- Ebooks & Courses

- Practice Tests

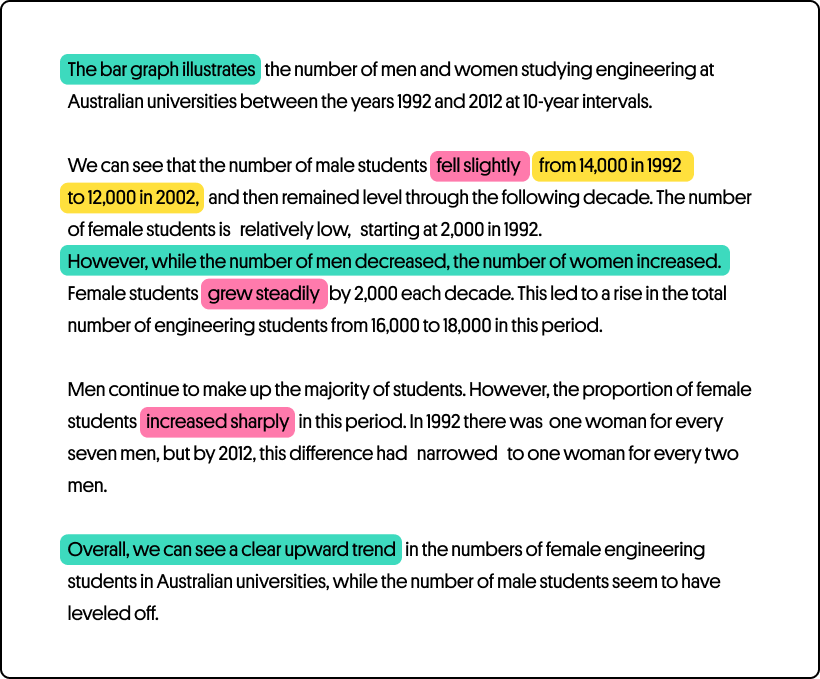

How To Write an IELTS Bar Chart Essay

There are 5 steps to writing a good IELTS bar chart essay:

1) Analyse the question

2) Identify the main features

3) Write an introduction

4) Write an overview

5) Write the details paragraphs

Use this simple planning process as you practice writing IELTS bar chart essays and you’ll have no problem remembering it in the exam.

Steps 1 and 2 of the planning process should take around 5 minutes. It is essential that you don’t miss these out as they are the key to writing a high-scoring essay.

On this page, I’m going to take you through the whole planning process step-by-step as we work on a practice question.

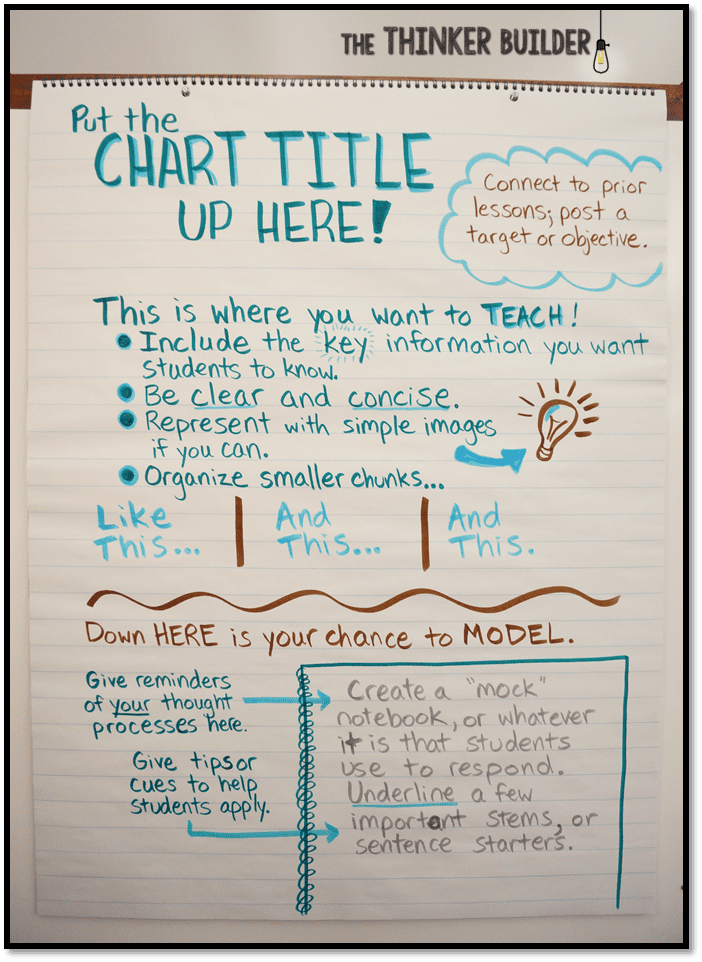

Before we begin, here’s a model essay structure that you can use as a guideline for all IELTS Academic Task 1 questions.

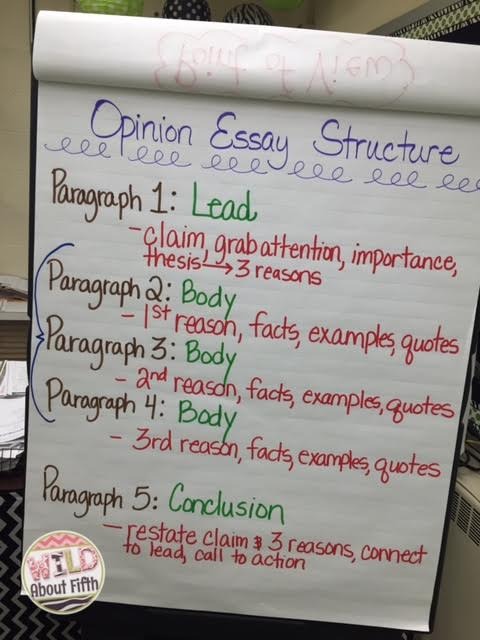

Ideally, your essay should have 4 paragraphs:

Paragraph 1 – Introduction

Paragraph 2 – Overview

Paragraph 3 – 1 st main feature

Paragraph 4 – 2 nd main feature

Now that we have all these tools we need, we’re ready to begin planning and writing our IELTS bar chart essay.

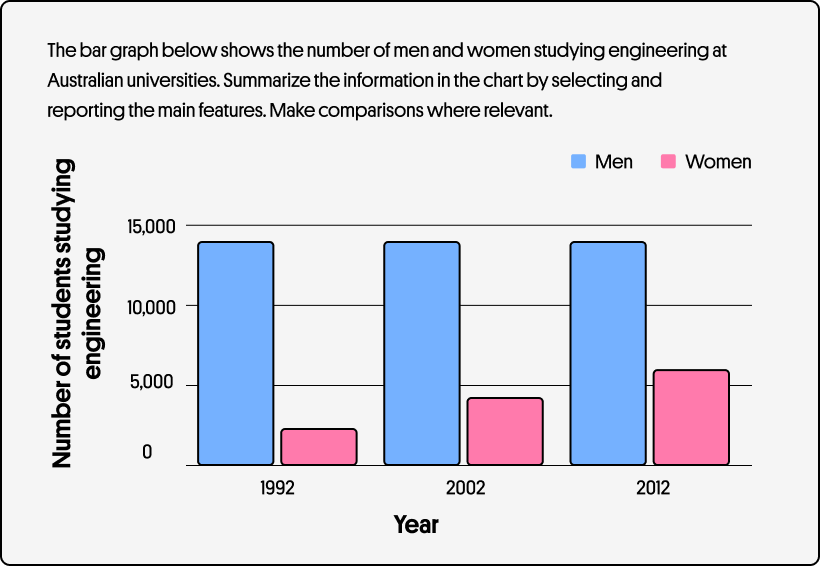

Here’s our practice question:

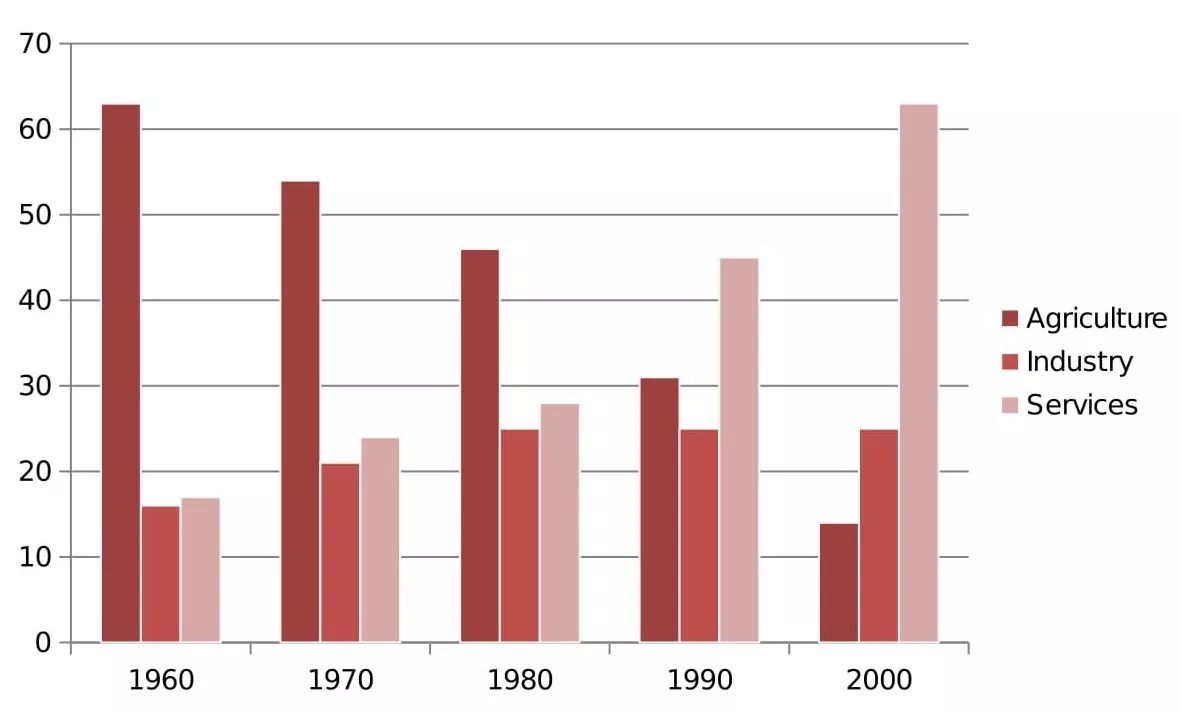

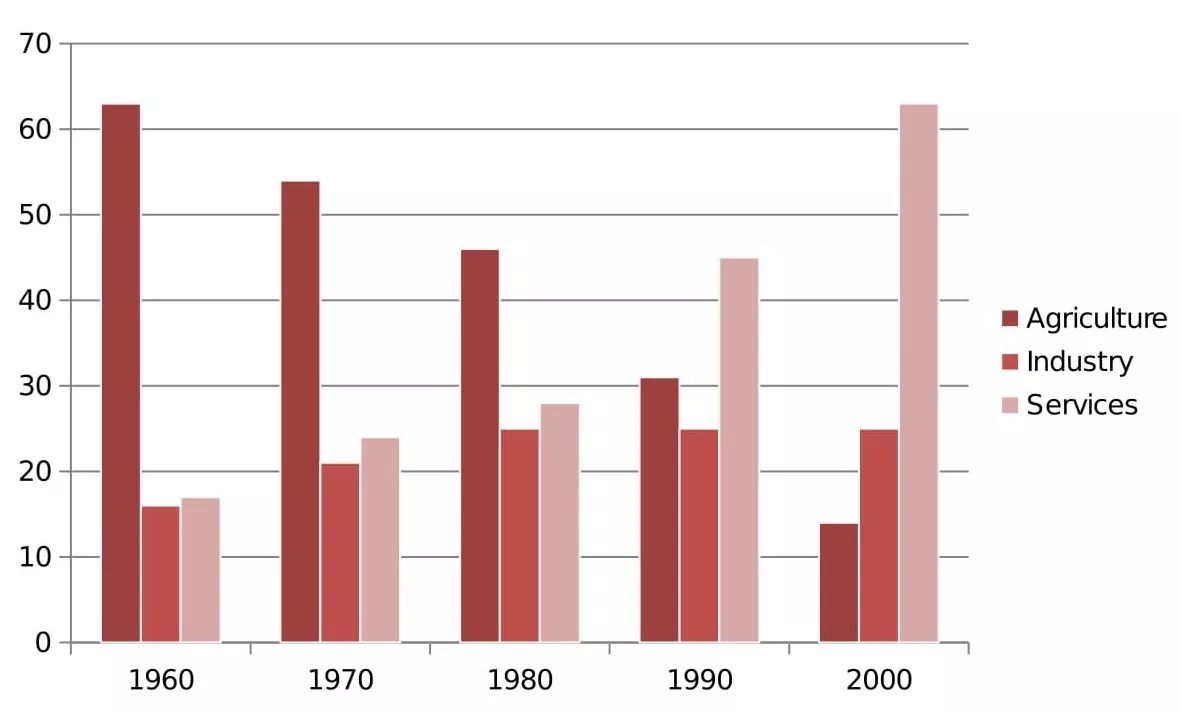

The bar chart below shows the sector contributions to India’s gross domestic product from 1960 to 2000.

Summarise the information by selecting and reporting the main features, and make comparisons where relevant.

Write at least 150 words.

Contribution as % of India's GDP

Source: EPW Research Foundation

Step 1 – Analyse the question

The format of every Academic Task 1 question is the same. Here is our practice question again with the words that will be included in all questions highlighted .

The bar chart below shows the sector contributions to India’s gross domestic product from 1960 to 2000.

Every question consists of:

- Sentence 1 – A brief description of the graphic

- Sentence 2 – The instructions

- The graphic – chart, graph, table, etc.

Sentence 2 tells you what you have to do.

You must do 3 things:

1. Select the main features.

2. Write about the main features.

3. Compare the main features.

All three tasks refer to the ‘ main features ’ of the graphic. You do not have to write about everything. Just pick out 2 or 3 key features and you’ll have plenty to write about.

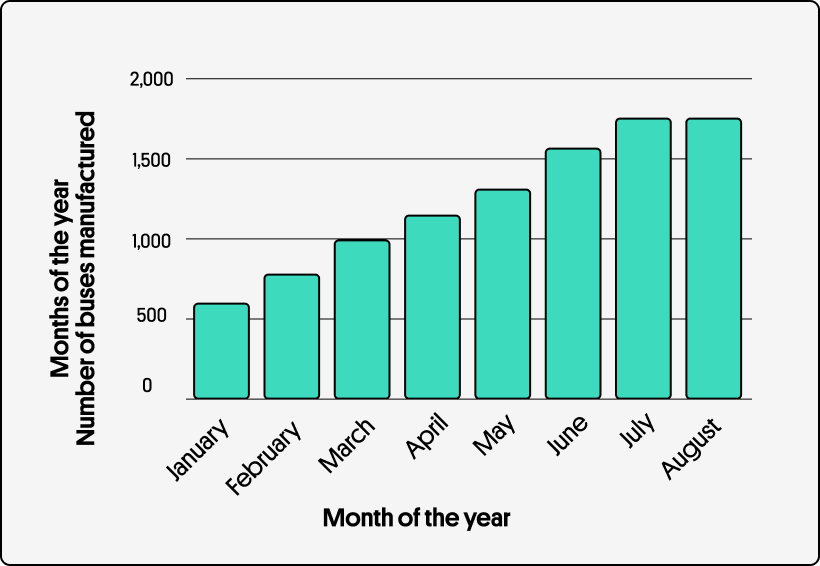

Our practice graphic is a dynamic bar chart. That is, it includes a timeline giving data from several different points in time.

So, for this question, we need to identify the main trends (that is, the general developments or changes in situation) in the three key sectors of the Indian economy – agriculture, industry and service – between 1960 and 2000.

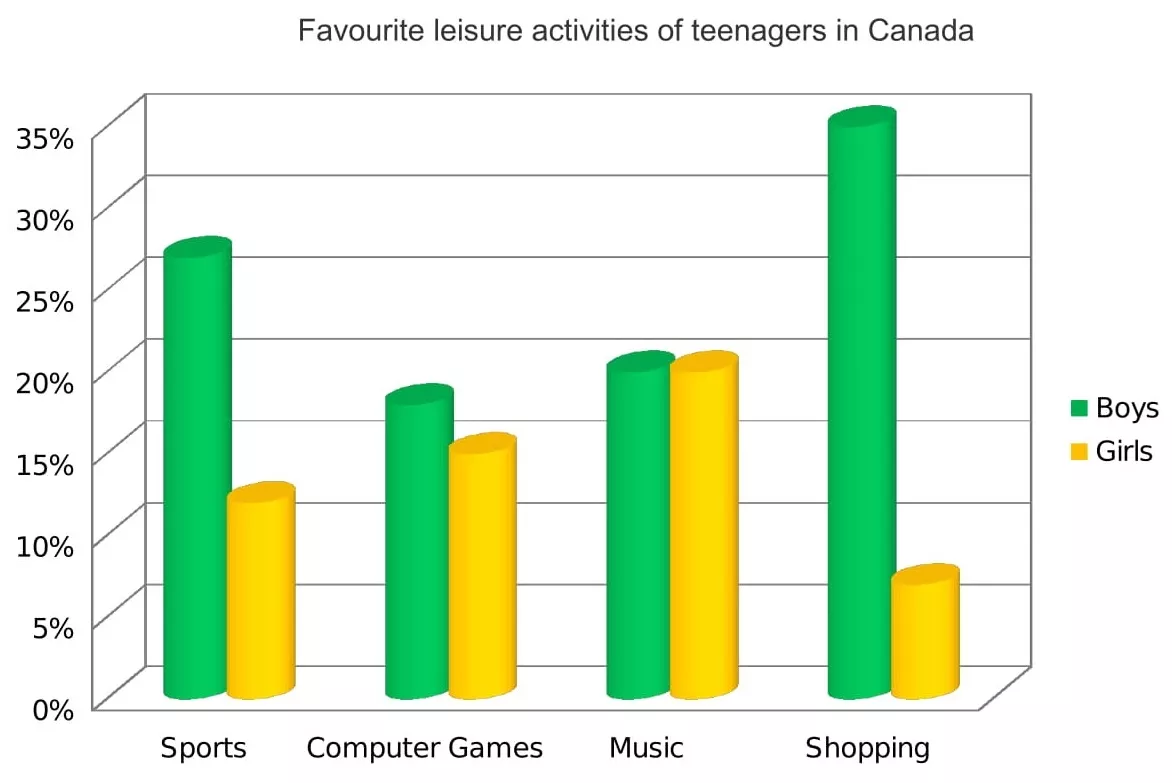

Alternatively, a bar chart may be static with the data coming from one point in time, as in the example below. For this graphic, we would need to compare the different variables, that is, the different leisure activities favoured by Canadian boys and girls.

Step 2 – Identify the Main Features

The graphic in IELTS bar chart questions should not be difficult to interpret. Each question has been created to test your language skills, not your mathematics ability.

All you are looking for are the main features. These will usually be the easiest things to spot. As we’ve just seen, the type of key features will depend on whether the bar chart is dynamic or static.

There will be lots of information in the graphic to help you identify them. Here are some useful questions to ask?

- What information do the 2 axes give?

- Is it dynamic or static?

- What are the units of measurements?

- What are the time periods?

- What can you learn from the title and any labels?

- What is the most obvious trend?

- Are there any notable similarities?

(I give more detail on how to use these questions, plus downloadable checklists for identifying the main features of all 7 different types of IELTS Academic Writing Task 1 questions, in the lesson on How To Understand & Analyse Task 1 Questions .)

So, what main features stand out in our practice graphic?

Here's our practice IELTS bar chart again.

There are 3 main features/trends in this IELTS bar chart:

Main feature 1: The contribution of the agricultural sector dropped steadily.

Main feature 2: The contribution of the service sector increased each decade.

Main feature 3: Industry remained static from 1980 to 2000.

The general trends you select will be the starting point for your essay. You will then go on to add more detail.

With just 20 minutes allowed for Task 1, and a requirement of only 150 words, you won't be able to include many details.

We’re now ready to begin writing our essay. Here’s a reminder of the 4 part structure we’re going to use.

Step 3 – Write an Introduction

In the introduction, you should simply paraphrase the question, that is, say the same thing in a different way. You can do this by using synonyms and changing the sentence structure. For example:

Introduction (Paragraph 1):

The bar graph illustrates the relative percentage contributions made by the agricultural, industrial and service sectors to the Indian economy between 1960 and 2000.

This is all you need to do for the introduction.

Ideally, key words such as ‘sector’ and ‘contributions’ should be replaced by synonyms but there aren’t any obvious words that could be used instead so it’s fine to repeat them. It’s important that your language sounds natural so never try to force in synonyms that don’t quite fit.

Step 4 – Write an Overview (Paragraph 2)

In the second paragraph, you should report the main features you can see in the graph, giving only general information. The detail comes later in the essay. You should also make any clear comparisons you spot.

This is where we write about the general trends. Here are the ones we picked out above.

Now form these ideas into two or three sentences with a total of around 40 words. State the information simply using synonyms where possible. No elaborate vocabulary or grammar structures are required, just the appropriate words and correct verb tenses.

For example:

Overview (Paragraph 2) :

Over the whole time period, the significance of agriculture declined steadily while services grew in importance decade by decade. A different patterned emerged for industry, which initially showed a slowly increasing percentage but then plateaued from 1980 onwards.

Step 5 – Write the 1st Detail Paragraph

Paragraphs 3 and 4 of your IELTS bar chart essay are where you include more detailed information about the data in the graphic. In paragraph 3, you should give evidence to support your first 1 or 2 key features. Don’t forget to make comparisons when relevant.

Here are our first 2 main features again:

And this is an example of what you could write:

Paragraph 3 :

In 1960, agriculture contributed by far the highest percentage of GDP, peaking at 62%, but it then dropped in steady increments to a low of 12% in 2000. The service sector, on the other hand, had a relatively minor impact on the economy in 1960. This situation changed gradually at first, then its percentage contribution jumped from 28% to 43% between 1980 and 1990. By 2000 it matched the high point reached by agriculture in 1960, showing a reversal in the overall trend.

Step 6 – Write the 2nd Detail Paragraph

For the fourth and final paragraph, you do the same thing for your remaining feature/s. We have one main feature left to write about.

Here’s an example of what you could write:

Paragraph 4 :

Industry remained a steady contributor to India’s wealth throughout the period. As a sector, it grew marginally from 16% in 1960 to exactly a quarter in 1980 then remained static for the next two decades, maintaining a constant share of the overall GDP.

Here are the four paragraphs brought together to create our finished essay.

Finished IELTS Bar Chart Essay

(188 words)

This sample IELTS bar chart essay is well over the minimum word limit so you can see that you don’t have space to include very much detail at all. That’s why it is essential to select just a couple of main features to write about.

Now use what you’ve learnt in this lesson to practice answering other IELTS bar chart questions. Start slowly at first and keep practicing until you can plan and write a complete essay in around 20 minutes.

Want to watch and listen to this lesson?

Click on this video.

Would you prefer to share this page with others by linking to it?

- Click on the HTML link code below.

- Copy and paste it, adding a note of your own, into your blog, a Web page, forums, a blog comment, your Facebook account, or anywhere that someone would find this page valuable.

Like this page?

Ielts academic writing task 1 – all lessons.

IELTS Academic Writing – A summary of the test including important facts, test format & assessment.

Academic Writing Task 1 – The format, the 7 question types & sample questions, assessment & marking criteria. All the key information you need to know.

Understanding Task 1 Questions – How to quickly and easily analyse and understand IELTS Writing Task 2 questions.

How To Plan a Task 1 Essay – Discover 3 reasons why you must plan, the 4 simple steps of essay planning and learn a simple 4 part essay structure.

Vocabulary for Task 1 Essays – Learn key vocabulary for a high-scoring essay. Word lists & a downloadable PDF.

Grammar for Task 1 Essays – Essential grammar for Task 1 Academic essays including, verb tenses, key sentence structures, articles & prepositions.

The 7 Question Types:

Click the links below for a step-by-step lesson on each type of Task 1 question.

- Table Chart

- Process Diagram

- Multiple Graphs

- IELTS Writing

- IELTS Bar Chart

- Back To Top

* New * Grammar For IELTS Ebooks

$9.99 each Full Set Just $ 23.97

Find Out More >>

IELTS Courses

Full details...

IELTS Writing Ebook

Discount Offer

$7 each Full Set Just $ 21

Find out more >>

Testimonials

“I am very excited to have found such fabulous and detailed content. I commend your good work.” Jose M.

“Thanks for the amazing videos. These are ‘to the point’, short videos, beautifully explained with practical examples." Adari J.

"Hi Jacky, I bought a listening book from you this morning. You know what? I’m 100% satisfied. It’s super helpful. If I’d had the chance to read this book 7 years ago, my job would be very different now." Loi H.

"Hi Jacky, I recently got my IELTS results and I was pleased to discover that I got an 8.5 score. I'm firmly convinced your website and your videos played a strategic role in my preparation. I was able to improve my writing skills thanks to the effective method you provide. I also only relied on your tips regarding the reading section and I was able to get a 9! Thank you very much." Giano

“After listening to your videos, I knew I had to ditch every other IELTS tutor I'd been listening to. Your explanations are clear and easy to understand. Anyways, I took the test a few weeks ago and my result came back: Speaking 7, listening 9, Reading 8.5 and Writing 7 with an average band score of 8. Thanks, IELTS Jacky." Laide Z.

Contact

About Me

Site Map

Privacy Policy

Disclaimer

IELTS changes lives.

Let's work together so it changes yours too.

Copyright © 2024 IELT Jacky

All Right Reserved

IELTS is a registered trademark of the University of Cambridge, the British Council, and IDP Education Australia. This site and its owners are not affiliated, approved or endorsed by the University of Cambridge ESOL, the British Council, and IDP Education Australia.

Figures and Charts

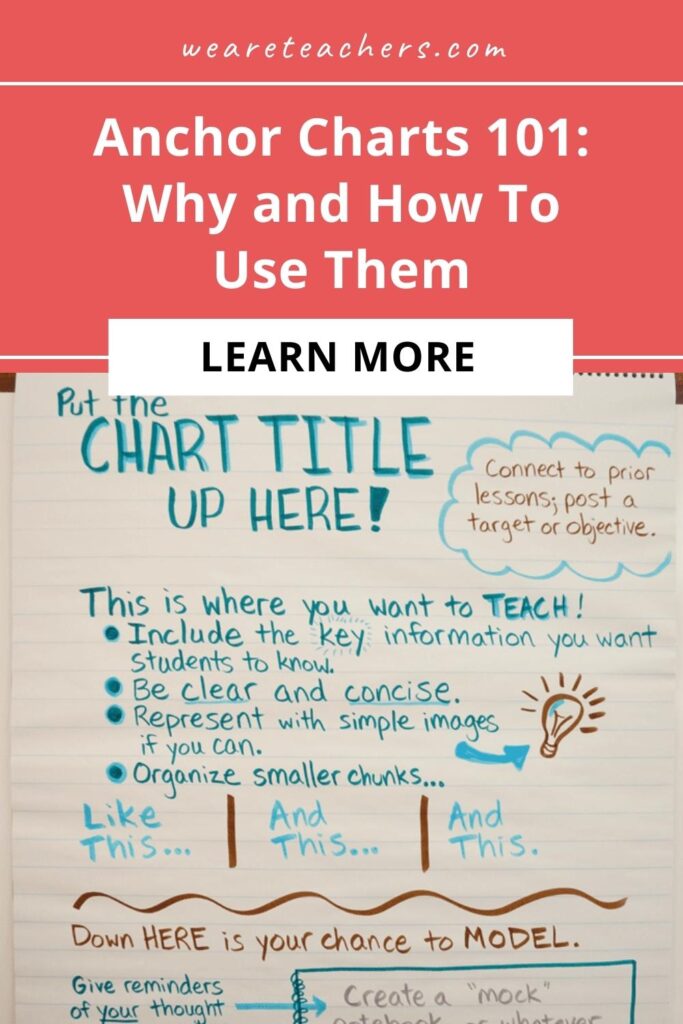

What this handout is about.

This handout will describe how to use figures and tables to present complicated information in a way that is accessible and understandable to your reader.

Do I need a figure/table?

When planning your writing, it is important to consider the best way to communicate information to your audience, especially if you plan to use data in the form of numbers, words, or images that will help you construct and support your argument. Generally speaking, data summaries may take the form of text, tables or figures. Most writers are familiar with textual data summaries and this is often the best way to communicate simple results. A good rule of thumb is to see if you can present your results clearly in a sentence or two. If so, a table or figure is probably unnecessary. If your data are too numerous or complicated to be described adequately in this amount of space, figures and tables can be effective ways of conveying lots of information without cluttering up your text. Additionally, they serve as quick references for your reader and can reveal trends, patterns, or relationships that might otherwise be difficult to grasp.

So what’s the difference between a table and a figure anyway?

Tables present lists of numbers or text in columns and can be used to synthesize existing literature, to explain variables, or to present the wording of survey questions. They are also used to make a paper or article more readable by removing numeric or listed data from the text. Tables are typically used to present raw data, not when you want to show a relationship between variables.

Figures are visual presentations of results. They come in the form of graphs, charts, drawings, photos, or maps. Figures provide visual impact and can effectively communicate your primary finding. Traditionally, they are used to display trends and patterns of relationship, but they can also be used to communicate processes or display complicated data simply. Figures should not duplicate the same information found in tables and vice versa.

Using tables

Tables are easily constructed using your word processor’s table function or a spread sheet program such as Excel. Elements of a table include the Legend or Title, Column Titles, and the Table Body (quantitative or qualitative data). They may also include subheadings and footnotes. Remember that it is just as important to think about the organization of tables as it is to think about the organization of paragraphs. A well-organized table allows readers to grasp the meaning of the data presented with ease, while a disorganized one will leave the reader confused about the data itself, or the significance of the data.

Title: Tables are headed by a number followed by a clear, descriptive title or caption. Conventions regarding title length and content vary by discipline. In the hard sciences, a lengthy explanation of table contents may be acceptable. In other disciplines, titles should be descriptive but short, and any explanation or interpretation of data should take place in the text. Be sure to look up examples from published papers within your discipline that you can use as a model. It may also help to think of the title as the “topic sentence” of the table—it tells the reader what the table is about and how it’s organized. Tables are read from the top down, so titles go above the body of the table and are left-justified.

Column titles: The goal of column headings is to simplify and clarify the table, allowing the reader to understand the components of the table quickly. Therefore, column titles should be brief and descriptive and should include units of analysis.

Table body: This is where your data are located, whether they are numerical or textual. Again, organize your table in a way that helps the reader understand the significance of the data. Be sure to think about what you want your readers to compare, and put that information in the column (up and down) rather than in the row (across). In other words, construct your table so that like elements read down, not across. When using numerical data with decimals, make sure that the decimal points line up. Whole numbers should line up on the right.

Other table elements

Tables should be labeled with a number preceding the table title; tables and figures are labeled independently of one another. Tables should also have lines demarcating different parts of the table (title, column headers, data, and footnotes if present). Gridlines or boxes should not be included in printed versions. Tables may or may not include other elements, such as subheadings or footnotes.

Quick reference for tables

Tables should be:

- Centered on the page.

- Numbered in the order they appear in the text.

- Referenced in the order they appear in the text.

- Labeled with the table number and descriptive title above the table.

- Labeled with column and/or row labels that describe the data, including units of measurement.

- Set apart from the text itself; text does not flow around the table.

Table 1. Physical characteristics of the Doctor in the new series of Doctor Who

| Height | Age (yrs.) | |

| Ninth Doctor | 6’0” | 41 |

| Tenth Doctor | 6’1” | 35 |

| Eleventh Doctor | 5’11” | 25 |

Table 2. Physical characteristics of the Doctor in the new series of Doctor Who

| Personal Appearance | Wardrobe | |

| Ninth Doctor | Close-cropped hair Blue eyes Slightly stockier build | Black leather jacket Dark colored, v-necked shirts Black combat boots |

| Tenth Doctor | Longer, mussed-up hair Brown eyes Very thin build | Beige trench coat Pin-striped suit and tie Chuck Taylors |

| Eleventh Doctor | Longer, side-swept hair Green eyes Slightly stockier build | Brown tweed jacket Bow tie and suspenders Black Boots |

Using figures

Figures can take many forms. They may be graphs, diagrams, photos, drawings, or maps. Think deliberately about your purpose and use common sense to choose the most effective figure for communicating the main point. If you want your reader to understand spatial relationships, a map or photograph may be the best choice. If you want to illustrate proportions, experiment with a pie chart or bar graph. If you want to illustrate the relationship between two variables, try a line graph or a scatterplot (more on various types of graphs below). Although there are many types of figures, like tables, they share some typical features: captions, the image itself, and any necessary contextual information (which will vary depending on the type of figure you use).

Figure captions

Figures should be labeled with a number followed by a descriptive caption or title. Captions should be concise but comprehensive. They should describe the data shown, draw attention to important features contained within the figure, and may sometimes also include interpretations of the data. Figures are typically read from the bottom up, so captions go below the figure and are left-justified.

The most important consideration for figures is simplicity. Choose images the viewer can grasp and interpret clearly and quickly. Consider size, resolution, color, and prominence of important features. Figures should be large enough and of sufficient resolution for the viewer to make out details without straining their eyes. Also consider the format your paper will ultimately take. Journals typically publish figures in black and white, so any information coded by color will be lost to the reader. On the other hand, color might be a good choice for papers published to the web or for PowerPoint presentations. In any case, use figure elements like color, line, and pattern for effect, not for flash.

Additional information

Figures should be labeled with a number preceding the table title; tables and figures are numbered independently of one another. Also be sure to include any additional contextual information your viewer needs to understand the figure. For graphs, this may include labels, a legend explaining symbols, and vertical or horizontal tick marks. For maps, you’ll need to include a scale and north arrow. If you’re unsure about contextual information, check out several types of figures that are commonly used in your discipline.

Quick reference for figures

Figures should be:

- Labeled (under the figure) with the figure number and appropriate descriptive title (“Figure” can be spelled out [“Figure 1.”] or abbreviated [“Fig. 1.”] as long as you are consistent).

- Referenced in the order they appear in the text (i.e. Figure 1 is referenced in the text before Figure 2 and so forth).

- Set apart from the text; text should not flow around figures.

Every graph is a figure but not every figure is a graph. Graphs are a particular set of figures that display quantitative relationships between variables. Some of the most common graphs include bar charts, frequency histograms, pie charts, scatter plots, and line graphs, each of which displays trends or relationships within and among datasets in a different way. You’ll need to carefully choose the best graph for your data and the relationship that you want to show. More details about some common graph types are provided below. Some good advice regarding the construction of graphs is to keep it simple. Remember that the main objective of your graph is communication. If your viewer is unable to visually decode your graph, then you have failed to communicate the information contained within it.

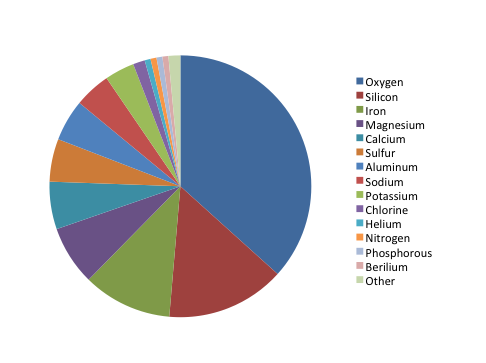

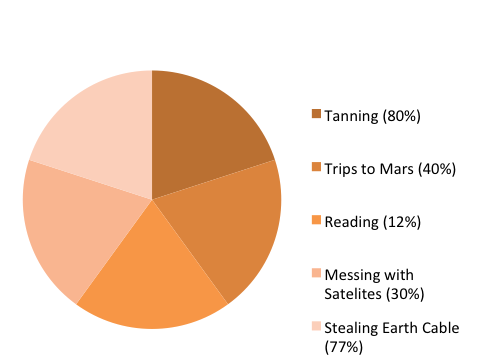

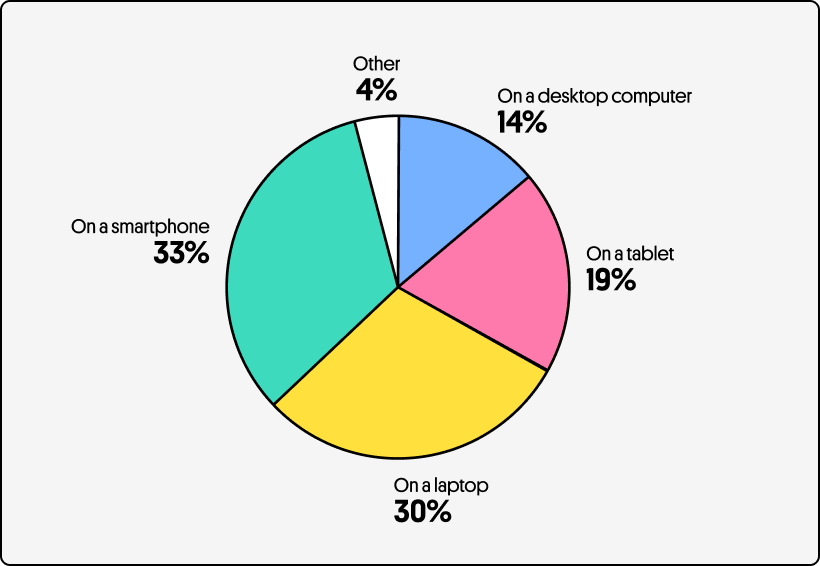

Pie charts are used to show relative proportions, specifically the relationship of a number of parts to the whole. Use pie charts only when the parts of the pie are mutually exclusive categories and the sum of parts adds up to a meaningful whole (100% of something). Pie charts are good at showing “big picture” relationships (i.e. some categories make up “a lot” or “a little” of the whole thing). However, if you want your reader to discern fine distinctions within your data, the pie chart is not for you. Humans are not very good at making comparisons based on angles. We are much better at comparing length, so try a bar chart as an alternative way to show relative proportions. Additionally, pie charts with lots of little slices or slices of very different sizes are difficult to read, so limit yours to 5-7 categories.

The chart shows the relative proportion of fifteen elements in Martian soil, listed in order from “most” to “least”: oxygen, silicon, iron, magnesium, calcium, sulfur, aluminum, sodium, potassium, chlorine, helium, nitrogen, phosphorus, beryllium, and other. Oxygen makes up about ⅓ of the composition, while silicon and iron together make up about ¼. The remaining slices make up smaller proportions, but the percentages aren’t listed in the key and are difficult to estimate. It is also hard to distinguish fifteen colors when comparing the pie chart to the color coded key.

The chart shows the relative proportion of five leisure activities of Venusian teenagers (tanning, trips to Mars, reading, messing with satellites, and stealing Earth cable). Although each of the five slices are about the same size (roughly 20% of the total), the percentage of Venusian teenagers engaging in each activity varies widely (tanning: 80%, trips to Mars: 40%, reading: 12%, messing with satellites: 30%, stealing Earth cable: 77%). Therefore, there is a mismatch between the labels and the actual proportion represented by each activity (in other words, if reading represents 12% of the total, its slice should take up 12% of the pie chart area), which makes the representation inaccurate. In addition, the labels for the five slices add up to 239% (rather than 100%), which makes it impossible to accurately represent this dataset using a pie chart.

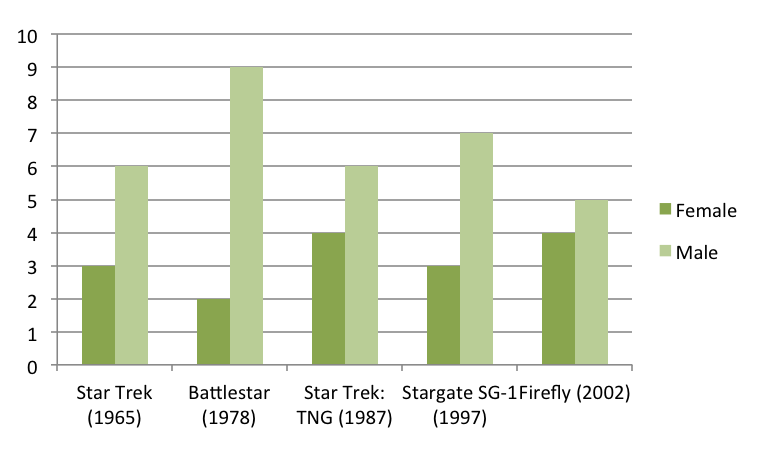

Bar graphs are also used to display proportions. In particular, they are useful for showing the relationship between independent and dependent variables, where the independent variables are discrete (often nominal) categories. Some examples are occupation, gender, and species. Bar graphs can be vertical or horizontal. In a vertical bar graph the independent variable is shown on the x axis (left to right) and the dependent variable on the y axis (up and down). In a horizontal one, the dependent variable will be shown on the horizontal (x) axis, the independent on the vertical (y) axis. The scale and origin of the graph should be meaningful. If the dependent (numeric) variable has a natural zero point, it is commonly used as a point of origin for the bar chart. However, zero is not always the best choice. You should experiment with both origin and scale to best show the relevant trends in your data without misleading the viewer in terms of the strength or extent of those trends.

The graph shows the number of male and female spaceship crew members for five different popular television series: Star Trek (1965), Battlestar (1978), Star Trek: TNG (1987), Stargate SG-1 (1997), and Firefly (2002). Because the television series are arranged chronologically on the x-axis, the graph can also be used to look for trends in these numbers over time.

Although the number of crew members for each show is similar (ranging from 9 to 11), the proportion of female and male crew members varies. Star Trek has half as many female crew members as male crew members (3 and 6, respectively), Battlestar has fewer than one-fourth as many female crew members as male crew members (2 and 9, respectively), Star Trek: TNG has four female crew members and six male crew members, Stargate SG-1 has less than one-half as many female crew members as male crew members (3 and 7, respectively), and Firefly has four female and five male crew members.

Frequency histograms/distributions

Frequency histograms are a special type of bar graph that show the relationship between independent and dependent variables, where the independent variable is continuous, rather than discrete. This means that each bar represents a range of values, rather than a single observation. The dependent variables in a histogram are always numeric, but may be absolute (counts) or relative (percentages). Frequency histograms are good for describing populations—examples include the distribution of exam scores for students in a class or the age distribution of the people living in Chapel Hill. You can experiment with bar ranges (also known as “bins”) to achieve the best level of detail, but each range or bin should be of uniform width and clearly labeled.

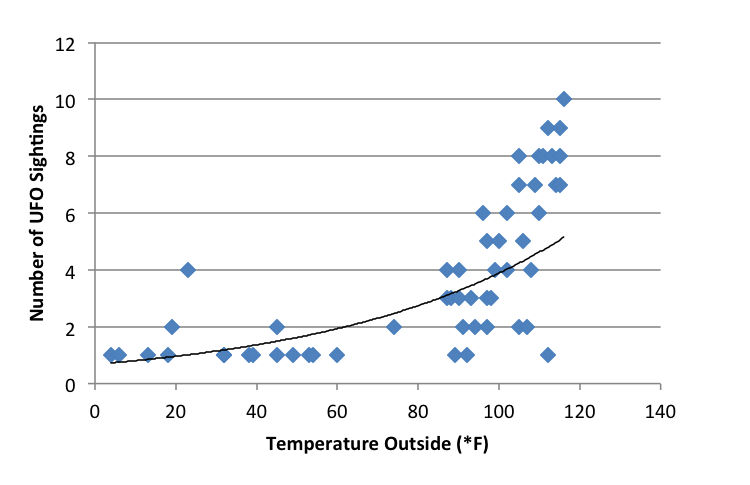

XY scatter plots

Scatter plots are another way to illustrate the relationship between two variables. In this case, data are displayed as points in an x,y coordinate system, where each point represents one observation along two axes of variation. Often, scatter plots are used to illustrate correlation between two variables—as one variable increases, the other increases (positive correlation) or decreases (negative correlation). However, correlation does not necessarily imply that changes in one variable cause changes in the other. For instance, a third, unplotted variable may be causing both. In other words, scatter plots can be used to graph one independent and one dependent variable, or they can be used to plot two independent variables. In cases where one variable is dependent on another (for example, height depends partly on age), plot the independent variable on the horizontal (x) axis, and the dependent variable on the vertical (y) axis. In addition to correlation (a linear relationship), scatter plots can be used to plot non-linear relationships between variables.

The scatter plot shows the relationship between temperature (x-axis, independent variable) and the number of UFO sightings (y-axis, dependent variable) for 53 separate data points. The temperature ranges from about 0°F and 120°F, and the number of UFO sightings ranges from 1 to 10. The plot shows a low number of UFO sightings (ranging from 1 to 4) at temperatures below 80°F and a much wider range of the number of sightings (from 1 to 10) at temperatures above 80°F. It appears that the number of sightings tends to increase as temperature increases, though there are many cases where only a few sightings occur at high temperatures.

XY line graphs

Line graphs are similar to scatter plots in that they display data along two axes of variation. Line graphs, however, plot a series of related values that depict a change in one variable as a function of another, for example, world population (dependent) over time (independent). Individual data points are joined by a line, drawing the viewer’s attention to local change between adjacent points, as well as to larger trends in the data. Line graphs are similar to bar graphs, but are better at showing the rate of change between two points. Line graphs can also be used to compare multiple dependent variables by plotting multiple lines on the same graph.

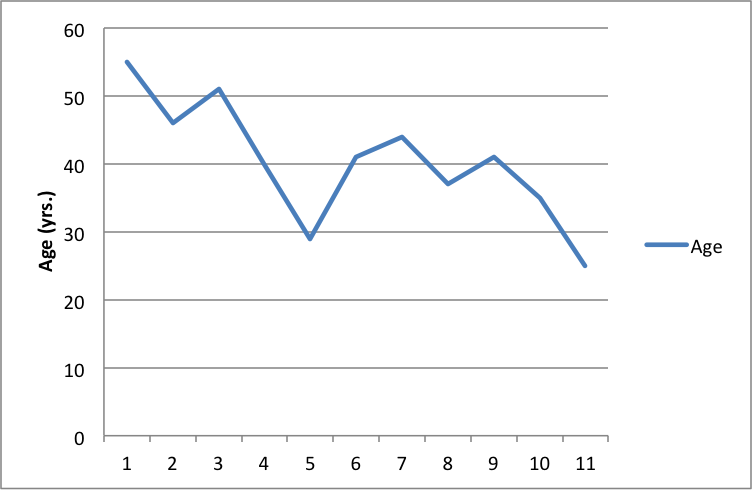

Example of an XY line graph:

The line graph shows the age (in years) of the actor of each Doctor Who regeneration for the first through the eleventh regeneration. The ages range from a maximum of about 55 in the first regeneration to a minimum of about 25 in the eleventh regeneration. There is a downward trend in the age of the actors over the course of the eleven regenerations.

General tips for graphs

Strive for simplicity. Your data will be complex. Don’t be tempted to convey the complexity of your data in graphical form. Your job (and the job of your graph) is to communicate the most important thing about the data. Think of graphs like you think of paragraphs—if you have several important things to say about your data, make several graphs, each of which highlights one important point you want to make.

Strive for clarity. Make sure that your data are portrayed in a way that is visually clear. Make sure that you have explained the elements of the graph clearly. Consider your audience. Will your reader be familiar with the type of figure you are using (such as a boxplot)? If not, or if you’re not sure, you may need to explain boxplot conventions in the text. Avoid “chartjunk.” Superfluous elements just make graphs visually confusing. Your reader does not want to spend 15 minutes figuring out the point of your graph.

Strive for accuracy. Carefully check your graph for errors. Even a simple graphical error can change the meaning and interpretation of the data. Use graphs responsibly. Don’t manipulate the data so that it looks like it’s saying something it’s not—savvy viewers will see through this ruse, and you will come off as incompetent at best and dishonest at worst.

How should tables and figures interact with text?

Placement of figures and tables within the text is discipline-specific. In manuscripts (such as lab reports and drafts) it is conventional to put tables and figures on separate pages from the text, as near as possible to the place where you first refer to it. You can also put all the figures and tables at the end of the paper to avoid breaking up the text. Figures and tables may also be embedded in the text, as long as the text itself isn’t broken up into small chunks. Complex raw data is conventionally presented in an appendix. Be sure to check on conventions for the placement of figures and tables in your discipline.

You can use text to guide the reader in interpreting the information included in a figure, table, or graph—tell the reader what the figure or table conveys and why it was important to include it.

When referring to tables and graphs from within the text, you can use:

- Clauses beginning with “as”: “As shown in Table 1, …”

- Passive voice: “Results are shown in Table 1.”

- Active voice (if appropriate for your discipline): “Table 1 shows that …”

- Parentheses: “Each sample tested positive for three nutrients (Table 1).”

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

American Psychological Association. 2010. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association . 6th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Bates College. 2012. “ Almost everything you wanted to know about making tables and figures.” How to Write a Paper in Scientific Journal Style and Format , January 11, 2012. http://abacus.bates.edu/~ganderso/biology/resources/writing/HTWtablefigs.html.

Cleveland, William S. 1994. The Elements of Graphing Data , 2nd ed. Summit, NJ: Hobart Press..

Council of Science Editors. 2014. Scientific Style and Format: The CSE Manual for Authors, Editors, and Publishers , 8th ed. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press.

University of Chicago Press. 2017. The Chicago Manual of Style , 17th ed. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Grammar check | Essay checker | Writing checker

December 22, 2018

Writing about Charts, Graphs, and Diagrams

by Nicholas Walker , under IELTS and TOEFL

Make sure to organize your IELTS Task 1 essay so that the reader can navigate it easily.

Step 1: Give a clear overview of what the figure is about, showing that you understand the main message it conveys.

Step 2: Describe the data in a systematic way (left to right, top to bottom, biggest to smallest) using numbers and words from the figure.

Step 3: Compare significant elements of the figure, mentioning any trends or changes in the past, extrapolating for the future if you can.

Useful chart, graph, and diagram vocabulary

Some words are likely to appear in a discussion of a chart, graph, or diagram. Use the target structure checker with the following list of common chart, graph, and diagram vocabulary to see if you are using the vocabulary your readers (the examiners) are expecting to see.

above, according to, apparent, are compared, are presented, bar graph, below, can be seen, chart, climbed, comparable, compares, considerable, considerably, decline, decrease, demonstrates, detailed, details, difference, dipped, diving sharply, downward, dramatic, dropped off, evident, falls, fell, fluctuation, fluctuations, gap, gradual, graph, greater, grew, grows, high, higher, highlighted, highlights, highs, histogram, illustrated, illustrates, increase, indicates, jump, leads, led, level, leveled, levelled, leveling, levelling, levels, lists, low, lower, lows, moderate, narrowed, note, number, observe, peak, peaks, period, photo, pie chart, pinpoints, plummeted, presents, proves, rapid climb, rates of, reports, reveals, remained, remains, rise, rises, rose, shown, shows, significant, slid, slight, steady, summarizes, results, value of, to every, to the left, to the right, total, trend, upward, we can see, widened, widening, widens

Want more like this?

Get new posts by email, recent posts.

- ConverSolo to Provide AI Language Learning Tools to Quebec Colleges and University– A First of its Kind AI Application in Higher Learning

- Virtual Writing Tutor Membership Plan Options

- Automated Essay Scoring Moodle Plugin

- 30 conversation questions to ask a traveler or a voice-enabled chatbot

- Inflation for ESL students

- Improve Writing

- What’s my English level?

- Automatically Scored Emails

- ESL Strategies: Flashcards

- Applied Linguistics at Concordia University

Enjoy this blog? Please spread the word :)

- A Beginner’s Guide to IELTS

- Common Grammar Mistakes [for IELTS Writing Candidates]

Writing Correction Service

- Free IELTS Resources

- Practice Speaking Test

Select Page

How to Describe a Bar Chart [IELTS Writing Task 1]

Posted by David S. Wills | Apr 13, 2020 | IELTS Tips , Writing | 5

There are various kinds of diagrams and charts that you may be asked to describe in the IELTS writing test, and one of those is the bar chart . In today’s lesson, I want to share some important advice that can help you improve your writing performance in your next IELTS test.

Describing data for task 1 of the IELTS writing exam is quite difficult and it will vary according to what you actually see. In other words, it is hard to simply teach some language for describing bar charts… Instead, your language will vary according to what the bar chart shows.

However, in this article I am going to break the process down and show you some examples so that you can understand it fully. At the end, I will give you a sample band 9 answer for a really difficult bar chart about people’s weight.

What are Bar Charts?

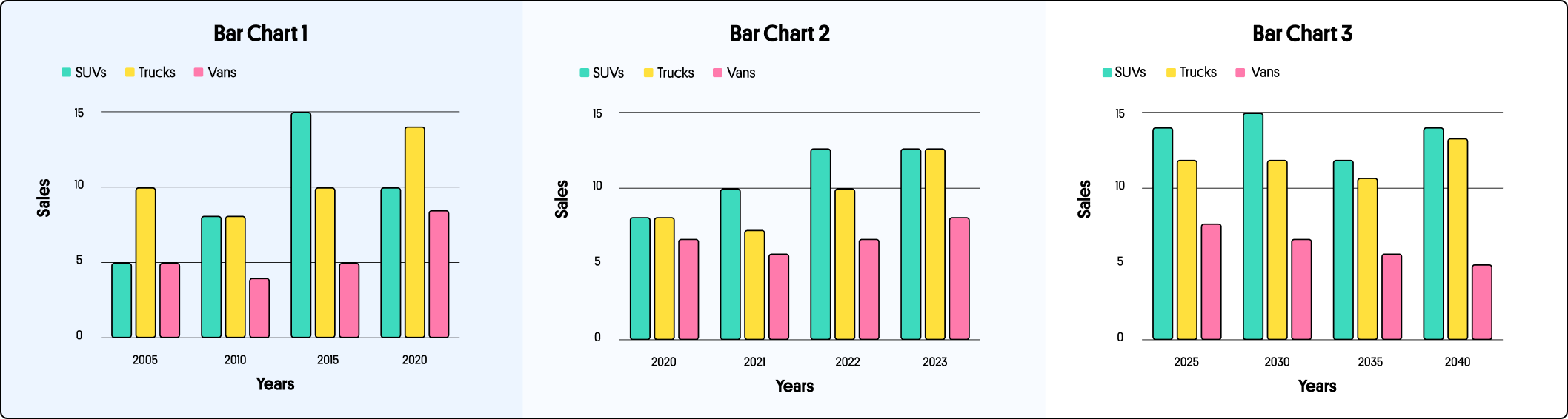

First of all, let’s start with the most basic question. You can feel free to skip this if you are already totally familiar with it. 😁 What is a bar chart? Basically, it is a visual representation of data using bars, like these:

Bar charts are used to show the difference between volumes or quantities of things because it is easy for the human eye to interpret. Let’s take a look at this example bar chart. I just found it on Google and will use it because it is simple. This is not a real IELTS chart. 🤪

You can easily see what this means. The most common excuse is “I forgot to set my alarm” and the least common is “It was still too dark; I thought it was still night-time.”

That is the purpose of a bar chart. It shows data in a way that is really easy for people to understand. As such, you may encounter it in your IELTS test. In that case, you will have to pick out the most important data and describe it.

Bar Charts for IELTS Writing

As we have seen, a bar chart is just another way of expressing data. For task 1 of the IELTS writing test, you may be asked to write about a bar chart. You will have to write more than 150 words and it is recommended that you do this in 20 minutes or less. (You will have a total of 1 hour for 2 tasks.)

It is important to note that you do not have to describe everything in the chart . Part of the task is picking out and describing only the relevant details. That usually means:

- The highest

- Major differences

- Anything interesting

What does that mean? This is very subjective, and so it is certainly open to debate. Let’s look at an example in order to understand it better:

In this bar chart, our eyes are naturally drawn towards the highest and lowest figures. The highest was in Sweden in 2012 and the lowest was in Finland in 2012. Therefore, both the highest and lowest figures occurred in the same year. That’s interesting!😅

Another interesting factor is that, in every year except one, Sweden had a higher divorce rate than Finland. It was only in 2015 that Finland’s divorce rate was higher than Sweden’s.

The Process

When you need to describe a bar chart for IELTS, you should take the same basic process as for describing anything else:

- Take time to read the question carefully.

- Look at the data and make sure you understand it.

- Find important data to describe.

- Plan your essay structure.

- Write your essay carefully.

- Check your answer for mistakes.

If you follow this basic routine, you will have a good chance of providing a strong answer to the question.

Language for Describing Bar Charts

In the past, I have talked about the language required to describe the following IELTS writing task 1 assignments:

- Process diagram

Bar charts are a little different because the language you would use depends on what is being described and there is no common set language that you would use just to talk about bar charts in general.

In the previous example, we can see that the bar chart features changing data over time. In such cases, we can use relatively similar language to that which we used for line graphs. You could say, for example:

Divorce rates in Sweden peaked in 2012 at a little under 50%, but fell in each of the subsequent years.

However, you can see that in the first bar chart there was no progression of time, so you cannot use language that shows changes in data. This brings us to the next stage…

Common Problems in Describing Bar Charts for IELTS

I used to teach writing skills at a university in China, and one of the most common problems I would have was teaching my students to write about bar charts. They could describe line graphs really easily, but the problem was that they would use the same expressions and structures for bar charts, when in fact something different was needed. Let’s look at two example charts. These contain similar data but there is an essential difference:

You can see that the line graph talks about changing phone prices over time, whereas the bar chart shows the different prices of phones. These prices are all taken from the same point in time .

Therefore, in order to adequately describe these, you must show that you understand the data.

For the line graph, you can say:

The price of Phone A rose from £380 to £410 between December and January.

However, you cannot use this language for the bar chart:

INCORRECT: The price rose from £380 for Phone B to £410 for Phone C. CORRECT: Phone C cost £30 more than Phone B, which cost £380.

This may seem easy to some people, but it is an important distinction and a common mistake. You should practice often to make sure that you know the difference.

Task 1 Essay Structure

There is no single perfect essay structure for IELTS, but there are some that are better than others. For task 1, I generally recommend writing an essay like this:

| Introduction | Give overview of the data Describe the main trend |

| Main paragraph #1 | Describe the main set of data OR Describe the first group of data |

| Main paragraph #2 | Describe secondary set of data OR Describe the second group of data |

Let me explain what I mean by that.

It is really important to group your data appropriately. This can be quite difficult, so you should read this article first.

Essentially, you need to choose how to put groups of data together. Let’s take another example:

The chart below shows the total number of minutes (in billions) of telephone call in the UK, divided into three categories, from 1995-2002. Summarise the information by selecting a reporting the main features, and make comparisons where relevant.

For this sort of bar chart, you might choose to write two or three body paragraphs. Perhaps you would describe local fixed line phones first, then start a new paragraph for national and international ones, with another paragraph for mobiles.

Another way would be to break the data in half – one paragraph for 1995 to 1998 and another paragraph for 1999 to 2002.

There are lots of different ways. The only really important thing is that you make it clear to your reader why you have chosen to group the data this way. In other words, it must be logical .

Sample Answer

My answer to this question would look something like this:

| Introduction | Give overview of the data Describe the main trend |

| Main paragraph #1 | Describe local calls |

| Main paragraph #2 | Describe other 2 types of call |

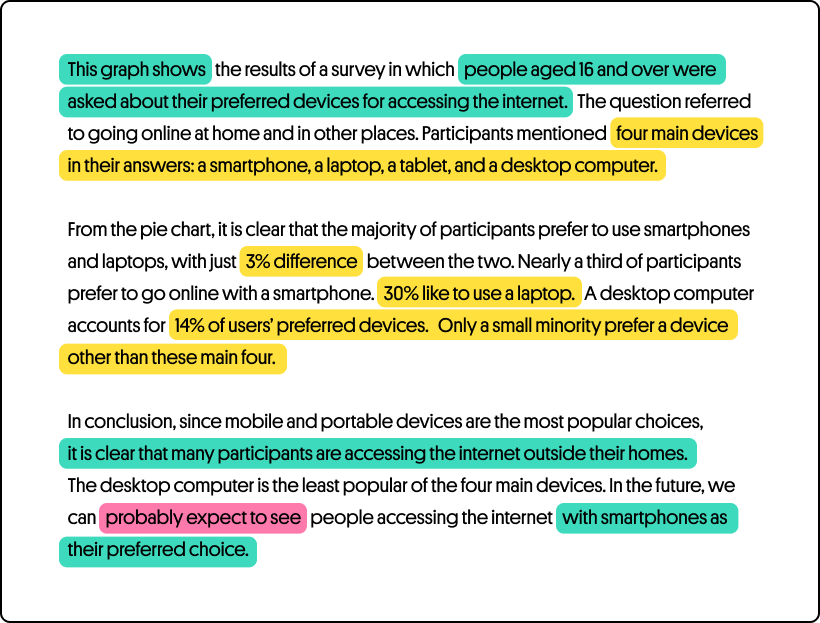

The bar chart shows the time spent on three different kinds of phone calls in the United Kingdom over a period of eight years, starting in 1995 and ending in 2002. Local calls were the most common type of phone call made during the entire period, although both national/international and mobile calls grew in popularity to narrow the gap between these three types of call by 2002. In 1995, local calls were by far the most common type of phone call in the UK, with more than 70 billion minutes recorded on this chart. This is about double the amount of time spent on national and international calls, and more than ten times as much as was spent on mobile phone calls. All three types of phone calls grew in popularity until 1999, after which local calls decreased year-on-year until they ended the period at around the same figure as they began it – 70 billion minutes. National and international calls grew steadily over the recorded eight years, from about half the popularity of local calls to only slightly less in 2002. Mobile phone calls, however, grew ten-fold from about four billion minutes to more than forty billion.

A Really Difficult Bar Chart

Finally, let’s look at a difficult bar chart in order to show how we can tackle challenging problems.

As you can see, the first problem is that there are two charts! Already, that will prove more difficult than describing just one chart.

Another issue is that these bars look strange. They are all the same size… Why? Well, these represent the population. Each one is 100%, with the colours making up the different weight categories. The total can never be more than 100% because that it is the full population.

Now, you should try to interpret the data. What are the main changes?

- In 1955, there are lots of people at an ideal weight and very few people are obese.

- In 2015, many older people are obese. Fewer people are at an ideal weight.

- The weight distribution was similar regardless of age in 1955, but in 2015 it is very different.

Once you have picked out the important data, you should figure out how to structure your answer. I will use this structure:

| Introduction | Give overview of the data Describe the main trend |

| Main paragraph #1 | Describe 1955 data |

| Main paragraph #2 | Describe 2015 data |

However, I will make sure that there are clear comparisons between the 1955 and 2015 data. It is not enough to describe them in isolation.

Language for Talking about Age and Weight

To be honest, the hardest part of this bar chart is not that data but the terminology around age and weight. You can see from the chart that were are looking at age groups and weight groups. Many native speakers find this really difficult to talk about.

When we talk about age and weight, we usually say some form of “to be” rather than “to have.” For example:

- INCORRECT: In 2015, a higher percentage of people had overweight or obesity than in any other group.

- CORRECT: In 2015, a higher percentage of people were overweight or obese than in any other group.

- INCORRECT: In both years, the people who were most likely to be an ideal weight had 20 to 29 years.

- CORRECT: In both years, the people who were most likely to be an ideal weight were aged 20 to 29 years.

You can see how I explained this to one of the students on my writing correction service :

There are also problems with grouping people according to age. We can just say “people in the ___ age group/category” but this becomes repetitive after a while, so we need to use different language.

Talking about age is difficult, especially when describing groups of people who fall into different age categories. One thing to know is that, when you say use numbers, it is a sort of adjective and thus you need a noun to follow it or else it is meaningless:

- The criminals arrested were all 16 to 25 years old.

- I saw a 15-year-old boy running away.

You can turn the “old” into a noun by adding an “-s”:

- There was an increase of 25% in the unemployment rate for 20-29-year olds.

You can also put “aged” before the numbers:

- Most of the recipients were aged 18-22.

Sample Band 9 Answer

Here is my description of the bar chart above:

There are two bar charts showing the distribution of weight categories for people living in Charlestown. The first one is from 1955 and the second is from 2015. It is clear that vast changes have occurred in people’s health during this sixty year period. In 1955, very few people were overweight or obese, and most were healthy or even underweight. In each of the age groups, at least half of people were classified as in the ideal weight range, but towards the ends of the spectrum – the youngest and the oldest people – there were more people who fell into the underweight bracket. Being overweight or obese was a problem primarily affecting middle aged people, but not the most elderly ones. However, this distribution had completely changed by 2015. Although some young adults and elderly people remained underweight, a very slim number in the middle of the age groups did. Being overweight had become increasingly common, and obesity had become a huge issue, affecting people more and more as they got older. For people aged fifty and older, more than half suffered from obesity, and very few fell into a healthy weight range.

Useful Language

I will excerpt some of the useful phrases that appeared in this answer so that you can see how I have managed to describe ages and weights:

- very few people were overweight or obese

- most were healthy or even underweight

- at least half of people were classified as in the ideal weight range

- people who fell into the underweight bracket

- Being overweight or obese was a problem

- elderly people remained underweight

- Being overweight had become increasingly common

- obesity had become a huge issue

- more than half suffered from obesity

- very few fell into a healthy weight range

This was a really difficult bar chart to describe, but using this language I have managed to do it accurately and comprehensively.

Improve your Writing

If you want to get better at IELTS writing, the only way to ensure constant progress is by having an expert give you feedback. Most of the writing correction services that you find online are rubbish. They are run by people do not speak much English or do not understand IELTS. My writing correction service is one of the few that is truly worthwhile. I can tell you all your problems and help you to fix them.

Here is my feedback to someone who wrote an essay about the Charlestown weight distribution bar charts:

Let me know in the comment section if you have any questions. 🙂

About The Author

David S. Wills

David S. Wills is the author of Scientologist! William S. Burroughs and the 'Weird Cult' and the founder/editor of Beatdom literary journal. He lives and works in rural Cambodia and loves to travel. He has worked as an IELTS tutor since 2010, has completed both TEFL and CELTA courses, and has a certificate from Cambridge for Teaching Writing. David has worked in many different countries, and for several years designed a writing course for the University of Worcester. In 2018, he wrote the popular IELTS handbook, Grammar for IELTS Writing and he has since written two other books about IELTS. His other IELTS website is called IELTS Teaching.

Related Posts

6 Tips to Boost Your IELTS Reading Score

October 30, 2016

IELTS History Vocabulary

December 6, 2021

Formal and Informal Vocabulary for IELTS

September 28, 2020

The Importance of Hedging Language

June 19, 2023

Hi, David. I noticed that you didn’t include any figures at all in your sample answer for the weight assessment. Is that acceptable? This is because I have seen some IETLS teacher who taught us to include most of important figures. Thank you.

The important thing about IELTS is that it is an English test, so you should use your language to describe the data. Most candidates attempt to cram lots of numbers in so that they can use fewer words. The fewer numbers you use, the better. Sure, you can have one or two, but if you are able to use words to describe trends, reflect important data, or make comparisons, then it is much better. If you read my essay carefully, you will notice that I said things like “at least half of people” rather than just repeating numbers. This is a good strategy, although you can certainly put in a few numbers if you want.

Hi David. Thank you for your explanation. I have a question! for describing a chart what verb tens we should use? It depends on something or it has a rule! Thank you.

It depends on the situation. Pay attention to any time frame that is given or the origin of the data. If none is given, then present simple is fine.

Asalam O Alakum David

Can we explain only things in overview except figures, percentage and time trend? I mean only what they have mentioned in the picture.

Secondly, in last 2 paragraphs only should we write those things which they have showed in the graph, chart or map in a simple way.\

Please, confirm me.

With regards

Leave a reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Download my IELTS Books

Recent Posts

- British vs American Spelling

- How to Improve your IELTS Writing Score

- Past Simple vs Past Perfect

- Complex Sentences

- How to Score Band 9 [Video Lesson]

Recent Comments

- Francisca on Adverb Clauses: A Comprehensive Guide

- Mariam on IELTS Writing Task 2: Two-Part Questions

- abdelhadi skini on Subordinating Conjunction vs Conjunctive Adverb

- David S. Wills on How to Describe Tables for IELTS Writing Task 1

- anonymous on How to Describe Tables for IELTS Writing Task 1

- Lesson Plans

- Model Essays

- TED Video Lessons

- Weekly Roundup

IELTS Writing Task 1: How to Describe a Bar Chart

If you’re not sure where to start, that’s ok! In this piece, we’ll provide an overview of how to describe a typical IELTS Writing Task 1 bar chart. We also suggest taking a look at resources in this piece on useful words for writing an IELTS Graph Essay

Table of Contents

What will you see in an ielts writing task 1 bar diagram, how to write about an ielts writing task 1 bar chart, how to describe an ielts writing task 1 bar chart, a final word on describing ielts academic bar charts.

A bar chart uses either horizontal or vertical bars to show comparisons among two or more categories. The bar chart has two main features: an X-axis and a Y-axis. One axis of the chart shows the specific categories being compared, and the other axis of the graph shows a given value (usually a percentage or a dollar amount).

To effectively write about an IELTS Writing Task 1 bar chart, follow these tips.

1. Start by Reading the Title

First and foremost, you should read the title. Often, I have students report on the essay in an inverted order because they didn’t read the bar chart title.

For example, an IELTS Writing Task 1 bar chart that I give students has the chart title “Expected City Visits by Country of Origin for 2018.” Yet I often get sample sentences back that read: “It is predicted that people from France will be the most likely to visit the United States in 2018.” The correct answer should be “It is predicted that Americans will choose France as their favorite city to visit in 2018.”

2. Look at the Time Frame

Look at the given period of time covered in the chart. Are you looking at a specific year? Are there multiple years being compared? Are we talking about something in the future? This will determine your grammar and style to some extent. For example, whether you need to use past tense language, the language of change, or future tense language when discussing your data.

3. Decide What You Are Comparing

What titles are given to the Y- and X-axis? This important information will form the language that you will use in the essay and the corresponding synonyms you should also use.

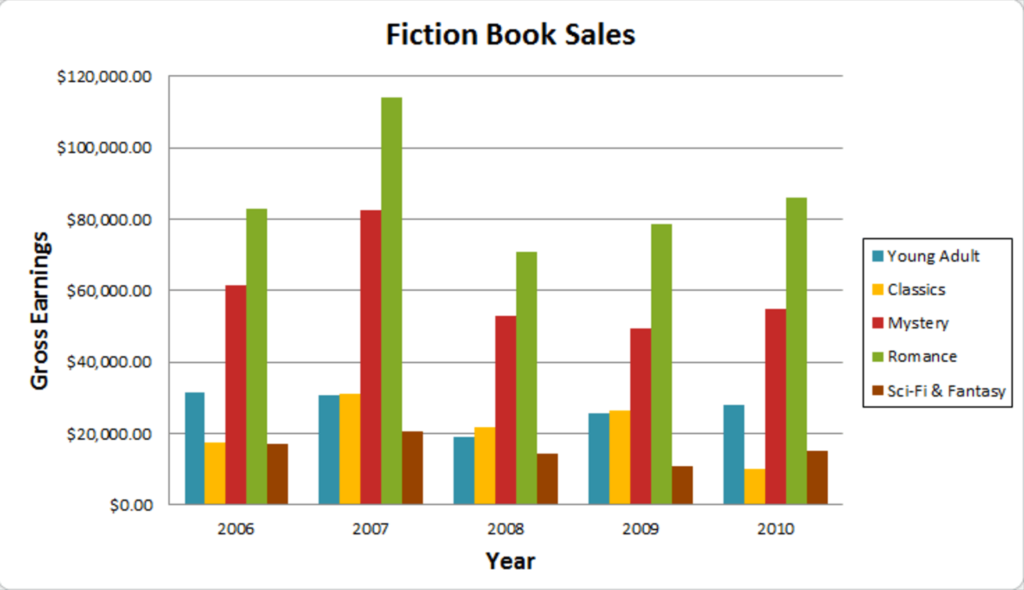

For example, the bar chart above compares the gross earnings of fiction books in five categories (Young Adults, Classics, Mystery, Romance and Sci-Fi and Fantasy) between 2006 and 2010. (Incidentally, this sentence is exactly what you would say for your introduction!)

Now that you know what the IELTS Writing Task 1 bar chart is about, these are the vital elements to include in your essay:

- Start with an introduction. The introduction explains what the chart is about, and gives an overview of the main points. Make sure you include one! Your introduction can be short, but it must be there. If you’ve spent time examining the chart this should be easy to write.

- Look for the key data and make sure that you are comparing and contrasting the data, NOT just listing the data from one section to the next. If you just write about what happened to X, what happened to Y, and what happened to Z, without showing any relationship between them, you will not get a high score.

To do this, you will need to look for similarities and differences when you first analyze the chart and you will need to decide what can logically be put together or not. This means that you don’t have to describe everything that you see in the bar chart, just the key points!

For example, for the above chart, you might say: It is interesting to note that Romance novels earned the most income each year between 2006 and 2010 with sales ranging from $70,000 to $115,000. In contrast, Sci Fi and Fantasy novels were the poorest revenue generators of the five categories earning only $20,000 at its highest point in 2007 and a mere $10,000 at its lowest point in 2009.

- Group the data together so that you have a well-organized and coherent answer. It is a good idea to divide your answer into two or three paragraphs so it is well organized. To do this, you should group similar ideas together into paragraphs or sections. Cohesion and coherence are key!

- Use a wide variety of sentence structures. Include complex sentences and simple sentences.

- It is equally important to use appropriate transitions between describing each data point.

- Always provide a short summary conclusion of what you included in your essay. One line is enough here. For example, It can be seen from the chart that overall, 2007 was the best year for book sales in all five categories.

- Finally, make sure that your word count is 150.

Overall, describing a an IELTS academic bar chart is a pretty straightforward task on your exam. Remember that in order to write well about a bar chart, you’ll want to be very clear on the relationship being expressed in it, so be careful not to rush past this step.

That said, you won’t want to spend more than about 20 minutes on IELTS writing task 1, so save most of your time for essay writing.

We hope we answered all of your IELTS Writing Task 1 bar diagram and bar chart questions! For more advice, we recommend taking a look at this IELTS writing task 1 vocab guide .

Good luck on your IELTS writing test!

Eliot Friesen-Meyers is the Senior Curriculum Manager for Magoosh IELTS and TOEFL. He attended Goshen College (B.A.), New York University (M.A.), and Harvard University (M.T.S.), gaining experience and skills in curriculum development, ESOL instruction, online teaching and learning, and IELTS and TOEFL test prep education. Eliot’s teaching career started with Literacy Americorps in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and later, taught ESL programs at Northeastern University, University of California-Irvine, and Harold Washington College. Eliot was also a speaker at the 2019 TESOL International Conference . With over 10 years of experience, he understands the challenges students face and loves helping them overcome those challenges. Come join Eliot on Youtube , Facebook , and Instagram . Recent blog posts Complete Guide to IELTS Writing Task 1 Complete Guide to IELTS Writing Task 2

View all posts

More from Magoosh

3 responses to “IELTS Writing Task 1: How to Describe a Bar Chart”

Thank you so much for your units and sharing.

We’re so glad we can help! 🙂

The bar chat illustrates the total amount of earning in sales of fiction books(young adults,classics,mystery,romance,sci-fi and fantasy) between 2096 and 2010. Overall,the total amount of sales of earning in romance book has highest through out the give decades while sci-fi and fantasy books has lowest amount of sales. In 2097 romance book earings has raised more than 10000000 respectively and then decreased to 9ne third in 2008 about 70,000,00 whereas the last two decades 2009 and 2010 upsurge arround 79,999,99 and 35,000,00 while the total gross earnings in the mystery books in 2006 arround 60,000,00 and increased in 2006 arround 82,000,00 has highest constant more than 40,000,00 same in 2009. On other hand,the total amount earings in young adults and classic book in 2007 and 2009 remains same about 25,000,00 meanwhile in 2006 and 2019 young adults books gross earnings has highest about 15,000,00 and 14,000,00 classic downsurge arround 99,999,99 however from 2006 to 2019 sci-fi and fantasy books earings has lowest sales less than 20,000,00 approximately.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write an essay outline | Guidelines & examples

How to Write an Essay Outline | Guidelines & Examples

Published on August 14, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

An essay outline is a way of planning the structure of your essay before you start writing. It involves writing quick summary sentences or phrases for every point you will cover in each paragraph , giving you a picture of how your argument will unfold.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Organizing your material, presentation of the outline, examples of essay outlines, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about essay outlines.

At the stage where you’re writing an essay outline, your ideas are probably still not fully formed. You should know your topic and have already done some preliminary research to find relevant sources , but now you need to shape your ideas into a structured argument.

Creating categories

Look over any information, quotes and ideas you’ve noted down from your research and consider the central point you want to make in the essay—this will be the basis of your thesis statement . Once you have an idea of your overall argument, you can begin to organize your material in a way that serves that argument.

Try to arrange your material into categories related to different aspects of your argument. If you’re writing about a literary text, you might group your ideas into themes; in a history essay, it might be several key trends or turning points from the period you’re discussing.

Three main themes or subjects is a common structure for essays. Depending on the length of the essay, you could split the themes into three body paragraphs, or three longer sections with several paragraphs covering each theme.

As you create the outline, look critically at your categories and points: Are any of them irrelevant or redundant? Make sure every topic you cover is clearly related to your thesis statement.

Order of information

When you have your material organized into several categories, consider what order they should appear in.

Your essay will always begin and end with an introduction and conclusion , but the organization of the body is up to you.

Consider these questions to order your material:

- Is there an obvious starting point for your argument?

- Is there one subject that provides an easy transition into another?

- Do some points need to be set up by discussing other points first?

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Within each paragraph, you’ll discuss a single idea related to your overall topic or argument, using several points of evidence or analysis to do so.

In your outline, you present these points as a few short numbered sentences or phrases.They can be split into sub-points when more detail is needed.

The template below shows how you might structure an outline for a five-paragraph essay.

- Thesis statement

- First piece of evidence

- Second piece of evidence

- Summary/synthesis

- Importance of topic

- Strong closing statement

You can choose whether to write your outline in full sentences or short phrases. Be consistent in your choice; don’t randomly write some points as full sentences and others as short phrases.

Examples of outlines for different types of essays are presented below: an argumentative, expository, and literary analysis essay.

Argumentative essay outline

This outline is for a short argumentative essay evaluating the internet’s impact on education. It uses short phrases to summarize each point.

Its body is split into three paragraphs, each presenting arguments about a different aspect of the internet’s effects on education.

- Importance of the internet

- Concerns about internet use

- Thesis statement: Internet use a net positive

- Data exploring this effect

- Analysis indicating it is overstated

- Students’ reading levels over time

- Why this data is questionable

- Video media

- Interactive media

- Speed and simplicity of online research

- Questions about reliability (transitioning into next topic)

- Evidence indicating its ubiquity

- Claims that it discourages engagement with academic writing

- Evidence that Wikipedia warns students not to cite it

- Argument that it introduces students to citation

- Summary of key points

- Value of digital education for students

- Need for optimism to embrace advantages of the internet

Expository essay outline

This is the outline for an expository essay describing how the invention of the printing press affected life and politics in Europe.

The paragraphs are still summarized in short phrases here, but individual points are described with full sentences.

- Claim that the printing press marks the end of the Middle Ages.

- Provide background on the low levels of literacy before the printing press.

- Present the thesis statement: The invention of the printing press increased circulation of information in Europe, paving the way for the Reformation.

- Discuss the very high levels of illiteracy in medieval Europe.

- Describe how literacy and thus knowledge and education were mainly the domain of religious and political elites.

- Indicate how this discouraged political and religious change.

- Describe the invention of the printing press in 1440 by Johannes Gutenberg.

- Show the implications of the new technology for book production.

- Describe the rapid spread of the technology and the printing of the Gutenberg Bible.

- Link to the Reformation.

- Discuss the trend for translating the Bible into vernacular languages during the years following the printing press’s invention.

- Describe Luther’s own translation of the Bible during the Reformation.

- Sketch out the large-scale effects the Reformation would have on religion and politics.

- Summarize the history described.

- Stress the significance of the printing press to the events of this period.

Literary analysis essay outline

The literary analysis essay outlined below discusses the role of theater in Jane Austen’s novel Mansfield Park .

The body of the essay is divided into three different themes, each of which is explored through examples from the book.

- Describe the theatricality of Austen’s works

- Outline the role theater plays in Mansfield Park

- Introduce the research question : How does Austen use theater to express the characters’ morality in Mansfield Park ?

- Discuss Austen’s depiction of the performance at the end of the first volume

- Discuss how Sir Bertram reacts to the acting scheme

- Introduce Austen’s use of stage direction–like details during dialogue

- Explore how these are deployed to show the characters’ self-absorption

- Discuss Austen’s description of Maria and Julia’s relationship as polite but affectionless

- Compare Mrs. Norris’s self-conceit as charitable despite her idleness

- Summarize the three themes: The acting scheme, stage directions, and the performance of morals

- Answer the research question

- Indicate areas for further study

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

You will sometimes be asked to hand in an essay outline before you start writing your essay . Your supervisor wants to see that you have a clear idea of your structure so that writing will go smoothly.

Even when you do not have to hand it in, writing an essay outline is an important part of the writing process . It’s a good idea to write one (as informally as you like) to clarify your structure for yourself whenever you are working on an essay.

If you have to hand in your essay outline , you may be given specific guidelines stating whether you have to use full sentences. If you’re not sure, ask your supervisor.

When writing an essay outline for yourself, the choice is yours. Some students find it helpful to write out their ideas in full sentences, while others prefer to summarize them in short phrases.

You should try to follow your outline as you write your essay . However, if your ideas change or it becomes clear that your structure could be better, it’s okay to depart from your essay outline . Just make sure you know why you’re doing so.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Write an Essay Outline | Guidelines & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved June 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/essay-outline/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to create a structured research paper outline | example, a step-by-step guide to the writing process, how to write an argumentative essay | examples & tips, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

IELTS Advantage

IELTS Preparation Courses

IELTS Bar Chart Sample Essay

Static or Dynamic?

Before writing an IELTS task 1 bar chart or line graph answer it is important that we analyse the question correctly. Taking a few minutes to do this will help us write a clear answer that fully responds to the question. Just what the examiner wants us to do.

The first thing we need to do is decide if the bar chart is static or dynamic. Static means that the data comes from one point in time. Dynamic means the data comes from more than one point in time.

Whether a chart is static or dynamic will affect the information we choose to include in our answer and the kind of language (tense, grammar etc.) we use.

If it is dynamic we will have to compare the different times and comment on the general trends over the time period.

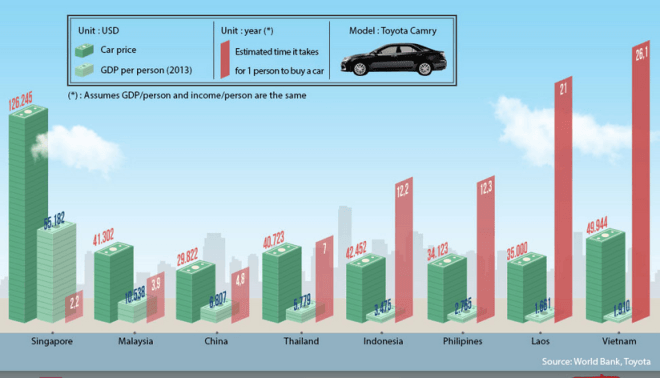

If it is static we will have to compare the different variables, in this case countries, car price, GDP and time it takes for one person to buy a car.

Main Features

Every IELTS academic task 1 question asks us to ‘select and report the main features’.

This means that we have to not only pick the most significant information from the graph and include it in our essay, but also decide which information is not important and should therefore not be included in our essay. One of the biggest mistakes you can make in task 1 is including all the information you see.

So which information should you choose?

You should look for:

- highest/lowest values

- biggest differences

- similarities

- significant exceptions

- anything else that really stands out

There are 3 main features in this graph

1) It takes over 26 years for a Vietnamese person to buy a car.

2) Vietnam has the second highest average costs but the second lowest wages.

3) Cost of a car in Singapore is nearly 3 times the next most expensive.

I advise my students to follow a basic four paragraph structure for these kinds of questions.

Paragraph 1

Paraphrase the question using synonyms.

Paragraph 2

Provide an overview of the main features. No need to include any data in this paragraph, just tell the examiner what is happening in general terms. If you had to describe the main features in two sentences, what would you say?

Paragraph 3

This is where we get more specific and use data. Take 2 of the main features (from your overview) and describe them in detail using data from the chart.

Paragraph 4

Simply do the same thing as you did in paragraph 3, but with two other main features (from your overview).

Sample Answer

The graph compares the GDP per capita, cost of a Toyota Camry and approximate length of time it takes for 1 citizen to purchase that mode of transport in eight Asian countries.

Despite having the second lowest average yearly income, it costs more to buy this car in Vietnam than in all but one other Asian nation. It also takes significantly longer for a standard person to buy an automobile in Vietnam than in any other state in Asia. On the other end of the scale, Singaporeans have to pay nearly three times more for their cars than the Vietnamese and it takes them the least amount of time to afford a motor vehicle.

It costs $49,944 to buy a Toyota Camry in Vietnam, but this dwarfs the average yearly income per person at just $1,910. It would therefore take a normal man or woman 26.1 years to save up for that particular car.

This is in contrast to Singapore where it costs $126,245 for that model of motorcar, however the average salary is much greater at $55,182. This means that it generally takes just over 2 years for a typical individual from Singapore to acquire this vehicle.

(200 words) Band 9.

It should be noted that this is not a real IELTS task 1 question. This is just a chart that I saw on the internet, but it allowed me to make a very important point- you don’t have to mention everything on the graph. I only talked about 2 out of the 8 countries and I still wrote 200 words and answer the question fully. The key is finding the most significant data and not talking about anything else. Don’t worry, you won’t lose marks for not talking about everything, quite the opposite.

This graph is also good for demonstrating how important it is to vary your vocabulary. There were four words that could have been overused in this essay- car, average, country and people. Instead of repeating them over and over again I used synonyms to show the examiner I have a wide vocabulary and gain extra marks. Here are the synonyms:

Car- Toyota Camry- automobile- vehicle- motor vehicle- motorcar

Average- approximate- normal- typical- standard

Country- countries- nation- state

People- citizen- man or woman- individual

Next time you see a chart or graph in a newspaper, in a textbook or on the internet, think about what the main features are and what common words would you have to vary with synonyms.

I hope you have found these tips useful. If you have any questions, let me know below.

For more band 9 sample essays check out our task 1 sample essay page.

About Christopher Pell

My name is Christopher Pell and I'm the Managing Director of IELTS Advantage.

I started IELTS Advantage as a simple blog to help 16 students in my class. Several years later, I am very humbled that my VIP Course has been able to help thousands of people around the world to score a Band 7+ in their IELTS tests.

If you need my help with your IELTS preparation, you can send me an email using the contact us page.

Describing graphs, charts, diagrams and tables for band 9 in IELTS writing + Best structures and useful vocabulary

The ability to describe graphs, charts, diagrams, and tables is crucial for achieving a high score on the IELTS writing test. This skill demonstrates your proficiency in English and ability to analyze and communicate complex information clearly. This article provides a comprehensive guide on excelling in describing various types of graphs, charts, diagrams, and tables in IELTS writing.

Understanding the nuances of different types of visual data is the first step toward mastering their description. Each type of graph or chart presents unique challenges and opportunities for analysis. Here’s how to approach each one:

Line Graphs

Line graphs depict data points over time, illustrating trends, growth rates, declines, and periodic fluctuations. They can feature single or multiple lines to allow comparisons between different datasets over identical time periods, making them invaluable for showing changes and trends.

Answering Strategies

To excel in describing line graphs, consider the following strategies:

- Start with paraphrasing the information provided by the line graph in your introduction. This involves rewording the graph’s title and any accompanying descriptions to introduce the topic without directly copying the text.