Rational Decision Making: The 7-Step Process for Making Logical Decisions

Published: October 17, 2023

Psychology tells us that emotions drive our behavior, while logic only justifies our actions after the fact . Marketing confirms this theory. Humans associate the same personality traits with brands as they do with people — choosing your favorite brand is like choosing your best friend or significant other. We go with the option that makes us feel something.

But emotions can cloud your reasoning, especially when you need to do something that could cause internal pain, like giving constructive criticism, or moving on from something you’re attached to, like scrapping a favorite topic from your team's content calendar.

![when problem solving and making decisions your rational Download Now: How to Be More Productive at Work [Free Guide + Templates]](https://no-cache.hubspot.com/cta/default/53/be08853d-7ccb-4ab6-ba13-ef66a1d9b4ff.png)

There’s a way to suppress this emotional bias, though. It’s a thought process that’s completely objective and data-driven. It's called the rational decision making model, and it will help you make logically sound decisions even in situations with major ramifications , like pivoting your entire blogging strategy.

But before we learn each step of this powerful process, let’s go over what exactly rational decision making is and why it’s important.

What is Rational Decision Making?

Rational decision making is a problem-solving methodology that factors in objectivity and logic instead of subjectivity and intuition to achieve a goal. The goal of rational decision making is to identify a problem, pick a solution between multiple alternatives, and find an answer.

Rational decision making is an important skill to possess, especially in the digital marketing industry. Humans are inherently emotional, so our biases and beliefs can blur our perception of reality. Fortunately, data sharpens our view. By showing us how our audience actually interacts with our brand, data liberates us from relying on our assumptions to determine what our audience likes about us.

Rational Decision Making Model: 7 Easy Steps(+ Examples)

1. Verify and define your problem.

To prove that you actually have a problem, you need evidence for it. Most marketers think data is the silver bullet that can diagnose any issue in our strategy, but you actually need to extract insights from your data to prove anything. If you don’t, you’re just looking at a bunch of numbers packed into a spreadsheet.

To pinpoint your specific problem, collect as much data from your area of need and analyze it to find any alarming patterns or trends.

“After analyzing our blog traffic report, we now know why our traffic has plateaued for the past year — our organic traffic increases slightly month over month but our email and social traffic decrease.”

2. Research and brainstorm possible solutions for your problem.

Expanding your pool of potential solutions boosts your chances of solving your problem. To find as many potential solutions as possible, you should gather plenty of information about your problem from your own knowledge and the internet. You can also brainstorm with others to uncover more possible solutions.

Potential Solution 1: “We could focus on growing organic, email, and social traffic all at the same time."

Potential Solution 2: “We could focus on growing email and social traffic at the same time — organic traffic already increases month over month while traffic from email and social decrease.”

Potential Solution 3: "We could solely focus on growing social traffic — growing social traffic is easier than growing email and organic traffic at the same time. We also have 2 million followers on Facebook, so we could push our posts to a ton of readers."

Potential Solution 4: "We could solely focus on growing email traffic — growing email traffic is easier than growing social and organic traffic at the same time. We also have 250,000 blog subscribers, so we could push our posts to a ton of readers."

Potential Solution 5: "We could solely focus on growing organic traffic — growing organic traffic is easier than growing social and email traffic at the same time. We also just implemented a pillar-cluster model to boost our domain’s authority, so we could attract a ton of readers from Google."

3. Set standards of success and failure for your potential solutions.

Setting a threshold to measure your solutions' success and failure lets you determine which ones can actually solve your problem. Your standard of success shouldn’t be too high, though. You’d never be able to find a solution. But if your standards are realistic, quantifiable, and focused, you’ll be able to find one.

“If one of our solutions increases our total traffic by 10%, we should consider it a practical way to overcome our traffic plateau.”

4. Flesh out the potential results of each solution.

Next, you should determine each of your solutions’ consequences. To do so, create a strength and weaknesses table for each alternative and compare them to each other. You should also prioritize your solutions in a list from best chance to solve the problem to worst chance.

Potential Result 1: ‘Growing organic, email, and social traffic at the same time could pay a lot of dividends, but our team doesn’t have enough time or resources to optimize all three channels.”

Potential Result 2: “Growing email and social traffic at the same time would marginally increase overall traffic — both channels only account for 20% of our total traffic."

Potential Result 3: “Growing social traffic by posting a blog post everyday on Facebook is challenging because the platform doesn’t elevate links in the news feed and the channel only accounts for 5% of our blog traffic. Focusing solely on social would produce minimal results.”

Potential Result 4: “Growing email traffic by sending two emails per day to our blog subscribers is challenging because we already send one email to subscribers everyday and the channel only accounts for 15% of our blog traffic. Focusing on email would produce minimal results.”

Potential Result 5: “Growing organic traffic by targeting high search volume keywords for all of our new posts is the easiest way to grow our blog’s overall traffic. We have a high domain authority, Google refers 80% of our total traffic, and we just implemented a pillar-cluster model. Focusing on organic would produce the most results.”

5. Choose the best solution and test it.

Based on the evaluation of your potential solutions, choose the best one and test it. You can start monitoring your preliminary results during this stage too.

“Focusing on organic traffic seems to be the most effective and realistic play for us. Let’s test an organic-only strategy where we only create new content that has current or potential search volume and fits into our pillar cluster model.”

6. Track and analyze the results of your test.

Track and analyze your results to see if your solution actually solved your problem.

“After a month of testing, our blog traffic has increased by 14% and our organic traffic has increased by 21%.”

7. Implement the solution or test a new one.

If your potential solution passed your test and solved your problem, then it’s the most rational decision you can make. You should implement it to completely solve your current problem or any other related problems in the future. If the solution didn’t solve your problem, then test another potential solution that you came up with.

“The results from solely focusing on organic surpassed our threshold of success. From now on, we’re pivoting to an organic-only strategy, where we’ll only create new blog content that has current or future search volume and fits into our pillar cluster model.”

Avoid Bias With A Rational Decision Making Process

As humans, it’s natural for our emotions to take over your decision making process. And that’s okay. Sometimes, emotional decisions are better than logical ones. But when you really need to prioritize logic over emotion, arming your mind with the rational decision making model can help you suppress your emotion bias and be as objective as possible.

Don't forget to share this post!

Related articles.

Decision Trees: A Simple Tool to Make Radically Better Decisions

Mental Models: The Ultimate Guide

The Ultimate Guide to Decision Making

![when problem solving and making decisions your rational How Product Packaging Influences Buying Decisions [Infographic]](https://blog.hubspot.com/hs-fs/hub/53/file-2411322621-png/00-Blog_Thinkstock_Images/product-packaging.png)

How Product Packaging Influences Buying Decisions [Infographic]

The Five Stages of the Consumer Decision-Making Process Explained

Outline your company's marketing strategy in one simple, coherent plan.

Marketing software that helps you drive revenue, save time and resources, and measure and optimize your investments — all on one easy-to-use platform

The Ultimate Guide to Rational Decision-Making (With Steps)

Making decisions is an integral part of our lives. However, how many times do we really stop to think whether our choices are rational or not?

This article dives deep into the concept of rational decision-making, its importance, real-life examples, steps involved, factors influencing it, ways to enhance your skills, potential challenges, and how cognitive biases impact it. Let’s dive in.

What is Rational Decision-Making?

Rational decision-making, at its core, is a multi-step process used to make choices that are logical, informed, and objective. It involves identifying a decision problem, gathering information, evaluating alternatives, and selecting the most rational choice. This is a stark contrast to decisions based on subjectivity or intuition, which may often rely on feelings, emotions, or personal biases.

The goal of rational decision-making is to reach decisions that support your objectives in the most optimal way. The basis of this process is rationality—a concept that propels us to make decisions that provide the maximum benefit or, in other words, the best possible outcome. Rationality encourages us to follow a path that aligns with our goals and values while making decisions. It’s an antidote to impulsive choices or decisions clouded by bias and personal emotions.

While intuitive decisions can sometimes lead to effective outcomes, especially in situations demanding quick responses, rational decision-making allows us to consider all available options, analyze their potential consequences, and make an informed choice. This often leads to decisions that are more aligned with our long-term goals and less likely to result in unintended consequences.

Why is Rational Decision-Making Important?

Rational decision-making is the cornerstone of effective problem-solving and critical thinking. It helps us to make informed choices that are not only beneficial but also ethical, a crucial aspect in both personal and professional life.

In business, rational decision-making can lead to strategies that maximize profit, minimize risk, and promote organizational growth. It ensures resource optimization by aligning decisions with business objectives. Rationality ensures that every decision is data-driven, increasing the likelihood of successful outcomes.

On a personal level, rational decision-making can help us make better choices about our health, finances, relationships, and more. It enables us to make choices that align with our values and life goals, improving our overall quality of life.

Examples of Using Rational Decision-Making

Let’s see how rational decision-making manifests in various spheres.

Business: A company looking to launch a new product will employ rational decision-making. They’ll conduct market research, analyze competitor products, evaluate their resources, and predict potential profits before making a decision. This ensures the decision is based on facts and not just intuition.

Leadership: Leaders use rational decision-making while shaping policies or resolving conflicts. A school principal, for instance, may have to decide whether to enforce a strict no-mobile policy.

They’ll consider the pros and cons, consult with teachers, parents, and students, and make a decision that is most beneficial for the school’s academic environment.

Personal Finance: An individual considering their retirement savings plan would utilize rational decision-making. They might begin by understanding the importance of saving for retirement and gathering information about various options like 401(k)s, IRAs, or traditional savings accounts.

They would evaluate these alternatives, considering factors like potential growth, risk level, and tax benefits. The decision would be based on their financial situation, retirement goals, and risk tolerance, ensuring their choice is not impulsive but grounded in careful consideration and analysis.

Steps Involved in Rational Decision-Making

The rational decision-making process comprises several key steps. Here’s a rundown:

1. Identify the Decision

The first step in rational decision-making is acknowledging that a decision is required. The decision is usually a problem but can also be an opportunity. This is the foundational stage where the problem or situation is recognized, and the need for a decision becomes apparent.

You can’t make a rational decision unless you know exactly what the problem is and the context of the decision that needs to be made. Ask yourself questions such as:

- Why does a decision need to be made?

- What consequences will unfold if no decision is made?

- What desired outcome are we aiming for?

- What stands in the way of achieving it?

Take, for instance, a business observing declining profits. The company identifies the problem and realizes that strategic decisions need to be made to address this issue.

It might ask: What is the reason behind the decreasing profits? What will happen if the situation is not addressed? What are our financial goals, and what is impeding us from achieving them? This level of detailed understanding and clarity sets the stage for the subsequent steps of the decision-making process.

2. Gather Information

Once the decision has been identified, the next step is to gather relevant information about it. This could include data analysis, research, consultations with experts, surveys, etc.

Using the previous example, the business might look into financial statements, assess market trends, and consider feedback from customers. A thorough and unbiased collection of data is critical as it forms the backbone of a rational decision.

3. Identify Alternatives

The third step involves generating a list of potential alternatives. There is often more than one way to address a problem or situation, so it’s important to consider different approaches and options.

For the business facing decreasing profits, alternatives could include cost-cutting, investing in new marketing strategies, introducing new products, or even merging with another company. Creativity and open-mindedness are key in this stage to ensure a wide range of options.

4. Evaluate Alternatives

After generating alternatives, the next crucial step is to evaluate each one. This stage involves a systematic analysis of the pros and cons, feasibility, potential impact, and other factors pertinent to each option. Here, establishing your decision criteria—such as cost-effectiveness, scalability, risk level, and potential return—is key. Once established, these criteria need to be weighed based on their importance to solving the problem at hand.

For example, a business might establish criteria like cost, projected return, and alignment with company values. These criteria would be applied to evaluate the potential impact of different marketing strategies, the feasibility of cost-cutting measures, or the implications of a merger.

This systematic evaluation process, underpinned by established and weighted decision criteria, enables a business to compare and contrast different options effectively. It assists in determining which alternative aligns best with the defined criteria and thus holds the highest potential for success.

5. Choose an Alternative

This step involves making the actual decision among the evaluated alternatives. Typically, the best alternative is the one with the greatest likelihood of solving the issue, paired with the lowest degree of risk.

It’s where the business might choose the most cost-effective marketing strategy that is expected to reach the widest audience. While this stage concludes with a decision, the rational decision-making process is not yet complete.

6. Take Action

This is where the chosen alternative is implemented. It involves carrying out the decision and monitoring its progress.

For the business, this would mean launching the selected marketing strategy and keeping a close eye on metrics such as customer engagement, sales, and profit margins. It’s important to remember that this stage might involve overcoming obstacles and making adjustments as necessary.

7. Review the Decision

The final step of the process is to review and evaluate the results of the decision. This includes analyzing whether the decision has resolved the problem or situation and, if not, considering what adjustments need to be made.

In our business example, this could mean assessing whether the new marketing strategy has indeed increased profits. If it hasn’t, the business might need to revisit previous steps of the process to identify and implement a new decision.

These steps make up the backbone of the rational decision-making process, enabling us to systematically approach our choices, ensuring they are backed by logic and evidence.

Assumptions for Using a Rational Decision-Making Model

To effectively utilize the rational decision-making process, it’s necessary to make several key assumptions. These assumptions create a baseline for the decision-making process and help ensure its effective implementation:

- Complete Information: One must assume that all the information needed to make the decision is available and accessible. This includes details about the problem, potential solutions, and their outcomes.

- Decision-Maker Rationality: The person making the decision is assumed to be rational, meaning they are objective, logical, and aim to make the best choice based on the information available.

- Clear Objectives: The decision-maker is assumed to have clear and consistent objectives or goals that guide the decision-making process.

- Time and Resources: It’s assumed that the decision-maker has adequate time and resources to gather information, evaluate alternatives, and make a decision.

- Decision-Maker Independence: The decision-maker is assumed to have the freedom and authority to make the decision without undue influence or restrictions.

- Stable Environment: The environment in which the decision is being made is assumed to be stable, allowing for reliable predictions about the consequences of each alternative.

- Logical Evaluation: It’s assumed that the decision-maker can logically evaluate the pros and cons of each alternative, weigh them against each other, and make a rational choice.

Other Rational Decision-Making Models

While the steps above cover the basics of rational decision-making, there are several rational decision-making models that have been developed by scholars and researchers over the years.

These models provide structured approaches to making decisions based on logical reasoning and analysis. Here are a few examples:

- The Rational Economic Model: This model assumes that individuals make decisions by maximizing their utility or satisfaction, considering all available information, and weighing the costs and benefits of different alternatives.

- The Bounded Rationality Model: Proposed by Herbert Simon, this model recognizes that humans have limitations in processing information and making fully rational decisions. It suggests that individuals make decisions that are “good enough” rather than optimal, taking into account their cognitive constraints and the available information.

- The Normative Decision Model: This model focuses on the ideal decision-making process, providing a step-by-step framework for making rational decisions. It emphasizes gathering complete information, considering all alternatives, and evaluating the potential outcomes before selecting the best option.

- The Garbage Can Model: This model views decision-making as a chaotic process that occurs in organizations. It suggests that decisions often result from a combination of problems, solutions, participants, and circumstances coming together in a “garbage can” and being resolved opportunistically.

- The Prospect Theory: Proposed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, this model challenges the assumptions of rational decision-making by considering how individuals assess and weigh potential gains and losses. It suggests that people tend to be risk-averse when it comes to gains but risk-seeking when it comes to losses.

These are just a few examples of rational decision-making models. Each model offers a unique perspective and set of principles for approaching decision-making tasks. The choice of model depends on the context, problem complexity, available information, and the decision-makers preferences and constraints.

Factors Influencing Rational Decision-Making

While the idea of making a completely rational decision sounds perfect, in reality, our decisions are often influenced by various factors.

- Information Availability: The amount and quality of information at our disposal can greatly influence our decisions. With limited or incorrect information, we may end up making less-than-optimal decisions.

- Time Constraints: Often, we are pressed for time while making decisions. Under such constraints, we might not go through the full rational decision-making process.

- Cognitive Limitations: Our cognitive capacity to process information and make decisions is limited. We can be overwhelmed with too many alternatives or complex decision scenarios.

- Emotions: Our emotions often play a part in our decisions. We might make irrational choices under emotional distress.

Impact of Cognitive Biases on Rational Decision-Making

Cognitive biases can seriously impact our rational decision-making abilities. These mental shortcuts or “biases” can lead us to make decisions that are not in our best interest.

For instance, confirmation bias can make us pay more attention to information that confirms our pre-existing beliefs and ignore contradicting evidence. Similarly, the anchoring bias can cause us to rely heavily on the first piece of information we receive when making decisions.

Cognitive biases often lead to irrational choices. Being aware of these biases is the first step towards mitigating their impact on our decision-making process.

Potential Challenges in Rational Decision-Making

Rational decision-making, despite its merits, isn’t without its challenges. Some of these include:

- Information Overload: In an age of data deluge, filtering through massive amounts of information to make decisions can be overwhelming.

- Analysis Paralysis: Overanalyzing or overthinking can lead to indecision or delays in decision-making.

- Unpredictable Outcomes: Even with a thorough analysis, outcomes can be unpredictable due to the dynamic nature of our environment.

Developing Rational Decision-Making Skills

Wondering how to become better at making rational decisions? Here are some tips to get you going:

- Improve Critical Thinking: Critical thinking allows us to objectively analyze information and logically derive conclusions. By developing your critical thinking skills, you can better evaluate decision alternatives.

- Practice Mindfulness: Being aware of your thoughts and emotions can help you identify when they are clouding your decision-making process.

- Use Decision-Making Models: Decision-making models can provide a structured approach to rational decision-making. They can help guide you through complex decision scenarios.

Remember, developing rational decision-making skills takes time and practice. Stay patient and keep practicing.

Frequently Asked Questions

Rational decision-making is a structured, logical process that uses evidence and analysis. Intuitive decision-making relies on instinct and gut feelings.

Yes, rational decision-making can be applied in personal situations like choosing a career, managing finances, or making health-related decisions.

Yes, decision-making models like SWOT analysis, decision trees, or cost-benefit analysis can provide structured approaches to enhance rationality.

Wrapping Up

Rational decision-making is a skill that can transform our personal and professional lives, steering us toward more informed and effective choices. Though challenges exist, with awareness and practice, we can significantly improve our decision-making prowess.

By understanding the nuances of rational decision-making, we not only enhance our decision-making abilities but also become better thinkers, planners, and problem-solvers. Now, isn’t that a step towards a more informed and empowered life?

Your Might Also Like

10 goal-setting tips to boost productivity and personal development.

Effective Goal Setting: Unlock Your Full Potential

Smart goals: a comprehensive guide to goal setting and achievement.

- Get started with computers

- Learn Microsoft Office

- Apply for a job

- Improve my work skills

- Design nice-looking docs

- Getting Started

- Smartphones & Tablets

- Typing Tutorial

- Online Learning

- Basic Internet Skills

- Online Safety

- Social Media

- Zoom Basics

- Google Docs

- Google Sheets

- Career Planning

- Resume Writing

- Cover Letters

- Job Search and Networking

- Business Communication

- Entrepreneurship 101

- Careers without College

- Job Hunt for Today

- 3D Printing

- Freelancing 101

- Personal Finance

- Sharing Economy

- Decision-Making

- Graphic Design

- Photography

- Image Editing

- Learning WordPress

- Language Learning

- Critical Thinking

- For Educators

- Translations

- Staff Picks

- English expand_more expand_less

Critical Thinking and Decision-Making - What is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking and decision-making -, what is critical thinking, critical thinking and decision-making what is critical thinking.

Critical Thinking and Decision-Making: What is Critical Thinking?

Lesson 1: what is critical thinking, what is critical thinking.

Critical thinking is a term that gets thrown around a lot. You've probably heard it used often throughout the years whether it was in school, at work, or in everyday conversation. But when you stop to think about it, what exactly is critical thinking and how do you do it ?

Watch the video below to learn more about critical thinking.

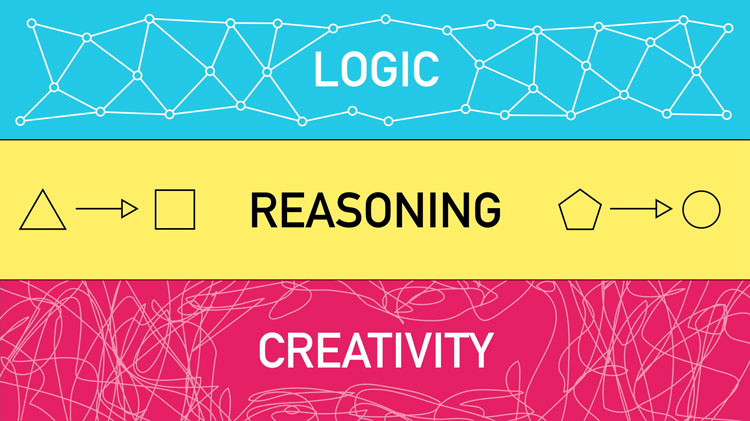

Simply put, critical thinking is the act of deliberately analyzing information so that you can make better judgements and decisions . It involves using things like logic, reasoning, and creativity, to draw conclusions and generally understand things better.

This may sound like a pretty broad definition, and that's because critical thinking is a broad skill that can be applied to so many different situations. You can use it to prepare for a job interview, manage your time better, make decisions about purchasing things, and so much more.

The process

As humans, we are constantly thinking . It's something we can't turn off. But not all of it is critical thinking. No one thinks critically 100% of the time... that would be pretty exhausting! Instead, it's an intentional process , something that we consciously use when we're presented with difficult problems or important decisions.

Improving your critical thinking

In order to become a better critical thinker, it's important to ask questions when you're presented with a problem or decision, before jumping to any conclusions. You can start with simple ones like What do I currently know? and How do I know this? These can help to give you a better idea of what you're working with and, in some cases, simplify more complex issues.

Real-world applications

Let's take a look at how we can use critical thinking to evaluate online information . Say a friend of yours posts a news article on social media and you're drawn to its headline. If you were to use your everyday automatic thinking, you might accept it as fact and move on. But if you were thinking critically, you would first analyze the available information and ask some questions :

- What's the source of this article?

- Is the headline potentially misleading?

- What are my friend's general beliefs?

- Do their beliefs inform why they might have shared this?

After analyzing all of this information, you can draw a conclusion about whether or not you think the article is trustworthy.

Critical thinking has a wide range of real-world applications . It can help you to make better decisions, become more hireable, and generally better understand the world around you.

/en/problem-solving-and-decision-making/why-is-it-so-hard-to-make-decisions/content/

Our content is reader-supported. Things you buy through links on our site may earn us a commission

Join our newsletter

Never miss out on well-researched articles in your field of interest with our weekly newsletter.

- Project Management

- Starting a business

Get the latest Business News

Mastering problem solving and decision making.

© Copyright Carter McNamara, MBA, PhD, Authenticity Consulting, LLC .

Sections of This Topic Include

- Test – What is Your Personal Decision-Making Style?

- Guidelines to Rational Problem Solving and Decision-Making

- Rational Versus Organic Approach to Problem Solving and Decision Making

- General Guidelines to Problem Solving and Decision-Making

- Various Methods and Tools for Problem-Solving and Decision Making

- General Resources for Problem-Solving and Decision Making

Also, consider

- Related Library Topics

- (Also see the closely related topics Decision Making , Group-Based Problem Solving, and Decision Making and Planning — Basics .)

What is Your Personal Decision-Making Style?

There are many styles of making decisions, ranging from very rational and linear to organic and unfolding. Take this online assessment to determine your own style.

Discover Your Decision-Making Style

Do you want to improve or polish your style? Consider the many guidelines included below.

Guidelines to Problem-Solving and Decision Making (Rational Approach)

Much of what people do is solve problems and make decisions. Often, they are “under the gun”, stressed, and very short of time. Consequently, when they encounter a new problem or decision they must make, they react with a decision that seemed to work before. It’s easy with this approach to get stuck in a circle of solving the same problem over and over again. Therefore, it’s often useful to get used to an organized approach to problem-solving and decision-making.

Not all problems can be solved and decisions made by the following, rather rational approach. However, the following basic guidelines will get you started. Don’t be intimidated by the length of the list of guidelines. After you’ve practiced them a few times, they’ll become second nature to you — enough that you can deepen and enrich them to suit your own needs and nature.

(Note that it might be more your nature to view a “problem” as an “opportunity”. Therefore, you might substitute “problem” for “opportunity” in the following guidelines.)

1. Define the problem

This is often where people struggle. They react to what they think the problem is. Instead, seek to understand more about why you think there’s a problem.

Define the problem: (with input from yourself and others). Ask yourself and others, the following questions:

- What can you see that causes you to think there’s a problem?

- Where is it happening?

- How is it happening?

- When is it happening?

- With whom is it happening? (HINT: Don’t jump to “Who is causing the problem?” When we’re stressed, blaming is often one of our first reactions. To be an effective manager, you need to address issues more than people.)

- Why is it happening?

- Write down a five-sentence description of the problem in terms of “The following should be happening, but isn’t …” or “The following is happening and should be: …” As much as possible, be specific in your description, including what is happening, where, how, with whom and why. (It may be helpful at this point to use a variety of research methods.)

Defining complex problems:

If the problem still seems overwhelming, break it down by repeating steps 1-7 until you have descriptions of several related problems.

Verifying your understanding of the problems:

It helps a great deal to verify your problem analysis for conferring with a peer or someone else.

Prioritize the problems:

If you discover that you are looking at several related problems, then prioritize which ones you should address first.

Note the difference between “important” and “urgent” problems. Often, what we consider to be important problems to consider are really just urgent problems. Important problems deserve more attention. For example, if you’re continually answering “urgent” phone calls, then you’ve probably got a more “important” problem and that’s to design a system that screens and prioritizes your phone calls.

Understand your role in the problem:

Your role in the problem can greatly influence how you perceive the role of others. For example, if you’re very stressed out, it’ll probably look like others are, too, or, you may resort too quickly to blaming and reprimanding others. Or, you are feel very guilty about your role in the problem, you may ignore the accountabilities of others.

2. Look at potential causes for the problem

- It’s amazing how much you don’t know about what you don’t know. Therefore, in this phase, it’s critical to get input from other people who notice the problem and who are affected by it.

- It’s often useful to collect input from other individuals one at a time (at least at first). Otherwise, people tend to be inhibited about offering their impressions of the real causes of problems.

- Write down your opinions and what you’ve heard from others.

- Regarding what you think might be performance problems associated with an employee, it’s often useful to seek advice from a peer or your supervisor in order to verify your impression of the problem.

- Write down a description of the cause of the problem in terms of what is happening, where, when, how, with whom, and why.

3. Identify alternatives for approaches to resolve the problem

At this point, it’s useful to keep others involved (unless you’re facing a personal and/or employee performance problem). Brainstorm for solutions to the problem. Very simply put, brainstorming is collecting as many ideas as possible, and then screening them to find the best idea. It’s critical when collecting the ideas to not pass any judgment on the ideas — just write them down as you hear them. (A wonderful set of skills used to identify the underlying cause of issues is Systems Thinking.)

4. Select an approach to resolve the problem

- When selecting the best approach, consider:

- Which approach is the most likely to solve the problem for the long term?

- Which approach is the most realistic to accomplish for now? Do you have the resources? Are they affordable? Do you have enough time to implement the approach?

- What is the extent of risk associated with each alternative?

(The nature of this step, in particular, in the problem solving process is why problem solving and decision making are highly integrated.)

5. Plan the implementation of the best alternative (this is your action plan)

- Carefully consider “What will the situation look like when the problem is solved?”

- What steps should be taken to implement the best alternative to solving the problem? What systems or processes should be changed in your organization, for example, a new policy or procedure? Don’t resort to solutions where someone is “just going to try harder”.

- How will you know if the steps are being followed or not? (these are your indicators of the success of your plan)

- What resources will you need in terms of people, money, and facilities?

- How much time will you need to implement the solution? Write a schedule that includes the start and stop times, and when you expect to see certain indicators of success.

- Who will primarily be responsible for ensuring the implementation of the plan?

- Write down the answers to the above questions and consider this as your action plan.

- Communicate the plan to those who will involved in implementing it and, at least, to your immediate supervisor.

(An important aspect of this step in the problem-solving process is continual observation and feedback.)

6. Monitor implementation of the plan

Monitor the indicators of success:

- Are you seeing what you would expect from the indicators?

- Will the plan be done according to schedule?

- If the plan is not being followed as expected, then consider: Was the plan realistic? Are there sufficient resources to accomplish the plan on schedule? Should more priority be placed on various aspects of the plan? Should the plan be changed?

7. Verify if the problem has been resolved or not

One of the best ways to verify if a problem has been solved or not is to resume normal operations in the organization. Still, you should consider:

- What changes should be made to avoid this type of problem in the future? Consider changes to policies and procedures, training, etc.

- Lastly, consider “What did you learn from this problem-solving?” Consider new knowledge, understanding, and/or skills.

- Consider writing a brief memo that highlights the success of the problem-solving effort, and what you learned as a result. Share it with your supervisor, peers and subordinates.

Rational Versus Organic Approach to Problem Solving

A person with this preference often prefers using a comprehensive and logical approach similar to the guidelines in the above section. For example, the rational approach, described below, is often used when addressing large, complex matters in strategic planning.

- Define the problem.

- Examine all potential causes for the problem.

- Identify all alternatives to resolve the problem.

- Carefully select an alternative.

- Develop an orderly implementation plan to implement the best alternative.

- Carefully monitor the implementation of the plan.

- Verify if the problem has been resolved or not.

A major advantage of this approach is that it gives a strong sense of order in an otherwise chaotic situation and provides a common frame of reference from which people can communicate in the situation. A major disadvantage of this approach is that it can take a long time to finish. Some people might argue, too, that the world is much too chaotic for the rational approach to be useful.

Some people assert that the dynamics of organizations and people are not nearly so mechanistic as to be improved by solving one problem after another. Often, the quality of an organization or life comes from how one handles being “on the road” itself, rather than the “arriving at the destination.” The quality comes from the ongoing process of trying, rather than from having fixed a lot of problems. For many people, it is an approach to organizational consulting. The following quote is often used when explaining the organic (or holistic) approach to problem solving.

“All the greatest and most important problems in life are fundamentally insoluble … They can never be solved, but only outgrown. This “outgrowing” proves that further investigation to require a new level of consciousness. Some higher or wider interest appeared on the horizon and through this broadening of outlook, the insoluble lost its urgency. It was not solved logically in its own terms, but faded when confronted with a new and stronger life urge.” From Jung, Carl, Psychological Types (Pantheon Books, 1923)

A major advantage of the organic approach is that it is highly adaptable to understanding and explaining the chaotic changes that occur in projects and everyday life. It also suits the nature of people who shun linear and mechanistic approaches to projects. The major disadvantage is that the approach often provides no clear frame of reference around which people can communicate, feel comfortable and measure progress toward solutions to problems.

Additional Guidelines for Problem-Solving and Decision Making

Recommended articles.

- Ten Tips for Beefing Up Your Problem-Solving Tool Box

- Problem Solving Techniques (extensive overview of various approaches)

- Key Questions to Ask Before Selecting a Solution to a Business Problem

Additional Articles

- Problem-solving and Decision-Making:

- Top 5 Tips to Improve Concentration

- Problem Solving and Decision Making – 12 Great Tips!

- Powerful Problem Solving

- Creative Problem-Solving

- Leadership Styles and Problem Solving (focus on creativity)

- Forget About Causes, Focus on Solutions

- Ten Tips for Beefing Up Your Problem-Solving ToolBox

- Coaching Tip: Four-Question Method for Proactive Problem Solving

- Coaching Tip — How to Bust Paralysis by Analysis

- Appreciative Inquiry

- Powerful Problem-Solving

- Problem-Solving Techniques

- Guidelines for Selecting An Appropriate Problem-Solving Approach

- Factors to Consider in Figuring Out What to Do About A Problem

- A Case for Reengineering the Problem-Solving Process (Somewhat Advanced)

- Courseware on Problemistics (The art & craft of problem dealing)

- Adapt your leadership style

- Organic Approach to Problem Solving

- Make Good Decisions, Avoid Bad Consequences

- Priority Management: Are You Doing the Right Things?

General Guidelines for Decision Making

- Decision-Making Tips

- How We Sometimes Fool Ourselves When Making Decisions (Traps We Can Fall Into)

- More of the Most Common Decision-Making Mistakes (more traps we can fall into)

- When Your Organization’s Decisions Are in the Hands of Devils

- Flawed Decision-making is Dangerous

- Five Tips for Making Better Decisions

- Study Says People Make Better Decisions With a Full Bladder

- What Everyone Should Know About Decision Making

Various Tools and Methods for Problem Solving and Decision Making

(Many people would agree that the following methods and tools are also for decision-making.)

- Cost Benefit Analysis (for deciding based on costs)

- De Bono Hats (for looking at a situation from many perspectives

- Delphi Decision Making (to collect the views of experts and distill expert-based solutions)

- Dialectic Decision Making (rigorous action planning via examining opposite points of view) Fishbone Diagram —

- 5 Steps to build Fishbone Diagram

- Fishbowls (for groups to learn by watching modeled behaviors)

- Grid Analysis (for choosing among many choices)

- Pareto Principle (for finding the options that will make the most difference — (20/80 rule”)

- For solving seemingly unsolvable contradictions

- Rational Decision Making

- SWOT Analysis (to analyze strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats)

- Work Breakdown Structure (for organizing and relating many details)

General Resources for Problem Solving and Decision Making

- The Ultimate Problem-Solving Process Guide: 31 Steps and Resources

- list of various tools

- long list of tools

- Decision Making Tools

- Decision Making

- Group Decision Making and Problem Solving

- Inquiry and Reflection

- Mental Models (scan down to “Mental Models”)

- Questioning

- Research Methods

- Systems Thinking

Learn More in the Library’s Blogs Related to Problem Solving and Decision Making

In addition to the articles on this current page, also see the following blogs that have posts related to this topic. Scan down the blog’s page to see various posts. Also, see the section “Recent Blog Posts” in the sidebar of the blog or click on “Next” near the bottom of a post in the blog. The blog also links to numerous free related resources.

- Library’s Career Management Blog

- Library’s Coaching Blog

- Library’s Human Resources Blog

- Library’s Spirituality Blog

For the Category of Innovation:

To round out your knowledge of this Library topic, you may want to review some related topics, available from the link below. Each of the related topics includes free, online resources.

Also, scan the Recommended Books listed below. They have been selected for their relevance and highly practical nature.

- Recommended Books

Cost of Forming an LLC in Mississippi - 2024 Guide

Setting up an LLC in Mississippi involves more than filling out forms, it requires a grasp of the financial aspects to make smart choices. Though expenses might seem daunting, creating an LLC doesn’t need to break the bank. With tools like those from Tailor Brands, you can manage LLC costs effectively without skimping on quality. …

How Much It Cost to Form an LLC in New Jersey: 2024 Guide

Starting your own LLC in New Jersey involves a bit more than just the initial paperwork yet, it doesn’t need to break the bank. This piece will unravel the various costs you might bump into while forming an LLC in the Garden State. We’re also spotlighting services like Tailor Brands that streamline the process and …

What Does it Cost to Form a Rhode Island LLC in 2024?

Starting your own business in Rhode Island with an LLC involves serious thinking, not just about initial administrative duties but also about the financial repercussions. Even though the potential costs might seem intimidating at first glance, it’s crucial to understand that there are ways to cut these expenses smartly. Today’s discussion will tackle the costs …

Wisconsin LLC Cost Guide for 2024

Kickstarting an LLC in Wisconsin is a brilliant move for any budding entrepreneur, yet it’s crucial to grasp all associated costs beyond the initial filing fee. Though setting up a Limited Liability Company might appear pricey, it can actually be quite budget-friendly. In this guide, we’ll dissect the assorted expenses tied to launching an LLC …

Costs of Forming an LLC in Arkansas: 2024 Guide

Kicking off your LLC in Arkansas involves weighing various costs. These charges range from state filing fees, impacted by the LLC’s setup and how you submit your forms. You might also opt for extras like speedier processing or legal advice. Companies like Tailor Brands offer these services, adding to your final bill. Understanding these costs …

Cost of Forming an LLC in South Carolina – Updated for 2024

Starting your own Limited Liability Company (LLC) in South Carolina opens doors to new possibilities and independence. Still, worries about the costs might loom large. Launching an LLC goes beyond just submitting initial paperwork. However, the costs involved in forming your business can be more manageable than they first seem. We’ll dive into the cost …

Cost of Forming an LLC in Ohio - 2024 Guide

Starting an LLC in Ohio isn’t just about having a great idea. It’s also about knowing the financial hurdles ahead. Don’t let the thought of costs spook you! We’re diving into Ohio’s nitty-gritty of LLC expenses to help you stay savvy with your budget. Moreover, we’ll clue you in on tools like Tailor Brands, which …

What Is Tax Relief & How Does it Work?

Numerous individuals who pay taxes are seeking methods to lessen their tax obligations and take advantage of any feasible tax assistance. If eligible, one viable option for reducing their tax responsibility is to utilize tax relief initiatives. Tax relief programs, administered by the federal government and certain states, offer a variety of advantages, such as …

What Does it Cost to Form an LLC in Arizona?

Understanding the cost of forming an LLC in Arizona is essential for those interested in starting a business. People looking to set up a Limited Liability Company often ask, “how much does an LLC cost in Arizona?” or “What does the LLC cost in Arizona?” This exploration helps reveal elements that add to the total …

How to Start a Marketing Business in 2024

Are you dreaming of launching a marketing agency? With a whopping 428,744 advertising agencies around the globe, you’re not alone in this bustling arena! You may be a marketing pro eager to chart your course or an entrepreneur fired up about branding and strategy. Either way, starting a marketing agency offers excitement and lucrative potential. …

What Does LLC Formation Cost in Alabama?

Do you want to know the cost of forming an LLC in Alabama? There’s a financial side to the process besides just the paperwork. However, it’s more affordable than you might think. This article will guide you through the costs of setting up an LLC in Alabama. We’re excited to show you revolutionary LLC formation …

How Much Does an LLC Cost in California?

This guide details the “cost to form an LLC in California,” a state celebrated for its entrepreneurial opportunities. It covers the necessary and optional expenses required to set up an LLC. Knowing the financial requirements to start an LLC in California is vital for both new and experienced business owners. The guide also shows how …

What Is the Cost of Forming an LLC in Connecticut in 2024?

Welcome to Connecticut’s business scene, where setting up a Limited Liability Company (LLC) forms the foundation for your business activities. This process involves understanding the associated costs, which include filing fees and ongoing expenses. This article explains the “cost of forming an LLC in Connecticut.” For those seeking expert help, LLC services like Tailor Brands …

New York LLC Cost Guide for 2024

Stepping into New York’s entrepreneurial arena is a thrilling journey, yet being armed for various expenses linked with setting up an LLC in the Empire State is key. Forming your business involves more than just paperwork; it demands a keen eye on several financial elements. However, fret not over the potential costs. Armed with the …

How Much Does an LLC Cost in Oklahoma

Setting up an LLC in Oklahoma involves more than just basic paperwork. It’s a common myth that the process will drain your wallet. This guide will break down the actual costs of starting an LLC in Oklahoma and highlight savvy strategies to keep expenses low. Using services like Tailor Brands can smartly cut down on …

Privacy Overview

- INTERPERSONAL SKILLS

- Decision-Making and Problem Solving

Search SkillsYouNeed:

Interpersonal Skills:

- A - Z List of Interpersonal Skills

- Interpersonal Skills Self-Assessment

- Communication Skills

- Emotional Intelligence

- Conflict Resolution and Mediation Skills

- Customer Service Skills

- Team-Working, Groups and Meetings

Decision-Making and Problem-Solving

- Effective Decision Making

- Decision-Making Framework

- Introduction to Problem Solving

Identifying and Structuring Problems

Investigating Ideas and Solutions

Implementing a Solution and Feedback

- Creative Problem-Solving

Social Problem-Solving

- Negotiation and Persuasion Skills

- Personal and Romantic Relationship Skills

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

The SkillsYouNeed Guide to Interpersonal Skills

Making decisions and solving problems are two key areas in life, whether you are at home or at work. Whatever you’re doing, and wherever you are, you are faced with countless decisions and problems, both small and large, every day.

Many decisions and problems are so small that we may not even notice them. Even small decisions, however, can be overwhelming to some people. They may come to a halt as they consider their dilemma and try to decide what to do.

Small and Large Decisions

In your day-to-day life you're likely to encounter numerous 'small decisions', including, for example:

Tea or coffee?

What shall I have in my sandwich? Or should I have a salad instead today?

What shall I wear today?

Larger decisions may occur less frequently but may include:

Should we repaint the kitchen? If so, what colour?

Should we relocate?

Should I propose to my partner? Do I really want to spend the rest of my life with him/her?

These decisions, and others like them, may take considerable time and effort to make.

The relationship between decision-making and problem-solving is complex. Decision-making is perhaps best thought of as a key part of problem-solving: one part of the overall process.

Our approach at Skills You Need is to set out a framework to help guide you through the decision-making process. You won’t always need to use the whole framework, or even use it at all, but you may find it useful if you are a bit ‘stuck’ and need something to help you make a difficult decision.

Decision Making

Effective Decision-Making

This page provides information about ways of making a decision, including basing it on logic or emotion (‘gut feeling’). It also explains what can stop you making an effective decision, including too much or too little information, and not really caring about the outcome.

A Decision-Making Framework

This page sets out one possible framework for decision-making.

The framework described is quite extensive, and may seem quite formal. But it is also a helpful process to run through in a briefer form, for smaller problems, as it will help you to make sure that you really do have all the information that you need.

Problem Solving

Introduction to Problem-Solving

This page provides a general introduction to the idea of problem-solving. It explores the idea of goals (things that you want to achieve) and barriers (things that may prevent you from achieving your goals), and explains the problem-solving process at a broad level.

The first stage in solving any problem is to identify it, and then break it down into its component parts. Even the biggest, most intractable-seeming problems, can become much more manageable if they are broken down into smaller parts. This page provides some advice about techniques you can use to do so.

Sometimes, the possible options to address your problem are obvious. At other times, you may need to involve others, or think more laterally to find alternatives. This page explains some principles, and some tools and techniques to help you do so.

Having generated solutions, you need to decide which one to take, which is where decision-making meets problem-solving. But once decided, there is another step: to deliver on your decision, and then see if your chosen solution works. This page helps you through this process.

‘Social’ problems are those that we encounter in everyday life, including money trouble, problems with other people, health problems and crime. These problems, like any others, are best solved using a framework to identify the problem, work out the options for addressing it, and then deciding which option to use.

This page provides more information about the key skills needed for practical problem-solving in real life.

Further Reading from Skills You Need

The Skills You Need Guide to Interpersonal Skills eBooks.

Develop your interpersonal skills with our series of eBooks. Learn about and improve your communication skills, tackle conflict resolution, mediate in difficult situations, and develop your emotional intelligence.

Guiding you through the key skills needed in life

As always at Skills You Need, our approach to these key skills is to provide practical ways to manage the process, and to develop your skills.

Neither problem-solving nor decision-making is an intrinsically difficult process and we hope you will find our pages useful in developing your skills.

Start with: Decision Making Problem Solving

See also: Improving Communication Interpersonal Communication Skills Building Confidence

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

11 Myths About Decision-Making

- Cheryl Strauss Einhorn

And how to overcome them.

From “I like to be efficient” to “I trust my gut” to “I can make a rational decision,” there are a number of deeply ingrained — and counterproductive — myths we tell ourselves about how we make decisions. Underlying these myths are three common and popular ideas that don’t serve us well: First, as busy people, we don’t need to invest time to make good decisions. Second, we are rational human beings, able to thoughtfully solve thorny and high-stakes problems in our heads. Third, decision-making is personal and doesn’t need to involve anyone else. To combat these biases, the author recommends taking a calculated pause to step back and look at the bigger picture.

Can you imagine life without your smartphone?

- Cheryl Strauss Einhorn is the founder and CEO of Decisive, a decision sciences company using her AREA Method decision-making system for individuals, companies, and nonprofits looking to solve complex problems. Decisive offers digital tools and in-person training, workshops, coaching and consulting. Cheryl is a long-time educator teaching at Columbia Business School and Cornell and has won several journalism awards for her investigative news stories. She’s authored two books on complex problem solving, Problem Solved for personal and professional decisions, and Investing In Financial Research about business, financial, and investment decisions. Her new book, Problem Solver, is about the psychology of personal decision-making and Problem Solver Profiles. For more information please watch Cheryl’s TED talk and visit areamethod.com .

Partner Center

How to Apply Rational Thinking in Decision Making

I. introduction.

Have you ever thought about how you make decisions? Every day, in different situations, we need to make a series of decisions – from what to wear or what to eat for breakfast to more significant choices like career moves or financial investments. These decisions can have far-reaching effects on our personal and professional life. That’s why it’s important to approach decision-making in a purposeful and rational manner.

Let’s begin by understanding what rational thinking is: it’s a cognitive process that involves logical and objective reasoning. Basically, it’s a method used to logically process information and make a sensible judgement or decision. It’s about thinking clearly, sensibly, and logically, ensuring our actions are not guided by emotion, bias, or prejudice.

Decisions are an integral part of our lives. However, the quality of these decisions can vary greatly based on how we approach them. Irrational or impulsive decisions can lead to negative consequences or regret. Meanwhile, employing a rational thought process can lead to well-informed, balanced decisions that we can feel confident about.

Rationality is such a pivotal aspect of thoughtful decision-making, and harnessing it can truly be life-changing. In this blog post, we will understand the concept of rational thinking, its role in decision making, and how you can adopt it in your everyday life. By the conclusion of this article, we will also present you with tips to improve these critical thinking skills, and showcase real-life scenarios where rational thinking has proven successful. Let’s embark on this rational journey. It’s decision time!

II. Understanding Rational Thinking

Rational thinking, as the term implies, refers to a certain approach or method that involves the use of reason in processing information and formulating decisions. It encourages us to act based on facts, evidence, and logic rather than succumbing to emotional impulses or personal biases.

A. Detailed Definition of Rational Thinking

Rational thinking, in the broadest sense, is the cognitive process wherein the identification and evaluation of evidence guide an action or belief. Its synonyms include critical thinking, logical reasoning, or analytical thinking, and it is the cornerstone of problem-solving, innovation, and decision-making.

This form of thinking is characterized by deductive and inductive reasoning - where you draw general conclusions from specific observations or specific conclusions from general principles.

“In its essence, rational thinking is a systematic, disciplined process demanding keen intellect and an open mind” - Dr. Janeen DeMarte, Psychologist

B. Core Elements of Rational Thinking

So, what goes into rational thinking? Here are the three major elements that define the process:

1. Objectivity

One of the primary parts of rational thinking is maintaining objectivity. This means having an unbiased outlook and assessing situations based on facts rather than personal feelings or preconceived notions. It involves a scientific approach to thinking, where all available evidence is considered before making a judgment.

Logic is the bedrock of rational thinking. Every argument or conclusion that you make via rational thinking must logically follow from the premises. Anything that contradicts this principle is considered fallacious or invalid.

Lastly, honesty is integral to rational thinking. Often people manipulate facts to match their predetermined conclusion, but rational thinking necessitates an honest approach. It involves being truthful about the facts and accepting the conclusion that follows, no matter how it aligns with initial assumptions or desires.

C. Why Is Rational Thinking Important?

Rational thinking serves as our guiding light to navigate the complexities of the world around us. The more rational we are, the better we can understand reality, solve problems, and make informed decisions. It helps us step out of our emotional chaos and subjective bias, ensuring our decisions are grounded in reason and logic.

The importance of rational thinking is not confined to grandiose decisions, but also to our routine lives. From simply deciding your daily diet to complex decisions like career planning, rational thinking plays an essential role.

“Rational thinking helps us stay aligned with reality, improve the quality of our lives, and bring us closer to our objectives.”

V. Case Study: Successful Rational Decision Making in Real-life Scenarios

Let’s delve into some real-world instances where a rational approach led to successful decision-making outcomes. These case studies provide tangible insight into how rationality can have a profound impact on the decision-making process, and underscores the value of thinking rationally in our daily undertakings.

A. Steve Jobs and the Creation of the iPhone

One celebrated instance of rational decision-making is the creation of the revolutionary product – the iPhone. Steve Jobs, the late co-founder of Apple Inc., is renowned for his resolute decision to push for the iPhone’s development despite facing internal opposition.

Jobs identified the problem – the absence of a substantial mobile device merging a music player and a communication tool. He gathered relevant information about the technological landscape, the market, potential competitors, and customer needs.

Employing logic, he assessed this data objectively and determined that such a product stood a good chance of carving a niche in the market. His bold, rational decision gave birth to one of the world’s most sought-after pieces of technology.

B. Johnson & Johnson’s Tylenol Crisis Response

Another notable example comes from the pharmaceutical industry. In 1982, Johnson & Johnson faced a severe crisis when seven people in Chicago died after consuming its widely popular product, Tylenol, which had been laced with cyanide.

Regardless of the unknown culprit being an external actor, Johnson & Johnson embarked on a highly rational decision-making process. They first recognized the problem – a massive blow to their product’s credibility and potential loss of customer trust.

Information was gathered on the scale of the disaster and potential options to reinstate public confidence. Evincing remarkable honesty, the company opted to recall all Tylenol capsules, costing them over $100 million. This proved to be a rational decision in the long term, as it exemplified their enduring commitment to customer safety and restored their damaged reputation.

C. Elon Musk’s SpaceX Venture

Elon Musk, the founder of SpaceX, offers a more recent example. His decision to enter the space industry was a steep one, as space exploration had been dominated by national governmental organizations, like NASA.

The problem Musk identified was the lack of affordable methods to explore and travel in space. Gathering information about the industry, technological capacities, and prices, he realized with objectivity the huge challenge he faced. However, he saw a possibility where others did not.

SpaceX was established to create more affordable spacecraft and has since successfully launched many missions, proving that a private company can compete in this astoundingly complex field. This indicates that rational thinking and calculated risk-taking can pave the way for ground-breaking revolutions.

VI. Tips to Improve Rational Thinking Skill

Rational thinking isn’t an inborn skill that some are privileged to have and others not. Rather, it’s a learnable skill that can be honed and developed with time, effort, consistency and patience. Here are some methods you can use to elevate your rational thinking:

A. Self-awareness

Cultivating self-awareness is the first step to improving your rational thinking skill. This involves being mindful of your thoughts, feelings, actions, and biases. Question your beliefs and conclusions, and try to understand both the emotion and rationality behind your thoughts.

“> Cultivating self-awareness is like pulling the curtain back on your internal drama, revealing the characters in play and understanding their motivations.”

Being aware of your cognitive biases can also enhance your rational thinking. Cognitive biases are thinking errors we make that can affect our decisions and judgments. For instance, the confirmation bias can block us from accepting new information. By recognizing these biases, we can counteract them and think more rationally.

B. Constant Learning

Rational thinking isn’t a static skill. Instead, it constantly needs fuel in the form of knowledge to grow stronger. Surround yourself with diverse knowledge sources such as books, podcasts, articles, seminars, conversations with people from different walks of life and industry experts. The more information you gather, the more well-rounded your understanding of the world will be, allowing for more sound judgments.

“> Lifelong learning is a limitless source of fuel for rational thoughts. It broadens your experiences and perspectives and helps you make decisions from an informed viewpoint.”

C. Cultivating Patience

Rational thinking requires patience. Quick decisions often lead to irrational outcomes. When you have more patience, you are much more likely to gather all the relevant information and think the situation over before coming to a decision. Be patient, take the time to think, and do not be swayed by the impulsiveness that often accompanies decision-making.

“> Patience is more than simply waiting. It’s the ability to keep a good attitude while working hard, focusing on your goal and trusting in the process.”

Remember, rational thinking is a journey, not a destination, and growth often takes effort to realize. But with consistency, self-awareness, patience, and the desire to learn, you can substantially improve your rational thinking skills and make more informed and logical decisions in your day-to-day life.

VII. Conclusion

In conclusion, it’s clear that rational thinking is a highly beneficial tool when it comes to decision making. Logic, honesty and objectivity are the key elements that enable us to make rational decisions.

“Rational thinking is not just about making decisions that benefit us in the short term, it’s about making decisions that will continue to benefit us in the long run.”

If we let our situations, emotions or biases determine our decisions, we may face unfavorable outcomes. Hence, exercising rationality helps us avoid the negative consequences of irrationality.

Rational thinking doesn’t only enable us to make well thought-out decisions, it also allows us to understand why we make certain decisions. We learnt about a simple step-by-step guide which can be integrated into our everyday life, helping us approach even the most complex problems rationally.

Remember the stories of successful rational decision making we shared? They provide real-life examples of how beneficial rational thinking can be. These people were able to achieve great things by thinking rationally and you can too!

Furthermore, we should always strive to improve our rational thinking skills. This can be achieved by promoting self-awareness, practicing patience, and dedicating ourselves to constant learning.

All in all, it’s important to realize that our decisions shape our lives. Consequently, the way we approach our decisions plays a big role in determining our successes and failures. By incorporating rational thinking into our decision making, we can ensure that we’re making the best possible decisions that will lead us towards our desired outcomes.

To paraphrase a famous quote,

“Every decision we make, and every step we take, is a result of our thinking. Therefore, if we want to change our lives, we must first change our thinking.”

Let’s strive to apply rational thinking in our everyday decision making and see the powerful positive impact it can have on our lives!

VIII. Call to Action

In conclusion, rational thinking plays a crucial role in making sound decisions personally or professionally.

“The key to good decision making is evaluating alternatives carefully and thoroughly. This calls for us to utilize our cognitive abilities rationally.”

Taking the time to analyze situations objectively, consider all feasible options, and logically draw conclusions will greatly improve our decision-making abilities.

Implement Rational Thinking

Now that you have a better understanding of rational thinking’s importance in decision-making, it is time to evaluate your own decision-making processes. Start by identifying opportunities in your daily life where you can apply rational thinking. You may be surprised at how often you encounter decision-making scenarios. From determining what to have for breakfast, choosing the route for your daily commute to making important business decisions, rational thinking can be applied intelligibly.

Continuous Improvement

Enriching rational thinking skills isn’t a process that happens overnight. It requires sustained effort and continuous learning.

- Try to maintain a continuous self-awareness of your decision-making processes.

- Aim to always gather relevant information before making decisions.

- Strive to interpret the given information objectively without any personal bias.

- Ensure to consider all possible options and outcomes before coming to a conclusion.

In addition, developing patience is equally critical as rushing through decisions can lead to errors in judgment.

“Genius might be the ability to say a profound thing in a simple way.” ~ Charles Bukowski

The beauty of rational thinking lies in its simplicity. It’s about being grounded in reality, and making decisions logically.

Further Resources

While this post provides a good starting point, there’s much more to explore when it comes to rational thinking and decision making. Books, online courses, and workshops can provide in-depth information and practical exercises to help you further improve your rational thinking skills. Search for resources that best suit your learning style, and make a commitment to continuous growth.

Remember, every decision we make shapes our life. Thus, each decision, no matter how small, should be made after thorough rational consideration. Adopt rational thinking today and make it an integral part of your daily life. Your future self will thank you!

Unlock Your Purpose Through Passion

Effective negotiation strategies, 3 steps to improved rational thinking, 5 surprising statistics about rational thinking, 10 irrational thoughts we must eliminate, why do we often lack rational thinking.

Rational Decision-Making Model: Meaning, Importance And Examples

What is the rational decision-making model? Rational decision-making is a method that organizations, businesses and individuals use to make the…

What is the rational decision-making model? Rational decision-making is a method that organizations, businesses and individuals use to make the best decisions. Rational decision-making, one of many decision-making tools, helps users come up with the most suitable course of action. In this blog, we will look at the meaning of rational decision-making, the importance of rational decision-making and study some rational decision-making examples.

Rational decision-making is a process in which decision-makers go through a set of steps and processes and choose the best solution to a problem. These decisions are based on data analysis and logic, eliminating intuition and subjectivity.

Rational decision-making means that every variable factor, every piece of information about all the available options, has been taken into account.

What Is The Rational Decision-Making Model Used For?

What is the rational decision-making process, non-rational decision making.

The most basic use of the rational decision-making model is to ensure a consistent method of making decisions. This could be used as a standardized decision-making tool across an organization or to ensure that all managers receive the same information to make decisions. The rational decision-making process can be used to maintain a structured, step-by-step approach for every decision.

What Is The Rational Decision-Making Process ?

How the rational decision-making model is implemented can be explained in seven steps:

(There is also an example to help you understand the importance of rational decision-making)

1. Understand and define the scope

Just stating that a problem exists isn’t enough. Solid, accurate data is required to understand and analyze the problem in depth. This lets you know how much attention it requires.

It’s vital to collect as much relevant and accurate data around the problem as possible.

Here’s a rational decision-making example:

Your social media posts aren’t translating to conversions. What could the problem be? Once the analytics reports come in, you realize there isn’t enough engagement. The issue isn’t that your posts are not reaching the right audience, it’s that they don’t engage them. This sets up the next step: figuring out why the problem exists. Why is user engagement low?

2. Research and get feedback

The next step in the rational decision-making process is to delve into the problem. Find out what is causing the problem and how it can be solved. You could start with a brainstorming session and find out what your team thinks.

Rational decision-making example continued:

The budget is good, there are enough views and likes on the posts. So, why is there a lack of engagement? Why aren’t users interacting with the post? Why aren’t they clicking on the CTA?

You might need new types of posts; perhaps the current posts aren’t trendy. Maybe the posts don’t evoke an emotional response from the audience. Or they don’t convey what the product can do for the audience.

Now that you know what the causes could be, you are a step closer. It’s time to collate the data.

The team comes together with their opinions and findings. After a few customer surveys, the major issues are identified as follows:

- Potential consumers don’t know how the product will add value to their lives.

- Potential customers don’t understand the posts’ objectives and aren’t clear on what the product is.

3. List your choices

There are bound to be a host of opinions and innumerable choices about how to address the issue. Consider all of them so that you don’t create more problems later.

This is where you start to use rational decision-making:

Now that the problem has been understood, it’s time to list your options.

You could create a post that showcases what the product does.

You could have an informative GIF that shows that product in action.

You could create additional whitepapers to showcase how the product adds value and thus is beneficial for the customer to buy.