How to Write a Reflective Essay?

07 August, 2020

17 minutes read

Author: Elizabeth Brown

A reflective essay is a personal perspective on an issue or topic. This article will look at how to write an excellent reflexive account of your experience, provide you with reflexive essay framework to help you plan and organize your essay and give you a good grounding of what good reflective writing looks like.

What is a Reflective Essay?

A reflective essay requires the writer to examine his experiences and explore how these experiences have helped him develop and shaped him as a person. It is essentially an analysis of your own experience focusing on what you’ve learned.

Don’t confuse reflexive analysis with the rhetorical one. If you need assistance figuring out how to write a rhetorical analysis , give our guide a read!

Based on the reflective essay definition, this paper will follow a logical and thought-through plan . It will be a discussion that centers around a topic or issue. The essay should strive to achieve a balance between description and personal feelings.

It requires a clear line of thought, evidence, and examples to help you discuss your reflections. Moreover, a proper paper requires an analytical approach . There are three main types of a reflective essay: theory-based, a case study or an essay based on one’s personal experience.

Unlike most academic forms of writing, this writing is based on personal experiences and thoughts. As such, first-person writing position where the writer can refer to his own thoughts and feelings is essential. If the writer talks about psychology or medicine, it is best to use the first-person reference as little as possible to keep the tone objective and science-backed.

To write this paper, you need to recollect and share personal experience . However, there is still a chance that you’ll be asked to talk about a more complex topic.

By the way, if you are looking for good ideas on how to choose a good argumentative essay topic , check out our latest guide to help you out!

The Criteria for a Good Reflective Essay

The convention of an academic reflective essay writing will vary slightly depending on your area of study. A good reflective essay will be written geared towards its intended audience. These are the general criteria that form the core of a well-written piece:

- A developed perspective and line of reasoning on the subject.

- A well-informed discussion that is based on literature and sources relevant to your reflection.

- An understanding of the complex nuance of situations and the tributary effects that prevent them from being simple and clear-cut.

- Ability to stand back and analyze your own decision-making process to see if there is a better solution to the problem.

- A clear understanding of h ow the experience has influenced you.

- A good understanding of the principles and theories of your subject area.

- Ability to frame a problem before implementing a solution.

These seven criteria form the principles of writing an excellent reflective essay.

Still need help with your essay? Handmade Writing is here to assist you!

What is the Purpose of Writing a Reflective Essay?

The purpose of a reflective essay is for a writer to reflect upon experience and learn from it . Reflection is a useful process that helps you make sense of things and gain valuable lessons from your experience. Reflective essay writing allows you to demonstrate that you can think critically about your own skills or practice strategies implementations to learn and improve without outside guidance.

Another purpose is to analyze the event or topic you are describing and emphasize how you’ll apply what you’ve learned.

How to Create a Reflective Essay Outline

- Analyze the task you’ve received

- Read through and understand the marking criteria

- Keep a reflective journal during the experience

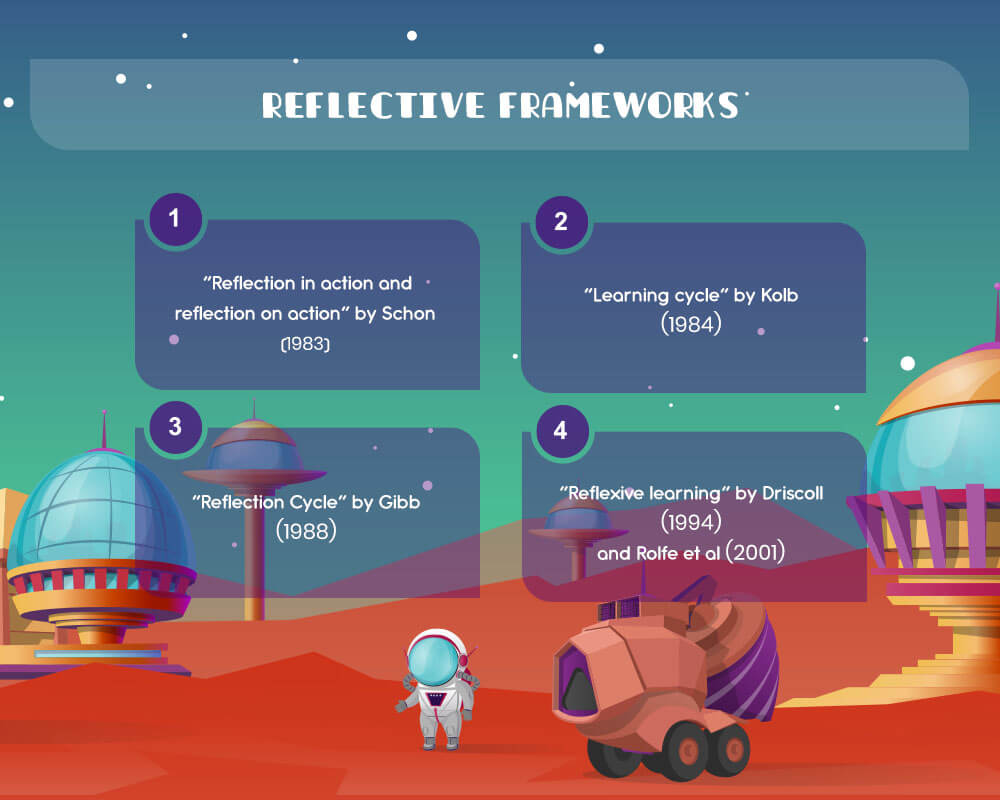

- Use a reflective framework (Schon, Driscoll, Gibbs, and Kolb) to help you analyze the experience

- Create a referencing system to keep institutions and people anonymous to avoid breaking their confidentiality

- Set the scene by using the five W’s (What, Where, When, Who and Why) to describe it

- Choose the events or the experiences you’re going to reflect on

- Identify the issues of the event or experience you want to focus on

- Use literature and documents to help you discuss these issues in a wider context

- Reflect on how these issues changed your position regarding the issue

- Compare and contrast theory with practice

- Identify and discuss your learning needs both professionally and personally

Don’t forget to adjust the formatting of your essay. There are four main format styles of any academic piece. Discover all of them from our essay format guide!

Related Posts: Essay outline | Essay format Guide

Using Reflective Frameworks

A good way to develop a reflective essay plan is by using a framework that exists. A framework will let help you break the experience down logical and make the answer easier to organize. Popular frameworks include: Schon’s (1983) Reflection in action and reflection on action .

Schon wrote ‘The Reflective Practitioner’ in 1983 in which he describes reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action as tools for learning how to meet challenges that do not conform to formulas learned in school through improvisation. He mentioned two types of reflection : one during and one after. By being aware of these processes while on a work-experience trail or clinical assignment you have to write a reflective account for, you get to understand the process better. So good questions to ask in a reflective journal could be:

<td “200”>Reflection-pre-action <td “200”>Reflection-in-action <td “200”>Reflection-on-Action<td “200”>What might happen? <td “200”>What is happening in the situation? <td “200”>What were your insights after?<td “200”>What possible challenges will you face? <td “200”>Is it working out as you expected? <td “200”>How did it go in retrospect?<td “200”>How will you prepare for the situation? <td “200”>What are the challenges you are dealing with? <td “200”>What did you value and why?<td “200”> <td “200”>What can you do to make the experience a successful one? <td “200”>What would you do differently before or during a similar situation?<td “200”> <td “200”>What are you learning? <td “200”>What have you learned?

This will give you a good frame for your paper and help you analyze your experience.

Kolb’s (1984) Learning Cycle

Kolb’s reflective framework works in four stages:

- Concrete experience. This is an event or experience

- Reflective observation. This is reflecting upon the experience. What you did and why.

- Abstract conceptualization. This is the process of drawing conclusions from the experience. Did it confirm a theory or falsify something? And if so, what can you conclude from that?

- Active experimentation. Planning and trying out the thing you have learned from this interaction.

Gibb’s (1988) Reflection Cycle

Gibbs model is an extension of Kolb’s. Gibb’s reflection cycle is a popular model used in reflective writing. There are six stages in the cycle.

- Description. What happened? Describe the experience you are reflecting on and who is involved.

- Feelings. What were you thinking and feeling at the time? What were your thoughts and feelings afterward?

- Evaluation. What was good and bad about the experience? How did you react to the situation? How did other people react? Was the situation resolved? Why and how was it resolved or why wasn’t it resolved? Could the resolution have been better?

- Analysis. What sense can you make of the situation? What helped or hindered during the event? How does this compare to the literature on the subject?

- Conclusion. What else could you have done? What have you learned from the experience? Could you have responded differently? How would improve or repeat success? How can you avoid failure?

- Action plan. If it arose again what would you do? How can you better prepare yourself for next time?

Driscoll’s Method (1994) and Rolfe et al (2001) Reflexive Learning

The Driscoll Method break the process down into three questions. What (Description), So What (Analysis) and Now What (Proposed action). Rolf et al 2001 extended the model further by giving more in-depth and reflexive questions.

- What is the problem/ difficulty/reason for being stuck/reason for feeling bad?

- What was my role in the situation?

- What was I trying to achieve?

- What actions did I take?

- What was the response of others?

- What were the consequences for the patient / for myself / for others?

- What feeling did it evoke in the patient / in myself / in others?

- What was good and bad about the experience?

- So, what were your feelings at the time?

- So, what are your feelings now? Are there any differences? Why?

- So, what were the effects of what you did or did not do?

- So, what good emerged from the situation for yourself and others? Does anything trouble you about the experience or event?

- So, what were your experiences like in comparison to colleagues, patients, visitors, and others?

- So, what are the main reasons for feeling differently from your colleagues?

- Now, what are the implications for you, your colleagues and the patients?

- Now, what needs to happen to alter the situation?

- Now, what are you going to do about the situation?

- Now, what happens if you decide not to alter anything?

- Now, what will you do differently if faced with a similar situation?

- Now, what information would you need to deal with the situation again?

- Now, what methods would you use to go about getting that information?

This model is mostly used for clinical experiences in degrees related to medicine such as nursing or genetic counseling. It helps to get students comfortable thinking over each experience and adapting to situations.

This is just a selection of basic models of this type of writing. And there are more in-depth models out there if you’re writing a very advanced reflective essay. These models are good for beginner level essays. Each model has its strengths and weaknesses. So, it is best to use one that allows you to answer the set question fully.

This written piece can follow many different structures depending on the subject area . So, check your assignment to make sure you don’t have a specifically assigned structural breakdown. For example, an essay that follows Gibbs plan directly with six labeled paragraphs is typical in nursing assignments. A more typical piece will follow a standard structure of an introduction, main body, and conclusion. Now, let’s look into details on how to craft each of these essay parts.

How to Write an Introduction?

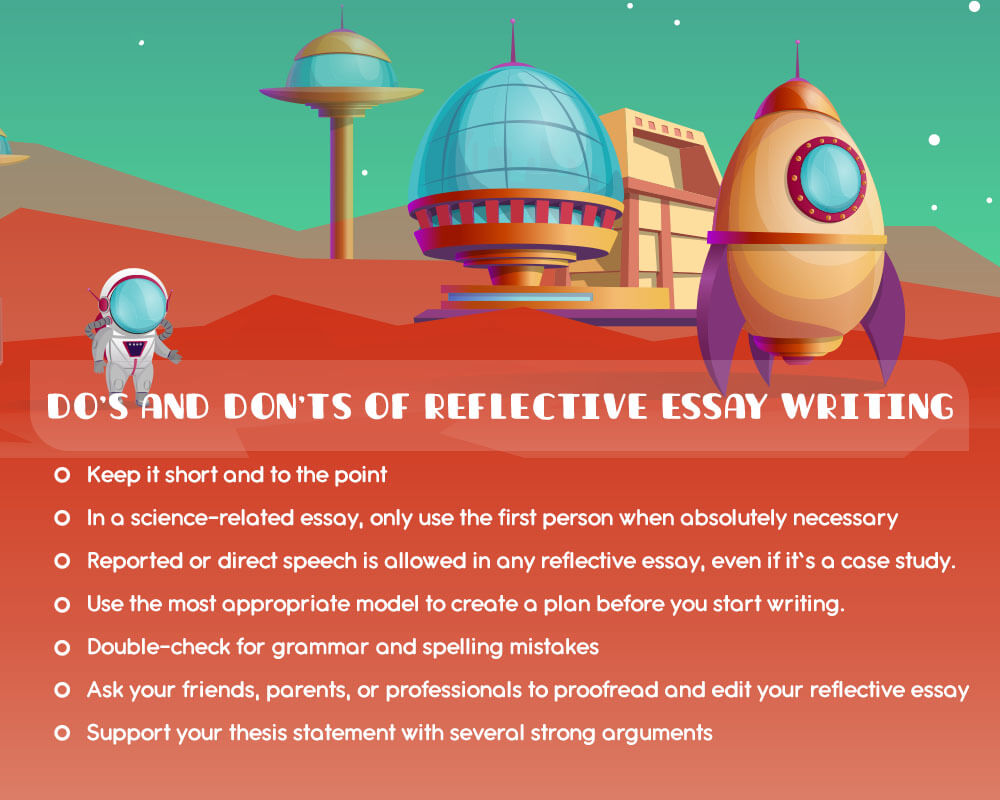

There are several good ways to start a reflective essay . Remember that an introduction to a reflective essay differs depending on upon what kind of reflection is involved. A science-based introduction should be brief and direct introducing the issue you plan on discussing and its context.

Related post: How to write an Essay Introduction

For example, a nursing student might want to discuss the overreliance on medical journals in the industry and why peer-reviewed journals led to mistaken information. In this case, one good way how to start a reflective essay introduction is by introducing a thesis statement. Help the reader see the real value of your work.

Do you need help with your thesis statement? Take a look at our recent guide explaining what is a thesis statement .

Let’s look at some reflective essay examples.

‘During my first month working at Hospital X, I became aware just how many doctors treated peer-views journal articles as a gospel act. This is a dangerous practice that because of (a), (b) and (c) could impact patients negatively.’

The reflective essay on English class would begin differently. In fact, it should be more personal and sound less bookish .

How to Write the Main Body Paragraphs?

The main body of the essay should focus on specific examples of the issue in question. A short description should be used for the opener. Each paragraph of this piece should begin with an argument supporting the thesis statement.

The most part of each paragraph should be a reflexive analysis of the situation and evaluation . Each paragraph should end with a concluding sentence that caps the argument. In a science-based essay, it is important to use theories, other studies from journals and source-based material to argue and support your position in an objective manner.

How to Write the Conclusion?

A conclusion should provide a summary of the issues explored, remind the reader of the purpose of the essay and suggest an appropriate course of action in relation to the needs identified in the body of the essay.

This is mostly an action plan for the future. However, if appropriate a writer can call readers to action or ask questions. Make sure that the conclusion is powerful enough for readers to remember it. In most cases, an introduction and a conclusion is the only thing your audience will remember.

Reflective Essay Topics

Here are some good topics for a reflective essay. We’ve decided to categorize them to help you find good titles for reflective essays that fit your requirement.

Medicine-related topics:

- Write a reflective essay on leadership in nursing

- How did a disease of your loved ones (or your own) change you?

- Write a reflection essay on infection control

- How dealing with peer-reviewed journals interrupts medical procedures?

- Write a reflection essay about community service

- Write a reflective essay on leadership and management in nursing

Topics on teamwork:

- Write a reflective essay on the group presentation

- What makes you a good team player and what stays in the way of improvement?

- Write a reflective essay on the presentation

- Write about the last lesson you learned from working in a team

- A reflective essay on career development: How teamwork can help you succeed in your career?

Topics on personal experiences:

- Write a reflective essay on the pursuit of happiness: what it means to you and how you’re pursuing it?

- Write a reflective essay on human sexuality: it is overrated today? And are you a victim of stereotypes in this area?

- Write a reflective essay on growing up

- Reflective essay on death: How did losing a loved one change your world?

- Write a reflective essay about a choice you regret

- Write a reflective essay on the counseling session

Academic topics:

- A reflective essay on the writing process: How does writing help you process your emotions and learn from experiences?

- Write a reflective essay on language learning: How learning a new language changes your worldview

- A reflective essay about a choice I regret

Related Posts: Research Paper topics | Compare&Contrast Essay topics

Reflective Essay Example

Tips on writing a good reflective essay.

Some good general tips include the following:

As long as you use tips by HandMade Writing, you’ll end up having a great piece. Just stick to our recommendations. And should you need the help of a pro essay writer service, remember that we’re here to help!

A life lesson in Romeo and Juliet taught by death

Due to human nature, we draw conclusions only when life gives us a lesson since the experience of others is not so effective and powerful. Therefore, when analyzing and sorting out common problems we face, we may trace a parallel with well-known book characters or real historical figures. Moreover, we often compare our situations with […]

Ethical Research Paper Topics

Writing a research paper on ethics is not an easy task, especially if you do not possess excellent writing skills and do not like to contemplate controversial questions. But an ethics course is obligatory in all higher education institutions, and students have to look for a way out and be creative. When you find an […]

Art Research Paper Topics

Students obtaining degrees in fine art and art & design programs most commonly need to write a paper on art topics. However, this subject is becoming more popular in educational institutions for expanding students’ horizons. Thus, both groups of receivers of education: those who are into arts and those who only get acquainted with art […]

To grade or not to grade: assessing written reflection

Just over a year ago, while I was a fourth year medical student (SL), I was required to write a reflective essay entitled, “When a patient became a person.” This piece of work contrasted starkly with the “scientific,” evidence-based approach that I had grown accustomed to. I relished this opportunity to think holistically about a patient encounter. Committing my thoughts to paper allowed me to revisit clinical experiences, and to reflect on my personal and professional progress. I have found reflection particularly useful in patient encounters that are challenging or emotionally loaded. Reflecting on these situations has enabled me to learn from good practice I have observed and to be better equipped to communicate with and support patients. The Medical Schools Council and the General Medical Council recently released guidance on reflection specifically for medical students , emphasising the importance of reflective practice and suggesting ways for students to develop skills as “reflective practitioners”, both independently and through medical school assignments. [1]

At UCL Medical School (UCLMS) reflective writing forms part of the formative medical student portfolio. Students in their first clinical year submit two 1000-word reflective pieces as part of the clinical and professional practice (CPP) curriculum. This reflective work is marked and graded by trained tutors. Grading of our reflective essays has always stirred significant debate among my peers. There is also discussion about the emphasis on written work as the mainstay of reflection.

Much has been written on reflection , including by medical students and junior doctors . [2,3] As a medical student representative, I wanted to investigate my peers’ opinions regarding our reflective writing assignments. I therefore compiled an anonymous, voluntary questionnaire, which I and other student representatives distributed to students who had completed these assignments. Students were asked to rate their views on reflective writing, its grading and to suggest possible changes.

Through this questionnaire I learned that views on reflective writing were polarised. Many students valued reflective writing, acknowledging reflection to be a key skill in becoming a doctor. Many of my peers also appreciated grading of reflective work and found it gratifying to receive a high grade for their assignments. Bespoke feedback from tutors was largely well received and deemed to be valuable. I personally found receiving tailored support and guidance from a senior on subjects that can be sensitive or difficult to communicate to be a real strength of the curriculum.

However, many of us also feel that reflection is personal, subjective and does not lend itself to grading. Receiving a low grade can be demoralising and can imply that the student has reflected “incorrectly,” which many students find inappropriate. I can also see how fulfilling specific grading criteria may encourage contrived writing at the expense of genuine reflection.

When students were asked to comment on possible changes to reflective writing, some suggested greater standardisation of marking and feedback, while others proposed removing set titles or the grading system altogether. Some expressed anxiety about the confidentiality of written reflection in the wake of the Bawa-Garba case , in which the contents of a junior doctor’s reflective portfolio may have “fed into” court proceedings. [4] There were also comments about alternative methods for reflection, with many preferring face to face or verbal reflection.

Some students like myself, had participated in Balint groups or Schwartz Rounds, both of which are confidential formats for group discussion and reflection around clinical experiences . [5,6] Poetry, music and art were also suggested as formats for reflection. These are all important creative outlets, but may not be practical for medical school reflective practice. In addition, they may not provide the same function or the same benefits as written reflection. Reflective writing requires deliberate, considered thought around an experience, to allow for learning and potential changes to future practice; other media for reflection may not deliver this.

When I reported these findings to faculty (FG, JY), it resulted in a change to the reflective curriculum. A more detailed online guide to reflective writing for students has been introduced outlining the purpose of reflective practice, relevance to our future careers, different reflective opportunities available within our curriculum and useful models for reflection. In addition, welcome tips on composing the assignment have been provided. Additional essay titles, some suggested by the student body, have been included to widen the choices available. It was gratifying to see these changes implemented.

As someone who has participated in reflective practice at every opportunity during my undergraduate career, being able to co-create and contribute to the reflective curriculum has been invaluable. I appreciate the difficulties in incorporating reflective, unexamined aspects into a full medical education, and feel fortunate to be part of a medical school which can be responsive to the needs of its students.

Jenan Younis is a Colorectal Surgeon and Clinical Teaching Fellow at UCL Medical School Competing interests: None declared

Faye Gishen is a consultant physician and the associate head of the MBBS at UCL Medical School. Competing interests: None declared

References:

- General Medical Council. The reflective practitioner – a guide for medical students. 2019. https://www.gmc-uk.org/education/standards-guidance-and-curricula/guidance/reflective-practice/the-reflective-practitioner—a-guide-for-medical-students (accessed 3 September 2019)

- Macaulay CP, Winyard PJW. Reflection: tick box exercise or learning for all?. BMJ. 2012;345:e7468.

- Furmedge D. Written Reflection is Dead in the Water. BMJ . 2016;353:i3250.

- Dyer C, Cohen D. How should doctors use e-portfolios in the wake of the Bawa-Garba case? BMJ . 2018;360:k572.

- Roberts M. Balint groups: A tool for personal and professional resilience. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58(3):245-7.

- Gishen F, Whitman S, Gill D, Barker R, Walker S. Schwartz Centre Rounds: a new initiative in the undergraduate curriculum—what do medical students think?. BMC Med Educ. 2016, 16:246 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0762-6

Information for Authors

BMJ Opinion provides comment and opinion written by The BMJ's international community of readers, authors, and editors.

We welcome submissions for consideration. Your article should be clear, compelling, and appeal to our international readership of doctors and other health professionals. The best pieces make a single topical point. They are well argued with new insights.

For more information on how to submit, please see our instructions for authors.

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

Reflective writing

- Related content

- Peer review

- Helen C Richardson , consultant in ENT and senior clinical lecturer

- James Cook University Hospital, Middlesbrough Helen.Richardson{at}stees.nhs.uk

Increasingly, at all stages of medical education, we are asked to keep a learning portfolio, which usually includes some reflective writing. While those fresh from medical school will be familiar with this learning tool, it may be unfamiliar and difficult for others.

Reflective writing is said to encourage a writer to learn from an event, as it necessitates focused and analytical thinking. The lessons learnt can be identified and recorded, as can learning needs for future attention.

Description

Use the word “I” frequently.

Start with a description of an event. Be as objective and detailed as you can. Avoid judgments or interpretations.

Perceptions

Be clear that you have moved from description to interpretation. Make this difference explicit for readers (whether for yourself at a later date, a tutor, or an educational supervisor).

Describe the way you perceived the event. Why do you think things happened the way they did? Don't assume something was inevitable after what has happened previously.

Feelings and emotions

This is the most difficult step for many, but is a valuable source of self learning. Be as honest as you can about the emotions and feelings that the event triggered. What in particular precipitated the emotions you describe?

Avoid assuming that your response is just the way anyone would react. Consider possible alternatives—are there patterns in your emotional response to events?

It can help to try to see things from others' viewpoints.

Your own role

Why did you act as you did? • How else could you have acted?

Which parts went well or badly? Why? • What have you learnt? • What will you do differently next time? • What learning needs have you identified? ■

- Open access

- Published: 09 January 2023

A systematic scoping review of reflective writing in medical education

- Jia Yin Lim 1 , 2 ,

- Simon Yew Kuang Ong 3 , 4 , 5 ,

- Chester Yan Hao Ng 1 , 2 ,

- Karis Li En Chan 1 , 2 ,

- Song Yi Elizabeth Anne Wu 1 , 2 ,

- Wei Zheng So 1 , 2 ,

- Glenn Jin Chong Tey 1 , 2 ,

- Yun Xiu Lam 1 , 2 ,

- Nicholas Lu Xin Gao 1 , 2 ,

- Yun Xue Lim 1 , 2 ,

- Ryan Yong Kiat Tay 1 , 2 ,

- Ian Tze Yong Leong 1 , 2 ,

- Nur Diana Abdul Rahman 4 ,

- Min Chiam 4 ,

- Crystal Lim 6 ,

- Gillian Li Gek Phua 2 , 5 , 7 ,

- Vengadasalam Murugam 2 , 5 ,

- Eng Koon Ong 2 , 4 , 5 , 8 &

- Lalit Kumar Radha Krishna 1 , 2 , 4 , 5 , 9 , 10

BMC Medical Education volume 23 , Article number: 12 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

6749 Accesses

19 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Reflective writing (RW) allows physicians to step back, review their thoughts, goals and actions and recognise how their perspectives, motives and emotions impact their conduct. RW also helps physicians consolidate their learning and boosts their professional and personal development. In the absence of a consistent approach and amidst growing threats to RW’s place in medical training, a review of theories of RW in medical education and a review to map regnant practices, programs and assessment methods are proposed.

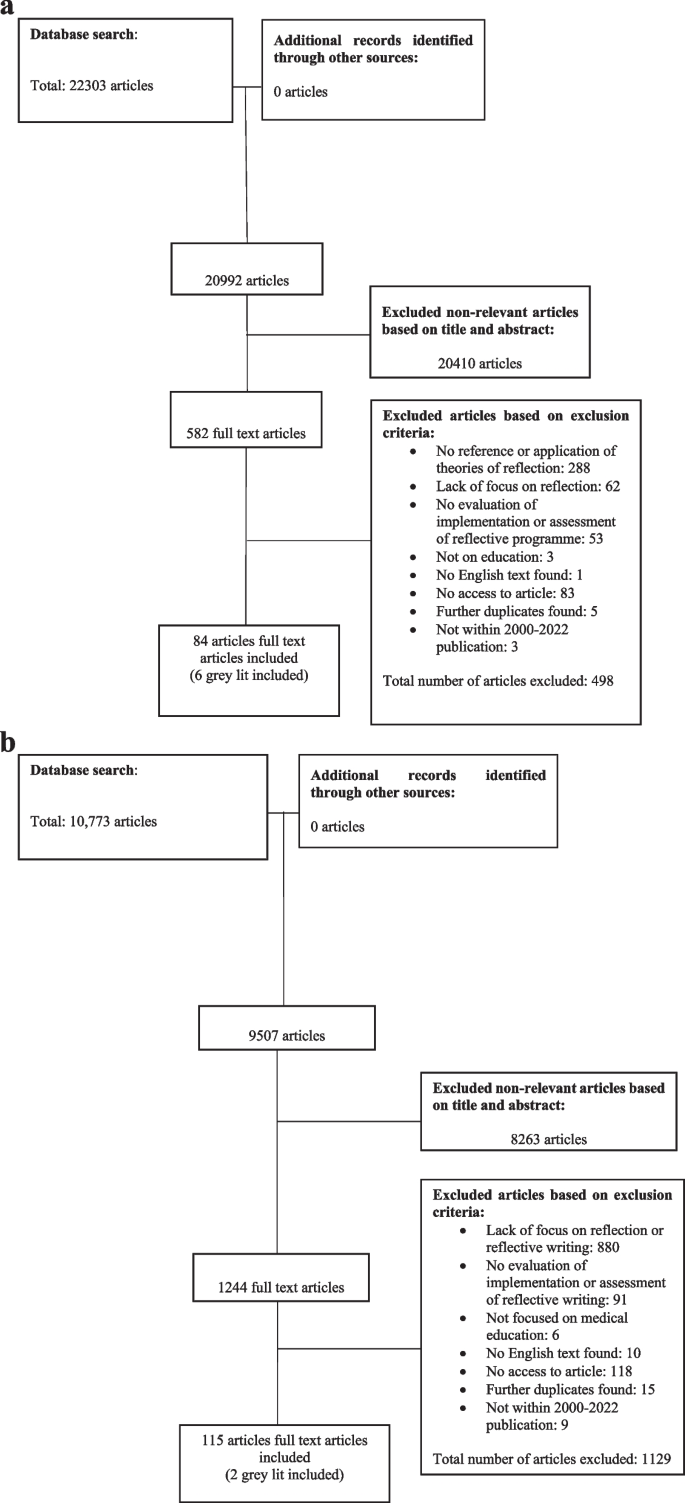

A Systematic Evidence-Based Approach guided Systematic Scoping Review (SSR in SEBA) was adopted to guide and structure the two concurrent reviews. Independent searches were carried out on publications featured between 1st January 2000 and 30th June 2022 in PubMed, Embase, PsychINFO, CINAHL, ERIC, ASSIA, Scopus, Google Scholar, OpenGrey, GreyLit and ProQuest. The Split Approach saw the included articles analysed separately using thematic and content analysis. Like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, the Jigsaw Perspective combined the themes and categories identified from both reviews. The Funnelling Process saw the themes/categories created compared with the tabulated summaries. The final domains which emerged structured the discussion that followed.

A total of 33,076 abstracts were reviewed, 1826 full-text articles were appraised and 199 articles were included and analysed. The domains identified were theories and models, current methods, benefits and shortcomings, and recommendations.

Conclusions

This SSR in SEBA suggests that a structured approach to RW shapes the physician’s belief system, guides their practice and nurtures their professional identity formation. In advancing a theoretical concept of RW, this SSR in SEBA proffers new insight into the process of RW, and the need for longitudinal, personalised feedback and support.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Reflective practice in medicine allows physicians to step back, review their actions and recognise how their thoughts, feelings and emotions affect their decision-making, clinical reasoning and professionalism [ 1 ]. This approach builds on Dewey [ 2 ], Schon [ 3 , 4 ], Kolb [ 5 ], Boud et al. [ 6 ] and Mezirow [ 7 ]’s concepts of critical self-examination. It sees new insights drawn from the physician’s experiences and considers how assumptions may integrate into their current values, beliefs and principles (henceforth belief system) [ 8 , 9 ].

Teo et al. [ 10 ] build on this concept of reflective practice. The authors suggest that the physician’s belief system informs and is informed by their self-concepts of identity which are in turn rooted in their self-concepts of personhood - how they conceive what makes them who they are [ 11 ]. This posit not only ties reflective practice to the shaping of the physician’s moral and ethical compass but also offers evidence of it's role in their professional identity formation (PIF) [ 8 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ]. With PIF [ 8 , 24 ] occupying a central role in medical education, these ties underscore the critical importance placed on integrating reflective practice in medical training.

Perhaps the most common form of reflective practice in medical education is reflective writing (RW) [ 25 ]. Identified as one of the distinct approaches used to achieve integrated learning, education, curriculum and teaching [ 26 ], RW already occupies a central role in guiding and supporting longitudinal professional development [ 27 , 28 , 29 ]. Its ability to enhance self-monitoring and self-regulation of decisional paradigms and conduct has earned RW a key role in competency-based medical practice and continuing professional development [ 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 ].

However, the absence of consistent guiding principles, dissonant practices, variable structuring and inadequate assessments have raised concerns as to RW’s efficacy and place in medical training [ 25 , 37 , 38 , 39 ]. A Systematic Scoping Review is proposed to map current understanding of RW programs. It is hoped that this SSR will also identify gaps in knowledge and regnant practices, programs and assessment methods to guide the design of RW programs.

Methodology

A Systematic Scoping Review (SSR) is employed to map the employ, structuring and assessment of RW in medical education. An SSR-based review is especially useful in attending to qualitative data that does not lend itself to statistical pooling [ 40 , 41 , 42 ] whilst its broad flexible approach allows the identification of patterns, relationships and disagreements [ 43 ] across a wide range of study formats and settings [ 44 , 45 ].

To synthesise a coherent narrative from the multiple accounts of reflective writing, we adopt Krishna’s Systematic Evidence-Based Approach (SEBA) [ 10 , 15 , 21 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 ]. A SEBA-guided Systematic Scoping Review (SSR in SEBA) [ 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 50 , 53 , 54 , 55 ] facilitates reproducible, accountable and transparent analysis of patterns, relationships and disagreements from multiple angles [ 56 ].

The SEBA process (Fig. 1 ) comprises the following elements: 1) Systematic Approach, 2) Split Approach, 3) Jigsaw Perspective, 4) Funnelling Process, 5) Analysis of data and non-data driven literature, and 6) Synthesis of SSR in SEBA [ 10 , 15 , 21 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 ] . Every stage was overseen by a team of experts that included medical librarians from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (YLLSoM) at the National University of Singapore, and local educational experts and clinicians at YLLSoM, Duke-NUS Medical School, Assisi Hospice, Singapore General Hospital, National Cancer Centre Singapore and Palliative Care Institute Liverpool.

The SEBA Process

STAGE 1 of SEBA: Systematic Approach

Determining the title and background of the review.

Ensuring a systematic approach, the expert team and the research team agreed upon the overall goals of the review. Two separate searches were performed, one to look at the theories of reflection in medical education, and another to review regnant practices, programs, and assessment methods used in reflective writing in medical education. The PICOs is featured in Table 1 .

Identifying the research question

Guided by the Population Concept, Context (PCC) elements of the inclusion criteria and through discussions with the expert team, the research question was determined to be: “ How is reflective writing structured, assessed and supported in medical education? ” The secondary research question was “ How might a reflective writing program in medical education be structured? ”

Inclusion criteria

All study designs including grey literature published between 1st January 2000 to 30th June 2022 were included [ 61 , 62 ]. We also consider data on medical students and physicians from all levels of training (henceforth broadly termed as physicians).

Ten members of the research team carried out independent searches using seven bibliographic databases (PubMed, Embase, PsychINFO, CINAHL, ERIC, ASSIA, Scopus) and four grey literature databases (Google Scholar, OpenGrey, GreyLit, ProQuest). Variations of the terms “reflective writing”, “physicians and medical students”, and “medical education” were applied.

Extracting and charting

Titles and abstracts were independently reviewed by the research team to identify relevant articles that met the inclusion criteria set out in Table 1 . Full-text articles were then filtered and proposed. These lists were discussed at online reviewer meetings and Sandelowski and Barroso [ 63 ]’s approach to ‘negotiated consensual validation’ was used to achieve consensus on the final list of articles to be included.

Stage 2 of SEBA: Split Approach

The Split Approach was employed to enhance the trustworthiness of the SSR in SEBA [ 64 , 65 ]. Data from both searches were analysed by three independent groups of study team members.

The first group used Braun and Clarke [ 66 ]’s approach to thematic analysis. Phase 1 consisted of ‘actively’ reading the included articles to find meaning and patterns in the data. The analysis then moved to Phase 2 where codes were constructed. These codes were collated into a codebook and analysed using an iterative step-by-step process. As new codes emerge, previous codes and concepts were incorporated. In Phase 3, codes and subthemes were organised into themes that best represented the dataset. An inductive approach allowed themes to be “defined from the raw data without any predetermined classification” [ 67 ]. In Phase 4, these themes were then further refined to best depict the whole dataset. In Phase 5, the research team discussed the results and consensus was reached, giving rise to the final themes.

The second group employed Hsieh and Shannon [ 68 ]’s approach to directed content analysis. Categories were drawn from Mann et al. [ 9 ]’s article, “Reflection and Reflective Practice in Health Professions Education: A Systematic Review” and Wald and Reis [ 69 ]’s article “Beyond the Margins: Reflective Writing and Development of Reflective Capacity in Medical Education”.

The third group created tabulated summaries in keeping with recommendations drawn from Wong et al. [ 56 ]’s "RAMESES Publication Standards: Meta-narrative Reviews" and Popay et al. [ 70 ]’s “Guidance on the C onduct of N arrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews”. The tabulated summaries served to ensure that key aspects of included articles were not lost.

Stage 3 of SEBA: Jigsaw Perspective

The Jigsaw Perspective [ 71 , 72 ] saw the findings of both searches combined. Here, overlaps and similarities between the themes and categories from the two searches were combined to create themes/categories. The themes and subthemes were compared with the categories and subcategories identified, and similarities were verified by comparing the codes contained within them. Individual subthemes and subcategories were combined if they were complementary in nature.

Stage 4 of SEBA: Funnelling Process

The Funnelling Process saw the themes/categories compared with the tabulated summaries to determine the consistency of the domains created, forming the basis of the discussion.

Stage 5: Analysis of data and non-data driven literature

Amidst concerns that data from grey literature which were neither peer-reviewed nor necessarily evidence-based may bias the synthesis of the discussion, the research team separately thematically analysed the included grey literature. These themes were compared with themes from data-driven or research-based peer-reviewed data and were found to be the same and thus unlikely to have influenced the analysis.

Stage 6: Synthesis of SSR in SEBA

The Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) Collaboration Guide and the Structured approach to the Reporting In healthcare education of Evidence Synthesis (STORIES) were used to guide the discussion.

A total of 33,076 abstracts were reviewed from the two separate searches on theories of reflection in medical education, and on regnant practices, programs and assessments of RW programs in medical education. A total of 1826 full-text articles were appraised from the separate searches, and 199 articles were included and analysed. The PRISMA Flow Chart may be found in Fig. 2 a and b. The domains identified when combining the findings of the two separate searches were 1) Theories and Models, 2) Current Methods, 3) Benefits and Shortcomings and 4) Recommendations.

a PRISMA Flow Chart (Search Strat #1: Theories of Reflection in Medical Education). b PRISMA Flow Chart (Search Strat #2: Reflective Writing in Medical Education)

Domain 1: Theories and Models

Many current theories and models surrounding RW in medical education are inspired by Kolb’s Learning Cycle [ 5 ] (Table 2 ). These theories focus on descriptions of areas of reflection; evaluations of experiences and emotions; how events may be related to previous experiences; knowledge critiques of their impact on thinking and practice; integration of learning points; and the physician’s willingness to apply lessons learnt [ 6 , 73 , 74 , 75 ]. In addition, some of these theories also consider the physician’s self-awareness, ability and willingness to reflect [ 76 ], contextual factors related to the area of reflection [ 4 , 77 ] and the opportunity to reflect effectively within a supportive environment [ 78 , 79 ]. Ash and Clayton's DEAL Model recommends inclusion of information from all five senses [ 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 ]. Johns's Model of Structured Reflection [ 84 ] advocates giving due consideration to internal and external influences upon the event being evaluated. Rodgers [ 39 ] underlines the need for appraisal of the suppositions and assumptions that precipitate and accompany the effects and responses that may have followed the studied event. Griffiths and Tann [ 75 ], Mezirow [ 77 ], Kim [ 85 ], Roskos et al. [ 86 ], Burnham et al. [ 87 ], Korthagen and Vasalos [ 78 ] and Koole et al. [ 74 ] build on Dewey [ 2 ] and Kolb [ 5 ]’s notion of creating and experimenting with a ‘working hypothesis’. These models also propose that the lessons learnt from experimentations should be critiqued as part of a reiterative process within the reflective cycle. Underlining the notion of the reflective cycle and the long-term effects of RW, Pearson and Smith [ 88 ] suggest that reflections should be carried out regularly to encourage longitudinal and holistic reflections on all aspects of the physician’s personal and professional life.

Regnant theories shape assessments of RW (Table 3 ). This extends beyond Thorpe [ 96 ]’s study which categorises reflective efforts into ‘non-reflectors’, ‘reflectors’, ‘critical reflectors’, and focuses on their process, structure, depth and content. van Manen [ 97 ], Plack et al. [ 98 ], Rogers et al. [ 99 ] and Makarem et al. [ 100 ] begin with evaluating the details of the events. Kim’s Critical Reflective Inquiry Model [ 85 ] and Bain’s 5Rs Reflective Framework [ 101 ] also consider characterisations of emotions involved. Other models appraise the intentions behind actions and thoughts [ 85 ], the factors precipitating the event [ 101 ] and meaning-making [ 85 ]. Other theories consider links with previous experiences [ 100 ], the integration of thoughts, justifications and perspectives [ 99 ], and the hypothesising of future strategies [ 98 ].

Domain 2: Current methods of structuring RW programs

Current programs focus on supporting the physician throughout the reflective process. Whilst due consideration is given to the physician’s motivations, insight, experiences, capacity and capabilities [ 25 , 96 , 112 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 ], programs also endeavour to ensure appropriate selection and training of physicians intending to participate in RW. Efforts are also made to align expectations, and guide and structure the RW process [ 37 , 116 , 117 , 118 , 119 , 120 , 121 , 122 ]. Physicians are provided with frameworks [ 76 , 79 , 105 , 123 , 124 ], rubrics [ 99 , 123 , 125 , 126 ], examples of the expected quality and form of reflection [ 96 , 115 , 116 ], and how to include emotional and contextual information in their responses [ 121 , 127 , 128 , 129 ].

Other considerations are enclosed in Table 4 including frequency, modality and the manner in which RW is assessed.

Domain 3: Benefits and Shortcomings

The benefits of RW are rarely described in detail and may be divided into personal and professional benefits as summarised in Table 5 for ease of review. From a professional perspective, RW improves learning [ 96 , 112 , 119 , 147 , 157 , 170 , 179 , 185 , 186 , 187 , 188 , 189 , 190 , 191 , 192 ], facilitates continuing medical education [ 119 , 128 , 173 , 174 , 193 , 194 , 195 ], inculcates moral, ethical, professional and social standards and expectations [ 118 , 156 , 160 ], improves patient care [ 29 , 120 , 129 , 131 , 135 , 142 , 194 , 196 , 197 , 198 , 199 ] and nurtures PIF [ 150 , 157 , 172 , 191 , 200 ].

From a personal perspective, RW increases self-awareness [ 114 , 127 , 137 , 161 , 166 , 179 , 185 , 202 , 216 ], self-advancement [ 9 , 131 , 134 , 150 , 168 , 174 , 195 , 205 , 217 , 229 ], facilitates understanding of individual strengths, weaknesses and learning needs [ 112 , 119 , 150 , 152 , 170 , 218 , 219 ], promotes a culture of self-monitoring, self-improvement [ 130 , 172 , 173 , 185 , 193 , 198 , 201 , 210 , 211 ], developing critical perspectives of self [ 193 , 223 ] and nurtures resilience and better coping [ 154 , 160 , 206 ]. RW also guides shifts in thinking and perspectives [ 148 , 149 , 156 , 203 , 207 , 208 ] and focuses on a more holistic appreciation of decision-making [ 37 , 118 , 126 , 174 , 177 , 194 , 196 , 199 , 200 , 224 , 225 , 226 ] and their ramifications [ 37 , 112 , 116 , 130 , 131 , 141 , 154 , 179 , 193 , 194 , 196 , 204 , 207 , 218 , 230 ].

Table 6 combines current lists of the shortcomings of RW. These limitations may be characterised by individual, structural and assessment styles.

It is suggested that RW does not cater to the different learning styles [ 220 , 232 ], cultures [ 190 ], roles, values, processes and expectations of RW [ 114 , 129 , 135 , 138 , 142 , 209 , 227 , 234 ], and physicians' differing levels of self-awareness [ 29 , 79 , 119 , 176 , 188 , 226 , 231 , 236 ], motivations [ 29 , 119 , 136 , 138 , 157 , 161 , 167 , 168 , 169 , 176 , 181 , 193 , 196 , 226 , 232 , 233 ] and willingness to engage in RW [ 37 , 114 , 136 , 149 , 160 , 183 ]. RW is also limited by poorly prepared physicians and misaligned expectations whilst a lack of privacy and a safe setting may precipitate physician anxiety at having their private thoughts shared [ 129 , 149 , 209 , 231 ]. RW is also compromised by a lack of faculty training [ 143 , 145 , 239 ], mentoring support [ 37 , 50 , 119 , 133 , 196 ] and personalised feedback [ 50 , 114 , 136 , 167 , 229 ] which may lead to self-censorship [ 37 , 114 , 136 , 149 , 160 , 183 ] and an unwillingness to address negative emotions arising from reflecting on difficult events [ 114 , 168 , 176 , 193 , 230 ], circumventing the reflective process [ 118 , 142 , 165 , 196 ] .

Variations in assessment styles [ 9 , 115 , 157 , 161 , 166 , 193 , 209 ], depth [ 29 , 105 , 118 , 126 , 177 , 207 ] and content [ 37 , 114 , 136 , 149 , 169 , 183 , 196 ], and pressures to comply with graded assessments [ 114 , 115 , 118 , 129 , 138 , 143 , 149 , 155 , 157 , 209 , 232 , 237 , 238 ] also undermine efforts of RW.

Domain 4. Recommendations

In the face of practice variations and challenges, there have been several recommendations on improving practice.

Boosting awareness of RW

Acknowledging the importance of a physician’s motivations, willingness and judgement [ 37 ], an RW program must acquaint physicians with information on RW’s role [ 128 ], program expectations, the form, frequency and assessments of RW and the support available to them [ 130 , 132 , 150 , 154 , 242 ] and its benefits to their professional and personal development [ 96 , 227 ] early in their training programs [ 115 , 220 , 242 , 243 ]. Physicians should also be trained on the knowledge and skills required to meet these expectations [ 1 , 37 , 135 , 151 , 160 , 215 , 244 , 245 ].

A structured program and environment

Recognising that effective RW requires a structured program. Recommendations focus on three aspects of the program design [ 132 ]. One is the need for trained faculty [ 9 , 115 , 219 , 220 , 230 , 233 , 242 , 246 ], accessible communications, protected time for RW and debriefs [ 125 ], consistent mentoring support [ 190 ] and assessment processes [ 247 ]. This will facilitate trusting relationships between physicians and faculty [ 30 , 114 , 168 , 196 , 231 , 233 ]. Two, the need to nurture an open and trusting environment where physicians will be comfortable with sharing their reflections [ 96 , 128 ], discussing their emotions, plans [ 127 , 248 ] and receiving feedback [ 9 , 37 , 79 , 114 , 119 , 128 , 135 , 173 , 176 , 179 , 190 , 237 ]. This may be possible in a decentralised classroom setting [ 163 , 190 ]. Three, RW should be part of the formal curriculum and afforded designated time. RW should be initiated early and longitudinally along the training trajectory [ 116 , 122 ].

Adjuncts to RW programs

Several approaches have been suggested to support RW programs. These include collaborative reflection, in-person discussion groups to share written reflections [ 128 , 131 , 138 , 196 , 199 , 231 , 249 ] and reflective dialogue to exchange feedback [ 119 ], use of social media [ 149 , 160 , 169 , 194 , 204 , 230 ], video-recorded observations and interactions for users to review and reflect on later [ 133 ]. Others include autobiographical reflective avenues in addition to practice-oriented reflection [ 137 ], support groups to help meditate stress or emotions triggered by reflections [ 249 ] and mixing of reflective approaches to meet different learning styles [ 169 , 250 ].

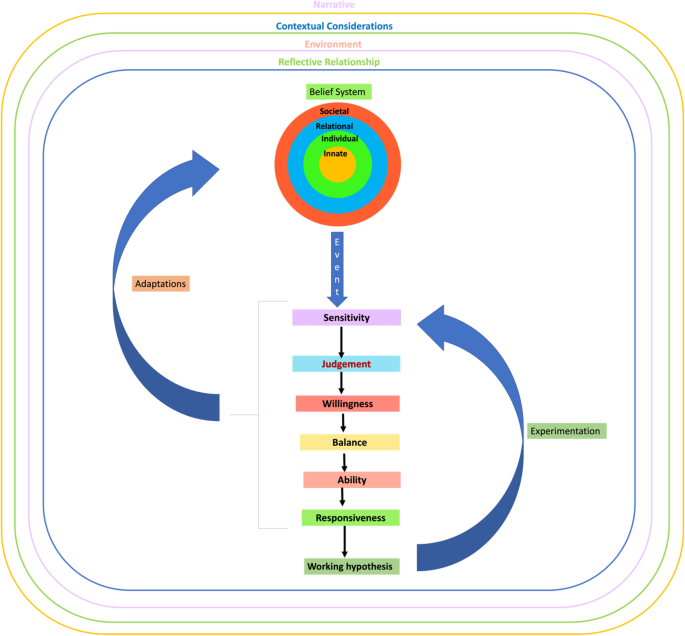

In answering the primary research question, “How is reflective writing structured, assessed and supported in medical education?” , this SSR in SEBA highlights several key insights. To begin, RW involves integrating the insights of an experience or point of reflection (henceforth ‘event’) into the physician’s currently held values, beliefs and principles (henceforth belief system). Recognising that an ‘event’ has occurred and that it needs deeper consideration highlights the physician’s sensitivity . Recognising the presence of an ‘event’ triggers an evaluation as to the urgency in which it needs to be addressed, where it stands amongst other ‘events’ to be addressed and whether the physician has the appropriate skills, support and time to address the ‘event’. This reflects the physician’s judgement . The physician must then determine whether they are willing to proceed and the ramifications involved. These include ethical, medical, clinical, administrative, organisational, sociocultural, legal and professional considerations. This is then followed by contextualising them to their own personal, psychosocial, clinical, professional, research, academic, and situational setting. Weighing these amidst competing ‘events’ underlines the import of the physician’s ability to ‘balance’ considerations. Creating and experimenting on their ‘working hypothesis’ highlights their ‘ability’, whilst how they evaluate the effects of their experimentation and how they adapt their practice underscores their ‘ responsiveness ’ [ 2 , 5 , 74 , 75 , 77 , 78 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 90 ].

The concepts of ‘ sensitivity’, ‘judgement’, ‘willingness’, ‘balance’, ‘ability’ and ‘responsiveness’ spotlight environmental and physician-related factors. These include the physician’s motivations, knowledge, skills, attitudes, competencies, working style, needs, availabilities, timelines, and their various medical, clinical, administrative, organisational, sociocultural, legal, professional, personal, psychosocial, clinical, research, academic and situational experiences. It also underlines the role played by the physician’s beliefs, moral values, ethical principles, familial mores, cultural norms, attitudes, thoughts, decisional preferences, roles and responsibilities. The environmental-related factors include the influence of the curriculum, the culture, structure, format, assessment and feedback of the RW process and the program it is situated in. Together, the physician and their environmental factors not only frame RW as a sociocultural construct necessitating holistic review but also underscore the need for longitudinal examination of its effects. This need for holistic and longitudinal appraisal of RW is foregrounded by the experimentations surrounding the ‘working hypothesis’ [ 2 , 5 , 72 , 74 , 77 , 84 , 85 , 86 , 90 ]. In turn, experimentations and their effects affirm the notion of regular use of RW and reiterate the need for longitudinal reflective relationships that provide guidance, mentoring and feedback [ 87 , 90 ]. These considerations set the stage for the proffering of a new conceptual model of RW.

To begin, the Krishna Model of Reflective Writing (Fig. 3 ) builds on the Krishna-Pisupati Model [ 10 ] used to describe evaluations of professional identity formation (PIF) [ 8 , 10 , 24 , 251 ]. Evidenced in studies of how physicians cope with death and dying patients, moral distress and dignity-centered care [ 46 , 54 ], the Krishna-Pisupati Model suggests that the physician’s belief system is informed by their self-concepts of personhood and identity. This is effectively characterised by the Ring Theory of Personhood (RToP) [ 11 ].

Krishna Model of Reflective Writing

The Krishna Model of RW posits that the RToP is able to encapsulate various aspects of the physician’s belief system. The Innate Ring which represents the innermost ring of the four concentric rings depicting the RToP is derived from currently held spiritual, religious, theist, moral and ethical values, beliefs and principles [ 13 , 51 , 53 , 252 ]. Encapsulating the Innate Ring is the Individual Ring. The Individual Ring’s belief system is derived from the physician’s thoughts, conduct, biases, narratives, personality, decision-making processes and other facets of conscious function which together inform the physician’s Individual Identity [ 13 , 51 , 53 , 252 ]. The Relational Ring is shaped by the values, beliefs and principles governing the physician’s personal and important relationships [ 13 , 51 , 53 , 252 ]. The Societal Ring, the outermost ring of the RToP is shaped by regnant societal, religious, professional and legal expectations, values, beliefs and principles which inform their interactions with colleagues and acquaintances [ 13 , 51 , 53 , 252 ]. Adoption of the RToP to depict this belief system not only acknowledges the varied aspects and influences that shape the physician’s identity but that the belief system evolves as the physician’s environment, narrative, context and relationships change.

The environmental factors influencing the belief system include the support structures used to facilitate reflections such as appropriate protected time, a consistent format for RW, a structured assessment program, a safe environment, longitudinal support, timely feedback and trained faculty. The Krishna Model of RW also recognises the importance of the relationships which advocate for the physician and proffer the physician with coaching, role modelling, supervision, networking opportunities, teaching, tutoring, career advice, sponsorship and feedback upon the RW process. Of particular importance is the relationship between physician and faculty (henceforth reflective relationship). The reflective relationship facilitates the provision of personalised, appropriate, holistic, and frank communications and support. This allows the reflective relationship to support the physician as they deploy and experiment with their ‘working hypothesis’. As a result, the Krishna Model of RW focuses on the dyadic reflective relationship and acknowledges that there are wider influences beyond this dyad that shape the RW process. This includes the wider curriculum, clinical, organisational, social, professional and legal considerations within specific practice settings and other faculty and program-related factors. Important to note, is that when an ‘event’ triggers ‘ sensitivity’, ‘judgement’, ‘willingness’, ‘balance’, ‘ability’ and ‘responsiveness’, the process of creating and experimenting with a ‘working hypothesis' and adapting one's belief system is also shaped by the physician’s narratives, context, environment and relationships.

In answering its secondary question, “ How might a reflective writing program in medical education be structured? ”, the data suggests that an RW program ought to be designed with due focus on the various factors influencing the physician's belief system, their ‘sensitivity’, ‘judgement’, ‘willingness’, ‘balance’, ‘ability’ and ‘responsiveness’, and their creation and experimentation with their ‘working hypothesis’. These will be termed the ‘physician's reactions’ . The design of the RW program ought to consider the following factors:

Belief system

Recognising that the physician’s notion of ‘ sensitivity’, ‘judgement’, ‘willingness’, ‘balance’, ‘ability’ and ‘responsiveness’ is influenced by their experience, skills, knowledge, attitude and motivations, physicians recruited to the RW program should be carefully evaluated

To align expectations, the physician should be introduced to the benefits and role of RW in their personal and professional development

The ethos, frequency, goals and format of the reflection and assessment methods should be clearly articulated to the physician [ 253 ]

The physician should be provided with the knowledge, skills and mentoring support necessary to meet expectations [ 76 , 79 , 105 , 123 , 124 , 254 , 255 ]

Training and support must also be personalised

Contextual considerations

Recognising that the physician’s academic, personal, research, administrative, clinical, professional, sociocultural and practice context will change, the structure, approach, assessment and support provided must be flexible and responsive

The communications platform should be easily accessible and robust to attend to the individual needs of the physician in a timely and appropriate manner

The program must support diversity [ 207 ]

Environment

The reflective relationship is shaped by the culture and structure of the environment in which the program is hosted in

The RW programs must be hosted within a formal structured curriculum, supported and overseen by a host organisation which is able to integrate the program into regnant educational and assessment processes [ 9 , 115 , 219 , 220 , 230 , 233 , 242 , 246 ]

Reflective relationship

The faculty must be trained and provided access to counselling, mindfulness meditation and stress management programs [ 249 ]

The faculty must support the development of the physician’s metacognitive skills [ 256 , 257 , 258 , 259 ], and should create a platform that facilitates community-centered learning [ 173 , 176 ], structured, timely, personalised open feedback [ 119 , 135 , 179 , 237 ] and support [ 128 , 131 , 138 , 196 , 199 , 231 , 249 ]

The faculty must be responsive to changes and provide appropriate personal, educational and professional support and adaptations to the assessment process when required [ 207 ]

To facilitate the development of effective reflective relationships, a consistent faculty member should work with the physician and build a longitudinal trusting, open and supportive reflective relationship

Physician’s reactions

The evolving nature of the various structures and influences upon the RW process underscores the need for longitudinal assessment and support

The physician must be provided with timely, appropriate and personalised training and feedback

The program’s structure and oversight must also be flexible and responsive

There must be accessible longitudinal mentoring support

The format and assessment of RW must account for growing experience and competencies as well as changing motivations and priorities

Whilst social media may be employed to widen sharing [ 149 , 155 , 160 , 169 , 194 ], privacy must be maintained [ 120 , 189 ]

On assessment

Assessment rubrics should be used to guide the training of faculty, education of physicians and guidance of reflections [ 37 , 116 , 117 , 118 , 119 , 120 , 121 , 122 ]

Assessments ought to take a longitudinal perspective to track the physician's progress [ 116 , 122 ]

Based on the results from this SSR in SEBA, we forward a guide catering to novice reflective practitioners (Additional file 1 ).

Limitations

This SSR in SEBA suggests that, amidst the dearth of rigorous quantitative and qualitative studies in RW and in the presence of diverse practices, approaches and settings, conclusions may not be easily drawn. Extrapolations of findings are also hindered by evidence that appraisals of RW remain largely reliant upon single time point self-reported outcomes and satisfaction surveys.

This SSR in SEBA highlights a new model for RW that requires clinical validation. However, whilst still not clinically proven, the model sketches a picture of RW’s role in PIF and the impact of reflective processes on PIF demands further study. As we look forward to engaging in this area of study, we believe further research into the longer-term effects of RW and its potential place in portfolios to guide and assess the development of physicians must be forthcoming.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this review are included in this published article and its supplementary files.

Abbreviations

Reflective Writing

Professional Identity Formation

Ring Theory of Personhood

Best Evidence Medical Education

Structured approach to the Reporting In healthcare education of Evidence Synthesis

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Systematic Scoping Review

Systematic Evidence-Based Approach

Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine

Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study Design

Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses - Evolving Standards

Wang Y-H, Liao H-C. Construction and validation of an analytic reflective writing scoring rubric for healthcare students and providers. 醫學教育. 2020;24(2):53–72.

Google Scholar

Dewey J. How we think: a restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. Am J Psychol. 1933;46:528.

Schon DA. The reflective practitioner: how professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books; 1983.

Schon DA. Educating the reflective practitioner: towards a new design for teaching and learning in the profession. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987.

Kolb DA. Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall; 1984.

Boud D, Keogh R, Walker D. Reflection: turning experience into learning. London: Kogan Page; 1985.

Mezirow J. Fostering critical reflection in adulthood: a guide to transformative and emancipatory learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1990.

Sarraf-Yazdi S, Teo YN, How AEH, Teo YH, Goh S, Kow CS, et al. A scoping review of professional identity formation in undergraduate medical education. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(11):3511–21.

Article Google Scholar

Mann K, Gordon J, MacLeod A. Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: a systematic review. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2009;14(4):595–621.

Teo KJH, Teo MYK, Pisupati A, Ong RSR, Goh CK, Seah CHX, et al. Assessing professional identity formation (PIF) amongst medical students in Oncology and Palliative Medicine postings: a SEBA guided scoping review. BMC Palliat Care. 2022;21(1):200.

Radha Krishna LK, Alsuwaigh R. Understanding the fluid nature of personhood - the ring theory of personhood. Bioethics. 2015;29(3):171–81.

Ryan M, Ryan M. Theorising a model for teaching and assessing reflective learning in higher education. High Educ Res Dev. 2013;32(2):244–57.

Huang H, Toh RQE, Chiang CLL, Thenpandiyan AA, Vig PS, Lee RWL, et al. Impact of dying neonates on doctors’ and nurses’ personhood: a systematic scoping review. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2022;63(1):e59–74.

Vig PS, Lim JY, Lee RW, Huang H, Tan XH, Lim WQ, et al. Parental bereavement–impact of death of neonates and children under 12 years on personhood of parents: a systematic scoping review. BMC Palliat Care. 2021;20(1):1–7.

Chan NPX, Chia JL, Ho CY, Ngiam LXL, Kuek JTY, Ahmad Kamal NHB, et al. Extending the ring theory of personhood to the care of dying patients in intensive care units. Asian Bioeth Rev. 2022;14(1):71–86.

Tay J, Compton S, Phua G, Zhuang Q, Neo S, Lee G, et al. Perceptions of healthcare professionals towards palliative care in internal medicine wards: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Palliat Care. 2021;20(1):101.

Teo YH, Peh TY, Abdurrahman A, Lee ASI, Chiam M, Fong W, et al. A modified Delphi approach to enhance nurturing of professionalism in postgraduate medical education in Singapore. Singap Med J. 2021. https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2021224 .

Chiam M, Ho CY, Quah E, Chua KZY, Ng CWH, Lim EG, et al. Changing self-concept in the time of COVID-19: a close look at physician reflections on social media. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2022;17(1):1.

Zhou JX, Goh C, Chiam M, Krishna LKR. Painting and Poetry From a Bereaved Family and the Caring Physician. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;S0885-3924(22):00476-6.

Cheong CWS, Quah ELY, Chua KZY, Lim WQ, Toh RQE, Chiang CLL, et al. Post graduate remediation programs in medicine: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):294.

Goh S, Wong RSM, Quah ELY, Chua KZY, Lim WQ, Ng ADR, et al. Mentoring in palliative medicine in the time of covid-19: a systematic scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):359.

Venktaramana V, Loh EKY, Wong CJW, Yeo JW, Teo AYT, Chiam CSY, et al. A systematic scoping review of communication skills training in medical schools between 2000 and 2020. Med Teach. 2022;44(9):997-1006.

Chia EW, Huang H, Goh S, Peries MT, Lee CC, Tan LH, et al. A systematic scoping review of teaching and evaluating communications in the intensive care unit. Asia Pac Schol. 2021;6(1):3–29.

Toh RQE, Koh KK, Lua JK, Wong RSM, Quah ELY, Panda A, et al. The role of mentoring, supervision, coaching, teaching and instruction on professional identity formation: a systematic scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):531.

Charon R, Hermann N. Commentary: a sense of story, or why teach reflective writing? Acad Med. 2012;87(1):5–7.

Matinho D, Pietrandrea M, Echeverria C, Helderman R, Masters M, Regan D, et al. A systematic review of integrated learning definitions, frameworks, and practices in recent health professions education literature. Educ Sci. 2022;12(3):165.

Saltman DC, Tavabie A, Kidd MR. The use of reflective and reasoned portfolios by doctors. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(1):182–5.

Kinsella EA. Technical rationality in Schön’s reflective practice: dichotomous or non-dualistic epistemological position. Nurs Philos. 2007;8(2):102–13.

Tsingos C, Bosnic-Anticevich S, Smith L. Reflective practice and its implications for pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(1):18.

Arntfield S, Parlett B, Meston CN, Apramian T, Lingard L. A model of engagement in reflective writing-based portfolios: interactions between points of vulnerability and acts of adaptability. Med Teach. 2016;38(2):196–205.

Edgar L, et al. ACGME: the milestones guidebook. 2020. Available from: https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/milestonesguidebook.pdf .

Council GM. Tomorrow’s doctors. 2009. Available from: http://www.ub.edu/medicina_unitateducaciomedica/documentos/TomorrowsDoctors_2009.pdf .

Council GM. The reflective practitioner - guidance for doctors and medical students. Available from: https://www.gmc-uk.org/education/standards-guidance-and-curricula/guidance/reflective-practice/the-reflective-practitioner-guidance-for-doctors-and-medical-students . Accessed 3 Aug 2022.

England RCoSo. Good surgical practice. Available from: https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/standards-and-research/gsp/ . Accessed 3 Aug 2022.

Physicians TRACo. The Royal Australasian College of Physicians basic training curriculum standards: competencies. 2017. Available from: https://www.racp.edu.au/docs/default-source/default-document-library/competencies-for-basic-trainees-in-adult-internal-medicine-and-paediatrics-child-health.pdf?sfvrsn=6fdc0d1a_4 .

Surgeons RACo. RACS competencies. Available from: https://www.surgeons.org/en/Trainees/the-set-program/racs-competencies . Accessed 3 Aug 2022.

Murdoch-Eaton D, Sandars J. Reflection: moving from a mandatory ritual to meaningful professional development. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99(3):279–83.

Thompson N, Pascal J. Developing critically reflective practice. Reflective Pract. 2012;13(2):311–25.

Rodgers C. Defining reflection: another look at John Dewey and reflective thinking. Teach Coll Rec. 2002;104:842–66.

Hinchcliff R, Greenfield D, Moldovan M, Westbrook JI, Pawsey M, Mumford V, et al. Narrative synthesis of health service accreditation literature. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(12):979–91.

Boden C, Ascher MT, Eldredge JD. Learning while doing: program evaluation of the medical library association systematic review project. J Med Libr Assoc. 2018;106(3):284.

Mays N, Roberts E, Popay J. Synthesising research evidence. Studying the organisation and delivery of health services: research methods; 2001. p. 220.

Davey S, Davey A, Singh J. Metanarrative review: current status and opportunities for public health research. Int J Health Syst Disaster Manag. 2013;1(2):59–63.

Greenhalgh T, Wong G. Training materials for meta-narrative reviews. UK: Global Health Innovation and Policy Unit Centre for Primary Care and Public Health Blizard Institute, Queen Mary University of London; 2013.

Osama T, Brindley D, Majeed A, Murray KA, Shah H, Toumazos M, et al. Teaching the relationship between health and climate change: a systematic scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2018;8(5):e020330.

Chua KZY, Quah ELY, Lim YX, Goh CK, Lim J, Wan DWJ, et al. A systematic scoping review on patients’ perceptions of dignity. BMC Palliat Care. 2022;21(1):118.

Hong DZ, Lim AJS, Tan R, Ong YT, Pisupati A, Chong EJX, et al. A systematic scoping review on portfolios of medical educators. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2021;8:23821205211000356.

Tay KT, Ng S, Hee JM, Chia EWY, Vythilingam D, Ong YT, et al. Assessing professionalism in medicine - a scoping review of assessment tools from 1990 to 2018. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:2382120520955159.

Lim C, Zhou JX, Woong NL, Chiam M, Krishna LKR. Addressing the needs of migrant workers in ICUs in Singapore. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:2382120520977190.

Ong YT, Quek CWN, Pisupati A, Loh EKY, Venktaramana V, Chiam M, et al. Mentoring future mentors in undergraduate medical education. PLoS One. 2022;17(9):e0273358.

Kuek JTY, Ngiam LXL, Kamal NHA, Chia JL, Chan NPX, Abdurrahman ABHM, et al. The impact of caring for dying patients in intensive care units on a physician’s personhood: a systematic scoping review. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2020;15(1):12.

Ngiam L, Ong YT, Ng JX, Kuek J, Chia JL, Chan N, et al. Impact of caring for terminally ill children on physicians: a systematic scoping review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2021;38(4):396–418.

Ho CY, Lim N-A, Ong YT, Lee ASI, Chiam M, Gek GPL, et al. The impact of death and dying on the personhood of senior nurses at the National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS): a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care. 2022;21(1):1–10.

Quah ELY, Chua KZY, Lua JK, Wan DWJ, Chong CS, Lim YX, et al. A systematic review of stakeholder perspectives of dignity and assisted dying. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.10.004 .

Quek CWN, Ong RRS, Wong RSM, Chan SWK, Chok AK-L, Shen GS, et al. Systematic scoping review on moral distress among physicians. BMJ Open. 2022;12(9):e064029.

Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Buckingham J, Pawson R. RAMESES publication standards: meta-narrative reviews. BMC Med. 2013;11(1):20.

Pring R. The ‘false dualism’of educational research. J Philos Educ. 2000;34(2):247–60.

Crotty M. The foundations of social research: meaning and perspective in the research process. Thousand Oaks: SAGE; 1998.

Ford K. Taking a narrative turn: possibilities, challenges and potential outcomes. OnCUE J. 2012;6(1):23-36.

Schick-Makaroff K, MacDonald M, Plummer M, Burgess J, Neander W. What synthesis methodology should I use? A review and analysis of approaches to research synthesis. AIMS Public Health. 2016;3:172–215.

Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Soares C, Khalil H, Parker D. The Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual 2015: methodology for JBI scoping reviews2015 April 29, 2019. Available from: http://joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/sumari/Reviewers-Manual_Methodology-for-JBI-Scoping-Reviews_2015_v1.pdf .

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–6.

Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. New York: Springer; 2007.

Chua WJ, Cheong CWS, Lee FQH, Koh EYH, Toh YP, Mason S, et al. Structuring mentoring in medicine and surgery. A systematic scoping review of mentoring programs between 2000 and 2019. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2020;40(3):158–68.

Ng YX, Koh ZYK, Yap HW, Tay KT, Tan XH, Ong YT, et al. Assessing mentoring: a scoping review of mentoring assessment tools in internal medicine between 1990 and 2019. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0232511.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Cassol H, Pétré B, Degrange S, Martial C, Charland-Verville V, Lallier F, et al. Qualitative thematic analysis of the phenomenology of near-death experiences. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0193001.

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88.

Wald H, Reis S. Beyond the margins: fostering reflective capacity through reflective writing in medical education. J Gen Int Med. 2010;25:746–9.

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme version, vol. 1; 2006. p. b92.

France EF, Wells M, Lang H, Williams B. Why, when and how to update a meta-ethnography qualitative synthesis. Syst Rev. 2016;5:44.

Noblit GW, Hare RD, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1988.

Book Google Scholar

Gibbs G. Learning by doing: a guide to teaching and learning methods. Thousand Oaks: FEU; 1988.

Koole S, Dornan T, Aper L, Scherpbier A, Valcke M, Cohen-Schotanus J, et al. Factors confounding the assessment of reflection: a critical review. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11(1):104.

Day C. Reflection: A Necessary but Not Sufficient Condition for Professional Development. British Educational Research Journal. 1993;19(1):83–93.

Sweet L, Bass J, Sidebotham M, Fenwick J, Graham K. Developing reflective capacities in midwifery students: enhancing learning through reflective writing. Women Birth. 2019;32(2):119–26.

Mezirow J. Understanding transformation theory. Adult Educ Q. 1994;44(4):222–32.

Korthagen F, Vasalos A. Levels in reflection: core reflection as a means to enhance professional growth. Teach Teach. 2005;11(1):47–71.

McLeod N. Reflecting on reflection: improving teachers’ readiness to facilitate participatory learning with young children. Prof Dev Educ. 2015;41(2):254–72.

Ash SL, Clayton PH. The articulated learning: an approach to guided reflection and assessment. Innov High Educ. 2004;29(2):137–54.

Ash S, Clayton P. Generating, deepening, and documenting learning: the power of critical reflection in applied learning. J Appl Learn High Educ. 2009;1:25–48.

Lay K, McGuire L. Teaching students to deconstruct life experience with addictions: a structured reflection exercise. J Teach Addict. 2008;7(2):145–63.

Lay K, McGuire L. Building a lens for critical reflection and reflexivity in social work education. Soc Work Educ. 2010;29(5):539–50.

Johns C. Nuances of reflection. J Clin Nurs. 1994;3(2):71–4.

Kim HS. Critical reflective inquiry for knowledge development in nursing practice. J Adv Nurs. 1999;29(5):1205–12.

Roskos K, Vukelich C, Risko V. Reflection and learning to teach reading: a critical review of literacy and general teacher education studies. J Lit Res. 2001;33:595–635.

Burnham J. Developments in Social GGRRAAACCEEESSS: visible-invisible, voiced-unvoiced. In I. Krause (Ed.), Cultural Reflexivity. London: Karnac.

Pearson M, Smith D. In: Boud D, Keogh R, Walker D, editors. Debriefing in experience-based learning, reflection: turning experience into learning. London: Kogan Page; 1985.

Argyris C, Schön DA. Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective, Reading, Mass: Addison Wesley. 1978.

Mamede S, Schmidt HG. The structure of reflective practice in medicine. Med Educ. 2004;38(12):1302–8.

Ryan M. Improving reflective writing in higher education: a social semiotic perspective. Teach High Educ. 2011;16(1):99–111.

Beauchamp C. Understanding reflection in teaching: a framework for analyzing the literature; 2006.

Atkins S, Murphy K. Reflection: a review of the literature. J Adv Nurs. 1993;18(8):1188–92.

Carver CS, Scheier MF. On the self-regulation of behavior, vol. xx. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1998. p. 439–xx.

Grant A. The impact of life coaching on goal attainment, metacognition and mental health. Soc Behav Personal Int J. 2003;31:253–63.

Thorpe K. Reflective learning journals: from concept to practice. Reflective Pract. 2004;5(3):327–43.

van Manen M. The tact of teaching: the meaning of pedagogical thoughtfulness. NY: SUNY Press; 1991a.

Plack MM, Driscoll M, Marquez M, Cuppernull L, Maring J, Greenberg L. Assessing reflective writing on a pediatric clerkship by using a modified Bloom’s taxonomy. Ambul Pediatr. 2007;7(4):285–91.

Rogers J, Peecksen S, Douglas M, Simmons M. Validation of a reflection rubric for higher education. Reflective Pract. 2019;20(6):761–76.

Makarem NN, Saab BR, Maalouf G, Musharafieh U, Naji F, Rahme D, et al. Grading reflective essays: the reliability of a newly developed tool- GRE-9. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):331.

Bain J, Ballantyne R, Mills C, Lester N. Reflecting on practice: student teachers’ perspectives; 2002.

Kember D, Leung DYP, Jones A, Loke AY, McKay J, Sinclair K, et al. Development of a questionnaire to measure the level of reflective thinking. Assess Eval High Educ. 2000;25(4):381–95.

Hatton N, Smith D. Reflection in teacher education: towards definition and implementation. Teach Teach Educ. 1995;11(1):33–49.

Moon JA. Reflection in learning and professional development: theory and practice; 1999.

Wald HS, Borkan JM, Taylor JS, Anthony D, Reis SP. Fostering and evaluating reflective capacity in medical education: developing the REFLECT rubric for assessing reflective writing. Acad Med. 2012;87(1):41–50.

Stein D. Teaching critical reflection. Myths and realities no. 7. Undefined; 2000. p. 1–4.

Morrow E. Teaching critical reflection. Teach High Educ. 2011;16:211–23.

Plack MM, Driscoll M, Blissett S, McKenna R, Plack TP. A method for assessing reflective journal writing. J Allied Health. 2005;34(4):199–208.

Aukes LC, Geertsma J, Cohen-Schotanus J, Zwierstra RP, Slaets JP. The development of a scale to measure personal reflection in medical practice and education. Med Teach. 2007;29(2–3):177–82.

Bradley J. A model for evaluating student learning in academically based service. In: Connecting cognition and action: evaluation of student performance in service learning courses; 1995. p. 13–26.

Lee H-J. Understanding and assessing preservice teachers’ reflective thinking. Teach Teach Educ. 2005;21(6):699–715.

Kanthan R, Senger JL. An appraisal of students’ awareness of “self-reflection” in a first-year pathology course of undergraduate medical/dental education. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11:67.