- Advanced search

- Peer review

Why ‘context’ is important for research

Context is something we’ve been thinking a lot about at ScienceOpen recently. It comes from the Latin ‘ con ’ and ‘ texere ’ (to form ‘ contextus ’), which means ‘weave together’. The implications for science are fairly obvious: modern research is about weaving together different strands of information, thought, and data to place your results into the context of existing research. This is the reason why we have introductory and discussion sections at the intra-article level.

But what about context at a higher level?

Context can defined as: “ The circumstances that form the setting for an event, statement, or idea, and in terms of which it can be fully understood .” Simple follow on questions might be then, what is the context of a research article? How do we define that context? How do we build on that to do science more efficiently? The whole point for the existence of research articles is that they can be understood by as broad an audience as possible so that their re-use is maximised.

There are many things that impinge upon the context of research. Paywalls, secretive and exclusive peer review, lack of discovery, lack of inter-operability, lack of accessibility. The list is practically endless, and a general by-product of a failure for traditional scholarly publishing models to embrace a Web-based era.

While a lot of excellent new research platforms now feature slick discovery tools and features, we feel that this falls short of what is really needed for optimal research re-use in the digital age.

Discovery is the pathway to context. Context of an article is all about how research fits into increasingly complex domains, and using structured networks to decipher its value. With the power of the internet at our disposal, putting research in context should be of key importance in a world where there is ever more research being published that is impossible to manually filter.

Tracking the genealogy of research

Citations are perhaps what we might consider to be academic context. These form the structured networks or genealogies of an idea in their rawest sense. Through citations we gain a small amount of understanding into how research is being re-used by other researchers, and also the gateway to understanding what it is those citations are telling us.

At ScienceOpen, we show all articles and article records that cite a particular research article, and also provide links to similar articles on our platform. These are drawn at the moment from almost 12 million article records, so can potentially form huge networks of information.

In addition we show which articles are most similar based on keywords, and also which open access articles are citing a particular work. You can explore each of these in more depth, and begin to track research networks! So it’s like enhanced discovery, but with a smattering of cherries on top.

Generating context through engagement

One of the great things about context is that it is flexible and can be defined by user engagement. Take peer review for example. This is a way of adding context to a paper, by drawing on external expertise and perspective to enhance the content of a research article. Peer evaluation of this sort is crucial for defining the context of a paper, and should not be hidden away out of sight and use. As we use public post-publication peer review at ScienceOpen, the full discussion and process of research is transparent.

Other ways of generating simple context are through sharing and recommendations of articles. The more this is done, the more you can understand which articles are of wider interest.

Social context

The rise of altmetrics can be seen as the broadening how we think about context. Altmetrics are a pathway to understanding how articles have been discussed, mentioned or shared in online sources including mainstream news outlets, blogs, and a variety of social networks.

On every single article record (almost 12 million at the moment), we show Altmetric scores. You can also sort searches by Altmetric, which provides additional context for which articles are generating the most societal discussion online. This is great if you want to track social media trends in a particular field, and again is all about placing research objects into a broader context.

So these are just some of the ways in which we put research in context, and we do it on a massive scale. Let us know in the comments what you think ‘research in context’ is all about, and why you think it’s important!

2 thoughts on “Why ‘context’ is important for research”

- Pingback: Welcome to the Italian Society of Victimology – ScienceOpen Blog

- Pingback: ScienceOpen smashes through the 20 million article record mark – ScienceOpen Blog

Comments are closed.

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How to Write an Effective Background of the Study: A Comprehensive Guide

Table of Contents

The background of the study in a research paper offers a clear context, highlighting why the research is essential and the problem it aims to address.

As a researcher, this foundational section is essential for you to chart the course of your study, Moreover, it allows readers to understand the importance and path of your research.

Whether in academic communities or to the general public, a well-articulated background aids in communicating the essence of the research effectively.

While it may seem straightforward, crafting an effective background requires a blend of clarity, precision, and relevance. Therefore, this article aims to be your guide, offering insights into:

- Understanding the concept of the background of the study.

- Learning how to craft a compelling background effectively.

- Identifying and sidestepping common pitfalls in writing the background.

- Exploring practical examples that bring the theory to life.

- Enhancing both your writing and reading of academic papers.

Keeping these compelling insights in mind, let's delve deeper into the details of the empirical background of the study, exploring its definition, distinctions, and the art of writing it effectively.

What is the background of the study?

The background of the study is placed at the beginning of a research paper. It provides the context, circumstances, and history that led to the research problem or topic being explored.

It offers readers a snapshot of the existing knowledge on the topic and the reasons that spurred your current research.

When crafting the background of your study, consider the following questions.

- What's the context of your research?

- Which previous research will you refer to?

- Are there any knowledge gaps in the existing relevant literature?

- How will you justify the need for your current research?

- Have you concisely presented the research question or problem?

In a typical research paper structure, after presenting the background, the introduction section follows. The introduction delves deeper into the specific objectives of the research and often outlines the structure or main points that the paper will cover.

Together, they create a cohesive starting point, ensuring readers are well-equipped to understand the subsequent sections of the research paper.

While the background of the study and the introduction section of the research manuscript may seem similar and sometimes even overlap, each serves a unique purpose in the research narrative.

Difference between background and introduction

A well-written background of the study and introduction are preliminary sections of a research paper and serve distinct purposes.

Here’s a detailed tabular comparison between the two of them.

Aspect | Background | Introduction |

Primary purpose | Provides context and logical reasons for the research, explaining why the study is necessary. | Entails the broader scope of the research, hinting at its objectives and significance. |

Depth of information | It delves into the existing literature, highlighting gaps or unresolved questions that the research aims to address. | It offers a general overview, touching upon the research topic without going into extensive detail. |

Content focus | The focus is on historical context, previous studies, and the evolution of the research topic. | The focus is on the broader research field, potential implications, and a preview of the research structure. |

Position in a research paper | Typically comes at the very beginning, setting the stage for the research. | Follows the background, leading readers into the main body of the research. |

Tone | Analytical, detailing the topic and its significance. | General and anticipatory, preparing readers for the depth and direction of the focus of the study. |

What is the relevance of the background of the study?

It is necessary for you to provide your readers with the background of your research. Without this, readers may grapple with questions such as: Why was this specific research topic chosen? What led to this decision? Why is this study relevant? Is it worth their time?

Such uncertainties can deter them from fully engaging with your study, leading to the rejection of your research paper. Additionally, this can diminish its impact in the academic community, and reduce its potential for real-world application or policy influence .

To address these concerns and offer clarity, the background section plays a pivotal role in research papers.

The background of the study in research is important as it:

- Provides context: It offers readers a clear picture of the existing knowledge, helping them understand where the current research fits in.

- Highlights relevance: By detailing the reasons for the research, it underscores the study's significance and its potential impact.

- Guides the narrative: The background shapes the narrative flow of the paper, ensuring a logical progression from what's known to what the research aims to uncover.

- Enhances engagement: A well-crafted background piques the reader's interest, encouraging them to delve deeper into the research paper.

- Aids in comprehension: By setting the scenario, it aids readers in better grasping the research objectives, methodologies, and findings.

How to write the background of the study in a research paper?

The journey of presenting a compelling argument begins with the background study. This section holds the power to either captivate or lose the reader's interest.

An effectively written background not only provides context but also sets the tone for the entire research paper. It's the bridge that connects a broad topic to a specific research question, guiding readers through the logic behind the study.

But how does one craft a background of the study that resonates, informs, and engages?

Here, we’ll discuss how to write an impactful background study, ensuring your research stands out and captures the attention it deserves.

Identify the research problem

The first step is to start pinpointing the specific issue or gap you're addressing. This should be a significant and relevant problem in your field.

A well-defined problem is specific, relevant, and significant to your field. It should resonate with both experts and readers.

Here’s more on how to write an effective research problem .

Provide context

Here, you need to provide a broader perspective, illustrating how your research aligns with or contributes to the overarching context or the wider field of study. A comprehensive context is grounded in facts, offers multiple perspectives, and is relatable.

In addition to stating facts, you should weave a story that connects key concepts from the past, present, and potential future research. For instance, consider the following approach.

- Offer a brief history of the topic, highlighting major milestones or turning points that have shaped the current landscape.

- Discuss contemporary developments or current trends that provide relevant information to your research problem. This could include technological advancements, policy changes, or shifts in societal attitudes.

- Highlight the views of different stakeholders. For a topic like sustainable agriculture, this could mean discussing the perspectives of farmers, environmentalists, policymakers, and consumers.

- If relevant, compare and contrast global trends with local conditions and circumstances. This can offer readers a more holistic understanding of the topic.

Literature review

For this step, you’ll deep dive into the existing literature on the same topic. It's where you explore what scholars, researchers, and experts have already discovered or discussed about your topic.

Conducting a thorough literature review isn't just a recap of past works. To elevate its efficacy, it's essential to analyze the methods, outcomes, and intricacies of prior research work, demonstrating a thorough engagement with the existing body of knowledge.

- Instead of merely listing past research study, delve into their methodologies, findings, and limitations. Highlight groundbreaking studies and those that had contrasting results.

- Try to identify patterns. Look for recurring themes or trends in the literature. Are there common conclusions or contentious points?

- The next step would be to connect the dots. Show how different pieces of research relate to each other. This can help in understanding the evolution of thought on the topic.

By showcasing what's already known, you can better highlight the background of the study in research.

Highlight the research gap

This step involves identifying the unexplored areas or unanswered questions in the existing literature. Your research seeks to address these gaps, providing new insights or answers.

A clear research gap shows you've thoroughly engaged with existing literature and found an area that needs further exploration.

How can you efficiently highlight the research gap?

- Find the overlooked areas. Point out topics or angles that haven't been adequately addressed.

- Highlight questions that have emerged due to recent developments or changing circumstances.

- Identify areas where insights from other fields might be beneficial but haven't been explored yet.

State your objectives

Here, it’s all about laying out your game plan — What do you hope to achieve with your research? You need to mention a clear objective that’s specific, actionable, and directly tied to the research gap.

How to state your objectives?

- List the primary questions guiding your research.

- If applicable, state any hypotheses or predictions you aim to test.

- Specify what you hope to achieve, whether it's new insights, solutions, or methodologies.

Discuss the significance

This step describes your 'why'. Why is your research important? What broader implications does it have?

The significance of “why” should be both theoretical (adding to the existing literature) and practical (having real-world implications).

How do we effectively discuss the significance?

- Discuss how your research adds to the existing body of knowledge.

- Highlight how your findings could be applied in real-world scenarios, from policy changes to on-ground practices.

- Point out how your research could pave the way for further studies or open up new areas of exploration.

Summarize your points

A concise summary acts as a bridge, smoothly transitioning readers from the background to the main body of the paper. This step is a brief recap, ensuring that readers have grasped the foundational concepts.

How to summarize your study?

- Revisit the key points discussed, from the research problem to its significance.

- Prepare the reader for the subsequent sections, ensuring they understand the research's direction.

Include examples for better understanding

Research and come up with real-world or hypothetical examples to clarify complex concepts or to illustrate the practical applications of your research. Relevant examples make abstract ideas tangible, aiding comprehension.

How to include an effective example of the background of the study?

- Use past events or scenarios to explain concepts.

- Craft potential scenarios to demonstrate the implications of your findings.

- Use comparisons to simplify complex ideas, making them more relatable.

Crafting a compelling background of the study in research is about striking the right balance between providing essential context, showcasing your comprehensive understanding of the existing literature, and highlighting the unique value of your research .

While writing the background of the study, keep your readers at the forefront of your mind. Every piece of information, every example, and every objective should be geared toward helping them understand and appreciate your research.

How to avoid mistakes in the background of the study in research?

To write a well-crafted background of the study, you should be aware of the following potential research pitfalls .

- Stay away from ambiguity. Always assume that your reader might not be familiar with intricate details about your topic.

- Avoid discussing unrelated themes. Stick to what's directly relevant to your research problem.

- Ensure your background is well-organized. Information should flow logically, making it easy for readers to follow.

- While it's vital to provide context, avoid overwhelming the reader with excessive details that might not be directly relevant to your research problem.

- Ensure you've covered the most significant and relevant studies i` n your field. Overlooking key pieces of literature can make your background seem incomplete.

- Aim for a balanced presentation of facts, and avoid showing overt bias or presenting only one side of an argument.

- While academic paper often involves specialized terms, ensure they're adequately explained or use simpler alternatives when possible.

- Every claim or piece of information taken from existing literature should be appropriately cited. Failing to do so can lead to issues of plagiarism.

- Avoid making the background too lengthy. While thoroughness is appreciated, it should not come at the expense of losing the reader's interest. Maybe prefer to keep it to one-two paragraphs long.

- Especially in rapidly evolving fields, it's crucial to ensure that your literature review section is up-to-date and includes the latest research.

Example of an effective background of the study

Let's consider a topic: "The Impact of Online Learning on Student Performance." The ideal background of the study section for this topic would be as follows.

In the last decade, the rise of the internet has revolutionized many sectors, including education. Online learning platforms, once a supplementary educational tool, have now become a primary mode of instruction for many institutions worldwide. With the recent global events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a rapid shift from traditional classroom learning to online modes, making it imperative to understand its effects on student performance.

Previous studies have explored various facets of online learning, from its accessibility to its flexibility. However, there is a growing need to assess its direct impact on student outcomes. While some educators advocate for its benefits, citing the convenience and vast resources available, others express concerns about potential drawbacks, such as reduced student engagement and the challenges of self-discipline.

This research aims to delve deeper into this debate, evaluating the true impact of online learning on student performance.

Why is this example considered as an effective background section of a research paper?

This background section example effectively sets the context by highlighting the rise of online learning and its increased relevance due to recent global events. It references prior research on the topic, indicating a foundation built on existing knowledge.

By presenting both the potential advantages and concerns of online learning, it establishes a balanced view, leading to the clear purpose of the study: to evaluate the true impact of online learning on student performance.

As we've explored, writing an effective background of the study in research requires clarity, precision, and a keen understanding of both the broader landscape and the specific details of your topic.

From identifying the research problem, providing context, reviewing existing literature to highlighting research gaps and stating objectives, each step is pivotal in shaping the narrative of your research. And while there are best practices to follow, it's equally crucial to be aware of the pitfalls to avoid.

Remember, writing or refining the background of your study is essential to engage your readers, familiarize them with the research context, and set the ground for the insights your research project will unveil.

Drawing from all the important details, insights and guidance shared, you're now in a strong position to craft a background of the study that not only informs but also engages and resonates with your readers.

Now that you've a clear understanding of what the background of the study aims to achieve, the natural progression is to delve into the next crucial component — write an effective introduction section of a research paper. Read here .

Frequently Asked Questions

The background of the study should include a clear context for the research, references to relevant previous studies, identification of knowledge gaps, justification for the current research, a concise overview of the research problem or question, and an indication of the study's significance or potential impact.

The background of the study is written to provide readers with a clear understanding of the context, significance, and rationale behind the research. It offers a snapshot of existing knowledge on the topic, highlights the relevance of the study, and sets the stage for the research questions and objectives. It ensures that readers can grasp the importance of the research and its place within the broader field of study.

The background of the study is a section in a research paper that provides context, circumstances, and history leading to the research problem or topic being explored. It presents existing knowledge on the topic and outlines the reasons that spurred the current research, helping readers understand the research's foundation and its significance in the broader academic landscape.

The number of paragraphs in the background of the study can vary based on the complexity of the topic and the depth of the context required. Typically, it might range from 3 to 5 paragraphs, but in more detailed or complex research papers, it could be longer. The key is to ensure that all relevant information is presented clearly and concisely, without unnecessary repetition.

You might also like

Boosting Citations: A Comparative Analysis of Graphical Abstract vs. Video Abstract

The Impact of Visual Abstracts on Boosting Citations

Introducing SciSpace’s Citation Booster To Increase Research Visibility

- Why QR Works

- When to Use QR

- Types of QR

- Types of QR Careers

- Maximize Your Experience

- What is QRCA

- Star Volunteer Program

- Advance Program

- Thought Leaders

- QualPower Blog

- Young Professionals Central

- Inclusive Culture Committee

- VIEWS Magazine

- QRCA Merchandise

- Industry Partners

- Press Releases

- 2025 Annual Conference

- Worldwide Conference

- Past Conferences

- Board of Directors

- Past Presidents

- Get Involved

- Strategic Plan

- Membership Options

- Reasons to Join

- Annual Conference

- Advertising Opportunities

- Visit QualBook Directory

- Find a Qualitative Professional

- Find a Support Partner

- VIEWS Podcasts

- Qcast Webinars

- QualBook Directory

- Post a Career Opening

- Qualology Learning Hub

- Core Competencies

- Resource Library

- Member Forum

- New Member Benefits Overview

- Health Care Program

- Connections News

- Annual Reports

- Calendar of Events

- Qualitative Fundamentals Program

- International Market Research Day

- Ycast Webinars

- SIG Meetings

- Chapter Meetings

- My QRCA Advance

- My Member Pages

| Name: | |

| Category: | |

| Share: | |

| Qual Power |

| Posted By , Tuesday, May 3, 2022 |

|

In qualitative research, we study how people make decisions, why they behave the way they do, and what they think about various products or services. And the most authentic way to study how people come to these opinions or behave the way they do is by putting people in Human beings are triggered—subconsciously—by settings, stimuli, and often, others’ opinions. Yet in qual, we’re prone to think that it’s our “methodologically sound” questions that will give us answers, regardless of whether we’re interviewing over Zoom, in a focus group at a facility, or in an office workspace. But that’s simply not true; to truly take insights to a higher level, it’s critical to keep the context of how decisions are made. Let’s explore this more by looking at how to think about context before setting up a study. This sounds obvious, yet so many researchers miss this when they think about methodology design. The first question to ask yourself when thinking about methodology is simply this:

For example, if someone is shopping online for clothes, and you’re testing the user interface, then the obvious study design will be a one-on-one interview, where you can see the person navigate through the app/website. This is an individual decision. However, what if instead the study was about fashion trends—and not the shopping interface? Next, you have to ask yourself: Is the target audience one that may look at fashion with friends, discuss what’s stylish, and make decisions that are influenced by others? If the answer to this question is yes, then consider a focus group or co-creation study to understand how a cohort discusses and judges fashion options. The interplay among the participants (assuming you have a well-defined persona group) will give you far richer insights than had you done a one-on-one interview. This key question, applies equally to business contexts. If this is the study’s purpose, therefore (to understand the viability of a new software product for a team), I’m going to propose a group methodology study. This may involve an affinity group (or snowball sample) of a whole team, where I interview them about the product and see how they discuss and make the decision, , or I’ll interview like-titles and industry participants to see how they debate and analyze the software product. This mimics how decisions are made in the workplace, and the insights are far richer than IDIs will produce. The second question to ask yourself, after the methodology is decided, is will you collect the data? Or, in other words: What’s the appropriate setting context for this type of research? Let’s say you’re talking to millennials who work in tech about burnout on the job. Sure, you could take them to a facility, but for this cohort, they might feel more relaxed in a hip co-working space. For studies like this, I’ll interview them in a WeWork conference room. Another example: Let’s say you’re talking to HR executives about health care software platforms. In this case, a focus group facility would be my choice: The formality and more corporate setting will lend itself to a discussion where I can help participants feel more comfortable about the topic.

And finally, what about a study where you’re studying passenger stress when flying on airplanes? Is interviewing them one-on-one via Zoom really going to capture how they felt when they were fifth in the lineup for boarding? No, it won’t. So in a study like this, I would propose having them record their experiences—as they’re flying—on a mobile ethnography app. I’d then debrief after in an IDI. In this way, I’m able to observe them contextually, and then fill in later with more specific probes about their experiences. And You’ll find that your research will be more creative, fruitful, and more accurately capture true opinions, behaviors, and decisions. Joanna Jones and Karen Seratti are the co-founders of and Joanna is the founder of . At InterQ Learning Labs, the instructors teach research contextually—meaning the participants are taken to various research spaces, and they learn how to set up studies based on the research goals and outputs. InterQ Learning Labs classes are held in premier cities around the U.S. in 2- and 4-day immersive settings. InterQ is based in the San Francisco Bay Area.

| Comments (0) |

6/27/2024 International Chapter: Global Researcher Webinar Series

7/10/2024 PNW Chapter: Alt, Shift, Ctrl & Undo: 4 Keystrokes Required to Engage With Gen Z

7/12/2024 Southern CA Chapter: From Zero to Done: Report Writing with Speed, Fun, and 100% Confidence

QRCA 1601 Utica Ave S, Suite 213 Minneapolis, MN 55416

phone: 651. 290. 7491 fax: 651. 290. 2266 [email protected]

Please share your ideas or concerns with QRCA leaders at [email protected].

Privacy Policy | Email Deliverability | Site Map | Sign Out © 2024 QRCA

- Become a QRCA Member

- Learning and Events

- My Member Resources

- Diversity, Equity and Inclusion

- Subscribe to QRCA Email

- Find a Member

This website is optimized for Firefox and Chrome. If you have difficulties using this site, see complete browser details .

Request info

Report reader checklist : context.

Information about the context of a study is usually included at the beginning and end of a report. At the beginning of a report, this context should be provided to describe past research and theory and then explain the focus of the study. At the end of a report, a contextual discussion can relate the findings of the study back to past research and suggest next steps to further understand the topic. When context is missing from a report, you may not understand how the study relates to or informs a general understanding of the topic. For example, you might not have a clear understanding of the background on the topic, how the study advances knowledge on the topic and how the results of the study can be applied. The following are important things to identify as you look for context in research reports:

The report provides a background on the topic, including relevant definitions, the context within which the study is conducted and a rationale for why the study was conducted.

It is important for you to understand why the study was conducted, what the study attempted to accomplish, why the research is important to the field and how the results could be used.

It is also important for you to know how this study fits into the larger body of research that has been conducted on this topic. If the study is the first study of its kind, that should be mentioned. Otherwise, look to see if the authors include references to studies previously published on the topic. This helps you understand how the study adds to or clarifies understanding of the topic. [ see examples ] b. The report explains the history of the study and/or theoretical frameworks, if appropriate.

Some studies in the field of online teaching and learning are repeated periodically. When this is the case, a report should include information, such as past participant rates, revisions to survey instruments or research protocols, or other changes to the study methodology since the previous findings were released.

Study reports may also include theoretical frameworks . Theories (or theoretical frameworks) associate a study with other studies done on a topic. These studies combined together (often called a body of research) can increase overall understanding of a topic and help you see where a study falls within a line of research. You should be able to understand the basic theoretical framework of a report without prior knowledge. If the study is based in theory, the theory can be described and it should be clear how the theory relates to the main focus of the study. [ see examples ] c. The report includes the research aims or goals addressed by the study.

Research aims or goals are often included toward the beginning of the report after past research and theoretical frameworks have been explained. Research aims or goals (sometimes framed as questions) should be clearly identified in a report and can be written in a way that helps you understand what the study is investigating.

[ see examples ] d. The report offers suggestions for further research.

a. The report describes the larger purpose or need for the study.

- See pages 11-14 for an example of a summary of previous research and clear definitions.

- See page 3 for a description of this study’s purpose with citations.

b. The report explains the history of the study and/or theoretical frameworks, if appropriate.

- Pages 5-7 highlight key findings as compared to previous year’s reports. Page 6 features major themes over 12 years of conducting this report.

c. The report includes the research aims or goals addressed by the study.

- Page 3 features a preface that provides key details about the history of the report and the need for the twelfth edition.

d. The report offers suggestions for further research.

- See pages 9-10 for several recommendations for future research. These recommendations are provided in a way that is digestible for diverse readers.

Checklist areas

Download a one-page version of the checklist .

What are theoretical frameworks?

What are qualitative research methodologies, what are quantitative research methodologies, what are mixed methodologies, what is validity, what is the difference between a population and a sample, what is generalizability in research, what is data visualization, what is conflict of interest, contact info.

Providing access to quality education with 110+ online degree programs

Oregon State Ecampus 4943 The Valley Library 201 SW Waldo Place Corvallis, OR 97331 800-667-1465 | 541-737-9204

Land Acknowledgment

Quick Navigation

Contact Us Ask Ecampus Join Our Team Online Giving Authorization and Compliance Site Map

Our Division

Division of educational ventures.

About the Division About Ecampus Degrees and Programs Online Ecampus Research Unit Open Educational Resources Unit Corporate and Workforce Education Unit Center for the Outdoor Recreation Economy Staff Directory

Social Media and Canvas

Copyright 2024 Oregon State University Privacy Information and Disclaimer

For Faculty

W3C Validation: HTML5 + CSS3 + WAVE

- Privacy Policy

Home » Background of The Study – Examples and Writing Guide

Background of The Study – Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Background of The Study

Definition:

Background of the study refers to the context, circumstances, and history that led to the research problem or topic being studied. It provides the reader with a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter and the significance of the study.

The background of the study usually includes a discussion of the relevant literature, the gap in knowledge or understanding, and the research questions or hypotheses to be addressed. It also highlights the importance of the research topic and its potential contributions to the field. A well-written background of the study sets the stage for the research and helps the reader to appreciate the need for the study and its potential significance.

How to Write Background of The Study

Here are some steps to help you write the background of the study:

Identify the Research Problem

Start by identifying the research problem you are trying to address. This problem should be significant and relevant to your field of study.

Provide Context

Once you have identified the research problem, provide some context. This could include the historical, social, or political context of the problem.

Review Literature

Conduct a thorough review of the existing literature on the topic. This will help you understand what has been studied and what gaps exist in the current research.

Identify Research Gap

Based on your literature review, identify the gap in knowledge or understanding that your research aims to address. This gap will be the focus of your research question or hypothesis.

State Objectives

Clearly state the objectives of your research . These should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART).

Discuss Significance

Explain the significance of your research. This could include its potential impact on theory , practice, policy, or society.

Finally, summarize the key points of the background of the study. This will help the reader understand the research problem, its context, and its significance.

How to Write Background of The Study in Proposal

The background of the study is an essential part of any proposal as it sets the stage for the research project and provides the context and justification for why the research is needed. Here are the steps to write a compelling background of the study in your proposal:

- Identify the problem: Clearly state the research problem or gap in the current knowledge that you intend to address through your research.

- Provide context: Provide a brief overview of the research area and highlight its significance in the field.

- Review literature: Summarize the relevant literature related to the research problem and provide a critical evaluation of the current state of knowledge.

- Identify gaps : Identify the gaps or limitations in the existing literature and explain how your research will contribute to filling these gaps.

- Justify the study : Explain why your research is important and what practical or theoretical contributions it can make to the field.

- Highlight objectives: Clearly state the objectives of the study and how they relate to the research problem.

- Discuss methodology: Provide an overview of the methodology you will use to collect and analyze data, and explain why it is appropriate for the research problem.

- Conclude : Summarize the key points of the background of the study and explain how they support your research proposal.

How to Write Background of The Study In Thesis

The background of the study is a critical component of a thesis as it provides context for the research problem, rationale for conducting the study, and the significance of the research. Here are some steps to help you write a strong background of the study:

- Identify the research problem : Start by identifying the research problem that your thesis is addressing. What is the issue that you are trying to solve or explore? Be specific and concise in your problem statement.

- Review the literature: Conduct a thorough review of the relevant literature on the topic. This should include scholarly articles, books, and other sources that are directly related to your research question.

- I dentify gaps in the literature: After reviewing the literature, identify any gaps in the existing research. What questions remain unanswered? What areas have not been explored? This will help you to establish the need for your research.

- Establish the significance of the research: Clearly state the significance of your research. Why is it important to address this research problem? What are the potential implications of your research? How will it contribute to the field?

- Provide an overview of the research design: Provide an overview of the research design and methodology that you will be using in your study. This should include a brief explanation of the research approach, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques.

- State the research objectives and research questions: Clearly state the research objectives and research questions that your study aims to answer. These should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound.

- Summarize the chapter: Summarize the chapter by highlighting the key points and linking them back to the research problem, significance of the study, and research questions.

How to Write Background of The Study in Research Paper

Here are the steps to write the background of the study in a research paper:

- Identify the research problem: Start by identifying the research problem that your study aims to address. This can be a particular issue, a gap in the literature, or a need for further investigation.

- Conduct a literature review: Conduct a thorough literature review to gather information on the topic, identify existing studies, and understand the current state of research. This will help you identify the gap in the literature that your study aims to fill.

- Explain the significance of the study: Explain why your study is important and why it is necessary. This can include the potential impact on the field, the importance to society, or the need to address a particular issue.

- Provide context: Provide context for the research problem by discussing the broader social, economic, or political context that the study is situated in. This can help the reader understand the relevance of the study and its potential implications.

- State the research questions and objectives: State the research questions and objectives that your study aims to address. This will help the reader understand the scope of the study and its purpose.

- Summarize the methodology : Briefly summarize the methodology you used to conduct the study, including the data collection and analysis methods. This can help the reader understand how the study was conducted and its reliability.

Examples of Background of The Study

Here are some examples of the background of the study:

Problem : The prevalence of obesity among children in the United States has reached alarming levels, with nearly one in five children classified as obese.

Significance : Obesity in childhood is associated with numerous negative health outcomes, including increased risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and certain cancers.

Gap in knowledge : Despite efforts to address the obesity epidemic, rates continue to rise. There is a need for effective interventions that target the unique needs of children and their families.

Problem : The use of antibiotics in agriculture has contributed to the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, which poses a significant threat to human health.

Significance : Antibiotic-resistant infections are responsible for thousands of deaths each year and are a major public health concern.

Gap in knowledge: While there is a growing body of research on the use of antibiotics in agriculture, there is still much to be learned about the mechanisms of resistance and the most effective strategies for reducing antibiotic use.

Edxample 3:

Problem : Many low-income communities lack access to healthy food options, leading to high rates of food insecurity and diet-related diseases.

Significance : Poor nutrition is a major contributor to chronic diseases such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Gap in knowledge : While there have been efforts to address food insecurity, there is a need for more research on the barriers to accessing healthy food in low-income communities and effective strategies for increasing access.

Examples of Background of The Study In Research

Here are some real-life examples of how the background of the study can be written in different fields of study:

Example 1 : “There has been a significant increase in the incidence of diabetes in recent years. This has led to an increased demand for effective diabetes management strategies. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of a new diabetes management program in improving patient outcomes.”

Example 2 : “The use of social media has become increasingly prevalent in modern society. Despite its popularity, little is known about the effects of social media use on mental health. This study aims to investigate the relationship between social media use and mental health in young adults.”

Example 3: “Despite significant advancements in cancer treatment, the survival rate for patients with pancreatic cancer remains low. The purpose of this study is to identify potential biomarkers that can be used to improve early detection and treatment of pancreatic cancer.”

Examples of Background of The Study in Proposal

Here are some real-time examples of the background of the study in a proposal:

Example 1 : The prevalence of mental health issues among university students has been increasing over the past decade. This study aims to investigate the causes and impacts of mental health issues on academic performance and wellbeing.

Example 2 : Climate change is a global issue that has significant implications for agriculture in developing countries. This study aims to examine the adaptive capacity of smallholder farmers to climate change and identify effective strategies to enhance their resilience.

Example 3 : The use of social media in political campaigns has become increasingly common in recent years. This study aims to analyze the effectiveness of social media campaigns in mobilizing young voters and influencing their voting behavior.

Example 4 : Employee turnover is a major challenge for organizations, especially in the service sector. This study aims to identify the key factors that influence employee turnover in the hospitality industry and explore effective strategies for reducing turnover rates.

Examples of Background of The Study in Thesis

Here are some real-time examples of the background of the study in the thesis:

Example 1 : “Women’s participation in the workforce has increased significantly over the past few decades. However, women continue to be underrepresented in leadership positions, particularly in male-dominated industries such as technology. This study aims to examine the factors that contribute to the underrepresentation of women in leadership roles in the technology industry, with a focus on organizational culture and gender bias.”

Example 2 : “Mental health is a critical component of overall health and well-being. Despite increased awareness of the importance of mental health, there are still significant gaps in access to mental health services, particularly in low-income and rural communities. This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of a community-based mental health intervention in improving mental health outcomes in underserved populations.”

Example 3: “The use of technology in education has become increasingly widespread, with many schools adopting online learning platforms and digital resources. However, there is limited research on the impact of technology on student learning outcomes and engagement. This study aims to explore the relationship between technology use and academic achievement among middle school students, as well as the factors that mediate this relationship.”

Examples of Background of The Study in Research Paper

Here are some examples of how the background of the study can be written in various fields:

Example 1: The prevalence of obesity has been on the rise globally, with the World Health Organization reporting that approximately 650 million adults were obese in 2016. Obesity is a major risk factor for several chronic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer. In recent years, several interventions have been proposed to address this issue, including lifestyle changes, pharmacotherapy, and bariatric surgery. However, there is a lack of consensus on the most effective intervention for obesity management. This study aims to investigate the efficacy of different interventions for obesity management and identify the most effective one.

Example 2: Antibiotic resistance has become a major public health threat worldwide. Infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria are associated with longer hospital stays, higher healthcare costs, and increased mortality. The inappropriate use of antibiotics is one of the main factors contributing to the development of antibiotic resistance. Despite numerous efforts to promote the rational use of antibiotics, studies have shown that many healthcare providers continue to prescribe antibiotics inappropriately. This study aims to explore the factors influencing healthcare providers’ prescribing behavior and identify strategies to improve antibiotic prescribing practices.

Example 3: Social media has become an integral part of modern communication, with millions of people worldwide using platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Social media has several advantages, including facilitating communication, connecting people, and disseminating information. However, social media use has also been associated with several negative outcomes, including cyberbullying, addiction, and mental health problems. This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on mental health and identify the factors that mediate this relationship.

Purpose of Background of The Study

The primary purpose of the background of the study is to help the reader understand the rationale for the research by presenting the historical, theoretical, and empirical background of the problem.

More specifically, the background of the study aims to:

- Provide a clear understanding of the research problem and its context.

- Identify the gap in knowledge that the study intends to fill.

- Establish the significance of the research problem and its potential contribution to the field.

- Highlight the key concepts, theories, and research findings related to the problem.

- Provide a rationale for the research questions or hypotheses and the research design.

- Identify the limitations and scope of the study.

When to Write Background of The Study

The background of the study should be written early on in the research process, ideally before the research design is finalized and data collection begins. This allows the researcher to clearly articulate the rationale for the study and establish a strong foundation for the research.

The background of the study typically comes after the introduction but before the literature review section. It should provide an overview of the research problem and its context, and also introduce the key concepts, theories, and research findings related to the problem.

Writing the background of the study early on in the research process also helps to identify potential gaps in knowledge and areas for further investigation, which can guide the development of the research questions or hypotheses and the research design. By establishing the significance of the research problem and its potential contribution to the field, the background of the study can also help to justify the research and secure funding or support from stakeholders.

Advantage of Background of The Study

The background of the study has several advantages, including:

- Provides context: The background of the study provides context for the research problem by highlighting the historical, theoretical, and empirical background of the problem. This allows the reader to understand the research problem in its broader context and appreciate its significance.

- Identifies gaps in knowledge: By reviewing the existing literature related to the research problem, the background of the study can identify gaps in knowledge that the study intends to fill. This helps to establish the novelty and originality of the research and its potential contribution to the field.

- Justifies the research : The background of the study helps to justify the research by demonstrating its significance and potential impact. This can be useful in securing funding or support for the research.

- Guides the research design: The background of the study can guide the development of the research questions or hypotheses and the research design by identifying key concepts, theories, and research findings related to the problem. This ensures that the research is grounded in existing knowledge and is designed to address the research problem effectively.

- Establishes credibility: By demonstrating the researcher’s knowledge of the field and the research problem, the background of the study can establish the researcher’s credibility and expertise, which can enhance the trustworthiness and validity of the research.

Disadvantages of Background of The Study

Some Disadvantages of Background of The Study are as follows:

- Time-consuming : Writing a comprehensive background of the study can be time-consuming, especially if the research problem is complex and multifaceted. This can delay the research process and impact the timeline for completing the study.

- Repetitive: The background of the study can sometimes be repetitive, as it often involves summarizing existing research and theories related to the research problem. This can be tedious for the reader and may make the section less engaging.

- Limitations of existing research: The background of the study can reveal the limitations of existing research related to the problem. This can create challenges for the researcher in developing research questions or hypotheses that address the gaps in knowledge identified in the background of the study.

- Bias : The researcher’s biases and perspectives can influence the content and tone of the background of the study. This can impact the reader’s perception of the research problem and may influence the validity of the research.

- Accessibility: Accessing and reviewing the literature related to the research problem can be challenging, especially if the researcher does not have access to a comprehensive database or if the literature is not available in the researcher’s language. This can limit the depth and scope of the background of the study.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Figures in Research Paper – Examples and Guide

Research Recommendations – Examples and Writing...

Scope of the Research – Writing Guide and...

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Research Summary – Structure, Examples and...

APA Table of Contents – Format and Example

How to Write the Discussion Section of a Research Paper

The discussion section of a research paper analyzes and interprets the findings, provides context, compares them with previous studies, identifies limitations, and suggests future research directions.

Updated on September 15, 2023

Structure your discussion section right, and you’ll be cited more often while doing a greater service to the scientific community. So, what actually goes into the discussion section? And how do you write it?

The discussion section of your research paper is where you let the reader know how your study is positioned in the literature, what to take away from your paper, and how your work helps them. It can also include your conclusions and suggestions for future studies.

First, we’ll define all the parts of your discussion paper, and then look into how to write a strong, effective discussion section for your paper or manuscript.

Discussion section: what is it, what it does

The discussion section comes later in your paper, following the introduction, methods, and results. The discussion sets up your study’s conclusions. Its main goals are to present, interpret, and provide a context for your results.

What is it?

The discussion section provides an analysis and interpretation of the findings, compares them with previous studies, identifies limitations, and suggests future directions for research.

This section combines information from the preceding parts of your paper into a coherent story. By this point, the reader already knows why you did your study (introduction), how you did it (methods), and what happened (results). In the discussion, you’ll help the reader connect the ideas from these sections.

Why is it necessary?

The discussion provides context and interpretations for the results. It also answers the questions posed in the introduction. While the results section describes your findings, the discussion explains what they say. This is also where you can describe the impact or implications of your research.

Adds context for your results

Most research studies aim to answer a question, replicate a finding, or address limitations in the literature. These goals are first described in the introduction. However, in the discussion section, the author can refer back to them to explain how the study's objective was achieved.

Shows what your results actually mean and real-world implications

The discussion can also describe the effect of your findings on research or practice. How are your results significant for readers, other researchers, or policymakers?

What to include in your discussion (in the correct order)

A complete and effective discussion section should at least touch on the points described below.

Summary of key findings

The discussion should begin with a brief factual summary of the results. Concisely overview the main results you obtained.

Begin with key findings with supporting evidence

Your results section described a list of findings, but what message do they send when you look at them all together?

Your findings were detailed in the results section, so there’s no need to repeat them here, but do provide at least a few highlights. This will help refresh the reader’s memory and help them focus on the big picture.

Read the first paragraph of the discussion section in this article (PDF) for an example of how to start this part of your paper. Notice how the authors break down their results and follow each description sentence with an explanation of why each finding is relevant.

State clearly and concisely

Following a clear and direct writing style is especially important in the discussion section. After all, this is where you will make some of the most impactful points in your paper. While the results section often contains technical vocabulary, such as statistical terms, the discussion section lets you describe your findings more clearly.

Interpretation of results

Once you’ve given your reader an overview of your results, you need to interpret those results. In other words, what do your results mean? Discuss the findings’ implications and significance in relation to your research question or hypothesis.

Analyze and interpret your findings

Look into your findings and explore what’s behind them or what may have caused them. If your introduction cited theories or studies that could explain your findings, use these sources as a basis to discuss your results.

For example, look at the second paragraph in the discussion section of this article on waggling honey bees. Here, the authors explore their results based on information from the literature.

Unexpected or contradictory results

Sometimes, your findings are not what you expect. Here’s where you describe this and try to find a reason for it. Could it be because of the method you used? Does it have something to do with the variables analyzed? Comparing your methods with those of other similar studies can help with this task.

Context and comparison with previous work

Refer to related studies to place your research in a larger context and the literature. Compare and contrast your findings with existing literature, highlighting similarities, differences, and/or contradictions.

How your work compares or contrasts with previous work

Studies with similar findings to yours can be cited to show the strength of your findings. Information from these studies can also be used to help explain your results. Differences between your findings and others in the literature can also be discussed here.

How to divide this section into subsections

If you have more than one objective in your study or many key findings, you can dedicate a separate section to each of these. Here’s an example of this approach. You can see that the discussion section is divided into topics and even has a separate heading for each of them.

Limitations

Many journals require you to include the limitations of your study in the discussion. Even if they don’t, there are good reasons to mention these in your paper.

Why limitations don’t have a negative connotation

A study’s limitations are points to be improved upon in future research. While some of these may be flaws in your method, many may be due to factors you couldn’t predict.

Examples include time constraints or small sample sizes. Pointing this out will help future researchers avoid or address these issues. This part of the discussion can also include any attempts you have made to reduce the impact of these limitations, as in this study .

How limitations add to a researcher's credibility

Pointing out the limitations of your study demonstrates transparency. It also shows that you know your methods well and can conduct a critical assessment of them.

Implications and significance

The final paragraph of the discussion section should contain the take-home messages for your study. It can also cite the “strong points” of your study, to contrast with the limitations section.

Restate your hypothesis

Remind the reader what your hypothesis was before you conducted the study.

How was it proven or disproven?

Identify your main findings and describe how they relate to your hypothesis.

How your results contribute to the literature

Were you able to answer your research question? Or address a gap in the literature?

Future implications of your research

Describe the impact that your results may have on the topic of study. Your results may show, for instance, that there are still limitations in the literature for future studies to address. There may be a need for studies that extend your findings in a specific way. You also may need additional research to corroborate your findings.

Sample discussion section

This fictitious example covers all the aspects discussed above. Your actual discussion section will probably be much longer, but you can read this to get an idea of everything your discussion should cover.

Our results showed that the presence of cats in a household is associated with higher levels of perceived happiness by its human occupants. These findings support our hypothesis and demonstrate the association between pet ownership and well-being.

The present findings align with those of Bao and Schreer (2016) and Hardie et al. (2023), who observed greater life satisfaction in pet owners relative to non-owners. Although the present study did not directly evaluate life satisfaction, this factor may explain the association between happiness and cat ownership observed in our sample.

Our findings must be interpreted in light of some limitations, such as the focus on cat ownership only rather than pets as a whole. This may limit the generalizability of our results.

Nevertheless, this study had several strengths. These include its strict exclusion criteria and use of a standardized assessment instrument to investigate the relationships between pets and owners. These attributes bolster the accuracy of our results and reduce the influence of confounding factors, increasing the strength of our conclusions. Future studies may examine the factors that mediate the association between pet ownership and happiness to better comprehend this phenomenon.

This brief discussion begins with a quick summary of the results and hypothesis. The next paragraph cites previous research and compares its findings to those of this study. Information from previous studies is also used to help interpret the findings. After discussing the results of the study, some limitations are pointed out. The paper also explains why these limitations may influence the interpretation of results. Then, final conclusions are drawn based on the study, and directions for future research are suggested.

How to make your discussion flow naturally

If you find writing in scientific English challenging, the discussion and conclusions are often the hardest parts of the paper to write. That’s because you’re not just listing up studies, methods, and outcomes. You’re actually expressing your thoughts and interpretations in words.

- How formal should it be?

- What words should you use, or not use?

- How do you meet strict word limits, or make it longer and more informative?

Always give it your best, but sometimes a helping hand can, well, help. Getting a professional edit can help clarify your work’s importance while improving the English used to explain it. When readers know the value of your work, they’ll cite it. We’ll assign your study to an expert editor knowledgeable in your area of research. Their work will clarify your discussion, helping it to tell your story. Find out more about AJE Editing.

Adam Goulston, PsyD, MS, MBA, MISD, ELS

Science Marketing Consultant

See our "Privacy Policy"

Ensure your structure and ideas are consistent and clearly communicated

Pair your Premium Editing with our add-on service Presubmission Review for an overall assessment of your manuscript.

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

How to Write the Methods Section of a Research Paper

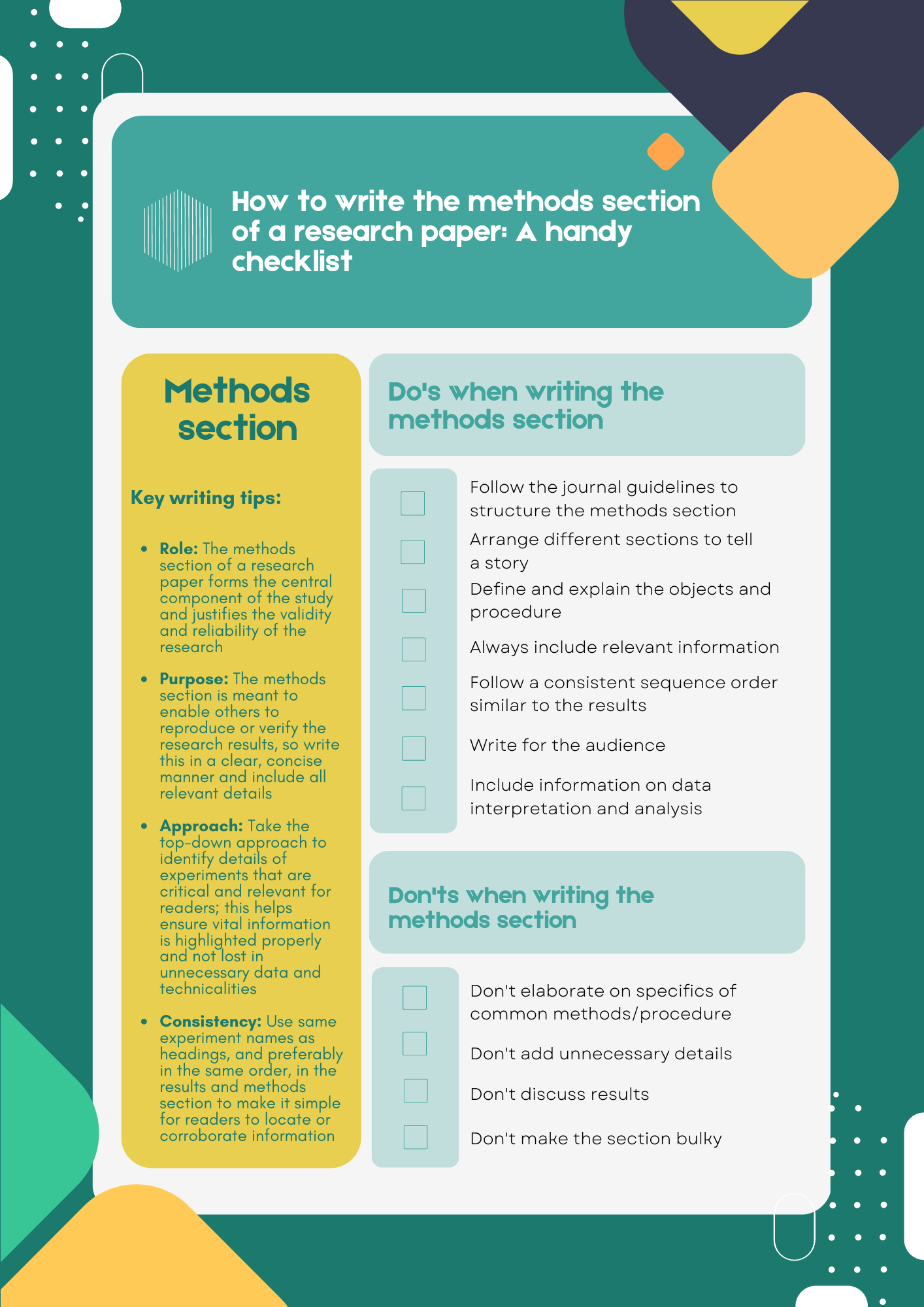

Writing a research paper is both an art and a skill, and knowing how to write the methods section of a research paper is the first crucial step in mastering scientific writing. If, like the majority of early career researchers, you believe that the methods section is the simplest to write and needs little in the way of careful consideration or thought, this article will help you understand it is not 1 .

We have all probably asked our supervisors, coworkers, or search engines “ how to write a methods section of a research paper ” at some point in our scientific careers, so you are not alone if that’s how you ended up here. Even for seasoned researchers, selecting what to include in the methods section from a wealth of experimental information can occasionally be a source of distress and perplexity.

Additionally, journal specifications, in some cases, may make it more of a requirement rather than a choice to provide a selective yet descriptive account of the experimental procedure. Hence, knowing these nuances of how to write the methods section of a research paper is critical to its success. The methods section of the research paper is not supposed to be a detailed heavy, dull section that some researchers tend to write; rather, it should be the central component of the study that justifies the validity and reliability of the research.

Are you still unsure of how the methods section of a research paper forms the basis of every investigation? Consider the last article you read but ignore the methods section and concentrate on the other parts of the paper . Now think whether you could repeat the study and be sure of the credibility of the findings despite knowing the literature review and even having the data in front of you. You have the answer!

Having established the importance of the methods section , the next question is how to write the methods section of a research paper that unifies the overall study. The purpose of the methods section , which was earlier called as Materials and Methods , is to describe how the authors went about answering the “research question” at hand. Here, the objective is to tell a coherent story that gives a detailed account of how the study was conducted, the rationale behind specific experimental procedures, the experimental setup, objects (variables) involved, the research protocol employed, tools utilized to measure, calculations and measurements, and the analysis of the collected data 2 .

In this article, we will take a deep dive into this topic and provide a detailed overview of how to write the methods section of a research paper . For the sake of clarity, we have separated the subject into various sections with corresponding subheadings.

Table of Contents

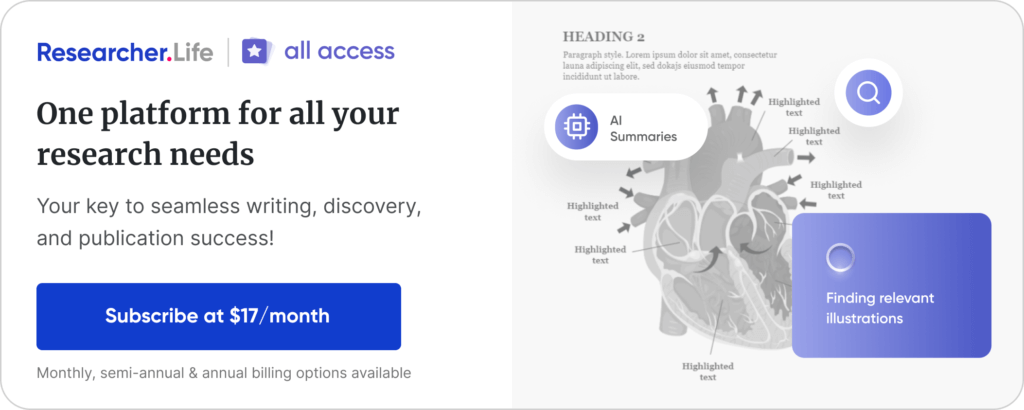

What is the methods section of a research paper ?

The methods section is a fundamental section of any paper since it typically discusses the ‘ what ’, ‘ how ’, ‘ which ’, and ‘ why ’ of the study, which is necessary to arrive at the final conclusions. In a research article, the introduction, which serves to set the foundation for comprehending the background and results is usually followed by the methods section, which precedes the result and discussion sections. The methods section must explicitly state what was done, how it was done, which equipment, tools and techniques were utilized, how were the measurements/calculations taken, and why specific research protocols, software, and analytical methods were employed.

Why is the methods section important?

The primary goal of the methods section is to provide pertinent details about the experimental approach so that the reader may put the results in perspective and, if necessary, replicate the findings 3 . This section offers readers the chance to evaluate the reliability and validity of any study. In short, it also serves as the study’s blueprint, assisting researchers who might be unsure about any other portion in establishing the study’s context and validity. The methods plays a rather crucial role in determining the fate of the article; an incomplete and unreliable methods section can frequently result in early rejections and may lead to numerous rounds of modifications during the publication process. This means that the reviewers also often use methods section to assess the reliability and validity of the research protocol and the data analysis employed to address the research topic. In other words, the purpose of the methods section is to demonstrate the research acumen and subject-matter expertise of the author(s) in their field.

Structure of methods section of a research paper

Similar to the research paper, the methods section also follows a defined structure; this may be dictated by the guidelines of a specific journal or can be presented in a chronological or thematic manner based on the study type. When writing the methods section , authors should keep in mind that they are telling a story about how the research was conducted. They should only report relevant information to avoid confusing the reader and include details that would aid in connecting various aspects of the entire research activity together. It is generally advisable to present experiments in the order in which they were conducted. This facilitates the logical flow of the research and allows readers to follow the progression of the study design.

It is also essential to clearly state the rationale behind each experiment and how the findings of earlier experiments informed the design or interpretation of later experiments. This allows the readers to understand the overall purpose of the study design and the significance of each experiment within that context. However, depending on the particular research question and method, it may make sense to present information in a different order; therefore, authors must select the best structure and strategy for their individual studies.

In cases where there is a lot of information, divide the sections into subheadings to cover the pertinent details. If the journal guidelines pose restrictions on the word limit , additional important information can be supplied in the supplementary files. A simple rule of thumb for sectioning the method section is to begin by explaining the methodological approach ( what was done ), describing the data collection methods ( how it was done ), providing the analysis method ( how the data was analyzed ), and explaining the rationale for choosing the methodological strategy. This is described in detail in the upcoming sections.

How to write the methods section of a research paper

Contrary to widespread assumption, the methods section of a research paper should be prepared once the study is complete to prevent missing any key parameter. Hence, please make sure that all relevant experiments are done before you start writing a methods section . The next step for authors is to look up any applicable academic style manuals or journal-specific standards to ensure that the methods section is formatted correctly. The methods section of a research paper typically constitutes materials and methods; while writing this section, authors usually arrange the information under each category.

The materials category describes the samples, materials, treatments, and instruments, while experimental design, sample preparation, data collection, and data analysis are a part of the method category. According to the nature of the study, authors should include additional subsections within the methods section, such as ethical considerations like the declaration of Helsinki (for studies involving human subjects), demographic information of the participants, and any other crucial information that can affect the output of the study. Simply put, the methods section has two major components: content and format. Here is an easy checklist for you to consider if you are struggling with how to write the methods section of a research paper .

- Explain the research design, subjects, and sample details

- Include information on inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Mention ethical or any other permission required for the study

- Include information about materials, experimental setup, tools, and software

- Add details of data collection and analysis methods

- Incorporate how research biases were avoided or confounding variables were controlled

- Evaluate and justify the experimental procedure selected to address the research question

- Provide precise and clear details of each experiment

- Flowcharts, infographics, or tables can be used to present complex information

- Use past tense to show that the experiments have been done

- Follow academic style guides (such as APA or MLA ) to structure the content

- Citations should be included as per standard protocols in the field

Now that you know how to write the methods section of a research paper , let’s address another challenge researchers face while writing the methods section —what to include in the methods section . How much information is too much is not always obvious when it comes to trying to include data in the methods section of a paper. In the next section, we examine this issue and explore potential solutions.

What to include in the methods section of a research paper

The technical nature of the methods section occasionally makes it harder to present the information clearly and concisely while staying within the study context. Many young researchers tend to veer off subject significantly, and they frequently commit the sin of becoming bogged down in itty bitty details, making the text harder to read and impairing its overall flow. However, the best way to write the methods section is to start with crucial components of the experiments. If you have trouble deciding which elements are essential, think about leaving out those that would make it more challenging to comprehend the context or replicate the results. The top-down approach helps to ensure all relevant information is incorporated and vital information is not lost in technicalities. Next, remember to add details that are significant to assess the validity and reliability of the study. Here is a simple checklist for you to follow ( bonus tip: you can also make a checklist for your own study to avoid missing any critical information while writing the methods section ).

- Structuring the methods section : Authors should diligently follow journal guidelines and adhere to the specific author instructions provided when writing the methods section . Journals typically have specific guidelines for formatting the methods section ; for example, Frontiers in Plant Sciences advises arranging the materials and methods section by subheading and citing relevant literature. There are several standardized checklists available for different study types in the biomedical field, including CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) for randomized clinical trials, PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis) for systematic reviews and meta-analysis, and STROBE (STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology) for cohort, case-control, cross-sectional studies. Before starting the methods section , check the checklist available in your field that can function as a guide.