- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- About Children & Schools

- About the National Association of Social Workers

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous

Survivors of School Bullying: A Collective Case Study

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Octavio Ramirez, Survivors of School Bullying: A Collective Case Study, Children & Schools , Volume 35, Issue 2, April 2013, Pages 93–99, https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/cdt001

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This article explores the coping strategies of five junior-high school students with a history of peer victimization and how those strategies help them manage the effects of bullying. The data were collected using observations, interviews, and a review of school records. The data were analyzed using categorical aggregation, direct interpretation, constant comparison, and identification of patterns. On analysis, the following categories emerged from the data: identification of supportive systems, in-class strategies, premonition and environmental analysis, thought cessation and redirection, and masking. These categories were amalgamated into two general patterns: preventive and reactive strategies. The results of the study show that although the strategies helped participants to cope with the immediate effects of bullying, they did not exempt participants from the psychological and emotional implications of peer victimization.

National Association of Social Workers members

Personal account.

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Short-term Access

To purchase short-term access, please sign in to your personal account above.

Don't already have a personal account? Register

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| November 2016 | 1 |

| December 2016 | 2 |

| January 2017 | 2 |

| February 2017 | 26 |

| March 2017 | 25 |

| April 2017 | 21 |

| May 2017 | 14 |

| June 2017 | 13 |

| July 2017 | 12 |

| August 2017 | 8 |

| September 2017 | 13 |

| October 2017 | 20 |

| November 2017 | 19 |

| December 2017 | 30 |

| January 2018 | 40 |

| February 2018 | 6 |

| March 2018 | 22 |

| April 2018 | 9 |

| May 2018 | 6 |

| June 2018 | 5 |

| July 2018 | 6 |

| August 2018 | 6 |

| September 2018 | 4 |

| October 2018 | 11 |

| November 2018 | 18 |

| December 2018 | 19 |

| January 2019 | 17 |

| February 2019 | 17 |

| March 2019 | 14 |

| April 2019 | 18 |

| May 2019 | 15 |

| June 2019 | 16 |

| July 2019 | 15 |

| August 2019 | 16 |

| September 2019 | 15 |

| October 2019 | 15 |

| November 2019 | 17 |

| December 2019 | 18 |

| January 2020 | 7 |

| February 2020 | 11 |

| March 2020 | 9 |

| April 2020 | 17 |

| May 2020 | 3 |

| June 2020 | 11 |

| July 2020 | 14 |

| August 2020 | 9 |

| September 2020 | 13 |

| October 2020 | 15 |

| November 2020 | 6 |

| December 2020 | 4 |

| January 2021 | 6 |

| February 2021 | 9 |

| March 2021 | 9 |

| April 2021 | 10 |

| May 2021 | 10 |

| June 2021 | 21 |

| July 2021 | 13 |

| August 2021 | 9 |

| September 2021 | 9 |

| October 2021 | 16 |

| November 2021 | 12 |

| December 2021 | 21 |

| January 2022 | 10 |

| February 2022 | 3 |

| March 2022 | 19 |

| April 2022 | 20 |

| May 2022 | 10 |

| June 2022 | 5 |

| July 2022 | 2 |

| August 2022 | 9 |

| September 2022 | 5 |

| October 2022 | 5 |

| November 2022 | 4 |

| December 2022 | 8 |

| January 2023 | 6 |

| February 2023 | 2 |

| March 2023 | 3 |

| April 2023 | 7 |

| May 2023 | 8 |

| June 2023 | 2 |

| July 2023 | 9 |

| August 2023 | 7 |

| September 2023 | 5 |

| October 2023 | 17 |

| November 2023 | 6 |

| December 2023 | 1 |

| January 2024 | 2 |

| February 2024 | 4 |

| March 2024 | 7 |

| May 2024 | 8 |

| June 2024 | 1 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- About Children & Schools

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1545-682X

- Print ISSN 1532-8759

- Copyright © 2024 National Association of Social Workers

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Bullying in schools: the power of bullies and the plight of victims

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Psychology.

- PMID: 23937767

- DOI: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115030

Bullying is a pervasive problem affecting school-age children. Reviewing the latest findings on bullying perpetration and victimization, we highlight the social dominance function of bullying, the inflated self-views of bullies, and the effects of their behaviors on victims. Illuminating the plight of the victim, we review evidence on the cyclical processes between the risk factors and consequences of victimization and the mechanisms that can account for elevated emotional distress and health problems. Placing bullying in context, we consider the unique features of electronic communication that give rise to cyberbullying and the specific characteristics of schools that affect the rates and consequences of victimization. We then offer a critique of the main intervention approaches designed to reduce school bullying and its harmful effects. Finally, we discuss future directions that underscore the need to consider victimization a social stigma, conduct longitudinal research on protective factors, identify school context factors that shape the experience of victimization, and take a more nuanced approach to school-based interventions.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Relationships among cyberbullying, school bullying, and mental health in Taiwanese adolescents. Chang FC, Lee CM, Chiu CH, Hsi WY, Huang TF, Pan YC. Chang FC, et al. J Sch Health. 2013 Jun;83(6):454-62. doi: 10.1111/josh.12050. J Sch Health. 2013. PMID: 23586891

- School bullying: development and some important challenges. Olweus D. Olweus D. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9:751-80. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185516. Epub 2013 Jan 3. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013. PMID: 23297789 Review.

- [Cyber-bullying in adolescents: associated psychosocial problems and comparison with school bullying]. Kubiszewski V, Fontaine R, Huré K, Rusch E. Kubiszewski V, et al. Encephale. 2013 Apr;39(2):77-84. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2012.01.008. Epub 2012 May 28. Encephale. 2013. PMID: 23095590 French.

- School bullying: its nature and ecology. Espelage DL, De La Rue L. Espelage DL, et al. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2011 Nov 4;24(1):3-10. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2012.002. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2011. PMID: 22909906 Review.

- [How valid are student self-reports of bullying in schools?]. Morbitzer P, Spröber N, Hautzinger M. Morbitzer P, et al. Prax Kinderpsychol Kinderpsychiatr. 2009;58(2):81-95. doi: 10.13109/prkk.2009.58.2.81. Prax Kinderpsychol Kinderpsychiatr. 2009. PMID: 19334399 German.

- How peer relationships affect academic achievement among junior high school students: The chain mediating roles of learning motivation and learning engagement. Shao Y, Kang S, Lu Q, Zhang C, Li R. Shao Y, et al. BMC Psychol. 2024 May 16;12(1):278. doi: 10.1186/s40359-024-01780-z. BMC Psychol. 2024. PMID: 38755660 Free PMC article.

- Adolescents High in Callous-Unemotional Traits are Prone to be Bystanders: The Roles of Moral Disengagement, Moral Identity, and Perceived Social Support. Wang X, Wei H, Wang P. Wang X, et al. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2024 May 13. doi: 10.1007/s10578-024-01709-y. Online ahead of print. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2024. PMID: 38739301

- Korean autistic persons facing systemic stigmatization from middle education schools: daily survival on the edge as a puppet. Yoon WH, Seo J, Je C. Yoon WH, et al. Front Psychiatry. 2024 Mar 28;15:1260318. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1260318. eCollection 2024. Front Psychiatry. 2024. PMID: 38606409 Free PMC article.

- The Relationship between a Competitive School Climate and School Bullying among Secondary Vocational School Students in China: A Moderated Mediation Model. Huang X, Li Q, Hao Y, An N. Huang X, et al. Behav Sci (Basel). 2024 Feb 10;14(2):129. doi: 10.3390/bs14020129. Behav Sci (Basel). 2024. PMID: 38392482 Free PMC article.

- Connections of bullying experienced by Kyokushin karate athletes with the psychological state: is "a Cure for Bullying" safe? Vveinhardt J, Kaspare M. Vveinhardt J, et al. Front Sports Act Living. 2024 Jan 25;6:1304285. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2024.1304285. eCollection 2024. Front Sports Act Living. 2024. PMID: 38333430 Free PMC article.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

- Cited in Books

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ingenta plc

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

An official website of the United States government, Department of Justice.

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

NCJRS Virtual Library

Dealing with a schoolyard bully: a case study, additional details, no download available, availability, related topics.

Color Scheme

- Use system setting

- Light theme

A case study of bullying: Ex-Freeman High School student says peer harassed him for years; alleged bully denies it

Dana Condrey’s son didn’t want to leave his high school, especially not because of a bully.

But in September, the 16-year-old junior transferred to Ferris High School, after what the family describes as years of being taunted and beat up by a fellow Freeman High School student.

“It just got to the point where (he) just said, ‘I’m done. I want out,’ ” Condrey said.

The bullying started in the fifth grade. Five years later, in June 2015, Condrey’s son was thrown to the ground during gym class at Freeman by a fellow student. The fall blackened his eye and burst his eardrum, according to a police record of the incident.

Both boys were freshmen and the violence was captured on video and investigated by police. No charges were filed.

That was the most egregious and visible act in a long string of harassment and intimidation, according to the boy and his parents.

They obtained an anti-harassment order from a judge in October 2015 after a hearing where testimony and documents were submitted.

However, the boy accused of the harassment and his parents have been fighting back. Their attorney, Julie Watts, found the order troubling. So far those efforts, including a February ruling by the Washington State Court of Appeals, have failed.

“Anti-harassment orders have criminal penalties if they are violated, even accidentally, and having one on your record can prevent you from getting future employment or future housing,” Watts said in an email in response to questions about the case.

For instance, Watts said the order allows a kid to “sit down at the restrained kid’s lunch table so that he has to leave or can’t eat with his friends without being charged with a crime.”

However, Condrey, the mother of the boy thrown to the ground, said this is not a valid concern, since her son transferred to Ferris in September.

Robert Cossey, the attorney for Condrey and her son, said the family didn’t want to go to court, and tried multiple times to resolve the issue informally.

“It was the last resort,” Cossey said. “My clients didn’t have a lot of money. They didn’t want to hire me. They didn’t want to go through this process.”

In court documents, the boy who claims he was bullied wrote that he’d asked teachers and administrators to put a stop to the harassment numerous times.

“I have tried to do the right thing for many years but it hasn’t made it stop,” he wrote in a statement to the court.

The accused bully and his family claim the two teenagers were friends and that the incident in the gym was “simply an accident.”

“I have never physically threatened him or harmed him,” the boy stated in written testimony to the court.

His father is a member of the Freeman School Board and hired a private investigator to probe the claims against his son.

According to the private investigator’s interview with staff and students, no one witnessed the alleged bullying and harassment prior to the gym incident. Several of the alleged bully’s football teammates also wrote letters in support of him.

However, an email exchange from 2011 documents an incident in which the alleged bully shoved the other child into a garbage can.

In that email, sent to a school staff member, the bullied boy’s father writes, “We can deal with a little childish play amongst boys … but we are really concerned that one day the pushing on ice into a garbage can is going to result in him hitting his head, (or) him getting really hurt by getting punched in the lower back.”

The alleged victim’s family claimed they tried multiple times to resolve the issues informally. However, the alleged bully’s family said they received no such communications, according to court documents.

In 2013, Condrey, the alleged victim’s mother, sent an email to a Freeman staff member claiming her son had “been punched, tripped, kicked, wrestled to the ground in the parking lot, spit on, pulled out of his chair, and hit in the head with a book bag” by the alleged bully.

That email was subsequently forwarded to the alleged bully’s father’s official Freeman School District email address, according to court documents.

The protection order allows the alleged bully to graduate from Freeman. However, he must stay 20 feet away from the alleged victim and may not speak to him.

In the appeals, the alleged bully challenged the validity of the anti-harassment order, claiming there wasn’t sufficient evidence, that the investigation wasn’t sufficient and that the incident in the gym was not indicative of a pattern.

Watts argued the anti-harassment order is not intended to be used to resolve what state code calls “schoolyard scuffles.”

However, the appellate judges upheld the October 2015 decision, claiming that by virtue of the police investigating the gym incident it had become more than a school yard scuffle.

“From these facts, it was reasonable for the trial court to conclude that (he) would likely resume harassment … as he had before, if the order did not extend through the end of high school,” the appellate court wrote.

Condrey said her son is shocked at the difference in school cultures between Ferris and Freeman.

“It was normal, it was part of the day,” she said of bullying. “And now he’s at Ferris and he never sees any of that, it’s not tolerated.”

Editors note: This story has been updated to include a correction that the case was not tried by a jury.

Untapped home equity offers financial flexibility

The cost of borrowing has risen sharply in recent years, so when it comes to tackling a big expense, it’s important to know about the options.

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- PubMed/Medline

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

How teachers deal with cases of bullying at school: what victims say.

1. Introduction:

1.1. the nature of interventions in cases of school bullying, 1.2. victim-reported experiences and effective teacher action, 1.3. severity, 1.4. bullying by groups, 1.5. gender and age, 1.6. aim and hypotheses.

- The aim was to describe what victimized students believed the school did after they sought help from a teacher.

- the success of the intervention, as reported by students, was inversely related to the severity of the reported negative emotional impact of the bullying;

- the greater the reported frequency with which the bullying was seen to be perpetrated by a group of students, the less successful the intervention would be;

- interventions with younger students would be associated with more positive outcomes.

2.1. Ethics

2.2. procedure, 2.3. sample, 3. measures, 3.1. frequency of being bullied, 3.2. severity of the bullying, 3.3. effectiveness of the intervention, 3.4. victims’ perceptions of actions taken by the school after requesting help, 3.5. data analysis, 3.6. demographics, 4.1. reported frequencies of bullying, 4.2. reported teacher actions, 4.3. reported outcomes for bullying following interventions in cases according to gender and age group, 4.4. reported emotional impact and reported frequency of being bullied by (i) an individual and (ii) a group in relation to intervention outcomes, 5. discussion, 5.1. implications for interventions in cases of bullying, 5.2. strengths and limitations, 6. conclusions, conflicts of interest.

- Cornell, D.; Limber, S.P. Law and Policy on the concept of bullying at school. Am. Psychol. 2015 , 70 , 333–343. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Thompson, F.; Smith, P.K. The Use and Effectiveness of Anti-Bullying Strategies in Schools ; Research Report, DFE-RR098; Department for Education: London, UK, 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rigby, K.; Johnson, K. The Prevalence and Effectiveness of Anti-Bullying Strategies Employed in Australian Schools ; University of South Australia: Adelaide, Australia, 2016. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sherer, Y.C.; Nickerson, A.B. Anti-bullying practices in American schools: Perspectives of school psychologists. Psychol. Sch. 2010 , 47 , 217–229. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Smith, P.K.; Sharp, S. School Bullying: Insights and Perspectives ; Routledge: London, UK, 1994. [ Google Scholar ]

- Olweus, D. Bullying at School: What We Know and What We Can Do ; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1993. [ Google Scholar ]

- UNESCO. School Bullying and Violence: Global Status, Trends, Drivers and Consequences ; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, UNESCO Publication: Paris, France, 2018. [ Google Scholar ]

- Smith, B.H.; Low, S. The role of social-emotional learning in bullying prevention. Theory Pract. 2013 , 52 , 280–287. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Divecha, D.; Brackett, M. Rethinking School-Based Bullying Prevention through the Lens of Social and Emotional Learning: A Bioecological Perspective. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2019 . [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Rigby, K. School perspectives on bullying and preventive strategies: An exploratory study. Aust. J. Educ. 2017 , 24 , 24–39. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Garandeau, C.F.; Poskiparta, E.; Salmivalli, C. Tackling acute cases of school bullying in the KiVa anti-bullying program: A comparison of two approaches. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2014 , 42 , 981–991. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Shu, S.; Smith, P.K. What good schools can do about bullying: Findings from a survey in English schools after a decade of research and action. Childhood 2000 , 7 , 193–212. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fekkes, M.; Pijpers, F.I.M.; Verloove-Vanhorick, S.P. Bullying: Who does what, when, and where? Involvement of children, teachers, and parents in bullying behaviour. Health Educ. Res. 2005 , 20 , 81–91. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Davis, S.; Nixon, C. What students say about bullying. Educ. Leadersh. 2011 , 69 , 18–23. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rigby, K. Manual for the Peer Relations Questionnaire (PRQ) ; Professional Reading Guide: Point Lonsdale, Australia, 1998. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rigby, K.; Barnes, A. To tell or not to tell: The victimized student’s dilemma. Youth Stud. Aust. 2002 , 21 , 33–36. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rigby, K.; Smith, P.K. Is school bullying really on the rise? Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2011 , 14 , 441–455. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wachs, S.; Bilz, L.; Niproschke, S.; Schubarth, W. Bullying Intervention in Schools: A Multilevel Analysis of Teachers’ Success in Handling Bullying from the Students’ Perspective. J. Early Adolesc. 2019 , 39 , 642–668. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rigby, K. Bullying Interventions in Schools: Six Basic Approaches ; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2012. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rigby, K. How teachers address cases of bullying in schools: A comparison of five reactive approaches. Educ. Psychol. Pract. Theory Res. Educ. Psychol. 2014 , 30 , 409–419. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Robinson, G.; Maines, B. Bullying: A Complete Guide to the Support Group Method ; Sage: London, UK, 2008. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pikas, A. New developments of the Shared Concern Method. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2002 , 23 , 307–336. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Bauman, S.; Del Rio, A. Pre-service teachers’ response to bullying scenarios: Comparing physical, verbal, and relational bullying. J. Educ. Psychol. 2006 , 98 , 219. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Strout, T.D.; Vessey, J.A.; DiFazio, R.L.; Ludlow, L.H. The Child Adolescent Bullying Scale (CABS): Psychometric evaluation of a new measure. Res. Nurs. Health 2018 , 41 , 252–264. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ortega, R.; Elipe, P.; Mora-Mercha, J.A.; Luisa, M.; Genta, N.L.; Brighi, G.A.; Smith, P.K.; Thompson, F.; Tippett, P.T. The Emotional Impact of Bullying and Cyberbullying on Victims: A European Cross-National Study. Aggress. Behav. 2012 , 38 , 342–356. [ Google Scholar ]

- Veenstra, R.; Siegwar, S.; Bonne, J.H.; DeWinter, A.F.; Verhuslt, F.C.; Ormel, J. The dyadic nature of bullying and victimization: Testing a Dual-perspective Theory. Child Dev. 2007 , 78 , 1843–1854. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Thornberg, R.S.; Knutsen, S. Teenagers’ Explanations of Bullying. Child Youth Care Forum 2011 , 3 , 177–192. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Stylianos, S.; Plexousakis, S.S.; Kourkoutas, E.T.; Chatira, K.; Nikolopoulos, D. School Bullying and Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms: The Role of Parental Bonding. Front. Public Health 2019 , 7 , 75. [ Google Scholar ]

- The Wesley Mission. Give Kids A Chance: No One Deserves to be Left Out ; Wesley Mission: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Deng, Y.; Chang, L.; Yang, M.; Huo, M.; Zhou, R. Gender Differences in Emotional Response: Inconsistency between Experience and Expressivity. PLoS ONE 2016 , 11 , e158666. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Chaplin, T.; Aldao, A. Gender differences in emotion expression in children: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2012 , 139 , 735–765. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ] [ Green Version ]

- Smith, P.K.; Salmivalli, C.; Cowie, H. Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying: A commentary. J. Exp. Criminol. 2012 , 8 , 433–441. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Yeager, D.S.; Fong, C.T.; Lee, H.Y.; Espelage, D.L. Declines in efficacy of anti-bullying programs among older adolescents: Theory and three-level meta-analysis. J. Dev. Psychol. 2015 , 37 , 36–51. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Finkelhor, D.; Turner, H.A.; Shattruck, M.A.; Sherry, L.H. Childhood exposure to violence, crime and abuse. JAMA Pediatrics 2014 , 169 , 746–754. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hair, J.F.; Tatham, R.L.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis ; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bauman, S.; Rigby, K.; Hoppa, K. US teachers’ and school counsellors’ strategies for handling school bullying incidents. Educ. Psychol. 2008 , 28 , 837–856. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Burger, C.D.; Strohmeier, D.; Sprober, N.; Bauman, S.; Rigby, K. How teachers respond to school bullying: An examination of self-reported intervention strategy use, moderator effects, and concurrent use of multiple strategies. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015 , 51 , 191–201. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rigby, K. Effects of peer victimization in schools and perceived social support on adolescent well-being. J. Adolesc. 2000 , 23 , 57–68. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Newman, M.L.; Holden, G.W.; Delville, Y. Isolation and the stress of being bullied. J. Adolesc. 2005 , 28 , 343–357. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Healy, K.L.; Sanders, M.R.; Aarti, I. Facilitative parenting and children’s social, emotional and behavioral adjustment. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2014 , 24 , 1762–1779. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Smith, P.K.; Howard, S.J.; Thompson, F. Use of the Support Group Method to Tackle Bullying and Evaluation from Schools and Local Authorities in England. Pastor. Care Educ. 2007 , 5 , 4–13. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rigby, K. The Method of Shared Concern: A Positive Approach to Bullying ; ACER: Camberwell, UK, 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rigby, K.; Griffiths, C. Addressing cases of bullying through the Method of Shared Concern. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2011 , 32 , 345–357. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Veldkamp, S.A.M.; Boomsma, D.I.; De Zeeuw, E.L.; van Beijsterveldt, C.E.; Bartels, M.; Dolan, C.V.; van Bergen, E. Genetic and Environmental Influences on Different Forms of Bullying Perpetration, Bullying Victimization, and Their Co-occurrence. Behav. Genet. 2019 , 49 , 432. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ] [ Green Version ]

- Solberg, M.E.; Olweus, D. Prevalence estimation of school. J. Couns. Psychol. 2003 , 35 , 281–296. [ Google Scholar ]

| Student Reports | Reported Effects on Bullying | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stopped | Reduced | No Change | Got Worse | ||

| Shu and Smith, 2000 | 26 | 29 | 28 | 16 | |

| Rigby, 1998 | 43 | 8 | |||

| Rigby and Barnes, 2002 | 39 | 18 | |||

| Fekkes, Pijpers and Verloove-Vanhorick, 2005 | 34 | 17 | |||

| Davis and Nixon, 2011 | 37 | 29 | |||

| Rigby and Johnson, 2016 | 29 | 40 | 23 | 8 | |

| Wachs et al., 2019 * | 22 | 44 | 30 | 4 | |

| Reported Teacher Action | Yes | DK |

|---|---|---|

| The teacher told the bully or bullies to stop bullying me | 63.5 | 17.8 |

| A teacher got the bully or bullies to apologize | 60.0 | 14.9 |

| The bully was given a warning | 55.7 | 26.6 |

| The teacher deprived the bully of privileges at school | 25.4 | 27.5 |

| The bully/bullies were given a detention | 22 7 | 23.4 |

| The bully was made to do community work | 22.4 | 21.4 |

| The bully was suspended from school | 17.3 | 16.8 |

| The bully was excluded from school | 9.6 | 13.7 |

| A teacher advised me on what I could do to stop the bullying | 62.7 | 15.7 |

| The school got in touch with parents of the student(s) bullying me | 41.7 | 26.0 |

| A teacher talked to my parents about what was happening | 40.7 | 20.1 |

| The school suggested my parents get in touch with the bully’s parents | 19.9 | 29.9 |

| A teacher met with me and the bully to sort things out together | 51.5 | 17.2 |

| The school arranged meeting with a student mediator | 14.5 | 29.5 |

| Arranged for help from outside school, e.g., a psychologist | 12.2 | 17.3 |

| The police were informed | 6.2 | 21.6 |

| The teacher kept an eye on things for the next few weeks | 52.3 | 25.1 |

| The teacher spoke with the class to get their help | 42.0 | 17.6 |

| Bullying Stopped | Bullying Reduced | Bullying Stayed the Same | Bullying Got Worse | Total n | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | ||||||

| Young | 19 (29.7) | 21 (32.8) | 18 (28.1) | 6 (9.4) | 64 | |

| Older | 5 (17.9) | 16 (57.1) | 6 (21.4) | 1 (3.6) | 28 | |

| Girls | ||||||

| Young | 33 (38.4) | 32 (37.2) | 14 (16.3) | 7 (8.1) | 86 | |

| Older | 8 (17.8) | 19 (42.2) | 15 (33.3) | 3 (6.7) | 45 |

| Outcome of Teacher Interventions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | t | p | VIF | |

| Reported emotional impact | −0.174 | −2.699 | 0.014 | 1.234 |

| Frequency of individual bullying | −0.115 | −1.584 | 0.115 | 1.317 |

| Frequency of group bullying | −0.218 | −4.147 | 0.000 | 1.257 |

| Age (in years) | −0.100 | −1.547 | 0.123 | 1.033 |

| Gender (Boy = 1; Girl = 2) | +0.070 | +1.072 | 0.285 | 1.061 |

Share and Cite

Rigby, K. How Teachers Deal with Cases of Bullying at School: What Victims Say. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020 , 17 , 2338. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072338

Rigby K. How Teachers Deal with Cases of Bullying at School: What Victims Say. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health . 2020; 17(7):2338. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072338

Rigby, Ken. 2020. "How Teachers Deal with Cases of Bullying at School: What Victims Say" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 7: 2338. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072338

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

- DOI: 10.1007/s43076-024-00385-0

- Corpus ID: 270386090

Understanding Children and Adolescents’ Experiences Being Bullied: A Mixed-Methods Study

- Makenna A. Snodgrass , Sarah L. Smith , Samantha J. Gregus

- Published in Trends in Psychology 10 June 2024

- Psychology, Sociology

49 References

Bullying among young adolescents: the strong, the weak, and the troubled., symptoms of post-traumatic stress among victims of school bullying, school bullying and association with somatic complaints in victimized children, bullying and ptsd symptoms, distressed bullies, social positioning and odd victims: young people's explanations of bullying, bullying involvement in adolescence: implications for sleep, mental health, and academic outcomes, bullying involvement, teacher–student relationships, and psychosocial outcomes, continued bullying victimization in adolescents: maladaptive schemas as a mediational mechanism, retrospective accounts of bullying victimization at school: associations with post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and post-traumatic growth among university students, bullying victimization and perpetration among u.s. children and adolescents: 2016 national survey of children’s health, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Analyzing the Risk of Being a Victim of School Bullying. The Relevance of Students’ Self-Perceptions

- Open access

- Published: 15 June 2023

- Volume 16 , pages 2141–2163, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- M.M. Segovia-González ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0112-5668 1 ,

- José M. Ramírez-Hurtado ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2289-1874 1 &

- I. Contreras ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3259-5697 1

3417 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

School bullying is a growing concern in almost all developed economies, bringing negative and serious consequences for those students involved in the role of victims. In this paper, we propose to analyze this topic for the case of Spain, considering the data compiled in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) report in 2018. The sample size consists of 12,549 15-old-year students (51.84% females and 48.16% males). With the help of structural equation models (SEM), we aim to detect the relationship between the risk of being a victim of bullying and several self-appreciations expressed by the students. We have considered variables that try to measure individual perceptions in several aspects, such as the self-image, the help provided by parents and teachers and how the school environment’s safety is perceived. A multigroup analysis was also performed to see the impact of the socioeconomic level of the families and the students’ academic performances on the proposed model. We conclude that several of those aspects are directly related with the risk of being bullied and this risk is higher in those students who present school failure and have a lower socioeconomic status. In this regard, the results would permit pointing out some aspects in which the decision-makers can focus their proposals to establish prevention measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Does Bullying Affect the School Performance of Brazilian Students? An Analysis Using Pisa 2015

The association of individual and contextual variables with bullying victimisation: a cross-national comparison between Ireland and Lithuania

Subjective Well-Being and Bullying Victimisation: A Cross-National Study of Adolescents in 64 Countries and Economies

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Education must be seen as one of the main factors that impact on the progress and development of individuals and societies. It not only provides knowledge, it is also a vehicle to fortify positive values that, as a society, we need to develop. Education has proven itself to be a valuable tool to improve welfare standards, reduce social inequalities and guarantee a sustained economic growth. In that line, it should be considered as one of the sources in the sustainable development of economies.

From an individual point of view, every phase of the educational process is a significant step in the individual’s development. And at every one of those stages both the schools and the families are the main support for the development of teenagers. The contents and values they receive at these centers and obtain from their families will be used as the basis to prevent the formation of undesired behaviors. The salience of these contexts justifies the importance of guaranteeing that schools should be a safe place.

Peer violence in schools is a widespread and growing phenomenon that concerns most societies around the world. One of the forms of violence that has been attracting attention in the last decades is bullying. This is defined as “a behavior of physical and/or psychological persecution carried out by one or several students against another student who is chosen as the victim of repeated attacks” (Olweus, 1993 ). The most defining characteristic of bullying is the existence of a systematic abuse of power and an unequal power relationship between the bully and the victim (Pellegrini & Long, 2002 ; Salmivalli & Peets, 2008 ). Many researchers have shown that bullying is not an isolated problem, exclusive of certain countries or cultures. On the contrary, it is widely extended in societies all over the world (Cook, et al., 2010a ; Eslea, et al., 2004 ).

The literature has studied the problem of bullying as a group phenomenon. In addition to the main participants, bullies and bully victims, the remaining students are part of the process, assuming different roles. Hence, we can find reinforcers of the bully, defenders of the victim, or passive bystanders. Adverse behavioral and psychological outcomes have been found for all the referred groups (Rivers, et al., 2009 ; Salmivalli, 2010 ).

With respect to actions, bullying can be classified into three main categories (Olweus, 1993 ): physical, that includes pushing, kicking, taking belongings…; verbal, including performances like name-calling, teasing, threatening, etc.; and relational, including public humiliation and social exclusion. Considering the form of interaction, the actions can be direct or indirect. The former includes those physical and verbal behaviors that occur face-to-face (pushing or verbal harassment). The latter involves those attitudes in which the victim or the bullies are not necessarily present, for instance, spreading malicious rumors, and relational aggression (Olweus, 1993 ). This last form of victimization is more difficult to detect and remove. In fact, most analyses of bullying victimization have found that students more commonly report indirect forms of bullying as opposed to the direct physical form of bullying (Dinkes, et al., 2007 ; Wang, et al., 2009 ).

It has been shown that these categories of bullying do not occur in schools with the same incidence and intensity. Moreover, the prevalence of each type of actions is related with different aspects such as the students’ ages, the country’s culture, gender, and the socioeconomic level, among others. With respect to students’ ages, the rates of bullying vary significantly from one grade to another. On the whole, the risk of being a victim of bullying declines as we move forward to the next school level: it reduces as the students pass from elementary to middle school and from middle school to high school (Khoury-Kassabri, et al., 2004 ; Rigby, 2002 ). Other studies that highlight the relation between bullying and the students’ ages are, among others, those ofÁlvarez-García et al. ( 2015 ); Cook, et al., 2010b ); Saarento et al. ( 2015 ).

Regarding the role of gender, the literature shows that boys are more frequently involved in bullying than girls (Álvarez-García, et al., 2015 ; Cook, et al., 2010b ; Smith, et al., 2019 ). Boys are implicated more frequently in both roles, as victims and bullies, especially in those actions that include physical aggressions. On the contrary, girls are involved in those actions that involve indirect aggressions: teasing or gossiping about peers or relational victimization (Bradshaw, et al., 2015 ; Carbone-Lopez, et al., 2010 ; Tiliouine, 2015 ).

There are also studies analyzing a possible relationship between bullying victimization and socioeconomic status (Allen, et al., 2022 ; Jain, et al., 2018 ). In Tippett & Wolke ( 2014 ) we can find a review of the published literature on bullying in schools related with socioeconomic status. In the analysis, the authors found that victimization was positively associated with low socioeconomic levels and negatively associated with high socioeconomic levels. In the same line, Tiliouine ( 2015 ) indicates that victims of bullying came from less advantaged families and present more frequent absenteeism at school.

From the premise that bullying is a very complex process in which many interrelated variables should be considered, the aim of this study is the analysis of the main factors associated with the risk of being a victim of bullying attitudes. We have considered a quantitative approach to analyze the importance of several aspects, such as the performance of the family, teachers, the environment provided by the school and the students’ self-esteem. The target is to analyze if certain aspects can be considered as determinant for an individual to be a victim of bullying.

We have considered the information provided by the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) report from 2018. In our view, students aged 15 are at a crucial moment in their physical and emotional development. The PISA reports include not only academic performance data. A large amount of context information is included in every report that permits obtaining a broad picture of the situation of students in every country. In particular, we have considered three main aspects of their life that influence how they feel: how satisfied they are with how they look, with their relationships with their parents, and with life at school (OECD, 2019b ).

1.1 Literature Review

There is a large body of research on the problem of bullying. It is one of the main topics in the field of education because of its social impacts. We can find some systematic investigations that try to analyze the risk factors from a global perspective, examining individual and contextual factors that have proven to be correlated with bullying. In this line, we come across works mainly focused on reviewing the literature and meta-analyses at the level of the individual’s characteristics. Examples of these works are the studies of Álvarez-García et al. ( 2015 ); Cook, et al., 2010b ); Lopez et al. ( 2011 ). Other papers have proposed a systematic review of the existing literature at a school and classroom level, analyzing which factors are directly related with bullying situations; see, among others Azeredo et al. ( 2015 ), and Saarento et al. ( 2015 ). Other works have tried to analyze the predictive value of specific factors, such as the socioeconomic status (Tippett & Wolke, 2014 ), empathy (Van Noorden, et al., 2014 ), and the role of parents (Lereya, et al., 2013 ; Nocentini, et al., 2019 ).

Other meta-analysis papers that analyze the consequences of bullying victimization are those of Gini and Pozzoli ( 2009 ), Moore et al. ( 2017 ), (with a particular interest in psychosomatic problems), Hansen et al. ( 2012 ) (analyzing psychological factors), and Hawker and Boulton ( 2000 ) (which proposes the study of psychosocial maladjustment).

Much of the research uses quantitative methods to deal with the problem. In particular, a number of studies propose the analysis of relations among variables using structural equation models (SEM), which will be the basis of our subsequent analysis. In this line, there is the work of Gini et al. ( 2007 ), which shows the relations between empathy and individual behavior in bullying situations, differentiating between pro-bullying and defending-bullying individuals. Considering a sample of Italian adolescents, it presents two possible factors (the cognitive component and the emotional aspect of empathy) that can influence the behavior of individuals against bullying (for both active defenders and passive bystanders). In a posterior paper, Gini et al. ( 2008 ), the relevance of gender and social self-efficacy is incorporated into the analysis and Pozzoli and Gini ( 2012 ) analyze the attitudes toward bullying.

In Roland and Idsøe ( 2001 ) the authors study how proactive (emotions involved in the aggressor) and reactive (the social event that induces the behavior) aggressiveness were related to bullying. In Meyer-Adams and Conner ( 2008 ) the victimization by bullying is analyzed, identifying those risk factors in the psychosocial environment of the school. Other authors find mediating effects of emotional symptoms on the association between homophobic bullying victimization and problematic internet/smartphone (Li, et al., 2020 ) or the mediating effect of regulatory emotional self-efficacy on the link between self-esteem and school bullying (Wang, et al., 2018 ).

Additional factors, such as the school climate, satisfaction at school, and schoolwork-related anxiety are included in the models in an attempt to explain satisfaction in life and well-being. Examples of this working line are the papers from Borualogo and Casas ( 2023 ), Huang ( 2020 ), Tiliouine ( 2015 ), and Varela et al. ( 2019 , 2021 ). The connection between the school climate and bullying victimization was studied by Chen et al. ( 2020 ) from a cross-country perspective.

It is important to bear in mind that bullying could have very serious consequences. Hence, some studies have shown a relevant link between non-fatal suicidal behaviors and bullying victimization (Zhao, et al., 2022 ), and the different bullying experiences: bullies, victims, and bully-victims (Wu, et al., 2021 ). In Zhang et al. ( 2022 ), the mediating role of the family, anxiety and resilience is analyzed.

In this context, we propose to analyze the relevance of students’ perceptions about the help and support provided by parents, teachers, and the school when the risk factors of being a bullying victim are measured.

1.2 Theoretical Background

The theoretical framework of the present study is based on the theories of the social-ecological model (Bronfenbrenner, 1979 ) and person- and stage-environment fit (Eccles, et al., 1993 ), in the sense that social settings can impact on the human behavior and human development. Specifically, we draw on social learning theory to emphasize that individuals learn from their family, peers, and prior events (Bandura, 1973 ). Learning by seeing and doing is the foundation of social learning theory of bullying. In this regard, we refer to the immediate context in which the adolescent is directly involved, and we consider the parent-child relationship, the role of the teachers, and the safety at school.

The aim of this work is to study the relationships between bullying victimization and students’ own perceptions of their parents, teachers, school safety, and positive self-beliefs. A multigroup analysis was also carried out to see the impact of the socioeconomic level of the families and the students’ academic performances on the proposed model. There are few studies that jointly relate all the characteristics that we consider in the proposed model, which includes the analysis of the impact of the socioeconomic and cultural level and academic failure. The existing relationships of each or several of the characteristics considered have been partially studied. We believe that it is essential to analyze all of them as a whole in order to have a vision as close as possible to reality.

1.3 Hypothesis of the Model

The main idea is to consider the students’ perceptions about the help and support provided by parents, teachers, and the school, as well as their opinion of themselves, as feasible causes behind the bullying phenomenon. Teenagers at the end of secondary education experience physical and psychological changes that decisively influence their intrapersonal and interpersonal behaviors. Due to social pressure from friends and classmates, they often disregard the advice of their parents and teachers. For this reason, we consider the analysis from the student’s point of view to be a key aspect. Likewise, the connections between family variables and school bullying practice or victimization have been documented in different papers (Foster & Brooks-Gunn, 2013 ; Patton, et al., 2013 ). Distinct aspects of this relationship can be contemplated as key aspects in the students’ welfare.

To carry out this analysis, the following hypotheses are put forward, which we will explain below.

1.3.1 Student Relationships with Their Parents, and Bullying Victimization

Previous studies highlighted that the action of parents within families is fundamental when it comes to instilling values in their children and giving them support to recognize and solve problems (Oliveira, et al., 2020 ; Patton, et al., 2013 ). Some studies reveal that warm and supportive parental relationships are related to child’s social and emotional well-being even in the context of exposure to adversity (Kim-Cohen, et al., 2004 ; Murphy, et al., 2017 ). Similarly, Davis-Kean et al. ( 2021 ) point out that the parents’ educational support is directly related with their affective environment.

At that point, the perceived parental support is crucial to maintain self-esteem, the psychological well-being, including positive self-beliefs and reduced levels of internalizing symptoms (Boudreault-Bouchard, et al., 2013 ; Dutton, et al., 2020 ). Studies show that positive parental factors, such as support and positive parent-child relationships, help adolescents feel better about themselves, have positive feeling about themselves and have greater life satisfaction (Van der Kaap-Deeder, et al., 2017 ; Raboteg-Saric & Sakic, 2014 ). In some way, the former results point out that the role that families play in bullying prevention is fundamental (Arseneault, et al., 2010 ; Ttofi & Farrington, 2009 ). In addition, positive relationships and interaction between parents and children reduce the possibility of being bullied and play a role in the emotional adjustment of victims of bullying, making interventions for victims more successful (Lereya, et al., 2013 ; Zych, et al., 2019 ). In contrast, low social support and poor interpersonal relationships could increase the risk of students being victims of bullying (Hong, et al., 2012 ; Patton, et al., 2013 ).

In view of the above, it is reasonable to hypothesize:

H 1 : Parents´ educational support influences the emotional support they give their children.

H 2 : Parents´ emotional support influences the student’s self-efficacy.

H 3 : Parents´ emotional support influences the student’s positive feelings.

1.3.2 Self-efficacy, Positive Feeling, self-image and Bullying Victimization

Positive self-related cognitions, defined as children`s thoughts, beliefs, or attitudes about themselves, such as self-efficacy, self-respect or self-image are identified in the literature as being considered protective factors in the victimization of bullying (see Cook et al. ( 2010b ) for a complete revision).

Negative affectivity, i.e., having negative feelings about the environment and oneself is related to being introverted, having a low self-esteem and a negative self-image. The appearance of these children together with a nervous temperament means a risk of victimization (Hansen, et al., 2012 ). Several researchers have reported the positive association between low self-esteem and school bullying (Gendron, et al., 2011 ; Tsaousis, 2016 ).

With respect to their emotions and the perception that they have about themselves we consider students’ self-efficacy, positive feelings and self-image, and it can be hypothesized that.

H 4 : The student´s positive feelings are related with the child’s perception of being bullied.

H 5 : The student’s self-efficacy is related with the child’s perception of being bullied.

H 6 : The student’s self-image is related with the child’s perception of being bullied.

1.3.3 Sense of Belonging to the School, Teacher Support, and Bullying Victimization

The school environment and the relationship of its members with the student and the relation with bullying has been extensively studied (Azeredo, et al., 2015 ; Saarento, et al., 2015 ). The student-teacher relationship and the connections with school are relevant to bullying behavior (Gendron, et al., 2011 ; Raskauskas, et al., 2010 ).

Adolescents who feel less close to their school and their members are more likely to be victims of bullying and have less satisfaction with their lives (Varela, et al., 2019 , 2021 ). On the contrary, negative factors of the school environment (e.g., a lack of decisions and rules in the face of bullying by the management and teachers, a negative school climate perceived by students) can lead to an increase in the frequency of bullying, aggression, and victimization (Cook, et al., 2010b ; Goldweber, et al., 2013 ). Hence, we can consider the students’ feelings of belonging to the school, understood as the feeling of respect and acceptance that the students have toward the school, as a key aspect in this topic.

On the other hand, teachers play a key role in this process. Although there are studies that show discrepancies between how teachers and staff perceive bullying compared to their students (Bradshaw, et al., 2007 ; Waasdorp, et al., 2011 ), the influence of positive teacher-student relationships, as well as teacher involvement, have a great implication in bullying prevention (Espelage, et al., 2014 ; Saarento, et al., 2015 ). Teacher support is a protective factor in bullying (Álvarez-García, et al., 2015 ; Azeredo, et al., 2015 ), as they often play an important role in advising students how to respond to bullying. (Sokol, et al., 2016 ; Troop-Gordon & Ladd, 2015 ).

With respect to the student’s life at school, we consider that the following hypotheses can be formulated:

H 7 : A sense of belonging to the school is related with the child’s perception of being bullied.

H 8 : The teacher`s support is related with the child’s perception of being bullied.

1.3.4 Influence of Academic Success or Socioeconomic and Cultural Status of Students

The scientific literature shows that concrete indications about the influence of bullying on academic performance can be found (Huang, 2022 ; Riffle, et al., 2021 ). In this paper, we have considered a multigroup analysis to analyze the influence of the academic performance on the results obtained from the proposed SEM model. In a similar way, previous studies (see, among others, Allen et al. ( 2022 ) and Jain et al. ( 2018 ), pointed out the influence of the socioeconomic level. An additional analysis has been also performed considering the socioeconomic level as a differential factor.

Based on the hypotheses formulated above, a model based on structural equations is proposed and computed. SPSS and AMOS software were used to examine the variables and the fitness of the proposed model.

2.1 Dataset

This study analyses Spanish data from the 2018 Program for International Student Assessment (PISA). This program has been designed by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) to collect information about 15-year-old students in the participating countries and economies. A two-stage stratified sampling method was adopted (schools are first sampled and then students are sampled in the participating schools) (OECD, 2009 ). In schools were there were fewer than 42 age-eligible adolescents, all students aged 15 were selected.

In this study the sample size consists of 12,549 students. There were 6,505 females (51.84%) and 6,044 males (48.16%).

2.2 Measures

All the variables have been calculated from the PISA report published data. The latent and observable variables are summarized in Table 1 , note that some observable variables have been removed after the factorial structure. Following the practical suggestion from Kline ( 2015 ), the number of variables selected to represent latent variables vary from 3 to 5. The selection of the items in the measurement of each latent variables is based on literature review and theoretical foundations of SEM (Bollen, 1989 ). In some cases, we have suppressed some non-representative items by considering a mixed procedure which include factorial analysis and Cronbach alpha coefficient (Brown, 2006 ). It is important to bear in mind that some constructs can be more difficult to measure and, consequently demands a larger number of items for an adequate representation (Bollen, 1989 ).

Due to correlation problems, item BE2 has been defined negatively for the structure of the three observable variables of the sense of belonging to converge correctly. Also, an exploratory factor analysis was carried out with SPSS, with varimax rotation, in order to identify the adequacy of the items or indicators to each construct. Because of that, some indicators were deleted to properly define the internal structure of the model. Based on this, the constructs were defined by the items presented in Table 1 .

The academic performance has been defined with two feasible values: success and failure. We have estimated the levels of proficiency in Mathematics and Science (this has not been done in the case of language since this information is not available for the case of Spain) following the recommendations provided by PISA, which establishes six levels of proficiency. Each successive level is associated with increasingly difficult tasks passed by the student. The students are considered to have failed academic performance if they do not reach level 2 of proficiency in any of the subjects, this is the minimum level of proficiency established in the context of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (OECD, 2009 ).

On the other hand, we have constructed a new variable to represent the socioeconomic level. We have considered three levels (low, medium, and high) based on the Economic, Social and Cultural index (ESCS index) provided by PISA (OECD, 2019a ). We have considered that students with ESCS values lower than the 25th percentile constitutes the group with a low socioeconomic level and those included at the 75th percentile the group with a high socioeconomic level.

Based on the hypotheses formulated in the previous section, the proposed model is the one represented in Fig. 1 .

Structural Equation Model

2.3 Procedure

Four phases of data analysis were completed in accordance with the method advised by various authors (Frash & Blose, 2019 ). Firstly, a descriptive analysis using SPSS was used to determine the sample’s demographic characteristics. Secondly, to assess the suitability of the constructs’ dimensions, an exploratory factor analysis using varimax rotation was performed by means of SPSS. Thirdly, a confirmatory factor analysis was carried out using AMOS software to verify the measurement model. Fourthly, the structural model’s validity was examined. Finally, to confirm the relationships between the latent variables, the structural model’s coefficients were computed using AMOS software.

This section presents the analysis of the results obtained for the proposed model. The dataset has been analyzed by means of AMOS-IBM software.

The internal structure of latent variables and indicators has been assessed by means of factorial analysis. The internal consistency of the scales was measured through the Cronbach alpha coefficient, obtaining in all cases values greater than the 0.7 threshold.

The data normality was also analyzed, checking if the skewness coefficient was between − 1 and 1, and that the kurtosis coefficient was between − 7 and 7. Most of the items were normal, although there were some cases in which this hypothesis was not verified. On the other hand, multivariate normality was measured by means of the Martia test. The multivariate normality hypothesis was rejected because the value of the Martia test was 251.048 (> 5.99 for a significance level of 5%), the critical ratio being greater than the required 1.96. Thus, multivariate normality is not supported. However, since the sample is large enough, it has been decided to opt for the maximum likelihood estimation method, because this method facilitates the convergence of the estimates even in the absence of multivariate normality (Lèvy, et al., 2006 ).

The assessment of the proposed model has been carried out by analyzing the measurement model and the structural model. Reliability and validity have been used for the assessment of the measurement model. Regarding the first issue, the reliability of the items and the reliability of the constructs have been analyzed.

For the reliability of the items, it was found that the standardized factor loads were greater than the 0.707 threshold. This implies that the shared variance between the construct and its indicators is greater than the error variance. In this way, more than 50% of the variance of the observable variable (communality) is shared by the construct. In any case, some authors consider that a factor loading greater than 0.5 is also acceptable (Chau, 1997 ). All the standardized factorial loads are greater than 0.707, except those of items EF1, BE2 and BU3, which are greater than 0.5, so the reliability of the items is verified (Table 2 ).

The Cronbach alpha coefficient and the Composite Reliability (CR) coefficient were used for the assessment of the constructs’ reliability. All the Cronbach alpha coefficients were greater than 0.7, so the reliability is high. The minimum required value of the composite reliability coefficient is 0.7 (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994 ). In Table 2 , we can see that all the constructs have a CR coefficient greater than 0.7, so the reliability of the constructs is also verified.

Convergent validity and discriminant validity were analyzed for the assessment of the measurement model’s validity. The average variance extracted (AVE) was used for the analysis of the convergent validity. Values greater than 0.5 indicate that the construct explains more than the variance of its indicators (Hair, et al., 2014 ). In Table 2 , we can see that all the AVE values are greater than 0.5, except the value of the student’s self-efficacy construct. This value is practically on the limit, so we can say that the convergent validity is verified.

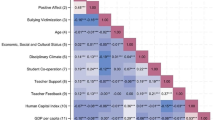

Regarding the discriminant validity, we must verify that the correlations between the constructs are not high or are at least lower than the square root of the AVE. The correlation matrix between the constructs is shown in Table 3 . In the main diagonal appears the square root of the AVE. We can see that all the correlations are lower than the square root of the AVE, so the discriminant validity is verified.

With respect to the assessment of the structural model, Table 4 shows that all the coefficients are significative, except the coefficient of the hypothesis H 3 . On the other hand, the R 2 values were greater than 0.1, exceeding this minimum value recommended by some authors, since lower values lack an adequate predictive level, even though significant (Hair, et al., 2014 ). For all these reasons, we can affirm that the validity of the structural model is verified.

The estimated structural model

The results of the structural model also reveal a good fit of the data. The χ 2 statistic shows if the discrepancy between the original data matrix and the reproduced matrix is significant or not. In this case, the p -value is lower than 0.05; therefore, this hypothesis is rejected. However, it should be noted that the value of the χ 2 statistic is highly influenced by the size of the sample, the complexity of the model and by the violation of the multivariate normality assumption. For these reasons, other measurements of global fit are used in AMOS software. In this sense, the remaining measures are consistent with a high degree of fit of the model (RMSEA = 0.042; CFI = 0.956; GFI = 0.950; NFI = 0.955; TLI = 0.952; AGFI = 0.940).

Finally, the total standardized effects have been obtained for analysing the influence of the constructs on bullying. The sense of not belonging is the construct that most influences bullying (total effect of 0.384). This variable is followed in order by student’s positive feeling, student’s self-image, teacher’s support, parents’ emotional support and parents’ educational support, with values of -0.095, -0.090, -0.062, -0.042 and − 0.026, respectively.

To identify if the results obtained from the SEM model are invariant with respect to socioeconomic and academic performance factors, two separate multigroup analyses have been computed, considering the tool developed in Gaskin ( 2016 ), which evaluates the differences between critical ratios.

Table 5 summarizes the results for multigroup analysis based on academic performance. We can observe that three relationships are invariant when the results for academic success and academic failure are compared. The relationship between parents’ emotional support and the students’ self-efficacy are higher for those students who are considered as successful in their academic performance. In a similar way, the intensity of the relation between students’ self-efficacy and the risk of being victim, is moderated by the values of academic performance. Finally, the relation between students’ self-image and the risk of being bullied is also affected by the academic performance.

Regarding the influence of socioeconomic values on the results from the SEM model, we do not find significant differences between the groups of low and medium socioeconomic levels. The only remarkable differences emerge with respect to teachers’ support and the risk of being bullied. In this case, those students with a lower socioeconomic level present a greater risk of being bullied. This must be explained by the fact that these group of students are most familiar with unsafe environments (Glew, et al., 2008 ).

4 Discussion

The results obtained from the computation of the SEM model point out that the feeling of help and support from their parents is a positive factor in the skill development oriented to resolving and overcoming difficult situations and fostering students’ positive feelings. Previous studies support this finding. Dutton et al. ( 2020 ) analyzed how perceived parental support influenced positive self-beliefs and is very important for the psychological well-being of adolescents across different cultural contexts.

Regarding positive feelings and the student’s self-image, both are negatively related with being a victim of bullying. However, the student’s self-efficacy and victimization has not been found to be significantly related. Most of the previous studies reported that positive self-related cognitions should be considered as protective factors and a negative association with the victimization of bullying (Cook, et al., 2010b ; Gendron, et al., 2011 ; Tsaousis, 2016 ). Considering intermediate variables, we can think that there is a relationship between parental educational and emotional support and bullying victimization. This agrees with many other works such as the systematic review by Nocentini et al. ( 2019 ).

With respect to the school environment, the support of the teaching staff and the security provided by the educational center have been found significant in preventing the victimization of bullying. The sense of belonging to the school is the construct that presents the most influence. The results found for the school environment are in line with other studies that showed how the students’ relationships with their teachers, as well as the involvement of teachers in the development process of adolescents are relevant to the phenomenon of bullying, mitigating its adverse effects (Espelage, et al., 2014 ; Gendron, et al., 2011 ; Raskauskas, et al., 2010 ; Saarento, et al., 2015 ). Likewise, feeling displaced and not close to the school is associated with being a victim of bullying (Varela, et al., 2019 , 2021 ).

Considering the theories on social-ecological models (Bronfenbrenner, 1979 ) and the environmental-fit (Eccles, et al., 1993 ), the bullying victimization is related with their closer environment. In this study, we have considered the students’ context, that is to say, the relations with their parents, teaching staff and school center, as this environment.

The findings suggest that, in the line pointed by the social learning theory, that a main part of the learning process is based on the observation and replication of some behaviors. In addition, this learning process is influenced by their attention and motivation and by the context found by the students.

When we considered the academic success and computed the model for two differentiated groups, all the relationships proposed in the initial model turn out to be significant (with the expected sign), including the relationship between self-efficacy and victimization, which was not in the original model. There are significant differences between the relationships of parental emotional support and the self-efficacy of the children and the victimization, being greater for the advantaged students. The opposite occurs when we compare the relationship between self-image and victimization. The relations between bullying and poor academic performance haven been analyzed is several works; see for instance Huang ( 2022 ), Nakamoto and Schwartz ( 2010 ), and Riffle et al. ( 2021 ), obtaining results in the same line as that described above.

Finally, the analysis performed for the three levels of the socioeconomic status permits seeing how the relations for the higher level are stronger than those obtained in the global model and those obtained for the lower socioeconomic levels. The metanalysis performed in Tippett and Wolke ( 2014 ) pointed out how those students with a lower socioeconomic level were more exposed to bullying victimization, which could be explained by the risk of being excluded (because of their limited resources).

5 Concluding Remarks

Peer violence in schools and bullying attitudes is a growing problem for most developed countries. Adolescents constitute a vulnerable group that demands care since certain traumatic experiences lived out in each human being’s life stage can determine his/her future development. Bullying attitudes have relevant consequences, resulting in disorders in those bullied students, even triggering suicide attempts.

This situation has captured the attention of many researchers, a large body of literature on this topic having been developed, including an analysis of causes and consequences, a classification of these activities, and metanalyses. This work is embedded in this context. We have proposed a quantitative analysis, based on Structural Equation Models, to study the relationships of the risk of being bullied with some variables of interest. We have considered the information published in PISA reports, considering the information provided by the students themselves that included self-perceptions about their behavior and experiences in their school stage.

In this paper, we have proposed and computed a quantitative model to detect significant relations of some relevant variables with the risk of being bullied. This ensemble of results could be valuable in the decision-making process. On some occasions the problem of bullying is increased by the lack of interest of educational centers in addressing this problem when it is in its initial phase and trying to silence it (this can be an embarrassing situation for the students or the institutions). Therefore, prevention programs have become an essential tool that must be accessible for teachers and parents to detect the problem as soon as possible. We show that the first warning signs can be obtained from the analysis of public datasets like the ones published in PISA reports.

Several limitations of this study need to be mentioned. One is only using self-reports by the student. Although it is very important to have the students’ perceptions, it would also be desirable to know the perceptions of the school and family environment, which would increase the validity of the results found. Furthermore, a key aspect to be considered as a part of the school environment is the response of the other students. It is important to explore if their response is passive, by defending their classmates or by cooperating with the bullies. Similarly, the consideration of the activity on the social networks should be a key point in future studies. And finally, it is important to point out that the cross-sectional research designs in the current study did not permit to analyze informing causal relationships between the variables.