Essay Papers Writing Online

10 effective techniques to master persuasive essay writing and convince any audience.

As a skilled communicator, your ability to persuade others is crucial in many areas of life. Whether you’re presenting an argument, advocating for a cause, or simply trying to convince someone of your point of view, your persuasive essay can be a powerful tool. However, crafting an essay that truly convinces your reader requires more than just strong opinions and eloquent language. It requires a strategic approach that combines logical reasoning, emotional appeal, and effective writing techniques.

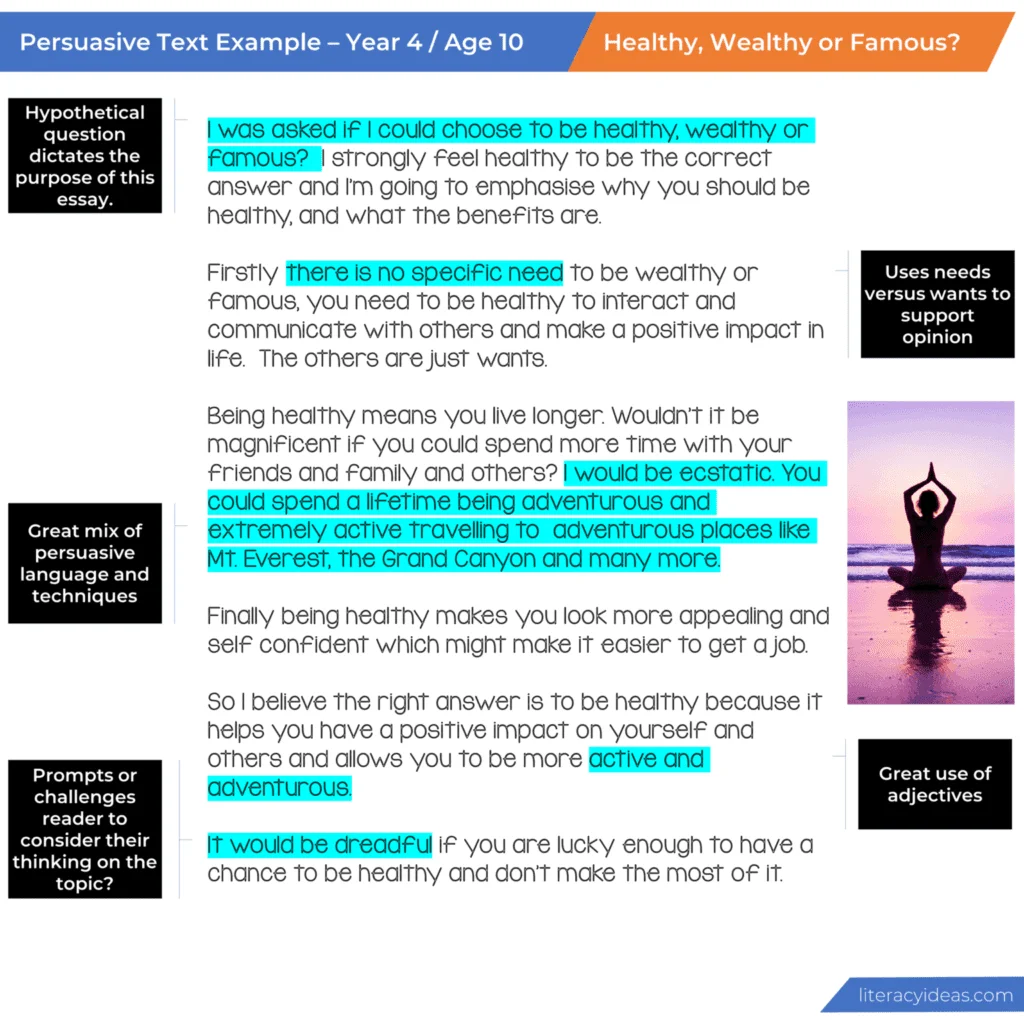

1. Craft a Compelling Introduction: Your introduction is the first impression you make on your reader, so it’s essential to capture their attention right from the start. Consider using a captivating anecdote, a thought-provoking question, or a shocking statistic to engage your audience and set the tone for your essay. By immediately grabbing their interest, you increase the chances that they’ll continue reading and be open to your persuasive arguments.

2. Clearly Define Your Position: Before launching into the main body of your essay, make sure to clearly state your position on the topic. This will help your reader understand your stance and follow your line of reasoning throughout the essay. Use concise and assertive language to communicate your position, and consider reinforcing it with strong evidence or expert opinions that support your viewpoint.

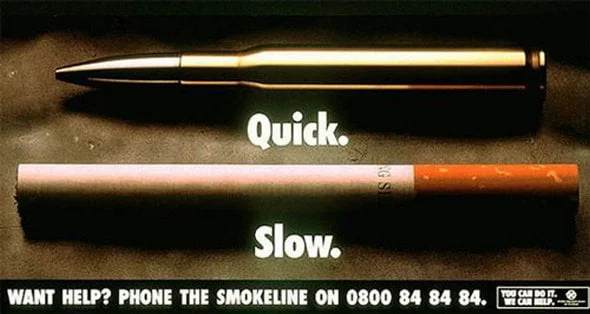

3. Appeal to Emotions: While rational arguments are important, emotions often play a significant role in persuasive writing. Connect with your reader on an emotional level by using vivid descriptions, personal anecdotes, or powerful metaphors. By eliciting an emotional response, you can create a deeper connection with your audience and make your arguments more compelling.

Choose a compelling topic that ignites your passion

When crafting a persuasive essay, it is crucial to select a topic that not only captivates and engages your readers but also resonates strongly with you. By choosing a compelling topic that ignites your passion, you will be able to infuse enthusiasm and conviction into your writing, making it more convincing and persuasive.

While it may be tempting to select a popular or trending topic, it is essential to choose something that you deeply care about and have a genuine interest in. Your passion for the subject matter will shine through in your writing, capturing the attention and interest of your readers.

- Explore your hobbies and personal interests.

- Reflect on societal issues that deeply affect you.

- Consider topics that challenge conventional thinking.

- Analyze current events and their impact on your community or society as a whole.

- Look for subjects that inspire debate and differing opinions.

- Examine topics that align with your values and beliefs.

By choosing a topic that you are not only knowledgeable about but also passionate about, you will have a stronger emotional connection to your writing. This emotional connection will allow you to effectively convey your argument, influence your readers’ perspectives, and ultimately convince them to see things from your point of view.

Remember, the key to writing a persuasive essay lies in your ability to convey your ideas convincingly. By selecting a compelling topic that ignites your passion, you will have a solid foundation for crafting a persuasive essay that will resonate with readers and leave a lasting impact. So, take the time to explore your interests and choose a topic that truly captivates you.

Conduct thorough research to gather supporting evidence

Gathering strong evidence is a vital step in writing a persuasive essay. Convincing your readers requires you to present compelling facts, statistics, expert opinions, and examples that support your arguments. To achieve this, it is crucial to conduct thorough research to collect relevant and reliable information.

Begin by determining the main points you want to convey in your essay. These points should align with your thesis statement and support your overall argument. Once you have a clear idea of what you are trying to communicate, start gathering supporting evidence.

Research various credible sources such as academic journals, books, reputable websites, and expert interviews. Look for information that directly relates to your topic and can be used to reinforce your arguments. Be sure to verify the credibility and reliability of your sources to ensure the accuracy of the information.

Take notes as you conduct your research, highlighting key points, supporting evidence, and any quotes or statistics that you may want to include in your essay. It is essential to organize your findings in a way that makes sense and flows logically in your essay.

When using statistics or data, make sure to cite the sources properly to give credit to the original authors and establish your credibility as a writer. This will also allow your readers to verify the information themselves if they wish to do so.

By conducting thorough research and gathering strong supporting evidence, you will be able to present a persuasive and well-supported argument in your essay. This will not only convince your readers but also showcase your knowledge, understanding, and dedication to the topic at hand.

Develop a clear and concise thesis statement

One of the most important aspects of writing a persuasive essay is developing a thesis statement that is clear, concise, and compelling. A thesis statement serves as the main argument or central idea of your essay. It sets the tone for the entire piece and helps to guide your reader through your argument.

When developing your thesis statement, it’s essential to choose a strong and persuasive statement that clearly states your position on the topic. Avoid vague or ambiguous language that can confuse your reader and weaken your argument. Instead, use strong and specific language that clearly conveys your main point.

Your thesis statement should be concise, meaning it should be expressed in a clear and straightforward manner. Avoid unnecessary words or phrases that can dilute your message and make it less powerful. Instead, focus on getting your point across in as few words as possible while still maintaining clarity and impact.

Additionally, your thesis statement should be compelling and persuasive. It should motivate your reader to continue reading and consider your argument. Use persuasive language and strong evidence to support your thesis statement and convince your reader of its validity.

In summary, developing a clear and concise thesis statement is crucial for writing a persuasive essay. Choose a strong statement that clearly conveys your position, use concise language to express your point, and make your statement compelling and persuasive. By doing so, you will create a strong foundation for your entire essay and increase your chances of convincing your reader.

Use persuasive language and rhetorical devices

When it comes to crafting a compelling persuasive essay, one must master the art of persuasive language and employ various rhetorical devices. The way you choose your words and structure your sentences can make all the difference in captivating and convincing your readers.

One effective technique is to use strong and powerful language that evokes emotion and creates a sense of urgency. The use of vivid and descriptive words can paint a picture in the minds of your readers, making your arguments more relatable and engaging.

Additionally, employing rhetorical devices such as metaphors, similes, and analogies can effectively convey your message and help your readers understand complex ideas. By drawing comparisons and creating associations, you can make abstract concepts more tangible and easier to grasp.

Another valuable device is repetition. By repeating key phrases or ideas throughout your essay, you can emphasize your points and reinforce your arguments. This technique can help make your arguments more memorable and leave a lasting impact on your readers.

Furthermore, using rhetorical questions can encourage your readers to think critically about your topic and consider your perspective. By posing thought-provoking questions, you can guide your readers towards your desired conclusions and make them actively engage with your essay.

Lastly, employing the use of anecdotes and personal stories can make your essay more relatable and establish a connection with your readers. By sharing real-life examples or experiences, you can offer concrete evidence to support your arguments and establish credibility.

In conclusion, mastering persuasive language and employing rhetorical devices can greatly enhance the effectiveness of your persuasive essay. By choosing your words carefully, using powerful language, and incorporating various rhetorical techniques, you can captivate your readers and present your arguments in a compelling and convincing manner.

Address counterarguments and refute them with strong evidence

When writing a persuasive essay, it is crucial to anticipate and address potential counterarguments to strengthen your argument. By acknowledging opposing viewpoints and then refuting them with strong evidence, you can demonstrate the credibility and validity of your own position.

One effective way to address counterarguments is to acknowledge them upfront and present them in an objective and unbiased manner. By doing so, you show that you have considered different perspectives and are willing to engage in a fair and balanced discussion. This approach also helps you connect with readers who may initially hold opposing views, as it shows respect for their opinions and demonstrates your willingness to engage in thoughtful debate.

To effectively refute counterarguments, it is important to use strong evidence that supports your own position. This can include data, statistics, expert opinions, research findings, and real-life examples. By providing convincing evidence, you can demonstrate the superiority of your argument and weaken the credibility of counterarguments. Be sure to cite credible sources and use persuasive language to present your evidence in a convincing way.

In addition to providing strong evidence, it is also important to anticipate and address potential weaknesses in your own argument. By acknowledging and addressing these weaknesses, you can show that you have thoroughly considered your stance and are able to respond to potential criticisms. This helps to build trust and credibility with your readers, as they can see that you are aware of the limitations of your argument and have taken steps to address them.

In conclusion, addressing counterarguments and refuting them with strong evidence is a crucial component of persuasive writing. By acknowledging opposing viewpoints and providing solid evidence to support your own position, you can strengthen your argument and convince readers to adopt your point of view. Remember to always approach counterarguments objectively, use persuasive language, and address any potential weaknesses in your own argument. By doing so, you can create a compelling and persuasive essay that will resonate with your readers.

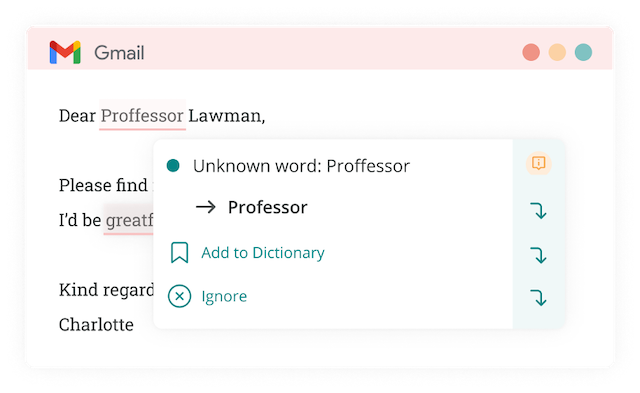

Edit and proofread your essay for grammar and clarity

Once you’ve completed your persuasive essay, the work isn’t quite finished. It’s essential to go back and review your writing with a critical eye, focusing on grammar and clarity. This final step is crucial in ensuring that your arguments are effectively communicated and that your reader can easily understand and follow your points.

First and foremost, pay attention to grammar. Look for any errors in your sentence structure, verb tense, subject-verb agreement, and punctuation. Make sure that your sentences are clear and concise, without any unnecessary or confusing phrases. Correct any spelling mistakes or typos that may have slipped through the cracks.

Next, consider the overall clarity of your essay. Read through each paragraph and ensure that your ideas flow logically and cohesively. Are your arguments supported by evidence and examples? Are your transitions smooth and seamless? If necessary, revise or rearrange your paragraphs to strengthen the overall structure of your essay.

It’s also important to check for any ambiguous or vague language. Make sure that your words and phrases have precise meanings and can be easily understood by your reader. Consider whether there are any areas where you could provide more clarification or add further details to strengthen your points.

When editing and proofreading, it can be helpful to read your essay out loud. This can help you identify any awkward or convoluted sentences, as well as any areas where you may have used repetitive or redundant language. Reading aloud also allows you to hear the natural rhythm and flow of your writing, giving you a better sense of how your words will be perceived by the reader.

Finally, consider seeking feedback from others. Share your essay with a trusted friend, family member, or teacher and ask for their input. They may be able to offer valuable suggestions or catch any errors that you may have missed. Sometimes, a fresh set of eyes can provide a new perspective and help you improve your essay even further.

By taking the time to edit and proofread your essay for grammar and clarity, you can ensure that your persuasive arguments are presented in the most effective and compelling way possible. This attention to detail will not only demonstrate your strong writing skills, but it will also increase the chances of convincing your reader to see things from your perspective.

Related Post

How to master the art of writing expository essays and captivate your audience, convenient and reliable source to purchase college essays online, step-by-step guide to crafting a powerful literary analysis essay, unlock success with a comprehensive business research paper example guide, unlock your writing potential with writers college – transform your passion into profession, “unlocking the secrets of academic success – navigating the world of research papers in college”, master the art of sociological expression – elevate your writing skills in sociology.

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

How to Write a Persuasive Essay: Tips and Tricks

Allison Bressmer

Most composition classes you’ll take will teach the art of persuasive writing. That’s a good thing.

Knowing where you stand on issues and knowing how to argue for or against something is a skill that will serve you well both inside and outside of the classroom.

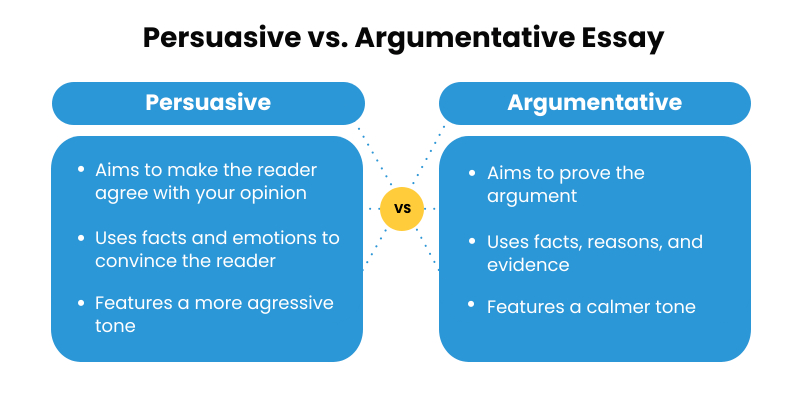

Persuasion is the art of using logic to prompt audiences to change their mind or take action , and is generally seen as accomplishing that goal by appealing to emotions and feelings.

A persuasive essay is one that attempts to get a reader to agree with your perspective.

Ready for some tips on how to produce a well-written, well-rounded, well-structured persuasive essay? Just say yes. I don’t want to have to write another essay to convince you!

How Do I Write a Persuasive Essay?

What are some good topics for a persuasive essay, how do i identify an audience for my persuasive essay, how do you create an effective persuasive essay, how should i edit my persuasive essay.

Your persuasive essay needs to have the three components required of any essay: the introduction , body , and conclusion .

That is essay structure. However, there is flexibility in that structure.

There is no rule (unless the assignment has specific rules) for how many paragraphs any of those sections need.

Although the components should be proportional; the body paragraphs will comprise most of your persuasive essay.

How Do I Start a Persuasive Essay?

As with any essay introduction, this paragraph is where you grab your audience’s attention, provide context for the topic of discussion, and present your thesis statement.

TIP 1: Some writers find it easier to write their introductions last. As long as you have your working thesis, this is a perfectly acceptable approach. From that thesis, you can plan your body paragraphs and then go back and write your introduction.

TIP 2: Avoid “announcing” your thesis. Don’t include statements like this:

- “In my essay I will show why extinct animals should (not) be regenerated.”

- “The purpose of my essay is to argue that extinct animals should (not) be regenerated.”

Announcements take away from the originality, authority, and sophistication of your writing.

Instead, write a convincing thesis statement that answers the question "so what?" Why is the topic important, what do you think about it, and why do you think that? Be specific.

How Many Paragraphs Should a Persuasive Essay Have?

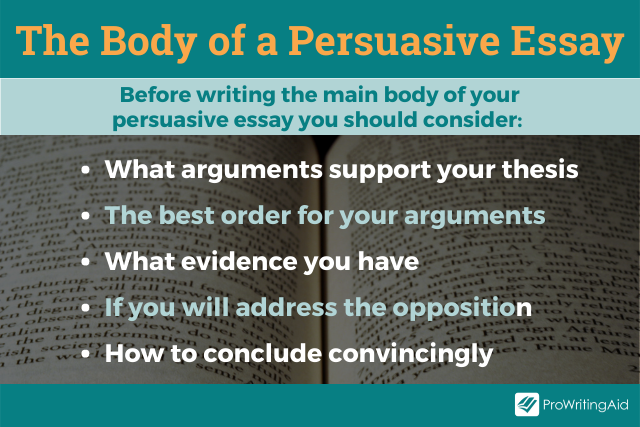

This body of your persuasive essay is the section in which you develop the arguments that support your thesis. Consider these questions as you plan this section of your essay:

- What arguments support your thesis?

- What is the best order for your arguments?

- What evidence do you have?

- Will you address the opposing argument to your own?

- How can you conclude convincingly?

TIP: Brainstorm and do your research before you decide which arguments you’ll focus on in your discussion. Make a list of possibilities and go with the ones that are strongest, that you can discuss with the most confidence, and that help you balance your rhetorical triangle .

What Should I Put in the Conclusion of a Persuasive Essay?

The conclusion is your “mic-drop” moment. Think about how you can leave your audience with a strong final comment.

And while a conclusion often re-emphasizes the main points of a discussion, it shouldn’t simply repeat them.

TIP 1: Be careful not to introduce a new argument in the conclusion—there’s no time to develop it now that you’ve reached the end of your discussion!

TIP 2 : As with your thesis, avoid announcing your conclusion. Don’t start your conclusion with “in conclusion” or “to conclude” or “to end my essay” type statements. Your audience should be able to see that you are bringing the discussion to a close without those overused, less sophisticated signals.

If your instructor has assigned you a topic, then you’ve already got your issue; you’ll just have to determine where you stand on the issue. Where you stand on your topic is your position on that topic.

Your position will ultimately become the thesis of your persuasive essay: the statement the rest of the essay argues for and supports, intending to convince your audience to consider your point of view.

If you have to choose your own topic, use these guidelines to help you make your selection:

- Choose an issue you truly care about

- Choose an issue that is actually debatable

Simple “tastes” (likes and dislikes) can’t really be argued. No matter how many ways someone tries to convince me that milk chocolate rules, I just won’t agree.

It’s dark chocolate or nothing as far as my tastes are concerned.

Similarly, you can’t convince a person to “like” one film more than another in an essay.

You could argue that one movie has superior qualities than another: cinematography, acting, directing, etc. but you can’t convince a person that the film really appeals to them.

Once you’ve selected your issue, determine your position just as you would for an assigned topic. That position will ultimately become your thesis.

Until you’ve finalized your work, consider your thesis a “working thesis.”

This means that your statement represents your position, but you might change its phrasing or structure for that final version.

When you’re writing an essay for a class, it can seem strange to identify an audience—isn’t the audience the instructor?

Your instructor will read and evaluate your essay, and may be part of your greater audience, but you shouldn’t just write for your teacher.

Think about who your intended audience is.

For an argument essay, think of your audience as the people who disagree with you—the people who need convincing.

That population could be quite broad, for example, if you’re arguing a political issue, or narrow, if you’re trying to convince your parents to extend your curfew.

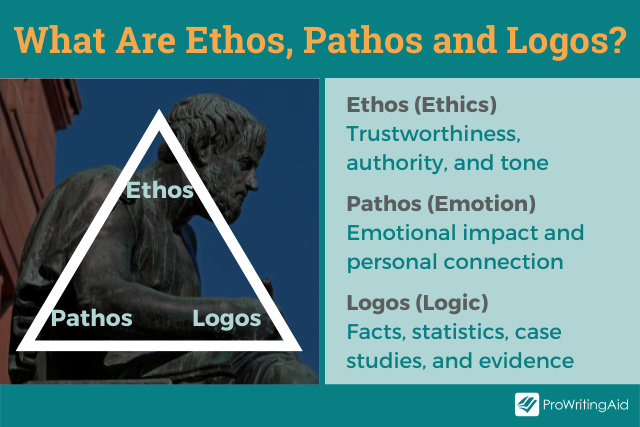

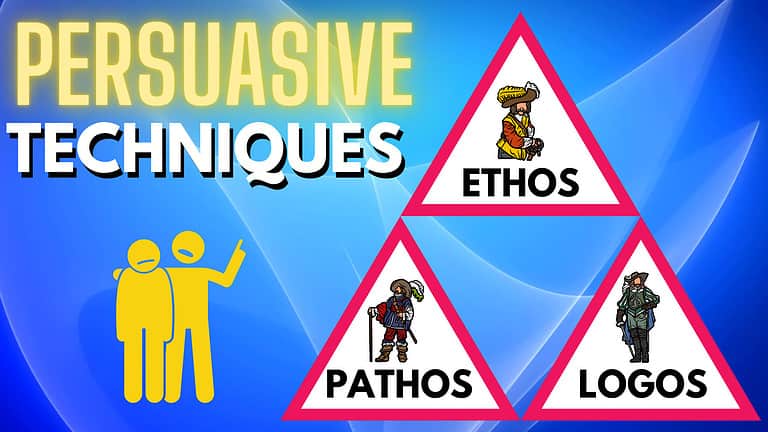

Once you’ve got a sense of your audience, it’s time to consult with Aristotle. Aristotle’s teaching on persuasion has shaped communication since about 330 BC. Apparently, it works.

Aristotle taught that in order to convince an audience of something, the communicator needs to balance the three elements of the rhetorical triangle to achieve the best results.

Those three elements are ethos , logos , and pathos .

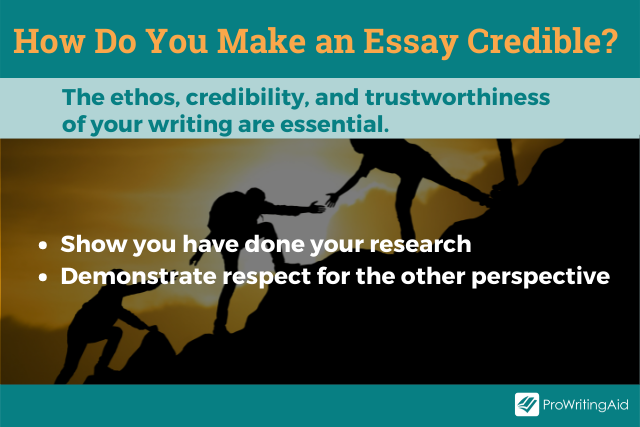

Ethos relates to credibility and trustworthiness. How can you, as the writer, demonstrate your credibility as a source of information to your audience?

How will you show them you are worthy of their trust?

- You show you’ve done your research: you understand the issue, both sides

- You show respect for the opposing side: if you disrespect your audience, they won’t respect you or your ideas

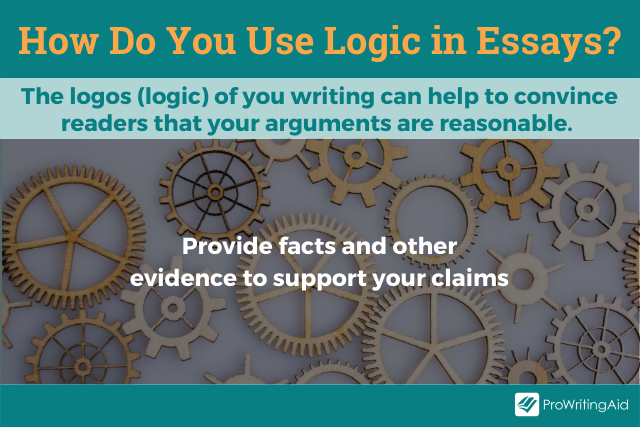

Logos relates to logic. How will you convince your audience that your arguments and ideas are reasonable?

You provide facts or other supporting evidence to support your claims.

That evidence may take the form of studies or expert input or reasonable examples or a combination of all of those things, depending on the specific requirements of your assignment.

Remember: if you use someone else’s ideas or words in your essay, you need to give them credit.

ProWritingAid's Plagiarism Checker checks your work against over a billion web-pages, published works, and academic papers so you can be sure of its originality.

Find out more about ProWritingAid’s Plagiarism checks.

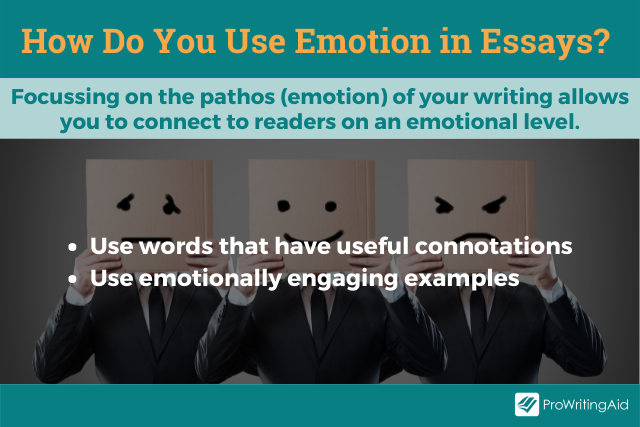

Pathos relates to emotion. Audiences are people and people are emotional beings. We respond to emotional prompts. How will you engage your audience with your arguments on an emotional level?

- You make strategic word choices : words have denotations (dictionary meanings) and also connotations, or emotional values. Use words whose connotations will help prompt the feelings you want your audience to experience.

- You use emotionally engaging examples to support your claims or make a point, prompting your audience to be moved by your discussion.

Be mindful as you lean into elements of the triangle. Too much pathos and your audience might end up feeling manipulated, roll their eyes and move on.

An “all logos” approach will leave your essay dry and without a sense of voice; it will probably bore your audience rather than make them care.

Once you’ve got your essay planned, start writing! Don’t worry about perfection, just get your ideas out of your head and off your list and into a rough essay format.

After you’ve written your draft, evaluate your work. What works and what doesn’t? For help with evaluating and revising your work, check out this ProWritingAid post on manuscript revision .

After you’ve evaluated your draft, revise it. Repeat that process as many times as you need to make your work the best it can be.

When you’re satisfied with the content and structure of the essay, take it through the editing process .

Grammatical or sentence-level errors can distract your audience or even detract from the ethos—the authority—of your work.

You don’t have to edit alone! ProWritingAid’s Realtime Report will find errors and make suggestions for improvements.

You can even use it on emails to your professors:

Try ProWritingAid with a free account.

How Can I Improve My Persuasion Skills?

You can develop your powers of persuasion every day just by observing what’s around you.

- How is that advertisement working to convince you to buy a product?

- How is a political candidate arguing for you to vote for them?

- How do you “argue” with friends about what to do over the weekend, or convince your boss to give you a raise?

- How are your parents working to convince you to follow a certain academic or career path?

As you observe these arguments in action, evaluate them. Why are they effective or why do they fail?

How could an argument be strengthened with more (or less) emphasis on ethos, logos, and pathos?

Every argument is an opportunity to learn! Observe them, evaluate them, and use them to perfect your own powers of persuasion.

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Allison Bressmer is a professor of freshman composition and critical reading at a community college and a freelance writer. If she isn’t writing or teaching, you’ll likely find her reading a book or listening to a podcast while happily sipping a semi-sweet iced tea or happy-houring with friends. She lives in New York with her family. Connect at linkedin.com/in/allisonbressmer.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

8.7: Tips for Writing Academic Persuasive Essays

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 250473

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

The previous chapters in this section offer an overview of what it means to formulate an argument in an academic situation. The purpose of this chapter is to offer more concrete, actionable tips for drafting an academic persuasive essay. Keep in mind that preparing to draft a persuasive essay relies on the strategies for any other thesis-driven essay, covered by the section in this textbook, The Writing Process. The following chapters can be read in concert with this one:

- Critical Reading and other research strategies helps writers identify the exigence (issue) that demands a response, as well as what kinds of research to use.

- Generate Ideas covers prewriting models (such as brainstorming techniques) that allow students to make interesting connections and develop comprehensive thesis statements. These connections and main points will allow a writer to outline their core argument.

- Organizing is important for understanding why an argument essay needs a detailed plan, before the drafting stage. For an argument essay, start with a basic outline that identifies the claim, reasoning, and evidence, but be prepared to develop more detailed outlines that include counterarguments and rebuttals, warrants, additional backing, etc., as needed.

- Drafting introduces students to basic compositional strategies that they must be familiar with before beginning an argument essay. This current chapter offers more details about what kinds of paragraphs to practice in an argument essay, but it assumes the writer is familiar with basic strategies such as coherence and cohesion.

Classical structure of an argument essay

Academic persuasive essays tend to follow what’s known as the “classical” structure, based on techniques that derive from ancient Roman and Medieval rhetoricians. John D. Ramage, et. al outline this structure in Writing Arguments :

| Introduction (one to several paragraphs) | ||

| Presentation of writer’s position | ||

| Summary of opposing views (Counterarguments) Response to opposing views (Rebuttals) | ||

| Conclusion |

This very detailed table can be simplified. Most academic persuasive essays include the following basic elements:

- Introduction that explains why the situation is important and presents your argument (aka the claim or thesis).

- Reasons the thesis is correct or at least reasonable.

- Evidence that supports each reason, often occurring right after the reason the evidence supports.

- Acknowledgement of objections.

- Response to objections.

Keep in mind that the structure above is just a conventional starting point. The previous chapters of this section suggest how different kinds of arguments (Classical/Aristotelian, Toulmin, Rogerian) involve slightly different approaches, and your course, instructor, and specific assignment prompt may include its own specific instructions on how to complete the assignment. There are many different variations. At the same time, however, most academic argumentative/persuasive essays expect you to practice the techniques mentioned below. These tips overlap with the elements of argumentation, covered in that chapter, but they offer more explicit examples for how they might look in paragraph form, beginning with the introduction to your essay.

Persuasive introductions should move from context to thesis

Since one of the main goals of a persuasive essay introduction is to forecast the broader argument, it’s important to keep in mind that the legibility of the argument depends on the ability of the writer to provide sufficient information to the reader. If a basic high school essay moves from general topic to specific argument (the funnel technique), a more sophisticated academic persuasive essay is more likely to move from context to thesis.

The great stylist of clear writing, Joseph W. Williams, suggests that one of the key rhetorical moves a writer can make in a persuasive introduction is to not only provide enough background information (the context), but to frame that information in terms of a problem or issue, what the section on Reading and Writing Rhetorically terms the exigence . The ability to present a clearly defined problem and then the thesis as a solution creates a motivating introduction. The reader is more likely to be gripped by it, because we naturally want to see problems solved.

Consider these two persuasive introductions, both of which end with an argumentative thesis statement:

A. In America we often hold to the belief that our country is steadily progressing. topic This is a place where dreams come true. With enough hard work, we tell ourselves (and our children), we can do anything. I argue that, when progress is more carefully defined, our current period is actually one of decline. claim

B . Two years ago my dad developed Type 2 diabetes, and the doctors explained to him that it was due in large part to his heavy consumption of sugar. For him, the primary form of sugar consumption was soda. hook His experience is echoed by millions of Americans today. According to the most recent research, “Sugary drink portion sizes have risen dramatically over the past forty years, and children and adults are drinking more soft drinks than ever,” while two out of three adults in the United States are now considered either overweight or obese. This statistic correlates with reduced life expectancy by many years. Studies have shown that those who are overweight in this generation will live a lot fewer years than those who are already elderly. And those consumers who don’t become overweight remain at risk for developing Type 2 diabetes (like my dad), known as one of the most serious global health concerns (“Sugary Drinks and Obesity Fact Sheet”). problem In response to this problem, some political journalists, such as Alexandra Le Tellier, argue that sodas should be banned. On the opposite end of the political spectrum, politically conservative journalists such as Ernest Istook argue that absolutely nothing should be done because that would interfere with consumer freedom. debate I suggest something in between: a “soda tax,” which would balance concerns over the public welfare with concerns over consumer freedom. claim

Example B feels richer, more dramatic, and much more targeted not only because it’s longer, but because it’s structured in a “motivating” way. Here’s an outline of that structure:

- Hook: It opens with a brief hook that illustrates an emerging issue. This concrete, personal anecdote grips the reader’s attention.

- Problem: The anecdote is connected with the emerging issue, phrased as a problem that needs to be addressed.

- Debate: The writer briefly alludes to a debate over how to respond to the problem.

- Claim: The introduction ends by hinting at how the writer intends to address the problem, and it’s phrased conversationally, as part of an ongoing dialogue.

Not every persuasive introduction needs all of these elements. Not all introductions will have an obvious problem. Sometimes a “problem,” or the exigence, will be as subtle as an ambiguity in a text that needs to be cleared up (as in literary analysis essays). Other times it will indeed be an obvious problem, such as in a problem-solution argument essay.

In most cases, however, a clear introduction will proceed from context to thesis . The most attention-grabbing and motivating introductions will also include things like hooks and problem-oriented issues.

Here’s a very simple and streamlined template that can serve as rudimentary scaffolding for a persuasive introduction, inspired by the excellent book, They Say / I Say: The Moves That Matter in Academic Writing : Definition: Term

In discussions of __________, an emerging issue is _____________________. issue When addressing this issue, some experts suggest ________________. debate In my view, however, _______________________________. claim

Each aspect of the template will need to be developed, but it can serve as training wheels for how to craft a nicely structured context-to-thesis introduction, including things like an issue, debate, and claim. You can try filling in the blanks below, and then export your attempt as a document.

Define key terms, as needed

Much of an academic persuasive essay is dedicated to supporting the claim. A traditional thesis-driven essay has an introduction, body, and conclusion, and the support constitutes much of the body. In a persuasive essay, most of the support is dedicated to reasoning and evidence (more on that below). However, depending on what your claim does, a careful writer may dedicate the beginning (or other parts of the essay body) to defining key terms.

Suppose I wish to construct an argument that enters the debate over euthanasia. When researching the issue, I notice that much of the debate circles around the notion of rights, specifically what a “legal right” actually means. Clearly defining that term will help reduce some of the confusion and clarify my own argument. In Vancouver Island University’s resource “ Defining key terms ,” Ian Johnston offers this example for how to define “legal right” for an academic reader:

Before discussing the notion of a right to die, we need to clarify precisely what the term legal right means. In common language, the term “right” tends often to mean something good, something people ought to have (e.g., a right to a good home, a right to a meaningful job, and so on). In law, however, the term has a much more specific meaning. It refers to something to which people are legally entitled. Thus, a “legal” right also confers a legal obligation on someone or some institution to make sure the right is conferred. For instance, in Canada, children of a certain age have a right to a free public education. This right confers on society the obligation to provide that education, and society cannot refuse without breaking the law. Hence, when we use the term right to die in a legal sense, we are describing something to which a citizen is legally entitled, and we are insisting that someone in society has an obligation to provide the services which will confer that right on anyone who wants it.

As the example above shows, academics often dedicate space to providing nuanced and technical definitions that correct common misconceptions. Johnston’s definition relies on research, but it’s not always necessary to use research to define your terms. Here are some tips for crafting definitions in persuasive essays, from “Defining key terms”:

- Fit the descriptive detail in the definition to the knowledge of the intended audience. The definition of, say, AIDS for a general readership will be different from the definition for a group of doctors (the latter will be much more technical). It often helps to distinguish between common sense or popular definitions and more technical ones.

- Make sure definitions are full and complete; do not rush them unduly. And do not assume that just because the term is quite common that everyone knows just what it means (e.g., alcoholism ). If you are using the term in a very specific sense, then let the reader know what that is. The amount of detail you include in a definition should cover what is essential for the reader to know, in order to follow the argument. By the same token, do not overload the definition, providing too much detail or using far too technical a language for those who will be reading the essay.

- It’s unhelpful to simply quote the google or dictionary.com definition of a word. Dictionaries contain a few or several definitions for important terms, and the correct definition is informed by the context in which it’s being employed. It’s up to the writer to explain that context and how the word is usually understood within it.

- You do not always need to research a definition. Depending on the writing situation and audience, you may be able to develop your own understanding of certain terms.

Use P-E-A-S or M-E-A-L to support your claim

The heart of a persuasive essay is a claim supported by reasoning and evidence. Thus, much of the essay body is often devoted to the supporting reasons, which in turn are proved by evidence. One of the formulas commonly taught in K-12 and even college writing programs is known as PEAS, which overlaps strongly with the MEAL formula introduced by the chapter, “ Basic Integration “:

Point : State the reasoning as a single point: “One reason why a soda tax would be effective is that…” or “One way an individual can control their happiness is by…”

Evidence : After stating the supporting reason, prove that reason with related evidence. There can be more than one piece of evidence. “According to …” or “In the article, ‘…,’ the author shows that …”

Analysis : There a different levels of analysis. At the most basic level, a writer should clearly explain how the evidence proves the point, in their own words: “In other words…,” “What this data shows is that…” Sometimes the “A” part of PEAS becomes simple paraphrasing. Higher-level analysis will use more sophisticated techniques such as Toulmin’s warrants to explore deeper terrain. For more tips on how to discuss and analyze, refer to the previous chapter’s section, “ Analyze and discuss the evidence .”

Summary/So what? : Tie together all of the components (PEA) succinctly, before transitioning to the next idea. If necessary, remind the reader how the evidence and reasoning relates to the broader claim (the thesis argument).

PEAS and MEAL are very similar; in fact they are identical except for how they refer to the first and last part. In theory, it shouldn’t matter which acronym you choose. Both versions are effective because they translate the basic structure of a supporting reason (reasoning and evidence) into paragraph form.

Here’s an example of a PEAS paragraph in an academic persuasive essay that argues for a soda tax:

A soda tax would also provide more revenue for the federal government, thereby reducing its debt. point Despite Ernest Istook’s concerns about eroding American freedom, the United States has long supported the ability of government to leverage taxes in order to both curb unhealthy lifestyles and add revenue. According to Peter Ubel’s “Would the Founding Fathers Approve of a Sugar Tax?”, in 1791 the US government was heavily in debt and needed stable revenue. In response, the federal government taxed what most people viewed as a “sin” at that time: alcohol. This single tax increased government revenue by at least 20% on average, and in some years more than 40% . The effect was that only the people who really wanted alcohol purchased it, and those who could no longer afford it were getting rid of what they already viewed as a bad habit (Ubel). evidence Just as alcohol (and later, cigarettes) was viewed as a superfluous “sin” in the Early Republic, so today do many health experts and an increasing amount of Americans view sugar as extremely unhealthy, even addictive. If our society accepts taxes on other consumer sins as a way to improve government revenue, a tax on sugar is entirely consistent. analysis We could apply this to the soda tax and try to do something like this to help knock out two problems at once: help people lose their addiction towards soda and help reduce our government’s debt. summary/so what?

The paragraph above was written by a student who was taught the PEAS formula. However, we can see versions of this formula in professional writing. Here’s a more sophisticated example of PEAS, this time from a non-academic article. In Nicholas Carr’s extremely popular article, “ Is Google Making Us Stupid? “, he argues that Google is altering how we think. To prove that broader claim, Carr offers a variety of reasons and evidence. Here’s part of his reasoning:

Thanks to the ubiquity of text on the Internet, not to mention the popularity of text-messaging on cell phones, we may well be reading more today than we did in the 1970s or 1980s, when television was our medium of choice. But it’s a different kind of reading, and behind it lies a different kind of thinking—perhaps even a new sense of the self. point “We are not only what we read,” says Maryanne Wolf, a developmental psychologist at Tufts University and the author of Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain . “We are how we read.” Wolf worries that the style of reading promoted by the Net, a style that puts “efficiency” and “immediacy” above all else, may be weakening our capacity for the kind of deep reading that emerged when an earlier technology, the printing press, made long and complex works of prose commonplace. When we read online, she says, we tend to become “mere decoders of information.” evidence Our ability to interpret text, to make the rich mental connections that form when we read deeply and without distraction, remains largely disengaged. analysis

This excerpt only contains the first three elements, PEA, and the analysis part is very brief (it’s more like paraphrase), but it shows how professional writers often employ some version of the formula. It tends to appear in persuasive texts written by experienced writers because it reinforces writing techniques mentioned elsewhere in this textbook. A block of text structured according to PEA will practice coherence, because opening with a point (P) forecasts the main idea of that section. Embedding the evidence (E) within a topic sentence and follow-up commentary or analysis (A) is part of the “quote sandwich” strategy we cover in the section on “Writing With Sources.”

Use “they say / i say” strategies for Counterarguments and rebuttals

Another element that’s unique to persuasive essays is embedding a counterargument. Sometimes called naysayers or opposing positions, counterarguments are points of view that challenge our own.

Why embed a naysayer?

Recall above how a helpful strategy for beginning a persuasive essay (the introduction) is to briefly mention a debate—what some writing textbooks call “joining the conversation.” Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein’s They Say / I Say explains why engaging other points of view is so crucial:

Not long ago we attended a talk at an academic conference where the speaker’s central claim seemed to be that a certain sociologist—call him Dr. X—had done very good work in a number of areas of the discipline. The speaker proceeded to illustrate his thesis by referring extensively and in great detail to various books and articles by Dr. X and by quoting long pas-sages from them. The speaker was obviously both learned and impassioned, but as we listened to his talk we found ourselves somewhat puzzled: the argument—that Dr. X’s work was very important—was clear enough, but why did the speaker need to make it in the first place? Did anyone dispute it? Were there commentators in the field who had argued against X’s work or challenged its value? Was the speaker’s interpretation of what X had done somehow novel or revolutionary? Since the speaker gave no hint of an answer to any of these questions, we could only wonder why he was going on and on about X. It was only after the speaker finished and took questions from the audience that we got a clue: in response to one questioner, he referred to several critics who had vigorously questioned Dr. X’s ideas and convinced many sociologists that Dr. X’s work was unsound.

When writing for an academic audience, one of the most important moves a writer can make is to demonstrate how their ideas compare to others. It serves as part of the context. Your essay might be offering a highly original solution to a certain problem you’ve researched the entire semester, but the reader will only understand that if existing arguments are presented in your draft. Or, on the other hand, you might be synthesizing or connecting a variety of opinions in order to arrive at a more comprehensive solution. That’s also fine, but the creativity of your synthesis and its unique contribution to existing research will only be known if those other voices are included.

Aristotelian argumentation embeds counterarguments in order to refute them. Rogerian arguments present oppositional stances in order to synthesize and integrate them. No matter what your strategy is, the essay should be conversational.

Notice how Ana Mari Cauce opens her essay on free speech in higher education, “ Messy but Essential “:

Over the past year or two, issues surrounding the exercise of free speech and expression have come to the forefront at colleges around the country. The common narrative about free speech issues that we so often read goes something like this: today’s college students — overprotected and coddled by parents, poorly educated in high school and exposed to primarily left-leaning faculty — have become soft “snowflakes” who are easily offended by mere words and the slightest of insults, unable or unwilling to tolerate opinions that veer away from some politically correct orthodoxy and unable to engage in hard-hitting debate. counterargument

This is false in so many ways, and even insulting when you consider the reality of students’ experiences today. claim

The introduction to her article is essentially a counteragument (which serves as her introductory context) followed by a response. Embedding naysayers like this can appear anywhere in an essay, not just the introduction. Notice, furthermore, how Cauce’s naysayer isn’t gleaned from any research she did. It’s just a general, trendy naysayer, something one might hear nowadays, in the ether. It shows she’s attuned to an ongoing conversation, but it doesn’t require her to cite anything specific. As the previous chapter on using rhetorical appeals in arguments explained, this kind of attunement with an emerging problem (or exigence) is known as the appeal to kairos . A compelling, engaging introduction will demonstrate that the argument “kairotically” addresses a pressing concern.

Below is a brief overview of what counterarguments are and how you might respond to them in your arguments. This section was developed by Robin Jeffrey, in “ Counterargument and Response “:

Common Types of counterarguments

- Could someone disagree with your claim? If so, why? Explain this opposing perspective in your own argument, and then respond to it.

- Could someone draw a different conclusion from any of the facts or examples you present? If so, what is that different conclusion? Explain this different conclusion and then respond to it.

- Could a reader question any of your assumptions or claims? If so, which ones would they question? Explain and then respond.

- Could a reader offer a different explanation of an issue? If so, what might their explanation be? Describe this different explanation, and then respond to it.

- Is there any evidence out there that could weaken your position? If so, what is it? Cite and discuss this evidence and then respond to it.

If the answer to any of these questions is yes, that does not necessarily mean that you have a weak argument. It means, ideally and as long as your argument is logical and valid, that you have a counterargument. Good arguments can and do have counterarguments; it is important to discuss them. But you must also discuss and then respond to those counterarguments.

Responding to counterarguments

You do not need to attempt to do all of these things as a way to respond; instead, choose the response strategy that makes the most sense to you, for the counterargument that you have.

- If you agree with some of the counterargument perspectives, you can concede some of their points. (“I do agree that ….”, “Some of the points made by ____ are valid…..”) You could then challenge the importance/usefulness of those points. “However, this information does not apply to our topic because…”

- If the counterargument perspective is one that contains different evidence than you have in your own argument, you can explain why a reader should not accept the evidence that the counterarguer presents.

- If the counterargument perspective is one that contains a different interpretation of evidence than you have in your own argument, you can explain why a reader should not accept the interpretation of the evidence that that your opponent (counterarguer) presents.

- If the counterargument is an acknowledgement of evidence that threatens to weaken your argument, you must explain why and how that evidence does not, in fact invalidate your claim.

It is important to use transitional phrases in your paper to alert readers when you’re about to present an counterargument. It’s usually best to put this phrase at the beginning of a paragraph such as:

- Researchers have challenged these claims with…

- Critics argue that this view…

- Some readers may point to…

- A perspective that challenges the idea that . . .

Transitional phrases will again be useful to highlight your shift from counterargument to response:

- Indeed, some of those points are valid. However, . . .

- While I agree that . . . , it is more important to consider . . .

- These are all compelling points. Still, other information suggests that . .

- While I understand . . . , I cannot accept the evidence because . . .

Further reading

To read more about the importance of counterarguments in academic writing, read Steven D. Krause’s “ On the Other Hand: The Role of Antithetical Writing in First Year Composition Courses .”

When concluding, address the “so what?” challenge

As Joseph W. Williams mentions in his chapter on concluding persuasive essays in Style ,

a good introduction motivates your readers to keep reading, introduces your key themes, and states your main point … [but] a good conclusion serves a different end: as the last thing your reader reads, it should bring together your point, its significance, and its implications for thinking further about the ideas your explored.

At the very least, a good persuasive conclusion will

- Summarize the main points

- Address the So what? or Now what? challenge.

When summarizing the main points of longer essays, Williams suggests it’s fine to use “metadiscourse,” such as, “I have argued that.” If the essay is short enough, however, such metadiscourses may not be necessary, since the reader will already have those ideas fresh in their mind.

After summarizing your essay’s main points, imagine a friendly reader thinking,

“OK, I’m persuaded and entertained by everything you’ve laid out in your essay. But remind me what’s so important about these ideas? What are the implications? What kind of impact do you expect your ideas to have? Do you expect something to change?”

It’s sometimes appropriate to offer brief action points, based on the implications of your essay. When addressing the “So what?” challenge, however, it’s important to first consider whether your essay is primarily targeted towards changing the way people think or act . Do you expect the audience to do something, based on what you’ve argued in your essay? Or, do you expect the audience to think differently? Traditional academic essays tend to propose changes in how the reader thinks more than acts, but your essay may do both.

Finally, Williams suggests that it’s sometimes appropriate to end a persuasive essay with an anecdote, illustrative fact, or key quote that emphasizes the significance of the argument. We can see a good example of this in Carr’s article, “ Is Google Making Us Stupid? ” Here are the introduction and conclusion, side-by-side: Definition: Term

[Introduction] “Dave, stop. Stop, will you? Stop, Dave. Will you stop, Dave?” So the supercomputer HAL pleads with the implacable astronaut Dave Bowman in a famous and weirdly poignant scene toward the end of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey . Bowman, having nearly been sent to a deep-space death by the malfunctioning machine, is calmly, coldly disconnecting the memory circuits that control its artificial “ brain. “Dave, my mind is going,” HAL says, forlornly. “I can feel it. I can feel it.”

I can feel it, too. Over the past few years I’ve had an uncomfortable sense that someone, or something, has been tinkering with my brain, remapping the neural circuitry, reprogramming the memory. …

[Conclusion] I’m haunted by that scene in 2001 . What makes it so poignant, and so weird, is the computer’s emotional response to the disassembly of its mind: its despair as one circuit after another goes dark, its childlike pleading with the astronaut—“I can feel it. I can feel it. I’m afraid”—and its final reversion to what can only be called a state of innocence. HAL’s outpouring of feeling contrasts with the emotionlessness that characterizes the human figures in the film, who go about their business with an almost robotic efficiency. Their thoughts and actions feel scripted, as if they’re following the steps of an algorithm. In the world of 2001 , people have become so machinelike that the most human character turns out to be a machine. That’s the essence of Kubrick’s dark prophecy: as we come to rely on computers to mediate our understanding of the world, it is our own intelligence that flattens into artificial intelligence.

Instead of merely rehashing all of the article’s main points, Carr returns to the same movie scene from 2001 that he opened with. The final lines interpret the scene according to the argument he just dedicated the entire essay to presenting.

The entire essay should use rhetorical appeals strategically

The chapter “ Persuasive Appeals ” introduces students to logos, pathos, ethos, and kairos. Becoming familiar with each of those persuasive appeals can add much to an essay. It also reinforces the idea that writing argumentative essays is not a straightforward process of jotting down proofs. It’s not a computer algorithm.

- Logos (appeals to evidence and reasoning) is the foundational appeal of an argument essay. Clearly identifying the claim, then supporting that claim with reasoning and evidence will appeal to the reader’s logos demands. As the previous chapter on argumentation mentions, however, what constitutes solid evidence will vary depending on the audience. Make sure your evidence is indeed convincing to your intended reader.

- Pathos (appeals to emotion) are a crucial component and should permeate should every section of the essay. Personal anecdotes are an effective way to illustrate important ideas, and they connect with the reader at an emotional level. Personal examples also cultivate voice .

- Ethos (appeals to character, image, and values) is essential to gaining the reader’s trust and assent. The tone of your essay (snarky, sincere, ironic, sarcastic, empathetic) is immensely important for its overall effect, and it helps build the reader’s image of you. A careful attention to high-quality research reinforces a sincere and empathetic tone. When supporting certain claims and sub-claims, it’s also important to identify implied beliefs (warrants) that your reader is most likely to agree with, and to undermine beliefs that might seem repugnant.

- Kairos (appeals to timeliness) impresses the reader with your attunement to the situation. This should be practiced especially in the introduction, but it can appear throughout the essay as you engage with research and other voices that have recently weighed in on the topic.

All of these appeals are already happening, whether or not they’re recognized. If they are missed, the audience will often use them against you, judging your essay as not being personable enough (pathos), or not in touch with commonly accepted values (ethos), or out of touch with what’s going on (kairos). These non-logical appeals aren’t irrational. They are crucial components to writing that matters.

Argument Outline Exercise

To get started on your argument essay, practice adopting from of the outlines from this Persuasive Essay Outline worksheet .

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

How to Write a Persuasive Essay

Last Updated: December 17, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Christopher Taylor, PhD . Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014. There are 14 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 4,279,923 times.

A persuasive essay is an essay used to convince a reader about a particular idea or focus, usually one that you believe in. Your persuasive essay could be based on anything about which you have an opinion or that you can make a clear argument about. Whether you're arguing against junk food at school or petitioning for a raise from your boss, knowing how to write a persuasive essay is an important skill that everyone should have.

Sample Persuasive Essays

How to Lay the Groundwork

- Look for language that gives you a clue as to whether you are writing a purely persuasive or an argumentative essay. For example, if the prompt uses words like “personal experience” or “personal observations,” you know that these things can be used to support your argument.

- On the other hand, words like “defend” or “argue” suggest that you should be writing an argumentative essay, which may require more formal, less personal evidence.

- If you aren’t sure about what you’re supposed to write, ask your instructor.

- Whenever possible, start early. This way, even if you have emergencies like a computer meltdown, you’ve given yourself enough time to complete your essay.

- Try using stasis theory to help you examine the rhetorical situation. This is when you look at the facts, definition (meaning of the issue or the nature of it), quality (the level of seriousness of the issue), and policy (plan of action for the issue).

- To look at the facts, try asking: What happened? What are the known facts? How did this issue begin? What can people do to change the situation?

- To look at the definition, ask: What is the nature of this issue or problem? What type of problem is this? What category or class would this problem fit into best?

- To examine the quality, ask: Who is affected by this problem? How serious is it? What might happen if it is not resolved?

- To examine the policy, ask: Should someone take action? Who should do something and what should they do?

- For example, if you are arguing against unhealthy school lunches, you might take very different approaches depending on whom you want to convince. You might target the school administrators, in which case you could make a case about student productivity and healthy food. If you targeted students’ parents, you might make a case about their children’s health and the potential costs of healthcare to treat conditions caused by unhealthy food. And if you were to consider a “grassroots” movement among your fellow students, you’d probably make appeals based on personal preferences.

- It also should present the organization of your essay. Don’t list your points in one order and then discuss them in a different order.

- For example, a thesis statement could look like this: “Although pre-prepared and highly processed foods are cheap, they aren’t good for students. It is important for schools to provide fresh, healthy meals to students, even when they cost more. Healthy school lunches can make a huge difference in students’ lives, and not offering healthy lunches fails students.”

- Note that this thesis statement isn’t a three-prong thesis. You don’t have to state every sub-point you will make in your thesis (unless your prompt or assignment says to). You do need to convey exactly what you will argue.

- A mind map could be helpful. Start with your central topic and draw a box around it. Then, arrange other ideas you think of in smaller bubbles around it. Connect the bubbles to reveal patterns and identify how ideas relate. [5] X Research source

- Don’t worry about having fully fleshed-out ideas at this stage. Generating ideas is the most important step here.

- For example, if you’re arguing for healthier school lunches, you could make a point that fresh, natural food tastes better. This is a personal opinion and doesn’t need research to support it. However, if you wanted to argue that fresh food has more vitamins and nutrients than processed food, you’d need a reliable source to support that claim.

- If you have a librarian available, consult with him or her! Librarians are an excellent resource to help guide you to credible research.

How to Draft Your Essay

- An introduction. You should present a “hook” here that grabs your audience’s attention. You should also provide your thesis statement, which is a clear statement of what you will argue or attempt to convince the reader of.

- Body paragraphs. In 5-paragraph essays, you’ll have 3 body paragraphs. In other essays, you can have as many paragraphs as you need to make your argument. Regardless of their number, each body paragraph needs to focus on one main idea and provide evidence to support it. These paragraphs are also where you refute any counterpoints that you’ve discovered.

- Conclusion. Your conclusion is where you tie it all together. It can include an appeal to emotions, reiterate the most compelling evidence, or expand the relevance of your initial idea to a broader context. Because your purpose is to persuade your readers to do/think something, end with a call to action. Connect your focused topic to the broader world.

- For example, you could start an essay on the necessity of pursuing alternative energy sources like this: “Imagine a world without polar bears.” This is a vivid statement that draws on something that many readers are familiar with and enjoy (polar bears). It also encourages the reader to continue reading to learn why they should imagine this world.

- You may find that you don’t immediately have a hook. Don’t get stuck on this step! You can always press on and come back to it after you’ve drafted your essay.

- Put your hook first. Then, proceed to move from general ideas to specific ideas until you have built up to your thesis statement.

- Don't slack on your thesis statement . Your thesis statement is a short summary of what you're arguing for. It's usually one sentence, and it's near the end of your introductory paragraph. Make your thesis a combination of your most persuasive arguments, or a single powerful argument, for the best effect.

- Start with a clear topic sentence that introduces the main point of your paragraph.

- Make your evidence clear and precise. For example, don't just say: "Dolphins are very smart animals. They are widely recognized as being incredibly smart." Instead, say: "Dolphins are very smart animals. Multiple studies found that dolphins worked in tandem with humans to catch prey. Very few, if any, species have developed mutually symbiotic relationships with humans."

- "The South, which accounts for 80% of all executions in the United States, still has the country's highest murder rate. This makes a case against the death penalty working as a deterrent."

- "Additionally, states without the death penalty have fewer murders. If the death penalty were indeed a deterrent, why wouldn't we see an increase in murders in states without the death penalty?"

- Consider how your body paragraphs flow together. You want to make sure that your argument feels like it's building, one point upon another, rather than feeling scattered.

- End of the first paragraph: "If the death penalty consistently fails to deter crime, and crime is at an all-time high, what happens when someone is wrongfully convicted?"

- Beginning of the second paragraph: "Over 100 wrongfully convicted death row inmates have been acquitted of their crimes, some just minutes before their would-be death."

- Example: "Critics of a policy allowing students to bring snacks into the classroom say that it would create too much distraction, reducing students’ ability to learn. However, consider the fact that middle schoolers are growing at an incredible rate. Their bodies need energy, and their minds may become fatigued if they go for long periods without eating. Allowing snacks in the classroom will actually increase students’ ability to focus by taking away the distraction of hunger.”

- You may even find it effective to begin your paragraph with the counterargument, then follow by refuting it and offering your own argument.

- How could this argument be applied to a broader context?

- Why does this argument or opinion mean something to me?

- What further questions has my argument raised?

- What action could readers take after reading my essay?

How to Write Persuasively

- Persuasive essays, like argumentative essays, use rhetorical devices to persuade their readers. In persuasive essays, you generally have more freedom to make appeals to emotion (pathos), in addition to logic and data (logos) and credibility (ethos). [13] X Trustworthy Source Read Write Think Online collection of reading and writing resources for teachers and students. Go to source

- You should use multiple types of evidence carefully when writing a persuasive essay. Logical appeals such as presenting data, facts, and other types of “hard” evidence are often very convincing to readers.

- Persuasive essays generally have very clear thesis statements that make your opinion or chosen “side” known upfront. This helps your reader know exactly what you are arguing. [14] X Research source

- Bad: The United States was not an educated nation, since education was considered the right of the wealthy, and so in the early 1800s Horace Mann decided to try and rectify the situation.

- For example, you could tell an anecdote about a family torn apart by the current situation in Syria to incorporate pathos, make use of logic to argue for allowing Syrian refugees as your logos, and then provide reputable sources to back up your quotes for ethos.

- Example: Time and time again, the statistics don't lie -- we need to open our doors to help refugees.

- Example: "Let us not forget the words etched on our grandest national monument, the Statue of Liberty, which asks that we "Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” There is no reason why Syrians are not included in this.

- Example: "Over 100 million refugees have been displaced. President Assad has not only stolen power, he's gassed and bombed his own citizens. He has defied the Geneva Conventions, long held as a standard of decency and basic human rights, and his people have no choice but to flee."

- Good: "Time and time again, science has shown that arctic drilling is dangerous. It is not worth the risks environmentally or economically."

- Good: "Without pushing ourselves to energy independence, in the arctic and elsewhere, we open ourselves up to the dangerous dependency that spiked gas prices in the 80's."

- Bad: "Arctic drilling may not be perfect, but it will probably help us stop using foreign oil at some point. This, I imagine, will be a good thing."

- Good: Does anyone think that ruining someone’s semester, or, at least, the chance to go abroad, should be the result of a victimless crime? Is it fair that we actively promote drinking as a legitimate alternative through Campus Socials and a lack of consequences? How long can we use the excuse that “just because it’s safer than alcohol doesn’t mean we should make it legal,” disregarding the fact that the worst effects of the drug are not physical or chemical, but institutional?

- Good: We all want less crime, stronger families, and fewer dangerous confrontations over drugs. We need to ask ourselves, however, if we're willing to challenge the status quo to get those results.

- Bad: This policy makes us look stupid. It is not based in fact, and the people that believe it are delusional at best, and villains at worst.

- Good: While people do have accidents with guns in their homes, it is not the government’s responsibility to police people from themselves. If they're going to hurt themselves, that is their right.

- Bad: The only obvious solution is to ban guns. There is no other argument that matters.

How to Polish Your Essay

- Does the essay state its position clearly?

- Is this position supported throughout with evidence and examples?

- Are paragraphs bogged down by extraneous information? Do paragraphs focus on one main idea?

- Are any counterarguments presented fairly, without misrepresentation? Are they convincingly dismissed?

- Are the paragraphs in an order that flows logically and builds an argument step-by-step?

- Does the conclusion convey the importance of the position and urge the reader to do/think something?

- You may find it helpful to ask a trusted friend or classmate to look at your essay. If s/he has trouble understanding your argument or finds things unclear, focus your revision on those spots.

- You may find it helpful to print out your draft and mark it up with a pen or pencil. When you write on the computer, your eyes may become so used to reading what you think you’ve written that they skip over errors. Working with a physical copy forces you to pay attention in a new way.

- Make sure to also format your essay correctly. For example, many instructors stipulate the margin width and font type you should use.

Expert Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://www.grammarly.com/blog/how-to-write-a-persuasive-essay/

- ↑ https://www.hamilton.edu/academics/centers/writing/writing-resources/persuasive-essays

- ↑ https://www.hamilton.edu/writing/writing-resources/persuasive-essays

- ↑ https://www.adelaide.edu.au/writingcentre/sites/default/files/docs/learningguide-mindmapping.pdf

- ↑ https://examples.yourdictionary.com/20-compelling-hook-examples-for-essays.html

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/transitions/

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/common_writing_assignments/argument_papers/rebuttal_sections.html

- ↑ http://www.readwritethink.org/files/resources/lesson_images/lesson56/strategy-definition.pdf

- ↑ https://stlcc.edu/student-support/academic-success-and-tutoring/writing-center/writing-resources/pathos-logos-and-ethos.aspx

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/editing-and-proofreading/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/revising-drafts/

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/the_writing_process/proofreading/proofreading_suggestions.html

About This Article

To write a persuasive essay, start with an attention-grabbing introduction that introduces your thesis statement or main argument. Then, break the body of your essay up into multiple paragraphs and focus on one main idea in each paragraph. Make sure you present evidence in each paragraph that supports the main idea so your essay is more persuasive. Finally, conclude your essay by restating the most compelling, important evidence so you can make your case one last time. To learn how to make your writing more persuasive, keep reading! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Joslyn Graham

Nov 4, 2017

Did this article help you?

Jul 28, 2017

Sep 18, 2017

Jefferson Kenely

Jan 22, 2018

Chloe Myers

Jun 3, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Develop the tech skills you need for work and life

- +44 (0) 207 391 9032

Recent Posts

- Is a Thesis Writing Format Easy? A Comprehensive Guide to Thesis Writing

- The Complete Guide to Copy Editing: Roles, Rates, Skills, and Process

How to Write a Paragraph: Successful Essay Writing Strategies

- Everything You Should Know About Academic Writing: Types, Importance, and Structure

- Concise Writing: Tips, Importance, and Exercises for a Clear Writing Style

- How to Write a PhD Thesis: A Step-by-Step Guide for Success

- How to Use AI in Essay Writing: Tips, Tools, and FAQs

- Copy Editing Vs Proofreading: What’s The Difference?

- How Much Does It Cost To Write A Thesis? Get Complete Process & Tips

- How Much Do Proofreading Services Cost in 2024? Per Word and Hourly Rates With Charts

- Academic News

- Custom Essays

- Dissertation Writing

- Essay Marking

- Essay Writing

- Essay Writing Companies

- Model Essays

- Model Exam Answers

- Oxbridge Essays Updates

- PhD Writing

- Significant Academics

- Student News

- Study Skills

- University Applications

- University Essays

- University Life

- Writing Tips

A Comprehensive Guide on How to Write a Persuasive Essay

Since 2006, oxbridge essays has been the uk’s leading paid essay-writing and dissertation service.

We have helped 10,000s of undergraduate, Masters and PhD students to maximise their grades in essays, dissertations, model-exam answers, applications and other materials. If you would like a free chat about your project with one of our UK staff, then please just reach out on one of the methods below.