Why is it important to do a literature review in research?

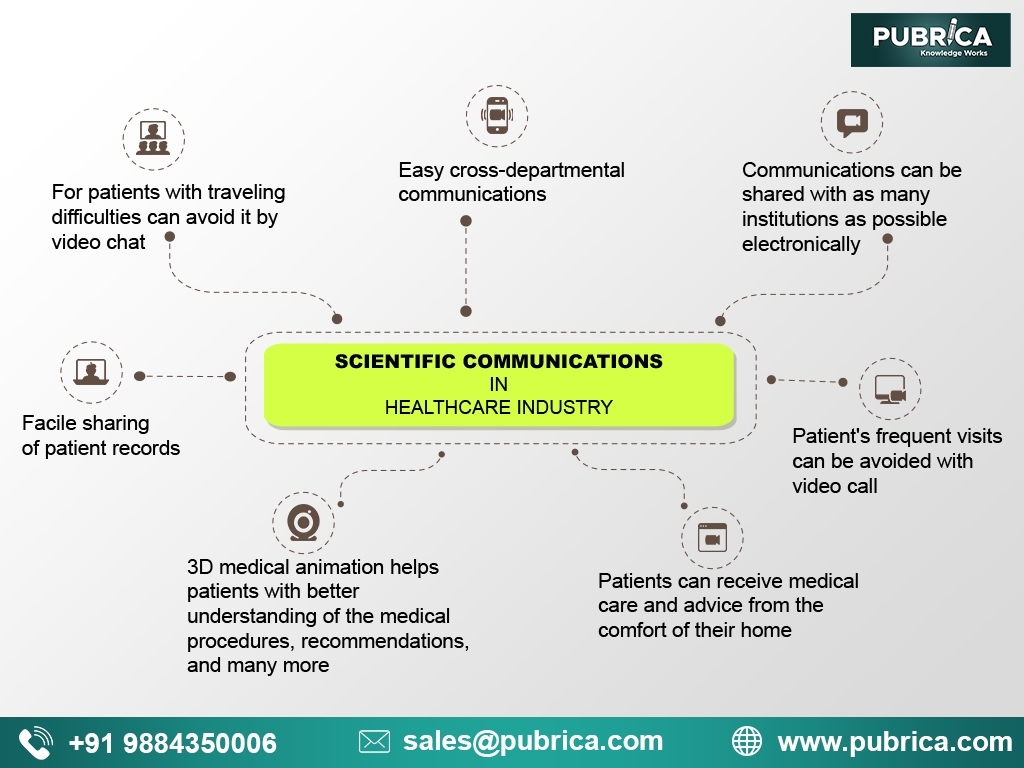

The importance of scientific communication in the healthcare industry

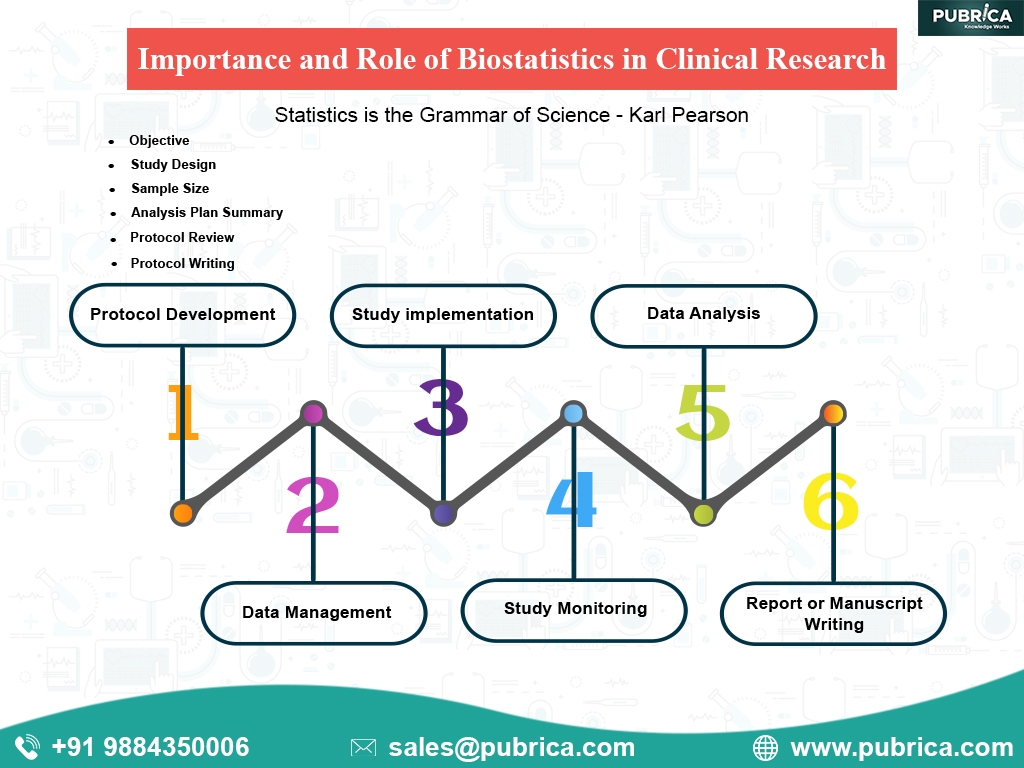

The Importance and Role of Biostatistics in Clinical Research

“A substantive, thorough, sophisticated literature review is a precondition for doing substantive, thorough, sophisticated research”. Boote and Baile 2005

Authors of manuscripts treat writing a literature review as a routine work or a mere formality. But a seasoned one knows the purpose and importance of a well-written literature review. Since it is one of the basic needs for researches at any level, they have to be done vigilantly. Only then the reader will know that the basics of research have not been neglected.

The aim of any literature review is to summarize and synthesize the arguments and ideas of existing knowledge in a particular field without adding any new contributions. Being built on existing knowledge they help the researcher to even turn the wheels of the topic of research. It is possible only with profound knowledge of what is wrong in the existing findings in detail to overpower them. For other researches, the literature review gives the direction to be headed for its success.

The common perception of literature review and reality:

As per the common belief, literature reviews are only a summary of the sources related to the research. And many authors of scientific manuscripts believe that they are only surveys of what are the researches are done on the chosen topic. But on the contrary, it uses published information from pertinent and relevant sources like

- Scholarly books

- Scientific papers

- Latest studies in the field

- Established school of thoughts

- Relevant articles from renowned scientific journals

and many more for a field of study or theory or a particular problem to do the following:

- Summarize into a brief account of all information

- Synthesize the information by restructuring and reorganizing

- Critical evaluation of a concept or a school of thought or ideas

- Familiarize the authors to the extent of knowledge in the particular field

- Encapsulate

- Compare & contrast

By doing the above on the relevant information, it provides the reader of the scientific manuscript with the following for a better understanding of it:

- It establishes the authors’ in-depth understanding and knowledge of their field subject

- It gives the background of the research

- Portrays the scientific manuscript plan of examining the research result

- Illuminates on how the knowledge has changed within the field

- Highlights what has already been done in a particular field

- Information of the generally accepted facts, emerging and current state of the topic of research

- Identifies the research gap that is still unexplored or under-researched fields

- Demonstrates how the research fits within a larger field of study

- Provides an overview of the sources explored during the research of a particular topic

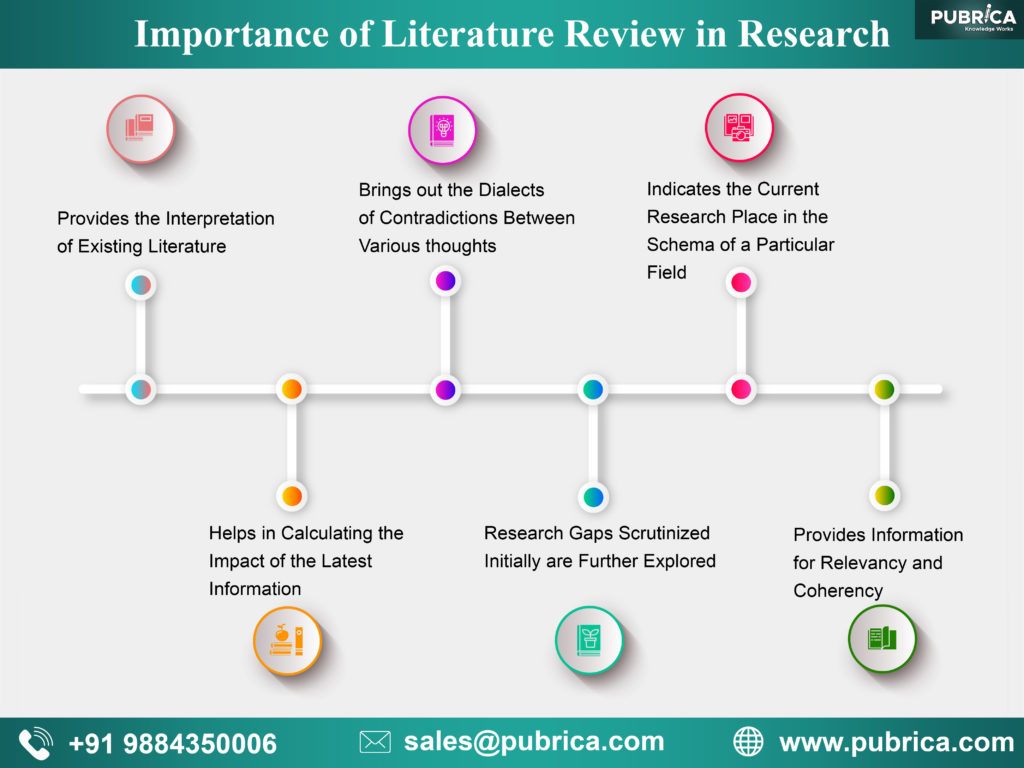

Importance of literature review in research:

The importance of literature review in scientific manuscripts can be condensed into an analytical feature to enable the multifold reach of its significance. It adds value to the legitimacy of the research in many ways:

- Provides the interpretation of existing literature in light of updated developments in the field to help in establishing the consistency in knowledge and relevancy of existing materials

- It helps in calculating the impact of the latest information in the field by mapping their progress of knowledge.

- It brings out the dialects of contradictions between various thoughts within the field to establish facts

- The research gaps scrutinized initially are further explored to establish the latest facts of theories to add value to the field

- Indicates the current research place in the schema of a particular field

- Provides information for relevancy and coherency to check the research

- Apart from elucidating the continuance of knowledge, it also points out areas that require further investigation and thus aid as a starting point of any future research

- Justifies the research and sets up the research question

- Sets up a theoretical framework comprising the concepts and theories of the research upon which its success can be judged

- Helps to adopt a more appropriate methodology for the research by examining the strengths and weaknesses of existing research in the same field

- Increases the significance of the results by comparing it with the existing literature

- Provides a point of reference by writing the findings in the scientific manuscript

- Helps to get the due credit from the audience for having done the fact-finding and fact-checking mission in the scientific manuscripts

- The more the reference of relevant sources of it could increase more of its trustworthiness with the readers

- Helps to prevent plagiarism by tailoring and uniquely tweaking the scientific manuscript not to repeat other’s original idea

- By preventing plagiarism , it saves the scientific manuscript from rejection and thus also saves a lot of time and money

- Helps to evaluate, condense and synthesize gist in the author’s own words to sharpen the research focus

- Helps to compare and contrast to show the originality and uniqueness of the research than that of the existing other researches

- Rationalizes the need for conducting the particular research in a specified field

- Helps to collect data accurately for allowing any new methodology of research than the existing ones

- Enables the readers of the manuscript to answer the following questions of its readers for its better chances for publication

- What do the researchers know?

- What do they not know?

- Is the scientific manuscript reliable and trustworthy?

- What are the knowledge gaps of the researcher?

22. It helps the readers to identify the following for further reading of the scientific manuscript:

- What has been already established, discredited and accepted in the particular field of research

- Areas of controversy and conflicts among different schools of thought

- Unsolved problems and issues in the connected field of research

- The emerging trends and approaches

- How the research extends, builds upon and leaves behind from the previous research

A profound literature review with many relevant sources of reference will enhance the chances of the scientific manuscript publication in renowned and reputed scientific journals .

References:

http://www.math.montana.edu/jobo/phdprep/phd6.pdf

journal Publishing services | Scientific Editing Services | Medical Writing Services | scientific research writing service | Scientific communication services

Related Topics:

Meta Analysis

Scientific Research Paper Writing

Medical Research Paper Writing

Scientific Communication in healthcare

pubrica academy

Related posts.

Statistical analyses of case-control studies

PUB - Selecting material (e.g. excipient, active pharmaceutical ingredient) for drug development

Selecting material (e.g. excipient, active pharmaceutical ingredient, packaging material) for drug development

PUB - Health Economics of Data Modeling

Health economics in clinical trials

Comments are closed.

News alert: UC Berkeley has announced its next university librarian

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Conducting a literature review: why do a literature review, why do a literature review.

- How To Find "The Literature"

- Found it -- Now What?

Besides the obvious reason for students -- because it is assigned! -- a literature review helps you explore the research that has come before you, to see how your research question has (or has not) already been addressed.

You identify:

- core research in the field

- experts in the subject area

- methodology you may want to use (or avoid)

- gaps in knowledge -- or where your research would fit in

It Also Helps You:

- Publish and share your findings

- Justify requests for grants and other funding

- Identify best practices to inform practice

- Set wider context for a program evaluation

- Compile information to support community organizing

Great brief overview, from NCSU

Want To Know More?

- Next: How To Find "The Literature" >>

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 1:10 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/litreview

Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jan 4, 2024 10:52 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

- What is a literature review?

- Steps in the Literature Review Process

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

What is a Literature Review?

A literature or narrative review is a comprehensive review and analysis of the published literature on a specific topic or research question. The literature that is reviewed contains: books, articles, academic articles, conference proceedings, association papers, and dissertations. It contains the most pertinent studies and points to important past and current research and practices. It provides background and context, and shows how your research will contribute to the field.

A literature review should:

- Provide a comprehensive and updated review of the literature;

- Explain why this review has taken place;

- Articulate a position or hypothesis;

- Acknowledge and account for conflicting and corroborating points of view

From S age Research Methods

Purpose of a Literature Review

A literature review can be written as an introduction to a study to:

- Demonstrate how a study fills a gap in research

- Compare a study with other research that's been done

Or it can be a separate work (a research article on its own) which:

- Organizes or describes a topic

- Describes variables within a particular issue/problem

Limitations of a Literature Review

Some of the limitations of a literature review are:

- It's a snapshot in time. Unlike other reviews, this one has beginning, a middle and an end. There may be future developments that could make your work less relevant.

- It may be too focused. Some niche studies may miss the bigger picture.

- It can be difficult to be comprehensive. There is no way to make sure all the literature on a topic was considered.

- It is easy to be biased if you stick to top tier journals. There may be other places where people are publishing exemplary research. Look to open access publications and conferences to reflect a more inclusive collection. Also, make sure to include opposing views (and not just supporting evidence).

Source: Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, June 2009, pp. 91–108. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

Meryl Brodsky : Communication and Information Studies

Hannah Chapman Tripp : Biology, Neuroscience

Carolyn Cunningham : Human Development & Family Sciences, Psychology, Sociology

Larayne Dallas : Engineering

Janelle Hedstrom : Special Education, Curriculum & Instruction, Ed Leadership & Policy

Susan Macicak : Linguistics

Imelda Vetter : Dell Medical School

For help in other subject areas, please see the guide to library specialists by subject .

Periodically, UT Libraries runs a workshop covering the basics and library support for literature reviews. While we try to offer these once per academic year, we find providing the recording to be helpful to community members who have missed the session. Following is the most recent recording of the workshop, Conducting a Literature Review. To view the recording, a UT login is required.

- October 26, 2022 recording

- Last Updated: Oct 26, 2022 2:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

Libraries | Research Guides

Literature reviews, what is a literature review, learning more about how to do a literature review.

- Planning the Review

- The Research Question

- Choosing Where to Search

- Organizing the Review

- Writing the Review

A literature review is a review and synthesis of existing research on a topic or research question. A literature review is meant to analyze the scholarly literature, make connections across writings and identify strengths, weaknesses, trends, and missing conversations. A literature review should address different aspects of a topic as it relates to your research question. A literature review goes beyond a description or summary of the literature you have read.

- Sage Research Methods Core Collection This link opens in a new window SAGE Research Methods supports research at all levels by providing material to guide users through every step of the research process. SAGE Research Methods is the ultimate methods library with more than 1000 books, reference works, journal articles, and instructional videos by world-leading academics from across the social sciences, including the largest collection of qualitative methods books available online from any scholarly publisher. – Publisher

- Next: Planning the Review >>

- Last Updated: Jan 17, 2024 10:05 AM

- URL: https://libguides.northwestern.edu/literaturereviews

- Research Process

Literature Review in Research Writing

- 4 minute read

- 422.9K views

Table of Contents

Research on research? If you find this idea rather peculiar, know that nowadays, with the huge amount of information produced daily all around the world, it is becoming more and more difficult to keep up to date with all of it. In addition to the sheer amount of research, there is also its origin. We are witnessing the economic and intellectual emergence of countries like China, Brazil, Turkey, and United Arab Emirates, for example, that are producing scholarly literature in their own languages. So, apart from the effort of gathering information, there must also be translators prepared to unify all of it in a single language to be the object of the literature survey. At Elsevier, our team of translators is ready to support researchers by delivering high-quality scientific translations , in several languages, to serve their research – no matter the topic.

What is a literature review?

A literature review is a study – or, more accurately, a survey – involving scholarly material, with the aim to discuss published information about a specific topic or research question. Therefore, to write a literature review, it is compulsory that you are a real expert in the object of study. The results and findings will be published and made available to the public, namely scientists working in the same area of research.

How to Write a Literature Review

First of all, don’t forget that writing a literature review is a great responsibility. It’s a document that is expected to be highly reliable, especially concerning its sources and findings. You have to feel intellectually comfortable in the area of study and highly proficient in the target language; misconceptions and errors do not have a place in a document as important as a literature review. In fact, you might want to consider text editing services, like those offered at Elsevier, to make sure your literature is following the highest standards of text quality. You want to make sure your literature review is memorable by its novelty and quality rather than language errors.

Writing a literature review requires expertise but also organization. We cannot teach you about your topic of research, but we can provide a few steps to guide you through conducting a literature review:

- Choose your topic or research question: It should not be too comprehensive or too limited. You have to complete your task within a feasible time frame.

- Set the scope: Define boundaries concerning the number of sources, time frame to be covered, geographical area, etc.

- Decide which databases you will use for your searches: In order to search the best viable sources for your literature review, use highly regarded, comprehensive databases to get a big picture of the literature related to your topic.

- Search, search, and search: Now you’ll start to investigate the research on your topic. It’s critical that you keep track of all the sources. Start by looking at research abstracts in detail to see if their respective studies relate to or are useful for your own work. Next, search for bibliographies and references that can help you broaden your list of resources. Choose the most relevant literature and remember to keep notes of their bibliographic references to be used later on.

- Review all the literature, appraising carefully it’s content: After reading the study’s abstract, pay attention to the rest of the content of the articles you deem the “most relevant.” Identify methodologies, the most important questions they address, if they are well-designed and executed, and if they are cited enough, etc.

If it’s the first time you’ve published a literature review, note that it is important to follow a special structure. Just like in a thesis, for example, it is expected that you have an introduction – giving the general idea of the central topic and organizational pattern – a body – which contains the actual discussion of the sources – and finally the conclusion or recommendations – where you bring forward whatever you have drawn from the reviewed literature. The conclusion may even suggest there are no agreeable findings and that the discussion should be continued.

Why are literature reviews important?

Literature reviews constantly feed new research, that constantly feeds literature reviews…and we could go on and on. The fact is, one acts like a force over the other and this is what makes science, as a global discipline, constantly develop and evolve. As a scientist, writing a literature review can be very beneficial to your career, and set you apart from the expert elite in your field of interest. But it also can be an overwhelming task, so don’t hesitate in contacting Elsevier for text editing services, either for profound edition or just a last revision. We guarantee the very highest standards. You can also save time by letting us suggest and make the necessary amendments to your manuscript, so that it fits the structural pattern of a literature review. Who knows how many worldwide researchers you will impact with your next perfectly written literature review.

Know more: How to Find a Gap in Research .

Language Editing Services by Elsevier Author Services:

What is a Research Gap

- Manuscript Preparation

Types of Scientific Articles

You may also like.

Descriptive Research Design and Its Myriad Uses

Five Common Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Biomedical Research Paper

Making Technical Writing in Environmental Engineering Accessible

To Err is Not Human: The Dangers of AI-assisted Academic Writing

When Data Speak, Listen: Importance of Data Collection and Analysis Methods

Choosing the Right Research Methodology: A Guide for Researchers

Why is data validation important in research?

Writing a good review article

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

- Become Involved |

- Give to the Library |

- Staff Directory |

- UNF Library

- Thomas G. Carpenter Library

Conducting a Literature Review

Benefits of conducting a literature review.

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Summary of the Process

- Additional Resources

- Literature Review Tutorial by American University Library

- The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It by University of Toronto

- Write a Literature Review by UC Santa Cruz University Library

While there might be many reasons for conducting a literature review, following are four key outcomes of doing the review.

Assessment of the current state of research on a topic . This is probably the most obvious value of the literature review. Once a researcher has determined an area to work with for a research project, a search of relevant information sources will help determine what is already known about the topic and how extensively the topic has already been researched.

Identification of the experts on a particular topic . One of the additional benefits derived from doing the literature review is that it will quickly reveal which researchers have written the most on a particular topic and are, therefore, probably the experts on the topic. Someone who has written twenty articles on a topic or on related topics is more than likely more knowledgeable than someone who has written a single article. This same writer will likely turn up as a reference in most of the other articles written on the same topic. From the number of articles written by the author and the number of times the writer has been cited by other authors, a researcher will be able to assume that the particular author is an expert in the area and, thus, a key resource for consultation in the current research to be undertaken.

Identification of key questions about a topic that need further research . In many cases a researcher may discover new angles that need further exploration by reviewing what has already been written on a topic. For example, research may suggest that listening to music while studying might lead to better retention of ideas, but the research might not have assessed whether a particular style of music is more beneficial than another. A researcher who is interested in pursuing this topic would then do well to follow up existing studies with a new study, based on previous research, that tries to identify which styles of music are most beneficial to retention.

Determination of methodologies used in past studies of the same or similar topics. It is often useful to review the types of studies that previous researchers have launched as a means of determining what approaches might be of most benefit in further developing a topic. By the same token, a review of previously conducted studies might lend itself to researchers determining a new angle for approaching research.

Upon completion of the literature review, a researcher should have a solid foundation of knowledge in the area and a good feel for the direction any new research should take. Should any additional questions arise during the course of the research, the researcher will know which experts to consult in order to quickly clear up those questions.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Aug 29, 2022 8:54 AM

- URL: https://libguides.unf.edu/litreview

Literature Review: Purpose of a Literature Review

- Literature Review

- Purpose of a Literature Review

- Work in Progress

- Compiling & Writing

- Books, Articles, & Web Pages

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Departmental Differences

- Citation Styles & Plagiarism

- Know the Difference! Systematic Review vs. Literature Review

The purpose of a literature review is to:

- Provide a foundation of knowledge on a topic

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication and give credit to other researchers

- Identify inconstancies: gaps in research, conflicts in previous studies, open questions left from other research

- Identify the need for additional research (justifying your research)

- Identify the relationship of works in the context of their contribution to the topic and other works

- Place your own research within the context of existing literature, making a case for why further study is needed.

Videos & Tutorials

VIDEO: What is the role of a literature review in research? What's it mean to "review" the literature? Get the big picture of what to expect as part of the process. This video is published under a Creative Commons 3.0 BY-NC-SA US license. License, credits, and contact information can be found here: https://www.lib.ncsu.edu/tutorials/litreview/

Elements in a Literature Review

- Elements in a Literature Review txt of infographic

- << Previous: Literature Review

- Next: Searching >>

- Last Updated: Oct 19, 2023 12:07 PM

- URL: https://uscupstate.libguides.com/Literature_Review

Research Process :: Step by Step

- Introduction

- Select Topic

- Identify Keywords

- Background Information

- Develop Research Questions

- Refine Topic

- Search Strategy

- Popular Databases

- Evaluate Sources

- Types of Periodicals

- Reading Scholarly Articles

- Primary & Secondary Sources

- Organize / Take Notes

- Writing & Grammar Resources

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review

- Citation Styles

- Paraphrasing

- Privacy / Confidentiality

- Research Process

- Selecting Your Topic

- Identifying Keywords

- Gathering Background Info

- Evaluating Sources

Organize the literature review into sections that present themes or identify trends, including relevant theory. You are not trying to list all the material published, but to synthesize and evaluate it according to the guiding concept of your thesis or research question.

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. Occasionally you will be asked to write one as a separate assignment, but more often it is part of the introduction to an essay, research report, or thesis. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries

A literature review must do these things:

- be organized around and related directly to the thesis or research question you are developing

- synthesize results into a summary of what is and is not known

- identify areas of controversy in the literature

- formulate questions that need further research

Ask yourself questions like these:

- What is the specific thesis, problem, or research question that my literature review helps to define?

- What type of literature review am I conducting? Am I looking at issues of theory? methodology? policy? quantitative research (e.g. on the effectiveness of a new procedure)? qualitative research (e.g., studies of loneliness among migrant workers)?

- What is the scope of my literature review? What types of publications am I using (e.g., journals, books, government documents, popular media)? What discipline am I working in (e.g., nursing psychology, sociology, medicine)?

- How good was my information seeking? Has my search been wide enough to ensure I've found all the relevant material? Has it been narrow enough to exclude irrelevant material? Is the number of sources I've used appropriate for the length of my paper?

- Have I critically analyzed the literature I use? Do I follow through a set of concepts and questions, comparing items to each other in the ways they deal with them? Instead of just listing and summarizing items, do I assess them, discussing strengths and weaknesses?

- Have I cited and discussed studies contrary to my perspective?

- Will the reader find my literature review relevant, appropriate, and useful?

Ask yourself questions like these about each book or article you include:

- Has the author formulated a problem/issue?

- Is it clearly defined? Is its significance (scope, severity, relevance) clearly established?

- Could the problem have been approached more effectively from another perspective?

- What is the author's research orientation (e.g., interpretive, critical science, combination)?

- What is the author's theoretical framework (e.g., psychological, developmental, feminist)?

- What is the relationship between the theoretical and research perspectives?

- Has the author evaluated the literature relevant to the problem/issue? Does the author include literature taking positions she or he does not agree with?

- In a research study, how good are the basic components of the study design (e.g., population, intervention, outcome)? How accurate and valid are the measurements? Is the analysis of the data accurate and relevant to the research question? Are the conclusions validly based upon the data and analysis?

- In material written for a popular readership, does the author use appeals to emotion, one-sided examples, or rhetorically-charged language and tone? Is there an objective basis to the reasoning, or is the author merely "proving" what he or she already believes?

- How does the author structure the argument? Can you "deconstruct" the flow of the argument to see whether or where it breaks down logically (e.g., in establishing cause-effect relationships)?

- In what ways does this book or article contribute to our understanding of the problem under study, and in what ways is it useful for practice? What are the strengths and limitations?

- How does this book or article relate to the specific thesis or question I am developing?

Text written by Dena Taylor, Health Sciences Writing Centre, University of Toronto

http://www.writing.utoronto.ca/advice/specific-types-of-writing/literature-review

- << Previous: Annotated Bibliography

- Next: Step 5: Cite Sources >>

- Last Updated: Apr 19, 2024 12:43 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uta.edu/researchprocess

University of Texas Arlington Libraries 702 Planetarium Place · Arlington, TX 76019 · 817-272-3000

- Internet Privacy

- Accessibility

- Problems with a guide? Contact Us.

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

5 Reasons the Literature Review Is Crucial to Your Paper

3-minute read

- 8th November 2016

People often treat writing the literature review in an academic paper as a formality. Usually, this means simply listing various studies vaguely related to their work and leaving it at that.

But this overlooks how important the literature review is to a well-written experimental report or research paper. As such, we thought we’d take a moment to go over what a literature review should do and why you should give it the attention it deserves.

What Is a Literature Review?

Common in the social and physical sciences, but also sometimes required in the humanities, a literature review is a summary of past research in your subject area.

Sometimes this is a standalone investigation of how an idea or field of inquiry has developed over time. However, more usually it’s the part of an academic paper, thesis or dissertation that sets out the background against which a study takes place.

There are several reasons why we do this.

Reason #1: To Demonstrate Understanding

In a college paper, you can use a literature review to demonstrate your understanding of the subject matter. This means identifying, summarizing and critically assessing past research that is relevant to your own work.

Reason #2: To Justify Your Research

The literature review also plays a big role in justifying your study and setting your research question . This is because examining past research allows you to identify gaps in the literature, which you can then attempt to fill or address with your own work.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Reason #3: Setting a Theoretical Framework

It can help to think of the literature review as the foundations for your study, since the rest of your work will build upon the ideas and existing research you discuss therein.

A crucial part of this is formulating a theoretical framework , which comprises the concepts and theories that your work is based upon and against which its success will be judged.

Reason #4: Developing a Methodology

Conducting a literature review before beginning research also lets you see how similar studies have been conducted in the past. By examining the strengths and weaknesses of existing research, you can thus make sure you adopt the most appropriate methods, data sources and analytical techniques for your own work.

Reason #5: To Support Your Own Findings

The significance of any results you achieve will depend to some extent on how they compare to those reported in the existing literature. When you come to write up your findings, your literature review will therefore provide a crucial point of reference.

If your results replicate past research, for instance, you can say that your work supports existing theories. If your results are different, though, you’ll need to discuss why and whether the difference is important.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

How to insert a text box in a google doc.

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

2-minute read

How to Cite the CDC in APA

If you’re writing about health issues, you might need to reference the Centers for Disease...

5-minute read

Six Product Description Generator Tools for Your Product Copy

Introduction If you’re involved with ecommerce, you’re likely familiar with the often painstaking process of...

What Is a Content Editor?

Are you interested in learning more about the role of a content editor and the...

4-minute read

The Benefits of Using an Online Proofreading Service

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

- Open access

- Published: 24 April 2024

Breast cancer screening motivation and behaviours of women aged over 75 years: a scoping review

- Virginia Dickson-Swift 1 ,

- Joanne Adams 1 ,

- Evelien Spelten 1 ,

- Irene Blackberry 2 ,

- Carlene Wilson 3 , 4 , 5 &

- Eva Yuen 3 , 6 , 7 , 8

BMC Women's Health volume 24 , Article number: 256 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

175 Accesses

Metrics details

This scoping review aimed to identify and present the evidence describing key motivations for breast cancer screening among women aged ≥ 75 years. Few of the internationally available guidelines recommend continued biennial screening for this age group. Some suggest ongoing screening is unnecessary or should be determined on individual health status and life expectancy. Recent research has shown that despite recommendations regarding screening, older women continue to hold positive attitudes to breast screening and participate when the opportunity is available.

All original research articles that address motivation, intention and/or participation in screening for breast cancer among women aged ≥ 75 years were considered for inclusion. These included articles reporting on women who use public and private breast cancer screening services and those who do not use screening services (i.e., non-screeners).

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for scoping reviews was used to guide this review. A comprehensive search strategy was developed with the assistance of a specialist librarian to access selected databases including: the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Medline, Web of Science and PsychInfo. The review was restricted to original research studies published since 2009, available in English and focusing on high-income countries (as defined by the World Bank). Title and abstract screening, followed by an assessment of full-text studies against the inclusion criteria was completed by at least two reviewers. Data relating to key motivations, screening intention and behaviour were extracted, and a thematic analysis of study findings undertaken.

A total of fourteen (14) studies were included in the review. Thematic analysis resulted in identification of three themes from included studies highlighting that decisions about screening were influenced by: knowledge of the benefits and harms of screening and their relationship to age; underlying attitudes to the importance of cancer screening in women's lives; and use of decision aids to improve knowledge and guide decision-making.

The results of this review provide a comprehensive overview of current knowledge regarding the motivations and screening behaviour of older women about breast cancer screening which may inform policy development.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Breast cancer is now the most commonly diagnosed cancer in the world overtaking lung cancer in 2021 [ 1 ]. Across the globe, breast cancer contributed to 25.8% of the total number of new cases of cancer diagnosed in 2020 [ 2 ] and accounts for a high disease burden for women [ 3 ]. Screening for breast cancer is an effective means of detecting early-stage cancer and has been shown to significantly improve survival rates [ 4 ]. A recent systematic review of international screening guidelines found that most countries recommend that women have biennial mammograms between the ages of 40–70 years [ 5 ] with some recommending that there should be no upper age limit [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ] and others suggesting that benefits of continued screening for women over 75 are not clear [ 13 , 14 , 15 ].

Some guidelines suggest that the decision to end screening should be determined based on the individual health status of the woman, their life expectancy and current health issues [ 5 , 16 , 17 ]. This is because the benefits of mammography screening may be limited after 7 years due to existing comorbidities and limited life expectancy [ 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 ], with some jurisdictions recommending breast cancer screening for women ≥ 75 years only when life expectancy is estimated as at least 7–10 years [ 22 ]. Others have argued that decisions about continuing with screening mammography should depend on individual patient risk and health management preferences [ 23 ]. This decision is likely facilitated by a discussion between a health care provider and patient about the harms and benefits of screening outside the recommended ages [ 24 , 25 ]. While mammography may enable early detection of breast cancer, it is clear that false-positive results and overdiagnosis Footnote 1 may occur. Studies have estimated that up to 25% of breast cancer cases in the general population may be over diagnosed [ 26 , 27 , 28 ].

The risk of being diagnosed with breast cancer increases with age and approximately 80% of new cases of breast cancer in high-income countries are in women over the age of 50 [ 29 ]. The average age of first diagnosis of breast cancer in high income countries is comparable to that of Australian women which is now 61 years [ 2 , 4 , 29 ]. Studies show that women aged ≥ 75 years generally have positive attitudes to mammography screening and report high levels of perceived benefits including early detection of breast cancer and a desire to stay healthy as they age [ 21 , 30 , 31 , 32 ]. Some women aged over 74 participate, or plan to participate, in screening despite recommendations from health professionals and government guidelines advising against it [ 33 ]. Results of a recent review found that knowledge of the recommended guidelines and the potential harms of screening are limited and many older women believed that the benefits of continued screening outweighed the risks [ 30 ].

Very few studies have been undertaken to understand the motivations of women to screen or to establish screening participation rates among women aged ≥ 75 and older. This is surprising given that increasing age is recognised as a key risk factor for the development of breast cancer, and that screening is offered in many locations around the world every two years up until 74 years. The importance of this topic is high given the ambiguity around best practice for participation beyond 74 years. A preliminary search of Open Science Framework, PROSPERO, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and JBI Evidence Synthesis in May 2022 did not locate any reviews on this topic.

This scoping review has allowed for the mapping of a broad range of research to explore the breadth and depth of the literature, summarize the evidence and identify knowledge gaps [ 34 , 35 ]. This information has supported the development of a comprehensive overview of current knowledge of motivations of women to screen and screening participation rates among women outside the targeted age of many international screening programs.

Materials and methods

Research question.

The research question for this scoping review was developed by applying the Population—Concept—Context (PCC) framework [ 36 ]. The current review addresses the research question “What research has been undertaken in high-income countries (context) exploring the key motivations to screen for breast cancer and screening participation (concepts) among women ≥ 75 years of age (population)?

Eligibility criteria

Participants.

Women aged ≥ 75 years were the key population. Specifically, motivations to screen and screening intention and behaviour and the variables that discriminate those who screen from those who do not (non-screeners) were utilised as the key predictors and outcomes respectively.

From a conceptual perspective it was considered that motivation led to behaviour, therefore articles that described motivation and corresponding behaviour were considered. These included articles reporting on women who use public (government funded) and private (fee for service) breast cancer screening services and those who do not use screening services (i.e., non-screeners).

The scope included high-income countries using the World Bank definition [ 37 ]. These countries have broadly similar health systems and opportunities for breast cancer screening in both public and private settings.

Types of sources

All studies reporting original research in peer-reviewed journals from January 2009 were eligible for inclusion, regardless of design. This date was selected due to an evaluation undertaken for BreastScreen Australia recommending expansion of the age group to include 70–74-year-old women [ 38 ]. This date was also indicative of international debate regarding breast cancer screening effectiveness at this time [ 39 , 40 ]. Reviews were also included, regardless of type—scoping, systematic, or narrative. Only sources published in English and available through the University’s extensive research holdings were eligible for inclusion. Ineligible materials were conference abstracts, letters to the editor, editorials, opinion pieces, commentaries, newspaper articles, dissertations and theses.

This scoping review was registered with the Open Science Framework database ( https://osf.io/fd3eh ) and followed Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for scoping reviews [ 35 , 36 ]. Although ethics approval is not required for scoping reviews the broader study was approved by the University Ethics Committee (approval number HEC 21249).

Search strategy

A pilot search strategy was developed in consultation with an expert health librarian and tested in MEDLINE (OVID) and conducted on 3 June 2022. Articles from this pilot search were compared with seminal articles previously identified by the members of the team and used to refine the search terms. The search terms were then searched as both keywords and subject headings (e.g., MeSH) in the titles and abstracts and Boolean operators employed. A full MEDLINE search was then carried out by the librarian (see Table 1 ). This search strategy was adapted for use in each of the following databases: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE), Web of Science and PsychInfo databases. The references of included studies have been hand-searched to identify any additional evidence sources.

Study/source of evidence selection

Following the search, all identified citations were collated and uploaded into EndNote v.X20 (Clarivate Analytics, PA, USA) and duplicates removed. The resulting articles were then imported into Covidence – Cochrane’s systematic review management software [ 41 ]. Duplicates were removed once importation was complete, and title and abstract screening was undertaken against the eligibility criteria. A sample of 25 articles were assessed by all reviewers to ensure reliability in the application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Team discussion was used to ensure consistent application. The Covidence software supports blind reviewing with two reviewers required at each screening phase. Potentially relevant sources were retrieved in full text and were assessed against the inclusion criteria by two independent reviewers. Conflicts were flagged within the software which allows the team to discuss those that have disagreements until a consensus was reached. Reasons for exclusion of studies at full text were recorded and reported in the scoping review. The Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist was used to guide the reporting of the review [ 42 ] and all stages were documented using the PRISMA-ScR flow chart [ 42 ].

Data extraction

A data extraction form was created in Covidence and used to extract study characteristics and to confirm the study’s relevance. This included specific details such as article author/s, title, year of publication, country, aim, population, setting, data collection methods and key findings relevant to the review question. The draft extraction form was modified as needed during the data extraction process.

Data analysis and presentation

Extracted data were summarised in tabular format (see Table 2 ). Consistent with the guidelines for the effective reporting of scoping reviews [ 43 ] and the JBI framework [ 35 ] the final stage of the review included thematic analysis of the key findings of the included studies. Study findings were imported into QSR NVivo with coding of each line of text. Descriptive codes reflected key aspects of the included studies related to the motivations and behaviours of women > 75 years about breast cancer screening.

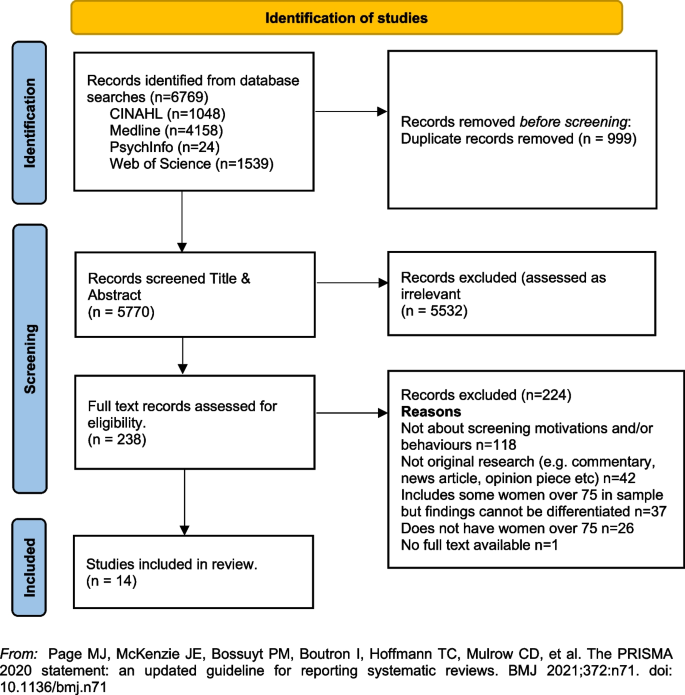

In line with the reporting requirements for scoping reviews the search results for this review are presented in Fig. 1 [ 44 ].

PRISMA Flowchart. From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

A total of fourteen [ 14 ] studies were included in the review with studies from the following countries, US n = 12 [ 33 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 ], UK n = 1 [ 23 ] and France n = 1 [ 56 ]. Sample sizes varied, with most containing fewer than 50 women ( n = 8) [ 33 , 45 , 46 , 48 , 51 , 52 , 55 ]. Two had larger samples including a French study with 136 women (a sub-set of a larger sample) [ 56 ], and one mixed method study in the UK with a sample of 26 women undertaking interviews and 479 women completing surveys [ 23 ]. One study did not report exact numbers [ 50 ]. Three studies [ 47 , 53 , 54 ] were undertaken by a group of researchers based in the US utilising the same sample of women, however each of the papers focused on different primary outcomes. The samples in the included studies were recruited from a range of locations including primary medical care clinics, specialist medical clinics, University affiliated medical clinics, community-based health centres and community outreach clinics [ 47 , 53 , 54 ].

Data collection methods varied and included: quantitative ( n = 8), qualitative ( n = 5) and mixed methods ( n = 1). A range of data collection tools and research designs were utilised; pre/post, pilot and cross-sectional surveys, interviews, and secondary analysis of existing data sets. Seven studies focused on the use of a Decision Aids (DAs), either in original or modified form, developed by Schonberg et al. [ 55 ] as a tool to increase knowledge about the harms and benefits of screening for older women [ 45 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 52 , 54 , 55 ]. Three studies focused on intention to screen [ 33 , 53 , 56 ], two on knowledge of, and attitudes to, screening [ 23 , 46 ], one on information needs relating to risks and benefits of screening discontinuation [ 51 ], and one on perceptions about discontinuation of screening and impact of social interactions on screening [ 50 ].

The three themes developed from the analysis of the included studies highlighted that decisions about screening were primarily influenced by: (1) knowledge of the benefits and harms of screening and their relationship to age; (2) underlying attitudes to the importance of cancer screening in women's lives; and (3) exposure to decision aids designed to facilitate informed decision-making. Each of these themes will be presented below drawing on the key findings of the appropriate studies. The full dataset of extracted data can be found in Table 2 .

Knowledge of the benefits and harms of screening ≥ 75 years

The decision to participate in routine mammography is influenced by individual differences in cognition and affect, interpersonal relationships, provider characteristics, and healthcare system variables. Women typically perceive mammograms as a positive, beneficial and routine component of care [ 46 ] and an important aspect of taking care of themselves [ 23 , 46 , 49 ]. One qualitative study undertaken in the US showed that few women had discussed mammography cessation or the potential harms of screening with their health care providers and some women reported they would insist on receiving mammography even without a provider recommendation to continue screening [ 46 ].

Studies suggested that ageing itself, and even poor health, were not seen as reasonable reasons for screening cessation. For many women, guidance from a health care provider was deemed the most important influence on decision-making [ 46 ]. Preferences for communication about risk and benefits were varied with one study reporting women would like to learn more about harms and risks and recommended that this information be communicated via physicians or other healthcare providers, included in brochures/pamphlets, and presented outside of clinical settings (e.g., in community-based seniors groups) [ 51 ]. Others reported that women were sometimes sceptical of expert and government recommendations [ 33 ] although some were happy to participate in discussions with health educators or care providers about breast cancer screening harms and benefits and potential cessation [ 52 ].

Underlying attitudes to the importance of cancer screening at and beyond 75 years

Included studies varied in describing the importance of screening, with some attitudes based on past attendance and some based on future intentions to screen. Three studies reported findings indicating that some women intended to continue screening after 75 years of age [ 23 , 45 , 46 ], with one study in the UK reporting that women supported an extension of the automatic recall indefinitely, regardless of age or health status. In this study, failure to invite older women to screen was interpreted as age discrimination [ 23 ]. The desire to continue screening beyond 75 was also highlighted in a study from France that found that 60% of the women ( n = 136 aged ≥ 75) intended to pursue screening in the future, and 27 women aged ≥ 75, who had never undergone mammography previously (36%), intended to do so in the future [ 56 ]. In this same study, intentions to screen varied significantly [ 56 ]. There were no sociodemographic differences observed between screened and unscreened women with regard to level of education, income, health risk behaviour (smoking, alcohol consumption), knowledge about the importance and the process of screening, or psychological features (fear of the test, fear of the results, fear of the disease, trust in screening impact) [ 56 ]. Further analysis showed that three items were statistically correlated with a higher rate of attendance at screening: (1) screening was initiated by a physician; (2) the women had a consultation with a gynaecologist during the past 12 months; and (3) the women had already undergone at least five screening mammograms. Analysis highlighted that although average income, level of education, psychological features or other types of health risk behaviours did not impact screening intention, having a mammogram previously impacted likelihood of ongoing screening. There was no information provided that explained why women who had not previously undergone screening might do so in the future.

A mixed methods study in the UK reported similar findings [ 23 ]. Utilising interviews ( n = 26) and questionnaires ( n = 479) with women ≥ 70 years (median age 75 years) the overwhelming result (90.1%) was that breast screening should be offered to all women indefinitely regardless of age, health status or fitness [ 23 ], and that many older women were keen to continue screening. Both the interview and survey data confirmed women were uncertain about eligibility for breast screening. The survey data showed that just over half the women (52.9%) were unaware that they could request mammography or knew how to access it. Key reasons for screening discontinuation were not being invited for screening (52.1%) and not knowing about self-referral (35.1%).

Women reported that not being invited to continue screening sent messages that screening was no longer important or required for this age group [ 23 ]. Almost two thirds of the women completing the survey (61.6%) said they would forget to attend screening without an invitation. Other reasons for screening discontinuation included transport difficulties (25%) and not wishing to burden family members (24.7%). By contrast, other studies have reported that women do not endorse discontinuation of screening mammography due to advancing age or poor health, but some may be receptive to reducing screening frequency on recommendation from their health care provider [ 46 , 51 ].

Use of Decision Aids (DAs) to improve knowledge and guide screening decision-making

Many women reported poor knowledge about the harms and benefits of screening with studies identifying an important role for DAs. These aids have been shown to be effective in improving knowledge of the harms and benefits of screening [ 45 , 54 , 55 ] including for women with low educational attainment; as compared to women with high educational attainment [ 47 ]. DAs can increase knowledge about screening [ 47 , 49 ] and may decrease the intention to continue screening after the recommended age [ 45 , 52 , 54 ]. They can be used by primary care providers to support a conversation about breast screening intention and reasons for discontinuing screening. In one pilot study undertaken in the US using a DA, 5 of the 8 women (62.5%) indicated they intended to continue to receive mammography; however, 3 participants planned to get them less often [ 45 ]. When asked whether they thought their physician would want them to get a mammogram, 80% said “yes” on pre-test; this figure decreased to 62.5% after exposure to the DA. This pilot study suggests that the use of a decision-aid may result in fewer women ≥ 75 years old continuing to screen for breast cancer [ 45 ].

Similar findings were evident in two studies drawing on the same data undertaken in the US [ 48 , 53 ]. Using a larger sample ( n = 283), women’s intentions to screen prior to a visit with their primary care provider and then again after exposure to the DA were compared. Results showed that 21.7% of women reduced their intention to be screened, 7.9% increased their intentions to be screened, and 70.4% did not change. Compared to those who had no change or increased their screening intentions, women who had a decrease in screening intention were significantly less likely to receive screening after 18 months. Generally, studies have shown that women aged 75 and older find DAs acceptable and helpful [ 47 , 48 , 49 , 55 ] and using them had the potential to impact on a women’s intention to screen [ 55 ].

Cadet and colleagues [ 49 ] explored the impact of educational attainment on the use of DAs. Results highlight that education moderates the utility of these aids; women with lower educational attainment were less likely to understand all the DA’s content (46.3% vs 67.5%; P < 0.001); had less knowledge of the benefits and harms of mammography (adjusted mean ± standard error knowledge score, 7.1 ± 0.3 vs 8.1 ± 0.3; p < 0.001); and were less likely to have their screening intentions impacted (adjusted percentage, 11.4% vs 19.4%; p = 0.01).

This scoping review summarises current knowledge regarding motivations and screening behaviours of women over 75 years. The findings suggest that awareness of the importance of breast cancer screening among women aged ≥ 75 years is high [ 23 , 46 , 49 ] and that many women wish to continue screening regardless of perceived health status or age. This highlights the importance of focusing on motivation and screening behaviours and the multiple factors that influence ongoing participation in breast screening programs.

The generally high regard attributed to screening among women aged ≥ 75 years presents a complex challenge for health professionals who are focused on potential harm (from available national and international guidelines) in ongoing screening for women beyond age 75 [ 18 , 20 , 57 ]. Included studies highlight that many women relied on the advice of health care providers regarding the benefits and harms when making the decision to continue breast screening [ 46 , 51 , 52 ], however there were some that did not [ 33 ]. Having a previous pattern of screening was noted as being more significant to ongoing intention than any other identified socio-demographic feature [ 56 ]. This is perhaps because women will not readily forgo health care practices that they have always considered important and that retain ongoing importance for the broader population.

For those women who had discontinued screening after the age of 74 it was apparent that the rationale for doing so was not often based on choice or receipt of information, but rather on factors that impact decision-making in relation to screening. These included no longer receiving an invitation to attend, transport difficulties and not wanting to be a burden on relatives or friends [ 23 , 46 , 51 ]. Ongoing receipt of invitations to screen was an important aspect of maintaining a capacity to choose [ 23 ]. This was particularly important for those women who had been regular screeners.

Women over 75 require more information to make decisions regarding screening [ 23 , 52 , 54 , 55 ], however health care providers must also be aware that the element of choice is important for older women. Having a capacity to choose avoids any notion of discrimination based on age, health status, gender or sociodemographic difference and acknowledges the importance of women retaining control over their health [ 23 ]. It was apparent that some women would choose to continue screening at a reduced frequency if this option was available and that women should have access to information facilitating self-referral [ 23 , 45 , 46 , 51 , 56 ].

Decision-making regarding ongoing breast cancer screening has been facilitated via the use of Decision Aids (DAs) within clinical settings [ 54 , 55 ]. While some studies suggest that women will make a decision regardless of health status, the use of DAs has impacted women’s decision to screen. While this may have limited benefit for those of lower educational attainment [ 48 ] they have been effective in improving knowledge relating to harms and benefits of screening particularly where they have been used to support a conversation with women about the value of screening [ 54 , 55 , 56 ].

Women have identified challenges in engaging in conversations with health care providers regarding ongoing screening, because providers frequently draw on projections of life expectancy and over-diagnosis [ 17 , 51 ]. As a result, these conversations about screening after age 75 years often do not occur [ 46 ]. It is likely that health providers may need more support and guidance in leading these conversations. This may be through the use of DAs or standardised checklists. It may be possible to incorporate these within existing health preventive measures for this age group. The potential for advice regarding ongoing breast cancer screening to be available outside of clinical settings may provide important pathways for conversations with women regarding health choices. Provision of information and advice in settings such as community based seniors groups [ 51 ] offers a potential platform to broaden conversations and align sources of information, not only with health professionals but amongst women themselves. This may help to address any misconception regarding eligibility and access to services [ 23 ]. It may also be aligned with other health promotion and lifestyle messages provided to this age group.

Limitations of the review

The searches that formed the basis of this review were carried in June 2022. Although the search was comprehensive, we have only captured those studies that were published in the included databases from 2009. There may have been other studies published outside of these periods. We also limited the search to studies published in English with full-text availability.

The emphasis of a scoping review is on comprehensive coverage and synthesis of the key findings, rather than on a particular standard of evidence and, consequently a quality assessment of the included studies was not undertaken. This has resulted in the inclusion of a wide range of study designs and data collection methods. It is important to note that three studies included in the review drew on the same sample of women (283 over > 75)[ 49 , 53 , 54 ]. The results of this review provide valuable insights into motivations and behaviours for breast cancer screening for older women, however they should be interpreted with caution given the specific methodological and geographical limitations.

Conclusion and recommendations

This scoping review highlighted a range of key motivations and behaviours in relation to breast cancer screening for women ≥ 75 years of age. The results provide some insight into how decisions about screening continuation after 74 are made and how informed decision-making can be supported. Specifically, this review supports the following suggestions for further research and policy direction:

Further research regarding breast cancer screening motivations and behaviours for women over 75 would provide valuable insight for health providers delivering services to women in this age group.

Health providers may benefit from the broader use of decision aids or structured checklists to guide conversations with women over 75 regarding ongoing health promotion/preventive measures.

Providing health-based information in non-clinical settings frequented by women in this age group may provide a broader reach of information and facilitate choices. This may help to reduce any perception of discrimination based on age, health status or socio-demographic factors.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study is included in this published article (see Table 2 above).

Cancer Australia, in their 2014 position statement, define “overdiagnosis” in the following way. ‘’Overdiagnosis’ from breast screening does not refer to error or misdiagnosis, but rather refers to breast cancer diagnosed by screening that would not otherwise have been diagnosed during a woman’s lifetime. “Overdiagnosis” includes all instances where cancers detected through screening (ductal carcinoma in situ or invasive breast cancer) might never have progressed to become symptomatic during a woman’s life, i.e., cancer that would not have been detected in the absence of screening. It is not possible to precisely predict at diagnosis, to which cancers overdiagnosis would apply.” (accessed 22. nd August 2022; https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/resources/position-statements/overdiagnosis-mammographic-screening ).

World Health Organization. Breast Cancer Geneva: WHO; 2021 [Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/breast-cancer#:~:text=Reducing%20global%20breast%20cancer%20mortality,and%20comprehensive%20breast%20cancer%20management .

International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). IARC Handbooks on Cancer Screening: Volume 15 Breast Cancer Geneva: IARC; 2016 [Available from: https://publications.iarc.fr/Book-And-Report-Series/Iarc-Handbooks-Of-Cancer-Prevention/Breast-Cancer-Screening-2016 .

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer in Australia 2021 [Available from: https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/cancer-types/breast-cancer/statistics .

Breast Cancer Network Australia. Current breast cancer statistics in Australia 2020 [Available from: https://www.bcna.org.au/media/7111/bcna-2019-current-breast-cancer-statistics-in-australia-11jan2019.pdf .

Ren W, Chen M, Qiao Y, Zhao F. Global guidelines for breast cancer screening: A systematic review. The Breast. 2022;64:85–99.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Cardoso F, Kyriakides S, Ohno S, Penault-Llorca F, Poortmans P, Rubio IT, et al. Early breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(8):1194–220.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Hamashima C, Hattori M, Honjo S, Kasahara Y, Katayama T, Nakai M, et al. The Japanese guidelines for breast cancer screening. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2016;46(5):482–92.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bevers TB, Helvie M, Bonaccio E, Calhoun KE, Daly MB, Farrar WB, et al. Breast cancer screening and diagnosis, version 3.2018, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Net. 2018;16(11):1362–89.

Article Google Scholar

He J, Chen W, Li N, Shen H, Li J, Wang Y, et al. China guideline for the screening and early detection of female breast cancer (2021, Beijing). Zhonghua Zhong liu za zhi [Chinese Journal of Oncology]. 2021;43(4):357–82.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Cancer Australia. Early detection of breast cancer 2021 [cited 2022 25 July]. Available from: https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/resources/position-statements/early-detection-breast-cancer .

Schünemann HJ, Lerda D, Quinn C, Follmann M, Alonso-Coello P, Rossi PG, et al. Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis: A Synopsis of the European Breast Guidelines. Ann Intern Med. 2019;172(1):46–56.

World Health Organization. WHO Position Paper on Mammography Screening Geneva WHO. 2016.

Google Scholar

Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Gulati R, Mariotto AB. Personalizing age of cancer screening cessation based on comorbid conditions: model estimates of harms and benefits. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:104.

Lee CS, Moy L, Joe BN, Sickles EA, Niell BL. Screening for Breast Cancer in Women Age 75 Years and Older. Am J Roentgenol. 2017;210(2):256–63.

Broeders M, Moss S, Nystrom L. The impact of mammographic screening on breast cancer mortality in Europe: a review of observational studies. J Med Screen. 2012;19(suppl 1):14.

Oeffinger KC, Fontham ETH, Etzioni R, Herzig A, Michaelson JS, Shih YCT, et al. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 Guideline update from the American cancer society. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. 2015;314(15):1599–614.

Walter LC, Schonberg MA. Screening mammography in older women: a review. JAMA. 2014;311:1336.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar