mscott6399 kathy hirsh-pasek kathy hirsh-pasek senior fellow - global economy and development , center for universal education @kathyandro1.

November 21, 2022

The final results of the 2022 midterm election in the United States are in. Journalists tell us that a key issue for voters was preservation of democracy . A recent NPR/PBS NewsHour /Marist poll showed that while inflation was the top issue on voters’ minds, “preserving democracy” captured second place. The issue that claimed little attention was education . Yet, as Thomas Jefferson once said, “An educated citizenry is a vital requisite for our survival as a free people.” That is, if we care about democracy, we must also care about education.

Only $ 10 million were spent on education ads by both parties between Labor Day and late October 2022, compared to $103 million spent on abortion ads by Democrats and $89 million spent on tax ads by Republicans. When education was discussed, political scientist Sarah Hill suggests that the topic was narrowly construed around culture war issues, including parental rights and ideologically-driven curriculum changes like banning books .

Sadly, conversation about education was limited in the most recent American election. We desperately need to ignite this discussion.

Given the lack of discussion around education, it is fair to repeat the claim made in 1983 that our nation is at risk . Now more than ever, the populous is required to sift truth from fiction among the many hyperbolic claims made by politicians on both sides. Without strong critical thinking skills, it is nearly impossible to manage the amount of content that people encounter every day and to form cogent opinions—be it on issues like health care, inflation, or climate change.

We are failing the next generation of citizens. Our recent Brookings blog on the latest National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) scores makes this point. It showed how students’ levels of proficiency in reading and math were already relatively low pre-pandemic, with the important qualifications that NAEP proficiency is not equivalent to grade level proficiency and a high academic standard to achieve. In fact, proficiency on the NAEP requires a deeper understanding of reading and math skills, including the application of critical thinking in relation to subject area content. And many reports suggest that even reaching proficiency (as defining success through the lens of just reading and writing) will not be enough to achieve Jefferson’s vision. Children need to learn a breadth of skills that includes—but goes beyond—content, to go from classroom to career success.

Our recent discussion of education facilitated by Brookings on November 9 following the launch of our book, “ Making Schools Work: Bringing the Science of Learning to Joyful Classroom Practice, ” explored a comprehensive, but flexible, framework for how to educate children with a breadth of skills—how to educate children to be caring, thinking, and creative citizens for tomorrow. Born from research in the science of learning , we suggest that we must teach in the way that human brains learn through an active (not passive) pedagogy that is engaging rather than distracting, meaningful with clear connections to prior lessons and students’ out-of-school experiences, socially interactive instead of entirely solo, iterative with room for experimentation and trial and error, and joyful rather than dull and repetitive. This is the antithesis of what is going on in many schools across the globe that were fashioned for a bygone era. If we do embrace a more modern educational model, students can be strong across the skills required to navigate school, work and society: collaboration , communication, content , critical thinking , creative innovation , and confidence (the ability to persist even after a failure and to know that you can grow with experience) .

Sadly, conversation about education was limited in the most recent American election. We desperately need to ignite this discussion. If our graduates are to outsmart the robots, to be viable for the job market, and to be discerning voters and citizens, education must literally be on the ballot. Yes, a major issue for voters this year was the precarious nature of our democracy. Our democracy, however, cannot survive if we do not educate our citizens. As The Atlantic proclaimed, “ Democracy was on the Ballot and Won .” If it is to keep winning, we must discuss education reform. Our science of learning can lead the way. It is imperative that children learn a breadth of skills that they can carry with them into the voting booth.

Related Content

Online only

10:00 am - 11:00 am EST

Rebecca Winthrop

June 4, 2020

Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, Jennifer M. Zosh, Roberta Michnick Golinkoff, Elias Blinkoff, Molly Scott

November 8, 2022

Early Childhood Education K-12 Education

Global Economy and Development

Center for Universal Education

Annelies Goger, Katherine Caves, Hollis Salway

May 16, 2024

Sofoklis Goulas, Isabelle Pula

Melissa Kay Diliberti, Elizabeth D. Steiner, Ashley Woo

Your Article Library

Relationship between democracy and education.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This article provides an essay on the intimate relationship between democracy and education.

Subject Matter:

It is an admitted fact that there is an intimate relationship between democracy and education. In a democracy, education is given primacy, for it is pre-requisite for the survival and success of the former. Similarly, education fosters a democratic temper in the minds of people.

Democratic values like liberty, equality, fraternity justice, dignity of individual, co-operation, sharing of responsibility etc. are applied to education to make it more effective, meaningful, relevant and useful.

Democracy in order to be a reality and a way of life has to be introduced from the very beginning of education and its values need to be practiced in educational institutions. Before a thorough discussion on the inalienable relationship between the two-democracy and education, it is essential to unfold the meaning of democracy.

Democracy is a form of government in which there prevails the rule of majority. It is government of the people, by the people and for the people. This is a political connotation of the term democracy. Economically, it is a system where no one is exploited, where everybody is assured a fair standard of living, where there is equal opportunity for work according to abilities and capacities, where economic organization is based on collective or co-operative basis and where economic projects are geared for the benefit of the community at large but not for any private bodies.

Socially, it connotes absence of all distractions based on class, caste, creed, birth, religion, language or possession of money. Everyone is guaranteed fundamental rights, and equality of opportunities is given for the fullest development of personality.

Thus, it is social justice which is central to the understanding of democracy. Dignity of individual is accorded a primacy in it. In other words, there exists a paramount faith in the worth of the common man. There is no domination of any individual or group over another.

There prevails a sense of co-operation, fellow-felineness, fraternity, liberty, responsibility, understanding and justice. Therefore, democracy has been construed as a way of life, a way of doing things and a way of seeing and knowing. John Dewey says, “A democracy is more than a form of government, it is primarily a mode of associated living, of conjoint communicated experiences”.

Democracy is a way of life where problems are solved through argument, discussion, deliberation, persuasion and transaction of views instead of dictation, coercion, violence, distrust and conflict. It is an order of social relationships among individuals dedicated to the promotion of the individual’s well being keeping personal interests in abeyance.

It is an order in which every individual gets limitless opportunities to blossom according to his/her potentialities and in which power and responsibilities are shared on a mutual basis without any confrontation and conflict.

According to Prof. Seeley, “Democracy is a form of government in which everyone has a share.” Therefore in the business of government everybody is equally an actor or player. The will of people is well recognized and given primacy.

Educational Implications :

There is an inseparable connection between democracy and education. Democracy cannot be thought of in segregation from the spectrum of education. It has been admitted on all hands that the sinew of democracy depends upon the character and intelligence of all its citizens.

John Dewey, the votary of democratic education spells out succinctly, “The devotion of democracy to education is a familiar fact. A government resting upon popular suffrage cannot be successful unless those who govern and obey their governors are educated”.

Further, Bernard Shaw mentions the value of education in a democracy. “Democracy implies election of the corrupt few by the ignorant many. Therefore, education is the major means to enrich the strengths and overcome the weaknesses of the people. It is also a means for the widespread diffusion of democratic values”. Radhakrishnan commission (1948-49) said, “Education is the great instrument of social emancipation, by which democracy establishes, maintains and protects the spirit of equality among its members”.

It is crystal clear that democracy can function properly only if all its citizens are properly educated. Democracy should provide aims to education and thus, principles of democracy should reflect in the aims, curriculum, methods of teaching, administration and organisation, discipline, the school, the teacher etc.

Aims in Democratic Education :

Education in a democracy is meant not for a microscopic minority but for a macroscopic majority. It should be broad-based embracing all the ingredients of philosophy, psychology, sociology, biology etc.

The main aim of education in a democracy is to produce democratic citizens who can not only understand objectively the plethora of social, political, economic and cultural problems but also form their own independent judgement on these complicated problems.

It must inculcate in them the spirit of tolerance and ignite the courage of convictions. It must aim at creating in them a passion for social justice and social service. It must equip in them with the power of judgement, scientific thinking and weighing the right and the wrong.

Education aims at enabling the pupils to be social minded human beings capable of managing their own affairs and living with others adequately. It enables them to realize their hidden potentialities fully, for a fully developed person can contribute his/her bit to the success of democracy.

Prof. K.G. Saiyidain viewed that education must be so oriented that it will develop the basic qualities of character which are essential for the functioning of democratic life. These qualities are passion for social justice a quickening of social conscience, tolerance of intellectual and cultural differences in others, a systematic of the critical intelligence in students, cultivation of a love for work and a deep love for the country.

The Secondary Education Commission (1952-53) have spelt out the following aims of democratic education:

(i) Democratic Citizenship:

In orders to foster democratic citizenship, education should aim at the following:

(a) Clear Thinking:

Education should aim at developing capacity for clear thinking which entails power of discrimination of truth from falsehood.

(b) Clearness in Speech and Writing:

It is needed for free discussion, persuasion and better exchange of ideas among people.

(c) Art of Living with the Community:

Education should aim at nourishing the art of living with the community which requires the qualities like discipline, co-operation, social sensitiveness and tolerance.

(d) Sense of True Patriotism:

It takes three things which are:

(i) A sincere appreciation of the social and cultural achievements of one’s country,

(ii) a readiness to recognize its weaknesses frankly,

(iii) a resolve to serve it to the best of one’s ability and

(iv) to subordinate one’s interests to the broader national interests.

(e) Development of Sense of World Citizenship :

Education seeks to develop in children a sense of universal brotherhood of man and develops an awareness in them that they are not the citizen of one’s own country rather citizens of the world. All are members of a global world just like one family.

(ii) Improvement of Vocational Efficiency :

The second aim of our educational system is the improvement of vocational efficiency which includes creation of right attitude to work, promotion of technical skills and efficiency.

(iii) Development of Personality :

The third aim is the development of personality which includes discovering of hidden talents, cultivating rich interests in art, literature and culture necessary for self-expression and assigning a place of honour to the subjects like art, craft, music, dance and hobbies in the curriculum.

(iv) Training in Leadership:

A democracy cannot run smoothly without efficient and effective leadership. Therefore, it is one of the important aims of democratic education that it should train an army of people who will be able to assume the responsibility of leadership in social, political, economic, industrial or cultural fields. Besides, they are required to acquire skills in the art of leading and following others and to discharge their duties efficiently.

The National Education Association, U.S.A. (1977) has stated the following four groups as the main purposes of education:

(i) The Objectives of Self-realization:

Obtaining an inquisitive mind, ability in speech, reading, writing, arithmetic, seeing and hearing, acquiring the necessary knowledge regarding good health, formation of healthy habits, acquiring healthy means of recreation, utilization of leisure-hours, developing aesthetic interest and character.

(ii) Objectives of Human Relationships :

Respect for humanity, friendship, co-operation, courtesy, polite behaviour, appreciation of family life, skill in family management and establishing democratic relationship in family.

(iii) Objectives of Economic Efficiency:

Acquiring skill in chosen occupations, knowledge on different occupations, choice of one’s own vocation of life, maintaining one’s vocational skill occupational efficiency, occupational adjustment, maintaining one’s economic system of life properly etc.

(iv) Objectives of Civic Responsibility :

Understanding various social processes, to be tolerant, performing duties of a citizen, faith in social justice and democratic principles, abiding of law making correct judgement, development of world citizenship etc.

Curriculum :

Since democratic education absolutely favours maximum individual development, curriculum in a democracy should be flexible so that it can cater to the diverse tastes and temperaments, aptitudes and abilities, needs and interests of the pupils.

It seeks to stimulate thought and creative abilities of children. It should be broad-based which includes totality of experiences that a pupil receives through manifold activities undertaken inside the school and beyond it.

Further, it is essential that democratic curriculum should take into account the local conditions and environmental demands. Social element is greatly emphasised in it. In other words, curriculum should be tempered with social outlook and temper. There should be a provision for including vocational skills in democratic curriculum. Above all, curriculum should be constructed on the basis of the principle of integration.

It should not be separated into fragmented parts. It should be differentiated at a later stage to suit to the diverse interests, attitudes, aptitudes and abilities of the pupils. Moreover, it should be flexible and dynamic to suit to the changing reeds and times.

Different subjects are prescribed for democratic curriculum which is as under:

(i) Natural Sciences as physics, chemistry and biology for clear understanding of physical environment.

(ii) Social sciences as history, political science, civics, geography, economics, sociology, anthropology etc. for understanding society, social forces and social milieu.

(iii) Study of art, language, ethics, philosophy, religion for training the emotions of pupils and acquainting them with the aims, ideals and values of human life.

(iv) Vocational subject including craft to enable children to be self-reliant by becoming vocationally efficient.

Besides, hygiene, agriculture, mother tongue, native industries, practical mathematics and other languages should find a niche in the democratic curriculum.

Methods of Teaching :

Since democratic education de-emphasizes excessive mechanization and indoctrination. It encourages pupil’s participation in teaching learning process. It provides ample scope to think and reflect.

Therefore, democratic trend gives rise to a host of modern and dynamic methods of teaching such as learning by doing, heuristic, the laboratory and experimental method, project method, Dalton plan, Montessori method, socialized techniques, seminars, symposiums, discussions, problem solving, group work etc.

In the above techniques, emphasis is given on pupil’s active participation, initiative, enquiry, interests, judgement power and independent thinking. Teacher no longer instructs; he guides, directs and encourages pupils to explore the vast repertoire of knowledge in the deep sea of education.

Discipline in Democracy :

Democracy ensures discipline through co-operative activities of children. Problem of discipline does not arise in a democratic school. True discipline docs not consist in trite phrases like sit still, keep quiet and do as you are told; rather it consists in the control by the rational self. It is self-discipline or spontaneous discipline which comes out of the child’s involvement in different activities.

It is not external, rather internal, inner and thus self-imposed. It is a discipline from within and is based on the pillars of love, sympathy, co-operation and human relationship. Self discipline is the essence or core of democratic living. Discipline in democratic education is based on the conviction of doing right thing in the right manner and at the right moment.

There are a number of self-governing units in the institution such as students’ union, students’ committees, students’ councils, parliament etc. which ensure participation of children and help them realise the need of obeying rules. Moreover, they feel that they are members of different societies of the school and think that the rules they have to follow are their own and are made for their own benefits.

This feeling leads them to accept the school discipline gladly without any resentment. This is truly self- discipline in a free environment which is the essence of democracy. Conscience plays a role in the emergence of true discipline.

Role of Teacher in a Democracy :

Success of a democracy depends largely on the teacher—his/her outlook, attitude and way of life. He has to manipulate the environment and make use of all opportunities to enrich and experience of the pupils and to ensure their all-round development of personality. He/she is not a dictator or autocrat, but a friend, philosopher, stage-setter, guide and a vigilant supervisor. He/she does not interfere but co-operate.

He/she provides ample freedom, love and sympathy to pupils. He/she is objective—free from any form of prejudices and favouritism. He/she maintains a co-ordial relation with the community. Lastly, he/she practices democratic principles in his own life.

Therefore, in a democratic system, the teacher occupies an important place as he/she is the best medium for spreading democratic feelings and ideas in the school and society. He is an agent of change and a facilitator of democratic culture in the school.

School Administration and Management in a Democracy :

In democratic school administration and management teachers should be given ample freedom in framing or planning the policy of the school, in organizing activities, in preparing curriculum, in selecting methods of teaching, in conducting research and in making innovations in teaching and education. There prevails a co-ordial relationship between the teachers and taught and between the teachers and administrators.

If there happens a tug of war between the administrator and teacher, it mars the conducive atmosphere of the institution. As such, co-operative spirit raises the morale of an institution. It is desirable that democratic administration should eschew extreme concentration of power, the unshared responsibility, regimentation of authority and unrestrained freedom.

Teacher’s contribution is highly praised in democratic education. The entire atmosphere of school is thrilled with scent of democratic principles. Ultimately, this situation helps the growth of individuality of its stake-holders—students.

Role of School :

School should litter with democratic principles. It is the democratic environment which is congenial for the full-flowering of human personality. The school should provide full scale freedom to all pupils to grow under the heavy weight of democracy. Equality of treatment and opportunity should be the rule of the institution. The school should help every individual pupil to be disciplined, creative and adaptable.

The school should act as a replica of community where democratic ideals are not only taught theoretically but are practically done through its multifarious activities. Ross aptly says, “Schools ought to stress the duties and responsibilities of individual citizens. They ought to train pupils in a spirit of cheerful willing and effective service. They should teach citizenship directly. Everywhere there should be a spirit of team work. School is a prepared environment in which child may best blossom”.

Related Articles:

- Curriculum Construction in India | Education

- Culture and Education

Comments are closed.

Education and Democracy

- Martha Minow

Anna Deavere Smith, American actress, playwright, and professor, once said , “Art convenes. It is not just inspirational. It is aspirational. It pricks the walls of our compartmentalized minds, opens our hearts and makes us brave.” In that spirit, can we “prick the walls of our compartmentalized minds” and bring heart and courage to reflections on education and democracy? Democratic governance in societies around the world faces serious challenge today. Education sits at the crossroads of the information revolution and widening inequalities. The frailties of education increase the fragility of democracy. Strengthening each is critical to the other.

What steps move toward strength, and what steps instead make matters worse?

Democracy is hard work, and often produces poor policies. Playwright George Bernard Shaw was not stretching the truth when he had one of his characters say , “Democracy substitutes election by the incompetent many for appointment by the corrupt few.” The work of self-governance takes time, produces conflicts, and leaves us with few to blame but ourselves. So, it “ is the worst form of Government except all those other[s]. ”

On top of it all, it’s difficult to keep a democracy. Elections can be rigged. Politicians can take choices away from the voters. And the people can be tempted to surrender their power — by failing to vote or by voting for tyrants. Only 4.5% of the world’s populations live in full democracies, and even in those nations, self-governance faces rising gains by authoritarian leaders in Venezuela, Poland, Hungary, the Philippines, and, some would say , the United States.

The founders of the United States understood that “ an ignorant people cannot remain a free people and that democracy cannot survive too much ignorance. ” The American movement for “common schools” initiated in the 1830s sought to promote political stability, equip more people to earn a living, and enable people to follow the law and transcend differences in religion and background. Yet we are far from embracing this ideal as a guide for practice in the United States. As initially advanced, the common school ideal excluded enslaved people and children with disabilities. After the Civil War — and even today — public school systems still often divide students by race and class in practice.

A sustained legal strategy attacking legally mandated racial segregation in schools yielded official victory in 1954. But this also triggered resistance, and, despite some successes, massive racial separation persists in American schools. According to work done by Jennifer L. Hochschild and Nathan Scovronick , of this country’s 5,300 communities with fewer than 100,000 people, at least ninety percent were white at the turn of this century. In large urban districts, nearly seventy percent of the public students were nonwhite, and over half were poor or nearly poor. In some communities , this pattern has continued to worsen. Disparities in per-pupil expenditures further reflect the sharp differences in local wealth because most of the country funds schools based on local property taxes. Although a majority of Americans report that school integration is a good idea, a majority also agree that “ we shouldn’t do anything to promote [it] .” One commentator reports that now we live in an era of “hoarding” by upper middle-class families — those in the top twenty percent of income — who have used zoning laws, local control of schooling, college application procedures, and unpaid internships to pass their opportunities onto their children while making it harder for others to break in.

As a result, it is fair to ask whether we are holding up the ideal, so well stated by John Dewey , that schools should “see to it that each individual gets an opportunity to escape from the limitations of the social group in which he was born, and to come into living contact with a broader environment”? Controversial policy reforms would increase educational opportunities for disadvantaged students, but there is little political will for paying teachers more to teach in schools in poor neighborhoods, making higher education truly affordable, ending exclusionary residential zoning, and replacing reliance on local property taxes with state-wide or national redistributive financing.

To work, democracy needs effective schools that do even more than instruct students in the value and institutions of a democratic society (though this would be a good start, given that in 2014 only 36% of Americans could name the three branches of government ). Schools can cultivate habits and skills of taking initiative, showing respect, listening, and controlling emotions in the face of disagreement. Schools can help individuals take the perspective of others and learn to assess and organize information. These capacities are presumed by democratic governance, but children are not born with these abilities. Nor are they born with knowledge of what life is like under fascism or autocracies. Students can learn by doing: learn to use the tools of democracy in their classrooms, debate controversial issues, and practice disagreeing with respect. Schools can trust young people to follow their own interests, to take responsibility, and to take up governance of their own classrooms and lives. Civics education with these features leads to greater political engagement, voting , and higher degrees of acceptance toward people of different backgrounds .

At this moment, the distance between these ideals and aspirations much less actual practices around the country is enormous. A global study found that few millennials object to autocracy; only 19% of American millennials surveyed report that a military takeover would be illegitimate if the government is incompetent. Not many young people may know how following a worldwide economic depression, people in Italy and Germany turned to fascism in the 1930s and gave power to Mussolini and to Hitler . Mussolini and Hitler appealed to racism, fanaticism, and fear — and created global violence, mass killings, and destruction of communities and democratic ideals. A ray of hope for democracy: survey research suggests that people are much more willing to deliberate than prior research suggested, and those most willing to deliberate are exactly those turned off by standard, polarized, interest group politics. If the conventional avenues for participation can involve more opportunities for deliberation, many who are disengaged and disaffected might join in the work of self-governance.

Digital resources offer both promise and risks for education, for democracy, and for their connections. The Internet, social media, and search engines bring much of the world’s knowledge within reach of more people than ever in human history. Information — and disinformation — are plentiful and a few keystrokes away. It is more difficult for repressive regimes to keep information out of people’s reach. The architecture of the Internet also enables people with little cost to find others with similar interests, to share and spread information and views, and to recruit others because it facilitates one-to-many communication . These features are exemplified by the work of MoveOn and Breitbart News — and also by terrorist recruitment and sexual predators online. Arab Spring and public protests in Turkey indicate the power of the Internet to promote democracy but authoritarian governments have also found the Internet useful for surveillance, intimidation, and purging opposition . Research suggests that some individuals tune out of politics with the help of social media and internet entertainment , but here the internet simply joins many opportunities for people to avoid political engagement. Both education and democracy are fragile unless people desire — and fight for — political participation, knowledge, debate, critical reasoning, and freedom, whether in governance of their societies, schools, or design of the Internet.

Education and democracy both enhance human freedom but require rules and structure to work. Both need ground rules. Neither can work amid untrammeled violence, disrespect, and lying. Formal rules and informal norms can guide people to assess claims and bolster intolerance of intolerance. Practicing the predicates of education and democracy — the norms of respect and truth — these are the tasks pricking the walls of our compartmentalized minds, opening our hearts, and making us brave.

This post is based on remarks given at Sarah Lawrence College.

More from the Blog

Community financial services and the intramural debate over novelty and tradition.

- Thomas E. Nielsen

On the Limits of ADA Inclusion for Trans People

- A.D. Sean Lewis

Response To:

- Bending Gender: Disability Justice, Abolitionist Queer Theory, and ADA Claims for Gender Dysphoria by D Dangaran

Civil Suits by Parents Against Family Policing Agencies

- Alexa Richardson

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 14 November 2017

‘Democracy’ in education: an omnipresent yet distanced ‘other’

- Ashley Simpson 1 &

- Fred Dervin 1

Palgrave Communications volume 3 , Article number: 24 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

4208 Accesses

4 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Language and linguistics

A Correction to this article was published on 12 December 2017

This article has been updated

Like many concepts and notions used in various subfields of education, the idea of democracy is both floating and polysemic. It can also be a conveniently loose term that can be used by some to position themselves above others and to ‘teach them’ lessons about how to ‘do’ democracy, often creating unjustified hierarchies and moralistic judgements. Based on Mikhail Bakhtin’s concepts of 'authoritative discourse and internally persuasive discourse', this article examines how the contested idea of democracy is constructed and negotiated at a key International Conference on democratic education. Excerpts from talks given at the conference serve as case studies in this paper, without the intention to generalise about discourses of democracy in education. The results hint at uncritical attempts, often based on pathos, to totalise and generalise ‘democracy/the democratic’ especially within discourses on ‘democratic schools’. Such discourses can contribute to cultural othering and stereotyping, as well as, simplistic assumptions about how ‘democracy’ functions and comes-into-being. They can also help the utterer hide their sentiments. Thus, the aim of this paper is to deconstruct an essentialised and somewhat empty vision of democracy discourse in education. The fact that the idea of ‘freedom’ is often used as a synonym for ‘democracy’ during the conference is also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Developing social and civic competence in secondary education through the implementation and evaluation of teaching units and educational environments

Interpreting public policy dilemmas: discourse analytical insights

The politics of higher education: the European Higher Education Area through the eyes of its stakeholders in France and Italy

Introduction: democracy and heteroglossia.

Note that all excerpts within the chapter are verbatim, without any attempt to correct them.

‘Democracy’ and ‘education’ are always seemingly joined by the connective ‘and’—to refer to John Dewey’s ( 1916 ) publication ‘Democracy and Education’. Scholars, policy-makers, politicians and educators often assume the word ‘democracy’ follows ‘education’, and/or vice versa. However, consideration needs to be played to the wider social, political and linguistic interrelationships of how ‘democracy’ and ‘education’ are understood and how ‘democracy-comes-into-being’ in the specific context of education (Joas, 2000 ; Howlett, 2013 ).

Apple ( 2014 ), like many other commentators (e.g., Ball, 2007 , 2009 ), drawing on the neoliberalisation of education systems, notes how increased privatisation, competition, marketization, combined with ‘standards-driven’ procedures and measures have become ingrained within educational policies throughout the world. Apple ( 2011 , 2014 ) observes how schools, pupils, educational policies, and, knowledge have become ‘commodified’. He also argues that the forces of neoliberalism manifest through processes of disarticulation and misarticulation whereby hierarchised and hegemonic metadiscourses function ideologically in distorting meanings and representations (ibid). In this sense, words such as ‘democracy’ and ‘justice’ are constantly refracted by discursive, social, and ideological forces which shift how ‘democracy’ and ‘justice’ are continually represented and understood (ibid).

The forces of neoliberalism in education have resulted in perceptions of educational choice such as in ‘free schools’, ‘academies’, and other forms of decentralised schooling that have distorted perceptions of ‘public’ (state) and ‘private’ education (West, 2014 ; Hicks, 2015 ). At the same time, for instance, ‘democracy’ and ‘citizenship’ have become part of national curricula, teaching syllabi, teacher training resources and programmes, as well as, policy documents—seemingly, we are all ‘democratic citizens’ (Biesta, 2011 ). Simultaneously, the so-called ‘alternative education movement’ has positioned itself as an alternative to the neoliberalisation of education through, for instance, ‘democratic schools’ (Dundar, 2013 ; Korkmaz and Erden, 2014 ).

‘Democratic education’ and/or ‘democracy in education’ may encompass a number of ‘buzzwords’ and metadiscourses such as ‘multicultural education’ (Peters-Davis and Shultz, 2015 ), ‘intercultural education’ (Clark and Dervin, 2014 ) and ‘citizenship education’ (Biesta, 2015 ). As a result, some of the ‘meanings’ associated to, and generated within, ‘democratic education’ and ‘democratic schools’ can be somewhat ambiguous and contradictory (Woodin, 2014 ). As such, the multiple, varied and differing translations of ‘democratic values’ (such as equality and human rights) mean one must pay attention to the symbolic, representative and discursive functions of ‘democracy’ (Laclau, 2005 ).

Mikhail Bakhtin’s ( 1975 , 1981 ) concept of heteroglossia can be useful to examine these functions. Heteroglossia refers to the fact that one’s own utterances always contain ‘another’s speech in another’s language (Bakhtin, 1981 , p 324)—the other[s]-in-the-self are articulated through the discourses we utter. Heteroglossia can thus be understood as the constant refraction and metamorphoses of utterances within one’s speech (Bakhtin, 1981 ). Thus, one’s speech can never entirely be ‘one’s own’ (ibid). In this sense, heteroglossia can mark the negotiation of the self and other[s] through the refracted interplay and performativity of multiple and varied discourses (Schiffrin et al., 2010 ). It is through the constant interaction between and within discourses which can engender meanings that can condition others (Bakhtin, 1981 ). Bakhtin adds that ‘all utterances are heteroglot’ in that they function symbolically through indexing representations within discourse (Bakhtin, 1981 , p 428).

The interplay and performativity between sign-signifier-signified offers a way of understanding the representative and symbolic functions of discourses in engendering social meanings and identities (Hall, 1993 ). As Barthes explains, ‘the signified is the concept, the signifier is the acoustic image (which is mental) and the relation between the concept and the image is the sign (the word, for instance), which is a concreate entity’ (Barthes, 1972 , p 112). In this sense, the meanings of words (‘democracy’ in this paper) are not fixed in one singular or ‘objective’ way (Hall and Du Gay, 1996 ). It is important to note the influence discourse has on the constant instability and displacement of discursive concepts such as ‘democracy’, notwithstanding, the inherent antagonisms found within ‘democratic values’ (Mouffe, 2000 , 2009 ).

Two aspects of Bakhtin’s 'The speaking person in the novel' ( 1981 ), on which we focus in this article, is authoritative discourse and internally persuasive discourse. Authoritative discourse, as described in the (1981) English translation is described as discourses whose meanings have been fixed and allow no space for neither contestation nor interrogation (e.g., the authority of religious dogma) (Bakhtin, 1981 ). Authoritative discourse can function as a taboo as it ‘commands our unconditional allegiance’ (Bakhtin, 1981 , p 343). Taken from the glossary of the English version of the book, internally persuasive discourse is described as discourse, which is accentuated and reaccentuated by ‘one’s own’ gestures and accents within discourse (Bakhtin, 1981 ), though, Bakhtin’s concept of heteroglossia reminds us that both authoritative discourse and internally persuasive discourse are contained within the discourses of the self and others (ibid).

Many quotations/citations have focused on the ‘opposition’ of authoritative discourse and internally persuasive discourse (Skidmore, 2016 ). As Wardekker ( 2013 ) shows [an]other’s discourse is present in both authoritative and internally persuasive discourse—just because a discourse may be authoritative does not mean authoritative discourses are untouched by the forces of heteroglossia. We argue that Bakhtin himself would not agree with the idea that authoritative discourses and internally persuasive discourses are uttered and/or written in the form of a binary opposition. Discourses can be simultaneously authoritative and internally persuasive.

Basing our discussion of what we consider to be simultaneous aspects in Bakhtin’s work, authoritative discourse and internally persuasive discourse, we use excerpts and images taken from the International Democratic Education Conference (IDEC 2016). The annual conference (year of creation: 1993) brought together a number of different people, from academics and teachers, to activists and ‘gurus’ of the so-called ‘democratic education movement’. The discourses shared at the conference under review offer a rare insight into discourses frequently uttered in education about democracy in education and offer a lens to look into how utterances on ‘democratic schools’ and ‘democratic education’ manifest into deeper logics and meanings.

Discourses of democracy as a way of hiding sentiments

Our interpretation of Bakhtin’s concepts of authoritative discourse and internally persuasive discourse, is that discourse can simultaneously be authoritative and internally persuasive (Bakhtin, 1975 , 1981 ). In this sense, a discourse can be totalising and exert power over us (through reproducing customs, traditions, ignorance etc.), yet, be constituted by intersubjective manifestations and differences (such as differing intersectionalities of multiple identity markers) whose content is open to discursive argumentations and contestations (Bakhtin, 1975 , 1981 ). In a sense, discourses on ‘democracy/the democratic’ can hold a metadiscursive ideological grip over us whilst enabling to reconstruct differing possibilities. In this sense, ‘democracy’ contains inherent discursive antagonisms and contradictions whereby the sign of ‘democracy’ is susceptible to influences from the social heteroglot (Bakhtin, 1975 , 1981 ) (including; discourses/ power/ideologies) resulting in a constant metamorphoses of the sign whilst maintaining a symbolic signified (Barthes, 1972 ). As we shall see in the excerpt below, the multivoicedness of the speakers’ utterances, and of ‘democracy’, is illuminated to show potentially hidden sentiments which lie behind his/her utterances.

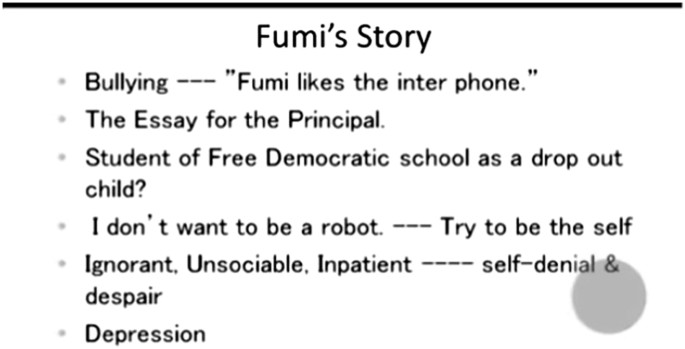

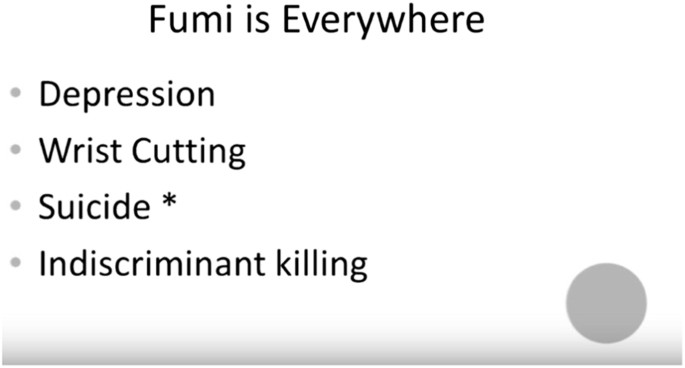

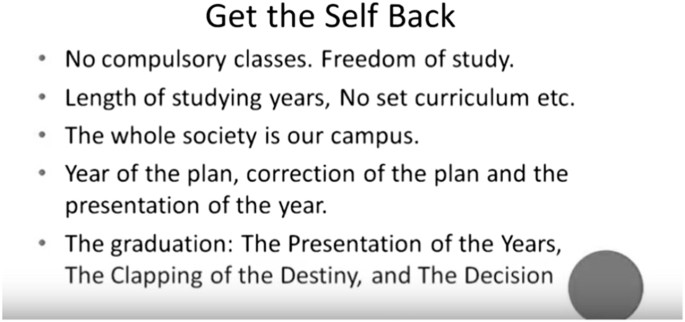

Excerpt 1 is taken from one of the keynote speeches at IDEC 2016. The speaker, reminiscing his time as a student, attended a ‘democratic school’ and has worked professionally in and with ‘democratic schools’ in the United Kingdom. In the excerpt he reflects with the audience on a basic issue: the potential embedment of democratic cultures in schools.

Excerpt 1. IDEC 2016 Keynote speech (i) ‘Shifting the future of education: can you embed democratic cultures in any school’?

For the purposes of this paper we only show the opening stages of the speakers’ presentation. The presentation lasted for 19 min and it was not necessary to transcribe all of the contents for our study.

So, can you embed democratic cultures in any school? That is the question. Can I just see a show of hands.

That’s the question. Who says ‘yes’?

[looks at the audience]

Can you embed democratic practices in any school?

[participants who agree with the statement raise their hands]

Yes. Do you think you can?

And who thinks no you can’t?

Interesting, so most people think maybe you can. I’m going to talk about that today. But I started thinking

when I sat down for the keynotes yesterday, okay, so if we are thinking about whether we can embed democratic

cultures in state schools and in in any school, can you do a keynote speech at an IDEC conference without a set of

powerpoint slides and without just talking the whole time. Because if you can’t do that you definitely cannot

Embed democratic cultures in any school. So I’m going to try it. And this is the test.

[Audience applaud]

We’ll see if it works [laughs] and partly it’s going to rely on you guys. So first, I just want to start thinking about

this. What, who …who in this room thinks that every child should have an access to education please stand

up now. Should every child have access to education?

[The audience participants stand up]

Okay. And if you think, and if you think that, that access to that education should be free can you give me that

you know, that international money symbol

[Keynote speaker makes a gesture with their hands that is copied by the conference audience]

[Keynote speaker laughs]

And if you think whilst they are having this free education they should have their rights respected in accordance

with the UN convention

[Keynote speaker makes a gesture with both hands in the air which is copied by the conference audience]

Yeah. I mean that’s what I thought. [laughs] and, and from my take on this if you, if you think that then we

have to realistically look at embedding democratic cultures in every school. Because a democratic culture in my

mind is the only way that students can have their rights fully respected within education and I think every child

has a right to that and every child is not in one of the democratic schools that many people in this room are

privileged to be part of.

As asserted earlier, the conference participants appear to be part of one community that shares similar ideas about democracy in education. What the speaker does here is to verify that this is the case. In other words, by asking the entire audience to share what they think, the speaker wants to ensure common understanding—and thus, implicitly, belonging to this same community of discourse on democracy in education. Let us examine the way the speaker leads her/his audience to ‘agree’ with her/him.

The Excerpt starts with a question from the keynote speaker, ‘can you embed democratic cultures in any school?’ (line 1), the speaker then performs a speech repair when repeating the question by uttering on line 4, ‘can you embed democratic practices into any school’? In conversations speech repairs can show hidden sentiments/meanings behind utterances (Hayashi et al., 2013 ), whereby repairs themselves can be utilised as a defensive discourse strategy to ‘repair’ the images of the self through re-working previous utterances in conversations (Benoit, in Holtzhausen & Zerfass, 2015 ). Here defensive discourse strategies such as speech repairs can mark facework (Lee, 2013 ). When the face is threatened, indicated in the excerpt by the audience’s reaction to the keynote speaker’s question on line 1 and by the Speaker’s re-wording of the question on line 4, the speaker is trying to make the face consistent with their utterances (Haugh and Chang, 2015 ). In this instance, the keynote speaker avoids confrontation with the audience by not repeating the word ‘culture’, instead, the speaker decides to use the word ‘practice’. Here ‘democracy/the democratic’ functions as authoritative discourse as ‘culture’ has seemingly become an uncomfortable taboo or an embarrassingly empty signifier for the speaker to discuss.

‘Democratic cultures’ re-enter the dialogue on line 11, here the speaker distances themselves from ‘democratic cultures’ through speech act exteriorisation whilst at the same time uttering ‘democratic cultures’. The speaker utters ‘Because if you cannot do that you definitely cannot embed democratic cultures in any school’ (lines 10 and 11), combined with laughter (line 12) and the utterances ‘and partly it’s going to rely on you guys’ (line 12) show how the speaker exteriorises ‘democratic cultures’ by deflecting the responsibility onto the audience. Simultaneously, the internal struggles of internally persuasive discourse are characterised by the speaker’s incoherence—the struggle of the others-within-the-self (Bakhtin, 1981 ). The symbolism of the speaker’s requirement for the audience to agree with their statements (see also excerpt 3 below) can show the omnipresence of ‘democracy/the democratic’ as authoritative discourse, yet, it can also show the struggles of how ‘democracy/the democratic’ come-into-being. The Other is simultaneously omnipresent in conjunction with, and, alongside ‘democracy/the democratic’. The iconography of ‘the international money symbol’ (line 16), the ‘UN convention’ (line 18) and rights of the child (line 19 to line 23) shows how these concepts/ideas/logics are ‘assumed’, emphasising the antagonistic and often contradictory manifestations of ‘democratic values’ (Rancière, 2007 ). Though, when faced by international others (an international conference audience), in the setting/context of [an]other, here the struggle of internally persuasive discourse (Bakhtin, 1975 , 1981 ) shown by discourses on ‘democracy/the democratic’ is an internal struggle between, and within, the others-within-the-self. This seems to show potentially hidden sentiments which lie behind her/his utterances.

‘Democracy’ as a convenient substitute for other contested words

This article puts the idea of dialogism at its centre. As asserted earlier, discourses of democracy are embedded in other discourses of democracy, well beyond a given context of utterance. Excerpt 2 is another keynote speech taken from IDEC 2016. While the first excerpt asked the basic question of the place of democracy in schools, this keynote speech looks into what the presenter refers to as Democratic Education 2.0. The keynote speaker is regarded as a ‘democratic education guru’ who runs their own ‘democratic school’ and has written and spoken on ‘democratic education’ around the world. In this excerpt the keynote speaker reflects on the similarities between democratic schools around the world.

Excerpt 2. IDEC 2016 Keynote Speech (ii) ‘Democratic Education 2.0—Changing the paradigm from a pyramid to a network’.

This keynote speech was 48 min long and it was not necessary for us to transcribe all of the speech. Instead we show the speech through two excerpts.

But if we look globally about all of the thousand schools [so-called ‘democratic schools’] all over the world and

we can see what is …. because a lot of people say democratic education it’s different. It’s different in Japan it’s

different in Korea it’s different in Europe. But I think we can say three four things that is in most of the schools.

And the most, what we will see is, first of all we see a democratic community in every school, the school run by a

democratic community, it’s different from school to school, but we have parliament meetings, we have

different meetings, we have different way of voting or consensus, we have a democratic process that runs the

school and all the schools. Another thing we can see in all the schools is pluralistic learning, what it mean, it

means that in all our schools the student[s] choose what to learn, how to learn, with whom to learn, and all these

things… we can find in most democratic schools. another thing we can see ……is dialogic ….

relationship, in all our schools we have a very close relationship between everyone to everyone. This is our goal.

We do not want a close relationship between teachers and students, we want between student to student, between

teacher to student we believe the connection and close relationship is very very important. And the fourth thing,

that does not exist in all of the democratic schools but in a lot of democratic schools, I call it democratic content,

what it means, when you look about the curriculum is a lot of time you adopt the national curriculum and the

national curriculum is very nationality and what, where, what we can see in democratic schools is the curriculum

comes from the point of view of human rights, of the right of the minority, the rights of the weak people, that’s

very very important when you study history and other things.

Excerpt 2 starts with the keynote speaker uttering contradictory utterances. He acknowledges the ‘diversity’ of ‘democratic schools’ by stating ‘it’s different in Japan, it’s different in Korea, it’s different in Europe’ (line 2 and line 3). The speaker then goes on to utter a number of generalisations and assumptions about ‘democratic schools’, such as, ‘what we will see is, first of all, we will see a democratic community in every school’ (line 4), ‘the school run by a democratic community’ (line 4 and line 5), ‘another thing we can see in all the schools is pluralistic learning (line 7), and, ‘in all our schools the student[s] choose, what to learn, how to learn, with whom to learn’ (line 8). The speaker utters these generalisations without problematising and explaining these concepts, such as, how is a ‘democratic community’ understood in ‘democratic schools’? How does the so-called ‘democratic community’ come-into-being? What is meant by ‘pluralistic learning’? None of these questions are problematised. Here, it is important to note, that throughout the excerpt the speaker is constantly reformulating previous utterances. For example, the speaker explains that ‘in all our schools the student[s] choose what they learn’ (line 8), later in the extract the speaker utters ‘when you look at the curriculum… you adopt the national curriculum’ (line 14), so how can students in democratic schools choose what to learn when (as the speaker utters) in most instances teachers are adopting a national curriculum? It can be fair to say, there is a considerable amount of ambiguity about how ‘democracy’ is uttered by the speaker.

It is also important to note the ways the speaker fixes, what the speaker calls, ‘democratic content’ (line 13). The speaker utters ‘democratic content’, then juxtaposes the national curriculum and ‘democratic schools’ by uttering ‘what we can see in democratic schools is curriculum comes from the point of view of human rights’ (line 15 and line 16). This utterance is preceded by the repair ‘what, where, what’ (line 15), and is followed by discourses which could potentially marginalise and ‘other’ (Dervin, 2016 ; Jackson, 2012 ; Holliday, 2011 ) peoples and/or groups. By 'othering' we mean discursive constructs which have been closely linked to the [re]production of power/knowledge in society especially in their ability to marginalise, stereotype and discriminate against peoples and/or groups through essentialised representations (Dervin, 2016 ). The speaker utters human rights in ‘democratic schools’ comes from ‘the rights of the weak people, that’s very very important when you study history and other things’ (line 16 and line 17). As McDonald ( 2016 ) shows, classroom practices and subject textbooks (such as History) can essentialise identities through the reproduction of white victimhood, thus, further marginalising and/or discriminating against one’s other[s]. Here the speaker’s labelling of the ‘weak’ (line 16) engenders discursive boundaries between ‘the strong’ and ‘the weak’. Such a dichotomy, reveals the coherently incoherence of discourses on ‘democratic schools’, yet these incoherencies are bound together by ‘democracy’ as an authoritative discourse—in the sense that ‘democracy’ is simultaneously assumed and generalised (as being present).

Following the presentation, the speaker invited audience participants to engage in a questions and answers session. Excerpt 3 is a short dialogue between a member of the audience and the keynote presenter about democratic schools '3.0, 4.0, 5.0'.

Excerpt 3. Questions and answers following IDEC 2016 Keynote Speech (ii) ‘Democratic Education 2.0—Changing the paradigm from a pyramid to a network’.

Speaker A—I got a question, when I saw the pictures about democratic schools they reminded me of my own

school about 50 years ago… what about schools without classrooms, without principals, without teachers

without curricula, without blackboards, like, democratic schools like 3.0, 4.0, 5.0.

Keynote speaker—…. I think from my point of view, my point of view, every school without is not interesting

me, every school without is not interesting me, not, continue what you want, I am very interested in

….ah…because I don’t need a school that is negative to someone, something. I want to see what you are doing, I

like the idea without [the] principal, I like the idea, but it’s not an idea, it’s half of the idea, what happened, how

to run the school and you need to bring the idea how to run the school without something that’s very very

interesting and for example, I can give you an example, when we say… education city we don’t say a

school without walls, I can say it, a school without walls, or without limited space, but we say it differently, we

say all the city is one big school and then people can ask me, ok, if all the city is one big school why don’t you

say all the world is one big school, and I have answered to this because I think that education in the future

need[s] to be ‘blend learning’, it needs to be face-by-face, and meeting, and using…web meetings. But this,

this is interesting me, yeah I want to see how we run the…schools that give much freedom to peoples.

Speaker A’s question in excerpt 3 (line 1 to line 3) combined with the response of the keynote speaker (line 4 to line 16) in addition to the utterances in excerpt 2, marks authoritative discourse—in part this is marked by the keynote speaker not uttering the word ‘democracy’ or ‘democratic’ in their response. Bakhtin’s concept of assimilation, whereby the speech of others can be detected in one’s own speech, whilst still remaining other (Bakhtin, 1975 , 1981 ), shows how ‘democracy’, or to be more specific, the ‘democratic’ in ‘democratic schools’ is continuously reaccentuated and displaced by, and within, discourse. Here, drawing on excerpts 3 and 4, the ways the keynote speaker and speaker A utter ‘democracy’/ ‘[the] democratic’ is uttered in a totalising and generalised manner fundamentally based upon assumptions around the presence and meaning of ‘democracy’. We argue, an example of the reaccentuation processes of authoritative discourse is the assimilation from ‘democracy/democratic’ to ‘freedom’ in the sense that the speaker is uttering ‘democracy/democratic’ but is actually describing notions of ‘freedom’. In excerpt 4 this is illustrated by the question from speaker A in excerpt 3 (line 1 to line 3), and the keynote speaker’s utterances on line 7 and line 14 whereby both speakers describe ‘freedom’ whilst uttering discourses about ‘democratic schools’. These excerpts show the totalising and generalising ways ‘democracy/the democratic’ is uttered but, also, the totalising logics which support utterances on ‘democracy/the democratic’—in this sense, these excerpts can show how ‘democracy/the democratic’ is a distanced other which can be uttered frequently without critique, in an omnipotent and omnipresent way. As Bakhtin ( 1975 , 1981 ) notes, when discourse functions in an omnipresent way it imparts to everything ‘its own specific tones and from time to time breaking through to become a completely materialised thing, as another’s word fully set off and demarcated (Bakhtin, 1981 , p 347)’, it is this omnipresent function of ‘democracy/the democratic’ which means that, in this context, discourses on ‘democracy/the democratic’ can simultaneously function as authoritative and internally persuasive discourse.

‘Democracy’ as pathos

In order to show the constant metamorphosing of ‘democracy/the democratic’ as authoritative discourse and internally persuasive discourse at the conference under review we show how ‘democracy/the democratic’ are used as discursive strategiesn in what follows.

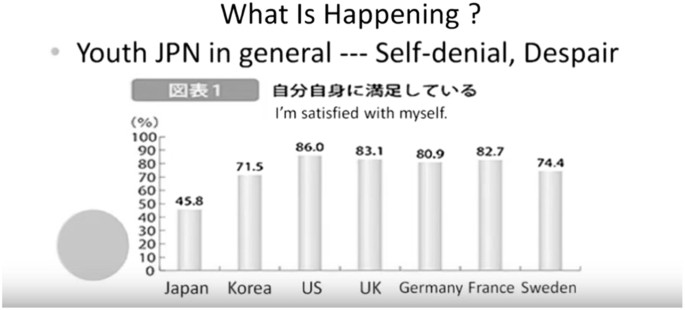

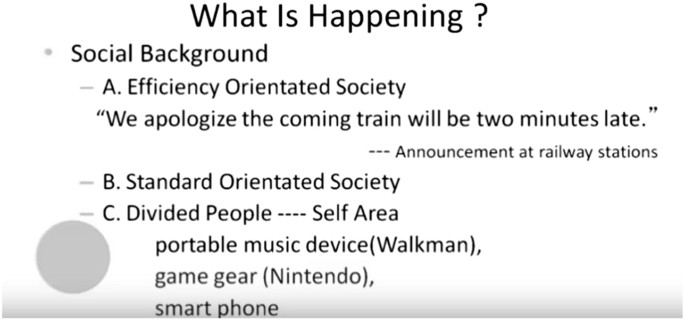

By 'pathos' we mean discourses which invoke an emotional response through text and/or speech which are used as persuasion techniques for the purposes of argumentation (Marinelli, 2015 ). Here it is important to note that pathos can function as a metadiscourse in the ways it can shape public opinions and attitudes within a given context (Ho, 2016 ). Excerpt 4 is taken from the keynote speech entitled ‘The importance of democratic higher education and social systems in making democratic futures’. The speaker is a Japanese academic and the speech predominantly focuses on the Japanese context of education using the Japanese concept of ‘Hikikomori (social withdrawal)’ to justify the necessity of ‘democratic higher education’ in Japan and throughout the world. This excerpt offers an insight into the discourse strategies and discourse styles behind utterances on ‘democracy’ and ‘democratic schools’.