- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

A newer edition of this book is available.

- < Previous chapter

11 Conclusion and overview

- Published: September 2013

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Substance addiction is a chronic relapsing disorder. Individuals abuse substances for different reasons. There may be personal and mitigating circumstances that lead people to substance abuse (e.g. stress or unhappiness). People may also be at increased risk of initiating substance abuse due to their age. The commencement of adolescence, for example, is a unique period of neurobiological development. Compared to children and adults, adolescents exhibit a number of psychological traits, such as risky and reward-seeking behaviour. The emergence of these traits may reflect the relatively early functional development of brain limbic affective and reward systems compared to the prefrontal cortex. As such, the period of adolescence may confer a vulnerability to the onset of drug misuse and addiction due to developmental changes in neurobiology, which seem to encourage reward-centred and risky decision-making behaviour.

Additionally, there are genetic risks for substance abuse. Twin registry and adoption studies, for example, have shown that the heritability of alcoholism may be as high as 50–60%. Whatever the cause, substance abuse and dependence confers significant social, mental, and medical impairment in those individuals afflicted, together with huge economic costs to society.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Pathways of Addiction: Opportunities in Drug Abuse Research (1996)

Chapter: 1. introduction, 1 introduction.

Drug abuse research became a subject of sustained scientific interest by a small number of investigators in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Despite their creative efforts to understand drug abuse in terms of general advances in biomedical science, the medical literature of the early twentieth century is littered with now-discarded theories of drug dependence, such as autointoxication and antibody toxins, and with failed approaches to treatment. Eventually, escalating social concern about the use of addictive drugs and the emergence of the biobehavioral sciences during the post-World War II era led to a substantial investment in drug abuse research by the federal government (see Appendix B ). That investment has yielded substantial advances in scientific understanding about all facets of drug abuse and has also resulted in important discoveries in basic neurobiology, psychiatry, pain research, and other related fields of inquiry. In light of how little was understood about drug abuse such a short time ago, the advances of the past 25 years represent a remarkable scientific accomplishment. Yet there remains a disconnect between what is now known scientifically about drug abuse and addiction, the public's understanding of and beliefs about abuse and addiction, and the extent to which what is known is actually applied in public health settings.

During its brief history, drug abuse research has been supported mainly by the federal government, with occasional investments by major private foundations. At the federal level, the lead agency for drug abuse research is the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), which supports

85 percent of the world's research on drug abuse and addiction. Other sponsoring agencies include the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), all in the Department of Health and Human Services; as well as the Office of Justice Programs (OJP) in the Department of Justice. Throughout the federal government, the FY 1995 investment in drug abuse research and development was $542.2 million, which represents 4 percent of the $13.3 billion spent by the federal government on drug abuse (ONDCP, 1996). By comparison, $8.5 billion (64 percent of the FY 1995 budget) was spent on criminal justice programs, 1 $2.7 billion (20 percent) on treatment of drug abuse, and $1.6 billion (12 percent) on prevention efforts.

In 1992, the General Accounting Office (GAO) released a report Drug Abuse Research: Federal Funding and Future Needs, which recommended that Congress review the place of research in drug control policy and its modest 4 percent share of the drug control budget. The report questioned whether the federal commitment to research was adequate, given the enormity of research needs (GAO, 1992), and whether adequate evaluation research was being conducted to determine the efficacy of various drug control programs. In FY 1995, drug abuse research was still little more than 4 percent of the entire drug control budget.

In January 1995, NIDA requested the Institute of Medicine (IOM) to examine accomplishments in drug abuse research and provide guidance for future research opportunities. This report by the IOM Committee on Opportunities in Drug Abuse Research focuses broadly on opportunities and priorities for future scientific research in drug abuse. After a brief review of major accomplishments in drug abuse research, the remainder of this chapter discusses the vocabulary and basic concepts used in the report, highlights the importance of the nation's investment in drug abuse research, and explores some of the factors that could improve the yield from that investment.

MAJOR ACHIEVEMENTS IN DRUG ABUSE RESEARCH

There have been remarkable achievements in drug abuse research over the past quarter of a century as researchers have learned more about the biological and psychosocial aspects of drug use, abuse, and dependence. Behavioral researchers have developed animal and human mod-

els of drug-seeking behavior, that have, for example, yielded objective measures of initiation and repeated administration of drugs, thereby providing the scientific foundation for assessments of "abuse liability" (i.e., the potential for abuse) of specific drugs (see Chapter 2 ). This information is an essential predicate for informed regulatory decisions under the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act and the Controlled Substances Act. Taking advantage of technological advances in molecular biology, neuroscientists have identified receptors or receptor types in the brain for opioids, cocaine, benzodiazepines, and marijuana and have described the ways in which the brain adapts to, and changes after, exposure to drugs. Those alterations, which may persist long after the termination of drug use, appear to involve changes in gene expression. They may explain enhanced susceptibility to future drug exposure, thereby shedding light on the enigmas of withdrawal and relapse at the molecular level (see Chapter 3 ). Epidemiologists have designed and implemented epidemiological surveillance systems that enable policymakers to monitor patterns of drug use in the population ( Chapter 4 ) and that enable researchers to investigate the causes and consequences of drug use and abuse (Chapters 5 and 7 , respectively). Paralleling broader trends in health promotion and disease prevention in the past 20 years, the field of drug abuse prevention has made significant progress in evaluating the effectiveness of interventions implemented in a range of settings including communities, schools, and families (see Chapter 6 ).

Marked gains have also been made in treatment research, including improvements in diagnostic criteria; development of a wide range of treatment interventions and sophisticated methods to assess treatment outcome; and development and approval of Leo-alpha-acetylmethadol (LAAM), a medication for the treatment of opioid dependence. Pharmacological and psychosocial treatments, alone or in combination, have been shown to be effective for drug dependencies, and treatment has been shown to reduce drug use, HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) infection rates, health care costs, and criminal activity (see Chapter 8 ).

Drug abuse researchers have also made major contributions to knowledge in adjacent fields of scientific inquiry. For example, NIDA-sponsored research was the driving force in the identification of morphine-like substances that serve as neurotransmitters in specific neurons located throughout the central and peripheral nervous systems (Orson et al., 1994). Identification of these substances represents a dramatic breakthrough in understanding the mechanisms of pain, reinforcement, and stress. Additionally, the discovery of opioid peptides as neurotransmitters played a key role in the identification of numerous other peptide neurotransmitters (Cooper et al., 1991; Goldstein, 1994; Hokfelt et al., 1995). These discoveries have broadened the understanding of brain function and now

form the basis of many current strategies in the design of new drug treatments for neuropsychiatric disorders. Additionally, drug abuse research has contributed to the development of brain imaging techniques.

Drug abuse research has also provided a major impetus for neuropharmacological research in psychiatry since the late 1950s, when it was discovered that LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide; a hallucinogen that produces psychotic symptoms) affected the brain's serotonin systems (Cooper et al., 1991). That seminal discovery stimulated decades of research in the neuropharmacological basis of behavior and psychiatric disorders. The impact on antipsychotic research has been dramatic. In addition, stimulants (e.g., cocaine and amphetamine) were found to produce a state of paranoid psychosis, resembling schizophrenia, in some people. The actions of stimulants on the brain's dopamine pathways continue to inform researchers of the potential role of those pathways in the treatment, and perhaps the pathophysiology, of schizophrenia (Kahn and Davis, 1995). Drug abuse research also has had an impact on antidepressant research (e.g., the actions of drugs of abuse on the brain's serotonin systems have provided useful models with which to investigate the role of those systems in depression and mania). Depression is a risk factor for treatment failure in smoking cessation (Glassman et al., 1993) and depression-like symptoms are dominant during cocaine withdrawal (DiGregorio, 1990). Consequently, treatment of depression in nicotine and cocaine-dependent individuals has been an area of interest for drug abuse research.

Some drugs that are abused, most notably the opioid analgesics, have essential medical uses. Since its founding, NIDA has been the major supporter of research into brain mechanisms of pain and analgesia, analgesic tolerance, and analgesic pharmacology. The resulting discoveries have led to an understanding of which brain circuits are required to generate pain and pain relief (Wall and Melzack, 1994), have revolutionized the treatment of postoperative and cancer pain (Folly and Interesse, 1986; Car et al., 1992; Jacob et al., 1994), and have led to improved treatments for many other conditions that result in chronic pain (see Chapter 3 ).

VOCABULARY OF DRUG ABUSE

Ordinarily, scientific vocabulary evolves toward greater clarity and precision in response to new empirical discoveries and reconceptualizations. That creative process is evident within each of the disciplines of drug abuse research covered in various chapters of this report. Interestingly, however, the words describing the field as a whole, and connecting each chapter to the next, seem to defy the search for clarity and precision. Does "drug" include alcohol and tobacco? What is "abuse"? Are use and

abuse mutually exclusive categories? Are abuse and dependence mutually exclusive categories? Does use of illicit drugs per se amount to abuse? Does abuse include underage use of nicotine? Is addiction synonymous with dependence?

These ambiguities have persisted for decades because the vocabulary of drug abuse is inevitably influenced by peoples' attitudes and values. If the task were solely a scientific one, precise terminology would have emerged long before now. However, because the choice of words in this field always carries a nonscientific message, scientists themselves cannot always agree on a common vocabulary.

Consider the case of nicotine; from a pharmacological standpoint, nicotine is functionally similar to other psychoactive drugs. However, many researchers and policymakers choose to exclude nicotine from the category of drug. The same is true of alcohol; for example, other terms, such as ''chemical dependency" or "substance abuse," are often used as generic terms encompassing the abuse of nicotine and alcohol as well as abuse of illicit drugs. This semantic strategy is chosen to signify the difference in legal status among alcohol, nicotine, and illicit drugs. In recent years, however, a growing number of researchers have adopted a more inclusive use of the term drug. In the case of nicotine, this move tends to reflect a policy judgment that nicotine should be classified as a drug under the federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act.

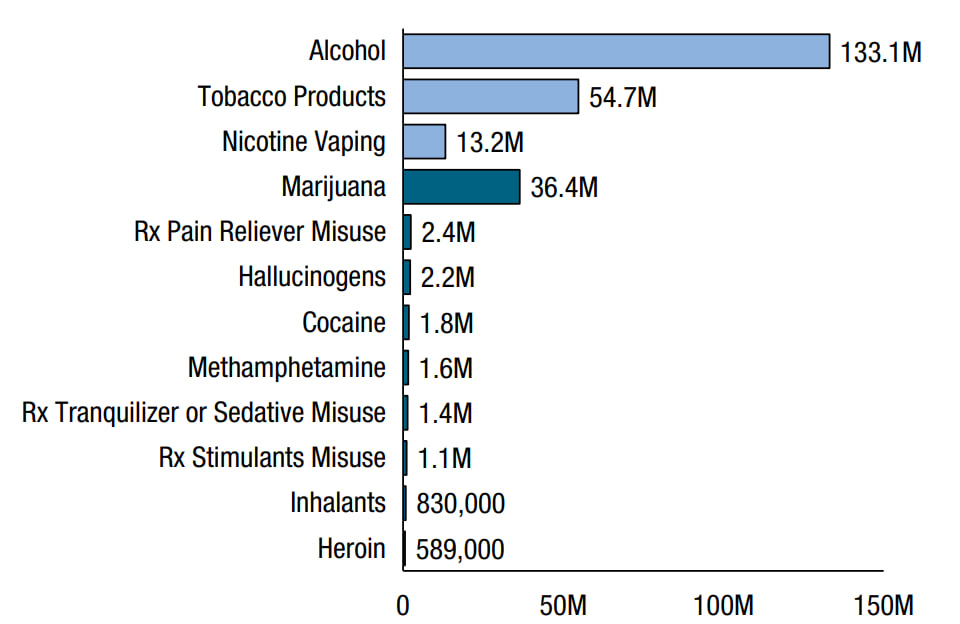

In the committee's view, the term drug should be understood, in its generic sense, to encompass alcohol and nicotine as well as illicit drugs. It is very important for the general public to recognize that alcohol and nicotine constitute, by far, the nation's two largest drug problems, whether measured in terms of morbidity, mortality, or social cost. Abuse of and dependence on those drugs have serious individual and societal consequences. Continued separation of alcohol, nicotine, and illicit drugs in everyday speech is an impediment to public education, prevention, and therapeutic progress.

Although the committee uses the term drug, in its generic sense, to encompass alcohol and nicotine, the report focuses, at NIDA's request, on research opportunities relating to illicit drugs; research on alcohol and nicotine is discussed only when the scientific inquiries are intertwined. Because the report sometimes ranges more broadly than illicit drugs, however, the committee has adopted several semantic conventions to promote clarity and avoid redundancy. First, the term drug, unmodified, refers to all psychoactive drugs, including alcohol and nicotine. When reference is intended solely to illicit drugs such as heroin, cocaine, and other drugs regulated by the Controlled Substances Act, the committee says so explicitly. Occasionally, to ensure that the intended meaning is clear, the report refers to "illicit drugs and nicotine" or to "illicit drugs

and alcohol," as the case may be. Additionally, the words opiate and opioid are used interchangeably, although opiates are derivative of morphine and opioids are all compounds with morphine-like properties (they may be synthetic and not resemble morphine chemically).

The report employs the standard three-stage conceptualization of drug-taking behavior that applies to all psychoactive drugs, whether licit or illicit. Each stage—use, abuse, dependence—is marked by higher levels of use and increasingly serious consequences. Thus, when the report refers to the "use" of drugs, the term is usually employed in a narrow sense to distinguish it from intensified patterns of use. Conversely, the term "abuse" is used to refer to any harmful use, irrespective of whether the behavior constitutes a "disorder'' in the DSM-IV diagnostic nomenclature (see Appendix C ). When the intent is to emphasize the clinical categories of abuse and dependence, that is made clear.

The committee also draws a clear distinction between patterns of drug-taking behavior, however described, and the harmful consequences of that behavior for the individual and for society. These consequences include the direct, acute effects of drug taking such as a drug-induced toxic psychosis or impaired driving, the effects of repeated drug taking on the user's health and social functioning, and the effects of drug-seeking behavior on the individual and society. It bears emphasizing that adverse consequences can be associated with patterns of drug use that do not amount to abuse or dependence in a clinical sense, although the focus of this report and the committee's recommendations is on the more intensified patterns of use (i.e., abuse and dependence) since they cause the majority of the serious consequences.

DEFINITIONS AND BASIC CONCEPTS

Drug use may be defined as occasional use strongly influenced by environmental factors. Drug use is not a medical disorder and is not listed as such in either of the two most important diagnostic manuals—the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSMIV; APA, 1994); or the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10; WHO, 1992). (See Appendix C for DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnostic criteria.) Drug use implies intake for nonmedical purposes; it may or may not be accompanied by clinically significant impairment or distress on a given occasion.

Drug abuse is characterized in DSM-IV as including regular, sporadic, or intensive use of higher doses of drugs leading to social, legal, or interpersonal problems. Like DSM-IV, ICD-10 identifies a nondependent but problematic syndrome of drug use but calls it "harmful use" instead

of abuse. This syndrome is defined by ICD-10 as use resulting in actual physical or psychological harm.

Drug dependence (or addiction) is characterized in both DSM-IV and ICD-10 as drug-seeking behavior involving compulsive use of high doses of one or more drugs, either licit or illicit, for no clear medical indication, resulting in substantial impairment of health and social functioning. Dependence is usually accompanied by tolerance and withdrawal 2 and (like abuse) is generally associated with a wide range of social, legal, psychiatric, and medical problems. Unlike patients with chronic pain or persistent anxiety, who take medication over long periods of time to obtain relief from a specific medical or psychiatric disorder (often with resulting tolerance and withdrawal), persons with dependence seek out the drug and take it compulsively for nonmedical effects.

Tolerance occurs when certain medications are taken repeatedly. With opiates for example, it can be detected after only a few days of use for medical purposes such as the treatment of pain. If the patient suddenly stops taking the drug, a withdrawal syndrome may ensue. Physicians often confuse this phenomenon, referred to as physical dependence, with true addiction. That can lead to withholding adequate medication for the treatment of pain because of the very small risk that addiction with drug-seeking behavior may occur.

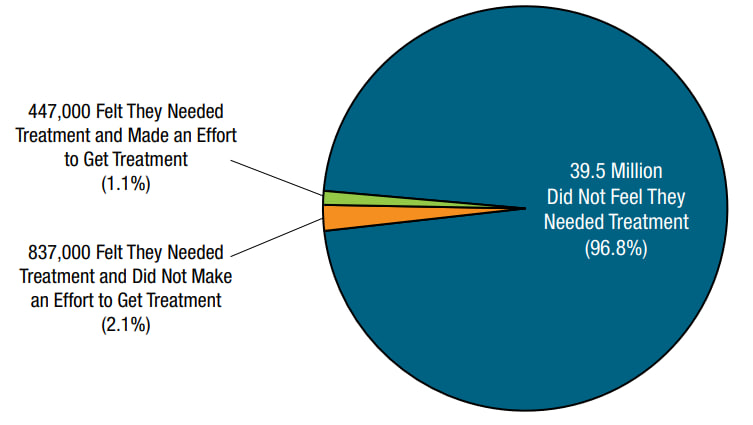

As a consequence of its compulsive nature involving the loss of control over drug use, dependence (or addiction) is typically a chronically relapsing disorder (IOM, 1990, 1995; Meter, 1996; O'Brien and McLennan, 1996; McLennan et al., in press). Although individuals with drug dependence can often complete detoxification and achieve temporary abstinence, they find it very difficult to sustain that condition and avoid relapse over time. Most persons who achieve sustained remission do so only after a number of cycles of detoxification and relapse (Dally and Marital, 1992). Relapse is caused by a constellation of biological, family, social, psychological, and treatment factors and is demonstrated by the fact that at least half of former cigarette smokers quit three or more times before they successfully achieve stable remission from nicotine addiction (Schilling, 1992). Similarly, within one year of treatment, relapse occurs in 30-50 percent of those treated for drug dependence, although the level

of drug use may not be as high as before treatment (Daley and Marlatt, 1992; McLellan et al., in press). Unlike those who use (or even abuse) drugs, individuals with addiction have a substantially diminished ability to control drug consumption, a factor that contributes to their tendency to relapse.

Another terminological issue arises in relation to the terms addiction and dependence. For some scientists, the proper terms for compulsive drug seeking is addiction, rather than dependence. In their view, addiction more clearly signifies the essential behavioral differences between compulsive use of drugs for their nonmedical effects and the syndrome of "physical dependence" that can develop in connection with repeated medical use. In response, many scientists argue that dependence has been defined in both ICD-10 and DSM-IV to encompass the behavioral features of the disorder and has become the generally accepted term in the diagnostic nomenclature. Moreover, some scientists object to the term addiction on the grounds that it is associated with stigmatizing social images and that a less pejorative term would help to promote public understanding of the medical nature of the condition. The committee has not attempted to resolve this controversy. For purposes of this report, the terms addiction and dependence are used interchangeably.

An inherent aspect of drug addiction is the propensity to relapse. Relapse should not be viewed as treatment failure; addiction itself should be considered a brain disease similar to other chronic and relapsing conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and asthma (IOM, 1995; O'Brien and McLellan, 1996). In the latter, significant improvement is considered successful treatment even though complete remission or cure is not achieved. In the area of drug abuse, however, many individuals (both lay and professional) expect treatment programs to perform like vaccine programs, where one episode of treatment offers lifetime immunity. Not surprisingly, because of that expectation, people are inevitably disappointed in the relatively high relapse rates associated with most treatments. If, however, addiction is understood as a chronically relapsing brain disease, then—for any one treatment episode—evidence of treatment efficacy would include reduced consumption, longer abstention periods, reduced psychiatric symptoms, improved health, continued employment, and improved family relations. Most of those results are demonstrated regularly in treatment outcome studies.

The idea that drug addiction is a chronic relapsing condition, requiring long-term attention, has been resisted in the United States and in some other countries (Brewley, 1995). Many lay people view drug addiction as a character defect requiring punishment or incarceration. Proponents of the medical model, however, point to the fact that addiction is a distinct morbid process that has characteristics and identifiable signs and

symptoms that affect organ systems (Miller, 1991; Meter, 1996). Characterization of addiction as a brain disease is bolstered by evidence of genetic vulnerability to addiction, physical correlates of its clinical course, physiological changes as a result of repeated drug use, and fundamental changes in brain chemistry as evidenced by brain imaging (Volkow et al., 1993). This is not to say that behavioral, social, and environmental factors are immaterial—they all play a role in onset and outcome, just as they do in heart disease, kidney disease, tuberculosis, or other infectious diseases. Thus, the contemporary understanding of disease fully incorporates the voluntary behavioral elements that lead many people to be skeptical about the applicability of the medical model to drug addiction. In any case, the committee embraces the disease concept, not because it is indisputable but because this paradigm facilitates scientific investigation in many important areas of knowledge, without inhibiting or distorting scientific inquiry in other parts of the field.

IMPORTANCE OF DRUG ABUSE RESEARCH

The widespread prevalence of illicit drug use in the United States is well documented in surveys of households, students, and prison and jail inmates ( Chapter 4 ). Based on the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (NHSDA), an annual survey presently sponsored by SAMHSA, it was estimated that in 1994, 12.6 million people had used illicit drugs (primarily marijuana) in the past month (SAMHSA, 1995). That figure represents 6 percent of the population 12 years of age or older. 3 The number of heavy drug users, using drugs at least once a week, is difficult to determine. It has been estimated that in 1993 there were 2.1 million heavy cocaine users and 444,000-600,000 heavy heroin users (Rhodes et al., 1995). This population represents a significant burden to society, not only in terms of federal expenditures but also in terms of costs related to the multiple consequences of drug abuse (see Chapter 7 ).

The ultimate aim of the nation's investment in drug abuse research is to enable society to take effective measures to prevent drug use, abuse, and dependence, and thereby reduce its adverse individual and social consequences and associated costs. The adverse consequences of drug abuse are numerous and profound and affect the individual's physical health and psychological and social functioning. Consequences of drug abuse include increased rates of HIV infection and tuberculosis (TB); education and vocational impairment; developmental harms to children of

drug-using parents associated with fetal exposure or maltreatment and neglect; and increased violence (see Chapter 7 ). It now appears that injection drug use is the leading risk factor for new HIV infection in the United States (Holmberg, 1996). Most (80 percent) HIV-infected heterosexual men and women who do not use injection drugs have been infected through sexual contact with HIV-infected injection drug users (IUDs). Thus, it is not surprising that the geographic distribution of heterosexual AIDS cases has been essentially the same as the distribution of male injection drug users' AIDS cases (Holmberg, 1996) Further, the IUDs-associated HIV epidemic in men is reflected in the heterosexual epidemic in women, which is reflected in HIV infection in children (CDC, 1995). Nearly all children who acquire HIV infection do so prenatal (see Chapter 7 ).

The extent of the impact of drug use and abuse on society is evidenced by its enormous economic burden. In 1990, illicit drug abuse is estimated to have cost the United States more than $66 billion. When the cost of illicit drug use and abuse is tallied with that of alcohol and nicotine ( Table 1.1 ), the collective cost of drug use and abuse exceeds the estimated annual $117 billion cost of heart disease and the estimated annual $104 billion cost of cancer (AHA, 1992; ACS, 1993; D. Rice, University of California at San Francisco, personal communication, 1995).

As noted above, the federal government accounts for a large segment of the societal expenditure on illicit drug abuse control—spending more than $13.3 billion in FY 1995 (ONDCP, 1996). About two-thirds was devoted to interdiction, intelligence, incarceration, and other law enforcement activities. Research, however, accounts for only 4 percent of federal outlays, a percentage that has remained virtually unchanged since 1981 (ONDCP, 1996) ( Figure 1.1 ). Given the social costs of illicit drug abuse and the enormity of the federal investment in prevention and control, research into the causes, consequences, treatment, and prevention of drug abuse should have a higher priority. Enhanced support for drug abuse research would be a socially sound investment, because scientific research can be expected to generate new and improved treatments, as well as prevention and control strategies that can help reduce the enormous social burden associated with drug abuse.

THE CONTEXT OF DRUG ABUSE RESEARCH

In the chapters that follow, the committee identifies research initiatives that seem most promising and most likely to lead to successful efforts to reduce drug abuse and its associated social costs. Although the yield from these initiatives will depend largely on the creativity and skill of scientists, the many contextual factors that will also have a major bear-

TABLE 1.1 Estimated Economic Costs (million dollars) of Drug Abuse, 1990

FIGURE 1.1 Federal drug control budget trends (1981-1995). NOTE: Figures are in current dollars. SOURCE: ONDCP (1996).

ing on the payoff from scientific inquiry cannot be ignored. The committee has identified six major factors that, if successfully addressed, could optimize the gains made in each area of drug abuse research: stable funding; use of a comprehensive public health framework; wider acceptance of a medical model of drug dependence; better translation of research findings into practice; raising the status of drug abuse research; and facilitating interdisciplinary research.

Stable Funding

A stable level of funding in any area of biomedical research is needed to sustain and build on research accomplishments, to retain a cadre of experts in a field, and to attract young investigators. Drug abuse research, in comparison with many other research venues, has not enjoyed consistent federal support (IOM, 1990, 1995; see also Appendix B ). The field has suffered from difficulties in recruiting and retaining young researchers and clinicians and in maintaining a stable research infrastructure (IOM, 1995). Society's capacity to contain and manage drug abuse

depends upon a stable, long-term investment in research. The vicissitudes in federal research funding often reflect changing currents in public opinion toward drugs and drug users ( Appendix B ). However, drug abuse will not disappear; it is an endemic social and public health problem. The nation must commit itself to a sustained effort. The social investment in research is an investment in "human capital" that must be sustained over the long term in order to reap the expected gains. An investment in this field is squandered if researchers who have been recruited and trained in drug abuse research are drawn to other fields because of uncertainty about the stability of future funding.

Adoption of a Comprehensive Public Health Framework

The social impact of drug abuse research can be enhanced significantly by conceptualizing goals and priorities within a comprehensive public health framework (Goldstein, 1994). All too often, public discourse about drug abuse is characterized by such unnecessary and fruitless disputes as whether drug abuse should be viewed as a social and moral problem or a health problem, whether the drug problem can best be solved by law enforcement or by medicine, whether priority should be placed on reducing supply or reducing demand, and so on. The truth is that these dichotomies oversimplify a brain disease impacted by a complex set of behaviors and a diverse array of potentially useful social responses. Forced choices of this nature also tend to inhibit or foreclose potentially useful research strategies. Confusion about social goals can lead to confusion about research priorities and can obscure the links between investigations viewing the subject through different lenses.

Some issues tend to recur. A prominent dispute centers on whether preventing drug use is important in itself or whether society should be more concerned with abuse or with the harmful consequences of use. The answer, of course, is that such a forced choice obscures, rather than clarifies, the issues. From a public health standpoint, drug use is a risk factor; the significance of use (whether of alcohol, nicotine, or illicit drugs) lies in the risk of harm associated with it (e.g., fires from smoking, impaired driving from alcohol or illicit drugs, or developmental setbacks) and in the risk that use will intensify, escalating to abuse or dependence. Those risks vary widely in relation to drug, user characteristics, social context, etc. Attention to the consequences of use and to the risk of escalation helps to set priorities (for research and policy) and provides a framework for assessing the impact of different interventions.

From a public policy standpoint, arguments about goals and priorities are fraught with controversy. From the standpoint of research strategy, however, the key lies in asking the right questions (e.g., What influ-

ences the pathways from use, to abuse, to dependence? What are the effects of needle exchange programs on illicit drug use and on HIV disease?) and in generating the knowledge required to facilitate informed policy debate. The main virtues of a comprehensive public health approach are that it helps to disentangle scientific questions from policy questions and that it encompasses all of the pertinent empirical questions, including the causes and consequences of use, abuse, and dependence, as well as the efficacy and cost of all types of interventions. In sum, the social payoff from drug abuse research can be enhanced substantially by integrating diverse strands of inquiry within a public health framework.

Acceptance of a Medical Model of Drug Dependence

Drug dependence is a chronic, relapsing brain disease that, like other diseases, can be evaluated and treated with the standard tools of medicine, including efforts in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment with medications and behavioral or psychosocial therapies. Unfortunately, the medical model of dependence is not universally accepted by health professionals and others in the treatment community; it is widely rejected within the law enforcement community and often by the public at large, which tends to view the complex and varied patterns of use, abuse, and dependence as an undifferentiated behavior rather than a medical problem.

Resistance to the medical model takes many forms. One is resistance to pharmacotherapies, such as methadone, that are seen as substituting licit drugs for illicit drugs without changing drug-taking behavior. Conversely, treatment approaches that adopt a rigid drug-free strategy preclude the use of medications for patients with other psychiatric disorders that are easily treated by pharmacotherapeutic approaches. On a subtler level, resistance to the use of pharmacotherapies is evidenced by the routine use of inadequate doses of methadone (D'Aunno and Vaughn, 1992). Finally, for others, all forms of drug abuse signify a failure of willpower or a moral weakness requiring punishment, incarceration, or moral education rather than treatment (Anglin and Hser, 1992).

Resistance to the medical model of drug dependence presents numerous barriers to research. Clinical researchers experience difficulty in soliciting participation by both treatment program administrators and patients, who are sometimes mistrustful of researchers' motives. If research involves a medication that is itself prone to abuse, there are additional regulatory requirements for drug scheduling, storage, and record keeping that act to discourage investigation (see Chapter 10 ; IOM, 1995). The ever-present threat of inappropriate intrusion by law enforcement agents has a chilling effect on treatment research (McDuff et al., 1993). All barri-

ers to inquiry, irrespective of whether they are legal or social in origin, raise the cost of research and discourage researchers from entering the field. Additionally, those barriers diminish the likelihood that a pharmaceutical company will invest in the development of antiaddiction medications (IOM, 1995). 4 Broader acceptance of the medical model of drug dependence would provide an incentive for researchers and clinicians to enter this field of research. Over time, a developing consensus in support of the medical model could facilitate common discourse, help to shape a shared research agenda within a public health framework, and diminish tensions between the research and treatment communities and the criminal justice system.

Better Translation of Research Findings into Practice and Policy

To benefit society, new research findings must be disseminated adequately to treatment providers, educators, law enforcement officials, and community leaders. In the case of prevention practices, it is often difficult for communities to change entrenched policies, particularly when combined with political imperatives for action to counteract drug abuse. In the case of treatment, technology transfer is impeded by the heterogeneity of providers and their marginalization at the outskirts of the medical community (see IOM, 1990, 1995; see also Chapter 8 ). Physicians and psychiatrists are seldom employed by specialized drug treatment facilities (approximately one-quarter employ medical doctors), and treatment is delivered by counselors whose training and supervision vary greatly and who have little access to and understanding of research results (Ball and Ross, 1991; Batten et al., 1993). These factors not only impede the transfer of research findings to the field but also impede communication from the field to the laboratory so that research designs can be modified in response to clinical realities (Pentz, 1994). Thus, there is a real need for bidirectional communication, from bench to bedside and back to the basic scientist (IOM, 1994).

The committee is aware, however, of recent technology transfer efforts in the field such as the Treatment Improvement Protocol Series, an initiative to establish guidelines for drug abuse treatment with an emphasis on incorporating research findings (SAMHSA, 1993), and the Prevention Enhancement Protocol System, a process implemented by the Center

for Substance Abuse Prevention in which scientists and practitioners develop protocols to identify and evaluate the strength of evidence on topics related to prevention interventions. Similar efforts will be invaluable for communicating and integrating research results to the treatment community.

Research frequently results in product development leading to changes in operations and an overall enhancement of the value of the enterprise. For example, in the pharmaceutical industry research often leads to the development of new medications or devices. In the public sector, however, research is often divorced from the implementation of findings and development. Research is often more basic than applied, and the fruits of research are not realized by the government, but by the private sector. Although that approach may be appropriate, it is unfortunately not always the most productive strategy for advancing research, knowledge, and product development. That is particularly true in the development of medications for opiate and cocaine addictions, where there is a great need for commitment from the private sector. However, many obstacles prevent active involvement of the pharmaceutical industry in this area of research and development (IOM, 1995).

A similar problem arises in relation to policymaking. Because debates about drug policy tend to be so highly polarized and politicized, research findings are often distorted, or selectively deployed, for rhetorical purposes. Researchers cannot prevent this practice, which is a common feature of political debate in a democratic society. However, researchers and their sponsors should not be indifferent to the disconnect between policy discourse and science. Researchers should establish and support institutional mechanisms for communicating an important message to policymakers and to the general public. Scientific research has produced a solid, and growing, body of knowledge about drug abuse and about the efficacy of various interventions that aim to prevent and control it. As long as drug abuse remains a poorly understood social problem, policy will be based mainly on wish and supposition; steps should be taken to educate policymakers about the scientific and technological advances in addiction research. Only then will it be possible for policymaking to support legislation that adequately funds new research and applies research findings. To some extent, persisting failure to reap the fruits of drug abuse research is attributable to the low visibility of the field—a problem to which the discussion now turns.

Raising the Status of Drug Abuse Research

Drug abuse research is often an undervalued area of inquiry, and most scientists and clinicians choose other disciplines in which to develop

their careers. Compared with other fields of research, investigators in drug abuse are often paid less, have less prestige among their peers, and must contend with the unique complexities of performing research in this area (e.g., regulations on controlled substances) (see IOM, 1995). The overall result is an insufficient number of basic and clinical researchers. IOM has recently begun a study, funded by the W. M. Keck Foundation of Los Angeles, to develop strategies to raise the status of drug abuse research. 5

Weak public support for this field of study is evident in unstable federal funding (see above), a lack of pharmaceutical industry investment in the development of antiaddiction medications (IOM, 1995), and inadequate funding for research training (IOM, 1995). NIDA's FY 1994 training budget, which is crucial to the flow of young researchers into the field, was about 2 percent of its extramural research budget, a percentage substantially lower than the overall National Institutes of Health (NIH) training budget, which averages 4.8 percent of its extramural research budget.

Beyond funding problems, investigators face a host of barriers to research: research subjects may pose health risks (e.g., TB, HIV/AIDS, and other infectious diseases), may be noncompliant, may deny their drug abuse problems, and may be involved in the criminal justice system. Even when research is successful and points to improvements in service delivery, the positive outcome may not be translated into practice or policy. For example, more than a year after the Food and Drug Administration's (FDA's) approval of levo-alpha-acetylmethadol (LAAM) as the first new medication for the treatment of opiate dependence in over 20 years, fewer than 1,000 patients nationwide actually had received the medication (IOM, 1995). More recently, scientific evidence regarding the beneficial effects of needle exchange programs (NRC, 1995) has received inadequate attention. Continuing indifference to scientific progress in drug abuse research inevitably depresses the status of the field, leading in turn to difficulties in recruiting new investigators.

Increasing Interdisciplinary Research

The breadth of expertise needed in drug abuse research spans many disciplines, including the behavioral sciences, pharmacology, medicine, and the neurosciences, and many fields of inquiry, including etiology, epidemiology, prevention, treatment, and health services research. Aspects of research relating to drug use tend to draw on developmental perspectives and to focus on general population samples in community settings, especially schools. Aspects of research relating to abuse and de-

pendence tend to be more clinical in nature, drawing on psychopathological perspectives. Additionally, a full account of any aspect of drug-taking behavior must also reflect an understanding of social context. The rich interplay between neuroscience and behavioral research and between basic and clinical research poses distinct challenges and opportunities.

Unfortunately, research tends to be fragmented within disciplinary boundaries. The difficulties in conducting successful interdisciplinary research are well known. Funds for research come from many separate agencies, such as the NIDA, NIMH, and SAMHSA. These agencies all have different programmatic emphases as they attempt to shape the direction of research in their respective fields. In times of funding constraints, agencies may be less inclined to fund projects at the periphery of their interests.

Additionally, NIH study sections, which rank grant proposals, are discipline specific, making it difficult for interdisciplinary proposals to ''qualify" (i.e., receive a high rank) for funding. Another problem is that the most advanced scientific literature tends to be compartmentalized within discipline or subject matter categories, making it difficult for scientists to see the whole field. The problem is exacerbated by what Tonry (1990) has called "fugitive literatures," studies carried out by private sector research firms or independent research agencies and available only in reports submitted to the sponsoring agency.

In light of lost opportunities for collaboration and interdisciplinary research, IOM (1995) previously recommended the creation and expansion of comprehensive drug abuse centers to coordinate all aspects of drug abuse research, training, and treatment. The field of drug abuse research presents a real opportunity to bridge the intellectual divide between the behavioral and neuroscience communities and to overcome the logistical impediments to interdisciplinary research.

INVESTING WISELY IN DRUG ABUSE RESEARCH

This report sets forth drug abuse research initiatives for the next decade based on a thorough assessment of what is now known and a calculated judgment about what initiatives are most likely to advance our knowledge in useful ways. This report is not meant to be a road map or tactical battle plan, but is best regarded as a strategic outline. Within each discipline of drug abuse research, the committee has highlighted priorities for future research. However, the committee did not make any attempt to prioritize recommendations across varied disciplines and fields of research. Prudent research planning must respond to newly emerging opportunities and needs while maintaining a steady commitment to the

achievement of long-term objectives. The ability to respond to new goals and needs may be the real challenge for the field of drug abuse research.

Drug abuse research is an important public investment. The ultimate aim of that investment is to reduce the enormous social costs attributable to drug abuse and dependence. Of course, drug abuse research must also compete for funding with research in other fields of public health, research in other scientific domains, and other pressing public needs. Recognizing the scarcity of resources, the committee has also considered ways in which the research effort can be harnessed most effectively to increase the yield per dollar invested. These include stable funding, use of a comprehensive public health framework, wider acceptance of a medical model of drug dependence, better translation of research findings into practice and policy, raising the status of drug abuse research, and facilitating interdisciplinary research.

The committee notes that there have been major accomplishments in drug abuse research over the past 25 years and commends NIDA for leading that effort. The committee is convinced that the field is on the threshold of significant advances, and that a sustained research effort will strengthen society's capacity to reduce drug abuse and to ameliorate its adverse consequences.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

This report sets forth a series of initiatives in drug abuse research. 6 Each chapter of the report covers a segment of the field, describes selected accomplishments, and highlights areas that seem ripe for future research. As noted, the committee has not prioritized areas for future research but, instead, has identified those areas that most warrant further exploration.

Chapter 2 describes behavioral models of drug abuse and demonstrates how the use of behavioral procedures has given researchers the ability to measure drug-taking objectively and to study the development, maintenance, and consequences of that behavior. Chapter 3 discusses drug abuse within the context of neurotransmission; it describes neurobiological advances in drug abuse research and provides the foundation for the current understanding of addiction as a brain disease. The epidemiological information systems designed to gather information on drug use in the United States are identified in Chapter 4 . The data collected from the systems provide an essential foundation for systematic study of

the etiology and consequences of drug abuse, which are addressed, respectively, in Chapters 5 and 7 . Chapter 6 addresses the efficacy of interventions designed to prevent drug abuse. The effectiveness of drug abuse treatment and the difficulties in treating special populations of drug users are discussed in Chapter 8 , while the impact of managed care on access, costs, utilization, and outcomes of treatment is addressed in Chapter 9 . Finally, Chapter 10 discusses the effects of drug control on public health and identifies areas for policy-relevant research.

Specific recommendations appear in each chapter. Although these recommendations reflect the committee's best judgment regarding priorities within the specific domains of research, the committee did not identify priorities or rank recommendations for the entire field of drug abuse research. Opportunities for advancing knowledge exist in all domains. It would be a mistake to invest too narrowly in a few fields of inquiry. At the present time, soundly conceived research should be pursued in all domains along the lines outlined in this report.

ACS (American Cancer Society). 1993. Cancer Facts and Figures, 1993 . Washington, DC: ACS.

AHA (American Heart Association). 1992. 1993 Heart and Stroke Fact Statistics . Dallas, TX: AHA.

Anglin MD, Hser Y. 1992. Treatment of drug abuse. In: Watson RR, ed. Drug Abuse Treatment. Vol. 3, Drug and Alcohol Abuse Reviews . New York: Humana Press.

APA (American Psychiatric Association). 1994. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders . 4th ed. Washington, DC: APA.

Ball JC, Ross A. 1991. The Effectiveness of Methadone Maintenance Treatment . New York: Springer-Verlag.

Batten H, Horgan CM, Prottas J, Simon LJ, Larson MJ, Elliott EA, Bowden ML, Lee M. 1993. Drug Services Research Survey Final Report: Phase I . Contract number 271-90-8319/1. Submitted to the National Institute of Drug Abuse. Waltham, MA: Bigel Institute for Health Policy, Brandeis University.

Brewley T. 1995. Conversation with Thomas Brewley. Addiction 90:883-892.

Carr DB, Jacox AK, Chapman CR, et al. 1992. Acute Pain Management: Operative or Medical Procedures and Trauma. Clinical Practice Guidelines . AHCPR Publication No. 92-0032. Rockville, MD: U.S. Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 1995. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report 7(2).

Cooper JR, Bloom FE, Roth RH. 1991. The Biochemical Basis of Neuropharmacology . 6th ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Daley DC, Marlatt GA. 1992. Relapse prevention: Cognitive and behavioral interventions. In: Lowinson JH, Ruiz P, Millman RB, Langrod JG, eds. Substance Abuse: A Comprehensive Textbook . Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins.

D'Aunno T, Vaughn TE. 1992. Variation in methadone treatment practices. Journal of the American Medical Association 267:253-258.

DiGregorio GJ. 1990. Cocaine update: Abuse and therapy. American Family Physician 41(1):247-250.

Foley KM, Inturrisi CE, eds. 1986. Opioid Analgesics in the Management of Clinical Pain. Advances in Pain Research and Therapy. Vol. 8. New York: Raven Press.