- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Arts and Entertainment

- Performing Arts

How to Quote and Cite a Play in an Essay Using MLA Format

Last Updated: October 12, 2023

This article was co-authored by Christopher Taylor, PhD . Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014. This article has been viewed 389,862 times.

MLA (Modern Language Association) format is a popular citation style for papers and essays. You may be unsure how to quote and cite play using MLA format in your essay for a class. Start by following the correct formatting for a quote from one speaker or from multiple speakers in the play. Then, use the correct citation style for a prose play or a verse play.

Template and Examples

Quoting Dialogue from One Speaker

- For example, if you were quoting a character from the play Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, you would write, In Edward Albee's Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? , the character Honey says...

- For example, if you are quoting the character George from the play Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? by Edward Albee, you would write, “George says,…” or “George states,…”.

- For example, if you are quoting from Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? , you would write: Martha notes, "Truth or illusion, George; you don’t know the difference."

- For example, if you were quoting from Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure , you would write: Claudio states “the miserable have no other medicine / But only hope.”

Quoting Dialogue from Multiple Speakers

- You do not need to use quotation marks when you are quoting dialogue by multiple speakers from a play. The blank space will act as a marker, rather than quotation marks.

- MARTHA. Truth or illusion, George; you don’t know the difference.

- GEORGE. No, but we must carry on as though we did.

- MARTHA. Amen.

- Verse dialogue is indented 1 ¼ inch (3.17cm) from the left margin.

- RUTH. Eat your eggs, Walter.

- WALTER. (Slams the table and jumps up) --DAMN MY EGGS--DAMN ALL THE EGGS THAT EVER WAS!

- RUTH. Then go to work.

- WALTER. (Looking up at her) See--I’m trying to talk to you ‘bout myself--(Shaking his head with the repetition)--and all you can say is eat them eggs and go to work.

Citing a Quote from a Prose Play

- If you are quoting dialogue from one speaker, place the citation at the end of the quoted dialogue, in the text.

- If you are quoting dialogue from multiple speakers, place the citation at the end of the block quote.

- For example, you may write: “(Albee…)” or “(Hansberry…)”

- For example, you may write, “(Albee, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? ...).”

- If you have mentioned the title of the play once already in an earlier citation in your essay, you do not need to mention it again in the citations for the play moving forward.

- For example, you may write, “(Albee 10; act 1).

- If you are including the title of the play, you may write: “(Albee, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? 10; act 1).”

Citing a Quote from a Verse Play

- For example, if the quote appears in act 4, scene 4 of the play, you will write, “(4.4…)”.

- For example, if the quote appears on lines 33 to 35, you will write, “(33-35).”

- The completed citation would look like: “(4.4.33-35)”.

Expert Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://penandthepad.com/quote-essay-using-mla-format-4509665.html

About This Article

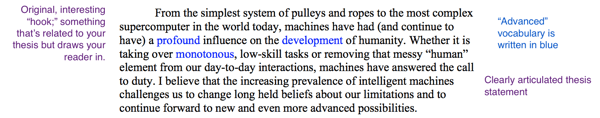

To quote and cite a play in your essay using MLA format, start by referencing the author and title of the play in the main body of your essay. Then, name the speaker of the quote so it’s clear who’s talking. For example, write, “In Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? the character Honey says…” After introducing the quote, frame the dialogue with quotation marks to make it clear that it’s a direct quote from a text. If your dialogue is written in verse, use forward slashes to indicate each line break. For more tips from our English co-author, including how to quote dialogue between multiple speakers in your essay, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Did this article help you?

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

Generate accurate MLA citations for free

- Knowledge Base

- How to cite Shakespeare in MLA

How to Cite Shakespeare in MLA | Format & Examples

Published on January 22, 2021 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on March 5, 2024.

The works of Shakespeare, like many plays , have consistently numbered acts, scenes, and lines. These numbers should be used in your MLA in-text citations, separated by periods, instead of page numbers.

The Works Cited entry follows the format for a book , but varies depending on whether you cite from a standalone edition or a collection. The example below is for a standalone edition of Hamlet .

If you cite multiple Shakespeare plays in your paper, replace the author’s name with an abbreviation of the play title in your in-text citation.

| MLA format | Shakespeare, William. . Edited by Editor first name Last name, Publisher, Year. |

|---|---|

| Shakespeare, William. . Edited by G. R. Hibbard, Oxford UP, 2008. | |

| (Shakespeare 5.2.201–204) or ( 1.2.321–324) |

Scribbr’s free MLA Citation Generator can help you quickly and easily create accurate citations.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Citing a play from a collection, citing multiple shakespeare plays, quoting shakespeare in mla, frequently asked questions about mla citations.

If you use a collection of all or several of Shakespeare’s works, include a Works Cited entry for each work you cite from it, providing the title of the individual work, followed by information about the collection.

Note that play titles remain italicized here, since these are works that would usually stand alone.

| MLA format | Shakespeare, William. . , edition, edited by Editor first name Last name, Publisher, Year, pp. Page range. |

|---|---|

| Shakespeare, William. . , 3rd ed., edited by Stephen Greenblatt, W. W. Norton, 2016, pp. 1907–1971. | |

| (Shakespeare 3.2.20–25) or ( 3.2.20–25) |

If you cite several works by Shakespeare , order them alphabetically by title, and replace “Shakespeare, William” with a series of three em dashes after the first one.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

If you cite more than one Shakespeare play in your paper, MLA recommends starting each in-text citation with an abbreviated version of the play title, in italics. A list of the standard abbreviations can be found here ; don’t make up your own abbreviations.

Introduce each abbreviation the first time you mention the play’s title, then use it in all subsequent citations of that play.

Don’t use these abbreviations outside of parentheses. If you frequently mention a multi-word title in your text, you can instead shorten it to a recognizable keyword (e.g. Midsummer for A Midsummer Night’s Dream ) after the first mention.

Shakespeare quotations generally take the form of verse or dialogue .

Quoting verse

To quote up to three lines of verse from a play or poem, just treat it like a normal quotation. Use a forward slash (/) with spaces around it to indicate a new line.

If there’s a stanza break within the quotation, indicate it with a double forward slash (//).

If you are quoting more than three lines of verse, format it as a block quote (indented on a new line with no quotation marks).

Quoting dialogue

Dialogue from two or more characters should be presented as a block quote.

Include the characters’ names in block capitals, followed by a period, and use a hanging indent for subsequent lines in a single character’s speech. Place the citation after the closing punctuation.

Oberon berates Robin Goodfellow for his mistake:

No, do not use page numbers in your MLA in-text citations of Shakespeare plays . Instead, specify the act, scene, and line numbers of the quoted material, separated by periods, e.g. (Shakespeare 3.2.20–25).

This makes it easier for the reader to find the relevant passage in any edition of the text.

If you cite multiple Shakespeare plays throughout your paper, the MLA in-text citation begins with an abbreviated version of the title (as shown here ), e.g. ( Oth. 1.2.4). Each play should have its own Works Cited entry (even if they all come from the same collection).

If you cite only one Shakespeare play in your paper, you should include a Works Cited entry for that play, and your in-text citations should start with the author’s name , e.g. (Shakespeare 1.1.4).

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2024, March 05). How to Cite Shakespeare in MLA | Format & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved June 10, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/mla/shakespeare-citation/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to cite a play in mla, how to cite a poem in mla, how to cite a book in mla, what is your plagiarism score.

Dr. Mark Womack

How to Quote Shakespeare

Title and reference format.

Richard III or Othello

Twelfth Night (1.5.268–76)

In 3.1, Hamlet delivers his most famous soliloquy.

“Periods and commas,” says Dr. Womack, “ always go inside quotation marks.”

Prose Quotations

The immensely obese Falstaff tells the Prince: “When I was about thy years, Hal, I was not an eagle’s talon in the waist; I could have crept into any alderman’s thumb ring” (2.4.325–27).

In Much Ado About Nothing , Benedick reflects on what he has overheard Don Pedro, Leonato, and Claudio say: This can be no trick. The conference was sadly borne. They have the truth of this from Hero. They seem to pity the lady. It seems her affections have their full bent. Love me? Why, it must be requited. I hear how I am censured. They say I will bear myself proudly if I perceive the love come from her; they say too that she will rather die than give any sign of affection. (2.3.217–24)

Verse Quotations

Berowne’s pyrotechnic line “Light, seeking light, doth light of light beguile” is a text-book example of antanaclasis (1.1.77).

Claudius alludes to the story of Cain and Abel when describing his crime: “It hath the primal eldest curse upon’t, / A brother’s murder” (3.3.37–38).

Jaques begins his famous speech by comparing the world to a theater: All the world’s a stage And all the men and women merely players: They have their exits and their entrances; And one man in his time plays many parts, His acts being seven ages. (2.7.138–42)

He then proceeds to enumerate and analyze these ages.

Dialogue Quotations

The Christians in Venice taunt Shylock about his daughter’s elopement: SHYLOCK. She is damned for it. SALARINO. That’s certain, if the devil may be her judge. SHYLOCK. My own flesh and blood to rebel! SOLANIO. Out upon it, old carrion! Rebels it at these years? SHYLOCK. I say my daughter is my flesh and my blood. SALARINO. There is more difference between thy flesh and hers than between jet and ivory, more between your bloods than there is between red wine and Rhenish. (3.1.29–38)

From their first conversation, Lady Macbeth pushes her husband towards murder: MACBETH. My dearest love, Duncan comes here tonight. LADY MACBETH. And when goes hence? MACBETH. Tomorrow, as he purposes. LADY MACBETH. O, never Shall sun that morrow see. (1.5.57–60)

- How to Cite

- Language & Lit

- Rhyme & Rhythm

- The Rewrite

- Search Glass

The Correct Way to Cite Shakespearean Works

If you quote directly or paraphrase from a source, you must cite the source within the text. This can be problematic when you are citing a classical work such as a Shakespearean play, because classical works are published in so many different formats that page numbers become meaningless. Luckily, both the Modern Language Association (MLA) and the American Psychological Association (APA) set guidelines for the proper in-text citation of Shakespearean plays.

Citing Shakespeare in MLA Format

List the abbreviation for the title of the play you are citing. The MLA lists abbreviations for all plays; see the reference list of this article for more information. The abbreviation for the title of the play should appear in italics.

List the act, scene and lines that you are referring to. These should be separated by periods. Enclose your citation in parentheses. For example:

(Mac. 1.3.14-17) refers to Act 1, Scene 3, Lines 14 to 17 of "Macbeth."

Omit the abbreviation for the title if the play you are referring to is clear from the context of your paper. In this case, the citation would simply appear as

follows: (1.3.14-17)

Format your reference list entry in the following format:

Author. Title of Play. Name of Editor. City of Publication, Publisher, Year of Publication. Medium of Publication. For example: Shakespeare, William. Macbeth. Ed. James Smith. Boston, English Play Press, 2010. Print. Be sure to italicize the name of the play.

Citing Shakespeare in APA Format

List "Shakespeare" as the author's name, followed by a comma.

List the year of translation, followed by a comma, if translated. For example:

trans. 2010,

List the act, scene, and lines you are citing, separated by periods. For example:

Enclose the entire citation within parentheses. For example:

(Shakespeare, trans. 2010, 1.3.14-17).

Only use this if the play you are citing is obvious and has been mentioned in your paper. If the play appears in the original Shakespearean English, you need only give the year of publication. In this case, omit "trans." from your citation. For example:

(Shakespeare, 2010, 1.3.14-17).

Author. (Year). Title. (Translator.). City, State of Publication: Publisher. (Original work published year). For example: Shakespeare, W. (2010). Macbeth. (B. Smith, Trans.). Boston, MA: English Play Press. (Original work published 1699).

Be sure to italicize the name of the play. If the publication appears in the original Shakespearean, omit translation information form your citation. For example:

Shakespeare, W. (2010). Macbeth. Boston, MA: English Play Press. (Original work published 1699).

Need help with a citation? Try our citation generator .

- Louisiana State University: MLA Citation of Shakespeare

- Carson-Newman College: List of MLA Abbreviations for Shakespearean Titles

- Pursue Online Writing Lab: APA Abbreviations

- Purdue Online Writing Lab: APA Reference List for Books

How to Use Shakespeare Quotes

- Shakespeare's Life and World

- Best Sellers

- Classic Literature

- Plays & Drama

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

- M.B.A, Human Resource Development and Management, Narsee Monjee Institution of Management Studies

- B.S., University of Mumbai, Commerce, Accounting, and Finance

You can make your essays interesting by adding a famous quote, and there is no source more illustrious than Shakespeare to quote! However, many students feel intimidated at the thought of quoting Shakespeare. Some fear that they may use the quote in the wrong context; others may worry about using the quote verbatim and missing the precise meaning, owing to the archaic Shakespearean expressions. Navigating these difficulties is possible, and your writing may be greatly enhanced if you use quotes from Shakespeare with skill and attribute the quotes correctly.

Find the Right Shakespeare Quote

You can refer to your favorite resources, found in your school library, a public library, or your favorite content destinations on the Internet. With all theater quotations, make sure that you use a reliable source that gives you complete attribution, which includes the name of the author, the play title, the act , and the scene number.

Using the Quote

You will find that the language used in Shakespeare plays have archaic expressions that were used during the Elizabethan era . If you are unfamiliar with this language, you run the risk of not using the quote correctly. To avoid making mistakes, be sure to use the quote verbatim—in exactly the same words as in the original source.

Quoting From Verses and Passages

Shakespeare plays have many beautiful verses; it's up to you to find an appropriate verse for your essay. One way to ensure an impactful quote is to ensure that the verse you choose does not leave the idea unfinished. Here are some tips for quoting Shakespeare:

- If you are quoting verse and it runs longer than four lines, you must write the lines one below the other as you do when you write poetry. However, if the verse is one to four lines long, you should use the line division symbol (/) to indicate the beginning of the next line. Here is an example: Is love a tender thing? It is too rough, / Too rude, too boisterous; and it pricks like thorn ( Romeo and Juliet , Act I, Sc. 5, line 25).

- If you are quoting prose , then there is no need for line divisions. However, to effectively represent the quote, it is beneficial to first provide the contextual relevance of the quote and then proceed to quote the passage. Context helps your reader to understand the quote and to better grasp the message that you wish to convey by using that quote, but you should exercise caution when deciding how much information to supply. Sometimes students give a brief synopsis of the play to make their Shakespeare quote sound relevant to their essay, but it is better to provide short, focused background information. Here is a writing example in which a small amount of context, provided before a quote, improves its impact:

Miranda, daughter of Prospero, and the King of Naples' son, Ferdinand, are to get married. While Prospero is not optimistic about the arrangement, the couple, Miranda and Ferdinand, are looking forward to their union. In this quote, we see the exchange of viewpoints between Miranda and Prospero: "Miranda: How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world, That has such people in't! Prospero: 'Tis new to thee." ( The Tempest , Act V, Sc. 1, lines 183–184)

Attribution

No formal Shakespeare quote is complete without its attribution. For a Shakespeare quote, you need to provide the play title, followed by act, scene, and, often, line numbers. It is a good practice to italicize the title of the play.

In order to ensure that the quote is used in the right context, it is important to reference the quote appropriately. That means you must mention the character's name who made the statement. Here is an example:

In the play Julius Caesar , the relationship of the husband-wife duo (Brutus and Portia), brings out the conniving nature of Portia, in startling contrast to Brutus' gentleness: "You are my true and honourable wife;/As dear to me as are the ruddy drops/That visit my sad heart." ( Julius Caesar , Act II, Sc. 1)

Length of the Quote

Avoid using long quotes. Long quotes dilute the essence of the point. In case you have to use a specific long passage, it is better to paraphrase the quote.

- A Complete List of Shakespeare’s Plays

- Quotes From Shakespeare's 'The Tempest'

- 'The Tempest' Summary for Students

- 'The Tempest' Overview

- Overview of Shakespeare's 'The Tempest'

- 'The Tempest' Characters: Description and Analysis

- Shakespeare's New Year and Christmas Quotes

- A Guide to Using Quotations in Essays

- A Collection of Shakespeare Lesson Plans

- 10 Shakespeare Quotes on Tragedy

- 'The Tempest' Quotes Explained

- Top Quotes From Shakespeare

- Romantic Shakespeare Quotes

- 'The Tempest' Summary

- 'The Tempest' Themes, Symbols, and Literary Devices

- How to Speak Shakespearean Verse

How to Write a Scene: The Definitive Guide to Scene Structure

by Joe Bunting | 0 comments

Once you have a great story idea, the next step is to write it. But do you want to take your brilliant idea and then write a book that bores readers and causes them to quit reading your book?

Of course not. That's why you need to learn how to write great scenes.

Scenes are the basic building block of all storytelling. How do you actually write them, though? And even more, how do you write the kind of scenes that both can keep readers hooked while also building to the powerful climax you have planned for later in the story?

In this post, you'll learn what a scene actually is. You'll explore the six elements every scene needs for it to move the story forward. Then, you'll learn how to do the work of actually putting a scene together, step-by-step.

We'll look at some of the main scene types you need for the various types of stories, and we'll also look at some scene examples so you can better understand how scenes work. Finally, we'll put it all together with a practice exercise.

Table of Contents

Want to jump ahead? Here's a table of contents for this article:

What Is a Scene? The 4 Criteria of a Scene Scene Writing and “Show, Don't Tell” Scene Structure: The 6 Steps to Scene Structure Scene Structure Examples Practice Exercise

What Is a Scene? Scene Definition

A scene (in a story) is an event that occurs within a narrative that takes place during a specific time period and has a beginning and an end.

A scene is a story event, in other words, or a single unit of storytelling. It is the bedrock of every kind of narrative, from a novel, film, memoir, short story, theatrical play, and graphic novel.

Scenes can vary in length, but they tend to be 500 to 2,500 words long. The average book or film has fifty to seventy scenes.

5 Criteria of a Scene

For a section of narrative to be considered a scene, it must meet several criteria.

- A story event . The scene must contain at least one story event.

- A change. A character begins the scene believing one thing, feeling one way, or doing one thing, but by the end of the scene they’re believing, feeling, or doing something else.

- One period of time (e.g. a few minutes in one day). Most scenes will be just a few minutes in one day.

- (In film) One setting . Novels can bend this, but in film, scenes take place in one setting.

- Contains the six elements of plot: exposition, inciting incident, rising action, dilemma, climax, and denouement. We'll discuss these elements in detail below.

How “Show Don't Tell” Impacts Writing Scenes: Show Your Scenes, Tell Your Transitions

One quick thing to note: you might have heard of the common writing advice to “Show, Don't Tell.”

Show, Don’t Tell refers to showing the reader what happens in a story using dialogue, action, or description rather than telling the reader with inner monologue or exposition/narrative.

Scenes are, by their nature, shown. You the writer are showing the reader what is happening.

That's why good writers find the most important, most dramatic pieces in their story to show in scenes.

Then, they use telling to link between scenes and give the context, information, and backstory that's still important but not necessarily dramatic.

In other words, show your scenes, tell your transitions. If you don't, if you tell your most important pieces and show your least important, least dramatic moments, you'll end up with jumbled scenes and a jumbled story in general.

What Are the Elements of Scene? 6 Steps to Scene Structure

At The Write Practice, we teach a story structure framework called The Write Structure. It's a universal and timeless way of thinking about story that writers have been applying for thousands of years. (Read our master plot post here .)

Within this framework, there are six elements of plot. These elements don't just occur in every story. They also occur in every scene.

So if you want to write a good scene, make sure that it has each of these six structural elements. You can even use these as steps in your scene writing.

Step 1. Exposition: Set the Scene

First, set the scene.

Where are we? Who are we with? What should we the audience be seeing or imagining?

Set the scene, usually with description or action , to ground the reader's experience.

Learn more in our full exposition guide here .

Step 2. Inciting Incident: Start the Drama

The inciting incident is an event in a scene that puts the characters into a new situation, upsetting the status quo and beginning the scene's movement.

That situation is the key ingredient to the inciting incident. It can be something going wrong, a complication that arises, or even something going really well. Check out the examples below to get more ideas for your inciting incident.

The inciting incident doesn't have to be a big thing. That comes later, in the climax. It can be subtle, but the point is that it builds into a much larger thing.

The key point about the inciting incident of a scene is that it must occur early in a scene, usually within the first five paragraphs.

Don't get me wrong, you still need to set the scene with exposition. But your exposition will either follow the inciting incident or quickly give way to the inciting incident.

You can learn more in our full inciting incident guide here .

Step 3. Rising Action: Throw Rocks at Your Characters

You know that writing advice to get your characters up a tree, then throw rocks at them? This is rock-throwing time.

Your inciting incident begins the action and conflict of the scene, but the rising action is where most of the action and conflict builds and takes place.

This will often be the largest section of your scene, and builds directly into the dilemma.

Here you start raising the stakes and begin building towards the story’s climactic moment. It’s important that your audience know exactly what’s at risk here, so work to reveal what's important to your characters here (e.g. their lives, their relationship, their identity) and why that is at risk.

Learn more in our full rising action guide here .

Step 4. Dilemma: The Heart of Your Scene

This is the most important (and overlooked) element of every great scene, and it's what all the action in your scene has been building toward.

A dilemma is when a character is put into a situation where they're stuck and have to make a difficult choice with real consequences.

Here are some example choices:

- Go through the wardrobe into the magical portal or shut the door and miss out

- Take the red pill or the blue pill

- Call the cute crush or stay alone forever

- Fight or flight

- Quit or persevere

- Do what you're told or do what you want

- Share something vulnerable or keep everyone at a distance

These are the dilemmas that drama is made out of, and in some form or other, they belong in every single scene in your story. Together with the previous scenes and the scenes that follow, these are the moments that create the character arc the drives the story forward.

Learn more in our full dilemma guide here .

5. Climax: Create the Moment Out of Highest Action

Coming immediately after the dilemma, the climax shows the consequences of your characters' choices. As such, it is the moment of highest action in the scene.

Taking our example choices from above, here's what might happen next:

- They go through wardrobe and arrive in a magical kingdom

- They take the red pill and wake up in a creepy, dystopian world with a tube down their throats

- They call the cute crush and then crash and burn

- They fight and are mauled by a giant bear

- They quit, only to be visited by an angel who offers to show them the consequences of quitting

- They do what they want and get into a fight with a dragon which results in burning down the village

- They decide to share and finally feel truly accepted and known for the first time in their lives

You see how it works, right? You start the movement, raise the stakes, create a dilemma, and pay it all off with a climax full of dramatic energy.

If you did it right, this is either the best or worst moment in your scene. This is also where to insert any plot twists you can think of.

Learn more in our full climax guide here .

Step 6. Denouement: Pause to Take Things In

But your scene isn't over just yet. Finally, you have to create a brief pause, often only a paragraph or three, to allow the audience to take in what just happened and prepare the ground for the next scene.

If the exposition is the “before,” the denouement, also called the resolution, is the “after.”

You don't need much writing here, just a few paragraphs, but this element is key to the rhythm of your storytelling.

Learn more in our full denouement guide here .

Scene Structure Examples

Now that you know the steps, let's look at a few examples from popular scenes to better understand how this works.

How to Train Your Dragon: Opening Scene Structure

For reference, you can watch the scene here:

I love this scene and this film as a whole (the books are great too!). It instantly sets up not just the stakes of the scene, but the story as a whole, and in general, has nearly perfect structure.

Let's break it into the six elements of plot that we just discussed.

Exposition: “This is Berk.” Bucolic, pastoral, peaceful. Narrated by Hiccup, the viewpoint character.

Inciting incident: Actually nope, there are dragons stealing the sheep.

Rising action: Dragons burn things, people fight dragons, we meet the story's cast of characters, and most of all, we get to know Hiccup, the protagonist, who really wants to prove himself. But Hiccup is told he's not allowed to fight the dragons.

Dilemma: To do what he's told, stay put, and risk being looked down on his whole life OR to do what he wants, go fight with his fancy machine, and risk dying and/or humiliating himself?

Climax: Hiccup does what he wants, hits a dragon, gets into a fight with another dragon, and then burns down most of the village.

Denouement: No one believes he hit the dragon, and he is humiliated in front of the village.

Note especially the location of the dilemma, which occurs about halfway through the scene and comes to a head immediately. It's subtle, implied more than it is spelled out specifically, and yet it creates the drama that follows.

Frozen: Climactic Scene Structure

For reference, you can watch the scene here ( spoiler alert in case you somehow have never seen this film!):

I like to use this scene because it perfectly displays how a dilemma works.

Exposition: Princess Anna is dying, about to become frozen after being struck by Princess Elsa's magic.

Inciting Incident: With an act of true love, she can be cured, and Kristoff is running toward her to give her the “kiss of true love.”

Rising Action: There's a storm, so this is all very difficult. Oh, and Prince Hans is about to kill her sister.

Dilemma: Princess Anna looks both ways, not sure what to choose. Does she run to Kristoff and save herself but allow her sister to be killed OR does she save her sister and sacrifice herself?

Climax: She chooses to save her sister, running to stop Prince Hans and freezing in the process. The storm immediately ceases.

Denouement: Princess Anna herself supplied the act of true love, removing the magic's curse and restoring her to life.

Again, pay special attention to the dilemma, which lasts for just a few seconds as she pauses, looking both ways, trying to decide. The stakes couldn't be higher (which is good because this is the climax of the story), and her choice immediately results in not just the climax of the scene, but the climax of the entire story.

How to Write a Great Scene Every Time

Writing compelling scenes doesn't require you to be a genius or know everything there is about writing.

You just need to follow the six scene tasks: exposition, inciting incident, rising action, dilemma, climax, and denouement.

If you just do that, you'll be able to reliably craft a perfect scene that, when brought together, will end up with an amazing story.

So go get writing!

Which of these six steps and elements do you find easiest? which is most difficult or confusing? Let us know in the comments .

Now that you know how a perfect scene works, let's put it to practice. Today, I have two scene prompts for your practice:

- Study a scene from one of your favorite books or films, finding the six elements of plot.

- Outline a scene you've written or a new scene using the six elements of plot.

Take fifteen minutes to practice. Once you've created your outline, share it in the Pro Practice Workshop .

And if you share, be sure to give feedback to at least three other writers.

Happy writing!

Joe Bunting

Joe Bunting is an author and the leader of The Write Practice community. He is also the author of the new book Crowdsourcing Paris , a real life adventure story set in France. It was a #1 New Release on Amazon. Follow him on Instagram (@jhbunting).

Want best-seller coaching? Book Joe here.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Submit Comment

Join over 450,000 readers who are saying YES to practice. You’ll also get a free copy of our eBook 14 Prompts :

Popular Resources

Book Writing Tips & Guides Creativity & Inspiration Tips Writing Prompts Grammar & Vocab Resources Best Book Writing Software ProWritingAid Review Writing Teacher Resources Publisher Rocket Review Scrivener Review Gifts for Writers

Books By Our Writers

You've got it! Just us where to send your guide.

Enter your email to get our free 10-step guide to becoming a writer.

You've got it! Just us where to send your book.

Enter your first name and email to get our free book, 14 Prompts.

Want to Get Published?

Enter your email to get our free interactive checklist to writing and publishing a book.

How to Write Scenes: Structure, Examples, and Definitions

What is a scene.

Scenes are the building blocks of our stories. These STORY UNITS dramatize definable VALUE SHIFTS for the AVATARS (or characters) and their CONTEXT (or setting). The value shifts that occur in each working scene of the story incrementally build the global arcs of change.

Many writers define scenes by chapter breaks or changes in location or the AVATARS at the center of the conflict. While these transitions may coincide with a value shift, without a consistent definition of when a scene starts or ends, we cannot talk about a story’s scenes consistently or examine masterwork scenes to improve our own scene work.

Download the Math of Storytelling Infographic

In the Story Grid Universe, we understand that stories are about life-altering change that happens when the protagonist makes an active choice in response to the global INCITING INCIDENT . As the building blocks of story, scenes dramatize smaller events and changes that when combined create the experience of the whole story. Executing effective scenes is one of the most important skills for story writers to master.

Scene Structure

We describe and identify whole scenes by using the Story Grid SCENE EVENT SYNTHESIS. This is a one-sentence summary that helps us analyze our own scenes or those in masterworks we seek to emulate. The Synthesis includes the following components.

- Ending value: This is how things stand at the end of the scene.

- Outcome of ABOVE THE SURFACE initial strategy: This describes the result of the protagonist’s initial attempt to reach their scene goal.

- ON THE SURFACE CLIMAX: This is the protagonist’s choice in response to the CRISIS .

- Tradeoff of the CRISIS : This is what the protagonist risks with their choice.

The summary captures what happens after the protagonist’s initial strategy succeeds or fails and the protagonist acts in the CLIMAX , despite the potential risks of the CRISIS tradeoff.

Scenes are different from TROPES or SEQUENCES . A trope is a change in microstrategies that build to a value shift of the scene. A sequence is an irreversible change in stakes that builds from the value shifts in scenes.

Scene Function

Scenes allow storytellers to show the incremental change over time as the protagonist makes sense of and assigns meaning to the unexpected event that kicks off the story. Each scene presents a manifestation or instance of that global INCITING INCIDENT and the global CRISIS to communicate the CONTROLLING IDEA of the story. This also means that every scene should illuminate an aspect of SAM ’s problem from the NARRATIVE PATH .

Scene Organization

Scenes are made up of a series of TROPES . The microstrategies in tropes are used by the AVATARS to navigate the problems presented in each scene. The FIVE COMMANDMENTS OF STORYTELLING are dramatized through the trope microstrategies.

The inciting incident of a scene catalyzes change with an unexpected event that is complicated by another unexpected event, which we call the turning point progressive complication. That event begins to turn the scene and forces the protagonist to face a crisis. When the protagonist implements their active choice in the climax, and they experience the immediate effects of the value shift or change in the resolution of the scene.

What are the key features of a Scene?

- FIVE COMMANDMENTS OF STORYTELLING . Each scene in a story will include an INCITING INCIDENT , TURNING POINT PROGRESSIVE COMPLICATION , CRISIS , CLIMAX , and RESOLUTION .

- Beyond the surface VALUE SHIFTS . Each scene contains a value shift, which describes a universal change from the beginning of the scene to the end of the scene.

- Above the surface essential tactics. The protagonist is forced to act or respond to crisis when above the surface essential tactic fails or succeeds and is not what they expected.

- On the surface action. The change in value comes as the result of on the surface climax action in response to the crisis.

How do we identify Scenes within masterworks?

A scene should have a defined value shift. The scene will not end until the value has shifted.

Writers should look for a change in value throughout the scene. One way to find the value shift is to identify the place in the story where the question raised by the inciting incident is resolved. Once the question has been resolved, the protagonist should have undergone a value shift.

We analyze scenes through the STORY GRID 624 ANALYSIS, which helps us identify key features in every scene that we should study.

What are some examples of Scenes?

Hamilton by lin manuel miranda, scene 1 (global inciting incident).

Scene Event Synthesis

Hamilton is recognized when, after his last relative dies, he overcomes his circumstances by fending for himself despite the risk of failure.

Five Commandments

Inciting Incident : Causal. When Hamilton is ten years old, his father abandons him and his mother.

Turning Point Progressive Complication : Active. Hamilton’s cousin commits suicide, leaving the young man alone and penniless.

Crisis : Best Bad Choice. Hamilton can fend for himself or accept a life of squalor.

Climax : Hamilton decides to educate himself. He borrows and reads books while working for his late mother’s landlord. He publishes his writing.

Resolution : A group of men are impressed by Hamilton’s writing about the hurricane. They offer to pay for his travel and college.

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen, Scene 34 (Global Turning Point Progressive Complication)

Darcy is devastated when Elizabeth insults his character after he asked her why she would not marry him despite knowing that any answer she gave would hurt him.

Inciting Incident : Causal. Darcy pays another visit to Elizabeth knowing she is alone and unwell.

Turning Point Progressive Complication : Active. Elizabeth refuses Darcy’s proposal of marriage.

Crisis : Best Bad Choice. Should Darcy ask Elizabeth why she is refusing him and risk deep personal pain or blow Elizabeth off as being incapable of making a rational and beneficial choice?

Climax : Darcy asks her why she won’t marry him.

Resolution : Elizabeth tells him in no uncertain terms why she won’t marry him and insults him many times in the process.

The Silence of the Lambs by Thomas Harris, Scene 59 (Global Climax)

Clarice preserves life when she trusts herself by going down the steps to find Buffalo Bill despite knowing that she is walking into a trap.

Inciting Incident : Causal. Clarice knocks on the door of Buffalo Bill’s house to ask him questions about the death of Fredricka Bimmel.

Turning Point Progressive Complication : Revelatory. Clarice realizes that the man who had called himself Jack Gordon is really Buffalo Bill.

Crisis : Best Bad Choice. Should she go down the steps when she knows it can only be a trap or call the FBI for backup?

Climax : Clarice goes down the steps to find and kill Buffalo Bill.

Resolution : Cathrine Martin is saved.

Additional Scene Resources:

- Story Grid: What Good Editors Know by Shawn Coyne

- Story Grid 101: The Five First Principles of the Story Grid Methodology by Shawn Coyne

- The Five Commandments of Storytelling by Danielle Kiowski

Share this Article:

🟢 Twitter — 🔵 Facebook — 🔴 Pinterest

Sign up below and we'll immediately send you a coupon code to get any Story Grid title - print, ebook or audiobook - for free.

Level Up Your Craft Newsletter

Stack Exchange Network

Stack Exchange network consists of 183 Q&A communities including Stack Overflow , the largest, most trusted online community for developers to learn, share their knowledge, and build their careers.

Q&A for work

Connect and share knowledge within a single location that is structured and easy to search.

Citing a Shakespearean Play: What Constitutes a "Line"?

According to many sources that I've searched, it seems that the in-line citations for dramatic works, such as Shakeaspearean plays, are cited in the following form: act.scene.line(s). So for example, Act I Scene I lines 20-22 would be cited like so:

"some quote in here," (I.i.20-22).

But my question is the following: what constitutes a line? Do the narrator's lines count as lines? For example, I want to cite Hamlet Act I Scene I, and it begins like so:

Act I SCENE I. Elsinore . A platform before the castle. FRANCISCO at his post. Enter to him BERNARDO BERNARDO Who's there? FRANCISCO Nay, answer me: stand, and unfold yourself. BERNARDO Long live the king!

So if I were to cite Bernardo's first line ("Who's there?"), which of the following would I count as line 1?

- "SCENE I. Elsinore. A platform before the castle."

- "FRANCISCO at his post. Enter to him BERNARDO"

- I think when an actor says I forgot my line , it's normally a reference to one continuous speech within the play/film (uninterrupted by utterances by other characters). Which could be multiple sentences taking up several "lines" in the written version (a variable number of lines, since usually nothing in the "original" text dictates where the line-breaks should occur). – FumbleFingers Jan 17, 2016 at 14:38

- 2 @FumbleFingers: in Shakespeare's plays, the original text is generally iambic pentameter, and breaks naturally into lines. There are some parts of some plays written in prose, and I don't know whether the line counts are consistent across different editions there. – Peter Shor Jan 17, 2016 at 14:40

- 4 Stage directions are not a "narrator". These lines are not spoken on stage. – TimR Jan 17, 2016 at 14:40

- @Peter: Probably most of the "great quotable speeches" we tend to focus on are indeed iambic pentameter, but off the top of my head I'd have thought it's unlikely most of the total text of all Shakespeare's output conforms to that constraint (esp if we exclude the sonnets). – FumbleFingers Jan 17, 2016 at 14:43

- 1 @FumbleFingers: it looks like the majority of most of Shakespeare plays are iambic pentameter, but there are only five that are entirely iambic pentameter, and Hamlet is 72% iambic pentameter. Statistics from here . So the line numbers in print editions vary, depending on the column width. – Peter Shor Jan 17, 2016 at 15:05

3 Answers 3

Each edition of Shakespeare's plays has its own numbering of lines (or in some cases, lacks line numbering). So when you cite a line you need to:

Cite the edition of the play you are using. (Unless you're doing some kind of comparative study, you aren't going to change edition halfway through your essay, so you only need to mention the edition once, not once for each citation.)

Use the line number from the edition you are using. Typically these are printed in the margin. If you're using an edition without line numbers, then don't make them up, just use the act and scene numbers.

If you need to refer to a stage direction, and your edition doesn't number the stage directions, then you cite it using the line before the stage direction. For example, "Enter Rosencrantz. (IV.3.11 s.d.)" In these editions the stage direction at the start of the scene has no line number, so just give the act and scene numbers, for example, "A platform before the castle. (I.1 s.d.)"

Why do different editions have different numbering? Well:

There are editorial decisions as to exactly what material to include. For example, Hamlet has three sources (the "first quarto", "second quarto" and "first folio" editions) that each contains material missing from the other two, and the modern editor has to decide how to combine them.

The edition can decide to number the stage directions or not.

When dialogue is in the form of prose rather than verse, the division into lines depends on the width of the page and the size of the type.

- The reason I chose your response as the selected is because my edition actually doesn't use numbering, which is what concerned me the most. Thanks to everyone else who contributed as well. – Aleksandr Hovhannisyan Jan 17, 2016 at 15:20

The edition you're using will typically have line numbers on the page. The editions I've used (e.g. The Arden Shakespeare series) do not typically count stage directions as lines in verse sections. Verse lines shared between characters count as a single line.

- Thank you! I wish I could accept both your post and Gareth Rees'. – Aleksandr Hovhannisyan Jan 17, 2016 at 15:22

Most print editions count only spoken lines in numbering lines within a scene, and start afresh with each scene. (MLA uses Hindu-Arabic numerals exclusively, separated by periods, for citations by act and scene or by act, scene, and line.) The line numbering in various editions will be consistent in the case of an all-verse play, such as Richard II, but will vary in scenes that contain some prose, since different column widths and typefaces will determine where line breaks fall in prose. Even verse passages that follow prose ones within the same scene will thus be line-numbered differently from one edition to the next.

The only entirely reliable system for citing loci in Shakespeare’s plays involves specifying an early printing (Q2 or F, say, for the second quarto or [first] folio text of Hamlet) and a line number that counts all the printed lines in that printed text from first to last, including stage directions and everything—what is called TLN (Through Line Numbering).

In dealing with the early printings, which serious Shakespeareans in both academe and the theater tend to do, be prepared for very minimal stage directions. Also, the quartos printed in Shakespeare’s lifetime generally did not divide a play at all; it was only the posthumous 1623 first folio that divided the plays into five acts each and in some cases subdivided each act into numbered scenes as well. Notations regarding where each scene is set, plus lists of Dramatis Personae, were contributed only by later editors, starting with Nicholas Rowe.

On-line access to exact transcriptions of the early printings, with TLN, can be had via the Internet Shakespeare Editions site, hosted by the University of Victoria (British Columbia, Canada). Complete facsimile images of many of the early printings are also available there.

Your Answer

Sign up or log in, post as a guest.

Required, but never shown

By clicking “Post Your Answer”, you agree to our terms of service and acknowledge you have read our privacy policy .

Not the answer you're looking for? Browse other questions tagged citation or ask your own question .

Hot network questions.

- where does the condition of aggregate demand can be written as function of aggregate wealth come from

- Can we combine a laser with a gauss rifle to get a cinematic 'laser rifle'?

- Why is "second" an adverb in "came a close second"?

- What is my new plant Avocado tree leaves dropping?

- Is it allowed to use patents for new inventions?

- Smallest Harmonic number greater than N

- How might a physicist define 'mind' using concepts of physics?

- What does "far right tilt" actually mean in the context of the EU in 2024?

- Have I ruined my AC by running it with the outside cover on?

- Am I seeing double? What kind of helicopter is this, and how many blades does it actually have?

- ytableau specify boxframe for each \ydiagram

- Why at 1 Corinthians 10:9 does the Jehovah's Witnesses NWT use the word "Jehovah" when the Greek uses "Christos/kurion" referring to Jesus Christ?

- Why was the client spooked when he saw the professor's face?

- Does it make sense for giants to use clubs or swords when fighting non-giants?

- How do you keep the horror spooky when your players are a bunch of goofballs?

- Tying shoes on Shabbat if you don’t plan to untie them in a day

- British child with Italian mother travelling to Italy

- Group with a translation invariant ultrafilter

- Is boosting all frequencies on an EQ equivalent to a flat EQ

- Is it theoretically possible for the sun to go dark?

- Geometric Brownian Motion as the limit of a Binomial Tree?

- Mistake in Proof "Every unique factorization domain is a principal ideal domain"

- Draw Memory Map/Layout/Region in TikZ

- Best way to halve 12V battery voltage for 6V device, while still being able to measure the battery level?

Script Writing Format for the Stage

#scribendiinc

The essentials of formatting your script for the theater

1. style guide specifics.

Like any other kind of formatting, the rules for script writing format vary depending on the style guide you're following. Different theatre companies, schools, and contests have different requirements for how to format script submissions. Check the website of the company you're sending your script to for submission and formatting requirements.

2. Title page

Just as Glinda the Good Witch tells Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz , "It's always best to start at the beginning." This is one rule that applies to both traveling down the Yellow Brick Road and script writing format. Your title page should be the first page of your book. It should not have a page number on it. The placement of the title on the page depends on the style guide you're following; however, most title pages have the title located about one-third of the way down the page, with the author or authors' name(s) located below it. The title is always written in all capital letters. The name(s) and contact information of the author(s) should be written on the bottom of the page in either the left or right corner, depending on the style guide being followed.

3. Character list, or dramatis personae

The next page of your script should be the list of characters . This may be titled Character List or Dramatis Personae . The characters should be listed in order of importance. Their names should be written in all capital letters and located on the left side of the page, with their corresponding descriptions located on the right side of the page. It should look something like this:

ROMEO MONTAGUE Son of MONTAGUE and LADY MONTAGUE. In love with JULIET. Very impulsive and slightly mentally unstable.

JULIET CAPULET Daughter of CAPULET and LADY CAPULET. Thinks she is in love with ROMEO, but is betrothed to PARIS. Far too young to be getting married either way.

Please note that, once you begin using the names of the characters in your actual script, you will only refer to them by their first name (given name) or last name (family name or surname).

4. Setting and time

Standard script writing format also calls for a setting and time page. This should occur after the character list. This page will not have a title. The word setting should be written in capital letters and centered at the top of the page. Beneath this should be a description of the setting. Next, the word time should be capitalized and centered on the page. Beneath this should be a description of the time during which the action is taking place. If your play has several different settings, some script writing formats require a scene-by-scene breakdown of each setting and time. Check your style guide. A basic setting and time page should look something like this:

The Capulet and Montague homes, Verona, Italy.

Three days of the year in the year 1600.

5. Act and scene labeling

Each act and scene should be labeled to achieve proper script writing format. Acts should be designated using roman numerals, while scenes should be labeled with Arabic numbering. For example, the first scene in your play should be Act I, Scene 1. All pages from the first scene onward should be numbered, and the page numbers should be placed in the upper right-hand corner of the page. Courier or Courier New are the fonts used in most script writing formats.

6. Scenes and dialogue

All stage directions, including introductory scene information, should be in parentheses. The first letter of the name of the character who is speaking should be centered, with the rest of the name continuing to the right margin. Use the Tab key rather than the centering function of your word processer. Script writing format requires that characters' names always be in all caps unless they are being used within the dialogue of other characters. The dialogue should appear directly beneath the character's name. It should look something like this:

JULIET

Romeo, Romeo! Why must you be Romeo? Forget about your father and change your name. Or, if you won't do that, just swear to love me. If you do that, I'll stop being a Capulet.

ROMEO

(to himself)

Should I keep eavesdropping, or should I let her know I'm here?

Please note that, depending on which style guide you're following, the first paragraph of a new scene may need to be indented further to the right than subsequent paragraphs.

Still need some help?

If, after reading this guide, you still find the art of script writing format to be overwhelming, don't worry. Do your best to format your script properly, and when you're finished, send it to the script editors at Scribendi.com. We'll make sure that your finished product looks polished and professional.

Have You Read?

"The Complete Beginner's Guide to Academic Writing"

Related Posts

How to Write a Screenplay

Mastering the Art of Script Writing

Script Frenzy: What Is It and How Do I Participate?

Upload your file(s) so we can calculate your word count, or enter your word count manually.

We will also recommend a service based on the file(s) you upload.

| File | Word Count | Include in Price? |

|---|

English is not my first language. I need English editing and proofreading so that I sound like a native speaker.

I need to have my journal article, dissertation, or term paper edited and proofread, or I need help with an admissions essay or proposal.

I have a novel, manuscript, play, or ebook. I need editing, copy editing, proofreading, a critique of my work, or a query package.

I need editing and proofreading for my white papers, reports, manuals, press releases, marketing materials, and other business documents.

I need to have my essay, project, assignment, or term paper edited and proofread.

I want to sound professional and to get hired. I have a resume, letter, email, or personal document that I need to have edited and proofread.

Prices include your personal % discount.

Prices include % sales tax ( ).

Writing Act One: The Setup – An ESSENTIAL and SIMPLE Breakdown

So you’ve prepared your story idea and want to put pen to paper. But where to start? No matter if you’re preparing to write the beat sheet or redrafting a finished product it’s always worth putting extra care into your first act.

While it might not be as exciting as the brilliantly executed plot twist at the end of act two or the satisfying, tear-jerking ending, act one is a vital opportunity for your screenplay to start as it means to go on. As brilliant as the rest of your screenplay might be, nobody will read or see it if they’re turned away by a slow or disjointed beginning.

Act one is your hook, your selling point, your set-up. It is one of the most important parts of writing and also the most useful. But how do you execute a gripping act one? We’ve broken down some key steps to get you started; an overview of what NEEDS to go into your act one.

Table of Contents

Writing act one, active, multi-dimensional characters, 2. creating a consistent tone, but what if you’re not writing fantasy or sci fi, 4. introducing your themes, 5. setting your story in motion, in conclusion: structuring act one.

Writing your first act or rather, the period of time before your story really kicks off with the truly dramatic event (the inciting incident), is essential to several elements of your screenplay. Character, theme , tone and your story world are all introduced here. While act one doesn’t give us the overarching conflict just yet it helps to set up and foreshadow that which is to come.

Act one is your status quo. It is how you show the audience what your world and characters were like before the conflict came along and turned it all upside down. Be it a city right before the outbreak of a zombie plague, a happy couple before the scandal that ruins their relationship, a miserable protagonist or the group of cheerful teens before the killer arrives.

When structuring your first act it should be building up to that dramatic moment where the central conflict comes into play. Whatever structure you choose for your script having that build-up is essential. If we began in the middle of the conflict without prior build-up, it would likely be jarring for the audience.

1. Introducing Your Characters

Act one is the place, crucially, for character introductions, specifically those at the core of your story. Your protagonist , antagonist and major supporting characters should all have made at least some appearance or mention in your first act. And even if the antagonist , for instance, hasn’t made an appearance, they must have some kind of presence.

This means, overall, that you don’t have to introduce essential characters during a pivotal gunfight or thrilling chase. Instead, you’ve laid the groundwork of character for the audience to enjoy the ride without having to catch up with essential information.

Baby Driver Example

So how do you introduce your characters when writing act one? Well for a good example let’s look at the opening scene of Baby Driver .

This first scene is not only technically impressive but it also gives us key insight into our protagonist without him even really saying a word himself.

We can tell from this scene alone who he is as a person.

- Baby is a getaway driver but he obviously doesn’t like to see people hurt or scared.

- He’s a demon behind the wheel and evades the police effortlessly.

- He’s generally fun and light-hearted but above all else, he has an insatiable taste in music. Music, in turn, is essential to his skills as a getaway driver.

It’s important that your character introduction gives us a sense of who this person is. It’s vital that by the end of that first scene with said character your audience at least somewhat understands who they are and remembers them.

- What is your character wearing?

- What are they doing?

- And how are they acting? How do they carry themselves?

- How do they relate to the characters and the world around them?

These are all useful and important questions to ask yourself when introducing a character. And the answers can manifest in the subtlest of actions, clothes, mannerisms and/or lines of dialogue.

Baby Driver ‘s opening also gives us a glimpse at the film’s twist antagonist : Buddy (played by Jon Hamm). While he initially appears as an ally and is the more friendly face out of the crew for most of the film, this scene demonstrates his violent tendencies and separateness from the group before we’ve even really met him, giving us as the audience a great dose of foreshadowing.

When writing act one of your screenplay be sure to add in some key character-driven moments. This is important to get across who your characters are early on. These moments not only give your audience a closer look at the character in question but also set up character development in later acts.

This will be a scene or set-piece where we learn something about the character functioning in their world. It may be how they handle a particular situation or something about what they typically do in their day to day life.

Furthermore, something to avoid with your key characters, specifically your protagonists and antagonists is to make sure none of them are flat and/or passive.

- So have them doing things constantly, even if these are only small actions.

- If your hero just sits around waiting for the villain to do something it will be boring for the audience.

- Similarly, if the antagonist is just in the background waiting for the protagonist, then tension is lost.

- The characters must be active and not passive in this first act. The inciting indent will drive them into action and into act two. But they must still be actively participating in the world around them, affecting it with their actions.

Moreover, remember to establish your characters’ flaws. Establishing these early on gives your characters more time to work on these flaws. This, in turn, means more time for character development and more in-depth arcs for those characters. A character flaw set up early on means the potential for this character flaw to be solved by the script’s subsequent acts. You’re laying the ground for potential sub-plots, moments of drama, development and ultimately change.

Another important element to consider when writing act one is tone. What are you trying to write? Is it a dark, moody neo-noir? A fun light-hearted comedy? Introducing a tone early on and keeping that tone for the remainder of your script is crucial to creating an even and consistent story.

An inconsistent tone can result in a disjointed mess.

- If someone picks up your script and finds the first few minutes to be a hilarious slapstick joyride about some soldiers at base camp but soon it becomes a story about the horrors of war, you risk losing them.

- Tone can, of course, be subverted. But the groundwork for this must still be laid. A very sudden shift in tone is difficult to pull off without the requisite build-up.

So how do you write tone into your first act? Scene descriptions can be a vital tool in this regard. Detailed world-building helps you set up the color of the characters’ environment and the elements that will bear down on them throughout the story.

Environmental descriptions, for example, are useful for introducing tone when writing your first act. Tell the reader how the moss creeps up the walls of your haunted house or how messy the room of your teenage protagonist is. You want those first images to tell your viewer what kind of film they’re in for via the detail of your writing.

Also, consider the action you write in that first scene. What happens during those first few moments of your film? And how does this set the tone for the rest of the story?

Atomic Blonde Example

The cold open from Atomic Blonde serves up a great example of how to set up tone.

- Agent Gascoigne is chased through a dingy East Berlin alleyway in his bathrobe before being viciously and unceremoniously executed, then dumped into a river.

- This sets up the film’s brutally violent and treacherous story of espionage and deceit. Whilst it also piques the interest of the audience with an instant flash of the kind of action they can expect throughout the film.

- Even Gascoigne’s bathrobe tells us that you can always be caught off guard. This is the world of the story; one where every character has to be on their toes.

The film starts with a bang and throws us into a fast-paced world of espionage. Not only do we get key information about the context, but we know exactly what kind of exploration of the context this will be. This is no historical drama, it’s an action-thriller. A more studied and slower introduction might make the audience think they are watching a drama, particularly given the context. But the action and style of that action lay out the genre and tone in no uncertain terms.

3. Introducing Your World

World building is something that can be useful to split into two parts; exposition and backstory. These two things may sound the same, but they are very different.

- Exposition is what you’ve written into your script.

- Backstory is your overall world, such as fictional historical events or a character’s life story.

When writing act one it can be tempting to have a great big exposition dump. If you’ve written a vibrant fantasy world to accompany the hero’s quest, for example, you might want to write your first act to be full of all the magic systems and long, detailed history you’ve conjured up. Avoid this at all costs!

Remember your first act needs to sell the script to your audience.

- If it is good for your tone or character introductions to have a scene with part of your protagonist’s backstory then do it.

- But don’t include it if you can’t think of a dramatic, imaginative way to express it.

- Don’t feel the pressure to convey everything all at once. Trust in other elements of your world and characterisation to pull the audience in.

Don’t slow down the narrative progression by including a moment where the action stops and the script essentially talks to the audience. Instead, the exposition has to be woven into the action itself. How can you illustrate the world at hand alongside introducing the character and their actions?

Green Knight Example

Take The Green Knight for example.

- The titular Green Knight’s introduction isn’t given any fanfare.

- He appears at King Arthur’s celebrations after being summoned through a magical ritual. He isn’t explained or even given much dialogue.

- This scene doesn’t tell us who the Green Knight is or where he comes from but it does tell us a lot about the world.

- Firstly there is magic in this world. We don’t know how it works or where it comes from but we don’t need to. We just need it to be established early in the story. Secondly, there are magical creatures in this world.

This means that later in the film we don’t bat an eye at the ghosts, witchcraft and giants that Gawain encounters because we understand that this world has magic and magical creatures from the world the first act establishes. It sets the stakes in this regard, allowing us to understand the reality of the world so that we can become fully enveloped in the story as a whole.

You want to pull your audience in. They don’t have to understand everything at this point, it’s more important they understand the essential rules of this world and feel invested in the protagonist navigating it. An effective character introduction, enticing tone and a rich world will significantly help achieve this.

This goes for any genre, not just fantasy. Even modern-day dramas need to have some kind of world established. Is this a world where an ex-cop can take on a gang of gun-toting criminals? Where one woman can investigate a corrupt legal system? Establishing these things are possible even in a small way makes the rest of your story believable.

Something that is important to consider in your world-building is the stakes.

- If you’re writing a story where your antagonist could destroy the world, for example, you need to establish its plausibility within your script’s world.

- For instance, if you were to write a gritty crime drama and suddenly the villain’s goal is world domination it might result in the breaking of the audience’s suspension of disbelief. But in a world of superheroes and operatic plot movements, this kind of development will likely feel more at home.

In addition, keep in mind that bigger isn’t always better. Even if your antagonist ‘s end goal is world domination, make the stakes personal to the protagonist . If you establish what is precious to your protagonist in the first act you make the audience care about the goal they’re striving towards.

This is why often even in grand stories about saving the world, the protagonist will have a love interest to save alongside the wider world. It helps makes the stakes personal and intimate, relatable and grounded.

Ultimately, the world around the protagonist is crucial in making the stakes believable. Your act one must set the rules of this world, whatever the genre. The audience will consequently be comfortable in whatever direction you take them in, implicitly understanding the parameters and stakes of the story world.

What is your story about? Friendship? Corruption? Money? Establishing this in act one is extremely important. Something can’t really be an undercurrent of the story if it shows up halfway through.

Take the beginning sequence of Star Wars .

- We immediately see the overarching theme of hope.

- The sequence aboard the Tantive IV at the start of the film sets up how outmatched the crew are with that initial shot. However, they are still able to get the plans away from Vader and the empire.

- This then unfolds throughout the film. From the daring rescue attempt on the Death Star to the climactic trench run. It all relies on a few good people versus an overwhelming tide of evil.

There will most likely be several themes running throughout your script. It’s good to think about and apply those themes that you intend for your story when writing act one.

But how does that theme manifest? Well, the theme should be visible in the characters’ actions, the tone of the world and action and the structure of how each scene pieces together.

There are many different ways to represent a theme in your act one.

- You may start with a cold open, for example.

- Or you may have the protagonist engage in a conversation with another character.

- A scene or set-piece full of action may establish the theme.

- Or imagery might highlight your theme, even if it’s subtextual.

Overall, what your story is essentially about needs to be present in act one, ideally in as much of a cinematic manner as possible, woven into the very fabric of the unfolding narrative. Your method may be subtle and almost imperceptible or clear and distinct. But either way, the audience needs to understand, implicitly or explicitly, what your story is about.

So you’ve got your characters, themes, tone and world set up, but how do you bring it all together? For an example of all of these elements in action let’s look at Bladerunner 2049 .

Blade Runner 2049 Example

- In act one we see K introduced as a merciless hunter of his fellow replicants.

- However, we also see how lonely he is and how he himself suffers his co-workers’ prejudice.

- His only companion is his store-bought holographic girlfriend, Joi.

- At the end of the first act, he is given a ray of hope and sent after a mysterious replicant child, someone that shouldn’t exist.

This series of events in the first act introduces every element we’ve discussed.

- The opening fight with Sapper sets up K’s world for us as an audience. We know that replicants who go rogue are hunted. We also know that K too is a replicant sent to execute or recapture those that escape.

- The grimy homestead, the fields of solar panels, the maggot farm and the flying car in this scene let us know that this is a dystopian future before we even see a neon-lit skyscraper or the wall holding the sea back from Los Angeles. Simply through scene descriptions in those opening moments, we garner both tone and setting.

- The initial confrontation with Sapper and the introduction of Joi demonstrate the theme of what it means to be human; Sapper questioning K’s robotic focus. Furthermore, does Joi actually care for K or is she just programmed to? The entire central theme of the film is set up over the course of those first minutes; what does it mean to be human?

Combining all of these elements and trying to keep away from pitfalls such as exposition dumps will keep your audience both engaged and make the rest of your story much easier to write by getting the set-up out of the way. This lays the ground for your story to start moving forward, heading into act two.

Act one is the set-up of your entire script. It’s the part of the story which allows you to prepare and combine each element of your story into an overarching narrative. These combined aspects allow you to create a solid foundation for your entire story. With a successful and balanced act one, you have a licence to take the audience on any journey you wish.

The first act is essentially a combination of all the different elements we’ve outlined above. Laying out these elements separately and then combining them all together is a great way to start when writing act one.

- Introduce your characters.

- Set up and color the story world.

- Set up your theme(s).

- Establish the tone.

- Then bring all these elements together.

This is the essential structure of a successful act one. It doesn’t necessarily matter what order these elements come in. Ultimately, they’re all working to support each other. But miss one and your first act won’t be robust in supporting the rest of the story.

These missing elements will always rear their head later on in the script. This might be, for example, via a jarring shift in tone, a character action that doesn’t feel justified, or a theme that seems tacked on. Act one is where you lay the foundations for the rest of your story to make sense. If you miss this opportunity, your script won’t forget.

– What did you think of this article? Share It , Like It , give it a rating, and let us know your thoughts in the comments box further down…

– Struggling with a script or book? Story analysis is what we do, all day, every day… check out our range of script coverage services for writers & filmmakers .

This article was written by Callum Scambler and edited by IS Staff.

Get *ALL* our FREE Resources

Tackle the trickiest areas of screenwriting with our exclusive eBooks. Get all our FREE resources when you join 60,000 filmmakers on our mailing list!

Success! Thanks for signing up, now please check all your email folders incl junk mail!

Something went wrong.

We respect your privacy and take protecting it seriously

2 thoughts on “Writing Act One: The Setup – An ESSENTIAL and SIMPLE Breakdown”

Amazingly in-depth and easy to absorb!

Glad we could help!

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Disclosure Policy

- Refund and Returns Policy

- CSEC ENGLISH A & B SBA

- CSEC ENGLISH A EXAM OUTLINE 2018-2025

- CSEC English B 2023-2027 Texts, Poems, Short Stories

- CSEC English B Poems 2023-2027

- Password Reset

- [email protected]

An Analysis of the Structure of Anansi by Alistair Campbell- CSEC English B

Structure of a play