- Privacy Policy

Home » Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types and Guide

Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types and Guide

Table of Contents

Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is a type of research methodology that focuses on exploring and understanding people’s beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, and experiences through the collection and analysis of non-numerical data. It seeks to answer research questions through the examination of subjective data, such as interviews, focus groups, observations, and textual analysis.

Qualitative research aims to uncover the meaning and significance of social phenomena, and it typically involves a more flexible and iterative approach to data collection and analysis compared to quantitative research. Qualitative research is often used in fields such as sociology, anthropology, psychology, and education.

Qualitative Research Methods

Qualitative Research Methods are as follows:

One-to-One Interview

This method involves conducting an interview with a single participant to gain a detailed understanding of their experiences, attitudes, and beliefs. One-to-one interviews can be conducted in-person, over the phone, or through video conferencing. The interviewer typically uses open-ended questions to encourage the participant to share their thoughts and feelings. One-to-one interviews are useful for gaining detailed insights into individual experiences.

Focus Groups

This method involves bringing together a group of people to discuss a specific topic in a structured setting. The focus group is led by a moderator who guides the discussion and encourages participants to share their thoughts and opinions. Focus groups are useful for generating ideas and insights, exploring social norms and attitudes, and understanding group dynamics.

Ethnographic Studies

This method involves immersing oneself in a culture or community to gain a deep understanding of its norms, beliefs, and practices. Ethnographic studies typically involve long-term fieldwork and observation, as well as interviews and document analysis. Ethnographic studies are useful for understanding the cultural context of social phenomena and for gaining a holistic understanding of complex social processes.

Text Analysis

This method involves analyzing written or spoken language to identify patterns and themes. Text analysis can be quantitative or qualitative. Qualitative text analysis involves close reading and interpretation of texts to identify recurring themes, concepts, and patterns. Text analysis is useful for understanding media messages, public discourse, and cultural trends.

This method involves an in-depth examination of a single person, group, or event to gain an understanding of complex phenomena. Case studies typically involve a combination of data collection methods, such as interviews, observations, and document analysis, to provide a comprehensive understanding of the case. Case studies are useful for exploring unique or rare cases, and for generating hypotheses for further research.

Process of Observation

This method involves systematically observing and recording behaviors and interactions in natural settings. The observer may take notes, use audio or video recordings, or use other methods to document what they see. Process of observation is useful for understanding social interactions, cultural practices, and the context in which behaviors occur.

Record Keeping

This method involves keeping detailed records of observations, interviews, and other data collected during the research process. Record keeping is essential for ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the data, and for providing a basis for analysis and interpretation.

This method involves collecting data from a large sample of participants through a structured questionnaire. Surveys can be conducted in person, over the phone, through mail, or online. Surveys are useful for collecting data on attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors, and for identifying patterns and trends in a population.

Qualitative data analysis is a process of turning unstructured data into meaningful insights. It involves extracting and organizing information from sources like interviews, focus groups, and surveys. The goal is to understand people’s attitudes, behaviors, and motivations

Qualitative Research Analysis Methods

Qualitative Research analysis methods involve a systematic approach to interpreting and making sense of the data collected in qualitative research. Here are some common qualitative data analysis methods:

Thematic Analysis

This method involves identifying patterns or themes in the data that are relevant to the research question. The researcher reviews the data, identifies keywords or phrases, and groups them into categories or themes. Thematic analysis is useful for identifying patterns across multiple data sources and for generating new insights into the research topic.

Content Analysis

This method involves analyzing the content of written or spoken language to identify key themes or concepts. Content analysis can be quantitative or qualitative. Qualitative content analysis involves close reading and interpretation of texts to identify recurring themes, concepts, and patterns. Content analysis is useful for identifying patterns in media messages, public discourse, and cultural trends.

Discourse Analysis

This method involves analyzing language to understand how it constructs meaning and shapes social interactions. Discourse analysis can involve a variety of methods, such as conversation analysis, critical discourse analysis, and narrative analysis. Discourse analysis is useful for understanding how language shapes social interactions, cultural norms, and power relationships.

Grounded Theory Analysis

This method involves developing a theory or explanation based on the data collected. Grounded theory analysis starts with the data and uses an iterative process of coding and analysis to identify patterns and themes in the data. The theory or explanation that emerges is grounded in the data, rather than preconceived hypotheses. Grounded theory analysis is useful for understanding complex social phenomena and for generating new theoretical insights.

Narrative Analysis

This method involves analyzing the stories or narratives that participants share to gain insights into their experiences, attitudes, and beliefs. Narrative analysis can involve a variety of methods, such as structural analysis, thematic analysis, and discourse analysis. Narrative analysis is useful for understanding how individuals construct their identities, make sense of their experiences, and communicate their values and beliefs.

Phenomenological Analysis

This method involves analyzing how individuals make sense of their experiences and the meanings they attach to them. Phenomenological analysis typically involves in-depth interviews with participants to explore their experiences in detail. Phenomenological analysis is useful for understanding subjective experiences and for developing a rich understanding of human consciousness.

Comparative Analysis

This method involves comparing and contrasting data across different cases or groups to identify similarities and differences. Comparative analysis can be used to identify patterns or themes that are common across multiple cases, as well as to identify unique or distinctive features of individual cases. Comparative analysis is useful for understanding how social phenomena vary across different contexts and groups.

Applications of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research has many applications across different fields and industries. Here are some examples of how qualitative research is used:

- Market Research: Qualitative research is often used in market research to understand consumer attitudes, behaviors, and preferences. Researchers conduct focus groups and one-on-one interviews with consumers to gather insights into their experiences and perceptions of products and services.

- Health Care: Qualitative research is used in health care to explore patient experiences and perspectives on health and illness. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with patients and their families to gather information on their experiences with different health care providers and treatments.

- Education: Qualitative research is used in education to understand student experiences and to develop effective teaching strategies. Researchers conduct classroom observations and interviews with students and teachers to gather insights into classroom dynamics and instructional practices.

- Social Work : Qualitative research is used in social work to explore social problems and to develop interventions to address them. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with individuals and families to understand their experiences with poverty, discrimination, and other social problems.

- Anthropology : Qualitative research is used in anthropology to understand different cultures and societies. Researchers conduct ethnographic studies and observe and interview members of different cultural groups to gain insights into their beliefs, practices, and social structures.

- Psychology : Qualitative research is used in psychology to understand human behavior and mental processes. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with individuals to explore their thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

- Public Policy : Qualitative research is used in public policy to explore public attitudes and to inform policy decisions. Researchers conduct focus groups and one-on-one interviews with members of the public to gather insights into their perspectives on different policy issues.

How to Conduct Qualitative Research

Here are some general steps for conducting qualitative research:

- Identify your research question: Qualitative research starts with a research question or set of questions that you want to explore. This question should be focused and specific, but also broad enough to allow for exploration and discovery.

- Select your research design: There are different types of qualitative research designs, including ethnography, case study, grounded theory, and phenomenology. You should select a design that aligns with your research question and that will allow you to gather the data you need to answer your research question.

- Recruit participants: Once you have your research question and design, you need to recruit participants. The number of participants you need will depend on your research design and the scope of your research. You can recruit participants through advertisements, social media, or through personal networks.

- Collect data: There are different methods for collecting qualitative data, including interviews, focus groups, observation, and document analysis. You should select the method or methods that align with your research design and that will allow you to gather the data you need to answer your research question.

- Analyze data: Once you have collected your data, you need to analyze it. This involves reviewing your data, identifying patterns and themes, and developing codes to organize your data. You can use different software programs to help you analyze your data, or you can do it manually.

- Interpret data: Once you have analyzed your data, you need to interpret it. This involves making sense of the patterns and themes you have identified, and developing insights and conclusions that answer your research question. You should be guided by your research question and use your data to support your conclusions.

- Communicate results: Once you have interpreted your data, you need to communicate your results. This can be done through academic papers, presentations, or reports. You should be clear and concise in your communication, and use examples and quotes from your data to support your findings.

Examples of Qualitative Research

Here are some real-time examples of qualitative research:

- Customer Feedback: A company may conduct qualitative research to understand the feedback and experiences of its customers. This may involve conducting focus groups or one-on-one interviews with customers to gather insights into their attitudes, behaviors, and preferences.

- Healthcare : A healthcare provider may conduct qualitative research to explore patient experiences and perspectives on health and illness. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with patients and their families to gather information on their experiences with different health care providers and treatments.

- Education : An educational institution may conduct qualitative research to understand student experiences and to develop effective teaching strategies. This may involve conducting classroom observations and interviews with students and teachers to gather insights into classroom dynamics and instructional practices.

- Social Work: A social worker may conduct qualitative research to explore social problems and to develop interventions to address them. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with individuals and families to understand their experiences with poverty, discrimination, and other social problems.

- Anthropology : An anthropologist may conduct qualitative research to understand different cultures and societies. This may involve conducting ethnographic studies and observing and interviewing members of different cultural groups to gain insights into their beliefs, practices, and social structures.

- Psychology : A psychologist may conduct qualitative research to understand human behavior and mental processes. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with individuals to explore their thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

- Public Policy: A government agency or non-profit organization may conduct qualitative research to explore public attitudes and to inform policy decisions. This may involve conducting focus groups and one-on-one interviews with members of the public to gather insights into their perspectives on different policy issues.

Purpose of Qualitative Research

The purpose of qualitative research is to explore and understand the subjective experiences, behaviors, and perspectives of individuals or groups in a particular context. Unlike quantitative research, which focuses on numerical data and statistical analysis, qualitative research aims to provide in-depth, descriptive information that can help researchers develop insights and theories about complex social phenomena.

Qualitative research can serve multiple purposes, including:

- Exploring new or emerging phenomena : Qualitative research can be useful for exploring new or emerging phenomena, such as new technologies or social trends. This type of research can help researchers develop a deeper understanding of these phenomena and identify potential areas for further study.

- Understanding complex social phenomena : Qualitative research can be useful for exploring complex social phenomena, such as cultural beliefs, social norms, or political processes. This type of research can help researchers develop a more nuanced understanding of these phenomena and identify factors that may influence them.

- Generating new theories or hypotheses: Qualitative research can be useful for generating new theories or hypotheses about social phenomena. By gathering rich, detailed data about individuals’ experiences and perspectives, researchers can develop insights that may challenge existing theories or lead to new lines of inquiry.

- Providing context for quantitative data: Qualitative research can be useful for providing context for quantitative data. By gathering qualitative data alongside quantitative data, researchers can develop a more complete understanding of complex social phenomena and identify potential explanations for quantitative findings.

When to use Qualitative Research

Here are some situations where qualitative research may be appropriate:

- Exploring a new area: If little is known about a particular topic, qualitative research can help to identify key issues, generate hypotheses, and develop new theories.

- Understanding complex phenomena: Qualitative research can be used to investigate complex social, cultural, or organizational phenomena that are difficult to measure quantitatively.

- Investigating subjective experiences: Qualitative research is particularly useful for investigating the subjective experiences of individuals or groups, such as their attitudes, beliefs, values, or emotions.

- Conducting formative research: Qualitative research can be used in the early stages of a research project to develop research questions, identify potential research participants, and refine research methods.

- Evaluating interventions or programs: Qualitative research can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions or programs by collecting data on participants’ experiences, attitudes, and behaviors.

Characteristics of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is characterized by several key features, including:

- Focus on subjective experience: Qualitative research is concerned with understanding the subjective experiences, beliefs, and perspectives of individuals or groups in a particular context. Researchers aim to explore the meanings that people attach to their experiences and to understand the social and cultural factors that shape these meanings.

- Use of open-ended questions: Qualitative research relies on open-ended questions that allow participants to provide detailed, in-depth responses. Researchers seek to elicit rich, descriptive data that can provide insights into participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Sampling-based on purpose and diversity: Qualitative research often involves purposive sampling, in which participants are selected based on specific criteria related to the research question. Researchers may also seek to include participants with diverse experiences and perspectives to capture a range of viewpoints.

- Data collection through multiple methods: Qualitative research typically involves the use of multiple data collection methods, such as in-depth interviews, focus groups, and observation. This allows researchers to gather rich, detailed data from multiple sources, which can provide a more complete picture of participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Inductive data analysis: Qualitative research relies on inductive data analysis, in which researchers develop theories and insights based on the data rather than testing pre-existing hypotheses. Researchers use coding and thematic analysis to identify patterns and themes in the data and to develop theories and explanations based on these patterns.

- Emphasis on researcher reflexivity: Qualitative research recognizes the importance of the researcher’s role in shaping the research process and outcomes. Researchers are encouraged to reflect on their own biases and assumptions and to be transparent about their role in the research process.

Advantages of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research offers several advantages over other research methods, including:

- Depth and detail: Qualitative research allows researchers to gather rich, detailed data that provides a deeper understanding of complex social phenomena. Through in-depth interviews, focus groups, and observation, researchers can gather detailed information about participants’ experiences and perspectives that may be missed by other research methods.

- Flexibility : Qualitative research is a flexible approach that allows researchers to adapt their methods to the research question and context. Researchers can adjust their research methods in real-time to gather more information or explore unexpected findings.

- Contextual understanding: Qualitative research is well-suited to exploring the social and cultural context in which individuals or groups are situated. Researchers can gather information about cultural norms, social structures, and historical events that may influence participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Participant perspective : Qualitative research prioritizes the perspective of participants, allowing researchers to explore subjective experiences and understand the meanings that participants attach to their experiences.

- Theory development: Qualitative research can contribute to the development of new theories and insights about complex social phenomena. By gathering rich, detailed data and using inductive data analysis, researchers can develop new theories and explanations that may challenge existing understandings.

- Validity : Qualitative research can offer high validity by using multiple data collection methods, purposive and diverse sampling, and researcher reflexivity. This can help ensure that findings are credible and trustworthy.

Limitations of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research also has some limitations, including:

- Subjectivity : Qualitative research relies on the subjective interpretation of researchers, which can introduce bias into the research process. The researcher’s perspective, beliefs, and experiences can influence the way data is collected, analyzed, and interpreted.

- Limited generalizability: Qualitative research typically involves small, purposive samples that may not be representative of larger populations. This limits the generalizability of findings to other contexts or populations.

- Time-consuming: Qualitative research can be a time-consuming process, requiring significant resources for data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

- Resource-intensive: Qualitative research may require more resources than other research methods, including specialized training for researchers, specialized software for data analysis, and transcription services.

- Limited reliability: Qualitative research may be less reliable than quantitative research, as it relies on the subjective interpretation of researchers. This can make it difficult to replicate findings or compare results across different studies.

- Ethics and confidentiality: Qualitative research involves collecting sensitive information from participants, which raises ethical concerns about confidentiality and informed consent. Researchers must take care to protect the privacy and confidentiality of participants and obtain informed consent.

Also see Research Methods

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Applied Research – Types, Methods and Examples

One-to-One Interview – Methods and Guide

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

Exploratory Research – Types, Methods and...

Quasi-Experimental Research Design – Types...

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Prev Med

Qualitative Methods in Health Care Research

Vishnu renjith.

School of Nursing and Midwifery, Royal College of Surgeons Ireland - Bahrain (RCSI Bahrain), Al Sayh Muharraq Governorate, Bahrain

Renjulal Yesodharan

1 Department of Mental Health Nursing, Manipal College of Nursing Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India

Judith A. Noronha

2 Department of OBG Nursing, Manipal College of Nursing Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India

Elissa Ladd

3 School of Nursing, MGH Institute of Health Professions, Boston, USA

Anice George

4 Department of Child Health Nursing, Manipal College of Nursing Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India

Healthcare research is a systematic inquiry intended to generate robust evidence about important issues in the fields of medicine and healthcare. Qualitative research has ample possibilities within the arena of healthcare research. This article aims to inform healthcare professionals regarding qualitative research, its significance, and applicability in the field of healthcare. A wide variety of phenomena that cannot be explained using the quantitative approach can be explored and conveyed using a qualitative method. The major types of qualitative research designs are narrative research, phenomenological research, grounded theory research, ethnographic research, historical research, and case study research. The greatest strength of the qualitative research approach lies in the richness and depth of the healthcare exploration and description it makes. In health research, these methods are considered as the most humanistic and person-centered way of discovering and uncovering thoughts and actions of human beings.

Introduction

Healthcare research is a systematic inquiry intended to generate trustworthy evidence about issues in the field of medicine and healthcare. The three principal approaches to health research are the quantitative, the qualitative, and the mixed methods approach. The quantitative research method uses data, which are measures of values and counts and are often described using statistical methods which in turn aids the researcher to draw inferences. Qualitative research incorporates the recording, interpreting, and analyzing of non-numeric data with an attempt to uncover the deeper meanings of human experiences and behaviors. Mixed methods research, the third methodological approach, involves collection and analysis of both qualitative and quantitative information with an objective to solve different but related questions, or at times the same questions.[ 1 , 2 ]

In healthcare, qualitative research is widely used to understand patterns of health behaviors, describe lived experiences, develop behavioral theories, explore healthcare needs, and design interventions.[ 1 , 2 , 3 ] Because of its ample applications in healthcare, there has been a tremendous increase in the number of health research studies undertaken using qualitative methodology.[ 4 , 5 ] This article discusses qualitative research methods, their significance, and applicability in the arena of healthcare.

Qualitative Research

Diverse academic and non-academic disciplines utilize qualitative research as a method of inquiry to understand human behavior and experiences.[ 6 , 7 ] According to Munhall, “Qualitative research involves broadly stated questions about human experiences and realities, studied through sustained contact with the individual in their natural environments and producing rich, descriptive data that will help us to understand those individual's experiences.”[ 8 ]

Significance of Qualitative Research

The qualitative method of inquiry examines the 'how' and 'why' of decision making, rather than the 'when,' 'what,' and 'where.'[ 7 ] Unlike quantitative methods, the objective of qualitative inquiry is to explore, narrate, and explain the phenomena and make sense of the complex reality. Health interventions, explanatory health models, and medical-social theories could be developed as an outcome of qualitative research.[ 9 ] Understanding the richness and complexity of human behavior is the crux of qualitative research.

Differences between Quantitative and Qualitative Research

The quantitative and qualitative forms of inquiry vary based on their underlying objectives. They are in no way opposed to each other; instead, these two methods are like two sides of a coin. The critical differences between quantitative and qualitative research are summarized in Table 1 .[ 1 , 10 , 11 ]

Differences between quantitative and qualitative research

Qualitative Research Questions and Purpose Statements

Qualitative questions are exploratory and are open-ended. A well-formulated study question forms the basis for developing a protocol, guides the selection of design, and data collection methods. Qualitative research questions generally involve two parts, a central question and related subquestions. The central question is directed towards the primary phenomenon under study, whereas the subquestions explore the subareas of focus. It is advised not to have more than five to seven subquestions. A commonly used framework for designing a qualitative research question is the 'PCO framework' wherein, P stands for the population under study, C stands for the context of exploration, and O stands for the outcome/s of interest.[ 12 ] The PCO framework guides researchers in crafting a focused study question.

Example: In the question, “What are the experiences of mothers on parenting children with Thalassemia?”, the population is “mothers of children with Thalassemia,” the context is “parenting children with Thalassemia,” and the outcome of interest is “experiences.”

The purpose statement specifies the broad focus of the study, identifies the approach, and provides direction for the overall goal of the study. The major components of a purpose statement include the central phenomenon under investigation, the study design and the population of interest. Qualitative research does not require a-priori hypothesis.[ 13 , 14 , 15 ]

Example: Borimnejad et al . undertook a qualitative research on the lived experiences of women suffering from vitiligo. The purpose of this study was, “to explore lived experiences of women suffering from vitiligo using a hermeneutic phenomenological approach.” [ 16 ]

Review of the Literature

In quantitative research, the researchers do an extensive review of scientific literature prior to the commencement of the study. However, in qualitative research, only a minimal literature search is conducted at the beginning of the study. This is to ensure that the researcher is not influenced by the existing understanding of the phenomenon under the study. The minimal literature review will help the researchers to avoid the conceptual pollution of the phenomenon being studied. Nonetheless, an extensive review of the literature is conducted after data collection and analysis.[ 15 ]

Reflexivity

Reflexivity refers to critical self-appraisal about one's own biases, values, preferences, and preconceptions about the phenomenon under investigation. Maintaining a reflexive diary/journal is a widely recognized way to foster reflexivity. According to Creswell, “Reflexivity increases the credibility of the study by enhancing more neutral interpretations.”[ 7 ]

Types of Qualitative Research Designs

The qualitative research approach encompasses a wide array of research designs. The words such as types, traditions, designs, strategies of inquiry, varieties, and methods are used interchangeably. The major types of qualitative research designs are narrative research, phenomenological research, grounded theory research, ethnographic research, historical research, and case study research.[ 1 , 7 , 10 ]

Narrative research

Narrative research focuses on exploring the life of an individual and is ideally suited to tell the stories of individual experiences.[ 17 ] The purpose of narrative research is to utilize 'story telling' as a method in communicating an individual's experience to a larger audience.[ 18 ] The roots of narrative inquiry extend to humanities including anthropology, literature, psychology, education, history, and sociology. Narrative research encompasses the study of individual experiences and learning the significance of those experiences. The data collection procedures include mainly interviews, field notes, letters, photographs, diaries, and documents collected from one or more individuals. Data analysis involves the analysis of the stories or experiences through “re-storying of stories” and developing themes usually in chronological order of events. Rolls and Payne argued that narrative research is a valuable approach in health care research, to gain deeper insight into patient's experiences.[ 19 ]

Example: Karlsson et al . undertook a narrative inquiry to “explore how people with Alzheimer's disease present their life story.” Data were collected from nine participants. They were asked to describe about their life experiences from childhood to adulthood, then to current life and their views about the future life. [ 20 ]

Phenomenological research

Phenomenology is a philosophical tradition developed by German philosopher Edmond Husserl. His student Martin Heidegger did further developments in this methodology. It defines the 'essence' of individual's experiences regarding a certain phenomenon.[ 1 ] The methodology has its origin from philosophy, psychology, and education. The purpose of qualitative research is to understand the people's everyday life experiences and reduce it into the central meaning or the 'essence of the experience'.[ 21 , 22 ] The unit of analysis of phenomenology is the individuals who have had similar experiences of the phenomenon. Interviews with individuals are mainly considered for the data collection, though, documents and observations are also useful. Data analysis includes identification of significant meaning elements, textural description (what was experienced), structural description (how was it experienced), and description of 'essence' of experience.[ 1 , 7 , 21 ] The phenomenological approach is further divided into descriptive and interpretive phenomenology. Descriptive phenomenology focuses on the understanding of the essence of experiences and is best suited in situations that need to describe the lived phenomenon. Hermeneutic phenomenology or Interpretive phenomenology moves beyond the description to uncover the meanings that are not explicitly evident. The researcher tries to interpret the phenomenon, based on their judgment rather than just describing it.[ 7 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ]

Example: A phenomenological study conducted by Cornelio et al . aimed at describing the lived experiences of mothers in parenting children with leukemia. Data from ten mothers were collected using in-depth semi-structured interviews and were analyzed using Husserl's method of phenomenology. Themes such as “pivotal moment in life”, “the experience of being with a seriously ill child”, “having to keep distance with the relatives”, “overcoming the financial and social commitments”, “responding to challenges”, “experience of faith as being key to survival”, “health concerns of the present and future”, and “optimism” were derived. The researchers reported the essence of the study as “chronic illness such as leukemia in children results in a negative impact on the child and on the mother.” [ 25 ]

Grounded Theory Research

Grounded theory has its base in sociology and propagated by two sociologists, Barney Glaser, and Anselm Strauss.[ 26 ] The primary purpose of grounded theory is to discover or generate theory in the context of the social process being studied. The major difference between grounded theory and other approaches lies in its emphasis on theory generation and development. The name grounded theory comes from its ability to induce a theory grounded in the reality of study participants.[ 7 , 27 ] Data collection in grounded theory research involves recording interviews from many individuals until data saturation. Constant comparative analysis, theoretical sampling, theoretical coding, and theoretical saturation are unique features of grounded theory research.[ 26 , 27 , 28 ] Data analysis includes analyzing data through 'open coding,' 'axial coding,' and 'selective coding.'[ 1 , 7 ] Open coding is the first level of abstraction, and it refers to the creation of a broad initial range of categories, axial coding is the procedure of understanding connections between the open codes, whereas selective coding relates to the process of connecting the axial codes to formulate a theory.[ 1 , 7 ] Results of the grounded theory analysis are supplemented with a visual representation of major constructs usually in the form of flow charts or framework diagrams. Quotations from the participants are used in a supportive capacity to substantiate the findings. Strauss and Corbin highlights that “the value of the grounded theory lies not only in its ability to generate a theory but also to ground that theory in the data.”[ 27 ]

Example: Williams et al . conducted a grounded theory research to explore the nature of relationship between the sense of self and the eating disorders. Data were collected form 11 women with a lifetime history of Anorexia Nervosa and were analyzed using the grounded theory methodology. Analysis led to the development of a theoretical framework on the nature of the relationship between the self and Anorexia Nervosa. [ 29 ]

Ethnographic research

Ethnography has its base in anthropology, where the anthropologists used it for understanding the culture-specific knowledge and behaviors. In health sciences research, ethnography focuses on narrating and interpreting the health behaviors of a culture-sharing group. 'Culture-sharing group' in an ethnography represents any 'group of people who share common meanings, customs or experiences.' In health research, it could be a group of physicians working in rural care, a group of medical students, or it could be a group of patients who receive home-based rehabilitation. To understand the cultural patterns, researchers primarily observe the individuals or group of individuals for a prolonged period of time.[ 1 , 7 , 30 ] The scope of ethnography can be broad or narrow depending on the aim. The study of more general cultural groups is termed as macro-ethnography, whereas micro-ethnography focuses on more narrowly defined cultures. Ethnography is usually conducted in a single setting. Ethnographers collect data using a variety of methods such as observation, interviews, audio-video records, and document reviews. A written report includes a detailed description of the culture sharing group with emic and etic perspectives. When the researcher reports the views of the participants it is called emic perspectives and when the researcher reports his or her views about the culture, the term is called etic.[ 7 ]

Example: The aim of the ethnographic study by LeBaron et al . was to explore the barriers to opioid availability and cancer pain management in India. The researchers collected data from fifty-nine participants using in-depth semi-structured interviews, participant observation, and document review. The researchers identified significant barriers by open coding and thematic analysis of the formal interview. [ 31 ]

Historical research

Historical research is the “systematic collection, critical evaluation, and interpretation of historical evidence”.[ 1 ] The purpose of historical research is to gain insights from the past and involves interpreting past events in the light of the present. The data for historical research are usually collected from primary and secondary sources. The primary source mainly includes diaries, first hand information, and writings. The secondary sources are textbooks, newspapers, second or third-hand accounts of historical events and medical/legal documents. The data gathered from these various sources are synthesized and reported as biographical narratives or developmental perspectives in chronological order. The ideas are interpreted in terms of the historical context and significance. The written report describes 'what happened', 'how it happened', 'why it happened', and its significance and implications to current clinical practice.[ 1 , 10 ]

Example: Lubold (2019) analyzed the breastfeeding trends in three countries (Sweden, Ireland, and the United States) using a historical qualitative method. Through analysis of historical data, the researcher found that strong family policies, adherence to international recommendations and adoption of baby-friendly hospital initiative could greatly enhance the breastfeeding rates. [ 32 ]

Case study research

Case study research focuses on the description and in-depth analysis of the case(s) or issues illustrated by the case(s). The design has its origin from psychology, law, and medicine. Case studies are best suited for the understanding of case(s), thus reducing the unit of analysis into studying an event, a program, an activity or an illness. Observations, one to one interviews, artifacts, and documents are used for collecting the data, and the analysis is done through the description of the case. From this, themes and cross-case themes are derived. A written case study report includes a detailed description of one or more cases.[ 7 , 10 ]

Example: Perceptions of poststroke sexuality in a woman of childbearing age was explored using a qualitative case study approach by Beal and Millenbrunch. Semi structured interview was conducted with a 36- year mother of two children with a history of Acute ischemic stroke. The data were analyzed using an inductive approach. The authors concluded that “stroke during childbearing years may affect a woman's perception of herself as a sexual being and her ability to carry out gender roles”. [ 33 ]

Sampling in Qualitative Research

Qualitative researchers widely use non-probability sampling techniques such as purposive sampling, convenience sampling, quota sampling, snowball sampling, homogeneous sampling, maximum variation sampling, extreme (deviant) case sampling, typical case sampling, and intensity sampling. The selection of a sampling technique depends on the nature and needs of the study.[ 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 ] The four widely used sampling techniques are convenience sampling, purposive sampling, snowball sampling, and intensity sampling.

Convenience sampling

It is otherwise called accidental sampling, where the researchers collect data from the subjects who are selected based on accessibility, geographical proximity, ease, speed, and or low cost.[ 34 ] Convenience sampling offers a significant benefit of convenience but often accompanies the issues of sample representation.

Purposive sampling

Purposive or purposeful sampling is a widely used sampling technique.[ 35 ] It involves identifying a population based on already established sampling criteria and then selecting subjects who fulfill that criteria to increase the credibility. However, choosing information-rich cases is the key to determine the power and logic of purposive sampling in a qualitative study.[ 1 ]

Snowball sampling

The method is also known as 'chain referral sampling' or 'network sampling.' The sampling starts by having a few initial participants, and the researcher relies on these early participants to identify additional study participants. It is best adopted when the researcher wishes to study the stigmatized group, or in cases, where findings of participants are likely to be difficult by ordinary means. Respondent ridden sampling is an improvised version of snowball sampling used to find out the participant from a hard-to-find or hard-to-study population.[ 37 , 38 ]

Intensity sampling

The process of identifying information-rich cases that manifest the phenomenon of interest is referred to as intensity sampling. It requires prior information, and considerable judgment about the phenomenon of interest and the researcher should do some preliminary investigations to determine the nature of the variation. Intensity sampling will be done once the researcher identifies the variation across the cases (extreme, average and intense) and picks the intense cases from them.[ 40 ]

Deciding the Sample Size

A-priori sample size calculation is not undertaken in the case of qualitative research. Researchers collect the data from as many participants as possible until they reach the point of data saturation. Data saturation or the point of redundancy is the stage where the researcher no longer sees or hears any new information. Data saturation gives the idea that the researcher has captured all possible information about the phenomenon of interest. Since no further information is being uncovered as redundancy is achieved, at this point the data collection can be stopped. The objective here is to get an overall picture of the chronicle of the phenomenon under the study rather than generalization.[ 1 , 7 , 41 ]

Data Collection in Qualitative Research

The various strategies used for data collection in qualitative research includes in-depth interviews (individual or group), focus group discussions (FGDs), participant observation, narrative life history, document analysis, audio materials, videos or video footage, text analysis, and simple observation. Among all these, the three popular methods are the FGDs, one to one in-depth interviews and the participant observation.

FGDs are useful in eliciting data from a group of individuals. They are normally built around a specific topic and are considered as the best approach to gather data on an entire range of responses to a topic.[ 42 Group size in an FGD ranges from 6 to 12. Depending upon the nature of participants, FGDs could be homogeneous or heterogeneous.[ 1 , 14 ] One to one in-depth interviews are best suited to obtain individuals' life histories, lived experiences, perceptions, and views, particularly while exporting topics of sensitive nature. In-depth interviews can be structured, unstructured, or semi-structured. However, semi-structured interviews are widely used in qualitative research. Participant observations are suitable for gathering data regarding naturally occurring behaviors.[ 1 ]

Data Analysis in Qualitative Research

Various strategies are employed by researchers to analyze data in qualitative research. Data analytic strategies differ according to the type of inquiry. A general content analysis approach is described herewith. Data analysis begins by transcription of the interview data. The researcher carefully reads data and gets a sense of the whole. Once the researcher is familiarized with the data, the researcher strives to identify small meaning units called the 'codes.' The codes are then grouped based on their shared concepts to form the primary categories. Based on the relationship between the primary categories, they are then clustered into secondary categories. The next step involves the identification of themes and interpretation to make meaning out of data. In the results section of the manuscript, the researcher describes the key findings/themes that emerged. The themes can be supported by participants' quotes. The analytical framework used should be explained in sufficient detail, and the analytic framework must be well referenced. The study findings are usually represented in a schematic form for better conceptualization.[ 1 , 7 ] Even though the overall analytical process remains the same across different qualitative designs, each design such as phenomenology, ethnography, and grounded theory has design specific analytical procedures, the details of which are out of the scope of this article.

Computer-Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software (CAQDAS)

Until recently, qualitative analysis was done either manually or with the help of a spreadsheet application. Currently, there are various software programs available which aid researchers to manage qualitative data. CAQDAS is basically data management tools and cannot analyze the qualitative data as it lacks the ability to think, reflect, and conceptualize. Nonetheless, CAQDAS helps researchers to manage, shape, and make sense of unstructured information. Open Code, MAXQDA, NVivo, Atlas.ti, and Hyper Research are some of the widely used qualitative data analysis software.[ 14 , 43 ]

Reporting Guidelines

Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) is the widely used reporting guideline for qualitative research. This 32-item checklist assists researchers in reporting all the major aspects related to the study. The three major domains of COREQ are the 'research team and reflexivity', 'study design', and 'analysis and findings'.[ 44 , 45 ]

Critical Appraisal of Qualitative Research

Various scales are available to critical appraisal of qualitative research. The widely used one is the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) Qualitative Checklist developed by CASP network, UK. This 10-item checklist evaluates the quality of the study under areas such as aims, methodology, research design, ethical considerations, data collection, data analysis, and findings.[ 46 ]

Ethical Issues in Qualitative Research

A qualitative study must be undertaken by grounding it in the principles of bioethics such as beneficence, non-maleficence, autonomy, and justice. Protecting the participants is of utmost importance, and the greatest care has to be taken while collecting data from a vulnerable research population. The researcher must respect individuals, families, and communities and must make sure that the participants are not identifiable by their quotations that the researchers include when publishing the data. Consent for audio/video recordings must be obtained. Approval to be in FGDs must be obtained from the participants. Researchers must ensure the confidentiality and anonymity of the transcripts/audio-video records/photographs/other data collected as a part of the study. The researchers must confirm their role as advocates and proceed in the best interest of all participants.[ 42 , 47 , 48 ]

Rigor in Qualitative Research

The demonstration of rigor or quality in the conduct of the study is essential for every research method. However, the criteria used to evaluate the rigor of quantitative studies are not be appropriate for qualitative methods. Lincoln and Guba (1985) first outlined the criteria for evaluating the qualitative research often referred to as “standards of trustworthiness of qualitative research”.[ 49 ] The four components of the criteria are credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability.

Credibility refers to confidence in the 'truth value' of the data and its interpretation. It is used to establish that the findings are true, credible and believable. Credibility is similar to the internal validity in quantitative research.[ 1 , 50 , 51 ] The second criterion to establish the trustworthiness of the qualitative research is transferability, Transferability refers to the degree to which the qualitative results are applicability to other settings, population or contexts. This is analogous to the external validity in quantitative research.[ 1 , 50 , 51 ] Lincoln and Guba recommend authors provide enough details so that the users will be able to evaluate the applicability of data in other contexts.[ 49 ] The criterion of dependability refers to the assumption of repeatability or replicability of the study findings and is similar to that of reliability in quantitative research. The dependability question is 'Whether the study findings be repeated of the study is replicated with the same (similar) cohort of participants, data coders, and context?'[ 1 , 50 , 51 ] Confirmability, the fourth criteria is analogous to the objectivity of the study and refers the degree to which the study findings could be confirmed or corroborated by others. To ensure confirmability the data should directly reflect the participants' experiences and not the bias, motivations, or imaginations of the inquirer.[ 1 , 50 , 51 ] Qualitative researchers should ensure that the study is conducted with enough rigor and should report the measures undertaken to enhance the trustworthiness of the study.

Conclusions

Qualitative research studies are being widely acknowledged and recognized in health care practice. This overview illustrates various qualitative methods and shows how these methods can be used to generate evidence that informs clinical practice. Qualitative research helps to understand the patterns of health behaviors, describe illness experiences, design health interventions, and develop healthcare theories. The ultimate strength of the qualitative research approach lies in the richness of the data and the descriptions and depth of exploration it makes. Hence, qualitative methods are considered as the most humanistic and person-centered way of discovering and uncovering thoughts and actions of human beings.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

Qualitative Research : Definition

Qualitative research is the naturalistic study of social meanings and processes, using interviews, observations, and the analysis of texts and images. In contrast to quantitative researchers, whose statistical methods enable broad generalizations about populations (for example, comparisons of the percentages of U.S. demographic groups who vote in particular ways), qualitative researchers use in-depth studies of the social world to analyze how and why groups think and act in particular ways (for instance, case studies of the experiences that shape political views).

Events and Workshops

- Introduction to NVivo Have you just collected your data and wondered what to do next? Come join us for an introductory session on utilizing NVivo to support your analytical process. This session will only cover features of the software and how to import your records. Please feel free to attend any of the following sessions below: April 25th, 2024 12:30 pm - 1:45 pm Green Library - SVA Conference Room 125 May 9th, 2024 12:30 pm - 1:45 pm Green Library - SVA Conference Room 125

- Next: Choose an approach >>

- Choose an approach

- Find studies

- Learn methods

- Getting Started

- Get software

- Get data for secondary analysis

- Network with researchers

- Last Updated: May 23, 2024 1:27 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.stanford.edu/qualitative_research

Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review

- Regular Article

- Open access

- Published: 18 September 2021

- Volume 31 , pages 679–689, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Drishti Yadav ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2974-0323 1

86k Accesses

32 Citations

72 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This review aims to synthesize a published set of evaluative criteria for good qualitative research. The aim is to shed light on existing standards for assessing the rigor of qualitative research encompassing a range of epistemological and ontological standpoints. Using a systematic search strategy, published journal articles that deliberate criteria for rigorous research were identified. Then, references of relevant articles were surveyed to find noteworthy, distinct, and well-defined pointers to good qualitative research. This review presents an investigative assessment of the pivotal features in qualitative research that can permit the readers to pass judgment on its quality and to condemn it as good research when objectively and adequately utilized. Overall, this review underlines the crux of qualitative research and accentuates the necessity to evaluate such research by the very tenets of its being. It also offers some prospects and recommendations to improve the quality of qualitative research. Based on the findings of this review, it is concluded that quality criteria are the aftereffect of socio-institutional procedures and existing paradigmatic conducts. Owing to the paradigmatic diversity of qualitative research, a single and specific set of quality criteria is neither feasible nor anticipated. Since qualitative research is not a cohesive discipline, researchers need to educate and familiarize themselves with applicable norms and decisive factors to evaluate qualitative research from within its theoretical and methodological framework of origin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Good Qualitative Research: Opening up the Debate

Beyond qualitative/quantitative structuralism: the positivist qualitative research and the paradigmatic disclaimer.

What is Qualitative in Research

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“… It is important to regularly dialogue about what makes for good qualitative research” (Tracy, 2010 , p. 837)

To decide what represents good qualitative research is highly debatable. There are numerous methods that are contained within qualitative research and that are established on diverse philosophical perspectives. Bryman et al., ( 2008 , p. 262) suggest that “It is widely assumed that whereas quality criteria for quantitative research are well‐known and widely agreed, this is not the case for qualitative research.” Hence, the question “how to evaluate the quality of qualitative research” has been continuously debated. There are many areas of science and technology wherein these debates on the assessment of qualitative research have taken place. Examples include various areas of psychology: general psychology (Madill et al., 2000 ); counseling psychology (Morrow, 2005 ); and clinical psychology (Barker & Pistrang, 2005 ), and other disciplines of social sciences: social policy (Bryman et al., 2008 ); health research (Sparkes, 2001 ); business and management research (Johnson et al., 2006 ); information systems (Klein & Myers, 1999 ); and environmental studies (Reid & Gough, 2000 ). In the literature, these debates are enthused by the impression that the blanket application of criteria for good qualitative research developed around the positivist paradigm is improper. Such debates are based on the wide range of philosophical backgrounds within which qualitative research is conducted (e.g., Sandberg, 2000 ; Schwandt, 1996 ). The existence of methodological diversity led to the formulation of different sets of criteria applicable to qualitative research.

Among qualitative researchers, the dilemma of governing the measures to assess the quality of research is not a new phenomenon, especially when the virtuous triad of objectivity, reliability, and validity (Spencer et al., 2004 ) are not adequate. Occasionally, the criteria of quantitative research are used to evaluate qualitative research (Cohen & Crabtree, 2008 ; Lather, 2004 ). Indeed, Howe ( 2004 ) claims that the prevailing paradigm in educational research is scientifically based experimental research. Hypotheses and conjectures about the preeminence of quantitative research can weaken the worth and usefulness of qualitative research by neglecting the prominence of harmonizing match for purpose on research paradigm, the epistemological stance of the researcher, and the choice of methodology. Researchers have been reprimanded concerning this in “paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences” (Lincoln & Guba, 2000 ).

In general, qualitative research tends to come from a very different paradigmatic stance and intrinsically demands distinctive and out-of-the-ordinary criteria for evaluating good research and varieties of research contributions that can be made. This review attempts to present a series of evaluative criteria for qualitative researchers, arguing that their choice of criteria needs to be compatible with the unique nature of the research in question (its methodology, aims, and assumptions). This review aims to assist researchers in identifying some of the indispensable features or markers of high-quality qualitative research. In a nutshell, the purpose of this systematic literature review is to analyze the existing knowledge on high-quality qualitative research and to verify the existence of research studies dealing with the critical assessment of qualitative research based on the concept of diverse paradigmatic stances. Contrary to the existing reviews, this review also suggests some critical directions to follow to improve the quality of qualitative research in different epistemological and ontological perspectives. This review is also intended to provide guidelines for the acceleration of future developments and dialogues among qualitative researchers in the context of assessing the qualitative research.

The rest of this review article is structured in the following fashion: Sect. Methods describes the method followed for performing this review. Section Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies provides a comprehensive description of the criteria for evaluating qualitative studies. This section is followed by a summary of the strategies to improve the quality of qualitative research in Sect. Improving Quality: Strategies . Section How to Assess the Quality of the Research Findings? provides details on how to assess the quality of the research findings. After that, some of the quality checklists (as tools to evaluate quality) are discussed in Sect. Quality Checklists: Tools for Assessing the Quality . At last, the review ends with the concluding remarks presented in Sect. Conclusions, Future Directions and Outlook . Some prospects in qualitative research for enhancing its quality and usefulness in the social and techno-scientific research community are also presented in Sect. Conclusions, Future Directions and Outlook .

For this review, a comprehensive literature search was performed from many databases using generic search terms such as Qualitative Research , Criteria , etc . The following databases were chosen for the literature search based on the high number of results: IEEE Explore, ScienceDirect, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science. The following keywords (and their combinations using Boolean connectives OR/AND) were adopted for the literature search: qualitative research, criteria, quality, assessment, and validity. The synonyms for these keywords were collected and arranged in a logical structure (see Table 1 ). All publications in journals and conference proceedings later than 1950 till 2021 were considered for the search. Other articles extracted from the references of the papers identified in the electronic search were also included. A large number of publications on qualitative research were retrieved during the initial screening. Hence, to include the searches with the main focus on criteria for good qualitative research, an inclusion criterion was utilized in the search string.

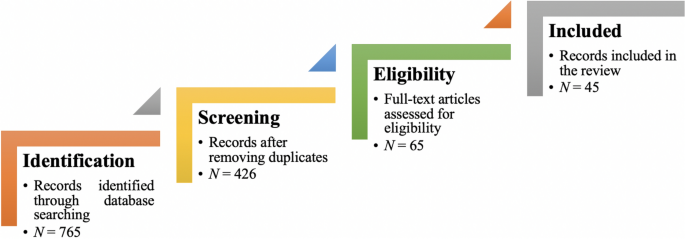

From the selected databases, the search retrieved a total of 765 publications. Then, the duplicate records were removed. After that, based on the title and abstract, the remaining 426 publications were screened for their relevance by using the following inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Table 2 ). Publications focusing on evaluation criteria for good qualitative research were included, whereas those works which delivered theoretical concepts on qualitative research were excluded. Based on the screening and eligibility, 45 research articles were identified that offered explicit criteria for evaluating the quality of qualitative research and were found to be relevant to this review.

Figure 1 illustrates the complete review process in the form of PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, i.e., “preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses” is employed in systematic reviews to refine the quality of reporting.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the search and inclusion process. N represents the number of records

Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies

Fundamental criteria: general research quality.

Various researchers have put forward criteria for evaluating qualitative research, which have been summarized in Table 3 . Also, the criteria outlined in Table 4 effectively deliver the various approaches to evaluate and assess the quality of qualitative work. The entries in Table 4 are based on Tracy’s “Eight big‐tent criteria for excellent qualitative research” (Tracy, 2010 ). Tracy argues that high-quality qualitative work should formulate criteria focusing on the worthiness, relevance, timeliness, significance, morality, and practicality of the research topic, and the ethical stance of the research itself. Researchers have also suggested a series of questions as guiding principles to assess the quality of a qualitative study (Mays & Pope, 2020 ). Nassaji ( 2020 ) argues that good qualitative research should be robust, well informed, and thoroughly documented.

Qualitative Research: Interpretive Paradigms

All qualitative researchers follow highly abstract principles which bring together beliefs about ontology, epistemology, and methodology. These beliefs govern how the researcher perceives and acts. The net, which encompasses the researcher’s epistemological, ontological, and methodological premises, is referred to as a paradigm, or an interpretive structure, a “Basic set of beliefs that guides action” (Guba, 1990 ). Four major interpretive paradigms structure the qualitative research: positivist and postpositivist, constructivist interpretive, critical (Marxist, emancipatory), and feminist poststructural. The complexity of these four abstract paradigms increases at the level of concrete, specific interpretive communities. Table 5 presents these paradigms and their assumptions, including their criteria for evaluating research, and the typical form that an interpretive or theoretical statement assumes in each paradigm. Moreover, for evaluating qualitative research, quantitative conceptualizations of reliability and validity are proven to be incompatible (Horsburgh, 2003 ). In addition, a series of questions have been put forward in the literature to assist a reviewer (who is proficient in qualitative methods) for meticulous assessment and endorsement of qualitative research (Morse, 2003 ). Hammersley ( 2007 ) also suggests that guiding principles for qualitative research are advantageous, but methodological pluralism should not be simply acknowledged for all qualitative approaches. Seale ( 1999 ) also points out the significance of methodological cognizance in research studies.

Table 5 reflects that criteria for assessing the quality of qualitative research are the aftermath of socio-institutional practices and existing paradigmatic standpoints. Owing to the paradigmatic diversity of qualitative research, a single set of quality criteria is neither possible nor desirable. Hence, the researchers must be reflexive about the criteria they use in the various roles they play within their research community.

Improving Quality: Strategies

Another critical question is “How can the qualitative researchers ensure that the abovementioned quality criteria can be met?” Lincoln and Guba ( 1986 ) delineated several strategies to intensify each criteria of trustworthiness. Other researchers (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016 ; Shenton, 2004 ) also presented such strategies. A brief description of these strategies is shown in Table 6 .

It is worth mentioning that generalizability is also an integral part of qualitative research (Hays & McKibben, 2021 ). In general, the guiding principle pertaining to generalizability speaks about inducing and comprehending knowledge to synthesize interpretive components of an underlying context. Table 7 summarizes the main metasynthesis steps required to ascertain generalizability in qualitative research.

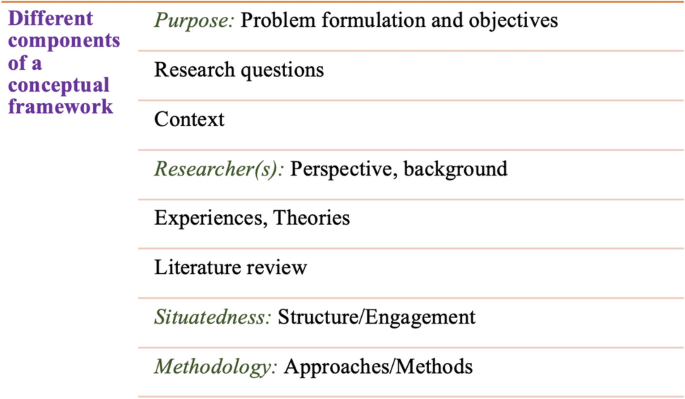

Figure 2 reflects the crucial components of a conceptual framework and their contribution to decisions regarding research design, implementation, and applications of results to future thinking, study, and practice (Johnson et al., 2020 ). The synergy and interrelationship of these components signifies their role to different stances of a qualitative research study.

Essential elements of a conceptual framework

In a nutshell, to assess the rationale of a study, its conceptual framework and research question(s), quality criteria must take account of the following: lucid context for the problem statement in the introduction; well-articulated research problems and questions; precise conceptual framework; distinct research purpose; and clear presentation and investigation of the paradigms. These criteria would expedite the quality of qualitative research.

How to Assess the Quality of the Research Findings?

The inclusion of quotes or similar research data enhances the confirmability in the write-up of the findings. The use of expressions (for instance, “80% of all respondents agreed that” or “only one of the interviewees mentioned that”) may also quantify qualitative findings (Stenfors et al., 2020 ). On the other hand, the persuasive reason for “why this may not help in intensifying the research” has also been provided (Monrouxe & Rees, 2020 ). Further, the Discussion and Conclusion sections of an article also prove robust markers of high-quality qualitative research, as elucidated in Table 8 .

Quality Checklists: Tools for Assessing the Quality

Numerous checklists are available to speed up the assessment of the quality of qualitative research. However, if used uncritically and recklessly concerning the research context, these checklists may be counterproductive. I recommend that such lists and guiding principles may assist in pinpointing the markers of high-quality qualitative research. However, considering enormous variations in the authors’ theoretical and philosophical contexts, I would emphasize that high dependability on such checklists may say little about whether the findings can be applied in your setting. A combination of such checklists might be appropriate for novice researchers. Some of these checklists are listed below:

The most commonly used framework is Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) (Tong et al., 2007 ). This framework is recommended by some journals to be followed by the authors during article submission.

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) is another checklist that has been created particularly for medical education (O’Brien et al., 2014 ).

Also, Tracy ( 2010 ) and Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP, 2021 ) offer criteria for qualitative research relevant across methods and approaches.

Further, researchers have also outlined different criteria as hallmarks of high-quality qualitative research. For instance, the “Road Trip Checklist” (Epp & Otnes, 2021 ) provides a quick reference to specific questions to address different elements of high-quality qualitative research.

Conclusions, Future Directions, and Outlook

This work presents a broad review of the criteria for good qualitative research. In addition, this article presents an exploratory analysis of the essential elements in qualitative research that can enable the readers of qualitative work to judge it as good research when objectively and adequately utilized. In this review, some of the essential markers that indicate high-quality qualitative research have been highlighted. I scope them narrowly to achieve rigor in qualitative research and note that they do not completely cover the broader considerations necessary for high-quality research. This review points out that a universal and versatile one-size-fits-all guideline for evaluating the quality of qualitative research does not exist. In other words, this review also emphasizes the non-existence of a set of common guidelines among qualitative researchers. In unison, this review reinforces that each qualitative approach should be treated uniquely on account of its own distinctive features for different epistemological and disciplinary positions. Owing to the sensitivity of the worth of qualitative research towards the specific context and the type of paradigmatic stance, researchers should themselves analyze what approaches can be and must be tailored to ensemble the distinct characteristics of the phenomenon under investigation. Although this article does not assert to put forward a magic bullet and to provide a one-stop solution for dealing with dilemmas about how, why, or whether to evaluate the “goodness” of qualitative research, it offers a platform to assist the researchers in improving their qualitative studies. This work provides an assembly of concerns to reflect on, a series of questions to ask, and multiple sets of criteria to look at, when attempting to determine the quality of qualitative research. Overall, this review underlines the crux of qualitative research and accentuates the need to evaluate such research by the very tenets of its being. Bringing together the vital arguments and delineating the requirements that good qualitative research should satisfy, this review strives to equip the researchers as well as reviewers to make well-versed judgment about the worth and significance of the qualitative research under scrutiny. In a nutshell, a comprehensive portrayal of the research process (from the context of research to the research objectives, research questions and design, speculative foundations, and from approaches of collecting data to analyzing the results, to deriving inferences) frequently proliferates the quality of a qualitative research.

Prospects : A Road Ahead for Qualitative Research

Irrefutably, qualitative research is a vivacious and evolving discipline wherein different epistemological and disciplinary positions have their own characteristics and importance. In addition, not surprisingly, owing to the sprouting and varied features of qualitative research, no consensus has been pulled off till date. Researchers have reflected various concerns and proposed several recommendations for editors and reviewers on conducting reviews of critical qualitative research (Levitt et al., 2021 ; McGinley et al., 2021 ). Following are some prospects and a few recommendations put forward towards the maturation of qualitative research and its quality evaluation:

In general, most of the manuscript and grant reviewers are not qualitative experts. Hence, it is more likely that they would prefer to adopt a broad set of criteria. However, researchers and reviewers need to keep in mind that it is inappropriate to utilize the same approaches and conducts among all qualitative research. Therefore, future work needs to focus on educating researchers and reviewers about the criteria to evaluate qualitative research from within the suitable theoretical and methodological context.

There is an urgent need to refurbish and augment critical assessment of some well-known and widely accepted tools (including checklists such as COREQ, SRQR) to interrogate their applicability on different aspects (along with their epistemological ramifications).

Efforts should be made towards creating more space for creativity, experimentation, and a dialogue between the diverse traditions of qualitative research. This would potentially help to avoid the enforcement of one's own set of quality criteria on the work carried out by others.

Moreover, journal reviewers need to be aware of various methodological practices and philosophical debates.

It is pivotal to highlight the expressions and considerations of qualitative researchers and bring them into a more open and transparent dialogue about assessing qualitative research in techno-scientific, academic, sociocultural, and political rooms.

Frequent debates on the use of evaluative criteria are required to solve some potentially resolved issues (including the applicability of a single set of criteria in multi-disciplinary aspects). Such debates would not only benefit the group of qualitative researchers themselves, but primarily assist in augmenting the well-being and vivacity of the entire discipline.

To conclude, I speculate that the criteria, and my perspective, may transfer to other methods, approaches, and contexts. I hope that they spark dialog and debate – about criteria for excellent qualitative research and the underpinnings of the discipline more broadly – and, therefore, help improve the quality of a qualitative study. Further, I anticipate that this review will assist the researchers to contemplate on the quality of their own research, to substantiate research design and help the reviewers to review qualitative research for journals. On a final note, I pinpoint the need to formulate a framework (encompassing the prerequisites of a qualitative study) by the cohesive efforts of qualitative researchers of different disciplines with different theoretic-paradigmatic origins. I believe that tailoring such a framework (of guiding principles) paves the way for qualitative researchers to consolidate the status of qualitative research in the wide-ranging open science debate. Dialogue on this issue across different approaches is crucial for the impending prospects of socio-techno-educational research.

Amin, M. E. K., Nørgaard, L. S., Cavaco, A. M., Witry, M. J., Hillman, L., Cernasev, A., & Desselle, S. P. (2020). Establishing trustworthiness and authenticity in qualitative pharmacy research. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 16 (10), 1472–1482.

Article Google Scholar

Barker, C., & Pistrang, N. (2005). Quality criteria under methodological pluralism: Implications for conducting and evaluating research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 35 (3–4), 201–212.

Bryman, A., Becker, S., & Sempik, J. (2008). Quality criteria for quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods research: A view from social policy. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11 (4), 261–276.

Caelli, K., Ray, L., & Mill, J. (2003). ‘Clear as mud’: Toward greater clarity in generic qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2 (2), 1–13.

CASP (2021). CASP checklists. Retrieved May 2021 from https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

Cohen, D. J., & Crabtree, B. F. (2008). Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: Controversies and recommendations. The Annals of Family Medicine, 6 (4), 331–339.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 1–32). Sage Publications Ltd.

Google Scholar

Elliott, R., Fischer, C. T., & Rennie, D. L. (1999). Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38 (3), 215–229.

Epp, A. M., & Otnes, C. C. (2021). High-quality qualitative research: Getting into gear. Journal of Service Research . https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670520961445

Guba, E. G. (1990). The paradigm dialog. In Alternative paradigms conference, mar, 1989, Indiana u, school of education, San Francisco, ca, us . Sage Publications, Inc.