Joan of Arc

Martyr, saint and military leader Joan of Arc, acting under divine guidance, led the French army to victory over the English during the Hundred Years' War.

(1412-1431)

Who Was Joan of Arc?

A national heroine of France, at age 18 Joan of Arc led the French army to victory over the English at Orléans. Captured a year later, Joan was burned at the stake as a heretic by the English and their French collaborators. She was canonized as a Roman Catholic saint more than 500 years later, on May 16, 1920.

Historical Background

Joan of Arc, nicknamed "The Maid of Orléans," was born in 1412, in Domremy, France. The daughter of poor tenant farmers Jacques d’ Arc and his wife, Isabelle, also known as Romée, Joan learned piety and domestic skills from her mother. Never venturing far from home, Joan took care of the animals and became quite skilled as a seamstress.

In 1415, King Henry V of England invaded northern France. After delivering a shattering defeat to French forces, England gained the support of the Burgundians in France. The 1420 Treaty of Troyes, granted the French throne to Henry V as regent for the insane King Charles VI. Henry would then inherit the throne after Charles’s death. However, in 1422, both Henry and Charles died within a couple of months, leaving Henry’s infant son as king of both realms. The French supporters of Charles’ son, the future Charles VII, sensed an opportunity to return the crown to a French monarch.

Around this time, Joan of Arc began to have mystical visions encouraging her to lead a pious life. Over time, they became more vivid, with the presence of St. Michael and St. Catherine designating her as the savior of France and encouraging her to seek an audience with Charles—who had assumed the title Dauphin (heir to the throne)—and ask his permission to expel the English and install him as the rightful king.

Meeting with the Dauphin

In May 1428, Joan’s visions instructed her to go to Vaucouleurs and contact Robert de Baudricourt, the garrison commander and a supporter of Charles. At first, Baudricourt refused Joan’s request, but after seeing that she was gaining the approval of villagers, in 1429 he relented and gave her a horse and an escort of several soldiers. Joan cropped her hair and dressed in men’s clothes for her 11-day journey across enemy territory to Chinon, the site of Charles’s court.

At first, Charles was not certain what to make of this peasant girl who asked for an audience and professed she could save France. Joan, however, won him over when she correctly identified him, dressed incognito, in a crowd of members of his court. The two had a private conversation during which it is said Joan revealed details of a solemn prayer Charles had made to God to save France. Still tentative, Charles had prominent theologians examine her. The clergymen reported they found nothing improper with Joan, only piety, chastity and humility.

The Battle of Orléans

Finally, Charles gave the 17-year-old Joan of Arc armor and a horse and allowed her to accompany the army to Orléans, the site of an English siege. In a series of battles between May 4 and May 7, 1429, the French troops took control of the English fortifications. Joan was wounded but later returned to the front to encourage a final assault. By mid-June, the French had routed the English and, in doing so, their perceived invincibility as well.

Although it appeared that Charles had accepted Joan’s mission, he did not display full trust in her judgment or advice. After the victory at Orléans, she kept encouraging him to hurry to Reims to be crowned king, but he and his advisors were more cautious. However, Charles and his procession finally entered Reims, and he was crowned Charles VII on July 18, 1429. Joan was at his side, occupying a visible place at the ceremonies.

Capture and Trial

In the spring of 1430, King Charles VII ordered Joan to Compiègne to confront the Burgundian assault. During the battle, she was thrown off her horse and left outside the town’s gates. The Burgundians took her captive and held her for several months, negotiating with the English, who saw her as a valuable propaganda prize. Finally, the Burgundians exchanged Joan for 10,000 francs.

Charles VII was unsure what to do. Still not convinced of Joan’s divine inspiration, he distanced himself and made no attempt to have her released. Though Joan’s actions were against the English occupation army, she was turned over to church officials who insisted she be tried as a heretic. She was charged with 70 counts, including witchcraft, heresy and dressing like a man.

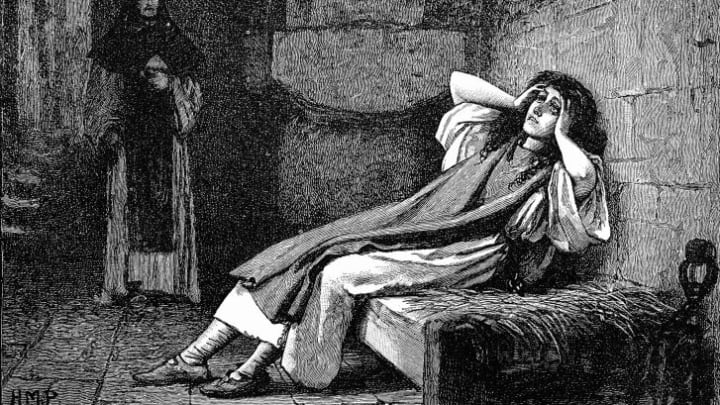

Initially, the trial was held in public, but it went private when Joan bettered her accusers. Between February 21 and March 24, 1431, she was interrogated nearly a dozen times by a tribunal, always keeping her humility and steadfast claim of innocence. Instead of being held in a church prison with nuns as guards, she was held in a military prison. Joan was threatened with rape and torture, though there is no record that either actually occurred. She protected herself by tying her soldiers’ clothes tightly together with dozens of cords. Frustrated they could not break her, the tribunal eventually used her military clothes against her, charging that she dressed like a man.

On May 29, 1431, the tribunal announced Joan of Arc was guilty of heresy. On the morning of May 30, she was taken to the marketplace in Rouen and burned at the stake, before an estimated crowd of 10,000 people. She was 19 years old. One legend surrounding the event tells of how her heart survived the fire unaffected. Her ashes were gathered and scattered in the Seine.

Retrial and Legacy

After Joan's death, the Hundred Years’ War continued for another 22 years. King Charles VII ultimately retained his crown, and he ordered an investigation that in 1456 declared Joan of Arc to be officially innocent of all charges and designated a martyr. She was canonized as a saint on May 16, 1920, and is the patron saint of France.

Watch "Joan of Arc: The Virgin Warrior" on HISTORY Vault

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Joan of Arc

- Birth Year: 1412

- Birth City: Domremy

- Birth Country: France

- Gender: Female

- Best Known For: Martyr, saint and military leader Joan of Arc, acting under divine guidance, led the French army to victory over the English during the Hundred Years' War.

- Nacionalities

- Death Year: 1431

- Death date: May 30, 1431

- Death City: Rouen

- Death Country: France

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Joan of Arc Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/military-figure/joan-of-arc

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: May 6, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

Famous Military Figures

‘Masters of the Air:’ The Real 100th Bomb Group

The 13 Most Cunning Military Leaders

11 Famous People Who Served on D-Day

Who Are the Rival Generals in the Sudan Conflict?

Tuskegee Airman Clarence D. Lester Broke Barriers

Biography: You Need to Know: Rick Thornton

Pancho Villa

Stonewall Jackson

George Rogers Clark

King Arthur

Scipio Africanus

Biography of Joan of Arc, Visionary, Saint, and Military Leader

Jeanne D'Arc was 16 when she led France to victory

Thierry PRAT / Getty Images

- Beliefs and Teachings

- Holy Days and Holidays

- Christianity Origins

- The New Testament

- The Old Testament

- Practical Tools for Christians

- Christian Life For Teens

- Christian Prayers

- Inspirational Bible Devotions

- Denominations of Christianity

- Christian Holidays

- Christian Entertainment

- Key Terms in Christianity

- Latter Day Saints

- M.Div., Harvard University

- B.A., Literature, History, and Philosophy, Wesleyan University

Jeanne D'Arc (c. 1412–May 30, 1431), known in English as Joan of Arc, was a French peasant girl whose visions of angels led her to become a military leader. Joan of Arc's intervention changed the outcome of the Hundred Years War and helped ensure that Charles VII of France would become king. Joan was, finally, executed by the English forces whom she defeated.

Throughout her young life, from age 13, Joan believed that she was visited by various angels and given clear direction to take action for France; various theories have been suggested that may explain the origins of her visions. In May 1920, Joan of Arc was canonized as a saint in the Roman Catholic Church.

Fast Facts: Joan of Arc

- Also Known As : Jeanne D'Arc, The Maid of Orléans, Saint Joan

- Known For : A visionary whose actions turned the tide of the Hundred Years War

- Born : 1412 in Domremy, Kingdom of France

- Died : May 30, 1431 in Rouen, Normandy

- Parents : Jacques d'Arc and Isabelle Romée

- Notable Quote : "One life is all we have and we live it as we believe in living it. But to sacrifice what you are and to live without belief, that is a fate more terrible than dying."

Joan was born in the village of Domremy, which at the time was part of the Duchy of Bar within the Holy Roman Empire. Her parents, Isabelle Romee and Jacques d’Arc, were peasants with a small farm; her father also worked as a village official. Joan had two older brothers as well as a younger brother and sister. As a peasant girl during the Middle Ages, Joan was not taught to read or write, but she was brought up in the Catholic Church.

Joan of Arc was born during the middle of the Hundred Years War, a battle over who should inherit the French throne. At the time of her birth, the English were in the ascendancy; France had declined as a result of the Black Plague and other challenges. While Domremy, where Joan lived, was not a major focus of the war, it was located in a portion of France that had remained loyal to the French crown. Joan was well aware of the fighting. In fact, Domremy had actually been burnt more than once by English loyalists.

Joan's Visions

At the age of 13, Joan began to claim that she heard the voices of angels and saw visions of St. Michael , St. Catherine of Alexandria, and St. Margaret of Antioch. While some modern researchers suggest that these visions may have been the result of epilepsy or some other medical issue, many still believe these visions were genuine.

Joan described her visions very clearly; in a transcript from her trial, she says: “I was thirteen when I had a Voice from God for my help and guidance. The first time that I heard this Voice, I was very much frightened; it was mid-day, in the summer, in my father’s garden."

Over time, Joan's visions became increasingly specific. According to records, she was told by St. Michael and St. Catherine that she was the savior of France. Her destiny, they told her, was to seek an audience with Charles, the Dauphin (heir) to the French crown. Joan, the visions told her, would be the one to defeat the English, drive them from France, and install Charles as the rightful king.

In 1428, when Joan was about 16 years old, her visions gave her direct instructions. She was to contact Robert de Baudricourt, the garrison commander at Vaucouleurs, who would help her achieve her divinely appointed goal. While Baudricourt turned down the teenager at her first attempts, he later relented; his decision may have related to Joan's apparently clairvoyant ability to describe a French defeat at Orleans. Baudricourt provided Joan with a horse and escort; she cut her hair and dressed in men's clothing to undertake the journey.

Joan of Arc and the Dauphin

Like Baudricourt, the Dauphin was skeptical of Joan's visions. To test her claims, he had a courtier dress up as the dauphin; Joan was immediately able to detect the deception and, without hesitation, went directly to the Dauphin himself. To be sure she was not a witch or under the influence of dark forces, the Dauphin had a group of clergy examine Joan; they found her to be pure and orthodox.

Charles, like many of his countrymen, knew of a prophecy that stated that a maid in armor would come from Lorraine to save France. Joan fulfilled that prophecy, and so, with the Dauphin's blessing, Joan donned armor and led the French troops to Orleans to free the city from an English siege.

The Siege of Orleans

Not surprisingly, Joan was initially excluded from councils of war, but her presence had a significant impact on the morale of the French Army who began to see the conflict with the English as a religious war. Historic records are not clear on Joan's physical contribution to the battle, but she certainly rode with the soldiers and carried a flag.

Prior to Joan's arrival, the siege had gone poorly for the French. Now, however, the Armagnacs (Joan's forces) were able to capture the fortress of Saint-Loup, and then the fortress of Saint-Jean-le-Blanc. Soon after, the French forces consolidated their gains and attacked the English at Les Tourelles. Joan, acknowledged as the heroine of the day, was wounded but nevertheless led the final successful assault against the English.

The impressive victory at Orleans was seen as a sign that Joan of Arc was, indeed, sent by God to support the French. The English, by contrast, believed that she was sent by the Devil.

The Dauphin Is Crowned

Following the liberation of Orleans, Joan wanted to move forward with military plans that would lead to the crowning of the Dauphin. Word of her victory had spread, and new recruits were daily joining her forces. Several military engagements led to victory at Rheims, where Charles VII was crowned King of France in 1429. Joan of Arc stood by him at the coronation.

Capture and Trial

In 1430, Joan was captured in battle and sold to the English. Held illegally in an ecclesiastical prison, she was threatened by male guards and therefore refused to give up her male clothing. The English were determined to prove that Joan's visions were false, as they suggested that God was on the side of the French.

The English court did their best to trick Joan into heresy but was unsuccessful. When asked whether she was in a state of grace , for example, Joan responded: “If I am not, may God put me there and, if I am, may God keep me there.”

At one point, Joan did recant her visions in order to escape death by burning. Her visions returned, however, and she withdrew her recantation. The result: she was sentenced to death as a heretic .

Joan of Arc was burned at the stake on May 30, 1431; she is said to have called on Jesus to her dying breath. Following her execution, her body was burned again and yet again; her ashes were disposed of in the Seine.

Following Joan's death—and largely as a result of her actions and inspiration—France won the Hundred Year's War. A "nullification trial," held in 1456, reversed the heresy charge against Joan, and she was declared innocent. Joan of Arc was beatified by the Roman Catholic Church and canonized a saint in 1920.

Joan has been the subject of countless books, dramas, songs, and movies. She is also the namesake for several French naval vessels.

- Mark, Joshua J. " Joan of Arc ." Ancient History Encyclopedia . Ancient History Encyclopedia, 28 Mar 2019. Web. 27 Aug 2019.

- Rieger, Bertrand, et al. “How Joan of Arc Turned the Tide in the Hundred Years' War.” How Joan of Arc Turned the Tide in the Hundred Years' War , 13 Apr. 2017, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/archaeology-and-history/magazine/2017/03-04/joan-of-arc-warrior-heretic-saint-martyr/.

- “Visions: Joan of Arc.” Joan of Arc - Jeanne D'Arc (1412 – 1431) , 6 Aug. 2019, https://www.jeanne-darc.info/biography/visions/.

- “What Really Caused the Voices in Joan of Arc's Head?” LiveScience , Purch, https://www.livescience.com/55597-joan-of-arc-voices-epilepsy.html.

- The Relationship of Archangel Michael and Saint Joan of Arc

- Persecuting Witches and Witchcraft

- Christian Mysticism Through History

- St. Mary Magdalene, Patron Saint of Women

- Saint Patrick's Life and Miracles

- The Role the Four Evangelists Play in Christianity

- Catholic Church Saints

- Superhero Saints: Bilocation, the Power to Appear in Two Places

- Saint Valentine's Story

- Who Is the Virgin Mary?

- Biography of Moses, Leader of the Abrahamic Religions

- Biography of Matt Redman, Christian Worship Leader

- Biography of Matt Maher, Christian Musician and Worship Leader

- St. Mark the Evangelist: Bible Author and Patron Saint

- Saint John the Baptist, Patron Saint of Conversion

- Praying for Your Country

- Asia - Pacific

- Middle East - Africa

- Apologetics

- Benedict XVI

- Catholic Links

- Church Fathers

- Life & Family

- Liturgical Calendar

- Pope Francis

- CNA Newsletter

- Editors Service About Us Advertise Privacy

Who was Joan of Arc?: Answers to your questions about this heroic saint

By Kelsey Wicks

Denver Newsroom, Aug 13, 2022 / 11:09 am

Visited by St. Michael the Archangel and commissioned by God at the age of 13 to lead the army of France and bring an end to the bloodiest war in European history up to that point, Joan of Arc seems more legend than history.

Here are some of the questions people ask about the Maid of Orléans:

Who was Joan of Arc and what did she do? When and where did she live?

Joan of Arc was a young French peasant, born in 1412, 90 years into the Hundred Years’ War, in the small village of Domremy in eastern France. Destined to save the French from English incursion, she was burnt at the stake in 1431 at the age of 19 after a corrupt Church trial found her guilty of heresy. The trial would later be nullified by the Church and 500 years later, in 1920, Joan of Arc was declared a saint by Pope Benedict XV.

Did Joan of Arc hear voices?

At the age of 13, Joan of Arc had locutions — an interior, mystical phenomenon that involves hearing a divine voice — and reportedly heard the voices of St. Michael the Archangel, St. Margaret of Antioch, and St. Catherine of Alexandria. These three informed her of a special mission given her by God to crown the rightful king of France and thereby end the dynastic dispute that undergirded the Hundred Years’ War.

Along the way, she convinced lords, soldiers, and the French heir to the throne, Charles VII, of her mission. After a lengthy interrogation, she was given charge of the army and successfully lifted the siege of Orléans — on which the fate of the entire war hung — and then freed several towns along the route to crowning Charles VII in the cathedral of Rheims.

Is the story of Joan of Arc a true story?

The story of Joan of Arc is true and historically documented. For this reason, she is among the most famous heroines of history. The task given her by God was so exceptional that it would lead atheist Mark Twain, who wrote a book on her life , to earnestly but exaggeratedly call her “by far the most extraordinary person the human race has ever produced.”

Was Joan of Arc a knight?

Joan of Arc was neither a knight nor a trained soldier, but when she mounted a horse for the first time she was so natural on it that the Duke of Lorraine gifted it to her .

Who were Joan of Arc's parents?

Joan of Arc’s parents were simple peasants, Jacque d’Arc and Isabel Romée. They were farmers and owned sheep, which Joan of Arc tended in her youth.

Did Joan of Arc have any siblings? Does she have any living descendants?

Joan of Arc had three brothers named Jacquemin, Pierre, and Jean, and one sister, Catherine. Both Pierre and Jean accompanied Joan in her quest and fought alongside her.

While Joan of Arc did not have descendants, her entire family was elevated to nobility after Charles VII was crowned, and her village dispensed from paying taxes for three hundred years by the crown.

What was Joan of Arc's nickname?

From the Washington Post to the Maronite convent: Meet Mother Marla Marie

Joan of Arc’s nickname was “La Pucelle” or the Maid, in reference to an old French prophecy that held that a virgin from Lorraine would save the people of France after an immoral woman, later held to be Isabella of Bavaria, jeopardized the crown.

Could Joan of Arc read and write?

Joan of Arc could neither read nor write, and she did not know how to wield a sword before she began her mission. This makes her military success, where hardened commanders failed, even more extraordinary — an act of God as the people saw it.

How did Joan of Arc die?

Joan of Arc was executed by the Catholic Church after a sham trial condemned her of relapsed heresy. The trial was conducted by Church authorities sympathetic to the English, who hoped to see her claims of heavenly assistance to end the war with a French king on the throne discredited. Convicted of heresy, she was taken to the stake to be burned, at which point, under penalty of death, she signed a paper renouncing her visions and agreeing never to wear men’s clothing. Four days later, Joan of Arc confessed to being afraid of her death, said that the visions were true, and donned men’s clothing once again, all of which constituted her supposed relapse to heresy. She was burned at the stake, clutching a crucifix to her body and proclaiming the name “Jesus” as she died, prompting an onlooker to say, “We have burned a saint.”

Where is Joan of Arc buried?

(Story continues below)

Subscribe to our daily newsletter

Joan of Arc’s body was incinerated at the stake, but her heart remained intact after her execution. The soldiers threw the heart in the Seine River so that no one would be able to venerate her remains.

What did Joan of Arc look like?

Joan of Arc scholar Regine Pernoud noted that Joan of Arc was barely over five feet tall, based upon a robe ordered for Joan during her imprisonment by the Duke of Orléans.

How did Joan of Arc change the world and become a saint?

Joan of Arc was not canonized for her ability to free the French from English domination, but for her heroic dedication to the will of God and personal holiness. While Joan commanded the army of France, she drove prostitutes from camp, refused to allow soldiers to rape and pillage the towns that gave them entrance, encouraged confession before battle, and sharply reduced the cussing and oath-swearing of the men under her charge.

She remained committed to a life of contemplation and prayer amid the battles she oversaw, never once lifting her sword against anyone save to chase out a prostitute. Her faith and insights became evident at her trial, forming the foundation of several summaries of theology in the Catechism of the Catholic Church, and her confidence in Jesus and the Catholic Church remained unshaken, even after being wrongly condemned to death by the Church.

What is Joan of Arc the patron saint of?

Joan of Arc is the patron saint of France, soldiers, prisoners, those in need of courage, those ridiculed for their faith, and youth, among other things.

When is Joan of Arc's feast day?

Joan of Arc’s feast day is May 30.

- Catholic News ,

- Catholic saints ,

- Catholic Church in France

Our mission is the truth. Join us!

Your monthly donation will help our team continue reporting the truth, with fairness, integrity, and fidelity to Jesus Christ and his Church.

Premium Content

- HISTORY MAGAZINE

How Joan of Arc turned the tide in the Hundred Years’ War

Divine voices guided a young girl to lead the French against the English. Burned as a heretic in 1431, the Maid of Orléans was both shaped and destroyed by the religious fervor and politics.

By the end of 1430 the rulers of England and France, who had been locked in a war for decades, became increasingly preoccupied by the fate of an 18-year-old peasant girl. In December the faculty of the University of Paris wrote a letter to the king of England, who controlled Paris at that time: “We have recently heard that the woman called The Maid is now delivered into your power, (and)... must humbly beseech you, most feared and sovereign lord... to command that this woman shall be shortly delivered into the hands of the justice of the Church.”

The Maid was Joan of Arc, whose role in liberating the city of Orléans in 1429 had put courage back into the hearts of the embattled French. Even so, her capture soon after was a morale boost for the English, who immediately set out to vilify the woman who had done so much damage to their military campaigns. Shortly after the letter from the University of Paris was written, her trial took place. After the guilty verdict was handed down, Joan was executed in Rouen on May 30, 1431, by being burned alive.

Once her ashes had been scattered in the Seine River, Joan’s detractors hoped her name would be erased from history, but her name has burned more brightly in the hearts and minds of the French ever since then. The humble farm girl turned the tide for the French in the closing years of the Hundred Years’ War. Her claims that the divine voices she heard would lead France to victory made her one of the most celebrated figures of late medieval history. (Read more about the history of the devil in the Middle Ages. )

Portrayed by her enemies as a heretic, a witch, and a madwoman, she was later pardoned and eventually recognized as a saint by the Catholic Church. Today, she is a national hero of the French. Although historians regard Joan’s role as one of many factors in the winning of a complex war, her presence both as a warrior and spiritual visionary sparked the beginnings of France’s rise as a great European power.

Joan’s story has deep roots in the medieval struggle over control of France. Since the invasion of England by the French-speaking William the Conqueror in 1066, the English kings who followed him had maintained a claim to certain French lands. In 1337 King Edward III went to war with French king Philip VI over these territories, the opening act of the Hundred Years’ War.

At first, the English armies won significant battles under the command of Edward III’s son Edward the Black Prince. But the English strength faltered, checked by the ravages of the Black Death in the 1350s , the decline of Edward and his heir, and the rallying of French forces under their king Charles V. By 1413 momentum had started to shift again—this time back in England’s favor with the accession of Henry V.

In 1415 Henry won the Battle of Agincourt over a much larger French force. The victory strengthened England’s standing in Europe. Henry continued to win battles, and after a run of successes, he forced the French to recognize his heirs as successors to the French throne as one of the terms of the Treaty of Troyes in 1420. Henry then married the French king’s daughter Catherine of Valois, and forged a military alliance with Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy. By 1422, the year of King Henry V’s early death, the Anglo-Burgundian alliance controlled much of northern France, including Paris. His son, Henry VI, would continue the fight for these lands.

For Hungry Minds

The warrior maid.

Joan of Arc was born in 1412 in Domrémy, a small village in northeastern France near the border of the lands controlled by the English. From the age of 13, Joan claimed to have heard divine voices and seen visions of St. Michael, St. Catherine of Alexandria, and St. Margaret of Antioch. These divine messengers, she said, were urging her to go to the aid of the man who was the rightful king of France: Charles of Valois, son of Charles VI, whom the English had disinherited.

Because Paris lay deep in English-held territory, Charles had been forced to set up a makeshift court at Chinon on the Loire River. In 1428, Joan traveled there to explain her divine mission to Charles, but was turned away before she could meet with him. She returned to Chinon the following year and was able to convince a panel of theologians of her claim that she had been sent to “liberate France from its calamities.” They granted the teenager an audience with the exiled heir.

Joan informed Charles that divine voices wished her to fight the English and that her participation would lead to his coronation at Reims, the sacred site where France’s kings were crowned. After much examination, she won over Charles and his followers. They decided to put her to use at Orléans, a city under English siege.

Support for La Pucelle (the Maid) was galvanized later that year when Joan, dressed as a warrior, liberated the city of Orléans followed by more French victories. In June French troops crushed the English at Patay, and in July Charles VII was crowned in the cathedral of Reims in the presence of the young warrior prophet who had predicted the event.

But the tide soon turned against Joan of Arc. Instead of expelling the English from France, Joan and her army then suffered several military setbacks. On May 23, 1430, Joan was captured near Paris by the Duke of Burgundy’s men, who later turned her over to the English. Suddenly, her claims appeared weak. How could an envoy of God fall so easily into enemy hands? And if she hadn’t been sent by God, who or what was she?

The English and their allies among the French were in no doubt. Religious doubts about the sanctity of Joan of Arc blended seamlessly into high politics. If the voices she heard were diabolic, then her whole cause, and the coronation of Charles VII itself, had been the work of the devil.

A Harlot to Enemy Eyes

From the moment that Joan of Arc was incorporated into Charles’s army, her Anglo-Burgundian enemies unleashed a war of words against her. As well as the charge that she was inspired by the devil, Joan would endure attempts to slander her sexually for the rest of her life. While her allies emphasized her purity, her enemies denounced her as a “harlot,” who spent all her time surrounded by soldiers.

According to one account, during the siege of Orléans Joan composed a passionate message to the English soldiers, warning them to retreat. She tied her letter to an arrow and had an archer fire it into the English camp. On receipt of the letter, a great cry could be heard from the enemy lines opposite: “News from the whore of the French Armagnacs!”

The Journey to the Stake

The English brought their accusations against Joan, now imprisoned in Rouen, in January 1431. Among them were the charges that she had violated divine law by dressing as a man and bearing arms; that she had deceived simple people by making them believe that God had sent her; and finally that she had committed “divine offense,” namely heresy. Some days later, when the trial opened, the Bishop of Beauvais, Pierre Cauchon, added the charge of witchcraft and declared that Joan was now also under suspicion of having cast spells and invoked demons.

On February 21 Joan answered her charges for the first time before the tribunal. “They asked poor Joan very difficult, subtle, and misleading questions,” said one contemporary, “many clerics and educated men present there would have had problems answering.” But the young woman knew how to defend herself. Her concise replies often disarmed the judges and aroused admiration from the public.

Was Joan sure of being in God’s grace, she was asked? If she answered no, she knew she would be lying, while if she answered yes, she would be arrogantly placing herself beyond the authority of the church. So instead Joan answered: “If I am not [in a state of grace] may God put me there; and if I am, may God so keep me.” Several weeks passed, no confession was forthcoming and Cauchon was forced to drop the charges of witchcraft and concentrate instead on a few key points that he thought would clinch the case of Joan’s heresy. At the beginning of April, a list of 12 accusations, reduced from 70, was approved and then submitted for examination by the University of Paris.

Retraction and Revelation

On May 28, 1431, Bishop Cauchon, accompanied by seven judges, interrogates Joan of Arc. This extract is taken from the transcript:

When, and why, did you revert to dressing as a man? I have done this on my own free will. Nobody has forced me; I prefer the apparel of a man to that of a woman.

Why have you done this? It is both more seemly and proper to dress like this when surrounded by men, than wearing a woman’s clothes. While I have been in prison, the English have molested me when I was dressed as a woman. (She weeps.) I have done this to defend my modesty.

Have you heard, since Thursday, the voices of St. Catherine and St. Margaret? Yes

What did they tell you? That God was telling me, through them, that I had endangered my soul by recanting, and that I had condemned myself for having tried to save my life, If it is not God who sent them, I condemn myself; but I know it really is God who has sent them. Everything I have recanted, I have done so only because of the fear of the fire. If it does not please God to recant, then I will not do so.

You are, therefore, a relapsed heretic. If you, Lords of the Church, had placed me in your own prisons, this would not have happened.

Now we have heard this, we can proceed only according to law and reason.

They found Joan to be a liar and an invoker of malign spirits. While she claimed to have had visions of archangels and saints, the panel judged that these figures were in fact Belial, Satan, and Behemoth. Her wearing of men’s clothes, which she argued was necessary to escape detection while in Burgundian-controlled territory, was portrayed as unnatural and wicked. Joan was found to be a heretic. If she would not repent, she would be punished as such.

You May Also Like

Why are there four heads of John the Baptist?

This unique Camargue pilgrimage is a fitting tribute to France's most singular region

The Christmas Truce of 1914: What historians say really happened

On May 24 she was taken to a site on the outskirts of Rouen and placed beside the stake. The sight may have terrified her, leading to a declaration that she would hand herself over to the authority of the church and sign a retraction. Joan’s sentence was reduced to life in prison and she agreed to dress as a woman.

When the judges went to visit her four days later, however, they found her once again in men’s clothing. The voices had returned, she told them, and had reproached her for her weakness. This relapse was exactly what the accusers wanted; they could now justify the death penalty. Unable to conceal his delight, Cauchon proclaimed to his laughing fellow clerics: “You can have a great celebration, everything is prepared.” On the morning of May 30, Joan was taken to the stake. As the flames consumed her, she could be heard repeatedly proclaiming the name of Jesus.

Joan of Arc had been incarcerated in a room in the castle of Rouen since the first days of her trial. The conditions of imprisonment were, by most accounts, very harsh. As she had attempted to escape on various occasions, her English captors restricted her movements with a long chain attached to her feet and watched her every move. According to one witness, she was also restrained on her bed at night, observed closely by three guards inside the cell and two others outside, all English. According to another witness, the jailers “were wretched brutes who wanted the death of Joan and taunted her mercilessly.” During the brief period in which she had recanted and agreed to wear a dress, Joan claimed her guards had tried to rape her, which is why she decided to put on men’s clothes again. The only people who visited her were her judges, certain curious English nobles, and French-speaking spies who hoped to gain information from her.

The court bailiff of Rouen, Father Jean Massieu, was present at the execution of Joan of Arc, and recorded his observations of her death: “She was led to the Old Market... with an escort of eight hundred soldiers armed with axes and swords. And when she came to the Market she listened to the sermon with fortitude, and most calmly, showing evidence and clear proof of her contrition, penitence, and fervent faith, she uttered pious and devout lamentations... An Englishman who was present made her a [cross] out of wood and handed it to her. She received it and kissed it most devotedly, uttering pious lamentations... Then she put that cross on her breast... and humbly asked me to let her have the crucifix from the church so that she could gaze on it until her death. I saw to it that the clerk of the parish church of Saint Sauveur brought it to her... and her last word, as she died, was a loud cry of ‘Jesus.’”

The Hundred Years’ War would continue for 22 years after her death. English fortunes plummeted after the Duke of Burgundy switched sides to Charles VII. Distracted by the Wars of the Roses at home, England steadily lost all its possessions in France except the port of Calais. Charles VII stabilized his reign and transformed France into a great power.

More than 20 years after her death, an inquiry into Joan’s trial ordered by Charles VII resulted in her sentence being overturned. Joan of Arc’s importance to the French people was further solidified when she was made a saint, four centuries later, in 1920.

English Sinner, French Saint

Following the execution of Joan of Arc, Henry VI of England wrote detailed letters to sovereigns, prelates, and nobles across Europe to announce that a certain “false prophetess” had received her just punishment. He even assured them that Joan had confessed to having been a heretic before her execution. In Paris a general procession was organized to celebrate her demise.

Several years later, when Charles VII reconquered Normandy and expelled the English from France, he made it his business to annul Joan’s trial, with the help and support of the papacy. This was as much a political act as a religious act, a way for Charles VII to ratify his legitimacy as a king designated by God—just as the Maid herself had declared.

Related Topics

- HISTORY AND CIVILIZATION

Meet Sara-la-Kali, the patron saint of displaced people

The incredible details 'Masters of the Air' gets right about WWII

The truth behind the turbulent love story of Napoleon and Joséphine

In 1647, Christmas was canceled—by Christians

This mysterious son of a ‘witch’ founded Glasgow

- Environment

- Perpetual Planet

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Paid Content

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Joan of Arc

By alvin ward | jan 6, 2020.

MILITARY (1412–1431); DOMRÉMY-LA-PUCELLE, FRANCE

Today, Joan of Arc (or Jeanne d'Arc) is most often referred to as a heroine and early symbol of female empowerment. But during her brief life, she was deemed a heretic—and burned at the stake for it in Rouen, France on May 30, 1431, when she was just 19 years old. Read on to learn more facts about Joan’s early life and premature death, how history transformed her from sinner to saint, some famous quotes, and how her legacy has lived on in movies, books, and art.

1. Joan of Arc’s birth date is unknown, but her childhood was marked by war.

Though her exact date of birth isn’t known, Joan of Arc was born in the French village of Domrémy (now known as Domrémy-la-Pucelle) around 1412 to Jacques d’Arc and his wife, Isabelle. Her remote area of northeastern France was not immune to the growing dangers of the Hundred Years’ War , a protracted conflict between France and England that lasted from 1337 to 1453 and saw the French crown fall into dispute. Raids were common at the time, especially as the area in which Joan and her family lived was controlled by the Burgundians, a faction allied with England against the French ruling family. During one incident, her home village was burned down.

2. Joan of Arc began having visions when she was just 13 years old.

While Joan of Arc spent her teenage years fighting for the French army toward the end of the Hundred Years’ War, her willingness to go into battle wasn’t just an act of patriotism. In 1424, Joan began having visions in which St. Michael the Archangel, St. Catherine of Alexandria, and St. Margaret of Antioch appeared to her to instruct her to live a life dedicated to God. As time went on, the visions grew more intense, and eventually the saints would tell her to meet with the Dauphin, the future Charles VII, whom she viewed as the rightful heir to the French throne. The visions urged Joan to convince him to allow her to take up arms against the English and drive them out of France, which would result in Charles officially being recognized as king.

In May 1428, Joan of Arc tried to convince Sir Robert de Baudricourt, commander of a royal garrison, to let her go see Charles. She was initially turned away, but her persistence paid off, because by February 1429, Joan and her visions had gained enough support from the war-weary townspeople to earn Baudricourt's respect and a trip to Chinon to meet with Charles. While traveling to the court, she cut her hair short and began dressing like a man to blend in with the other soldiers.

3. Joan of Arc had correctly spotted Charles VII in disguise.

Joan of Arc claimed she would be able to recognize the Dauphin without ever having met him, so before their first meeting, the future king decided to see this ability in person. He disguised himself as just another member of the court. When Joan arrived, true to her word, she was still able to pick him out, and before long, Charles was ready to listen to her.

While she had no military experience, Joan of Arc managed to convince Charles to let her lead an army to the town of Orléans, then occupied by English forces, so that she could liberate it in his name. In April 1429, as English and French forces battled near the west side of the city, Joan and her troops entered through the east, virtually unopposed, bringing much-needed supplies and reinforcements with them. Once entrenched in Orléans, Joan— dressed in white armor and riding atop a white horse—became an inspiration for the French soldiers and was known for charging into battles, distributing food , and openly calling for the English to depart.

Joan of Arc was an invaluable symbol of hope for the French in Orléans, and by May 8, 1429, after a series of battles within the city, Joan and her army were successful in driving the English out. After a few more victories, Joan of Arc attended Charles's triumphant coronation in Reims in July 1429.

4. Joan of Arc was put on trial for heresy and witchcraft.

In May 1430, Joan of Arc was captured by Burgundian troops during a siege on the town of Compiègne. After her capture, she was sold to the English for 10,000 francs , and she would be held in prison for more than a year on charges of heresy, witchcraft, and wearing men’s clothing. The latter was directly forbidden in the Biblical verse Deuteronomy 22:5, which states that women should not wear “that which pertaineth unto a man.”

A very pro-English trial ensued , with a guilty verdict all but confirmed. On May 28, 1431, Joan signed a retraction of her claims that saints had appeared before her and agreed to only dress as a woman, which would have reduced her death sentence to life in prison, instead. But a few days later, she was again found in men’s clothing and claimed that the visions had returned to her. Her retraction now nullified, the death sentence would be carried out.

5. Joan of Arc died when she was burned at the stake.

On May 30, 1431, Joan of Arc was burned at the stake in the Place du Vieux-Marché in Rouen, France. The main charges after her relapse did not involve witchcraft but were instead related to wearing men’s clothing and falsely claiming that God had urged her to commit violence against the English. Joan of Arc was only 19 at the time of her execution , and it’s estimated that 10,000 people gathered to watch. After her death, a legend soon grew that Joan's heart had somehow survived the fire.

6. Joan of Arc Became a Saint in 1920.

The rehabilitation of Joan of Arc’s reputation took place soon after her execution. In 1456, a retrial was held, ordered by King Charles VII, that posthumously overturned Joan’s conviction and cleared her of any dubious claims of witchcraft and heresy. While Joan of Arc would remain a hero in France for centuries, she gained wider immortality on May 16, 1920, when she was officially canonized by the Catholic Church and was named the patron saint of France, soldiers, and prisoners.

7. The Passion of Joan of Arc is known as one of the most important silent movies.

Less than 10 years after Joan of Arc was made a saint by Pope Benedict XV, her story was brought to the big screen while the movie industry was still in its infancy. Titled The Passion of Joan of Arc , this 1928 silent film is the product of director Carl Theodor Dreyer and star Renée Jeanne Falconetti, who played Joan of Arc. The movie depicts Joan’s imprisonment, trial, and execution. And while it was a financial flop at the time, it has since earned a reputation as one of the finest films of the silent era, with publications like Sight & Sound and The Village Voice , along with critics like Roger Ebert , singing its praises.

8. Jules Bastien-Lepage's Joan of Arc Painting Has Been in New York City's Metropolitan Museum of Art Since 1889.

Joan of Arc has inspired countless different works of art in nearly every medium imaginable. In addition to the Saint Joan of Arc statue in Notre Dame cathedral, one of the most recognizable works inspired by the famed French hero is the painting by artist Jules Bastien-Lepage that hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The figure of Joan was modeled by Marie-Adèle Robert, one of the artist’s cousins, and was completed in 1879.

Famous Joan of Arc Quotes

- “ I do not fear men-at-arms; my way has been made plain before me. If there be men-at-arms my Lord God will make a way for me to go to my Lord Dauphin. For that am I come.”

- “I would rather die than do something which I know to be a sin, or to be against God's will.”

- “I was in my thirteenth year when I heard a voice from God to help me govern my conduct. And the first time I was very much afraid.”

- “ Children say that people are hung sometimes for speaking the truth.”

10 Books About Joan of Arc, The Maid of Orléans

Ann can often be found walking very slowly through the aisles of bookstores, making sure that nothing new has come out she doesn’t know about yet, and then eagerly telling people about them. She writes about women from history at annfosterwriter.com , and about books, film, TV, and feminism at various other sites. She prefers her books to include at least three excellent plot twists, which is why she usually reads the end first. Twitter: @annfosterwriter

View All posts by Ann Foster

Joan of Arc is one of those historical figures many people have heard of, but that not everyone knows all the details about. An illiterate French peasant girl, she claimed to have been visited by angels who instructed her to lead armies against the English. By age 16, she donned armor and was doing just that. But by age 19, at the height of her fame, she was put on trial and sentenced to death by fire.

Her story has been reimagined in manga, movies, and countless books over the years. Here are ten recent ones that help explain her story to both those familiar with her as well as those learning about her for the first time.

Note: as with much writing about European history, these books have mostly all been written by white authors.

Joan of Arc Books for Children

Who was joan of arc by pam pollack and meg solvino.

This book, from the Who Was/Is series, explains Joan’s story in plain language. Aimed at children aged 8–12, this basic biography emphasizes Joan’s bravery and how unusual it was for a young girl to accomplish all that she did.

You Wouldn’t Want to be Joan of Arc! : A Mission You Might Want to Miss by Fiona Macdonald, illustrated by David Antram

This book has a lighthearted tone and lots of illustrations. Readers will learn the basic facts of Joan’s life, as well as often grisly details about life as a 15th century French soldier.

Joan of Arc by Kristin Thiel

This biography, part of the Great Military Leaders Series, is aimed at middle school readers. Combining text and illustrations, this work covers the historical backdrop of Joan’s life as well as her continued prominence as both a religious and historical figure.

Joan of Arc Books for Teens

Language of fire: joan of arc reimagined by stephanie hemphill.

Hemphill has already written YA novels in verse about Mary Shelley ( Hideous Love ), Sylvia Plath ( Your Own, Sylvia ), and the Salem Witch Trials ( Wicked Girls ). In this, her latest work, she makes Joan’s story personal as it imagines her voice telling her own story from ordinary girl to war hero.

Voices: The Final Hours of Joan of Arc by David Elliott

Also written in verse, this book uses the voices of those who surround Joan to explore her story. These include the voices of her family and even the trees, clothes, cows, and candles of her childhood. In so doing, issues of gender, misogyny, and the peril of speaking truth to power are examined.

Messenger: The Legend of Joan of Arc by Tony Lee and Sam Hart

This graphic novel shares Joan’s story in a compelling mix of text and imagery. Following the co-creators’ previous works Outlaw: The Legend of Robin Hood and Excalibur: The Legend of King Arthur , this is a visually striking retelling of Joan’s legendary story.

Joan of Arc Books for Adults

The maid and the queen: the secret history of joan of arc by nancy goldstone.

This book explores the possible connections between Joan and Yolande of Aragon, queen of Sicily. Yolande, like Joan, supported the French dauphin against his enemies. But despite the queen’s armies and spies, victory seemed out of reach…until Joan arrived on the scene.

Joan of Arc: A History by Helen Castor

Author Helen Castor, author of She-Wolves: the Women Who Ruled England Before Elizabeth , here turns her lens across the pond to explore Joan’s story. Referring to documents from both of Joan’s trials, this book examines the first-person accounts of Joan, her family, and friends to develop as full a picture as possible of the real young woman and her life.

Joan of Arc: A Life Transfigured by Kathryn Harrison

Novelist and memoirist Kathryn Harrison deftly weaves historical fact, myth, folklore, artistic representations, and centuries of scholarly and critical interpretation into a compelling narrative, she restores Joan of Arc to her rightful position as one of the greatest heroines in all of human history.

The Maid: A Novel of Joan of Arc by Kimberly Cutter

The flexibility of historical fiction allows Cutter to imagine the parts of Joan’s story that fall between recorded history. What was her relationship like with her parents? What was it like to be a teenage girl leading armies in the fifteenth century? This is a novel about the power and uncertainty of faith, and the exhilarating and devastating consequences of fame.

Can’t get enough history? Check out our list of 15 new historical fiction reads to pack for your summer vacation !

You Might Also Like

Joan of Arc: Facts & Biography

Joan of Arc is the modern-day name of a teenage woman who, driven by voices she heard, fought to drive the English out of France and crown Charles VII as the French king.

Although we know her as Joan of Arc, or Jeanne d'Arc in French, she called herself Jehanne la Pucelle, or Joan the Maid. She is also known as the "Maid of Orléans." Pucelle means “maid” and also signifies that she was a virgin, an important distinction given that her society held female virginity before marriage in high regard.

Her military career lasted from between April 1429, when she left with troops to help raise the siege of Orléans, and May 1430 when she was captured by troops loyal to John of Luxembourg. She was subsequently handed over to forces loyal to English King Henry VI and after a trial she was condemned and burned at the stake in May 1431. At her trial, Joan said that she thought her age was 19.

She lived at a time when France was divided among Charles VII, who ruled south of the Loire River; Henry VI, the English boy-king who ruled much of northern France; and the Duchy of Burgundy, which controlled a rump of territory and was allied with the English.

The father of Henry VI had defeated the French at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, a defeat that eventually led Charles VII’s father to agree to a treaty that allowed the French crown to pass to the English after his death. Charles VII refused to recognize this treaty and continued resistance albeit as an uncrowned ruler.

Although Joan’s military career was brief, and scholars debate the degree of control she had over the campaigns she was in, she raised French morale and her time in action was one that saw a recovery in French military fortunes, which ultimately allowed Charles VII to be crowned King of France.

Her reputation was such that the English, led in France by the regent John, Duke of Bedford, blamed their defeats on her alleged supernatural powers. “A disciple and limb of the Fiend, called the Pucelle, that used false enchantment and sorcery,” is how he described her in a report.

To Joan and her supporters, her mission of driving the English out of France and crowning Charles was one that was called upon her by God. “I am sent here in God’s name, the King of Heaven, to drive you body for body out of all France...” she said in a challenge written down and sent to the English before she went into battle at Orléans.

Modern-day medical doctors have speculated that she may have suffered from a medical condition, such as schizophrenia or a form of epilepsy, which made her hear voices.

A world where children fought children

She was born in the village of Domrémy (now called Domrémy-la-Pucelle in her honor) in either 1412 or 1413. At the time she lived, it was a settlement on the border between France and the Holy Roman Empire.

It was also a place of conflicting loyalties. While the people of the village were generally loyal to Charles VII, many of the nearby territories were loyal to the Duchy of Burgundy, which was allied with the English. As Joan said at her trial, the place where she grew up was one where children literally fought children, some of them coming back “wounded and blooded.”

Her mother’s name was Isabelle Romee, and there are conflicting accounts as to the spelling of her father’s name. Researcher Nora Heimann notes in her book "Joan of Arc in French Art and Culture" (Ashgate Publishing, 2005) that her father’s name has been recorded with various spellings, including “Jacob d’Arc,” “Jaqes d’Arc,” “Jacques Tarc” and “Jacques Darc.”

While the last name “Arc” is what she is called today Joan didn’t use that name on campaign, preferring to be called “la Pucelle.” She started hearing voices at the age of 13, recounting at her trial that the first time she heard them was in her family’s garden. “The voice came from the right, from the direction of the church, and was accompanied by a bright light,” she said. The ringing of church bells would sometimes trigger them.

In 1428, her village was attacked by Anglo-Burgundian forces and her family fled, returning after the attack was over. After this, she left home for the last time, going to Vaucouleurs and eventually persuading a reluctant local official named Robert de Baudricourt to give her an escort to take her to see Charles VII at his castle at Chinon.

Siobhan Nash-Marshall, now a professor at Manhattanville College, writes in her book "Joan of Arc: A Spiritual Biography" (Crossroad Publishing, 1999) that the journey was more than 300 miles (480 kilometers), taking them through territory controlled by the enemy and bandits. Traveling by night, avoiding towns, and at times going through the wilderness they reached the castle.

Persuading Charles

One of history’s great mysteries is how a teenage girl hearing voices and claiming to be on a mission from God persuaded Charles VII (at the time in his 20s) to give her soldiers and send her to help raise the siege of Orléans.

“We will never know what happened at Chinon. It is one the abiding mysteries of history,” writes Marina Warner, a professor at the University of Essex, in her book "Joan of Arc: The Image of Female Heroism" (Oxford University Press, 2013). Warner notes that at her trial, Joan asked not to be pressed on what happened at Chinon, and when questioned said that Charles received a sign, of some form, to signify that her story was true.

“Go boldly! For when you stand before the king, he will have a sign [that will make him] receive you and believe in you,” her voices told her. After her meeting with Charles, she was sent to Poitiers to be questioned about her experiences, and subsequently was given a squire, a page and some soldiers and sent with a force to relieve Orléans.

Warner points out that, contrary to popular belief, Joan was not in command of this force. Rather, the force was led by the Count of Dunois. Ignoring Joan’s advice, the count sneaked around the English fortifications, trying to get his force, loaded with equipment and provisions, into Orléans without a major battle. “This infuriated Joan, who was clearly eager to get on with her mission,” Nash-Marshall writes.

Joan succeeded in making a believer out of the count when he found his force stranded beside a riverbank, unable to bring supplies to Orléans across barges because the wind was against him.

She told the count that “I am bringing you better help than ever you got from any soldier or any city. It is the help of the King of Heaven.” The count later claimed that at that moment the wind changed direction, allowing his force and supplies to cross into Orléans.

Nash-Marshall points out that, when in Orléans, she provided a morale boost to the civilians and soldiers there. Even though the French now outnumbered their besiegers, their commanders were reluctant to attack the Anglo-Burgundian forces until more help arrived. Joan pressed for an assault, and eventually an attack was launched against the most isolated of the enemy fortifications to the east.

Joan provided another boost during the battle, when she “arrived at the scene, it is claimed, a roar went up among the French troops, who redoubled their efforts and won the day with ease,” writes Nash-Marshall. With French confidence growing, the soldiers attacked one besieging fort after another, eventually breaking the siege of the city.

Nash-Marshall points out that the morale boost Joan gave cannot be underestimated. “French morale was so low before Joan appeared that the [French] even lost those battles in which they outnumbered the Anglo-Burgundians on a massive scale. More often than not, they simply preferred to stay off the battlefield.”

A king crowned

With Orléans saved, and subsequent French campaigns succeeding in liberating towns on the Loire River, Joan was now in a position to fulfill a major part of her God-given mission — the crowning of Charles VII as King of France.

French kings were crowned at Reims, a city that at the time was under control of the Anglo-Burgundians. Despite it being behind enemy lines, Joan begged Charles to go, and the king eventually set off with a party that encountered surprisingly little resistance, actually gaining the support of several towns held by the enemy on the way.

When they arrived in Reims, they held the ceremony as quickly as possible, with Charles being knighted, anointed and crowned as best as could be done under the circumstances.

Joan said at her trial that she embraced the newly crowned king at his knees and said “gentle king, now is executed the will of God, who wished that the siege of Orléans should be lifted, and that you should be brought into this city of Reims to receive your holy consecration, thus showing that you are a true king, and he to whom the kingdom of France should belong.”

The ceremony took place on July 17, 1429, and, although Joan didn’t know it, this would represent the height of her military achievements.

An aggressive Joan and a diplomatic king

With momentum on the newly crowned king’s side, there was pressure on him to march on Paris, the capital of France, and reclaim it. Joan, along with other commanders, pushed for this, but the king was hesitant. Nash-Marshall pointed out that the king actually agreed to a 15-day truce with his enemies, a mere ruse, as it turned out, to give them time to fortify Paris.

When the attack on Paris finally happened, the king was hesitant to commit the bulk of his forces to it and it ultimately failed. Furthermore, it happened on Sept. 8, the birthday of the Virgin Mary, something that hurt Joan’s image as no fighting was supposed to take place on this holy day.

Joan’s ambitions to drive the English out of the rest of France only went downhill from there. The king made a truce with the Burgundians, the allies of the English, which was to last until Christmas. Furthermore, before winter set in, Charles VII disbanded his army.

Never again would Joan’s efforts receive support from the king, who appeared more determined to pursue diplomacy and consolidate his gains. On Dec. 29, Joan and her family were ennobled; something which Nash-Marshall points out gave her the right to attack the English without the king’s permission. “Charles' gesture was a courteous but unmistakable farewell,” Nash-Marshall writes.

Capture, trial and execution

Without the backing of the king, Joan was unable to launch any more major attacks. In May 1430, an Anglo-Burgundian force laid siege to the town of Compiègne and Joan, with no more than a few hundred men, rushed to its aid. Her voices had told her a few months before that she would soon be captured by the English but she went to the town’s defense anyways.

The Anglo-Burgundian force was far larger than her own and she tried to aid the town’s defenders by launching hit-and-run attacks to keep the enemy off balance. On May 23 one of these attacks failed, the enemy having sufficient warning to give chase to her much smaller force. Although most of her soldiers managed to escape back to the town walls, Joan herself was captured by troops loyal to John, the Duke of Luxembourg.

This marked the end of her military career and the beginning of her captivity. Although Joan had sympathizers among the Duke’s family, and John was originally reluctant to hand her over to the English, he was eventually paid 10,000 livres to turn her over, an immense amount of money at the time. Pierre Cauchon, a bishop who supported the English and pushed for her arrest, remarked that although it was a king’s ransom “certainly the capture of this woman in no way resembles the capture of a king, or princes, or other persons of high rank.”

When Joan learned she was to be turned over to the English, she threw herself off a tower, apparently in an attempt to commit suicide. She survived her attempt and was brought to Rouen to face trial.

The verdict was never in doubt. “Her side saw her as a holy virgin, her enemies as a polluted sorceress,” Warner said. She was interrogated thoroughly, the Anglo-Burgundians tried to discredit her by questioning her virginity and linking her to magic. Even her wearing of men’s clothes was used against her, her prosecutors claiming that it was against the natural order of things. [ Related: Medieval Justice Not So Medieval ]

Her trial and interrogations went on through the first four months of 1431. During that time Charles VII, the French king whom she had helped crown, made no attempt to get her back through ransom or prisoner exchange. “This suggests, hard as it may seem, that Charles and his advisers were disillusioned enough to tolerate her condemnation as a heretic,” Warner writes.

On May 30, 1431, she was led to the stake. “When Joan of Arc went to the stake, she wore over her shaven head a tall mitre like a dunce’s cap. On the cap, the words of her crimes were inscribed in Latin, for her shame and the dread of the onlookers,” writes Nash-Marshall. In a nutshell she was labelled “heretical, relapsed, apostate and idolatrous.”

As the fire was lit, and spread, she uttered her last words, “Jesus! Jesus! Jesus,” she said, repeating Christ’s name several times before her death.

Canonization

In the century to follow, the English lost control over their remaining French territories. Calais, the last English territory in France, fell in 1558. Joan’s name was formally rehabilitated in an inquiry during the 1450s, and in 1920 she was made a saint of the Catholic Church.

The New York Times reported that her canonization ceremony at St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome attracted “60,000 to 70,000 persons” and “was the greatest and most impressive function performed in the historic basilica not only by the present Pontiff but for several centuries past.”

— Owen Jarus , LiveScience Contributor

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

30,000 years of history reveals that hard times boost human societies' resilience

'We're meeting people where they are': Graphic novels can help boost diversity in STEM, says MIT's Ritu Raman

Alien 'Dyson sphere' megastructures could surround at least 7 stars in our galaxy, new studies suggest

Most Popular

- 2 2,500-year-old Illyrian helmet found in burial mound likely caused 'awe in the enemy'

- 3 James Webb telescope detects 1-of-a-kind atmosphere around 'Hell Planet' in distant star system

- 4 Heavy metals in Beethoven's hair may explain his deafness, study finds

- 5 Papua New Guineans, genetically isolated for 50,000 years, carry Denisovan genes that help their immune system, study suggests

- 2 Sun launches strongest solar flare of current cycle in monster X8.7-class eruption

- 3 Newfound 'glitch' in Einstein's relativity could rewrite the rules of the universe, study suggests

Advertisement

Supported by

‘Joan of Arc: A History,’ by Helen Castor

- Share full article

By Amanda Foreman

- July 2, 2015

Fame is like a parasite. It feeds off its host — infecting, extracting, consuming its victim until there’s nothing left but an empty husk. For the lucky (or unlucky, depending on your point of view), with the emptiness comes the possibility of a long afterlife as one of the blowup dolls of history.

These women — and they’re almost always women — become the public’s playthings in perpetuity. Stripped of truth, deprived of personhood, they can be claimed and used by anyone for any purpose. Exhibit A is Joan of Arc, simultaneously canonized by Pope Benedict XV and the women’s suffrage movement; sometime mascot of 19th-century French republicans, 20th-century Vichy France and the 21st-century National Front. She has over a dozen operas and several dozen movies to her name. And she’s the single thread that unites a bewilderingly diverse crowd of playwrights, writers, philosophers, poets and novelists, from Shakespeare to Voltaire, Robert Southey, Mark Twain, George Bernard Shaw, Vita Sackville-West and Bertolt Brecht.

No wonder the British historian Helen Castor begins her highly satisfying biography of Joan of Arc by stating the obvious: “In the firmament of history,” the Maid of Orléans is a “massive star” whose “light shines brighter than that of any other figure of her time and place.” Indeed, Castor insists, Joan’s star still shines. But what a travesty if all people can see is the reflected vainglory of their own desires.

Castor’s corrective approach to the problem of Joan’s fame is to turn the mirror outward, changing the point of view from Joan herself to the times in which she lived. Follow her too closely, Castor argues, and “it can seem, unnervingly, as though Joan’s star might collapse into a black hole.” To those who think they know her story, this statement might seem unnerving. But Castor doesn’t mean the facts are wrong or need revising.

Joan was born to a moderately prosperous tenant farming family around 1412. In February 1429, against all the odds, she persuaded Charles VII to allow her to lead an army to relieve the city of Orléans from its seven-month-long siege by the English. Over the next few months, she enjoyed a series of spectacular victories. Galvanized by her presence on the battlefield, the French took back their cities and towns from the English (and their French allies) one after another, beginning with Orléans. Charles was crowned king on July 17 in the cathedral at Reims with Joan standing proudly beside him. But then, on Sept. 8, the Joan juggernaut came to a grinding halt before the gates of Paris.

The following May, she was captured by pro-English French forces at Compiègne. The last phase of her life began in November 1430 when she was sold to the English for 10,000 francs. They wanted her for the simple reason that killing her would not be enough to undermine Charles VII’s claim to the throne: They had to destroy her reputation and any hint of divine legitimacy she had conferred on him.

The interrogation and show trial by handpicked French clerics lasted until May 1431. Central to the charge of heresy was her transgressive behavior against medieval gender roles, particularly with regard to her wearing of men’s clothes. After the sentence was announced, she was paraded through Rouen before being burned with slow deliberation in front of thousands of spectators.

For sheer drama, the story of Joan of Arc needs no embellishment, but without proper context its meaning is easily twisted. Castor’s great coup is in framing this biography within not just one but two contexts. The first, explaining the culture and politics that created the opportunity for a militaristic maid, takes up roughly a third of the book, leaving Joan herself to appear on Page 89. By working forward from the early decades of the Hundred Years’ War, as the Anglo-French struggle for the French throne is called, Castor is able to demonstrate the varying degrees of gravitational force exerted by contingency, expediency, sectarianism and nationalism on the people who determined Joan’s fate.

The siege of Orléans was the turning point. After more than 90 years of bloodshed, treachery and civil strife, Joan’s demonstrable promise that she could deliver France back to the French seemed to show that God was on their side. But what did that mean if the population was divided between two factions, the Burgundians and the Armagnacs, each with its own vision of dynastic power and national boundaries? Castor argues that those who opposed Joan believed they had a moral cause, from the Roman Catholic Church, which shuddered at her claim of individual conscience over blind obedience, to the bourgeois citizens of Paris, who felt more affinity with the commercial cities of Flanders than with the southern provinces ruled by the Armagnacs.

All this is entirely convincing and gripping, but what makes Castor’s biography notable is the other context she subtly weaves through the narrative. Related with little fanfare or highlighting, it puts the women back into the story. The only time Joan’s life became truly an all-male affair was during the orgy of misogyny that passed as her trial. Contrary to the sword-and-crucifix chronicles of the Middle Ages, there was more to the Hundred Years’ War than the blood spilled on the battlefield. The women were there too. And Castor focuses on two whose actions were crucial: Isabeau, the mother of Charles VII, and Yolande, Duchess of Anjou, his mother-in-law. Yolande, Castor observes, “had what Armagnac France needed . . . the insight to perceive God’s plan that France should be reunited under Charles’s kingship, and to comprehend how it might be brought about.” That plan involved both helping Joan to reach Charles and upholding her claim to be the handmaiden of God. After Joan’s death, Yolande used her formidable talent for deal-making to shore up Armagnac support. In Castor’s words, “a queen’s gambit was already in play.”

Earlier this year, the city of Rouen opened a new museum dedicated to Joan of Arc, intended in part to rescue her image from the myths that have surrounded it. Castor’s book is another important way of returning Joan’s “star” to the realm where it belongs, the human one.

JOAN OF ARC

By Helen Castor

Illustrated. 328 pp. Harper/HarperCollins Publishers. $27.99.

Amanda Foreman is the author, most recently, of “The World Made by Women: A History of Women From the Apple to the Pill,” to be published in 2017.

Like to be first? Get The New York Times Book Review before it appears online every Friday. Sign up for the email newsletter here.

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

As book bans have surged in Florida, the novelist Lauren Groff has opened a bookstore called The Lynx, a hub for author readings, book club gatherings and workshops , where banned titles are prominently displayed.

Eighteen books were recognized as winners or finalists for the Pulitzer Prize, in the categories of history, memoir, poetry, general nonfiction, fiction and biography, which had two winners. Here’s a full list of the winners .

Montreal is a city as appealing for its beauty as for its shadows. Here, t he novelist Mona Awad recommends books that are “both dreamy and uncompromising.”

The complicated, generous life of Paul Auster, who died on April 30 , yielded a body of work of staggering scope and variety .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

Women Heroes

Joan of arc.

The teenage girl who helped lead a French army to victory

Joan of Arc knew nothing but war. Her country of France had been fighting England for about 75 years when she was born around 1412. But when she was 16, even though she was poor and living at a time when women did not fight in the military—and certainly did not lead men—Joan came to believe that God had chosen her to lead her country to victory during what’s now known as the Hundred Years War.

By 1428, England controlled much of France, and the French king no longer ruled. So Joan persuaded a local government leader to escort her through English-held territory to meet with and convince King Charles VII to let her lead his armies and help him regain the throne. Legend has it that Joan knew details about the king that no one else did, and he came to believe her claim that God had chosen her to lead.

The king ordered the army to take back the city of Orléans, accompanied by 17-year-old Joan. She cropped her hair short like a man’s, donned a suit of white armor, and successfully helped French troops to victory in March 1429, even after being wounded in battle. King Charles then took back his crown a few months later. At the ceremony, Joan was at his side.

A few months later, though, Joan was captured in battle and held captive for more than a year. She was accused of witchcraft and the crime of dressing as a man. Not wanting to threaten his newly returned crown, the king didn’t come to Joan’s aid, and in 1431, when she was just 19, she was burned at the stake.

But beloved by France, she was officially cleared of her crimes 20 years later and became a Catholic saint in 1920. Today Joan of Arc remains the patron saint of France and a symbol of national pride.

Read this next

Women's history month, the women's suffrage movement, african american heroes.

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your California Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell My Info

- National Geographic

- National Geographic Education

- Shop Nat Geo

- Customer Service

- Manage Your Subscription

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- Saint of the Day

Saint Joan of Arc

- Franciscan Media

Image: Joan of Arc listening to his voice | Léon-François Bénouville

Saint of the day for may 30, (january 6, 1412 – may 30, 1431).

Saint Joan of Arc’s Story

Burned at the stake as a heretic after a politically-motivated trial, Joan was beatified in 1909 and canonized in 1920.

Born of a fairly well-to-do peasant couple in Domremy-Greux southeast of Paris, Joan was only 12 when she experienced a vision and heard voices that she later identified as Saints Michael the Archangel, Catherine of Alexandria, and Margaret of Antioch.