Find anything you save across the site in your account

A Guide to Thesis Writing That Is a Guide to Life

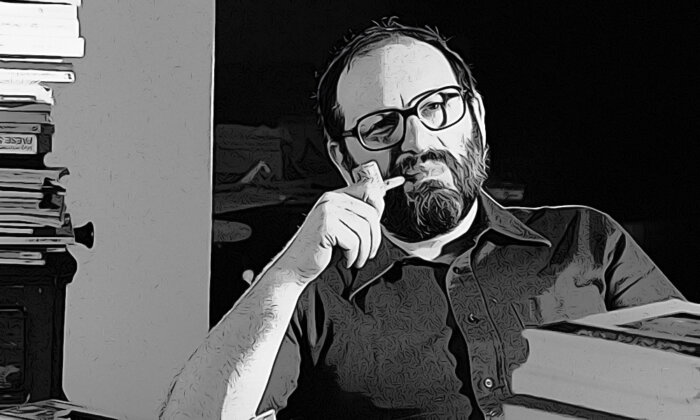

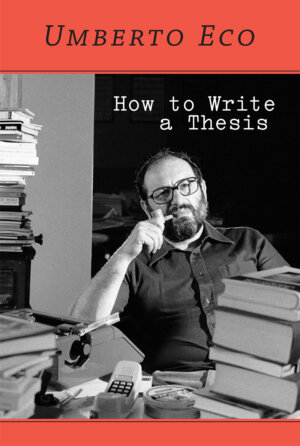

“How to Write a Thesis,” by Umberto Eco, first appeared on Italian bookshelves in 1977. For Eco, the playful philosopher and novelist best known for his work on semiotics, there was a practical reason for writing it. Up until 1999, a thesis of original research was required of every student pursuing the Italian equivalent of a bachelor’s degree. Collecting his thoughts on the thesis process would save him the trouble of reciting the same advice to students each year. Since its publication, “How to Write a Thesis” has gone through twenty-three editions in Italy and has been translated into at least seventeen languages. Its first English edition is only now available, in a translation by Caterina Mongiat Farina and Geoff Farina.

We in the English-speaking world have survived thirty-seven years without “How to Write a Thesis.” Why bother with it now? After all, Eco wrote his thesis-writing manual before the advent of widespread word processing and the Internet. There are long passages devoted to quaint technologies such as note cards and address books, careful strategies for how to overcome the limitations of your local library. But the book’s enduring appeal—the reason it might interest someone whose life no longer demands the writing of anything longer than an e-mail—has little to do with the rigors of undergraduate honors requirements. Instead, it’s about what, in Eco’s rhapsodic and often funny book, the thesis represents: a magical process of self-realization, a kind of careful, curious engagement with the world that need not end in one’s early twenties. “Your thesis,” Eco foretells, “is like your first love: it will be difficult to forget.” By mastering the demands and protocols of the fusty old thesis, Eco passionately demonstrates, we become equipped for a world outside ourselves—a world of ideas, philosophies, and debates.

Eco’s career has been defined by a desire to share the rarefied concerns of academia with a broader reading public. He wrote a novel that enacted literary theory (“The Name of the Rose”) and a children’s book about atoms conscientiously objecting to their fate as war machines (“The Bomb and the General”). “How to Write a Thesis” is sparked by the wish to give any student with the desire and a respect for the process the tools for producing a rigorous and meaningful piece of writing. “A more just society,” Eco writes at the book’s outset, would be one where anyone with “true aspirations” would be supported by the state, regardless of their background or resources. Our society does not quite work that way. It is the students of privilege, the beneficiaries of the best training available, who tend to initiate and then breeze through the thesis process.

Eco walks students through the craft and rewards of sustained research, the nuances of outlining, different systems for collating one’s research notes, what to do if—per Eco’s invocation of thesis-as-first-love—you fear that someone’s made all these moves before. There are broad strategies for laying out the project’s “center” and “periphery” as well as philosophical asides about originality and attribution. “Work on a contemporary author as if he were ancient, and an ancient one as if he were contemporary,” Eco wisely advises. “You will have more fun and write a better thesis.” Other suggestions may strike the modern student as anachronistic, such as the novel idea of using an address book to keep a log of one’s sources.

But there are also old-fashioned approaches that seem more useful than ever: he recommends, for instance, a system of sortable index cards to explore a project’s potential trajectories. Moments like these make “How to Write a Thesis” feel like an instruction manual for finding one’s center in a dizzying era of information overload. Consider Eco’s caution against “the alibi of photocopies”: “A student makes hundreds of pages of photocopies and takes them home, and the manual labor he exercises in doing so gives him the impression that he possesses the work. Owning the photocopies exempts the student from actually reading them. This sort of vertigo of accumulation, a neocapitalism of information, happens to many.” Many of us suffer from an accelerated version of this nowadays, as we effortlessly bookmark links or save articles to Instapaper, satisfied with our aspiration to hoard all this new information, unsure if we will ever get around to actually dealing with it. (Eco’s not-entirely-helpful solution: read everything as soon as possible.)

But the most alluring aspect of Eco’s book is the way he imagines the community that results from any honest intellectual endeavor—the conversations you enter into across time and space, across age or hierarchy, in the spirit of free-flowing, democratic conversation. He cautions students against losing themselves down a narcissistic rabbit hole: you are not a “defrauded genius” simply because someone else has happened upon the same set of research questions. “You must overcome any shyness and have a conversation with the librarian,” he writes, “because he can offer you reliable advice that will save you much time. You must consider that the librarian (if not overworked or neurotic) is happy when he can demonstrate two things: the quality of his memory and erudition and the richness of his library, especially if it is small. The more isolated and disregarded the library, the more the librarian is consumed with sorrow for its underestimation.”

Eco captures a basic set of experiences and anxieties familiar to anyone who has written a thesis, from finding a mentor (“How to Avoid Being Exploited By Your Advisor”) to fighting through episodes of self-doubt. Ultimately, it’s the process and struggle that make a thesis a formative experience. When everything else you learned in college is marooned in the past—when you happen upon an old notebook and wonder what you spent all your time doing, since you have no recollection whatsoever of a senior-year postmodernism seminar—it is the thesis that remains, providing the once-mastered scholarly foundation that continues to authorize, decades-later, barroom observations about the late-career works of William Faulker or the Hotelling effect. (Full disclosure: I doubt that anyone on Earth can rival my mastery of John Travolta’s White Man’s Burden, owing to an idyllic Berkeley spring spent studying awful movies about race.)

In his foreword to Eco’s book, the scholar Francesco Erspamer contends that “How to Write a Thesis” continues to resonate with readers because it gets at “the very essence of the humanities.” There are certainly reasons to believe that the current crisis of the humanities owes partly to the poor job they do of explaining and justifying themselves. As critics continue to assail the prohibitive cost and possible uselessness of college—and at a time when anything that takes more than a few minutes to skim is called a “longread”—it’s understandable that devoting a small chunk of one’s frisky twenties to writing a thesis can seem a waste of time, outlandishly quaint, maybe even selfish. And, as higher education continues to bend to the logic of consumption and marketable skills, platitudes about pursuing knowledge for its own sake can seem certifiably bananas. Even from the perspective of the collegiate bureaucracy, the thesis is useful primarily as another mode of assessment, a benchmark of student achievement that’s legible and quantifiable. It’s also a great parting reminder to parents that your senior learned and achieved something.

But “How to Write a Thesis” is ultimately about much more than the leisurely pursuits of college students. Writing and research manuals such as “The Elements of Style,” “The Craft of Research,” and Turabian offer a vision of our best selves. They are exacting and exhaustive, full of protocols and standards that might seem pretentious, even strange. Acknowledging these rules, Eco would argue, allows the average person entry into a veritable universe of argument and discussion. “How to Write a Thesis,” then, isn’t just about fulfilling a degree requirement. It’s also about engaging difference and attempting a project that is seemingly impossible, humbly reckoning with “the knowledge that anyone can teach us something.” It models a kind of self-actualization, a belief in the integrity of one’s own voice.

A thesis represents an investment with an uncertain return, mostly because its life-changing aspects have to do with process. Maybe it’s the last time your most harebrained ideas will be taken seriously. Everyone deserves to feel this way. This is especially true given the stories from many college campuses about the comparatively lower number of women, first-generation students, and students of color who pursue optional thesis work. For these students, part of the challenge involves taking oneself seriously enough to ask for an unfamiliar and potentially path-altering kind of mentorship.

It’s worth thinking through Eco’s evocation of a “just society.” We might even think of the thesis, as Eco envisions it, as a formal version of the open-mindedness, care, rigor, and gusto with which we should greet every new day. It’s about committing oneself to a task that seems big and impossible. In the end, you won’t remember much beyond those final all-nighters, the gauche inside joke that sullies an acknowledgments page that only four human beings will ever read, the awkward photograph with your advisor at graduation. All that remains might be the sensation of handing your thesis to someone in the departmental office and then walking into a possibility-rich, almost-summer afternoon. It will be difficult to forget.

Books & Fiction

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Mary Norris

By Joshua Rothman

By Kathryn Schulz

By Merve Emre

How to Write a Thesis, According to Umberto Eco

In 1977, three years before Umberto Eco’s groundbreaking novel “ The Name of the Rose ” catapulted him to international fame, the illustrious semiotician published a funny and unpretentious guide for his favorite audience: teachers and their students. Now translated into 17 languages (it finally appeared in English in 2015), “How to Write a Thesis” delivers not just practical advice for writing a thesis — from choosing the right topic (monograph or survey? ancient or contemporary?) to note-taking and mastering the final draft — but meaningful lessons that equip writers for a lifetime outside the walls of the classroom. “Your thesis is like your first love” Eco muses. “It will be difficult to forget. In the end, it will represent your first serious and rigorous academic work, and this is no small thing.”

“Full of friendly, no-bullshit, entry-level advice on what to do and how to do it,” praised one critic, “the absolutely superb chapter on how to write is worth triple the price of admission on its own.” An excerpt from that chapter can be read below.

Once we have decided to whom to write (to humanity, not to the advisor), we must decide how to write, and this is quite a difficult question. If there were exhaustive rules, we would all be great writers. I could at least recommend that you rewrite your thesis many times, or that you take on other writing projects before embarking on your thesis, because writing is also a question of training. In any case, I will provide some general suggestions:

You are not Proust. Do not write long sentences. If they come into your head, write them, but then break them down. Do not be afraid to repeat the subject twice, and stay away from too many pronouns and subordinate clauses. Do not write,

The pianist Wittgenstein, brother of the well-known philosopher who wrote the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicusthat today many consider the masterpiece of contemporary philosophy, happened to have Ravel write for him a concerto for the left hand, since he had lost the right one in the war.

Write instead,

The pianist Paul Wittgenstein was the brother of the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. Since Paul was maimed of his right hand, the composer Maurice Ravel wrote a concerto for him that required only the left hand.

The pianist Paul Wittgenstein was the brother of the famous philosopher, author of the Tractatus. The pianist had lost his right hand in the war. For this reason the composer Maurice Ravel wrote a concerto for him that required only the left hand.

Do not write,

The Irish writer had renounced family, country, and church, and stuck to his plans. It can hardly be said of him that he was a politically committed writer, even if some have mentioned Fabian and “socialist” inclinations with respect to him. When World War II erupted, he tended to deliberately ignore the tragedy that shook Europe, and he was preoccupied solely with the writing of his last work.

Rather write,

Joyce had renounced family, country, and church. He stuck to his plans. We cannot say that Joyce was a “politically committed” writer even if some have gone so far as describing a Fabian and “socialist” Joyce. When World War II erupted, Joyce deliberately ignored the tragedy that shook Europe. His sole preoccupation was the writing of Finnegans Wake.

Even if it seems “literary,” please do not write,

When Stockhausen speaks of “clusters,” he does not have in mind Schoenberg’s series, or Webern’s series. If confronted, the German musician would not accept the requirement to avoid repeating any of the twelve notes before the series has ended. The notion of the cluster itself is structurally more unconventional than that of the series. On the other hand Webern followed the strict principles of the author of A Survivor from Warsaw. Now, the author of Mantra goes well beyond. And as for the former, it is necessary to distinguish between the various phases of his oeuvre. Berio agrees: it is not possible to consider this author as a dogmatic serialist.

You will notice that, at some point, you can no longer tell who is who. In addition, defining an author through one of his works is logically incorrect. It is true that lesser critics refer to Alessandro Manzoni simply as “the author of the Betrothed,” perhaps for fear of repeating his name too many times. (This is something manuals on formal writing apparently advise against.) But the author of The Betrothed is not the biographical character Manzoni in his totality. In fact, in a certain context we could say that there is a notable difference between the author of The Betrothed and the author of Adelchi , even if they are one and the same biographically speaking and according to their birth certificate. For this reason, I would rewrite the above passage as follows:

When Stockhausen speaks of a “cluster,” he does not have in mind either the series of Schoenberg or that of Webern. If confronted, Stockhausen would not accept the requirement to avoid repeating any of the twelve notes before the end of the series. The notion of the cluster itself is structurally more unconventional than that of the series. Webern, by contrast, followed the strict principles of Schoenberg, but Stockhausen goes well beyond. And even for Webern, it is necessary to distinguish among the various phases of his oeuvre. Berio also asserts that it is not possible to think of Webern as a dogmatic serialist.

You are not e. e. cummings. Cummings was an American avant-garde poet who is known for having signed his name with lower-case initials. Naturally he used commas and periods with great thriftiness, he broke his lines into small pieces, and in short he did all the things that an avant-garde poet can and should do. But you are not an avant-garde poet. Not even if your thesis is on avant-garde poetry. If you write a thesis on Caravaggio, are you then a painter? And if you write a thesis on the style of the futurists, please do not write as a futurist writes. This is important advice because nowadays many tend to write “alternative” theses, in which the rules of critical discourse are not respected. But the language of the thesis is a metalanguage , that is, a language that speaks of other languages. A psychiatrist who describes the mentally ill does not express himself in the manner of his patients. I am not saying that it is wrong to express oneself in the manner of the so-called mentally ill. In fact, you could reasonably argue that they are the only ones who express themselves the way one should. But here you have two choices: either you do not write a thesis, and you manifest your desire to break with tradition by refusing to earn your degree, perhaps learning to play the guitar instead; or you write your thesis, but then you must explain to everyone why the language of the mentally ill is not a “crazy” language, and to do it you must use a metalanguage intelligible to all. The pseudo-poet who writes his thesis in poetry is a pitiful writer (and probably a bad poet). From Dante to Eliot and from Eliot to Sanguineti, when avant-garde poets wanted to talk about their poetry, they wrote in clear prose. And when Marx wanted to talk about workers, he did not write as a worker of his time, but as a philosopher. Then, when he wrote The Communist Manifesto with Engels in 1848, he used a fragmented journalistic style that was provocative and quite effective. Yet again, The Communist Manifesto is not written in the style of Capital, a text addressed to economists and politicians. Do not pretend to be Dante by saying that the poetic fury “dictates deep within,” and that you cannot surrender to the flat and pedestrian metalanguage of literary criticism. Are you a poet? Then do not pursue a university degree. Twentieth-century Italian poet Eugenio Montale does not have a degree, and he is a great poet nonetheless. His contemporary Carlo Emilio Gadda (who held a degree in engineering) wrote fiction in a unique style, full of dialects and stylistic idiosyncrasies; but when he wrote a manual for radio news writers, he wrote a clever, sharp, and lucid “recipe book” full of clear and accessible prose. And when Montale writes a critical article, he writes so that all can understand him, including those who do not understand his poems.

Begin new paragraphs often. Do so when logically necessary, and when the pace of the text requires it, but the more you do it, the better.

Write everything that comes into your head , but only in the first draft. You may notice that you get carried away with your inspiration, and you lose track of the center of your topic. In this case, you can remove the parenthetical sentences and the digressions, or you can put each in a note or an appendix. Your thesis exists to prove the hypothesis that you devised at the outset, not to show the breadth of your knowledge.

Use the advisor as a guinea pig. You must ensure that the advisor reads the first chapters (and eventually, all the chapters) far in advance of the deadline. His reactions may be useful to you. If the advisor is busy (or lazy), ask a friend. Ask if he understands what you are writing. Do not play the solitary genius.

Do not insist on beginning with the first chapter . Perhaps you have more documentation on chapter 4. Start there, with the nonchalance of someone who has already worked out the previous chapters. You will gain confidence. Naturally your working table of contents will anchor you, and will serve as a hypothesis that guides you.

Do not use ellipsis and exclamation points, and do not explain ironies . It is possible to use language that is referential or language that is figurative . By referential language, I mean a language that is recognized by all, in which all things are called by their most common name, and that does not lend itself to misunderstandings. “The Venice-Milan train” indicates in a referential way the same object that “The Arrow of the Lagoon” indicates figuratively. This example illustrates that “everyday” communication is possible with partially figurative language. Ideally, a critical essay or a scholarly text should be written referentially (with all terms well defined and univocal), but it can also be useful to use metaphor, irony, or litotes. Here is a referential text, followed by its transcription in figurative terms that are at least tolerable:

[ Referential version :] Krasnapolsky is not a very sharp critic of Danieli’s work. His interpretation draws meaning from the author’s text that the author probably did not intend. Consider the line, “in the evening gazing at the clouds.” Ritz interprets this as a normal geographical annotation, whereas Krasnapolsky sees a symbolic expression that alludes to poetic activity. One should not trust Ritz’s critical acumen, and one should also distrust Krasnapolsky. Hilton observes that, “if Ritz’s writing seems like a tourist brochure, Krasnapolsky’s criticism reads like a Lenten sermon.” And he adds, “Truly, two perfect critics.”

[ Figurative version :] We are not convinced that Krasnapolsky is the sharpest critic of Danieli’s work. In reading his author, Krasnapolsky gives the impression that he is putting words into Danieli’s mouth. Consider the line, “in the evening gazing at the clouds.” Ritz interprets it as a normal geographical annotation, whereas Krasnapolsky plays the symbolism card and sees an allusion to poetic activity. Ritz is not a prodigy of critical insight, but Krasnapolsky should also be handled with care. As Hilton observes, “if Ritz’s writing seems like a tourist brochure, Krasnapolsky’s criticism reads like a Lenten sermon. Truly, two perfect critics.”

You can see that the figurative version uses various rhetorical devices. First of all, the litotes: saying that you are not convinced that someone is a sharp critic means that you are convinced that he is not a sharp critic. Also, the statement “Ritz is not a prodigy of critical insight” means that he is a modest critic. Then there are the metaphors : putting words into someone’s mouth, and playing the symbolism card. The tourist brochure and the Lenten sermon are two similes , while the observation that the two authors are perfect critics is an example of irony : saying one thing to signify its opposite.

Now, we either use rhetorical figures effectively, or we do not use them at all. If we use them it is because we presume our reader is capable of catching them, and because we believe that we will appear more incisive and convincing. In this case, we should not be ashamed of them, and we should not explain them . If we think that our reader is an idiot, we should not use rhetorical figures, but if we use them and feel the need to explain them, we are essentially calling the reader an idiot. In turn, he will take revenge by calling the author an idiot. Here is how a timid writer might intervene to neutralize and excuse the rhetorical figures he uses:

[ Figurative version with reservations :] We are not convinced that Krasnapolsky is the “sharpest” critic of Danieli’s work. In reading his author, Krasnapolsky gives the impression that he is “putting words into Danieli’s mouth.” Consider Danieli’s line, “in the evening gazing at the clouds.” Ritz interprets this as a normal geographical annotation, whereas Krasnapolsky “plays the symbolism card” and sees an allusion to poetic activity. Ritz is not a “prodigy of critical insight,” but Krasnapolsky should also be “handled with care”! As Hilton ironically observes, “if Ritz’s writing seems like a vacation brochure, Krasnapolsky’s criticism reads like a Lenten sermon.” And he defines them (again with irony!) as two models of critical perfection. But all joking aside …

I am convinced that nobody could be so intellectually petit bourgeois as to conceive a passage so studded with shyness and apologetic little smiles. Of course I exaggerated in this example, and here I say that I exaggerated because it is didactically important that the parody be understood as such. In fact, many bad habits of the amateur writer are condensed into this third example. First of all, the use of quotation marks to warn the reader, “Pay attention because I am about to say something big!” Puerile. Quotation marks are generally only used to designate a direct quotation or the title of an essay or short work; to indicate that a term is jargon or slang; or that a term is being discussed in the text as a word, rather than used functionally within the sentence. Secondly, the use of the exclamation point to emphasize a statement. This is not appropriate in a critical essay. If you check the book you are reading, you will notice that I have used the exclamation mark only once or twice. It is allowed once or twice, if the purpose is to make the reader jump in his seat and call his attention to a vehement statement like, “Pay attention, never make this mistake!” But it is a good rule to speak softly. The effect will be stronger if you simply say important things. Finally, the author of the third passage draws attention to the ironies, and apologizes for using them (even if they are someone else’s). Surely, if you think that Hilton’s irony is too subtle, you can write, “Hilton states with subtle irony that we are in the presence of two perfect critics.” But the irony must be really subtle to merit such a statement. In the quoted text, after Hilton has mentioned the vacation brochure and the Lenten sermon, the irony was already evident and needed no further explanation. The same applies to the statement, “But all joking aside.” Sometimes a statement like this can be useful to abruptly change the tone of the argument, but only if you were really joking before. In this case, the author was not joking. He was attempting to use irony and metaphor, but these are serious rhetorical devices and not jokes.

You may observe that, more than once in this book, I have expressed a paradox and then warned that it was a paradox. For example, in section 2.6.1, I proposed the existence of the mythical centaur for the purpose of explaining the concept of scientific research. But I warned you of this paradox not because I thought you would have believed this proposition. On the contrary, I warned you because I was afraid that you would have doubted too much, and hence dismissed the paradox. Therefore I insisted that, despite its paradoxical form, my statement contained an important truth: that research must clearly define its object so that others can identify it, even if this object is mythical. And I made this absolutely clear because this is a didactic book in which I care more that everyone understands what I want to say than about a beautiful literary style. Had I been writing an essay, I would have pronounced the paradox without denouncing it later.

Always define a term when you introduce it for the first time . If you do not know the definition of a term, avoid using it. If it is one of the principal terms of your thesis and you are not able to define it, call it quits. You have chosen the wrong thesis (or, if you were planning to pursue further research, the wrong career).

Umberto Eco was an Italian novelist, literary critic, philosopher, semiotician, and university professor. This article is excerpted from his book “ How to Write a Thesis .”

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

How to Write a Master's Thesis

- Yvonne N. Bui - San Francisco State University, USA

- Description

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

“Yvonne Bui’s How to Write a Master’s Thesis should be mandatory for all thesis track master’s students. It steers students away from the shortcuts students may be tempted to use that would be costly in the long run. The step by step intentional approach is what I like best about this book.”

“This is the best textbook about writing an M.A. thesis available in the market.”

“This is the type of textbook that students keep and refer to after the class.”

Excellent book. Thorough, yet concise, information for students writing their Master's Thesis who may not have had a strong background in research.

Clear, Concise, easy for students to access and understand. Contains all the elements for a successful thesis.

I loved the ease of this book. It was clear without extra nonsense that would just confuse the students.

Clear, concise, easily accessible. Students find it of great value.

NEW TO THIS EDITION:

- Concrete instruction and guides for conceptualizing the literature review help students navigate through the most challenging topics.

- Step-by-step instructions and more screenshots give students the guidance they need to write the foundational chapter, along with the latest online resources and general library information.

- Additional coverage of single case designs and mixed methods help students gain a more comprehensive understanding of research methods.

- Expanded explanation of unintentional plagiarism within the ethics chapter shows students the path to successful and professional writing.

- Detailed information on conference presentation as a way to disseminate research , in addition to getting published, help students understand all of the tools needed to write a master’s thesis.

KEY FEATURES:

- An advanced chapter organizer provides an up-front checklist of what to expect in the chapter and serves as a project planner, so that students can immediately prepare and work alongside the chapter as they begin to develop their thesis.

- Full guidance on conducting successful literature reviews includes up-to-date information on electronic databases and Internet tools complete with numerous figures and captured screen shots from relevant web sites, electronic databases, and SPSS software, all integrated with the text.

- Excerpts from research articles and samples from exemplary students' master's theses relate specifically to the content of each chapter and provide the reader with a real-world context.

- Detailed explanations of the various components of the master's thesis and concrete strategies on how to conduct a literature review help students write each chapter of the master's thesis, and apply the American Psychological Association (APA) editorial style.

- A comprehensive Resources section features "Try It!" boxes which lead students through a sample problem or writing exercise based on a piece of the thesis to reinforce prior course learning and the writing objectives at hand. Reflection/discussion questions in the same section are designed to help students work through the thesis process.

Sample Materials & Chapters

1: Overview of the Master's Degree and Thesis

3: Using the Literature to Research Your Problem

For instructors

Select a purchasing option, related products.

The best two books on doing a thesis

I started my PhD at the University of Melbourne in early 2006 and finished in 2009. I did well, collecting the John Grice Award for best thesis in my faculty and coming second for the university medal (dammit!). I attribute this success to two ‘how to’ books in particular: Evans and Gruba’s “How to write a better thesis” and Kamler and Thomson’s “Helping doctoral students write” , both of which recently went into their second edition.

I picked up “How to write a better thesis” from the RMIT campus bookstore in June, 2004. I met this book at a particularly dark time in my first thesis journey. I did my masters by creative practice at RMIT, which meant I made a heap of stuff and then had to write about it. The making bit was fun, but the writing was agony.

My poor supervisors did their best to help me revise draft after draft, but I was terrible at it. Nothing in my previous study in architecture had prepared me for writing a proper essay, let alone a long thesis. I had no idea what one should even look like. What sections should I have? What does each one do? In desperation, I visited the bookstore and “How to write a better thesis” jumped off the rack and into my arms.

I’ll admit, my choice was largely informed by its student friendly price point : at the time it was $21.95, it’s now gone up to around $36. In my opinion that’s a bit steep, given that the average student budget is still as constrained as it was a decade ago, but you do get a lot for your money.

David Evans sadly died some years ago, but Justin Zobel has ably stepped into his shoes for the revision. What I’ve always liked best about this book is the way it breaks the ‘standard thesis’ down into its various components: introduction, literature review, method etc, then treats the problems of each separately. This enables you to use it tactically to ‘spot check’ for problem areas in your thesis.

The new edition of the book has remained essentially the same, but with some useful additions that, I think, better reflect the complexity of the contemporary thesis landscape. It acknowledges a broader spread of difficulties with writing the thesis and includes worked examples which illustrate the various traps students can fall into.

A couple of weeks ago I was sent a review copy of Zobel and Gruba’s new collaboration: “How to write a better Minor Thesis” . This is a stripped down version of the original book, with some minor additions, but designed specifically for masters by course work and honours students who have to write a thesis between 15,000 and 30,000 in length. It’s a brilliant idea as, to my knowledge, there hasn’t been much on the market for these students before. The majority of the book is relevant to the PhD and since it’s only $9.95 on Kindle you might want to start with this instead and upgrade to the more expensive paperback if you think you want more.

My introduction to Barbara Kamler and Pat Thomson’s “Helping doctoral students to write: pedagogies for supervision” was quite different. My colleague at the time, Dr Robyn Barnacle, handed me this book when I was in the first year of my PhD. By that time I was a much more confident writer and I was ready for the more complex writing journey this book offered. And “Helping doctoral students to write” does tackle complicated issues – nominalisation, modality, them/rheme analysis and so on – but not in a complicated way. This is largely because it’s full of practical exercises and suggestions, many of which I use in my workshops (for an example, see this slide deck on treating the zombie thesis ).

Although “Helping doctoral students write” has more of a humanities bent than ‘how to write a thesis’, it steps through a broad range of thesis writing issues with a light touch that never makes you feel bored or frustrated. It argues that the thesis is a genre proposition – an amazingly powerful insight – and the chapter on grammar is simply a work of brilliance.

I’ve given this book to engineers, architects, biologists and musicologists, all of whom have told me it was useful – but I find total beginners react with fear to sub-headings like ‘modality: the goldilocks dilemma’. For that reason I usually save it for students near their final year, especially when they tell me their supervisor doesn’t like their writing, but can’t explain why.

“Helping doctoral students to write” is not explicitly written for PhD students (the authors are in the process of doing one). The new edition is an improvement on the old in many ways and well worth buying again if you happen to own it already. The new edition is around $42, which is ok but I think the Kindle edition is over priced (why do publishers keep doing this when many people like to own both for convenience?). It’s a great book for the advanced student who is prepared to roll up their sleeves and do some serious work. Not only will this work pay dividends, as my award attests, it will stand you in good stead for being a supervisor yourself later on as you will be able to diagnose and treat some of the most common – yet difficult to describe – writing problems.

Pat Thomson, is, of course, the author of the popular ‘Patter’ blog , so you can access her wisdom, for free, on a weekly basis. I should own up to the fact that Pat and I met on Twitter, as many bloggers do, and started to collaborate. I’m still in awe of Pat’s knowledge, experience and good humour. I sometimes pinch myself that we have become friends (in fact, she gave me my new copy of the book when I last visited the UK), but I hope this isn’t the only reason the new edition mentions the Whisperer in one of the chapters (squee!).

If I hadn’t already had deep familiarity with this book before I met Pat I would definitely have to say I have a conflict of interest, but I can hand on my heart tell you I would recommend it anyway. Pat and Barbara have written another, truly fantastic, book “Writing for peer review journals: strategies for getting published” but that’s a review for another time 🙂

Have you read these books? Or any others that you think have significantly helped you on your PhD journey? Love to hear about them in the comments.

Other book reviews on the Whisperer

How to write a lot

BITE: recipes for remarkable research

Study skills for international postgraduates

Doing your dissertation with Microsoft Word

How to fail your Viva

Mapping your thesis

Demystifying dissertation writing

If you have a book you would like us to review, please email me.

Share this:

The Thesis Whisperer is written by Professor Inger Mewburn, director of researcher development at The Australian National University . New posts on the first Wednesday of the month. Subscribe by email below. Visit the About page to find out more about me, my podcasts and books. I'm on most social media platforms as @thesiswhisperer. The best places to talk to me are LinkedIn , Mastodon and Threads.

- Post (606)

- Page (16)

- Product (6)

- Getting things done (258)

- On Writing (138)

- Miscellany (137)

- Your Career (113)

- You and your supervisor (66)

- Writing (48)

- productivity (23)

- consulting (13)

- TWC (13)

- supervision (12)

- 2024 (5)

- 2023 (12)

- 2022 (11)

- 2021 (15)

- 2020 (22)

Whisper to me....

Enter your email address to get posts by email.

Email Address

Sign me up!

- On the reg: a podcast with @jasondowns

- Thesis Whisperer on Facebook

- Thesis Whisperer on Instagram

- Thesis Whisperer on Soundcloud

- Thesis Whisperer on Youtube

- Thesiswhisperer on Mastodon

- Thesiswhisperer page on LinkedIn

- Thesiswhisperer Podcast

- 12,128,637 hits

Discover more from The Thesis Whisperer

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Think of yourself as a member of a jury, listening to a lawyer who is presenting an opening argument. You'll want to know very soon whether the lawyer believes the accused to be guilty or not guilty, and how the lawyer plans to convince you. Readers of academic essays are like jury members: before they have read too far, they want to know what the essay argues as well as how the writer plans to make the argument. After reading your thesis statement, the reader should think, "This essay is going to try to convince me of something. I'm not convinced yet, but I'm interested to see how I might be."

An effective thesis cannot be answered with a simple "yes" or "no." A thesis is not a topic; nor is it a fact; nor is it an opinion. "Reasons for the fall of communism" is a topic. "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe" is a fact known by educated people. "The fall of communism is the best thing that ever happened in Europe" is an opinion. (Superlatives like "the best" almost always lead to trouble. It's impossible to weigh every "thing" that ever happened in Europe. And what about the fall of Hitler? Couldn't that be "the best thing"?)

A good thesis has two parts. It should tell what you plan to argue, and it should "telegraph" how you plan to argue—that is, what particular support for your claim is going where in your essay.

Steps in Constructing a Thesis

First, analyze your primary sources. Look for tension, interest, ambiguity, controversy, and/or complication. Does the author contradict himself or herself? Is a point made and later reversed? What are the deeper implications of the author's argument? Figuring out the why to one or more of these questions, or to related questions, will put you on the path to developing a working thesis. (Without the why, you probably have only come up with an observation—that there are, for instance, many different metaphors in such-and-such a poem—which is not a thesis.)

Once you have a working thesis, write it down. There is nothing as frustrating as hitting on a great idea for a thesis, then forgetting it when you lose concentration. And by writing down your thesis you will be forced to think of it clearly, logically, and concisely. You probably will not be able to write out a final-draft version of your thesis the first time you try, but you'll get yourself on the right track by writing down what you have.

Keep your thesis prominent in your introduction. A good, standard place for your thesis statement is at the end of an introductory paragraph, especially in shorter (5-15 page) essays. Readers are used to finding theses there, so they automatically pay more attention when they read the last sentence of your introduction. Although this is not required in all academic essays, it is a good rule of thumb.

Anticipate the counterarguments. Once you have a working thesis, you should think about what might be said against it. This will help you to refine your thesis, and it will also make you think of the arguments that you'll need to refute later on in your essay. (Every argument has a counterargument. If yours doesn't, then it's not an argument—it may be a fact, or an opinion, but it is not an argument.)

This statement is on its way to being a thesis. However, it is too easy to imagine possible counterarguments. For example, a political observer might believe that Dukakis lost because he suffered from a "soft-on-crime" image. If you complicate your thesis by anticipating the counterargument, you'll strengthen your argument, as shown in the sentence below.

Some Caveats and Some Examples

A thesis is never a question. Readers of academic essays expect to have questions discussed, explored, or even answered. A question ("Why did communism collapse in Eastern Europe?") is not an argument, and without an argument, a thesis is dead in the water.

A thesis is never a list. "For political, economic, social and cultural reasons, communism collapsed in Eastern Europe" does a good job of "telegraphing" the reader what to expect in the essay—a section about political reasons, a section about economic reasons, a section about social reasons, and a section about cultural reasons. However, political, economic, social and cultural reasons are pretty much the only possible reasons why communism could collapse. This sentence lacks tension and doesn't advance an argument. Everyone knows that politics, economics, and culture are important.

A thesis should never be vague, combative or confrontational. An ineffective thesis would be, "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe because communism is evil." This is hard to argue (evil from whose perspective? what does evil mean?) and it is likely to mark you as moralistic and judgmental rather than rational and thorough. It also may spark a defensive reaction from readers sympathetic to communism. If readers strongly disagree with you right off the bat, they may stop reading.

An effective thesis has a definable, arguable claim. "While cultural forces contributed to the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe, the disintegration of economies played the key role in driving its decline" is an effective thesis sentence that "telegraphs," so that the reader expects the essay to have a section about cultural forces and another about the disintegration of economies. This thesis makes a definite, arguable claim: that the disintegration of economies played a more important role than cultural forces in defeating communism in Eastern Europe. The reader would react to this statement by thinking, "Perhaps what the author says is true, but I am not convinced. I want to read further to see how the author argues this claim."

A thesis should be as clear and specific as possible. Avoid overused, general terms and abstractions. For example, "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe because of the ruling elite's inability to address the economic concerns of the people" is more powerful than "Communism collapsed due to societal discontent."

Copyright 1999, Maxine Rodburg and The Tutors of the Writing Center at Harvard University

How to Write a Thesis

Umberto Eco was an Italian semiotician, philosopher, literary critic, and novelist. He is the author of The Name of the Rose, Foucault's Pendulum , and The Prague Cemetery , all bestsellers in many languages, as well as a number of influential scholarly works.

Umberto Eco's wise and witty guide to researching and writing a thesis, published in English for the first time.

By the time Umberto Eco published his best-selling novel The Name of the Rose , he was one of Italy's most celebrated intellectuals, a distinguished academic and the author of influential works on semiotics. Some years before that, in 1977, Eco published a little book for his students, How to Write a Thesis , in which he offered useful advice on all the steps involved in researching and writing a thesis—from choosing a topic to organizing a work schedule to writing the final draft. Now in its twenty-third edition in Italy and translated into seventeen languages, How to Write a Thesis has become a classic. Remarkably, this is its first, long overdue publication in English.

Eco's approach is anything but dry and academic. He not only offers practical advice but also considers larger questions about the value of the thesis-writing exercise. How to Write a Thesis is unlike any other writing manual. It reads like a novel. It is opinionated. It is frequently irreverent, sometimes polemical, and often hilarious. Eco advises students how to avoid “thesis neurosis” and he answers the important question “Must You Read Books?” He reminds students “You are not Proust” and “Write everything that comes into your head, but only in the first draft.” Of course, there was no Internet in 1977, but Eco's index card research system offers important lessons about critical thinking and information curating for students of today who may be burdened by Big Data.

How to Write a Thesis belongs on the bookshelves of students, teachers, writers, and Eco fans everywhere. Already a classic, it would fit nicely between two other classics: Strunk and White and The Name of the Rose .

Contents The Definition and Purpose of a Thesis • Choosing the Topic • Conducting Research • The Work Plan and the Index Cards • Writing the Thesis • The Final Draft

- Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

How to Write a Thesis By: Umberto Eco, Caterina Mongiat Farina, Geoff Farina https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/10029.001.0001 ISBN (electronic): 9780262328753 Publisher: The MIT Press Published: 2015

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Table of Contents

- [ Front Matter ] Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/10029.003.0013 Open the PDF Link PDF for [ Front Matter ] in another window

- Foreword By Francesco Erspamer Francesco Erspamer Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/10029.003.0001 Open the PDF Link PDF for Foreword in another window

- Translators' Foreword By Caterina Mongiat Farina , Caterina Mongiat Farina Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Geoff Farina Geoff Farina Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/10029.003.0002 Open the PDF Link PDF for Translators' Foreword in another window

- Introduction to the Original 1977 Edition Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/10029.003.0003 Open the PDF Link PDF for Introduction to the Original 1977 Edition in another window

- Introduction to the 1985 Edition Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/10029.003.0004 Open the PDF Link PDF for Introduction to the 1985 Edition in another window

- 1: The Definition and Purpose of the Thesis Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/10029.003.0005 Open the PDF Link PDF for 1: The Definition and Purpose of the Thesis in another window

- 2: Choosing the Topic Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/10029.003.0006 Open the PDF Link PDF for 2: Choosing the Topic in another window

- 3: Conducting Research Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/10029.003.0007 Open the PDF Link PDF for 3: Conducting Research in another window

- 4: The Work Plan and the Index Cards Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/10029.003.0008 Open the PDF Link PDF for 4: The Work Plan and the Index Cards in another window

- 5: Writing the Thesis Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/10029.003.0009 Open the PDF Link PDF for 5: Writing the Thesis in another window

- 6: The Final Draft Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/10029.003.0010 Open the PDF Link PDF for 6: The Final Draft in another window

- 7: Conclusions Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/10029.003.0011 Open the PDF Link PDF for 7: Conclusions in another window

- Notes Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/10029.003.0012 Open the PDF Link PDF for Notes in another window

- Open Access

A product of The MIT Press

Mit press direct.

- About MIT Press Direct

Information

- Accessibility

- For Authors

- For Customers

- For Librarians

- Direct to Open

- Media Inquiries

- Rights and Permissions

- For Advertisers

- About the MIT Press

- The MIT Press Reader

- MIT Press Blog

- Seasonal Catalogs

- MIT Press Home

- Give to the MIT Press

- Direct Service Desk

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Statement

- Crossref Member

- COUNTER Member

- The MIT Press colophon is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

How To Write Your First Thesis

- © 2017

- Paul Gruba 0 ,

- Justin Zobel 1

School of Languages & Linguistics, University of Melbourne SLL, Babel Bldg 608, Melbourne, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

School of Computing & Information Systems, University of Melbourne Comp. Science & Software Engg., Carlton, VIC, Australia

- A practical guide for the entire process of producing a thesis for the first time

- Written by authors with many years of experience advising students

- Provides grounded advice to students who are new to writing extended original research, either undergraduate or graduate coursework

57k Accesses

3 Citations

10 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

Table of contents (9 chapters)

Front matter, transition to your first thesis.

- Paul Gruba, Justin Zobel

Getting Organized

The structure of a thesis, a strong beginning: the introduction, situating the study: the background, explaining the investigation: methods and innovations, presenting the outcome: the results, wrapping it up: discussion and conclusion, before you submit, back matter.

- research writing

- thesis preparation

- dissertation writing

- final project preparation

- thesis structure

- learning and instruction

About this book

Many courses and degrees require that students write a short thesis. This book guides students through their first experience of producing a thesis and undertaking original research. Written by experienced researchers and advisors, the book sets out signposts and tasks to help students to understand what is needed to succeed, including scoping a topic, managing references, interpreting data, and successful completion.

For students, the task of writing a thesis is a transition from structured coursework to becoming a researcher. The book provides advice on:

- What to expect from research and how to work with a supervisor

- Getting organized and approaching the work in a productive way

- Developing an overall thesis structure and avoidance of mistakes such as inadvertent plagiarism

- Producing each major component: a strong introduction, background chapters that are situated in the discipline, and an explanation ofmethods and results that are crucial to successful original research

- How to wrap up a complex project with an extended checklist of the many details needed to be checked before a final submission

Authors and Affiliations

School of languages & linguistics, university of melbourne sll, babel bldg 608, melbourne, australia, school of computing & information systems, university of melbourne comp. science & software engg., carlton, vic, australia.

Justin Zobel

About the authors

Paul Gruba is Associate Professor in the School of Languages and Linguistics, University of Melbourne.

Justin Zobel is Professor in the School of Computing & Information Systems, University of Melbourne.

Bibliographic Information

Book Title : How To Write Your First Thesis

Authors : Paul Gruba, Justin Zobel

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61854-8

Publisher : Springer Cham

eBook Packages : Computer Science , Computer Science (R0)

Copyright Information : Springer International Publishing AG 2017

Softcover ISBN : 978-3-319-61853-1 Published: 06 September 2017

eBook ISBN : 978-3-319-61854-8 Published: 24 August 2017

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XIII, 95

Number of Illustrations : 8 b/w illustrations

Topics : Computer Science, general , Learning & Instruction , Natural Language Processing (NLP) , Popular Social Sciences , Science, Humanities and Social Sciences, multidisciplinary

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

How to write a PhD thesis: a step-by-step guide

A draft isn’t a perfect, finished product; it is your opportunity to start getting words down on paper, writes Kelly Louise Preece

Kelly Louise Preece

Created in partnership with

You may also like

Popular resources

.css-1txxx8u{overflow:hidden;max-height:81px;text-indent:0px;} How to develop a researcher mindset as a PhD student

Formative, summative or diagnostic assessment a guide, emotions and learning: what role do emotions play in how and why students learn, how to assess and enhance students’ ai literacy, how hard can it be testing ai detection tools.

Congratulations; you’ve finished your research! Time to write your PhD thesis. This resource will take you through an eight-step plan for drafting your chapters and your thesis as a whole.

Organise your material

Before you start, it’s important to get organised. Take a step back and look at the data you have, then reorganise your research. Which parts of it are central to your thesis and which bits need putting to one side? Label and organise everything using logical folders – make it easy for yourself! Academic and blogger Pat Thomson calls this “Clean up to get clearer” . Thomson suggests these questions to ask yourself before you start writing:

- What data do you have? You might find it useful to write out a list of types of data (your supervisor will find this list useful too.) This list is also an audit document that can go in your thesis. Do you have any for the “cutting room floor”? Take a deep breath and put it in a separate non-thesis file. You can easily retrieve it if it turns out you need it.

- What do you have already written? What chunks of material have you written so far that could form the basis of pieces of the thesis text? They will most likely need to be revised but they are useful starting points. Do you have any holding text? That is material you already know has to be rewritten but contains information that will be the basis of a new piece of text.

- What have you read and what do you still need to read? Are there new texts that you need to consult now after your analysis? What readings can you now put to one side, knowing that they aren’t useful for this thesis – although they might be useful at another time?

- What goes with what? Can you create chunks or themes of materials that are going to form the basis of some chunks of your text, perhaps even chapters?

Once you have assessed and sorted what you have collected and generated you will be in much better shape to approach the big task of composing the dissertation.

Decide on a key message

A key message is a summary of new information communicated in your thesis. You should have started to map this out already in the section on argument and contribution – an overarching argument with building blocks that you will flesh out in individual chapters.

You have already mapped your argument visually, now you need to begin writing it in prose. Following another of Pat Thomson’s exercises, write a “tiny text” thesis abstract. This doesn’t have to be elegant, or indeed the finished product, but it will help you articulate the argument you want your thesis to make. You create a tiny text using a five-paragraph structure:

- The first sentence addresses the broad context. This locates the study in a policy, practice or research field.

- The second sentence establishes a problem related to the broad context you have set out. It often starts with “But”, “Yet” or “However”.

- The third sentence says what specific research has been done. This often starts with “This research” or “I report…”

- The fourth sentence reports the results. Don’t try to be too tricky here, just start with something like: “This study shows,” or “Analysis of the data suggests that…”

- The fifth and final sentence addresses the “So What?” question and makes clear the claim to contribution.

Here’s an example that Thomson provides:

Secondary school arts are in trouble, as the fall in enrolments in arts subjects dramatically attests. However, there is patchy evidence about the benefits of studying arts subjects at school and this makes it hard to argue why the drop in arts enrolments matters. This thesis reports on research which attempts to provide some answers to this problem – a longitudinal study which followed two groups of senior secondary students, one group enrolled in arts subjects and the other not, for three years. The results of the study demonstrate the benefits of young people’s engagement in arts activities, both in and out of school, as well as the connections between the two. The study not only adds to what is known about the benefits of both formal and informal arts education but also provides robust evidence for policymakers and practitioners arguing for the benefits of the arts. You can find out more about tiny texts and thesis abstracts on Thomson’s blog.

- Writing tips for higher education professionals

- Resource collection on academic writing

- What is your academic writing temperament?

Write a plan

You might not be a planner when it comes to writing. You might prefer to sit, type and think through ideas as you go. That’s OK. Everybody works differently. But one of the benefits of planning your writing is that your plan can help you when you get stuck. It can help with writer’s block (more on this shortly!) but also maintain clarity of intention and purpose in your writing.

You can do this by creating a thesis skeleton or storyboard , planning the order of your chapters, thinking of potential titles (which may change at a later stage), noting down what each chapter/section will cover and considering how many words you will dedicate to each chapter (make sure the total doesn’t exceed the maximum word limit allowed).

Use your plan to help prompt your writing when you get stuck and to develop clarity in your writing.

Some starting points include:

- This chapter will argue that…

- This section illustrates that…

- This paragraph provides evidence that…

Of course, we wish it werethat easy. But you need to approach your first draft as exactly that: a draft. It isn’t a perfect, finished product; it is your opportunity to start getting words down on paper. Start with whichever chapter you feel you want to write first; you don’t necessarily have to write the introduction first. Depending on your research, you may find it easier to begin with your empirical/data chapters.

Vitae advocates for the “three draft approach” to help with this and to stop you from focusing on finding exactly the right word or transition as part of your first draft.

This resource originally appeared on Researcher Development .

Kelly Louse Preece is head of educator development at the University of Exeter.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter .

How to develop a researcher mindset as a PhD student

A diy guide to starting your own journal, contextual learning: linking learning to the real world, what does a university faculty senate do, hybrid learning through podcasts: a practical approach, how exactly does research get funded.

Register for free

and unlock a host of features on the THE site

Library Subject Guides

4. writing up your research: books on thesis writing.

- Books on Thesis Writing

- Thesis Formatting (MS Word)

- Referencing

Other Research Support Guides 1. Plan (Design and Discover) your Research >> 2. Find & Manage Research Literature >> 3. Doing the Research >> 5. Publish & Share >> 6. Measure Impact

Your dissertation may be the longest piece of writing you have ever done, but there are ways to approach it that will help to make it less overwhelming.

Write up as you go along. It is much easier to keep track of how your ideas develop and writing helps clarify your thinking. It also saves having to churn out 1000s of words at the end.

You don't have to start with the introduction – start at the chapter that seems the easiest to write – this could be the literature review or methodology, for example.

Alternatively you may prefer to write the introduction first, so you can get your ideas straight. Decide what will suit your ways of working best - then do it.

Think of each chapter as an essay in itself – it should have a clear introduction and conclusion. Use the conclusion to link back to the overall research question.

Think of the main argument of your dissertation as a river, and each chapter is a tributary feeding into this. The individual chapters will contain their own arguments, and go their own way, but they all contribute to the main flow.

Write a chapter, read it and do a redraft - then move on. This stops you from getting bogged down in one chapter.

Write your references properly and in full from the beginning.

Keep your word count in mind – be ruthless and don't write anything that isn't relevant. It's often easier to add information, than have to cut down a long chapter that you've slaved over for hours.

Save your work! Remember to save your work frequently to somewhere you can access it easily. It's a good idea to at least save a copy to a cloud-based service like Google Docs or Dropbox so that you can access it from any computer - if you only save to your own PC, laptop or tablet, you could lose everything if you lose or break your device.

E-books on thesis writing

Who to Contact

Nick scullin, phone: +6433693904, find more books.

Try the following subject headings to search UC library catalogue for books on thesis writing

More books on writing theses

Dissertations, Academic

Dissertations, Academic -- Authorship

Dissertations, Academic -- Handbooks, manuals ,

Academic writing

Academic writing -- Handbooks, manuals ,

Report writing

Technical writing

How to Cite Sources

Here is a complete list for how to cite sources. Most of these guides present citation guidance and examples in MLA, APA, and Chicago.

If you’re looking for general information on MLA or APA citations , the EasyBib Writing Center was designed for you! It has articles on what’s needed in an MLA in-text citation , how to format an APA paper, what an MLA annotated bibliography is, making an MLA works cited page, and much more!

MLA Format Citation Examples

The Modern Language Association created the MLA Style, currently in its 9th edition, to provide researchers with guidelines for writing and documenting scholarly borrowings. Most often used in the humanities, MLA style (or MLA format ) has been adopted and used by numerous other disciplines, in multiple parts of the world.

MLA provides standard rules to follow so that most research papers are formatted in a similar manner. This makes it easier for readers to comprehend the information. The MLA in-text citation guidelines, MLA works cited standards, and MLA annotated bibliography instructions provide scholars with the information they need to properly cite sources in their research papers, articles, and assignments.

- Book Chapter

- Conference Paper

- Documentary

- Encyclopedia

- Google Images

- Kindle Book

- Memorial Inscription

- Museum Exhibit

- Painting or Artwork

- PowerPoint Presentation

- Sheet Music

- Thesis or Dissertation

- YouTube Video

APA Format Citation Examples

The American Psychological Association created the APA citation style in 1929 as a way to help psychologists, anthropologists, and even business managers establish one common way to cite sources and present content.

APA is used when citing sources for academic articles such as journals, and is intended to help readers better comprehend content, and to avoid language bias wherever possible. The APA style (or APA format ) is now in its 7th edition, and provides citation style guides for virtually any type of resource.

Chicago Style Citation Examples

The Chicago/Turabian style of citing sources is generally used when citing sources for humanities papers, and is best known for its requirement that writers place bibliographic citations at the bottom of a page (in Chicago-format footnotes ) or at the end of a paper (endnotes).

The Turabian and Chicago citation styles are almost identical, but the Turabian style is geared towards student published papers such as theses and dissertations, while the Chicago style provides guidelines for all types of publications. This is why you’ll commonly see Chicago style and Turabian style presented together. The Chicago Manual of Style is currently in its 17th edition, and Turabian’s A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations is in its 8th edition.

Citing Specific Sources or Events

- Declaration of Independence

- Gettysburg Address

- Martin Luther King Jr. Speech

- President Obama’s Farewell Address

- President Trump’s Inauguration Speech

- White House Press Briefing

Additional FAQs

- Citing Archived Contributors

- Citing a Blog

- Citing a Book Chapter

- Citing a Source in a Foreign Language

- Citing an Image

- Citing a Song

- Citing Special Contributors

- Citing a Translated Article

- Citing a Tweet

6 Interesting Citation Facts

The world of citations may seem cut and dry, but there’s more to them than just specific capitalization rules, MLA in-text citations , and other formatting specifications. Citations have been helping researches document their sources for hundreds of years, and are a great way to learn more about a particular subject area.

Ever wonder what sets all the different styles apart, or how they came to be in the first place? Read on for some interesting facts about citations!

1. There are Over 7,000 Different Citation Styles

You may be familiar with MLA and APA citation styles, but there are actually thousands of citation styles used for all different academic disciplines all across the world. Deciding which one to use can be difficult, so be sure to ask you instructor which one you should be using for your next paper.

2. Some Citation Styles are Named After People

While a majority of citation styles are named for the specific organizations that publish them (i.e. APA is published by the American Psychological Association, and MLA format is named for the Modern Language Association), some are actually named after individuals. The most well-known example of this is perhaps Turabian style, named for Kate L. Turabian, an American educator and writer. She developed this style as a condensed version of the Chicago Manual of Style in order to present a more concise set of rules to students.

3. There are Some Really Specific and Uniquely Named Citation Styles

How specific can citation styles get? The answer is very. For example, the “Flavour and Fragrance Journal” style is based on a bimonthly, peer-reviewed scientific journal published since 1985 by John Wiley & Sons. It publishes original research articles, reviews and special reports on all aspects of flavor and fragrance. Another example is “Nordic Pulp and Paper Research,” a style used by an international scientific magazine covering science and technology for the areas of wood or bio-mass constituents.

4. More citations were created on EasyBib.com in the first quarter of 2018 than there are people in California.

The US Census Bureau estimates that approximately 39.5 million people live in the state of California. Meanwhile, about 43 million citations were made on EasyBib from January to March of 2018. That’s a lot of citations.

5. “Citations” is a Word With a Long History

The word “citations” can be traced back literally thousands of years to the Latin word “citare” meaning “to summon, urge, call; put in sudden motion, call forward; rouse, excite.” The word then took on its more modern meaning and relevance to writing papers in the 1600s, where it became known as the “act of citing or quoting a passage from a book, etc.”

6. Citation Styles are Always Changing

The concept of citations always stays the same. It is a means of preventing plagiarism and demonstrating where you relied on outside sources. The specific style rules, however, can and do change regularly. For example, in 2018 alone, 46 new citation styles were introduced , and 106 updates were made to exiting styles. At EasyBib, we are always on the lookout for ways to improve our styles and opportunities to add new ones to our list.

Why Citations Matter

Here are the ways accurate citations can help your students achieve academic success, and how you can answer the dreaded question, “why should I cite my sources?”

They Give Credit to the Right People

Citing their sources makes sure that the reader can differentiate the student’s original thoughts from those of other researchers. Not only does this make sure that the sources they use receive proper credit for their work, it ensures that the student receives deserved recognition for their unique contributions to the topic. Whether the student is citing in MLA format , APA format , or any other style, citations serve as a natural way to place a student’s work in the broader context of the subject area, and serve as an easy way to gauge their commitment to the project.

They Provide Hard Evidence of Ideas

Having many citations from a wide variety of sources related to their idea means that the student is working on a well-researched and respected subject. Citing sources that back up their claim creates room for fact-checking and further research . And, if they can cite a few sources that have the converse opinion or idea, and then demonstrate to the reader why they believe that that viewpoint is wrong by again citing credible sources, the student is well on their way to winning over the reader and cementing their point of view.

They Promote Originality and Prevent Plagiarism

The point of research projects is not to regurgitate information that can already be found elsewhere. We have Google for that! What the student’s project should aim to do is promote an original idea or a spin on an existing idea, and use reliable sources to promote that idea. Copying or directly referencing a source without proper citation can lead to not only a poor grade, but accusations of academic dishonesty. By citing their sources regularly and accurately, students can easily avoid the trap of plagiarism , and promote further research on their topic.

They Create Better Researchers

By researching sources to back up and promote their ideas, students are becoming better researchers without even knowing it! Each time a new source is read or researched, the student is becoming more engaged with the project and is developing a deeper understanding of the subject area. Proper citations demonstrate a breadth of the student’s reading and dedication to the project itself. By creating citations, students are compelled to make connections between their sources and discern research patterns. Each time they complete this process, they are helping themselves become better researchers and writers overall.

When is the Right Time to Start Making Citations?

Make in-text/parenthetical citations as you need them.

As you are writing your paper, be sure to include references within the text that correspond with references in a works cited or bibliography. These are usually called in-text citations or parenthetical citations in MLA and APA formats. The most effective time to complete these is directly after you have made your reference to another source. For instance, after writing the line from Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities : “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…,” you would include a citation like this (depending on your chosen citation style):

(Dickens 11).

This signals to the reader that you have referenced an outside source. What’s great about this system is that the in-text citations serve as a natural list for all of the citations you have made in your paper, which will make completing the works cited page a whole lot easier. After you are done writing, all that will be left for you to do is scan your paper for these references, and then build a works cited page that includes a citation for each one.

Need help creating an MLA works cited page ? Try the MLA format generator on EasyBib.com! We also have a guide on how to format an APA reference page .

2. Understand the General Formatting Rules of Your Citation Style Before You Start Writing

While reading up on paper formatting may not sound exciting, being aware of how your paper should look early on in the paper writing process is super important. Citation styles can dictate more than just the appearance of the citations themselves, but rather can impact the layout of your paper as a whole, with specific guidelines concerning margin width, title treatment, and even font size and spacing. Knowing how to organize your paper before you start writing will ensure that you do not receive a low grade for something as trivial as forgetting a hanging indent.

Don’t know where to start? Here’s a formatting guide on APA format .

3. Double-check All of Your Outside Sources for Relevance and Trustworthiness First

Collecting outside sources that support your research and specific topic is a critical step in writing an effective paper. But before you run to the library and grab the first 20 books you can lay your hands on, keep in mind that selecting a source to include in your paper should not be taken lightly. Before you proceed with using it to backup your ideas, run a quick Internet search for it and see if other scholars in your field have written about it as well. Check to see if there are book reviews about it or peer accolades. If you spot something that seems off to you, you may want to consider leaving it out of your work. Doing this before your start making citations can save you a ton of time in the long run.

Finished with your paper? It may be time to run it through a grammar and plagiarism checker , like the one offered by EasyBib Plus. If you’re just looking to brush up on the basics, our grammar guides are ready anytime you are.

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Citation Basics

Harvard Referencing

Plagiarism Basics

Plagiarism Checker

Upload a paper to check for plagiarism against billions of sources and get advanced writing suggestions for clarity and style.

Get Started

What is the 'best' children's book? Kids, parents and authors on why some rise to the top

What was your favorite book as a kid?