- Open access

- Published: 16 August 2022

Developing an implementation research logic model: using a multiple case study design to establish a worked exemplar

- Louise Czosnek ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2362-6888 1 ,

- Eva M. Zopf 1 , 2 ,

- Prue Cormie 3 , 4 ,

- Simon Rosenbaum 5 , 6 ,

- Justin Richards 7 &

- Nicole M. Rankin 8 , 9

Implementation Science Communications volume 3 , Article number: 90 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

8216 Accesses

4 Citations

21 Altmetric

Metrics details

Implementation science frameworks explore, interpret, and evaluate different components of the implementation process. By using a program logic approach, implementation frameworks with different purposes can be combined to detail complex interactions. The Implementation Research Logic Model (IRLM) facilitates the development of causal pathways and mechanisms that enable implementation. Critical elements of the IRLM vary across different study designs, and its applicability to synthesizing findings across settings is also under-explored. The dual purpose of this study is to develop an IRLM from an implementation research study that used case study methodology and to demonstrate the utility of the IRLM to synthesize findings across case sites.

The method used in the exemplar project and the alignment of the IRLM to case study methodology are described. Cases were purposely selected using replication logic and represent organizations that have embedded exercise in routine care for people with cancer or mental illness. Four data sources were selected: semi-structured interviews with purposely selected staff, organizational document review, observations, and a survey using the Program Sustainability Assessment Tool (PSAT). Framework analysis was used, and an IRLM was produced at each case site. Similar elements within the individual IRLM were identified, extracted, and re-produced to synthesize findings across sites and represent the generalized, cross-case findings.

The IRLM was embedded within multiple stages of the study, including data collection, analysis, and reporting transparency. Between 33-44 determinants and 36-44 implementation strategies were identified at sites that informed individual IRLMs. An example of generalized findings describing “intervention adaptability” demonstrated similarities in determinant detail and mechanisms of implementation strategies across sites. However, different strategies were applied to address similar determinants. Dependent and bi-directional relationships operated along the causal pathway that influenced implementation outcomes.

Conclusions

Case study methods help address implementation research priorities, including developing causal pathways and mechanisms. Embedding the IRLM within the case study approach provided structure and added to the transparency and replicability of the study. Identifying the similar elements across sites helped synthesize findings and give a general explanation of the implementation process. Detailing the methods provides an example for replication that can build generalizable knowledge in implementation research.

Peer Review reports

Contributions to the literature

Logic models can help understand how and why evidence-based interventions (EBIs) work to produce intended outcomes.

The implementation research logic model (IRLM) provides a method to understand causal pathways, including determinants, implementation strategies, mechanisms, and implementation outcomes.

We describe an exemplar project using a multiple case study design that embeds the IRLM at multiple stages. The exemplar explains how the IRLM helped synthesize findings across sites by identifying the common elements within the causal pathway.

By detailing the exemplar methods, we offer insights into how this approach of using the IRLM is generalizable and can be replicated in other studies.

The practice of implementation aims to get “someone…, somewhere… to do something differently” [ 1 ]. Typically, this involves changing individual behaviors and organizational processes to improve the use of evidence-based interventions (EBIs). To understand this change, implementation science applies different theories, models, and frameworks (hereafter “frameworks”) to describe and evaluate the factors and steps in the implementation process [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ]. Implementation science provides much-needed theoretical frameworks and a structured approach to process evaluations. One or more frameworks are often used within a program of work to investigate the different stages and elements of implementation [ 6 ]. Researchers have acknowledged that the dynamic implementation process could benefit from using logic models [ 7 ]. Logic models offer a systematic approach to combining multiple frameworks and to building causal pathways that explain the mechanisms behind individual and organizational change.

Logic models visually represent how an EBI is intended to work [ 8 ]. They link the available resources with the activities undertaken, the immediate outputs of this work, and the intermediate outcomes and longer-term impacts [ 8 , 9 ]. Through this process, causal pathways are identified. For implementation research, the causal pathway provides the interconnection between a chosen EBI, determinants, implementation strategies, and implementation outcomes [ 10 ]. Testing causal mechanisms in the research translation pathway will likely dominate the next wave of implementation research [ 11 , 12 ]. Causal mechanisms (or mechanisms of change) are the “process or event through which an implementation strategy operates to affect desired implementation outcomes” [ 13 ]. Identifying mechanisms can improve implementation strategies’ selection, prioritization, and targeting [ 12 , 13 ]. This provides an efficient and evidence-informed approach to implementation.

Implementation researchers have proposed several methods to develop and examine causal pathways [ 14 , 15 ] and mechanisms [ 16 , 17 ]. This includes formalizing the inherent relationship between frameworks via developing the Implementation Research Logic Model (IRLM) [ 7 ]. The IRLM is a logic model designed to improve the rigor and reproducibility of implementation research. It specifies the relationship between elements of implementation (determinant, strategies, and outcomes) and the mechanisms of change. To do this, it recommends linking implementation frameworks or relevant taxonomies (e.g., determinant and evaluation frameworks and implementation strategy taxonomy). The IRLM authors suggest the tool has multiple uses, including planning, executing, and reporting on the implementation process and synthesizing implementation findings across different contexts [ 7 ]. During its development, the IRLM was tested to confirm its utility in planning, executing, and reporting; however, its utility in synthesizing findings across different contexts is ongoing. Users of the tool are encouraged to consider three principles: (1) comprehensiveness in reporting determinants, implementation strategies, and implementation outcomes; (2) specifying the conceptual relationships via diagrammatic tools such as colors and arrows; and (3) detailing important elements of the study design. Further, the authors also recognize that critical elements of IRLM will vary across different study designs.

This study describes the development of an IRLM from a multiple case study design. Case study methodology can answer “how and why” questions about implementation. They enable researchers to develop a rich, in-depth understanding of a contemporary phenomenon within its natural context [ 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 ]. These methods can create coherence in the dynamic context in which EBIs exist [ 22 , 23 ]. Case studies are common in implementation research [ 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ], with multiple case study designs suitable for undertaking comparisons across contexts [ 31 , 32 ]. However, they are infrequently applied to establish mechanisms [ 11 ] or combine implementation elements to synthesize findings across contexts (as possible through the IRLM). Hollick and colleagues [ 33 ] undertook a comparative case study, guided by a determinant framework, to explore how context influences successful implementation. The authors contrasted determinants across sites where implementation was successful versus sites where implementation failed. The study did not extend to identifying implementation strategies or mechanisms. By contrast, van Zelm et al. [ 31 ] undertook a theory-driven evaluation of successful implementation across ten hospitals. They used joint displays to present mechanisms of change aligned with evaluation outcomes; however, they did not identify the implementation strategies within the causal pathway. Our study seeks to build on these works and explore the utility of the IRLM in synthesizing findings across sites. The dual objectives of this paper were to:

Describe how case study methods can be applied to develop an IRLM

Demonstrate the utility of the IRLM in synthesizing implementation findings across case sites.

In this section, we describe the methods used in the exemplar case study and the alignment of the IRLM to this approach. The exemplar study explored the implementation of exercise EBIs in the context of the Australian healthcare system. The exemplar study aimed to investigate the integration of exercise EBIs within routine mental illness or cancer care. The evidence base detailing the therapeutic benefits of exercise for non-communicable diseases such as cancer and mental illness are extensively documented [ 34 , 35 , 36 ] but inconsistently implemented as part of routine care [ 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 ].

Additional file 1 provides the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR).

Case study approach

We adopted an approach to case studies based on the methods described by Yin [ 18 ]. This approach is said to have post-positivist philosophical leanings, which are typically associated with the quantitative paradigm [ 19 , 45 , 46 ]. This is evidenced by the structured, deductive approach to the methods that are described with a constant lens on objectivity, validity, and generalization [ 46 ]. Yin’s approach to case studies aligns with the IRLM for several reasons. The IRLM is designed to use established implementation frameworks. The two frameworks and one taxonomy applied in our exemplar were the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [ 47 ], Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) [ 48 ], and Proctor et al.’s implementation outcomes framework [ 49 ]. These frameworks guided multiple aspects of our study (see Table 1 ). Commencing an implementation study with a preconceived plan based upon established frameworks is deductive [ 22 ]. Second, the IRLM has its foundation in logic modeling to develop cause and effect relationships [ 8 ]. Yin advocates using logic models to analyze case study findings [ 18 ]. They argue that developing logic models encourages researchers to iterate and consider plausible counterfactual explanations before upholding the causal pathway. Further, Yin notes that case studies are particularly valuable for explaining the transitions and context within the cause-and-effect relationship [ 18 ]. In our exemplar, the transition was the mechanism between the implementation strategy and implementation outcome. Finally, the proposed function of IRLM to synthesize findings across sites aligns with the exemplar study that used a multiple case approach. Multiple case studies aim to develop generalizable knowledge [ 18 , 50 ].

Case study selection and boundaries

A unique feature of Yin’s approach to multiple case studies is using replication logic to select cases [ 18 ]. Cases are chosen to demonstrate similarities (literal replication) or differences for anticipated reasons (theoretical replication) [ 18 ]. In the exemplar study, the cases were purposely selected using literal replication and displayed several common characteristics. First, all cases had delivered exercise EBIs within normal operations for at least 12 months. Second, each case site delivered exercise EBIs as part of routine care for a non-communicable disease (cancer or mental illness diagnosis). Finally, each site delivered the exercise EBI within the existing governance structures of the Australian healthcare system. That is, the organizations used established funding and service delivery models of the Australian healthcare system.

Using replication logic, we posited that sites would exhibit some similarities in the implementation process across contexts (literal replication). However, based on existing implementation literature [ 32 , 51 , 52 , 53 ], we expected sites to adapt the EBIs through the implementation process. The determinant analysis should explain these adaptions, which is informed by the CFIR (theoretical replication). Finally, in case study methods, clearly defining the boundaries of each case and the units of analysis, such as individual, the organization or intervention, helps focus the research. We considered each healthcare organization as a separate case. Within that, organizational-level analysis [ 18 , 54 ] and operationalizing the implementation outcomes focused inquiry (Table 1 ).

Data collection

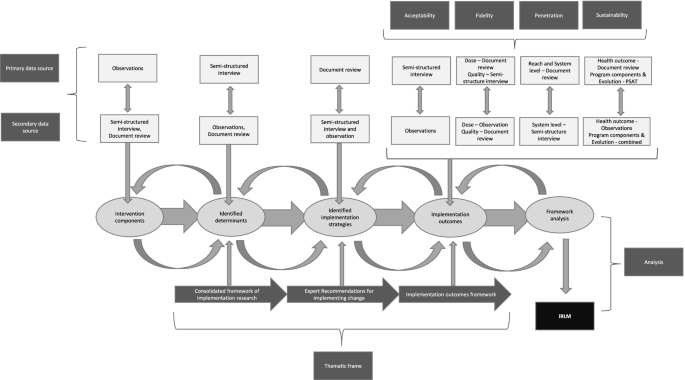

During the study conceptualization for the exemplar, we mapped the data sources to the different elements of the IRLM (Fig. 1 ). Four primary data sources informed data collection: (1) semi-structured interviews with staff; (2) document review (such as meeting minutes, strategic plans, and consultant reports); (3) naturalistic observations; and (4) a validated survey (Program Sustainability Assessment Tool (PSAT)). A case study database was developed using Microsoft Excel to manage and organize data collection [ 18 , 54 ].

Conceptual frame for the study

Semi-structured interviews

An interview guide was developed, informed by the CFIR interview guide tool [ 55 ]. Questions were selected across the five domains of the CFIR, which aligned with the delineation of determinant domains in the IRLM. Purposeful selection was used to identify staff for the interviews [ 56 ]. Adequate sample size in qualitative studies, particularly regarding the number of interviews, is often determined when data saturation is reached [ 57 , 58 ]. Unfortunately, there is little consensus on the definition of saturation [ 59 ], how to interpret when it has occurred [ 57 ], or whether it is possible to pre-determine in qualitative studies [ 60 ]. The number of participants in this study was determined based on the staff’s differential experience with the exercise EBI and their role in the organization. This approach sought to obtain a rounded view of how the EBI operated at each site [ 23 , 61 ]. Focusing on staff experiences also aligned with the organizational lens that bounded the study. Typical roles identified for the semi-structured interviews included the health professional delivering the EBI, the program manager responsible for the EBI, an organizational executive, referral sources, and other health professionals (e.g., nurses, allied health). Between five and ten interviews were conducted at each site. Interview times ranged from 16 to 72 min, most lasting around 40 min per participant.

Document review

A checklist informed by case study literature was developed outlining the typical documents the research team was seeking [ 18 ]. The types of documents sought to review included job descriptions, strategic plans/planning documents, operating procedures and organizational policies, communications (e.g., website, media releases, email, meeting minutes), annual reports, administrative databases/files, evaluation reports, third party consultant reports, and routinely collected numerical data that measured implementation outcomes [ 27 ]. As each document was identified, it was numbered, dated, and recorded in the case study database with a short description of the content related to the research aims and the corresponding IRLM construct. Between 24 and 33 documents were accessed at each site. A total of 116 documents were reviewed across the case sites.

Naturalistic observations

The onsite observations occurred over 1 week, wherein typical organizational operations were viewed. The research team interacted with staff, asked questions, and sought clarification of what was being observed; however, they did not disrupt the usual work routines. Observations allowed us to understand how the exercise EBI operated and contrast that with documented processes and procedures. They also provided the opportunity to observe non-verbal cues and interactions between staff. While onsite, case notes were recorded directly into the case study database [ 62 , 63 ]. Between 15 and 40 h were spent on observations per site. A total of 95 h was spent across sites on direct observations.

Program sustainability assessment tool (survey)

The PSAT is a planning and evaluation tool that assesses the sustainability of an intervention across eight domains [ 64 , 65 , 66 ]: (1) environmental support, (2) funding stability, (3) partnerships, (4) organizational capacity, (5) program evaluation, (6) program adaption, (7) communication, and (8) strategic planning [ 64 , 65 ]. The PSAT was administered to a subset of at least three participants per site who completed the semi-structured interview. The results were then pooled to provide an organization-wide view of EBI sustainability. Three participants per case site are consistent with previous studies that have used the tool [ 67 , 68 ] and recommendations for appropriate use [ 65 , 69 ].

We included a validated measure of sustainability, recognizing calls to improve understanding of this aspect of implementation [ 70 , 71 , 72 ]. Noting the limited number of measurement tools for evaluating sustainability [ 73 ], the PSAT’s characteristics displayed the best alignment with the study aims. To determine “best alignment,” we deferred to a study by Lennox and colleagues that helps researchers select suitable measurement tools based on the conceptualization of sustainability in the study [ 71 ]. The PSAT provides a multi-level view of sustainability. It is a measurement tool that can be triangulated with other implementation frameworks, such as the CFIR [ 74 ], to interrogate better and understand the later stages of implementation. Further, the tool provides a contemporary account of an EBIs capacity for sustainability [ 75 ]. This is consistent with case study methods, which explore complex, contemporary, real-life phenomena.

The voluminous data collection that is possible through case studies, and is often viewed as a challenge of the method [ 19 ], was advantageous to developing the IRLM in the exemplar and identifying the causal pathways. First, it aided three types of triangulation through the study (method, theory, and data source triangulation) [ 76 ]. Method triangulation involved collecting evidence via four methods: interview, observations, document review, and survey. Theoretical triangulation involved applying two frameworks and one taxonomy to understand and interpret the findings. Data source triangulation involved selecting participants with different roles within the organization to gain multiple perspectives about the phenomena being studied. Second, data collection facilitated depth and nuance in detailing determinants and implementation strategies. For the determinant analysis, this illuminated the subtleties within context and improved confidence and accuracy for prioritizing determinants. As case studies are essentially “naturalistic” studies, they provide insight into strategies that are implementable in pragmatic settings. Finally, the design’s flexibility enabled the integration of a survey and routinely collected numerical data as evaluation measures for implementation outcomes. This allowed us to contrast “numbers” against participants’ subjective experience of implementation [ 77 ].

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the PSAT and combined with the three other data sources wherein framework analysis [ 78 , 79 ] was used to analyze the data. Framework analysis includes five main phases: familiarization, identifying a thematic framework, indexing, charting, and mapping and interpretation [ 78 ]. Familiarization occurred concurrently with data collection, and the thematic frame was aligned to the two frameworks and one taxonomy we applied to the IRLM. To index and chart the data, the raw data was uploaded into NVivo 12 [ 80 ]. Codes were established to guide indexing that aligned with the thematic frame. That is, determinants within the CFIR [ 47 ], implementation strategies listed in ERIC [ 48 ], and the implementation outcomes [ 49 ] of acceptability, fidelity, penetration, and sustainability were used as codes in NVivo 12. This process produced a framework matrix that summarized the information housed under each code at each case site.

The final step of framework analysis involves mapping and interpreting the data. We used the IRLM to map and interpret the data in the exemplar. First, we identified the core elements of the implemented exercise EBI. Next, we applied the CFIR valance and strength coding to prioritize the contextual determinants. Then, we identified the implementation strategies used to address the contextual determinants. Finally, we provided a rationale (a causal mechanism) for how these strategies worked to address barriers and contribute to specific implementation outcomes. The systematic approach advocated by the IRLM provided a transparent representation of the causal pathway underpinning the implementation of the exercise EBIs. This process was followed at each case site to produce an IRLM for each organization. To compare, contrast, and synthesize findings across sites, we identified the similarities and differences in the individual IRLMs and then developed an IRLM that explained a generalized process for implementation. Through the development of the causal pathway and mechanisms, we deferred to existing literature seeking to establish these relationships [ 81 , 82 , 83 ]. Aligned with case study methods, this facilitated an iterative process of constant comparison and challenging the proposed causal relationships. Smith and colleagues advise that the IRLM “might be viewed as a somewhat simplified format,” and users are encouraged to “iterate on the design of the IRLM to increase its utility” [ 7 ]. Thus, we re-designed the IRLM within a traditional logic model structure to help make sense of the data collected through the case studies. Figure 1 depicts the conceptual frame for the study and provides a graphical representation of how the IRLM pathway was produced.

The results are presented with reference to the three principles of the IRLM: comprehensiveness, indicating the key conceptual relationship and specifying critical study design . The case study method allowed for comprehensiveness through the data collection and analysis described above. The mean number of data sources informing the analysis and development of the causal pathway at each case site was 63.75 (interviews ( M = 7), observational hours ( M =23.75), PSAT ( M =4), and document review ( M = 29). This resulted in more than 30 determinants and a similar number of implementation strategies identified at each site (determinant range per site = 33–44; implementation strategy range per site = 36–44). Developing a framework matrix meant that each determinant (prioritized and other), implementation strategy, and implementation outcome were captured. The matrix provided a direct link to the data sources that informed the content within each construct. An example from each construct was collated alongside the summary to evidence the findings.

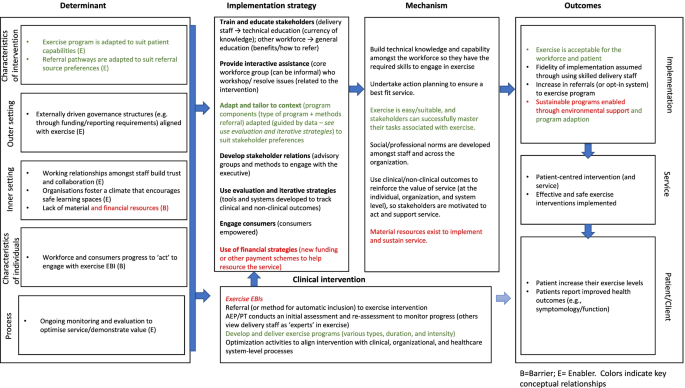

The key conceptual relationship was articulated in a traditional linear process by aligning determinant → implementation strategy → mechanism → implementation outcome, as per the IRLM. To synthesize findings across sites, we compared and contrasted the results within each of the individual IRLM and extracted similar elements to develop a generalized IRLM that represents cross-case findings. By redeveloping the IRLM within a traditional logic model structure, we added visual representations of the bi-directional and dependent relationships, illuminating the dynamism within the implementation process. To illustrate, intervention adaptability was a prioritized determinant and enabler across sites. Healthcare providers recognized that adapting and tailoring exercise EBIs increased “fit” with consumer needs. This also extended to adapting how healthcare providers referred consumers to exercise so that it was easy in the context of their other work priorities. Successful adaption was contingent upon a qualified workforce with the required skills and competencies to enact change. Different implementation strategies were used to make adaptions across sites, such as promoting adaptability and using data experts. However, despite the different strategies, successful adaptation created positive bi-directional relationships. That is, healthcare providers’ confidence and trust in the EBI grew as consumer engagement increased and clinical improvements were observed. This triggered greater engagement with the EBI (e.g., acceptability → penetration → sustainability), albeit the degree of engagement differed across sites. Figure 2 illustrates this relationship within the IRLM and provides a contrasting relationship by highlighting how a prioritized barrier across sites (available resources) was addressed.

Example of intervention adaptability (E) contrasted with available resources (B) within a synthesised IRLM across case sites

The final principle is to specify critical study design , wherein we have described how case study methodology was used to develop the IRLM exemplar. Our intention was to produce an explanatory causal pathway for the implementation process. The implementation outcomes of acceptability and fidelity were measured at the level of the provider, and penetration and sustainability were measured at the organizational level [ 49 ]. Service level and clinical level outcomes were not identified for a priori measurement throughout the study. We did identify evidence of clinical outcomes that supported our overall findings via the document review. Historical evaluations on the service indicated patients increased their exercise level or demonstrated a change in symptomology/function. The implementation strategies specified in the study were those chosen by the organizations. We did not attempt to augment routine practice or change implementation outcomes by introducing new strategies. The barriers across sites were represented with a (B) symbol and enablers with an (E) symbol in the IRLM. In the individual IRLM, consistent determinants and strategies were highlighted (via bolding) to support extraction. Finally, within the generalized IRLM, the implementation strategies are grouped according to the ERIC taxonomy category. This accounts for the different strategies applied to achieve similar outcomes across case studies.

This study provides a comprehensive overview that uses case study methodology to develop an IRLM in an implementation research project. Using an exemplar that examines implementation in different healthcare settings, we illustrate how the IRLM (that documents the causal pathways and mechanisms) was developed and enabled the synthesis of findings across sites.

Case study methodologies are fraught with inconsistencies in terminology and approach. We adopted the method described by Yin. Its guiding paradigm, which is rooted in objectivity, means it can be viewed as less flexible than other approaches [ 46 , 84 ]. We found the approach offered sufficient flexibility within the frame of a defined process. We argue that the defined process adds to the rigor and reproducibility of the study, which is consistent with the principles of implementation science. That is, accessing multiple sources of evidence, applying replication logic to select cases, maintaining a case study database, and developing logic models to establish causal pathways, demonstrates the reliability and validity of the study. The method was flexible enough to embed the IRLM within multiple phases of the study design, including conceptualization, philosophical alignment, and analysis. Paparini and colleagues [ 85 ] are developing guidance that recognizes the challenges and unmet value of case study methods for implementation research. This work, supported by the UK Medical Research Council, aims to enhance the conceptualization, application, analysis, and reporting of case studies. This should encourage and support researchers to use case study methods in implementation research with increased confidence.

The IRLM produced a relatively linear depiction of the relationship between context, strategies, and outcomes in our exemplar. However, as noted by the authors of the IRLM, the implementation process is rarely linear. If the tool is applied too rigidly, it may inadvertently depict an overly simplistic view of a complex process. To address this, we redeveloped the IRLM within a traditional logic model structure, adding visual representations of the dependent and bidirectional relationships evident within the general IRLM pathway [ 86 ]. Further, developing a general IRLM of cross-case findings that synthesized results involved a more inductive approach to identifying and extracting similar elements. It required the research team to consider broader patterns in the data before offering a prospective account of the implementation process. This was in contrast to the earlier analysis phases that directly mapped determinants and strategies to the CFIR and ERIC taxonomy. We argue that extracting similar elements is analogous to approaches that have variously been described as portable elements [ 87 ], common elements [ 88 ], or generalization by mechanism [ 89 ]. While defined and approached slightly differently, these approaches aim to identify elements frequently shared across effective EBIs and thus can form the basis of future EBIs to increase their utility, efficiency, and effectiveness [ 88 ]. We identified similarities related to determinant detail and mechanism of different implementation strategies across sites. This finding supports the view that many implementation strategies could be suitable, and selecting the “right mix” is challenging [ 16 ]. Identifying common mechanisms, such as increased motivation, skill acquisition, or optimizing workflow, enabled elucidation of the important functions of strategies. This can help inform the selection of appropriate strategies in future implementation efforts.

Finally, by developing individual IRLMs and then re-producing a general IRLM, we synthesized findings across sites and offered generalized findings. The ability to generalize from case studies is debated [ 89 , 90 ], with some considering the concept a fallacy [ 91 ]. That is, the purpose of qualitative research is to develop a richness through data that is situated within a unique context. Trying to extrapolate from findings is at odds with exploring unique context. We suggest the method described herein and the application of IRLM could be best applied to a form of generalization called ‘transferability’ [ 91 , 92 ]. This suggests that findings from one study can be transferred to another setting or population group. In this approach, the new site takes the information supplied and determines those aspects that would fit with their unique environment. We argue that elucidating the implementation process across multiple sites improves the confidence with which certain “elements” could be applied to future implementation efforts. For example, our approach may also be helpful for multi-site implementation studies that use methods other than case studies. Developing a general IRLM through study conceptualization could identify consistencies in baseline implementation status across sites. Multi-site implementation projects may seek to introduce and empirically test implementation strategies, such as via a cluster randomized controlled trial [ 93 ]. Within this study design, baseline comparison between control and intervention sites might extend to a comparison of organizational type, location and size, and individual characteristics, but not the chosen implementation strategies [ 94 ]. Applying the approach described within our study could enhance our understanding of how to support effective implementation.

Limitations

After the research team conceived this study, the authors of the PSAT validated another tool for use in clinical settings (Clinical Sustainability Assessment Tool (CSAT)) [ 95 ]. This tool appears to align better with our study design due to its explicit focus on maintaining structured clinical care practices. The use of multiple data sources and consistency in some elements across the PSAT and CSAT should minimize the limitations in using the PSAT survey tool. At most case sites, limited staff were involved in developing and implementing exercise EBI. Participants who self-selected for interviews may be more invested in assuring positive outcomes for the exercise EBI. Inviting participants from various roles was intended to reduce selection bias. Finally, we recognize recent correspondence suggesting the IRLM misses a critical step in the causal pathway. That is the mechanism between determinant and selection of an appropriate implementation strategy [ 96 ]. Similarly, Lewis and colleagues note that additional elements, including pre-conditions, moderators, and mediators (distal and proximal), exist within the causal pathway [ 13 ]. Through the iterative process of developing the IRLM, decisions were made about the determinant → implementation strategy relationship; however, this is not captured in the IRLM. Secondary analysis of the case study data would allow elucidation of these relationships, as this information can be extracted through the case study database. This was outside the scope of the exemplar study.

Developing an IRLM via case study methods proved useful in identifying causal pathways and mechanisms. The IRLM can complement and enhance the study design by providing a consistent and structured approach. In detailing our approach, we offer an example of how multiple case study designs that embed the IRLM can aid the synthesis of findings across sites. It also provides a method that can be replicated in future studies. Such transparency adds to the quality, reliability, and validity of implementation research.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author [LC]. The data are not publicly available due to them containing information that could compromise research participant privacy.

Presseau J, McCleary N, Lorencatto F, Patey AM, Grimshaw JM, Francis JJ. Action, actor, context, target, time (AACTT): a framework for specifying behaviour. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):102.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Damschroder LJ. Clarity out of chaos: use of theory in implementation research. Psychiatry Res. 2020;283(112461).

Bauer M, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Smith J, Kilbourne A. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol. 2015;3(1):32.

Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):53.

Lynch EA, Mudge A, Knowles S, Kitson AL, Hunter SC, Harvey G. “There is nothing so practical as a good theory”: a pragmatic guide for selecting theoretical approaches for implementation projects. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):857.

Birken SA, Powell BJ, Presseau J, Kirk MA, Lorencatto F, Gould NJ, et al. Combined use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) and the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF): a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):2.

Smith JD, Li DH, Rafferty MR. The Implementation Research Logic Model: a method for planning, executing, reporting, and synthesizing implementation projects. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):84.

Kellogg WK. Foundation. Logic model development guide. Michigan, USA; 2004.

McLaughlin JA, Jordan GB. Logic models: a tool for telling your programs performance story. Eval Prog Plann. 1999;22(1):65–72.

Article Google Scholar

Anselmi L, Binyaruka P, Borghi J. Understanding causal pathways within health systems policy evaluation through mediation analysis: an application to payment for performance (P4P) in Tanzania. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):10.

Lewis C, Boyd M, Walsh-Bailey C, Lyon A, Beidas R, Mittman B, et al. A systematic review of empirical studies examining mechanisms of implementation in health. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):21.

Powell BJ, Fernandez ME, Williams NJ, Aarons GA, Beidas RS, Lewis CC, et al. Enhancing the impact of implementation strategies in healthcare: a research agenda. Front Public Health. 2019;7(3).

Lewis CC, Klasnja P, Powell BJ, Lyon AR, Tuzzio L, Jones S, Walsh-Bailey C and Weiner B. From classification to causality: advancing understanding of mechanisms of change in implementation science. Front Public Health. 2018;6(136).

Bartholomew L, Parcel G, Kok G. Intervention mapping: a process for developing theory and evidence-based health education programs. Health Educ Behav. 1998;25(5):545–63.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Weiner BJ, Lewis MA, Clauser SB, Stitzenberg KB. In search of synergy: strategies for combining interventions at multiple levels. JNCI Monographs. 2012;2012(44):34–41.

Powell BJ, Beidas RS, Lewis CC, Aarons GA, McMillen J, Proctor EK, et al. Methods to improve the selection and tailoring of implementation strategies. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2017;44(2):177–94.

Fernandez ME, ten Hoor GA, van Lieshout S, Rodriguez SA, Beidas RS, Parcel G, Ruiter R, Markham C and Kok G. Implementation mapping: using intervention mapping to develop implementation strategies. Frontiers. Public Health. 2019;7(158).

Yin R. Case study research and applications design and methods. 6th Edition ed. United States of America: Sage Publications; 2018.

Google Scholar

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:100.

Stake R. The art of case study reseach. United States of America: Sage Publications; 2005.

Thomas G. How to do your case study. 2nd Edition ed. London: Sage Publications; 2016.

Ramanadhan S, Revette AC, Lee RM and Aveling E. Pragmatic approaches to analyzing qualitative data for implementation science: an introduction. Implement Sci Commun. 2021;2(70).

National Cancer Institute. Qualitative methods in implementation science United States of America: National Institutes of Health Services; 2018.

Mathers J, Taylor R, Parry J. The challenge of implementing peer-led interventions in a professionalized health service: a case study of the national health trainers service in England. Milbank Q. 2014;92(4):725–53.

Powell BJ, Proctor EK, Glisson CA, Kohl PL, Raghavan R, Brownson RC, et al. A mixed methods multiple case study of implementation as usual in children’s social service organizations: study protocol. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):92.

van de Glind IM, Heinen MM, Evers AW, Wensing M, van Achterberg T. Factors influencing the implementation of a lifestyle counseling program in patients with venous leg ulcers: a multiple case study. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):104.

Greenhalgh T, Macfarlane F, Barton-Sweeney C, Woodard F. “If we build it, will it stay?” A case study of the sustainability of whole-system change in London. Milbank Q. 2012;90(3):516–47.

Urquhart R, Kendell C, Geldenhuys L, Ross A, Rajaraman M, Folkes A, et al. The role of scientific evidence in decisions to adopt complex innovations in cancer care settings: a multiple case study in Nova Scotia, Canada. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):14.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Herinckx H, Kerlinger A, Cellarius K. Statewide implementation of high-fidelity recovery-oriented ACT: A case study. Implement Res Pract. 2021;2:2633489521994938.

Young AM, Hickman I, Campbell K, Wilkinson SA. Implementation science for dietitians: The ‘what, why and how’ using multiple case studies. Nutr Diet. 2021;78(3):276–85.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

van Zelm R, Coeckelberghs E, Sermeus W, Wolthuis A, Bruyneel L, Panella M, et al. A mixed methods multiple case study to evaluate the implementation of a care pathway for colorectal cancer surgery using extended normalization process theory. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):11.

Albers B, Shlonsky A, Mildon R. Implementation Science 3.0. Switzerland: Springer; 2020.

Book Google Scholar

Hollick RJ, Black AJ, Reid DM, McKee L. Shaping innovation and coordination of healthcare delivery across boundaries and borders. J Health Organ Manag. 2019;33(7/8):849–68.

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Pedersen B, Saltin B. Exercise as medicine – evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015;25:1–72.

Firth J, Siddiqi N, Koyanagi A, Siskind D, Rosenbaum S, Galletly C, et al. The Lancet Psychiatry Commission: a blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(8):675–712.

Campbell K, Winters-Stone K, Wisekemann J, May A, Schwartz A, Courneya K, et al. Exercise guidelines for cancer survivors: consensus statement from international multidisciplinary roundtable. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51(11):2375–90.

Deenik J, Czosnek L, Teasdale SB, Stubbs B, Firth J, Schuch FB, et al. From impact factors to real impact: translating evidence on lifestyle interventions into routine mental health care. Transl Behav Med. 2020;10(4):1070–3.

Suetani S, Rosenbaum S, Scott JG, Curtis J, Ward PB. Bridging the gap: What have we done and what more can we do to reduce the burden of avoidable death in people with psychotic illness? Epidemiol Psychiatric Sci. 2016;25(3):205–10.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Stanton R, Rosenbaum S, Kalucy M, Reaburn P, Happell B. A call to action: exercise as treatment for patients with mental illness. Aust J Primary Health. 2015;21(2):120–5.

Rosenbaum S, Hobson-Powell A, Davison K, Stanton R, Craft LL, Duncan M, et al. The role of sport, exercise, and physical activity in closing the life expectancy gap for people with mental illness: an international consensus statement by Exercise and Sports Science Australia, American College of Sports Medicine, British Association of Sport and Exercise Science, and Sport and Exercise Science New Zealand. Transll J Am Coll Sports Med. 2018;3(10):72–3.

Chambers D, Vinson C, Norton W. Advancing the science of implementation across the cancer continuum. United States of America: Oxford University Press Inc; 2018.

Schmitz K, Campbell A, Stuiver M, Pinto B, Schwartz A, Morris G, et al. Exercise is medicine in oncology: engaging clinicians to help patients move through cancer. Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(6):468–84.

Santa Mina D, Alibhai S, Matthew A, Guglietti C, Steele J, Trachtenberg J, et al. Exercise in clinical cancer care: a call to action and program development description. Curr Oncol. 2012;19(3):9.

Czosnek L, Rankin N, Zopf E, Richards J, Rosenbaum S, Cormie P. Implementing exercise in healthcare settings: the potential of implementation science. Sports Med. 2020;50(1):1–14.

Harrison H, Birks M, Franklin R, Mills J. Case study research: foundations and methodological orientations. Forum: Qualitative. Soc Res. 2017;18(1).

Yazan B. Three approaches to case study methods in education: Yin, Merriam, and Stake. Qual Rep. 2015;20(2):134–52.

Damschroder L, Aaron D, Keith R, Kirsh S, Alexander J, Lowery J. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50.

Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):21.

Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Admin Pol Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65–76.

Heale R, Twycross A. What is a case study? Evid Based Nurs. 2018;21(1):7–8.

Brownson R, Colditz G, Proctor E. Dissemination and implementation research in health: translating science to practice. Second ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2017.

Quiñones MM, Lombard-Newell J, Sharp D, Way V, Cross W. Case study of an adaptation and implementation of a Diabetes Prevention Program for individuals with serious mental illness. Transl Behav Med. 2018;8(2):195–203.

Wiltsey Stirman S, Baumann AA, Miller CJ. The FRAME: an expanded framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):58.

Baxter P, Jack S. Qualitative case study methodology: study design and implementation for novice researchers. Qual Rep. 2008;13(4):544–59.

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research 2018. Available from: http://www.cfirguide.org/index.html . Cited 2018 14 February.

Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Admin Pol Ment Health. 2015;42(5):533–44.

Francis JJ, Johnston M, Robertson C, Glidewell L, Entwistle V, Eccles MP, et al. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol Health. 2010;25(10):1229–45.

Teddlie C, Yu F. Mixed methods sampling: a typology with examples. J Mixed Methods Res. 2007;1(1):77–100.

Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, Baker S, Waterfield J, Bartlam B, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52(4):1893–907.

Braun V, Clarke V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2021;13(2):201–16.

Burau V, Carstensen K, Fredens M, Kousgaard MB. Exploring drivers and challenges in implementation of health promotion in community mental health services: a qualitative multi-site case study using Normalization Process Theory. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):36.

Phillippi J, Lauderdale J. A guide to field notes for qualitative research: context and conversation. Qual Health Res. 2018;28(3):381–8.

Mulhall A. In the field: notes on observation in qualitative research. J Adv Nurs. 2003;41(3):306–13.

Schell SF, Luke DA, Schooley MW, Elliott MB, Herbers SH, Mueller NB, et al. Public health program capacity for sustainability: a new framework. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):15.

Washington University. The Program Sustainability Assessment Tool St Louis: Washington University; 2018. Available from: https://sustaintool.org/ . Cited 2018 14 February.

Luke DA, Calhoun A, Robichaux CB, Elliott MB, Moreland-Russell S. The Program Sustainability Assessment Tool: a new instrument for public health programs. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E12.

Stoll S, Janevic M, Lara M, Ramos-Valencia G, Stephens TB, Persky V, et al. A mixed-method application of the Program Sustainability Assessment Tool to evaluate the sustainability of 4 pediatric asthma care coordination programs. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:E214.

Kelly C, Scharff D, LaRose J, Dougherty NL, Hessel AS, Brownson RC. A tool for rating chronic disease prevention and public health interventions. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E206.

Calhoun A, Mainor A, Moreland-Russell S, Maier RC, Brossart L, Luke DA. Using the Program Sustainability Assessment Tool to assess and plan for sustainability. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E11.

Proctor E, Luke D, Calhoun A, McMillen C, Brownson R, McCrary S, et al. Sustainability of evidence-based healthcare: research agenda, methodological advances, and infrastructure support. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):88.

Lennox L, Maher L, Reed J. Navigating the sustainability landscape: a systematic review of sustainability approaches in healthcare. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):27.

Moore JE, Mascarenhas A, Bain J, Straus SE. Developing a comprehensive definition of sustainability. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):110.

Lewis CC, Fischer S, Weiner BJ, Stanick C, Kim M, Martinez RG. Outcomes for implementation science: an enhanced systematic review of instruments using evidence-based rating criteria. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):155.

Shelton RC, Chambers DA, Glasgow RE. An extension of RE-AIM to enhance sustainability: addressing dynamic context and promoting health equity over time. Front Public Health. 2020;8(134).

Moullin JC, Sklar M, Green A, Dickson KS, Stadnick NA, Reeder K, et al. Advancing the pragmatic measurement of sustainment: a narrative review of measures. Implement Sci Commun. 2020;1(1):76.

Denzin N. The research act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods. New Jersey: Transaction Publishers; 1970.

Grant BM, Giddings LS. Making sense of methodologies: a paradigm framework for the novice researcher. Contemp Nurse. 2002;13(1):10–28.

Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):117.

Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000;320(7227):114–6.

QSR International. NVivo 11 Pro for Windows 2018. Available from: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysissoftware/home .

Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Fernández ME, Abadie B, Damschroder LJ. Choosing implementation strategies to address contextual barriers: diversity in recommendations and future directions. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):42.

Michie S, Johnston M, Rothman AJ, de Bruin M, Kelly MP, Carey RN, et al. Developing an evidence-based online method of linking behaviour change techniques and theoretical mechanisms of action: a multiple methods study. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals. Library. 2021;9:1.

Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D, Walker A. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(1):26–33.

Ebneyamini S, Sadeghi Moghadam MR. Toward developing a framework for conducting case study research. Int J Qual Methods. 2018;17(1):1609406918817954.

Paparini S, Green J, Papoutsi C, Murdoch J, Petticrew M, Greenhalgh T, et al. Case study research for better evaluations of complex interventions: rationale and challenges. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):301.

Sarkies M, Long JC, Pomare C, Wu W, Clay-Williams R, Nguyen HM, et al. Avoiding unnecessary hospitalisation for patients with chronic conditions: a systematic review of implementation determinants for hospital avoidance programmes. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):91.

Koorts H, Cassar S, Salmon J, Lawrence M, Salmon P, Dorling H. Mechanisms of scaling up: combining a realist perspective and systems analysis to understand successfully scaled interventions. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2021;18(1):42.

Engell T, Kirkøen B, Hammerstrøm KT, Kornør H, Ludvigsen KH, Hagen KA. Common elements of practice, process and implementation in out-of-school-time academic interventions for at-risk children: a systematic review. Prev Sci. 2020;21(4):545–56.

Bengtsson B, Hertting N. Generalization by mechanism: thin rationality and ideal-type analysis in case study research. Philos Soc Sci. 2014;44(6):707–32.

Tsang EWK. Generalizing from research findings: the merits of case studies. Int J Manag Rev. 2014;16(4):369–83.

Polit DF, Beck CT. Generalization in quantitative and qualitative research: myths and strategies. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(11):1451–8.

Adler C, Hirsch Hadorn G, Breu T, Wiesmann U, Pohl C. Conceptualizing the transfer of knowledge across cases in transdisciplinary research. Sustain Sci. 2018;13(1):179–90.

Wolfenden L, Foy R, Presseau J, Grimshaw JM, Ivers NM, Powell BJ, et al. Designing and undertaking randomised implementation trials: guide for researchers. BMJ. 2021;372:m3721.

Nathan N, Hall A, McCarthy N, Sutherland R, Wiggers J, Bauman AE, et al. Multi-strategy intervention increases school implementation and maintenance of a mandatory physical activity policy: outcomes of a cluster randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. 2022;56(7):385–93.

Malone S, Prewitt K, Hackett R, Lin JC, McKay V, Walsh-Bailey C, et al. The Clinical Sustainability Assessment Tool: measuring organizational capacity to promote sustainability in healthcare. Implement Sci Commun. 2021;2(1):77.

Sales AE, Barnaby DP, Rentes VC. Letter to the editor on “the implementation research logic model: a method for planning, executing, reporting, and synthesizing implementation projects” (Smith JD, Li DH, Rafferty MR. the implementation research logic model: a method for planning, executing, reporting, and synthesizing implementation projects. Implement Sci. 2020;15 (1):84. Doi:10.1186/s13012-020-01041-8). Implement Sci. 2021;16(1):97.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the healthcare organizations and staff who supported the study.

SR is funded by an NHMRC Early Career Fellowship (APP1123336). The funding body had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation, or manuscript development.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Mary MacKillop Institute for Health Research, Australian Catholic University, Melbourne, Australia

Louise Czosnek & Eva M. Zopf

Cabrini Cancer Institute, The Szalmuk Family Department of Medical Oncology, Cabrini Health, Melbourne, Australia

Eva M. Zopf

Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, Australia

Prue Cormie

Sir Peter MacCallum Department of Oncology, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia

Discipline of Psychiatry and Mental Health, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

Simon Rosenbaum

School of Health Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

Faculty of Health, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand

Justin Richards

Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia

Nicole M. Rankin

Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

LC, EZ, SR, JR, PC, and NR contributed to the conceptualization of the study. LC undertook the data collection, and LC, EZ, SR, JR, PC, and NR supported the analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by LC with NR and EZ providing first review. LC, EZ, SR, JR, PC, and NR commented on previous versions of the manuscript and provided critical review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Louise Czosnek .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study is approved by Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee - Concord Repatriation General Hospital (2019/ETH11806). Ethical approval is also supplied by Australian Catholic University (2018-279E), Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre (19/175), North Sydney Local Health District - Macquarie Hospital (2019/STE14595), and Alfred Health (516-19).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

PC is the recipient of a Victorian Government Mid-Career Research Fellowship through the Victorian Cancer Agency. PC is the Founder and Director of EX-MED Cancer Ltd, a not-for-profit organization that provides exercise medicine services to people with cancer. PC is the Director of Exercise Oncology EDU Pty Ltd, a company that provides fee for service training courses to upskill exercise professionals in delivering exercise to people with cancer.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1..

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Czosnek, L., Zopf, E.M., Cormie, P. et al. Developing an implementation research logic model: using a multiple case study design to establish a worked exemplar. Implement Sci Commun 3 , 90 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-022-00337-8

Download citation

Received : 19 March 2022

Accepted : 01 August 2022

Published : 16 August 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-022-00337-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Logic model

- Case study methods

- Causal pathways

- Causal mechanisms

Implementation Science Communications

ISSN: 2662-2211

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

The theory contribution of case study research designs

- Original Research

- Open access

- Published: 16 February 2017

- Volume 10 , pages 281–305, ( 2017 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Hans-Gerd Ridder 1

164k Accesses

298 Citations

11 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The objective of this paper is to highlight similarities and differences across various case study designs and to analyze their respective contributions to theory. Although different designs reveal some common underlying characteristics, a comparison of such case study research designs demonstrates that case study research incorporates different scientific goals and collection and analysis of data. This paper relates this comparison to a more general debate of how different research designs contribute to a theory continuum. The fine-grained analysis demonstrates that case study designs fit differently to the pathway of the theory continuum. The resulting contribution is a portfolio of case study research designs. This portfolio demonstrates the heterogeneous contributions of case study designs. Based on this portfolio, theoretical contributions of case study designs can be better evaluated in terms of understanding, theory-building, theory development, and theory testing.

Similar content being viewed by others

What is Qualitative in Qualitative Research

Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review

Literature reviews as independent studies: guidelines for academic practice

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Case study research scientifically investigates into a real-life phenomenon in-depth and within its environmental context. Such a case can be an individual, a group, an organization, an event, a problem, or an anomaly (Burawoy 2009 ; Stake 2005 ; Yin 2014 ). Unlike in experiments, the contextual conditions are not delineated and/or controlled, but part of the investigation. Typical for case study research is non-random sampling; there is no sample that represents a larger population. Contrary to quantitative logic, the case is chosen, because the case is of interest (Stake 2005 ), or it is chosen for theoretical reasons (Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007 ). For within-case and across-case analyses, the emphasis in data collection is on interviews, archives, and (participant) observation (Flick 2009 : 257; Mason 2002 : 84). Case study researchers usually triangulate data as part of their data collection strategy, resulting in a detailed case description (Burns 2000 ; Dooley 2002 ; Eisenhardt 1989 ; Ridder 2016 ; Stake 2005 : 454). Potential advantages of a single case study are seen in the detailed description and analysis to gain a better understanding of “how” and “why” things happen. In single case study research, the opportunity to open a black box arises by looking at deeper causes of the phenomenon (Fiss 2009 ). The case data can lead to the identification of patterns and relationships, creating, extending, or testing a theory (Gomm et al. 2000 ). Potential advantages of multiple case study research are seen in cross-case analysis. A systematic comparison in cross-case analysis reveals similarities and differences and how they affect findings. Each case is analyzed as a single case on its own to compare the mechanisms identified, leading to theoretical conclusions (Vaughan 1992 : 178). As a result, case study research has different objectives in terms of contributing to theory. On the one hand, case study research has its strength in creating theory by expanding constructs and relationships within distinct settings (e.g., in single case studies). On the other hand, case study research is a means of advancing theories by comparing similarities and differences among cases (e.g., in multiple case studies).

Unfortunately, such diverging objectives are often neglected in case study research. Burns ( 2000 : 459) emphasizes: “The case study has unfortunately been used as a ‘catch –all’ category for anything that does not fit into experimental, survey, or historical methods.”

Therefore, this paper compares case study research designs. Such comparisons have been conducted previously regarding their philosophical assumptions and orientations, key elements of case study research, their range of application, and the lacks of methodological procedures in publications. (Baxter and Jack 2008 ; Dooley 2002 ; Dyer and Wilkins 1991 ; Piekkari et al. 2009 ; Welch et al. 2011 ). This paper aims to compare case study research designs regarding their contributions to theory.

Case study research designs will be analyzed regarding their various strengths on a theory continuum. Edmondson and McManus ( 2007 ) initiated a debate on whether the stage of theory fits to research questions, style of data collection, and analyses. Similarly, Colquitt and Zapata-Phelan ( 2007 ) created a taxonomy capturing facets of empirical article’s theoretical contributions by distinguishing between theory-building and theory testing. Corley and Gioia ( 2011 ) extended this debate by focusing on the practicality of theory and the importance of prescience. While these papers consider the whole range of methodological approaches on a higher level, they treat case studies as relatively homogeneous. This paper aims to delve into a deeper level of analysis by solely focusing on case study research designs and their respective fit on this theory continuum. This approach offers a more fine-grained understanding that sheds light on the diversity of case study research designs in terms of their differential theory contributions. Such a deep level of analysis on case study research designs enables more rigor in theory contribution. To analyze alternative case study research designs regarding their contributions to theory, I engage into the following steps:

First, differences between case study research designs are depicted. I outline and compare the case study research designs with regard to the key elements, esp. differences in research questions, frameworks, sampling, data collection, and data analysis. These differences result in a portfolio of various case study research designs.

Second, I outline and substantiate a theory continuum that varies between theory-building, theory development, and testing theory. Based on this continuum, I analyze and discuss each of the case study research designs with regard to their location on the theory continuum. This analysis is based on a detailed differentiation of the phenomenon (inside or outside the theory), the status of the theory, research strategy, and methods.

As a result, the contribution to the literature is a portfolio of case study research designs explicating their unique contributions to theory. The contribution of this paper lies in a fine-grained analysis of the interplay of methods and theory (van Maanen et al. 2007 ) and the methodological fit (Edmondson and McManus 2007 ) of case study designs and the continuum of theory. It demonstrates that different designs have various strengths and that there is a fit between case study designs and different points on a theory continuum. If there is no clarity as to whether a case study design aims at creating, elaborating, extending, or testing theory, the contribution to theory is difficult to identify for authors, reviewers, and readers. Consequently, this paper aims to clarify at which point of the continuum of theory case study research designs can provide distinct contributions that can be identified beyond their traditionally claimed exploratory character.

2 Differences across case study design: a portfolio approach

Only few papers have compared case study research designs so far. In all of these comparisons, the number of designs differs as well as the issues under consideration. In an early debate between Dyer and Wilkins ( 1991 ) and Eisenhardt ( 1991 ), Dyer and Wilkins compared the case study research design by Eisenhardt ( 1989 ) with “classical” case studies. The core of the debate concerns a difference between in-depth single case studies (classical case study) to a focus on the comparison of multiple cases. Dyer and Wilkins ( 1991 : 614) claim that the essence of a case study lies in the careful study of a single case to identify new relationships and, as a result, question the Eisenhardt approach which puts a lot of emphasis on comparison of multiple cases. Eisenhardt, on the contrary, claims that multiple cases allow replication between cases and is, therefore, seen as a means of corroboration of propositions (Eisenhardt 1991 ). Classical case studies prefer deep descriptions of a single case, considering the context to reveal insights into the single case and by that elaborate new theories. The comparison of multiple cases, therefore, tends—in the opinion of Dyer and Wilkens—to surface descriptions. This weakens the possibility of context-related, rich descriptions. While, in classic case study, good stories are the aim, the development of good constructs and their relationships is aimed in Eisenhardt’s approach. Eisenhardt ( 1991 : 627) makes a strong plea on more methodological rigor in case study research, while Dyer and Wilkins ( 1991 : 613) criticize that the new approach “… includes many of the attributes of hypothesis-testing research (e.g., sampling and controls).”

Dooley ( 2002 : 346) briefly takes the case study research designs by Yin (1994) and Eisenhardt ( 1989 ) as exemplars of how the processes of case study research can be applied. The approach by Eisenhardt is seen as an exemplar that advances conceptualization and operationalization in the phases of theory-building, while the approach by Yin is seen as exemplar that advances minimally conceptualized and operationalized existing theory.

Baxter and Jack ( 2008 ) describe the designs by Yin (2003) and Stake ( 1995 ) to demonstrate key elements of qualitative case study. The authors outline and carefully compare the approaches by Yin and Stake in conducting the research process, neglecting philosophical differences and theoretical goals.

Piekkari et al. ( 2009 ) outline the methodological richness of case study research using the approaches of Yin et al. (1998), and Stake. They specifically exhibit the role of philosophical assumptions, establishing differences in conventionally accepted practices of case study research in published papers. The authors analyze 135 published case studies in four international business journals. The analysis reveals that, in contrast to the richness of case study approaches, the majority of published case studies draw on positivistic foundations and are narrowly declared as explorative with a lack of clarity of the theoretical purpose of the case study. Case studies are often designed as multiple case studies with cross-sectional designs based on interviews. In addition to the narrow use of case study research, the authors find out that “… most commonly cited methodological literature is not consistently followed” (Piekkari et al. 2009 : 567).

Welch et al. ( 2011 ) develop a typology of theorizing modes in case study methods. Based on the two dimensions “contextualization” and “causal explanation”, they differentiate in their typology between inductive theory-building (Eisenhardt), interpretive sensemaking (Stake), natural experiment (Yin), and contextualised explanation (Ragin/Bhaskar). The typology is used to analyze 199 case studies from three highly ranked journals over a 10-year period for whether the theorizing modes are exercised in the practice of publishing case studies. As a result, the authors identify a strong emphasis on the exploratory function of case studies, neglecting the richness of case study methods to challenge, refine, verify, and test theories (Welch et al. 2011 : 755). In addition, case study methods are not consistently related to theory contribution: “By scrutinising the linguistic elements of texts, we found that case researchers were not always clear and consistent in the way that they wrote up their theorising purpose and process” (Welch et al. 2011 : 756).

As a result, the comparisons reveal a range of case study designs which are rarely discussed. In contrast, published case studies are mainly introduced as exploratory design. Explanatory, interpretivist, and critical/reflexive designs are widely neglected, narrowing the possible applications of case study research. In addition, comparisons containing an analysis of published case studies reveal a low degree in accuracy when applying case study methods.

What is missing is a comparison of case study research designs with regard to differences in the contribution to theory. Case study designs have different purposes in theory contribution. Confusing these potential contributions by inconsistently utilizing the appropriate methods weakens the contribution of case studies to scientific progress and, by that, damages the reputation of case studies.

To conduct such a comparison, I consider the four case study research approaches of Yin, Eisenhardt, Burawoy, and Stake for the following reasons.

These approaches are the main representatives of case study research design outlined in the comparisons elaborated above (Baxter and Jack 2008 ; Dooley 2002 ; Dyer and Wilkins 1991 ; Piekkari et al. 2009 ; Welch et al. 2011 ). I follow especially the argument by Piekkari et al. ( 2009 ) that these approaches contain a broad spectrum of methodological foundations of exploratory, explanatory, interpretivist, and critical/reflexive designs. The chosen approaches have an explicit and detailed methodology which can be reconstructed and compared with regard to their theory contribution. Although there are variations in the application of the designs, to the best of my knowledge, the designs represent the spectrum of case study methodologies. A comparison of these methodologies revealed main distinguishable differences. To highlight these main differences, I summarized these differences into labels of “no theory first”; “gaps and holes”; “social construction of reality”; and “anomalies”.

I did not consider descriptions of case study research in text books which focus more or less on general descriptions of the common characteristics of case studies, but do not emphasize differences in methodologies and theory contribution. In addition, I did not consider so-called “home grown” designs (Eisenhardt 1989 : 534) which lack a systematic and explicit demonstration of the methodology and where “… the hermeneutic process of inference—how all these interviews, archival records, and notes were assembled into a coherent whole, what was counted and what was discounted—remains usually hidden from the reader” (Fiss 2009 : 425).

Finally, although often cited in the methodological section of case studies, books are not considered which concentrate on data analysis in qualitative research per se (Miles et al. 2014 ; Corbin and Strauss 2015 ). Therefore, to analyze the contribution of case study research to the scientific development, it needs to compare explicit methodology. This comparison will be outlined in the following sections with regard to main methodological steps: the role of the case, the collection of data, and the analysis of data.

2.1 Case study research design 1: no theory first

A popular template for building theory from case studies is a paper by Eisenhardt ( 1989 ). It follows a dramaturgy with a precise order of single steps for constructing a case study and is one of the most cited papers in methods sections (Ravenswood 2011 ). This is impressive for two reasons. On the one hand, Eisenhardt herself has provided a broader spectrum of case study research designs in her own empirical papers, for example, by combining theory-building and theory elaboration (Bingham and Eisenhardt 2011 ). On the other hand, she “updated” her design in a paper with Graebner (Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007 ), particularly by extending the range of inductive theory-building. These developments do not seem to be seriously considered by most authors, as differences and elaborations of this spectrum are rarely found in publications. Therefore, in the following, I focus on the standards provided by Eisenhardt ( 1989 ) and Eisenhardt and Graebner ( 2007 ) as exemplary guidelines.

Eisenhardt follows the ideal of ‘no theory first’ to capture the richness of observations without being limited by a theory. The research question may stem from a research gap meaning that the research question is of relevance. Tentative a priori constructs or variables guide the investigation, but no relationships between such constructs or variables are assumed so far: “Thus, investigators should formulate a research problem and possibly specify some potentially important variables, with some reference to extant literature. However, they should avoid thinking about specific relationships between variables and theories as much as possible, especially at the outset of the process” (Eisenhardt 1989 : 536).

Cases are chosen for theoretical reasons: for the likelihood that the cases offer insights into the phenomenon of interest. Theoretical sampling is deemed appropriate for illuminating and extending constructs and identifying relationships for the phenomenon under investigation (Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007 ). Cases are sampled if they provide an unusual phenomenon, replicate findings from other cases, use contrary replication, and eliminate alternative explanations.

With respect to data collection, qualitative data are the primary choice. Data collection is based on triangulation, where interviews, documents, and observations are often combined. A combination of qualitative data and quantitative data is possible as well (Eisenhardt 1989 : 538). Data analysis is conducted via the search for within-case patterns and cross-case patterns. Systematic procedures are conducted to compare the emerging constructs and relationships with the data, eventually leading to new theory.

A good exemplar for this design is the investigation of technology collaborations (Davis and Eisenhardt 2011 ). The purpose of this paper is to understand processes by which technology collaborations support innovations. Eight technology collaborations among ten firms were sampled for theoretical reasons. Qualitative and quantitative data were used from semi-structured interviews, public and private data, materials provided by informants, corporate intranets, and business publications. The data was measured, coded, and triangulated. Writing case histories was a basis for within-case and cross-case analysis. Iteration between cases and emerging theory and considering the relevant literature provided the basis for the development of a theoretical framework.