Home / Guides / Citation Guides / How to Cite Sources

How to Cite Sources

Here is a complete list for how to cite sources. Most of these guides present citation guidance and examples in MLA, APA, and Chicago.

If you’re looking for general information on MLA or APA citations , the EasyBib Writing Center was designed for you! It has articles on what’s needed in an MLA in-text citation , how to format an APA paper, what an MLA annotated bibliography is, making an MLA works cited page, and much more!

MLA Format Citation Examples

The Modern Language Association created the MLA Style, currently in its 9th edition, to provide researchers with guidelines for writing and documenting scholarly borrowings. Most often used in the humanities, MLA style (or MLA format ) has been adopted and used by numerous other disciplines, in multiple parts of the world.

MLA provides standard rules to follow so that most research papers are formatted in a similar manner. This makes it easier for readers to comprehend the information. The MLA in-text citation guidelines, MLA works cited standards, and MLA annotated bibliography instructions provide scholars with the information they need to properly cite sources in their research papers, articles, and assignments.

- Book Chapter

- Conference Paper

- Documentary

- Encyclopedia

- Google Images

- Kindle Book

- Memorial Inscription

- Museum Exhibit

- Painting or Artwork

- PowerPoint Presentation

- Sheet Music

- Thesis or Dissertation

- YouTube Video

APA Format Citation Examples

The American Psychological Association created the APA citation style in 1929 as a way to help psychologists, anthropologists, and even business managers establish one common way to cite sources and present content.

APA is used when citing sources for academic articles such as journals, and is intended to help readers better comprehend content, and to avoid language bias wherever possible. The APA style (or APA format ) is now in its 7th edition, and provides citation style guides for virtually any type of resource.

Chicago Style Citation Examples

The Chicago/Turabian style of citing sources is generally used when citing sources for humanities papers, and is best known for its requirement that writers place bibliographic citations at the bottom of a page (in Chicago-format footnotes ) or at the end of a paper (endnotes).

The Turabian and Chicago citation styles are almost identical, but the Turabian style is geared towards student published papers such as theses and dissertations, while the Chicago style provides guidelines for all types of publications. This is why you’ll commonly see Chicago style and Turabian style presented together. The Chicago Manual of Style is currently in its 17th edition, and Turabian’s A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations is in its 8th edition.

Citing Specific Sources or Events

- Declaration of Independence

- Gettysburg Address

- Martin Luther King Jr. Speech

- President Obama’s Farewell Address

- President Trump’s Inauguration Speech

- White House Press Briefing

Additional FAQs

- Citing Archived Contributors

- Citing a Blog

- Citing a Book Chapter

- Citing a Source in a Foreign Language

- Citing an Image

- Citing a Song

- Citing Special Contributors

- Citing a Translated Article

- Citing a Tweet

6 Interesting Citation Facts

The world of citations may seem cut and dry, but there’s more to them than just specific capitalization rules, MLA in-text citations , and other formatting specifications. Citations have been helping researches document their sources for hundreds of years, and are a great way to learn more about a particular subject area.

Ever wonder what sets all the different styles apart, or how they came to be in the first place? Read on for some interesting facts about citations!

1. There are Over 7,000 Different Citation Styles

You may be familiar with MLA and APA citation styles, but there are actually thousands of citation styles used for all different academic disciplines all across the world. Deciding which one to use can be difficult, so be sure to ask you instructor which one you should be using for your next paper.

2. Some Citation Styles are Named After People

While a majority of citation styles are named for the specific organizations that publish them (i.e. APA is published by the American Psychological Association, and MLA format is named for the Modern Language Association), some are actually named after individuals. The most well-known example of this is perhaps Turabian style, named for Kate L. Turabian, an American educator and writer. She developed this style as a condensed version of the Chicago Manual of Style in order to present a more concise set of rules to students.

3. There are Some Really Specific and Uniquely Named Citation Styles

How specific can citation styles get? The answer is very. For example, the “Flavour and Fragrance Journal” style is based on a bimonthly, peer-reviewed scientific journal published since 1985 by John Wiley & Sons. It publishes original research articles, reviews and special reports on all aspects of flavor and fragrance. Another example is “Nordic Pulp and Paper Research,” a style used by an international scientific magazine covering science and technology for the areas of wood or bio-mass constituents.

4. More citations were created on EasyBib.com in the first quarter of 2018 than there are people in California.

The US Census Bureau estimates that approximately 39.5 million people live in the state of California. Meanwhile, about 43 million citations were made on EasyBib from January to March of 2018. That’s a lot of citations.

5. “Citations” is a Word With a Long History

The word “citations” can be traced back literally thousands of years to the Latin word “citare” meaning “to summon, urge, call; put in sudden motion, call forward; rouse, excite.” The word then took on its more modern meaning and relevance to writing papers in the 1600s, where it became known as the “act of citing or quoting a passage from a book, etc.”

6. Citation Styles are Always Changing

The concept of citations always stays the same. It is a means of preventing plagiarism and demonstrating where you relied on outside sources. The specific style rules, however, can and do change regularly. For example, in 2018 alone, 46 new citation styles were introduced , and 106 updates were made to exiting styles. At EasyBib, we are always on the lookout for ways to improve our styles and opportunities to add new ones to our list.

Why Citations Matter

Here are the ways accurate citations can help your students achieve academic success, and how you can answer the dreaded question, “why should I cite my sources?”

They Give Credit to the Right People

Citing their sources makes sure that the reader can differentiate the student’s original thoughts from those of other researchers. Not only does this make sure that the sources they use receive proper credit for their work, it ensures that the student receives deserved recognition for their unique contributions to the topic. Whether the student is citing in MLA format , APA format , or any other style, citations serve as a natural way to place a student’s work in the broader context of the subject area, and serve as an easy way to gauge their commitment to the project.

They Provide Hard Evidence of Ideas

Having many citations from a wide variety of sources related to their idea means that the student is working on a well-researched and respected subject. Citing sources that back up their claim creates room for fact-checking and further research . And, if they can cite a few sources that have the converse opinion or idea, and then demonstrate to the reader why they believe that that viewpoint is wrong by again citing credible sources, the student is well on their way to winning over the reader and cementing their point of view.

They Promote Originality and Prevent Plagiarism

The point of research projects is not to regurgitate information that can already be found elsewhere. We have Google for that! What the student’s project should aim to do is promote an original idea or a spin on an existing idea, and use reliable sources to promote that idea. Copying or directly referencing a source without proper citation can lead to not only a poor grade, but accusations of academic dishonesty. By citing their sources regularly and accurately, students can easily avoid the trap of plagiarism , and promote further research on their topic.

They Create Better Researchers

By researching sources to back up and promote their ideas, students are becoming better researchers without even knowing it! Each time a new source is read or researched, the student is becoming more engaged with the project and is developing a deeper understanding of the subject area. Proper citations demonstrate a breadth of the student’s reading and dedication to the project itself. By creating citations, students are compelled to make connections between their sources and discern research patterns. Each time they complete this process, they are helping themselves become better researchers and writers overall.

When is the Right Time to Start Making Citations?

Make in-text/parenthetical citations as you need them.

As you are writing your paper, be sure to include references within the text that correspond with references in a works cited or bibliography. These are usually called in-text citations or parenthetical citations in MLA and APA formats. The most effective time to complete these is directly after you have made your reference to another source. For instance, after writing the line from Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities : “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…,” you would include a citation like this (depending on your chosen citation style):

(Dickens 11).

This signals to the reader that you have referenced an outside source. What’s great about this system is that the in-text citations serve as a natural list for all of the citations you have made in your paper, which will make completing the works cited page a whole lot easier. After you are done writing, all that will be left for you to do is scan your paper for these references, and then build a works cited page that includes a citation for each one.

Need help creating an MLA works cited page ? Try the MLA format generator on EasyBib.com! We also have a guide on how to format an APA reference page .

2. Understand the General Formatting Rules of Your Citation Style Before You Start Writing

While reading up on paper formatting may not sound exciting, being aware of how your paper should look early on in the paper writing process is super important. Citation styles can dictate more than just the appearance of the citations themselves, but rather can impact the layout of your paper as a whole, with specific guidelines concerning margin width, title treatment, and even font size and spacing. Knowing how to organize your paper before you start writing will ensure that you do not receive a low grade for something as trivial as forgetting a hanging indent.

Don’t know where to start? Here’s a formatting guide on APA format .

3. Double-check All of Your Outside Sources for Relevance and Trustworthiness First

Collecting outside sources that support your research and specific topic is a critical step in writing an effective paper. But before you run to the library and grab the first 20 books you can lay your hands on, keep in mind that selecting a source to include in your paper should not be taken lightly. Before you proceed with using it to backup your ideas, run a quick Internet search for it and see if other scholars in your field have written about it as well. Check to see if there are book reviews about it or peer accolades. If you spot something that seems off to you, you may want to consider leaving it out of your work. Doing this before your start making citations can save you a ton of time in the long run.

Finished with your paper? It may be time to run it through a grammar and plagiarism checker , like the one offered by EasyBib Plus. If you’re just looking to brush up on the basics, our grammar guides are ready anytime you are.

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Citation Basics

Harvard Referencing

Plagiarism Basics

Plagiarism Checker

Upload a paper to check for plagiarism against billions of sources and get advanced writing suggestions for clarity and style.

Get Started

- Directories

- What are citations and why should I use them?

- When should I use a citation?

- Why are there so many citation styles?

- Which citation style should I use?

- Chicago Notes Style

- Chicago Author-Date Style

- AMA Style (medicine)

- Bluebook (law)

- Additional Citation Styles

- Built-in Citation Tools

- Quick Citation Generators

- Citation Management Software

- Start Your Research

- Research Guides

- University of Washington Libraries

- Library Guides

- UW Libraries

- Citing Sources

Citing Sources: What are citations and why should I use them?

What is a citation.

Citations are a way of giving credit when certain material in your work came from another source. It also gives your readers the information necessary to find that source again-- it provides an important roadmap to your research process. Whenever you use sources such as books, journals or websites in your research, you must give credit to the original author by citing the source.

Why do researchers cite?

Scholarship is a conversation and scholars use citations not only to give credit to original creators and thinkers, but also to add strength and authority to their own work. By citing their sources, scholars are placing their work in a specific context to show where they “fit” within the larger conversation. Citations are also a great way to leave a trail intended to help others who may want to explore the conversation or use the sources in their own work.

In short, citations

(1) give credit

(2) add strength and authority to your work

(3) place your work in a specific context

(4) leave a trail for other scholars

"Good citations should reveal your sources, not conceal them. They should honeslty reflect the research you conducted." (Lipson 4)

Lipson, Charles. "Why Cite?" Cite Right: A Quick Guide to Citation Styles--MLA, APA, Chicago, the Sciences, Professions, and More . Chicago: U of Chicago, 2006. Print.

What does a citation look like?

Different subject disciplines call for citation information to be written in very specific order, capitalization, and punctuation. There are therefore many different style formats. Three popular citation formats are MLA Style (for humanities articles) and APA or Chicago (for social sciences articles).

MLA style (print journal article):

Whisenant, Warren A. "How Women Have Fared as Interscholastic Athletic Administrators Since the Passage of Title IX." Sex Roles Vol. 49.3 (2003): 179-182.

APA style (print journal article):

Whisenant, W. A. (2003) How Women Have Fared as Interscholastic Athletic Administrators Since the Passage of Title IX. Sex Roles , 49 (3), 179-182.

Chicago style (print journal article):

Whisenant, Warren A. "How Women Have Fared as Interscholastic Athletic Administrators Since the Passage of Title IX." Sex Roles 49, no. 3 (2003): 179-182.

No matter which style you use, all citations require the same basic information:

- Author or Creator

- Container (e.g., Journal or magazine, website, edited book)

- Date of creation or publication

- Publisher

You are most likely to have easy access to all of your citation information when you find it in the first place. Take note of this information up front, and it will be much easier to cite it effectively later.

- << Previous: Basics of Citing

- Next: When should I use a citation? >>

- Last Updated: May 1, 2024 12:48 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uw.edu/research/citations

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- PLoS Comput Biol

- v.14(4); 2018 Apr

Ten simple rules for responsible referencing

Bart penders.

Maastricht University, Care and Public Health Research Institute (CAPHRI), Department of Health, Ethics & Society, Maastricht, the Netherlands

We researchers aim to read and write publications containing high-quality prose, exceptional data, arguments, and conclusions, embedded firmly in existing literature while making abundantly clear what we are adding to it. Through the inclusion of references, we demonstrate the foundation upon which our studies rest as well as how they are different from previous work. That difference can include literature we dispute or disprove, arguments or claims we expand, and new ideas, suggestions, and hypotheses we base upon published work. This leads to the question of how to decide which study or author to cite, and in what way.

Writing manuscripts requires, among so much more, decisions on which previous studies to include and exclude, as well as decisions on how exactly that inclusion takes place. A well-referenced manuscript places the authors’ argument in the proper knowledge context and thereby can support its novelty, its value, and its visibility. Citations link one study to others, creating a web of knowledge that carries meaning and allows other researchers to identify work as relevant in general and relevant to them in particular.

On the one hand, citation practices create value by tying together relevant scientific contributions, regardless of whether they are large or small. In the process, they confer or withhold credit, contributing to the relative status of published work in the literature. On the other hand, citation practices exist in the context of current regimes of evaluating science. While it may go unnoticed in daily writing practices, the act of including a single reference in a study is thus subject to value-based criteria internal to science (e.g., content, relevance, credit) and external to science (e.g., accountability, performance).

Accordingly, referencing is not a neutral act. Citations are a form of scientific currency, actively conferring or denying value. Citing certain sources—and especially citing them often—legitimises ideas, solidifies theories, and establishes claims as facts. References also create transparency by allowing others to retrace your steps. Referencing is thus a moral issue, an issue upon which multiple values in science converge. Citing competitors adds to their profiles, citing papers from a specific journal adds to its impact factor, citing supervisors or lab mates helps build your own profile, and citing the right papers helps establish your familiarity with the field. All of these translate into pressures on scientists to cite specific sources, from peers, editors, and others. Fong and Wilhite demonstrate the abundance of so-called coercive citation practices [ 1 ]. Also, citation-based metrics have proliferated as proxies for quality and impact over the years [ 2 – 4 ], only to be currently subjected to significant and highly relevant critique [ 5 – 8 ]. To cite well, or to reference responsibly, is thus a matter of concern to all scientists.

Here, I offer 10 simple rules for responsible referencing. Scientists as authors produce references, and as readers and reviewers, they assess and evaluate references. Through this symmetrical relationship to literature that all scientists share, they take responsibility for tying together all knowledge it contains. Producing and evaluating references are, however, distinct processes, warranting different responsibilities. Respecting this dual relationship researchers have with literature, the first six rules primarily refer to producing a citation and the responsibilities this entails. The second set of four rules refers to evaluating citations and the meaning they have or acquire once they have become part of a text.

Rule 1: Include relevant citations

All scholarly writing requires a demonstration of the relevance of the questions asked, a display of the methods used, a rationale for the use of materials, and a discussion of issues relevant to the content of the publication. All of these are done, at least in large part, by including citations to relevant previous work. Omitting such references can wrongfully suggest that your own publication is the origin of an idea, a question, a method, or a critique, thereby illegitimately appropriating them. Citations identify where ideas have come from, and consulting the cited works allows readers of your text to study them more closely, as well as to evaluate whether your use of them is appropriate.

A single exception exists when facts, findings, or methods have become part of scientific or scholarly canon. There is no need to include a citation on the claim that DNA is built out of four bases, nor do you have to cite Kjell Kleppe or Kary Mullis every time you use PCR (neither do I right now). However, the decision as to when something truly becomes part of canon can be quite difficult and will include periods of adjustment (with irregular citation) and negotiation (on whether to cite or not).

Rule 2: Read the publications you cite

Citation is not an administrative task. First, a single paper can be cited for multiple reasons, ranging from reported data to methods, and can be cited both positively and negatively in the literature. The only way to identify whether its content is relevant as support for your claim is to read it in full.

Second, the collection of citations included to support your work and argument is one of the elements from which your work draws credibility. The same goes for the citations you include to criticise, dispute, or disprove. As a consequence, a chain is only as strong as its weakest link. The quality of the publication you trust and upon which you confer authority codetermines the quality and credibility of your work. Citation rates, especially on the journal level, do not correspond well to research quality [ 9 ], and they conflate positive and negative citations, not distinguishing authority conferred or authority that is challenged. To cite meaningfully and credibly requires that you consult the content of a publication rather than whether others have cited it, as a criterion for citation.

Rule 3: Cite in accordance with content

If, at some phase in the research, you have decided that a specific study merits citation, the issue of specifically how and where to cite it deserves explicit consideration. Mere inclusion does not suffice. Sources deserve credit for the exact contribution they offer, not their contribution in general. This may mean that you need to cite a single source multiple times throughout your own argument, including explanations or indications why.

A specific way to break Rule 3 is in the form of the so-called ‘Trojan citation’ [ 10 ]. The Trojan citation arises when a publication reporting similar findings to your own is cited in the context of a discussion of a minor issue, ignoring (sometimes deliberately) its key argument or contribution. By focussing on a trivial detail, the Trojan citation obscures the true significance of the cited work. As a consequence, it hides that your work is not as novel as it seems. As a questionable citation practice, a Trojan citation can be used to satisfy reviewers’ or editors’ requests to include a reference to a relevant paper. Alternatively, a Trojan citation may emerge unknowingly when (1) you are unaware of the content of a cited publication (not adhering to Rule 2 creates a very significant risk of being unable to follow Rule 3) or (2) disputes exist in the scientific community or among the authors on the contribution and/or quality of a scientific publication (in which case, Rule 4 will help).

Rule 4: Cite transparently, not neutrally

Citing, even in accordance with content, requires context. This is especially important when it happens as part of the article’s argument. Not all citations are a part of an article’s argument. Citations to data, resources, materials, and established methods require less, if any, context. As part of the argument, however, the mere inclusion of a citation, even when in the right spot, does not convey the value of the reference and, accordingly, the rationale for including it. In a recent editorial, the Nature Genetics editors argued against so-called neutral citation. This citation practice, they argue, appears neutral or procedural yet lacks required displays of context of the cited source or rationale for including [ 11 ]. Rather, citations should mention assessments of value, worth, relevance, or significance in the context of whether findings support or oppose reported data or conclusions.

This flows from the realisation that citations are political, even though that term is rarely used in this context. Researchers can use them to accurately represent, inflate, or deflate contributions, based on (1) whether they are included and (2) whether their contributions are qualified. Context or rationale can be qualified by using the right verbs. The contribution of a specific reference can be inflated or deflated through the absence of or use of the wrong qualifying term (‘the authors suggest’ versus ‘the authors establish’; ‘this excellent study shows’ versus ‘this pilot study shows’). If intentional, it is a form of deception, rewriting the content of scientific canon. If unintentional, it is the result of sloppy writing. Ask yourself why you are citing prior work and which value you are attributing to it, and whether the answers to these questions are accessible to your readers.

Rule 5: Cite yourself when required

In the context of critical discussions of citations and evaluations of citation-based metrics, self-citation has almost become a taboo. It is important to realise, though, that self-citation serves an important function by showing incremental iterative advancement of your work [ 12 ]. As a consequence, your previous work or that of the group in which you are embedded should be cited in accordance with all of the rules above. The amount of acceptable self-citation is very likely to differ between fields; smaller fields (niche fields) are likely to (legitimately) exhibit more.

This does not mean that self-citation is always unproblematic. For instance, excessive self-citation can suggest salami slicing, a publication strategy in which elements of a single study are published separately [ 13 ]. This questionable research practice, in tandem with self-citation, aims to inflate publication and citation metrics.

Rule 6: Prioritise the citations you include

Many journals have restrictions on the number of references authors are allowed to include. The exact number varies per publisher, journal, and article type and can be as low as three (for a correspondence item in Nature ). Even if no reference limit exists, other journals impose a word limit that includes references, effectively also capping the amount of references. Coping with these limits sometimes requires difficult decisions to omit citations you may feel are legitimate or even necessary. In order to deal with this issue and avoid random removal of references, all desired citations require prioritisation. A few rules of thumb, shown in Box 1 , will help decisions on reference priority.

Box 1: Reference prioritisation

‘Ten simple sub-rules for prioritising references’ can help to facilitate prioritisation. In most cases, a subset of the 10 sub-rules will suffice. First, prioritise anew for each publication. Prioritisations cannot (easily) be copied from one study to another. Second, prioritise per section (e.g., introduction, methods, discussion), not across the entire paper. Different sections require different types of support. Third, for the introduction, prioritise reviews, allowing broad context for relevance and aim. Fourth, for the discussion, prioritise empirical papers, allowing detailed accounts of relative contribution. Fifth, prioritise reviewed over un- or prereviewed papers (e.g., editorials, preprints, etc.). Sixth, deprioritise self-citations. Seventh, limit the number of citations to support a specific claim, if necessary, to a single citation. Eighth, move methodological citations to supplementary (online) information. Ninth, in cases of equal relevance, prioritise citation of female first or last authors to help repair gender imbalances in science. Tenth, request the inclusion of additional references with the editors, arguing that you have used all of the previous nine sub-rules.

Rule 7: Evaluate citations as the choices that they are

Research publications are not mere vessels of data or findings. They convey a narrative explaining why questions are worth asking, what their answers may mean, how these answers were reached, why they are to be trusted, and more. They also have a purpose in the sense that they will act as support for other studies to come. Each of the elements of their story is supported by links to other studies, and each of those links is the result of an active choice by the author(s) in the context of the goal they wish to achieve by their inclusion.

At the other end of the narrative, readers assess and evaluate the story constantly, asking whether it could have been told differently. The realisation that narratives can be told differently, supported by other citations to other prior work, does not disqualify them. Both the story and the choice of citations are political choices meant to provide the argument with as much power, credibility, and legitimacy the author(s) can muster. They are tailored to the audience the authors seek to convince: their peers. The choice to include or exclude a reference can only be evaluated in the context of that narrative and the role they play in it. Peritz has provided a classification of citation roles to assist this evaluation [ 14 ].

Rule 8: Evaluate citations in their rhetorical context

Rhetorical strategies serve to convince and persuade. Narratives are but one of the tools that can be used to persuade audiences. Metaphors, numbers, and associations all feature in our research papers as tools to convince our readers. The genre of the scientific article has had centuries to evolve to incorporate many of them, with the goal of convincing readers that the author is right. Bazerman has literally written the book on this [ 15 ] and urges us to consider academic texts and their features as part of social and intellectual endeavours. Citations are a part of the social fabric of science in the sense that through citing specific sources, authors show their allegiance to schools of thought, communities, or, in the context of scientific controversies, which paradigm they consider themselves part of. Other rhetorical uses of citations include explicit citations to notable figures and their work, which can serve as appeals to authority, while long lists of citations can serve as proxies for well-studied subjects.

Consider the following: Authors can describe a field as well-studied and include three references—X, Y, and Z—as support for their claim. Alternatively, they can argue that a field is understudied but that three exceptions exist, i.e., X, Y, and Z. Understanding the value attributed to X, Y, and Z in that particular text requires assessment of the rhetorical strategies of the author(s).

Rule 9: Evaluate citations as framed communication

Authors use words to accomplish things and, in service of those goals, position their work and that of others. They frame prior work in a very specific way, supporting the arguments made. We all do. The positioning of X, Y, and Z either as the norm or as exceptions, as shown in Rule 8, is an example of framing. It is important to recognise such framing and that X, Y, and Z acquire meaning in the text as the result of the frame. There is no frameless communication, as Goffman [ 16 ] demonstrated. All messages and texts contain and require a frame—a structure of definitions and assumptions that help organise coherence, connections, and, ultimately, meaning—or in other words, a perspective on reality.

As a result, a citation is not a neutral line drawn between publications A and B. Rather, the representation of cited article A only acquires meaning in the context of citing in article B. Article A can be framed differently when cited in work B or C. It can be framed as innovative in B or dogmatic in C. Framing usually is not lying or deceiving; it is a normative positioning of evidence in context. Hence, a citation is a careful translation of a source’s relevant elements, which acquire meaning in that context only.

An important consequence of this is that merely counting citations of article A in the literature does not inform us of the value (or many types of value or lack thereof) of article A to the scientific community. This point also appears as the first principle in the Leiden Manifesto, which argues that quantitative metrics can only support qualitative metrics (i.e., reading with an attentive eye for politics, rhetoric, context, and frame—or as adhering to Rules 7–9). The Leiden Manifesto was published by bibliometricians and scholars of research evaluation following the 2014 conference on Science and Technology Indicators in Leiden, the Netherlands. It warns against the abuse of, among other things, citation-based research metrics [ 9 ].

Rule 10: Accept that citation cultures differ across boundaries

Despite critiques of the system, science is organised in such a way that citations continue to act as a currency that is represented as being universal [ 4 ]. However, citation practices are, for the most part, local practices, whether local to laboratories or department or local to disciplines. The average number of citations per paper differs between disciplines, and the way that citations are represented in the text and the value of being cited also differ radically [ 17 ]. What counts as proper citation practice in molecular biology—for instance, the inclusion of multiple references following a statement—is considered unacceptable in research ethics or science policy, in which single references require paragraphs of contextualisation and translation (see Rule 9 ). When reading a paper from an adjacent discipline, respect its different norms and conventions for responsible referencing and proper citation. If you are cited by a scientist from another discipline, assess that act as existing in a (however slightly) different citation culture.

Acknowledgments

I thank Maurice Zeegers and his team, who work on citation analyses, for stimulating me to think about the issue of citation more clearly, deeply, and critically, resulting in the considerations above. I also thank David Shaw for critical comments, moral support, and editorial assistance. As a closing note, as the human being that I am, I too have quite possibly referenced imperfectly in my previous work.

Funding Statement

The work that lead to this publication was, in part, supported by the ZonMW programme Fostering Responsible Research Practices, grant no. 45001005. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Referencing

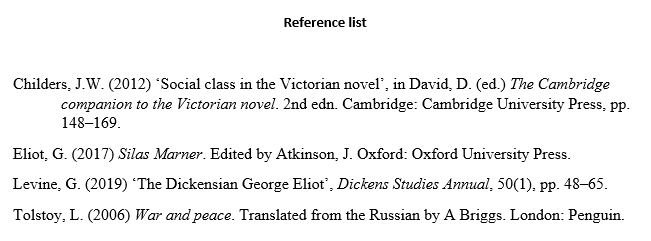

A Quick Guide to Harvard Referencing | Citation Examples

Published on 14 February 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on 15 September 2023.

Referencing is an important part of academic writing. It tells your readers what sources you’ve used and how to find them.

Harvard is the most common referencing style used in UK universities. In Harvard style, the author and year are cited in-text, and full details of the source are given in a reference list .

Harvard Reference Generator

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Harvard in-text citation, creating a harvard reference list, harvard referencing examples, referencing sources with no author or date, frequently asked questions about harvard referencing.

A Harvard in-text citation appears in brackets beside any quotation or paraphrase of a source. It gives the last name of the author(s) and the year of publication, as well as a page number or range locating the passage referenced, if applicable:

Note that ‘p.’ is used for a single page, ‘pp.’ for multiple pages (e.g. ‘pp. 1–5’).

An in-text citation usually appears immediately after the quotation or paraphrase in question. It may also appear at the end of the relevant sentence, as long as it’s clear what it refers to.

When your sentence already mentions the name of the author, it should not be repeated in the citation:

Sources with multiple authors

When you cite a source with up to three authors, cite all authors’ names. For four or more authors, list only the first name, followed by ‘ et al. ’:

Sources with no page numbers

Some sources, such as websites , often don’t have page numbers. If the source is a short text, you can simply leave out the page number. With longer sources, you can use an alternate locator such as a subheading or paragraph number if you need to specify where to find the quote:

Multiple citations at the same point

When you need multiple citations to appear at the same point in your text – for example, when you refer to several sources with one phrase – you can present them in the same set of brackets, separated by semicolons. List them in order of publication date:

Multiple sources with the same author and date

If you cite multiple sources by the same author which were published in the same year, it’s important to distinguish between them in your citations. To do this, insert an ‘a’ after the year in the first one you reference, a ‘b’ in the second, and so on:

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

A bibliography or reference list appears at the end of your text. It lists all your sources in alphabetical order by the author’s last name, giving complete information so that the reader can look them up if necessary.

The reference entry starts with the author’s last name followed by initial(s). Only the first word of the title is capitalised (as well as any proper nouns).

Sources with multiple authors in the reference list

As with in-text citations, up to three authors should be listed; when there are four or more, list only the first author followed by ‘ et al. ’:

Reference list entries vary according to source type, since different information is relevant for different sources. Formats and examples for the most commonly used source types are given below.

- Entire book

- Book chapter

- Translated book

- Edition of a book

Journal articles

- Print journal

- Online-only journal with DOI

- Online-only journal with no DOI

- General web page

- Online article or blog

- Social media post

Sometimes you won’t have all the information you need for a reference. This section covers what to do when a source lacks a publication date or named author.

No publication date

When a source doesn’t have a clear publication date – for example, a constantly updated reference source like Wikipedia or an obscure historical document which can’t be accurately dated – you can replace it with the words ‘no date’:

Note that when you do this with an online source, you should still include an access date, as in the example.

When a source lacks a clearly identified author, there’s often an appropriate corporate source – the organisation responsible for the source – whom you can credit as author instead, as in the Google and Wikipedia examples above.

When that’s not the case, you can just replace it with the title of the source in both the in-text citation and the reference list:

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

Harvard referencing uses an author–date system. Sources are cited by the author’s last name and the publication year in brackets. Each Harvard in-text citation corresponds to an entry in the alphabetised reference list at the end of the paper.

Vancouver referencing uses a numerical system. Sources are cited by a number in parentheses or superscript. Each number corresponds to a full reference at the end of the paper.

A Harvard in-text citation should appear in brackets every time you quote, paraphrase, or refer to information from a source.

The citation can appear immediately after the quotation or paraphrase, or at the end of the sentence. If you’re quoting, place the citation outside of the quotation marks but before any other punctuation like a comma or full stop.

In Harvard referencing, up to three author names are included in an in-text citation or reference list entry. When there are four or more authors, include only the first, followed by ‘ et al. ’

Though the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, there is a difference in meaning:

- A reference list only includes sources cited in the text – every entry corresponds to an in-text citation .

- A bibliography also includes other sources which were consulted during the research but not cited.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, September 15). A Quick Guide to Harvard Referencing | Citation Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 20 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/referencing/harvard-style/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, harvard in-text citation | a complete guide & examples, harvard style bibliography | format & examples, referencing books in harvard style | templates & examples, scribbr apa citation checker.

An innovative new tool that checks your APA citations with AI software. Say goodbye to inaccurate citations!

Loading metrics

Open Access

Ten simple rules for responsible referencing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Maastricht University, Care and Public Health Research Institute (CAPHRI), Department of Health, Ethics & Society, Maastricht, the Netherlands

- Bart Penders

Published: April 12, 2018

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006036

- Reader Comments

Citation: Penders B (2018) Ten simple rules for responsible referencing. PLoS Comput Biol 14(4): e1006036. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006036

Editor: Scott Markel, Dassault Systemes BIOVIA, UNITED STATES

Copyright: © 2018 Bart Penders. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: The work that lead to this publication was, in part, supported by the ZonMW programme Fostering Responsible Research Practices, grant no. 45001005. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

We researchers aim to read and write publications containing high-quality prose, exceptional data, arguments, and conclusions, embedded firmly in existing literature while making abundantly clear what we are adding to it. Through the inclusion of references, we demonstrate the foundation upon which our studies rest as well as how they are different from previous work. That difference can include literature we dispute or disprove, arguments or claims we expand, and new ideas, suggestions, and hypotheses we base upon published work. This leads to the question of how to decide which study or author to cite, and in what way.

Writing manuscripts requires, among so much more, decisions on which previous studies to include and exclude, as well as decisions on how exactly that inclusion takes place. A well-referenced manuscript places the authors’ argument in the proper knowledge context and thereby can support its novelty, its value, and its visibility. Citations link one study to others, creating a web of knowledge that carries meaning and allows other researchers to identify work as relevant in general and relevant to them in particular.

On the one hand, citation practices create value by tying together relevant scientific contributions, regardless of whether they are large or small. In the process, they confer or withhold credit, contributing to the relative status of published work in the literature. On the other hand, citation practices exist in the context of current regimes of evaluating science. While it may go unnoticed in daily writing practices, the act of including a single reference in a study is thus subject to value-based criteria internal to science (e.g., content, relevance, credit) and external to science (e.g., accountability, performance).

Accordingly, referencing is not a neutral act. Citations are a form of scientific currency, actively conferring or denying value. Citing certain sources—and especially citing them often—legitimises ideas, solidifies theories, and establishes claims as facts. References also create transparency by allowing others to retrace your steps. Referencing is thus a moral issue, an issue upon which multiple values in science converge. Citing competitors adds to their profiles, citing papers from a specific journal adds to its impact factor, citing supervisors or lab mates helps build your own profile, and citing the right papers helps establish your familiarity with the field. All of these translate into pressures on scientists to cite specific sources, from peers, editors, and others. Fong and Wilhite demonstrate the abundance of so-called coercive citation practices [ 1 ]. Also, citation-based metrics have proliferated as proxies for quality and impact over the years [ 2 – 4 ], only to be currently subjected to significant and highly relevant critique [ 5 – 8 ]. To cite well, or to reference responsibly, is thus a matter of concern to all scientists.

Here, I offer 10 simple rules for responsible referencing. Scientists as authors produce references, and as readers and reviewers, they assess and evaluate references. Through this symmetrical relationship to literature that all scientists share, they take responsibility for tying together all knowledge it contains. Producing and evaluating references are, however, distinct processes, warranting different responsibilities. Respecting this dual relationship researchers have with literature, the first six rules primarily refer to producing a citation and the responsibilities this entails. The second set of four rules refers to evaluating citations and the meaning they have or acquire once they have become part of a text.

Rule 1: Include relevant citations

All scholarly writing requires a demonstration of the relevance of the questions asked, a display of the methods used, a rationale for the use of materials, and a discussion of issues relevant to the content of the publication. All of these are done, at least in large part, by including citations to relevant previous work. Omitting such references can wrongfully suggest that your own publication is the origin of an idea, a question, a method, or a critique, thereby illegitimately appropriating them. Citations identify where ideas have come from, and consulting the cited works allows readers of your text to study them more closely, as well as to evaluate whether your use of them is appropriate.

A single exception exists when facts, findings, or methods have become part of scientific or scholarly canon. There is no need to include a citation on the claim that DNA is built out of four bases, nor do you have to cite Kjell Kleppe or Kary Mullis every time you use PCR (neither do I right now). However, the decision as to when something truly becomes part of canon can be quite difficult and will include periods of adjustment (with irregular citation) and negotiation (on whether to cite or not).

Rule 2: Read the publications you cite

Citation is not an administrative task. First, a single paper can be cited for multiple reasons, ranging from reported data to methods, and can be cited both positively and negatively in the literature. The only way to identify whether its content is relevant as support for your claim is to read it in full.

Second, the collection of citations included to support your work and argument is one of the elements from which your work draws credibility. The same goes for the citations you include to criticise, dispute, or disprove. As a consequence, a chain is only as strong as its weakest link. The quality of the publication you trust and upon which you confer authority codetermines the quality and credibility of your work. Citation rates, especially on the journal level, do not correspond well to research quality [ 9 ], and they conflate positive and negative citations, not distinguishing authority conferred or authority that is challenged. To cite meaningfully and credibly requires that you consult the content of a publication rather than whether others have cited it, as a criterion for citation.

Rule 3: Cite in accordance with content

If, at some phase in the research, you have decided that a specific study merits citation, the issue of specifically how and where to cite it deserves explicit consideration. Mere inclusion does not suffice. Sources deserve credit for the exact contribution they offer, not their contribution in general. This may mean that you need to cite a single source multiple times throughout your own argument, including explanations or indications why.

A specific way to break Rule 3 is in the form of the so-called ‘Trojan citation’ [ 10 ]. The Trojan citation arises when a publication reporting similar findings to your own is cited in the context of a discussion of a minor issue, ignoring (sometimes deliberately) its key argument or contribution. By focussing on a trivial detail, the Trojan citation obscures the true significance of the cited work. As a consequence, it hides that your work is not as novel as it seems. As a questionable citation practice, a Trojan citation can be used to satisfy reviewers’ or editors’ requests to include a reference to a relevant paper. Alternatively, a Trojan citation may emerge unknowingly when (1) you are unaware of the content of a cited publication (not adhering to Rule 2 creates a very significant risk of being unable to follow Rule 3) or (2) disputes exist in the scientific community or among the authors on the contribution and/or quality of a scientific publication (in which case, Rule 4 will help).

Rule 4: Cite transparently, not neutrally

Citing, even in accordance with content, requires context. This is especially important when it happens as part of the article’s argument. Not all citations are a part of an article’s argument. Citations to data, resources, materials, and established methods require less, if any, context. As part of the argument, however, the mere inclusion of a citation, even when in the right spot, does not convey the value of the reference and, accordingly, the rationale for including it. In a recent editorial, the Nature Genetics editors argued against so-called neutral citation. This citation practice, they argue, appears neutral or procedural yet lacks required displays of context of the cited source or rationale for including [ 11 ]. Rather, citations should mention assessments of value, worth, relevance, or significance in the context of whether findings support or oppose reported data or conclusions.

This flows from the realisation that citations are political, even though that term is rarely used in this context. Researchers can use them to accurately represent, inflate, or deflate contributions, based on (1) whether they are included and (2) whether their contributions are qualified. Context or rationale can be qualified by using the right verbs. The contribution of a specific reference can be inflated or deflated through the absence of or use of the wrong qualifying term (‘the authors suggest’ versus ‘the authors establish’; ‘this excellent study shows’ versus ‘this pilot study shows’). If intentional, it is a form of deception, rewriting the content of scientific canon. If unintentional, it is the result of sloppy writing. Ask yourself why you are citing prior work and which value you are attributing to it, and whether the answers to these questions are accessible to your readers.

Rule 5: Cite yourself when required

In the context of critical discussions of citations and evaluations of citation-based metrics, self-citation has almost become a taboo. It is important to realise, though, that self-citation serves an important function by showing incremental iterative advancement of your work [ 12 ]. As a consequence, your previous work or that of the group in which you are embedded should be cited in accordance with all of the rules above. The amount of acceptable self-citation is very likely to differ between fields; smaller fields (niche fields) are likely to (legitimately) exhibit more.

This does not mean that self-citation is always unproblematic. For instance, excessive self-citation can suggest salami slicing, a publication strategy in which elements of a single study are published separately [ 13 ]. This questionable research practice, in tandem with self-citation, aims to inflate publication and citation metrics.

Rule 6: Prioritise the citations you include

Many journals have restrictions on the number of references authors are allowed to include. The exact number varies per publisher, journal, and article type and can be as low as three (for a correspondence item in Nature ). Even if no reference limit exists, other journals impose a word limit that includes references, effectively also capping the amount of references. Coping with these limits sometimes requires difficult decisions to omit citations you may feel are legitimate or even necessary. In order to deal with this issue and avoid random removal of references, all desired citations require prioritisation. A few rules of thumb, shown in Box 1 , will help decisions on reference priority.

Box 1: Reference prioritisation

‘Ten simple sub-rules for prioritising references’ can help to facilitate prioritisation. In most cases, a subset of the 10 sub-rules will suffice. First, prioritise anew for each publication. Prioritisations cannot (easily) be copied from one study to another. Second, prioritise per section (e.g., introduction, methods, discussion), not across the entire paper. Different sections require different types of support. Third, for the introduction, prioritise reviews, allowing broad context for relevance and aim. Fourth, for the discussion, prioritise empirical papers, allowing detailed accounts of relative contribution. Fifth, prioritise reviewed over un- or prereviewed papers (e.g., editorials, preprints, etc.). Sixth, deprioritise self-citations. Seventh, limit the number of citations to support a specific claim, if necessary, to a single citation. Eighth, move methodological citations to supplementary (online) information. Ninth, in cases of equal relevance, prioritise citation of female first or last authors to help repair gender imbalances in science. Tenth, request the inclusion of additional references with the editors, arguing that you have used all of the previous nine sub-rules.

Rule 7: Evaluate citations as the choices that they are

Research publications are not mere vessels of data or findings. They convey a narrative explaining why questions are worth asking, what their answers may mean, how these answers were reached, why they are to be trusted, and more. They also have a purpose in the sense that they will act as support for other studies to come. Each of the elements of their story is supported by links to other studies, and each of those links is the result of an active choice by the author(s) in the context of the goal they wish to achieve by their inclusion.

At the other end of the narrative, readers assess and evaluate the story constantly, asking whether it could have been told differently. The realisation that narratives can be told differently, supported by other citations to other prior work, does not disqualify them. Both the story and the choice of citations are political choices meant to provide the argument with as much power, credibility, and legitimacy the author(s) can muster. They are tailored to the audience the authors seek to convince: their peers. The choice to include or exclude a reference can only be evaluated in the context of that narrative and the role they play in it. Peritz has provided a classification of citation roles to assist this evaluation [ 14 ].

Rule 8: Evaluate citations in their rhetorical context

Rhetorical strategies serve to convince and persuade. Narratives are but one of the tools that can be used to persuade audiences. Metaphors, numbers, and associations all feature in our research papers as tools to convince our readers. The genre of the scientific article has had centuries to evolve to incorporate many of them, with the goal of convincing readers that the author is right. Bazerman has literally written the book on this [ 15 ] and urges us to consider academic texts and their features as part of social and intellectual endeavours. Citations are a part of the social fabric of science in the sense that through citing specific sources, authors show their allegiance to schools of thought, communities, or, in the context of scientific controversies, which paradigm they consider themselves part of. Other rhetorical uses of citations include explicit citations to notable figures and their work, which can serve as appeals to authority, while long lists of citations can serve as proxies for well-studied subjects.

Consider the following: Authors can describe a field as well-studied and include three references—X, Y, and Z—as support for their claim. Alternatively, they can argue that a field is understudied but that three exceptions exist, i.e., X, Y, and Z. Understanding the value attributed to X, Y, and Z in that particular text requires assessment of the rhetorical strategies of the author(s).

Rule 9: Evaluate citations as framed communication

Authors use words to accomplish things and, in service of those goals, position their work and that of others. They frame prior work in a very specific way, supporting the arguments made. We all do. The positioning of X, Y, and Z either as the norm or as exceptions, as shown in Rule 8, is an example of framing. It is important to recognise such framing and that X, Y, and Z acquire meaning in the text as the result of the frame. There is no frameless communication, as Goffman [ 16 ] demonstrated. All messages and texts contain and require a frame—a structure of definitions and assumptions that help organise coherence, connections, and, ultimately, meaning—or in other words, a perspective on reality.

As a result, a citation is not a neutral line drawn between publications A and B. Rather, the representation of cited article A only acquires meaning in the context of citing in article B. Article A can be framed differently when cited in work B or C. It can be framed as innovative in B or dogmatic in C. Framing usually is not lying or deceiving; it is a normative positioning of evidence in context. Hence, a citation is a careful translation of a source’s relevant elements, which acquire meaning in that context only.

An important consequence of this is that merely counting citations of article A in the literature does not inform us of the value (or many types of value or lack thereof) of article A to the scientific community. This point also appears as the first principle in the Leiden Manifesto, which argues that quantitative metrics can only support qualitative metrics (i.e., reading with an attentive eye for politics, rhetoric, context, and frame—or as adhering to Rules 7–9). The Leiden Manifesto was published by bibliometricians and scholars of research evaluation following the 2014 conference on Science and Technology Indicators in Leiden, the Netherlands. It warns against the abuse of, among other things, citation-based research metrics [ 9 ].

Rule 10: Accept that citation cultures differ across boundaries

Despite critiques of the system, science is organised in such a way that citations continue to act as a currency that is represented as being universal [ 4 ]. However, citation practices are, for the most part, local practices, whether local to laboratories or department or local to disciplines. The average number of citations per paper differs between disciplines, and the way that citations are represented in the text and the value of being cited also differ radically [ 17 ]. What counts as proper citation practice in molecular biology—for instance, the inclusion of multiple references following a statement—is considered unacceptable in research ethics or science policy, in which single references require paragraphs of contextualisation and translation (see Rule 9 ). When reading a paper from an adjacent discipline, respect its different norms and conventions for responsible referencing and proper citation. If you are cited by a scientist from another discipline, assess that act as existing in a (however slightly) different citation culture.

Acknowledgments

I thank Maurice Zeegers and his team, who work on citation analyses, for stimulating me to think about the issue of citation more clearly, deeply, and critically, resulting in the considerations above. I also thank David Shaw for critical comments, moral support, and editorial assistance. As a closing note, as the human being that I am, I too have quite possibly referenced imperfectly in my previous work.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 3. Garfield E, Merton R. Citation indexing: Its theory and application in science, technology, and humanities: New York: Wiley; 1979.

- 4. Wouters P. The citation culture. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam; 1999.

- 5. Dahler-Larsen P. Constitutive effects of performance indicator systems. Dilemmas of engagement: Evaluation and the new public management. Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2007. p. 17–35.

- 15. Bazerman C. Shaping written knowledge: The genre and activity of the experimental article in science. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press; 1988.

- 16. Goffman E. Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience.Cambrdige, MA: Harvard University Press; 1974.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

MLA Works Cited Page: Basic Format

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

According to MLA style, you must have a Works Cited page at the end of your research paper. All entries in the Works Cited page must correspond to the works cited in your main text.

Basic rules

- Begin your Works Cited page on a separate page at the end of your research paper. It should have the same one-inch margins and last name, page number header as the rest of your paper.

- Only the title should be centered. The citation entries themselves should be aligned with the left margin.

- Double space all citations, but do not skip spaces between entries.

- Indent the second and subsequent lines of citations by 0.5 inches to create a hanging indent.

- List page numbers of sources efficiently, when needed. If you refer to a journal article that appeared on pages 225 through 250, list the page numbers on your Works Cited page as pp. 225-50 (Note: MLA style dictates that you should omit the first sets of repeated digits. In our example, the digit in the hundreds place is repeated between 2 25 and 2 50, so you omit the 2 from 250 in the citation: pp. 225-50). If the excerpt spans multiple pages, use “pp.” Note that MLA style uses a hyphen in a span of pages.

- If only one page of a print source is used, mark it with the abbreviation “p.” before the page number (e.g., p. 157). If a span of pages is used, mark it with the abbreviation “pp.” before the page number (e.g., pp. 157-68).

- If you're citing an article or a publication that was originally issued in print form but that you retrieved from an online database, you should type the online database name in italics. You do not need to provide subscription information in addition to the database name.

- For online sources, you should include a location to show readers where you found the source. Many scholarly databases use a DOI (digital object identifier). Use a DOI in your citation if you can; otherwise use a URL. Delete “http://” from URLs. The DOI or URL is usually the last element in a citation and should be followed by a period.

- All works cited entries end with a period.

Additional basic rules new to MLA 2021

New to MLA 2021:

- Apps and databases should be cited only when they are containers of the particular works you are citing, such as when they are the platforms of publication of the works in their entirety, and not an intermediary that redirects your access to a source published somewhere else, such as another platform. For example, the Philosophy Books app should be cited as a container when you use one of its many works, since the app contains them in their entirety. However, a PDF article saved to the Dropbox app is published somewhere else, and so the app should not be cited as a container.

- If it is important that your readers know an author’s/person’s pseudonym, stage-name, or various other names, then you should generally cite the better-known form of author’s/person’s name. For example, since the author of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland is better-known by his pseudonym, cite Lewis Carroll opposed to Charles Dodgson (real name).

- For annotated bibliographies , annotations should be appended at the end of a source/entry with one-inch indentations from where the entry begins. Annotations may be written as concise phrases or complete sentences, generally not exceeding one paragraph in length.

Capitalization and punctuation

- Capitalize each word in the titles of articles, books, etc, but do not capitalize articles (the, an), prepositions, or conjunctions unless one is the first word of the title or subtitle: Gone with the Wind, The Art of War, There Is Nothing Left to Lose .

- Use italics (instead of underlining) for titles of larger works (books, magazines) and quotation marks for titles of shorter works (poems, articles)

Listing author names

Entries are listed alphabetically by the author's last name (or, for entire edited collections, editor names). Author names are written with the last name first, then the first name, and then the middle name or middle initial when needed:

Do not list titles (Dr., Sir, Saint, etc.) or degrees (PhD, MA, DDS, etc.) with names. A book listing an author named "John Bigbrain, PhD" appears simply as "Bigbrain, John." Do, however, include suffixes like "Jr." or "II." Putting it all together, a work by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. would be cited as "King, Martin Luther, Jr." Here the suffix following the first or middle name and a comma.

More than one work by an author

If you have cited more than one work by a particular author, order the entries alphabetically by title, and use three hyphens in place of the author's name for every entry after the first:

Burke, Kenneth. A Grammar of Motives . [...]

---. A Rhetoric of Motives . [...]

When an author or collection editor appears both as the sole author of a text and as the first author of a group, list solo-author entries first:

Heller, Steven, ed. The Education of an E-Designer .

Heller, Steven, and Karen Pomeroy. Design Literacy: Understanding Graphic Design.

Work with no known author

Alphabetize works with no known author by their title; use a shortened version of the title in the parenthetical citations in your paper. In this case, Boring Postcards USA has no known author:

Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulations. [...]

Boring Postcards USA [...]

Burke, Kenneth. A Rhetoric of Motives . [...]

Work by an author using a pseudonym or stage-name

New to MLA 9th edition, there are now steps to take for citing works by an author or authors using a pseudonym, stage-name, or different name.

If the person you wish to cite is well-known, cite the better-known form of the name of the author. For example, since Lewis Carroll is not only a pseudonym of Charles Dodgson , but also the better-known form of the author’s name, cite the former name opposed to the latter.

If the real name of the author is less well-known than their pseudonym, cite the author’s pseudonym in square brackets following the citation of their real name: “Christie, Agatha [Mary Westmacott].”

Authors who published various works under many names may be cited under a single form of the author’s name. When the form of the name you wish to cite differs from that which appears on the author’s work, include the latter in square brackets following an italicized published as : “Irving, Washington [ published as Knickerbocker, Diedrich].”.

Another acceptable option, in cases where there are only two forms of the author’s name, is to cite both forms of the author’s names as separate entries along with cross-references in square brackets: “Eliot, George [ see also Evans, Mary Anne].”.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation is the main style guide for legal citations in the US. It's widely used in law, and also when legal materials need to be cited in other disciplines. Bluebook footnote citation. 1 David E. Pozen, Freedom of Information Beyond the Freedom of Information Act, 165, U. P🇦 . L.

Guidelines on writing an APA style paper In-Text Citations. Resources on using in-text citations in APA style. ... Basic guidelines for formatting the reference list at the end of a standard APA research paper ... Rules for handling works by a single author or multiple authors that apply to all APA-style references in your reference list ...

The following are guidelines to follow when writing in-text citations: Ensure that the spelling of author names and the publication dates in reference list entries match those in the corresponding in-text citations. Cite only works that you have read and ideas that you have incorporated into your writing. The works you cite may provide key ...

APA in-text citations The basics. In-text citations are brief references in the running text that direct readers to the reference entry at the end of the paper. You include them every time you quote or paraphrase someone else's ideas or words to avoid plagiarism.. An APA in-text citation consists of the author's last name and the year of publication (also known as the author-date system).

APA Citation Basics. When using APA format, follow the author-date method of in-text citation. This means that the author's last name and the year of publication for the source should appear in the text, like, for example, (Jones, 1998). One complete reference for each source should appear in the reference list at the end of the paper.

Reference List: Basic Rules. This resourse, revised according to the 7 th edition APA Publication Manual, offers basic guidelines for formatting the reference list at the end of a standard APA research paper. Most sources follow fairly straightforward rules. However, because sources obtained from academic journals carry special weight in research writing, these sources are subject to special ...

In-text citations are covered in the seventh edition APA Style manuals in the Publication Manual Chapter 8 and the Concise Guide Chapter 8. Date created: September 2019. APA Style provides guidelines to help writers determine the appropriate level of citation and how to avoid plagiarism and self-plagiarism. We also provide specific guidance for ...

6 Interesting Citation Facts. The world of citations may seem cut and dry, but there's more to them than just specific capitalization rules, MLA in-text citations, and other formatting specifications.Citations have been helping researches document their sources for hundreds of years, and are a great way to learn more about a particular subject area.

Scholarship is a conversation and scholars use citations not only to give credit to original creators and thinkers, but also to add strength and authority to their own work.By citing their sources, scholars are placing their work in a specific context to show where they "fit" within the larger conversation.Citations are also a great way to leave a trail intended to help others who may want ...

The second set of four rules refers to evaluating citations and the meaning they have or acquire once they have become part of a text. Rule 1: Include relevant citations All scholarly writing requires a demonstration of the relevance of the questions asked, a display of the methods used, a rationale for the use of materials, and a discussion of ...

There are two main kinds of titles. Firstly, titles can be the name of the standalone work like books and research papers. In this case, the title of the work should appear in the title element of the reference. Secondly, they can be a part of a bigger work, such as edited chapters, podcast episodes, and even songs.

Throughout your paper, you need to apply the following APA format guidelines: Set page margins to 1 inch on all sides. Double-space all text, including headings. Indent the first line of every paragraph 0.5 inches. Use an accessible font (e.g., Times New Roman 12pt., Arial 11pt., or Georgia 11pt.).

When quoting directly from a work, include the author, publication year, and page number of the reference (preceded by "p."). Method 1: Introduce the quotation with a signal phrase that includes the author's last name; the publication year will follow in parentheses. Include the page number in parentheses at the end of the quoted text.

Basic in-text citation rules. In MLA Style, referring to the works of others in your text is done using parenthetical citations. This method involves providing relevant source information in parentheses whenever a sentence uses a quotation or paraphrase. Usually, the simplest way to do this is to put all of the source information in parentheses ...

To format a paper in APA Style, writers can typically use the default settings and automatic formatting tools of their word-processing program or make only minor adjustments. The guidelines for paper format apply to both student assignments and manuscripts being submitted for publication to a journal. If you are using APA Style to create ...

When you cite a source with up to three authors, cite all authors' names. For four or more authors, list only the first name, followed by ' et al. ': Number of authors. In-text citation example. 1 author. (Davis, 2019) 2 authors. (Davis and Barrett, 2019) 3 authors.

Quotes should always be cited (and indicated with quotation marks), and you should include a page number indicating where in the source the quote can be found. Example: Quote with APA Style in-text citation. Evolution is a gradual process that "can act only by very short and slow steps" (Darwin, 1859, p. 510).

The second set of four rules refers to evaluating citations and the meaning they have or acquire once they have become part of a text. Rule 1: Include relevant citations All scholarly writing requires a demonstration of the relevance of the questions asked, a display of the methods used, a rationale for the use of materials, and a discussion of ...

Text Formatting. Heading and Title. Running Head with Page Numbers. Placement of the List of Works Cited. Tables and Illustrations. Paper and Printing. Corrections and Insertions on Printouts. Binding a Printed Paper. Electronic Submission.

We use cookies that are necessary to make our site work. We may also use additional cookies to analyze, improve, and personalize our content and your digital experience.

APA (American Psychological Association) style is most commonly used to cite sources within the social sciences. This resource, revised according to the 6th edition, second printing of the APA manual, offers examples for the general format of APA research papers, in-text citations, endnotes/footnotes, and the reference page. For more information, please consult the Publication Manual of the ...