- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- CME Reviews

- Best of 2021 collection

- Abbreviated Breast MRI Virtual Collection

- Contrast-enhanced Mammography Collection

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Accepted Papers Resource Guide

- About Journal of Breast Imaging

- About the Society of Breast Imaging

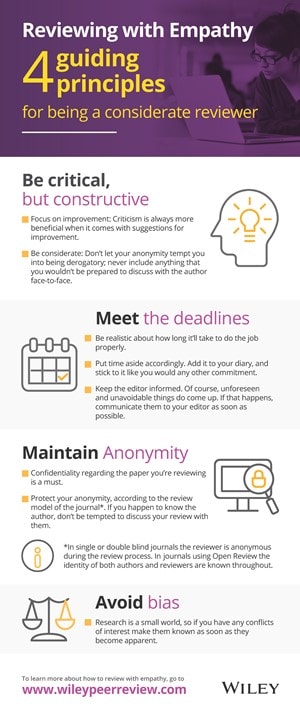

- Guidelines for Reviewers

- Resources for Reviewers and Authors

- Editorial Board

- Advertising Disclaimer

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- Introduction

- Selection of a Topic

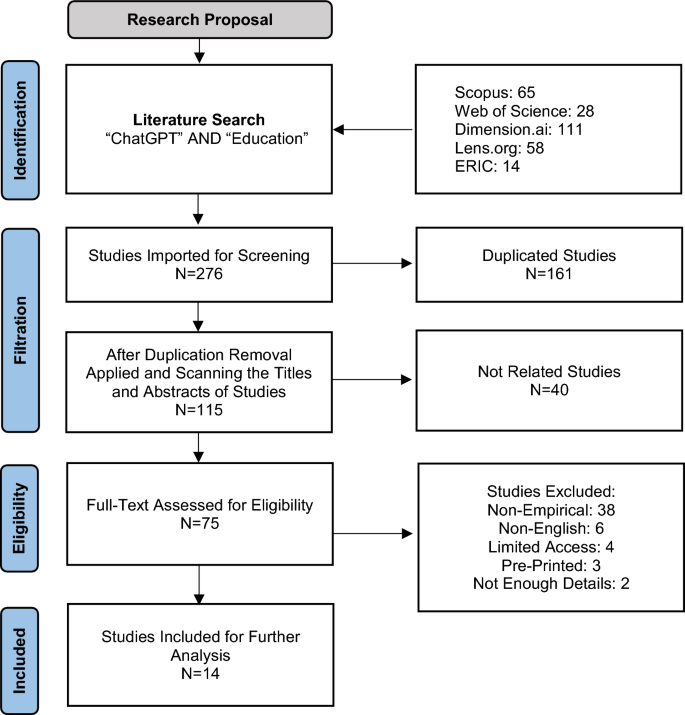

- Scientific Literature Search and Analysis

- Structure of a Scientific Review Article

- Tips for Success

- Acknowledgments

- Conflict of Interest Statement

- < Previous

A Step-by-Step Guide to Writing a Scientific Review Article

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Manisha Bahl, A Step-by-Step Guide to Writing a Scientific Review Article, Journal of Breast Imaging , Volume 5, Issue 4, July/August 2023, Pages 480–485, https://doi.org/10.1093/jbi/wbad028

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Scientific review articles are comprehensive, focused reviews of the scientific literature written by subject matter experts. The task of writing a scientific review article can seem overwhelming; however, it can be managed by using an organized approach and devoting sufficient time to the process. The process involves selecting a topic about which the authors are knowledgeable and enthusiastic, conducting a literature search and critical analysis of the literature, and writing the article, which is composed of an abstract, introduction, body, and conclusion, with accompanying tables and figures. This article, which focuses on the narrative or traditional literature review, is intended to serve as a guide with practical steps for new writers. Tips for success are also discussed, including selecting a focused topic, maintaining objectivity and balance while writing, avoiding tedious data presentation in a laundry list format, moving from descriptions of the literature to critical analysis, avoiding simplistic conclusions, and budgeting time for the overall process.

- narrative discourse

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Librarian

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 2631-6129

- Print ISSN 2631-6110

- Copyright © 2024 Society of Breast Imaging

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Critical Reviews

How to Write an Article Review (With Examples)

Last Updated: April 24, 2024 Fact Checked

Preparing to Write Your Review

Writing the article review, sample article reviews, expert q&a.

This article was co-authored by Jake Adams . Jake Adams is an academic tutor and the owner of Simplifi EDU, a Santa Monica, California based online tutoring business offering learning resources and online tutors for academic subjects K-College, SAT & ACT prep, and college admissions applications. With over 14 years of professional tutoring experience, Jake is dedicated to providing his clients the very best online tutoring experience and access to a network of excellent undergraduate and graduate-level tutors from top colleges all over the nation. Jake holds a BS in International Business and Marketing from Pepperdine University. There are 12 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 3,110,125 times.

An article review is both a summary and an evaluation of another writer's article. Teachers often assign article reviews to introduce students to the work of experts in the field. Experts also are often asked to review the work of other professionals. Understanding the main points and arguments of the article is essential for an accurate summation. Logical evaluation of the article's main theme, supporting arguments, and implications for further research is an important element of a review . Here are a few guidelines for writing an article review.

Education specialist Alexander Peterman recommends: "In the case of a review, your objective should be to reflect on the effectiveness of what has already been written, rather than writing to inform your audience about a subject."

Article Review 101

- Read the article very closely, and then take time to reflect on your evaluation. Consider whether the article effectively achieves what it set out to.

- Write out a full article review by completing your intro, summary, evaluation, and conclusion. Don't forget to add a title, too!

- Proofread your review for mistakes (like grammar and usage), while also cutting down on needless information.

- Article reviews present more than just an opinion. You will engage with the text to create a response to the scholarly writer's ideas. You will respond to and use ideas, theories, and research from your studies. Your critique of the article will be based on proof and your own thoughtful reasoning.

- An article review only responds to the author's research. It typically does not provide any new research. However, if you are correcting misleading or otherwise incorrect points, some new data may be presented.

- An article review both summarizes and evaluates the article.

- Summarize the article. Focus on the important points, claims, and information.

- Discuss the positive aspects of the article. Think about what the author does well, good points she makes, and insightful observations.

- Identify contradictions, gaps, and inconsistencies in the text. Determine if there is enough data or research included to support the author's claims. Find any unanswered questions left in the article.

- Make note of words or issues you don't understand and questions you have.

- Look up terms or concepts you are unfamiliar with, so you can fully understand the article. Read about concepts in-depth to make sure you understand their full context.

- Pay careful attention to the meaning of the article. Make sure you fully understand the article. The only way to write a good article review is to understand the article.

- With either method, make an outline of the main points made in the article and the supporting research or arguments. It is strictly a restatement of the main points of the article and does not include your opinions.

- After putting the article in your own words, decide which parts of the article you want to discuss in your review. You can focus on the theoretical approach, the content, the presentation or interpretation of evidence, or the style. You will always discuss the main issues of the article, but you can sometimes also focus on certain aspects. This comes in handy if you want to focus the review towards the content of a course.

- Review the summary outline to eliminate unnecessary items. Erase or cross out the less important arguments or supplemental information. Your revised summary can serve as the basis for the summary you provide at the beginning of your review.

- What does the article set out to do?

- What is the theoretical framework or assumptions?

- Are the central concepts clearly defined?

- How adequate is the evidence?

- How does the article fit into the literature and field?

- Does it advance the knowledge of the subject?

- How clear is the author's writing? Don't: include superficial opinions or your personal reaction. Do: pay attention to your biases, so you can overcome them.

- For example, in MLA , a citation may look like: Duvall, John N. "The (Super)Marketplace of Images: Television as Unmediated Mediation in DeLillo's White Noise ." Arizona Quarterly 50.3 (1994): 127-53. Print. [9] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- For example: The article, "Condom use will increase the spread of AIDS," was written by Anthony Zimmerman, a Catholic priest.

- Your introduction should only be 10-25% of your review.

- End the introduction with your thesis. Your thesis should address the above issues. For example: Although the author has some good points, his article is biased and contains some misinterpretation of data from others’ analysis of the effectiveness of the condom.

- Use direct quotes from the author sparingly.

- Review the summary you have written. Read over your summary many times to ensure that your words are an accurate description of the author's article.

- Support your critique with evidence from the article or other texts.

- The summary portion is very important for your critique. You must make the author's argument clear in the summary section for your evaluation to make sense.

- Remember, this is not where you say if you liked the article or not. You are assessing the significance and relevance of the article.

- Use a topic sentence and supportive arguments for each opinion. For example, you might address a particular strength in the first sentence of the opinion section, followed by several sentences elaborating on the significance of the point.

- This should only be about 10% of your overall essay.

- For example: This critical review has evaluated the article "Condom use will increase the spread of AIDS" by Anthony Zimmerman. The arguments in the article show the presence of bias, prejudice, argumentative writing without supporting details, and misinformation. These points weaken the author’s arguments and reduce his credibility.

- Make sure you have identified and discussed the 3-4 key issues in the article.

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://libguides.cmich.edu/writinghelp/articlereview

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4548566/

- ↑ Jake Adams. Academic Tutor & Test Prep Specialist. Expert Interview. 24 July 2020.

- ↑ https://guides.library.queensu.ca/introduction-research/writing/critical

- ↑ https://www.iup.edu/writingcenter/writing-resources/organization-and-structure/creating-an-outline.html

- ↑ https://writing.umn.edu/sws/assets/pdf/quicktips/titles.pdf

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/mla_style/mla_formatting_and_style_guide/mla_works_cited_periodicals.html

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4548565/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/593/2014/06/How_to_Summarize_a_Research_Article1.pdf

- ↑ https://www.uis.edu/learning-hub/writing-resources/handouts/learning-hub/how-to-review-a-journal-article

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/editing-and-proofreading/

About This Article

If you have to write an article review, read through the original article closely, taking notes and highlighting important sections as you read. Next, rewrite the article in your own words, either in a long paragraph or as an outline. Open your article review by citing the article, then write an introduction which states the article’s thesis. Next, summarize the article, followed by your opinion about whether the article was clear, thorough, and useful. Finish with a paragraph that summarizes the main points of the article and your opinions. To learn more about what to include in your personal critique of the article, keep reading the article! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Prince Asiedu-Gyan

Apr 22, 2022

Did this article help you?

Sammy James

Sep 12, 2017

Juabin Matey

Aug 30, 2017

Vanita Meghrajani

Jul 21, 2016

Nov 27, 2018

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

The Tech Edvocate

- Advertisement

- Home Page Five (No Sidebar)

- Home Page Four

- Home Page Three

- Home Page Two

- Icons [No Sidebar]

- Left Sidbear Page

- Lynch Educational Consulting

- My Speaking Page

- Newsletter Sign Up Confirmation

- Newsletter Unsubscription

- Page Example

- Privacy Policy

- Protected Content

- Request a Product Review

- Shortcodes Examples

- Terms and Conditions

- The Edvocate

- The Tech Edvocate Product Guide

- Write For Us

- Dr. Lynch’s Personal Website

- The Edvocate Podcast

- Assistive Technology

- Child Development Tech

- Early Childhood & K-12 EdTech

- EdTech Futures

- EdTech News

- EdTech Policy & Reform

- EdTech Startups & Businesses

- Higher Education EdTech

- Online Learning & eLearning

- Parent & Family Tech

- Personalized Learning

- Product Reviews

- Tech Edvocate Awards

- School Ratings

Best First Aid Kits: A Comprehensive Guide

Teaching writing in kindergarten: everything you need to know, haiti names new prime minister to try to lead country out of crisis, israel pushes into rafah as displaced palestinians search for safety, gazan officials say a strike killed 21 in al-mawasi, pope apologizes after reports that he used an anti-gay slur, growing pressure on western nations to expand the range of weaponry provided to ukraine has been escalating as the conflict with russia continues. leaders and military officials are increasingly debating the possibility of allowing ukraine to employ western-supplied weapons to carry out strikes against targets on russian territory. the crux of the argument for allowing ukraine such offensive capabilities is grounded in the desire to create a significant deterrent effect. proponents argue that enabling ukraine to strike back at russia could force moscow to reconsider its strategy and potentially lead to a de-escalation of hostilities. opponents, however, warn of the risks associated with such a move. escalation dominance, wherein one side’s increase in capabilities leads to an arms race, poses a serious concern. there is also fear that enabling ukraine to strike inside russia might provoke a strong retaliation, not just against ukraine but potentially involving western nations more directly in the conflict. the debate involves complex strategic calculations. on one hand, there’s a moral and strategic impetus to support ukraine in defending its sovereignty and territorial integrity. on the other hand, there’s a need for caution and consideration of long-term regional stability and global security. as discussions continue without definitive conclusions, it is clear that decisions made today will have lasting implications for international norms and future geopolitical conflicts. the international community awaits further developments while contemplating the far-reaching consequences of this critical juncture in east-west relations., why lawmakers are brawling and people are protesting in taiwan, three european countries formally recognize palestinian statehood, what we know about the papua new guinea landslide, how to write an article review (with sample reviews) .

An article review is a critical evaluation of a scholarly or scientific piece, which aims to summarize its main ideas, assess its contributions, and provide constructive feedback. A well-written review not only benefits the author of the article under scrutiny but also serves as a valuable resource for fellow researchers and scholars. Follow these steps to create an effective and informative article review:

1. Understand the purpose: Before diving into the article, it is important to understand the intent of writing a review. This helps in focusing your thoughts, directing your analysis, and ensuring your review adds value to the academic community.

2. Read the article thoroughly: Carefully read the article multiple times to get a complete understanding of its content, arguments, and conclusions. As you read, take notes on key points, supporting evidence, and any areas that require further exploration or clarification.

3. Summarize the main ideas: In your review’s introduction, briefly outline the primary themes and arguments presented by the author(s). Keep it concise but sufficiently informative so that readers can quickly grasp the essence of the article.

4. Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses: In subsequent paragraphs, assess the strengths and limitations of the article based on factors such as methodology, quality of evidence presented, coherence of arguments, and alignment with existing literature in the field. Be fair and objective while providing your critique.

5. Discuss any implications: Deliberate on how this particular piece contributes to or challenges existing knowledge in its discipline. You may also discuss potential improvements for future research or explore real-world applications stemming from this study.

6. Provide recommendations: Finally, offer suggestions for both the author(s) and readers regarding how they can further build on this work or apply its findings in practice.

7. Proofread and revise: Once your initial draft is complete, go through it carefully for clarity, accuracy, and coherence. Revise as necessary, ensuring your review is both informative and engaging for readers.

Sample Review:

A Critical Review of “The Effects of Social Media on Mental Health”

Introduction:

“The Effects of Social Media on Mental Health” is a timely article which investigates the relationship between social media usage and psychological well-being. The authors present compelling evidence to support their argument that excessive use of social media can result in decreased self-esteem, increased anxiety, and a negative impact on interpersonal relationships.

Strengths and weaknesses:

One of the strengths of this article lies in its well-structured methodology utilizing a variety of sources, including quantitative surveys and qualitative interviews. This approach provides a comprehensive view of the topic, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of the effects of social media on mental health. However, it would have been beneficial if the authors included a larger sample size to increase the reliability of their conclusions. Additionally, exploring how different platforms may influence mental health differently could have added depth to the analysis.

Implications:

The findings in this article contribute significantly to ongoing debates surrounding the psychological implications of social media use. It highlights the potential dangers that excessive engagement with online platforms may pose to one’s mental well-being and encourages further research into interventions that could mitigate these risks. The study also offers an opportunity for educators and policy-makers to take note and develop strategies to foster healthier online behavior.

Recommendations:

Future researchers should consider investigating how specific social media platforms impact mental health outcomes, as this could lead to more targeted interventions. For practitioners, implementing educational programs aimed at promoting healthy online habits may be beneficial in mitigating the potential negative consequences associated with excessive social media use.

Conclusion:

Overall, “The Effects of Social Media on Mental Health” is an important and informative piece that raises awareness about a pressing issue in today’s digital age. Given its minor limitations, it provides valuable

3 Ways to Make a Mini Greenhouse ...

3 ways to teach yourself to play ....

Matthew Lynch

Related articles more from author.

3 Ways to Be a Good Boxer

How to Freeze Runner Beans: 13 Steps

10 Simple Ways to Organize Desk Cables

3 Ways to Write a Disabled Character

4 Ways to Treat Tennis Elbow

3 Easy Ways to Use Crep Protect Spray

How to Write an Article Review: Tips and Examples

Did you know that article reviews are not just academic exercises but also a valuable skill in today's information age? In a world inundated with content, being able to dissect and evaluate articles critically can help you separate the wheat from the chaff. Whether you're a student aiming to excel in your coursework or a professional looking to stay well-informed, mastering the art of writing article reviews is an invaluable skill.

Short Description

In this article, our research paper writing service experts will start by unraveling the concept of article reviews and discussing the various types. You'll also gain insights into the art of formatting your review effectively. To ensure you're well-prepared, we'll take you through the pre-writing process, offering tips on setting the stage for your review. But it doesn't stop there. You'll find a practical example of an article review to help you grasp the concepts in action. To complete your journey, we'll guide you through the post-writing process, equipping you with essential proofreading techniques to ensure your work shines with clarity and precision!

What Is an Article Review: Grasping the Concept

A review article is a type of professional paper writing that demands a high level of in-depth analysis and a well-structured presentation of arguments. It is a critical, constructive evaluation of literature in a particular field through summary, classification, analysis, and comparison.

If you write a scientific review, you have to use database searches to portray the research. Your primary goal is to summarize everything and present a clear understanding of the topic you've been working on.

Writing Involves:

- Summarization, classification, analysis, critiques, and comparison.

- The analysis, evaluation, and comparison require the use of theories, ideas, and research relevant to the subject area of the article.

- It is also worth nothing if a review does not introduce new information, but instead presents a response to another writer's work.

- Check out other samples to gain a better understanding of how to review the article.

Types of Review

When it comes to article reviews, there's more than one way to approach the task. Understanding the various types of reviews is like having a versatile toolkit at your disposal. In this section, we'll walk you through the different dimensions of review types, each offering a unique perspective and purpose. Whether you're dissecting a scholarly article, critiquing a piece of literature, or evaluating a product, you'll discover the diverse landscape of article reviews and how to navigate it effectively.

.webp)

Journal Article Review

Just like other types of reviews, a journal article review assesses the merits and shortcomings of a published work. To illustrate, consider a review of an academic paper on climate change, where the writer meticulously analyzes and interprets the article's significance within the context of environmental science.

Research Article Review

Distinguished by its focus on research methodologies, a research article review scrutinizes the techniques used in a study and evaluates them in light of the subsequent analysis and critique. For instance, when reviewing a research article on the effects of a new drug, the reviewer would delve into the methods employed to gather data and assess their reliability.

Science Article Review

In the realm of scientific literature, a science article review encompasses a wide array of subjects. Scientific publications often provide extensive background information, which can be instrumental in conducting a comprehensive analysis. For example, when reviewing an article about the latest breakthroughs in genetics, the reviewer may draw upon the background knowledge provided to facilitate a more in-depth evaluation of the publication.

Need a Hand From Professionals?

Address to Our Writers and Get Assistance in Any Questions!

Formatting an Article Review

The format of the article should always adhere to the citation style required by your professor. If you're not sure, seek clarification on the preferred format and ask him to clarify several other pointers to complete the formatting of an article review adequately.

How Many Publications Should You Review?

- In what format should you cite your articles (MLA, APA, ASA, Chicago, etc.)?

- What length should your review be?

- Should you include a summary, critique, or personal opinion in your assignment?

- Do you need to call attention to a theme or central idea within the articles?

- Does your instructor require background information?

When you know the answers to these questions, you may start writing your assignment. Below are examples of MLA and APA formats, as those are the two most common citation styles.

Using the APA Format

Articles appear most commonly in academic journals, newspapers, and websites. If you write an article review in the APA format, you will need to write bibliographical entries for the sources you use:

- Web : Author [last name], A.A [first and middle initial]. (Year, Month, Date of Publication). Title. Retrieved from {link}

- Journal : Author [last name], A.A [first and middle initial]. (Publication Year). Publication Title. Periodical Title, Volume(Issue), pp.-pp.

- Newspaper : Author [last name], A.A [first and middle initial]. (Year, Month, Date of Publication). Publication Title. Magazine Title, pp. xx-xx.

Using MLA Format

- Web : Last, First Middle Initial. “Publication Title.” Website Title. Website Publisher, Date Month Year Published. Web. Date Month Year Accessed.

- Newspaper : Last, First M. “Publication Title.” Newspaper Title [City] Date, Month, Year Published: Page(s). Print.

- Journal : Last, First M. “Publication Title.” Journal Title Series Volume. Issue (Year Published): Page(s). Database Name. Web. Date Month Year Accessed.

Enhance your writing effortlessly with EssayPro.com , where you can order an article review or any other writing task. Our team of expert writers specializes in various fields, ensuring your work is not just summarized, but deeply analyzed and professionally presented. Ideal for students and professionals alike, EssayPro offers top-notch writing assistance tailored to your needs. Elevate your writing today with our skilled team at your article review writing service !

.jpg)

The Pre-Writing Process

Facing this task for the first time can really get confusing and can leave you unsure of where to begin. To create a top-notch article review, start with a few preparatory steps. Here are the two main stages from our dissertation services to get you started:

Step 1: Define the right organization for your review. Knowing the future setup of your paper will help you define how you should read the article. Here are the steps to follow:

- Summarize the article — seek out the main points, ideas, claims, and general information presented in the article.

- Define the positive points — identify the strong aspects, ideas, and insightful observations the author has made.

- Find the gaps —- determine whether or not the author has any contradictions, gaps, or inconsistencies in the article and evaluate whether or not he or she used a sufficient amount of arguments and information to support his or her ideas.

- Identify unanswered questions — finally, identify if there are any questions left unanswered after reading the piece.

Step 2: Move on and review the article. Here is a small and simple guide to help you do it right:

- Start off by looking at and assessing the title of the piece, its abstract, introductory part, headings and subheadings, opening sentences in its paragraphs, and its conclusion.

- First, read only the beginning and the ending of the piece (introduction and conclusion). These are the parts where authors include all of their key arguments and points. Therefore, if you start with reading these parts, it will give you a good sense of the author's main points.

- Finally, read the article fully.

These three steps make up most of the prewriting process. After you are done with them, you can move on to writing your own review—and we are going to guide you through the writing process as well.

Outline and Template

As you progress with reading your article, organize your thoughts into coherent sections in an outline. As you read, jot down important facts, contributions, or contradictions. Identify the shortcomings and strengths of your publication. Begin to map your outline accordingly.

If your professor does not want a summary section or a personal critique section, then you must alleviate those parts from your writing. Much like other assignments, an article review must contain an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. Thus, you might consider dividing your outline according to these sections as well as subheadings within the body. If you find yourself troubled with the pre-writing and the brainstorming process for this assignment, seek out a sample outline.

Your custom essay must contain these constituent parts:

- Pre-Title Page - Before diving into your review, start with essential details: article type, publication title, and author names with affiliations (position, department, institution, location, and email). Include corresponding author info if needed.

- Running Head - In APA format, use a concise title (under 40 characters) to ensure consistent formatting.

- Summary Page - Optional but useful. Summarize the article in 800 words, covering background, purpose, results, and methodology, avoiding verbatim text or references.

- Title Page - Include the full title, a 250-word abstract, and 4-6 keywords for discoverability.

- Introduction - Set the stage with an engaging overview of the article.

- Body - Organize your analysis with headings and subheadings.

- Works Cited/References - Properly cite all sources used in your review.

- Optional Suggested Reading Page - If permitted, suggest further readings for in-depth exploration.

- Tables and Figure Legends (if instructed by the professor) - Include visuals when requested by your professor for clarity.

Example of an Article Review

You might wonder why we've dedicated a section of this article to discuss an article review sample. Not everyone may realize it, but examining multiple well-constructed examples of review articles is a crucial step in the writing process. In the following section, our essay writing service experts will explain why.

Looking through relevant article review examples can be beneficial for you in the following ways:

- To get you introduced to the key works of experts in your field.

- To help you identify the key people engaged in a particular field of science.

- To help you define what significant discoveries and advances were made in your field.

- To help you unveil the major gaps within the existing knowledge of your field—which contributes to finding fresh solutions.

- To help you find solid references and arguments for your own review.

- To help you generate some ideas about any further field of research.

- To help you gain a better understanding of the area and become an expert in this specific field.

- To get a clear idea of how to write a good review.

View Our Writer’s Sample Before Crafting Your Own!

Why Have There Been No Great Female Artists?

Steps for Writing an Article Review

Here is a guide with critique paper format on how to write a review paper:

.webp)

Step 1: Write the Title

First of all, you need to write a title that reflects the main focus of your work. Respectively, the title can be either interrogative, descriptive, or declarative.

Step 2: Cite the Article

Next, create a proper citation for the reviewed article and input it following the title. At this step, the most important thing to keep in mind is the style of citation specified by your instructor in the requirements for the paper. For example, an article citation in the MLA style should look as follows:

Author's last and first name. "The title of the article." Journal's title and issue(publication date): page(s). Print

Abraham John. "The World of Dreams." Virginia Quarterly 60.2(1991): 125-67. Print.

Step 3: Article Identification

After your citation, you need to include the identification of your reviewed article:

- Title of the article

- Title of the journal

- Year of publication

All of this information should be included in the first paragraph of your paper.

The report "Poverty increases school drop-outs" was written by Brian Faith – a Health officer – in 2000.

Step 4: Introduction

Your organization in an assignment like this is of the utmost importance. Before embarking on your writing process, you should outline your assignment or use an article review template to organize your thoughts coherently.

- If you are wondering how to start an article review, begin with an introduction that mentions the article and your thesis for the review.

- Follow up with a summary of the main points of the article.

- Highlight the positive aspects and facts presented in the publication.

- Critique the publication by identifying gaps, contradictions, disparities in the text, and unanswered questions.

Step 5: Summarize the Article

Make a summary of the article by revisiting what the author has written about. Note any relevant facts and findings from the article. Include the author's conclusions in this section.

Step 6: Critique It

Present the strengths and weaknesses you have found in the publication. Highlight the knowledge that the author has contributed to the field. Also, write about any gaps and/or contradictions you have found in the article. Take a standpoint of either supporting or not supporting the author's assertions, but back up your arguments with facts and relevant theories that are pertinent to that area of knowledge. Rubrics and templates can also be used to evaluate and grade the person who wrote the article.

Step 7: Craft a Conclusion

In this section, revisit the critical points of your piece, your findings in the article, and your critique. Also, write about the accuracy, validity, and relevance of the results of the article review. Present a way forward for future research in the field of study. Before submitting your article, keep these pointers in mind:

- As you read the article, highlight the key points. This will help you pinpoint the article's main argument and the evidence that they used to support that argument.

- While you write your review, use evidence from your sources to make a point. This is best done using direct quotations.

- Select quotes and supporting evidence adequately and use direct quotations sparingly. Take time to analyze the article adequately.

- Every time you reference a publication or use a direct quotation, use a parenthetical citation to avoid accidentally plagiarizing your article.

- Re-read your piece a day after you finish writing it. This will help you to spot grammar mistakes and to notice any flaws in your organization.

- Use a spell-checker and get a second opinion on your paper.

The Post-Writing Process: Proofread Your Work

Finally, when all of the parts of your article review are set and ready, you have one last thing to take care of — proofreading. Although students often neglect this step, proofreading is a vital part of the writing process and will help you polish your paper to ensure that there are no mistakes or inconsistencies.

To proofread your paper properly, start by reading it fully and checking the following points:

- Punctuation

- Other mistakes

Afterward, take a moment to check for any unnecessary information in your paper and, if found, consider removing it to streamline your content. Finally, double-check that you've covered at least 3-4 key points in your discussion.

And remember, if you ever need help with proofreading, rewriting your essay, or even want to buy essay , our friendly team is always here to assist you.

Need an Article REVIEW WRITTEN?

Just send us the requirements to your paper and watch one of our writers crafting an original paper for you.

What Is A Review Article?

How to write an article review, how to write an article review in apa format.

Daniel Parker

is a seasoned educational writer focusing on scholarship guidance, research papers, and various forms of academic essays including reflective and narrative essays. His expertise also extends to detailed case studies. A scholar with a background in English Literature and Education, Daniel’s work on EssayPro blog aims to support students in achieving academic excellence and securing scholarships. His hobbies include reading classic literature and participating in academic forums.

is an expert in nursing and healthcare, with a strong background in history, law, and literature. Holding advanced degrees in nursing and public health, his analytical approach and comprehensive knowledge help students navigate complex topics. On EssayPro blog, Adam provides insightful articles on everything from historical analysis to the intricacies of healthcare policies. In his downtime, he enjoys historical documentaries and volunteering at local clinics.

Related Articles

.webp)

How to write a journal article review: Do the writing

- What's in this Guide

- What is a journal article?

- Create a template

- Choose your article to review

- Read your article carefully

Do the writing

- Remember to edit

- Additional resources

Start to write. Follow the instructions of your assessment, then structure your writing accordingly.

The four key parts of a journal article review are:

3. A critique, or a discussion about the key points of the journal article.

A critique is a discussion about the key points of the journal article. It should be a balanced discussion about the strengths and weaknesses of the key points and structure of the article.

You will also need to discuss if the author(s) points are valid (supported by other literature) and robust (would you get the same outcome if the way the information was gathered was repeated).

Example of part of a critique

4. A conclusion - a final evaluation of the article

1. Give an overall opinion of the text.

2. Briefly summarise key points and determine if they are valid, useful, accurate etc.

3. Remember, do not include new ideas or opinions in the conclusion.

Pathways and Academic Learning Support

- << Previous: Read your article carefully

- Next: Remember to edit >>

- Last Updated: Apr 27, 2023 4:28 PM

- URL: https://libguides.newcastle.edu.au/how-to-write-a-journal-article-review

How to Write an Article Review: Practical Tips and Examples

Table of contents

- 1 What Is an Article Review?

- 2 Different Types of Article Review

- 3.1 Critical review

- 3.2 Literature review

- 3.3 Mapping review/systematic map

- 3.4 Meta-analysis

- 3.5 Overview

- 3.6 Qualitative Systematic Review/Qualitative Evidence Synthesis

- 3.7 Rapid review

- 3.8 Scoping review

- 3.9 Systematic review

- 3.10 Umbrella review

- 4 Formatting

- 5 How To Write An Article Review

- 6 Article Review Outline

- 7 10 Tips for Writing an Article Review

- 8 An Article Review Example

What Is an Article Review?

Before you get started, learn what an article review is. It can be defined as a work that combines elements of summary and critical analysis. If you are writing an article review, you should take a close look at another author’s work. Many experts regularly practice evaluating the work of others. The purpose of this is to improve writing skills.

This kind of work belongs to professional pieces of writing because the process of crafting this paper requires reviewing, summarizing, and understanding the topic. Only experts are able to compose really good reviews containing a logical evaluation of a paper as well as a critique.

Your task is not to provide new information. You should process what you have in a certain publication.

Different Types of Article Review

In academic writing, the landscape of article reviews is diverse and nuanced, encompassing a variety of formats that cater to different research purposes and methodologies. Among these, three main types of article reviews stand out due to their distinct approaches and applications:

- Narrative. The basic focus here is the author’s personal experience. Judgments are presented through the prism of experiences and subsequent realizations. Besides, the use of emotional recollections is acceptable.

- Evidence. There is a significant difference from the narrative review. An in-depth study of the subject is assumed, and conclusions are built on arguments. The author may consider theories or concrete facts to support that.

- Systematic. The structure of the piece explains the approach to writing. The answer to what’s a systematic review lies on the surface. The writer should pay special attention to the chronology and logic of the narrative.

Understanding 10 Common Types

Don`t rush looking at meta-analysis vs. systematic review. We recommend that you familiarize yourself with other formats and topics of texts. This will allow you to understand the types of essays better and select them based on your request. For this purpose, we`ll discuss the typology of reviews below.

Critical review

The critical review definition says that the author must be objective and have arguments for each thought. Sometimes, amateur authors believe that they should “criticize” something. However, it is important to understand the difference since objectivity and the absence of emotional judgments are prioritized. The structure of this type of review article is as follows:

- Introduction;

- Conclusion.

“Stuffing” of the text is based on such elements as methodology, argumentation, evidence, and theory base. The subject of study is stated at the beginning of the material. Then follows the transition to the main part (facts). The final word summarizes all the information voiced earlier.

It is a mistake to believe that critical reviews are devoid of evaluation. The author’s art lies in maneuvering between facts. Smooth transition from one argument to another and lays out the conclusions in the reader. That is why such texts are used in science. The critical reviews meaning is especially tangible in medical topics.

Literature review

Literature is the basis for this type of work ─ books, essays, and articles become a source of information. Thus, the author should rethink the voiced information. After that, it is possible to proceed to conclusions. The methodology aims to find interconnections, repetitions, and even “gaps” in the literature. One important item is the referencing of sources. Footnotes are possible in the work itself or the list of resources used.

These types of research reviews often explore myths since there are often inconsistencies in mythology. Sometimes, there is contrary information. In this case, the author has to gather all existing theories. The essence does not always lie in the confirmation of facts. There are other different types of reviews for this purpose. In literary reviews, the object of study may be characters or traditions. This is where the author’s space for discovery opens up. Inconsistencies in the data can tell important details about particular periods or cultures. At the same time, patterns reveal well-established facts. Make sure to outline your work before you write. This will help you with essay writing .

Mapping review/systematic map

A mapping review, also known as a systematic map, is a unique approach to surveying and organizing existing literature, providing a panoramic view of the research landscape. This paper systematically categorizes and maps out the available literature on a particular topic, emphasizing breadth over depth. Its primary goal is to present a comprehensive visual representation of the research distribution, offering insights into the overall scope of a subject.

One of the strengths of systematic reviews is that they deeply focus on a research question with detailed analysis and synthesis, while mapping review prioritizes breadth. It identifies and categorizes a broad range of studies without necessarily providing in-depth critique or content synthesis. This approach allows for a broader understanding of the field, making it especially useful in the early stages of research. Mapping reviews excel in identifying gaps in the existing body of literature.

By systematically mapping the distribution of research, researchers can pinpoint areas where studies are scarce or nonexistent, helping to guide future research directions. This makes mapping reviews a valuable tool for researchers seeking to contribute meaningfully to a field by addressing unexplored or underexplored areas.

Meta-analysis

Meta-analysis is a powerful statistical technique. It systematically combines the results of multiple studies to derive comprehensive and nuanced insights. This method goes beyond the limitations of individual studies, offering a more robust understanding of a particular phenomenon by synthesizing data from diverse sources.

Meta-analysis employs a rigorous methodology. It involves the systematic collection and statistical integration of data from multiple studies. This methodological rigor ensures a standardized and unbiased approach to data synthesis. It is applied across various disciplines, from medicine and psychology to social sciences, providing a quantitative assessment of the overall effect of an intervention or the strength of an association.

In evidence-based fields, where informed decision-making relies on a thorough understanding of existing research, meta-analysis plays a pivotal role. It offers a quantitative overview of the collective evidence, helping researchers, policymakers, and practitioners make more informed decisions. By synthesizing results from diverse studies, meta-analysis contributes to the establishment of robust evidence-based practices, enhancing the reliability and credibility of findings in various fields. To present your research findings in the most readable way possible, learn how to write a summary of article .

If the key purpose of systematic review is to maximize the disclosure of facts, the opposite is true here. Imagine a video shot by a quadcopter from an altitude. The viewer sees a vast area of terrain without focusing on individual details. Overviews follow the same principle. The author gives a general picture of the events or objects described.

These types of reviews often seem simple. However, the role of the researcher becomes a very demanding one. The point is not just to list facts. Here, the search for information comes to the fore. After all, it is such reports that, in the future, will provide the basis for researching issues more narrowly. In essence, you yourself create a new source of information ─ students who worry that somebody may critique the author’s article love this type of material. However, there are no questions for the author; they just set the stage for discussions in different fields.

An example of this type of report would be a collection of research results from scientists. For example, statistics on the treatment of patients with certain diseases. In such a case, reference is made to scientific articles and doctrines. Based on this information, readers can speak about the effectiveness of certain treatment methods.

Qualitative Systematic Review/Qualitative Evidence Synthesis

One of the next types of review articles represents a meticulous effort to synthesize and analyze qualitative studies within a specific research domain.

The focus is synthesizing qualitative studies, employing a systematic and rigorous approach to extract meaningful insights. Its significance lies in its ability to provide a nuanced understanding of complex phenomena, offering a qualitative lens to complement quantitative analyses. Researchers can uncover patterns, themes, and contextual nuances that may elude traditional quantitative approaches by systematically reviewing and synthesizing qualitative data.

Often, you may meet discussion: is a systematic review quantitative or qualitative? The application of qualitative systematic reviews extends across diverse research domains, from healthcare and social sciences to education and psychology. For example, this approach can offer a comprehensive understanding of patient experiences and preferences in healthcare. In social sciences, it can illuminate cultural or societal dynamics. Its versatility makes it a valuable tool for researchers exploring, interpreting, and integrating qualitative findings to enrich their understanding of complex phenomena within their respective fields.

Rapid review

If you don’t know how to write an article review , try starting with this format. It is the complete opposite of everything we talked about above. The key advantage and feature is speed. Quick overviews are used when time is limited. The focus can go to individual details (key). Often, the focus is still on the principal points.

Often, these types of review papers are critically needed in politics. This method helps to communicate important information to the reader quickly. An example can be a comparison of the election programs of two politicians. The author can show the key differences. Or it can make an overview based on the theses of the opponents’ proposals on different topics.

Seeming simplicity becomes power. Such texts allow the reader to make a quick decision. The author’s task is to understand potential interests and needs. Then, highlight and present the most important data as concisely as possible. In addition to politics, such reports are often used in communications, advertising, and marketing. Experienced writers mention the one-minute principle. This means you can count on 60 seconds of the reader’s attention. If you managed to hook them ─ bravo, you have done the job!

Scoping review

If you read the official scoping review definition, you may find similarities with the systematic type of review. However, recall is a sequential and logical study in the second case. It’s like you stack things on a shelf by color, size, and texture.

This type of review can be more difficult to understand. The basic concept is to explore what is called the field of subjects. This means, on the one hand, exploring a particular topic through the existing data about it. The author tries to find gaps or patterns by drawing on sources of information.

Another good comparison between systematic and this type of review is imagining as if drawing a picture. In the first case, you will think through every nuance and detail, why it is there, and how it “moves the story.” In the second case, it is as if you are painting a picture with “broad strokes.” In doing so, you can explain your motives for choosing the primary color. For example: “I chose the emerald color because all the cultural publications say it’s a trend”. The same goes for texts.

Systematic review

Sometimes, you may encounter a battle: narrative review vs. systematic review. The point is not to compare but to understand the different types of papers. Once you understand their purpose, you can present your data better and choose a more readable format. The systematic approach can be called the most scientific. Such a review relies on the following steps:

- Literature search;

- Evaluating the information;

- Data processing;

- Careful analysis of the material.

It is the fourth point that is key. The writer should carefully process the information before using it. However, 80% of your work’s result depends on this stage’s seriousness.

A rigorous approach to data selection produces an array of factual data. That is why this method is so often used in science, education, and social fields. Where accuracy is important. At the same time, the popularity of this approach is growing in other directions.

Systematic reviews allow for using different data and methodologies,, but with one important caveat ─ if the author manages to keep the narrative structured and explain the reason for certain methods. It is not about rigor. The task of this type of review is to preserve the facts, which dictates consistency and rationality.

Umbrella review

An umbrella review is a distinctive approach that involves the review of existing reviews, providing a comprehensive synthesis of evidence on a specific topic. The methodology of an umbrella review entails systematically examining and summarizing findings from multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

This method ensures a rigorous and consolidated analysis of the existing evidence. The application of an umbrella review is broad, spanning various fields such as medicine, public health, and social sciences. It is particularly useful when a substantial body of systematic reviews exists, allowing researchers to draw overarching conclusions from the collective findings.

It allows the summarization of existing reviews and provides a new perspective on individual subtopics of the main object of study. In the context of the umbrella method, the comparison “bird’s eye view” is often cited. A bird in flight can see the whole panorama and shift its gaze to specific objects simultaneously. What becomes relevant at a particular moment? The author will face the same task.

On the one hand, you must delve into the offshoots of the researched topic. On the other hand, focus on the topic or object of study as a whole. Such a concept allows you to open up new perspectives and thoughts.

Different types of formatting styles are used for article review writing. It mainly depends on the guidelines that are provided by the instructor, sometimes, professors even provide an article review template that needs to be followed.

Here are some common types of formatting styles that you should be aware of when you start writing an article review:

- APA (American Psychological Association) – An APA format article review is commonly used for social sciences. It has guidelines for formatting the title, abstract, body paragraphs, and references. For example, the title of an article in APA format is in sentence case, whereas the publication title is in title case.

- MLA (Modern Language Association): This is a formatting style often used in humanities, such as language studies and literature. There are specific guidelines for the formatting of the title page, header, footer, and citation style.

- Chicago Manual of Style: This is one of the most commonly used formatting styles. It is often used for subjects in humanities and social sciences, but also commonly found in a newspaper title. This includes guidelines for formatting the title page, end notes, footnotes, publication title, article citation, and bibliography.

- Harvard Style: Harvard style is commonly used for social sciences and provides specific guidelines for formatting different sections of the pages, including publication title, summary page, website publisher, and more.

To ensure that your article review paper is properly formatted and meets the requirements, it is crucial to adhere to the specific guidelines for the formatting style you are using. This helps you write a good article review.

- Free unlimited checks

- All common file formats

- Accurate results

- Intuitive interface

How To Write An Article Review

There are several steps that must be followed when you are starting to review articles. You need to follow these to make sure that your thoughts are organized properly. In this way, you can present your ideas in a more concise and clear manner. Here are some tips on how to start an article review and how to cater to each writing stage.

- Read the Article Closely: Even before you start to write an article review, it’s important to make sure that you have read the specific article thoroughly. Write down the central points and all the supporting ideas. It’s important also to note any questions or comments that you have about the content.

- Identify the Thesis: Make sure that you understand the author’s main points, and identify the main thesis of the article. This will help you focus on your review and ensure that you are addressing all of the key points.

- Formulate an Introduction: The piece should start with an introduction that has all the necessary background information, possibly in the first paragraph or in the first few paragraphs. This can include a brief summary of the important points or an explanation of the importance.

- Summarize the Article : Summarize the main points when you review the article, and make sure that you include all supporting elements of the author’s thesis.

- Start with Personal Critique : Now is the time to include a personal opinion on the research article or the journal article review. Start with evaluating all the strengths and weaknesses of the reviewed article. Discuss all of the flaws that you found in the author’s evidence and reasoning. Also, point out whether the conclusion provided by the author was well presented or not.

- Add Personal Perspective: Offer your perspective on the original article, do you agree or disagree with the ideas that the article supports or not. Your critical review, in your own words, is an essential part of a good review. Make sure you address all unanswered questions in your review.

- Conclude the Article Review : In this section of the writing process, you need to be very careful and wrap up the whole discussion in a coherent manner. This is should summarize all the main points and offer an overall assessment.

Make sure to stay impartial and provide proof to back up your assessment. By adhering to these guidelines, you can create a reflective and well-structured article review.

Article Review Outline

Here is a basic, detailed outline for an article review you should be aware of as a pre-writing process if you are wondering how to write an article review.

Introduction

- Introduce the article that you are reviewing (author name, publication date, title, etc.) Now provide an overview of the article’s main topic

Summary section

- Summarize the key points in the article as well as any arguments Identify the findings and conclusion

Critical Review

- Assess and evaluate the positive aspects and the drawbacks

- Discuss if the authors arguments were verified by the evidence of the article

- Identify if the text provides substantial information for any future paper or further research

- Assess any gaps in the arguments

- Restate the thesis statement

- Provide a summary for all sections

- Write any recommendations and thoughts that you have on the article

- Never forget to add and cite any references that you used in your article

10 Tips for Writing an Article Review

Have you ever written such an assignment? If not, study the helpful tips for composing a paper. If you follow the recommendations provided here, the process of writing a summary of the article won’t be so time-consuming, and you will be able to write an article in the most effective manner.

The guidelines below will help to make the process of preparing a paper much more productive. Let’s get started!

- Check what kind of information your work should contain. After answering the key question “What is an article review?” you should learn how to structure it the right way. To succeed, you need to know what your work should be based on. An analysis with insightful observations is a must for your piece of writing.

- Identify the central idea: In your first reading, focus on the overall impression. Gather ideas about what the writer wants to tell, and consider whether he or she managed to achieve it.

- Look up unfamiliar terms. Don’t know what certain words and expressions mean? Highlight them, and don’t forget to check what they mean with a reliable source of information.

- Highlight the most important ideas. If you are reading it a second time, use a highlighter to highlight the points that are most important to understanding the passage.

- Write an outline. A well-written outline will make your life a lot easier. All your thoughts will be grouped. Detailed planning helps not to miss anything important. Think about the questions you should answer when writing.

- Brainstorm headline ideas. When choosing a project, remember: it should reflect the main idea. Make it bold and concise.

- Check an article review format example. You should check that you know how to cite an article properly. Note that citation rules are different in APA and MLA formats. Ask your teacher which one to prioritize.

- Write a good introduction. Use only one short paragraph to state the central idea of the work. Emphasize the author’s key concepts and arguments. Add the thesis at the end of the Introduction.

- Write in a formal style. Use the third person, remembering that this assignment should be written in a formal academic writing style.

- Wrap up, offer your critique, and close. Give your opinion on whether the author achieved his goals. Mention the shortcomings of the job, if any, and highlight its strengths.

If you have checked the tips and you still doubt whether you have all the necessary skills and time to prepare this kind of educational work, follow one more tip that guarantees 100% success- ask for professional assistance by asking the custom writing service PapersOwl to craft your paper instead of you. Just submit an order online and get the paper completed by experts.

An Article Review Example

If you have a task to prepare an analysis of a certain piece of literature, have a look at the article review sample. There is an article review example for you to have a clear picture of what it must look like.

Journal Article on Ayn Rand’s Works Review Example

“The purpose of the article is to consider the features of the poetics of Ayn Rand’s novels “Atlas Shrugged,” “We the living,” and “The Fountainhead.” In the analysis of the novels, the structural-semantic and the method of comparative analysis were used.

With the help of these methods, genre features of the novels were revealed, and a single conflict and a cyclic hero were identified.

In-depth reading allows us to more fully reveal the worldview of the author reflected in the novels. It becomes easier to understand the essence of the author’s ideas about the connection between being and consciousness, embodied in cyclic ideas and images of plot twists and heroes. The author did a good job highlighting the strong points of the works and mentioning the reasons for the obvious success of Ayn Rand.“

You can also search for other relevant article review examples before you start.

In conclusion, article reviews play an important role in evaluating and analyzing different scholarly articles. Writing a review requires critical thinking skills and a deep understanding of the article’s content, style, and structure. It is crucial to identify the type of article review and follow the specific guidelines for formatting style provided by the instructor or professor.

The process of writing an article review requires several steps, such as reading the article attentively, identifying the thesis, and formulating an introduction. By following the tips and examples provided in this article, students can write a worthy review that demonstrates their ability to evaluate and critique another writer’s work.

Learning how to write an article review is a critical skill for students and professionals alike. Before diving into the nitty-gritty of reviewing an article, it’s important to understand what an article review is and the elements it should include. An article review is an assessment of a piece of writing that summarizes and evaluates a work. To complete a quality article review, the author should consider the text’s purpose and content, its organization, the author’s style, and how the article fits into a larger conversation. But if you don’t have the time to do all of this work, you can always purchase a literature review from Papers Owl .

Readers also enjoyed

WHY WAIT? PLACE AN ORDER RIGHT NOW!

Just fill out the form, press the button, and have no worries!

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Findings – Types Examples and Writing Guide

Research Findings – Types Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Findings

Definition:

Research findings refer to the results obtained from a study or investigation conducted through a systematic and scientific approach. These findings are the outcomes of the data analysis, interpretation, and evaluation carried out during the research process.

Types of Research Findings

There are two main types of research findings:

Qualitative Findings

Qualitative research is an exploratory research method used to understand the complexities of human behavior and experiences. Qualitative findings are non-numerical and descriptive data that describe the meaning and interpretation of the data collected. Examples of qualitative findings include quotes from participants, themes that emerge from the data, and descriptions of experiences and phenomena.

Quantitative Findings

Quantitative research is a research method that uses numerical data and statistical analysis to measure and quantify a phenomenon or behavior. Quantitative findings include numerical data such as mean, median, and mode, as well as statistical analyses such as t-tests, ANOVA, and regression analysis. These findings are often presented in tables, graphs, or charts.

Both qualitative and quantitative findings are important in research and can provide different insights into a research question or problem. Combining both types of findings can provide a more comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon and improve the validity and reliability of research results.

Parts of Research Findings

Research findings typically consist of several parts, including:

- Introduction: This section provides an overview of the research topic and the purpose of the study.

- Literature Review: This section summarizes previous research studies and findings that are relevant to the current study.

- Methodology : This section describes the research design, methods, and procedures used in the study, including details on the sample, data collection, and data analysis.

- Results : This section presents the findings of the study, including statistical analyses and data visualizations.

- Discussion : This section interprets the results and explains what they mean in relation to the research question(s) and hypotheses. It may also compare and contrast the current findings with previous research studies and explore any implications or limitations of the study.

- Conclusion : This section provides a summary of the key findings and the main conclusions of the study.

- Recommendations: This section suggests areas for further research and potential applications or implications of the study’s findings.

How to Write Research Findings

Writing research findings requires careful planning and attention to detail. Here are some general steps to follow when writing research findings:

- Organize your findings: Before you begin writing, it’s essential to organize your findings logically. Consider creating an outline or a flowchart that outlines the main points you want to make and how they relate to one another.

- Use clear and concise language : When presenting your findings, be sure to use clear and concise language that is easy to understand. Avoid using jargon or technical terms unless they are necessary to convey your meaning.

- Use visual aids : Visual aids such as tables, charts, and graphs can be helpful in presenting your findings. Be sure to label and title your visual aids clearly, and make sure they are easy to read.

- Use headings and subheadings: Using headings and subheadings can help organize your findings and make them easier to read. Make sure your headings and subheadings are clear and descriptive.

- Interpret your findings : When presenting your findings, it’s important to provide some interpretation of what the results mean. This can include discussing how your findings relate to the existing literature, identifying any limitations of your study, and suggesting areas for future research.

- Be precise and accurate : When presenting your findings, be sure to use precise and accurate language. Avoid making generalizations or overstatements and be careful not to misrepresent your data.

- Edit and revise: Once you have written your research findings, be sure to edit and revise them carefully. Check for grammar and spelling errors, make sure your formatting is consistent, and ensure that your writing is clear and concise.

Research Findings Example

Following is a Research Findings Example sample for students:

Title: The Effects of Exercise on Mental Health

Sample : 500 participants, both men and women, between the ages of 18-45.

Methodology : Participants were divided into two groups. The first group engaged in 30 minutes of moderate intensity exercise five times a week for eight weeks. The second group did not exercise during the study period. Participants in both groups completed a questionnaire that assessed their mental health before and after the study period.

Findings : The group that engaged in regular exercise reported a significant improvement in mental health compared to the control group. Specifically, they reported lower levels of anxiety and depression, improved mood, and increased self-esteem.

Conclusion : Regular exercise can have a positive impact on mental health and may be an effective intervention for individuals experiencing symptoms of anxiety or depression.

Applications of Research Findings

Research findings can be applied in various fields to improve processes, products, services, and outcomes. Here are some examples:

- Healthcare : Research findings in medicine and healthcare can be applied to improve patient outcomes, reduce morbidity and mortality rates, and develop new treatments for various diseases.

- Education : Research findings in education can be used to develop effective teaching methods, improve learning outcomes, and design new educational programs.

- Technology : Research findings in technology can be applied to develop new products, improve existing products, and enhance user experiences.

- Business : Research findings in business can be applied to develop new strategies, improve operations, and increase profitability.

- Public Policy: Research findings can be used to inform public policy decisions on issues such as environmental protection, social welfare, and economic development.

- Social Sciences: Research findings in social sciences can be used to improve understanding of human behavior and social phenomena, inform public policy decisions, and develop interventions to address social issues.

- Agriculture: Research findings in agriculture can be applied to improve crop yields, develop new farming techniques, and enhance food security.

- Sports : Research findings in sports can be applied to improve athlete performance, reduce injuries, and develop new training programs.

When to use Research Findings

Research findings can be used in a variety of situations, depending on the context and the purpose. Here are some examples of when research findings may be useful:

- Decision-making : Research findings can be used to inform decisions in various fields, such as business, education, healthcare, and public policy. For example, a business may use market research findings to make decisions about new product development or marketing strategies.

- Problem-solving : Research findings can be used to solve problems or challenges in various fields, such as healthcare, engineering, and social sciences. For example, medical researchers may use findings from clinical trials to develop new treatments for diseases.

- Policy development : Research findings can be used to inform the development of policies in various fields, such as environmental protection, social welfare, and economic development. For example, policymakers may use research findings to develop policies aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

- Program evaluation: Research findings can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of programs or interventions in various fields, such as education, healthcare, and social services. For example, educational researchers may use findings from evaluations of educational programs to improve teaching and learning outcomes.

- Innovation: Research findings can be used to inspire or guide innovation in various fields, such as technology and engineering. For example, engineers may use research findings on materials science to develop new and innovative products.

Purpose of Research Findings

The purpose of research findings is to contribute to the knowledge and understanding of a particular topic or issue. Research findings are the result of a systematic and rigorous investigation of a research question or hypothesis, using appropriate research methods and techniques.

The main purposes of research findings are:

- To generate new knowledge : Research findings contribute to the body of knowledge on a particular topic, by adding new information, insights, and understanding to the existing knowledge base.

- To test hypotheses or theories : Research findings can be used to test hypotheses or theories that have been proposed in a particular field or discipline. This helps to determine the validity and reliability of the hypotheses or theories, and to refine or develop new ones.

- To inform practice: Research findings can be used to inform practice in various fields, such as healthcare, education, and business. By identifying best practices and evidence-based interventions, research findings can help practitioners to make informed decisions and improve outcomes.

- To identify gaps in knowledge: Research findings can help to identify gaps in knowledge and understanding of a particular topic, which can then be addressed by further research.

- To contribute to policy development: Research findings can be used to inform policy development in various fields, such as environmental protection, social welfare, and economic development. By providing evidence-based recommendations, research findings can help policymakers to develop effective policies that address societal challenges.

Characteristics of Research Findings

Research findings have several key characteristics that distinguish them from other types of information or knowledge. Here are some of the main characteristics of research findings:

- Objective : Research findings are based on a systematic and rigorous investigation of a research question or hypothesis, using appropriate research methods and techniques. As such, they are generally considered to be more objective and reliable than other types of information.

- Empirical : Research findings are based on empirical evidence, which means that they are derived from observations or measurements of the real world. This gives them a high degree of credibility and validity.