- Utility Menu

Psychology Graduate Program

- Psychology Department

The Clinical Psychology Program adheres to a clinical science model of training, and is a member of the Academy of Psychological Clinical Science. We are committed to training clinical psychologists whose research advances scientific knowledge of psychopathology and its treatment, and who are capable of applying evidence-based methods of assessment and clinical intervention. The main emphasis of the program is research, especially on severe psychopathology. The program includes research, course work, and clinical practica, and usually takes five years to complete. Students typically complete assessment and treatment practica during their second and third years in the program, and they must fulfill all departmental requirements prior to beginning their one-year internship. The curriculum meets requirements for licensure in Massachusetts, and is accredited by the Psychological Clinical Science Accreditation System (PCSAS) and by the American Psychological Association (APA). PCSAS re-accredited the program on December 15, 2022 for a 10-year term. APA most recently accredited the program on April 28, 2015 for a seven-year term, which was extended due to COVID-related delays.

Requirements

Required courses and training experiences fulfill requirements for clinical psychology licensure in Massachusetts as well as meet APA criteria for the accreditation of clinical psychology programs. In addition to these courses, further training experiences are required in accordance with the American Psychological Association’s guidelines for the accreditation of clinical psychology programs (e.g., clinical practica [e.g., PSY 3050 Clinical Practicum, PSY 3080 Practicum in Neuropsychological Assessment]; clinical internship).

Students in the clinical psychology program are required to take the following courses:

- PSY 3900 Professional Ethics

- PSY 2445 Psychotherapy Research

- PSY 2070 Psychometric Theory and Method Using R

- PSY 2430 Cultural, Racial, and Ethnic Bases of Behavior

- PSY 3250 Psychological Testing

- PSY 2050 History of Psychology

- PSY 1951 Intermediate Quantitative Methods

- PSY 1952 Multivariate Analysis in Psychology

- PSY 2040 Contemporary Topics in Psychopathology

- PSY 2460 Diagnostic Interviewing

- PSY 2420 Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Psychological Disorders

Clinical students must also take one course in each of the following substantive areas: biological bases of behavior (e.g., PSY 1202 Modern Neuroanatomy; PSY 1325 The Emotional, Social Brain; PSY 1355 The Adolescent Brain; PSY 1702 The Emotional Mind); social bases of behavior (e.g., PSY 2500 Proseminar in Social Psychology); cognitive-affective bases of behavior (e.g., PSY 2400 Cognitive Psychology and Emotional Disorders); and individual differences (Required course PSY 2040 Contemporary Topics in Psychopathology fulfills the individual differences requirement for Massachusetts licensure). In accordance with American Psychological Association guidelines for the accreditation of clinical psychology programs, clinical students also receive consultation and supervision within the context of clinical practica in psychological assessment and treatment beginning in their second semester of their first year and running through their third year. They receive further exposure to additional topics (e.g., human development) in the Developmental Psychopathology seminar and in the twice-monthly clinical psychology “brown bag” speaker series. Finally, students complete a year-long clinical internship. Students are responsible for making sure that they take courses in all the relevant and required areas listed above. Students wishing to substitute one required course for another should seek advice from their advisor and from the director of clinical training prior to registering. During the first year, students are advised to get in as many requirements as possible. Many requirements can be completed before the deadlines stated below. First-year project: Under the guidance of a faculty member who serves as a mentor, students participate in a research project and write a formal report on their research progress. Due by May of first year. Second-year project: Original research project leading to a written report in the style of an APA journal article. A ten-minute oral presentation is also required. Due by May of second year. General exam: A six-hour exam covering the literature of the field. To be taken in September before the start of the third year. Thesis prospectus: A written description of the research proposed must be approved by a prospectus committee appointed by the CHD. Due at the beginning of the fourth year. Thesis and oral defense: Ordinarily this would be completed by the end of the fourth year. Clinical internship: Ordinarily this would occur in the fifth year. Students must have completed their thesis research prior to going on internship.

Credit for Prior Graduate Work

A PhD student who has completed at least one full term of satisfactory work in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences may file an application at the Registrar’s Office requesting that work done in a graduate program elsewhere be counted toward the academic residence requirement. Forms are available online .

No more than the equivalent of eight half-courses may be so counted for the PhD.

An application for academic credit for work done elsewhere must contain a list of the courses, with grades, for which the student is seeking credit, and must be approved by the student’s department. In order for credit to be granted, official transcripts showing the courses for which credit is sought must be submitted to the registrar, unless they are already on file with the Graduate School. No guarantee is given in advance that such an application will be granted.

Only courses taken in a Harvard AB-AM or AB-SM program, in Harvard Summer School, as a GSAS Special Student or FAS courses taken as an employee under the Tuition Assistance Program (TAP) may be counted toward the minimum academic residence requirements for a Master’s degree.

Academic and financial credit for courses taken as a GSAS Special Student or FAS courses taken as a Harvard employee prior to admission to a degree program may be granted for a maximum of four half-courses toward a one-year Master’s and eight half-courses toward a two-year Master’s or the PhD degree.

Applications for academic and financial credit must be approved by the student’s department and should then be submitted to the Registrar’s Office.

Student Admissions, Outcomes, and other data

1. Time to Completion

Students can petition the program faculty to receive credit for prior graduate coursework, but it does not markedly reduce their expected time to complete the program.

2. Program Costs

3. Internships

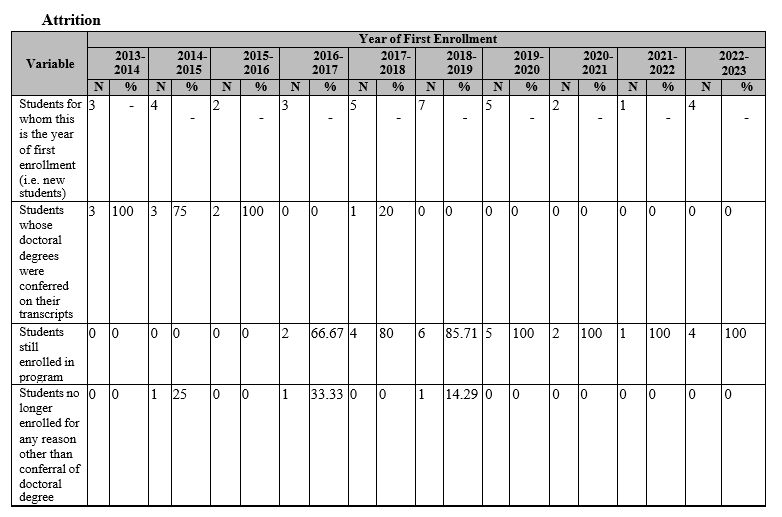

4. Attrition

5. Licensure

Standard Financial Aid Award, Students Entering 2023

The financial aid package for Ph.D. students entering in 2023 will include tuition and health fees support for years one through four, or five, if needed; stipend support in years one and two; a summer research grant equal to two months stipend at the end of years one through four; teaching fellowship support in years three and four guaranteed by the Psychology Department; and a dissertation completion grant consisting of tuition and stipend support in the appropriate year. Typically students will not be allowed to teach while receiving a stipend in years one and two or during the dissertation completion year.

Year 1 (2023-24) and Year 2 (2024- 25) Tuition & Health Fees: Paid in Full Academic Year Stipend: $35,700 (10 months) Summer Research Award: $7,140 (2 months)

Year 3 (2025-26) & Year 4 (2026- 27) Tuition & Health Fees: Paid in Full Living Expenses: $35,700 (Teaching Fellowship plus supplement, if eligible) Summer Research Award: $7,140 (2 months)

Year 5 (2027-28) - if needed; may not be taken after the Dissertation Completion year Tuition & Health Fees: Paid in Full

Dissertation Completion Year (normally year 5, occasionally year 6) Tuition & Health Fees: Paid in Full Stipend for Living Expenses: $35,700

The academic year stipend is for the ten-month period September through June. The first stipend payment will be made available at the start of the fall term with subsequent disbursements on the first of each month. The summer research award is intended for use in July and August following the first four academic years.

In the third and fourth years, the guaranteed income of $35,700 includes four sections of teaching and, if necessary, a small supplement from the Graduate School. Your teaching fellowship is guaranteed by the Department provided you have passed the General Examination or equivalent and met any other department criteria. Students are required to take a teacher training course in the first year of teaching.

The dissertation completion year fellowship will be available as soon as you are prepared to finish your dissertation, ordinarily in the fifth year. Applications for the completion fellowship must be submitted in February of the year prior to utilizing the award. Dissertation completion fellowships are not guaranteed after the seventh year. Please note that registration in the Graduate School is always subject to your maintaining satisfactory progress toward the degree.

GSAS students are strongly encouraged to apply for appropriate Harvard and outside fellowships throughout their enrollment. All students who receive funds from an outside source are expected to accept the award in place of the above Harvard award. In such cases, students may be eligible to receive a GSAS award of up to $4,000 for each academic year of external funding secured or defer up to one year of GSAS stipend support.

For additional information, please refer to the Financial Support section of the GSAS website ( gsas.harvard.edu/financial-support ).

Registration and Financial Aid in the Graduate School are always subject to maintaining satisfactory progress toward the degree.

Psychology students are eligible to apply for generous research and travel grants from the Department.

The figures quoted above are estimates provided by the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and are subject to change.

Office of Program Consultation and Accreditation American Psychological Association 750 First Street, NE Washington, DC 20002 Phone: (202) 336-5979 E-mail: [email protected] www.apa.org/ed/accreditation

The Director of Clinical Training is Prof. Richard J. McNally who can be reached by telephone at (617) 495-3853 or via e-mail at: [email protected] .

- Clinical Internship Allowance

Harvard Clinical Psychology Student Handbook

Department of Psychology

You are here, clinical psychology.

The Clinical Psychology area is dedicated to research and training in clinical science. The graduate program aspires to educate the next generation of leading academic and research psychologists and to create an environment for advancing research related to psychopathology and its treatment. While the program is decidedly research oriented, clinical training is viewed as essential to the development of outstanding clinical scientists and is designed to emphasize scientific principles that will enable students to investigate theoretically important and clinically relevant questions and to ensure competence in the provision of evidence-based assessment and intervention. Our students routinely secure placements at the most prestigious national internship sites, however the clinical program at Yale is not a match for students primarily interested in clinical practice. The program is well suited to students who desire to begin an independent, structured program of clinical science research and are likely to emerge as leaders in the study of psychopathology and its treatment. The values of the clinical program are reflected in current themes of our work, including 1) basic science research on psychopathology and its treatment; 2) integrative science involving methods and theories from related psychological disciplines; 3) evaluations of the psychological mechanisms, efficacy, effectiveness, and applications of psychosocial treatments; 4) applications of scientific inquiry to prevention and social policy.

Students admitted to the clinical area are expected to develop an independent line of research under the supervision of our primary faculty. Research training includes an emphasis on theory, methods, data analysis, grant writing, and manuscript preparation. Our students routinely publish in scholarly journals and disseminate their work at professional conferences during their graduate training, and many have successfully obtained external funding to support research projects.

Important additional information about the clinical program is contained in the document entitled “ Mission Statement, Program Structure and Requirements .” Please read that document carefully before applying to the clinical program. For information on practicum opportunities, click here , for information about the departmental clinic click here , and for information about eligibility of program graduates for professional licensure, click here . Details regarding professional activities post-graduation that are required for licensure are listed here , and a summary of the professional activities of program alumni at 2- and 5-years post-graduation are presented here .

The clinical program is strongly dedicated to promoting diversity and inclusion in our program and in students’ training . Students from underrepresented minority groups are especially encouraged to apply to our program.

General information about applying to clinical psychology programs and application tips can be found at:

http://clinicalpsychgradschool.org

The Clinical Psychology Doctoral Training Program is accredited by the Commission on Accreditation of the American Psychological Association and the Psychological Clinical Science Accreditation System (PCSAS), and is a member of The Academy of Psychological Clinical Science .

Questions related to the program’s accredited status should be directed to:

Office of Program Consultation and Accreditation American Psychological Association 750 1 st Street, NE, Washington, DC 20002 Phone: (202) 336-5979/E-mail: apaaccred@apa.org Web: www.apa.org/ed/accreditation

Psychological Clinical Science Accreditation System (PCSAS) 1800 Massachusetts Ave NW, Suite 402 Washington, DC 20036-1218 Phone: (301) 455-8046 /E-mail: akraut@pcsas.org Web: www.pcsas.org

As stated above, the Yale Clinical Psychology Doctoral Training Program is accredited by the American Psychological Association’s Commission on Accreditation (CoA) and the Psychological Clinical Science Accreditation System (PCSAS). Our clinical science training model and vision is most consistent with the standards of the PCSAS. Presently, PCSAS is working toward ensuring that: 1) graduates from its programs are fully license-eligible in the majority of states in which they may pursue professional practice; and 2) the American Board of Professional Psychology (ABPP) provides parity for and recognition of PCSAS within all of its regulatory standards. If and when these changes are realized, our program may consider remaining accredited solely by PCSAS. However, any such consideration would be based on clear evidence that our graduates can continue to obtain the sorts of successful career positions they have long enjoyed (e.g., as university professors, college teachers, public policy analysts, faculty in medical centers, research institutes and VA settings, licensed clinical psychologists, and administrators/directors of a variety of community agencies/organizations).

Questions related to the Yale Graduate Program in Clinical Psychology should be directed to the Director of Clinical Training, Mary O’Brien, Ph.D., or the primary faculty listed above.

*Students should apply to do graduate work only with primary faculty in the Psychology Department. Affiliated Faculty may serve as secondary mentors.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Clinical Psychology Research Topics

Stumped for ideas? Start here

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Emily is a board-certified science editor who has worked with top digital publishing brands like Voices for Biodiversity, Study.com, GoodTherapy, Vox, and Verywell.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Emily-Swaim-1000-0f3197de18f74329aeffb690a177160c.jpg)

Clinical psychology research is one of the most popular subfields in psychology. With such a wide range of topics to cover, figuring out clinical psychology research topics for papers, presentations, and experiments can be tricky.

Clinical Psychology Research Topic Ideas

Topic choices are only as limited as your imagination and assignment, so try narrowing the possibilities down from general questions to the specifics that apply to your area of specialization.

Here are just a few ideas to start the process:

- How does social media influence how people interact and behave?

- Compare and contrast two different types of therapy . When is each type best used? What disorders are best treated with these forms of therapy? What are the possible limitations of each type?

- Compare two psychological disorders . What are the signs and symptoms of each? How are they diagnosed and treated?

- How does "pro ana," "pro mia," " thinspo ," and similar content contribute to eating disorders? What can people do to overcome the influence of these sites?

- Explore how aging influences mental illness. What particular challenges elderly people diagnosed with mental illness face?

- Explore factors that influence adolescent mental health. Self-esteem and peer pressure are just a couple of the topics you might explore in greater depth.

- Explore the use and effectiveness of online therapy . What are some of its advantages and disadvantages ? How do those without technical literacy navigate it?

- Investigate current research on the impact of media violence on children's behavior.

- Explore anxiety disorders and their impact on daily functioning. What new therapies are available?

- What are the risk factors for depression ? Explore the potential risks as well as any preventative strategies that can be used.

- How do political and social climates affect mental health?

- What are the long-term effects of childhood trauma? Do children continue to experience the effects later in adulthood? What treatments are available for PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) in childhood ?

- What impact does substance use disorder have on the family? How can family members help with treatment?

- What types of therapy are most effective for childhood behavioral issues ?

Think of books you have read, research you have studied, and even experiences and interests from your own life. If you've ever wanted to dig further into something that interested you, this is a great opportunity. The more engaged you are with the topic, the more excited you will be to put the work in for a great research paper or presentation.

Consider Scope, Difficulty, and Suitability

Picking a good research topic is one of the most important steps of the research process. A too-general topic can feel overwhelming; likewise, one that's very specific might have limited supporting information. Spend time reading online or exploring your library to make sure that plenty of sources to support your paper, presentation, or experiment are available.

If you are doing an experiment , checking with your instructor is a must. In many cases, you might have to submit a proposal to your school's human subjects committee for approval. This committee will ensure that any potential research involving human subjects is done in a safe and ethical way.

Once you have chosen a topic that interests you, run the idea past your course instructor. (In some cases, this is required.) Even if you don't need permission from the instructor, getting feedback before you delve into the research process is helpful.

Your instructor can draw from a wealth of experience to offer good suggestions and ideas for your research, including the best available resources pertaining to the topic. Your school librarian may also be able to provide assistance regarding the resources available for use at the library, including online journal databases.

Kim WO. Institutional review board (IRB) and ethical issues in clinical research . Korean Journal of Anesthesiology . 2012;62(1):3-12. doi:10.4097/kjae.2012.62.1.3

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

What is a Clinical Research Psychologist

Clinical psychology research is a specialization within clinical research. It is the study of behavioral and mental health. In many ways, it is as important to the nation's health and well being as medical research.

In the same way that medical scientists work to understand the prevention, genesis, and spread of various diseases, clinical research psychologists conduct rigorous psychological research studies to understand, prevent, and treat the psychological conditions as it applies to individuals, couples, families, cultures, and diverse communities.

Empirical results gathered from psychological research studies guide practitioners in developing effective interventions and techniques that clinical psychologists employ - proven, reliable results that improve lives, mend troubled relationships, manage addictions, and help manage and treat a variety of other mental health issues. Clinical psychology integrates science with practice and produces a field that encourages a robust, ongoing process of scientific discovery and clinical application .

Clinical research psychologists integrate the science of psychology and the treatment of complex human problems with the intention of promoting change. The four main goals of psychology are to describe, explain, predict and control the behavior and mental processes of others. This approach allows clinical researchers to accomplish their goals for their psychological studies, which is to describe, explain, predict, and in some cases, influence processes or behaviors of the mind. The ultimate goal of scientific research in psychology is to illustrate behaviors and give details on why they take place.

Clinical psychologists work largely in health and social care settings including hospitals, health centers, community mental health teams, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) and social services. They often work as part of a team with other health professionals and practitioners.

Salary and Education

The mean annual salary of a clinical psychologist is about $69,000, however, those with doctoral degrees can earn salaries of $116,343 or more. This industry is highly stable and growing, as psychological research becomes more important to various other industries.

If you want to become a clinical research psychologist, you need a master’s or doctorate degree. In these graduate programs, you will be trained at how to navigate this large body of research. In addition, many clinical psychology students are able to make significant contributions to the field during their education by assisting in labs and learning valuable field knowledge.

Research in clinical psychology is vast, containing hundreds if not thousands of topics. By engaging in research, we are investigating new ways to understand the human mind, and developing solutions to enrich the lives of all others, many students create current and up-to-date with psychology research at universities and research labs across the world.

Take courses from CCRPS and learn more on how to become a clinical research professional.

Clinical Research Coordinator Training

Pharmacovigilance Certification

CRA Training

ICH-GCP Training

Clinical Trials Assistant Training

Advanced Clinical Research Project Manager Certification

Advanced Principal Investigator Physician Certification

Medical Monitor Certification

Discover more from Clinical Research Training | Certified Clinical Research Professionals Course

What to Know About Working at Eurofins Clinical Research Laboratories (CRL)

What is a clinical research director.

New Content From Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science

- Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science

- Cognitive Dissonance

- Meta-Analysis

- Methodology

- Preregistration

- Reproducibility

A Practical Guide to Conversation Research: How to Study What People Say to Each Other Michael Yeomans, F. Katelynn Boland, Hanne Collins, Nicole Abi-Esber, and Alison Wood Brooks

Conversation—a verbal interaction between two or more people—is a complex, pervasive, and consequential human behavior. Conversations have been studied across many academic disciplines. However, advances in recording and analysis techniques over the last decade have allowed researchers to more directly and precisely examine conversations in natural contexts and at a larger scale than ever before, and these advances open new paths to understand humanity and the social world. Existing reviews of text analysis and conversation research have focused on text generated by a single author (e.g., product reviews, news articles, and public speeches) and thus leave open questions about the unique challenges presented by interactive conversation data (i.e., dialogue). In this article, we suggest approaches to overcome common challenges in the workflow of conversation science, including recording and transcribing conversations, structuring data (to merge turn-level and speaker-level data sets), extracting and aggregating linguistic features, estimating effects, and sharing data. This practical guide is meant to shed light on current best practices and empower more researchers to study conversations more directly—to expand the community of conversation scholars and contribute to a greater cumulative scientific understanding of the social world.

Open-Science Guidance for Qualitative Research: An Empirically Validated Approach for De-Identifying Sensitive Narrative Data Rebecca Campbell, McKenzie Javorka, Jasmine Engleton, Kathryn Fishwick, Katie Gregory, and Rachael Goodman-Williams

The open-science movement seeks to make research more transparent and accessible. To that end, researchers are increasingly expected to share de-identified data with other scholars for review, reanalysis, and reuse. In psychology, open-science practices have been explored primarily within the context of quantitative data, but demands to share qualitative data are becoming more prevalent. Narrative data are far more challenging to de-identify fully, and because qualitative methods are often used in studies with marginalized, minoritized, and/or traumatized populations, data sharing may pose substantial risks for participants if their information can be later reidentified. To date, there has been little guidance in the literature on how to de-identify qualitative data. To address this gap, we developed a methodological framework for remediating sensitive narrative data. This multiphase process is modeled on common qualitative-coding strategies. The first phase includes consultations with diverse stakeholders and sources to understand reidentifiability risks and data-sharing concerns. The second phase outlines an iterative process for recognizing potentially identifiable information and constructing individualized remediation strategies through group review and consensus. The third phase includes multiple strategies for assessing the validity of the de-identification analyses (i.e., whether the remediated transcripts adequately protect participants’ privacy). We applied this framework to a set of 32 qualitative interviews with sexual-assault survivors. We provide case examples of how blurring and redaction techniques can be used to protect names, dates, locations, trauma histories, help-seeking experiences, and other information about dyadic interactions.

Impossible Hypotheses and Effect-Size Limits Wijnand van Tilburg and Lennert van Tilburg

Psychological science is moving toward further specification of effect sizes when formulating hypotheses, performing power analyses, and considering the relevance of findings. This development has sparked an appreciation for the wider context in which such effect sizes are found because the importance assigned to specific sizes may vary from situation to situation. We add to this development a crucial but in psychology hitherto underappreciated contingency: There are mathematical limits to the magnitudes that population effect sizes can take within the common multivariate context in which psychology is situated, and these limits can be far more restrictive than typically assumed. The implication is that some hypothesized or preregistered effect sizes may be impossible. At the same time, these restrictions offer a way of statistically triangulating the plausible range of unknown effect sizes. We explain the reason for the existence of these limits, illustrate how to identify them, and offer recommendations and tools for improving hypothesized effect sizes by exploiting the broader multivariate context in which they occur.

It’s All About Timing: Exploring Different Temporal Resolutions for Analyzing Digital-Phenotyping Data Anna Langener, Gert Stulp, Nicholas Jacobson, Andrea Costanzo, Raj Jagesar, Martien Kas, and Laura Bringmann

The use of smartphones and wearable sensors to passively collect data on behavior has great potential for better understanding psychological well-being and mental disorders with minimal burden. However, there are important methodological challenges that may hinder the widespread adoption of these passive measures. A crucial one is the issue of timescale: The chosen temporal resolution for summarizing and analyzing the data may affect how results are interpreted. Despite its importance, the choice of temporal resolution is rarely justified. In this study, we aim to improve current standards for analyzing digital-phenotyping data by addressing the time-related decisions faced by researchers. For illustrative purposes, we use data from 10 students whose behavior (e.g., GPS, app usage) was recorded for 28 days through the Behapp application on their mobile phones. In parallel, the participants actively answered questionnaires on their phones about their mood several times a day. We provide a walk-through on how to study different timescales by doing individualized correlation analyses and random-forest prediction models. By doing so, we demonstrate how choosing different resolutions can lead to different conclusions. Therefore, we propose conducting a multiverse analysis to investigate the consequences of choosing different temporal resolutions. This will improve current standards for analyzing digital-phenotyping data and may help combat the replications crisis caused in part by researchers making implicit decisions.

Calculating Repeated-Measures Meta-Analytic Effects for Continuous Outcomes: A Tutorial on Pretest–Posttest-Controlled Designs David R. Skvarc, Matthew Fuller-Tyszkiewicz

Meta-analysis is a statistical technique that combines the results of multiple studies to arrive at a more robust and reliable estimate of an overall effect or estimate of the true effect. Within the context of experimental study designs, standard meta-analyses generally use between-groups differences at a single time point. This approach fails to adequately account for preexisting differences that are likely to threaten causal inference. Meta-analyses that take into account the repeated-measures nature of these data are uncommon, and so this article serves as an instructive methodology for increasing the precision of meta-analyses by attempting to estimate the repeated-measures effect sizes, with particular focus on contexts with two time points and two groups (a between-groups pretest–posttest design)—a common scenario for clinical trials and experiments. In this article, we summarize the concept of a between-groups pretest–posttest meta-analysis and its applications. We then explain the basic steps involved in conducting this meta-analysis, including the extraction of data and several alternative approaches for the calculation of effect sizes. We also highlight the importance of considering the presence of within-subjects correlations when conducting this form of meta-analysis.

Reliability and Feasibility of Linear Mixed Models in Fully Crossed Experimental Designs Michele Scandola, Emmanuele Tidoni

The use of linear mixed models (LMMs) is increasing in psychology and neuroscience research In this article, we focus on the implementation of LMMs in fully crossed experimental designs. A key aspect of LMMs is choosing a random-effects structure according to the experimental needs. To date, opposite suggestions are present in the literature, spanning from keeping all random effects (maximal models), which produces several singularity and convergence issues, to removing random effects until the best fit is found, with the risk of inflating Type I error (reduced models). However, defining the random structure to fit a nonsingular and convergent model is not straightforward. Moreover, the lack of a standard approach may lead the researcher to make decisions that potentially inflate Type I errors. After reviewing LMMs, we introduce a step-by-step approach to avoid convergence and singularity issues and control for Type I error inflation during model reduction of fully crossed experimental designs. Specifically, we propose the use of complex random intercepts (CRIs) when maximal models are overparametrized. CRIs are multiple random intercepts that represent the residual variance of categorical fixed effects within a given grouping factor. We validated CRIs and the proposed procedure by extensive simulations and a real-case application. We demonstrate that CRIs can produce reliable results and require less computational resources. Moreover, we outline a few criteria and recommendations on how and when scholars should reduce overparametrized models. Overall, the proposed procedure provides clear solutions to avoid overinflated results using LMMs in psychology and neuroscience.

Understanding Meta-Analysis Through Data Simulation With Applications to Power Analysis Filippo Gambarota, Gianmarco Altoè

Meta-analysis is a powerful tool to combine evidence from existing literature. Despite several introductory and advanced materials about organizing, conducting, and reporting a meta-analysis, to our knowledge, there are no introductive materials about simulating the most common meta-analysis models. Data simulation is essential for developing and validating new statistical models and procedures. Furthermore, data simulation is a powerful educational tool for understanding a statistical method. In this tutorial, we show how to simulate equal-effects, random-effects, and metaregression models and illustrate how to estimate statistical power. Simulations for multilevel and multivariate models are available in the Supplemental Material available online. All materials associated with this article can be accessed on OSF ( https://osf.io/54djn/ ).

Feedback on this article? Email [email protected] or login to comment.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines .

Please login with your APS account to comment.

Privacy Overview

- Department of Psychology >

- Graduate >

- Graduate Admissions >

Clinical PhD Program

For information regarding the online application and admissions process, please visit the UB Graduate School.

- UB's General Admission Requirements

- Admissions FAQs

- Check Your Admissions Status

Follow us on Facebook and Twitter for weekly departmental updates.

Admission Requirements and Process

The Department of Psychology at the University at Buffalo uses a holistic admissions process in our consideration of applications. This means that we evaluate the entire application, rather than any single indicator or a few indicators. Thus, applicants are viewed as a whole person, the sum of their experiences, accomplishments, and aspirations. Consistent with this, we do not rely on or use “cut offs” for numerical indices of an academic record such as grade point average. A holistic approach also means that a candidate who may be less strong in some areas, can still have a highly competitive application by having greater strength in other areas. All elements of an application are taken into consideration, to maximize a good fit of the applicant with our training program and potential mentors, to reduce bias that can result from reliance on a limited number of components, and to reduce inequities in access to opportunities for graduate training.

Over the years, we have learned that a holistic admissions process helps us identify applicants who are likely to succeed in our graduate programs, brings a diversity of experience and ideas into our academic community, and supports a fair review of all applicants. Our goal is to recruit the next generation of academic psychologists who are passionate about making new discoveries and generating new knowledge in their chosen discipline. We expect students to bring hard work, professional ambition, resilience, grit, intellectual acumen, and enthusiasm to our graduate programs.

Although we value quantitative criteria like GPA, we take a broad view of academic excellence and recognize that indices of success in our graduate programs and professional achievement cannot be reduced to numbers alone. In short, we endeavor to balance quantitative and qualitative indices of success. Because we want to give students the greatest opportunity to thrive in our program, we place a strong emphasis on fit with our programs and potential faculty mentors. A highly qualified applicant may not be strongly considered if their interests and goals do not provide a good fit with the orientation of our training program or with faculty research interests. Accordingly, we consider the following components in our admissions decisions: personal statement, undergraduate transcript and GPA (and prior graduate record if applicable), letters of recommendation, and resume/research experience. Interviews are required for applicants to the Behavioral Neuroscience, Clinical, and Social-Personality doctoral programs, and our MA programs in General Psychology; interviews are not required for applicants to the Cognitive Psychology doctoral program. After initial review of applications, the selected applicants to programs requiring an interview will be contacted by prospective advisors to set up an interview time.

Schomburg statements are optional for applicants to our doctoral programs interested in being considered for a Schomburg Fellowship. These statements are not used for admissions decisions.

Clinical PhD Program:

Components of the application and how they are used, personal statement (required).

Helps contextualize the more quantitative and objective credentials of an applicant. The statement is used to evaluate the applicant’s goals and fit with the program and research interests of the faculty as well as how they would contribute to the diversity of thought and perspectives.

Prompt for Personal Statement (1000 words or less):

Describe the area of research you are interested in pursuing during your graduate studies and explain how our program would help you achieve your intellectual goals. The statement should include your academic background, intellectual interests and training or research experience that has prepared you for our program. The statement should also identify specific faculty members whose research interests align with your own interests.

Submitting Personal Statement:

Uploaded as part of the online application.

Transcript and GPA (required)

Provides evidence that the applicant is seeking challenging coursework, while excelling and showing academic growth. The University at Buffalo requires an undergraduate GPA of 3.0 or higher. However, applications with an undergraduate GPA below 3.0 can still be considered, particularly when other components of the application are strong (e.g., a high graduate GPA, etc.).

Submitting transcripts:

Upload scanned copies of all undergraduate and graduate transcripts as part of your online application. Include the English translation, if applicable.

Letters of recommendation (3 required):

Provides a third-party endorsement of the applicant’s attributes, ability to succeed in the graduate program, and potential to contribute to the field. The letter offers a perspective on the applicant’s prior achievements and potential to succeed, along with concrete examples of the subjective traits described in other elements of the application.

Submitting Letters:

Letters must be submitted electronically. Further instructions are included in the online application.

Resume and research experience (required):

Provides information on how the applicant has practically applied ideas and concepts learned in the classroom. It helps show that applicants possess the skills and dispositions needed to conduct extensive research and make substantive contributions to their chosen field.

Submitting resume

Interviews are a way for programs to get to know applicants as a person. They provide a qualitative means of: (a) contextualizing quantitative and objective credentials, and (b) evaluating how well an applicant’s goals and training needs fit with the program and potential mentors. In addition, the Clinical PhD program also uses the interview to evaluate suitability for clinical work.

Schomburg Statement (optional Applications to our doctoral program):

What is a schomburg fellowship.

A Schomburg Fellowship offers support for students in doctoral programs who can demonstrate that they would contribute to the diversity of the student body, especially those who can demonstrate that they have overcome a disadvantage or other impediment to success in higher education. In order to be eligible for the Schomburg Fellowship, you need to be either a U.S. Citizen or Permanent Resident and have a cumulative undergraduate GPA of 3.0 or above.

Here is a link to more information about Schomburg Fellowships.

https://arts-sciences.buffalo.edu/current-students/funding-your-degree/graduate-awards-fellowships/schomburg-fellowship.html

The Schomburg statement provides useful information in helping the faculty decide whether to nominate an applicant for the Schomburg Fellowship.

Schomburg Statement:

If you would like to be considered for a Schomburg Fellowship, please upload a written statement with your online application (maximum of 500 words) describing how you will contribute to the diversity of the student body in your graduate program, including by having overcome a disadvantage or other impediment to success in higher education. Please note that such categorical circumstances may include academic, vocational, social, physical or economic impediments or disadvantaged status you have been able to overcome, as evidenced by your performance as an undergraduate, or other characteristics that constitute categorical underrepresentation in your particular graduate program such as gender or racial/ethnic status.

Submitting a Schomburg statement:

This website requires JavaScript to run properly, but JavaScript is disabled. Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

- Learn Everywhere

- Undergraduate Programs

Professor Draheim’s New Research on AI in Clinical Psychology Education

Dr. Amanda Draheim, Assistant Professor of Psychology, is one of four Goucher College faculty members who will embark on a funded Year of Exploration.

Dr. Amanda Draheim, Assistant Professor of Psychology, is one of four Goucher College faculty members who will embark on a funded Year of Exploration as the 2024 recipients of the Myra Berman Kurtz Fund for Faculty Research and Exploration of the Sciences ( KRES Fund ). Dr. Draheim’s project, Use of Artificial Intelligence for Training Case Conceptualization and Treatment Planning in Psychotherapy, will explore how artificial intelligence may be applied to training case conceptualization skills among graduate trainees in clinical psychology. Case conceptualization involves using the client’s presenting concerns combined with psychological research to develop a rationale for a client’s distress and to inform treatment. Developing skill-in-case conceptualization is challenging but important, as it is considered a core competency for clinicians. Dr. Draheim hopes to explore risks and benefits of using artificial intelligence to train this skill and to develop and disseminate a ChatGPT script that will emphasize a strengths-based and culturally informed approach.

In addition, Dr. Draheim is presenting in the Incorporating Generative AI into Learning Experiences Virtual Showcase , hosted by the Center for Academic Innovation , on Friday April 26th. From the website: "The showcase will highlight how faculty, staff, and faculty/staff/student teams from across Maryland higher education have engaged in the use of Generative AI as part of assignments and learning activities." Dr. Draheim’s presentation, “How to Teach Students to Use Generative Artificial Intelligence Responsibly: Lessons from Clinical Psychology,” focuses on how principles from motivational interviewing can potentially inform how we encourage students to use generative artificial intelligence with integrity. This includes providing education about how to use ethical principles to inform decision-making, allowing students to explore their reasons for and against using generative artificial intelligence in unethical ways with empathy and nonjudgment, and promoting their sense of self-efficacy in using generative artificial intelligence ethically. Dr. Draheim will review some preliminary data from students in Psychological Distress and Disorder course supporting this approach.

- Visit Campus

- Request Info

- Give to Goucher

Psychological Factors Underlying Binge-Watching & Loneliness

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

Research has highlighted the potential negative consequences of binge-watching, which has become increasingly common due to the widespread availability of streaming platforms and digital technologies. Studies have linked binge-watching to various physical and mental health issues, such as reduced social interaction, poor sleep quality, increased sedentary lifestyle, and weight gain.

- Loneliness is associated with higher levels of problematic use of digital technologies, with escapism being a significant predictor of binge-watching tendencies through the mediating effect of identification with media characters.

- Binge-watching may be a coping strategy for lonely individuals to escape reality and connect with fictional characters.

- The research has limitations, such as its correlational design preventing causal conclusions.

- Understanding the psychological factors behind binge-watching is increasingly relevant as streaming services grow in popularity.

Previous research has established links between loneliness, problematic digital technology use, and unhealthy coping mechanisms (Tokunaga & Rains, 2010; Nowland et al., 2018; Moretta & Buodo, 2020).

The rise of streaming services has made binge-watching TV series increasingly common, raising concerns about its negative outcomes (De Feijter et al., 2016; Exelmans & Van den Bulck, 2017; Spruance et al., 2017). However, the specific psychological mechanisms driving binge-watching behavior remain underexplored.

Building on evidence that lonely individuals tend to identify more with media characters (Greenwood & Long, 2009) and that escapism motives predict problematic behaviors (Masur et al., 2014; Starosta & Izydorczyk, 2020), the present study examines how loneliness may lead to binge-watching through the desire to escape reality and identify with fictional characters.

Investigating these factors can provide insights into why people engage in maladaptive binge-watching and inform strategies to mitigate its negative effects as streaming continues to grow.

Cross-sectional online survey:

Procedure : Participants completed demographic questions, estimated typical media usage, and filled out scales assessing loneliness, problematic internet use, identification with TV characters, and binge-watching tendencies.

Sample : 196 TV series viewers (77 males, 119 females), mainly from the UK, aged 18-60 (M=33.76).

- UCLA Loneliness Scale (feelings of loneliness and social isolation)

- Internet Disorder Scale-15 (problematic internet use in 4 domains)

- Adapted Identification with Characters Scale (identification with TV characters)

- “Binge-Watching Engagement and Symptoms” subscale (binge-watching tendency)

Statistical measures : Correlations, multiple regression, mediation analysis using PROCESS macro.

The study’s findings support the hypothesis that escapism plays a crucial role in the relationship between loneliness and binge-watching.

The results indicate that lonely individuals tend to use binge-watching as a coping mechanism, as they seek to escape from their unpleasant feelings by immersing themselves in the lives of fictional characters.

Moreover, the study found that the more viewers identify with the characters in a TV series, the more likely they are to engage in binge-watching behavior. This suggests that the emotional connection and perceived similarity to the characters can fuel the desire to continue watching episode after episode.

Although the model explains a significant portion of the variance in binge-watching scores, it is important to note that other factors not examined in this study may also contribute to this behavior.

Further research is needed to explore additional psychological, social, and contextual variables that may influence binge-watching tendencies.

The findings suggest lonely individuals may binge-watch TV series as a way to escape unpleasant feelings and emotionally connect with on-screen characters.

This identification process, driven by the desire to escape reality, appears to promote binge-watching behavior.

The study extends prior work by directly testing psychological mechanisms underlying problematic binge-watching.

Future research could examine how individual differences (e.g., need for cognition/affect) moderate these relationships and track binge-watching patterns over time.

- Large sample size

- Well-validated measures

- Testing of rival mediators

Limitations

Cross-sectional design prevents causal conclusions

Sample mainly from the UK

Binge-watching is operationalized as a general tendency vs. discrete behavior

Clinical Implications

The results highlight psychological factors that may put lonely individuals at risk for maladaptive binge-watching as an unhealthy coping strategy.

Clinicians could assess these underlying vulnerabilities when clients present with excessive binge-watching. Streaming platforms might design content and features to facilitate healthier viewing patterns.

However, the generalizability of the findings to non-UK populations and the long-term impacts require further study.

Primary reference

Gabbiadini, A., Baldissarri, C., Valtorta, R. R., Durante, F., & Mari, S. (2021). Loneliness, escapism, and identification with media characters: An exploration of the psychological factors underlying binge-watching tendency. Frontiers in Psychology, 12 , 785970. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.785970

Other references

De Feijter, D., Khan, V. J., & van Gisbergen, M. (2016). Confessions of a ‘guilty’ couch potato: Understanding and using context to optimize binge-watching behavior. Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on Interactive Experiences for TV and Online Video , 59-67.

Exelmans, L., & Van den Bulck, J. (2017). Binge viewing, sleep, and the role of pre-sleep arousal. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 13 (8), 1001-1008.

Greenwood, D. N., & Long, C. R. (2009). Psychological predictors of media involvement: Solitude experiences and the need to belong. Communication Research, 36 (5), 637-654.

Masur, P. K., Reinecke, L., Ziegele, M., & Quiring, O. (2014). The interplay of intrinsic need satisfaction and Facebook specific motives in explaining addictive behavior on Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 39 , 376-386.

Moretta, T., & Buodo, G. (2020). Problematic internet use and loneliness: How complex is the relationship? A short literature review. Current Addiction Reports, 7, 125-136.

Nowland, R., Necka, E. A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2018). Loneliness and social internet use: Pathways to reconnection in a digital world? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13 (1), 70-87.

Spruance, L. A., Karmakar, M., Kruger, J. S., & Vaterlaus, J. M. (2017). “Are you still watching?”: Correlations between binge TV watching, diet and physical activity. Journal of Obesity & Weight Loss , 1–8

Starosta, J. A., & Izydorczyk, B. (2020). Understanding the phenomenon of binge-watching—A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17 (12), 4469.

Tokunaga, R. S., & Rains, S. A. (2010). An evaluation of two characterizations of the relationships between problematic internet use, time spent using the internet, and psychosocial problems. Human Communication Research, 36 (4), 512-545.

Keep Learning

- How might cultural factors influence the relationships between loneliness, escapism, and binge-watching?

- What are some healthier coping strategies lonely individuals could use instead of escapist binge-watching?

- Should streaming services take more responsibility in preventing problematic binge-watching? What steps could they take?

- How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected binge-watching behaviors and its psychological correlates?

COMMENTS

The Journal of Clinical Psychology is a clinical psychology and psychotherapy journal devoted to research, assessment, and practice in clinical psychological science. In addition to papers on psychopathology, psychodiagnostics, and the psychotherapeutic process, we welcome articles on psychotherapy effectiveness research, psychological assessment and treatment matching, clinical outcomes ...

Clinical psychologists aim to reduce distress and improve well-being for people across the lifespan with a range of psychosocial difficulties, by drawing on different assessment, formulation and intervention methods, as outlined by the British Psychological Society (BPS). 1 This may involve working directly, indirectly or through consultation, with individuals, families, groups or professionals.

Journal scope statement. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice ( CPSP) publishes cutting-edge reviews and developments in the science and practice of clinical psychology and related mental health fields. This is accomplished by publishing scholarly articles, primarily involving narrative and systematic reviews, as well as meta-analyses ...

The Clinical Psychology Program adheres to a clinical science model of training, and is a member of the Academy of Psychological Clinical Science. We are committed to training clinical psychologists whose research advances scientific knowledge of psychopathology and its treatment, and who are capable of applying evidence-based methods of ...

The Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology® (JCCP) publishes original contributions on the following topics: the development, validity, and use of techniques of diagnosis and treatment of disordered behavior. studies of a variety of populations that have clinical interest, including but not limited to medical patients, ethnic minorities ...

from Practice Innovations. August 3, 2023. It is time for a measurement-based care professional practice guideline in psychology. from Psychotherapy. July 31, 2023. Methodological and quantitative issues in the study of personality pathology. from Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. April 26, 2023.

About the journal. Clinical Psychology Review publishes substantive reviews of topics germane to clinical psychology. Papers cover diverse issues including: psychopathology, psychotherapy, behavior therapy, cognition and cognitive therapies, behavioral medicine, community mental health, assessment, and child …. View full aims & scope.

Clinical psychology—a field anchored on the deep integration of basic science and clinical practice—is uniquely positioned to serve as a transdisciplinary hub for this research (Baker et al 2008, McFall et al 2015). But rising to this challenge requires an honest reckoning with the strengths and weaknesses of current training practices.

In sum, clinical psychological science research must rise to the occasion and learn from this moment to increase the versatility of both its methods and conceptual perspectives. Concluding Comments Clinical psychological science is needed more than ever in response to both the acute and enduring psychological effects of COVID-19 ( Adhanom ...

Background. There is a growing body of evidence that conducting research in clinical practice not only improves the clinical performance of the service (Mckeon et al., 2013) but can also lead to improved physical health outcomes and survival rates (Nickerson et al., 2014; Ozdemir et al., 2015; Rochon, du Bois, & Lange, 2014).Clinical psychologists in the United Kingdom are predominantly ...

Clinical Psychological Science. Clinical Psychological Science provides metrics that help provide a view of the journal's performance. The Association for Psychological Science is a signatory of DORA, which recommends that journal-based metrics not be used to assess individual scientist contributions, including for hiring, promotion, or ...

1. Introduction. The standard narrative of current clinical psychology states that in order to develop innovative psychological interventions and/or further improve existing evidence-based treatments for mental disorders, it is necessary to conduct basic research investigating the processes underlying the development and maintenance of psychopathology (Clark & Fairburn, 1997; Davey, 2014 ...

The Clinical Psychology area is dedicated to research and training in clinical science. The graduate program aspires to educate the next generation of leading academic and research psychologists and to create an environment for advancing research related to psychopathology and its treatment.

Clinical Psychology Research Topic Ideas. Topic choices are only as limited as your imagination and assignment, so try narrowing the possibilities down from general questions to the specifics that apply to your area of specialization. Here are just a few ideas to start the process:

Clinical psychology research is as important to the nation's health and well being as medical research. In the same way that medical scientists work to understand the prevention, genesis, and spread of various genetic and infectious diseases, scientists conduct rigorous psychological research studies to understand, prevent, and treat the human condition as it applies psychologically to ...

The application of their research and the science behind their work make clinical psychologists invaluable in mental health and health care settings alike and in hospitals, schools, courts, the government, the military — almost anywhere you can imagine. 1 Compas, Bruce & Gotlib, Ian. (2002). Introduction to Clinical Psychology.

The outcomes achieved in rigorously controlled RCTs are usually diminished in clinical practice. This phenomenon, referred to as "voltage drop" or research-to-practice gap 6, is common across medicine, but has some unique considerations in psychological treatments. Many of the research procedures necessary to ensure internal validity reduce ...

Professors who are research psychologists may also provide opportunities for students to get involved with their projects. 3. Research manager. National average salary: $69,222 per year. Primary duties: Psychology research managers supervise teams of researchers to effectively perform and complete research projects.

Assistant Psychologist roles are often undertaken by ECRs and include some level of clinical contact with patients as well as a research component. The job plan and experiences of Assistant Psychologists can vary enormously, and are dependent on both service pressures and the managing Clinical Psychologist.

Clinical psychology research is a specialization within clinical research. It is the study of behavioral and mental health. In many ways, it is as important to the nation's health and well being as medical research. In the same way that medical scientists work to understand the prevention, genesis, and spread of various diseases, clinical ...

In fact, for much of its history, medicine resembled clinical psychology as it currently exists—that is, experiencing spirited debate about and resistance to the idea of accepting scientific research and theory as the preeminent arbiter of psychological practice (reflecting a schism dating back at least to the conflict between Empiricists and ...

We conducted a two-round modified Delphi to identify the research-methods skills that the UK psychology community deems essential for undergraduates to learn. Participants included 103 research-methods instructors, academics, students, and nonacademic psychologists. Of 78 items included in the consensus process, 34 reached consensus.

The Department of Psychology at the University at Buffalo uses a holistic admissions process in our consideration of applications. ... if their interests and goals do not provide a good fit with the orientation of our training program or with faculty research interests. ... Clinical, and Social-Personality doctoral programs, and our MA programs ...

Research roundup: Psychological interventions for individuals coping with a terminal illness. By Paragi Patel Date created: ... A randomized clinical trial was conducted in a California health system where 416 individuals with HF and depression were randomly assigned to receive either behavioral activation or an antidepressant medication (e.g ...

The 5-volume APA Handbook of Clinical Psychology reflects the state-of-the-art in clinical psychology — science, practice, research, and training.. The Handbook provides a comprehensive overview of: the history of clinical psychology, specialties and settings, theoretical and research approaches, assessment, treatment and prevention, psychological disorders, health and relational disorders ...

Dr. Draheim's project, Use of Artificial Intelligence for Training Case Conceptualization and Treatment Planning in Psychotherapy, will explore how artificial intelligence may be applied to training case conceptualization skills among graduate trainees in clinical psychology. Case conceptualization involves using the client's presenting ...

Abisha and Nihala Research Trends and Current Status of Clinical Psychology and Assessment 1. Integration of Science in Clinical Psychology: Current discussions highlight a pressing need for clinical psychology to embrace scientific principles, drawing parallels with historical shifts in medicine. The emphasis is on moving from an intuitive, experience-based approach to a more scientifically ...

Further research is needed to explore additional psychological, social, and contextual variables that may influence binge-watching tendencies. Insight The findings suggest lonely individuals may binge-watch TV series as a way to escape unpleasant feelings and emotionally connect with on-screen characters.

Clinical psychology is the psychological specialty that provides continuing and comprehensive mental and behavioral health care for individuals, couples, families, and groups; consultation to agencies and communities; training, education and supervision; and research-based practice. It is a specialty in breadth — one that addresses a wide ...