Slavery in Colonial America

Slavery in Colonial America, defined as white English settlers enslaving Africans, began in 1640 in the Jamestown Colony of Virginia but had already been embraced as policy prior to that date with the enslavement and deportation of Native Americans. Although the first Africans arrived in Virginia in 1619, chattel slavery was not institutionalized at that time.

Colonial reports from Jamestown as early as 1610 note the practice of enslaving Native Americans, and the Pequot Wars of the New England Colonies (1636-1638) ended in colonial victory and the enslavement and deportation of members of the Pequot tribe. Although institutionalized chattel slavery did not become policy in Virginia until the 1660s, therefore, the concept and practice were already well-established, having first been introduced by the Spanish and Portuguese in the Americas before the arrival of the English.

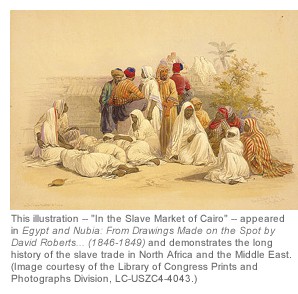

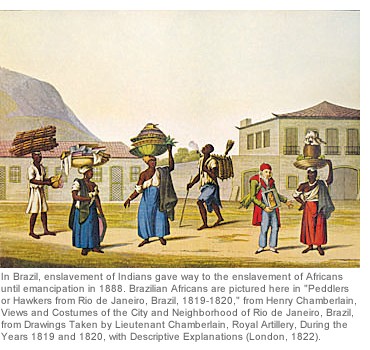

Slavery in the Americas was widely practiced by indigenous tribes who enslaved those captured in raids, wars, or who were traded from one group to another for various reasons but there was no slave trade per se. Institutionalized chattel slavery was only introduced after the arrival of Christopher Columbus (l. 1451-1506) in 1492, was developed by the Spanish and Portuguese by 1500, and was already integral to Spanish and Portuguese colonial economies by 1519.

As the English colonized North America between 1607-1733, slavery became institutionalized and race-based. Native Americans who were taken as slaves were usually sold to plantation owners in the West Indies while African slaves were imported in what became known as the Triangle Trade between Europe , West Africa , and the Americas. Every one of the English colonies held slaves but the lives of the enslaved differed, often significantly, between them.

Although some colonies, such as Pennsylvania, objected to the practice, the citizens still kept slaves. The abolitionist movement gained some momentum leading up to, and away from, the American War of Independence (1775-1783), but it was not until the 19th century that concerted efforts were made to abolish the practice. The first major legislative blow to slavery was the Emancipation Proclamation issued in January of 1863 which freed slaves in the Confederate States, but slavery was not abolished in the United States until the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution in 1865 though the effects of the institution of racial slavery would continue to inform American culture up through the present day.

Columbus & the Slave Trade

Columbus did not so much "discover America" as conceive of the means of fully exploiting the people he found already living in the Caribbean, South, and Central America. On his first voyage in 1492, he kidnapped a number of natives to bring back to his patrons, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain who had hoped he would return with massive quantities of gold . Having found no gold, Columbus offered the royal couple the natives as slaves.

On his second voyage in 1493, he kidnapped more natives, but Ferdinand and Isabella had not given their consent for this as they were uneasy about the morality and legality of enslaving people who had offered them no offense. They ordered Columbus to stop until the matter could be resolved by their theologians and legal counselors, but he ignored them and sent over 500 enslaved natives to Spain from the West Indies in 1495.

Between 1493-1496, he established the encomienda system in the lands he had claimed for Spain in which Spanish settlers were given large tracts of land worked by natives in exchange for food, shelter, and protection from the Spaniards. Ferdinand and Isabella outlawed slavery in Spain and ordered those who had been brought freed but legalized slavery and the encomienda system in their New World colonies. Once slavery was established there, the slave trade – which Columbus had already initiated – developed quickly with Spanish, Dutch, Portuguese, and French ships transporting enslaved natives to various points and Spanish colonists enslaving those who remained.

The enslavement of the indigenous peoples of the West Indies, South, and Central America continued throughout the 16th century while, to the north, the French and Dutch attempted to build alliances with the natives at the same time they profited from the slave trade in the south by shipping slaves between points of trade. The English were the last to introduce slavery to the Americas in the Colony of Virginia, first enslaving Native Americans as early as 1610 and Africans between 1640 and 1660.

Jamestown & Virginia Slave Laws

By the time the English began their colonization efforts in North America in 1585, the slave trade was regarded simply as another import-export business and the early colonists of Jamestown saw the natives of the Powhatan Confederacy as another resource to exploit. Captain John Smith (l. 1580-1631) writes of colonists regularly stealing from the natives and a report from another colonist c. 1610 claims that natives were already being taken as slaves by that time.

In 1619, a Dutch ship carrying 20 or 21 enslaved Africans arrived at Jamestown seeking supplies and provisions. Governor Yeardley (l. 1587-1627) traded these for the Africans, but they seem to have regarded as indentured servants, not slaves. The Dutch ship was not bound for Jamestown with its cargo but was forced to put into port due to shortages aboard. Slavery might have developed in the English colonies anyway, and probably would have, but this event signals the arrival of the first unwilling Africans as servants to English landowners.

The claim that these first Africans were indentured servants, not slaves, is supported by evidence that the English colonists themselves regarded them as such. Although the Africans were purchased from the Dutch ship for the necessary supplies, they were not then enslaved by Yeardley but worked for between 4-7 years and then given their own land to farm in accordance with the policy of indentured servitude. One of these, later known as Anthony Johnson, is listed in the census prior to 1640 as a freeman and had purchased a slave of his own named John Casar.

This policy changed in 1640 when a black indentured servant named John Punch objected to the treatment he received from his master and left service in the company of two white servants. When the three were caught and returned to their master, the two whites had their terms of servitude extended by four years while Punch was condemned to lifelong servitude. Many scholars cite the Punch event as the beginning of institutionalized slavery in the English colonies. Virginia Colony passed laws restricting the rights of Africans after 1640 and, especially, during the 1660s when slavery became fully institutionalized.

New England & Middle Colonies

While Jamestown and the Virginia colonies were developing to the south, the New England Colonies were established. Plymouth Colony was founded in 1620 and Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630 with other New England Colonies then springing up from the latter. The first record of Native American enslavement appears after the Pequot War when many of the defeated natives were sold as slaves to plantations in the West Indies. Massachusetts Bay Colony passed the first laws regarding slavery in 1641, defining justified enslavement as applying to those who were taken captive in war, convicted of a crime and enslaved as punishment, or as foreigners to the community, already enslaved by others, who were sold to colonists in New England.

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

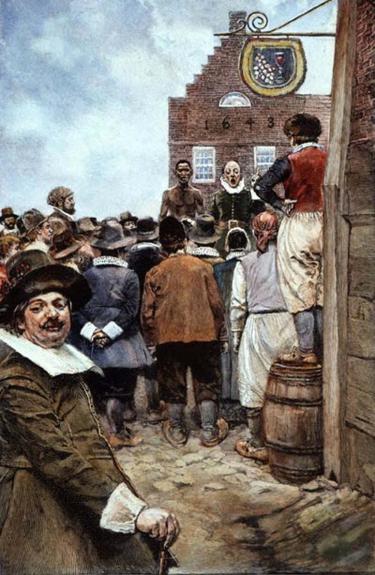

Although the New England Colonies and Middle Colonies are not usually associated with slavery, they all kept slaves to greater or lesser degrees. By 1703, New York City ’s slave population made up 42% of the whole and a slave market operated on the East River on Wall Street. New York also passed one of the first laws setting the death penalty for slaves who rose against or murdered their masters. Pennsylvania, the only English colony to condemn slavery, still practiced it. A petition against slavery, drafted by Quakers in 1688 and submitted to the colonial government, was filed and then forgotten until the mid-19th century.

Massachusetts Bay took the lead in profiting from the slave trade initially by shipping salted fish to plantations in the West Indies to feed their slaves and then by importing Africans as slaves from elsewhere to be sold in New England slave markets. This practice was considered legal as these people had already been enslaved by others and were only being purchased by New Englanders; it ignored, however, the fact that the market the colonies created encouraged those others to enslave and transport more and more Africans via the route known as the Triangle Trade.

The Triangle Trade & Middle Passage

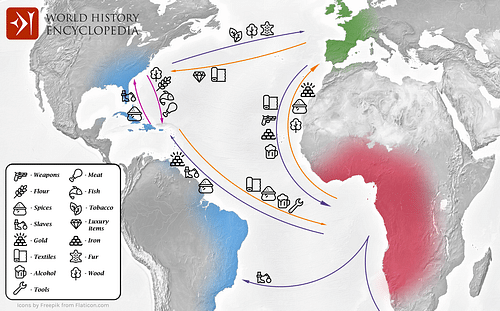

The Triangle Trade was a cyclical exchange of goods and human beings between Europe, West Africa, and the Americas and enabled the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Colonists exported raw goods to Britain where they were processed into finished goods and traded with West Africa, which then sent slaves to the English colonies. Those who were taken as slaves in Africa were forced to endure the Middle Passage – the trip from Africa to North America – loaded below decks as cargo and packed as tightly as possible for maximum profit, especially since over half were expected to die before reaching their destination. Scholar Oscar Reiss elaborates:

If 18 million left Africa during the "trading period" then perhaps 6 million died. Lord Palmerston, who opposed the slave trade, believed that of every three blacks taken from the interior, one reached America. According to the tables kept by the Board of Trade between 1680 and 1688, the Africa Company shipped out 60, 783 "pieces of merchandise" and delivered 46,394 – a loss of 23 percent. In business terms, this was a loss of principal. These slaves were paid for in Africa and failure to deliver them for sale at their destination was a serious loss. (34)

To make up for that loss, the captains packed as many people as possible into the holds of their ships. Reiss continues:

They were forced to lie "spoon fashion" on their sides to conserve space. A fully grown male received eighteen inches’ width by six feet of length; women received five feet ten inches of length by sixteen inches; boys five feet by fourteen inches; and girls four feet, six inches by twelve inches. Lord Palmerston commented that they had less room than a corpse in a coffin. Crowding was so intense that the British Parliament passed a law restricting the numbers of slaves to no more than five slaves per three three-ton capacity in a ship of 200 tons. Like so much unpopular legislation, this was not obeyed by the ships’ captains. (34)

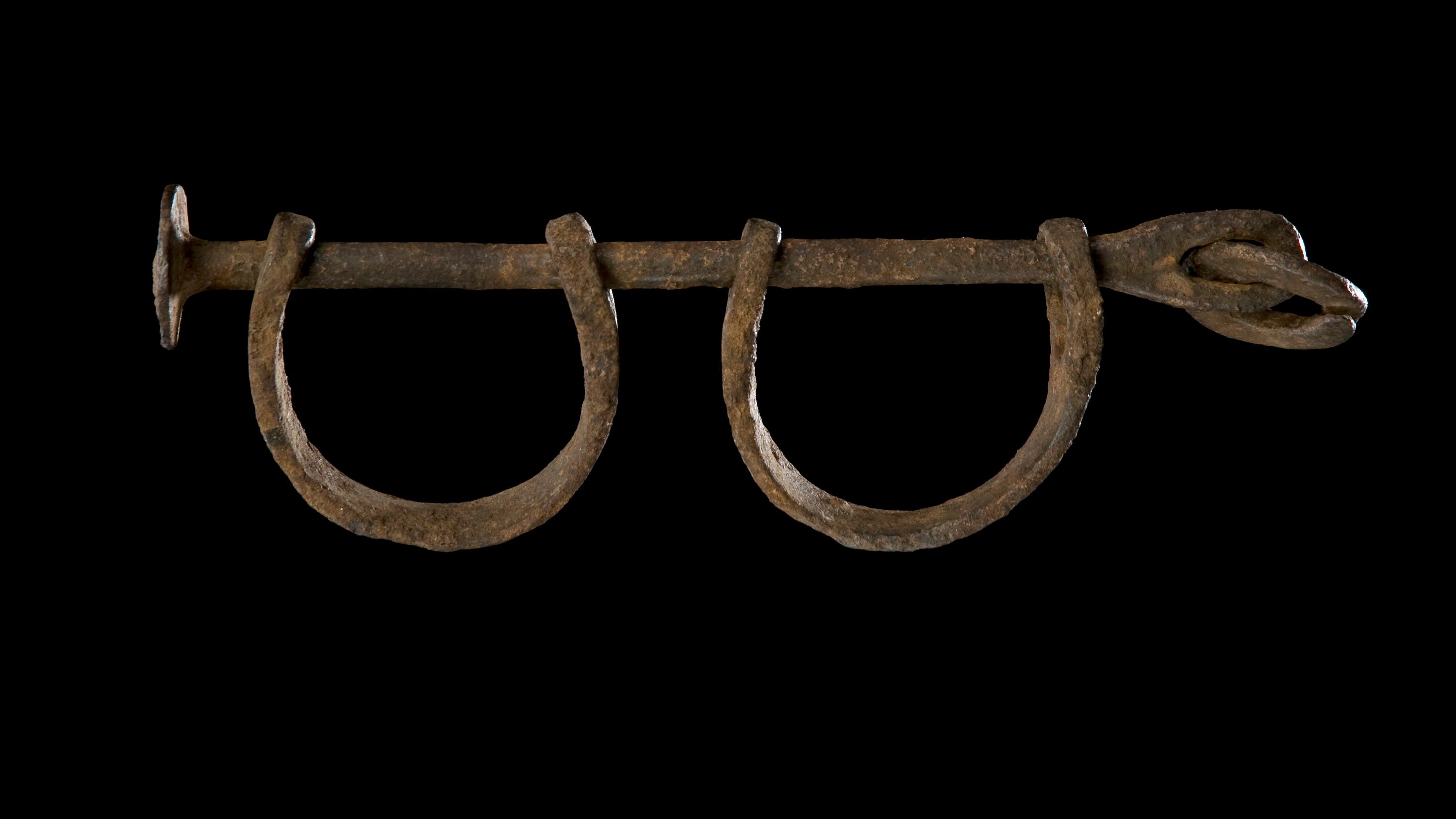

The slaves were all confined below deck in semi- or complete darkness with men, women, and boys separated and only the men manacled. In good weather, the slaves were brought up on deck – chained to prevent anyone throwing themselves overboard – and were left there sometimes all day with little water and, just like in the hold, only small buckets to relieve themselves in, which were too small and too few for the purpose they were supposed to serve.

The Middle Passage was so-called because it was the second (or “middle”) of a three-part trade route that began and ended in Europe. The first passage was from Europe to Africa carrying textiles, metals, alcohol, weaponry, and other valuables which were traded for slaves who then made the middle passage to the Americas where they were traded for other valuables and commodities which were sent on the third passage back to Europe. The Triangle Trade was in full operation between the early 16th through the mid-19th century, and the majority of the slaves brought to North America went to the Southern Colonies .

Southern States Slave Laws

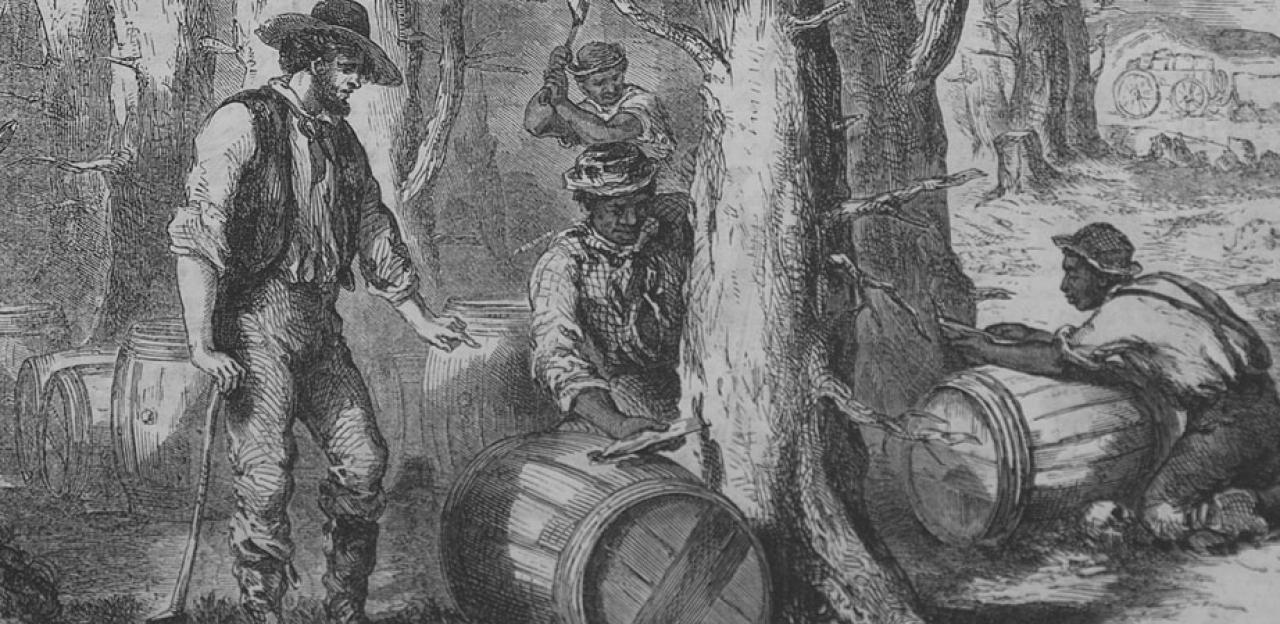

New England Colonies and Middle Colonies held slaves but not as many as the Southern Colonies and the work required of the enslaved was more labor-intensive in the south than in the north. Large southern tobacco, rice, and cotton plantations came to rely heavily on slave labor, while smaller farms in the north, typically worked by a farmer and his family, did not require slave labor, at least not to so great a degree. While slaves in the New England and Middle Colonies primarily worked the ports, loading and unloading ships, those in the south largely worked the fields of the plantations. Slavery in the Southern Colonies followed the model established by the English colony of Barbados. Scholar Alan Taylor notes:

Because English law provided no precedents for managing a system of racial slavery, the Barbadians had to develop their own slave code, which they systematized in 1661. The Barbadian code became the model for those adopted elsewhere in the English colonies, particularly Jamaica (1664) and Carolina (1696), which both originated as offshoots from Barbados. (213)

The code mandated:

- No slave could leave their plantation without written permission by his or her owner.

- Slaves could not play musical instruments, beat drums, sound horns, or make loud noises that could signal rebellion.

- Whites were encouraged to ask any black person for his or her pass on the street and to search them, without cause, for weapons or contraband.

- Blacks were encouraged to inform on fellow blacks, prevent escapes, and turn over fugitives; they were rewarded with new clothes, better treatment, and given "a badge of a red cross on his right arm whereby he may be known and cherished by all good people" (Taylor, 213).

The planters unwittingly paid psychological, social, and demographic costs for adopting the West Indian slave system. And they freely shared those costs with poor whites who owned no slaves…As in the West Indies, the planters suffered from a haunting fear that their African majority would rise up in deadly, burning rebellion. In a desperate search for security, the Carolina planters adopted the West Indian system of strict surveillance and harsh punishment to keep the slaves intimidated and working. The new system criminalized formerly tolerated behavior, revoking the degree of trust and autonomy previously allowed most slaves in the frontier era. (239)

Slaves who were accused of fomenting rebellion were hanged or burned at the stake, often on little to no evidence of their guilt. The fear was fueled not only by the knowledge that the white population had enslaved and dehumanized the black populations of the region but by the memory of two early rebellions by the servant class in Virginia. The Gloucester County Conspiracy of 1663 ended before it began when it was betrayed by another servant but Bacon's Rebellion of 1676 united black and white indentured servants and slaves, resulting in the burning of Jamestown.

In spite of the repressive measures of the Southern Colonies toward the black population, revolts did break out. The Stono Rebellion of 1739 in South Carolina is the largest slave revolt launched in the Thirteen Colonies. Led by a slave named Jemmy, around 20 slaves gathered at the Stono River on Sunday, 9 September 1739, raided a warehouse for weapons, and then marched toward the safety of Spanish St. Augustine , Florida where they would be free. The slaves attacked and killed white masters, and their group swelled to at least 100 before the militia counterattacked. 25 white colonists were killed in the uprising and at least 30 blacks in the week-long battles with the militia; afterwards, more slaves were hanged, and executions went on, with little recourse to any legal proceedings, through the following year.

When the American War of Independence broke out in 1775, many slaves hoped they would be granted freedom since words like 'liberty' and 'justice' and phrases regarding an 'end to oppression' were frequently heard from white masters. Some black slaves served in the Continental Army in place of their masters in return for their freedom but, when the war ended, slavery was still in place in the colonies.

The New England and Middle colonies abolished slavery by 1850, in part due to pressure from the growing abolitionist movement, but also, they could afford to do so because, as noted, the northern economy was not as dependent on slave labor as that of the south and became even less so through industrialization . The Southern Colonies continued the "peculiar institution", as they called it, until forced to abandon it after the American Civil War ended in their defeat in 1865.

The Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery in the United States and freed the slaves but the systemic racism the institution had engendered did not simply vanish away. African Americans in the United States have experienced a very different America than the one lauded in song as the "land of the free and the home of the brave" and continue to do so in the present when the specter of racialized slavery manifests itself in unequal medical care, opportunities, and justice before the law for the descendants of those brought as slaves to the colonies by people claiming to have founded a land based on the concept of freedom for all.

Subscribe to topic Bibliography Related Content Books Cite This Work License

Bibliography

- de Las Casas, B. & Griffin, N. & Pagden, A. A Short Account of the Destruction of the West Indies . Pantianos Classics, 2007.

- Drake, S. G. History of the Early Discovery of America and Landing of the Pilgrims. Nabu Press, 2010.

- Hawke, D. F. Everyday Life in Early America. Harper & Row, 1989.

- Mann, C. C. 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created. Vintage Books, 2012.

- Musselwhite, P., Mancall, P. C. , Horn, J. Virginia 1619: Slavery and Freedom in the Making of America. University of North Carolina Press, 2019.

- Orr, C. History of the Pequot War. Pantianos Classics, 2012.

- Price, D. A. Love and Hate in Jamestown: John Smith, Pocahontas, and the Start of a New Nation. Vintage Books, 2005.

- Reiss, O. Blacks in Colonial America. McFarland, 2006.

- Reséndez, A. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America. Mariner Books, 2017.

- Taylor, A. American Colonies: The Settling of North America. Penguin Books, 2002.

About the Author

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this article into another language!

Related Content

John Hawkins

Jamestown Colony of Virginia

European Colonization of the Americas

Henricus Colony of Virginia

Jamestown Brides

Popham Colony

Free for the world, supported by you.

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

Recommended Books

| , published by McFarland (2006) |

| , published by The University of North Carolina Press (2019) |

| , published by Vintage (2012) |

| , published by Penguin (1970) |

| , published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (2016) |

Cite This Work

Mark, J. J. (2021, April 22). Slavery in Colonial America . World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1739/slavery-in-colonial-america/

Chicago Style

Mark, Joshua J.. " Slavery in Colonial America ." World History Encyclopedia . Last modified April 22, 2021. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1739/slavery-in-colonial-america/.

Mark, Joshua J.. " Slavery in Colonial America ." World History Encyclopedia . World History Encyclopedia, 22 Apr 2021. Web. 24 Jun 2024.

License & Copyright

Submitted by Joshua J. Mark , published on 22 April 2021. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike . This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

Slavery in Colonial America

Many cultures practiced some version of the institution of slavery in the ancient and modern world, most commonly involving enemy captives or prisoners of war. Slavery and forced labor began in colonial America almost as soon as the English arrived and established a permanent settlement at Jamestown in 1607. Colonist George Percy wrote that the English held an “Indian guide” named Kempes in “hande locke” during the First Anglo-Powhatan War in 1610. English colonists exploited Virginia Indians—especially Indian children—for much of the first half of the 17 th century. Some colonists largely ignored Virginia laws prohibiting the enslavement of Indian children, which the Virginia Assembly passed in the 1650s and again in 1670.

While colonists continued to enslave Virginia Indians, the first unfree Africans arrived in Virginia in 1619. In that year, colonist John Rolfe wrote to Sir Edwin Sandys, one of the founders of the Virginia Company and its then-treasurer, of the arrival of the first Africans on Virginia’s shores. According to Rolfe, in late August a 160-ton man-of-war, the White Lion , brought “20 and odd Negroes” to Point Comfort (present-day Hampton, Virginia). Governor George Yeardley and merchant Abraham Piersey purchased them in exchange for victuals and supplies. Days later in September, two or three more Africans disembarked from the ship Treasurer . These Africans were likely from the Angolan kingdom of Ndongo, captured by Angolan warriors allied with the Portuguese.

The 1620 census of Virginia records 32 Africans living in Virginia, 17 women and 15 men, listed as “in service of the English” and “in ye service of several[sic] planters.” This census also lists four Indians laboring in the service of English planters. A 1624 muster of the inhabitants of Virginia lists some of the Africans by name, including a woman named Angelo, listed as having arrived on the Treasurer . The legal status of these first Africans in Virginia is unclear—whether the English settlers in Virginia intended to enslave the Africans for life, or whether they served for a period of years before gaining their freedom (a system of indentured servitude) is unknown, though some of these early Africans did later become free. For example, Anthony Johnson (whom the 1625 census lists as “Antonio the Negro”) gained his freedom and by 1640 lived in a community of other free Africans and African Americans in Northampton County, Virginia. Anthony himself may have even enslaved an African man named John Casar.

As Europeans continued to settle the North American colonies throughout the 17 th century, the legal codification of race-based slavery also continued to grow. Though many historians agree that slavery and indentured servitude coexisted in the early part of the century (with many Europeans arriving in the colonies under indentures), especially throughout the 1640s-1660s colonies increasingly established laws limiting the rights of Africans and African-Americans and solidifying the institution of slavery upon the basis of race and heredity. In Virginia in 1641, officials sentenced “a negro named John Punch” to serve his master “for the time of his natural life,” after Punch attempted to run away with two European indentured servants. Officials sentenced the two Europeans with four-year extensions on their servitude, while Punch’s punishment was life-long servitude. Many historians look to the case of John Punch as the first instance of legally codified, life-long, and race-based slavery. In New England, colonists continued the practice of enslaving indigenous Indians, particularly those captured during warfare, while also legally justifying the enslavement of African and African Americans. Massachusetts is widely regarded as passing the first law to legalize slavery in 1641, sanctioning slavery for “captives taken in just warres…and strangers as willingly selle[sic] themselves or are sold to us.”

The “ triangle trade ” largely defines the economics of slavery in the colonial era. In this cyclical system, slave traders imported enslaved Africans to North American colonies. Colonists in turn exported raw goods like lumber, tobacco, and sugar to Great Britain, where those materials were transformed into the finished, luxury goods like rum and textiles that merchants sold or traded along the African coast for enslaved Africans to be sent to North American colonies. Slave traders violently captured Africans and loaded them onto slave ships, where for months these individuals endured the “Middle Passage”—the crossing of the Atlantic from Africa to the North American colonies or West Indies. Many Africans did not survive the journey.

The 1660s was a watershed decade for slavery in colonial America. It is important to remember that during the colonial period, each colony enacted and enforced laws regarding slavery individually. Virginia’s 1662 law establishing that children born to an enslaved mother would also be enslaved further codified race-based and hereditary enslavement in that colony. Maryland legalized slavery in 1663; New York and New Jersey followed in 1664. In addition, that year Maryland, New York, New Jersey, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia passed laws legalizing life-long servitude. Colonies also adopted laws prohibiting non-whites from owning firearms, and established laws that negated a person’s conversion to Christianity from affecting their status as a slave.

It is in this context of the evolution of slavery in colonial America that in 1688 Quakers in Germantown, Pennsylvania presented the first petition against the institution of slavery. The petition argued that slavery violated basic human rights-based upon the Biblical Golden Rule, “do unto others as you would have done unto you.” The petition was neither adopted nor rejected, and largely forgotten until the 19 th century.

Many factors contributed to the growth of slavery and the slave trade from the end of the 17 th -century through the 18 th century. The history and growth of slavery in colonial America was tied to the rise of land cultivation, and particularly the boom in the production of tobacco (in Virginia and Maryland) and rice (in the Carolinas). The Royal African Company’s expansion in 1672 resulted in a growing surge of the transport of Africans to the colonies. When the RAC lost its monopoly in 1696, trade in captive Africans and their transport to the colonies increased further. As the numbers of enslaved Africans rose in the colonies, the practice of enslaving indigenous Indians decreased, and colonial officials further restricted the rights and movements of enslaved Africans and African Americans, including making it harder—even illegal—for slaves to be emancipated. In the first decades of the 18 th century, some colonies began prohibiting the importation of enslaved Africans, though the internal slave trade—the buying and selling of enslaved people already in the colonies—increased.

Enslaved people were regarded and treated as property with little to no rights. In many colonies, enslaved people could not testify in a court of law, own guns, gather in large groups, or go out at night. Especially on southern farms, enslaved people were expected to work from sun up to sundown, though they may have been given Sundays off to tend to their own small gardens, repair allotted clothing, or tend to other needs that might supplement their meager allotments of clothing and food. As property, slaves were frequently bought and sold, and sometimes family groups were divided across plantations or even colonies, though some slave owners sought to keep families together as a safeguard against slaves running away. Slaves of small households often lived in the kitchen or a small outbuilding, while slaves on larger plantations often lived together in a quarter or a group of quarters with an overseer. Religion, storytelling, music, and dancing were important parts of an enslaved person’s life, and could help share and preserve African cultural traditions across generations. Increasingly in the 18 th century, slaves responded to the Great Awakening and began converting to Christianity, worshiping both alone and together with whites in Baptist and Methodist congregations.

An enslaved person’s experience of slavery was as unique as the individual themselves. Slavery differed greatly from the 17 th to 18 th centuries, in part because of the various slave laws enacted by colonial authorities as time progressed. Further, the geographic location could help to define an enslaved person’s experience of slavery. In the south, many enslaved individuals found themselves working primarily in agricultural labor, such as in tobacco fields, while others (including women and children) worked as grooms, maids, cooks, or other domestic servants to wealthy plantation owners. In the north, as well as in urban city centers in the south, enslaved individuals may have been skilled tradesmen, worked on the eastern seaboard’s many wharves and ports, or worked on the smaller farms of middling landowners.

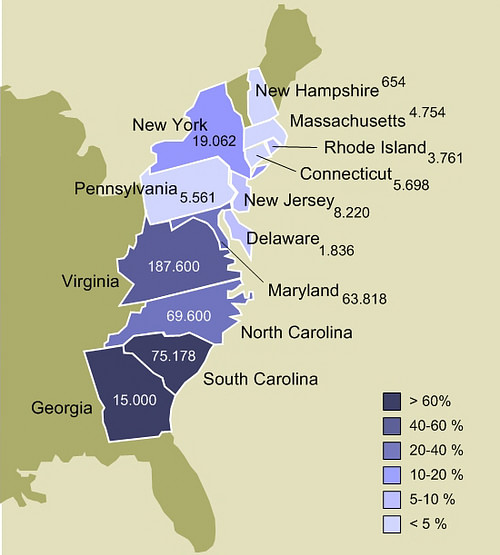

In the northern colonies, slave-owning households may have only owned two or three slaves, while the enslaved population accounted for less than 5% of the total population of New England (though in larger cities like Newport, Rhode Island, slaves accounted for closer to 20% of the population of the city). In the mid-Atlantic colonies like Virginia, enslaved people made up closer to 50% of the population by the mid-18 th century. This number increased to roughly 60% in colonies like South Carolina, where much of the enslaved population lived and worked on vast plantations together with 50, 100, or more slaves.

As slavery expanded and the numbers of enslaved men, women, and children increased in the colonies, so too did anxieties about possible slave rebellions, uprisings, and insurrections. On September 9, 1739, a group of 20 enslaved men led by an enslaved African named Jemmy marched to a warehouse on the Stono River in South Carolina, where they stole arms and ammunition and killed the men they found there. The party grew in number, and with drums beating, the party continued south towards Florida, where they hoped to find their freedom there under Spanish rule. The party killed more than 20 white men, women, and children along their march before the militia intervened. Some of the slaves were killed during the fight while others were hanged or sold to slave markets in the West Indies (a routine yet harsh punishment for enslaved men, women, and children in the colonies). In New York in 1741, a series of suspicious fires fanned the flames of unrest between the colony’s white, Black, free, and unfree populations. Anxious whites concluded, with little evidence, that enslaved men acted in concert to set fires in the city in a conspiratorial act of rebellion. Thirty enslaved men were executed, while 70 more were sent out of New York.

Even without large-scale rebellion, some enslaved men, women, and children found ways to passively resist in their daily lives by breaking tools or pretending to be sick so that they could not work. Others stole food, goods, or clothing from their owners. Some attempted to run away. Eighteenth-century newspapers often include owners’ runaway advertisements, spreading the news of runaway slaves and sharing their physical descriptions along with a reward for whomever captured and returned the slave to the owner. A slave returning from a runaway attempt was met with harsh punishment.

By 1775, enslaved people accounted for 20% of the population of the colonies, with over half living in the south. On the eve of the Revolution, aided by the patriot rhetoric of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, enslaved and free African Americans worked to further the growing abolition movement and petitioned governments for gradual manumission and cessation of slavery. Further, enticed by promises of freedom in exchange for their service, enslaved African Americans took advantage of opportunities to serve the British army. Thousands of formerly enslaved men, women, and children left the new United States with the British in 1783, looking towards new lives of freedom in Nova Scotia and other British colonies. Enslaved men also served in patriot forces, sometimes by choice, but sometimes as substitutes for their owners who preferred not to fight. Some received payments and freedom for their service, while others did not.

The American Revolution offered many enslaved African Americans opportunities to pursue freedom that did not exist previously. The Revolution also influenced public opinion of slavery—in 1780 Pennsylvania became the first major slave-holding state to begin the process of ending slavery. Though some other new states followed suit, the Revolution failed to end the institution of slavery in America. Instead, the economy’s reliance on slavery proved to be a defining element in the creation of the new United States government.

Further Reading:

- Indian Slavery in Colonial America By: Alan Gallay

- Black Americans in the Revolutionary Ear: A Brief History with Documents By: Woody Holton

- American Slavery, American Freedom By: Edmund S. Morgan

- New England Bound: Slavery and Colonization in Early America By: Wendy Warren

Culpeper in the Crosshairs

Fire with Fire: The Battle of Cedar Mountain

Brandy Station Transformation

You may also like.

Worlds of Change

- Portals to the Past: Widener Exhibit

Slavery in Colonial North America

Essay by 2016 arcadia fellow teresa mcculla.

Slavery is central to the history of colonial North America. For more than two centuries, European Americans treated enslaved men, women, and children as objects that could be bought and sold .[i] Harvard’s digitized collections can help scholars understand how the institution of slavery suffused every aspect of the colonial world.

The crude logic of enslaving human beings cast people as tools who required input (food and clothing) in order to produce the output of their labor. In the calculations of colonial-era businessmen, all of these components, including the body of the enslaved person, could be given a monetary value. For example, in February 1724, Harvard tutor Henry Flynt speculated as to the financial feasibility of operating a ferry with the assistance of a slave. “ [I]f a man…buys a negro at 60 pounds who lives 20 year[s] his Labour is but 3 pounds a year ,” he reasoned, “and his Victuals 26 pounds per annum makes 29 pounds which with 6 pounds wear and tare and 50 pounds rent makes 85 pounds.”[ii] The man Flynt imagined was an aggregate of calculations: a business investment to manage. Flynt applied such arithmetic to personal matters as well. When Flynt’s elderly mother passed away in the 1730s, he quibbled with his brother-in-law over Toney, the enslaved man who had worked for her. The men cared less for Toney’s fate, though, than the cash he represented. Toney became an element of Flynt’s mother’s estate to settle, alongside “all the household stuff” that Flynt could tally, which included “ Brass Silver Iron bedding Linnen .”[iii] Flynt sold Toney to another enslaver and balanced the price of the man’s sale against the money he paid for his mother’s final expenses: “ the Grave and bel ringing and pall etc .”[iv] Treated as an investment, Toney disappeared from Flynt’s diary after his sale. Most researchers consult the diary of Henry Flynt, an enormous tome, to understand the workings of Harvard College life and colonial accounting practices. However, the experiences of historical figures like Toney count as an equally important, if subtle, presence in this and similar records.

Enslaved people are particularly prominent in archived manuscripts related to trade and agriculture in the colonial Caribbean. For example, in 1763, Britain legislated the regulation of auctions in Barbados , events which included the sale of enslaved people.[v] In 1777, a Barbados official wrote to members of the British Council for Plantation Affairs to ask for more “ India and Guinea Corn for the Negroes ,” who toiled in sugarcane plantations there.[vi] Naval captains throughout the Caribbean also hired local people of color as temporary laborers to assist in the work of getting their ships in and out of ports, as they transported coffee, sugar, rum, and slaves among European colonies.[vii]

Legal manuscripts count as another important genre in the documented history of colonial slavery.[viii] Occasionally, enslaved people used the American court system to sue for their own freedom , but more often they stood at the center of trials, treated as disputed property or accused of crimes.[ix] One Delaware court case at the close of the colonial period demonstrated the multiple implications of interpreting a person as an owned object. In less than fifteen minutes, a jury convicted George, an enslaved man accused of raping a white woman, and sentenced him to death. The court treated George as a human in convicting him of a violent crime and executing him. But George’s execution also represented the destruction of property from the perspective of George’s enslaver. Thus, the judge ordered the jury to not only determine George’s guilt or innocence but also to “ assess the value of the Negro, two thirds of which by law is to be paid by the County to the owner .”[x] Because the state had carried out George’s execution, it owed a debt to George’s owner.

The humanity of enslaved men, women, and children emerges in many other archival sources. For example, under the heading “ January 8th A.M. Family Weighed 1747/8 ,” a teenage John Holyoke recorded in his diary the weights of all members of his household.[xi] Alongside his mother and siblings, Holyoke weighed his father, then president of Harvard College, and Juba, a slave. As this episode demonstrated, even as part of a child’s game, enslaved and free men could be assessed in the same units of measure despite the vast differences in their social situations. A generation later, a man enslaved to Cambridge widow Sarah Bordman left his own mark in an ephemeral document without writing a word. Shoemaker William Manning issued a bill to Bordman listing the costs associated with mending the shoes of “ her negro Cato ” between May 9, 1770 and July 4, 1771.[xii] Every two months, if not more often, Manning mended Cato’s shoes. During this time frame, he also provided four new pairs of shoes. Cato’s rapidly worn shoes recorded his labor for Bordman. Soles that required constant repair testified to the miles walked and work done by an enslaved man in colonial Massachusetts, even if Cato left no written memoir of his own.

In these ways, archival records that track the history of slavery add deep moral complexity to political, economic, and social developments, as well as daily life, in colonial North America and the new United States.

[i] Bordman family. Papers of the Bordman family, 1686-1837. Deed of sale, 1716/7 January 1. HUG 1228 Box 2, Folder 3, Harvard University Archives.

[ii] February 8, 1724. Diary of Henry Flynt, 1723-1747.

[iii] January 22, 1735/6. Diary of Henry Flynt, 1723-1747.

[iv] November 24, 1737. Diary of Henry Flynt, 1723-1747.

[v] Barbados. Laws, etc. An Act of Assembly of Barbadoes to regulate sales at outcry and the proceedings of persons executing the office of Provost Marshall General of the said island and their under officers, 1763. HLS MS 1046, Harvard Law School Library.

[vi] Barbados. A collection of autograph letters and original documents relating to the Island of Barbados in the 18th century, ca. 1730-1778. HLS MS 1047, Harvard Law School Library.

[vii] Bills of lading for the ship Lydia, 1766. Small Manuscript Collection, Harvard Law School Library; Holman, Gabriel. Bill of disbursments [for the] sch[oone]r Lydia: manuscript, 1790. MS Eng 659. Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

[viii] Mexican Legal Documents, 1577-1805. " Denunció " of a black slave named Ana or Mariana of the city of Guastepeque, 20 December 1658. 1-8, Harvard Law School Library.

[ix] Saml. Agg. – Negro / John Forbes, Petition for freedom. Delaware. Court of Common Pleas. Records, 1790-1805. Small Manuscript Collection, Volume 3, Harvard Law School Library; Indict _ Felony in Stealing a Negro Woman called Hannah price $200 property of ___ Porter and for aiding Negro David, his slave and her husband, in Stealing said Hannah Plea Not Guilty. Delaware. Court of Common Pleas. Records, 1790-1805. Small Manuscript Collection, Volume 3, Harvard Law School Library.

[x] State / A Negro George the Slave of Susan H__. Delaware. Court of Common Pleas. Records, 1790-1805. Small Manuscript Collection, Volume 3, Harvard Law School Library.

[xi] Holyoke family. Holyoke family diaries, 1742-1748. Diary of John Holyoke, 1748. Interleaved almanac, 1748. HUM 46 Volume 6, Harvard University Archives.

[xii] Bordman family. Papers of the Bordman family, 1686-1837. Bill, 1771 August 23. HUG 1228 Box 2, Folder 39, Harvard University Archives.

Background Essay: The Origins of American Slavery

How did enslaved and free blacks resist the injustice of slavery during the colonial era.

- I can articulate how slavery was at odds with the principle of justice.

- I can explain how enslaved men and women resisted the institution of slavery.

- I can create an argument supported by evidence from primary sources.

- I can succinctly summarize the main ideas of historic texts.

Essential Vocabulary

| Forced | |

| System of trade during the 18th and 19th centuries that involved Western Europe, West Africa and Central Africa, and North and South America. Major goods that were traded involved manufactured goods such as firearms and alcohol, slaves, and commodities such as sugar, molasses, tobacco, and cotton. | |

| Horrific | |

| The part of the Atlantic slave trade where Africans were densely packed onto ships and transported across the Atlantic Ocean to the New World. | |

| Rights which belong to humans by nature and can only be justly abridged through due process. Examples are life, liberty, and property. | |

| A way of managing enslaved work on plantations in which planters or their overseers drove groups of enslaved persons, closely watched their work, and applied physical coercion to compel them to work faster. | |

| A way of managing enslaved work on plantations where enslaved persons were often assigned specific tasks and allowed to stop working when they reached their goals. | |

| Making decisions for another person as if a parent, rather than allowing that person the freedom to make their own decisions and choices. |

Written by: The Bill of Rights Institute

American Slavery in the Colonies

Throughout the colonial era, many white colonists in British North America gradually imposed a system of unfree and coerced labor upon Africans in all the colonies. Throughout the colonies, enslavement of Africans became a racial, lifelong, and hereditary condition. The institution was bound up with the larger Atlantic System of trade and slavery yet developed a unique and diverse character in British North America.

Europeans forcibly brought Africans to the New World in the international slave trade. From the fifteenth to the nineteenth century, European slave ships carried 12.5 million Africans, mostly to the New World. Because of the crowded ships, diseases, and mistreatment, only 10.7 million enslaved Africans landed at their destinations. Almost 2 million souls perished in what a draft of the Declaration of Independence later called an “ execrable commerce.”

Europeans primarily acquired the enslaved Africans from African slave traders along the western coast of the continent by exchanging guns, alcohol, textiles, and a broad range of goods demanded by the African traders. The enslaved were alone, having been separated from their families and embarked on the harrowing journey called the “ Middle Passage ” in chains. They were frightened and confused by their tragic predicament. Some refused to eat or jumped overboard to commit suicide rather than await their fate.

This diagram depicts the layout of a slave ship. (Unknown author – an Abstract of Evidence delivered before a select committee of the House of Commons in 1790 and 1791, reprinted in Phyllis M. Martin and Patrick O’Meara (eds.) (1995). Africa third edition. Indiana University Press and James Currey.) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Middle_Passage#/media/File:Slave_ship_diagram.png

Most Africans in the international trade were bound for the European colonial possessions in the Caribbean and South America. The sugar plantations there were places where disease, climate, and work conditions produced a horrifying death rate for enslaved Africans. The sugar crop was so valuable that it was cheaper to work slaves to death and import replacements. About 5 percent of the human cargo in the slave trade landed in British North America.

The African-American experience in the 13 colonies varied widely and is characterized by great complexity. The climate, geography, agriculture, laws, and culture shaped the diverse nature of enslavement.

Enslaved Africans in the British North American colonies did share many things in common, however. Slavery was a racial, lifetime and hereditary condition. White supremacy was rooted in slavery as its victims were almost exclusively Africans. It was a system of unfree and coerced labor that violated the enslaved person’s natural rights of liberty and consent. While the treatment of slaves might vary depending on region or the disposition of the slaveholder, slavery was at its core a violent and brutal system that stripped away human dignity from the enslaved. In all the colonies, slaves were considered legal property. In other words, slavery was a great injustice.

Differing climates and economies led to very different agricultural systems and patterns of enslavement across the colonies. The North had mostly self-sufficient farms. Few had slaves, and those that did, had one or two enslaved persons. While the North had some important pockets of large landowners who held larger numbers of slaves such as the Hudson Valley, its farms were generally incompatible with large slaveholding. Moreover, the nature of wheat and corn crops generally did not support slaveholding the same way that labor-intensive tobacco and rice did. Cities such as New York and Philadelphia also had the largest Black populations.

On the other hand, the Chesapeake (Maryland and Virginia) and low country of the Carolinas had planters and farmers who raised tobacco, rice, and indigo. Small farms only had one or two slaves (and often none), but the majority of the southern enslaved population lived on plantations. Large plantations frequently held more than 20 enslaved people, and some had hundreds. Virginian Robert “King” Carter held more than 1,000 people in bondage. As a result, in the areas where plantations predominated areas of the South (especially South Carolina), enslaved people outnumbered white colonists and sometimes by large percentages. This led to great fear of slave rebellions and measures by whites, including slave patrols and travel restrictions, to prevent them.

Robert “King” Carter was one of the richest men in all of the American colonies. He owned more than 1,000 slaves on his Virginia plantation. Anonymous. Portrait of Robert “King” Carter. Circa 1720. Painting. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Carter_I#/media/File:Robert_Carter_I.JPG

The regional differences of slavery led to variations in work patterns for enslaved people. A few Northern enslaved people worked and lived on farms alongside slaveholders and their families. Many worked in urban areas as workers, domestic servants, and sailors and generally had more freedom of movement than on southern plantations.

Blacks developed their own cultures in North and South. Despite different cultures and languages brought from Africa and regional differences within the colonies, a strong sense of community developed especially in areas where they had greater autonomy. Slave quarters on large plantations and urban communities of free blacks were notable for the development of Black culture through resistance, preservation of traditions, and expression. The free and enslaved Black communities kept in conversation with each other to transmit news and to hide runaways.

Different systems of work developed on Southern plantations. One was a “gang system ” of labor in which planters or their overseers drove groups of enslaved people, closely watched their work, and applied physical coercion to compel them to work faster. They also worked in the homes, laundries, kitchens, and stables on larger plantations.

On the massive rice plantations of the Carolinas, enslaved people were often assigned tasks and allowed to stop working when they reached their goals. The “ task system ” could foster cooperation and provide incentives to complete their work quicker. Plantation slaves completed other tasks including cooking, cleaning, laundry, childcare, and worked as skilled artisans.

The treatment and experience of enslaved people was rooted in a brutal system but could vary widely. Many slaveholders were violent and cruel, liberally applying severe beatings that were at times limited by law or shunned by society. Others were guided by their Christian beliefs or humanitarian impulses and treated their slaves more paternalistically . Domestic work was often easier but under much closer scrutiny than fieldhands who at times enjoyed more autonomy and community with other enslaved people. Slaveholders in New England were more likely to teach slaves to read or encourage religious worship, but enslaved people were commonly restricted from learning to read, especially in the South.

Enslaved people did not passively accept their condition. They found a variety of ways to resist in order to preserve their humanity and autonomy. Some of the common daily forms of resistance included slowing down their pace of work, breaking a tool, or pretending to be sick. Some stole food and drink to supplement their inadequate diets or simply to enjoy it as an act of rebellion. Young male slaves were especially likely to run away for a few days and hide out locally to protest work or mistreatment. Enslaved people secretly learned to read and that allowed them to forge passes to escape to freedom. They sang spirituals out of religious conviction, but also in part to express their hatred of the system and their hope for freedom.

Slaves developed their own culture as a way to bond together in their hardships and show defiance to their owners. This image depicts slaves on a plantation dancing and playing music. Anonymous. The Old Plantation. Circa. 1790. Painting. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slavery_in_the_United_States#/media/File:Slave_dance_to_banjo,_1780s.jpg

The enslavement of Africans in British colonies in North America developed differently in individual colonies and among regions. But, the common thread running throughout the experience of slavery was injustice. Blacks were denied their humanity and natural rights as they could not keep the fruits of their labor, lived under a brutal system of coercion, and could not live their lives freely. However, a few white colonists questioned the institution before the Revolutionary War.

Comprehension and Analysis Questions

- How did slavery violate an enslaved person’s natural rights?

- How did slavery vary across the 13 British colonies in North America?

- How did Blacks resist their enslavement?

Related Content

Introductory Essay: The Declaration of Independence and the Promise of Liberty and Equality for All: Founding Principles and the Problem of Slavery

The Columbian Exchange | BRI’s Homework Help Series

Have you ever looked at your teacher with a puzzled face when they explain history? I know we have. In our new Homework Help Series we break down history into easy to understand 5 minute videos to support a better understanding of American History. In our first episode, we tackle the Columbian Exchange and early contact between Europeans, Natives and Africans.

Origins of the Slave Trade

Why did Africa and Europe engage in the slave trade?

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Slavery in America

By: History.com Editors

Published: April 25, 2024

Millions of enslaved Africans contributed to the establishment of colonies in the Americas and continued laboring in various regions of the Americas after their independence, including the United States. Many consider a significant starting point to slavery in America to be 1619 , when the privateer The White Lion brought 20 enslaved Africans ashore in the British colony of Jamestown , Virginia . The crew had seized the Africans from the Portuguese slave ship São João Bautista. Yet, enslaved Africans had been present in regions such as Florida, that are part of present-day United States nearly one century before.

Throughout the 17th century, European settlers in North America turned to enslaved Africans as a cheaper, more plentiful labor source than Indigenous populations and indentured servants, who were mostly poor Europeans.

Existing estimates establish that Europeans and American slave traders transported nearly 12.5 million enslaved Africans to the Americas. Of this number approximately 10.7 million disembarked alive in the Americas. During the 18th century alone, approximately 6.5 million enslaved persons were transported to the Americas. This forced migration deprived the African continent of some of its healthiest and ablest men and women.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, enslaved Africans worked mainly on the tobacco, rice and indigo plantations of the southern Atlantic coast, from the Chesapeake Bay colonies of Maryland and Virginia south to Georgia.

Slavery in Plantations and Cities

In the 17th and 18th centuries, enslaved Africans worked mainly on the tobacco, rice and indigo plantations of the southern coast, from the Chesapeake Bay colonies of Maryland and Virginia south to Georgia. Starting 1662, the colony of Virginia and then other English colonies established that the legal status of a slave was inherited through the mother. As a result, the children of enslaved women legally became slaves.

Before the rise of the American Revolution , the first debates to abolish slavery emerged. Black and white abolitionists contributed to the enactment of new legislation gradually abolishing slavery in some northern states such as Vermont and Pennsylvania. However, these laws emancipated only the newly born children of enslaved women.

Did you know? One of the first martyrs to the cause of American patriotism was Crispus Attucks, a former enslaved man who was killed by British soldiers during the Boston Massacre of 1770. Some 5,000 Black soldiers and sailors fought on the American side during the Revolutionary War.

But after the end of the American Revolutionary War , slavery was maintained in the new states. The new U.S. Constitution tacitly acknowledged the institution of slavery, when it determined that three out of every five enslaved people were counted when determining a state's total population for the purposes of taxation and representation in Congress.

Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, European and American slave merchants purchased enslaved Africans who were transported to the Americas and forced into slavery in the American colonies and exploited to work in the production of crops such as tobacco, wheat, indigo, rice, sugar, and cotton. Enslaved men and women also performed work in northern cities such as Boston and New York, and in southern cities such as Charleston, Richmond, and Baltimore.

By the mid-19th century, America’s westward expansion and the abolition movement provoked a great debate over slavery that would tear the nation apart in the bloody Civil War . Though the Union victory freed the nation’s four million enslaved people, the legacy of slavery continued to influence American history, from the Reconstruction to the civil rights movement that emerged a century after emancipation and beyond.

In the late 18th century, the mechanization of the textile industry in England led to a huge demand for American cotton, a southern crop planted and harvested by enslaved people, but whose production was limited by the difficulty of removing the seeds from raw cotton fibers by hand.

But in 1793, a U.S.-born schoolteacher named Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin , a simple mechanized device that efficiently removed the seeds. His device was widely copied, and within a few years, the South transitioned from the large-scale production of tobacco to that of cotton, a switch that reinforced the region’s dependence on enslaved labor.

Slavery was never widespread in the North as it was in the South, but many northern businessmen grew rich on the slave trade and investments in southern plantations. Although gradual abolition emancipated newborns since the late 18th century, slavery was only abolished in New York in 1827, and in Connecticut in 1848.

Though the U.S. Congress outlawed the African slave trade in 1808, the domestic trade flourished, and the enslaved population in the United States nearly tripled over the next 50 years. By 1860 it had reached nearly 4 million, with more than half living in the cotton-producing states of the South.

Living Conditions of Enslaved People

Enslaved people in the antebellum South constituted about one-third of the southern population. Most lived on large plantations or small farms; many enslavers owned fewer than 50 enslaved people.

Landowners sought to make their enslaved completely dependent on them through a system of restrictive codes. They were usually prohibited from learning to read and write, and their behavior and movement were restricted.

Many enslavers raped women they held in slavery, and rewarded obedient behavior with favors, while rebellious enslaved people were brutally punished. A strict hierarchy among the enslaved (from privileged house workers and skilled artisans down to lowly field hands) helped keep them divided and less likely to organize against their enslavers.

Marriages between enslaved men and women had no legal basis, but many did marry and raise large families. Most owners of enslaved workers encouraged this practice, but nonetheless did not usually hesitate to divide families by sale or removal.

Slave Rebellions

Enslaved people organized r ebellions as early as the 18th century. In 1739, enslaved people led the Stono Rebellion in South Carolina, the largest slave rebellion during the colonial era in North America. Other rebellions followed, including the one led by Gabriel Prosser in Richmond in 1800 and by Denmark Vesey in Charleston in 1822. These uprisings were brutally repressed.

The revolt that most terrified enslavers was that led by Nat Turner in Southampton County, Virginia, in August 1831. Turner’s group, which eventually numbered as many 50 Black men, murdered some 55 white people in two days before armed resistance from local white people and the arrival of state militia forces overwhelmed them.

Like with previous rebellions, in the aftermath of the Nat Turner’s Rebellion, slave owners feared similar insurrections and southern states further passed legislation prohibiting the movement and assembly of enslaved people.

Abolitionist Movement

As slavery expanded during the second half of the 18th century, a growing abolitionist movement emerged in the North.

From the 1830s to the 1860s, the movement to abolish slavery in America gained strength, led by formerly enslaved people such as Frederick Douglass and white supporters such as William Lloyd Garrison , founder of the radical newspaper The Liberator .

While many abolitionists based their activism on the belief that slaveholding was a sin, others were more inclined to the non-religious “free-labor” argument, which held that slaveholding was regressive, inefficient and made little economic sense.

Black abolitionists and antislavery northerners led meetings and created newspapers. They also had begun helping enslaved people escape from southern plantations to the North via a loose network of safe houses as early as the 1780s. This practice, known as the Underground Railroad , gained real momentum in the 1830s.

Conductors like Harriet Tubman guided escapees on their journey North, and “ stationmasters ” included such prominent figures as Frederick Douglass, Secretary of State William H. Seward and Pennsylvania congressman Thaddeus Stevens. Although no one knows for sure how many men, women, and children escaped slavery through the Underground Railroad, it was in the thousands ( estimates range from 25,000 to 100,000).

The success of the Underground Railroad helped spread abolitionist feelings in the North. It also undoubtedly increased sectional tensions, convincing pro-slavery southerners of their northern countrymen’s determination to defeat the institution that sustained them.

Missouri Compromise

America’s explosive growth—and its expansion westward in the first half of the 19th century—would provide a larger stage for the growing conflict over slavery in America and its future limitation or expansion.

In 1820, a bitter debate over the federal government’s right to restrict slavery over Missouri’s application for statehood ended in a compromise: Missouri was admitted to the Union as a slave state, Maine as a free state and all western territories north of Missouri’s southern border were to be free soil.

Although the Missouri Compromise was designed to maintain an even balance between slave and free states, it was only temporarily able to help quell the forces of sectionalism.

Kansas-Nebraska Act

In 1850, another tenuous compromise was negotiated to resolve the question of slavery in territories won during the Mexican-American War .

Four years later, however, the Kansas-Nebraska Act opened all new territories to slavery by asserting the rule of popular sovereignty over congressional edict, leading pro- and anti-slavery forces to battle it out—with considerable bloodshed —in the new state of Kansas.

Outrage in the North over the Kansas-Nebraska Act spelled the downfall of the old Whig Party and the birth of a new, all-northern Republican Party . In 1857, the Dred Scott decision by the Supreme Court (involving an enslaved man who sued for his freedom on the grounds that his enslaver had taken him into free territory) effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise by ruling that all territories were open to slavery.

John Brown’s Raid on Harper’s Ferry

In 1859, two years after the Dred Scott decision, an event occurred that would ignite passions nationwide over the issue of slavery.

John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry , Virginia—in which the abolitionist and 22 men, including five Black men and three of Brown’s sons raided and occupied a federal arsenal—resulted in the deaths of 10 people and Brown’s hanging.

The insurrection exposed the growing national rift over slavery: Brown was hailed as a martyred hero by northern abolitionists but was vilified as a mass murderer in the South.

The South would reach the breaking point the following year, when Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln was elected as president. Within three months, seven southern states had seceded to form the Confederate States of America ; four more would follow after the Civil War began.

Though Lincoln’s anti-slavery views were well established, the central Union war aim at first was not to abolish slavery, but to preserve the United States as a nation.

Abolition became a goal only later, due to military necessity, growing anti-slavery sentiment in the North and the self-emancipation of many people who fled enslavement as Union troops swept through the South.

When Did Slavery End?

On September 22, 1862, Lincoln issued a preliminary emancipation proclamation, and on January 1, 1863, he made it official that “slaves within any State, or designated part of a State…in rebellion,…shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

By freeing some 3 million enslaved people in the rebel states, the Emancipation Proclamation deprived the Confederacy of the bulk of its labor forces and put international public opinion strongly on the Union side.

Though the Emancipation Proclamation didn’t officially end all slavery in America—that would happen with the passage of the 13th Amendment after the Civil War’s end in 1865—some 186,000 Black soldiers would join the Union Army, and about 38,000 lost their lives.

The Legacy of Slavery

The 13th Amendment, adopted on December 18, 1865, officially abolished slavery, but freed Black peoples’ status in the post-war South remained precarious, and significant challenges awaited during the Reconstruction period.

Previously enslaved men and women received the rights of citizenship and the “equal protection” of the Constitution in the 14th Amendment and the right to vote in the 15th Amendment , but these provisions of the Constitution were often ignored or violated, and it was difficult for Black citizens to gain a foothold in the post-war economy thanks to restrictive Black codes and regressive contractual arrangements such as sharecropping .

Despite seeing an unprecedented degree of Black participation in American political life, Reconstruction was ultimately frustrating for African Americans, and the rebirth of white supremacy —including the rise of racist organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan (KKK)—had triumphed in the South by 1877.

Almost a century later, resistance to the lingering racism and discrimination in America that began during the slavery era led to the civil rights movement of the 1960s, which achieved the greatest political and social gains for Black Americans since Reconstruction.

Ana Lucia Araujo , a historian of slavery and the Atlantic slave trade, edited and contributed to this article. Dr. Araujo is currently Professor of History at Howard University in Washington, D.C., and member of the International Scientific Committee of the UNESCO Routes of Enslaved Peoples Projects. Her three more recent books are Reparations for Slavery and the Slave Trade: A Transnational and Comparative History , The Gift: How Objects of Prestige Shaped the Atlantic Slave Trade and Colonialism , and Humans in Shackles: An Atlantic History of Slavery .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- About OAH Magazine of History

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Exploring Slavery's Roots in Colonial America

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Ira Berlin, Exploring Slavery's Roots in Colonial America, OAH Magazine of History , Volume 17, Issue 3, April 2003, Pages 3–4, https://doi.org/10.1093/maghis/17.3.3

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The history of slavery in the United States has long been tethered to the American Civil War. For years, it appeared the only reason American historians evinced interest in slavery was as a cause of that war. Except for a few articles in the Journal of Negro History and the work of pioneer historians of African American life like Herbert Aptheker, Lorenzo Greene, Luther P. Jackson, and Benjamin Quarles, little was written about slavery prior to the 1830s and hardly anything about seven-teenth- and eighteenth-century slavery. Even when the Civil Rights Movement stirred new interest in slavery as a first cause of America's racial dilemma, historians kept their focus on the nineteenth century, particularly the decades between 1830 and 1860. The works of Kenneth Stampp, Stanley Elkins, John Blassingame, Eugene D. Genovese, and Robert Fogel and Stanley Engerman—although in sharp disagreement—uniformly maintained a nineteenth-century focus and rarely addressed the years prior to 1830.

Organization of American Historians members

Personal account.

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| November 2016 | 1 |

| December 2016 | 6 |

| February 2017 | 1 |

| April 2017 | 1 |

| August 2017 | 2 |

| October 2017 | 1 |

| December 2017 | 4 |

| January 2018 | 1 |

| February 2018 | 3 |

| March 2018 | 8 |

| April 2018 | 3 |

| June 2018 | 1 |

| July 2018 | 2 |

| August 2018 | 2 |

| September 2018 | 3 |

| October 2018 | 5 |

| November 2018 | 4 |

| December 2018 | 3 |

| January 2019 | 2 |

| February 2019 | 5 |

| May 2019 | 5 |

| July 2019 | 2 |

| August 2019 | 2 |

| September 2019 | 2 |

| December 2019 | 1 |

| March 2020 | 22 |

| April 2020 | 1 |

| June 2020 | 1 |

| July 2020 | 1 |

| August 2020 | 2 |

| October 2020 | 3 |

| June 2021 | 2 |

| April 2022 | 1 |

| August 2022 | 2 |

| April 2023 | 1 |

| May 2023 | 9 |

| June 2023 | 2 |

| August 2023 | 2 |

| January 2024 | 1 |

| February 2024 | 1 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via, affiliations.

- Online ISSN 1938-2340

- Print ISSN 0882-228X

- Copyright © 2024 Organization of American Historians

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

Antecedents and Models

Slavery is often termed "the peculiar institution," but it was hardly peculiar to the United States. Almost every society in the history of the world has experienced slavery at one time or another. The aborigines of Australia are about the only group that has so far not revealed a past mired in slavery—and perhaps the omission has more to do with the paucity of the evidence than anything else. To explore American slavery in its full international context, then, is essentially to tell the history of the globe. That task is not possible in the available space, so this essay will explore some key antecedents of slavery in North America and attempt to show what is distinctive or unusual about its development. The aim is to strike a balance between identifying continuities in the institution of slavery over time while also locating significant changes. The trick is to suggest preconditions, anticipations, and connections without implying that they were necessarily determinations (1).

Significant precursors to American slavery can be found in antiquity, which produced two of only a handful of genuine slave societies in the history of the world. A slave society is one in which slaves played an important role and formed a significant proportion (say, over 20 percent) of the population. Classical Greece and Rome (or at least parts of those entities and for distinct periods of time) fit this definition and can be considered models for slavery's expansion in the New World. In Rome in particular, bondage went hand in hand with imperial expansion, as large influxes of slaves from outlying areas were funneled into large-scale agriculture, into the latifundia , the plantations of southern Italy and Sicily. American slaveholders could point to a classical tradition of reconciling slavery with reason and universal law; ancient Rome provided important legal formulas and justifications for modern slavery. Parallels between ancient and New World slavery abound: from the dehumanizing device of addressing male slaves of any age as "boy," the use of branding and head shaving as modes of humiliation, the comic inventiveness in naming slaves (a practice American masters continued simply by using classical names), the notion that slaves could possess a peculium (a partial and temporary capacity to enjoy a range of goods), the common pattern of making fugitive slaves wear a metal collar, to clothing domestic slaves in special liveries or uniforms. The Life of Aesop , a fictional slave biography from Roman Egypt in the first century CE, is revelatory of the anxieties and fears that pervade any slave society, and some of the sexual tensions so well displayed are redolent of later American slavery. Yet, of course, ancient slavery was fundamentally different from modern slavery in being an equal opportunity condition —all ethnicities could be slaves—and in seeing slaves as primarily a social, not an economic, category. Ancient cultural mores were also distinctive: Greeks enslaved abandoned infants; Romans routinely tortured slaves to secure testimony; and even though the Stoics were prepared to acknowledge the humanity of the slave, neither they nor anyone else in the ancient world ever seriously questioned the place of slavery in society. Aristotle, after all, thought that some people were "slaves by nature," that there were in effect natural slaves (2).

Africa and the Slave Trade